Abstract

Purpose

In this study, we assessed the specific role of BRAF(V600E) signaling in modulating the expression of immune regulatory genes in melanoma, in addition to analyzing downstream induction of immune suppression by primary human melanoma tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAFs).

Experimental Design

Primary human melanocytes and melanoma cell lines were transduced to express WT or V600E forms of BRAF, followed by gene expression analysis. The BRAF(V600E) inhibitor vemurafenib was used to confirm targets in BRAF(V600E)-positive melanoma cell lines and in tumors from melanoma patients undergoing inhibitor treatment. TAF lines generated from melanoma patient biopsies were tested for their ability to inhibit the function of tumor antigen-specific T-cells, prior to and following treatment with BRAF(V600E)-upregulated immune modulators. Transcriptional analysis of treated TAFs was conducted to identify potential mediators of T-cell suppression.

Results

Expression of BRAF(V600E) induced transcription of IL-1α and IL-1β in melanocytes and melanoma cell lines. Furthermore, vemurafenib reduced the expression of IL-1 protein in melanoma cell lines and most notably in human tumor biopsies from 11 of 12 melanoma patients undergoing inhibitor treatment. Treatment of melanoma-patient-derived TAFs with IL-1α/β significantly enhanced their ability to suppress the proliferation and function of melanoma-specific cytotoxic T cells, and this inhibition was partially attributable to upregulation by IL-1 of COX-2 and the PD-1 ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 in TAFs.

Conclusions

This study reveals a novel mechanism of immune suppression sensitive to BRAF(V600E) inhibition, and suggests that clinical blockade of IL-1 may benefit patients with BRAF wild-type tumors and potentially synergize with immunotherapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Melanoma, BRAF(V600E), interleukin-1, tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAFs), cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL)

INTRODUCTION

Several human and animal studies have provided evidence that a major barrier to the success of immunotherapies are multiple mechanisms of pre-existing, localized, tumor-induced immune suppression (1, 2). Many of these mechanisms cause downregulation or inhibition of T-cell function and are common to multiple cancers, with their presence frequently associated with poor patient prognosis (3). T-cell suppression can be caused by tumor cells directly through the secretion of inhibitory cytokines such as IL-10, TGF-β, or VEGF, or through membrane expression of co-inhibitory molecules such as the PD-1 ligands PD-L1 or PD-L2 (4). Alternatively, tumors can secrete factors that serve to recruit and activate inhibitory immune cells such as regulatory T cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, or tumor-associated macrophages, which can in turn inhibit the function of tumor-infiltrating T cells (TIL) (5). A number of recent studies have implicated stromal fibroblasts within tumors as additional cell types capable of mediating immune suppression (6–8). The tumor stroma is composed largely of cells derived from the mesenchymal lineage, broadly described as tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAF) (9, 10). These cells infiltrate and encapsulate the tumor parenchyma, are in proximity to infiltrating immune cells, and respond to molecular cues from tumors cells, thus influencing metastatic potential and drug resistance (10–13). Research into the functional consequences of these interactions has demonstrated that tumor and fibroblast-derived cytokines such as IL-1α or IL-1β are important in tumor progression as well as responses to therapy (11, 14–16). Furthermore, several studies have implicated IL-1α and β as being enforcers of sterile inflammation in melanoma tumors, and as major mediators of myeloid cell chemotaxis; however, the ultimate effect of IL-1 signaling on adaptive immune responses in the tumor microenvironment remains unclear (17–21).

Although several mechanisms of immune suppression in cancer have now been identified, the means by which these mechanisms are initiated in tumors is still not well understood. One emerging hypothesis is that constitutive MAPK pathway activation in tumor cells leads to the downstream production of immunomodulatory factors. Supporting this idea, oncogenic RAS can upregulate IL-6 secretion, leading to the promotion of tumor growth (22, 23). Furthermore, melanoma cell lines engineered to knock down BRAF(V600E) expression demonstrated reduced production of IL-6, IL-10 and VEGF, cytokines that inhibit the T-cell stimulatory function of dendritic cells (24). In the present study, we analyzed how BRAF(V600E) signaling influences the expression of immunomodulatory genes within the melanoma tumor microenvironment. Our results reveal that mutated BRAF stimulates the production of IL-1α and β in tumor cells, which in turn can promote functional T-cell suppression through inducing the expression of PD-1 ligands and COX-2 by melanoma TAFs. Importantly, pharmacologic inhibition of BRAF(V600E) relieved this mode of immune suppression, suggesting that patients may benefit from therapeutic approaches that combine the use of BRAF(V600E) inhibitors with T-cell based immunotherapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Transduction

WM793p2, A375, and T2 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO Grand Island, NY) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO), 10 IU/mL penicillin (Cellgrow Manassas, VA), 10 µg/mL streptomycin (Cellgrow) and maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. The EB16-MEL and KUL84-MEL cell lines which were kindly provided by Etienne De Plaen (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Brussels), were cultured in IMDM medium (GIBCO) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO), 10 IU/mL penicillin (Cellgrow), 10 µg/mL streptomycin (Cellgrow). Dermal Cell preparations were obtained from Sciencell (Carlsbad, CA) and cultured in the provided Melanocyte Medium (Sciencell). Primary neonatal epidermal melanocytes were obtained from Sciencecell and cultured in Melanocyte Medium with MS growth supplement (Sciencell). Patient biopsy derived TIL and TAFs were available with institutional IRB approval and patient informed consent. TIL or tumor digests were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (GIBCO) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO), 10 IU/mL penicillin (Cellgrow Manassas, VA), 10ug/mL streptomycin (Cellgrow) and supplemented with 200 IU/mL of IL-2 (Prometheus) unless otherwise indicated (48). TAFs were isolated from mixed tumor cell cultures based on CD90 positivity and MCSP negativity by cell sorting. TAFs were isolated from melanoma biopsies from lymph nodes, soft tissue, lung, brain, and chest wall.

B-RAF V600E and WT mutant plasmids were obtained from R. Marais (49). Genes were cloned into pDonor 222 (Invitrogen) by standard methodologies. These constructs were then sequenced and cloned into a self-inactivating bicistronic lentivirus expression vector (PLV401) containing the CMV promoter via LR reactions (Invitrogen), (Fig S1). Lentivirus was generated by Lipofectamine 2000 transfection of the packaging cell line, 293T-METR, with packaging plasmids containing p∆R8.91, CMV-pVSVG, and the indicated expression vectors. Viral supernatants were collected at 48hr and concentrated by ultracentrifugation. Dermal cell preparations and melanocytes were transduced at MOI of ~10, or by viral titration followed by selection of equivalently transduced lines based on GFP expression. Experiments using melanocytes transduced with BRAF V600E and control expression vectors were carried out between 2 and 10 days after transduction.

