Abstract

Objective

Increased protein SUMOylation provides protection from cellular stress including oxidative stress, but the mechanisms involved are incompletely understood. The NADPH oxidases (Nox) are a primary source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress and thus our goal was to determine whether SUMO regulates NADPH oxidase activity.

Methods and Results

Increased expression of SUMO1 potently inhibited the activity of Nox1-5. In contrast, inhibition of endogenous SUMOylation with siRNA to SUMO1 or UBC9 or with the inhibitor, anacardic acid, increased ROS production from HEK-Nox5 cells, human vascular smooth muscle cells and neutrophils. The suppression of ROS production was unique to SUMO1, required a C-terminal di-glycine and the SUMO-specific conjugating enzyme, UBC9. SUMO1 did not modify intracellular calcium or Nox5 phosphorylation but reduced ROS output in an isolated enzyme assay suggesting direct effects of SUMOylation on enzyme activity. However, we could not detect the presence of SUMO1-conjugation on Nox5 using a variety of approaches. Moreover the mutation of over 17 predicted and conserved lysine residues on Nox5 did not alter the inhibitory actions of SUMO1.

Conclusion

Together, these results suggest that SUMO is an important regulatory mechanism that indirectly represses the production of reactive oxygen species to ameliorate cellular stress.

Control over protein function in eukaryotes can be achieved via covalent post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation, methylation, acetylation and ubiquitylation. The Small Ubiquitin-related MOdifier (SUMO) family of proteins is a more recently discovered post-translational modification1. There are four SUMO genes (SUMO1-4) which encode small proteins approximately 12kDa in size that are distantly related to ubiquitin (~20%). The attachment of SUMO to target proteins occurs in a manner analogous to ubiquitylation but utilizes distinct enzymes. The SUMO proteins are first cleaved at their C-terminus to expose a di-glycine, activated by E1 enzymes, transferred to the SUMO specific conjugating enzyme UBC9(E2) and then attached to lysine residues of substrate proteins via an E3 ligase2. Cellular stress arising from imbalances in osmolarity, temperature, genotoxic metabolites and in particular reactive oxygen species is a robust stimulus for protein SUMOylation3, 4. SUMOylation is widely regarded as a protective mechanism and loss of SUMO conjugation reduces cell and organism viability5, 6.

The overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and subsequent oxidative stress has been implicated in a number of pathological states including cardiovascular disease, cancer and inflammation7–9. The NADPH oxidases (Nox) are a major source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress in mammalian cells10. The Nox family consists of seven members Noxes 1-5 and Duoxes 1 and 2 and are employed in a number of important physiological roles including host defense, cellular signaling, synthesis of thyroid hormone and the formation of otoconia11. The Nox enzymes are transmembrane oxidoreductases that span the membrane six times, contain two centrally coordinated heme residues and C-terminal cytoplasmic regions for binding FAD and NADPH 12. The activity of Noxes 1-3 is tightly controlled by the binding of regulatory proteins such as p22 phox, p47phox, p67phox and the organizers NoxO1 and NoxA113,11. The mechanisms controlling the activity of Nox4 remain poorly understood and it is thought to constitutively produce hydrogen peroxide14. In contrast, the regulation of Nox5 is unique among the Nox isoforms in that it is calcium-dependent and does not require the presence of cytosolic subunits for superoxide production 15. ROS can alter the balance of signaling pathways by inactivating protein phosphatases16, modify protein structure and activity17 and react avidly with nitric oxide to reduce its biological effects18. Although we have gained considerable knowledge into the mechanisms controlling the activation of Nox enzymes, comparatively little is known about the mechanisms that limit or inhibit Nox activity and reduce ROS production.

Recent publications have intimated a close relationship between SUMOylation and reactive oxygen species. Cellular stresses such as heat shock, osmotic and high oxidative stress (H2O2) enhance SUMOylation3, 19. Elevated H2O2 production in diabetes increases the SUMOylation of ERK5 and promotes endothelial dysfunction20 and the ability of ROS to influence protein SUMOylation is concentration dependent21. However, despite evidence for the ability of ROS to modify protein SUMOylation, the ability of SUMO to modify ROS levels via the activity of the NADPH oxidases has not been established. Therefore the goal of the current study was to determine whether NADPH oxidase enzymes are regulated by protein SUMOylation and to establish a mechanism of action.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and Transfection

COS-7, human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells (HAVSMC) were cultured and transfected as described previously22, 23. HEK293 cells stably expressing Nox5 were transfected with control, SUMO1, and UBC9 siRNA (30nM, Ambion) using RNAImax (Invitrogen).

Measurement of reactive oxygen species

Cells were incubated at 37°C with 400μM L-012 (Wako) prior to the addition of agonists. Luminescence was quantified over time using a Lumistar Galaxy (BMG) luminometer. The specificity of L-012 for reactive oxygen species was confirmed by transfecting cells with a control plasmid such as GFP or lacZ or by co-incubation of a superoxide scavenger such as Tiron (5mM) see22.

Cell free activity assay

Cells were lysed in MOPS(30mM, pH 7.2) based buffer containing KCl(100mM), Triton(0.3%) and protease inhibitors. Detergent-resistant fractions were re-suspended in a PBS buffer containing, L012 (400μM), 1mM MgCl2, 100μM FAD and 26μM of Calcium chloride. After a brief period of equilibration, reduced NADPH was injected to a final concentration of 100μM and the production of reactive oxygen species was monitored over time.

Measurement of intracellular calcium

COS-7 cells were incubated in HBSS with 20mM HEPES and 2.5 mM probenecid. Fluo-4 AM (Invitrogen) was used at a final concentration of 4μM with 0.08% Pluronic F-127. Fluorescence was recorded at 485 nm (excitation) and 525nm (emission) using a BMG Polarstar Omega.

