Abstract

Background

Findings regarding the relationship between patient treatment preference and treatment outcome are mixed. This is a secondary data analysis investigating the relationship between treatment preference, and symptom outcome and attrition in a large 2-phase depression treatment trial.

Methods

Patients met DSM-IV criteria for chronic forms of depression. Phase I was a 12-week, nonrandomized, open-label trial in which all participants (n=785) received antidepressant medication(s) (ADM). Phase I nonremitters were randomized to Phase II, in which they received 12 weeks of either Cognitive-Behavioral System of Psychotherapy (CBASP) + ADM (n=193), Brief Supportive Psychotherapy (BSP) + ADM (n=187), or ADM only (n=93). Participants indicated their treatment preference (medication only, combined treatment or no preference) at study entry. Symptoms were measured at 2-week intervals with the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D).

Results

A large majority of patients reported a preference for combined treatment. Patients who preferred medication only were more likely to endorse a chemical imbalance explanation for depression, whereas those desiring combined treatment were more likely to attribute their depression to stressful experiences. In Phase I, patients who expressed no treatment preference showed greater rates of HAM-D symptom reduction than those with any preference, and patients with a preference for medication showed higher attrition than those preferring combined treatment. In Phase II, baseline treatment preference was not associated with symptom reduction or attrition.

Conclusions

Treatment preferences may moderate treatment response and attrition in unexpected ways. Research identifying factors associated with differing preferences may enable improved treatment retention and response.

Keywords: treatment outcome, treatment engagement

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a significant public health problem. Beyond the personal suffering experienced by individuals with depression, it is among the leading causes of disability worldwide. [1] Despite improvements in treatment, outcomes often remain suboptimal [2], indicating the need for better understanding of factors that influence treatment engagement and outcome. Patient treatment preference is one such potential moderator.

A recent meta-analysis showed that across diagnoses, matching patients to preferred treatment conditions is associated with decreased dropout and improved symptom outcomes. [3] However, findings regarding the relationship between treatment preference and outcome within MDD and related disorders are mixed. Preference has been shown to predict both therapeutic alliance [4] and attrition [4; 5] in treatment for depression. In addition, several studies have found that among patients with a treatment preference, matching them to the treatment they prefer yields better outcomes than a mismatch.[4; 6–8] By contrast, another study of depressed patients [9] and a study that included patients with pure dysthymic disorder [10] reported no differences in symptom reduction between patients who did and did not receive their treatment of choice.

In addition, most research assessing relationships between treatment preference and outcome has compared groups with preferences for medication versus psychotherapy on treatment outcomes. We are aware of only two prior studies that have assessed the relationships between preference and outcomes in patients preferring combination treatment (medication + psychotherapy) and compared them to those preferring medication only. [7; 8] In those studies, 59% and 40%, respectively, endorsed preferences for combination treatment. Thus, preference for combination treatment, where available, is common. In addition, 20–40% of patients indicate no treatment preference. [4; 7; 9] Although the no preference group also constitutes a significant proportion of participants, we are unaware of any reports that have investigated how those without a treatment preference compare to those with a preference on symptom reduction and treatment attrition. Therefore, the primary aims of this study were 1) To compare those with any treatment preference to those without a preference on symptom reduction and treatment attrition and 2) To compare those with a preference for medication only to those with a preference for combination treatment on symptom reduction and attrition.

In addition, relatively little is known about determinants of patient preference. A greater understanding of factors associated with specific preferences may help to clarify the mixed findings regarding the relationship between preference and outcome; importantly, this knowledge could enhance provider-patient discussions of treatment options. This may be particularly important when a patient's treatment of choice is unavailable (e.g., due to limited resources, insurance coverage limitations, etc.) or carries additional risks (e.g., pharmacotherapy during pregnancy). Prior research has shown patient beliefs about treatment strategies are related to treatment preferences. For example, patients who favorably endorsed psychosocial strategies indicated a preference for psychotherapy and a rejection of antidepressant medication [11] and endorsement of a biomedical explanation of depression was associated with preference for antidepressant medication in a non-clinical sample. [12] Thus, our secondary aim was to examine relationships between patient beliefs about depression etiology and treatment preference. We examined these questions using data collected in the Research Evaluating the Value of Augmenting Medication with Psychotherapy (REVAMP) trial for chronic depression in which treatment preference and patients' beliefs about depression etiology were measured at baseline. [13]

Materials and Methods

Design

The REVAMP trial has been described in detail previously [13] and is briefly summarized here. Institutional Review Boards approved the study at each of six recruiting sites and all participants provided informed consent. The REVAMP study comprised two phases. In an open label Phase I, all patients received algorithm-driven antidepressant medication(s) (ADM). Participants in Phase II were patients who did not remit within 8–12 weeks after taking ADM. Remission was defined by the following three concurrent criteria: a) at least a 60% reduction in score on the 24-item version of the Hamilton-Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) [14], b) a HAM-D score of 7 or less, and c) not meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) for 2 consecutive visits during weeks 6–12. During Phase II, all participants received the next step in the pharmacotherapy algorithm. Participants were randomized in a 2:2:1 ratio to receive Cognitive-Behavioral System of Psychotherapy (CBASP) + ADM, Brief Supportive Psychotherapy (BSP) + ADM, or ADM only. Randomization in Phase II was stratified by site, Phase I response status (non-versus partial responder), and medication response history (prior non-response to three or more prior adequate medication trials, including Phase I, vs. non-response to fewer than three trials). The main results of the parent study showed that, among those who did not respond fully to ADM in Phase I, augmenting medication with either BSP or CBASP did not result in improved treatment outcomes compared to continued ADM algorithm[13]. However, the relationship between preference and outcomes was not previously examined and it is the focus of the current secondary data analysis of REVAMP data.

