Abstract

Objective To validate the use of the Wells clinical decision rule combined with a point of care D-dimer test to safely exclude pulmonary embolism in primary care.

Design Prospective cohort study.

Setting Primary care across three different regions of the Netherlands (Amsterdam, Maastricht, and Utrecht).

Participants 598 adults with suspected pulmonary embolism in primary care.

Interventions Doctors scored patients according to the seven variables of the Wells rule and carried out a qualitative point of care D-dimer test. All patients were referred to secondary care and diagnosed according to local protocols. Pulmonary embolism was confirmed or refuted on the basis of a composite reference standard, including spiral computed tomography and three months’ follow-up.

Main outcome measures Diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity and specificity), proportion of patients at low risk (efficiency), number of missed patients with pulmonary embolism in low risk category (false negative rate), and the presence of symptomatic venous thromboembolism, based on the composite reference standard, including events during the follow-up period of three months.

Results Pulmonary embolism was present in 73 patients (prevalence 12.2%). On the basis of a threshold Wells score of ≤4 and a negative qualitative D-dimer test result, 272 of 598 patients were classified as low risk (efficiency 45.5%). Four cases of pulmonary embolism were observed in these 272 patients (false negative rate 1.5%, 95% confidence interval 0.4% to 3.7%). The sensitivity and specificity of this combined diagnostic approach was 94.5% (86.6% to 98.5%) and 51.0% (46.7% to 55.4%), respectively.

Conclusion A Wells score of ≤4 combined with a negative qualitative D-dimer test result can safely and efficiently exclude pulmonary embolism in primary care.

Introduction

For many doctors, patients with unexplained shortness of breath or pleuritic chest pain pose a diagnostic dilemma. In particular doctors in primary care, who in many countries are the first to be consulted when patients have these symptoms, have to differentiate between common self limiting diseases, such as myalgia or respiratory tract infections, and the rarer life threatening diseases such as pulmonary embolism. As the symptoms of pulmonary embolism may be relatively mild, it can be easily missed,1 2 and because pulmonary embolism has a high mortality doctors do not always get another chance if it is misdiagnosed.3 As a result, most doctors in primary care have a low threshold for referring patients with suspected pulmonary embolism and only 10-15% of referred patients are actually diagnosed as having the condition.4

To stratify patients with suspected pulmonary embolism between a high probability (need for referral) of having the condition compared with a low probability, clinical decision rules (combining the different characteristics of patients and the disease into a score) have been developed. The clinical decision rule developed by Wells and colleagues is the most widely known, validated, and implemented tool for the detection of pulmonary embolism in secondary care. The Wells clinical decision rule combines seven items into a score ranging from 0 to 12.5. Based on many studies in secondary care, a threshold of <2 or ≤4 was introduced into the rule.5 Below these levels patients are classified, respectively, as being at very low risk or low risk of having pulmonary embolism. A large diagnostic management study in secondary care concluded that a negative laboratory based quantitative D-dimer (degradation product of fibrin) test result in patients with a Wells score of ≤4 safely excluded pulmonary embolism without the need for additional investigations by imaging.6

Such a diagnostic strategy seems ideal in primary care to facilitate decisions on referral to secondary care, in particular since easy to use point of care D-dimer tests providing results within minutes are available for use at the doctor’s practice or in the patient’s home.7 Before such a diagnostic strategy can be implemented, however, it needs to be validated in the proper setting of primary care.8 9 Owing to differences in the spectrum of disease, symptoms, and doctors’ experience, encouraging results from referral centres may not be readily applicable in primary care.10 11

We carried out a formal external validation of the Wells pulmonary embolism rule combined with a point of care qualitative D-Dimer test to evaluate the safety and efficiency of using this clinical decision rule in primary care.

Methods

The Amsterdam Maastricht Utrecht Study on thrombo-Embolism (AMUSE-2) was a prospective cohort study in primary care, evaluating a diagnostic strategy consisting of the Wells pulmonary embolism rule (table 1) and a point of care D-dimer test (Clearview Simplify; Inverness Medical, Bedford, UK). More than 300 primary care doctors across three different regions of the Netherlands (Amsterdam, Maastricht, and Utrecht) included patients during and outside of practice hours. One researcher (GJG, PE, or WL) contacted all primary care doctors willing to cooperate with the study and explained the logistics of the study and the use of study forms and provided written instruction on how to use the D-dimer test. The study took place between 1 July 2007 and 31 December 2010.