Detection of protein SUMOylation

Cells were lysed in 50mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 100mM NaF, 15mM Na4P2O7, 1mM Na3VO4, 150mM NaCl, 5mM EDTA, 15mM MgCl2, 1% NP-40, 1% SDS, protease inhibitors and 20mM NEM. For HIS-TAG purification, cells were lysed in 8M urea and incubated with Ni-NTA column (Pierce) O/N at 4°C with rocking. HIS-tagged proteins were eluted and immunoblotted for HA or SUMO1.

In vitro SUMO Conjugation Assays

Immunoprecipitated HA-Nox5 was incubated with 400nM SAE1/SAE2, 4μM UBC9, 15μM SUMO and ATP at 30°C for 2h (Enzo Life Sciences). Samples were resolved by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted for SUMO1.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using Instat software and were made using a two tailed student’s t-test or ANOVA with a post-hoc test where appropriate. Differences are considered significant at p-value<0.5.

Results

SUMO negatively regulates NADPH oxidase 5 (Nox5) activity

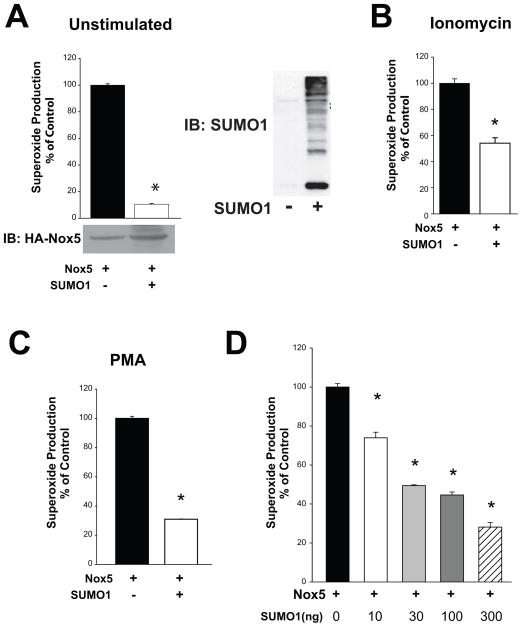

To determine whether SUMO can influence the activity of NADPH oxidases, SUMO1 and Nox5 cDNA were co-transfected in COS-7 cells and superoxide release quantified using L-012 luminescence. SUMO1 potently inhibited both basal (Figure 1A) and stimulated Nox5 activity in response to the calcium-mobilizing agent ionomycin (Figure 1B) and the PKC agonist, PMA (Figure 1C). SUMO1 inhibited Nox5 activity in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1D) suggesting that the ability to inhibit Nox5 is directly dependent on the amount of free SUMO1. Increased expression of SUMO1 (Figure 1A, right panel) did not decrease Nox5 expression.

Figure 1. SUMO1 inhibits basal and stimulated production of superoxide.

(A) COS-7 cells were co-transfected with cDNAs encoding Nox5 and either SUMO1 or a non-specific control gene (RFP) and basal/unstimulated superoxide production was monitored by L-012-mediated chemiluminescence. The relative expression of Nox5 and SUMO was confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-HA (lower panel) and anti-SUMO1 (right panel) (B-C) Superoxide production from COS-7 cells expressing Nox5 following challenge with ionomycin (1μM, B) or PMA (100nM, C). (D) Superoxide levels in COS-7 cells co-transfected with Nox5 and progressively higher amounts of SUMO1. Results are presented as mean +/− SEM, n=4–6. * p<0.05 versus control (absence of SUMO1).

Inhibition of ROS requires the active form of SUMO1 and the SUMO-specific conjugating enzyme UBC9 and is not limited to Nox5

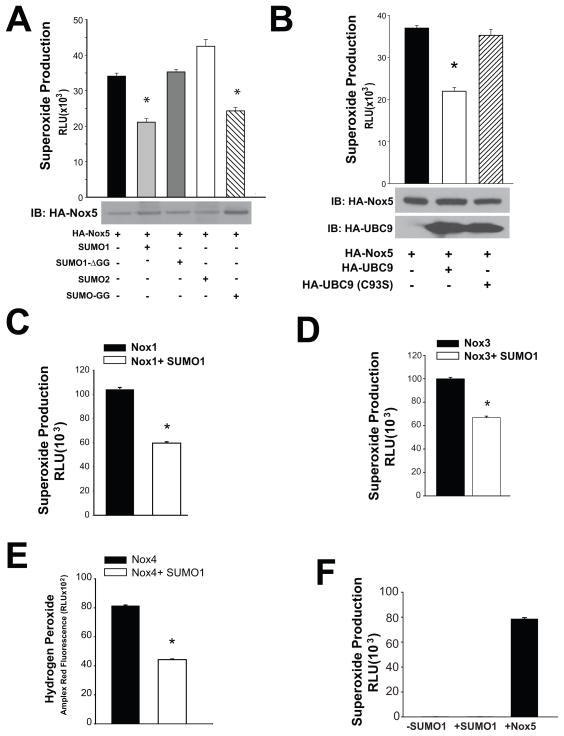

The first step in SUMOylation is mediated by C-terminal processing to reveal a di-glycine required for substrate conjugation. To determine whether conjugation is necessary for the suppression of ROS by SUMO1, we employed a SUMO1 construct that lacks the C-terminal diglycine motif (ΔGG). Loss of the C-terminal glycines, prevented the ability of SUMO1 to inhibit Nox5-dependent superoxide production (Figure 2A). In contrast, a form of SUMO1 lacking the C-terminal pro-peptide but containing the C-terminal diglycine motif (hydrolase-independent) was as effective as the wild-type SUMO1 indicating that hydrolysis of the C-terminal tail of SUMO1 is not a rate limiting step. Other isoforms of SUMO, SUMO-2 and the closely related SUMO-3 (data not shown) were unable to inhibit Nox5 activity (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Inhibition of ROS production by SUMO is dependent on the active forms of SUMO1 and UBC9 and is not specific to the Nox5 isoform.

