Abstract

In 2007, the International Knockout Mouse Consortium (IKMC) made the ambitious promise to generate mutations in virtually every protein-coding gene of the mouse genome in a concerted worldwide action. Now, 5 years later, the IKMC members have developed high-throughput gene trapping and, in particular, gene-targeting pipelines and generated more than 17,400 mutant murine embryonic stem (ES) cell clones and more than 1,700 mutant mouse strains, most of them conditional. A common IKMC web portal (www.knockoutmouse.org) has been established, allowing easy access to this unparalleled biological resource. The IKMC materials considerably enhance functional gene annotation of the mammalian genome and will have a major impact on future biomedical research.

Introduction

Annotation of the human and mouse genomes has identified more than 20,000 protein-coding genes and more than 3,000 noncoding RNA genes. Together, these genes orchestrate the development and function of the organism from fertilization through embryogenesis to adult life. Despite the dramatic increase in knowledge of variation in human genomes of healthy and diseased individuals, the normal functions of common forms of most genes are still unknown and consequently the disease significance of rare variants remains obscure as well.

To determine gene function, mutation of those genes is required in model organisms. The mouse has long been regarded as ideal for this purpose. Conservation of most aspects of mammalian development, anatomy, metabolism, and physiology between humans and mice is underscored by strong one-to-one orthologous relationships between genes of the two species. Conservation of gene function is strongly supported by similar phenotypic consequences of complete or partial loss-of-function mutations in orthologous genes in both species and by functional replaceability of mouse genes by their human counterparts (Wallace et al. 2007).

To provide a platform for addressing vertebrate gene function on a large scale, the research community came together to establish a genome-wide genetic resource of mouse mutants (Austin et al. 2004; Auwerx et al. 2004). The consensus was that the future currency of this biological resource should be based on ES cells, which can be readily transferred between laboratories and across international boundaries. It was also felt that the most desirable alleles would be those generated by gene targeting. Bespoke designs for each gene would accommodate each gene’s unique structural attributes and take account of adjacent genomic features. Uncertainty in the scalability of gene-targeting technology coupled with the availability of several gene-trap libraries and the speed with which additional mutant alleles could be generated by gene-trapping methods resulted in agreement that the resource should be generated initially by using both gene-targeting and gene-trapping technologies.

Thus, the vision emerged of a core public archive of ES cell clones on a single uniform genetic background, each clone carrying an engineered mutation in a different gene. To extract biological insights from this resource, individual ES cell clones would be converted into mice by individual investigators and organized programs.

To deliver the ES cell resource toward this vision of functional annotation, four international programs in Europe and North America were established with the goal of achieving saturation mutagenesis of the mouse genome: EUCOMM, KOMP, NorCOMM, and TIGM (see Table 3). These programs were the founding members of the International Knockout Mouse Consortium (IKMC), fostering groups to work together in a highly coordinated, standardized manner, to share technologies, to maximize output, and to largely avoid duplication of effort (Collins et al. 2007). The IKMC consortium has generated mainly conditional but also constitutive mutations, with the former class of mutations facilitating tissue-specific assessment of gene function at desired time points, especially in situations where an essential requirement of a gene product in one context can exclude analysis in another.

Table 3.

Relevant IKMC web sites

| Function | Acronym | Full name | Web address |

|---|---|---|---|

| PORTAL | IKMC | International Knockout Mouse Consortium | www.knockoutmouse.org |

| PRODUCTION PIPELINE | EUCOMM | European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Program | www.knockoutmouse.org/about/eucomm |

| EUCOMMTOOLS | EUCOMM: Tools for Functional Annotation of the Mouse Genome | www.knockoutmouse.org/about/eucommtools | |

| KOMP | Knockout Mouse Project | www.knockoutmouse.org/about/komp | |

| NorCOMM | North American Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Project | www.norcomm.org | |

| Sanger | Sanger Institute Mouse Genetics Program (MGP) | www.sanger.ac.uk/mouseportal/ | |

| TIGM | Texas A&M Institute for Genomic Medicine | www.tigm.org | |

| GENETIC TOOL BOX | Create | Coordination of Cre resources | www.creline.org |

| MGI Cre | Recombinase (Cre) Portal | www.creportal.org | |

| Jax Cre | Jax Cre repository | www.cre.jax.org | |

| GENSAT Cre | GENSAT Cre mice | www.gensat.org/cre.jsp | |

| IMSR Cre | IMSR Cre archive | www.findmice.org/fetch?page=imsrSummary&query=cre+recombinase | |

| Cre-X-Mice | Cre-X-Mice | http://nagy.mshri.on.ca/cre_new/index.php | |

| ICS-CreZoo | ICS CreERT2 Zoo | www.ics-mci.fr/crezoo.html | |

| CanEuCre | Brain specific Cre mice | www.caneucre.org | |

| TgDb | Transgenic Mice Database (TgDb) | www.bioit.fleming.gr/tgdb/ | |

| DISSEMINATION | EuMMCR | European Mouse Mutant Cell Repository | www.eummcr.org |

