Abstract

Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) are allosteric inhibitors of the HIV type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase (RT). Yeast grown in the presence of many of these drugs exhibited dramatically increased association of the p66 and p51 subunits of the HIV-1 RT as reported by a yeast two-hybrid assay. The enhancement required drug binding by RT; introduction of a drug-resistance mutation into the p66 construct negated the enhancement effect. The drugs could also induce heterodimerization of dimerization defective mutants. Coimmunoprecipitation of RT subunits from yeast lysates confirmed the induction of heterodimer formation by the drugs. In vitro-binding studies indicate that NNRTIs can bind tightly to p66 but not p51 and then mediate subsequent heterodimerization. This study demonstrates an unexpected effect of NNRTIs on the assembly of RT subunits.

The HIV type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase (RT) catalyzes the conversion of genomic RNA into double-stranded proviral DNA after cell entry (1), by using the RNA- and DNA-dependent polymerase and ribonuclease H (RNase H) activities of the enzyme. The HIV-1 RT is an asymmetric dimer consisting of p66 and p51 polypeptides (2, 3). The p51 subunit contains the identical N-terminal sequences as p66 but lacks the C-terminal RNase H domain. The structure of the HIV-1 RT has been elucidated by x-ray crystallography in several forms including the unliganded enzyme (4), in complex with nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) (5, 6), and bound to template-primer with (7) or without dNTP substrate (8). The polymerase domain of the p66 subunit resembles a right hand and contains the fingers, palm, thumb, and connection subdomains, with the latter acting as a tether between the polymerase and RNase H regions (5, 8). Although p51 has the same polymerase domains as p66, the relative orientations of these individual domains differ markedly (5, 8). Structural analysis reveals three major contacts between p66 and p51, with most of the interaction surfaces being hydrophobic (9, 10).

NNRTIs are chemically diverse, largely hydrophobic compounds, which comprise over 30 different classes (11, 12). NNRTIs do not require intracellular metabolism for activity, are noncompetitive inhibitors of RT activity with respect to dNTP substrate and template/primer, and are relatively noncytotoxic (11). NNRTIs bind to a hydrophobic pocket close to but distinct from the polymerase active site in the p66 subunit (13, 14) and inhibit enzyme activity by mediating allosteric changes in the RT (15, 16). Initial clinical use of NNRTIs as monotherapy and selection of drug-resistant variants in cell culture results in the rapid emergence of highly drug-resistant variants due to single amino acid changes (17, 18) in the NNRTI-binding pocket that directly affect drug binding (13, 14). The NNRTIs currently approved for use in highly active antiretroviral therapy include nevirapine (19), delavirdine (BHAP; ref. 20), and efavirenz (EFV; ref. 21).

We have previously shown that HIV-1 RT heterodimerization can be effectively monitored in the yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system by using appropriately engineered constructs (22). We used this system to assess the effect of NNRTIs on the β-galactosidase (β-gal) readout in yeast. Several NNRTIs induced dramatic increases in β-gal activity, and this increase was due to enhanced association between the RT subunits as a result of a specific interaction of drug with the p66 subunit. These data document an unexpected effect of NNRTIs on HIV-1 RT dimerization and demonstrate that these drugs behave in a manner similar to chemical inducers of dimerization, compounds that bind to a target protein and promote an interaction with another protein (23).

Materials and Methods

Antiviral Drugs.

The drugs used in this study were: carboxanilides UC781, UC10, UC38, UC84 (24, 25), Uniroyal Chemical (Middlebury, CT); EFV (21), DuPont Merck; BHAP (26), Amersham Pharmacia and Upjohn; nevirapine (19), Roxanne Laboratories (Redding, CT); (S)-4-isopropoxycarbonyl-6-methoxy-3-(methylthiomethyl)-3,4-dihydroquinoxaline-2(1H)-thione (HBY 097) (27), Hoechst-Bayer (Frankfurt, Germany); and (−)-(S)-8-chloro-4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-5-methyl-6-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)imidazo[4,5,1-jk][1,4]benzodiazepin-2(1H)-thione monohydrochloride (8 Cl-TIBO) (28) and α-anilinophenylacetamide (α-APA) (29), Janssen. All drugs were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a concentration of 10 mg/ml for use in Y2H and in vitro assays.

