Abstract

The tumor suppressors EXT1 and EXT2 are associated with hereditary multiple exostoses and encode bifunctional glycosyltransferases essential for chain polymerization of heparan sulfate (HS) and its analog, heparin (Hep). Three highly homologous EXT-like genes, EXTL1–EXTL3, have been cloned, and EXTL2 is an α1,4-GlcNAc transferase I, the key enzyme that initiates the HS/Hep synthesis. In the present study, truncated forms of EXTL1 and EXTL3, lacking the putative NH2-terminal transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains, were transiently expressed in COS-1 cells and found to harbor α-GlcNAc transferase activity. EXTL3 used not only N-acetylheparosan oligosaccharides that represent growing HS chains but also GlcAβ1–3Galβ1-O-C2H4NH-benzyloxycarbonyl (Cbz), a synthetic substrate for α-GlcNAc transferase I that determines and initiates HS/Hep synthesis. In contrast, EXTL1 used only the former acceptor. Neither EXTL1 nor EXTL3 showed any glucuronyltransferase activity as examined with N-acetylheparosan oligosaccharides. Heparitinase I digestion of each transferase-reaction product showed that GlcNAc had been transferred exclusively through an α1,4-configuration. Hence, EXTL3 most likely is involved in both chain initiation and elongation, whereas EXTL1 possibly is involved only in the chain elongation of HS and, maybe, Hep as well. Thus, their acceptor specificities of the five family members are overlapping but distinct from each other, except for EXT1 and EXT2 with the same specificity. It now has been clarified that all of the five cloned human EXT gene family proteins harbor glycosyltransferase activities, which probably contribute to the synthesis of HS and Hep.

Heparan sulfate (HS) is a glycosaminoglycan (GAG) found abundantly on the surfaces of most cells and in the extracellular space as proteoglycans (1). HS proteoglycans are known to function as cofactors in a variety of biological processes such as cell adhesion, blood coagulation, angiogenesis, morphogenesis, and regulation of growth factors and cytokine effects (2). Most, if not all, of their biological activities are assumed to be attributable to the HS side chains that interact with diverse protein ligands through specific saccharide sequences (3). Recent evidence indicates that HS chains are critically involved in the development of Drosophila melanogaster by interacting with signaling molecules, including Hedgehog, Wingless, and fibroblast growth factor, and HS deficiency causes severe malformation in developing fly (4, 5) and mouse (6) embryos.

In addition to HS and its analog, heparin (Hep), chondroitin sulfate (CS) and dermatan sulfate (DS) also are synthesized on the common GAG–protein linkage region, GlcAβ1–3Galβ1–3Galβ1–4Xylβ1-O-Ser (7), which is formed by the addition of xylose to specific Ser residues, followed by the addition of two Gals and GlcA, each reaction being catalyzed by the respective, specific glycosyltransferase:xylosyltransferase, Gal transferases I and II, and GlcA transferase I (GlcAT-I) (1, 8). Chain polymerization for HS/Hep is initiated once an α-GlcNAc is transferred to this linkage-region tetrasaccharide core by the action of α-GlcNAc transferase I (GlcNAcT-I) (9), whereas β-GalNAc transfer triggers CS/DS synthesis (10, 11). The first hexosamine transfer, therefore, is considered to be the critical determining step in which the HS/Hep and CS/DS chains are selected. After attachment of the first α-GlcNAc residue, the resultant nascent pentasaccharide is elongated further by alternate additions of GlcA and GlcNAc to form HS/Hep backbones by the actions of copolymerases, which exhibit dual catalytic activities of GlcA transferase II (HS-GlcAT-II) and α-GlcNAc transferase II (GlcNAcT-II) (8). Such HS/Hep precursor chains subsequently are modified through a series of reactions of N-deacetylation/N-sulfation of GlcNAc, epimerization of GlcA, and O-sulfation at various positions of both residues (2), which confers the structural diversity on HS/Hep.

Recently, two independent studies revealed the connection between HS-synthesizing glycosyltransferases and an EXT gene family of tumor suppressors: (i) identification of EXT1 as the gene that is capable of restoring HS synthesis in HS-deficient mutant cells (12) and (ii) identification of EXT2 by direct peptide sequencing of HS copolymerase purified from bovine serum (13). EXT1 and EXT2 are associated with the development of hereditary multiple exostoses (HME), an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by aberrant bone formation most commonly originating from the juxtaepiphyseal regions of the long bones (14–16). More recent studies have established firmly that recombinant forms of EXT1 and EXT2 indeed have both GlcNAc and GlcA transferase activities (17) and form an EXT1/EXT2 heterooligomeric complex in the Golgi apparatus (17–19) to yield a more active, biologically relevant enzyme form (17, 18). It should be noted that deficiency of either EXT1 or EXT2 causes HME (15, 16). These findings indicate that both EXT1 and EXT2 are essential glycosyltransferases for HS biosynthesis.

