Abstract

The d-amino acid oxidase activator (DAOA) protein regulates the function of d-amino oxidase (DAO), an enzyme that catalyzes the oxidative deamination of d-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (D-DOPA) and d-serine. D-DOPA is converted to l-3,4-DOPA, a precursor of dopamine, whereas d-serine participates in glutamatergic transmission. We hypothesized that DAOA polymorphisms are associated with dopamine, serotonin and noradrenaline turnover in the human brain. Four single-nucleotide polymorphisms, previously reported to be associated with schizophrenia, were genotyped. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples were drawn by lumbar puncture, and the concentrations of the major dopamine metabolite homovanillic acid (HVA), the major serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) and the major noradrenaline metabolite 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG) were measured. Two of the investigated polymorphisms, rs3918342 and rs1421292, were significantly associated with CSF HVA concentrations. Rs3918342 was found to be nominally associated with CSF 5-HIAA concentrations. None of the polymorphisms were significantly associated with MHPG concentrations. Our results indicate that DAOA gene variation affects dopamine turnover in healthy individuals, suggesting that disturbed dopamine turnover is a possible mechanism behind the observed associations between genetic variation in DAOA and behavioral phenotypes in humans.

Keywords: d-amino acid oxidase activator gene (DAOA), Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), Homovanillic acid (HVA), 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG)

Introduction

The DAOA (d-amino acid oxidase activator gene) is located on chromosome 13q34 and spans 29 Kb. This region, spanning 5 Mb, was initially investigated by Chumakov and colleagues, and two overlapping genes, DAOA (or G72) and G30, transcribed in opposing directions, were identified [7]. DAOA gene variation was initially associated with schizophrenia [7], and during the past decade, this association has been replicated in many subsequent studies (http://www.szgene.org) [2]. DAOA has also been associated with schizophrenia-related characteristics such as frontal lobe volume change [16], susceptibility to methamphetamine psychosis [26], response to antipsychotic treatment [36] and progression of prodromal syndromes to first episode psychosis [31]. Furthermore, DAOA has been associated with other psychiatric disorders and phenotypes such as major depression [40], bipolar disorder [38] and bipolar disorder severity [8]. An animal study, using DAOA transgenic mice, showed behavioral phenotypes associated with psychosis, some of which could be reversed with haloperidol [34].

The DAOA protein contains 153 amino acids and has been detected in various parts of the central nervous system (CNS), including amygdala, nucleus caudatus and spinal cord [7]. DAOA has also been implicated in the regulation of mitochondrial function and dendritic branching [28]. The DAOA protein was initially reported to behave as an activator of porcine d-amino acid oxidase (DAO), whereas more recent studies showed that DAOA modulates human DAO function as a negative effector [7, 42].

DAO catalyzes the oxidative deamination of d-amino acids, such as d-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (D-DOPA) and d-serine to α-keto acids. Thus, DAO deaminates D-DOPA to its corresponding α-keto acid, which is then transaminated to L-DOPA [24, 52]. L-DOPA then enters the basic biosynthetic pathway to dopamine and homovanillic acid (HVA). Dopamine is converted to noradrenaline by dopamine-beta-hydroxylase, and noradrenaline enters its basic catabolic pathway and is degraded to 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG). Kinetic data show that the maximal velocity for the oxidative deamination of D-DOPA is much higher than for d-serine [24].

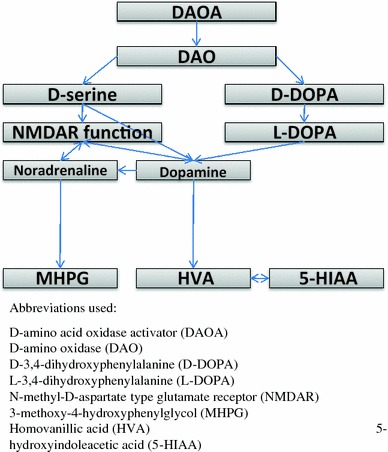

d-serine is an allosteric modulator of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA)-type glutamate receptors (NMDAR) [32], which have a modulatory site for d-serine. The occupation of this site by d-serine is required for glutamate to stimulate cation flow [19, 32]. Interaction between glutamate and noradrenaline [9] suggests that DAOA may be associated with noradrenaline via glutamatergic mechanisms (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Biochemical and functional connections between d-amino acid oxidase activator and cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolites

