Abstract

Background

Pronounced differences in drinking behavior exist between African Americans and European Americans. Disinhibited personality characteristics are widely studied risk factors for alcohol use outcomes. Longitudinal studies of children have not examined racial differences in these characteristics, in their rates of change, or whether these changes differentially relate to adolescent alcohol use.

Methods

Latent growth curve modeling was performed on seven annual waves of data on 447 African American and European American 8- and 10-year-old children followed into adolescence as part of the Tween to Teen Project. Both mother and child data were examined.

Results

European Americans had higher initial levels of (β = 0.22, p < .001) and greater growth in sensation seeking (β = 0.16, p < .05) compared to African Americans. However, African American children had higher initial levels of impulsivity compared to European American children (βs = −0.27 and −0.16, p < .01). Higher initial levels of sensation seeking (β = 0.18, p < .01) and greater growth in both sensation seeking (β = 0.24, p < .01) and impulsivity (βs = 0.30 to 0.34, p < .01) related to subsequent frequency of alcohol use. The association between race and alcohol use was partially mediated by initial levels of sensation seeking (β = 0.04, p < .05; 95% CI: 0.004 – 0.078). Additionally, sharper increases in sensation seeking predicted greater levels of subsequent alcohol use for European Americans (B = 0.33, p < .001) but not for African Americans (B = −0.15, ns).

Conclusions

This study revealed different developmental courses and important racial differences for sensation seeking and impulsivity. Findings highlight the possibility that sensation seeking at least partly drives early alcohol use for European American but not for African American adolescents.

Keywords: Sensation Seeking, Impulsivity, Adolescence, Racial Differences, Alcohol Use

African American adolescents have lower levels of alcohol involvement than European American adolescents: they are more likely to abstain from alcohol (Pemberton, Colliver, Robbins & Gfroerer, 2008), drink alcohol less frequently, and engage in less heavy drinking (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2010). Relatively little research has been conducted to move beyond these broad epidemiological findings. The goal of the current study was to examine two facets of disinhibition, sensation seeking and impulsivity, that may help explain these racial differences.

Disinhibition and Alcohol Use

Disinhibition is a broad term that has been used to describe different constructs that predispose individuals to act rashly or impulsively. A large body of research has linked aspects of this construct to the onset and escalation of alcohol use and to alcohol use disorders in adults (see reviews: Dick, Smith, Olausson, Mitchell, Leeman, O’Malley, & Sher, 2010; de Wit, 2008; Lejuez, Magidson, Mitchell, Sinha, Stevens, & de Wit, 2010) and to a variety of risk-taking behaviors in adolescence (e.g., Kiriski, Vanyukov, & Tarter, 2005; Elkins, King, McGue, & Iacono, 2006; MacPherson, Magidson, Reynolds, Kahler, & Lejuez, 2010). Recent work has shown that specific facets of disinhibition relate to different aspects of alcohol use and risk-taking behaviors in adults (Smith, Fischer, Cyders, Annus, Spillane, & McCarthy, 2007; Fischer & Smith, 2008; Cyders, Flory, Rainer, & Smith, 2009) and children/adolescents (Zapolski, Zapolski, Stairs, Settles, Combs, & Smith, 2010), highlighting the importance of examining the association between specific facets of disinhibition and alcohol use.

Changes in Disinhibition across the Lifespan

Until recently, personality characteristics were thought to be stable across the lifespan. However, increasing evidence shows that levels of personality characteristics change considerably across the lifespan, with the largest changes occurring in late adolescence (see Roberts, Walton, & Viechtbauer, 2006, for a meta-analysis). Disinhibition has been shown to peak in adolescence and to decline in adulthood (Blonigen, Hicks, Krueger, Patrick, Iacono, 2006), paralleling the “maturing out” of heavy alcohol use in adulthood (Littlefield, Sher, & Wood, 2009).

Although the majority of this research has focused on the transition from adolescence into adulthood, differences in disinhibition levels also exist between children and adolescents. Steinberg and colleagues (2008) examined cross-sectional differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity in individuals aged 10–30 and found the highest levels of sensation seeking in 12–15 year olds; in contrast, impulsivity declined steadily from ages 10 to 30. These findings suggest that different facets of disinhibition may show differing developmental trajectories in adolescence. Individual differences in these changes have also been found suggesting that the “maturation” seen in late adolescence is highly variable across individuals and is predictive of risk-taking outcomes (e.g., Johnson, Hicks, McGue, Iacono, 2007; Monahan, Steinberg, Cauffman, & Mulvey, 2009).

