Abstract

Glucocorticoids are standard of care for many inflammatory conditions, but chronic use is associated with a broad array of side effects. This has led to a search for dissociative glucocorticoids—drugs able to retain or improve efficacy associated with transrepression [nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) inhibition] but with the loss of side effects associated with transactivation (receptor-mediated transcriptional activation through glucocorticoid response element gene promoter elements). We investigated a glucocorticoid derivative with a Δ-9,11 modification as a dissociative steroid. The Δ-9,11 analog showed potent inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-α-induced NF-κB signaling in cell reporter assays, and this transrepression activity was blocked by 17β-hydroxy-11β-[4-dimethylamino phenyl]-17α-[1-propynyl]estra-4,9-dien-3-one (RU-486), showing the requirement for the glucocorticoid receptor (GR). The Δ-9,11 analog induced the nuclear translocation of GR but showed the loss of transactivation as assayed by GR-luciferase constructs as well as mRNA profiles of treated cells. The Δ-9,11 analog was tested for efficacy and side effects in two mouse models of muscular dystrophy: mdx (dystrophin deficiency), and SJL (dysferlin deficiency). Daily oral delivery of the Δ-9,11 analog showed a reduction of muscle inflammation and improvements in multiple muscle function assays yet no reductions in body weight or spleen size, suggesting the loss of key side effects. Our data demonstrate that a Δ-9,11 analog dissociates the GR-mediated transcriptional activities from anti-inflammatory activities. Accordingly, Δ-9,11 analogs may hold promise as a source of safer therapeutic agents for chronic inflammatory disorders.

Introduction

Glucocorticoids have been studied extensively for the past 60 years and are among the most prescribed drugs (Hillier, 2007). They exhibit potent anti-inflammatory properties and are standard of care for many chronic and acute inflammatory conditions, including lupus, myositis, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, and muscular dystrophy (Baschant and Tuckermann, 2010). However, the side-effect profiles of pharmacological glucocorticoids are significant, including muscle atrophy, adrenal deficiency, osteoporosis, spleen atrophy, short stature, and mood and sleep disturbances, among others (Chrousos et al., 1993; DeBosscher, 2010). This has led to a search for dissociative steroids—drugs able to retain activities responsible for molecular and clinical efficacy with the loss of subactivities responsible for side effects (Newton and Holden, 2007).

The mechanism of action of glucocorticoids is through transrepression and transactivation properties. Transrepression involves ligand/receptor interactions with other cellular signaling proteins, such as the inhibition of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) complexes (Rhen and Cidlowski, 2005; Newton and Holden, 2007). Transrepression has been associated with anti-inflammatory activity and clinical efficacy. Transactivation (also termed cis-regulation) is mediated by ligand/glucocorticoid receptor (GR) translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, with ligand/receptor dimers binding directly to glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) in the promoters of target genes (Dostert and Heinzel, 2004). Transactivation has been associated with deleterious side effects (Newton and Holden, 2007).

The balance of efficacy and side effects is well illustrated in the effects of glucocorticoids on muscle tissue. Chronic administration of glucocorticoids leads to relatively rapid muscle loss via the Forkhead box O (FOXO)/atrogin atrophy signaling pathway, and can cause glucocorticoid myopathy (critical care myopathy) (Di Giovanni et al., 2004; Puthucheary et al., 2010). In contrast, chronic glucocorticoids are used in Duchenne muscular dystrophy to increase muscle strength and prolong ambulation, possibly through their anti- inflammatory effect (Bach et al., 2010; Hussein et al., 2010; Escolar et al., 2011). The beneficial properties of steroids are offset partly by side effects, including atrogin-mediated muscle wasting bone fragility, obesity, and short stature (Schara et al., 2001).

Lazaroid Δ-9,11 analogs were developed originally as nonglucocorticoid steroids with effects on cell membranes and tested clinically for neuroprotection by the inhibition of lipid peroxidation (Taylor et al., 1996; Bracken et al., 1997; Kavanagh and Kam, 2001). More recent studies of lazaroids in muscle found the inhibition of calcium release in C2C12 muscle cells (Passaquin et al., 1998) and the attenuation of ischemia/reperfusion injury (Campo et al., 1997). Lazaroids have been found to protect against acute inflammation (endotoxin-induced shock) through the inhibition of inducible nitric-oxide synthase (Altavilla et al., 1999), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (Altavilla et al., 1998), and NF-κB (Fukuma et al., 1999). A Δ-9,11 analog without the large polar 21-amino group has been developed as an anti-neovascularization agent in macular degeneration (anecortave) (Clark, 2007) and more recently investigated for a similar effect in retinoblastoma (Bajenaru et al., 2010). In this article, we investigated a Δ-9,11 analog (anecortave; prodrug), as well as its active metabolite [anecortave desacetate (VBP1)], as a dissociative steroid.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

C57BL/6, SJL/J (dysferlin deficient), and C57BL/10ScSn-Dmdmdx/J (mdx) (dystrophin deficient) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). GR(dim/dim) mice (Reichardt et al., 1998) were obtained from Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany). All of the animal experiments were conducted in accordance with our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines under approved protocols.