There is also evidence of a bidirectional interaction between NMDAR and the dopamine system. NMDAR activation leads to enhanced recruitment of the dopamine D1 receptor (DRD1) to the plasma membrane [37, 44]. Moreover, there is a direct protein–protein coupling between DRD1 and NMDAR [10, 29, 37]. It has been proposed that DRD1 and NMDAR early after their biosynthesis form heteromeric complexes, which are then transported to plasma membrane as preformed units [30]. NMDA antagonists lead to an increase in midbrain dopamine neuron firing rates [11], whereas striatal dopamine release has been reported increased or decreased in some studies [1, 39, 49]. A direct association between d-serine and dopamine release has also been shown, as high doses of d-serine attenuated amphetamine-induced dopamine release [46].

Taken together, there are biochemical connections between DAOA and the catecholamines dopamine and noradrenaline, via two identified pathways, first via DAO, d-serine and NMDAR, and secondly via DAO and D-DOPA (Fig. 1). The concentration of the major serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is strongly correlated with the major dopamine metabolite HVA [13]. This suggests that DAOA may also be associated with 5-HIAA (Fig. 1).

Given these biochemical and functional connections between the DAOA protein and the monoamine metabolites and the fact that studies in human twins and other primates indicate that monoamine metabolite concentrations are partly under genetic influence [17, 18, 35, 41], we can speculate that the well-established associations between DAOA and psychiatric phenotypes, described in the first paragraph, may be mediated by disturbed monoamine turnover rates.

In the present study, we aim to investigate whether DAOA polymorphisms are associated with dopamine, serotonin and noradrenaline turnover in the human brain. The concentrations of the major dopamine metabolite HVA, the major serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA and the major noradrenaline metabolite MHPG in CSF were used as indirect indexes of the monoamine turnover.

Methods

Subjects

Unrelated healthy Caucasians, 78 men and 54 women, participated in a longitudinal study. At the first interview, when CSF was sampled, their mean ages ± standard deviations (SD) were 27 ± 9 years, and all subjects were found to be healthy. Of the women, 22 used oral contraceptives at lumbar puncture, 29 did not, whereas data were missing for three female participants. Except for oral contraceptives, all subjects were drug-free at lumbar puncture. Eight to twenty years after the first investigation, all subjects were re-interviewed to re-assess the psychiatric morbidity as previously described [20, 23]. At this interview, whole blood was drawn from all participants. At the second investigation, 43 of the subjects were found to have experienced various DSM-III-R psychiatric lifetime diagnoses. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Karolinska University Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all the participating subjects.

CSF monoamine metabolite concentrations

CSF samples (12.5 ml) were obtained by lumbar puncture and analyzed as previously described [22, 45, 47]. Briefly, the samples were drawn between 8 and 9 a.m. with the subjects in the sitting or recumbent position, after at least 8 h of bed rest and absence of food intake or smoking. 5-HIAA, HVA and MHPG concentrations were measured by mass fragmentography with deuterium-labeled standards. Back-length was defined as the distance between the external occipital protuberance and the point of needle insertion.

DNA analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood [12]. Four DAOA SNPs (rs2391191 or M15, rs778294 or M19, rs3918342 or M23, rs1421292 or M24), previously reported to be associated with schizophrenia, were selected and genotyped at the SNP Technology Platform at Uppsala University and Uppsala University Hospital, Sweden (http://www.genotyping.se), using the Illumina BeadStation 500GX and the 1536-plex Illumina Golden Gate assay (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) as previously described [21].

