Abstract

Objectives

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (US) and targeted microbubbles have been shown to be advantageous for angiogenesis evaluation and disease staging in cancer. This study explored molecular US imaging of a multitargeted microbubble for assessing the early tumor response to antiangiogenic therapy.

Methods

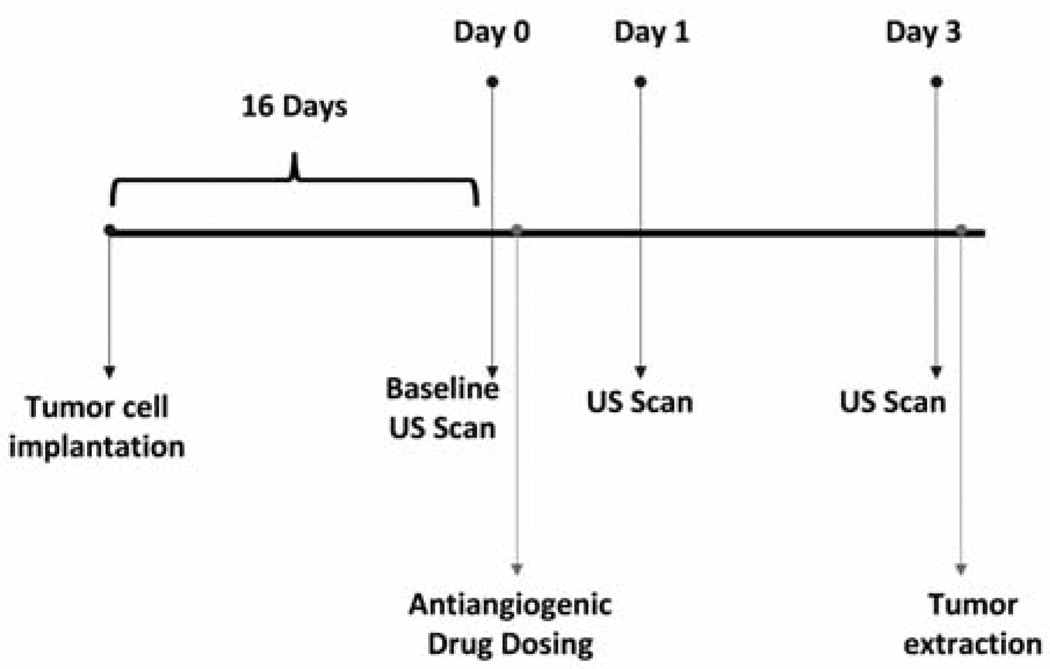

Target receptor expression of 2LMP breast cancer cells was quantified by flow cytometric analysis and characterization established with antibodies against mouse αvβ3-integrin, P-selectin, and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2. Tumor-bearing mice (n = 15 per group) underwent contrast-enhanced US imaging of multitargeted microbubbles. Microbubble accumulation was calculated by destruction-replenishment techniques and time-intensity curve analysis. On day 0, mice underwent baseline imaging. Next, therapy group mice were injected with a 0.2-mg dose of bevacizumab, and controls received matched saline injections. Imaging was repeated on days 1 and 3. After imaging was completed on day 3, the mice were euthanized and tumors excised. Histologic analysis of microvessel density and intratumoral necrosis was completed on tumor sections.

