Abstract

Rates of cerebral blood flow (CBF) and glucose consumption (CMRglc) rise in cerebral cortex during continuous stimulation, while the oxygen-glucose index (OGI) declines as an index of mismatched coupling of oxygen consumption (cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen—CMRO2) to CBF and CMRglc. To test whether the mismatch reflects a specific role of aerobic glycolysis during functional brain activation, we determined CBF and CMRO2 with positron emission tomography (PET) when 12 healthy volunteers executed finger-to-thumb apposition of the right hand. Movements began 1, 10, or 20 minutes before administration of the radiotracers. In primary and supplementary motor cortices and cerebellum, CBF had increased at 1 minute of exercise and remained elevated for the duration of the 20-minute session. In contrast, the CMRO2 numerically had increased insignificantly in left M1 and supplementary motor area at 1 minute, but had declined significantly at 10 minutes, returning to baseline at 20 minutes. As measures of CMRglc are impossible during short-term activations, we used measurements of CBF as indices of CMRglc. The decline of CMRO2 at 10 minutes paralleled a calculated decrease of OGI at this time. The implied generation of lactate in the tissue suggested an important hypothetical role of the metabolite as regulator of CBF during activation.

Keywords: energy metabolism, lactate, positron emission tomography, neurovascular coupling

Introduction

Here, we raise the question of the relationships among changes of cerebral blood flow (CBF) and rates of oxygen (cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen —CMRO2) and glucose consumption (CMRglc) during functional activation of brain tissue. It is well known that changes of CBF and CMRglc occur in parallel (Gjedde et al, 2002; Paulson et al, 2010) but it is a major issue how this correlation is maintained, as glucose transport is insensitive to flow changes because of the low net extraction of ∼10% (Gjedde et al, 2002). An early indication of the complexity of the hemodynamic response to stimulation was the unexpected observation that the magnitude of CMRO2 rises very little during simple somatosensory stimulation, despite substantial focal increases of CBF in the sensory-motor cortex (Fox and Raichle, 1986; Fox et al, 1988; Fujita et al, 1999).

Simultaneous measurements of arteriovenous differences of oxygen and glucose provide the strongest evidence that the oxygen-glucose index (OGI) declines after stimulation (Madsen et al, 1999; Schmalbruch et al, 2002, Ido et al, 2004; Dalsgaard et al, 2004), in agreement with uncoupling of CMRO2 from CMRglc. It is a logical speculation that a commensurate increase of lactate generation must result from the mismatch of CMRglc and CMRO2. We propose that this possible rise of lactate could also serve to increase CBF. Thus, the issue of the mechanism underlying possible parallel changes of CBF and CMRglc is resolved if the direct response to stimulation of functional brain activity in fact is an increase of CMRglc, which in turn would elicit a change of CBF by means of increased generation of lactate.

At 4 minutes of continued stimulation, complex motor activity is associated with a significant increment of oxygen metabolism (Vafaee and Gjedde, 2004). The evidence that a complex stimulus applied at length evokes significant increases of CMRO2 in visual and motor cortices (Vafaee and Gjedde, 2000, 2004) is consistent with the novel claim that the change of oxidative metabolism occurs after a corresponding change of the generation of lactate (Gjedde and Marrett, 2001). The claim is also supported by calculation that shows that aerobic glycolysis responds to stimulation with time constants of the order of milliseconds while increases of oxidative metabolism reflect time constants of the order of seconds or minutes (Gjedde and Marrett, 2001; Gjedde 2007). Mintun et al (2002) confirmed the significant rise of CMRO2 for stimulus intervals as long as 25 minutes, implying that increased energy turnover of the activated brain eventually is met by elevation of oxidative metabolism. Most recently, Vaishnavi et al (2010) showed that increased rates of aerobic glycolysis (defined as glucose utilization in excess of CO2 generation, despite sufficient oxygen to metabolize all glucose to CO2) satisfy the transiently increased brain energy turnover in the presence of the lower time constants of pyruvate conversion to lactate with matching decline of the OGI during stimulation (Boyle et al, 1994; Madsen et al, 1999; Schmalbruch et al, 2002).

When the stimulation-induced changes of glucose metabolism match the changes of blood flow as well as the Blood Oxygenation Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal changes during activation, the changes of the oxygen extraction fraction ( ) are equivalent to the changes of OGI, as representative of the same underlying uncoupling of oxidative metabolism from blood flow and glucose metabolism during the nonsteady states of physiological activation of brain tissue. The link between blood flow and glucose metabolism may be related to lactate generation through adjustment of the NADH/NAD+ ratio (Mintun et al, 2004; Gordon et al, 2009), which qualifies lactate as a transmitter of information on the state of regional metabolism.

) are equivalent to the changes of OGI, as representative of the same underlying uncoupling of oxidative metabolism from blood flow and glucose metabolism during the nonsteady states of physiological activation of brain tissue. The link between blood flow and glucose metabolism may be related to lactate generation through adjustment of the NADH/NAD+ ratio (Mintun et al, 2004; Gordon et al, 2009), which qualifies lactate as a transmitter of information on the state of regional metabolism.

We carried out the present study to assess the possible role of aerobic glycolysis during functional brain activation. As regional values of CMRO2 rise less in response to a complex motor task than predicted by the changes of CBF and CMRglc, we estimated the generation of lactate on the condition that the rates of CBF and CMRglc change in parallel. To test the hypothesis that the rise of CBF depends on the generation of lactate, we used positron emission tomography (PET) to measure the changes of CBF and CMRO2 in a group of healthy volunteers during the performance of finger tapping, a complex motor task, executed for lengths of time ranging from 1 to 20 minutes. The results supplement the earlier study of CBF and CMRO2 increases after 4 minutes of motor activation. We used calculations of the  and the equivalent OGI to estimate the generation of lactate and to correlate the generation with the measures of CBF.

and the equivalent OGI to estimate the generation of lactate and to correlate the generation with the measures of CBF.