| KOMP | KOMP Repository | www.komp.org | |

| CMMR | Canadian Mouse Mutant Repository | www.cmmr.ca | |

| TIGM | Texas A&M Institute for Genomic Medicine | www.tigm.org | |

| JAX | Jackson Laboratory Mice and Services | www.jaxmice.jax.org | |

| EMMA | European Mouse Mutant Archive | www.emmanet.org | |

| MMRRC | Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center | www.mmrrc.org | |

| PHENOTYPING | Europhenome | Mouse Phenotyping Resource | www.europhenome.org |

| EuMODIC | European Mouse Disease Clinic | www.eumodic.org | |

| TCP | Toronto Centre for Phenogenomics | www.phenogenomics.ca | |

| KOMP | KOMP Phenotyping Pilot | http://kompphenotype.org | |

| IMPC | International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium | http://mousephenotype.org |

IKMC technology

The IKMC mutant ES cell resources have been developed for the most part in a C57BL/6N genetic background using cell lines that have achieved clonal germline transmission rates of up to 80 % (Pettitt et al. 2009). Mutations were generated initially by using both gene-trapping and gene-targeting technologies. However, the greater utility and desirability of targeted alleles, designed and generated with nucleotide precision, led to phasing out of gene trapping as the efficiency of the high-throughput gene-targeting pipelines became established. Progressive improvements in mouse genome annotation, computational targeting vector design, and 96-well recombineering protocols as well as high efficiencies of gene targeting have facilitated the rapid construction of targeted ES cell clones at unprecedented rates (Skarnes et al. 2011).

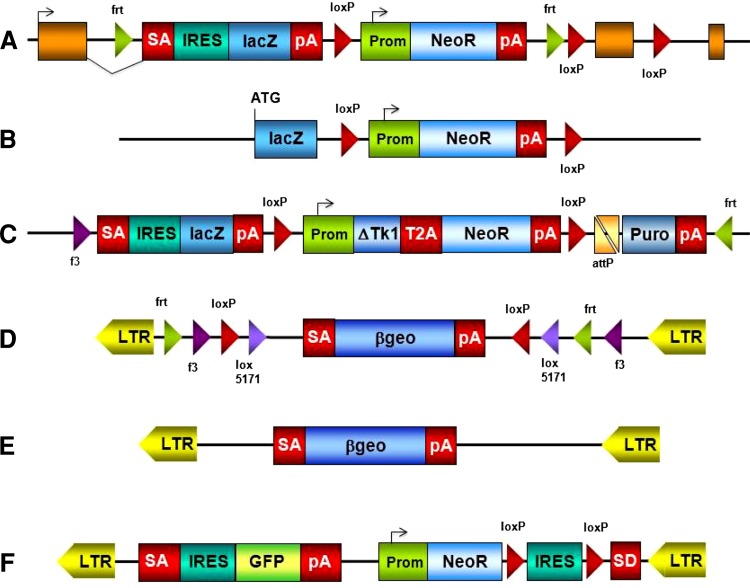

The alleles generated by IKMC members are lacZ tagged and are either null/conditional or null/deletion alleles (Fig. 1). The largest category of targeted clones in the resource contains an allele design known as “knockout-first” from which conditional alleles can be established following exposure to a site-specific recombinase. A conditional allele is created by the deletion of a critical exon which is flanked by loxP sites. Critical exons are those that (1) when deleted, shift the reading frame, (2) are common to all known isoforms, and (3) are contained in the first 50 % of the coding region. Conditional alleles are also amenable to further modification by recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE), which can be used to insert other coding sequences into these alleles (Osterwalder et al. 2010; Schnütgen et al. 2011). The other major class of mutations in the resource comprises lacZ-tagged nulls, constructed as large deletions that are not amenable to further modification (Valenzuela et al. 2003).

Fig. 1.

Vectors used by the IKMC: targeting vectors: a EUCOMM/KOMP-CSD knockout-first allele; b KOMP-Regeneron null allele generating large deletions; c NorCOMM promoter-driven targeting vector. Most commonly used trapping vectors: d conditional EUCOMM vector rsFlipROSAβgeo*; e TIGM vector VICTR76; f NorCOMM vector UPA

IKMC ES cell and mouse resources

Currently, the IKMC ES cell resource contains targeted and trapped alleles for 17,473 unique protein-coding genes. The targeted ES cell resource contains mutations in 13,840 unique genes of which 10,100 are null/conditional. The ES cell gene-trap resource contains mutations in 11,539 unique genes of which 4,414 are conditional (Table 1, www.knockoutmouse.org). Due to the random nature of gene trapping, there is some overlap and redundancy between the resources. In general, the IKMC has generated a median of four independent clones per gene. This redundancy not only helps to assure germline transmission but also provides significant allelic diversity (e.g., conditional or nonconditional alleles, different insertion sites, and vector designs). The use of 129 Sv ES cells early in the project for the gene-trap resource also provides the option of studying mutations in the same gene in two different genetic backgrounds for 4,600 genes in the resource.

