Abstract

Objective

To propose a common nomenclature to refer to individuals who fulfill the American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) during childhood or adolescence.

Methods

The medical literature was reviewed for studies conducted in the target population between 1960 and December of 2011 to obtain information about the terms used to refer to such children and adolescents. We reviewed the threshold ages used and disease features considered to discriminate these individuals from patients with onset of SLE during adulthood. Furthermore, the nomenclature used in other chronic diseases with onset during both childhood and adulthood was assessed.

Results

There was an astonishing variability in the age cut-offs used to define SLE-onset prior to adulthood, ranging from 14 to 21 years but most studies used 18 years of age. The principal synonyms in the medical literature were SLE without reference to the age at onset of disease, childhood-onset SLE, juvenile SLE, and pediatric (or paediatric) SLE.

Conclusions

Based on the definition of childhood, in analogy with other complex chronic disease commencing prior to adulthood, and given the current absence of definite genetic variations that discriminate adults from children, the term childhood-onset SLE is proposed when referring to individuals with onset of SLE prior to age 18 years.

INTRODUCTION

Various terms and definitions are used in the medical literature to refer to the subset of individuals that fulfill the American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) prior to adulthood (1). This results in several difficulties for healthcare providers, parents and families, researchers and government agencies because information and research data about patients with SLE onset prior to adulthood is often not directly comparable due to differences in age cut-offs chosen. Additionally, variation in the terminology can be confusing to patients and inhibits the review of the medical literature for information relevant to patients with SLE onset early in life.

The objective of this review was to appraise the medical literature in an attempt to propose a universally acceptable and sensible nomenclature to refer to individuals with SLE onset prior adulthood. Excluded was the group of children who are diagnosed with neonatal lupus, a disease primarily afflicting the offspring of women who test positive for antibodies to the nuclear antigens Ro/LA.

Is there a need for a different term to refer to SLE among children and adolescents?

There are no known unique physiological or genetic pathways that differentiate patients with SLE onset prior to adulthood from those with disease starting later on in life. This raises the question whether the 10–20% of patients with disease onset during childhood should be diagnosed with a different, albeit related disease, or simply be referred to as having SLE. Most medical reports aimed at distinguishing patients whose disease onset was before adulthood by authors who study patients with disease onset later in life. Examples include numerous reports from the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in a Multiethnic US (LUMINA) cohort, where only rare reports separate out those with disease onset early in life (2). An example clearly distinguishing the different age of onset groups are the reports of the Grupo Latino Americano de Estudio del Lupus Eritematoso (GLADEL) cohort (3–8).

Arguments in favor of a separate term when referring to adults versus children with SLE may be that some deficiencies of early components of the classical complement pathway predispose to SLE onset at an early stage in life. These deficiencies are uncommonly result in SLE signs and symptoms that commence during adulthood. Furthermore, the female to male ratio is at 4:3, much lower in populations in which disease that occurs in the first decade of life as compared to 9:1 in adult SLE (9–12). The above differences support the notion that there may be other, undiscovered inborn differences between adults and children with SLE. An additional argument in favor of introducing a separate term when referring to patients with SLE onset during childhood or adolescents may be the differences in patient phenotypes and the effectiveness and safety of pharmacologic interventions used for treatment. Children and adolescents often presents with more acute and severe SLE features than adults based on studies providing direct comparisons (2, 13, 14). Most published research suggests a higher rate of renal, neurological, and hematological involvement among children and adolescents as compared to adults at the time of SLE diagnosis (2, 14–18). Indeed, the average disease activity of children and adolescents with SLE is significantly higher than those with adult-onset SLE (19), with the most pronounced differences in renal and neurological organ systems. Besides significantly more active disease at the time of disease onset, there is also more active disease, damage, and mortality over time among children and adolescents compared to adults with SLE (2, 19). The above mentioned phenotypic differences often result in more intensive medical therapy, and especially the pediatric population requires multidisciplinary care, families’ education and the promotion of school performance. Taken together, there appear to be compelling arguments that make SLE with onset during childhood or adolescence deserving of a distinct designation.

When does adulthood start?

The most frequently used age at which adolescence ends is that proposed by the World Health Organization criteria at 19 years and 11 months (20). Conversely, the National Institutes of Health and the American Academy of Pediatrics suggest that the pediatric age ends with the 21st birthday (21). From a sociological point of view, the end of adolescence and the beginning of adulthood varies by geographical location, and even within a nation or culture different ages are taken into account at which an adolescent is considered to be chronologically and legally mature.

From a developmental point of view, adolescence is a period to consolidate identity, develop a positive body image, establishment of social relationships, achievement of independence, sexual identity, and to move from school to tertiary education or work. Childhood ends with the onset of adolescence which is associated with puberty and its dramatic alterations in hormone levels in both genders.