Materials and methods

The study group consisted of fourteen right-handed healthy normal volunteers (seven men and seven women) of whom two were excluded (one because of technical problems during the tomography and another due to inability to keep finger movements in pace with the metronome, as verified by video camera), aged between 21 and 31 years (mean±s.d.: 26±3.5 years). The subjects were studied at baseline and after 1, 10, and 20 minutes of motor task execution with right-hand finger-to-thumb tapping at 3 Hz. The study was approved by local research committee before initiation. All subjects gave written informed consent to the protocol, approved by the Research Ethics Committee of County Aarhus (now Central Region), Denmark. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations described in Good Clinical Practice documentation.

Positron Emission Tomography

The PET studies were performed with the ECAT EXACT HR (CTI/Siemens, Knoxville, TN, USA) whole-body tomograph, operating in a 3D acquisition mode, which has a transverse resolution of 3.6 to 7.4 mm and an axial resolution of 4.0 to 6.7 mm. Each PET scan was a dynamic 3-minute scan of 21 frames (12 frames of 5 seconds, 6 frames of 10 seconds, and 3 frames of 20 seconds). The images were reconstructed as 128 × 128 matrices of 2 mm × 2 mm pixels using filtered back projection with a 0.5 cycles−1 ramp filter (full width at half maximum—FWHM), followed by a 6 mm Gaussian filter resulting in an isotropic resolution of 7.2 mm. Reconstructed images were corrected for random and scattered events, detector efficiency variations, and dead time. Before the emission recordings, three orbiting rod transmission sources, each containing 185 MBq of 68Ge, were used for attenuation correction. The subjects were positioned in the tomograph with their heads immobilized in a customized head holder. A short indwelling catheter was placed into the left radial artery for blood sampling and blood gas examination. Arterial blood radioactivity was automatically measured by an automatic blood sampling system (one sample every half second), corrected for delay and dispersion, and calibrated using a well counter, which was cross-calibrated to the tomograph. The subjects inhaled 1,000 MBq of 15O-O2 in a single breath at the start of each CMRO2 scan and received 500 MBq of H215O intravenously at the start of each CBF scan. The sequences of CBF and CMRO2 scans as well as the stimulation durations were randomized across the subjects. The magnitudes of CMRO2 and CBF were calculated with an application of the two-compartment method (Blomqvist 1984; Ohta et al, 1992, 1996). Each subject also underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in a GE (1.5 T) superconducting magnet for structural-functional (MRI-PET) correlation with a T1-weighted, 3D fast-field echo sequence (echo time 4.2 ms, repetition time 10.6 ms) consisting of 116 slices of 1.5 mm thickness with 256 × 256 pixels each.

Activation Paradigm

The subjects performed finger-to-thumb apposition movements of the right and dominant hand. The right thumb was repeatedly applied to the tips of all other fingers of the right hand at a frequency of 3 Hz for 1, 10, and 20 minutes before the tomography. All subjects were asked to match the rate of apposition to the rhythm of a metronome. Thus, tasks began 1, 10, and 20 minutes before tracer administration and continued during the subsequent 3-minute dynamic PET. In the baseline condition, the subjects performed no task. We recorded the subjects' finger movements by video camera to assess the compliance with the prescribed frequency of each tomography.

Image Analysis

Magnetic resonance images were transformed into stereotactic coordinates (Talairach and Tournoux, 1988) by means of an automatic registration algorithm (Collins et al, 1994). The reconstructed PET images were coregistered to the subjects' MRI scans using an implementation the Automatic Image Registration algorithm (Woods et al, 1992). For this purpose, the sum of the PET emission images across all frames was calculated for each scan. Then, the MRI image was aligned with the summed PET image. To correct for between-scan subject movements, automatic PET-to-PET registration was also performed (Woods et al, 1993). This method used the first PET scan (summed across frames) as the registration target for each subsequent summed PET scan. The global CBF and CMRO2 were determined for each subject by means of a binarized brain mask, which excluded all extracerebral voxels. This mask was created by setting a threshold and manually editing the average MRI of 305 normal brains acquired at the Montreal Neurological Institute for each subject. The global CBF and CMRO2 were then determined by averaging the values of all intracerebral voxels. The reconstructed PET images averaged across subjects were transformed into stereotactic coordinates, and blurred with a Gaussian filter of 18 mm × 18 mm × 18 mm.

Group Analysis

We used a statistical analysis based on the general linear model with correlated errors modified by Worsley et al (2002) to accommodate PET data. The analysis overcame the weakness associated with pooled standard deviations by initially smoothing the standard deviation using a regularized variance ratio to increase the degrees of freedom. The result is mean subtracted normalized image volumes (task minus baseline) with relative changes of CBF and CMRO2 calculated and presented as significant activation clusters.

Volume-of-Interest Analysis

We determined absolute regional values of CBF and CMRO2 for each subject in volumes-of-interest outlined by means of anatomical masks generated in the previous study (Vafaee and Gjedde, 2004). In that study, average PET images were registered on magnetic resonance images in Talairach space. Then, a threshold of 50% of the peak z value of the most significant activation cluster was chosen. Subsequently, a mask of the thresholded cluster was adjusted to the anatomy of the activation area (visually verified by an anatomist) by editing out voxels lying outside the anatomical area. This mask was applied to the individual nonnormalized CBF and CMRO2 images to extract the absolute values of the CBF and CMRO2 by averaging the voxel values within each mask. Statistical analysis of volumes-of-interest results were obtained with one-way repeated ANOVA analysis, which was subsequently confirmed with ad-hoc paired Student's t-test.