Participants

Participants were outpatients age 18–75 who scored at least 20 on the 24-item HAM-D at baseline and met DSM-IV-TR criteria [15] for current MDD as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). [16] Qualifying participants all had depressive symptoms that had persisted for 2 or more years, defined as either MDD episode lasting at least two years, recurrent MDD with incomplete interepisode recovery, or current MDD superimposed on dysthymic disorder (i.e., “double depression”). [17]

Exclusion criteria were determined based on SCID-I/P and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis II Disorders (SCID-II) Interviews [18] and included: Current diagnosis of any psychotic disorder or dementia; current primary diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder, anorexia, bulimia or obsessive-compulsive disorder; history of bipolar disorder; antisocial, schizotypal or severe borderline personality disorder. Participants were also excluded for the following reasons: Previous CBASP treatment; previous nonresponse to four or more steps of pharmacotherapy algorithm; unwillingness to terminate other psychiatric treatment during the study; pregnancy; serious unstable medical illness; being unable to read and write in English; and current alcohol or substance-dependence (except nicotine-dependence) that required detoxification.

Treatment Conditions

Kocsis et al. describe treatment conditions in greater detail. [13] All patients received algorithm-driven pharmacotherapy in Phase I and Phase II. The pharmacotherapy regimen was derived from the Texas Medication Algorithm Project and the STAR*D study. [19; 20] Study medications in order of study algorithm were sertraline, escitalopram, buproprion XL, venlafaxine XR, mirtazapine, and lithium. Initial medication selection depended on prior treatment history. [13] Medication dosage changes were based on the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms-Clinician Version (QIDS-C), a clinician administered measure of depressive symptom severity. [21] At phase midpoints, HAM-D response status was used to decide if a change in medication was warranted. A change in medication type or reduction in dose was also instituted if, at any time, reported side effects were deemed unacceptable by the pharmacologist. Every effort was made to manage side effects in order to facilitate a trial of adequate length and dosage for a given medication. Pharmacotherapists followed the Fawcett et al. [22] manual from the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program (NIMH TDCRP) [23], which encourages therapeutic warmth but proscribes all but minimal psychotherapeutic intervention. Clinical management visits took place every two weeks.

CBASP and BSP each followed a treatment manual and consisted of 16–20 sessions. CBASP is a time-limited cognitive-behavioral intervention designed specifically for patients suffering from chronic forms of depression. [24] BSP emphasizes nonspecific (“common”) psychotherapeutic factors [25], particularly highlighting patient strengths and promoting emotional expression, and proscribes specific interpersonal, cognitive, behavioral, and psychodynamic interventions. [26]

Measures

Depression

Trained and certified raters, blind to treatment condition and patient preference, assessed depressive symptoms every two weeks using the 24-item HAM-D. [14] The 24-item version was selected because it contains cognitive items, which may be particularly important in assessment of chronic depression. [28; 29] History of MDD episodes (occurrence, length, and severity) was assessed with the SCID-I/P. [16]

Treatment preference

Following prior research [7], patient treatment preference was assessed at baseline by a single face-valid written question asking, “Do you have a preference for which type of treatment you receive in this study?” with the following response options: medication only, combined medication and psychotherapy or no preference.

Beliefs about depression

Patients indicated their beliefs about depression etiology by rating their extent of agreement with each of five statements. Items were developed to correspond to a biological explanation for depression (e.g., “imbalance of certain substances in my brain”) versus psychosocial explanations (e.g., “stressful or painful things,” “pessimistic attitudes,” “an illness which affects me emotionally”) versus unclear attribution (“comes out of the blue”). Each item was rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1=Very strongly disagree; 6=Very strongly agree).

Data Analysis

Descriptive characteristics of participants were compared by 1) having a treatment preference vs. no preference and 2) preferring medication only vs. combined medication plus psychotherapy. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square analyses and continuous variables were compared using t-tests. Bonferroni corrected p-values were used to control for multiple comparisons.

In order to assess the magnitude of relationship among beliefs about etiology of depression, bivariate Pearson correlations of the degree of endorsement were computed for all belief item pairs. A MANOVA procedure with post hoc Bonferroni tests was used to compare baseline treatment preference groups (medication vs. medication plus psychotherapy vs. no preference) on mean level of patient belief in each of five possible causes of depression. The test of the association between treatment preference and outcome was assessed using linear mixed effects models. This approach was selected as the primary analysis because it is preferable for assessing repeated measures questions that include missing data (e.g., due to attrition). [30] For each phase, separate models were tested comparing patients with any treatment preference vs. no preference and, among those with a preference, comparing patients preferring combined treatment to those preferring medication only. For each model, preference type and the slope of preference type by time point were entered as fixed effects with intercept and time entered as random effects. Random intercepts were allowed because randomization was not stratified based on treatment preference. HAM-D scores were entered as the repeated measures outcome variable. Analyses were conducted using the MIXED procedure in IBM/SPSS 19.0. In order to assess the relationship between preference and attrition, chi-square tests compared the proportions of treatment dropouts in each phase by baseline treatment preference.