However, three EXT-like genes homologous to EXT genes have been isolated: EXTL1, EXTL2/EXTR2, and EXTL3/EXTR1 (20–23). Their chromosomal locations imply that they also might be tumor suppressors (20, 21, 24, 25), although they are not linked with HME. EXTL2 protein is an N-acetylhexoaminyltransferase that transfers not only GalNAc but also GlcNAc to the common linkage-region core tetrasaccharide through α1,4-linkage and is a strong candidate for the key enzyme leading to HS/Hep biosynthesis, segregating it from CS/DS biosynthesis (26). Identification of EXTL2 as GlcNAcT-I for HS/Hep synthesis suggested that other EXT-like genes also have some roles in HS formation. In the present study, soluble forms of EXTL1 and EXTL3 were transiently expressed in COS-1 cells and their glycosyltransferase activities were revealed.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

UDP-[3H]GlcNAc (60 Ci/mmol), UDP-[U-14C]GlcA (285.2 mCi/mmol), and UDP-[3H]GalNAc (10 Ci/mmol) were purchased from NEN. Unlabeled UDP-GlcNAc, UDP-GlcA, and UDP-GalNAc were supplied by Sigma. Flavobacterium heparinum heparitinase I, jack bean β-N-acetylhexosaminidase, and chondroitin were obtained from Seikagaku Kogyo (Tokyo). N-Acetylchondrosine was a gift from Keiichi Yoshida (Seikagaku Kogyo). The linkage-region tetrasaccharide-serine, GlcAβ1–3Galβ1–3Galβ1–4Xylβ1-O-Ser, was synthesized chemically as described previously (27). N-Acetylheparosan oligosaccharide acceptors derived from the capsular polysaccharide of Escherichia coli K5, GlcAβ1–4GlcNAcα1-(4GlcAβ1–4GlcNAcα1-)n with the nonreducing terminal GlcA and GlcNAcα1-(4GlcAβ1–4GlcNAcα1-)n with the nonreducing terminal GlcNAc, were prepared as described previously (28). GlcAβ1–3Galβ1-O-C2H4NHCbz was synthesized chemically (H. Shimakawa, Y. Kano, H.K., J.T., J. D. Esko, and K.S., unpublished results). A Nova-Pak C18 column (3.9 × 150 mm) and a Superdex peptide HR 10/30 column were supplied by Waters and Amersham Pharmacia, respectively.

Construction of the Expression Vector pEF-BOS/IP.

An 894-bp cDNA fragment containing the insulin signal sequence and the protein A sequence was cleaved from pGIR201protA (29) by NheI digestion and then inserted into the XbaI site of the expression vector pEF-BOS (30) to prepare pEF-BOS/IP. A DNA insert of interest was ligated into the BamHI site derived from pGIR201protA for expression as described below.

Construction of Soluble Forms of EXTL1 and EXTL3.

The cDNA fragment encoding a truncated form of EXTL1, lacking the NH2-terminal first 75 aa, was amplified with the first-strand cDNA transcribed from human adult brain poly (A)+ RNA (Biochain Institute, San Leandro, CA) as a template by PCR by using a 5′ primer (5′-ATTGATCACATGGTGGCAGCTGCAACTG-3′) containing an in-frame BclI site and a 3′ primer (5′-CGTGATCAGCTGGCTGACATGATAGGTT-3′) containing a BclI site located 115 bp downstream of the stop codon. PCR was carried out with Pfu polymerase by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 52°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 240 sec. A fragment of the expected size was excised, purified, and ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), and then the recombinant vector was introduced into the Subcloning Efficiency DM1 competent cells (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The inserted EXTL1 fragment was recovered by digestion with BclI and religated into the BamHI site of the expression vector pEF-BOS/IP, resulting in the fusion protein that had the cleavable insulin signal sequence for secretion and protein A for purification.

The cDNA fragment encoding a truncated form of EXTL3 lacking the NH2-terminal first 90 aa was amplified with the previously cloned EXTL3 cDNA (23) as a template by PCR by using a 5′ primer (5′-CGAGATCTGAAGAGCTCCTGCAGCTGGA-3′) containing an in-frame BglII site and 3′ primer (5′-CGAGATCTTCTGCTCATCCTCTTCCCCAG-3′) containing a BglII site located 37 bp downstream of the stop codon. PCR was carried out by using Pfu polymerase with 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 56°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 300 sec. The amplified fragments were digested with BglII and cloned into the BamHI site of pEF-BOS/IP.

Expression of the Soluble Forms of EXTL1 and EXTL3 in COS-1 Cells.

Each expression plasmid (6.7 μg) was transfected into COS-1 cells on 100-mm plates by using FuGENE6 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Tokyo) according to the instructions supplied by the manufacturer. Two days after transfection, 1 ml of the medium was collected and the secreted fusion protein was purified by incubation with 10 μl of IgG-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia) for 2 h at 4°C. The beads recovered by centrifugation were washed with each assay buffer described below, resuspended in the same buffer, and then tested for glycosyltransferase activities. For GlcNAc transferase assays, the reaction mixture of a total volume of 20 μl contained 10 μl of the resuspended beads, 100 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid-NaOH (pH 6.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, GlcAβ1–3Galβ1-O-C2H4NHCbz (250 nmol), or tetrasaccharide-serine (1 nmol) for GlcNAcT-I assay (31) or N-acetylheparosan oligosaccharides with the nonreducing terminal GlcA (20 μg) for GlcNAcT-II assay (32) as acceptors, and 250 μM UDP-[3H]GlcNAc (about 1.1 × 106 dpm). Enzyme assays for GlcAT-I (33), HS-GlcAT-II (32), and α-GalNAc transferase (34), βGalNAc transferase for CS chain elongation (35), and GlcA transferase for CS chain elongation (CS-GlcAT-II) (8, 36) were carried out as described previously.