Table 1.

Items of Wells pulmonary embolism rule

| Variables | Points |

|---|---|

| Clinical signs and symptoms of deep vein thrombosis (minimum of leg swelling and pain with palpation of deep veins) | 3.0 |

| Pulmonary embolism more likely than alternative diagnosis | 3.0 |

| Heart rate >100 beats/min | 1.5 |

| Immobilisation (>3 days) or surgery in previous four weeks | 1.5 |

| Previous pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis | 1.5 |

| Haemoptysis | 1.0 |

| Malignancy (receiving treatment, treated in past six months, or palliative) | 1.0 |

Patients eligible for inclusion were consecutive adults (≥18 years) with suspected pulmonary embolism, based on the presence of at least one of the following symptoms: unexplained (sudden) dyspnoea, deterioration of existing dyspnoea, pain on inspiration, or unexplained cough. We excluded patients if they received anticoagulant treatment (vitamin K antagonists or heparin) at presentation, they were pregnant, follow-up was not possible, or they were unwilling or unable to provide written informed consent.

Diagnostic strategy under study

After written informed consent had been obtained, the doctors documented information on the patient’s history and physical examination and applied the Wells pulmonary embolism rule using a standard form. A qualitative D-dimer test was subsequently carried out using 35 μL of capillary or venous blood mixed with two drops of test reagent in a disposable device.7 A pink-purple coloured line indicates a positive test result (D-dimer level >80 ng/mL). The test strip can be read at 10 minutes.

Regardless of the results of the Wells rule and D-dimer test, we asked the doctors to refer all patients to secondary care for reference testing. In addition, to avoid interference with our aim to externally validate the Wells rule combined with D-dimer testing, we explicitly provided no guidance on how to use the score (which score thresholds) to guide subsequent management.8 9 Hence, doctors in secondary care were asked to carry out the diagnostic procedures at their own discretion based on local hospital guidelines, and independent of the results from primary care.

Reference standard

In secondary care, the diagnostic strategy was based on current guidelines and routine care protocols. In the Netherlands, this is mostly a combination of estimated probability and quantitative laboratory based D-dimer testing, followed by computed tomography if indicated. In line with most diagnostic studies in this area5 6 12 13 we used a composite reference standard of spiral computed tomography, ventilation-perfusion scanning, pulmonary angiography, leg ultrasonography, and clinical probability assessment as done in secondary care (with or without D-dimer testing).

We retrieved medical information about the investigations done to establish or refute a diagnosis of pulmonary embolism, including hospital discharge letters. In addition, we followed up all patients for three months. During the follow-up period we asked the primary care doctors to document the occurrence of any potential (recurrent) venous thromboembolic events, and bleeding complications associated with anticoagulant therapy if given. Finally, an independent adjudication committee evaluated all patients with a diagnosis of pulmonary embolism despite a low Wells score and negative D-dimer test result (see supplementary file for a full description of the reference standard strategy).

The primary outcomes of this study were diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity and specificity), proportion of patients at low risk (efficiency), number of missed patients with pulmonary embolism in low risk category (false negative rate), and the presence of symptomatic venous thromboembolism, based on our composite reference standard, including events during the follow-up period of three months.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were done using the SPSS software package PASW version 17. We quantified the safety and efficiency of ruling out pulmonary embolism on the basis of a low risk score using our diagnostic strategy. Patients considered at low risk were initially defined by a Wells score of ≤4 and a negative D-dimer test result. We defined the failure rate as the proportion of patients with a missed symptomatic and proved venous thromboembolism event during three months’ follow-up in those patients who were initially classified by the strategy to be at low risk, including a 95% confidence interval (using Fischer’s exact test).