Table 1.

IKMC progress (as of February 2012)

| Total genes | KOMP | EUCOMM | NorCOMM | TIGM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSD | Regeneron | ||||

| Targeting vectors | 6,577 | 5,905 | 8,379 | 916 | – |

| Targeted ES cells | 5,244 | 4,196 | 6,887 | 609 | – |

| Trapped ES cells | 4,414 | 3,595 | 9,390 | ||

| Mutant mice | 409 | 359 | 647 | 42 | 252 |

The process of converting IKMC ES cell resources into mice was initiated alongside the gene-targeting and -trapping pipelines as a systematic quality control measure and also for phenotyping purposes. So far, 1,709 mutant mouse lines have been established by all the IKMC members (Table 1). Generation of mice at scale in addition has taken place in organized efforts in a few centers, coupled with systematic phenotyping programs such as the EC-supported EUMODIC Project and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute’s Mouse Genetics Programme (MGP) (Table 3). As of July 2012, from both projects’ databases, i.e., www.europhenome.org and www.sanger.ac.uk/mouseportal, already 919 targeted lines can be identified that have been phenotypically examined. Of these, 652 have an annotated phenotype.

IKMC repositories and distribution

Repositories have an essential function to secure and maintain the investment in the resource for future generations of scientists. Repositories have the obligation to ensure and preserve the quality of the resource and to act as honest brokers with efficient, unrestricted, and unencumbered distribution to third-party users.

The distribution of IKMC vectors and ES cells takes place through several repositories in Europe, the US, and Canada (EuMMCR, KOMP, TIGM, and CMMR, Tables 2, 3). The repositories conduct stringent quality control on the vectors and ES cell clones prior to distribution to ensure the integrity of each allele. They currently distribute nonoverlapping sectors of the IKMC resource to a global user group. Altogether, these centers have already distributed 1,029 targeting vectors and 4,126 mutant ES cell alleles.

Table 2.

IKMC reagents distributed (as of February 2012)

| Type of material | KOMP | EuMMCR/EMMA | CMMR | TIGM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting vectors | 677 | 346 | 6 | – |

| Mutant ES cell clones (alleles) | 3,798 (1,345) | 5,041 (1,867) | 520 (311) | 603 (603) |

| Mutant mice (alleles) | 430 (310) | 600 (530) | 19 (15) | 252 (252) |

The IKMC mice are distributed through EMMA, MMRRC/KOMP, TIGM, and CMMR, the European, US, and Canadian mouse repositories, respectively (Tables 2, 3). To date, of the 1,709 mutated mouse lines, 1,107 (65 %) have been distributed outside of the center in which they were initially produced (Table 2). The dominant impact of IKMC resources on the activity of these repositories is already apparent, e.g., more than 50 % of mice distributed by EMMA were derived from IKMC resources. IKMC mice are also being generated and analyzed in distributed activities by hundreds of individual specialist laboratories worldwide, which to date have cumulatively received 4,126 mutant ES cell alleles from the repositories.

In summary, to date already 6,262 mutant alleles have been distributed worldwide as vectors, ES cells, or mice (about 35 % of IKMC alleles available), and the international requests are still increasing.

IKMC web portal

The integrated, public IKMC web portal (http://www.knockoutmouse.org) summarizes the IKMC progress and enables researchers to obtain IKMC genetic resources from designated repositories. It links to IKMC members’ web pages and to related genetic resources such as those available from the International Gene Trap Consortium (IGTC) and the International Mouse Strain Resource (IMSR) (Table 3) (Ringwald et al. 2011). The IKMC alleles are displayed on the Ensembl and UCSC genome browsers with standardized allele identification registered in Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI, www.informatics.jax.org) database.

The IKMC web portal supports use of the genetic resources through provision of detailed molecular structures of mutant alleles. Researchers may nominate genes of interest for prioritization if targeted mutations are not yet available, although the current coverage of 87 % of the protein-coding genes provides a high chance that a useful allele has already been generated.

IKMC and beyond

The IKMC ES cell resource was envisaged as an essential stepping stone required for the efficient generation of mouse mutants at scale. This resource is nearing completion and is already being accessed by novel large-scale programs to generate mice for phenotypic analysis. An organized effort, the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC), has just been launched (Table 3). Many centers worldwide will contribute to this effort, ultimately generating and analyzing more than 15,000 mouse mutants based on the IKMC resource over the next decade, establishing what will constitute a functional Encyclopedia of the Mammalian Genome.