Eighteen years of age is the threshold age at diagnosis with SLE that is most frequently used to define SLE with onset during childhood or adolescence in population-based research around the world (2, 22–50). Nevertheless, age cut-offs used in studies of SLE range from 13 to 20 years (51–68). This is in line with some studies comparing pediatric versus adult populations with other chronic diseases, including asthma (69) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (70) which consider threshold ages of up to 20 years at diagnosis to define the pediatric subgroup. Conversely, a lower threshold for the age at diagnosis is used for some other chronic diseases. A prime example is juvenile idiopathic arthritis which, according to International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) classification, is defined as disease onset prior to the 16th birthday. This cut point is without strong genetic evidence that this is the most appropriate threshold age (71).

Similar to studies of pediatric lupus populations published to date, the age at diagnosis at 18 years is used to define patients with disease onset during childhood or adolescence with many other rheumatic diseases. Examples include studies of primary Sjogren’s syndrome (72), juvenile onset mixed connective tissue disease (73), and multinational studies of localized and systemic scleroderma (74, 75). Similarly, the classification criteria for primary childhood vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura, polyarteritis nodosa, granulomatosis and polyangiitis (Wegener’s), Takayasu arteritis) of the European League Against Rheumatism/Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation/Paediatric Rheumatology European Society use a maximum age at diagnosis of 18 years (76). Likewise, recent multicenter studies in juvenile dermatomyositis (77–79), population-based research in rheumatic fever (80, 81) and Lyme disease (82), inflammatory bowel disease (83, 84), pain amplification syndromes (including juvenile fibromyalgia) (85, 86), panniculitis in childhood and adolescence (87), and pediatric-onset relapsing polychondritis (88) all chose the age threshold of 18 years to define the pediatric population under consideration.

In line with many other pediatric rheumatic diseases, and as done for most studies reporting on patients with SLE commencing before or after puberty, we propose to use 18 years as the upper age at diagnosis. Although SLE with onset at 17-years of age is probably not different from disease beginning at 19 years-old. it is important to differentiate SLE in adolescents and adults.

A common definition of threshold age to define lupus with disease onset prior to adulthood is also important from a disease management point of view. The choice of 18 years appears sensible as it is often also used by adult rheumatology services (2, 27, 39, 43, 44, 49). Although quite arbitrary, one might expect that patients 18 years or older would more likely be treated by adult rheumatologists, and the transfer of medical care from pediatric to adult health care in the short term could be avoided, thus reducing the medical and psychosocial problems encountered during the transition process.

The current status of nomenclature used in the medical literature

When searching Pubmed (details of search terms are shown in Appendix 1) for the vocabulary used to refer to patients with SLE with disease onset during childhood or adolescents, four principal terms are recognized. They are ‘SLE’, juvenile SLE, pediatric (or paediatric) SLE (pSLE), and childhood-onset SLE (cSLE)

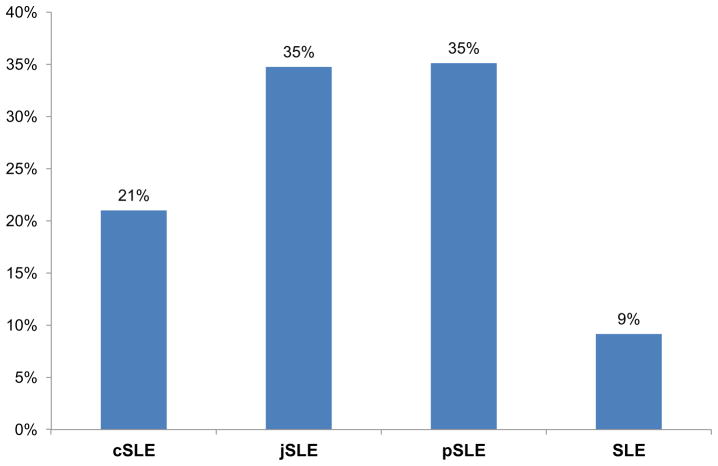

As shown in Figure 1, overall the most commonly used terms in the literature to date (in the order of frequency) are pSLE, SLE, jSLE and cSLE. Greater than 95% of articles about kidney involvement in children and adolescents use the term lupus nephritis (LN) without special emphasis on the young age of the study population (such as juvenile LN). A rationale for this might be that the renal histology is indistinguishable in those with early as compared to later onset of disease (89).

Figure 1.