In contrast with therapeutic or intervention studies, formal sample size calculations based on power assumptions for diagnostic (or prognostic) modeling cohort studies do not exist and are seldom considered. However, for single dichotomous tests, such calculations can be done for the expected positive or negative predictive values or their complements (false positive or false negative proportion, respectively).14 To obtain some insight a priori of what number of patients and thus doctors needed to be included, we considered the original continuous Wells rule plus D-dimer test result as one overall single test and dichotomised the result. We focused on the exclusion of pulmonary embolism with a minimum of missed of cases (false negative proportion or failure rate). Based on various previous studies in secondary care (notably the Christopher study6), we assumed that the point estimate of this failure rate would be around 0.5%. We subsequently used this estimate to calculate the number of patients for our study,14 where we selected a stringent upper limit of the confidence interval of this estimate at 2.0%, even though previous studies had higher upper limits (4%).5 15 Accordingly, expecting a failure rate for detecting pulmonary embolism of 0.5% and being able to exclude (maximally) 2.0% of patients with pulmonary embolism, and using a type I error of 0.05 (one sided, since any value below 0.5% is desired) and type II error of 0.2, we needed to include about 335 patients with a low risk of pulmonary embolism.

Next we calculated the efficiency of the Wells rule in excluding pulmonary embolism. We defined efficiency as the proportion of patients at low risk for pulmonary embolism among all study patients. Subsequently, we similarly estimated the failure rate and efficiency using a Wells threshold score of <2 in combination with a negative D-dimer test result—that is, patients at very low risk.

In addition to the failure rate and efficiency, we calculated the conventional diagnostic accuracy measures (sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values) for the different thresholds on the Wells rule, in combination with D-dimer testing.

Missing values for the Wells rule items or D-dimer test results were observed in 24 patients (4.0% for missing values on any of the Wells rule items or D-dimer test; range 0.5% for heart rate >100 beats/min to 2.7% for results of the D-dimer test). To minimise the effect of the bias associated with selectively ignoring these 24 patients, we imputed these missing values using multiple imputation techniques. Such techniques are based on the correlation between each variable with missing values and all other variables as estimated from the complete set of participants, using available observed data.16 17

Results

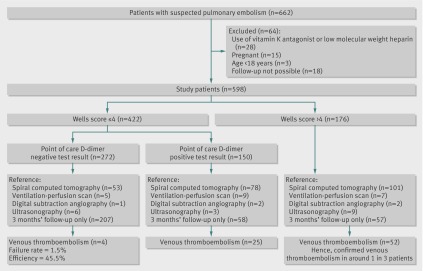

Data were prospectively collected on 662 patients suspected of having pulmonary embolism by their doctor (figure). One or more of the predefined exclusion criteria were met by 64 patients: 28 used vitamin K antagonists or low molecular weight heparin at the time of inclusion, 15 were pregnant, three were younger than 18, and 18 could not be followed-up for logistical reasons. The study population therefore consisted of 598 patients, with a mean age of 48 years, and 71.0% (n=425) of whom were women.

Flow of participants through study

Pulmonary embolism was diagnosed in 68 patients directly after referral. In an additional five patients pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis was diagnosed during three months of follow-up (one case of deep vein thrombosis and four of pulmonary embolism, no fatal events). Hence a total of 73 patients (12.2%) had a diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Table 2 details the characteristics of the patients.

Table 2.

Characteristics of all participants (n=598). Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years): | |

| Mean (SD) | 48 (16) |

| Range | 18-91 |

| Women | 425 (71.0) |

| Diagnosis of venous thromboembolism* | 73 (12.2) |

| Unexplained sudden onset dyspnoea | 329 (55.0) |

| Pain on inspiration | 465 (77.8) |

| Unexplained cough | 188 (31.4) |

| Signs and symptoms suggestive of deep vein thrombosis | 57 (9.5) |

| Pulmonary embolism most likely diagnosis | 333 (55.7) |

| Heart rate >100 beats/min | 111 (18.6) |

| Immobilisation or surgery | 94 (15.7) |

| Previous deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism | 84 (14.0) |

| Haemoptysis | 21 (3.5) |

| Active (undergoing treatment ≤6 months) malignancy | 26 (4.3) |

| Wells rule: | |

| Score ≥2 | 361 (60.4) |

| Score >4 | 176 (29.4) |

| Positive point of care D-dimer test result | 220 (36.8) |

*Composite reference standard, including three months of follow-up.