Patient samples

Patients with metastatic melanoma possessing BRAF V600E mutations were enrolled on a clinical trial for treatment with a BRAF inhibitor (vemurafenib, RO5185426) and were consented for tissue acquisition per IRB-approved protocol. Tumor biopsies were performed pre-treatment (day 0), at 10–14 days on treatment.

Melanoma Xenograft

NOD/SCID mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory. Mice were maintained in accordance with the institutional guidelines of MD Anderson Cancer center. Melanoma tumors were generated by subcutaneous injection of 10 million A375 cells on Day 0. Tumors were treated with PLX4720 (100 mg/kg body weight) on Day 7, administered by gavage on a daily basis for 3 days. Vehicle solution contained 3% DMSO and 1% methylcellulose. Harvested tumors were divided in half for histology and transcriptional analysis. Experiments used 3 mice per group.

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cultured melanoma cell lines and A375 xenografts using the RNAqueous NA isolation kit from Ambion. One step RT-PCR was conducted using iScript (Bio-RAD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer sequences used are as followed IL1aF: 5’TGGCCCACTCCATGAAGGCTGC IL1aR: 5’GTCATTGGCGATGGCGATGGCCTCCAGG IL1bF: 5’GCTTATGTGCACGATGCACCTG IL1bR: 5’TCCTGTCCCTGGAGGTGGAGAG GAPDHF: AGAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTTG GAPDHR: AGGGGCCATCCACAGTCTTC CNXF: GCGTTGTGGGGCAGATGAT CNXR CCGGTTGAGGTGCATCAGT. Exclusively for analysis of human transcripts from A375 xenografts, the primer sequences used are as follows: IL1aF: 5’GAGGCCATCGCCAATGACTCAGAG IL1aR: 5’CAGCCGTGAGGTACTGATCATTGG IL1bF: 5’GGACCTGGACCTCTGCCCTCTGGATGGCG IL1bR: 5’GTACAGGTGCATCGTGCACATAAGCC CXCL8F: 5’CTGCAGCTCTGTGTGAAGGTGCAG CXCL8R: 5’GGTCCAGACAGAGCTCTCTTCCATC CXCL1F: 5’CGCGCTGCTCTCTCCGCCGCC CXCL1R: 5’GTCCGGGGGACTTCACGTTCACAC PDL1F: 5’CCACCACCACCAATTCCAAGAG PDL1R: 5’CGGAAGATGAATGTCAGTGCTACACC PDL2F: 5’GGACCCATCCAACTTGGCTG PDL2R: 5’CACTTCCCTCTTTGTTGTGGTGACAG BACTINF: 5’CGAGGCCCAGAGCAAGAGAG BACTINR: 5’CGGTTGGCCTTAGGGTTCAG. Reactions were analyzed using a BIO-RAD CFX96 thermocycler and Ct values normalized to untreated samples relative to GAPDH or B-actin expression using the ΔΔCt method.

Microarray analysis and statistical methods

Transduced dermal cell preparations were sorted based on GFP expression as indicated by the gates in Figure 1A. TAFs were cultured with 2 ng/mL IL-1α (PeproTech Inc. Rocky Hill, NJ) or in regular media for 24 hours, detached from culture plates and stored at −80 as cell pellets until total RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy RNA extraction kit (Qiagen) and tested for quality by RIN analysis after product separation using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyser (Santa Clara, CA). RNA was prepared and hybridized on Affymetrix Human Genome U133A 2.0 Array (Santa Clara, CA) by Expression Analyses (Durham, NC). Expression data were normalized based on Bland-Altman (M-versus-A) pairwise plots, density plots, and boxplots

Figure 1. Ectopic expression of BRAF(V600E) upregulates IL-1α/β expression in melanocytes and melanoma cells.

(A and B) Flow cytometric analysis of green fluorescent protein (GFP) and BRAF expression in dermal melanocytes following transduction with lentiviral expression vectors BRAF(wt)-IRES-GFP, BRAF(V600E)-IRES-GFP, or empty-IRES-GFP. Gated GFP(dim) cells were flow sorted for use in subsequent studies. (C) Affymetrix gene expression profiling of selected genes classically implicated in immune modulation of the tumor microenvironment. Transduced and sorted dermal melanocytes (36 hours following transduction) or HS294T cells (24 hours post-transduction) were analyzed, and the heatmap shown represents color-coded expression levels for each sample compared to GFP-transduced controls. (D) Luminex assay showing cytokine profiles in supernatants of transduced dermal melanocyte preparations cultured for 5 days. Results are representative of 4 independent experiments. ND, not detected.

To identify differentially expressed genes between untreated and IL-1 treated TAFs, we applied modified paired two-sample t-tests using Limma package. The beta-uniform mixture (BUM) model, described by Pounds and Morris (50), was used to control the false discovery rate (FDR). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using the method of Subramanian et al. All of the tests in Figures 2, 3, and 4 are 1-sided t-tests, asterisks indicate p-values of <0.05, if not explicitly provided. Tests in Figure 5 are paired 1-sided t-tests.