(A) Superoxide release from COS-7 expressing Nox5 and either SUMO1, an inactive form of SUMO1 that lacks C-terminal diglycines (SUMOΔGG), SUMO2 and an active form of SUMO that does not require proteolysis of the C-terminal (SUMO-GG). Results are presented as mean +/− SEM, n=6. (B) Superoxide levels in COS-7 cells expressing Nox5 with and without the SUMO-specific conjugating enzyme, UBC-9 or an inactive form of UBC-9 (C93S). Results are presented as mean +/− SEM, n=6. * p<0.05 versus control. (C–D) Superoxide levels in COS-7 cells co-transfected with Nox1, NOXO1 and NOXA1, Nox3 with NOXO1 and NOXA1 both with and without SUMO1. (E) COS-7 cells were co-transfected with Nox4 with and without SUMO1 and the level of hydrogen peroxide was measured via the amplex red assay. (F) Superoxide release from COS-7 cells in the presence and absence of SUMO1 without a Nox enzyme versus cells transfected with Nox5 alone. Results are presented as mean +/− SEM, n=4–6. * p<0.05 versus control.

Following activation by E1 enzymes, SUMO is then transferred to the SUMO specific E2 conjugating enzyme, UBC9 which enables site specific isopeptide bond formation between SUMO and substrate proteins19. To test whether UBC9 is sufficient to promote Nox5 inhibition, we co-transfected Nox5 with active and inactive forms of UBC9 and measured superoxide production. Co-expression of UBC9 with Nox5 resulted in reduced Nox5 activity whereas a dominant negative lacking a critical catalytic cysteine residue (C93) was ineffective (Figure 2B).

To assess whether SUMO1 can modify the activity of other members of the Nox family, we co-transfected SUMO1 together with Nox1, 3 and 4 and measured ROS production. SUMO1 was an effective inhibitor of Nox1 (Figure 2C), Nox3 (Figure 2D) and Nox4 (Figure 2E). Importantly, in the absence of transfected Nox enzymes, there was no detectable ROS production from COS-7 cells and this was unaltered by the presence or absence of SUMO1 (Figure 2F).

Endogenous SUMO represses the activity of NAPDH oxidases

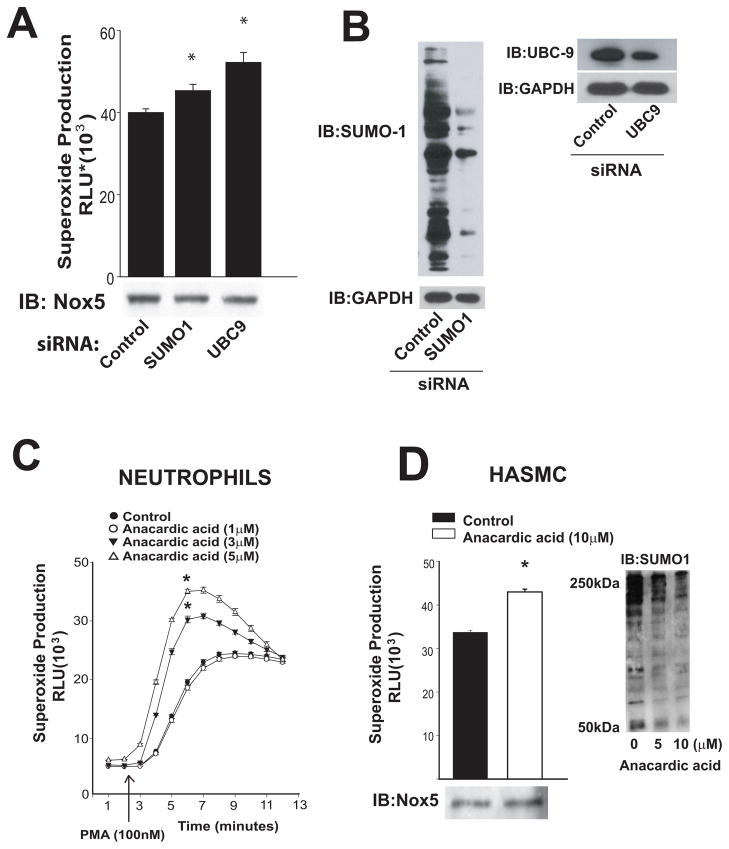

Our next goal was to establish the importance of endogenous SUMOylation as a regulator of Nox activity. To achieve this we suppressed the expression of SUMO1 and UBC9 in HEK293 cells stably expressing Nox5. Reduced expression of SUMO1 significantly increased Nox5 activity and superoxide levels were further increased by knockdown of UBC9 (Figure 3A–B). To assess whether endogenous SUMO is important for Nox activity in primary cells, we exposed human neutrophils (a source of Nox2) and human vascular smooth muscle cells (Nox5) to an inhibitor of SUMOylation, anacardic acid. Anacardic acid increased superoxide release from smooth muscle cells and dose-dependently increased superoxide from PMA-challenged neutrophils (Figure 3C–D). As shown in Figure 3D (right panel), exposure of VSMC to anacardic acid decreased the levels of SUMOylated proteins.

Figure 3. Endogenous SUMOylation restrains Nox activity.

(A) Superoxide release was measured from HEK293 cells stably expressing Nox5 following transfection of control, SUMO1 or UBC9 siRNA. (B) HEK293 lysates were immunoblotted for SUMO1 or UBC9 versus GAPDH. (C) PMA (100nM)- stimulated superoxide release from human neutrophils treated with vehicle or the inhibitor of SUMOylation, anacardic acid. (D) Superoxide release from human vascular smooth muscle cells in the presence and absence of anacardic acid (10μM). Relative expression of Nox5 (lower panel) or SUMO1(right panel) is shown via immunoblot. Results are presented as mean +/− SEM, n=4–6. * p<0.05 versus control.