Racial Differences in Disinhibited Personality Characteristics

Racial differences in disinhibition have been little studied, and available findings present a complex picture. Importantly, in a review of racial differences in risk factors for adolescent drinking and drug use, Wallace and Muroff (2002) omitted any discussion of disinhibition. Cross-sectional research suggests that European American youth have higher levels of sensation seeking than African American youth (e.g., Hoyle, Stephenson, Palmgreen, Lorch, & Donohew, 2002; Russo, Stokes, Lahey, Christ, McBurnett, Loeber, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Green, 1993). Similarly, Crawford and colleagues (2003) found that European American children had higher levels of and sharper increases in sensation seeking than other ethnicities over a two-year period in middle school.

Research also suggests that sensation seeking may relate more strongly to risky behaviors among European Americans than among African Americans. For example, Cooper and colleagues (2003) found sensation seeking related to a general factor of problem behavior (i.e., risky sexual activity, substance use, delinquency, academic underachievement) for European American but not for African American adolescents. Additionally, a meta-analysis (Hittner & Swickert, 2006) found that sensation seeking related more strongly to alcohol use in studies having a higher percentage of European Americans, suggesting that sensation seeking may relate more strongly to alcohol use for this racial group.

Research on impulsivity paints a different picture. Although there is little research on this topic, studies of children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, a disorder with a high degree of impulsivity, have found that African American children have higher levels of impulsivity than European American children (e.g., DuPaul, Anastopoulos, Power, Reid, Ikeda, & McGoey, 1998; Bussing et al., 2008). The relative lack of research in this area has resulted in a lack of understanding about why these racial differences may exist, whether they exist in non-clinical populations, and the role impulsivity plays in racial differences in alcohol use. Prospective studies are needed to examine changes in disinhibited personality characteristics between African Americans and European Americans.

Aims of the Research

The current study had three aims. First, we examined change in sensation seeking and impulsivity from mid-childhood into mid-adolescence. Based on previous research, we hypothesized that sensation seeking would increase and that impulsivity would decrease over time. Second, we hypothesized that individual differences in the rate of change in disinhibition would relate prospectively to later alcohol use. For example, while sensation seeking may increase on average over time, individuals with sharper increases in sensation seeking were hypothesized to drink alcohol more frequently than those with smaller increases. The third aim of the study was to examine racial differences in both initial levels and rates of change in sensation seeking and impulsivity. Within this aim we examined the possibility that sensation seeking may mediate the association between race and alcohol use. Specifically, African Americans may have lower levels of sensation seeking which could partially explain their lower subsequent levels of alcohol use. We did not hypothesize a mediational pathway through impulsivity. We also tested whether the association between sensation seeking/impulsivity and alcohol use differed across race. We hypothesized that sensation seeking/impulsivity would relate more strongly to alcohol use for European Americans than for African Americans.

METHODS

Data were drawn from the first seven annual waves of data collection (Waves 1, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12) of an ongoing longitudinal study of the development of risk factors for early alcohol use (Tween to Teen Project). There was a 1.5 year interval between the fourth and fifth annual assessments. Human subject procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. A Certificate of Confidentiality was provided by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Procedures

Families containing an 8- or 10-year old child were selected for participation using targeted-age directory and random digit dialing (RDD) sampling of families in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania (see Donovan & Molina, 2008 for further recruitment details). Special efforts were made to ensure that race and single-mother household status were not confounded in the sample recruitment.

After describing the study to participants, parental consent and child assent were obtained. Children completed computer-assisted interviews every 6 months. Parent computer-assisted interviews were completed annually. Children were paid $15 and parents were paid $50.

Participants

Project staff identified 804 eligible families. Of these, 504 (63%) agreed to participate and 452 completed the Wave 1 interview (90% of those who agreed and 56% of those eligible). Participants did not differ significantly from non-participants on the screening variables of race, age-cohort, or mother’s education. Recruitment quotas for a diverse community sample of families were met: 73% (330/452) of the children were European American; 26% (117/452) were African American or biracial with at least one parent being African American. Biological mothers participated in all families (23% were single).

Attrition Analyses

Four hundred fifty two mothers and their children completed the baseline interviews. Four hundred and forty seven of those families were either African American or European American. By the end of the seventh annual assessment, 7.5 years after baseline, 85% of the children (n = 380), and 83% of the mothers (n = 373) were still involved in the research. Retention rates did not differ as a function of sex or cohort. However, African Americans were significantly less likely to remain in the study compared to European Americans (χ2 (1, N = 447) = 21.73, p < .0001; 72% vs. 90%). To assess attrition bias, we examined a set of 13 measures we used previously to summarize psychosocial proneness for deviance in Problem Behavior Theory (Donovan & Molina, 2008). Discontinuers differed from Continuers on just one of the 13 Wave-1 measures, which together accounted for only 1.7% of the variance in attrition (by adjusted R2).