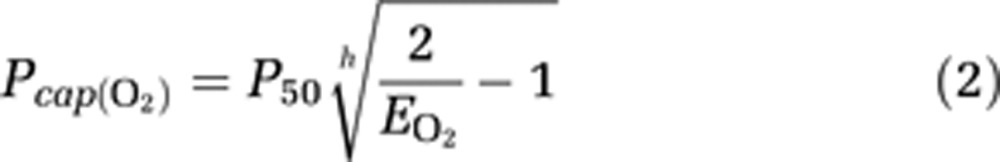

Indices of Oxygen Delivery

To evaluate the adequacy of oxygen delivery in relation to the flow-metabolism coupling in the activation state, we calculated the  as

as

|

where Ca represents the arterial concentration of oxygen. The average capillary oxygen tension then is (Gjedde et al, 2005),

|

where P50 is the hemoglobin half-saturation tension of oxygen (27 mmHg) and h is the Hill coefficient of oxygen binding to hemoglobin (2.7). The average mitochondrial oxygen tension, i.e., the tension estimated at the end of the diffusion path then is (Gjedde et al, 2005),

|

where L (4.4 μmol/hg per minute) is the tissue oxygen conductivity as defined by Vafaee and Gjedde (2000).

Results

By visual examination of the videotapes, we judged that all subjects (except one who was excluded from the study) performed the task as described in Materials and methods. As one PET acquisition was lost to technical failure, the study includes data from 12 subjects.

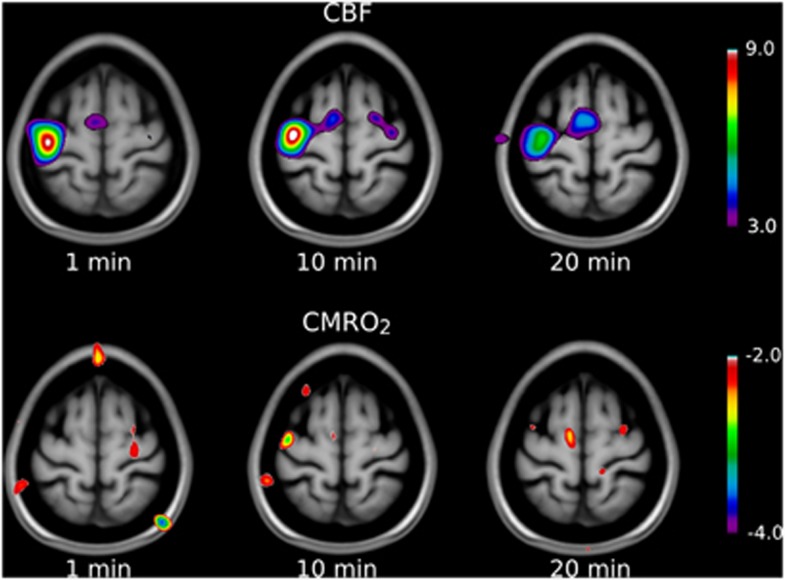

Arterial blood gas information in all of the baseline and activation states were examined to exclude the effect of their changes on CBF and CMRO2 values. There were no statistical differences among PCO2 and PO2 values in any states (Table 1). Global values of CBF and CMRO2 were determined for each of the 12 subjects and averaged for each of the activation conditions and the baselines, as listed in Table 2. There was no significant effect of condition on whole-brain CBF (P>0.05) or CMRO2 (P>0.05), by one-way repeated-measures ANOVA. The parametric maps of mean normalized images revealed two distinct highly significant clusters of CBF activation in the left primary motor cortex (M1) and left supplementary motor cortex (supplementary motor area—SMA) in all three activation states in the present study (Figure 1, upper panel). As well, CBF increased significantly in cerebellum after 1 minute of activation. The CMRO2 analysis revealed no significant cluster of activation in any of the conditions, although there were clusters just below significance in M1 and SMA after 1 minute of activation (Figure 1, lower panel).

Table 1. Arterial blood gasses (PO2 and PCO2) in all activation and baseline states.

|

Baseline |

1 minute |

10 minutes |

20 minutes |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBF | CMRO2 | CBF | CMRO2 | CBF | CMRO2 | CBF | CMRO2 | |

| PO2 (kPa) | 13.6±0.6 | 13.5±0.9 | 13.9±0.7 | 13.3±1.0 | 13.9±0.6 | 13.3±0.9 | 13.8±0.7 | 14.0±0.3 |

| PCO2 (kPa) | 4.9±0.4 | 5.1±0.2 | 5.0±0.3 | 5.1±0.4 | 4.8±0.3 | 5.0±0.5 | 5.0±0.5 | 5.1±0.3 |

CBF, cerebral blood flow; CMRO2, cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen.

No statistically significant differences existed among the blood gas values of the states (the data are presented as mean±standard deviation).

Table 2. Average whole-brain CBF and CMRO2 values as a function of apposition finger-to-thumb movement measured in all subjects (the data are presented as mean±standard deviation).

| Scan condition | CBF (mL/hg per minute) | CMRO2 (μmol/hg per minute) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 60±8 | 177±22 |

| 1 minute | 61±9 | 180±19 |

| 10 minutes | 60±9 | 170±18 |

| 20 minutes | 59±8 | 174±19 |

CBF, cerebral blood flow; CMRO2, cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen.

Figure 1.

Parametric maps of relative changes (compared with baseline) in cerebral blood flow (CBF) and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) during finger-to-thumb apposition movements of right hand at different time intervals. Significant level is t>4 or t<−4, which is shown by the scale bars implying that any activation or deactivation blob (different from region of interest, ROI) on the subtraction images with t values of 4 or below −4 is statistically significant. As shown in the upper panel, CBF significantly rose from the baseline in the left M1, and supplementary motor area (SMA) in all three time points. The lower panel depicts the changes of CMRO2 after the finger tapping in three time intervals. Although there were no significant CMRO2 increases from the baseline (except at 1 minute when CMRO2 increased by an amount close to significance; P=0.06), the magnitudes in M1 and SMA significantly decreased from 1 minute to 10 minutes as depicted by negative peaks in the figure. At 20 minutes, CMRO2 values returned to values similar to baseline.