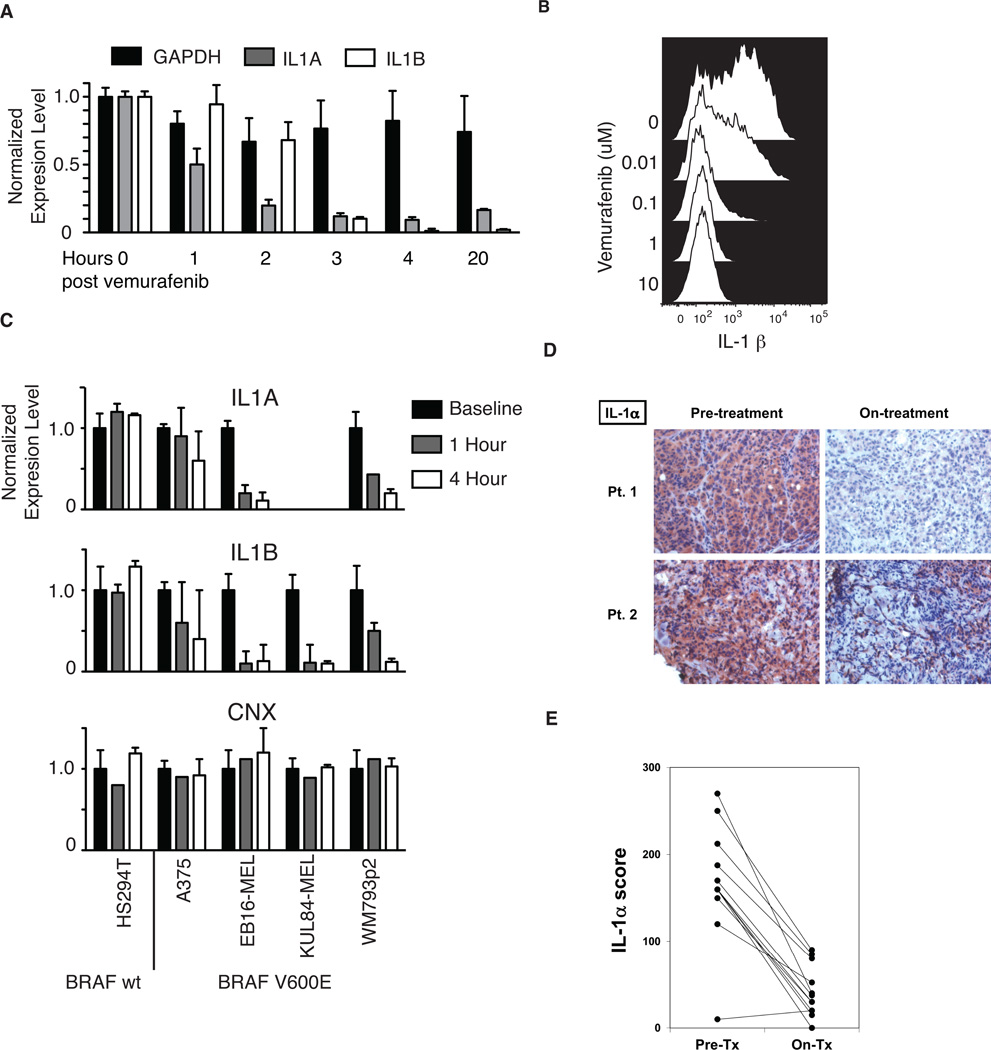

Figure 2. Inhibition of BRAF(V600E) abrogates IL-1 expression in melanoma cell lines and patient tumors.

(A) RT-PCR analysis of IL-1α, IL-1β and GAPDH transcripts in BRAF(V600E)-positive WM793p2 cells at different time points following treatment with 1µM vemurafenib. (B) Flow cytometric analysis showing intracellular IL-1β protein expression in live cell-gated WM793p2 cells 48 hours following treatment with titrated doses of PLX4032. (C) RT-PCR analysis showing transcript levels of IL1α, IL1β and CNX in five vemurafenib-treated melanoma cell lines expressing either wt BRAF (HS294T) or V600E-mutated BRAF (A375, EB16-MEL, KUL84-MEL, WM793p2). Transcript levels were normalized to GAPDH expression and adjusted to corresponding baseline samples. (D) Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of IL-1α protein expression in tumor biopsies resected from two representative metastatic melanoma patients harboring the BRAF(V600E) mutation, both prior to and on vemurafenib treatment. (E) Summary of changes to IL-1α expression in response to vemurafenib treatment, as assessed by IHC analysis of 12 total melanoma patient tumor biopsy pairs analyzed.

Figure 3. IL-1α treated tumor-associated fibroblasts induce suppression of melanoma-specific CD8+ T-cells.

(A) Tissue sections from two representative melanoma metastases labeled with anti-αSMA antibody and visualized with peroxidase immunostaining. Red-brown color shows staining of αSMA-positive tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAF), asterisks denote tumor cells, arrows indicate tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), and ‘V’ denotes tumor vasculature. (B) Interferon-gamma release by MART-1 reactive TIL stimulated with MART-1 peptide-pulsed T2 cells in the presence or absence of untreated or IL-1α treated melanoma TAFs, with or without the addition of IL-1 neutralizing antibodies. Data are representative of six different TAF lines analyzed and three experimental replicates. (C) Frequency of CD107a-positive TIL following co-culture with MART-1 peptide-pulsed dermal fibroblasts pretreated with or without IL-1α, as determined by flow cytometry. Data from 2 different melanoma patient TIL are shown, and are representative of 2 independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05); ns, not significant.

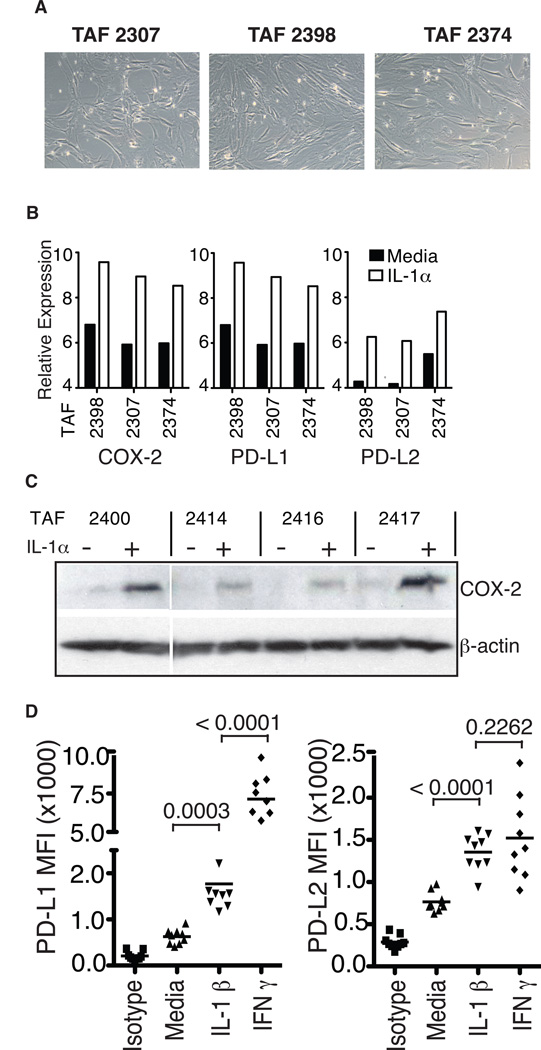

Figure 4. IL-1α upregulates the expression of immunosuppressive genes in melanoma-derived TAFs.

(A) Phase contrast images of three short-term cultured TAFs derived from melanoma patient biopsies (10X). (B) Normalized relative transcriptional expression levels of COX-2, PD-L1 and PD-L2 in 24 h IL-1α treated or untreated TAFs, as analyzed by Affymetrix gene expression array. (C) Western blot analysis showing COX-2 and β-actin protein expression in four additional patient-derived TAF lines, prior to and 24 hours following treatment with IL-1α. (D) Surface expression of PD-1 ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 on TAFs 24 hours after treatment with IL-1α or IFN-γ, as determined by flow cytometry. Data from 9 different melanoma-derived TAF lines are shown. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05); ns, not significant.