Synthesis of Δ-9,11 Analogs.

Analogs were synthesized by Bridge Organics (Kalamazoo, MI) (Supplemental Fig. 1). Anecortave is the prodrug for VBP1.

NF-κB Inhibition Assay.

The in vitro drug screening assay for NF-κB inhibition in C2C12 cells was done as described previously (Baudy et al., 2009). To measure the ablation of NF-κB effects by the addition of a GR antagonist, reporter cells were pretreated for 1 h with the drug at a constant concentration and 17β-hydroxy-11β-[4-dimethylamino phenyl]-17α-[1-propynyl]estra-4,9-dien-3-one (RU-486) at increasing concentrations (1 nM to 10 μM). After the pretreatment, cells were stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) and assayed for luciferase activity 3 h later.

For studies using GR(dim/dim) mice, splenocytes were isolated from GR(dim/dim) and C57BL/6 mice. Splenocytes were treated with prednisolone (10 μm), anecortave (10 μM), or vehicle [dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] for 24 h. After the treatment, cells were stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for an additional 24 h. A murine NF-κB-regulated cDNA plate array (Signosis, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) was used to monitor gene expression.

Nuclear Translocation Assays.

Translocation assays were performed by DiscoveRx (Fremont, CA) using GR, mineralocorticoid receptor (MR), and androgen receptor (AR) Nuclear Translocation PathHunter cells (DiscoveRx).

Immunofluorescence.

A549 cells were incubated with the drug for 24 h in serum-free media, fixed using formaldehyde, and then processed with primary antibody (rabbit anti-GR; 1:50; GGR H-300; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit IgG1:100 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole were used for visualization on an LSM 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY).

GRE Transcription Assay.

HEK293 cells stably transfected with a luciferase reporter construct regulated under a GRE (Panomics, Fremont, CA) were grown according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were treated with drugs for 6 h at 37°C, and luciferase activity was measured (Promega, Madison, WI) using a Centro LB 960 luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany).

Myotube Microarrays.

H-2K myoblasts were obtained as described previously (Morgan et al., 1994; Harris et al., 1999). Conditionally, immortalized wild-type and mdx H-2K myoblast cell lines underwent differentiation to myotubes for 5 days and were exposed to prednisolone, anecortave, or DMSO vehicle for 4 h. RNA was isolated and analyzed on Affymetrix 430a 2.0 microarrays. Probe set signals were derived using the PLIER probe set algorithm. Thresholds used for the comparisons of drug-treated versus vehicle-treated were p value ≤0.01, fold change ≥1.2.

A549 Gene Transcription Assay.

A549 cells were grown to confluence in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal calf serum and exposed to prednisolone (1, 10, or 100 μM), anecortave (1, 10, or 100 μM), or vehicle control (DMSO) for 4 h at 37°C and for 24 h at 37°C. Real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed for FKBP5, GILZ, CCL2, and MKP-1 mRNAs, and 18S ribosomal RNA (housekeeping control) using TaqMan primers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Receptor Binding Assays.

GR binding assays were performed by two methods. Rat liver assays were performed by the State University of New York at Buffalo using methods published previously (Almon et al., 2008). Competitive binding assays were performed by Caliper Life Sciences (Hopkinton, MA), using radiolabeled 3H ligands and partially purified full-length human receptors expressed from recombinant baculovirus-infected insect cells.

Preclinical Trials.

In a short-term trial, prednisolone (1 mg/kg) and anecortave (5 mg/kg) were administered orally to 8-week-old female mdx mice daily via syrup drops for 3 weeks. The visualization of inflammation in vivo using the noninvasive imaging of cathepsin B caged near-infrared substrate ProSense 680 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) was done as described previously (Baudy et al., 2011). Membrane permeability was assessed using Cy5.5-labeled 10-kDa dextran beads injected intraperitoneally (150 μl/mouse). The forelimbs and hindlimbs were scanned using the eXplore Optix (GE Medical Systems, London, ON, Canada) optical scanner 24 h after injection and then quantified using Optiview software to calculate the total number of photon counts per square millimeter of scanned area.

For the 4-month trials, 8-week-old female mdx mice (n = 24, 8 per group) and 12-week-old SJL mice (n = 24, 8 per group) were separated into untreated, anecortave-treated, and prednisolone-treated groups. Drugs were administered to the treated mice via food for 4 months at a dose of 40 mg/kg anecortave and 5 mg/kg prednisolone. Evaluation of function, behavior, and histology using hematoxylin and eosin of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded muscle was performed as described previously (Spurney et al., 2009). Force measurements were conducted on the extensor digitorum longus muscle of the right hindlimb of the mdx mouse as described previously (Spurney et al., 2011).

Results

Δ-9,11 Analogs Show Retention of NF-κB Transrepression Activities.

