Abstract

Non-gay identified (NGI) Black men who have sex with both men and women (MSMW) and use substances are at risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV to their partners. Homophobic community norms can discourage such men from disclosing their risk behaviour to female partners and others, including service providers. It is important to understand the dynamics of risk in this vulnerable population, but research is challenged by the men’s need for secrecy. In this paper we report on successful efforts to recruit 33 non-disclosing, NGI Black MSMW for in-depth interviews concerning substance use, HIV risk and attitudes toward disclosing their risk behaviour. We employed targeted and referral sampling, with initial contacts and/or key informants drawn from several types of settings in New York City including known gay venues, community organisations, neighbourhood networks and the Internet. Key informant gatekeepers and the ability to establish rapport proved central to success. Perceived stigma is a source of social isolation, but men are willing to discuss their risk behaviour when they trust interviewers to protect their privacy and engage with them in a non-judgemental manner. Findings imply that the most effective prevention approaches for this population may be those that target risk behaviours without focusing on disclosure of sexual identities.

Keywords: Black men, MSM, HIV/AIDS, sexual identity, hidden populations

Introduction

The primary HIV transmission category for Black men in the USA is sexual contact with other men (MSM), followed by high-risk heterosexual contact and injection drug use. For Black women, high-risk heterosexual contact and injection drug use are the most common means of infection. Recent data suggest that Black women are more likely than other women to have unidentified risk factors for HIV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2011). Most of these cases are reclassified by the CDC as heterosexual risk, and include women who may be unaware that their male partners have sex with other men. Black men who have sex with men and women (MSMW) who do not disclose their same-sex behaviour and are non-gay identifying (NGI) represent an important risk group in need of tailored services to increase their ability to protect themselves and their female partners.

In the USA, Black MSM are more likely than White MSM to also have sex with women and less likely to disclose their same-sex activity (CDC 2003; Kennamer et al. 2000; Malebranche 2003). Perceptions of homophobia prevent some Black MSMW from telling their female partners and others about their same-sex risk behaviour (CDC 2003; Kennamer et al. 2000; Stokes and Peterson 1998). Non-disclosure of bisexual practices to sexual partners is associated with higher rates of unprotected sex and with greater numbers of partners (Stokes et al. 1996), and is linked to increasing rates of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among female partners of Black MSMW (Dodge, Jeffries, and Sandfort 2008). Conversely, disclosure may empower partners, improve relationship quality and increase condom use (Malebranche 2003; Millett et al. 2005). Homophobic attitudes are often internalised and serve as a barrier to prevention and treatment-seeking (Peterson and Jones 2009). Homophobia and/or negative attitudes toward MSMW have also been observed among prevention and treatment providers, further discouraging high-risk men from participating in care (Washington and Brocato 2011).

Understanding the dynamics of disclosure and secrecy among non-gay identified (NGI) Black MSMW is potentially important for addressing ongoing racial disparities in HIV in the U.S.A., which continue to harm Black Americans disproportionately (CDC 2011). This fact drives a growing body of research on sexual risk-taking among Black MSMW, including enquiries into substance use (Harawa et al. 2008; Operario et al. 2011; Shoptaw et al. 2009) and homophobia (Shoptaw et al. 2009). However, the dynamics of disclosure and secrecy have not been well explored. Malebranche (2008; Malebranche et al. 2010) identifies methodological flaws in research to date with this hidden population, such as: the inclusion of few Black men in bisexual samples, including bisexual men in homosexual samples, inconsistent or absent definitions of ‘down low’ when researching behaviourally bisexual Black men, and conflating sexual behaviour with sexual identity. Our own review revealed a lack of attention to heterosexual relationship dynamics (i.e., casual vs. main female partner) and their relevance to understanding disclosure and risk (see Siegel et al. 2008 for an exception). We also found methodological differences between large (mainly quantitative) and small (mostly qualitative) studies with MSM. Non-gay identification was not a selection criterion for any of the larger studies, which did include substantial numbers of Black respondents (e.g., Bowers et al 2011; Fuqua et al. 2012; Gorbach et al. 2009; Rietmeijer et al. 1998; Shoptaw et al. 2009; Wheeler et al. 2008; Williams et al. 2009; Wolitski et al. 2006). Differences in sexual self-identity or imposed classification as MSM or MSMW tended to emerge in data collection and analyses generally focused on comparing sexual risk behaviour between these groups. Further, only two of those studies included measures of internalised homonegativity and degree of openness about same-sex behaviour in their analyses of differences among MSM groups (Shoptaw et al. 2009; Wolitski et al. 2006).