Results

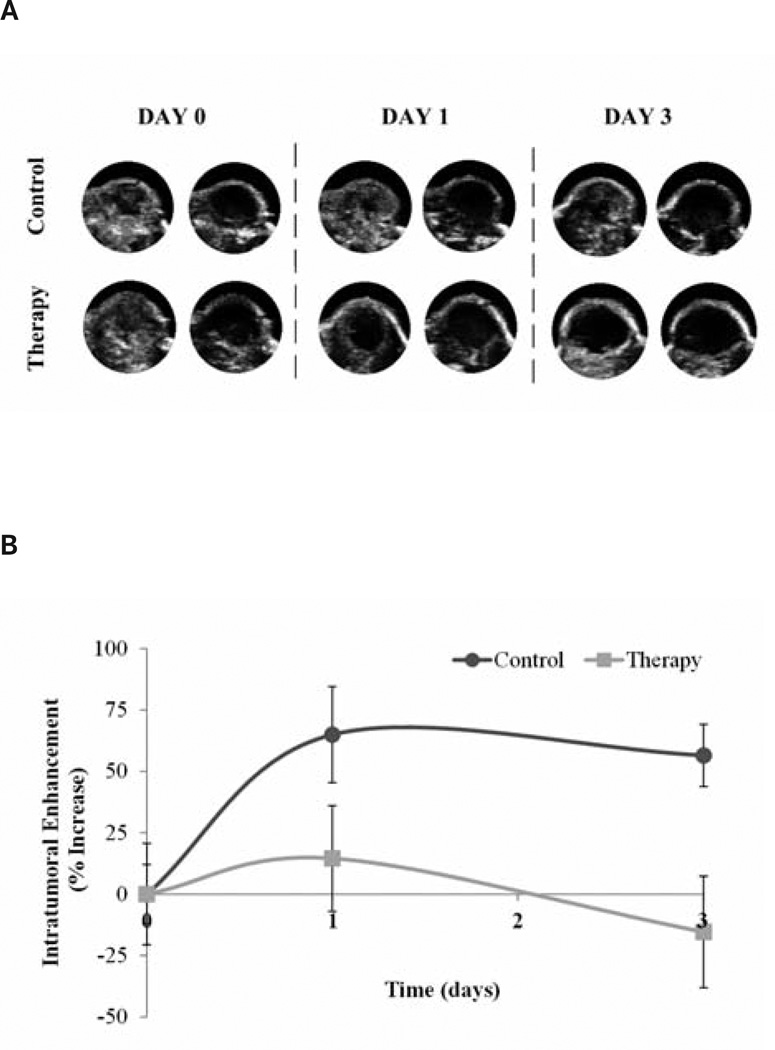

On day 3 after bevacizumab dosing, a 71.8% change in tumor vasculature was shown between the therapy and control groups (P = .01). The therapy group had a 15.4% decrease in tumor vascularity, whereas the control group had a 56.4% increase.

Conclusions

Molecular US imaging of angiogenic markers can detect the early tumor response to drug therapy.

Keywords: angiogenesis, antiangiogenic therapy, contrast-enhanced ultrasound, microbubbles, targeted contrast agent

Cancer accounts for nearly 1 in every 4 deaths in the United States and affects nearly 12 million people.1 Cancerous masses, or tumors, cannot survive in the body beyond 1 to 2 mm unless they are vascularized.2,3 Angiogenesis, the development of new capillary blood vessels, has been shown to be directly associated with malignancy and is necessary for cancer to survive and progress.

Proper staging of cancer is critical in determining the appropriate method of therapy as well as accurately assessing prognosis. Drug treatments for cancer encompass two main categories: antimitotic and targeted. Antimitotic drugs, or chemotherapeutics, act by killing cells that are rapidly dividing. Targeted therapy, most commonly associated with antibody therapy, is more specific and uses monoclonal antibodies to target malignant cells. Antiangiogenic drugs, such as bevacizumab, are targeted vascular-disrupting agents that attempt to stop new blood vessel formation and may stop or retard the growth and spread of tumors. These antiangiogenic therapies have been used clinically in conjunction with chemotherapy to help treat cancer such as colon, breast, lung, and brain cancer.4 Specifically, bevacizumab has been proven in preclinical animal models to be effective within 7 days of treatment on both magnetic resonance5 and ultrasound (US)6,7 imaging.

Ultrasound contrast agents are subcapillary-sized, gas-filled microbubbles small enough to pass through microvasculature.8,9 Contrast-enhanced US is the application of microbubbles to traditional US imaging, originally designed to improve visualization of echocardiograms.10 Contrast-enhanced US imaging has since been explored for numerous preclinical and clinical opportunities, such as detection and cancer staging. Other applications of microbubbles currently being explored include increasing drug delivery through microbubble-mediated US therapy and evaluation of the tumor response to therapy.11–13 Different cancers and their endothelial cells overexpress certain receptor proteins, which allows the application of microbubbles to be expanded to include the use of tumor vasculature marker targeting to provide added visualization of angiogenesis and vessel assessment.14–17 Molecular US imaging includes active microbubble targeting to single or multiple receptors to provide additional enhanced visualization for cancer detection, disease staging, or receptor profile analysis.15,18–20 A triple-targeted microbubble allows increased visualization of angiogenesis through increased receptor binding.13 Targeting microbubbles to P-selectin, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), and αvβ3-integrin angiogenic molecular markers has been shownto effectively increase visualization of tumor vasculature by 60% over single-targeted strategies and 40% of dualtargeted strategies in preclinical breast cancer models.13 Other groups have also shown the advantages of using targeted microbubble strategies through enhanced visualization and assessment of tumor vascularity compared to traditional contrast-enhanced US.21–23 Molecular US imaging has potential to be used to develop targeted personalized diagnostics and therapy.24 In this study, we explored molecular US imaging of a triple-targeted microbubble for assessing the early tumor response to antiangiogenic therapy.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Human 2LMP breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231, lung metastatic pooled) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% l-glutamine. All cells were cultured to 70% to 90% confluence before passaging. Cells were grown at 37°C in 5% carbon dioxide and 90% relative humidity. Appropriate cell numbers for all experiments were determined with a hemocytometer and trypan blue dye exclusion.