Statistical analysis

Hardy–Weinberg (HW) equilibrium was tested using Fisher’s exact test as implemented in PEDSTATS [51]. Linkage disequilibrium (D′ and r 2) between SNP pairs was determined with Haploview 4.0 [3]. Allele association between DAOA SNPs and CSF monoamine metabolite concentrations was tested with a general linear model (Proc GLM, SAS/STAT® software, version 9.1.3, SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), where concentration was modeled as a linear function of the allele count (of each SNP separately) and one or more covariates (single-marker association).

Covariates were selected by preliminary analysis excluding genetic markers. That is, the effect of potentially important confounders (back-length, weight, gender, age at lumbar puncture and presence of a lifetime psychiatric diagnosis) on CSF monoamine metabolite concentrations was evaluated by forward stepwise selection, as previously described [20]. Confounders that explained a significant part of systematic variation in CSF concentrations (P < 0.1) were included as covariates in the genetic association analysis. Thus, back-length and presence of a lifetime psychiatric diagnosis were used as covariates in the analysis of 5-HIAA and HVA concentrations, whereas back-length and gender were included in the analyses of MHPG. We tested the normal distribution of residuals with the Anderson–Darling test, and residuals were approximately normally distributed after square root (5-HIAA, HVA) and logarithmic (MHPG) transformations. Correction for multiple testing was performed through random permutation of the four marker genotypes among individuals and recalculation of the P values for the 12 tests for each permuted data set (1,000 permuted data sets). The corrected P value was then calculated as the fraction of permutated data sets where the minimum P value from the 12 tests was equal to, or smaller than, the observed P value. Moreover, rs3918342, showing the strongest association with HVA, was selected for further analysis, applying a dominant model of segregation.

Results

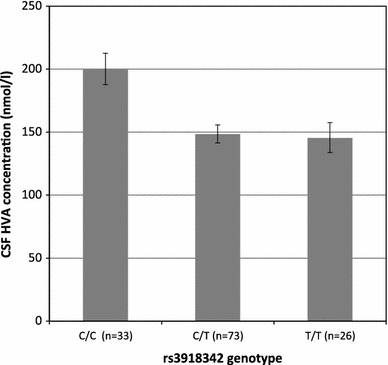

The mean (SD) concentrations of the three monoamine metabolites were: HVA, 170.2 (72.3) nmol/L; 5-HIAA, 91.7 (37.4) nmol/L; MHPG, 41.6 (8.2) nmol/L. Two of the investigated polymorphisms, rs3918342 (Fig. 2) and rs1421292, were found to be significantly associated with CSF HVA concentrations with corrected P values 0.013 and 0.043, respectively (Table 1). Rs3918342 was nominally associated with CSF 5-HIAA concentration, but this association was not statistically significant when accounting for the number of tests conducted. No polymorphisms were associated with MHPG concentrations.

Fig. 2.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) homovanillic acid (HVA) concentration in healthy subjects as a function of the number of rs3918342 T-alleles (corrected P value = 0.013). Least square means and standard errors are given

Table 1.

Allele association between d-amino acid oxidase activator (DAOA) single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), homovanillic acid (HVA) and 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG) concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

| SNP | Basea | MAFb | HWc | Genotype count | 5-HIAA | HVA | MHPG | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean concentration (nmol/l) | AddVal | P value | Mean concentration (nmol/l) | AddVal | P value | Mean concentration (nmol/l) | AddVal | P value | ||||||

| Rs2391191 | (G/A) | 0.42 | 0.28 | G/G | 48 | 85 | −0.02 | 0.83 | 170 | −0.14 | 0.20 | 42 | −0.14 | 0.24 |

| A/G | 58 | 86 | 155 | 41 | ||||||||||

| A/A | 26 | 83 | 152 | 40 | ||||||||||

| Rs778 294 | (C/T) | 0.28 | 0.39 | C/C | 70 | 88 | −0.11 | 0.40 | 161 | −0.03 | 0.84 | 42 | −0.20 | 0.13 |

| C/T | 49 | 82 | 158 | 40 | ||||||||||

| T/T | 12 | 83 | 159 | 40 | ||||||||||

| Rs391 8342 | (C/T) | 0.47 | 0.29 | C/C | 33 | 103 | −0.27 | 0.03 | 200 | −0.40 | 0.001d | 43 | −0.06 | 0.68 |