Measures

Demographic Variables

Participant’s age (M = 9.52 years, SD = 1.02), sex (47% male), and mother’s highest level of educational attainment at the initial assessment were used as study covariates.

Race was dichotomized (African American = 0, European American = 1) and was used as a predictor variable in analyses. Participants with at least one parent who reported being African American or black were categorized as African Americans (4% bi-racial).

Sensation Seeking

Child sensation seeking was measured during the first six annual assessments using 4 items from the Zuckerman Sensation Seeking Scale (SSS-V; Zuckerman, Eysenck, & Eysenck, 1978). Children were asked to pick the statement that best fit how they feel from two forced choice options (e.g., “I like to explore new places by myself, even if it means getting lost.” vs. “I prefer a guide when I am in a place I don’t know well.”). Responses were averaged and scored so 1 = less sensation seeking option, 2 = more sensation seeking option. The average alpha for sensation seeking for African Americans was .57 (inter-item correlation = .26) and for European Americans was .59 (inter-item correlation = .26) across 6 time points (which is considered satisfactory given the short length of the scale).

Impulsivity

Child impulsivity was measured during the first six annual assessments using an abridged version of the Eysenck Impulsivity Scale (Eysenck, Easting, & Pearson, 1984). Children (8 items) and mothers (13 items) reported about the child’s impulsivity (e.g., Does the child “generally say things without stopping to think?”; 1 = no, 2 = yes). For each assessment, scores were averaged across items for each reporter (higher scores = greater impulsivity). Mother- and child-reported impulsivity were analyzed separately due to their low correlations (r’s ranged from .21 to .36, p’s < .0001). This level of correlation is consistent with a large body of research (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987). Across assessments the average alpha for impulsivity for African Americans (mother-report: α = .87, inter-item correlation = .34; child-report: α = .68, inter-item correlation = .22) and European Americans (mother-report: α = .86, inter-item correlation = .33; child-report: α = .72, inter-item correlation = .25) was acceptable.

Alcohol Use

Children reported alcohol use frequency over the past 6 months at the 7th annual assessment (M = 16.15 years old, SD = 1.05). Due to the non-normal distribution of the variable (skewness = 5.92, kurtosis = 43.21), responses were collapsed for analysis into the following categories of drinking in the last 6 months: 0 = did not drink, 1 = drank once, 2 = drank two to five times, and 3 = drank six or more times. This ordinal variable was more normally distributed (skewness = 1.69, kurtosis = 1.41).

Data Analytic Plan

Latent growth curve models (LGCMs) were conducted utilizing Mplus 6.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010) to examine change in personality characteristics over time. Models were estimated using a robust maximum likelihood estimator, and model fit was assessed using the chi-square goodness of fit test, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). For the CFI and TLI, we used cutoff values of .90 or greater indicating acceptable fit while RMSEA values under .08 represented acceptable fit (McDonald & Ho, 2002). Missing data on dependent variables were handled using the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm.

Separate LGCMs were tested for sensation seeking, child-reported impulsivity, and mother-report of child impulsivity. Time was coded so that the intercept reflected the model implied baseline assessment and was used to control for initial differences in personality characteristics. The time score at baseline was estimated with the remaining time points fixed incrementally to reflect the assessment schedule (i.e., 1st assessment = 0, 2nd assessment = 1, 3rd assessment = 2, 4th assessment = 3, 5th assessment = 4.5, 6th assessment = 5.5). Sex (females = 0, males = 1), child age, mother’s education at baseline, and race were examined as predictors of the intercept and slope parameters for all LGCMs.

To examine if changes in personality characteristics predicted later alcohol use, the intercept and slope parameters and study covariates were used to predict alcohol use frequency. The alcohol use variable was specified as ordinal (categorical). We then tested sensation seeking and impulsivity (intercept and slope parameters) as mediators of the association between race and alcohol use. Mplus provides statistical significance tests of indirect (mediated) effects. Bootstrapping was used to estimate the standard errors. We next tested whether the association between personality characteristics (intercept and slope parameters) and alcohol use frequency differed across race. Mplus allows testing of interactions between latent (e.g., slope) and measured (i.e., race) variables. All models were re-run using alcohol use at the 4th annual assessment as a covariate (Mean age = 12.60); a similar pattern of results (not presented) was found.