SUMO directly influences NADPH oxidase activity and does not modify levels of intracellular calcium, phosphorylation or protein stability of Nox5

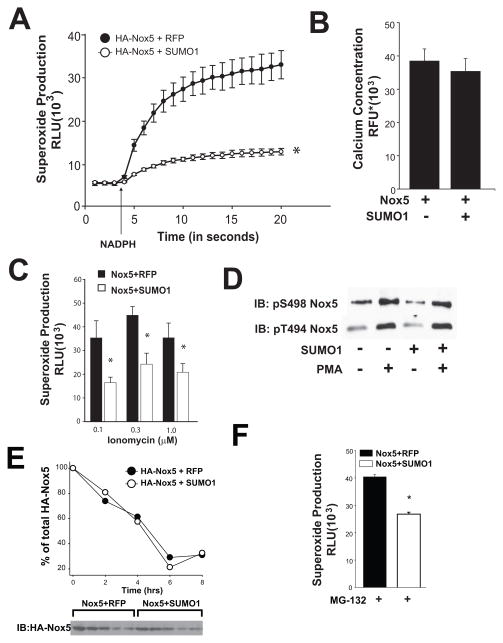

We next determined whether SUMO1 directly influences Nox5 activity or secondary events important for activation of Nox5 such as co-factor availability or calcium levels. In an isolated Nox5 activity assay in the presence of supplemental calcium, and co-factors (NADPH and FAD)22 prior expression of SUMO1 strongly suppressed Nox5 activity (Figure 4A). SUMO1 did not influence the level of calcium in COS-7 cells (Figure 4B) and saturation of intracellular calcium with increasing concentrations of calcium ionophore failed to overcome SUMO1 inhibition (Figure 4C). A key post-translational modification that regulates the sensitivity of Nox5 to calcium is via the increased phosphorylation of T494 and S49822. SUMO1 did not modify PMA-stimulated Nox5 phosphorylation at T494 and S498 (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Mechanisms underlying the inhibition of Nox5 by SUMO1.

(A) Superoxide release in an isolated Nox5 activity assay using extracts of COS-7 cells expressing Nox5 with or without SUMO1. The arrow indicates injection of NADPH (100μM). (B) intracellular calcium levels were monitored in intact COS-7 cells expressing Nox5 and SUMO1 using Fluo4-NW and changes in fluorescence intensity was monitored with a 485/10 excitation and a 520/10 emission filter. (C) High-dose ionomycin-stimulation cannot supersede SUMO1-dependent inhibition of superoxide release in cells expressing Nox5. Results are presented as mean +/− SEM, n=4–6. * p<0.05 versus control. (D) SUMO1 does not modify the phosphorylation of Nox5. Cell lysates from COS-7 cells expressing Nox5 with or without SUMO1 were immunoblotted with anti-phospho T494 and S498. (E-F) SUMO1 does not modify the expression or degradation of Nox5. COS-7 cells were co-transfected with Nox5 and control (RFP) or SUMO1 cDNA, treated with cycloheximide (50μM) and cell lysates harvested at the indicated times and immunoblotted for HA-Nox5. (F) Superoxide release from COS-7 cells co-expressing Nox5 with and without SUMO1 in the presence of the proteosome inhibitor, MG132 (10μM). Results are presented as mean +/− SEM, n=6. * p<0.05 versus control.

In contrast to ubiquitin, the SUMOylation of proteins is not necessarily associated with their degradation. To assess whether SUMO1 influences Nox5 stability we monitored Nox5 expression following cycloheximide treatment and SUMO1 did not influence the turnover of Nox5 (Figure 4E). In addition, the proteasome inhibitor, MG132 was unable to reverse the SUMO1 dependent inhibition of Nox5 (Figure 4E).