Smaller studies have been more likely to include non-gay identification among eligibility criteria (e.g., Harawa et al. 2008; Operario, Smith and Kegeles 2008; Siegel et al. 2008; Wheeler 2006). These and other studies (e.g., Dodge, Jeffries, and Sandfort 2008; Malebranche et al. 2010) recruited entirely Black samples. (Siegel et al. 2008 recruited diverse participants.) Our research joins these studies in attempting to better understand how NGI Black MSMW perceive risks associated with drug use and concealed same-sex behaviour as well as the risks entailed in disclosing that behaviour. Such knowledge can improve interventions to reach and engage men whose sexual risk behaviour is connected to substance use, and who may need and want drug treatment services or sexual health education but are not confident that counsellors will understand and respect their sexuality. This concern is not unfounded as researchers suggest that addiction counsellors often lack training in human sexuality (Washington and Brocato 2011). Moreover, existing HIV prevention interventions targeting African American MSM emphasise sexual identity and community involvement, topics with which NGI MSMW may not be comfortable (Operario et al. 2011).

Here we report on research activities and findings generated by a two-year study investigating the feasibility of recruiting NGI, non-disclosing Black MSMW to participate in research on substance use and HIV risk. We set out to locate and interview 30 men, to discover what they would be willing to share about the risks they incur, the context of their same-sex behaviour and the circumstances driving the need to conceal it. To help assess our recruitment strategy and to develop additional interview questions, our research design also included five focus groups (four non-gay identified; one consisting of gay-identified male casual partners of NGI MSMW). Because the focus groups generally confirmed our approach to venue selection and recruitment, and had some differences in eligibility criteria, this paper focuses on the individual interviews, which were completed with 33 men. After providing background information and the conceptual framework behind our recruiting methods, we describe recruitment efforts and present some preliminary findings related to participation and disclosure. We conclude with a discussion of the need for further research and some implications for outreach and prevention interventions for this population.

Methods

The principal activities in this investigation included: hiring field staff, identifying and choosing recruitment venues, establishing key informants, developing and refining the interview protocol, locating and recruiting eligible participants and administering the protocol to men who consented to interviews. Recruiting and interviewing took place between March and October 2009. The research design, interview protocols and informed consent documents were approved by the research institute’s institutional review board. We employed targeted and referral sampling, with initial contacts and/or key informants drawn from several types of settings in New York City (Watters and Biernacki 1989). We paid key informants US$10 for referring eligible respondents, as screened by the ethnographers. Eligibility criteria included self-identifying as a Black or African American male age 18 or older, use of illicit drugs and/or alcohol during the past 12 months, having a female primary sexual partner and having engaged in sexual activity with another man at least once in the past 12 months. Our use of a 12-month time frame for substance use was purposeful, to allow deeper exploration of risk behaviour and disclosure within the context of heterosexual relationships. Men who self-identified as gay or homosexual were excluded.

Requiring a primary female partner (i.e., main current sexual partner is female) distinguishes our study from other studies with MSMW, most of which simply require that participants have had sex with a female within a certain time period (for an exception, see Siegel et al. 2008). We wanted participants to have a primary female partner because one of our goals was to understand men’s decisions to conceal their same-sex encounters in the context of heterosexual relationship dynamics. Our previous studies included several households in which one partner or the other had outside sexual relationships that they concealed from their mates. But these relationships were with members of the opposite sex so there may be important differences. In some circles, men who have multiple female partners are lauded by their peers–so they may hide their outside female partners from their mates, but not from their male friends. But if these same men have male sex partners, and do not self-identify as gay, the situation is quite different. Their female partners may have heightened fear of becoming infected with HIV. And the men can expect rejection or ridicule from their male friends and female mates because of homophobia in parts of the Black community.

For non-disclosing Black MSMW, secrecy offers protection against stigma. However, the concealed behaviour is popularly described as down low, with widely perceived connotations of dishonesty and disregard for others. A central challenge for research with these men is to understand the impact of stigmatic socially constructed identities without unwittingly reinforcing the stigma (Ford et al. 2007). Cognisant of that challenge, the research team avoided using the term down low,’except when it was initiated by the men themselves (see below). It is also essential that recruiting and interviewing be carried out by people likely to be seen by the men as nonthreatening and non-judgemental. Our field staff included two Black male and two Black female ethnographers. Both of the men had prior experience in HIV-related field research and were familiar with relevant drug- and sex-related venues in New York. The two women are veterans of previous studies conducted by this research team in low-income African American communities in New York City. They have well-documented success in establishing the trust and rapport with male study participants needed to elicit in-depth narratives on highly personal experiences that are often illegal or stigmatising (Clatts and Sotheran 2000; Dunlap and Johnson 1999). Moreover, knowing that many if not most of the men in our studies have been raised by or lived with their mothers, sisters and aunts, we reasoned that men in this study would be willing to discuss their same-sex behaviour with women other than their female sex partners, such as our ethnographers, in a setting that assured confidentiality. Finally, men are unlikely to run into a female ethnographer casually in MSM settings; this avoids potential social awkwardness that might arise with male interviewers. Nevertheless, we were prepared to hire male replacements if gender proved to be a barrier to recruitment. That did not turn out to be necessary: the two female ethnographers recruited and interviewed 22 of the 33 men who completed individual interviews.

Interviewers asked specific screening questions based on eligibility criteria. Because all information was provided by self-report, we must rely on the interviewers’ judgement and skill at probing for authenticity. This was especially true regarding the men’s primary relationships with females. Given the nature of the study, direct observations were not feasible, so the interview instruments included several questions and probes about those relationships.