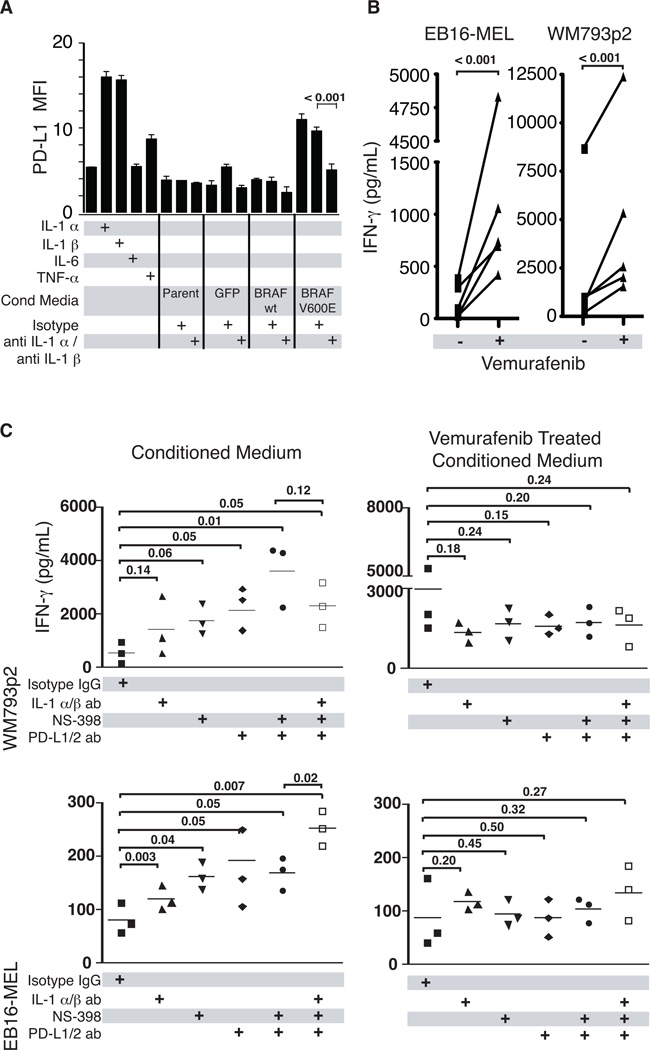

Figure 5. BRAF(V600E) can induce T-cell suppression through IL-1 mediated upregulation of PD-1 ligands and COX-2 on TAFs.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of surface PD-L1 expression on TAFs cultured overnight with IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, or conditioned medium from cultured primary melanocytes transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing BRAF(wt)-GFP, BRAF(V600E)-GFP, or GFP alone. As indicated, conditioned media experiments were also performed in the presence of isotype control or anti-IL1α and anti-IL1β blocking antibodies. (B) Interferon-gamma release by T2-stimulated MART-1 reactive TIL in the presence of melanoma patient-derived TAFs previously exposed to conditioned media from BRAF(V600E) mutant-expressing melanoma cell lines that were either untreated or treated with the BRAF(V600E) inhibitor vemurafenib. Results from five different TAF lines are shown. (C) To assess the relative contributions of IL-1α/β, COX-2, and PD-1 ligands in the induction of T-cell suppression, three melanoma TAF lines were pre-treated with conditioned media from untreated or vemurafenib-treated melanoma cell lines (WM793p2 and EB16-MEL), in the presence of either IL-1α/β blocking antibodies or the COX-2 inhibitor NS398. Pre-conditioned TAFs were then incubated with MART-1-reactive TIL and MART-1 peptide-pulsed T2 cells in the presence of isotype control antibody or antibodies specific for PD-L1 and PD-L2. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05); ns, not significant.

Western Blotting

Cell lysates were prepared from cultured TAFs. Protein content was normalized using the BCA method (Thermo-Fischer Rockford, IL). Protein samples were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane (BIO-RAD Hercules, CA). Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk, and incubated with primary anti COX-2 at 1:1000 dilution overnight at 4°C. Washed membranes were incubated with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 hours at RT prior to chemiluminescent detection (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining for IL-1α, IL-1β, and αSMA was performed using the avidin-biotin complex kit (Vector Laboratories) on melanoma patient tumor samples prior to and following treatment with vemurafenib, or on untreated patient tumor biopsies. IHC staining was appropriately optimized in our lab, and control tissues were systemically used to avoid false-negative or false-positive staining. Percentages and staining intensities (0 to 3, minimum to maximum) of stained tumor cells were quantitated using microscopy and blinded pathological examination. IHC scores were calculated using the following equation: percentage positively stained cells × intensity score × 100.

Flow cytometric analyses

Analysis of surface antigens on melanoma cell lines and melanocytes was carried out by standard flow cytometry methods. Antibodies were obtained from the indicated suppliers, From: PD-L1 (M1H1), PD-L2 (MIH18), AF647 labeled anti-rabbit IgG fabs (eBiosciences San Diego, CA); CD8 (RPA-T8), Ki-67 (B56), CD25 (M-A251), IL-1α (AS5), IL-1β (AS10), CD90 (5E10), (BD Biosciences); PD-1 (EH12.2H7) (Biolegend San Diego, CA); MCSP (EP-1) (Miltenyi Biotec,Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and B-raf (EP152Y) (Epitomics Burlingame, CA). Intracellular antigens were stained after fixation and permeabilization using Foxp3 intracellular staining Kit (ebiosciences). Stained cells were analyzed using a FACScanto II flow cytometer, or a FacsCaliber flow cytometer (BD Biosciences San Jose CA). Data was analyzed using Flowjo analysis software (Treestar Ashland OR).

Cytokine detection

Supernatants from cell lines or co-cultures were collected and aliquots stored at −20°C prior to detection of IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, by standard ELISA methods according to manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems Minneapolis, MN). For some experiments supernatants were analyzed for multiple cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-8, IL-6, IFN-γ, TNF-α) by multiplex Luminex assays according to manufacturer’s instructions (Millipore Bedford, MA).

TIL suppression assay

Foreskin-derived dermal cell preparations or melanoma TAFs were plated into 96-well flat bottom plates and cultured until 80% confluent. Interleukin-1 α/β (1 ng/ml) or conditioned medium was added overnight. To test direct presentation, wells were washed prior to Mart-1 27L (AAGIGILTV) peptide pulsing (100 nM, 3hrs, 37°C, serum free medium). For third party cell stimulation, T2 cells or irradiated CD40L activated B cells were pulsed with peptide and added with 1E5 Til at a 1:1 ratio to cultures. Proliferation was inferred by expression of cell cycle protein Ki-67 in the Mart-1 tetramer binding CD8 T cells. Supernatants were collected at the indicated times during the coculture for IFN-γ analysis as described above. Melanoma cell line conditioned medium was obtained from confluent cell cultures in T150 flasks containing 13 mL of medium after 24 hours with and without treatment with 1 µM vemurafinib (Plexxikon Berkeley, CA). This treatment condition did not significantly alter the cell number/flask. Medium was centrifuged and 0.22 µM filtered prior to use in assays. Blockade of PD-L1 and PD-L2 was achieved with the use of purified Azide free PD-L1 (M1H1), PD-L2 (MIH18) antibodies (BD Biosciences) at 1.5 µg/mL doses. The COX-2 inhibitor NS398 (Cayman Chemicals Ann Arbor, Michigan) and DMSO vehicle controls were used at the time of IL-1 treatment at 50 µM. IL-1α and IL-1β neutralizing antibodies (R&D Systems) were used at 20ug/mL each; isotype antibody (R&D Systems) controls were included where indicated.