For significant findings, effect sizes are reported. Effect sizes for t-tests are reported as Cohen's d and effect sizes for chi-square analyses are reported as odds ratios using the following formula: [(The probability of event in Group 1 / 1-probability of event in Group 1) / (The probability of event in Group 2 / 1 – probability of event in Group 2)].

Results

Participant Characteristics

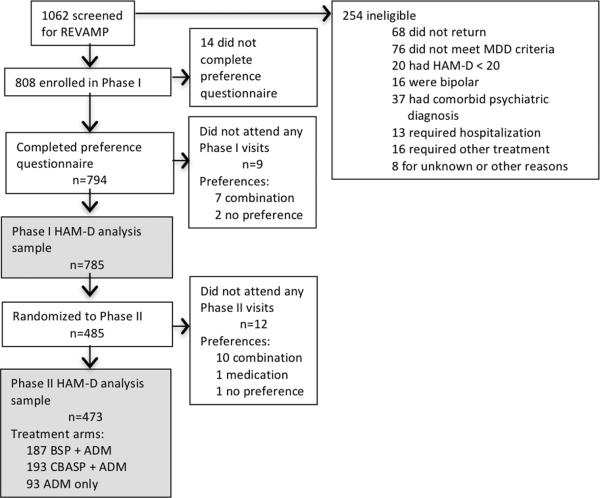

The Phase I sample included 785 patients who completed the preference questionnaire at baseline and attended at least one post randomization session (97.2% of the consented sample). Among these patients, 203 (25.9%) reported no treatment preference. Among the 582 participants who expressed preference, the majority preferred a combination of medication and psychotherapy (n=532, 91.4%) and the rest preferred medication only (n=50, 8.6%).

Descriptive information for the Phase I sample appears in Table 1. In Phase I, those with a treatment preference had experienced a greater number of years of MDD compared to those with no preference, t(380) = 2.72, p = .007, Cohen's d = .22. Those with a treatment preference also had a higher proportion of patients who reported prior ADM use compared to those with no preference, χ2(2) = 19.6, p < .001, odds ratio = 2.04. Those with a preference for medication only did not differ from those with a preference for combination in terms of proportion reporting prior ADM experience, χ2(2) = 1.34, p = .51.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the sample.

| Characteristic | Medication only | Combination | Any preference | No preference | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Categorical Characteristics | |||||

| Race, No. (%) | |||||

| White | 42 (84.0) | 453 (85.2) | 495 (85.1) | 171 (84.2) | 666 (84.8) |

| Black | 4 (8.0) | 38 (7.1) | 42 (7.2) | 18 (8.9) | 60 (7.6) |

| Asian | 2 (4.0) | 14 (2.6) | 16 (2.7) | 9 (4.4) | 25 (3.2) |

| American Indian or Alaskan | 0 | 3 (0.5) | 3 (.5) | 2 (1.0) | 5 (0.6) |

| Native | |||||

| Indicated more than 1 | 2 (4.0) | 24 (4.5) | 26 (4.5) | 3 (1.5) | 29 (3.7) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity, No. (%) | |||||

| Yes | 1 (2.0) | 48 (9.2) | 49 (8.6) | 8 (4.0) | 57 (7.4) |

| No | 49 (98.0) | 475 (90.8) | 524 (91.4) | 194 (96.0) | 718 (92.6) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||||

| Male | 27 (54.0) | 224 (42.1) | 251 (43.1) | 94 (46.3) | 345 (43.9) |

| Female | 23 (46.0) | 308 (57.9) | 331 (56.9) | 109 (53.7) | 440 (56.1) |

| Employment status, No. (%) | |||||

| Employed | 38 (76.0) | 322 (61.0) | 360 (62.3) | 126 (62.7) | 486 (62.4) |

| Unemployed | 8 (16.0) | 171 (32.4) | 179 (31.0) | 65 (32.3) | 244 (31.3) |

| Retired | 4 (8.0) | 35 (6.6) | 39 (6.7) | 10 (5.0) | 49 (6.3) |

| Education, No. (%) | |||||

| <High school | 0 | 25 (4.7) | 25 (4.3) | 12 (6.0) | 37 (4.7) |

| High school graduate | 11 (22.0) | 89 (16.8) | 100 (17.3) | 50 (24.9) | 150 (19.2) |

| > High school | 39 (78.0) | 415 (78.4) | 454 (78.4) | 139 (69.2) | 593 (76.0) |

| Marital status, No. (%) | |||||

| Married or cohabitating | 16 (32.7) | 205 (38.6) | 221 (38.2) | 91 (45.0) | 312 (40.0) |

