Abstract

The development of the hematopoietic system involves multiple cellular steps beginning with the formation of the mesoderm from the primitive streak, followed by emergence of precursor populations that become committed to either the endothelial or hematopoietic lineages. A number of growth factors such as activins and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) are known to regulate the early specification of hematopoietic fated mesoderm, notably in amphibians. However, the potential roles of these factors in the development of mesoderm and subsequent hematopoiesis in the human have yet to be delineated. Defining the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which combinations of mesoderm-inducing factors regulate this stepwise process in human cells in vitro is central to effectively directing human embryonic stem cell (hESC) hematopoietic differentiation. Herein, using hESC-derived embryoid bodies (EBs), we show that Activin A, but not basic FGF/FGF2 (bFGF), promotes hematopoietic fated mesodermal specification from pluripotent human cells. The effect of Activin A treatment relies on the presence of bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) and both of the hematopoietic cytokines stem cell factor and fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-3 ligand, and is the consequence of 2 separate mechanisms occurring at 2 different stages of human EB development from mesoderm to blood. While Activin A promotes the induction of mesoderm, as indicated by the upregulation of Brachyury expression, which represents the mesodermal precursor required for hematopoietic development, it also contributes to the expansion of cells already committed to a hematopoietic fate. As hematopoietic development requires the transition through a Brachyury+ intermediate, we demonstrate that hematopoiesis in hESCs is impaired by the downregulation of Brachyury, but is unaffected by its overexpression. These results demonstrate, for the first time, the functional significance of Brachyury in the developmental program of hematopoietic differentiation from hESCs and provide an in-depth understanding of the molecular cues that orchestrate stepwise development of hematopoiesis in a human system.

Introduction

During gastrulation in early embryogenesis the emergence of the germ layer fated to form blood, the mesoderm, arises from ingression of epiblast cells through the primitive streak and a rapid process of epithelial to mesenchymal transition. The protein product of the T gene, Brachyury, is widely used as the definitive benchmark for mesodermal differentiation. Its central role in mesoderm formation and subsequent hematopoietic differentiation in the posterior mesoderm has been explored in Xenopus [1], zebrafish [2], chick [3], and mouse [4]. Surprisingly, these findings have never been examined in human hematopoietic differentiation.

In amphibians, Activin A and fibroblast growth factor (FGF), singly or together, regulate the expression of the pan-mesodermal marker Brachyury, and the formation and differentiation of the hematopoietic mesoderm [5]. Although a number of studies in mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) have led to the idea that the hematopoietic mesoderm develops from, and remains confined within a cell population expressing Brachyury [6], the functional significance of Brachyury has yet to be demonstrated [7]. In light of the fundamental differences in the cytokine signaling pathways that orchestrate lineage differentiation in human versus mouse ESCs [8], we sought to examine the individual and combined actions of Activin A and basic FGF (bFGF) on the cellular sequence of hematopoietic development of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) spanning from the induction of mesoderm to the emergence of hematopoietic precursors and finally to the commitment and maturation of definitive blood cells.

Human ESCs are capable of differentiation into cells of all 3 germ layers and are endowed with a seemingly unlimited proliferative potential. Blood is a product of the stepwise differentiation of mesoderm, which initially becomes fated to the endothelial and hematopoietic lineages in the extraembryonic yolk sac following gastrulation. Our laboratory [9–13], and others [14], have been successful in defining differentiation conditions for human embryoid bodies (EBs) that recapitulate the developmental progression from mesoderm to blood. To some extent, each stage of this process can be monitored by changes in gene expression [15,16]. The initial formation of transient mesendoderm and subsequent mesoderm can be mapped by the expression of the T-box transcription factor Brachyury [15,17]. Subsequent bipotential hemogenic endothelial intermediate formation can be defined by the expression of the endothelial cell (EC) markers PECAM-1 (CD31), Flk-1 (VEGFR-2, KDR), and VE-cadherin, but not the hematopoietic marker CD45 (CD45negPFV cells); while committed, unipotential blood cells are CD45+, but lack EC marker expression [12,14].

Studies using in vitro model systems have established the mesodermal origin of the hematopoietic system [6,18]. The emergence of primitive hematopoietic CD45negPFV cells occurs at approximately day 10 of EB differentiation [9,10,12]. We define this period as stage I and it is followed by the generation of committed CD45+ hematopoietic cells from day 10 onward, termed stage II [12]. More recently, our laboratory has provided indirect evidence in hESCs of a link between the development of mesoderm and hematopoiesis, which is mediated by noncanonical Wnt signaling [13]. However, the cellular and molecular sequence ranging from the induction mesoderm to the emergence of the earliest committed blood cells from hESCs remains to be defined, which represents a major challenge. Toward the goal of promoting hematopoiesis from hESCs, it may thus be necessary to focus on developmental growth factors known to play critical roles on the induction and differentiation of mesoderm, as well documented in amphibians [19]. In this context, both Activin A and bFGF (AF) appear as prime candidates.

However, in instances where the activity of AF have been examined in hESCs, these factors have been shown to either maintain pluripotency [8,20,21] or induce endoderm specification [22–26] with one recent article examining their roles in early mesodermal differentiation in conjunction with bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) [27], but not hematopoiesis. Consequently, despite the documented role of AF in the regulation of human adult hematopoiesis [28,29], little focus has been directed to addressing the role of these factors in the progression of hESC development from mesoderm to blood.

In the present study, we demonstrate that Activin A, but not bFGF, enhances the production of hematopoietic cells from hESCs by at least 2 distinct mechanisms. Activin A promotes the induction of mesoderm as evidenced by the upregulation of Brachyury expression and the expansion of cells already committed to blood, but does not impact the intermediate stage of the CD45negPFV precursor. Furthermore, our findings reveal that the effects of Activin A rely on the presence of BMP4, stem cell factor (SCF), and fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-3 ligand (Flt3L). Importantly, our study correlates the requirement of Brachyury for the hematopoietic differentiation of hESCs for the first time.

Materials and Methods

Human ES cell culture and differentiation

Human ESC lines H9 and H1 [30] (NIH codes WA09 and WA01, respectively) obtained from the WiCell Research Institute (Madison, WI) were maintained as previously described [31]. Briefly, undifferentiated hESCs were seeded on Matrigel (BD Biosciences) coated plates in a mouse embryonic fibroblast-conditioned medium (MEF-CM) supplemented with 8 ng/mL of human recombinant bFGF (Invitrogen). The medium was changed daily, and hESCs were dissociated with 200 U/mL Collagenase IV (Invitrogen) and passaged weekly at a ratio of 1:2 or 1:3.

EB formation and hematopoietic differentiation

Confluent hESCs were treated with 200 U/mL Collagenase IV for 5–10 min and then transferred to 6-well ultra-low attachment plates (Corning) in a medium consisting of KO-DMEM supplemented with 20% nonheat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone), 1% nonessential amino acids, 1 mM L-glutamine, and 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol to allow for EB formation. For serum-free culture of EBs, a supplemented StemPro-34 medium (Invitrogen) was used with 200 μg/mL transferrin, 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 0.4 mM monothioglycerol. The next day (day 1), EBs were given a fresh differentiation medium supplemented with 25 ng/mL BMP-4 (R&D Systems) in the presence or absence of the following factors: Activin A, 2 ng/mL (R&D Systems); bFGF, 10 ng/mL (R&D Systems); SCF, 300 ng/mL (Amgen, Inc.); Flt3L, 300 ng/mL (R&D Systems). EBs were cultured for the indicated time points with fresh media changes and treatments every 4 to 5 days unless stated otherwise. Hematopoietic colony-forming units (CFUs) from EBs were also assayed according to previously published protocols [32]. Briefly, EBs were dissociated with collagenase B and a cell dissociation buffer followed by filtration through a 35 μm cell strainer to obtain single-cell suspension, counted and plated into MethoCult (H4434; Stem Cell Technologies) and counted after 14 days to assess resultant colony numbers.