RESULTS

Expression of BRAF (V600E) upregulates IL-1α/β in melanocytes and melanoma cells

In order to assess the downstream gene transcription profile induced by BRAF(V600E), we developed a lentiviral vector-based system to enforce its expression in primary human melanocytes, thus mimicking one of the presumed earliest events in melanomagenesis. A CMV promoter was used to drive expression of either wild-type (WT) BRAF or mutated BRAF(V600E), and eGFP expression driven by a downstream IRES element allowed for the flow cytometric sorting of transduced cells (Fig. 1A). As expected, GFP fluorescence correlated with expression of BRAF protein, and GFPlo cells were sorted at 36 hours post-transduction and analyzed by Affymetrix microarray for changes in gene expression (Fig. 1B).

Ectopic expression of BRAF(V600E) in melanocytes specifically upregulated the transcription of a number of immunomodulatory genes (Fig. 1C). In addition to upregulating the expression of genes previously linked to oncogenic BRAF, including IL-6, IL-8, and VEGF, BRAF(V600E) also significantly increased the transcription of IL-1α and IL-1β genes (24, 25). Increased production of these cytokines was also confirmed at the protein level by analyzing culture supernatants of transduced melanocytes (Fig. 1D). To determine whether these results were relevant for melanoma tumor cells, we also transduced the HS294T melanoma cell line, which naturally expresses only wild-type BRAF. As shown in Fig. 1C, expression of BRAF(V600E) induced similarly elevated levels of IL-1α and β transcripts compared to HS294T cells transduced with WT BRAF, or empty vector. Although the induced gene expression patterns between primary melanocytes and HS294T cells showed only partial overlap, the common upregulation of IL-1 in both cell types led us to suspect that BRAF(V600E) may be linked to IL-1-mediated inflammation in melanoma.

IL-1α and IL-1β expression has been widely documented in melanoma; however, some discrepancies exist in reports of its prevalence, in which IL-1α or β positivity has ranged from ~10% to 70% of samples analyzed (26–28). Our own tissue microarray analysis of 147 human tumor samples showed that IL-1α is expressed at all stages of melanoma and in benign nevi at a frequency ranging from 63 to 88%, whereas IL-1β is expressed at a significantly lower overall frequency in advanced melanoma (~13%), and not at all in nevi (Fig. S1A). However, IL-1 expression was not strictly associated with tumors harboring BRAF(V600E) mutations, as seen both in patient tumor samples and within a panel of human melanoma cell lines (Fig. S1B–L). The observed expression of IL-1 in melanoma tumors lacking the BRAF(V600E) mutation suggests that other mechanisms, potentially including alternate pathways of MAPK pathway activation, may also induce its expression.

Pharmacologic inhibition of BRAF (V600E) abrogates IL-1 production in melanoma

In order to test the hypothesis that BRAF(V600E) was responsible for driving IL-1 production in melanoma, we measured the production of IL-1 by BRAF(V600E)-positive melanoma cell lines prior to and following exposure to the BRAF(V600E)-specific inhibitor vemurafenib (also known as PLX4032). As shown in Fig. 2A, 1µM vemurafenib treatment of the WM793p2 cell line resulted in a progressive reduction in both IL-1α and IL-1β mRNA transcripts, which reached maximal downregulation within 3–4 hours. Consistent with this result, vemurafenib treatment reduced IL-1β protein to nearly undetectable levels at doses as low as 0.1 µM, as demonstrated by intracellular staining and flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 2B). We also tested four other IL-1-producing melanoma cell lines, three of which were positive for V600E (A375, EB16-MEL and KUL84-MEL), and one which expressed wt BRAF (HS294T). As shown in Fig. 2C, only in BRAF (V600E)-expressing cell lines was IL-1α and β production reduced in response to vemurafenib treatment. Collectively, these results demonstrated that BRAF(V600E) inhibition by vemurafenib could effectively reduce IL-1 production in a V600E-positive melanoma cell lines at doses considerably lower (<100X) than those typically found in the serum of vemurafenib-treated patients (8). Control of IL-1α expression by BRAF was also confirmed using direct shRNA-mediated knockdown of BRAF in a BRAF(V600E)-positive melanoma line (Fig. S2).

For in vivo confirmation, NOD-SCID mice xenogeneically engrafted with human A375 tumors were treated with low doses of PLX4720 for 3 consecutive days, and growing tumors were excised for analysis (Fig. S3A). As shown by qRT-PCR, BRAF (V600E) inhibition reduced human IL-1α and IL-1β transcripts to nearly undetectable levels, confirming the in vitro findings. Furthermore, consistent with the in vitro BRAF expression studies, transcription of IL-8 but not that of other control genes, was also abrogated (Fig. S3B).

Tumor biopsies were also obtained from 12 Stage IV BRAF(V600E)-positive melanoma patients, both prior to and during vemurafenib treatment. Immunohistochemical staining for IL-1α and IL-1β showed that 11 of 12 tumors stained positively for IL-1α prior to treatment, and that all 11 patients demonstrated reductions in IL-1α protein levels on-treatment (Figs. 2D and 2E). As expected, IL-1β was much less prevalent, only being sparsely expressed by two of the tumors prior to treatment; however, both tumors showed reduced levels during vemurafenib treatment (not shown). These data collectively show that BRAF(V600E)-specific inhibition can block the transcription and production of IL-1 in melanoma, thus altering the cytokine milieu within the tumor microenvironment.

IL-1 treated tumor-associated fibroblasts induce suppression of melanoma-specific CD8+ T-cells

We next explored the hypothesis that IL-1 production within the melanoma tumor microenvironment could be inducing functional T-cell suppression indirectly through resident stromal fibroblasts. In melanoma tumor samples, TIL are frequently found in close proximity to TAFs recognized by morphology or smooth muscle actin (SMA) expression; these TAFs surround tumor vessels, and often form physical barriers between TIL and tumor cells (Fig. 3A). Considering the importance of TIL for mediating tumor regressions in melanoma patients (29, 30), and their proximity to TAFs within the tumor microenvironment, we next tested whether TAFs were capable of suppressing CD8+ T-cell function and whether IL-1 could impact this suppression.

TAFs were isolated from cultured digests of human melanoma patient metastases by CD90 bead positive selection. Melanoma TAFs from 6 different patients were then tested for suppressive function in co-culture with MART-1-specific TIL exposed to MART-1 peptide-pulsed T2 stimulator cells. Whereas untreated TAFs demonstrated minor suppression of TIL cytokine production, IL-1α pretreatment reduced IFN-γ production by an average of 4 to 5-fold. Furthermore, antibody-mediated neutralization of IL-1α/β abrogated the suppressive effect of IL-1 in combination with TAFs (Fig. 3B). T-cell function was also assessed by measuring antigen-specific degranulation based on CD107a surface staining. Consistent with the suppressive effects on cytokine production, two different MART-1-reactive TIL lines were significantly inhibited in their response to MART-1 peptide presentation in the presence of IL-1α pretreated fibroblasts, as compared to untreated fibroblasts (Fig. 3C). Collectively, these results suggest that IL-1α was capable of driving functional, antigen-specific CTL suppression indirectly though the activation of melanoma-derived TAFs.