Participants

Table 1 displays participant characteristics. [Table 1 here] Additionally, all participants had female primary sex partners and had been in those relationships for an average of 3.4 years. Five participants (15%) were currently living with these partners, including one man who was married. For most participants, sexual encounters with other men were situational, occurring only under certain conditions. Several men reported having sex with men while incarcerated, for example, and a large number reported that substance use facilitated or influenced their same-sex encounters, sometimes in ways that increased risk (Benoit and Koken in press). The primary substances men reported using include alcohol, marijuana and crack or powder cocaine.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N=33)

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual self-identification | ||

| Bisexual | 18 | 54 |

| Heterosexual | 10 | 30 |

| Othera | 5 | 15 |

| Education | ||

| College degree | 5 | 15 |

| Some college | 16 | 48 |

| HS diploma/GED | 6 | 18 |

| Less than high school | 6 | 18 |

| Annual income | ||

| Less than $25,000 | 21 | 64 |

| More than $25,000 | 12 | 36 |

| Primary income source | ||

| Employment | 10 | 30 |

| Public benefits | 20 | 61 |

| Hustles/otherb | 3 | 9 |

| Criminal justice experience | ||

| Ever incarcerated | 17 | 51 |

| Ever arrested | 24 | 73 |

| HIV status (self-report) | ||

| Negative | 18 | 55 |

| Positive | 13 | 39 |

| Unknown | 2 | 6 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Never married | 23 | 70 |

| Separated/divorced | 7 | 21 |

| Widowed | 2 | 6 |

| Married | 1 | 3 |

Notes:

e.g., ‘freak’, ‘down low,’ or refused label.

Selling used clothing, selling drugs, borrowing from family and friends.

Locating the population

As a hidden population, non-disclosing MSMW have some things in common with illicit drug dealers, for whom ‘remaining “hidden” or “anonymous” to outsiders and “hiding” most of their behaviours from family, friends and associates are standard operating procedures’ (Dunlap and Johnson 1999, 129). Key informants can introduce ethnographers to potential study participants from hidden populations, and they may participate in initial conversations. After that, however, ethnographers must establish their own relationships of trust with eligible candidates. Conveying equality and respect is essential when working with Black men, who may be isolated from dominant society and whose social interactions may be circumscribed by agents of social control and penal institutions (Dunlap and Johnson 1999). Asking for one’s individual story does more than preserve the person’s inherent dignity; it also fosters the pragmatic research goal of moving beyond generalities in identifying and describing patterns of risk behaviour (Clatts and Sotheran 2000). This perspective recognises that NGI Black MSMW have diverse individual experiences and circumstances and so are not likely to be found in a single setting.

Drawing on the literature, previous ethnographic mapping, discussions with colleagues and community organisation contacts, we began with a list of potential recruiting venues in New York City, which we grouped into four categories: existing networks, known MSM venues, community organisations and Internet sources. Recruiting efforts took place in low-income neighbourhoods, particularly in Central Harlem and Brooklyn (Brownsville and Flatbush). Ethnographers also went to gay neighbourhoods (Greenwich Village and Chelsea), to find men who could refer them to NGI MSMW.

Existing neighbourhood networks

In previous research, we developed preliminary ethnographic maps in relevant neighbourhoods and we built on those to find men who are in relationships with women but also have sex with men. Staff ethnographers cultivated contacts made during research on interpersonal relationships in households involved in drug use and sales, and had access to dealers and others familiar with substance-using venues. For this study, the ethnographers went to stores, parks, shelters and known drug-using spots such as crack houses, shooting galleries, methadone programmes and pill-selling locations. They also had opportunities to reach men through friends, neighbours, other associates, and churches. Some men interviewed for this study were friends or former lovers of key informants who were known to ethnographers from earlier studies. Ethnographers called key informants or met them, explained the study and gave them flyers and cards. They also posted flyers on walls and bulletin boards, in stores and on lampposts outside of parks. They left flyers and cards in subways and gave them to existing contacts or to other people they approached.

Known MSM venues

We obtained a list of MSM venues such as bars, dance clubs, street locations, parks and sex parties, and added new locations to the list as we learned about them from contacts. Anticipating that many Black MSMW are reluctant to identify themselves with known gay or bisexual scenes (Operario et al. 2011; Schrimshaw, Siegel, and Downing 2010; Stokes and Peterson 1998), we were not certain that we would find participants in these settings, or, if we did, that they would be willing to talk. Given the relatively small scope and budget of the study, field staff targeted a small number of bars, parks and street locations and made repeated visits at varied hours (mostly afternoons and evenings, over a period of several weeks) to develop a sense of traffic patterns, to leave flyers and to cultivate key informants.

Groups and organizations

Members of the project team established relationships with community-based organisations and generated referrals by interviewing administrators and group representatives and by posting flyers (MacKellar et al. 2007; Schrimshaw, Siegel, and Downing 2010; Stokes and Peterson 1998; Wheeler 2006). Such organisations included prisoner re-entry programmes in Manhattan and Brooklyn, and a non-profit community organisation that provides HIV/AIDS testing and related services. We also recruited through treatment programmes and facilities that we knew hosted 12-step meetings, because individuals in recovery can refer friends and acquaintances who are not in treatment.