| C/T | 73 | 78 | 149 | 39 | ||||||||||

| T/T | 26 | 84 | 145 | 43 | ||||||||||

| Rs142 1292 | (T/A) | 0.44 | 0.38 | T/T | 39 | 96 | −0.21 | 0.09 | 190 | −0.35 | 0.004d | 44 | −0.17 | 0.20 |

| A/T | 71 | 80 | 149 | 39 | ||||||||||

| A/A | 22 | 84 | 147 | 43 | ||||||||||

For each monoamine metabolite, the mean CSF concentration per genotype is listed together with effect size (AddVal) due to the presence of one minor allele (given as standard deviations), and the corresponding P value from single-marker association analysis

aMajor/minor allele

bMinor allele frequency

cProbability of deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

dAssociations that remains significant after correction for multiple testing

The two SNPs associated with HVA concentrations, rs3918342 and rs1421292, are in strong linkage disequilibrium (LD; r 2 = 0.80) in Caucasians (HapMap, release 24). In the Scandinavian population, the two markers are in almost complete LD (r 2 = 0.99) [21], and thus, they captured the same association signal in this study. Consequently, rs1421292 explained no additional variation in HVA concentration (P = 0.95) on top of that explained by rs3918342.

Carriers of the rs3918342 T allele (both C/T and T/T) had 50 nmol/l lower HVA mean concentrations compared with C homozygotes; no difference in HVA mean concentrations was found between C/T and T/T (Fig. 2). This pattern is consistent with a dominant model of segregation (T allele dominant), and as expected, this model resulted in a substantial decrease in the uncorrected P value for the association between rs3918342 and HVA (from 0.0016 to 0.0001).

Discussion

In the present study, two DAOA polymorphisms, rs3918342 and rs1421292, were significantly associated with CSF HVA concentrations. Rs3918342 and rs1421292 are located 42 and 55 kbp from the 3′ end of DAOA, respectively, and are in strong linkage disequilibrium. Rs3918342 and rs1421292 have not been ascribed any functionality and were not found to be associated in strong LD (r 2 > 0.6) with any SNP within the DAOA borders. However, both were in strong LD with some intergenic SNPs within 500 kbp from rs3918342 (HapMap release 24). The associated intergenic SNPs lack currently known function or association with mental disorders.

During the past decades, a large number of CSF candidate markers, including the monoamine metabolite HVA, have been investigated with regard to their relevance to schizophrenia [48]. HVA concentrations have been reported to be significantly lower in drug-free schizophrenic patients compared with controls [6, 50]. Both quetiapine and olanzapine administrations have been associated with a significant increase in CSF HVA [33, 43], whereas haloperidol withdrawal resulted in a significant decrease in CSF HVA [5]. Thus, decreased HVA concentration appears to be related to schizophrenia.

There are several studies suggesting that a locus located near the 3′ end of DAOA is associated with phenotypes characteristic of schizophrenia or the progression of the disease. For example, both rs3918342 and rs1421292 have been associated with attention and memory impairments in schizophrenic individuals [14]. Rs3918342 has been associated with decreased hippocampal activation and increased prefrontal activation in subjects at high genetic risk of schizophrenia [15], as well as temporal lobe and amygdala gray matter reduction [53]. Furthermore, rs1421292 has been associated with brain activation in the right middle temporal gyrus and the right precuneus in healthy individuals [27]. Rs3918342 has been significantly associated with schizophrenia in independent studies [4, 7, 25]. However, meta-analysis of rs3918342 suggests that the association is restricted to populations of Caucasian origin and that the effect size is small (odds ratio = 1.03, non-significant; http://www.szgene.org) [2].