| Never | 22 (44.9) | 174 (32.9) | 196 (33.9) | 63 (31.2) | 259 (33.2) |

| Divorced or separated | 10 (20.4) | 138 (26.1) | 148 (25.6) | 43 (21.3) | 191 (24.85) |

| Widowed | 1 (2.0) | 12 (2.3) | 13 (2.2) | 5 (2.5) | 18 (2.3) |

|

| |||||

| Chronic MDD type, No. (%) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Recurrent MDD with incomplete interepisode recovery | 7 (14.3) | 82 (15.7) | 89 (15.6) | 35 (17.8) | 125 (16.1) |

|

| |||||

| MDD + Dysthymia | 30 (61.2) | 274 (52.5) | 304 (53.2) | 96 (48.7) | 405 (52.1) |

|

| |||||

| MDD episode longer than 2 years | 12 (24.5) | 166 (31.8) | 178 (31.2) | 66 (33.5) | 248 (31.9) |

|

| |||||

| Prior ADM experience, No. (%) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 26 (52.0) | 353 (66.4) | 379 (65.1) | 97 (47.8) | 476 (60.6) |

|

| |||||

| No | 24 (48.0) | 179 (33.6) | 203 (34.9) | 106 (52.2) | 309 (39.4) |

|

| |||||

| Patient reported best response to prior ADM, No. % | |||||

|

| |||||

| No prior ADM experience | 24 (48.0) | 179 (33.6) | 203 (34.9) | 106 (52.2) | 309 (39.4) |

|

| |||||

| No response | 12 (24.0) | 136 (25.6) | 148 (25.4) | 36 (17.7) | 184 (23.4) |

|

| |||||

| Marginal response | 6 (12.0) | 124 (23.3) | 130 (22.3) | 35 (17.2) | 165 (21.0) |

|

| |||||

| Marked response | 2 (4.0) | 28 (5.3) | 30 (5.2) | 8 (3.9) | 38 (4.8) |

|

| |||||

| Remission response | 4 (8.0) | 3 (0.6) | 7 (1.3) | 3 (1.5) | 10 (1.3) |

|

| |||||

| No information on response | 2 (4.0) | 62 (11.6) | 64 (11.0) | 15 (7.4) | 79 (10.1) |

|

| |||||

|

Continuous Characteristics

| |||||

| Age, y | |||||

| Mean, (SD) | 42.7 (13.4) | 44.9 (11.9) | 44.7 (12.1) | 42.4 (13.1) | 44.1 (12.4) |

| Age at initial onset of MDD, y | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 26.6 (13.9) | 26.4 (13.1) | 26.4 (13.2) | 26.9 (13.6) | 26.5 (13.3) |

| Length of index episode of MDD, mo | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 89.3 (107.0) | 90.8 (110.2) | 90.7 (109.8) | 85.2 (97.3) | 89.3 (106.7) |

| Duration of MDD, y | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.1 (12.9) | 18.3 (13.3) | 18.2 (13.3) | 15.4 (12.0) | 17.4 (13.0) |

| No. of episodes of MDD | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.6 (3.1) | 2.5 (3.2) | 2.5 (3.2) | 2.2 (1.7) | 2.4 (2.9) |

| Baseline HRSD-24 | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 28.6 (6.6) | 27.4 (5.8) | 27.5 (5.9) | 28.3 (5.6) | 27.7 (5.8) |

| Baseline HRSD-17 | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 21.2 (5.1) | 20.1 (4.2) | 20.2 (4.3) | 20.9 (4.0) | 20.4 (4.2) |

Among those who reported prior use of ADM, those with and without a preference did not differ in their perceptions of best response to prior ADM, χ2(4) = .82, p = .93. However, those with a preference for medication only differed from those with a preference for combination in their perceptions of best response to prior ADM, χ2(4) = 30.48, p < .001. This finding appeared to be driven mainly by those with a preference for medication only having a higher proportion of patients reporting remission with prior ADM, odds ratio = 21.21, as well as a lower proportion of patients reporting marginal response to prior ADM, compared to the combination preference group, odds ratio = .55. In Phase I, preference groups did not differ on other descriptive characteristics listed in Table 1.

The Phase II sample included the 473 patients who completed the baseline preference questionnaire, did not remit during Phase I and were randomized to Phase II, and attended at least one post randomization Phase II session. Among them, 345 (72.9%) indicated a baseline treatment preference for combination, 105 (22.2%) had no preference, and 23 (4.9%) preferred medication only.

Associations Between Beliefs About Depression and Treatment Preference

Bivariate Pearson intercorrelations of the five belief statements were small or nonsignificant (all r's < +/− .22), suggesting that the five statements tapped relatively independent etiology beliefs. Belief items were not completed by 5% of the Phase I sample (4% of the medication only preference group; 6% of the combined preference group and 4% of the no preference group). A MANOVA used to compare patients' beliefs in the causes for depression (five items) by preference group (no treatment preference, medication preference, combined treatment preference) revealed a significant effect for preference group, F(10,1472) = 3.71, p < .001. Post hoc comparisons using a Bonferroni correction revealed that patients with a baseline preference for medication were significantly more likely to endorse the belief that their problems were due to a chemical imbalance than patients with a baseline preference for combination, mean difference = .48, p =.02, Cohen's d = .41 or with no baseline preference, mean difference = .59, p = .00, Cohen's d = .52. By contrast, patients preferring combination treatment were significantly more likely to attribute their problems to stressful life events than those preferring medication only, mean difference = .69, p < .001, Cohen's d = .59 or with no baseline treatment preference, mean difference = .37, p < .001, Cohen's d = .36. Table 2 displays descriptive statistics for endorsement of the five beliefs by preference group.