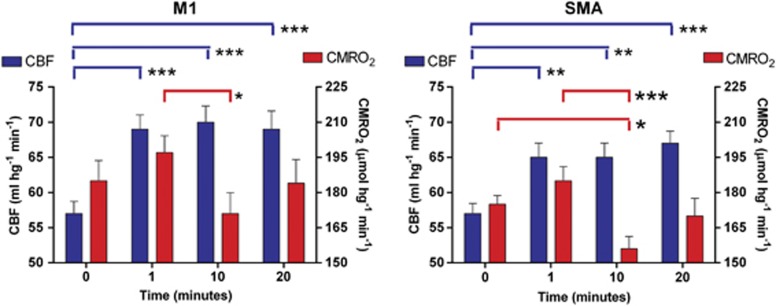

The absolute values of CBF and CMRO2 of cortical areas activated by the motor task were also determined by use of the masks described in Materials and methods. The values were then averaged for all subjects. In the left primary motor cortex, regional CBF had increased significantly during the stimulation (Figure 2, left panel). The Euler characteristic, i.e., the approximation of a P value for the local maximum, revealed statistically significant changes in all of the activation states (P<0.0001), although there were no significant differences among any of the activation states. In the left SMA, the regional CBF also had significantly increased after stimulation (Figure 2, right panel). The differences among changes in each activation state were not statistically significant. The Euler characteristic showed that all changes were significant (P<0.001). There were no significant changes of CBF in the right or left putamen after the activation. In the right cerebellum, the regional CBF values increased after 1 minute of finger motion as well as 10 and 20 minutes although the increase was significant only at 1 minute (P<0.01) and fell short of significance at the later times (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) values at the baseline and activation states (1, 10, and 20 minutes) in the left M1 (left panel) and the left supplementary motor area (SMA) (right panel). Number of asterisks indicates level of significance.

Table 3. CBF and CMRO2, values in the right cerebellum as a function of apposition finger-to-thumb movement (the data are presented as mean±standard deviation).

| Scan condition | CBF (mL/hg per minute) | CMRO2 (μmol/hg per minute) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 61±8 | 205±22 |

| 1 minute | 71±9a | 215±33 |

| 10 minutes | 67±9 | 207±23 |

| 20 minutes | 67±8 | 208±39 |

CBF, cerebral blood flow; CMRO2, cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen.

Denotes a statistical significance compared with the baseline values (P<0.01).

The CMRO2 had increased in the left primary motor cortex close to significantly at 1 minute (P=0.06), followed by a significant decline at 10 minutes (P<0.005), and return to the baseline values at 20 minutes. The CMRO2 of the left SMA revealed the same change, having risen at one minute (P<0.01), followed by significant decline at 10 minutes (P<0.004) and return to the baseline value at 20 minutes (Figure 2, right panel). At no time did the change of CMRO2 reach significance in the cerebellum or putamen.

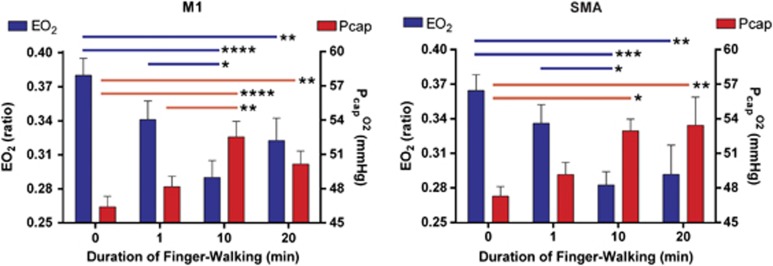

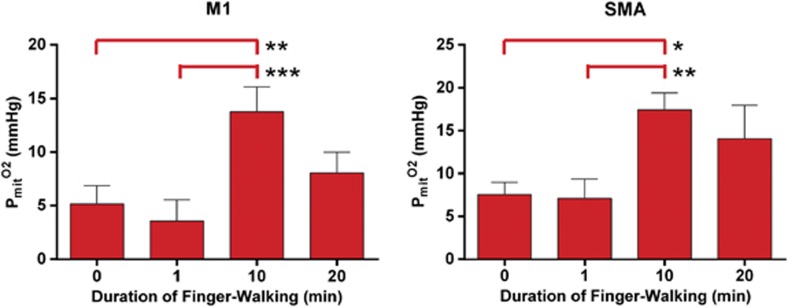

As expected from the results presented above, the net  revealed significant decline in M1 and SMA at 10 and 20 minutes of continuous motor activity (Figure 3). The effect of the declines was significant increases of the average capillary, Pcap(O2), at 10 and 20 minutes as well (Figure 3), although no increase of CMRO2 was mediated at these times. In fact, the average mitochondrial oxygen tension, Pmit(O2), was significantly elevated at 10 minutes (Figure 4), in agreement with the decline of CMRO2 at this time.

revealed significant decline in M1 and SMA at 10 and 20 minutes of continuous motor activity (Figure 3). The effect of the declines was significant increases of the average capillary, Pcap(O2), at 10 and 20 minutes as well (Figure 3), although no increase of CMRO2 was mediated at these times. In fact, the average mitochondrial oxygen tension, Pmit(O2), was significantly elevated at 10 minutes (Figure 4), in agreement with the decline of CMRO2 at this time.

Figure 3.

Oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) and capillary oxygen tension (Pcap(O2)) values at the baseline and activation states (1, 10, and 20 minutes), calculated from the measured values of cerebral blood flow (CBF) and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) according to Equation 2. Left and right panels depict the data in the left M1 and the left supplementary motor area (SMA), respectively. Number of asterisks indicates level of significance.

Figure 4.