Identification of the Enzyme-Reaction Products.

The products from the GlcNAcT-I reaction when using GlcAβ1–3Galβ1-O-C2H4NHCbz were isolated by hydrophobic HPLC on a Nova-Pak C18 column in an LC-10AS system (Shimadzu) (31). The column was developed with H2O for 15 min at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min at room temperature; thereafter, a linear gradient was applied to increase the methanol concentration from 0% to 100% over a 5-min period. The column then was developed isocratically with 100% methanol for 20 min. The radioactive peak containing the product was pooled and evaporated to dryness. The dried sample (about 40 pmol) was incubated with either 9 milliunits of β-N-acetylhexosaminidase in a total volume of 20 μl of 50 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5) or with 10 milliunits of heparitinase I in a total volume of 50 μl of 20 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 2 mM calcium acetate at 37°C overnight. Each enzyme digest was analyzed by using the same Nova-Pak C18 column as noted above.

GlcNAcT-II-reaction products of EXTL1 and EXTL3 were chromatographed individually by gel-filtration on a Superdex peptide HR 10/30 column (10 × 30 mm) by using 0.2 M NH4HCO3 as an eluant, and the fractions containing radioactive products were pooled and evaporated until the ammonium salt became invisible with the intermittent addition of H2O. An aliquot (about 36 pmol) of each purified product was incubated with either 9 milliunits of β-N-acetylhexosaminidase in a total volume of 20 μl of 50 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5) or with 10 milliunits of heparitinase I in a total volume of 100 μl of 20 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 2 mM calcium acetate at 37°C overnight. Each digest was analyzed again by using the same Superdex peptide column as described above.

Results

EXTL1 Is a Likely α1,4-GlcNAc Transferase for the Synthesis of the Repeating Disaccharide Region of HS.

The soluble form of EXTL1, which lacks the putative transmembrane domain and is fused with the cleavable insulin signal and protein A sequences, was transiently expressed in COS-1 cells. The expressed fusion protein was purified for separation from endogenous glycosyltransferases by incubating with IgG-Sepharose, which specifically binds to protein A. Its sugar transferase activities were examined by using various oligosaccharides as acceptors and radioactive UDP-sugars as donors. A significant amount of GlcNAc was transferred from UDP-[3H]GlcNAc to N-acetylheparosan oligosaccharides GlcAβ1–4GlcNAcα1-(4GlcAβ1–4GlcNAcα1-)n (Table 1). In contrast, the enzyme did not transfer GlcA from UDP-[14C]GlcA to N-acetylheparosan oligosaccharides GlcNAcα1-(4GlcAβ1–4GlcNAcα1-)n or to the linkage region trisaccharide Galβ1–3Galβ1–4Xyl, which is the acceptor for GlcAT-I (33). Neither GlcAβ1–3Galβ1–3Galβ1–4Xylβ1-O-Ser nor GlcAβ1–3Galβ1-O-C2H4NHCbz, a substrate for GlcNAcT-I (31), was used as an acceptor. Because mammalian chondroitin-synthesizing enzymes have not been cloned, β-GalNAc and GlcA transferase activities (35, 36) were measured by using chondroitin as an acceptor and UDP-GalNAc or UDP-GlcA as a donor substrate, but no activity was detected. N-Acetylchondrosine, GlcAβ1–3GalNAc, which is an acceptor substrate for the unique α-GalNAc transferase activity of EXTL2 (26, 34), did not serve as an acceptor either. The above α-GlcNAc transferase activity of EXTL1 was confirmed by the control transfection experiment, where no transferase activity was detected in the medium from COS-1 cells transfected with the empty expression vector without EXTL1. Thus, EXTL1 harbored GlcNAcT-II activity that can add GlcNAc to N-acetylheparosan oligosaccharides, but no other catalytic activities were tested.

Table 1.

Acceptor substrate specificity of glycosyltransferases attributable to soluble, truncated forms of EXTL1 and EXTL3

| Acceptor sugar [Donor] | EXTL1 | EXTL3 |

|---|---|---|

| Activity,* pmol/ml medium per h

| ||

| GlcAβ1-3Galβ1-O-C2H4NHCbz [UDP-GlcNAc] | ND | 746 |

| GlcAβ1-3Galβ1-3Galβ1-4Xylβ1-O-Ser [UDP-GlcNAc] | ND | ND |

| N-Acetylheparosan oligosaccharides with the nonreducing terminal GlcA† [UDP-GlcNAc] | 44‖ | 219‖ |

| N-Acetylheparosan oligosaccharides with the nonreducing terminal GlcNAc‡ [UDP-GlcA] | ND** | ND** |

| Chondroitin§ [UDP-GalNAc] | ND | ND |

| Chondroitin§ [UDP-GlcA] | ND | ND |

| Galβ1-3Galβ1-4Xyl [UDP-GlcA] | ND | ND |

| N-Acetylchondrosine¶ [UDP-GalNAc] | ND | ND |

ND, not detected (<0.5 pmol/ml medium per h).