Flow cytometry analysis

Single-cell suspensions from EBs were prepared as described previously [12]. Briefly, EBs were dissociated with 0.4 U/mL Collagenase B (Roche) for 2 h at 37°C, followed by the cell dissociation buffer for 10 min at 37°C. They were then dissociated by gentle pipetting and passed through a 35 μm cell strainer. Single-cell suspensions were resuspended at ∼2–5×105 cells/mL in PBS containing 1% FBS and stained for 30 min at 4°C with CD31-PE, CD34-FITC, CD45-APC, Flk-1 (VEGFR2/KDR)-APC monoclonal antibodies (all from BD Biosciences), or the corresponding isotypes. After washing, cells were stained with the 7-Aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) viability dye (Beckman Coulter) in PBS+1% FBS for 15 min at room temperature (RT). Live cells were identified by 7-AAD exclusion and analyzed using a FACSCalibur (BDIS) and FlowJo 8.5.2 software (Tree Star, Inc.). Intracellular staining of Brachyury was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions, using a phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-human Brachyury polyclonal antibody (R&D Systems).

ELISA

ELISA to assess bFGF levels in different batches of serum-containing EB media was performed using the human FGF-basic ELISA Max set following the manufacturer's instructions (BioLegend). bFGF levels were determined relative to a serial dilution series of the reconstituted bFGF standard. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a background correction at 570 nm on a BMG Omega FLUOstar plate reader.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemical staining for Brachyury (antibody purchased from R&D Systems) was performed on 9 μm cryosections from EBs. EBs were isolated at the indicated time points, washed twice with PBS, embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT (Sakura), and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. About 150 serial sections per specimen were collected. Three cryosections per specimen at an interval of 30 serial sections (a distance of 270 μm) were used for each staining. After fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at RT and blocking with 10% normal donkey serum, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 1% BSA in PBS for 45 min, EB sections were incubated with either the mouse IgG1κ isotype (5 μg/mL) or the Brachyury antibody (10 μg/mL) followed by Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-goat IgG (Molecular Probes) for 45 min at RT, and then counterstained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). A morphometric analysis of stained EBs was performed by a computer-assisted image analysis (Image Pro Plus 4.5). All of the specimens were coded to ensure blinded assessment.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

About 1–5 μg of total RNA was converted to cDNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and a series of diluted samples were used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using the SYBR green (Stratagene) DNA binding dye and an MX4000 instrument (Stratagene). Before the qPCR analysis, an end-point PCR was performed for each gene to check the size of the amplicon. Primer3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer) was used to design all primers (listed in Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd). Each qPCR reaction used 2 mM MgCl, 0.4 mM dNTP, 8% Glycerol, 3% DMSO, 150 nM of each primer, 0.375 μL of 1:500 dilution of reference dye, and 2.5 μL of 1:2,000 dilution of SYBR green. The amplicon size was checked by electrophoresis and the melt curve analysis was used to verify specificity of the amplification reaction. For each gene, the analysis was performed in triplicate and included a no template control and a standard curve using dilutions of a control cDNA sample spanning 3 orders of magnitude. Based on the cycle threshold values, the relative expression of the gene of interest was calculated after normalization to GAPDH and a calibrator sample (undifferentiated hESCs) defined as 1.0.

Small interfering RNA transfection

For small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfections, clumps of hESC colonies were obtained during passage and transferred to 6-well ultralow attachment plates. Cells were transfected in the EB differentiation medium using an siPORT™ NeoFX™ transfection agent (Ambion) in the presence of 5–100 nM of Brachyury or scramble siRNAs, according to the manufacturer's instructions. About 100 nM was experimentally determined to be the optimal concentration by titration. After 24 h, a medium was changed to the EB differentiation medium supplemented with BMP4, SCF, and Flt3L in the presence or absence of Activin A. All siRNAs (Brachyury siRNA ID: sc-29820, Scramble siRNA ID: sc-36869) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Lentiviral overexpression

For lentiviral experiments, a second-generation lentiviral reporter construct, EGPCS1, derived from the EF1α-eGFP-PGK-PAC lentiviral vector of Dr. Benjamin Reubinoff [33], containing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) driven by the EF1α promoter was used. Full-length cDNA from the human T gene was cloned in 3′ of the PGK promoter to create a Brachyury-expressing eGFP reporter construct: EGPCS1-BRA. Briefly, lentiviral vectors were cotransfected with second-generation packaging plasmids encoding gag/pol, REV, and vesicular stomatitis virus G protein at a ratio of 2:1 into 293FT cells using 3 μL per μg plasmid of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Viral supernatants were collected 48–72 h after transfection and concentrated by ultracentrifugation to produce virus stocks with titers of 5–8×107 infectious units/mL, determined in HeLa cells. ES cells were transduced for 24 h at multiplicities of infection of 1, 1 day after passage in MEF-CM containing 8 ng/mL of both bFGF and polybrene (Chemicon). GFP-positive colonies from transduced ES cells using both control EGPCS1 and Brachyury EGPCS1-BRA were plucked and propagated. These clones were subsequently used to form EBs. Transduction efficiency was monitored by observing eGFP levels in EBs (Fig. 5).

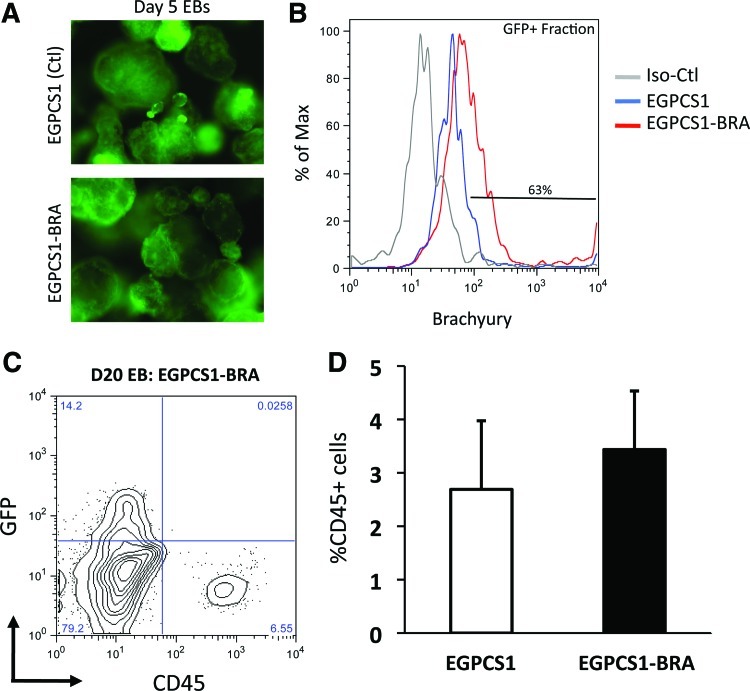

FIG. 5.