In Vitro Characterization

Mouse angiosarcoma (SVR) endothelial cells were aliquoted (25 × 104 cells per tube) and stained with primary antibodies against mouse αvβ3-integrin, P-selectin, or VEGFR2 per the manufacturer’s recommendations. Phycoerythrin-labeled anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (405406; BioLegend, San Diego, CA) was used as a secondary stain. Tubes with cells and the secondary antibody alone were used as controls to establish a background signal. Cells were analyzed for fluorescent counts (50 × 103 events) using flow cytometry (Accuri C6; Accuri Cytometers, Inc, Ann Arbor, MI). All experimental groups were analyzed in triplicate.

Animal Preparation

Animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Thirty 6-week-old nude female athymic mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were implanted subcutaneously with 2 × 106 2LMP cells in the left flank. Implanted tumors were allowed to grow 16 days before experimental studies began (average tumor size, 130.9 ± 7.4 mm3). The mice were then sorted by tumor size into two groups; therefore, each group created had approximately the same average-size tumors to ensure no biasing between groups (P = .74). The tumor area was calculated by a standard ellipse equation with the transverse and longitudinal caliper measurements.

Antibody-Microbubble Conjugation

Streptavidin-coated microbubbles (Targestar-SA, San Diego, CA) were conjugated to biotinylated rat immunoglobulin G antibodies against αvβ3-integrin (13-0512; eBioscience, San Diego, CA), P-selectin (16-0622; eBioscience), and VEGFR2 (13-6410; BioLegend). These microbubbles are lipid-coated perfluorocarbon microspheres averaging 2.5 µm. Their lipid shell is coated with streptavidin conjugated to the distal tip of the polymeric spacer. Multitargeted microbubbles were prepared by incubating the streptavidin-coated microbubbles with equal amounts (20 µg) of each respective antibody for 20 minutes.13 Antibody-labeled microbubbles were washed in a centrifuge (400g) for 3 minutes to wash any unbound antibody. The microbubbles were diluted with phosphate-buffered saline to a total volume of 1 mL, and the final concentration was characterized with a hemocytometer. A new vial of multitargeted microbubbles was prepared each day to ensure consistency across the microbubble population. Microbubbles were between 1 and 8 µm, averaging 2 µm.

Treatment

Bevacizumab (Avastin; Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) treatment was given to the treatment group after baseline molecular US imaging on day 0. Bevacizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody to VEGF. This drug functions by blocking the VEGF protein, thereby breaking down current permeability and vascularity while inhibiting the formation of blood vessel growth.25–27 Other antiangiogenesis-inhibiting drugs include sorafenib, sunitinib, and pazopanib.4 Mice were administered 0.2 mg (25 mg/mL) of bevacizumab diluted with saline to 100 µL via intraperitoneal injection. Control mice received a 100-µL matched intraperitoneal dose of saline.

Imaging

Molecular US imaging was performed on days 0, 1, and 3. The mice were weighed before each imaging session. For the US imaging, each mouse was anesthetized with isoflurane gas. Gray-scale US imaging was performed with a Sonix RP research scanner (Ultrasonix Medical Corp, Richmond, British Columbia, Canada) equipped with a 7-MHz linear array transducer and a pulse-inversion harmonic imaging feature. Targeted microbubbles (60 µL, 14 × 106 microbubbles/mL) were diluted to 100 µL with saline and intravenously injected through the tail vein. The mice were submerged in a custom-built 37°C water bath and remained under isoflurane gas anesthesia for the entirety of theUSimaging. A 2-minute waiting period after injection ensured adequate systemic circulation and binding of microbubbles to their target angiogenic molecular markers.