Internet sources

There are a number of Internet sites designed for homosexual, bisexual or ‘straight curious’ Black men. The Internet can yield larger numbers of respondents in less time than is possible with traditional street-based outreach. Although used mostly for surveys, it can also be used to recruit participants for one-on-one interviews (MacKellar et al. 2007; Schrimshaw, Siegel, and Downing 2010). We identified an appropriate website and purchased space for two advertising periods using two different banners promoting the study. A banner is a form of online advertising delivered by an ad server and embedded into a web page. The idea is to attract traffic to a website by persuading viewers to click on a link featured in the banner. The banners for the study included a link to the project website, which contained a description of the study along with an email address and telephone numbers so that men could contact us.

Contacting and engaging participants

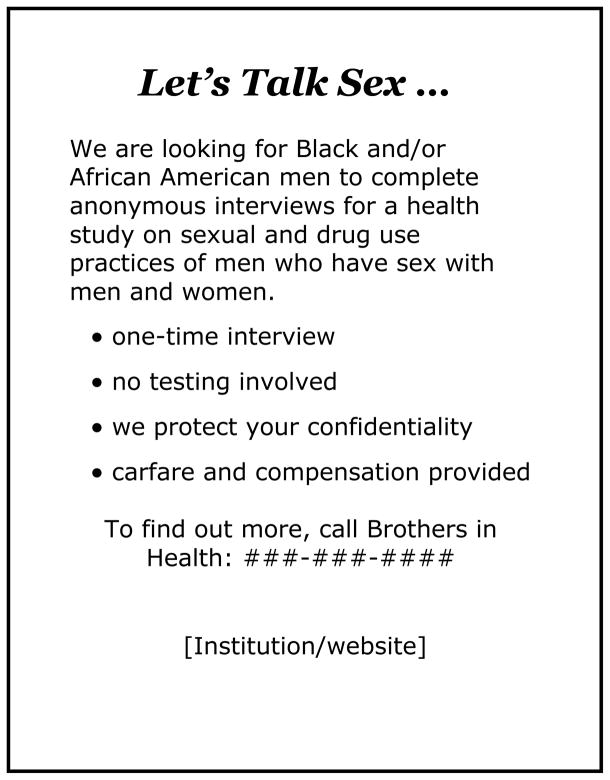

In all recruiting areas except the Internet, field staff distributed flyers and cards that were printed in various colours and with slight variations in text. In keeping with concerns about labelling and stigmatising, early versions did not include the term down low. Rather, flyers and cards began with the heading, ‘Let’s Talk Sex …’ followed by a brief description of the study, which mentioned the cash incentive and emphasised confidentiality. [Figure 1 here] We also produced a version with the heading, ‘Looking for Black and/or African American men who have sex with men and women.’

Figure 1.

Initial recruitment flyer

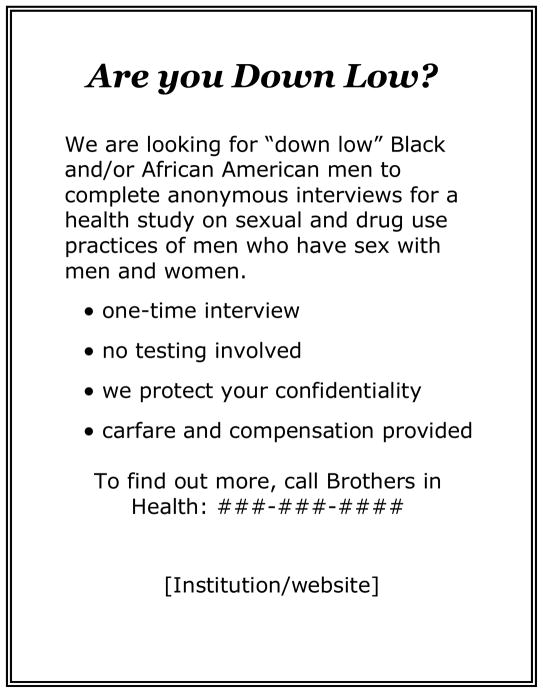

However, after ethnographers had spent some time in the field (approximately two months), met with some key informants and interviewed a few participants, they suggested using ‘down low’ language in some form. Most of the men were comfortable with the term, and a few lamented the way in which down low and ‘DL’ have been popularised by cultural figures such as Oprah Winfrey and R. Kelly. Only a handful of respondents said they would not apply the term to themselves, mainly because they rejected the idea of labels, but two men perceived negative implications in down low that they did not feel applied to them. Thus the next and final run of flyers and cards included some with variations on the theme, such as: ‘On the DL?’ and ‘Are you down low?’ [Figure 2] Regardless of the language used in the opening pitch, all flyers and cards included the names of the study and the research institute, the project website and contact information for the study.

Figure 2.