IL-1 upregulates expression of immunosuppressive genes in melanoma-derived TAFs

Since understanding the basic mechanisms of IL-1 induced suppression by TAFs could inform more general clinical strategies to improve immunotherapies, we next performed a global transcriptional analysis of TAFs treated with IL-1α, with our goal being to identify candidate immunomodulators that could mediate T-cell suppression in this context. Human TAFs were isolated and purified from three different melanoma patient tumors derived from metastases of lymph node, lung, and soft tissue (Fig. 4A). The TAFs were then treated with recombinant human IL-1α in culture for 24 hours and mRNA was isolated for Affymetrix-based gene expression analysis.

We identified 197 genes that were differentially expressed by TAFs in response to IL-1α treatment, most of which were upregulated in all 3 TAFs (Fig. S4A). GSEA analysis revealed a strong enrichment for genes associated with NF-κB activation and interferon responses (Fig. S4B). These included a number of genes with immune-related functions, including multiple chemokines as well as several cytokines. Importantly, a number of the IL-1α induced genes were known mediators of T-cell suppression (Fig. S4C, Supplemental references 11–20). For functional studies, we chose to focus on three of these genes: PTGS2 (also known as COX-2), and the PD-1 ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 (Fig. 4B). All three of these genes were among the most highly upregulated, are known to exert powerful suppressive effects on T-cells, and their mechanisms of action have been relatively well-characterized in multiple cancer types (31, 32).

Augmented expression of the three gene products in response to IL-1α treatment was also confirmed in multiple, independently-derived melanoma TAFs: Western blot analysis showed increased levels of COX-2 protein (Fig. 4C), and flow cytometric analysis demonstrated increased TAF surface expression levels of both PD-L1 and PD-L2 following IL-1α treatment (Figs. 4D and S5). IL-1α and IL-1β were both shown to be very potent inducers of PD-1 ligand expression, demonstrating activity at concentrations as low as 1 pg/ml (Fig. S6). Furthermore, although IL-1α/β was not as effective as IFN-γ at inducing expression of PD-L1, it was equally effective at inducing expression of the higher affinity PD-1 ligand PD-L2 in all 9 TAFs analyzed (Figs. 4D and S5). Collectively, these results demonstrate that TAFs exposed to low concentrations of IL-1α/β respond by rapidly stimulating the expression of at least three molecules known to directly induce CTL suppression.

BRAF (V600E) induces T-cell suppression through IL-1 mediated upregulation of PD-1 ligands and COX-2 on TAFs

We next assessed whether PD-1 ligand upregulation by TAFs can be directly attributed to IL-1 production induced by BRAF(V600E). In order establish this link, we collected culture supernatants from melanocytes that were stably transduced to express either WT or mutated BRAF, and then exposed these supernatants to melanoma-derived TAFs overnight. Flow analysis revealed that only conditioned media from BRAF(V600E)-transduced melanocytes, but not those transduced with WT BRAF or GFP vectors, was capable of upregulating surface expression of PD-L1 (Fig. 5A). Importantly, IL-1α/β antibody blockade abrogated this PD-L1 expression, demonstrating that IL-1 was the mediator responsible for PD-1 ligand upregulation (Fig. 5A).

In order to determine whether pharmacologic BRAF(V600E) inhibition could relieve TAF-mediated T-cell suppression, we exposed six different melanoma-derived TAFs to supernatants from BRAF(V600E)-positive melanoma cell lines that were either untreated or treated with vemurafenib. Following overnight exposure to these supernatants, TAFs were co-cultured with MART-1-specific, PD-1 positive TIL and MART-1 peptide pulsed T2 target cells for 18 hours. The following day, culture supernatants were assayed for IFN-γ production. As shown in Fig. 5B, vemurafenib treatment resulted in a significant augmentation of T-cell IFN-γ production in all six TAFs analyzed. To ascertain whether IL-1α/β, COX-2, or PD-1 ligands played a role in mediating this suppression, we next performed a similar experiment in the presence or absence of IL-1α/β or PD-L1/PD-L2 antibody blockade, or the COX-2 inhibitor NS398. Antibody neutralization of IL-1α/β in melanoma cell line supernatants partially relieved the MART-1 TIL functional suppression observed in co-cultures with TAFs (Fig. 5C). In addition, antibody neutralization of PD-1 ligands and COX-2 also partly relieved TAF-mediated suppression, whereas combined the neutralization of IL-1α/β and PD-1 ligands with COX-2 inhibition augmented T-cell cytokine production even further. Although there was some variability in the extent of T-cell suppression mediated by the different TAF lines, overall the data were consistent with IL-1 mediating T-cell suppression at least partially through TAF upregulation of PD-1 ligands and COX-2. As expected, pretreatment of the melanoma cell lines with vemurafenib rendered IL-1α/β blockade, PD-1 ligand blockade and COX-2 inhibition ineffective at facilitating increased cytokine secretion by T cells (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these experiments support a model of IL-1 induced T-cell suppression that is mediated through stromal TAFs and is sensitive to pharmacologic BRAF(V600E)-specific inhibition (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Model of BRAF(V600E)-mediated immune suppression by TAFs in the melanoma tumor microenvironment.

Illustration of proposed mechanistic model showing how constitutively activated BRAF(V600E) in melanoma tumor cells may initiate and sustain T-cell suppression in vivo. In this model, T-cell suppression is manifested by tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAFs) that upregulate COX-2 and PD-1 ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 in response to BRAF(V600E)-induced IL-1α/β production by melanoma cells. Targeted therapies that inhibit BRAF(V600E) could abrogate IL-1α/β production by tumor cells, thus interfering with the cellular crosstalk leading to TAF-mediated immune suppression.

DISCUSSION

Starting with the observation that enforced expression of BRAF(V600E) in human melanocytes could induce the transcription of IL-1α and β genes, we subsequently found that the V600E-specific inhibitor vemurafenib could conversely block IL-1 protein production in human melanoma cell lines and in melanoma tumor biopsies derived from patients undergoing inhibitor treatment. We further observed that IL-1 was an important regulator of immune suppression as mediated by tumor-associated stromal fibroblast cells (TAFs), which could exert potent inhibitory effects on melanoma antigen-specific CTLs following exposure to IL-1α or β. Treatment of human melanoma-derived TAFs with recombinant IL-1α/β led to upregulated transcription of several genes known to manifest immune suppression, and we showed that COX-2, PD-L1 and PD-L2 contributed to the induction of functional T-cell inhibition. This study delineates an important and novel link between oncogene activation in tumors and the resulting downstream effects on inflammation and immune suppression within the tumor microenvironment.