The values represent the averages of two independent experiments.

GlcAβ1-4GlcNAcα1-(4GlcAβ1-4GlcNAcα1-)n.

GlcNAcα1-(4GlcAβ1-4GlcNAcα1-)n.

A mixture of GlcAβ1-(3GalNAcβ1-4GlcAβ1-)n and GalNAcβ1-(4GlcAβ13GalNAcβ1-)n. Under the conditions, the chondroitin-synthesizing enzyme system (11, 35, 36) as a positive control showed marked activities of CS-GlcAT-II and GalNAcT-II.

GlcAβ1-3GalNAc.

When truncated EXT1 was used for the positive control, the measured activity was 539 pmol/ml medium per h.

When truncated EXT1 was used for the positive control, the measured activity was 111 pmol/ml medium per h.

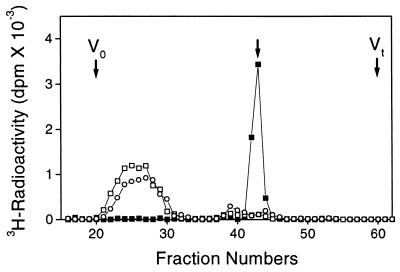

To identify the EXTL1-reaction products, N-acetylheparosan oligosaccharides labeled with [3H]GlcNAc were isolated by gel filtration and subjected to digestion with heparitinase I and β-N-acetylhexosaminidase separately. The labeled products were digested completely by heparitinase I, which cleaves only an α1,4-glucosaminyl glucuronate linkage (37, 38), and the original radioactivity peak eluted near the void volume was shifted to the free [3H]GlcNAc position, as shown in Fig. 1. β-N-Acetylhexosaminidase did not release the radioactive monosaccharide at all. These findings indicate that GlcNAc had been transferred by EXTL1 protein through an α1,4-linkage to the nonreducing terminal GlcA of N-acetylheparosan oligosaccharides, representing growing HS chains. Hence, EXTL1 encodes novel GlcNAcT-II, which likely is involved in the synthesis of the repeating disaccharide region of HS/Hep.

Figure 1.

Characterization of EXTL1 GlcNAcT-II-reaction products. GlcNAcT-II-reaction products obtained with EXTL1 were digested with β-N-acetylhexosaminidase (□) or heparitinase I (■), and each digested or undigested sample (○) was applied to a column of Superdex peptide HR 10/30 (10 × 30 mm) and chromatographed as described in Materials and Methods. The separated fractions (0.4 ml each) were tested for radioactivity. An arrow indicates the elution position of free GlcNAc.

EXTL3 Protein Harbors Both GlcNAcT-I and GlcNAcT-II Activities, Which Likely Are Required for HS Synthesis.

The expression plasmid, which contains nucleotide sequences coding for the truncated EXTL3 fused with the insulin signal and protein A, was transfected into COS-1 cells, and the secreted EXTL3 fusion protein was examined for glycosyltransferase activities after purification with IgG-Sepharose. Recombinant EXTL3 transferred GlcNAc efficiently to N-acetylheparosan oligosaccharides with the nonreducing terminal GlcA (Table 1). To clarify whether it was a copolymerase, N-acetylheparosan oligosaccharides with the nonreducing terminal GlcNAc were used as acceptors for testing HS-GlcAT-II activity. However, it showed no HS-GlcAT-II activity and no GlcAT-I activity toward Galβ1–3Galβ1–4Xyl (Table 1).

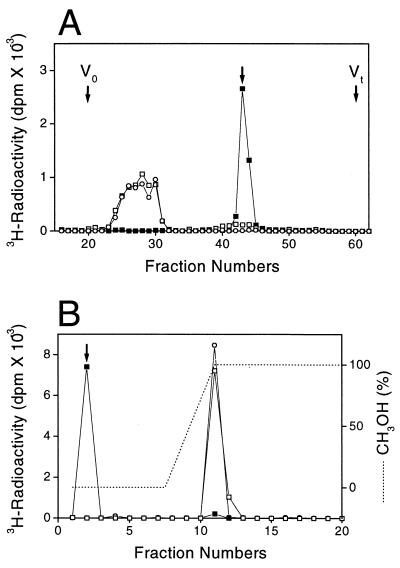

The products from GlcNAcT-II reaction were characterized by treatments with heparitinase I and β-N-acetylhexosaminidase. On heparitinase I digestion, the radioactivity was released as free [3H]GlcNAc from the reaction products eluted near the void volume, as demonstrated by gel-filtration chromatography (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the 3H-labeled products were entirely insensitive to the β-N-acetylhexosaminidase treatment. These findings indicate that EXTL3 transferred GlcNAc to N-acetylheparosan oligosaccharides via the α1,4-linkage.

Figure 2.