Revised recruitment flyer

The ethnographers established and followed a few common-sense ground rules for initial encounters when recruiting participants in public spaces: 1) avoid approaching groups of men; 2) do not approach a man who is with a woman; 3) ask a man if he knows someone who might be eligible for the study rather than asking him if he might be eligible and interested. Even then, staff had to be prepared for negative reactions, as one explained in field notes:

I used humour as a mechanism to bypass the uneasiness we both might be feeling … Sometimes my handouts were promptly handed back to me without comment. Some would hand it back to me like it was hot! I would laugh and this helped them to loosen up and laugh, chuckle, or tell me they don’t go that way! Some held onto the handout without explanation and others told me they would try to find someone for me.

Some men reacted negatively, verbally abusing the lifestyle or describing MSMW as ‘disgusting’, for taking the risk of bringing HIV home to their wives.

If a potential respondent or key informant did not walk away from the initial encounter, the next step was to break the ice. One male ethnographer found it useful to ask prospective participants and key informants what they did for a living, or to ask them about the work he had seen them doing, before explaining the study and asking for referrals. Some individuals who had offered to serve as key informants eventually disclosed that they qualified as respondents, often after having several casual conversations with the ethnographers over some period of time; this was traditional rapport building.

Interviews were conducted in private and public settings where respondents agreed they would feel safe. Private spaces included offices, participant homes, and vehicles; public settings included restaurants, park benches, and other outdoor spaces. It may seem counterintuitive to conduct confidential interviews in a public space; however, staff ethnographers have found that they can conduct interviews in parks and restaurants without being noticed, and will do so if respondents are comfortable and ambient noise is not excessive. Respondents provided informed consent and chose code names before beginning the interviews, which were digitally recorded. After obtaining demographic information, we asked 20 open-ended questions covering a range of topics: sexual experiences with men and women, including safe-sex practices; alcohol and drug use; their sexual histories; relationships with primary female partners and attitudes toward disclosure to those partners and to others; perceptions of sexual identity and motivations for NGI men to have sex with other men.

Analysis

Ethnographers wrote field notes with detailed descriptions of recruiting efforts in all locations. Notes from biweekly staff meetings provided a record of progress and challenges throughout the project. In focus groups and individual interviews we asked men where to find eligible participants and we compared their answers with our lists and notes. These materials were analysed through an iterative process in which the lead author consolidated records and summarised the study’s methodological trajectory, then submitted a written draft to field staff for review and corrections; these were then incorporated into a revised draft. Two rounds of this process yielded a final draft.

Interviews were transcribed and entered into FileMaker Pro, a relational database program for managing qualitative data. Analysis was influenced by phenomenology and grounded theory, which allow conceptual frameworks to emerge from lived experiences related in participants’ own language (Charmaz 2006). Project analysts read individual interview transcripts several times and coded them initially by key words and phrases drawn verbatim from the transcript. On subsequent passes, initial codes and emerging patterns were compared until categories became clear. In this paper, analysis focuses on questions addressing men’s willingness to be interviewed.

Results

Overall, recruiting was less difficult and men were more willing to talk than anticipated. Field staff approached more than 100 men and distributed approximately twice that number of flyers. Most inquiries were refused, but some men took flyers and referred participants or later called the ethnographers themselves, if they believed they were eligible. Table 2 summarises recruitment results. [Table 2 here.] Community outreach methods–neighbourhood networking and community-based organizations–were the most successful. In neighbourhood recruiting, ethnographers sometimes worked through existing contacts to gain access to key informants. Success in community organisations most likely stems from having established contacts and making carefully targeted choices.

Table 2.

Recruitment Sources (N=33)

| Recruiting source | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Flyers/handouts | 9 | 27 |

| Peer referrals | 9 | 27 |

| Informant networks | 7 | 21 |

| Community organisations | 5 | 15 |

| Internet | 2 | 6 |

| Missing data | 1 | 3 |

Field staff found some respondents through known MSM meeting places at street locations and parks, but only one at a bar, despite several visits to places that initially appeared promising. Based on this experience and that of colleagues, it may be that the bar scene is more conducive to interventions or other research, where patrons are recruited on the spot for rapid testing or brief surveys. Securing interest and commitment to in-depth interviews to be conducted at a later time proved to be more difficult. One ethnographer had ties to the fashion industry and access to parties, which yielded a handful of referrals but only one completed interview.

The Internet was our least successful recruiting avenue. Although we received several calls from men who had seen our banner ad, only two followed through with an interview. We began asking other participants about finding sexual partners on websites and several told us that they do not use the Internet to seek male partners. One who called himself L, age 23, cited safety: ‘They could be dangerous, they could have weapons, they could be psychotic or they could be out to kill you. They could be out to steal from you… anything is possible.’ Timeless, age 40, did not like having to go through written introductions online: ‘If I was on the street and we was vibe-ing and if it was going to go there, you already seen me, I’ve already seen you and it’s like I don’t really have to ask you too much.’

Reasons for participation

Because a key aim of the study was to test the feasibility of recruiting men to discuss experiences they ordinarily do not disclose, early in the interview (Question 1 after demographics) we asked men why they agreed to talk with us. At the end of the interview (Question 20), we asked them how they felt about the questions and the interview experience. Responses to both questions fell into three general categories: for the money, to help others, and to unburden the conscience.