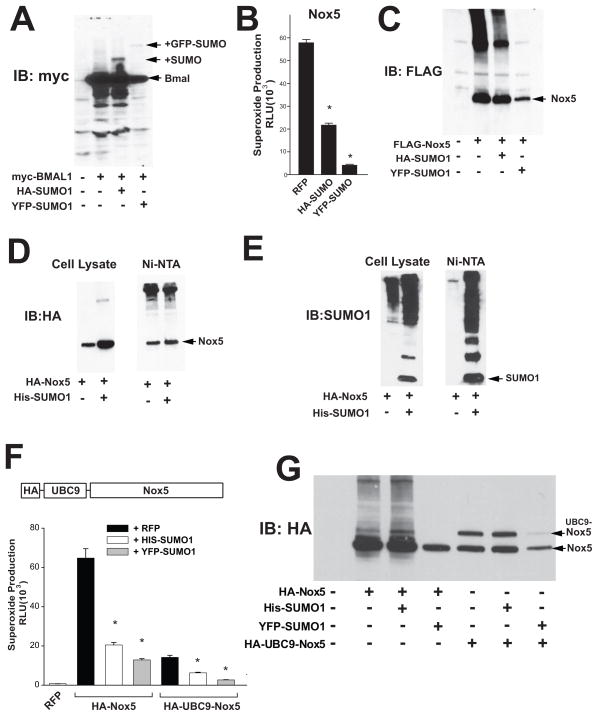

Co-expression of SUMO1 does not result in the SUMOylation of Nox5

Detection of protein SUMOylation can be technically demanding24 and to determine whether Nox5 is a substrate for SUMOylation, we adopted a number of approaches. Firstly, as a positive control, we co-transfected a known target of SUMO, myc- tagged BMAL1 (ARNTL)25 with HA-SUMO or EYFP-SUMO. As shown in Figure 5A, in the presence of SUMO, additional species of BMAL1 were observed that were approximately 10 and 40kDa higher in molecular weight (see arrows) corresponding to the respective addition of HA-SUMO and YFP-SUMO. In a parallel experiment with Nox5, we again observed a greatly diminished ability of Nox5 to generate ROS in the presence of HA-SUMO1 and YFP-SUMO1 (Figure 5B), but we did not consistently observe higher molecular species consistent with SUMOylation as shown for BMAL1. To improve sensitivity, we co-expressed a HIS-tagged SUMO1 with Nox5 and purified HIS tagged proteins using Ni-NTA affinity columns. The co-expression of Nox5 with HIS-SUMO1 did not result in the detection of additional, higher molecular weight species of Nox5 (Figure 5D). However, we did observe a substantial concentration of other HIS-SUMOylated proteins (Figure 5E). To yet further enhance sensitivity we constructed a fusion-protein consisting of the SUMO-specific conjugating enzyme UBC9 attached to the N-terminus of Nox5. This approach has been shown to promote robust SUMOylation of other substrates26. We cotransfected WT and UBC-Nox5 with HIS-SUMO1 and YFP-SUMO and measured both ROS production and protein expression. As shown in Figure 5F, HA-SUMO1 and YFP-SUMO significantly reduced ROS production from both the WT Nox5 and the UBC9-Nox5 fusion protein. However, we could not detect evidence of SUMOylation of Nox5 with either the WT or the fusion protein (Figure 5G). To examine whether Nox5 can be SUMOylated in vitro, we incubated immunoprecipitated HA-Nox5 with recombinant SUMO1, E1-activating (SAE1/SAE2) and E2–conjugating (UBC9) enzymes. In the presence of ATP, Nox5 appears to be SUMOylated as evidenced by higher molecular weight bands that are immunoreactive to SUMO1 (Supplemental Figure I). The SUMOylation of RANGAP1 (upper band on right) was used as a positive control. We also generated other fusion proteins including UBC9-SUMO1 which has improved ability to SUMOylate substrates and was more effective at inhibiting Nox5 activity versus SUMO1 alone (Supplemental Figure IIA). The direct fusion of SUMO1 with Nox5 also produced interesting results with the SUMO1-Nox5 fusion product producing dramatically less superoxide in comparison to the WT-Nox5. In contrast fusion of SUMO1 (ΔGG) that cannot be conjugated to substrates with Nox5 did not reduce ROS production. The fusion of SUMO1 to Nox5 resulted in the detection of several higher molecular weight species of Nox5 but these are unlikely to be due to polySUMOylation (Supplemental Figure IIB).

Figure 5. Nox5 is not a substrate for SUMOylation.

(A) COS-7 cells were transfected with myc-Bmal1 in the presence and absence of HA-SUMO1 and EYFP-SUMO1 and cell lysates immunoblotted with anti-myc. (B) COS-7 cells were transfected with FLAG-Nox5 and HA-SUMO1 or YFP-SUMO1. Superoxide release was monitored using L-012 (Results are presented as mean +/− SEM, n=6. * p<0.05 versus control) and (C) cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-FLAG. (D-E) Purification of HIS-SUMO labeled proteins using Ni-NTA columns. COS-7 cells expressing HA-Nox5 with or without HIS-SUMO were solubilized in urea, purified via Ni-NTA affinity columns and immunoblotted with anti-HA or anti-SUMO1. (F) Generation a Nox5-UBC9 fusion protein. COS-7 cells were transfected with WT HA-Nox5 or HA-UBC9-Nox5 with or without HIS-SUMO1 or YFP-SUMO1 and superoxide production monitored using L-012 Results are presented as mean +/− SEM, n=6. * p<0.05 versus control. (G) Cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-HA.

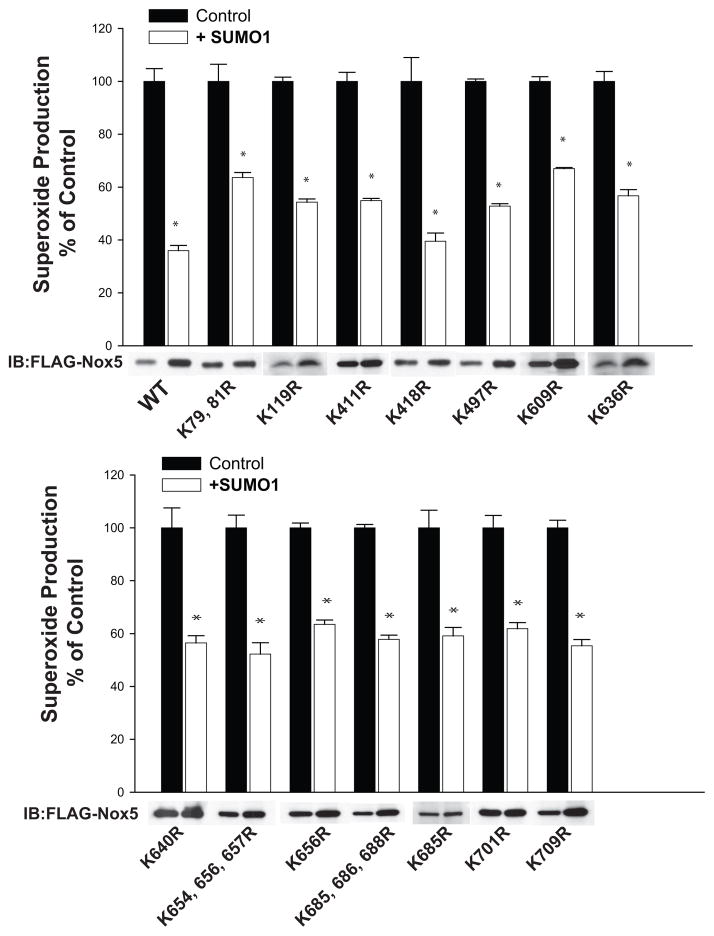

Mutation of predicted sites of SUMOylation and conserved lysines on Nox5 fail to prevent the inhibition of ROS production