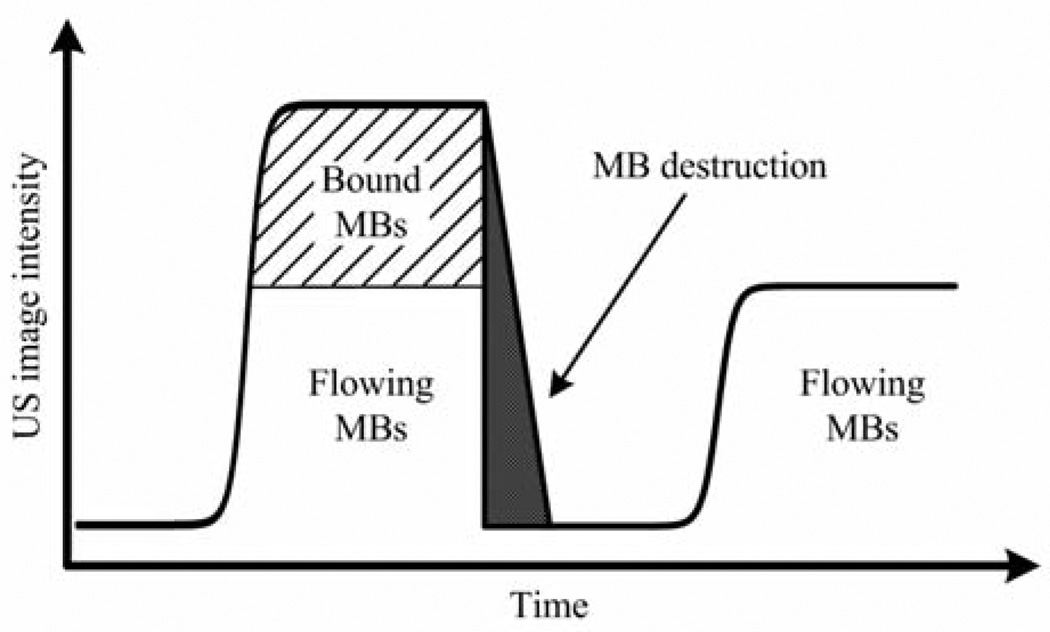

The largest cross section of each tumor was identified and used as the imaging plane between days for consistency throughout the study. After the post–microbubble injection delay, tumors were imaged at a low mechanical index value of 0.1 for 10 seconds to capture both bound and systemically flowing microbubbles in the image plane. Subsequently, a high-intensity microbubble destruction pulse sequence (mechanical index of 1.2, 4 seconds) was applied to destroy all microbubbles within the imaging plane. Low-intensity US imaging was then performed again for 20 seconds to capture tumor reperfusion of the microbubble agents (Figure 1). The imaging sequence was saved for offline processing. Figure 2 shows the experimental time line of tumor implantation, treatment, and imaging.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound setup using a combination microbubble (MB) perfusion-destruction technique to analyze the amount of bound microbubbles within the tumor, allowing noninvasive detection of tumor angiogenesis and vascularity.

Figure 2.

Time line showing experimental processes of tumor implantation, antiangiogenic drug dosing, and multitargeted contrast-enhanced US imaging.

Data Analysis

Molecular US images were processed with custom MATLAB programs (The Math Works, Natick, MA) to evaluate time-intensity curve information. The first image that followed the 2 minutes after microbubble injection (before the microbubble destruction pulse sequence) was used for each mouse to analyze bound microbubbles in the tumor vasculature. The last image of the second US imaging sequence (after the microbubble destruction pulse sequence) was used as a baseline image to calculate all circulating microbubbles and possible tissue reflection/artifacts.

Images were saved in their 32-bit postscan converted format and uploaded into MATLAB for analysis. Each image sequence was registered, and the same region of interest was used for both images to ensure proper subtraction of image sequences. After placement of a circular region of interest to encompass intratumoral vascularity, the pixel intensity was measured from both images (one before and one after the microbubble destruction pulse sequence as described previously). The pixel intensity was calculated for both images by analyzing brightness on a gray-scale. Image 2 (after microbubble destruction) was subtracted from image 1 (before microbubble destruction) to calculate the intensity from the bound microbubbles. The difference between these two mean region of interest values is a surrogate measure of successfully targeted and bound microbubble populations. This procedure was repeated for each mouse on each day of imaging.

Histologic Analysis

After experimentation on day 3, all animals were humanely euthanized, and tumors were excised. Samples were sliced at the largest cross-sectional diameter (to approximate the US imaging plane), and sections were stained for hematoxylin-eosin and CD31. Hematoxylin-eosin sections were examined for cellular necrosis and reported as the percentage of the entire tumor cross section (original magnification ×5). CD31-stained histologic slides were examined (original magnification ×40) to identify 5 separate areas containing the greatest microvessel density. Individual vessels from these 5 areas were counted (original magnification ×200), averaged, and recorded as the microvessel density.

Statistical Analysis

Data were summarized as mean ± standard error. Analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (SAS Inc, Cary, NC). Assessment of intergroup comparison of in vitro data was completed with the analysis of variance test. Analysis of in vivo experimental data was performed with a 2-sample independent t test. Changes in the tumor size and mouse weight were compared between groups with a 2-sample independent t test.