The IKMC resource, although very comprehensive, still remains incomplete. Ongoing efforts, performed mainly by the EUCOMMTools project (Table 3), will improve genome coverage and the quality of the mutant alleles in the resource over the next 3 years. This will include replacing gene-trap alleles with targeted ones and generating conditional alleles when only a null allele is available. The resource will also continue to expand to cover other classes of genes such as noncoding RNAs.

The IKMC resource includes both vectors and ES cells that can be further modified by RMCE to insert different coding sequences into any conditional mutant IKMC allele such as reporter genes, recombinases, and human orthologs or, e.g., an allele’s missense mutations. In an era in which an extraordinary amount of human variation sequence is becoming available, functional assessment of variants will require analysis under physiological levels of expression and regulation, most reliably achieved by insertion into the mouse orthologous locus.

The examination of a null allele is the requisite first step in order to establish the ground state (null phenotype) of any gene function in the genome. Subsequently, it is desirable to conduct more focused analysis by controlling the generation of the mutation temporally and spatially. The conditional sector of the resource is designed for use with the recombinase Cre, for which a number of transgenic mouse lines are available. The number and characterization level of these lines will increase with various initiatives currently underway [like EUCOMMTools, CanEuCre, and the NorCOMM successor project NorCOMM2LS (Table 3)], and will eventually cover the majority of embryonic and adult tissues and cell types.

Phenotypic analysis of mutant mouse lines generated from IKMC resources enables a better understanding of complex biology such as whole organism physiology, behavior, and adult tissue integrity. In addition, biological insights can also be gained from analysis of cellular phenotypes in culture. IKMC resources facilitate the generation of homozygous mutant ES cells by retargeting the second allele in vitro.

Genetic manipulation of mouse ES cells has reached such a degree of efficiency and sophistication that ES cells can be generated with virtually any genetic change. The success of these technologies provides the groundwork for extension to other mammalian species such as rat, and to human ES and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the European Commission (EC, LSHG-CT-2005-018931, Health-F4-2010-261492), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Genome Canada, and the State of Texas for funding.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Contributor Information

Allan Bradley, Email: abradley@sanger.ac.uk.

Wolfgang Wurst, Email: wurst@helmholtz-muenchen.de.

References

- Austin CP, Battey JF, Bradley A, Bucan M, Capecchi M, Collins FS, Dove WF, Duyk G, Dymecki S, Eppig JT, et al. The knockout mouse project. Nat Genet. 2004;36:921–924. doi: 10.1038/ng0904-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auwerx J, Avner P, Baldock R, Ballabio A, Balling R, Barbacid M, Berns A, Bradley A, Brown S, Carmeliet P, et al. The European dimension for the mouse genome mutagenesis program. Nat Genet. 2004;36:925–927. doi: 10.1038/ng0904-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins FS, Rossant J, Wurst W. A mouse for all reasons. Cell. 2007;128:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder M, Galli A, Rosen B, Skarnes WC, Zeller R, Lopez-Rios J. Dual RMCE for efficient re-engineering of mouse mutant alleles. Nat Methods. 2010;7:893–895. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettitt SJ, Liang Q, Rairdan XY, Moran JL, Prosser HM, Beier DR, Lloyd KC, Bradley A, Skarnes WC. Agouti C57BL/6N embryonic stem cells for mouse genetic resources. Nat Methods. 2009;6:493–495. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringwald M, Iyer V, Mason JC, Stone KR, Tadepally HD, Kadin JA, Bult CJ, Eppig JT, Oakley DJ, Briois S, et al. The IKMC web portal: a central point of entry to data and resources from the International Knockout Mouse Consortium. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D849–D855. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnütgen F, Ehrmann F, Poser I, Hubner NC, Hansen J, Floss T, deVries I, Wurst W, Hyman A, Mann M, von Melchner H. Resources for proteomics in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Methods. 2011;8:103–104. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0211-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarnes WC, Rosen B, West AP, Koutsourakis M, Bushell W, Iyer V, Mujica AO, Thomas M, Harrow J, Cox T, et al. A conditional knockout resource for genome-wide analysis of mouse gene function. Nature. 2011;474:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Frendewey D, Gale NW, Econonomides AN, Auerbach W, Poueymirou WT, Adams NC, Rojas J, Yasenchak J, et al. High-throughput engineering of the mouse genome coupled with high-resolution expression analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:652–659. doi: 10.1038/nbt822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace HAC, Marques-Kranc F, Richardson M, Luna-Crespo F, Sharpe JA, Hughes J, Wood WG, Higgs DR, Smith AJH. Manipulating the mouse genome to engineer precise functional syntenic replacements with human sequence. Cell. 2007;128:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]