Characterization of GlcNAcT-I- and GlcNAcT-II-reaction products produced by EXTL3. (A) GlcNAcT-II-reaction products obtained with EXTL3 were digested with β-N-acetylhexosaminidase (□) or heparitinase I (■), and each digested or undigested sample (○) was applied to a column of Superdex peptide HR 10/30 (10 × 30 mm) and chromatographed as described in Materials and Methods. The separated fractions (0.4 ml each) were tested for radioactivity. An arrow indicates the elution position of free GlcNAc. (B) EXTL3 GlcNAcT-I-reaction products were subjected to digestion with β-N-acetylhexosaminidase (□) or heparitinase I (■), and each digested or undigested sample (○) was analyzed by HPLC on a Nova-Pak C18 column as described in Materials and Methods. The separated fractions (2 ml each) were measured for radioactivity. An arrow indicates the elution position of free GlcNAc.

Surprisingly, EXTL3, unlike EXTL1, exhibited marked GlcNAcT-I activity as detected by using GlcAβ1–3Galβ1O-C2H4NHCbz. However, the linkage-region tetrasaccharide-serine GlcAβ1–3Galβ1–3Galβ1–4Xylβ1-O-Ser with the native structure did not serve as an acceptor. This apparent discrepancy was taken to indicate that the enzyme required an appropriately hydrophobic peptide sequence in the vicinity of the linkage region, which can be substituted by an artificial aglycon such as C2H4NHCbz (see Discussion). Although EXTL3 resembles EXTL2 in that it exhibited GlcNAcT-I activity toward the above linkage-region analog, EXTL3, unlike EXTL2, showed no α-GalNAc transferase activity toward N-acetylchondrosine (26) as shown in Table 1, which clearly distinguishes EXTL3 from EXTL2. Chondroitin was not used as an acceptor when either UDP-[3H]GalNAc or UDP-[14C]GlcA was included as a donor (Table 1). The observed GlcNAcT-I activity toward the synthetic substrate was not detected when using the culture medium obtained from the control transfection, confirming that the enzyme activity was attributable to the EXTL3 protein.

The radioactivity of the GlcNAcT-I-reaction products, which had been retained on a C18 column, also was released by digestion with heparitinase I and eluted in the flow-through fraction as free [3H]GlcNAc, as demonstrated in Fig. 2B. β-N-Acetylhexosaminidase digestion released no radioactivity. These findings indicate that EXTL3 could transfer GlcNAc not only to N-acetylheparosan oligosaccharides but also to GlcAβ1–3Galβ1-O-C2H4NHCbz via the α1,4-linkage. Thus, it was suggested that GlcNAc residues were transferred to the nonreducing termini of the acceptors exclusively via the α1,4-linkage in both GlcNAcT-I and GlcNAcT-II reactions, which indicates that EXTL3 most likely is involved in initiation and elongation of the HS/Hep chain.

Discussion

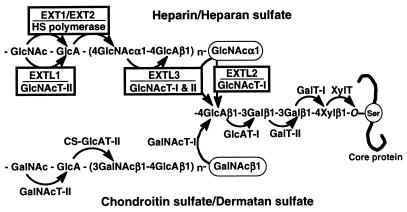

In this study, both EXTL1 and EXTL3, like the other EXT members, were demonstrated to be novel α1,4-GlcNAc transferases that likely are involved in the biosynthesis of HS and probably Hep. These findings are consistent with the observation that they have high sequence homology in the C-terminal regions with the other family members, EXT1, EXT2, and EXTL2, all of which harbor α1,4-GlcNAc transferase activities (8), and that EXTL1 and EXTL3, like the other family members, have the DXD motif common to most glycosyltransferases (39). It is unlikely that the observed enzyme activities of EXTL1 and EXTL3 were a result of endogenous EXT1 or EXT2, which may form a complex, as will be discussed below; HS-GlcAT-II activity, which might be expected for such complexes, was not detected for either EXTL1 or EXTL3 upon their individual overexpression. EXTL3 showed both GlcNAcT-I and GlcNAcT-II activities, which appear to be involved in the biosynthetic initiation and elongation, respectively, of HS/Hep precursor chains, whereas EXTL1 showed only GlcNAcT-II activity, which may be involved in HS chain elongation. Thus, the gene products of all five EXT family members now have been revealed to harbor glycosyltransferase activities, which can contribute to HS/Hep biosynthesis, as summarized in Table 2 and Fig. 3.

Table 2.

Summary of glycosyltransferase activities detected in EXT family members

| EXT1* | EXT2* | EXTL1 | EXTL2† | EXTL3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GlcNAcT-I‡ | − | − | − | + | + |

| GlcNAcT-II§ | + | + | + | − | + |

| HS-GlcAT-II¶ | + | + | − | − | − |

| α-GalNAcT‖ | − | − | − | + | − |

GlcAβ1-3Galβ1-O-C2H4NHCbz was used as the acceptor substrate.

N-acetylheparosan oligosaccharides with the nonreducing terminal GlcA were used as the acceptor substrate.

N-acetylheparosan oligosaccharides with the nonreducing terminal GlcNAc were used as the acceptor substrate.

N-acetylchondrosine was used as the acceptor substrate.

Figure 3.

GAG biosynthesis and the EXT proteins.