Results

In Vitro Characterization

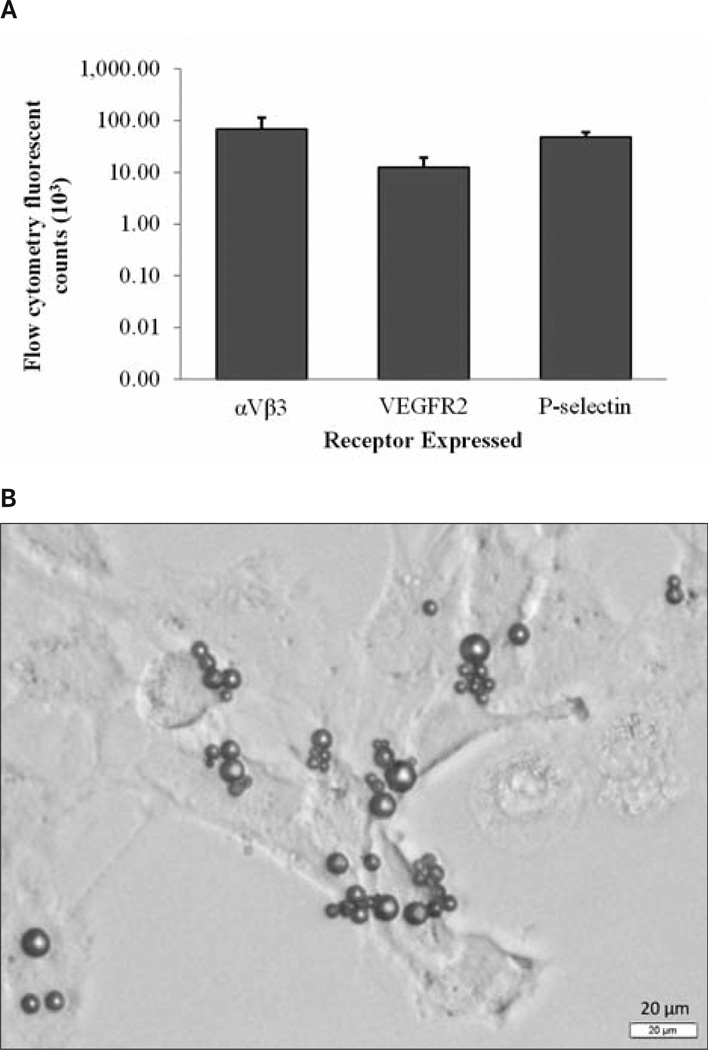

The normalized (background-subtracted) fluorescent counts from this study are shown in Figure 3. Receptor expression in mouse SRV cells was confirmed for each of the receptors targeted: αvβ3-integrin, VEGFR2, and P-selectin. Receptor expression calculated in vitro by flow cytometry varied between the 3 receptors targeted, with VEGFR2 significantly decreased in comparison to its other constituents (P < .01). Although significantly different, all receptors were expressed within the murine SRV cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A, In vitro results showing receptor characterization and expression as flow cytometric mean fluorescent counts. B, Representative microscopic image of multitargeted microbubbles attached to SVR cells.