Constitutive mis-expression of Brachyury does not augment definitive (CD45+) hematopoietic cell generation. (A) Representative photos of day 5 EBs made from hESCs transduced with either a control vector (EGPCS1) or a vector harboring Brachyury cDNA (EGPCS1-BRA) demonstrating high transformation efficiency by GFP fluorescence levels. (B) Intracellular flow cytometry with Brachyury antibody in GFP+ cells from day 20 EBs showing 63% of EGPCS1-BRA-transduced cells are Brachyury+. Negative isotype staining was also performed on EGPCS1-BRA-transduced cells. (C) Representative flow cytometry showing GFP+ EGPCS1-BRA-transduced cells are negative for CD45 at day 20 of EB differentiation. (D) Summary of flow cytometry for CD45 (n=4) showing similar numbers of CD45+ cells in control and Brachyury-transduced EBs. Bars show mean values±SEM. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean±SEM and generated from at least 3 independent experiments. Results were considered to be statistically significant when P<0.05 as determined by the Student's t-test.

Results

Activin A, but not bFGF, potentiates hematopoietic development of hESCs

To determine whether AF plays additive or individual roles in the hematopoietic development of hESCs, we assessed the individual and combined effects of these factors on the generation of hematopoietic precursor cells, defined by the expression of PECAM-1, Flk1, and VE-cadherin and lack of CD45 (so-called CD45negPFV cells), and committed CD45+ cells arising from CD45negPFV cells (Fig. 1A) [12]. In keeping with previous reports in amphibians, the dose of Activin A critically influences cell fate decisions between mesoderm and endoderm [34–36]. Accordingly, we set out by titrating the dose of Activin to favor hematopoietic differentiation of hESCs, which was found to be 2 ng/mL. Subsequently, EB cultures underwent 3 treatment regimes of either SCF and Flt3L (SF, defined as our control treatment), AF, or both combinations (AF+SF). All EB culture experiments in this study have also included the use of the TGFβ superfamily ligand BMP4, which has a proven role in embryonic hematopoiesis [37–39]. While the 3 treatments yielded a similar frequency and total number of CD45negPFV precursors (Fig. 1B), only the combination of mesoderm-inducers and hematopoietic growth factors (AF+SF) increased the frequency and total numbers of CD45+ cells significantly above control levels (39% vs. 22%, 1×105 vs. 7×104; Fig. 1C, D). Noticeably, the frequency and numbers of CD45+ cells following AF treatment only were much lower than those induced by SF only (8% vs. 22%, 1×104 vs. 7×104; Fig. 1C, D), suggesting that the mesoderm inducers (AF) alone could not support hematopoiesis beyond the CD45negPFV precursor stage (Fig. 1B). This observation was further supported by methylcellulose-based hematopoietic colony formation assays, which revealed significantly lower CFU numbers when SF was omitted from EB cultures (Fig. 1D). Thus, the combination of mesoderm inducers (AF) and hematopoietic growth factors (SF) was presumed required to enhance hESC-derived hematopoiesis.

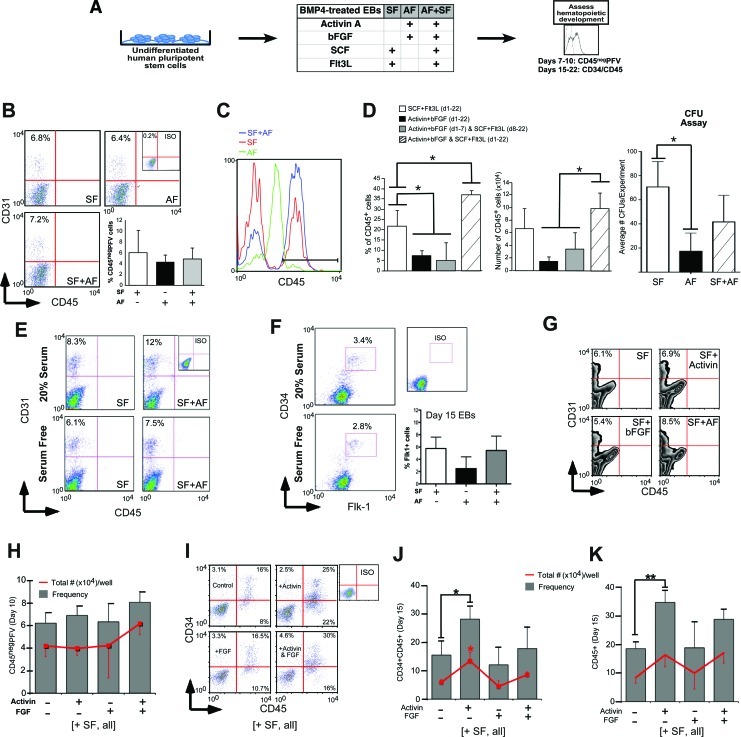

FIG. 1.

The role of Activin A and bFGF (AF) in hematopoietic differentiation of hESCs. (A) Schematic of human EB differentiation protocol. EBs were cultured with BMP4 and the indicated factors for 15–22 days, then dissociated and analyzed for expression of precursor and hematopoietic markers, including CD31, CD34, and CD45. (B) BMP4-treated EBs differentiated under 3 different GF regimes: AF; SCF and Flt3L (SF); or both combinations (AF+SF), show a similar frequency of CD45negPFV cells (CD31+CD45−). (C) Representative flow cytometry histograms showing increase in CD45 expression at day 22 of EB differentiation in the presence of AF+SF, but neither AF nor SF alone. (D) The increase in the frequency and total numbers of CD45+ cells is mediated by the simultaneous [AF+SF (d1-22)], but not sequential [AF (d1-7)+SF (d8-22)] addition of AF and SF over the entire course of EB differentiation. CFU counts show colony-forming potential of AF is significantly lower than SF. (E) Representative flow cytometry showing unaltered CD45negPFV levels in day 11 EBs grown with or without serum in the presence of SF or AF+SF. (F) Levels of CD34+Flk1+ progenitors in day 11 (flow plots) and day 15 (bar graph) EBs also remain unaltered irrespective of serum or Activin. (G) The representative flow cytometry analysis showing lack of significant variations in the percentage of CD45negPFV precursors in response to Activin A and/or bFGF at day 10 of EB culture. (H) Summary of total number and frequency of CD45negPFV cells in response to AF showing lack of statistically significant differences. (I) Representative flowcharts of primitive (CD34+CD45+) and mature CD45+ cells. (J) Increase in percentage and total number of CD34+CD45+ cells after addition of Activin. (K) Percentage, but not total number of CD45+ cells, is increased by Activin A. Bars for all panels indicate mean±SEM (*P<0.05, **P<0.01). bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; BMP4, bone morphogenetic protein 4; CFU, colony-forming unit; EBs, embryoid bodies; Flt3L, fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-3 ligand; hESCs, human embryonic stem cells; SCF, stem cell factor. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

To test the hypothesis that a concerted mesodermal and hematopoietic growth factor treatment is required to promote hematopoiesis, we applied the 2 sets of factors sequentially, beginning with AF from days 0 to 7 of EB development, and followed by SF from day 8 onward [AF(d1-7)+SF(d8-22)]. This treatment yielded fewer CD45+ cells than control SF only (5% vs. 22% and 4×104 vs. 7×104; Fig. 1D), suggesting that the addition of SF after 7 days of EB culture could not significantly enhance the level of hematopoietic differentiation observed in the presence of mesoderm inducers (AF). Consequently, the stimulation of hematopoietic development of hESCs is due to the use of AF in addition to the hematopoietic factors (SF) in combination, rather than separate or sequential application.

Activin A can be partially inhibited by serum, at least at the high doses used for endodermal differentiation [23], and thus the effects of serum were also examined by culturing hESCs in serum-free EB media versus standard EB media. Numbers of CD45negPFV cells were similar between EBs grown in serum and those grown serum free (Fig. 1E). The vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2, Flk1, has been shown to mark progenitors with hemogenic potential [40] and served as an additional early marker used to track hematopoiesis in this study, but was found not to be modulated by the use of AF (Fig. 1F).