Results of the Wells pulmonary embolism rule

Overall, 422 patients had a Wells score of ≤4 and 237 had a score of <2. In these patients, venous thromboembolism events were observed in 21 (5.0%, 95% confidence interval 3.1% to 7.5%) and 7 (3.0%, 1.2% to 6.0%) patients, respectively. In patients with a Wells score of >4, 52 (29.5%, 22.9% to 36.9%) venous thromboembolism events occurred (figure).

Combining the Wells rule with point of care D-dimer testing

Results for the point of care D-dimer test were not interpretable in 39 patients (6.5% of all patients). According to the study protocol, these tests were evaluated as positive test results in all analyses.

If a threshold Wells score of ≤4 was combined with a negative D-dimer test result, then 4/272 patients in this low risk category would be diagnosed as having pulmonary embolism: failure rate 1.5% (95% confidence interval 0.4% to 3.7%; table 3). The efficiency of this strategy was 45.5% (272/598). The sensitivity and specificity of a score of ≤4 combined with a negative D-dimer test result were 94.5% (86.6% to 98.5%) and 51.0% (46.7% to 55.4%), respectively. In 168 patients with a Wells score of <2, the D-dimer test result was also negative. In these patients at very low risk, two cases of pulmonary embolism were observed, yielding a failure rate of 1.2% (0.1% to 4.2%) and an efficiency of 28.1% (168/598). The sensitivity and specificity of this strategy were 97.3% (90.5% to 99.7%) and 31.6% (27.7% to 35.8%), respectively (table 3).

Table 3.

Diagnostic variables of Wells rule, combined with a qualitative point of care negative D-dimer test result in primary care. Values are percentages (95% confidence intervals)

| Diagnostic variables | Negative D-dimer test result | |

|---|---|---|

| Wells score ≤4 | Wells score <2 | |

| Efficiency* | 45.5 (41.4 to 49.6) | 28.1 (24.5 to 31.9) |

| Failure rate† | 1.5 (0.4 to 3.7) | 1.2 (0.1 to 4.2) |

| Sensitivity | 94.5 (86.6 to 98.5) | 97.3 (90.5 to 99.7) |

| Specificity | 51.0 (46.7 to 55.4) | 31.6 (27.7 to 35.8) |

| Positive predictive value | 21.2 (16.9 to 26.0) | 19.8 (15.8 to 24.3) |

| Negative predictive value | 98.5 (96.3 to 99.6) | 98.8 (95.8 to 99.9) |

*Proportion of all patients in whom pulmonary embolism was excluded based on Wells score below various cut-off values and a negative D-dimer test result.

†Proportion of patients in whom pulmonary embolism was excluded based on Wells score below various cut-off values and a negative D-dimer test result, with symptoms and proved venous thromboembolism during three months’ follow-up.

Low risk patients with pulmonary embolism

Four patients classified at low risk (Wells score ≤4 and negative D-dimer test result) were diagnosed as having pulmonary embolism. Table 4 describes these cases in more detail. They were judged by an independent adjudication committee at the end of the study. The committee concluded that a diagnosis of pulmonary embolism was questionable in one patient (80 year old woman in table 4) based on an inadequate amount of contrast in the re-evaluated spiral computed tomograms. Reanalysing the results with this patient defined as not having pulmonary embolism produced a lower failure rate: 1.1% (0.2% to 3.2%) for a Wells score of ≤4 and 0.6% (0.0% to 3.3%) for a Wells score of <2.

Table 4.

Detailed description of four patients classified as low risk (Wells score ≤4 and negative point of care D-dimer test) but diagnosed as having pulmonary embolism by spiral computed tomography directly after referral

| Patient No | Description | D-dimer test result |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 75 year old man, with acute onset of pain on inspiration, no shortness of breath. Wells score 1.5* (previous venous thromboembolism) | Negative |

| 2 | 25 year old woman with acute onset of pain on inspiration and shortness of breath. Patient used oral contraceptives. Wells score 0* | Negative |

| 3 | 80 year old woman with subacute progressive shortness of breath after a flight. Wells score 3* (previous venous thromboembolism and immobilisation) | Negative |

| 4 | 30 year old woman with acute onset of pain on inspiration but no shortness of breath. Patient used oral contraceptives. Wells score 3* (pulmonary embolism most likely diagnosis) | Negative |

*As scored by primary care doctor.