Table 2.

Endorsement of five possible causes of depression.

| Baseline Treatment Preference M(SD) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication only (n=48)a | Combination medication + psychotherapy (n=500)a | No preference (n=194)a | Overall M(SD) (n=742) | |

| An imbalance of certain substances in my brain | 4.62 (1.16)* | 4.14 (1.17) | 4.02 (1.14) | 4.15 (1.17) |

| Pessimistic attitudes about many things | 3.67 (1.23) | 3.83 (1.25) | 3.71 (1.26) | 3.83 (1.25) |

| Stressful or painful things that have happened | 3.86 (1.28) | 4.58 (1.16)* | 4.15 (1.23) | 4.40 (1.20) |

| Comes “out of the blue” | 2.60 (1.36) | 2.56 (1.22) | 2.68 (1.21) | 2.60 (1.22) |

| An illness which affects me emotionally instead of physically | 3.69 (1.59) | 3.70 (1.24) | 3.71 (1.23) | 3.71 (1.26) |

Note:

Beliefs measure was not completed by all participants. Out of 6-point Likert scale with 1=very strongly disagree, 2=strongly disagree, 3=disagree, 4=agree, 5=strongly agree, 6=very strongly agree.

p<.01

Did Baseline Treatment Preference Predict Treatment Response?

Phase I

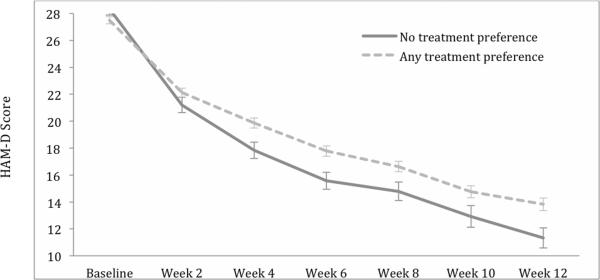

Results of linear mixed effects models (LMM) appear in Table 3. Phase I HAM-D scores decreased significantly over time for patients regardless of baseline treatment preference. However, depressive symptoms of patients with no baseline treatment preference decreased more quickly than those reporting a preference, F(1, 616) = 8.01, p < .005. Based on LMM estimates, over the course of Phase 1, those with no preference decreased an average of 13.56 points (12 weeks × 1.13) compared to 11.16 points (12 weeks × .93) in those with a preference. In other words, symptom decrease in the preference group was only 82% of that in the no preference group. Figure 2 shows mean HAM-D scores for the no preference and any preference groups across Phase 1. Phase I HAM-D scores also decreased significantly across time for those with a preference for combination and medication only. However the time by preference group interaction was not significant, F(1, 457) = 1.28, p = .26, suggesting that the rate of symptom reduction did not differ between the two groups declaring a preference.

Table 3.

Linear mixed effects estimates for HAM-D scores among patients with and without a baseline treatment preference.

| Estimate | SE | df | t value | P value | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Phase I

| |||||||

| Intercepta | |||||||

| No treatment preference | 24.39 | .46 | 757 | 53.1 | .001 | 23.49 | 25.29 |

| Treatment preference | 25.00 | .27 | 747 | 92.81 | .001 | 24.47 | 25.53 |

| Combination preference | 24.95 | .28 | 563 | 88.70 | .001 | 24.40 | 25.51 |

| Medication only preference | 25.57 | .93 | 579 | 27.62 | .001 | 23.76 | 27.39 |

| Slope | |||||||

| No treatment preference × week | −1.13 | .06 | 615 | −18.70 | .001 | −1.25 | −1.01 |

| Treatment preference × week | −.93 | .04 | 615 | −26.10 | .001 | −1.00 | −.86 |

| Combination preference × week | −.92 | .04 | 461 | −25.46 | .001 | −.99 | −.85 |

| Medication only preference × week | −1.07 | .12 | 457 | −8.56 | .001 | −1.31 | −.82 |

|

| |||||||

|

Phase II

| |||||||

| Interceptb | |||||||

| No treatment preference | 17.86 | .79 | 456 | 22.52 | .001 | 16.30 | 19.42 |

| Treatment preference | 18.64 | .42 | 458 | 43.92 | .001 | 17.81 | 19.48 |

| Combination preference | 18.67 | .44 | 357 | 42.34 | .001 | 17.81 | 19.54 |

| Medication only preference | 18.21 | 1.72 | 356 | 10.58 | .001 | 14.83 | 21.59 |

| Slope | |||||||

| No treatment preference × week | −.47 | .07 | 425 | −6.95 | .001 | −.60 | −.33 |

| Treatment preference × week | −.50 | .04 | 422 | −14.07 | .001 | −.57 | −.43 |

| Combination preference × week | −.51 | .04 | 326 | −14.12 | .001 | −.57 | −.44 |

| Medication only preference × week | −.35 | .15 | 314 | −2.42 | .016 | −.64 | −.07 |

Indicates estimates for average baseline HAM-D score by preference type.