Interestingly, the acceptor specificities of these glycosyltransferase activities are overlapping among multiple members, but distinct from each other. EXT1 and EXT2 are copolymerases with both GlcNAcT-II and HS-GlcAT-II activities for chain elongation (13, 17) and form a heterooligomeric complex to exhibit full enzyme activities of biological relevance (17–19). Although they resemble each other in the acceptor specificity, they cannot compensate for the deficiency of the other and are not functionally redundant, as is evident from the finding that deficiency of either one results in HME syndrome (15, 16). EXTL2 exhibits GlcNAcT-I activity that transfers only the first α1,4-GlcNAc residue to determine and initiate HS/Hep chain synthesis on the common GAG–protein linkage region in the core proteins, although the enzyme activity can be demonstrated only by using a synthetic linkage-region analog, GlcAβ1–3Galβ1-O-naphthalenmethanol (26) or GlcAβ1–3Galβ1-O-C2H4NHCbz, as an acceptor (31), but not with the authentic tetrasaccharide-serine (26, 31). EXTL3 showed both GlcNAcT-I and GlcNAcT-II activities and, thus, is different from EXTL1, which has only the latter enzyme activity (Table 1), and from the GlcNAcT-I reported for Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (9). EXTL3 is also different from EXT1 and EXT2 in that it has no HS-GlcAT-II activity or polymerizing activity. It shares GlcNAcT-I activity with EXTL2, but is clearly distinct from the latter as well because EXTL3 possesses GlcNAcT-II activity in addition to GlcNAcT-I activity. It also should be noted that EXTL3 does not harbor α-GalNAc transferase activity, which EXTL2 possesses (26), although the physiological significance of this enzyme activity remains to be clarified.

EXT genes have been well conserved between humans, D. melanogaster (ttv) (40), and C. elegans (rib-1, rib-2) (41). Recent studies have shown that HS and CS are also present in these genetically tractable model animals (42, 43), and a total amount of HS drastically decreases in ttv-defective D. melanogaster (44), which indicates that EXT homologs contribute to HS biosynthesis and are indispensable in these animals also. Recently, we found that rib-2 harbors both GlcNAcT-I and GlcNAcT-II activities, and its acceptor specificity resembled that of EXTL3 (31). In view of the higher homology of rib-2 to EXTL3 (58%) than EXT2 (44%), rib-2 appears to be a C. elegans EXTL3 ortholog. Because rib-1 and rib-2 are the only genes identified as EXT homologs in C. elegans, mutations in the rib-2 gene would cause severe developmental defects as ttv does in D. melanogaster.

EXTL3, like EXTL2, transfers the first α1,4-GlcNAc residue to initiate HS/Hep chains on the common linkage region segregating HS and Hep synthesis from CS and DS synthesis. A possible explanation for the existence of these two distinct GlcNAcT-I molecular species for this key enzyme activity, which is critical for the sorting mechanisms, may be that they initiate HS and/or Hep chains on different core proteins by discriminating the amino acid sequences. This hypothesis is consistent with the notion of the importance of amino acid sequences, which was proposed previously by Esko et al. (45) based on the specificity of GlcNAcT-I in CHO cells. β-d-Xylosides with lipophilic aglycons containing two fused aromatic rings such as estradiol and naphthalene efficiently initiate HS biosynthesis, whereas CS chains are initiated predominantly on less lipophilic xylosides (46, 47). Acidic amino acids close to the HS attachment sites are essential for HS glycanation (48), and a nearby hydrophobic residue and repetitive Ser-Gly sequences work as enhancers for HS attachment (49). These observations altogether indicate the critical roles of amino acid sequences in the proximity of HS and Hep attachment sites of the core protein for HS/Hep chain initiation. Our observations that EXTL2 and EXTL3 transferred a GlcNAc residue to chemically synthesized disaccharides with a hydrophobic aglycon, but not to GlcAβ1–3Galβ1–3Galβ1–4Xylβ1-O-Ser, are consistent with this concept. In addition, the importance of distant regions from the GAG attachment sites also has been emphasized recently in the preferential addition of HS chains (50): the cysteine-rich globular domain of glypican-1 is as much indispensable as the GAG attachment region to direct HS synthesis. If either EXTL3 or EXTL2 becomes associated with either EXT1 or EXT2, HS and/or Hep chains possibly might be initiated and polymerized efficiently on the tetrasaccharide core. However, such a heterooligomeric complex formation has not been reported.