Yeast and Bacterial Strains and Yeast Methods.

Yeast and bacterial strains were as described (22). Transformation of yeast, the qualitative β-gal colony lift assay, and the quantitative β-gal liquid assay were as described (22).

Construction of HIV-1 RT Fusions in Yeast Expression Vectors.

The construction of p66SH2–1, p51SH2–1, p66GADNOT, p51GADNOT, and p51ACTII, which express the wild-type (wt) p66 and p51 fusion proteins lexA87-66, lexA87-51, Gal4AD-66, Gal4AD-51, and Gal4AD-hemagglutinin (HA)-51, respectively, were as described (22). p66L234ASH2–1 (encoding lexA87-66L234A) was made by cloning the PCR amplification product from the RT region of p66AlaL234ALex202 (22) into the BamHI–SalI sites of pSH2–1. p51234ACTII (encoding Gal4AD-HA-51L234A) was constructed by subcloning the p51 BamHI–SalI fragment from p51234GADNOT (22) into pACTII. p66W401ASH2–1 (encoding lexA87-66W401A), p51W401AACTII (encoding Gal4AD-HA-51W401A), and p51W401AGADNOT (encoding Gal4AD-51W401A) were made by PCR amplification of the RT region from plasmid pALRT-78S(A402) (a gift from John McCoy, Genetics Institute, Cambridge, MA) and cloned into the BamHI-SalI sites of pSH2–1, pGADNOT or the BamHI–XhoI sites of pACTII. p66Y181CSH2–1 containing the Y181C mutation in p66 of the lexA87-66 fusion protein was prepared by site-directed mutagenesis using the Gene Editor Kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Construction of HIV-1 RT Fusions in Bacterial Expression Vectors.

The wt and p66 mutants (either L234A or W401A) were cloned into the SphI–BglII site of pQE-70 (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) (22). Glutathione S-transferase-tagged p51 (GST-p51) and mutants containing either the W401A or L234A substitutions were constructed by cloning the p51-encoding fragments into the BamHI–SalI site of pGEX5X-3 (Amersham Pharmacia) (22).

Y2H RT Heterodimerization Assays for Measuring Effect of NNRTIs on β-gal Activity.

CTY10–5d-transformed constructs expressing p66 bait and p51 prey fusions were grown overnight to stationary phase in synthetic complete medium without histidine and leucine and containing 2% glucose (SC-His-Leu). Media (2.5 ml) with or without drug were inoculated with 0.0125–0.25 OD600 of CTY10–5d. Yeast were grown with aeration at 30°C to OD600 = 0.5. The equivalent of 1 OD600 unit was pelleted for each treatment and subjected to a quantitative β-gal liquid assay.

Coimmunoprecipitation of p66 and p51 in Yeast Lysates.

Cultures (30 ml) containing no drug, EFV, or UC781 and 0.1 OD600/ml of CTY10–5d expressing p66 bait and p51 prey fusions were grown in SC-His-Leu to OD600 = 0.5 at 30°C. Cells were normalized to 12 OD600 and washed with 10 ml of 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and 1 mM EDTA. Preparation of protein extracts and immunoprecipitation were as described (30) except for the use of anti-HA.11 mAbs (clone 16B12; Covance, Princeton, NJ) and Protein G-PLUS agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Samples were resolved by SDS/PAGE. The lexA87-66 fusion protein was probed by using mAbs 7E5, which specifically detect p66 (31).

In Vitro Heterodimerization in the Presence of NNRTIs.