In Vivo Characterization

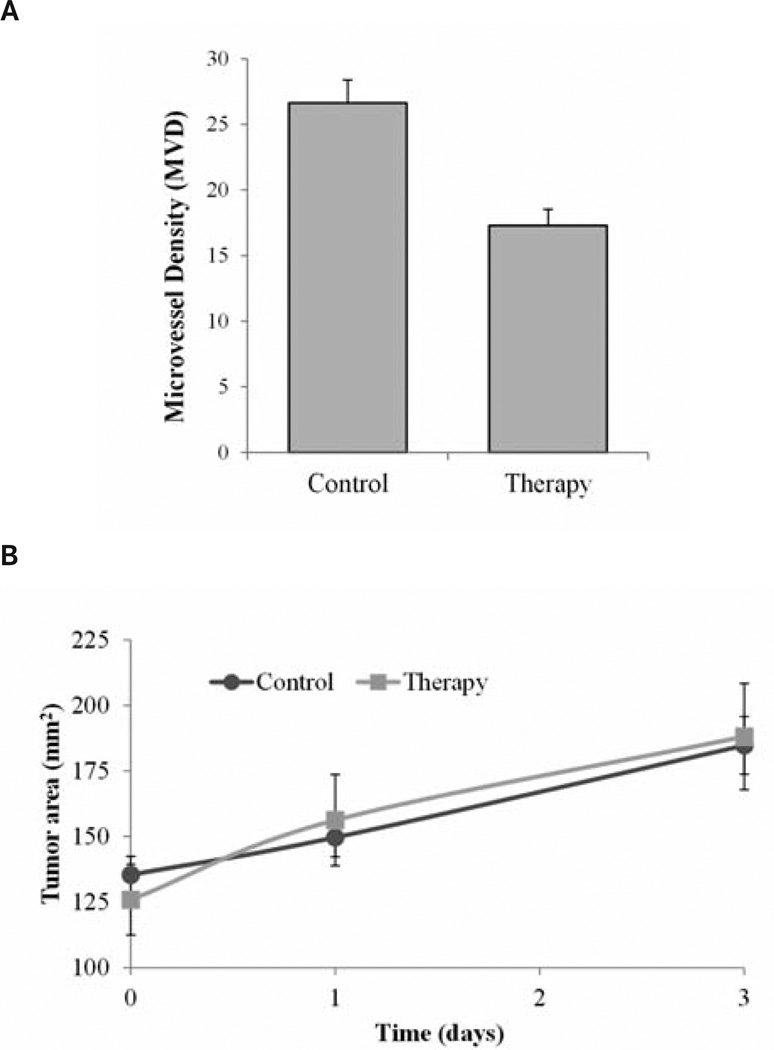

There were no differences between control and therapy group animal weights on day 0 (P = .63) or day 3 (P = .97). Marked changes in weight loss or gain can be an indication of declining animal health. Analysis of tumor size data indicated no differences between the groups on day 0 (P = .66) or day 3 (P = .89; Figure 4). On day 0, baseline molecular US imaging results showed no differences in tumor perfusion between control and therapy group mice (P = .08). However, imaging results collected on day 1 after therapeutic dosing revealed a −50.4% change in intratumoral perfusion between therapy and control groups (P = .09) with the control and therapy group tumors showing 64.9% and 14.5% increases, respectively, from baseline measurements. Day 3 imaging results revealed a 71.8% difference between therapy and control group data (P = .01), with control and therapy tumors showing perfusion changes of 56.4% and −15.4%, respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

A, Histologic results showing significant decreases in microvessel density in therapy mice receiving the antiangiogenic drug compared to control mice receiving saline (P < .01). B, No significant differences were seen in tumor size from day 0 to day 3 in the control and treatment groups(P = .89), indicating that US detection of the early tumor response occurred before the tumor size could indicate a response.

Figure 5.

Intratumoral perfusion, calculated by the microbubble perfusion-destruction technique, was seen to decrease in the treatment group receiving antiangiogenic drugs compared to the control group. A, Representative multitargeted contrast-enhanced US images before and after microbubble destruction from 1 mouse per group in the control and therapy groups on days 0, 1, and 3. B, Percent change in intratumoral enhancement. On day 3 the therapy group showed a 71.8% decrease in intratumoral enhancement compared to the controls (P = .01).

Histologic Analysis

Histologic analysis indicated that there were no significant differences in the percentage of necrosis between therapy and control group samples (P = .15). A comparison of CD31 section data revealed differences in terminal microvessel density for the control and therapy tumor samples: 26.6 and 17.3 counts, respectively (P < .01; Figure 4).

Discussion

In this experiment, multitargeted microbubbles were used to evaluate and assess the early response to antiangiogenic treatment in breast cancer–bearing mice. Within 1 day of administering bevacizumab, decreased tumor vascularity was observed in the therapeutic animal group compared to the controls. By day 3, molecular US imaging of these same angiogenic markers detected a further decrease in tumor vascularity, as determined by a significant reduction in targeted microbubble accumulation (compared to control data).

Kim et al5 used a dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging approach to assess the early response to antiangiogenic therapy by evaluating pharmokinetic parameters through calculating transfer of the contrast agent from the vascular space, yielding a surrogate measure of tumor perfusion. That study showed a decrease in intratumoral perfusion on day 3 after therapy when treated with bevacizumab alone, demonstrated by calculation of Ktrans (volume transfer coefficient), which represents vascular perfusion (Ktrans increase of ≈ 18%).5 Hoyt et al7 showed that contrast-enhanced US had the capability to show trends in data between antiangiogenic therapy and control groups in a murine model within 3 days, but they were not shown to be significant by day 6. Streeter et al28 showed analysis of tumor angiogenesis with 3-dimensional contrast-enhanced US molecular imaging targeting αvβ3-integrin, suggesting that volumetric imaging can reduce errors associated with 2-dimensional single-plane imaging. Other not able contrast-enhanced US research that has surfaced includes using volumetric contrast enhanced US molecular imaging to determine differences in whole tumor perfusion after bevacizumab treatment.6 These promising results with volumetric contrast-enhanced US showed that tumor perfusion decreased in response to therapy, which also correlated to decreases in the tumor size when compared to controls. Although the early response to the drug was not shown in this volumetric contrast-enhanced US study, this technique shows advancements in the field of contrast-enhanced US and gives promise to future studies of combining targeted molecular US imaging and volumetric scanning.

Evaluating the early tumor response to treatment gives information about the progressive nature of the disease, which is essential in determining the patient’s prognosis. Angiogenesis is essential for tumor growth and metastasis; therefore, antiangiogenic therapy has become a popular targeted therapy used solo or in combination with chemotherapy to reduce tumor perfusion and impede growth. It has been shown that not all tumors respond to antiangiogenic therapy; therefore, it is necessary to make an early determination of the treatment response.29–33 Early detection of the response will be cost-effective as well as beneficial in finding the most efficient antitumor drug for each patient.