For the money

We offered a relatively generous incentive of US$45 for an interview lasting approximately one hour. This payment was a frequently cited motivator, perhaps not surprising given the relatively low incomes of the participants, but only in response to Question 1. Of 33 participants, nine (27%) cited money as the primary motivator and eight (24%) mentioned money as a secondary factor. Thus 73% had a primary reason for participating other than money and nearly half the sample (49%) did not mention money at all.

To help others

Respondents were aware that the study concerned substance use and HIV risk. Both at the beginning (n=12) and at the end of the interview (n= 6), men perceived an opportunity to contribute to research that is relevant to them and to their community. As Derek, age 43, explained: ‘[I]t’s the data that I can give or the information that I can give, you know, to help the next person … information that, hopefully, will benefit a peer or someone else.’ Outstanding, 47, emphasised the chance to help other non-disclosing men deal with secrecy and guilt:

It might be enlightening others to certain areas and to make people comfortable and to be all right with themselves and with others when they hear that these are men really telling what time it is without having any [identity] tied to it. So you can’t identify them. And so guys hear this thing and it will really help them get better with where they are. Because I tell you, silence is a killer.

This same participant highlighted the liberating benefit of anonymity. Respondents also frequently cited trust in the interviewer as a factor in their comfort level. As C-Man, age 50, said, ‘I don’t have a problem talking about me because I’m not being judged.’ At the end of the interview, several men who initially had been reluctant to speak made comments such as, ‘I opened up because of the way you handled it.’

Need to talk

The lack of judgement and promise of confidentiality helped some men see the interview as an opportunity to relieve some emotional burden. Several made comments such as, ‘… the reality is that sometimes you need to talk about it’ (John, 57) and, ‘maybe it clears the conscience’ (Robert, 53). For some, such as 42-year-old Barney, it was a fairly rare opportunity: ‘Because I know that I’m bisexual and I’ve been dealing with this for a while … and it is something I just want to really talk about … It’s a lot of stigma so a lot of times I can’t really be open about my sexuality.’

Zerox, age 57, readily agreed to be interviewed, so long as the conversation was confidential. At the end, he sounded as if he had opened up even more than planned:

It was interesting and it was enjoyable … [especially] the chance for me to speak to someone else … and admit to myself what I am because for a long time I was in denial … I couldn’t believe that I had been having sex with both men and women. This has brought me further out to realising the inner me.

For this participant, the ‘inner me’ may refer to his self-identification as bisexual. Like many other participants, he reported that his public self-presentation is heterosexual; he is married to his female partner, who does not know about his same-sex encounters. His point about self-realisation was echoed by other men, particularly at the end of the interview when they could reflect on the feelings evoked by the questions.

Some respondents, such as Sean, age 43, found the interview useful as a prompt to reconsider some of their decisions about risk-taking:

[I]t gave me more of a perspective to look at my behaviours and the people that I’m involved with and to take some things into consideration like, hey, maybe we should use a condom or maybe there is a certain dialogue we should have before we have sex this next time, about some things we need to share with one another.

Overall, men cited the need to talk as a motivating factor twice as often at the end of the interview (n=14) as the beginning (n=7).

Disclosure

In order to participate in the study, men had to be willing to tell us about behaviour that they conceal from others. This required a certain capacity of our research team to not only reach these men in the field, but to engage them in a dialogue that many had been reluctant to consider until now. During the interview, we asked men if they ever talk with anyone else about their same-sex activities. Only a few men said they could openly talk about their experiences with more than one person or anyone other than another non-disclosing man. However, the most common response was: only with ‘other men friends that I know is doing what I’m doing,’ as one man put it. Others said they have disclosed only to one person, such as a best friend or a psychotherapist. About one-third of the respondents said they do not have anyone at all with whom they can talk about having sex with other men. These participants, the ones who are the most isolated socially, highlight the importance of understanding the pressures to conceal same-sex behaviour among NGI Black men who may also be using alcohol or other substances as a coping mechanism.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that NGI Black MSMW who feel compelled to conceal sexual risk behaviour will nevertheless talk openly about their experiences to interviewers with whom they feel comfortable and in non-threatening settings. Indeed, participant comments about wanting to discuss their concerns and having no place to do so suggest an unmet need and a public health outreach opportunity. For these men, the decision to talk may reflect a struggle between their concerns for the safety of their partners and themselves and their fear of being stigmatised and ostracised if their same-sex behaviour were to be exposed. The extent to which these men internalise homophobic community norms may be suggested by ways in which they discussed sexual identity. Most of our respondents said they would apply the term ‘down low’ to themselves, and most believe they are considered to be heterosexual by their community (which is their goal). Half of the respondents said they consider themselves bisexual, a few more than those who said they consider themselves heterosexual. It is also important to note that some respondents rejected the idea of sexuality labels all together. It may be that the bisexual men are most comfortable internally with their sexuality, but feel compelled to secrecy because they see bisexuality as a stigmatised identity. Whether men separate their personal sexual identities from their sexual activity, choose not to adopt a personal sexual identity, or see themselves in a way that they feel is stigmatised by others, the concept of sexual identity is problematic for efforts to develop effective prevention strategies for this population.