Despite clear evidence that SUMO inhibits Nox5 activity, we could not detect the SUMOylation of Nox5. However, technical difficulties inherent in detecting SUMOylated proteins24 may be further compounded by the difficulties extracting and immunoblotting NADPH oxidases22. Indeed, the ability to SUMOylate Nox5 in an in vitro reaction suggests that the SUMOylation of Nox5 could be possible in cells and the direct fusion of SUMO1 with Nox5 suggests that when SUMO1 is attached to Nox5 it suppresses enzyme activity. Therefore, to exclude the possibility of Nox5 SUMOylation was occurring but could not be detected, we next adopted a loss of function approach by mutating select lysine residues to arginine. There are 2 predicted SUMO attachment sites on Nox5 at lysines 119 and 636 (SUMOsp2.0) out of 37 total lysine residues (Nox5 beta) that are extremely well conserved across species. However, mutation of these sites to arginine did not prevent the inhibition of Nox5 activity by SUMO1 (Figure 6). To exclude other lysine residues that may not conform to established SUMO motifs, we mutated other conserved lysine residues and assessed whether they prevented Nox5 inhibition. As shown in Figure 6, mutation of over 19 lysine residues failed to reverse the inhibitory effects of SUMO1. We also assessed whether SUMO could directly modify Nox5 activity in an isolated activity assay. We found that neither active forms of recombinant SUMO1 nor SUMO2 or SUMO3 had direct inhibitory actions on Nox5 (Supplemental Figure III).

Figure 6. Mutation of predicted sites of SUMOylation and conserved lysine residues fails to prevent SUMO1 mediated inhibition of Nox5.

COS-7 cells were transfected with WT FLAG-Nox5 (beta isoform) and mutants K79,81R, K119R, K411R, K418R, K497R, K609R, K636R, K640R, K654, 656, 657R, K656R, K685, 686,688R, K685R, K701R, K709R in the presence and absence of SUMO1. Superoxide release was monitored by L-012 chemiluminescence and results are presented as mean +/-SEM, n=6. * p<0.05 versus control. Relative expression of Nox5 is shown by anti-FLAG immunoblots (lower panel).

Discussion

The present study identifies SUMOylation as a novel mechanism that negatively regulates the activity of the NADPH oxidases and limits the production of ROS. We found that SUMO1 can potently reduce ROS production from Nox1-5 and that the active forms of SUMO1 and the SUMO-specific conjugating enzyme UBC9 are required to suppress ROS production. Furthermore, inhibition of endogenous SUMOylation using siRNA or a pharmacological inhibitor increases ROS production from human vascular smooth muscle cells and neutrophils and suggests that SUMO is an endogenous suppressor of ROS production.

The overproduction of ROS by Nox enzymes is a fundamental mechanism underlying the vascular dysfunction associated with cardiovascular disease and excessive inflammation9. Aside from changes in the expression level of the various subunits, Nox activity is controlled through post-translational modifications11. Nox5 is unique among the Nox isoforms in that its activity does not depend on the binding of additional proteins. Instead, the regulatory elements controlling Nox5 activity are contained within one protein and thus post-translational changes in the activity of Nox5 are likely to be due to modifications specific to Nox5 and not other proteins or subunits. For these reasons we used Nox5 as a surrogate to explore the mechanisms by which SUMO inhibits Nox activity. We found that only SUMO1, but not SUMO2 or the closely related SUMO3 was able to inhibit Nox5. This is consistent with previous reports that paralogs of SUMO exhibit significant substrate specificity. For example, RANGAP1 is preferentially modified by SUMO1 and topoisomerase II by SUMO2/33, 27. The ability of SUMO1 to suppress Nox5 activity in an isolated activity assay which separates Nox5 from cytosolic variables including other proteins, calcium, NADPH and FAD levels strongly suggests a direct effect of SUMO1 on Nox activity. Importantly, SUMO did not decrease the expression or turnover of Nox5 and the reduced production of ROS could not be reversed by inhibitors of the proteasome which further supports a posttranslational mechanism. As Nox5 activity is strongly dependent on calcium availability, we also investigated whether SUMO1 affects the concentration of intracellular calcium or the sensitivity of Nox5 to calcium which is mediated via phosphorylation of T494 and S49822. We found that SUMO did not affect the level of intracellular calcium or Nox5 phosphorylation and the ability of SUMO to reduce Nox5 activity in an isolated enzyme assay also rules out changes in subcellular localization as a primary mechanism of inhibition28. Recombinant SUMO1 protein did not directly inhibit Nox5 enzyme activity and a form of SUMO1(ΔGG) that cannot be conjugated to substrates failed to inhibit Nox5, suggesting that Nox5 is directly modified by SUMO1. However, we could not find evidence of Nox5 SUMOylation and mutational analysis of 19 predicted SUMO sites (ψKxE, where ψ is a bulky hydrophobic residue and x, any residue29) and other conserved lysine residues did not reveal a functionally significant attachment site for SUMO modification. Direct fusion of WT but not ΔGG SUMO1 with Nox5 resulted in enzyme inhibition and the appearance of multiple higher molecular weight species of Nox5, but it is unlikely that this reflects polySUMOylation. Thus, we must exclude direct SUMOylation of Nox5 as a mechanism of inhibition.