Previous studies have suggested that FGF signaling can potentiate the action of Activin A in the induction of mesoderm [41–43], leading us to question the individual contribution of these factors to hematopoietic development from hESCs. As shown in Fig. 1G and H, AF, either alone or in combination, exhibited a similar effect on the frequency and total numbers of primitive CD45negPFV cells. However, the frequencies and total numbers of both primitive (CD34+CD45+, Fig. 1I, J) and mature (CD45+, Fig. 1I, K) hematopoietic cells were at their highest levels in response to Activin alone compared to bFGF alone or the combined factors, providing evidence that addition of exogenous bFGF does not potentiate the effect of Activin on hematopoietic differentiation of hESCs, as previously demonstrated in other model systems [41–43]. To avoid uncertainty with respect to bFGF levels present in serum-containing EB media, an ELISA was performed to determine levels of this growth factor from 3 separate batches of EB media made with different serum lots. This experiment demonstrated that bFGF is present at picomolar to subpicomolar levels in standard EB media, ruling out the contribution of bFGF contained in serum (Supplementary Fig. S1). Given the ability of Activin A alone to enhance hematopoiesis of hESCs, the effects of this factor were further characterized.

Activin A affects hematopoietic commitment subsequent to hemogenic precursor stage

Our laboratory has functionally defined 2 main stages of hematopoiesis over the course of EB development [12]. Stage I, from day 0 to 7–10, is characterized by the emergence of the CD45negPFV hemogenic precursor, while stage II, from day 10 onward, is defined by the appearance of committed hematopoietic cells that acquire CD45 expression. Based on this definition, we sought to delineate the cellular mechanisms underlying the hematopoietic enrichment of hESC cultures by treatment with Activin A. To this end, we exposed EBs to Activin A for the duration of stage I (days 1 to 7), stage II (days 8 to 22), or both stages (days 1–22) as outlined in Fig. 2A. Regardless of the duration of exposure to Activin A, no significant difference in the frequency of CD45negPFV cells was observed (Supplementary Fig. S2). However, Activin A proved most effective at increasing the frequency of CD45+ cells when present during both stages (Fig. 2B, C). Surprisingly, the total number of CD45+ cells remained unchanged whether Activin A was present during stage II only or both stages (Fig. 2C, red line), but translated to a 2-fold reduction when Activin A was present during stage I only. Taken together, these findings suggest that Activin A promotes the hematopoietic differentiation of hESCs via a distinct cellular mechanism during each stage of EB development.

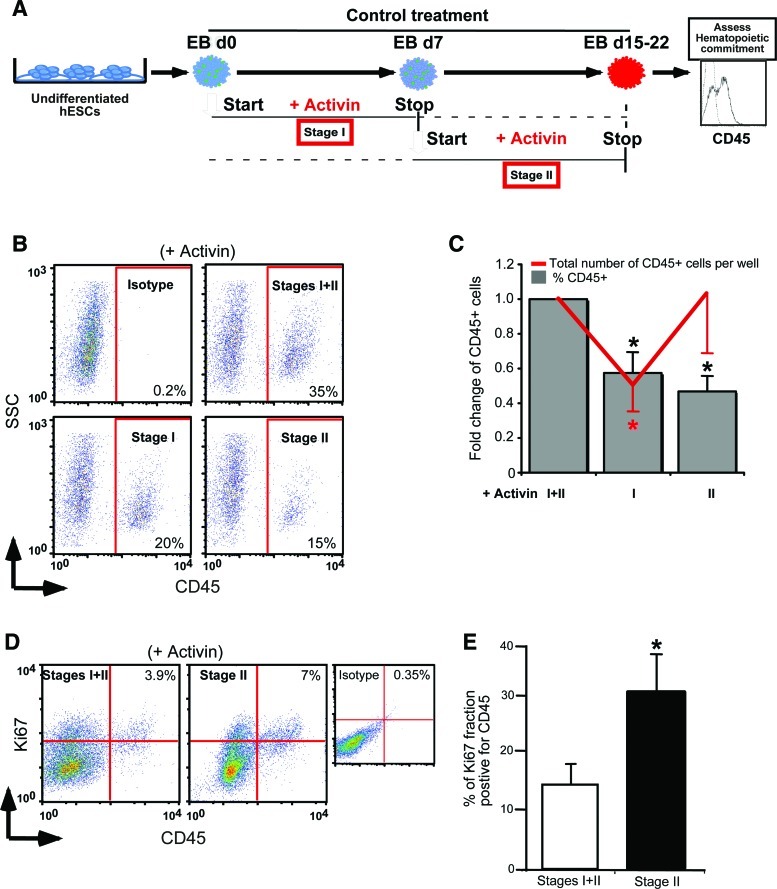

FIG. 2.

Effects of Activin A on hematopoietic commitment in EB cultures. (A) Schematic diagram of addition of Activin A during different stages of EB development. Stage I (days 0 to 7) represents the period of differentiation of undifferentiated hESCs into primitive CD45negPFV precursors. Stage II (days 7 to 15–22) is the period of differentiation of CD45negPFV precursors cells into CD45+ committed hematopoietic cells. (B) Representative flow cytometry dot plots showing maximum increase in CD45 expression at day 15 of EB development when Activin A is present during both stages of EB differentiation. (C) Fold reduction in percentage, and total number of CD45+ cells upon addition of Activin A during either stage compared to both stages taken as control assessed at day 15 of EB development (n=6). (D) Representative flow cytometry dot plots showing the increase in CD45 and Ki67 coexpression in the presence of Activin A at stage II only versus stages I and II assessed at day 15 of EB development. (E) Increase in the expression of CD45 within the fraction of proliferating cells from day 15 EB based on their expression of Ki67 (gated on Ki67+ population) detected by flow cytometry. Bars for all panels indicate mean±SEM (*P<0.05). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

In addition, our observation that the total number of CD45+ cells was maintained upon Activin A treatment during either stage II or both stages, despite the reduction in the frequency of this subset, suggests that Activin A may affect the proliferation status of CD45+ cells. To assess CD45 levels of proliferating cells we analyzed the expression of intracellular Ki67, a nuclear protein present during all active phases of the cell cycle, by flow cytometry [44]. Exposure to Activin A uniquely during stage II resulted in a 7% CD45/Ki67 double-positive population (Fig. 2D). In contrast, the CD45/Ki67 double-positive population accounted for only 3.9% of cells exposed to Activin A at stages I and II (Fig. 2D). This represented a roughly 2-fold increase in CD45+ cells in the Ki67+ fraction exposed to Activin during Stage II only over 3 independent experiments (31% vs. 15%; Fig. 2E). Activin A exposure had no significant impact on the proliferation of the primitive hematopoietic subsets (CD34+CD45+ and CD45negPFV cells), indicating that Activin A may only be targeting the committed cells that emerge during stage II. This provides evidence that Activin A treatment results in proliferation of committed hematopoietic cells during the later stages of EB development.