Indicates estimates for average HAM-D score at entrance to Phase II by preference type.

Figure 2.

Mean HAM-D scores across Phase I for patients with and without a treatment preference.

Phase II

Patients with no baseline treatment preference did not differ in HAM-D scores at entry to Phase II from those with a treatment preference, F(1, 457) = .77, p = .38. Scores decreased significantly from the beginning to the endpoint of Phase II for both groups, with no significant difference in rate of decrease between the groups, F(1, 424) = .23, p = .64. HAM-D scores at entry to Phase II did not significantly differ between patients preferring combination versus medication only treatment, F(1, 356) = .07, p = .79. Both groups demonstrated significant decreases in HAM-D scores across time but their rates of decrease did not significantly differ, F(1, 314) = 1.07, p = .30. Cell sizes for Phase II treatment arm by baseline treatment preference were 11 or less for those with a medication only preference, which precluded analyses of treatment preference by treatment arm interactions on treatment outcome.

Did Baseline Treatment Preference Predict Attrition?

The overall phase I treatment dropout rate was 20.9%; drop out rates by preference group were 38.0% among patients preferring medication only, 19.7% among those preferring combined treatment, and 19.7% among those with no preference. Chi-square tests indicated that those with no treatment preference did not differ from those with any treatment preference in attrition, χ2(1) = .23, p = .63, odds ratio = 1.10. However, patients who preferred medication were significantly more likely to drop out of Phase I than those preferring combination at baseline, χ2(1) = 9.09, p = .003, odds ratio = 2.50. In order to explore whether lack of response to preferred treatment might explain the counter intuitive finding that those who preferred medication only and were receiving medication only were more likely to drop out, we examined early HAM-D symptom response. Percent symptom change from baseline to Weeks 2 and 4 was compared among patients who did and did not complete Phase I. Weeks 2 and 4 were selected because nearly two-thirds of Phase I dropouts among patients preferring medication occurred prior to Week 6, and thus Weeks 2 and 4 provided the bulk of available data on subsequent dropouts. Among the medication only preference group at Week 2, no significant differences in percent symptom change emerged between patients who did and did not subsequently drop out, t(35) = −1.52, p = .14, M(SD)completers = 23.65(25.91), M(SD)noncompleters = 9.84(27.17). However, Week 4 comparisons using a Bonferroni corrected p-value of p < .025 revealed a trend: patients who dropped out tended to have less HAM-D symptom reduction at Week 4 than Phase I completers, t(32) = −2.08, p = .05, M(SD)completers = 40.51(28.73), M(SD)noncompleters = 17.95 (28.85), Cohen's d = .78. By contrast, among those with a combination preference, HAM-D symptom change did not differ by completion status at Week 2, t(412) = −.15, p = .88, M(SD)completers = 19.98(23.59), M(SD)noncompleters = 19.52(26.12), or Week 4, t(386) = .16, p = .88, M(SD)completers = 27.15(27.29), M(SD)noncompleters = 27.86(35.19).

To further explore determinants of attrition by preference, we tallied reasons for Phase I dropout by preference group (Table 4). This revealed that a large proportion of patients failed to return to clinic/lost contact. Cell sizes were very small for other attrition reasons, thus precluding statistical tests of differential reasons for dropout by preference group.

Table 4.

Reasons for phase I attrition among dropouts.

| Baseline Treatment Preference, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Medication only dropouts (19) | Combination dropouts (n=105) | No preference dropouts (n=40) | |

| Refused treatment due to lack of efficacy | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0) |

| Unacceptable side effects | 2 (10.5) | 21 (20.0) | 6 (15.0) |

| Developed general medical condition requiring protocol to be stopped | 1 (5.3) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (10) |

| Developed symptoms requiring non-protocol treatment (e.g., psychosis, mania, etc.) | 1 (5.3) | 9 (8.6) | 2 (10) |

| Moved from the area | 2 (10.5) | 4 (3.8) | 1 (5.0) |

| Found research too burdensome | 4 (21.1) | 16 (15.2) | 8 (20.0) |

| Patient withdrew from study with no reason given | 0 (0) | 3 (2.86) | 1 (5.0) |

| Failed to return to clinic/lost contact | 9 (47.4) | 50 (47.6) | 20 (50.0) |

In Phase II, the overall treatment dropout rate was 11.6%; the dropout rate was 21.7% among patients with baseline treatment preference for medication only, 10.7% among those preferring combination, and 12.4% among no preference patients. Chi-square tests indicated no significant difference in attrition between patients preferring medication versus combination treatment, χ2(1) = 2.59, p = .11, odds ratio = 1.14, or between no treatment preference and preference for any treatment, χ2(1) = .07, p = .79, odds ratio = 1.09.

Discussion

The current study augments existing research on the relationship between depression treatment preference and outcome [4–9] by showing that simply expressing a preference for either of two types of treatments predicted slower response to antidepressant medication compared to indicating no treatment preference. Visual inspection of HAM-D scores in Figure 2 suggests that the more rapid symptom reduction among those with no preference took place primarily prior to Week 4, after which the rate of symptom reduction was relatively similar between the preference and no preference groups.