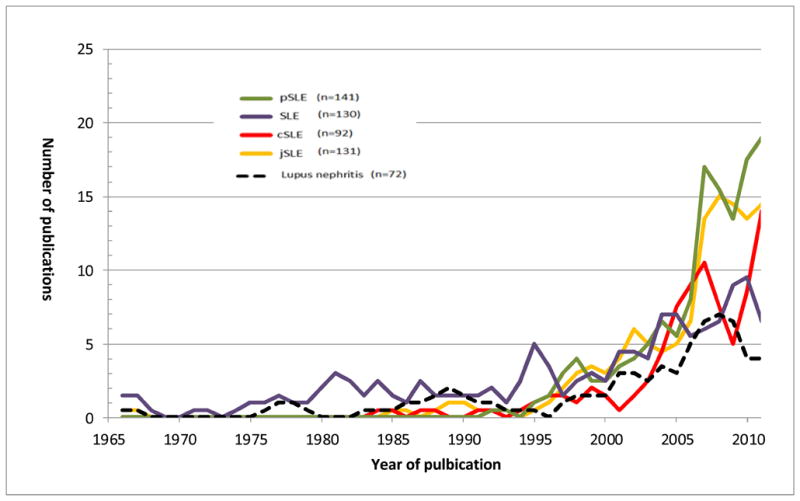

Use of the terms in the medical literature over time

SLE (or LN) without a clear distinction according to age at the time of disease onset is the term used to refer to children and adolescents in 43% of all case reports (with or without review of the medical literature rephrase this). In this setting, the term cSLE at less than 10% is the least commonly used.

Conversely, in rheumatology journals, the term SLE is the least frequently used term when reporting on children and adolescents diagnosed with the disease (Figure 2). The terms pSLE and jSLE are the most frequently used, with pSLE being used most frequently, particularly in recent years.

Figure 2.

Use of the terms in the rheumatology literature

Thus, if one agrees that children and adolescents fulfilling ACR SLE Classification criteria deserve a distinct designation, based on numbers alone and assuming that rheumatology journals being most precise in their reference of the population under investigation, pSLE might be the most appropriate term for use in manuscripts that report on individuals with disease onset of SLE during childhood.

However, to identify the most appropriate designation one could also use anetymologic approach. The Oxford pDictionary defines ‘juvenile’ as ‘not fully mature or immature or childish, while pediatric is defined as ‘relating to the medical care of children’ and childhood-onset as ‘onset during the time period of being a child’.

“Juvenile” may not be the most appropriate term, in spite of the frequent use in the pediatric rheumatology diseases, e.g. juvenile idiopathic arthritis (71), juvenile dermatomyositis (77–79), juvenile fibromyalgia) (85, 86). Although, “Pediatric” may be a more suitable term to define threshold at 18 years-old, this adjective is associated with children and may cause embarrassment among adults who had been diagnosed with SLE early in life. The term “childhood” includes prepubertal and postpubertal ages of children and adolescents. A caveat may be that this term is rarely used in specific cultures for those ages 15 years or older.

Nomenclature used in the medical literature for chronic diseases in childhood

Yet another approach to decide on a sensible common term when referring to individuals with onset of SLE prior to adulthood is to seek advice from other chronic pediatric diseases. It may be reassuring to some that rheumatology and lupus are not alone in their struggles to arrive at a standardized nomenclature for a chronic disease that can commence prior to adulthood.

In general, four distinct taxonomical categories of chronic diseases in childhood are acknowledged (Table 1). The first category represents well-characterized single diseases with onset in childhood. Each disease in this category has an established pathogenetic background and presents with distinctive clinical characteristics. These diseases are usually characterized by an adjective “juvenile”, displaying occurrence of the disease in a person that is not fully physically mature. Typical examples of this category are diseases such as juvenile myoclonic epilepsy and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.

Table 1.

Nomenclature of chronic diseases in childhood

| Single diseases with onset in childhood | Complex diseases with onset typically in childhood | Complex diseases with onset across different age groups | Single and complex childhood diseases with onset in adults |

|---|---|---|---|

| Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy | Pediatric/childhood asthma | Pediatric/childhood-onset epilepsy | Adult-onset Still’s disease |

| Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia | Pediatric/childhood leukemia | Childhood-onset schizophrenia | Adult-onset Henoch- Schönlein purpura |

| Juvenile polyposis syndrome | Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | Pediatric/childhood-onset depression | Adult Kawasaki disease |

| Juvenile xanthogranuloma | Juvenile dermatomyositis | Crohn’s disease (A1, A2, A3) | Adult-onset Alexander disease |

| Juvenile angiofibroma | Juvenile localized scleroderma | Pediatric/childhood-onset nephrotic syndrome | Adult-onset metachromatic leukodystrophy |

| Juvenile ossifying fibroma | Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (previously Juvenile diabetes) | Pediatric/childhood obesity | Adult congenital heart disease |