EXTL1 has only GlcNAcT-II activity and possibly is involved in the HS and/or Hep chain elongation. However, it has been reported that HS synthesis is abolished in a CHO cell mutant pgsD-677 (28), which now has been identified as an EXT1-deficient mutant (51). A loss-of-function mutation in the mouse of EXT1 results in embryonic lethality (6), and HS synthesis is also abolished in EXT1−/− ES cells and decreases to less than 50% in +/− cell lines. These findings appear to indicate that EXT1 is primarily responsible for HS formation, especially in CHO cells and in early mouse development, and the HS synthesis deficiency cannot be compensated by the other EXT members. Although the exact role in vivo of EXTL1 is unclear because of the lack of mutants, it may function at later developmental stages. Indeed, it recently has been demonstrated by whole-mount in situ hybridizations that EXT1, EXT2, and EXTL1 show nearly identical expression patterns at stages E10.5 and 11.5 during mouse embryogenesis, but some differences become apparent at E13.5, and EXTL1 exhibits an expression profile distinct from that of EXT1 and EXT2 at E14.5 (52). Although GlcNAcT-II enzyme activity is negligible in EXT1-deficient CHO mutants including pgsD677 (28, 51), it is unknown to our knowledge whether EXTL1 as well as EXTL3 is expressed in wild-type CHO cells. Unlike other EXT gene family members, which are expressed ubiquitously, human EXTL1 is being expressed in limited areas such as skeletal muscles, brain, and heart (20). The expression is strongly detected in the liver as well as in the above tissues in the mouse but not in human Northern blots (52). Thus, EXTL1 may play its roles in a tissue-specific and spatiotemporally regulated manner. It also should be noted that there is substantial evidence that a gene encoding a putative tumor suppressor lies in the chromosomal locus (1p36.1) of EXTL1, and consistent deletions of the region have been detected in various tumors (see references in ref. 20), which also possibly indicates indispensable physiological functions of EXTL1.

It remains to be clarified how the GlcNAcT-II activity of EXTL1 or the similar GlcNAcT-II activity of EXTL3 plays its respective role in chain polymerization of HS/Hep, where it requires HS-GlcAT-II as a partner. It is unknown which one of EXT1 or EXT2 cooperates with EXTL1 and/or EXTL3 for the synthesis of the repeating disaccharide-region or chain polymerization or whether an as yet unidentified HS-GlcAT-II with no homology exists in addition to EXT1 and EXT2. Human EXT1 and EXT2 form a stable complex that accumulates in the Golgi apparatus (17–19) to exhibit substantially higher glycosyltransferase activities than EXT1 or EXT2 alone (17, 18). It was once reported that neither EXTL3 nor EXTL2 interacts with EXT1 or EXT2 upon concomitant overexpression and the intracellular locations of the latter proteins do not change from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus in contrast to the reported translocation of EXT1 and EXT2 upon their complex formation (18). However, a possibility should be reexamined in light of the revealed catalytic activities of EXTL1 and EXTL3 whether they interact with EXT1 and/or EXT2. A possibility of multimeric complex formation also exists. In this context, it should be remembered that HS chain polymerizing enzyme activity has not been demonstrated in vitro for an EXT1/EXT2 heterooligomeric complex. Alternatively, the single GlcNAc transfer catalyzed by EXTL1 and EXTL3 possibly breaks up the elongation process and, in effect, serves as a chain-termination mechanism.

Although the three EXT-like gene products, all of which are likely to be involved in some way in HS/Hep synthesis, it remains to be established how they share the respective roles and cooperate in development, pathophysiology and tumorigenesis, and how their expressions are regulated at the transcriptional, translational and enzyme levels.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kazunori Tsuchida for preparation of the vector pEF-BOS/IP and Dr. Tomoya Ogawa (The Institute of Physical and Chemical Research, Japan) for the synthetic tetrasaccharide-serine and encouragement. This work was supported in part by grants from the Science Research Promotion Fund of the Japan Private School Promotion Foundation and the Uehara Memorial Foundation (to H.K.), a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas 10178102 (to K.S.) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan, Grant 13401 from the Swedish Medical Research Council, and by the Human Frontier Science Program. B.-T.K. is a recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Abbreviations