One explanation for slower response to Phase I ADM among those who expressed preference may be differences in ADM treatment history prior to study entry. Those with a treatment preference were more likely to report prior ADM treatment than those with no preference. Prior studies have shown similar findings; For example, prior ADM experience was one of the best predictors of preference for ADM among depressed older adults. [31] We also found that those with no preference had experienced fewer years of MDD compared to those with a preference. The difference was small but suggests that the lower rate of prior ADM use may be accounted for by a shorter MDD duration. Nonetheless, the average duration of MDD among those with no preference was far from negligible (over 15 years) and approximately half of those with no preference reported no prior ADM use. We have previously reported that many chronically depressed patients go years either without any or with inadequate ADM treatment. [33] The current findings suggest that the subset of people who have not received any ADM treatment, even when MDD has been longstanding, may be more likely to express no treatment preference and to show better treatment response to ADM.

Another possible explanation for those with no treatment preference showing more rapid symptom reduction is that the group expressing a preference was largely comprised of those who preferred combination treatment. However, combination treatment was not provided in Phase I. The mismatch between preference and the treatment provided might have reduced patient's expectations of benefit from the treatment provided, in turn, yielding a decreased placebo response. On the other hand, a comparison of patients preferring medication only and those preferring combination showed no difference in rates of symptom reduction, suggesting that preference for combination specifically does not account for the preference versus no preference finding.

Preference groups also differed in their beliefs about depression. Consistent with prior research showing that beliefs about depression are related to treatment preferences. [11; 12] the current research extended these findings, showing that patients who preferred medication only more strongly endorsed a chemical imbalance explanation for depression, whereas those with a preference for combination treatment more strongly endorsed a life stress explanation. In addition, patients without a preference did not strongly endorse any of five proposed etiologies, suggesting that they had no strong causal opinion. Thus, an alternative explanation for the more rapid treatment response of the no preference group in Phase I is that lack of conviction in any particular depressive etiology yielded an openness that facilitated greater treatment response.

Interestingly, in Phase I where all participants received pharmacotherapy, patients with baseline preference for medication only had a higher rate of attrition than those who preferred combination. Moreover, most who dropped out of the current study did so before week 6. Although only a trend level finding, we found that among those with a medication only preference, dropouts had lower percent symptom reduction prior to dropping out than did Phase I completers. However, this difference did not emerge among those with a preference for combined treatment. Thus, one explanation is that the subgroup preferring medication only found the lack of response to their preferred treatment particularly discouraging. Alternatively, because this study offered psychotherapy only in combination with medication, expressing a preference for medication only (rather than combined treatment) may actually have indicated an aversion to psychotherapy. In that case, patients preferring medication only may have been more likely to drop out as they approached Phase II, in which two of three treatment arms included psychotherapy. Future research might further assess how poor initial response to a preferred treatment affects treatment motivation and retention.

Fewer than 10% of participants in the current study preferred medication only, which is noteworthy in the context of the study design because it was communicated during the consent process that all participants would initially receive medication only. The percentage preferring medication only in the current study is lower than rates reported in prior studies comparing medication only preferences to preference for psychotherapy and/or no preference. [4; 6; 9] However, it is more consistent with prior studies that also included a combination treatment preference option.[7; 8] This may suggest that among patients who prefer that medication be part of their treatment, many prefer a combined approach when given the choice between medication only and combination treatment. As an alternative explanation for the low rates of medication only preference, both the current study and one of two prior studies finding a similarly low rate [7] included only patients experiencing chronic forms of depression. Thus, the low preference for medication only may be specific to those experiencing chronic forms of depression.

A primary limitation of the study was that, despite the large overall sample size, small cell sizes precluded analysis of preference by treatment arm interactions for Phase II. Thus, findings that treatment preference was not related to outcomes in Phase II require cautious interpretation. Further, because combination treatment was the only route to receiving psychotherapy in the REVAMP trial, and because by definition, patients randomized in Phase II had not responded to a medication trial in Phase I, the extent to which Phase II findings regarding preference and attrition generalize to other settings is unclear. The sample was also relatively highly educated and ethnically homogenous. Thus, generalizability of current findings to people of differing educational levels and ethnic backgrounds may also be limited. In addition, data about psychotherapy experiences prior to study entry were not collected, which precluded a complete analysis of treatment history as it related to treatment preference in this sample. Prior studies have found psychotherapy history to be related to preference for particular treatments. [31; 34] In future studies investigating patient preferences and outcomes, it will be important to assess both the previous medication and psychotherapy experiences of patients.

Conclusion

This study suggests that additional research into patient beliefs about depression and other possible characteristics associated with treatment preference may yield insights into optimizing depression treatment retention and symptom response. Studies that include measures of beliefs about depression and treatment preference, thoroughly assess treatment history, and involve different treatment options, would enhance understanding of how patients adopt treatment preferences. In addition, examination of beliefs about etiology and treatment preference in culturally and ethnically diverse samples is needed. For example, examining how preferences and beliefs interact with cultural background may be useful. [12] As it becomes clearer how preferences are formed, studies assessing the degree to which preferences are modifiable may prove useful for situations in which the initially preferred treatment is not available or recommended.