Mitochondrial oxygen tension (Pmit(O2)) values at the baseline and activation states (1, 10, and 20 minutes) calculated from the measured values of cerebral blood flow (CBF) and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) by means of Equation 3.

Discussion

It is well established that elevated neural activity results in increased CBF, which in turn increases the delivery of oxygen. However, the precise relationship between the CBF and oxygen consumption changes during the activation is unknown, as is the mechanism mediating the coupling. As brain tissue contains relatively little dissolved oxygen, brain work depends on a continuous supply of oxygen from the circulation. However, there is strong evidence that activity-related increases of blood flow rarely are accompanied by proportional increases of oxygen consumption (Fox et al, 1988; Fujita et al, 1999, Gjedde et al, 2002). Nonetheless, most studies show that oxygen consumption is increased to some extent after the application of an appropriate stimulus, particularly when the stimulation is maintained over a period of time (Vafaee and Gjedde, 2000, 2004; Gjedde and Marrett, 2001; Mintun et al, 2002). The benefits of the relatively smaller increase of CMRO2 than of CBF are not clear but current thinking holds that the low tissue oxygen prevents increases of CMRO2, unless a greater relative increase of blood flow serves to maintain oxygen tensions in the capillaries that are sufficient to secure an increased flux of oxygen to the sites of oxygen metabolism (Suwa, 1992; Buxton et al, 2004; Gjedde et al, 2005).

Previous PET results revealed an approximately linear dependence of the increased CBF on the rate of stimulation in auditory (Price et al, 1992), visual (Fox and Raichle, 1985; Vafaee and Gjedde, 2000), and motor (Vafaee and Gjedde, 2004) cortices. Whereas studies of task-evoked changes in CBF are numerous, there are few reports of direct PET measures of CMRO2 in brain activation states. The extent to which CBF and CMRO2 remain coupled during specific kinds of neuronal activity is therefore the topic of intense debate.

The relationships among blood flow and measures of energy metabolism during short- or long-term stimulation have been reported mainly for the visual (Merboldt et al, 1992; Kruger et al, 1998; Lin et al, 2009) and sensorimotor (Fujita et al, 1999, Vafaee and Gjedde, 2004) cortices, and in some of the activations of somatosensory cortex, the oxygen consumption rises very little on simple primary stimulation, despite significant increases of blood flow (Fox and Raichle, 1986; Fujita et al, 1999).

We previously showed frequency-dependent changes of CMRO2 in visual cortex undergoing sustained stimulation by a complex stimulus (Vafaee et al, 1999; Vafaee and Gjedde, 2000). The time-dependent increase of oxygen utilization in continuously activated human visual cortex revealed a mismatch between the progression of CBF and CMRO2 in prolonged activation (Gjedde and Marrett, 2001; Mintun et al, 2002; Lin et al, 2009). We observed the same mismatch in motor cortex when a demanding motor task, i.e., apposition finger tapping at 3 Hz, elicited increases in blood flow and oxygen metabolism with a spatially dissociated distribution in several cortical and subcortical regions of the brain (Vafaee and Gjedde, 2004). The reduction of the extraction of oxygen elevates the average oxygen tension in the capillaries, and the finding is therefore consistent with the claim that increased oxygen diffusion from capillaries to brain tissue depends on a flow-dependent increase of the average oxygen tension in capillaries (Vafaee and Gjedde, 2000; Gjedde et al, 2002), as long as the oxygen tension in mitochondria remains low or constant. As a consequence of low or constant oxygen tension in mitochondria, it follows that oxygen consumption cannot rise in simple proportion to the increased CBF (Suwa, 1992).

Glucose consumption, however, is known to rise in approximate proportion to CBF (Gjedde et al, 2002; Paulson et al, 2010). Although different circumstances or factors may be responsible for the enhancement of blood flow with and without a rise in oxygen consumption, it remains unresolved how the link between CMRglc and CBF is mediated. Ido et al (2004) suggested a role for intracellular NADH as a mediator of this relation, concluding that the near-equilibrium relationship between free cytosolic NADH/NAD+ and lactate/pyruvate ratios is the mechanism that underlies blood flow augmentation in response to stimulation. This role of the NADH/NAD+ ratio is further supported by Mintun et al (2004) who reported a lactate/pyruvate ratio-dependent rise in CBF during stimulation.

The present results show that finger-to-thumb motion of the right hand at 3 Hz evokes an increase of CBF in the contralateral primary motor cortex (M1) and supplementary motor cortex (SMA) at 1 minute of task performance. The CBF increase subsequently persisted for as long as 20 minutes, as illustrated in Figure 2. However, the task led to near-significant increase only of CMRO2 in the M1 and SMA regions at 1 minute after initiation of the task, and the CMRO2 in M1 and SMA declined significantly at 10 minutes of stimulation, returning to baseline at 20 minutes (Figure 2). The resulting U shape of the CMRO2 changes suggests the operation of two opposing linear processes, neither of which is known. For what it is worth, we do believe that the decline of CMRO2 after 10 minutes could be the consequence of increased efficiency of the motor activity, counteracted by a hypothetical increase of oxidative demands of neuronal and synaptic restructuring. This scheme is consistent with the U-shaped changes of OGI, which are known from numerous previous studies, as cited below.

These results are not instructive as evidence of a flow-metabolism coupling mechanism that is thought to benefit the prevailing energy demands of the tissue by adjusting the blood flow rate and thus the oxygen delivery. The OEF (EO2) is a representation of the adequacy of flow-metabolism coupling, which can be used to estimate the average oxygen tension in capillaries (Gjedde et al, 2005). To evaluate the flow-metabolism coupling, we calculated EO2 and the accompanying physiological variables Pcap(O2) (average capillary oxygen tension), and Pmit(O2) (average mitochondrial oxygen) as functions of time during the performance of the finger-tapping task (Figures 3 and 4). As shown in Figure 3 for primary motor cortex (M1), we found a significant decline of EO2 at 1 minute of activation, which declined further at 10 minutes, returning toward the baseline at 20 minutes. The changes of EO2 are consistent with the claim that EO2 must decline for oxygen consumption to be able to rise by means of elevated capillary oxygen tensions at 10 and 20 minutes in both M1 and SMA (Figure 3). Yet, CMRO2 did not actually rise at 10 or 20 minutes when EO2 remained significantly reduced.