In addition to Nox5, we found that SUMO1 inhibited the activities of Nox1, 3 and Nox4. In neutrophils where the predominant oxidant producing enzyme is Nox230 a pharmacological inhibitor of endogenous SUMOylation, anacardic acid31, increased ROS production suggesting that SUMOylation also represses the activity of Nox2. Similarly in human vascular smooth muscle cells expressing Nox5, inhibition of SUMOylation potentiates superoxide production and provides further evidence that endogenous SUMO represses Nox activity to limit ROS production. However, comparison of the amino acid sequence of Nox5 with that of Nox1-4 reveals little evidence for the existence of conserved SUMOylation motifs or lysine residues that would provide a common mechanism for Nox inhibition. Other than direct SUMOylation, other potential mechanisms by which SUMO1 could inhibit Nox activity is via altered protein:protein interactions via a non-covalent SUMO interacting motif (SxS)32 which can orchestrate protein:protein interactions with other proteins that are SUMOylated. In addition, SUMO1 has been shown to SUMOylate superoxide dismutase1 which promotes increased protein stability. However, this mechanism cannot explain the ability of SUMO1 to inhibit Nox5 in an isolated enzyme assay or Nox4 which emits primarily hydrogen peroxide. We recently described the ability of MEK1 to regulate Nox5 activity via ERK1/233 and the SUMOylation of MEK134 could indirectly influence Nox5 activity. Evidence against this is the lack of change in Nox5 phosphorylation in the presence of SUMO1 and ability of SUMO1 to inhibit other Nox enzymes such as Nox4 that are not regulated by MEK1. Alternatively, as the majority of SUMO substrates are transcription factors 35 it is possible that changes in the expression level of other proteins could conspire to suppress NADPH oxidase activity. One pertinent example is the SUMOylation and inhibition of the transcription factor Pleomorphic Adenoma Gene-Like 2 which has been shown to regulate expression of the Nox subunit p67phox36. However, this could not influence Nox4 or Nox5 activity or even Nox1/Nox3 in the presence of NOXO1 and NOXA1. Further identification of novel mechanisms is likely to be a complex endeavor and beyond the scope of the present study.

SUMOylation is an important mechanism for the posttranslational regulation of protein function that includes transcription, intracellular localization, protein–protein interactions and cell signaling37, 38. The mechanisms controlling protein SUMOylation are poorly understood and cellular stress in the form of heat, osmotic pressure, genotoxic insults and ROS3, 4 have all been shown to promote SUMOylation. SUMOylation provides protection against thermal and ischemic damage in hibernating animals5 and is increased in a number of disease states including Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, diabetes and cancer 39. While the sum effect of increased SUMOylation is thought to be cytoprotective, the effect of SUMO on individual proteins is likely to vary considerably. In this study, the SUMOylation of Nox enzymes and the resulting reduction in ROS would be consistent with a protective mechanism that limits further cellular damage from excessive ROS formation. However, not all of the effects of SUMOylation are protective. The increased SUMOylation of ERK5 reduces its transcriptional activity and exacerbates deficits in cardiac function induced by myocardial ischemia20 and the SUMOylation of transglutaminase promotes inflammation40.

Reactive oxygen species in the form of hydrogen peroxide can dramatically increase protein SUMOylation3. However, the effect of ROS and oxidative stress on protein SUMOylation is complex. The amount of ROS is a very important variable and high concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (millimolar range) have been shown to promote SUMOylation whereas low concentrations decrease overall SUMOylation. Low concentrations of hydrogen peroxide preferentially oxidize the catalytic cysteine residues of the SUMO conjugating enzymes and reduce SUMOylation. In contrast higher concentrations inactivate the SUMO isopeptidases which deconjugate SUMO resulting in increased SUMOylation21. The influence of endogenously produced ROS is likely to add to this complexity. Inside the cell, ROS production occurs at discrete intracellular sites16, 41, 42 and the local concentration of ROS may vary considerably with location and thus may selectively influence the SUMOylation of proximal proteins. Indeed, even comparatively large concentrations of extracellular ROS fail to promote uniform changes in the SUMOylation/deSUMOylation of substrates21. While we have shown that inhibition of endogenous SUMOylation can potentiate ROS output in neutrophils and smooth muscle cells, it remains to be determined whether ROS production itself controls the degree of SUMOylation and inhibition of the NADPH oxidases or whether other cellular stresses participate.

In summary, we have shown that SUMO1 suppresses the activity of the Nox enzymes and reduces ROS production. Inhibition of SUMOylation potentiates ROS production suggesting that endogenous SUMO1 controls ROS output. However, we did not find evidence to support the concept that Nox enzymes are direct substrates for SUMO conjugation. Further studies are necessary to elucidate the mechanisms by which SUMOylation impacts the activity of the Nox enzymes and to determine the importance of this pathway in diseases associated with the overproduction of reactive oxygen species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

a)We appreciate the technical support of Pulkit Malik.

b) This work was supported by grants from the NIH (HL085827, HL092446) and the AHA (EIA to DF) and also by the Cardiovascular Discovery Institute, Medical College of Georgia.