Our findings add to a growing body of qualitative research that has successfully reached and engaged NGI MSMW to understand how these men perceive their HIV risks associated with drug use and/or concealed same-sex behaviour (e.g., Dodge, Jeffries, and Sandfort, 2008; Harawa et al. 2008; Malebranche et al., 2010; Operario, Smith, and Kegeles, 2008; Siegel et al., 2008). Our ethnographers connected with this population through several critical sources including social networks, both directly (i.e., peer referrals) and indirectly (i.e., informants). Given the relative success of using networks and community organisations in this study, future ethnographic efforts might consider respondent driven sampling (RDS), which has been used with previously unreachable, drug-using and sexual minority populations (e.g., Gorbach et al., 2009; Heckathorn, 1997; Wheeler et al., 2008). Although most of our participants reported being socially isolated by their same-sex behaviour, nine men (27%) were referred to us by peers. Perhaps because our goal was 30 respondents, these peer referral chains were very short. However, some larger studies have successfully used RDS to recruit Black MSM (Fuqua et al. 2012; Gorbach et al. 2009; Shoptaw et al. 2009; Williams et al. 2009), and it may work with NGI Black MSMW as well.

The findings should be interpreted within the context of the study’s limitations. First, the Internet was not a successful recruitment strategy, although other studies have been able to reach non-disclosing, NGI MSMW in this way (Schrimshaw, Siegel, and Downing 2010). A possible explanation for this finding was our use of banner advertisements, which can have low response rates among NGI MSMW, particularly men of colour (see Bowen 2005; Sullivan et al. 2011). Our findings also suggest that reaching this population through advertising on personals websites may be complicated by safety concerns that some men have about using the Internet to meet male partners for sexual encounters (i.e., if they do not use these websites to meet male partners, they will not see our banner advertisements). Finally, the sample is not necessarily representative of the Black MSMW population. It may be older and have a disproportionately lower income because of the nature of community connections developed by the research team. However, we now have valuable information on several types of settings and mechanisms that will be used to systematically recruit larger samples in subsequent studies.

Results have implications for effective outreach, treatment and prevention efforts. Our experience with flyers demonstrated that the term down low is not offensive to all potential participants; rather, some men perceived positive connotations. Although the term should be used with caution, future research and outreach efforts targeting this population might increase participation rates by using a mix of recruiting material, some with the term and some without.

Participants trusted the ethnographers to protect their confidentiality and appreciated not being judged, something they should also expect in a public-health setting. Recruiting worked best where ethnographers could capitalise on connections and spend time developing rapport with potential participants. Such connections–for example, key informants from target participants’ social networks or community organisations–can aid outreach workers and other researchers by providing trusted introductions that ease the process of engaging the participants. Also, respondents were apparently as comfortable with female interviewers as with men, suggesting that a genuinely non-judgemental approach can overcome expected gender barriers.

All of these elements of successful recruitment for research should also contribute to effective outreach. The most effective prevention messages for this population may be those that target specific risk behaviours without focusing on sexual identities. Some research has shown that disclosure of sexual orientation is not necessarily beneficial to one’s health (Huebner and Davis 2005; Kuyper and Fokkema 2011). Ongoing efforts to improve sensitivity training for providers should emphasise the fluid nature of sexual identity and the role of stigma as a potential barrier to treatment.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (R03DA024997; T32DA007233). Points of view in this paper do not represent the official position of the U.S. Government, NIDA, or NDRI. We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Eloise Dunlap and Bruce D. Johnson, Donte Clark-Davis, Jennifer Morris and Samantha Wilkinson, and the men who entrusted us with highly personal information and concerns.