We calculated the mitochondrial oxygen tension (Pmit(O2)) to evaluate the effect of the nonlinear flow-metabolism coupling on the tension that is commensurate with the actual delivery of the oxygen. The tension had declined somewhat at 1 minute of activation (though not significantly), but rose significantly at 10 minutes, at which time CMRO2 had declined significantly (Figure 4). The increase of Pmit(O2) at this time is of course consistent with the low oxygen consumption but it leaves unanswered the question of the benefits of the flow increase.

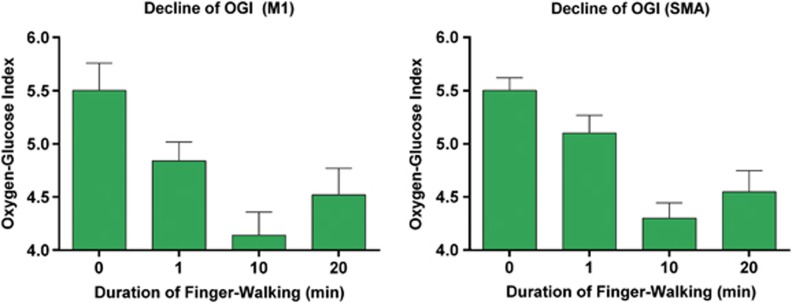

An explanation of possibly parallel blood flow and glucose metabolism changes in activation states is not immediately apparent. The net glucose transfer is regulated by the joint activity of hexokinase and phosphofructokinase and is insensitive to blood flow changes because of the low net extraction of no >10% that has little influence on the average capillary glucose concentration mediating the facilitated diffusion. When the increased glucose metabolism during activation matches the increased CBF, we used the changes of CBF and CMRO2 to calculate possibly changes of the OGI as surrogate marker values of the CMRO2/CMRglc ratio, assuming a baseline ratio of 5.5, consistent with close to 10% aerobic glycolysis and lactate production. As shown in Figure 5, this surrogate marker of OGI declined in M1 and SMA at 1 minute of activation and had further declined at 10 minutes, at the time when CMRO2 also had declined below the baseline and 1 minute values, only to increase at 20 minutes of activation, in complete agreement with direct estimates of OGI by means of arteriovenous difference ratios (Madsen et al, 1999; Schmalbruch et al, 2002; Ido et al, 2004). This evidence of OGI decline is an additional indication that oxidative metabolism fails to increase in parallel with the increase of blood flow. The reduction of OGI also implies that an increased share of ATP production is provided by aerobic glycolysis, as predicted by Vaishnavi et al (2010).

Figure 5.

Oxygen glucose index (OGI) at the baseline and activation states (1, 10, and 20 minutes), calculated according to Equation 5, assuming a baseline OGI of 5.5 and a constant coupling ratio. Left and right panels depict the data in the left M1 and the left supplementary motor area (SMA), respectively.

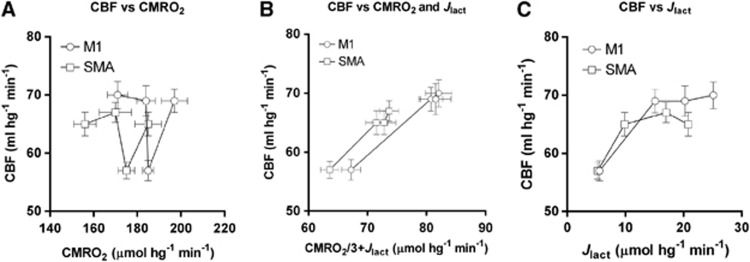

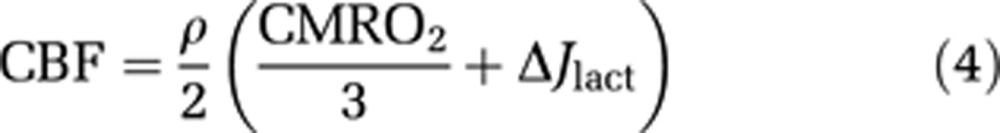

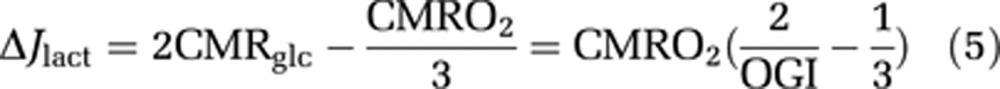

We speculate that increased glucose metabolism may serve as mediator of a flow regulation by lactate. Indeed, if glucose metabolism and blood flow do remain coupled, a potential novel mechanism of flow regulation can be inferred from the relationship,

|

where ρ is the coupling ratio and ΔJlact the net generation of lactate, estimated as,

|

which are both restatements of the speculatively fixed ratio between CBF and CMRglc, of course. If so, relationships suggest that the link between changes of CBF and CMRglc could be the opposite of what has been claimed until now, namely that a change of glucose consumption is the primary response to stimulation, with the newly generated lactate serving as partial mediator of the flow response to secure sufficient oxygen for an impending increase of brain energy turnover (Bergersen and Gjedde, 2012). Figure 6 shows this suggested relationship between the CBF and the rates of oxygen consumption and lactate generation, separately as well as together, implying that the CBF could be adjusted to match the CMRglc rather than the opposite, i.e., that CBF could reflect the intensity of aerobic glycolysis in the brain. Of course, the relation shown in the middle panel is derived entirely from the speculation that rates of CBF and CMRglc change in parallel, and the validity of the deduction rests on the extent to which the observation of parallel changes is upheld in future experiments. This deductive link agrees with a role of lactate as volume transmitter, carrying information of the metabolic state of activated tissue across cell membranes to extended volumes of the brain tissue.