RESULTS

Descriptive Information

At the baseline assessment (Mean age = 9.52), only 5.8% of the sample reported having ever consumed more than just a sip or a taste of alcohol and only 1% reported drinking alcohol in the last 6 months. Low levels of alcohol involvement (past 6 months) were reported during the 2nd thru 6th annual assessments (e.g., 2nd assessment = 1%; 6th assessment = 16%). By the seventh annual assessment, 26% of the sample reported drinking in the last 6 months. At this assessment, European Americans drank alcohol more frequently than African Americans (χ2(3) = 8.20, p < .05; 8% vs. 2% of European American and African American adolescents, respectively, drank alcohol 6 or more times in the last 6 months; 13% vs. 6% drank 2–5 times; 8% vs. 5% drank once; and 73% vs. 88% did not drink).

Latent Growth Curve Models of Personality Characteristics

The first aim of the current study was to examine change in sensation seeking and impulsivity from childhood into adolescence. Two of the three fit indices, CFI and TLI, indicated good fit for all three LGCMs (see Table 1). The third indicator, RMSEA, was .09 for sensation seeking and child-reported impulsivity (slightly higher than the recommended level of .08).

Table 1.

Model fit indices for base latent growth models.

| Chi-Square | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensation Seeking | 68.19* | 15 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.09 |

| Impulsivity (Child-report) | 65.03* | 15 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.09 |

| Impulsivity (Mother-report) | 40.13* | 15 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.06 |

p < .0001

Sensation Seeking

The LGCM for sensation seeking had a significant mean slope (Ms = 0.03, z = 8.05, p < .001), indicating that mean levels of sensation seeking increased over time. The variances for the intercept and slope of sensation seeking were significant (intercept variance = 0.06, z = 13.60, p < .001 and slope variance = 0.002, z = 7.64, p < .001), indicating significant variation across participants in initial levels of and change in sensation seeking. Additionally, initial level of sensation seeking related negatively to growth in sensation seeking (β = −.27, p < .001), indicating that children with higher initial levels of sensation seeking had a slower increase in sensation seeking over time.

Impulsivity

The LGCM for mother report of impulsivity had a significant negative mean slope (Ms = −0.018, z = −6.39, p < .001), indicating a steady decrease in mother-reported impulsivity over time. Child-reported impulsivity did not have a significant mean slope (Ms = 0.001, z = 0.21, ns). The variances for the intercept and slope of both mother- and child-reported impulsivity were significant (Mother-report: intercept variance = 0.05, z = 13.43, p < .001 and slope variance = 0.001, z = 4.84, p < .001; Child-report: intercept variance = 0.04, z = 12.15, p < .001 and slope variance = 0.001, z = 6.38, p < .001), indicating significant variation among participants in initial levels of and change in impulsivity. Additionally, initial level of mother-reported impulsivity related negatively to growth in impulsivity (β = −0.26, p < .001). Children with higher initial levels of impulsivity had a steeper decrease in impulsivity across this developmental period. Initial levels of child-reported impulsivity did not relate to growth in impulsivity.

Race and Personality Characteristics

The second aim of our study was to examine whether African Americans and European Americans differed in initial levels of and change in disinhibition over time. Sex, age, and mother’s education were included as covariates.