Activin A promotes Brachyury induction in the stimulation of early hematopoietic differentiation, and requires BMP4 as a co-factor

As stated, Activin A has been implicated in the induction of hematopoietic mesoderm in lower vertebrates [45–47]. In hESCs, however, this factor has been used to direct differentiation toward endoderm [22–26] and its potential action on the specification of hematopoietic mesoderm has yet to be reported. The inability of Activin A to stimulate the development of CD45negPFV hemogenic precursors combined with the reduction in frequency of hematopoietic output observed when Activin A was absent during stage I of EB development suggests that Activin A may exert its action at a step preceding the emergence of the hemogenic precursor, possibly during the induction of mesoderm. To test this hypothesis, we examined the transcriptional programs induced by Activin A by monitoring gene expression patterns indicative of primary germ layer specification. Using qPCR, we tracked the induction of mesoderm by monitoring the expression of Brachyury over time. EBs showed clear fluctuations in Brachyury expression irrespective of Activin A exposure with similar peak levels between days 1 and 3 of differentiation (Fig. 3A). However, in the presence of Activin A, expression of the ectodermal transcription factor Pax6 [48] was 45% and 88% lower than control EBs at days 3 and 10 of Activin A treatment, respectively (Fig. 3B). This is consistent with the finding that inhibition of Activin signaling is required to specify hESCs toward neuroectoderm [49]. The specification of endoderm, which was examined by expression of the early endodermal transcription factor HNF3α (FoxA1), was unchanged at day 3 of EB development, but was in fact slightly augmented (1.5-fold) in the absence of Activin A at day 10 (Supplementary Fig. S3). This suggests that the dose of 2 ng/mL of Activin A used in this study was not sufficient to enhance endodermal differentiation. Indeed, previous studies have used 100 ng/mL of Activin A for this purpose, and found no effect on endodermal differentiation of hESCs with as much as 10 ng/mL Activin A [23].

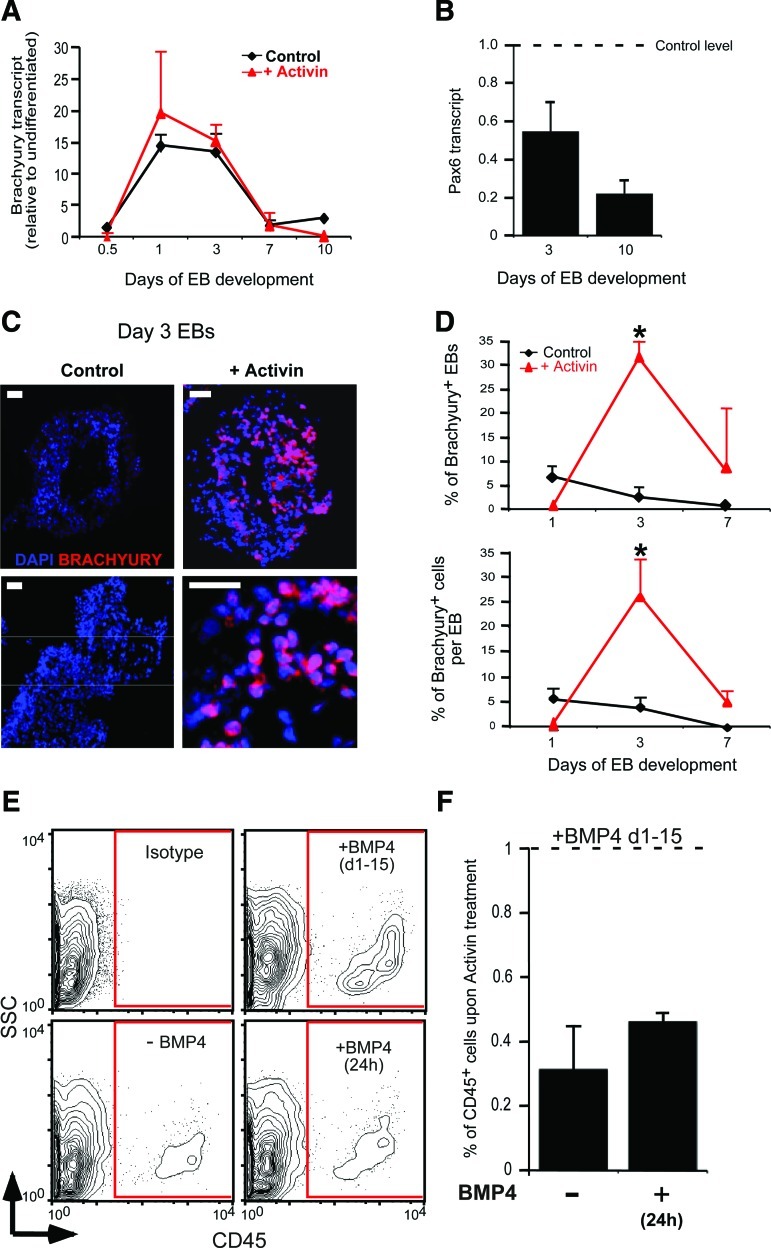

FIG. 3.

Activin A stimulates Brachyury levels in early hematopoiesis. (A) No significant change in the expression of Brachyury mRNA quantified by qPCR between Activin A and control treatment up to 10 days of EB development. (B) Decreased expression of the neuroectodermal marker Pax6 at days 3 and 7 of EB development in Activin A versus control EBs (shown as a horizontal line). (C) Representative immunocytochemistry of EB sections stained for Brachyury (red) relative to DAPI at day 3 of differentiation showing a large increase in Brachyury-positive nuclei in Activin A versus control-treated EBs (scale bars=50 μm). (D) Higher percentage of EBs (upper panel) and of cells per EB (lower panel) staining positive for Brachyury in Activin A versus control-treated EBs at day 3. (E, F) The flow analysis for CD45+ cells in EBs treated with or without BMP4 for the indicated time points demonstrating increased hematopoiesis with constitutive BMP4 treatment only. Bars for all panels indicate mean±SEM (*P<0.05). DAPI, 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Given the observed increase in Brachyury transcript at day 1 of EB differentiation (Fig. 3A), we undertook a histological evaluation of numbers and topography of Brachyury-positive cells (protein expressing) in sectioned human EBs at days 3 and 7 grown in the presence and absence of Activin A along with SF (Fig. 3C, D).

This analysis revealed that 7.5% of control EBs were positive for Brachyury as early as day 1 of differentiation. This declined to 3% at day 3 (Fig. 3D) and reached zero by day 10. Although none of the Activin A-treated EBs stained positively for Brachyury at day 1, the percentage of Brachyury-positive EBs rose sharply to 33% at day 3, then dropped to 7.5% at day 7 (Fig. 3D) and was undetectable by day 10. Examining fluorescent cell numbers within the EBs, Activin A markedly increased the frequency of Brachyury-positive cells compared to nontreated (26% vs. 4% at day 3; Fig. 3D lower panel). Somewhat surprising, however, was the observation that the upregulation of Brachyury by Activin A required the presence of the hematopoietic growth factors SF. Indeed, Brachyury was undetectable in EBs that underwent a paired treatment that included Activin A, but excluded SF (0/9) at day 3 of EB development, compared to the matching group where SF were added (7/17).

As stated previously, all EB culture experiments have included BMP4. Thus, testing the removal of BMP4 from the culture conditions would indicate if Activin A alone was able to induce hematopoiesis. This analysis revealed that removal of BMP4 from EB cultures significantly diminished (≥2-fold) the ability of Activin A to induce definitive hematopoietic (CD45+) cells (Fig. 3E). A rescue experiment, where BMP4 was added for 24 h, was also ineffective in stimulating mature CD45+ cell numbers (Fig. 3E, F). Therefore, BMP4, along with SF, are essential cofactors required for Activin A to induce blood in the human. These findings indicate that Activin A has the ability to upregulate the expression of Brachyury, but can increase hematopoietic potential only in permissive conditions that include the presence of cofactors such as SCF, Flt3L, and BMP4.