As mentioned, molecular US imaging uses microbubbles targeted to overexpressed proteins to characterize physiologic and molecular events, clarifying why it has become increasingly popular in assessing antiangiogenic therapy in cancer.34–36 Standardizing techniques to measure initial and longitudinal responses to treatment is a necessary step in advancing cancer therapy.35 Targeted contrast-enhanced high-frequency US has been shown to facilitate in vivo molecular imaging of VEGFR2 expression in the tumor vascular endothelium to compare metastatic and nonmetastatic breast cancer.37 Subharmonic US imaging had also shown potential in quantifying and assessing changes in tumor vasculature over 2 weeks of antiangiogenic therapy.38 Clinical trials using dynamic contrast-enhanced Doppler US to assess antiangiogenic therapy in renal cancer have shown significant differences in contrast uptake in tumors that have a positive response to therapy over 6 weeks, yet Doppler US is known to be a poor measure when compared to microvessel density.39,40 There have been clinical trials using dynamic contrast-enhanced US as a prognostic tool for cancer, showing correlations between dynamic contrast-enhanced US and the response to sunitinib after 15 days of therapy.41 Lassau et al41 showed promising results using dynamic contrast-enhanced US to study the effects of anti-tumor drugs in clinical trials. Sensitivity and reliability are essential in monitoring the angiogenic response to therapy; therefore, using multitargeted contrast-enhanced US could enhance capabilities and advance procedures that are currently being used to assess the early tumor response to treatment. However, targeted contrast agents can accomplish site-directed imaging or therapy by a variety of active and passive mechanisms.

Single- and dual-targeted molecular US imaging strategies from Willmann et al23,42 showed positive enhancement of tumor vasculature compared to traditional contrast-enhanced US. Following this method, a triple-targeted microbubble was developed by Warram et al,13 which showed the synergistic effects of targeting 3 different molecular agents simultaneously. This approach has been proven to enhance visualization of tumor angiogenesis for cancer staging and prognosis, which allows increased detailed information about tumor angiogenesis. Using a multitargeted microbubble, we are able to see substantial differences in tumor vasculature after dosing with an antiangiogenic drug. This molecular imaging approach was also supported by histologic evidence of substantial differences in microvessel density from antiangiogenic therapy on day 3. This imaging approach gives information regarding the tumor response to therapy before changes in the tumor size can be detected (current standard of care). This process allows an early assessment that could be added to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, which state that the current standard for measuring the response to therapeutics in cancer is by tumor measurements.43 Successful evaluation of the early tumor response to therapy could increase the efficiency of anticancer treatment, thereby improving patient prognoses and results.

In conclusion, molecular US imaging of multiple tumor-specific protein markers shows potential to evaluate the early tumor response to antiangiogenic therapy. Multitargeted microbubbles allow a noninvasive approach to determine the early tumor response to antiangiogenic therapy through molecular US imaging.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant UL1RR025777, National Cancer Institute grant CA13148-38, the University of Alabama at Birmingham Comprehensive Cancer Center, and National Institutes of Health grant T32EB004312 from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering.