Figure 6.

Flow-metabolism coupling in the M1 and supplementary motor area (SMA). As depicted in (A) and (C), cerebral blood flow (CBF) values (ordinate) are poorly correlated with the observed values of cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) (A) and the values of lactate generation (C), calculated according to Equation 5. However, CBF values are perfectly correlated with the sum of glycolytic units (B), calculated according to Equations 4 and 5 under the assumption of a constant coupling ratio (ρ), close to 1.8, as indicated by twice the slope of the connecting lines in (B).

We attribute the reduction of oxidative metabolism of sensorimotor cortex to a mechanism of habituation to the finger tapping. All subjects were able to perform the task adequately for 20 minutes, on the basis of examination of videotapes, and according to selfreports. Indeed, subjects reported that the ease of execution of the task increased with duration of performance. When the subjects extended the duration of finger-tapping activity to 10 and 20 minutes, oxygen consumption evidently declined at the expense of lactate generation, in keeping with declining motor output declined, as reported by Thomas et al (1989), according to whom inhibition of motor output by inhibitory interneurons is expected to reduce calcium conductance, efferent firing, and oxygen consumption. Hence, the decrease of the oxygen consumption after 10 and 20 minutes could be due to the declining requirement for postsynaptic ATP production, as the task became habituated.

In a study of visual cortex, Mintun et al (2002) reported a persistent increase of CMRO2 as a function of stimulus duration which is at odds with the current findings. However, there are several important differences between the two studies. First, the time points at which the CBF–CMRO2 relationship was examined were different in the two studies. Second, we performed a separate and independent tomography at each stimulation, whereas Mintun et al presented a single continuous stimulus throughout the study when they measured CBF and CMRO2 at several intervals. Also, in the present study, the subjects performed the activation task four times in the course of 2 hours, which in turn could have contributed to habituation.

The most important difference between the two studies is very likely the region of activation; motor cortex in the present study, visual cortex in the study by Mintun et al. The primary visual cortex has the highest concentration of cytochrome c oxidase (Wong-Riley, 1989), and in visual cortex, lactate concentration rises sharply and reaches a peak after a few minutes after activation and then levels off, as the stimulation continues (Prichard et al, 1991; Sappey-Marinier et al, 1992), as also illustrated in Figure 6 (panel C). This attenuation of lactate generation may signify a slowing of aerobic glycolysis, compensated by increased oxygen consumption. Given the abundance of cytochrome c oxidase in visual cortex compared with sensorimotor cortex, an increase in oxygen consumption during prolonged visual stimulation is consistent with an absence of habituation to the ongoing stimulation.

In the previous analysis of finger tapping, the CMRO2 increase in the putamen reached significance (Vafaee and Gjedde, 2004). In the present study, an activation cluster appeared in putamen after 1 minute but never reached statistical significance. The discrepancy arose from the use of less stringent pooled standard deviations, whereas the present study implemented a method of smoothed standard deviations (Worsley et al, 2002).

One limitation of the present data arises from the difference of the results obtained with parametric mapping (cluster analysis) compared with those obtained with region of interest analysis. This difference reflects the normalization of the images used in the cluster analysis, so as to reduce the effects of between-tomography global changes or variance, which is common practice in many imaging activation studies. However, in the region of interest analysis, we used nonnormalized, absolute parametric images of CBF and CMRO2. The normalization of quantitative images prepared with arterial blood samples to obtain physiological values may have diluted the effects associated with the activation states.

In conclusion, we show that the performance of a demanding motor task causes a sharp rise in CBF in sensorimotor and premotor cortices, reaching a plateau at early as at 1 minute. The initial CBF increase is associated with a small but not significant initial increase of oxygen consumption followed by decline at 10 minutes and return to baseline at 20 minutes, which we attribute to habituation. The finding that CBF and CMRO2 changes have different thresholds of activation and different temporal patterns we ascribe to the changes of aerobic glycolysis and the lactate generation that may underlie a mechanism of control of CBF.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Danish Medical Research Council grants 9305246, 9305247, 9601888 and 9802833 and The National Program for Research Infrastructure grant.

References

- Bergersen LH, Gjedde A. Is lactate a volume transmitter of a metabolic states of the brain. Front Neuroenerget. 2012;4:5. doi: 10.3389/fnene.2012.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist G. On the construction of functional maps in positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1984;14:629–632. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1984.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PJ, Scott JC, Krenz AJ, Nagy RJ, Comstock E, Hoffman C. Diminished brain glucose metabolism is a significant determinant for falling rates of systemic glucose utilization during sleep in normal humans. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:529–535. doi: 10.1172/JCI117003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton RB, Uludag K, Dubowitz DJ, Liu TT. Modelling the hemodynamic response to brain activation. Neuroimage Suppl. 2004;1:S220–S233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins DL, Neelin P, Peters TM, Evans AC. Automatic 3D intersubject registration of MR volumetric data in standardized Talairach space. J Comput Assist Tomgr. 1994;18:192–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard MK, Quistorff B, Danielsen ER, Selmer C, Vogelsang T, Secher NH. A reduced cerebral metabolic ratio in exercise reflects metabolism and not accumulation of lactate within the human brain. J Physiol. 2004;554:571–578. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.055053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PT, Raichle ME. Stimulus rate determines regional blood flow in striate cortex. Ann Neurol. 1985;17 (3:303–305. doi: 10.1002/ana.410170315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PT, Raichle ME. Focal physiological uncoupling of cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism during somatosensory stimulation in human subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1140–1144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.4.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PT, Raichle M, Mintun M, Dence C. Nonoxidative glucose consumption during focal physiologic neuronal activity. Science. 1988;241:462–464. doi: 10.1126/science.3260686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita H, Kuwabara H, Reutens DC, Gjedde A. Oxygen consumption of cerebral cortex fails to increase during continued vibrotactile stimulation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:266–271. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199903000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjedde A.2007Coupling of brain function to metabolism: Evaluation of energy requirements Handbook of neurochemistry and neurobiology(Ljtha A, Gibson GE, Dienel GA, eds),Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 343–400. [Google Scholar]