Footnotes

c) Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Mahajan R, Delphin C, Guan T, Gerace L, Melchior F. A small ubiquitin-related polypeptide involved in targeting RanGAP1 to nuclear pore complex protein RanBP2. Cell. 1997;88:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81862-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geiss-Friedlander R, Melchior F. Concepts in sumoylation: a decade on. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:947–956. doi: 10.1038/nrm2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saitoh H, Hinchey J. Functional heterogeneity of small ubiquitin-related protein modifiers SUMO-1 versus SUMO-2/3. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6252–6258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong Y, Rogers R, Matunis MJ, Mayhew CN, Goodson ML, Park-Sarge OK, Sarge KD. Regulation of heat shock transcription factor 1 by stress-induced SUMO-1 modification. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40263–40267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YJ, Miyake S, Wakita H, McMullen DC, Azuma Y, Auh S, Hallenbeck JM. Protein SUMOylation is massively increased in hibernation torpor and is critical for the cytoprotection provided by ischemic preconditioning and hypothermia in SHSY5Y cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:950–962. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nacerddine K, Lehembre F, Bhaumik M, Artus J, Cohen-Tannoudji M, Babinet C, Pandolfi PP, Dejean A. The SUMO pathway is essential for nuclear integrity and chromosome segregation in mice. Dev Cell. 2005;9:769–779. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohara Y, Peterson TE, Harrison DG. Hypercholesterolemia increases endothelial superoxide anion production. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2546–2551. doi: 10.1172/JCI116491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.San Martin A, Du P, Dikalova A, Lassegue B, Aleman M, Gongora MC, Brown K, Joseph G, Harrison DG, Taylor WR, Jo H, Griendling KK. Reactive oxygen species-selective regulation of aortic inflammatory gene expression in Type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H2073–2082. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00943.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lambeth JD. Nox enzymes, ROS, and chronic disease: an example of antagonistic pleiotropy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:332–347. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jay D, Hitomi H, Griendling KK. Oxidative stress and diabetic cardiovascular complications. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambeth JD, Kawahara T, Diebold B. Regulation of Nox and Duox enzymatic activity and expression. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:319–331. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banfi B, Clark RA, Steger K, Krause KH. Two novel proteins activate superoxide generation by the NADPH oxidase NOX1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3510–3513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martyn KD, Frederick LM, von Loehneysen K, Dinauer MC, Knaus UG. Functional analysis of Nox4 reveals unique characteristics compared to other NADPH oxidases. Cell Signal. 2006;18:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fulton DJ. Nox5 and the regulation of cellular function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2443–2452. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen K, Kirber MT, Xiao H, Yang Y, Keaney JF., Jr Regulation of ROS signal transduction by NADPH oxidase 4 localization. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:1129–1139. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stadtman ER, Levine RL. Free radical-mediated oxidation of free amino acids and amino acid residues in proteins. Amino Acids. 2003;25:207–218. doi: 10.1007/s00726-003-0011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gryglewski RJ, Palmer RM, Moncada S. Superoxide anion is involved in the breakdown of endothelium-derived vascular relaxing factor. Nature. 1986;320:454–456. doi: 10.1038/320454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bossis G, Melchior F. SUMO: regulating the regulator. Cell Div. 2006;1:13. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shishido T, Woo CH, Ding B, McClain C, Molina CA, Yan C, Yang J, Abe J. Effects of MEK5/ERK5 association on small ubiquitin-related modification of ERK5: implications for diabetic ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2008;102:1416–1425. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.168138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bossis G, Melchior F. Regulation of SUMOylation by reversible oxidation of SUMO conjugating enzymes. Mol Cell. 2006;21:349–357. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jagnandan D, Church JE, Banfi B, Stuehr DJ, Marrero MB, Fulton DJ. Novel mechanism of activation of NADPH oxidase 5. calcium sensitization via phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6494–6507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608966200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Q, Malik P, Pandey D, Gupta S, Jagnandan D, Belin de Chantemele E, Banfi B, Marrero MB, Rudic RD, Stepp DW, Fulton DJ. Paradoxical activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by NADPH oxidase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1627–1633. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.168278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tatham MH, Rodriguez MS, Xirodimas DP, Hay RT. Detection of protein SUMOylation in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1363–1371. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardone L, Hirayama J, Giordano F, Tamaru T, Palvimo JJ, Sassone-Corsi P. Circadian clock control by SUMOylation of BMAL1. Science. 2005;309:1390–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1110689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jakobs A, Koehnke J, Himstedt F, Funk M, Korn B, Gaestel M, Niedenthal R. Ubc9 fusion-directed SUMOylation (UFDS): a method to analyze function of protein SUMOylation. Nat Methods. 2007;4:245–250. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azuma Y, Arnaoutov A, Dasso M. SUMO-2/3 regulates topoisomerase II in mitosis. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:477–487. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200304088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawahara T, Lambeth JD. Phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate modulates Nox5 localization via an N-terminal polybasic region. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4020–4031. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez MS, Dargemont C, Hay RT. SUMO-1 conjugation in vivo requires both a consensus modification motif and nuclear targeting. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12654–12659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rotrosen D, Yeung CL, Leto TL, Malech HL, Kwong CH. Cytochrome b558: the flavin-binding component of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Science. 1992;256:1459–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.1318579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukuda I, Ito A, Hirai G, Nishimura S, Kawasaki H, Saitoh H, Kimura K, Sodeoka M, Yoshida M. Ginkgolic acid inhibits protein SUMOylation by blocking formation of the E1-SUMO intermediate. Chem Biol. 2009;16:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minty A, Dumont X, Kaghad M, Caput D. Covalent modification of p73alpha by SUMO-1. Two-hybrid screening with p73 identifies novel SUMO-1-interacting proteins and a SUMO-1 interaction motif. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36316–36323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004293200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandey D, Fulton DJ. Molecular Regulation of NADPH Oxidase 5 (Nox5) via the MAPK kinase pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01163.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kubota Y, O’Grady P, Saito H, Takekawa M. Oncogenic Ras abrogates MEK SUMOylation that suppresses the ERK pathway and cell transformation. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:282–291. doi: 10.1038/ncb2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gill G. Something about SUMO inhibits transcription. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:536–541. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ammons MC, Siemsen DW, Nelson-Overton LK, Quinn MT, Gauss KA. Binding of pleomorphic adenoma gene-like 2 to the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha-responsive region of the NCF2 promoter regulates p67(phox) expression and NADPH oxidase activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17941–17952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610618200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hay RT. SUMO: a history of modification. Mol Cell. 2005;18:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson ES. Protein modification by SUMO. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:355–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao J. Sumoylation regulates diverse biological processes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:3017–3033. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7137-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luciani A, Villella VR, Vasaturo A, Giardino I, Raia V, Pettoello-Mantovani M, D’Apolito M, Guido S, Leal T, Quaratino S, Maiuri L. SUMOylation of tissue transglutaminase as link between oxidative stress and inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;183:2775–2784. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terada LS. Specificity in reactive oxidant signaling: think globally, act locally. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:615–623. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ushio-Fukai M. Compartmentalization of Redox Signaling through NADPH Oxidase-derived ROS. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(6):1289–1299. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.