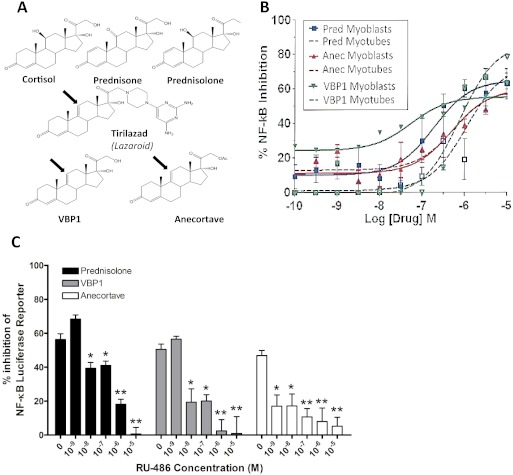

To determine whether Δ-9,11 analogs retained NF-κB inhibitory activity, we used a TNF-α-induced NF-κB luciferase construct stably transfected in C2C12 cells and studied drug effects on both undifferentiated myoblasts and multinucleated myotubes (Baudy et al., 2009). We synthesized anecortave, and the 21-hydroxy desacetate form, VBP1 (Fig. 1; Supplemental Fig. 1). Δ-9,11 Analogs showed NF-κB inhibitory activity in both cell differentiation stages at potencies comparable with that of prednisolone (Fig. 1B). The transrepression activities of prednisolone, anecortave, and VBP1 were blocked by increasing the concentrations of the receptor antagonist RU-486, suggesting that the NF-κB inhibitory activity of all three compounds is mediated by GR (Fig. 1C). RU-486 also antagonizes the progesterone receptor; however, we found no detectable binding of anecortave or VBP1 with progesterone receptor over a broad concentration range (see below).

Fig. 1.

Δ-9,11 Glucocorticoid analogs retain transrepression activities. A, the Δ-9,11 double bond dissociates the transactivational activities of traditional steroids (VBP1, anecortave) (arrow). Lazaroids share the Δ-9,11 double bond but have larger moieties designed for membrane integration. B, Δ-9,11 analogs show potent inhibition of TNF-α-induced NF-κB activity, similar to that seen by prednisolone. Shown is a luciferase reporter assay in C2C12 cells. C, the inhibition of TNF-α-induced NF-κB activity is blocked by increasing concentrations of the GR antagonist RU-486, showing GR dependence of NF-κB inhibition (one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett's multiple comparison test: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). Mean ± S.E.M. values are representative data from three independent experiments performed in triplicate and are expressed as the percentage of reporter inhibition compared with no-drug controls.

To determine whether Δ-9,11 analogs induced nuclear translocation of GR, we studied dexamethasone and the two analogs using a β-galactosidase chemiluminescence binding partner assay in a CHO cell line. Both Δ-9,11 analogs induced nuclear translocation at approximately half the levels induced by dexamethasone (Fig. 2A). In addition, immunostaining of A549 cells after the incubation with VBP1 or dexamethasone for 30 min showed nuclear translocation of GR (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Δ-9,11 Analogs induce GR translocation from the cytoplasm to nucleus. A, CHO-K1 cell line expressing β-galactosidase fragments on both GRs and a nuclear steroid coactivator peptide shows nuclear translocation induced by both glucocorticoids and Δ-9,11 analogs. B, both dexamethasone and VBP1 induce nuclear translocation of GR in A549 cells. Cells were stained for GR (red) and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue) for nuclear reference. A merge of the two colors is represented in the right column. Cells before exposure are shown in the top row.

Δ-9,11 Analogs Show the Loss of GRE-Mediated Transactivation Activities.

The ability of the Δ-9,11 analogs to mediate transcriptional activity using GREs was studied by measuring the response of a HEK293 cell line with GRE consensus sites coupled to a luciferase reporter. Prednisolone strongly induced GRE-mediated luciferase expression in a dose-dependent manner, whereas Δ-9,11 analogs showed no activity at 200 times prednisolone concentrations (Fig. 3A). These data suggested that Δ-9,11 analogs lack transactivation (GRE-mediated transcriptional) properties.

Fig. 3.

Δ-9,11 Analogs show the loss of downstream GRE-mediated transactivation. A, a cell-based reporter assay with GRE promoter elements fused to luciferase shows induction by prednisolone but not anecortave, which is consistent with the loss of GRE-dependent transcription by Δ-9,11analogs. B, wild-type (WT) (n = 3) and dystrophin-deficient (mdx) (n = 3) H-2K myotubes were exposed to 10 μM prednisolone or anecortave for 4 h. mRNA expression profiles were generated as described under Materials and Methods and analyzed. Prednisolone induced a strong transcriptional response involving 148 transcripts coordinately regulated in WT and mdx myotubes (red = increased expression, black = no change, green = decreased expression) relative to vehicle-only controls (DMSO) (p < 0.01 independently for WT and mdx). The Δ-9,11 analog failed to induce this transcriptional pattern, appearing more similar to vehicle-only control myotubes for both wild-type and mdx. Selection of these genes was by statistical methods; however, the heat map does not represent statistical significance.