Brachyury is required for hematopoietic differentiation of hESCs

Brachyury is considered as the de facto marker of mesodermal differentiation [50]. However, whether Brachyury is required for blood development following mesoderm specification in humans is unknown. Only 2 studies using mouse ESCs have functionally connected the expression of Brachyury to the paraxial mesoderm [7] and primitive hematopoietic and EC differentiation [51]. To establish a connection between the upregulation of Brachyury and hematopoietic induction by Activin A revealed here, we chose constitutive mis-expression and loss-of-function approaches using lentiviral vectors and siRNAs, respectively.

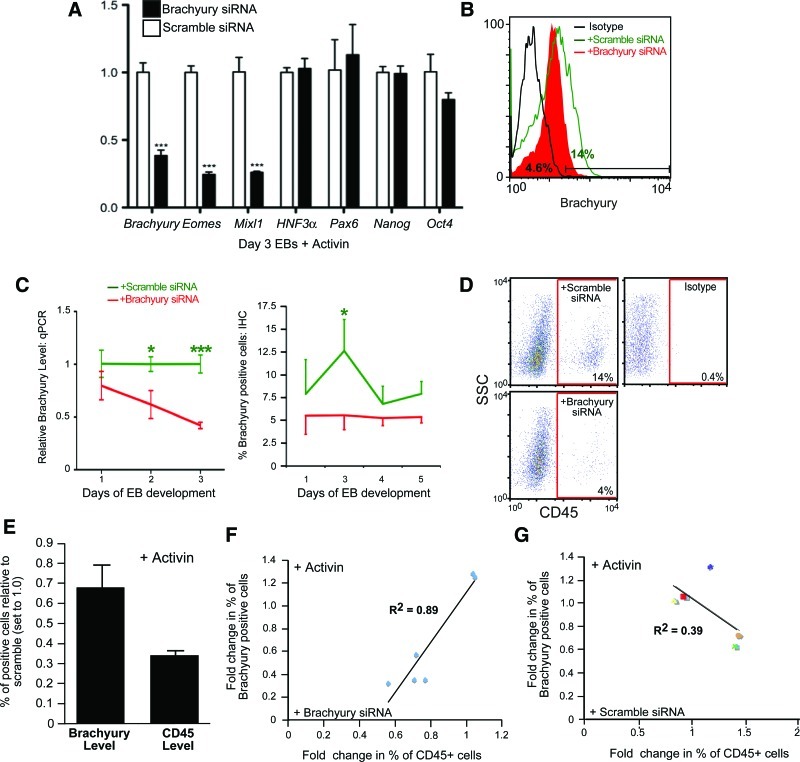

For loss-of-function experiments, EBs were transfected with Brachyury or scramble siRNA vectors at day 1 of EB formation and monitored for the expression of Brachyury (by qPCR and Flow Cytometry analysis) and for hematopoietic output at days 3 and 15. Compared to scramble siRNA, Brachyury siRNA caused a significant reduction in the levels of its own transcript as well as that of Eomes and Mixl1, but had no effect on levels of HNF3α, Pax6, Nanog, or Oct4 (Fig. 4A). In addition, a similar 3-fold reduction in the Brachyury transcript and protein was detected by qPCR and intracellular flow cytometry, respectively (Fig. 4B, C). This reduction was followed by a 3-fold decrease in the frequency of definitive CD45+ blood cells (Fig. 4D, E) In addition to mature blood levels, there was an observed effect of Brachyury knockdown on CD45negPFV progenitors as well (Supplementary Fig. S4). Further, using the linear regression analysis, we examined the correlation between the concomitant decrease in the frequency of Brachyury and CD45+ cells post-transfection with Brachyury or scramble siRNAs. A strong correlation was observed between the 2 parameters after treatment with Brachyury (R2=0.89), but not scramble (R2=0.39) siRNAs (Fig. 4F, G).

FIG. 4.

Knockdown of Brachyury decreases levels of CD45+ cells. (A) Transcript levels measured by qPCR at day 3 of human EB differentiation in the presence of Activin A (n=3). (B) The representative intracellular flow cytometry analysis of Brachyury showing the decrease in the frequency of Brachyury-positive cells post-EB transfection with Brachyury siRNA (4.6%) (solid red) compared to scramble siRNAs (14%) (green line). (C) Relative expression of Brachyury transcript (left, n=3) and frequency of Brachyury-positive cells measured by flow cytometry (right, n=5) at the indicated time points post-EB transfection with Brachyury (red) or scramble (green) siRNAs. (D) Representative flow cytometry showing percentage of CD45+ cells at day 15 of EB differentiation treated with Activin A in the presence of Brachyury or scramble siRNAs. (E) Comparison of the fold reduction in the frequency of Brachyury- and CD45-positive cells measured in day 3 EBs for Brachyury and day 15–22 EBs for CD45 post-transfection with Brachyury compared to scramble siRNAs (n=3). (F, G) The linear regression analysis of the previous 2 parameters post-transfection with Brachyury (F) and scramble (G) siRNAs. Bars for all panels show mean values±SEM (*P<0.05, ***P<0.001). siRNA, small interfering RNA. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Lastly, constitutive mis-expression of Brachyury using lentiviral transduction was used to determine if this factor was able to augment the hematopoietic program of hESCs. Forced expression of Brachyury was unable to augment numbers of definitive CD45+ blood cells, indicating that increasing levels of Brachyury does not have a significant impact on the generation of hematopoietic fated cells (Fig. 5). Conversely, it was observed that transduced cells, evaluated based on GFP positivity, were refractory to hematopoietic differentiation based on the lack of GFP, CD45 double-positive cells (Fig. 5C). This observation corroborates previous studies in mice using a GFP reporter of Brachyury, which indicated that cells expressing the highest levels of Brachyury during gastrulation do not coexpress genes indicative of hematopoietic induction [17].

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that Activin A signaling promotes the upregulation of Brachyury in hESCs, confirming the role of this pathway in the early differentiation toward mesoderm in a human system. Furthermore, by targeting Brachyury expression, we demonstrate that Brachyury is a downstream target of Activin A-induced hematopoiesis.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates the requirement of hESC progression through a primitive mesodermal intermediate in hematopoietic differentiation, which is stimulated by the presence of low-dose Activin A and is Brachyury positive, for the first time in a human system. By sequential introduction of mesodermal (bFGF and Activin A) and hematopoietic (SCF and Flt3L) growth factor combinations to EB cultures and downregulation of the mesodermal factor Brachyury by siRNA, we have shown the ability of Activin A, in conjunction with hematopoietic growth factors, to promote Brachyury-dependent mesodermal induction of hematopoietic differentiation in hESCs. This study also reveals that exogenous bFGF is dispensable for this system of induction, consistent with its role in maintaining pluripotency rather than stimulating differentiation [20,52].

For the first time in a human system, the effects of both the gain and loss of the function of Brachyury have been determined here. By constitutively overexpressing Brachyury in hEBs, we have been able to observe that levels of CD45+ cells remained unaffected. In contrast, downregulation of Brachyury achieved via siRNA resulted in decreased hematopoietic output. Previous studies examining the effects of Brachyury overexpression in amphibians demonstrated that the Xbra mRNA injection led to the development of ectopic mesoderm [53], yet conclusive evidence linking increased Brachyury levels to increased hematopoietic output have not surfaced. As such, our study demonstrates for the first time that increasing the level of Brachyury would appear ineffective at promoting hematopoiesis. However, we have shown that reducing levels of Brachyury using siRNA has adverse effects on hematopoietic output in hESCs.