We found the TT genotype of rs3918342 to be strongly associated with decreased HVA concentrations, and we note that it is also this genotype that has been associated with attention and memory impairments in schizophrenic individuals [14], decreased hippocampal activation and increased prefrontal activation in subjects at high genetic risk of schizophrenia [15] as well as temporal lobe and amygdala gray matter reduction in bipolar patients [53]. Thus, it is possible that a disturbed dopamine turnover, reflected by decreased HVA levels, may be a mechanism behind one or several of the cognitive, neurological and brain morphological phenotypes previously associated with the rs3918342 TT genotype.

In conclusion, our results suggest that DAOA gene variation significantly affects dopamine turnover in CNS of healthy controls. Further research is needed in order to replicate our findings in healthy controls and, moreover, to find out whether the present associations can also be observed in schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgments

This study was financed by the Swedish Research Council (2006-2992, 2006-986, and 2008-2167), the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research between Stockholm County Council and the Karolinska Institutet, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and the HUBIN project. TW was financed by the Copenhagen Hospital Corporation Research Fund, the Danish National Psychiatric Research Foundation, the Danish Agency for Science, and Technology and Innovation (Centre for Pharmacogenetics). OAA was financed by the Research Council of Norway (147787 and 167153), the Eastern Norway Health Authority (Helse Øst RHF 123/2004), Ullevål University Hospital, and University of Oslo. We thank Alexandra Tylec, Agneta Gunnar, Monica Hellberg and Kjerstin Lind for technical assistance. We also thank Kristina Larsson, Tomas Axelsson and Ann-Christine Syvänen at the SNP Technology Platform in Uppsala for performing the genotyping. The SNP Technology Platform is supported by Uppsala University, Uppsala University Hospital and by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Conflict of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Adams BW, Bradberry CW, Moghaddam B. NMDA antagonist effects on striatal dopamine release: microdialysis studies in awake monkeys. Synapse. 2002;43:12–18. doi: 10.1002/syn.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen NC, Bagade S, McQueen MB, Ioannidis JPA, Kavvoura FK, Khoury MJ, Tanzi RE, Bertram L. Systematic meta-analyses and field synopsis of genetic association studies in schizophrenia: the SzGene database. Nat Genet. 2008;40:827–834. doi: 10.1038/ng.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bass NJ, Datta SR, McQuillin A, Puri V, Choudhury K, Thirumalai S, Lawrence J, Quested D, Pimm J, Curtis D, Gurling HM. Evidence for the association of the DAOA (G72) gene with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder but not for the association of the DAO gene with schizophrenia. Behav Brain Funct. 2009;5:28. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-5-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beuger M, van Kammen DP, Kelley ME, Yao J. Dopamine turnover in schizophrenia before and after haloperidol withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15:75–86. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00158-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjerkenstedt L, Edman G, Hagenfeldt L, Sedvall G, Wiesel F-A. Plasma amino acids in relation to cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolites in schizophrenic patients and healthy controls. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;147:276–282. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chumakov I, Blumenfeld M, Guerassimenko O, Cavarec L, Palicio M, Abderrahim H, Bougueleret L, Barry C, Tanaka H, La Rosa P, Puech A, Tahri N, Cohen-Akenine A, Delabrosse S, Lissarrague S, Picard FP, K M, Essioux L, Millasseau P, Grel P, Debailleul V, Simon AM, Caterina D, Dufaure I, Malekzadeh K, Belova M, Luan JJ, Bouillot M, Sambucy JL, Primas G, Saumier M, Boubkiri N, Martin-Saumier S, Nasroune M, Peixoto H, Delaye A, Pinchot V, Bastucci M, Guillou S, Chevillon M, Sainz-Fuertes R, Meguenni S, Aurich-Costa J, Cherif D, Gimalac A, Van Duijn C, Gauvreau D, Ouellette G, Fortier I, Raelson J, Sherbatich T, Riazanskaia N, Rogaev E, Raeymaekers P, Aerssens J, Konings F, Luyten W, Macciardi F, Sham PC, Straub RE, Weinberger DR, Cohen N, Cohen D (2002) Genetic and physiological data implicating the new human gene G72 and the gene for d-amino acid oxidase in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:13675–13680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Dalvie S, Horn N, Nossek C, van der Merwe L, Stein DJ, Ramesar R. Psychosis and relapse in bipolar disorder are related to GRM3, DAOA, and GRIN2B genotype. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg) 2010;13:297–301. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v13i4.61880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman S, Weidenfeld J. Involvement of endogeneous glutamate in the stimulatory effect of norepinephrine and serotonin on the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;79:43–53. doi: 10.1159/000076044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiorentini C, Gardoni F, Spano P, Di Luca M, Missale C. Regulation of dopamine D1 receptor trafficking and desensitization by oligomerization with glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20196–20202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.French ED. Phencyclidine and the midbrain dopamine system: electrophysiology and behavior. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1994;16:355–362. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(94)90023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geijer T, Neiman J, Rydberg U, Gyllander A, Jönsson E, Sedvall G, Valverius P, Terenius L. Dopamine D2 receptor gene polymorphisms in Scandinavian chronic alcoholics. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;244:26–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02279808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geracioti TD, Jr, Keck PE, Jr, Ekhator NN, West SA, Baker DG, Hill KK, Bruce AB, Wortman MD. Continuous covariability of dopamine and serotonin metabolites in human cerebrospinal fluid. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:228–233. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(97)90372-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg TE, Straub RE, Callicott JH, Hariri A, Mattay VS, Bigelow L, Coppola R, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. The G72/G30 gene complex and cognitive abnormalities in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2022–2032. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall J, Whalley HC, Moorhead TW, Baig BJ, McIntosh AM, Job DE, Owens DG, Lawrie SM, Johnstone EC. Genetic variation in the DAOA (G72) gene modulates hippocampal function in subjects at high risk of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:428–433. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartz SM, Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Librant A, Rudd D, Epping EA, Wassink TH. G72 influences longitudinal change in frontal lobe volume in schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B:640–647. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higley JD, Mehlman PT, Higley SB, Fernald B, Vickers J, Lindell SG, Taub DM, Suomi SJ, Linnoila M. Excessive mortality in young free-ranging male nonhuman primates with low cerebrospinal fluid 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid concentrations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:537–543. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830060083011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higley JD, Thompson WW, Champoux M, Goldman D, Hasert MF, Kraemer GW, Scanlan JM, Suomi SJ, Linnoila M. Paternal and maternal genetic and environmental contributions to cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolites in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:615–623. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820200025003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson JW, Ascher P. Glycine potentiates the NMDA response in cultured mouse brain neurons. Nature. 1987;325:529–531. doi: 10.1038/325529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonsson EG, Saetre P, Edman-Ahlbom B, Sillen A, Gunnar A, Andreou D, Agartz I, Sedvall G, Hall H, Terenius L. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene variation influences cerebrospinal fluid 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol concentrations in healthy volunteers. J Neural Transm. 2008;115:1695–1699. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonsson EG, Saetre P, Vares M, Andreou D, Larsson K, Timm S, Rasmussen HB, Djurovic S, Melle I, Andreassen OA, Agartz I, Werge T, Hall H, Terenius L. DTNBP1, NRG1, DAOA, DAO and GRM3 polymorphisms and schizophrenia: an association study. Neuropsychobiology. 2009;59:142–150. doi: 10.1159/000218076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jönsson E, Sedvall G, Brené S, Gustavsson JP, Geijer T, Terenius L, Crocq M-A, Lannfelt L, Tylec A, Sokoloff P, Schwartz JC, Wiesel F-A. Dopamine-related genes and their relationships to monoamine metabolites in CSF. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:1032–1043. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00581-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jönsson EG, Bah J, Melke J, Abou Jamra R, Schumacher J, Westberg L, Ivo R, Cichon S, Propping P, Nöthen MM, Eriksson E, Sedvall GC. Monoamine related functional gene variants and relationships to monoamine metabolite concentrations in CSF of healthy volunteers. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawazoe T, Park HK, Iwana S, Tsuge H, Fukui K. Human d-amino acid oxidase: an update and review. Chem Rec. 2007;7:305–315. doi: 10.1002/tcr.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korostishevsky M, Kaganovich M, Cholostoy A, Ashkenazi M, Ratner Y, Dahary D, Bernstein J, Bening-Abu-Shach U, Ben-Asher E, Lancet D, Ritsner M, Navon R. Is the G72/G30 locus associated with schizophrenia? Single nucleotide polymorphisms, haplotypes, and gene expression analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kotaka T, Ujike H, Okahisa Y, Takaki M, Nakata K, Kodama M, Inada T, Yamada M, Uchimura N, Iwata N, Sora I, Iyo M, Ozaki N, Kuroda S. G72 gene is associated with susceptibility to methamphetamine psychosis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33:1046–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krug A, Markov V, Krach S, Jansen A, Zerres K, Eggermann T, Stocker T, Shah NJ, Nothen MM, Georgi A, Strohmaier J, Rietschel M, Kircher T. Genetic variation in G72 correlates with brain activation in the right middle temporal gyrus in a verbal fluency task in healthy individuals. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011;32:118–126. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kvajo M, Dhilla A, Swor DE, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. Evidence implicating the candidate schizophrenia/bipolar disorder susceptibility gene G72 in mitochondrial function. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:685–696. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee FJ, Xue S, Pei L, Vukusic B, Chery N, Wang Y, Wang YT, Niznik HB, Yu XM, Liu F. Dual regulation of NMDA receptor functions by direct protein–protein interactions with the dopamine D1 receptor. Cell. 2002;111:219–230. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00962-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Missale C, Fiorentini C, Busi C, Collo G, Spano PF. The NMDA/D1 receptor complex as a new target in drug development. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:801–808. doi: 10.2174/156802606777057562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mossner R, Schuhmacher A, Wagner M, Quednow BB, Frommann I, Kuhn KU, Schwab SG, Rietschel M, Falkai P, Wolwer W, Ruhrmann S, Bechdolf A, Gaebel W, Klosterkotter J, Maier W. DAOA/G72 predicts the progression of prodromal syndromes to first episode psychosis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;260:209–215. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0044-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mothet JP, Parent AT, Wolosker H, Brady RO, Jr, Linden DJ, Ferris CD, Rogawski MA, Snyder SH. d-serine is an endogenous ligand for the glycine site of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4926–4931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikisch G, Baumann P, Wiedemann G, Kiessling B, Weisser H, Hertel A, Yoshitake T, Kehr J, Mathe AA. Quetiapine and norquetiapine in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenic patients treated with quetiapine: correlations to clinical outcome and HVA, 5-HIAA, and MHPG in CSF. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30:496–503. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181f2288e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otte DM, Bilkei-Gorzo A, Filiou MD, Turck CW, Yilmaz O, Holst MI, Schilling K, Abou-Jamra R, Schumacher J, Benzel I, Kunz WS, Beck H, Zimmer A. Behavioral changes in G72/G30 transgenic mice. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19:339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oxenstierna G, Edman G, Iselius L, Oreland L, Ross SB, Sedvall G. Concentrations of monoamine metabolites in the cerebrospinal fluid of twins and unrelated individuals—a genetic study. J Psychiatr Res. 1986;20:19–29. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(86)90020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pae CU, Chiesa A, Serretti A. Influence of DAOA gene variants on antipsychotic response after switch to aripiprazole. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:430–432. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pei L, Lee FJ, Moszczynska A, Vukusic B, Liu F. Regulation of dopamine D1 receptor function by physical interaction with the NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1149–1158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3922-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prata D, Breen G, Osborne S, Munro J, St Clair D, Collier D. Association of DAO and G72(DAOA)/G30 genes with bipolar affective disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:914–917. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rao TS, Kim HS, Lehmann J, Martin LL, Wood PL. Differential effects of phencyclidine (PCP) and ketamine on mesocortical and mesostriatal dopamine release in vivo. Life Sci. 1989;45:1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90163-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rietschel M, Beckmann L, Strohmaier J, Georgi A, Karpushova A, Schirmbeck F, Boesshenz KV, Schmal C, Burger C, Jamra RA, Schumacher J, Hofels S, Kumsta R, Entringer S, Krug A, Markov V, Maier W, Propping P, Wust S, Kircher T, Nothen MM, Cichon S, Schulze TG. G72 and its association with major depression and neuroticism in large population-based groups from Germany. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:753–762. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07060883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rogers J, Martin LJ, Comuzzie AG, Mann JJ, Manuck SB, Leland M, Kaplan JR. Genetics of monoamine metabolites in baboons: overlapping sets of genes influence levels of 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid, 3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenylglycol, and homovanillic acid. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:739–744. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sacchi S, Bernasconi M, Martineau M, Mothet JP, Ruzzene M, Pilone MS, Pollegioni L, Molla G. pLG72 modulates intracellular d-serine levels through its interaction with d-amino acid oxidase: effect on schizophrenia susceptibility. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:22244–22256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709153200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scheepers FE, Gispen-de Wied CC, Westenberg HG, Kahn RS. The effect of olanzapine treatment on monoamine metabolite concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenic patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:468–475. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scott L, Kruse MS, Forssberg H, Brismar H, Greengard P, Aperia A. Selective up-regulation of dopamine D1 receptors in dendritic spines by NMDA receptor activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1661–1664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032654599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sedvall GC, Wode-Helgodt B. Aberrant monoamine metabolite levels in CSF and family history of schizophrenia. Their relationships in schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37:1113–1116. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780230031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith SM, Uslaner JM, Yao L, Mullins CM, Surles NO, Huszar SL, McNaughton CH, Pascarella DM, Kandebo M, Hinchliffe RM, Sparey T, Brandon NJ, Jones B, Venkatraman S, Young MB, Sachs N, Jacobson MA, Hutson PH. The behavioral and neurochemical effects of a novel d-amino acid oxidase inhibitor compound 8 [4H-thieno [3,2-b]pyrrole-5-carboxylic acid] and d-serine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:921–930. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swahn C-G, Sandgärde B, Wiesel F-A, Sedvall G. Simultaneous determination of the three major monoamine metabolites in brain tissue and body fluids by a mass fragmentographic method. Psychopharmacology. 1976;48:147–152. doi: 10.1007/BF00423253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vasic N, Connemann BJ, Wolf RC, Tumani H, Brettschneider J (2011) Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates of schizophrenia: where do we stand? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. doi:10.1007/s00406-00011-00280-00409 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Wheeler D, Boutelle MG, Fillenz M. The role of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors in the regulation of physiologically released dopamine. Neuroscience. 1995;65:767–774. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)93905-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wieselgren I-M, Lindström LH. CSF levels of HVA and 5-HIAA in drug-free schizophrenic patients and healthy controls: a prospective study focused on their predictive value for outcome in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1998;81:101–110. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wigginton JE, Abecasis GR. PEDSTATS: descriptive statistics, graphics and quality assessment for gene mapping data. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3445–3447. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu M, Zhou XJ, Konno R, Wang YX. d-dopa is unidirectionally converted to l-dopa by d-amino acid oxidase, followed by dopa transaminase. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:1042–1046. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zuliani R, Moorhead TW, Job D, McKirdy J, Sussmann JE, Johnstone EC, Lawrie SM, Brambilla P, Hall J, McIntosh AM. Genetic variation in the G72 (DAOA) gene affects temporal lobe and amygdala structure in subjects affected by bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:621–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]