†Not interpretable; to simplify results were analysed as a positive test result.

Discussion

Almost half (45.5%) of 598 patients with suspected pulmonary embolism in primary care were classified at low risk of the condition on the basis of a score of ≤4 on the Wells pulmonary embolism rule combined with a negative point of care D-dimer test result. Pulmonary embolism was observed in 1.5% of these patients. In addition, lowering the score threshold to <2 combined with the D-dimer test result yielded a lower failure rate (1.2%) but at the cost of lower efficiency (28.1%). These results are in accordance with studies done in secondary care, as documented in a recent meta-analysis on the performance of several clinical decision rules, including the Wells rule combined with both a qualitative and a quantitative D-dimer test.18

Strengths and limitations of the study

This is the first study to validate the Wells rule in a primary care setting, in a large population of almost 600 patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. This study does, however, have several strengths and limitations. Firstly, the reference standard of pulmonary embolism consisted of various combinations of laboratory and imaging procedures, including follow-up for three months, to diagnose or refute a case of pulmonary embolism, which is differential verification bias. Although we asked the primary care doctors to refer all patients regardless of their Wells score and D-dimer test result, the doctors in secondary care were not explicitly blinded to these results. Consequently, differential verification depended (at least partly) on our index test under study: patients with a low Wells score and negative D-dimer test result more often did not undergo imaging tests for pulmonary embolism compared with patients with a high Wells score. Although such a combined reference approach is common in diagnostic studies of pulmonary embolism, differential verification could lead to an over optimistic estimate of the failure rate.19 For example, in patients with a low Wells score and a negative D-dimer test result, subsegmental pulmonary embolism could be missed if these patients only received follow-up as a reference. However, missing such subsegmental pulmonary embolism is less relevant from a clinical perspective.20 Moreover, our study followed common clinical practice from both academic and non-academic hospitals in many parts of the world. In other words, differential verification of the diagnosis in patients suspected of pulmonary embolism is common in daily clinical practice in many parts of the world, thereby increasing the generalisability of our results.

Secondly, in 57 patients no initial imaging to diagnose or refute acute pulmonary embolism was done in secondary care, despite a high Wells score and the recommendation of imaging by both national and international guidelines. Rather, these patients were followed-up in primary care (see the supplementary file for a summary of the final diagnoses in these patients). During follow-up venous thromboembolism was diagnosed in two of these patients: both with confirmed deep vein thrombosis shortly after referral (Wells score of 6.0 in primary care for both patients). Although we do not know the results of all the Wells score and D-dimer testing in secondary care, a reason for not subjecting the referred high risk patients to imaging could be a discrepancy in the clinical probability assessment between the primary care doctor and the hospital. For instance, this discrepancy may be explained by differences in scoring the subjective item of the Wells rule that states “pulmonary embolism more likely than an alternative diagnosis” and differences in the result of the qualitative point of care D-dimer test used in our study and the quantitative D-dimer tests used in secondary care.

Thirdly, an independent adjudication committee re-evaluated all four patients with pulmonary embolism who were missed because they had a low Wells score (≤4 or <2) combined with a negative D-dimer test result. The committee concluded that in one case a diagnosis of pulmonary embolism was questionable. Reanalysing this patient as not having pulmonary embolism resulted in a, albeit small, decrease of the failure rates for pulmonary embolism. As in reality this patient was treated with anticoagulants based on the presumed diagnosis of pulmonary embolism, for the main analyses we analysed this patient as having pulmonary embolism, yielding the failure rates as presented in the figure and table 3. However, it is possible that our results are more optimistic than the presented failure rates.

Fourthly, D-dimer test results were not interpretable in 39 patients (6.5% of all study patients). This indicates that, although D-dimer testing can be easily carried out in a primary care setting, interpretation of a result using this qualitative assay can sometimes be difficult. In a meta-analysis on point of care D-dimer testing, difficulty in reading the test results using an older qualitative point of care D-dimer test (SimpliRED D-dimer assay; BBInternational, Cardiff, UK) resulted in much heterogeneity in the pooled analysis for this assay.7 As a consequence, most experts agree that this older D-dimer assay should no longer be recommended for use in daily clinical practice. Theoretically, the same problem could arise in the future for the qualitative Clearview Simplify D-dimer test (Inverness Medical, Bedford, UK) as more studies for this assay become available. However, most of the D-dimer test results in the present study were easily interpretable. In addition (as in all our analyses) we believe a solution would be to classify non-interpretable results as positive. This effectively prevents a diagnosis of pulmonary embolism from being missed and is only required in a small number of tested patients.