To more broadly test global transcriptional responses to prednisolone and Δ-9,11 analogs, wild-type and dystrophin-deficient mdx H-2K myotubes were treated with drugs followed by mRNA profiling using Affymetrix microarrays (Fig. 3B). We have shown previously that substantial transcriptional responses to corticosteroids occur in muscle approximately 4 to 8 h after a bolus of the drug in vivo (Almon et al., 2007; Yao et al., 2008) and selected the 4-h time point to enrich for direct transcriptional targets of ligand/receptor complexes. A total of 148 mRNA transcripts modulated by 10 μM prednisolone at 4 h in both wild-type and mdx cultures were seen (p < 0.01 and fold-change >1.2 in both experiments), with 75% transcriptionally activated by prednisolone (red color) and 25% transcriptionally repressed (green color) (Fig. 3B). The anecortave-treated cultures showed little overlap with prednisolone and instead appeared more similar to control (DMSO vehicle)-treated cultures.

The mRNA profiles were queried for molecular networks associated with GR (NRC31) (Supplemental Fig. 2A), and this showed prednisolone to cause the expected negative transcriptional regulation of GR (Burnstein et al., 1991), as well as the induction of a key muscle atrophy transcript, FOXO (Reed et al., 2012) (Supplemental Fig. 2, A and B). Comparing this to anecortave-regulated transcripts, there was little evidence of a shared transcriptional response with prednisolone, with no down-regulation of GR or transcriptional activation of FOXO1. In a different nonmuscle assay, A549 cells treated with prednisolone induced the expected transcriptional up-regulation of FKBP5, GILZ, and MKP-1 (Chivers et al., 2006), whereas exposure to Δ-9,11 analogs did not alter the expression of these target genes (Supplemental Fig. 2C). All of the data were consistent with the loss of GRE-mediated transcriptional response by Δ-9,11 analogs.

Δ-9,11 Analogs Mediate Transrepression as Ligand/GR Monomers.

To test whether GR-mediated NF-κB inhibition was a dimer- or monomer-mediated event, we used GR(dim/dim) mice transgenic for a GR gene containing a point mutation preventing dimerization (Reichardt et al., 2001). Splenocytes were isolated from GR(dim/dim) and wild-type mice, pretreated with 10 μM anecortave or prednisolone, and then tested for the inhibition of TNF-α induced NF-κB transcriptional targets using a mouse NF-κB-regulated cDNA array. We found that both prednisolone and anecortave inhibited TNF-α-induced targets efficiently in GR(dim/dim) mice but less so in wild-type mice. In addition, some genes (IRF1, FASL, IFNB1, COX2, IFNγ, and IL1α) were inhibited more strongly by anecortave than by prednisolone in wild-type splenocytes but not in GR(dim/dim) mice (Supplemental Table 1). This suggested that the NF-κB inhibitory activity was mediated by GR/ligand monomers.

Δ-9,11 Glucocorticoid Analogs Show Differential Cross-Reactivity with Nuclear Hormone Receptors.

Competitive binding assays were carried out for Δ-9,11 analogs compared with known high-affinity ligands for the GR, MR, AR, and estrogen and progesterone receptors (Supplemental Fig. 3; Supplemental Table 2). VBP1 showed binding to GR at approximately 50-fold reduced affinity (triamcinolone IC50 = 1.34 × 10−9; VBP1 IC50 = 6.53 × 10−8). Neither anecortave nor VBP1 showed any detectable binding to the estrogen or progesterone receptors (Supplemental Fig. 3). For MR, binding affinity varied significantly between the different Δ-9,11 glucocorticoid analogs—VBP1 showed 11-fold higher affinity than spironolactone, whereas anecortave had a 5-fold lower binding affinity (Supplemental Fig. 3; Supplemental Table 2). For AR, anecortave and VBP1 showed >100-fold reduced affinity compared with methyltrienolone. In contrast to GR, the Δ-9,11 analogs did not induce the nuclear translocation of MR or AR (E.K.M Reeves, unpublished observations).

Given the relatively high affinities of VBP1 and anecortave for MR and the known anti-inflammatory activities of MR complexes (Yagi and Sata, 2011), we tested the abilities of prednisolone and anecortave to induce MR gene targets in normal and mdx myotubes. The mRNA profiles used to analyze GR targets were queried for known MR gene targets, and the data were analyzed statistically, visualized by heat maps, and tested for MR-associated networks using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA). We found no evidence of the regulation of MR targets by either prednisolone or anecortave (Z. Wang and E. P. Hoffman, unpublished observations).

In Vivo Tests of Efficacy and Side Effects in Murine Models of Muscular Dystrophy.