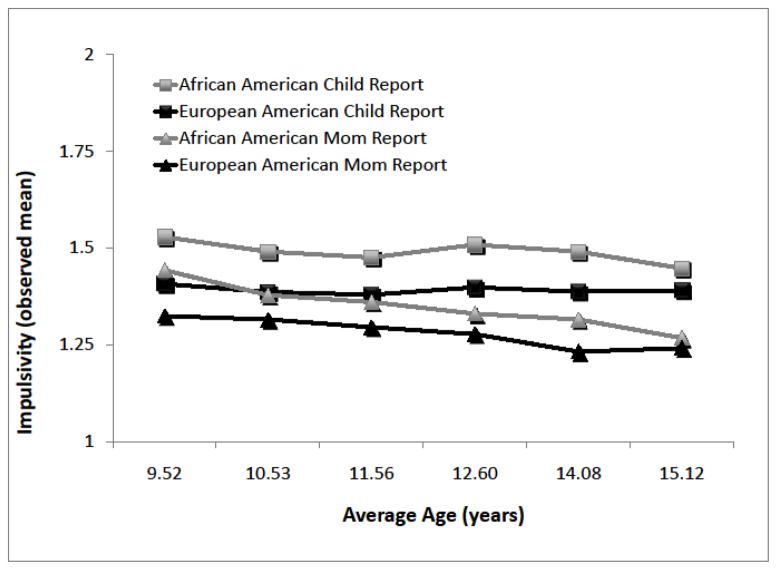

European Americans had higher initial levels of (β = 0.22, p < .001) and greater growth in sensation seeking (β = 0.16, p < .05; see Figure 1) compared to African Americans. Results for impulsivity showed a different pattern: African Americans had higher initial levels of impulsivity than European Americans (mother-reported: β = −0.16, p < .01; child-reported: β = −0.27, p < .001; see Figure 2) but rates of change did not differ by race. LGCMs were re-run adding parental occupational status to more stringently examine if differences in SES could account for these results. Controlling for occupational status did not change the findings.

Figure 1.

Means on Sensation Seeking over Time for African American and European American Children. (Lines represent observed means on child-reported sensation seeking over time, plotted separately by race.)

Figure 2.

Means on Impulsivity over Time for African American and European American Children. (Lines represent observed means of child and mother-report of impulsivity over time, plotted separately by race.)

Personality Characteristics Predicting Drinking Behavior

The third aim was to examine how changes in personality characteristics over time related to later alcohol use. LGCMs, with study covariates, were conducted with the intercept and slope parameters predicting frequency of alcohol use.

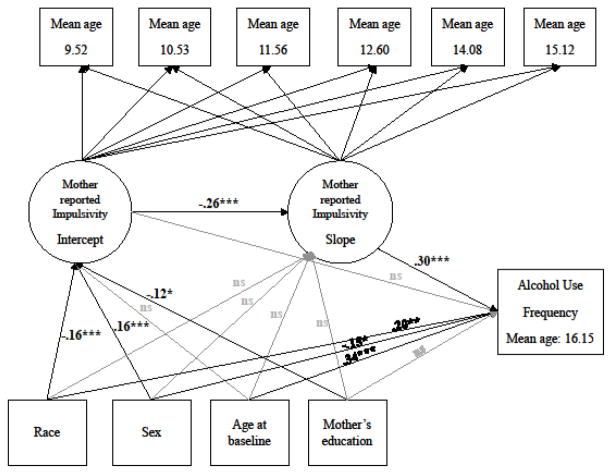

Growth in all three personality measurements related prospectively to more frequent alcohol use at the 7th annual assessment (sensation seeking: β = 0.24, p < .01, see Figure 3; child-reported impulsivity: β = 0.34, p < .001; mother-reported impulsivity: β = 0.30, p < .01, see Figure 4). (Due to the similarity of results for mother- and child-reported impulsivity, we only present a figure for mother-reported impulsivity.) In addition, higher initial levels of sensation seeking related to more frequent alcohol use (β = 0.18, p < .01).

Figure 3.

Latent Growth Curve Model of Sensation Seeking Predicting Later Alcohol Use. (Figure depicts a latent growth curve model of sensation seeking predicting alcohol use frequency 1-year later. Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; Standardized coefficients are presented. Race was coded: African Americans = 0, European Americans = 1. Sex was coded: Females = 0, Males = 1.)

Figure 4.

Latent Growth Curve Model of Mother-reported Impulsivity Predicting Later Alcohol Use. (Figure depicts a latent growth curve model of mother-reported impulsivity predicting alcohol use frequency 1-year later. Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; Standardized coefficients are presented. Race was coded: African Americans = 0, European Americans = 1. Sex was coded: Females = 0, Males = 1.)

Given the differences in personality characteristics and alcohol use across racial groups, intercept and slope parameters for sensation seeking and impulsivity were separately examined as mediators of the association between race and alcohol use. The intercept parameter of sensation seeking significantly mediated this association (β = 0.04, p < .05; 95% CI: 0.004 – 0.078). Higher initial levels of sensation seeking at least partially explain the higher levels of alcohol use for European American compared to African American youth. The indirect effects of race on alcohol use through the intercept parameters of mother- or child-reported impulsivity and through the slope parameters of all three personality characteristics were not significant.

Race was then tested as a moderator of the associations between sensation seeking/impulsivity and alcohol use. Race did not interact with either the intercept or slope parameters for impulsivity (mother- or child-reported) in the prediction of alcohol use. However, a marginally significant (p = .07) interaction between race and the slope parameter of sensation seeking was found. Sharper increases in sensation seeking predicted greater alcohol use frequency for European American adolescents (B = 0.33, p < .001) but not for African American adolescents (B = −0.15, ns).