The second category represents complex chronic diseases with multifactorial pathogenesis and characteristic onset during childhood. Most of these diseases can be further sub-classified according to genetic background or similarities of the underlying immunopathogenic mechanisms. These diseases are devoid of a distinguishing nomenclature and, if they start early in life, are most commonly referred to as “pediatric”, “childhood”, or “juvenile” diseases. Pediatric (or childhood) asthma and juvenile idiopathic arthritis are among the most common chronic childhood diseases falling into this category. With advances in biochemistry, genetics and molecular biology, it is expected that the classification of these diseases will be reevaluated with the goal of achieving homogeneity within disease groups. An illustrative example is insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, which was previously referred to as juvenile diabetes. An interesting alternative in the taxonomy of complex chronic diseases is the Montreal classification of Crohn’s disease designating as “A1” category early onset disease before 16 years of age, whereas “A2” and “A3” categories account for age of diagnosis at 17–40 years and >40 years, respectively (90).

The third category represents diseases with typical onset in childhood which may occasionally develop also in adults. These diseases are generally characterized by an adjective “adult” or “adult-onset”. Typical examples of this category are diseases such as adult-onset Still’s diseases and adult Kawasaki disease.

The fourth category is represented by complex chronic diseases without a characteristic age of onset. These diseases are diagnosed in both pediatric and adult populations, and usually patients with disease onset in childhood continue to have disease manifestations in adulthood. Generally, the pathogenetic backgrounds of the childhood- and adult-onset disease are similar, albeit certain age-related factors may significantly change the clinical presentation in different age groups. There is no standardized nomenclature for these diseases, and a wide range of adjectives are used to characterize these diseases, including “pediatric” or “pediatric-onset” and “childhood” or “childhood-onset”. Typical examples of this category are pediatric or childhood-onset epilepsy and pediatric or childhood obesity. As per the current state of the medical knowledge, SLE also seems to belong to this category of diseases.

Summary

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is multifactorial complex autoimmune disease that is diagnosed in individuals of all ages. At present and in an effort to enhance the comparability of studies in this population, we propose the use of the term “childhood-onset SLE” to refer to individuals with onset of SLE after infancy but by the age of 18 years.

As is evidenced by the nomenclature used for juvenile idiopathic arthritis, nomenclature in medicine is dynamic and generally reflects the state of medical knowledge. Should future research yield data to support that the group of children and adolescents are genetically distinct from adults with SLE, then juvenile SLE would be the more appropriate term to use. Although some maturation processes, like those of the neurocognitive brain development, continue beyond the age of 18 year, most are completed by the age of 18 years, particularly growth and sexual development (91). Hence, we chose 18 years as the upper age of diagnosing cSLE. There are no data that would support that a higher or even a lower age cutoff would be more appropriate, e.g. that the disease course of adolescents with disease onset at age 15 or 17 years is more similar to that of adult-onset SLE than to that of patients with SLE onset during childhood. If future epidemiological research provides such evidence, then age threshold needs to be revisited.

It is hoped that this review will result in a more homogeneous approach to defining the group of individuals with SLE onset during childhood or adolescence and provide them with a common designation for the disease with which they are diagnosed.

Significance & Innovations.

International consensus on nomenclature to distinguish SLE patients with adult onset from SLE patients with earlier onset is absent.

For patients with onset of SLE from infancy to the age of 18 years-old, we recommend the use of the term “childhood-onset SLE”

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Edward Giannini for the review of the manuscript and suggestions to improve its quality.

Grant Support:

Dr. Brunner is supported by NIH grants 5U01-AR51868 and, P60-AR047884 and 2UL1RR026314. Dr Silva is supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo - FAPESP (grant 2011/12471-2), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPQ (472953/2008-7 and 302724/2011-7) and Federico Foundation. Dr. Avcin is supported by Slovenian Research Agency grants L3-4150 and P3-0343.

Appendix 1 - PubMed Search Strategy for SLE

MESH terms ‘lupus’, ‘SLE’ and ‘systemic lupus erythematosus’ were used. Limitations were the time between January 1960 and December 2011, and the terms ‘paediatric’, ‘pediatric’, juvenile, childhood, childhood-onset, children, adolescents. Furthermore, excluded were NLE, neonatal lupus, and ‘familial SLE’