Finally, at the end of our recruitment phase we experienced a gradual decline in inclusion rates. We were able to include 272 low risk patients, 81% of our predefined sample size. The number of patients with pulmonary embolism was higher than expected and thus the confidence limits were wider as well. Accordingly, although the point estimate of our failure rate (1.5%) was lower than 2%, the confidence interval did cross the predefined 2% limit. However, no formal methods for power calculations of model validation studies exist and, moreover, there is much discussion among clinicians on what proportion is still acceptable as the upper limit. Many studies have considered an upper limit of 4% as acceptable,5 15 but we were conservative in our a priori sample size by setting it at 2%. This decision was based on the aim of the original derivation study of the Wells rule, which was to determine a score that is able to designate pulmonary embolism as unlikely such that a negative D-dimer test result in these patients would result in a rate (that is, point estimate) of pulmonary embolism close to 2.0%.5 In this original derivation study the failure rate for pulmonary embolism was 2.2% with a 95% confidence interval of 1.0% to 4.0%. In addition, in the Prospective Investigation of Pulmonary Embolism Diagnosis (PIOPED) II study on the diagnostic accuracy of spiral computed tomography in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism, the failure rate was 1.7% with a 95% confidence interval of 0.7% to 3.9%.15 Our results are in line with these previous studies. Increasing the number of included patients potentially would not change our point estimate for the failure rate but only narrow the confidence interval. We believe that the inclusion of more patients would not lead to different inferences about the benefits of the Wells rule in primary care.

Clinical implications

Pulmonary embolism is a potentially life threatening disease that may be difficult to diagnose as signs and symptoms can be relatively mild. In our previous study on using a clinical decision rule and D-dimer testing to exclude deep vein thrombosis,21 many participating doctors asked whether a similar approach would be possible for suspected pulmonary embolism. The present validation study shows that such an approach would be feasible in primary care: a Wells score of ≤4 combined with a negative point of care D-dimer test result ruled out pulmonary embolism in 4-5 of 10 patients, with a failure rate of less than 2%, which is considered safe by most published consensus statements.5 15 Such a rule-out strategy makes it possible for primary care doctors to safely exclude pulmonary embolism in a large proportion of patients suspected of having the condition, thereby reducing the costs and burden to the patient (for example, reducing the risk of contrast nephropathy associated with spiral computed tomography) associated with an unnecessary referral to secondary care.

Conclusion

Pulmonary embolism can be safely excluded on the basis of a Wells score of ≤4 combined with a negative qualitative point of care D-dimer test result. Using a threshold of <2 is even safer. Future studies, where patient management is guided by the Wells rule and point of care D-dimer test results, are indicated to evaluate the feasibility of such an approach in reducing the costs and burden to the patient.

What is already known on this topic

A low score on the Wells pulmonary embolism rule combined with D-dimer testing safely excludes pulmonary embolism in about one third of patients in secondary care

Validation studies on using the Wells rule combined with D-dimer testing in primary care are lacking

What this study adds

A low Wells score (≤4) and a negative point of care D-dimer test result excludes pulmonary embolism in about four of 10 patients

Only four patients (1.5% of all low risk patients) were missed by this combined approach

We thank LFM Beenen, radiologist at the Department of Radiology of the Academic Medical Center Amsterdam, for re-evaluating all spiral computed tomography scans as part of the adjudication process.

Contributors: HRB, HCPMvW, RO, KGMM, AW, HEJHS, HtC, and MHP had the original idea for the study and were involved in writing the original study protocol. GJG, PMGE, and WAML were involved in data collection and carried out the statistical analyses. GJG, PMGE, and WAML drafted the first version of the manuscript, which was subsequently revised by the other authors. GJG, PMGE, and WAML contributed equally to the study, had full access to all of the data in the study, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: The Netherlands Heart Foundation funded the study (NHS-2006B237). GlaxoSmithKline and Inverness Medical co-funded the study with unrestricted research grants. All funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, analyses or reporting of the study or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Data sharing: Additional data are available on request from the corresponding author at g.j.geersing@umcutrecht.nl..