DISCUSSION

The current study examined two facets of disinhibition, sensation seeking and impulsivity, from childhood into adolescence to understand how these personality constructs change over time, and to determine if these changes explain the lower levels of alcohol use seen in African American compared to European American adolescents (a mediational model). We also tested whether the association between disinhibition and alcohol use differed between European American and African American adolescents (a moderation model).

Although prior studies have examined growth in disinhibited personality characteristics across development (e.g. Roberts et al., 2006), most studies have not examined specific facets of disinhibition. We found differences in the development of sensation seeking and impulsivity from childhood into adolescence: on average sensation seeking increased and impulsivity (mother-report) decreased. Our longitudinal findings are thus in line with previous cross-sectional research showing that impulsivity declines with age and sensation seeking increases in adolescence (Steinberg et al., 2008) as well as research showing increases in sensation seeking during middle school (Crawford et al., 2003).

Social and biological processes that shape development of these personality characteristics may explain these divergent trajectories. Widening opportunities for novel and exciting experiences (e.g., exposure to new activities) in conjunction with temporarily experiencing greater responses in reward-based systems (e.g., Geier, Terwilliger, Teslovich, Velanova, & Luna, 2010) may reinforce sensation seeking tendencies in adolescence. In contrast, social influences from authority figures (parents and teachers) and peers, as well as age-related cognitive development, may improve impulse control with age. Our findings suggest that future research on personality development may benefit from the disaggregation of disinhibition.

Racial Differences in Disinhibited Personality Characteristics and Alcohol Use

Studies examining racial differences in the predictors of alcohol use have been limited and research examining racial differences in the association between disinhibition and alcohol use has been primarily cross-sectional and focused on adults (e.g., McCarthy, Miller, Smith, & Smith, 2001). The present research examined racial differences in both mean level and rates of change in disinhibition in childhood and adolescence. We found that European Americans had higher initial levels of and greater growth in sensation seeking over time. One potential reason for this finding may be that cultural norms favoring sensation seeking behaviors are more prevalent among European American youth. For example, parents and peers of European American youth may provide greater encouragement to engage in thrill seeking behaviors.

Consistent with having higher levels of sensation seeking, European American adolescents also drank alcohol more frequently than African American youth in this sample. Importantly, the higher initial levels of sensation seeking were found to at least partially account for the higher level of alcohol use for European Americans. Additionally, we found tentative support that change in sensation seeking from childhood into adolescence is related to increased alcohol use frequency for European Americans but not for African Americans. This finding is consistent with a meta-analysis (Hittner & Swickert, 2006) that showed sensation seeking was more strongly related to alcohol use in samples with a higher proportion of European Americans. There are several potential reasons why this association is not found (or is less strong) in African American youth. For example, having deviant or substance-using peers has been shown to at least partially explain the association between sensation seeking and alcohol/drug use (Yanovitzky, 2005). However, African American youth are more likely than European American youth to have close friends who disapprove of alcohol use (e.g., Herd, 1997) which could attenuate this association. Future research incorporating culture-specific factors (e.g., discrimination, religiosity, peer use) that may constrain the association between sensation seeking and alcohol use for African Americans is needed (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2007; Michalak, Trocki, & Bond, 2007).

Interestingly, when we examined impulsivity, African Americans had higher mean levels compared to European Americans. While it is beyond the scope of the current study to directly test the underlying mechanism(s) for this difference it is most likely due to a variety of environmental and potentially biological factors. For example, one potential contributor may be socioeconomic status (SES). Lower SES is related to higher levels of impulsivity (e.g., Lynam, Caspi, Moffit, Wikstrom, Loeber, & Novak, 2000) and on average African Americans have lower SES and live in more impoverished neighborhoods compared to European Americans (e.g., Wallace, 1999). However, our findings remained even after controlling for two aspects of SES, parental (mother) education and occupational status, which indicates that SES is not the sole driver of racial differences in impulsivity.

While change in impulsivity was associated with later alcohol use, race was not associated with these changes and did not moderate the association between impulsivity and alcohol use. Previous research indicates higher levels of impulsivity should be related to increased alcohol use. Yet, in the current study, African Americans had higher levels of impulsivity and lower levels of alcohol involvement. It may be that impulsivity relates more strongly to other aspects of alcohol use than frequency of use (e.g., alcohol-related problems). For example, Cyders and colleagues (2009) showed that after controlling for other facets of disinhibition, sensation seeking related to alcohol use frequency, whereas positive urgency (making rash decisions when experiencing positive affect) predicted quantity of alcohol consumed and alcohol-related problems. Recent research has shown that African American adults may experience more alcohol-related consequences compared to European American adults (Mulia, Greenfield, & Zemore, 2009). Examining positive (and negative) urgency may more accurately depict how disinhibited personality characteristics relate to risk for alcohol use and abuse among African Americans. Future studies focusing on older adolescents, where there is more variability in alcohol use and alcohol-related problems, and incorporating additional facets of disinhibition are needed to develop a better understanding of how disinhibited personality characteristics relate to racial differences in alcohol use.