We compared anecortave to prednisolone in three preclinical trials using mouse muscular dystrophy models: one short-term, 3-week daily oral bolus dosing study to assess effects on muscle inflammation in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice and two longer-term, 4-month studies with administration in food in both dystrophin-deficient mdx and dysferlin-deficient SJL mice.

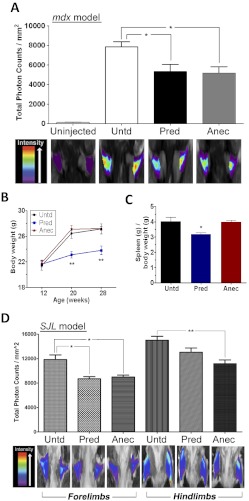

In the 3-week acute trial, a daily oral bolus was given in syrup (1 mg/kg per day prednisolone or 5 mg/kg per day anecortave). A significant reduction of cathepsin B activity, an indicator of muscle inflammation and regeneration, in the forelimbs of both prednisone- and anecortave-treated mdx mice was observed in comparison to untreated mdx mice as shown by the caged near-infrared cathepsin B substrate Prosense 680 (Fig. 4A) (Baudy et al., 2011).

Fig. 4.

A Δ-9,11 analog improves muscular dystrophy in both mdx and SJL models, with no evidence of prednisolone-associated side effects. A, cathepsin B optical imaging of the forelimbs was performed on mdx mice that were administered daily prednisone or anecortave syrup for 3 weeks. Both drugs showed significant reductions in cathepsin B levels, an enzyme directly relaying levels of muscle inflammation and regeneration (illustrated as a photon intensity map; purple = lowest photon counts, red = highest) (Student's unpaired t test comparing untreated to each drug-treated group; *, p < 0.05). B and C, a 4-month trial was conducted in mdx mice receiving prednisolone or anecortave in food. Prednisone-treated mice, but not Δ-9,11 analog-treated mice, showed the expected side effects of loss of body weight (B) and spleen weight (C). (One-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni multiple comparison post hoc test: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.) D, SJL (dysferlin-deficient) mice were treated with prednisolone (5 mg/kg) or anecortave (40 mg/kg) for 4 months in food. A 10-kDa dextran coupled to Cy5.5 dye was injected intraperitoneally (150 μl per mouse), and the inclusion of the dye into muscle in vivo was assessed 24 h after injection by live animal optical scanning. Anecortave-treated muscle showed improved resistance to dye inclusion, suggesting partial rescue of plasma membrane defects (Student's unpaired t test comparing untreated to each drug-treated group; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01).

In the 4-month trials (separate mdx and SJL trials), we used chronic dosing in food at higher levels (mouse chow prepared with ∼5 mg/kg per day prednisolone or ∼40 mg/kg per day anecortave) (approaching the maximum tolerated doses for both drugs). At the study end point, prednisolone-treated mice in the mdx mouse trial showed significant losses of both body weight and spleen weight (Fig. 4, B and C), which is consistent with previous reports of deleterious side effects in rats (Orzechowski et al., 2002), whereas anecortave at higher doses showed none of these side effects. Likewise, in the dysferlin-deficient (SJL) trial, prednisolone, but not anecortave, induced a significant loss of spleen weight [control, 6.09 ± 0.34 g; prednisolone, 4.11 ± 0.23 g (*, p < 0.05); anecortave, 6.52 ± 0.59 g]. In the SJL trial, the body weights of prednisolone mice were similar to those of controls, whereas anecortave mice significantly increased body weight (control, 19.62 ± 0.62 g; prednisolone, 20.16 ± 0.41 g; anecortave, 21.83 ± 0.68 g*). In the SJL trial, prednisolone induced significantly increased heart weight normalized to body weight, whereas anecortave did not induce this off-target effect (control, 4.98 ± 0.13 mg; prednisolone, 6.29 ± 0.27 mg*; anecortave, 4.84 ± 0.20 mg).

In both mdx and SJL trials, multiple histological and functional end points reflective of drug efficacy showed improvement with both anecortave and prednisolone, and often greater efficacy was seen with anecortave. In the mdx trial, inflammatory infiltrates decreased, whereas muscle force increased significantly with anecortave (Supplemental Fig. 4). In the SJL trial, forelimb grip strength increased significantly in anecortave mice (control, 95 ± 3 g; prednisolone, 97 ± 1 g; anecortave, 108 ± 3 g*), as did performance on a rotorod motor coordination test (control, 103.6 ± 4.76 s; prednisolone, 121.1 ± 4.04 s; anecortave, 137.9 ± 17.64 s*). Histologically, there were significantly fewer central nucleated fibers in anecortave-treated mice, indicating protection from myofiber degeneration (control, 154.3 ± 12.2 central nuclei per field; prednisolone, 146.7 ± 18.4 central nuclei per field; anecortave, 111.8 ± 5.2* central nuclei per field). Assessments of myofiber membrane integrity using optical imaging of muscle after intraperitoneal injection of Cy5.5-labeled 10-kDa dextran beads showed significant reductions in myofiber dye uptake in both prednisolone- and anecortave-treated mouse forelimbs and hindlimbs (Fig. 4D), although the effect in hindlimbs was more pronounced for anecortave relative to that for prednisolone.