- GlcNAcT-I and GlcNAcT-II

α-GlcNAc transferases I and II

- Cbz

benzyloxycarbonyl

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- CS

chondroitin sulfate

- DS

dermatan sulfate

- EXT

hereditary multiple exostoses gene

- GAG

glycosaminoglycan

- GlcAT-I

glucuronyltransferase I

- Hep

heparin

- HS-GlcAT-II

heparan sulfate glucuronyltransferase II

- CS-GlcAT-II

chondroitin sulfate glucuronyltransferase II

- HME

hereditary multiple exostoses

- HS

heparan sulfate

References

- 1.Rodén L. In: The Biochemistry of Glycoproteins and Proteoglycans. Lennarz W J, editor. New York: Plenum; 1980. pp. 267–371. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernfield M, Götte M, Park P W, Reizes O, Fitzgerald M L, Lincecum J, Zako M. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:729–777. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salmivirta M, Lidholt K, Lindahl U. FASEB J. 1996;10:1270–1279. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.11.8836040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrimon N, Bernfield M. Nature (London) 2000;404:725–728. doi: 10.1038/35008000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lander A D, Selleck S B. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:227–232. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin X, Wei G, Shi Z, Dryer L, Esko J D, Wells D E, Matzuk M M. Dev Biol. 2000;224:299–311. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindahl U, Rodén L. In: Glycoprotein. Gottschalk A, editor. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1972. pp. 491–517. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugahara K, Kitagawa H. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:518–527. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fritz T A, Gabb M M, Wei G, Esko J D. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28809–28814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohrmann K, Niemann R, Buddecke E. Eur J Biochem. 1985;148:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb08862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadanaka S, Kitagawa H, Goto F, Tamura J, Neumann K W, Ogawa T, Sugahara K. Biochem J. 1999;340:353–357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCormick C, Leduc Y, Martindale D, Mattison K, Esford L E, Dyer A P, Tufaro F. Nat Genet. 1998;19:158–161. doi: 10.1038/514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lind T, Tufaro F, McCormick C, Lindahl U, Lidholt K. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26265–26268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solomon L. Am J Hum Genet. 1964;16:351–363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hecht J T, Hogue D, Strong L C, Hansen M F, Blanton S H, Wagner M. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:1125–1131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raskind W H, Conrad E U, Chansky H, Matsushita M. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:1132–1139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Senay C, Lind T, Muguruma K, Tone Y, Kitagawa H, Sugahara K, Lidholt K, Lindahl U, Kusche-Gullberg M. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:282–286. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCormick C, Duncan G, Goutsos K T, Tufaro F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:668–673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi S, Morimoto K, Shimizu T, Takahashi M, Kurosawa H, Shirasawa T. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268:860–867. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wise C A, Clines G A, Massa H, Trask B J, Lovett M. Genome Res. 1997;7:10–16. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wuyts W, Van Hul W, Hendrickx J, Speleman F, Wauters J, De Boulle K, Van Roy N, Van Agtmael T, Bossuyt P, Willems P J. Eur J Hum Genet. 1997;5:382–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Hul W, Wuyts W, Hendrickx J, Speleman F, Wauters J, De Boulle K, Van Roy N, Bossuyt P, Willems P J. Genomics. 1998;47:230–237. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saito T, Seki N, Yamauchi M, Tsuji S, Hayashi A, Kozuma S, Hori T. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;243:61–66. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wuyts W, Spieker N, Van Roy N, De Boulle K, De Paepe A, Willems P J, Van Hul W, Versteeg R, Speleman F. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1999;86:267–270. doi: 10.1159/000015317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arai T, Akiyama Y, Nagasaki H, Murase N, Okabe S, Ikeuchi T, Saito K, Iwai T, Yuasa Y. Intl J Oncol. 1999;15:915–919. doi: 10.3892/ijo.15.5.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitagawa H, Shimakawa H, Sugahara K. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13933–13937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamura J, Neumann K W, Ogawa T. Liebigs Ann. 1996. 1239–1257. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lidholt K, Weinke J L, Kiser C S, Lugemwa F N, Bame K J, Cheifetz S, Massagué J, Lindahl U, Esko J D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2267–2271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitagawa H, Paulson J C. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1394–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizushima S, Nagata S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5322. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.17.5322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitagawa H, Egusa N, Tamura J, Kusche-Gullberg M, Lindahl U, Sugahara K. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4834–4388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000835200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lind T, Lindahl U, Lidholt K. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20705–20708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitagawa H, Tone Y, Tamura J, Neumann K W, Ogawa T, Oka S, Kawasaki T, Sugahara K. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6615–6618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitagawa H, Kano Y, Shimakawa H, Goto F, Ogawa T, Okabe H, Sugahara K. Glycobiology. 1999;9:697–703. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.7.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitagawa H, Tsutsumi K, Ujikawa M, Goto F, Tamura J, Neumann K, Ogawa T, Sugahara K. Glycobiology. 1997;7:531–537. doi: 10.1093/glycob/7.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitagawa H, Ujikawa M, Tsutsumi K, Tamura J, Neumann K W, Ogawa T, Sugahara K. Glycobiology. 1997;7:905–911. doi: 10.1093/glycob/7.7.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamada S, Sakamoto K, Tsuda H, Yoshida K, Sugahara K, Khoo K H, Morris H R, Dell A. Glycobiology. 1994;4:69–78. doi: 10.1093/glycob/4.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugahara K, Tohno-oka R, Yamada S, Khoo K-H, Morris H R, Dell A. Glycobiology. 1994;4:535–544. doi: 10.1093/glycob/4.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breton C, Imberty A. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9:563–571. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bellaiche Y, The I, Perrimon N. Nature (London) 1998;394:85–88. doi: 10.1038/27932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clines G A, Ashley J A, Shah S, Lovett M. Genome Res. 1997;7:359–367. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.4.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamada Y, Van Die I, Van den Eijnden D H, Yokota A, Kitagawa H, Sugahara K. FEBS Lett. 1999;459:327–331. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toyoda H, Kinoshita-Toyoda A, Selleck S B. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2269–2275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toyoda H, Kinoshita-Toyoda A, Fox B, Selleck S B. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21856–21861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Esko J D, Zhang L. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:663–670. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fritz T A, Lugemwa F N, Sarkar A K, Esko J D. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:300–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fritz T A, Agrawal P K, Esko J D, Krishna N R. Glycobiology. 1997;7:587–595. doi: 10.1093/glycob/7.5.587-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang L, Esko J D. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19295–19299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang L, David G, Esko J D. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27127–27135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen R L, Lander A D. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7507–7517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008283200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wei G, Bai X, Gabb M M G, Bame K J, Koshy T I, Spear P G, Esko J D. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27733–27740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002990200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stickens D, Brown D, Evans G A. Dev Dyn. 2000;218:452–464. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(200007)218:3<452::AID-DVDY1000>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]