Figure 1.

Participant flowchart.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the many study personnel who assisted in study execution and data collection as well as the patients who participated in the study.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by NIMH grants to: Cornell University (UO1 MH62475; James H. Kocsis); University of Pittsburgh (UO1 MH61587; Michael E. Thase); Stony Brook University (UO1 MH62546; Daniel N. Klein); University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UO1 MH61562; Madhukar Trivedi); Emory University (UO1 MH63481; Philip Ninan and Barbara O. Rothbaum); University of Arizona (U01 MH62465; Alan J. Gelenberg); Brown University (UO1 MH61590; Martin B. Keller); Stanford University (UO1 MH61504 and 5T32MH019938-18; Alan F. Schatzberg); and Virginia Commonwealth University (U01 MH62491; James P. McCullough, Jr.). All medications for this study were donated by Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Organon Pharmaceuticals Inc, Pfizer Inc, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Previous presentations: This study was presented in part at the meeting of the North American Society for Psychotherapy Research on 9/23/11 in Banff, Alberta, CA.

References

- 1.World Health Organiziation . Depression Management Fact Sheet. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swift JK, Callahan JL, Vollmer BM. Preferences. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(2):155–65. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwan BM, Dimidjian S, Rizvi SL. Treatment preference, engagement, and clinical improvement in pharmacotherapy versus psychotherapy for depression. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(8):799–804. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Schaik DJ, Klijn AF, van Hout HP, et al. Patients' preferences in the treatment of depressive disorder in primary care. General hospital psychiatry. 2004;26(3):184–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chilvers C, Dewey M, Fielding K, et al. Antidepressant drugs and generic counselling for treatment of major depression in primary care: randomised trial with patient preference arms. BMJ. 2001;322(7289):772–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7289.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kocsis JH, Leon AC, Markowitz JC, et al. Patient preference as a moderator of outcome for chronic forms of major depressive disorder treated with nefazodone, cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy, or their combination. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(3):354–61. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin P, Campbell DG, Chaney EF, et al. The influence of patient preference on depression treatment in primary care. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30(2):164–73. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leykin Y, Derubeis RJ, Gallop R, et al. The relation of patients' treatment preferences to outcome in a randomized clinical trial. Behav Ther. 2007;38(3):209–17. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markowitz JC, Kocsis JH, Bleiberg KL, et al. A comparative trial of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for “pure” dysthymic patients. Journal of affective disorders. 2005;89(1–3):167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manber R, Chambers AS, Hitt SK, et al. Patients' perception of their depressive illness. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2003;37(4):335–343. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez YGE, Franks P, Jerant A, et al. Depression treatment preferences of Hispanic individuals: exploring the influence of ethnicity, language, and explanatory models. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM. 2011;24(1):39–50. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.01.100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kocsis JH, Gelenberg AJ, Rothbaum BO, et al. Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy and brief supportive psychotherapy for augmentation of antidepressant nonresponse in chronic depression: the REVAMP Trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(11):1178–88. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6(4):278–96. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-4th Edition Text Revision. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, version 2.0) Bio-metrics Research Dept., New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keller MB, Shapiro RW. “Double depression”: superimposition of acute depressive episodes on chronic depressive disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(4):438–42. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.4.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; Washington, D.C.: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crismon ML, Trivedi M, Pigott TA, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(3):142–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. Background and rationale for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26(2):457–94. x. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573–83. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fawcett J, Epstein P, Fiester SJ, et al. Clinical management--imipramine/placebo administration manual. NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1987;23(2):309–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. General effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):971–82. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110013002. discussion 983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCullough JP. Treatment for Chronic Depression: Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frank JD. Eleventh Emil A. Gutheil memorial conference. Therapeutic factors in psychotherapy. Am J Psychother. 1971;25(3):350–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1971.25.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markowitz JC, Manber R, Rosen P. Therapists' responses to training in brief supportive psychotherapy. Am J Psychother. 2008;62(1):67–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2008.62.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCullough JP, Jr, Klein DN, Keller MB, et al. Comparison of DSM-III-R chronic major depression and major depression superimposed on dysthymia (double depression): validity of the distinction. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109(3):419–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein DN, Kocsis JH, McCullough JP, et al. Symptomatology in dysthymic and major depressive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19(1):41–53. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ley P, Helbig-Lang S, Czilwik S, et al. Phenomenological differences between acute and chronic forms of major depression in inpatients. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65(5):330–7. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2011.552121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH. Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(3):310–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gum AM, Arean PA, Hunkeler E, et al. Depression treatment preferences in older primary care patients. Gerontologist. 2006;46(1):14–22. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(8):527–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kocsis JH, Gelenberg AJ, Rothbaum B, et al. Chronic forms of major depression are still undertreated in the 21st century: systematic assessment of 801 patients presenting for treatment. J Affect Disord. 2008;110(1–2):55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khalsa SR, McCarthy KS, Sharpless BA, et al. Beliefs about the causes of depression and treatment preferences. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(6):539–49. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]