Several limitations of the current study need to be acknowledged. The current study allowed us to examine personality characteristics as longitudinal predictors of later alcohol use across 7 years. However, the low levels of alcohol involvement in the early waves of the study prevented examination of change in personality characteristics in relation to change in drinking behavior. It should also be noted that compared to population based studies (e.g., Monitoring the Future: Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2011), our participants were less likely to use alcohol and drank alcohol less frequently. Additionally, our measurement of sensation seeking consisted of only four items which may not have adequately assessed the construct of “sensation seeking.” Recent research has emphasized the importance of broadening the assessment of disinhibition to include behavioral tasks (MacPherson et al., 2010), which would ensure adequate construct coverage and may help to enhance the exploration of the racial differences begun in the current study.

Lastly, we recognize that “race” is a construct with multiple definitions and meanings (see Helms, Jernigan, & Mascher, 2005) and that this study oversimplifies these complexities. However, we believe that results from this study can be used to advance the literature for future research to examine conceptual constructs that are more meaningful than “race” as a label. Additionally, while the internal consistencies and inter-item correlations of our measures were similar across groups, we were not able to directly examine a full range of psychometric properties as a function of race. Conducting a multi-group confirmatory factor analysis was not feasible in the present study due to sample size restrictions and item response format. Previous research utilizing similar measures (Hoyle et al., 2002; Wills, Windle, & Clearly, 1998) lend further support that these measures tap the same underlying constructs of impulsivity and sensation seeking for both African Americans and European Americans but future research testing the possibility of item bias is needed.

The current study was designed to examine racial differences in disinhibited personality characteristics in association with alcohol use. To our knowledge, our findings are the first to examine racial differences in the development of sensation seeking and impulsivity between childhood and adolescence. Findings from this study reveal different developmental courses for these facets of disinhibition, racial differences in their level and course, and the importance of sensation seeking in explaining differences in alcohol use between European American and African American adolescents.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant AA-12342 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (PI: John E. Donovan). Dr. Pedersen is supported by a T32 Training Grant (AA-07453), also from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

References

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychol Bull. 1987;101:213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Hicks BM, Krueger RF, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG. Continuity and change in psychopathic traits as measured via normal-range personality: A longitudinal-biometric study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:85–95. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Fernandez M, Harwood M, Hou W, Garvan CW, Eyberg SM, Swanson JM. Parent and teacher SNAP-IV ratings of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms: Psychometric properties and normative ratings from a school district sample. Assessment. 2008;15:317–328. doi: 10.1177/1073191107313888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Kaskutas L. Changes in drinking patterns among Whites, Blacks and Hispanics, 1984–1992. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:558–565. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Wood PK, Orcutt HK, Albino A. Personality and the predisposition to engage in risky or problem behaviors during adolescence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:390–410. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AM, Pentz MA, Chou C, Li C, Dwyer JH. Parallel developmental trajectories of sensation seeking and regular substance use in adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17:179–192. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Flory K, Rainer S, Smith GT. The role of personality dispositions to risky behavior in predicting first-year college drinking. Addiction. 2009;104:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA. Beyond Black, White and Hispanic: Race, ethnic origin and drinking patterns in the United States. J Subst Abuse. 1998;10:321–339. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit DJ. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: A review of underlying processes. Addict Biol. 2008;14:22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Smith GT, Olausson P, Mitchell SH, Leeman RF, O’Malley SS, Sher K. Understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addict Biol. 2010;15:217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Molina BSG. Children’s introduction to alcohol use: Sips and tastes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:108–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPauI GJ, Anastopoulos AD, Power TJ, Reid R, Ikeda MJ, McGoey KE. Parent ratings of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms: Factor structure and normative data. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1998;20:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins IJ, King SM, McGue M, Iacono WG. Personality traits and the development of nicotine, alcohol, and illicit drug disorders: Prospective links from adolescence to young adulthood. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:26–39. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SBG, Easting G, Pearson PR. Age norms for impulsiveness, venturesomeness, and empathy in children. Pers Individ Diff. 1984;5:315–321. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Smith GT. Binge eating, problem drinking, and pathological gambling: Linking behavior to shared traits and social learning. Pers Individ Diff. 2008;44:789–800. [Google Scholar]