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e6564

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Description of reference standard

Final diagnoses in 57 patients who, despite a high Wells score, did not undergo initial imaging

References

- 1.Meyer G, Roy PM, Gilberg S, Perrier A. Pulmonary embolism. BMJ 2010;340:c1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiff GD, Hasan O, Kim S, Abrams R, Cosby K, Lambert BL, et al. Diagnostic error in medicine: analysis of 583 physician-reported errors. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1881-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chunilal SD, Eikelboom JW, Attia J, Miniati M, Panju AA, Simel DL, et al. Does this patient have pulmonary embolism? JAMA 2003;290:2849-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Gal G, Bounameaux H. Diagnosing pulmonary embolism: running after the decreasing prevalence of cases among suspected patients. J Thromb Haemost 2004;2:1244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, Ginsberg JS, Kearon C, Gent M, et al. Derivation of a simple clinical model to categorize patients probability of pulmonary embolism: increasing the models utility with the SimpliRED D-dimer. Thromb Haemost 2000;83:416-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Belle A, Buller HR, Huisman MV, Huisman PM, Kaasjager K, Kamphuisen PW, et al. Effectiveness of managing suspected pulmonary embolism using an algorithm combining clinical probability, D-dimer testing, and computed tomography. JAMA 2006;295:172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geersing GJ, Janssen KJ, Oudega R, Bax L, Hoes AW, Reitsma JB, et al. Excluding venous thromboembolism using point of care D-dimer tests in outpatients: a diagnostic meta-analysis. BMJ 2009;339:b2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altman DG, Vergouwe Y, Royston P, Moons KG. Prognosis and prognostic research: validating a prognostic model. BMJ 2009;338:b605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reilly BM, Evans AT. Translating clinical research into clinical practice: impact of using prediction rules to make decisions. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knottnerus JA. Between iatrotropic stimulus and interiatric referral: the domain of primary care research. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:1201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oudega R, Hoes AW, Moons KG. The Wells rule does not adequately rule out deep venous thrombosis in primary care patients. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kline JA, Courtney DM, Kabrhel C, Moore CL, Smithline HA, Plewa MC, et al. Prospective multicenter evaluation of the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria. J Thromb Haemost 2008;6:772-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klok FA, Kruisman E, Spaan J, Nijkeuter M, Righini M, Aujesky D, et al. Comparison of the revised Geneva score with the Wells rule for assessing clinical probability of pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost 2008;6:40-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simel DL, Samsa GP, Matchar DB. Likelihood ratios with confidence: sample size estimation for diagnostic test studies. J Clin Epidemiol 1991;44:763-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perrier A, Roy PM, Sanchez O, Le GG, Meyer G, Gourdier AL, et al. Multidetector-row computed tomography in suspected pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1760-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janssen KJ, Vergouwe Y, Donders AR, Harrell FE Jr, Chen Q, Grobbee DE, et al. Dealing with missing predictor values when applying clinical prediction models. Clin Chem 2009;55:994-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple imputation in health-care databases: an overview and some applications. Stat Med 1991;10:585-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucassen W, Geersing GJ, Erkens PM, Reitsma JB, Moons KG, Buller H, et al. Clinical decision rules for excluding pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:448-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Glas AS, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. Sources of variation and bias in studies of diagnostic accuracy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:189-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrier M, Righini M, Wells PS, Perrier A, Anderson DR, Rodger MA, et al. Subsegmental pulmonary embolism diagnosed by computed tomography: incidence and clinical implications. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the management outcome studies. J Thromb Haemost 2010;8:1716-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buller HR, Ten Cate-Hoek AJ, Hoes AW, Joore MA, Moons KG, Oudega R, et al. Safely ruling out deep venous thrombosis in primary care. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:229-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of reference standard

Final diagnoses in 57 patients who, despite a high Wells score, did not undergo initial imaging