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(9):1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tucker LB, Uribe AG, Fernandez M, Vila LM, McGwin G, Apte M, et al. Adolescent onset of lupus results in more aggressive disease and worse outcomes: results of a nested matched case-control study within LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA LVII) Lupus. 2008;17(4):314–322. doi: 10.1177/0961203307087875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shinjo SK, Bonfa E, Wojdyla D, Borba EF, Ramirez LA, Scherbarth HR, et al. Antimalarial treatment may have a time-dependent effect on lupus survival: data from a multinational Latin American inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(3):855–862. doi: 10.1002/art.27300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramirez Gomez LA, Uribe Uribe O, Osio Uribe O, Grisales Romero H, Cardiel MH, Wojdyla D, et al. Childhood systemic lupus erythematosus in Latin America. The GLADEL experience in 230 children. Lupus. 2008;17(6):596–604. doi: 10.1177/0961203307088006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia MA, Marcos JC, Marcos AI, Pons-Estel BA, Wojdyla D, Arturi A, et al. Male systemic lupus erythematosus in a Latin-American inception cohort of 1214 patients. Lupus. 2005;14(12):938–946. doi: 10.1191/0961203305lu2245oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alarcon-Segovia D, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Cardiel MH, Caeiro F, Massardo L, Villa AR, et al. Familial aggregation of systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and other autoimmune diseases in 1,177 lupus patients from the GLADEL cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(4):1138–1147. doi: 10.1002/art.20999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gamarra AI, Matteson EL, Rodriquez AI, Rodriguez MI, Restrepo Suarez JF. An historical review of systemic lupus erythematosus in Latin America. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10(7):RA171–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pons-Estel BA, Catoggio LJ, Cardiel MH, Soriano ER, Gentiletti S, Villa AR, et al. The GLADEL multinational Latin American prospective inception cohort of 1,214 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: ethnic and disease heterogeneity among “Hispanics”. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004;83(1):1–17. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000104742.42401.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danchenko N, Satia JA, Anthony MS. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of worldwide disease burden. Lupus. 2006;15(5):308–318. doi: 10.1191/0961203306lu2305xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malleson PN, Fung MY, Rosenberg AM. The incidence of pediatric rheumatic diseases: results from the Canadian Pediatric Rheumatology Association Disease Registry. J Rheumatol. 1996;23(11):1981–1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nossent HC. Systemic lupus erythematosus in the Arctic region of Norway. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(3):539–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA, Jr, Ramsey-Goldman R, LaPorte RE, Kwoh CK. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. Race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(9):1260–1270. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tucker LBUA, Fernandez M. Clinical differences between juvenile and adult onset patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from a multiethnic longitudinal cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(6):S162. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Font J, Cervera R, Espinosa G, Pallares L, Ramos-Casals M, Jimenez S, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in childhood: analysis of clinical and immunological findings in 34 patients and comparison with SLE characteristics in adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57(8):456–459. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.8.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tucker LB, Menon S, Schaller JG, Isenberg DA. Adult- and childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of onset, clinical features, serology, and outcome. British journal of rheumatology. 1995;34(9):866–872. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/34.9.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costallat LT, Coimbra AM. Systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical and laboratory aspects related to age at disease onset. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1994;12(6):603–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tucker LB. Making the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus in children and adolescents. Lupus. 2007;16(8):546–549. doi: 10.1177/0961203307078068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rood MJ, ten Cate R, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, den Ouden EJ, Ouwerkerk FE, Breedveld FC, et al. Childhood-onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: clinical presentation and prognosis in 31 patients. Scand J Rheumatol. 1999;28(4):222–226. doi: 10.1080/03009749950155580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brunner HI, Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Urowitz MD, Silverman ED. Difference in disease features between childhood-onset and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(2):556–562. doi: 10.1002/art.23204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McIntyre P WHO t. Adolescent Friendly Health Services — An Agenda for Chang. Geneva: Department of Child and Adolescent Health and Development; 2003. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2003/WHO_FCH_CAH_2002.2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brookman RR. The age of “adolescence”. The Journal of adolescent health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 1995;16(5):339–340. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(95)00071-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashkes PJ, Wright BM, Lauer MS, Worley SE, Tang AS, Roettcher PA, et al. Mortality outcomes in pediatric rheumatology in the US. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(2):599–608. doi: 10.1002/art.27218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avcin T, Cimaz R, Silverman ED, Cervera R, Gattorno M, Garay S, et al. Pediatric antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic features of 121 patients in an international registry. Pediatrics. 2008;122(5):e1100–1107. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutierrez-Suarez R, Ruperto N, Gastaldi R, Pistorio A, Felici E, Burgos-Vargas R, et al. A proposal for a pediatric version of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index based on the analysis of 1,015 patients with juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):2989–2996. doi: 10.1002/art.22048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiraki LT, Benseler SM, Tyrrell PN, Harvey E, Hebert D, Silverman ED. Ethnic differences in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(11):2539–2546. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parodi A, Davi S, Pringe AB, Pistorio A, Ruperto N, Magni-Manzoni S, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus: a multinational multicenter study of thirty-eight patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(11):3388–3399. doi: 10.1002/art.24883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramirez Gomez LA, Uribe Uribe O, Osio Uribe O, Grisales Romero H, Cardiel MH, Wojdyla D, et al. Childhood systemic lupus erythematosus in Latin America. The GLADEL experience in 230 children. Lupus. 2008;17(6):596–604. doi: 10.1177/0961203307088006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silva CA, Hilario MO, Febronio MV, Oliveira SK, Almeida RG, Fonseca AR, et al. Pregnancy outcome in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus: a Brazilian multicenter cohort study. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(7):1414–1418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva CA, Hilario MO, Febronio MV, Oliveira SK, Terreri MT, Sacchetti SB, et al. Risk factors for amenorrhea in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus (JSLE): a Brazilian multicentre cohort study. Lupus. 2007;16(7):531–536. doi: 10.1177/0961203307079300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avcin T, Benseler SM, Tyrrell PN, Cucnik S, Silverman ED. A followup study of antiphospholipid antibodies and associated neuropsychiatric manifestations in 137 children with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(2):206–213. doi: 10.1002/art.23334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campos LM, Omori CH, Lotito AP, Jesus AA, Porta G, Silva CA. Acute pancreatitis in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus: a manifestation of macrophage activation syndrome? Lupus. 2010;19(14):1654–1658. doi: 10.1177/0961203310378863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deen ME, Porta G, Fiorot FJ, Campos LM, Sallum AM, Silva CA. Autoimmune hepatitis and juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2009;18(8):747–751. doi: 10.1177/0961203308100559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faco MM, Leone C, Campos LM, Febronio MV, Marques HH, Silva CA. Risk factors associated with the death of patients hospitalized for juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research = Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologicas/Sociedade Brasileira de Biofisica [et al] 2007;40(7):993–1002. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2006005000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Febronio MV, Pereira RM, Bonfa E, Takiuti AD, Pereyra EA, Silva CA. Inflammatory cervicovaginal cytology is associated with disease activity in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2007;16(6):430–435. doi: 10.1177/0961203307079298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernandes EG, Savioli C, Siqueira JT, Silva CA. Oral health and the masticatory system in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2007;16(9):713–719. doi: 10.1177/0961203307081124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hari P, Bagga A, Mahajan P, Dinda A. Outcome of lupus nephritis in Indian children. Lupus. 2009;18(4):348–354. doi: 10.1177/0961203308097570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hersh AO, Trupin L, Yazdany J, Panopalis P, Julian L, Katz P, et al. Childhood-onset disease as a predictor of mortality in an adult cohort of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis care & research. 2010;62(8):1152–1159. doi: 10.1002/acr.20179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hiraki LT, Benseler SM, Tyrrell PN, Hebert D, Harvey E, Silverman ED. Clinical and laboratory characteristics and long-term outcome of pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus: a longitudinal study. The Journal of pediatrics. 2008;152(4):550–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffman IE, Lauwerys BR, De Keyser F, Huizinga TW, Isenberg D, Cebecauer L, et al. Juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: different clinical and serological pattern than adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(3):412–415. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.094813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jesus AA, Liphaus BL, Silva CA, Bando SY, Andrade LE, Coutinho A, et al. Complement and antibody primary immunodeficiency in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Lupus. 2011;20(12):1275–1284. doi: 10.1177/0961203311411598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jesus AA, Silva CA, Carneiro-Sampaio M, Sheinberg M, Mangueira CL, Marie SK, et al. Anti-C1q antibodies in juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1173:235–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jurencak R, Fritzler M, Tyrrell P, Hiraki L, Benseler S, Silverman E. Autoantibodies in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus: ethnic grouping, cluster analysis, and clinical correlations. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(2):416–421. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kisiel BM, Kosinska J, Wierzbowska M, Rutkowska-Sak L, Musiej-Nowakowska E, Wudarski M, et al. Differential association of juvenile and adult systemic lupus erythematosus with genetic variants of oestrogen receptors alpha and beta. Lupus. 2011;20(1):85–89. doi: 10.1177/0961203310381514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mok CC, Wong SN, Ma KM. Childhood-onset disease carries a higher risk of low bone mineral density in an adult population of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology. 2011 doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moorthy LN, Peterson MG, Hassett AL, Baratelli M, Chalom EC, Hashkes PJ, et al. Relationship between health-related quality of life and SLE activity and damage in children over time. Lupus. 2009;18(7):622–629. doi: 10.1177/0961203308101718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pereira T, Abitbol CL, Seeherunvong W, Katsoufis C, Chandar J, Freundlich M, et al. Three decades of progress in treating childhood-onset lupus nephritis. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2011;6(9):2192–2199. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00910111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rygg M, Pistorio A, Ravelli A, Maghnie M, Di Iorgi N, Bader-Meunier B, et al. A longitudinal PRINTO study on growth and puberty in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silva CA, Deen ME, Febronio MV, Oliveira SK, Terreri MT, Sacchetti SB, et al. Hormone profile in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus with previous or current amenorrhea. Rheumatology international. 2011;31(8):1037–1043. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1389-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang CH, Yao TC, Huang YL, Ou LS, Yeh KW, Huang JL. Acute pancreatitis in pediatric and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison and review of the literature. Lupus. 2011;20(5):443–452. doi: 10.1177/0961203310387179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spadoni M, Jacob C, Aikawa N, Jesus A, Fomin A, Silva C. Chronic autoimmune urticaria as the first manifestation of juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2011;20(7):763–766. doi: 10.1177/0961203310392428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brunner HI, Huggins J, Klein-Gitelman MS. Pediatric SLE--towards a comprehensive management plan. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2011;7(4):225–233. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mina R, Brunner HI. Pediatric lupus--are there differences in presentation, genetics, response to therapy, and damage accrual compared with adult lupus? Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America. 2010;36(1):53–80. vii–viii. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abdwani R, Hira M, Al-Nabhani D, Al-Zakwani I. Juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus in the Sultanate of Oman: clinical and immunological comparison between familial and non-familial cases. Lupus. 2011;20(3):315–319. doi: 10.1177/0961203310383299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ahmadzadeh A, Derakhshan A, Ahmadzadeh A. A clinicopathological study of lupus nephritis in children. Saudi journal of kidney diseases and transplantation: an official publication of the Saudi Center for Organ Transplantation, Saudi Arabia. 2008;19(5):756–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ali US, Dalvi RB, Merchant RH, Mehta KP, Chablani AT, Badakere SS, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in Indian children. Indian pediatrics. 1989;26(9):868–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ataei N, Haydarpour M, Madani A, Esfahani ST, Hajizadeh N, Moradinejad MH, et al. Outcome of lupus nephritis in Iranian children: prognostic significance of certain features. Pediatric nephrology. 2008;23(5):749–755. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0713-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aytac MB, Kasapcopur O, Aslan M, Erener-Ercan T, Cullu-Cokugras F, Arisoy N. Hepatitis B vaccination in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29(5):882–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bader-Meunier B, Armengaud JB, Haddad E, Salomon R, Deschenes G, Kone-Paut I, et al. Initial presentation of childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a French multicenter study. The Journal of pediatrics. 2005;146(5):648–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brunner HI, Feldman BM, Bombardier C, Silverman ED. Sensitivity of the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index, British Isles Lupus Assessment Group Index, and Systemic Lupus Activity Measure in the evaluation of clinical change in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(7):1354–1360. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199907)42:7<1354::AID-ANR8>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Campos LM, Kiss MH, D’Amico EA, Silva CA. Antiphospholipid antibodies and antiphospholipid syndrome in 57 children and adolescents with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2003;12(11):820–826. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu471oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Campos LM, Kiss MH, Scheinberg MA, Mangueira CL, Silva CA. Antinucleosome antibodies in patients with juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2006;15(8):496–500. doi: 10.1191/0961203306lu2317oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang JL, Yao TC, See LC. Prevalence of pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus and juvenile chronic arthritis in a Chinese population: a nation-wide prospective population-based study in Taiwan. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22(6):776–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang JL, Yeh KW, Yao TC, Huang YL, Chung HT, Ou LS, et al. Pediatric lupus in Asia. Lupus. 2010;19(12):1414–1418. doi: 10.1177/0961203310374339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klein A, Cimaz R, Quartier P, Decramer S, Niaudet P, Baudouin V, et al. Causes of death in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(3):538–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salah S, Lotfy HM, Mokbel AN, Kaddah AM, Fahmy N. Damage index in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in Egypt. Pediatric rheumatology online journal. 2011;9(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-9-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Salah S, Lotfy HM, Sabry SM, El Hamshary A, Taher H. Systemic lupus erythematosus in Egyptian children. Rheumatology international. 2009;29(12):1463–1468. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-0888-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Takei S, Maeno N, Shigemori M, Imanaka H, Mori H, Nerome Y, et al. Clinical features of Japanese children and adolescents with systemic lupus erythematosus: results of 1980–1994 survey. Acta paediatrica Japonica; Overseas edition. 1997;39(2):250–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1997.tb03594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsai YC, Yeh KW, Yao TC, Huang YL, Kuo ML, Huang JL. Mannose-binding lectin expression genotype in pediatric-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: associations with susceptibility to renal disease and protection against infections. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(7):1429–1435. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scott KM, Von Korff M, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Benjet C, Bruffaerts R, et al. Childhood adversity, early-onset depressive/anxiety disorders, and adult-onset asthma. Psychosomatic medicine. 2008;70(9):1035–1043. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318187a2fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schober E, Rami B, Grabert M, Thon A, Kapellen T, Reinehr T, et al. Phenotypical aspects of maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY diabetes) in comparison with Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in children and adolescents: experience from a large multicentre database. Diabetic medicine: a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2009;26(5):466–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, Goldenberg J, et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):390–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cimaz R, Casadei A, Rose C, Bartunkova J, Sediva A, Falcini F, et al. Primary Sjogren syndrome in the paediatric age: a multicentre survey. European journal of pediatrics. 2003;162(10):661–665. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kotajima L, Aotsuka S, Sumiya M, Yokohari R, Tojo T, Kasukawa R. Clinical features of patients with juvenile onset mixed connective tissue disease: analysis of data collected in a nationwide collaborative study in Japan. JRheumatol. 1996;23(6):1088–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, Nelson AM, Feitosa de Oliveira SK, Punaro MG, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. An international study Rheumatology. 2006;45(5):614–620. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martini G, Foeldvari I, Russo R, Cuttica R, Eberhard A, Ravelli A, et al. Systemic sclerosis in childhood: clinical and immunologic features of 153 patients in an international database. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(12):3971–3978. doi: 10.1002/art.22207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ozen S, Pistorio A, Iusan SM, Bakkaloglu A, Herlin T, Brik R, et al. EULAR/PRINTO/PRES criteria for Henoch-Schonlein purpura, childhood polyarteritis nodosa, childhood Wegener granulomatosis and childhood Takayasu arteritis: Ankara 2008. Part II: Final classification criteria. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(5):798–806. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.116657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guseinova D, Consolaro A, Trail L, Ferrari C, Pistorio A, Ruperto N, et al. Comparison of clinical features and drug therapies among European and Latin American patients with juvenile dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29(1):117–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ravelli A, Trail L, Ferrari C, Ruperto N, Pistorio A, Pilkington C, et al. Long-term outcome and prognostic factors of juvenile dermatomyositis: a multinational, multicenter study of 490 patients. Arthritis care & research. 2010;62(1):63–72. doi: 10.1002/acr.20015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sato JO, Sallum AM, Ferriani VP, Marini R, Sacchetti SB, Okuda EM, et al. A Brazilian registry of juvenile dermatomyositis: onset features and classification of 189 cases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(6):1031–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.da Silva CH. Rheumatic fever: a multicenter study in the state of Sao Paulo. Pediatric Committee--Sao Paulo Pediatric Rheumatology Society. Revista do Hospital das Clinicas. 1999;54(3):85–90. doi: 10.1590/s0041-87811999000300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moraes AJ, Soares PM, Leal MM, Sallum AM, Lotito AP, Silva CA. Aspects of the pregnancy and post delivery of adolescents with rheumatic fever. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira. 2004;50(3):293–296. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302004000300037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Al-Sharif B, Hall MC. Lyme disease testing in children in an endemic area. WMJ: official publication of the State Medical Society of Wisconsin. 2011;110(5):228–233. quiz 247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Long MD, Crandall WV, Leibowitz IH, Duffy L, del Rosario F, Kim SC, et al. Prevalence and epidemiology of overweight and obesity in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011;17(10):2162–2168. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Radzikowski A, Banaszkiewicz A, Lazowska-Przeorek I, Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk U, Wos H, Pytrus T, et al. Immunogenecity of hepatitis A vaccine in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011;17(5):1117–1124. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kashikar-Zuck S, Ting TV, Arnold LM, Bean J, Powers SW, Graham TB, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of juvenile fibromyalgia: A multisite, single-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(1):297–305. doi: 10.1002/art.30644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zapata AL, Moraes AJ, Leone C, Doria-Filho U, Silva CA. Pain and musculoskeletal pain syndromes related to computer and video game use in adolescents. European journal of pediatrics. 2006;165(6):408–414. doi: 10.1007/s00431-005-0018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moraes AJ, Soares PM, Zapata AL, Lotito AP, Sallum AM, Silva CA. Panniculitis in childhood and adolescence. Pediatrics international: official journal of the Japan Pediatric Society. 2006;48(1):48–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2006.02169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Belot A, Duquesne A, Job-Deslandre C, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Boudjemaa S, Wechsler B, et al. Pediatric-onset relapsing polychondritis: case series and systematic review. The Journal of pediatrics. 2010;156(3):484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rush PJ, Baumal R, Shore A, Balfe JW, Schreiber M. Correlation of renal histology with outcome in children with lupus nephritis. Kidney Int. 1986;29(5):1066–1071. doi: 10.1038/ki.1986.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55(6):749–753. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Uddin LQ, Supekar KS, Ryali S, Menon V. Dynamic reconfiguration of structural and functional connectivity across core neurocognitive brain networks with development. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31(50):18578–18589. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4465-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]