Discussion

Existing models of glucocorticoid anti-inflammatory activities involve ligand binding to the GR cytoplasmic receptor. Previous reports using transgenic mice harboring GR mutations that prevent dimerization of GR [GR(dim/dim)] have shown that these mice retain the anti-inflammatory response to pharmacological glucocorticoids but do not transactivate genes with GRE cis-elements (Reichardt et al., 1998). These data suggest that neither dimerization nor GRE-mediated transcriptional activation (transactivation properties) are required for the efficacy of glucocorticoids. The GR(dim/dim) data set the stage for the efforts to develop and test dissociative steroidal compounds that bind and translocate GR but do not modulate GRE-mediated transcription.

In this article, we show that a Δ-9,11 analog of glucocorticoids [anecortave (prodrug), VBP1] is a dissociative steroid—it translocates GR and shows anti-inflammatory activities yet lacks GRE-mediated transcription. To our knowledge, we present the first data testing the transrepression and transactivation activities of Δ-9,11 analogs. We found that the Δ-9,11 analog was able to bind GR (albeit at a lower affinity compared with classic ligands) and retained activity in inducing translocation of GR from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (Fig. 2) but did not induce GRE-mediated transcription. It also retained potent NF-κB inhibitory activities, at levels similar to standard GR ligands, and this transrepression activity was blocked by RU-486, showing a requirement for GR (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, this NF-κB inhibitory activity still was retained in cells unable to form GR dimers and undergo GRE-mediated transactivation [GR(dim/dim) transgenic mice], suggesting that transpression was mediated by ligand/GR monomers. The Δ-9,11 analog showed anti-inflammatory activity in vivo in acute (4 weeks) and long-term (4 month) studies in two animal models of muscular dystrophy (dystrophin-deficient mdx and dysferlin-deficient SJL). Efficacy of the Δ-9,11 analog using multiple histological and functional outcome measures was equal to or greater than that of prednisolone, although dosing regimens varied, and more extensive dose optimization is required (Fig. 4).

Many inflammatory genes are regulated by both direct GR/GRE action on their gene promoters as well as NF-κB DNA binding. Indeed, part of the complexity of GR action on anti-inflammatory genes includes GR/NF-κB antagonism at the level of gene promoters, leading to the steric occlusion of NF-κB DNA binding by GR (Novac et al., 2006). Given our model of the dissociative activity of Δ-9,11 analogs, we would expect NF-κB DNA binding to be retained but GRE-mediated DNA binding to be lost, thus leading to differential regulation of the expression of genes that have both GREs and NF-κB promoter elements (IRF1, FASL, IFNB1, COX2, and IFNγ) versus those that have only NF-κB promoter elements (IL-6, NOS2, MMP1, IL-9, TNFα, TNFR, MYC, and IL-1α) (Supplemental Table 1). Consistent with this model, transcripts containing only NF-κB promoter elements were inhibited strongly by both prednisolone and anecortave in both wild-type and GR(dim/dim) mice. In contrast, inflammatory transcripts containing both GRE and NF-κB promoter elements were inhibited more strongly by anecortave compared with prednisolone in wild-type mice (85.5% inhibition by anecortave; 50.8% by prednisolone), and this differential activity was lost in the GR(dim/dim) mice (96% inhibition for both prednisolone and anecortave). These data suggest that Δ-9,11 analogs may prove to be more effective anti-inflammatory drugs than traditional glucocorticoids, because they remove some or all of the steric occlusion between GRE and NF-κB promoter elements.

The dissociation of transrepression from transactivation suggests that Δ-9,11 analogs have the potential for replacing current glucocorticoid drugs. Our data suggest that the analogs bind GR and induce nuclear translocation and transrepressive activities independent of dimer formation but do not permit binding to GRE elements in gene promoters (transactivation). We suggest that future optimized lead compounds could be selected based upon GR translocation and NF-κB inhibition, with reduced cross-reaction to other nuclear hormone receptors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Günther Schütz of Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (German Cancer Research Center) for his gift of GR(dim/dim) mice.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [Grant U54-HD053177] (Wellstone Muscular Dystrophy Research Center); the National Institutes of Health Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [Grant 5R24-HD050846] (National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research); the National Institutes of Health Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [Grant 1P30-HD40677] (Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center); the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases [Grant R01-AR050478]; the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grant R01-HL033152]; the Foundation to Eradicate Duchenne; the Muscular Dystrophy Association Venture Philanthropy; the Myositis Association; and the U.S. Department of Defense [Grants W81XWH-05-1-0616, W81XWH-04-01-0081].