Over the past decade, a number of small molecule inhibitors that target elements of the MAPK pathway and its downstream targets MEK and ERK have been tested in experimental clinical trials for cancer patients(33, 34). Such pathway inhibitors have adverse off-target effects on immune cells that can result in lymphopenia and increased frequency of infections (35–37). Since T cells require the MAPK pathway for antigen recognition and anti-tumor function, they are particularly sensitive to these off-target effects (38, 39). Furthermore, strong evidence has been accumulating that the immune system can make a critical contribution to antitumor responses even in the context of non-immunotherapeutic treatments (40–43), with the emerging paradigm being that an intact immune system contributes significantly to the outcome of treatment, and may be critical for clearance of drug-resistant tumor cells and for prevention of recurrences (44). These findings have led many to propose combining BRAF(V600E) inhibition with immunotherapies to increase response rates, and our data suggests that this combination approach may show therapeutic synergy (24, 45, 46). Recent clinical evidence suggest that Vemurafenib and GSK2118436 therapy enhances CD8+ T cell infiltration of the tumor mass, which correlates with the degree of tumor shrinkage (47). This result is consistent with our findings, but it remains to be determined whether this clinical effect is due directly to V600E inhibitor-induced reduction of immune suppression within the tumor microenvironment, or to other factors.

Our study identifies BRAF(V600E)-induced IL-1 as being a key mediator of immune suppression in melanoma. Unlike other cytokines which impact T-cells directly, IL-1 reinforces immune suppression indirectly through the stimulation of melanoma TAFs. A number of recent studies have highlighted the importance of stromal TAFs in promoting tumor cell survival and evasion of NK cell-mediated antitumor immunity (7). Our results are experimentally consistent with these findings and show that IL-1α and β can induce melanoma TAFs to directly inhibit the antitumor function of melanoma antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Gene expression analysis showed that this IL-1-mediated suppression is likely mediated by a host of factors known to affect T-cell function as well as that of other lymphocytes (listed in Fig S4B), including but not limited to TAF expression of PD-1 ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2, and COX-2. Importantly, the location of TAFs within the architecture of the melanoma tumor microenvironment, frequently lining tumor vasculature and/or forming a physical barrier between TIL and tumor cells, suggests that TAFs are ideally located to mediate immune cell suppression in vivo.

Perhaps the most crucial aspect of this study is the finding that pharmacologic inhibition of BRAF(V600E) in melanoma cells can relieve TAF-mediated suppression of immune cell function and largely restore antitumor T-cell responses. These results are consistent with other recent studies, and collectively these results have important clinical implications that strongly support the notion of combining BRAF(V600E)-specific inhibitors with immune-based therapies. The emerging link between MAPK pathway activation and immune suppression, combined with the lack of off-target effects shown by mutated kinase-targeted agents, suggests that such combination approaches may show therapeutic synergy and result in significantly better and more durable clinical responses in V600E-positive melanoma patients. Furthermore, our findings also support the notion that patients harboring non-BRAF mutated tumors may benefit from treatments that aim to combine immunotherapeutic approaches with IL-1 blockade.

Supplementary Material

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

This study implicates IL-1α and IL-1β as BRAF(V600E)-regulated genes that play a key immunosuppressive role within the melanoma tumor microenvironment. We identified a transcriptional program of response to IL-1 by melanoma tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAF), including upregulation of multiple known immunosuppressive genes such as PD-1 ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) and COX-2, and demonstrated that IL-1-responding TAFs suppress the immune function of tumor-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL). The clinical BRAF(V600E) inhibitor vemurafinib blocked IL-1α production in multiple melanoma cell lines tested, as well as in tumors derived from BRAF(V600E)-positive melanoma patients undergoing vemurafenib treatment. These results highlight the role of oncogenic BRAF in the induction of immune suppression in melanoma, and provide a strong rationale to combine the use of BRAF inhibitors with active immunotherapy approaches for the treatment of metastatic melanoma patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Luis Vence and Jonathan Kurie for critical reading of this manuscript, and Lyn McDivitt Duncan of Massachusetts General Hospital for providing a melanoma progression TMA. Funding: Support for this work was provided in part from CPRIT grant RP110248, SPORE grant CA093459, CCSG grant NCI#P30CA16672 and a charitable grant from Transocean.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: Michael A. Davies has served on advisory boards and received research funding from Roche-Genentech and GlaxoSmithKline.