- Geier C, Terwilliger R, Teslovich T, Velanova K, Luna B. Immaturities in reward processing and its influence on inhibitory control in adolescence. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20(7):1613–1629. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Yeh H, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Cutrona C, Simons RL, Brody GH. Early experience with racial discrimination and conduct disorder as predictors of subsequent drug use: A critical period hypothesis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88S:S27–S37. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE, Jernigan M, Mascher J. The meaning of race in psychology and how to change it. Am Psychol. 2005;60:27–36. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd D. Racial differences in women’s drinking norms and drinking patterns: A national study. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:137–149. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hittner JB, Swickert R. Sensation seeking and alcohol use: A meta-analytic review. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1383–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT, Palmgreen P, Lorch EP, Donohew RL. Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Pers Indiv Differ. 2002;32:401–414. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W, Hicks BM, McGue M, Iacono WG. Most of the girls are alright, but some aren’t: Personality trajectory groups from ages 14 to 24 and some associations with outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;93:266–284. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Demographic subgroup trends for various licit and illicit drugs, 1975–2009 (Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper 73) Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, MI: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2010: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Wikstrom PH, Loeber R, Novak S. The interaction between impulsivity and neighborhood context on offending: The effects of impulsivity are stronger in poorer neighborhoods. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:563–574. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiriski L, Vanyukov M, Tarter R. Detection of youth at high risk for substance use disorders: A longitudinal study. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19:243–252. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Magidson JF, Mitchell SH, Sinha R, Stevens MC, de Wit H. Behavioral and biological indicators of impulsivity in the development of alcohol use, problems, and disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1334–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Is “maturing out” of problematic alcohol involvement related to personality change? J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;188:360–374. doi: 10.1037/a0015125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson L, Magidson JF, Reynolds EK, Kahler CW, Lejuez CW. Changes in sensation seeking and risk-taking propensity predict increases in alcohol use among early adolescents. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1400–1408. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DM, Miller TL, Smith GT, Smith JA. Disinhibition and expectancy in risk for alcohol use: comparing black and white college samples. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:313–321. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP, Ho MH. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:64–82. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak L, Trocki K, Bond J. Religion and alcohol in the U.S. national alcohol survey: How important is religion for abstention and drinking? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:268–280. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan KC, Steinberg L, Cauffman E, Mulvey EP. Trajectories of antisocial behavior and psychosocial maturity from adolescence to young adulthood. Dev Psychol. 2009;45:1654–1668. doi: 10.1037/a0015862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Zemore SE. Disparities in alcohol-related problems among White, Black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:654–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton MR, Colliver JD, Robbins TM, Gfroerer JC. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2008. Underage Alcohol Use: Findings from the 2002–2006 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4333, Analytic Series A-30. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Walton KE, Viechtbauer W. Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:1–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo MF, Stokes GS, Lahey BB, Christ MAG, McBurnett K, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Green SM. A sensation-seeking scale for children: Further refinement and psychometric development. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1993;15:69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Annus AM, Spillane NS, McCarthy DM. On the validity and utility of discriminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment. 2007;14:155–170. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Albert D, Cauffman E, Banich M, Graham S, Woolard J. Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: Evidence for a dual systems model. Dev Psychol. 2008;44:1764–1778. doi: 10.1037/a0012955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed November 19, 2010.];Allegheny County QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau 2007. Available at: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/42/42003.html.

- Wallace JM., Jr Explaining race differences in adolescent and young adult drug use: The role of racialized social systems. Drugs & Society. 1999;14:21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Jr, Muroff JR. Preventing substance abuse among African American children and youth: Race differences in risk factor exposure and vulnerability. J Primary Prev. 2002;22:235–261. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Pers Individ Diff. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Windle M, Cleary SD. Temperament and novelty seeking in adolescent substance use: Convergence of dimensions of temperament with constructs from Cloninger’s theory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74:387–406. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovitzky I. Sensation seeking and adolescent drug use: The mediating role of association with deviant peers and pro-drug discussions. Health Commun. 2005;17:67–89. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1701_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TCB, Stairs AM, Settles RF, Combs JL, Smith GT. The measurement of dispositions to rash action in children. Assessment. 2010;17:116–125. doi: 10.1177/1073191109351372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M, Eysenck SBG, Eysenck HJ. Sensation seeking in Europe and America: Cross-cultural, age and sex comparisons. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1978;65:757–768. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]