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

The online version of this article (available at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor-κB

- AR

- androgen receptor

- FOXO

- Forkhead box O

- GR

- glucocorticoid receptor

- GRE

- glucocorticoid response element

- MR

- mineralocorticoid receptor

- TNF-α

- tumor necrosis factor-α

- VBP1

- anecortave desacetate

- RU-486

- 17β-hydroxy-11β-[4-dimethylamino phenyl]-17α-[1-propynyl]estra-4,9-dien-3-one

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney.

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Baudy, Reeves, Damsker, Heier, McCall, Rose, Nagaraju, and Hoffman.

Conducted experiments: Baudy, Reeves, Damsker, Heier, Garvin, Dillingham, Rayavarapu, Wang, Vander Meulen, Sali, Jahnke, Duguez, and DuBois.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: McCall.

Performed data analysis: Baudy, Reeves, Damsker, and Heier.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Baudy, Reeves, Damsker, Heier, McCall, Rose, Nagaraju, and Hoffman.

References

- Almon RR, DuBois DC, Yao Z, Hoffman EP, Ghimbovschi S, Jusko WJ. (2007) Microarray analysis of the temporal response of skeletal muscle to methylprednisolone: comparative analysis of two dosing regimens. Physiol Genomics 30:282–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almon RR, Yang E, Lai W, Androulakis IP, Ghimbovschi S, Hoffman EP, Jusko WJ, Dubois DC. (2008) Relationships between circadian rhythms and modulation of gene expression by glucocorticoids in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295:R1031–R1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altavilla D, Squadrito F, Campo GM, Squadrito G, Arlotta M, Urna G, Sardella A, Quartarone C, Saitta A, Caputi AP. (1999) The lazaroid, U-74389G, inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase activity, reverses vascular failure and protects against endotoxin shock. Eur J Pharmacol 369:49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altavilla D, Squadrito F, Serrano M, Campo GM, Squadrito G, Arlotta M, Urna G, Sardella A, Saitta A, Caputi AP. (1998) Inhibition of tumour necrosis factor and reversal of endotoxin-induced shock by U-83836E, a ‘second generation’ lazaroid in rats. Br J Pharmacol 124:1293–1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach JR, Martinez D, Saulat B. (2010) Duchenne muscular dystrophy: the effect of glucocorticoids on ventilator use and ambulation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 89:620–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajenaru ML, Piña Y, Murray TG, Cebulla CM, Feuer W, Jockovich ME, Marin Castaño ME. (2010) Gelatinase expression in retinoblastoma: modulation of LH(BETA)T(AG) retinal tumor development by anecortave acetate. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51:2860–2864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baschant U, Tuckermann J. (2010) The role of the glucocorticoid receptor in inflammation and immunity. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 120:69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudy AR, Sali A, Jordan S, Kesari A, Johnston HK, Hoffman EP, Nagaraju K. (2011) Non-invasive optical imaging of muscle pathology in mdx mice using cathepsin caged near-infrared imaging. Mol Imaging Biol 13:462–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudy AR, Saxena N, Gordish H, Hoffman EP, Nagaraju K. (2009) A robust in vitro screening assay to identify NF-kappaB inhibitors for inflammatory muscle diseases. Int Immunopharmacol 9:1209–1214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Holford TR, Leo-Summers L, Aldrich EF, Fazl M, Fehlings M, Herr DL, Hitchon PW, Marshall LF, et al. (1997) Administration of methylprednisolone for 24 or 48 hours or tirilazad mesylate for 48 hours in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury. Results of the Third National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Randomized Controlled Trial. National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. JAMA 277:1597–1604 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstein KL, Bellingham DL, Jewell CM, Powell-Oliver FE, Cidlowski JA. (1991) Autoregulation of glucocorticoid receptor gene expression. Steroids 56:52–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo GM, Squadrito F, Campo S, Altavilla D, Avenoso A, Ferlito M, Squadrito G, Caputi AP. (1997) Antioxidant activity of U-83836E, a second generation lazaroid, during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Free Radic Res 27:577–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivers JE, Gong W, King EM, Seybold J, Mak JC, Donnelly LE, Holden NS, Newton R. (2006) Analysis of the dissociated steroid RU24858 does not exclude a role for inducible genes in the anti-inflammatory actions of glucocorticoids. Mol Pharmacol 70:2084–2095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos GA, Kattah JC, Beck RW, Cleary PA. (1993) Side effects of glucocorticoid treatment. Experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. JAMA 269:2110–2112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AF. (2007) Mechanism of action of the angiostatic cortisene anecortave acetate. Surv Ophthalmol 52(Suppl 1):S26–S34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bosscher K. (2010) Selective glucocorticoid receptor modulators. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 120:96–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovanni S, Molon A, Broccolini A, Melcon G, Mirabella M, Hoffman EP, Servidei S. (2004) Constitutive activation of MAPK cascade in acute quadriplegic myopathy. Ann Neurol 55:195–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostert A, Heinzel T. (2004) Negative glucocorticoid receptor response elements and their role in glucocorticoid action. Curr Pharm Des 10:2807–2816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escolar DM, Hache LP, Clemens PR, Cnaan A, McDonald CM, Viswanathan V, Kornberg AJ, Bertorini TE, Nevo Y, Lotze T, et al. (2011) Randomized, blinded trial of weekend vs daily prednisone in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 77:444–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuma K, Marubayashi S, Okada K, Yamada K, Kimura A, Dohi K. (1999) Effect of lazaroid U-74389G and methylprednisolone on endotoxin-induced shock in mice. Surgery 125:421–430 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JM, Morgan JE, Rosenblatt JD, Peckham M, Edwards YH, Partridge TA, Porter AC. (1999) Forced MyHCIIB expression following targeted genetic manipulation of conditionally immortalized muscle precursor cells. Exp Cell Res 253:523–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier SG. (2007) Diamonds are forever: the cortisone legacy. J Endocrinol 195:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein MR, Abu-Dief EE, Kamel NF, Mostafa MG. (2010) Steroid therapy is associated with decreased numbers of dendritic cells and fibroblasts, and increased numbers of satellite cells, in the dystrophic skeletal muscle. J Clin Pathol 63:805–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh RJ, Kam PC. (2001) Lazaroids: efficacy and mechanism of action of the 21-aminosteroids in neuroprotection. Br J Anaesth 86:110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JE, Beauchamp JR, Pagel CN, Peckham M, Ataliotis P, Jat PS, Noble MD, Farmer K, Partridge TA. (1994) Myogenic cell lines derived from transgenic mice carrying a thermolabile T antigen: a model system for the derivation of tissue-specific and mutation-specific cell lines. Dev Biol 162:486–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R, Holden NS. (2007) Separating transrepression and transactivation: a distressing divorce for the glucocorticoid receptor? Mol Pharmacol 72:799–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novac N, Baus D, Dostert A, Heinzel T. (2006) Competition between glucocorticoid receptor and NFkappaB for control of the human FasL promoter. FASEB J 20:1074–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orzechowski A, Ostaszewski P, Wilczak J, Jank M, Bałasińska B, Wareski P, Fuller J., Jr (2002) Rats with a glucocorticoid-induced catabolic state show symptoms of oxidative stress and spleen atrophy: the effects of age and recovery. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med 49:256–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passaquin AC, Lhote P, Rüegg UT. (1998) Calcium influx inhibition by steroids and analogs in C2C12 skeletal muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol 124:1751–1759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthucheary Z, Harridge S, Hart N. (2010) Skeletal muscle dysfunction in critical care: wasting, weakness, and rehabilitation strategies. Crit Care Med 38:S676–S682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed SA, Sandesara PB, Senf SM, Judge AR. (2012) Inhibition of FoxO transcriptional activity prevents muscle fiber atrophy during cachexia and induces hypertrophy. FASEB J 26:987–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt HM, Kaestner KH, Tuckermann J, Kretz O, Wessely O, Bock R, Gass P, Schmid W, Herrlich P, Angel P, et al. (1998) DNA binding of the glucocorticoid receptor is not essential for survival. Cell 93:531–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt HM, Tuckermann JP, Göttlicher M, Vujic M, Weih F, Angel P, Herrlich P, Schütz G. (2001) Repression of inflammatory responses in the absence of DNA binding by the glucocorticoid receptor. EMBO J 20:7168–7173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhen T, Cidlowski JA. (2005) Antiinflammatory action of glucocorticoids–new mechanisms for old drugs. N Engl J Med 353:1711–1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schara U, Mortier, Mortier W. (2001) Long-term steroid therapy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy-positive results versus side effects. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2:179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurney CF, Gordish-Dressman H, Guerron AD, Sali A, Pandey GS, Rawat R, Van Der Meulen JH, Cha HJ, Pistilli EE, Partridge TA, et al. (2009) Preclinical drug trials in the mdx mouse: assessment of reliable and sensitive outcome measures. Muscle Nerve 39:591–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurney CF, Sali A, Guerron AD, Iantorno M, Yu Q, Gordish-Dressman H, Rayavarapu S, van der Meulen J, Hoffman EP, Nagaraju K. (2011) Losartan decreases cardiac muscle fibrosis and improves cardiac function in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 16:87–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BM, Fleming WE, Benjamin CW, Wu Y, Mathews WR, Sun FF. (1996) The mechanism of cytoprotective action of lazaroids I: Inhibition of reactive oxygen species formation and lethal cell injury during periods of energy depletion. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 276:1224–1231 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi S, Sata M. (2011) Pre-clinical data on the role of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in reversing vascular inflammation. Eur Heart J Suppl 13 (Suppl B):B15–B20 [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z, Hoffman EP, Ghimbovschi S, Dubois DC, Almon RR, Jusko WJ. (2008) Mathematical modeling of corticosteroid pharmacogenomics in rat muscle following acute and chronic methylprednisolone dosing. Mol Pharm 5:328–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.