None of the authors have competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: more mechanisms for inhibiting antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59:1593–1600. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0855-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poschke I, Mougiakakos D, Kiessling R. Camouflage and sabotage: tumor escape from the immune system. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1012-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lizee G, Cantu MA, Hwu P. Less yin, more yang: confronting the barriers to cancer immunotherapy. Clinical cancer research. 2007;13:5250–5255. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lizee G, Radvanyi LG, Overwijk WW, Hwu P. Improving antitumor immune responses by circumventing immunoregulatory cells and mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4794–4803. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lizee G, Radvanyi LG, Overwijk WW, Hwu P. Immunosuppression in melanoma immunotherapy: potential opportunities for intervention. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2359s–2365s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nazareth MR, Broderick L, Simpson-Abelson MR, Kelleher RJ, Jr, Yokota SJ, Bankert RB. Characterization of human lung tumor-associated fibroblasts and their ability to modulate the activation of tumor-associated T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:5552–5562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balsamo M, Scordamaglia F, Pietra G, Manzini C, Cantoni C, Boitano M, et al. Melanoma-associated fibroblasts modulate NK cell phenotype and antitumor cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906481106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kraman M, Bambrough PJ, Arnold JN, Roberts EW, Magiera L, Jones JO, et al. Suppression of antitumor immunity by stromal cells expressing fibroblast activation protein-alpha. Science. 2010;330:827–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1195300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhowmick NA, Neilson EG, Moses HL. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature. 2004;432:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature03096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pietras K, Ostman A. Hallmarks of cancer: interactions with the tumor stroma. Experimental cell research. 2010;316:1324–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muerkoster S, Wegehenkel K, Arlt A, Witt M, Sipos B, Kruse ML, et al. Tumor stroma interactions induce chemoresistance in pancreatic ductal carcinoma cells involving increased secretion and paracrine effects of nitric oxide and interleukin-1beta. Cancer research. 2004;64:1331–1337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crawford Y, Kasman I, Yu L, Zhong C, Wu X, Modrusan Z, et al. PDGF-C mediates the angiogenic and tumorigenic properties of fibroblasts associated with tumors refractory to anti-VEGF treatment. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang W, Li Q, Yamada T, Matsumoto K, Matsumoto I, Oda M, et al. Crosstalk to stromal fibroblasts induces resistance of lung cancer to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2009;15:6630–6638. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liao D, Luo Y, Markowitz D, Xiang R, Reisfeld RA. Cancer associated fibroblasts promote tumor growth and metastasis by modulating the tumor immune microenvironment in a 4T1 murine breast cancer model. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okazaki M, Yoshimura K, Uchida G, Harii K. Correlation between age and the secretions of melanocyte-stimulating cytokines in cultured keratinocytes and fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(Suppl 2):23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erez N, Truitt M, Olson P, Arron ST, Hanahan D. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Are Activated in Incipient Neoplasia to Orchestrate Tumor-Promoting Inflammation in an NF-kappaB-Dependent Manner. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apte RN, Voronov E. Is interleukin-1 a good or bad 'guy' in tumor immunobiology and immunotherapy? Immunol Rev. 2008;222:222–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bunt SK, Sinha P, Clements VK, Leips J, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Inflammation induces myeloid-derived suppressor cells that facilitate tumor progression. Journal of immunology. 2006;176:284–290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bunt SK, Yang L, Sinha P, Clements VK, Leips J, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Reduced inflammation in the tumor microenvironment delays the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and limits tumor progression. Cancer research. 2007;67:10019–10026. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen CJ, Kono H, Golenbock D, Reed G, Akira S, Rock KL. Identification of a key pathway required for the sterile inflammatory response triggered by dying cells. Nat Med. 2007;13:851–856. doi: 10.1038/nm1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen I, Rider P, Carmi Y, Braiman A, Dotan S, White MR, et al. Differential release of chromatin-bound IL-1alpha discriminates between necrotic and apoptotic cell death by the ability to induce sterile inflammation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:2574–2579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915018107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ancrile B, Lim KH, Counter CM. Oncogenic Ras-induced secretion of IL6 is required for tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1714–1719. doi: 10.1101/gad.1549407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beaupre DM, Talpaz M, Marini FC, 3rd, Cristiano RJ, Roth JA, Estrov Z, et al. Autocrine interleukin-1beta production in leukemia: evidence for the involvement of mutated RAS. Cancer research. 1999;59:2971–2980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sumimoto H, Imabayashi F, Iwata T, Kawakami Y. The BRAF-MAPK signaling pathway is essential for cancer-immune evasion in human melanoma cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1651–1656. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Packer LM, East P, Reis-Filho JS, Marais R. Identification of direct transcriptional targets of (V600E)BRAF/MEK signalling in melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009;22:785–798. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lazar-Molnar E, Hegyesi H, Toth S, Falus A. Autocrine and paracrine regulation by cytokines and growth factors in melanoma. Cytokine. 2000;12:547–554. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kholmanskikh O, van Baren N, Brasseur F, Ottaviani S, Vanacker J, Arts N, et al. Interleukins 1alpha and 1beta secreted by some melanoma cell lines strongly reduce expression of MITF-M and melanocyte differentiation antigens. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:1625–1636. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyler DS, Francis GM, Frederick M, Tran AH, Ordonez NG, Smith JL, et al. Interleukin-1 production in tumor cells of human melanoma surgical specimens. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1995;15:331–340. doi: 10.1089/jir.1995.15.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Topalian SL, Restifo NP, et al. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:2346–2357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Besser MJ, Shapira-Frommer R, Treves AJ, Zippel D, Itzhaki O, Hershkovitz L, et al. Clinical responses in a phase II study using adoptive transfer of short-term cultured tumor infiltration lymphocytes in metastatic melanoma patients. Clinical cancer research. 2010;16:2646–2655. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lukens JR, Cruise MW, Lassen MG, Hahn YS. Blockade of PD-1/B7-H1 interaction restores effector CD8+ T cell responses in a hepatitis C virus core murine model. J Immunol. 2008;180:4875–4884. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okano M, Sugata Y, Fujiwara T, Matsumoto R, Nishibori M, Shimizu K, et al. E prostanoid 2 (EP2)/EP4-mediated suppression of antigen-specific human T-cell responses by prostaglandin E2. Immunology. 2006;118:343–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02376.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dummer R, Robert C, Chapman P, Sosman J, Middleton MR, Bastholt L, et al. AZD6244 (ARR-142886) vs temozolomide (TMZ) in patients with advanced melanoma: an open-label, randomized, multicenter, phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:9033. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adjei AA, Cohen RB, Franklin W, Morris C, Wilson D, Molina JR, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral, small-molecule mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in patients with advanced cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2139–2146. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schutz FA, Je Y, Choueiri TK. Hematologic toxicities in cancer patients treated with the multi-tyrosine kinase sorafenib: A meta-analysis of clinical trials. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weichsel R, Dix C, Wooldridge L, Clement M, Fenton-May A, Sewell AK, et al. Profound inhibition of antigen-specific T-cell effector functions by dasatinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2484–2491. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rohon P, Porkka K, Mustjoki S. Immunoprofiling of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia at diagnosis and during tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Eur J Haematol. 85:387–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dong C, Davis RJ, Flavell RA. MAP kinases in the immune response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:55–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.091301.131133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bendall SC, Simonds EF, Qiu P, Amirel AD, Krutzik PO, Finck R, et al. Single-cell mass cytometry of differential immune and drug responses across a human hematopoietic continuum. Science. 2011;332:687–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1198704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poschke I, Mougiakakos D, Hansson J, Masucci GV, Kiessling R. Immature immunosuppressive CD14+HLA-DR-/low cells in melanoma patients are Stat3hi and overexpress CD80, CD83, and DC-sign. Cancer Res. 70:4335–4345. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green DR, Ferguson T, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunogenic and tolerogenic cell death. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:353–363. doi: 10.1038/nri2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kulke MH, Vance EA. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:215–218. doi: 10.1086/514542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kepp O, Tesniere A, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. The immunogenicity of tumor cell death. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21:71–76. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32831bc375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zitvogel L, Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Andre F, Tesniere A, Kroemer G. The anticancer immune response: indispensable for therapeutic success? J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1991–2001. doi: 10.1172/JCI35180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ott PA, Adams S. Small-molecule protein kinase inhibitors and their effects on the immune system: implications for cancer treatment. Immunotherapy. 2011;3:213–227. doi: 10.2217/imt.10.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boni A, Cogdill AP, Dang P, Udayakumar D, Njauw CN, Sloss CM, et al. Selective BRAFV600E inhibition enhances T-cell recognition of melanoma without affecting lymphocyte function. Cancer research. 2010;70:5213–5219. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilmott JS, Long GV, Howle JR, Haydu LE, Sharma R, Thompson JF, et al. Selective BRAF inhibitors induce marked T cell infiltration into human metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y, Liu S, Hernandez J, Vence L, Hwu P, Radvanyi L. MART-1-Specific Melanoma Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes Maintaining CD28 Expression Have Improved Survival and Expansion Capability Following Antigenic Restimulation In Vitro. J Immunol. 184:452–465. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wellbrock C, Ogilvie L, Hedley D, Karasarides M, Martin J, Niculescu-Duvaz D, et al. V599EB-RAF is an oncogene in melanocytes. Cancer research. 2004;64:2338–2342. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pounds S, Morris SW. Estimating the occurrence of false positives and false negatives in microarray studies by approximating and partitioning the empirical distribution of p-values. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1236–1242. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.