In mouse ESCs, both AF have been described as key players in the development of the hematopoietic mesoderm [54–58]. However, aside from BMP4, whose contribution to the formation of hematopoietic mesoderm has been demonstrated [37–39], the role of Activin A in early hESC fate decisions has been considerably less explored, apart from one recent study, which causally links endogenous high levels of Activin/Nodal signaling in various hESC lines to their augmented hematopoietic generation, and that further validated this link by specific activation (with Activin-A) and chemical inhibition (using SB-431542) in vitro [59]. In particular, little focus has been directed to studying mesoderm specification in hESCs, but recent studies from our laboratory have employed the same hematopoietic EB differentiation studies as currently used to identify factors driving differentiation [13,60]. In this context, the present study reveals the importance of Activin A in the induction of Brachyury as part of a global developmental program that is amplified during hematopoietic differentiation in hESCs. In contrast to other developmental pathways [13], continual treatment with Activin A did not compromise, but instead increased the hematopoietic potential of hESCs.

Furthermore, our results underscore the temporal regulation of Activin A toward mesodermal development and subsequent hematopoietic development of hESCs by distinct mechanisms. Similar to previous studies in the mouse, a tight cross-talk between Activin A and BMP4 appeared to be essential in the differentiation program of hESCs from mesoderm to blood, with less expression of Brachyury and a reduced hematopoietic output in the absence of either of these factors. Our study suggests that primitive streak/mesoderm-associated gene expression and hematopoietic development are regulated, at least partly, by the integration of the BMP and Activin signaling pathways, which is consistent with the in vivo requirement of multiple factors for germ layer induction and hematopoietic development. It will be important to evaluate the precise contribution of these differentiation factors and signaling pathways in the evolution toward a better control of lineage specification with the ultimate goal of cell replacement therapies that require alternative sources of hematopoietic cell types [61,62].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Borhane Guezguez and Dr. Eva Szabo for providing critical comments on the article and all of the members of the Bhatia laboratory for valuable discussions. We thank Dr. Tony Collins for assistance with the statistical analysis of our data. Funding for this research was provided by a research grant from a Canada Research Chair in Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR) to M.B.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Smith JC. Price BM. Green JB. Weigel D. Herrmann BG. Expression of a Xenopus homolog of Brachyury (T) is an immediate-early response to mesoderm induction. Cell. 1991;67:79–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90573-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulte-Merker S. van Eeden FJ. Halpern ME. Kimmel CB. Nusslein-Volhard C. no tail (ntl) is the zebrafish homologue of the mouse T (Brachyury) gene. Development. 1994;120:1009–1015. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kispert A. Ortner H. Cooke J. Herrmann BG. The chick Brachyury gene: developmental expression pattern and response to axial induction by localized activin. Dev Biol. 1995;168:406–415. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrmann BG. Labeit S. Poustka A. King TR. Lehrach H. Cloning of the T gene required in mesoderm formation in the mouse. Nature. 1990;343:617–622. doi: 10.1038/343617a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huber TL. Zhou Y. Mead PE. Zon LI. Cooperative effects of growth factors involved in the induction of hematopoietic mesoderm. Blood. 1998;92:4128–4137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacaud G. Keller G. Kouskoff V. Tracking mesoderm formation and specification to the hemangioblast in vitro. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14:314–317. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Izumi N. Era T. Akimaru H. Yasunaga M. Nishikawa S. Dissecting the molecular hierarchy for mesendoderm differentiation through a combination of embryonic stem cell culture and RNA interference. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1664–1674. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnerch A. Cerdan C. Bhatia M. Distinguishing between mouse and human pluripotent stem cell regulation: the best laid plans of mice and men. Stem Cells. 2010;28:419–430. doi: 10.1002/stem.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chadwick K. Wang L. Li L. Menendez P. Murdoch B. Rouleau A. Bhatia M. Cytokines and BMP-4 promote hematopoietic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Blood. 2003;102:906–915. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerdan C. Rouleau A. Bhatia M. VEGF-A165 augments erythropoietic development from human embryonic stem cells. Blood. 2004;103:2504–2512. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L. Menendez P. Cerdan C. Bhatia M. Hematopoietic development from human embryonic stem cell lines. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:987–996. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L. Li L. Shojaei F. Levac K. Cerdan C. Menendez P. Martin T. Rouleau A. Bhatia M. Endothelial and hematopoietic cell fate of human embryonic stem cells originates from primitive endothelium with hemangioblastic properties. Immunity. 2004;21:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vijayaragavan K. Szabo E. Bosse M. Ramos-Mejia V. Moon RT. Bhatia M. Noncanonical Wnt signaling orchestrates early developmental events toward hematopoietic cell fate from human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:248–262. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zambidis ET. Peault B. Park TS. Bunz F. Civin CI. Hematopoietic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells progresses through sequential hematoendothelial, primitive, and definitive stages resembling human yolk sac development. Blood. 2005;106:860–870. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fehling HJ. Lacaud G. Kubo A. Kennedy M. Robertson S. Keller G. Kouskoff V. Tracking mesoderm induction and its specification to the hemangioblast during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Development. 2003;130:4217–4227. doi: 10.1242/dev.00589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tian X. Kaufman DS. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells towards hematopoietic cells: progress and pitfalls. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008;15:312–318. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328302f429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber TL. Kouskoff V. Fehling HJ. Palis J. Keller G. Haemangioblast commitment is initiated in the primitive streak of the mouse embryo. Nature. 2004;432:625–630. doi: 10.1038/nature03122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lancrin C. Sroczynska P. Stephenson C. Allen T. Kouskoff V. Lacaud G. The haemangioblast generates haematopoietic cells through a haemogenic endothelium stage. Nature. 2009;457:892–895. doi: 10.1038/nature07679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith JC. Cunliffe V. Green JB. New HV. Intercellular signalling in mesoderm formation during amphibian development. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1993;340:287–296. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1993.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bendall SC. Stewart MH. Menendez P. George D. Vijayaragavan K. Werbowetski-Ogilvie T. Ramos-Mejia V. Rouleau A. Yang J, et al. IGF and FGF cooperatively establish the regulatory stem cell niche of pluripotent human cells in vitro. Nature. 2007;448:1015–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature06027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vallier L. Alexander M. Pedersen RA. Activin/Nodal and FGF pathways cooperate to maintain pluripotency of human embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4495–4509. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kubo A. Shinozaki K. Shannon JM. Kouskoff V. Kennedy M. Woo S. Fehling HJ. Keller G. Development of definitive endoderm from embryonic stem cells in culture. Development. 2004;131:1651–1662. doi: 10.1242/dev.01044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Amour KA. Agulnick AD. Eliazer S. Kelly OG. Kroon E. Baetge EE. Efficient differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to definitive endoderm. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1534–1541. doi: 10.1038/nbt1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLean AB. D'Amour KA. Jones KL. Krishnamoorthy M. Kulik MJ. Reynolds DM. Sheppard AM. Liu H. Xu Y. Baetge EE. Dalton S. Activin a efficiently specifies definitive endoderm from human embryonic stem cells only when phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling is suppressed. Stem Cells. 2007;25:29–38. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hay DC. Fletcher J. Payne C. Terrace JD. Gallagher RC. Snoeys J. Black JR. Wojtacha D. Samuel K, et al. Highly efficient differentiation of hESCs to functional hepatic endoderm requires ActivinA and Wnt3a signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12301–12306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806522105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sulzbacher S. Schroeder IS. Truong TT. Wobus AM. Activin A-induced differentiation of embryonic stem cells into endoderm and pancreatic progenitors-the influence of differentiation factors and culture conditions. Stem Cell Rev. 2009;5:159–173. doi: 10.1007/s12015-009-9061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernardo AS. Faial T. Gardner L. Niakan KK. Ortmann D. Senner CE. Callery EM. Trotter MW. Hemberger M, et al. BRACHYURY and CDX2 mediate BMP-induced differentiation of human and mouse pluripotent stem cells into embryonic and extraembryonic lineages. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shav-Tal Y. Zipori D. The role of activin a in regulation of hemopoiesis. Stem Cells. 2002;20:493–500. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.20-6-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allouche M. Bikfalvi A. The role of fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) in hematopoiesis. Prog Growth Factor Res. 1995;6:35–48. doi: 10.1016/0955-2235(95)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomson JA. Itskovitz-Eldor J. Shapiro SS. Waknitz MA. Swiergiel JJ. Marshall VS. Jones JM. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu C. Inokuma MS. Denham J. Golds K. Kundu P. Gold JD. Carpenter MK. Feeder-free growth of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:971–974. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong SH. Lee JH. Lee JB. Ji J. Bhatia M. ID1 and ID3 represent conserved negative regulators of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cell hematopoiesis. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:1445–1452. doi: 10.1242/jcs.077511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ben-Dor I. Itsykson P. Goldenberg D. Galun E. Reubinoff BE. Lentiviral vectors harboring a dual-gene system allow high and homogeneous transgene expression in selected polyclonal human embryonic stem cells. Mol Ther. 2006;14:255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Latinkic BV. Umbhauer M. Neal KA. Lerchner W. Smith JC. Cunliffe V. The Xenopus Brachyury promoter is activated by FGF and low concentrations of activin and suppressed by high concentrations of activin and by paired-type homeodomain proteins. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3265–3276. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.23.3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Symes K. Yordan C. Mercola M. Morphological differences in Xenopus embryonic mesodermal cells are specified as an early response to distinct threshold concentrations of activin. Development. 1994;120:2339–2346. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green JB. New HV. Smith JC. Responses of embryonic Xenopus cells to activin and FGF are separated by multiple dose thresholds and correspond to distinct axes of the mesoderm. Cell. 1992;71:731–739. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90550-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pick M. Azzola L. Mossman A. Stanley EG. Elefanty AG. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells in serum-free medium reveals distinct roles for bone morphogenetic protein 4, vascular endothelial growth factor, stem cell factor, and fibroblast growth factor 2 in hematopoiesis. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2206–2214. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang P. Li J. Tan Z. Wang C. Liu T. Chen L. Yong J. Jiang W. Sun X. Du L. Ding M. Deng H. Short-term BMP-4 treatment initiates mesoderm induction in human embryonic stem cells. Blood. 2008;111:1933–1941. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-074120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vallier L. Touboul T. Chng Z. Brimpari M. Hannan N. Millan E. Smithers LE. Trotter M. Rugg-Gunn P. Weber A. Pedersen RA. Early cell fate decisions of human embryonic stem cells and mouse epiblast stem cells are controlled by the same signalling pathways. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishikawa SI. Nishikawa S. Hirashima M. Matsuyoshi N. Kodama H. Progressive lineage analysis by cell sorting and culture identifies FLK1+VE-cadherin+ cells at a diverging point of endothelial and hemopoietic lineages. Development. 1998;125:1747–1757. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.9.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cornell RA. Musci TJ. Kimelman D. FGF is a prospective competence factor for early activin-type signals in Xenopus mesoderm induction. Development. 1995;121:2429–2437. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cornell RA. Kimelman D. Activin-mediated mesoderm induction requires FGF. Development. 1994;120:453–462. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.2.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willems E. Leyns L. Patterning of mouse embryonic stem cell-derived pan-mesoderm by Activin A/Nodal and Bmp4 signaling requires Fibroblast Growth Factor activity. Differentiation. 2008;76:745–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2007.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerdes J. Lemke H. Baisch H. Wacker HH. Schwab U. Stein H. Cell cycle analysis of a cell proliferation-associated human nuclear antigen defined by the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. J Immunol. 1984;133:1710–1715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamada G. Kioussi C. Schubert FR. Eto Y. Chowdhury K. Pituello F. Gruss P. Regulated expression of Brachyury(T), Nkx1.1 and Pax genes in embryoid bodies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:552–563. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Isaacs HV. Pownall ME. Slack JM. eFGF regulates Xbra expression during Xenopus gastrulation. EMBO J. 1994;13:4469–4481. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06769.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wardle FC. Smith JC. Refinement of gene expression patterns in the early Xenopus embryo. Development. 2004;131:4687–4696. doi: 10.1242/dev.01340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terzic J. Saraga-Babic M. Expression pattern of PAX3 and PAX6 genes during human embryogenesis. Int J Dev Biol. 1999;43:501–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith JR. Vallier L. Lupo G. Alexander M. Harris WA. Pedersen RA. Inhibition of Activin/Nodal signaling promotes specification of human embryonic stem cells into neuroectoderm. Dev Biol. 2008;313:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kavka AI. Green JB. Tales of tails: Brachyury and the T- box genes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1333:F73–F84. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(97)00016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Era T. Izumi N. Hayashi M. Tada S. Nishikawa S. Multiple mesoderm subsets give rise to endothelial cells, whereas hematopoietic cells are differentiated only from a restricted subset in embryonic stem cell differentiation culture. Stem Cells. 2008;26:401–411. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eiselleova L. Matulka K. Kriz V. Kunova M. Schmidtova Z. Neradil J. Tichy B. Dvorakova D. Pospisilova S. Hampl A. Dvorak P. A complex role for FGF-2 in self-renewal, survival, and adhesion of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1847–1857. doi: 10.1002/stem.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cunliffe V. Smith JC. Ectopic mesoderm formation in Xenopus embryos caused by widespread expression of a Brachyury homologue. Nature. 1992;358:427–430. doi: 10.1038/358427a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nostro MC. Cheng X. Keller GM. Gadue P. Wnt, activin, and BMP signaling regulate distinct stages in the developmental pathway from embryonic stem cells to blood. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Faloon P. Arentson E. Kazarov A. Deng CX. Porcher C. Orkin S. Choi K. Basic fibroblast growth factor positively regulates hematopoietic development. Development. 2000;127:1931–1941. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.9.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gadue P. Huber TL. Nostro MC. Kattman S. Keller GM. Germ layer induction from embryonic stem cells. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:955–964. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pearson S. Sroczynska P. Lacaud G. Kouskoff V. The stepwise specification of embryonic stem cells to hematopoietic fate is driven by sequential exposure to Bmp4, activin A, bFGF and VEGF. Development. 2008;135:1525–1535. doi: 10.1242/dev.011767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Irion S. Clarke RL. Luche H. Kim I. Morrison SJ. Fehling HJ. Keller GM. Temporal specification of blood progenitors from mouse embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. Development. 2010;137:2829–2839. doi: 10.1242/dev.042119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramos-Mejia V. Melen GJ. Sanchez L. Gutierrez-Aranda I. Ligero G. Cortes JL. Real PJ. Bueno C. Menendez P. Nodal/Activin signaling predicts human pluripotent stem cell lines prone to differentiate toward the hematopoietic lineage. Mol Ther. 2010;18:2173–2181. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hong SH. Rampalli S. Lee JB. McNicol J. Collins T. Draper JS. Bhatia M. Cell fate potential of human pluripotent stem cells is encoded by histone modifications. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guezguez B. Bhatia M. Transplantation of human hematopoietic repopulating cells: mechanisms of regeneration and differentiation using human-mouse xenografts. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2008;13:44–52. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3282f42486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bhatia M. Hematopoietic development from human embryonic stem cells. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2007:11–16. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.