- Gjedde A, Johannsen P, Cold JE, Ostergaard L. Cerebral metabolic response to low blood flow: possible role of cytochrome oxidase inhibition. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1083–1096. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjedde A, Marrett S. Glycolysis in neurons, not astrocytes, delays oxidative metabolism of human visual cortex during sustained checkerboard stimulation in vivo. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1384–1392. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200112000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjedde A, Marrett S, Vafaee M. Oxidative and non-oxidative metabolism of excited neurons and astrocytes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:1–14. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon GR, Iremonger KJ, Kantevari S, Ellis-Davies GC, MacVicar BA, Bains JS. Astrocyte-mediated distributed plasticity in hypothalamic glutamate synapses. Neuron. 2009;64:391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ido Y, Chang K, Williamson JR. NADH augments blood flow in physiologically activated retina and visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:653–658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307458100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger G, Kleinschmidt A, Frahm J. Stimulus dependence of oxygenation-sensitive MRI responses to sustained visual activation. NMR Biomed. 1998;11:75–79. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199804)11:2<75::aid-nbm504>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin AL, Fox PT, Yang Y, Lu H, Tan LH, Gao JH.2009Time-dependent correlation of cerebral blood flow with oxygen metabolism in activated human visual cortex as measured by fMRI Neuroimage 4416–22.Nonlinear coupling between cerebral blood flow, oxygen consumption, and ATP production in human visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:8446-8451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen PL, Cruz NF, Sokoloff L, Dienel GA. Cerebral oxygen/glucose ratio is low during sensory stimulation and rises above normal during recovery: Excess glucose consumption during stimulation is not accounted for by lactate efflux from or accumulation in brain tissue. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:393–400. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199904000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merboldt KD, Bruhn H, Hanicke W, Michaelis T, Frahm J. Decrease of glucose in the human visual cortex during photic stimulation. Magn Reson Med. 1992;25:187–194. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910250119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintun MA, Vlassenko AG, Shulman GL, Snyder AZ. Time-related increase of oxygen utilization in continuously activated human visual cortex. NeuroImage. 2002;16:531–537. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintun MA, Vlassenko AG, Rundle MM, Raichle ME. Increased lactate/pyruvate ratio augments blood flow in physiologically activated human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:659–664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307457100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta S, Meyer E, Fujita H, Reutens DC, Evans AC, Gjedde A. Cerebral 15O water clearance in humans determined by PET: I. Theory and normal values. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:765–780. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta S, Meyer E, Thompson CJ, Gjedde A. Oxygen consumption of the living human brain measured after a single inhalation of positron emitting oxygen. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12:179–192. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson OB, Hasselbalch SG, Rostrup E, Knudsen GM, Pelligrino D. Cerebral blood flow response to functional activation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:2–14. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price C, Wise R, Friston K, Howard D, Patterson K, Frackowiak R. Regional response differences within the human auditory cortex when listening to words. Neurosci Lett. 1992;146:179–182. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90072-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prichard J, Rothman D, Novotny E, Petroff O, Kuwabara T, Avison M, Howseman A, Hanstock C, Shulman R. Lactate rise detected by 1H NMR in human visual cortex during physiologic stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5829–5831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sappey-Marinier D, Calabrese G, Fein G, Hugg JW, Biggins C, Weiner MW. Effect of photic stimulation on human visual cortex lactate phosphates using 1H and 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12:584–592. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmalbruch IK, Linde R, Paulsen OB, Madsen PL. Activation-induced resetting of cerebral metabolism and flow is abolished by beta-adrenegic blockade with propranolol. Stroke. 2002;33:251–255. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.101233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwa K. Analysis of oxygen transport to the brain when two or more parameters are affected simultaneously. J Anesth. 1992;6:297–304. doi: 10.1007/s0054020060297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar stereotactic atlas of the human brain: 3-dimensional proportional system: An approach to cerebral imaging. Stuttgart: George Thieme Verlag; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CK, Woods JJ, Bigland-Ritchie BR. Impulse propagation and muscle activation in long maximal voluntary contractions. J Appl Physiol. 1989;67:1835–1842. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.5.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vafaee M, Gjedde A. Model of blood-brain transfer of oxygen explains non-linear flow-metabolism coupling during stimulation of visual cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow. 2000;20:747–754. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200004000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vafaee MS, Gjedde A. Spatially dissociated flow-metabolism coupling in brain activation. NeuroImage. 2004;21:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vafaee M, Meyer E, Marrett S, Paus T, Evans AC, Gjedde A. Frequency-dependent changes in cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen during activation of human visual cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:272–277. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199903000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaishnavi SN, Vlassenko AG, Rundle MM, Snyder AZ Mintun MA, Raichle ME. Regional aerobic glycolysis in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17757–17762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010459107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Riley MT. Cytochrome oxidase: an endogenous metabolic marker for neuronal activity. TINS. 1989;12:94–101. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods RP, Cherry SR, Mazziotta JC. Rapid automated algorithm for aligning and reslicing PET images. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992;16:620–633. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199207000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods RP, Mazziotta JC, Cherry SR. MRI-PET registration with automated algorithm. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993;17:536–546. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worsley KJ, Liao CH, Aston J, Petre V, Duncan GH, Morales F, Evans AC. A general statistical analysis for fMRI data. NeuroImage. 2002;15:1–15. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]