References

- Benoit E, Koken JA. Perspectives on substance use and disclosure among behaviorally bisexual Black men with female primary partners. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2012.735165. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen A. Internet sexuality research with rural men who have sex with men: can we recruit and retain them? Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42:317–23. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers JR, Branson CM, Fletcher J, Reback CJ. Differences in substance use and sexual partnering between men, men who have sex with men and women and transgender women. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2011;13:629–642. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.564301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV/STD risks in young men who have sex with men who do not disclose their sexual orientation -- six U.S. cities, 1994-2000. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2003;52:81–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. HIV surveillance report, 2009. 2011;21 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/ [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: SAGE Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Clatts MC, Sotheran JL. Challenges in research on drug and sexual risk practices of men who have sex with men: applications of ethnography in HIV epidemiology and prevention. AIDS and Behavior. 2000;4:169–79. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge B, Jeffries WL, Sandfort TGM. Beyond the down low: sexual risk, protection and disclosure among at-risk Black men who have sex with both men and women (MSMW) Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:683–96. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9356-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E, Johnson BD. Gaining access to hidden populations: Strategies for gaining cooperation of drug sellers/dealers and their families in ethnographic research. Drugs & Society. 1999;14:127–49. doi: 10.1300/J023v14n01_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CL, Whetten KD, Hall SA, Kaufman JS, Thrasher AD. Black sexuality, social construction, and research targeting ‘the down low’ (‘the DL’) Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17:209–16. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua V, Chen Y, Packer T, Dowling T, Ick TO, Nguyen B, Colfax GN, Raymond HF. Using social networks to reach Black MSM for HIV testing and linkage to care. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(2):56–265. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9918-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbach PM, Murphy R, Weiss RE, Hucks-Ortiz C, Shoptaw S. Bridging Sexual Boundaries: Men who have sex with men and women in a street-based sample in Los Angeles. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86(1):S63–S75. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harawa NT, Williams JK, Ramamurthi HC, Manago C, Avina S, Jones M. Sexual behavior, sexual identity, and substance abuse among low-income bisexual and non-gay-identifying African American men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:748–62. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9361-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1997;44:174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Davis MC. Gay and bisexual men who disclose their sexual orientations in the workplace have higher workday levels of salivary cortisol and negative affect. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;30:260–67. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3003_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennamer JD, Honnold J, Bradford J, Hendricks M. Differences in disclosure of sexuality among African American and White gay/bisexual men: Implications for HIV/AIDS prevention. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:519–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyper L, Fokkema T. Minority stress and mental health among Dutch LGBs: Examination of differences between sex and sexual orientation. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:222–33. doi: 10.1037/a0022688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKellar DA, Gallagher KM, Finlayson T, Sanchez T, Lansky A, Sullivan PS. Surveillance of HIV risk and prevention behavior of men who have sex with men -- A national application of venue-based, time-space sampling. Public Health Reports. 2007;122(Supplement 1):39–47. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ. Black men who have sex with men and the HIV epidemic: Next steps for public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:862–64. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ. Bisexually active Black men in the United States and HIV: Acknowledging more than the “Down Low”. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:810–816. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ, Arriola KJ, Jenkins TR, Dauria E, Patel SN. Exploring the ‘bisexual bridge’: A qualitative study of risk behavior and disclosure of same-sex behavior among Black bisexual men. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:159–64. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Malebranche DJ, Mason B, Spikes P. Focusing ‘down low:’ Bisexual Black men, HIV risk and heterosexual transmission. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97:52S–59S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Operario D, Smith C, Kegeles S. Social and psychological context for HIV risk in non-gay-identified African American men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2008;20:347–59. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Operario D, Smith C, Arnold E, Kegeles S. Sexual Risk and Substance Use Behaviors Among African American Men Who Have Sex with Men and Women. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15:576–83. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9588-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Jones KT. HIV Prevention for Black Men who have sex with men in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:976–80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietmeijer C, Wolitski RJ, Fishbein M, Corby NH, Cohn DL. Sex hustling, injection drug use, and non-gay identification by men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1998;25(7):353–360. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199808000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrimshaw EW, Siegel K, Downing MJ., Jr Sexual risk behaviors with female and male partners met in different sexual venues among non-gay-identified, nondisclosing MSMW. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2010;22:167–79. doi: 10.1080/19317611003748821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, Weiss RE, Munjas B, Hucks-Ortiz C, Young SD, Larkins S, Victorianne GD, Gorbach PM. Homonegativity, substance use, sexual risk behaviours, and HIV status in poor and ethnic men who have sex with men in Los Angeles. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2009;86:S77–91. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9372-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel K, Scrimshaw EW, Lekas HM, Parsons JT. Sexual behaviors of non-gay identified non-disclosing men who have sex with men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:720–35. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9357-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes JP, McKirnan DJ, Doll L, Burzette RG. Female partners of bisexual men: What they don’t know might hurt them. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1996;20:267–84. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes JP, Peterson JL. Homophobia, self-esteem and risk for HIV among African American men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1998;10:278–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, Khosropour CM, Luisi N, Amsden M, Coggia T, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Bias in online recruitment and retention of racial and ethnic minority men who have sex with men. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2011;13:e38. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington TA, Brocato J. Exploring the perspectives of substance abusing Black men who have sex with men and women in addiction treatment programs: A need for a human sexuality educational model for addiction professionals. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2011;5:402–12. doi: 10.1177/1557988310383331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watters JK, Biernacki P. Targeted sampling: Options for the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1989;36:416–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DP. Exploring HIV prevention needs for nongay-identified Black and African American men who have sex with men: A qualitative exploration. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33:S11–16. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000216021.76170.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler D, Lauby J, Liu K, Sluytman L, Murrill C. A Comparative Analysis of Sexual Risk Characteristics of Black Men Who Have Sex with Men or with Men and Women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:697–707. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CT, Mackesy-Amiti ME, McKirnan DJ, Ouellet LJ. Differences in sexual identity, risk practices, and sex partners between bisexual men and other men among a low-income drug-using sample. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86(1):S93–S106. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9367-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitski RJ, Jones KT, Wasserman JL, Smith JC. Self-Identification as “Down Low” Among Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) from 12 US Cities. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(5):19–529. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]