Abbreviations

- US

ultrasound

- VEGFR2

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2011. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1182–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis. Adv Cancer Res. 1974;19:331–358. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Institute. Fact Sheet: Targeted Cancer Therapies. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim H, Folks KD, Guo L, et al. DCE-MRI detects early vascular response in breast tumor xenografts following anti-DR5 therapy. Mol Imaging Biol. 2011;13:94–103. doi: 10.1007/s11307-010-0320-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoyt K, Sorace A, Saini R. Quantitative mapping of tumor vascularity using volumetric contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Invest Radiol. 2012;47:167–174. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e318234e6bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoyt K, Warram JM, Umphrey H, et al. Determination of breast cancer response to bevacizumab therapy using contrast-enhanced ultrasound and artificial neural networks. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:577–585. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.4.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Jong N, Frinking PJ, Bouakaz A, et al. Optical imaging of contrast agent microbubbles in an ultrasound field with a 100-MHz camera. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2000;26:487–492. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(99)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calliada F, Campani R, Bottinelli O, Bozzini A, Sommaruga MG. Ultrasound contrast agents: basic principles. Eur J Radiol. 1998;27(suppl 2):S157–S160. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(98)00057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cosgrove D. Echo enhancers and ultrasound imaging. Eur J Radiol. 1997;26:64–76. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(96)01150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cosgrove D, Lassau N. Assessment of tumour angiogenesis using contrast- enhanced ultrasound [in French] J Radiol. 2009;90:156–164. doi: 10.1016/s0221-0363(09)70094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sorace AG, Warram JM, Umphrey H, Hoyt K. Microbubble-mediated ultrasonic techniques for improved chemotherapeutic delivery in cancer. J Drug Target. 2012;20:43–54. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2011.622397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warram JM, Sorace AG, Saini R, Umphrey HR, Zinn KR, Hoyt K. A triple-targeted ultrasound contrast agent provides improved localization to tumor vasculature. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30:921–931. doi: 10.7863/jum.2011.30.7.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deshpande N, Ren Y, Foygel K, Rosenberg J, Willmann JK. Tumor angiogenic marker expression levels during tumor growth: longitudinal assessment with molecularly targeted microbubbles and US imaging. Radiology. 2011;258:804–811. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10101079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenbrey JR, Forsberg F. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound for molecular imaging of angiogenesis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37(suppl 1):S138–S146. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1449-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willmann JK, Cheng Z, Davis C, et al. Targeted microbubbles for imaging tumor angiogenesis: assessment of whole-body biodistribution with dynamic micro-PET in mice. Radiology. 2008;249:212–219. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2491072050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saini R, Warram JM, Sorace AG, Umphrey H, Zinn KR, Hoyt K. Model system using controlled receptor expression for evaluating targeted ultrasound contrast agents. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2011;37:1306–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou JH, Zheng W, Cao LH, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonic parametric perfusion imaging in the evaluation of antiangiogenic tumor treatment. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:1360–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou JH, Cao LH, Liu JB, et al. Quantitative assessment of tumor blood flow in mice after treatment with different doses of anantiangiogenic agent with contrast-enhanced destruction-replenishment US. Radiology. 2011;259:406–413. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10101339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forsberg F, Ro RJ, Liu JB, Lipcan KJ, Potoczek M, Nazarian LN. Monitoring angiogenesis in human melanoma xenograft model using contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging. Ultrason Imaging. 2008;30:237–246. doi: 10.1177/016173460803000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindner JR, Song J, Christiansen J, Klibanov AL, Xu F, Ley K. Ultrasound assessment of inflammation and renal tissue injury with microbubbles targeted to P-selectin. Circulation. 2001;104:2107–2112. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindner JR. Molecular imaging with contrast ultrasound and targeted microbubbles. J Nucl Cardiol. 2004;11:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willmann JK, Lutz AM, Paulmurugan R, et al. Dual-targeted contrast agent for US assessment of tumor angiogenesis in vivo. Radiology. 2008;248:936–944. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2483072231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klibanov AL, Rychak JJ, Yang WC, et al. Targeted ultrasound contrast agent for molecular imaging of inflammation in high-shear flow. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2006;1:259–266. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shih T, Lindley C. Bevacizumab: an angiogenesis inhibitor for the treatment of solid malignancies. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1779–1802. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain RK. Tumor angiogenesis and accessibility: role of vascular endothelial growth factor. Semin Oncol. 2002;29(suppl 16):3–9. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Novotny W. Bevacizumab (Avastin), a humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody for cancer therapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Streeter JE, Gessner RC, Tsuruta J, Feingold S, Dayton PA. Assessment of molecular imaging of angiogenesis with three-dimensional ultrasonography. Mol Imaging. 2011;10:460–468. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rugo HS. Bevacizumab in the treatment of breast cancer: rationale and current data. Oncologist. 2004;9(suppl 1):43–49. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-suppl_1-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen HX. Expanding the clinical development of bevacizumab. Oncologist. 2004;9(suppl 1):27–35. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-suppl_1-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM. Arandomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:427–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robert NJ, Diéras V, Glaspy J, et al. RIBBON-1: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for first-line treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative, locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1252–1260. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666–2676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller JC, Pien HH, Sahani D, Sorensen AG, Thrall JH. Imaging angiogenesis: applications and potential for drug development. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:172–187. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atri M. New technologies and directed agents for applications of cancer imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3299–3308. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lamuraglia M, Bridal SL, Santin M, et al. Clinical relevance of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in monitoring anti-angiogenic therapy of cancer: current status and perspectives. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;73:202–212. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyshchik A, Fleischer AC, Huamani J, Hallahan DE, Brissova M, Gore JC. Molecular imaging of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 expression using targeted contrast-enhanced high-frequency ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1575–1586. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.11.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pollard RE, Broumas AR, Wisner ER, Vekich SV, Ferrara KW. Quantitative contrast enhanced ultrasound and CT assessment of tumor response to antiangiogenic therapy in rats. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007;33:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rehman S, Jayson GC. Molecular imaging of antiangiogenic agents. Oncologist. 2005;10:92–103. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-2-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lamuraglia M, Escudier B, Chami L, et al. To predict progression-freesurvival and overall survival in metastatic renal cancer treated with sorafenib: pilot study using dynamic contrast-enhanced Doppler ultrasound. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:2472–2479. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lassau N, Koscielny S, Albiges L, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib: early evaluation of treatment response using dynamic contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1216–1225. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Willmann JK, Paulmurugan R, Chen K, et al. US imaging of tumor angiogenesis with microbubbles targeted to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor type 2 in mice. Radiology. 2008;246:508–518. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462070536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]