The heterodimerization of bacterially expressed wt p66-His and GST-p51 (or mutants) was assessed in bacterial lysates as described (22). To determine the capacity of EFV to bind to a particular RT subunit, 500-μl reactions in lysis buffer (without Nonidet P-40) (22), 5 μg of p66-His, 5 μg of GST-p51, or no recombinant protein (total protein concentration was 0.8 μg/ml in each reaction) were incubated overnight at 4°C with increasing concentrations of EFV. Lysates were washed four times with lysis buffer by using a centricon-YM-50 filter device (Millipore) to remove unbound drug. The corresponding RT subunit (5 μg) was applied to the washed lysates (in 500 μl) and incubated for 1.5 h at 4°C. Heterodimers were captured onto beads (22), resolved by SDS/PAGE, and detected by using RT antibodies (mAb 5B2) (31).

Results

Enhancement of β-Gal Activity by NNRTIs.

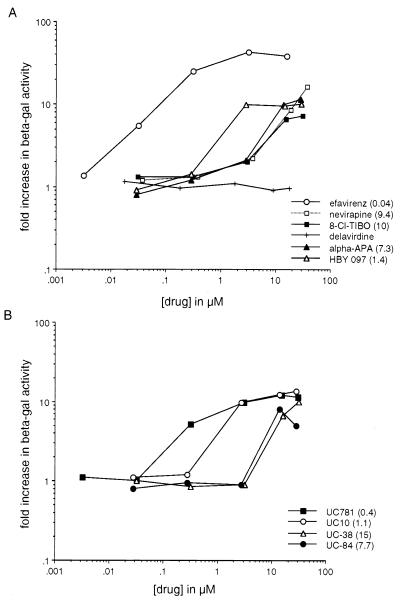

To test the effects of NNRTIs on the association of the RT polypeptides, we used a yeast genetic assay that measures RT heterodimerization (22). In this assay, yeast expressing the p66 subunit of the HIV-1 RT fused to the C terminus of lexA87 (lexA87-66) and the p51 subunit fused to the Gal4AD (Gal4AD-51) constitutively interact, resulting in the activation of the expression from an integrated Lac Z reporter gene. To test for the effects of the NNRTIs on this interaction, 10 drugs representing seven different NNRTI classes were added to the culture medium during growth of the yeast, and β-gal levels were determined. Of the 10 NNRTIs tested, nine demonstrated a dramatic concentration-dependent enhancement of β-gal activity compared to cells not treated with drug (Fig. 1 A and B). No significant toxicity, as determined by the growth rate, was observed for the drug concentrations tested compared to untreated controls (results not shown). EFV was the most potent of the compounds, mediating a 40-fold increase in β-gal activity at the highest drug concentration tested (Fig. 1A). The carboxanilide UC781 was the second most potent drug, followed by UC10 and a quinoxaline, HBY 097 (Fig. 1 A and B). The remainder of the NNRTIs were less potent but still displayed 8- to 10-fold increases in β-gal activity at the highest concentrations tested (Fig. 1 A and B). In contrast delaviridine was devoid of β-gal enhancing activity (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

A dose–response curve showing the enhancement by NNRTIs of β-gal activity in yeast cotransformed with lexA87-66 and Gal4AD-51. The fold increase in β-gal activity was calculated by dividing β-gal activity (in Miller units) for each drug concentration with the β-gal activity from cells grown in the absence of inhibitor. The data represents the average results from two independent experiments. The concentration of drug that mediates a 5-fold increase in β-gal activity is shown in parenthesis. (A) The β-gal enhancement activity of the NNRTIs, EFV, HBY 097, α-anilinophenylacetamide (α-APA), nevirapine, 8-Cl-TIBO, and BHAP. (B) The β-gal enhancement activity of the carboxanilide class of NNRTIs.

Enhancement of β-Gal Activity by NNRTIs Is Specific for RT Heterodimerization.

The specificity of the β-gal enhancement by NNRTIs was investigated. Yeast transformed with the empty vectors pSH2–1 and pGADNOT, which express lexA87 and Gal4AD, respectively, were treated with serial dilutions of the most potent β-gal enhancing drug, EFV. We observed no increase in β-gal activity even in the presence of 15 μM of drug (data not shown). The capacity of EFV to enhance β-gal activity of several unrelated protein–protein interaction pairs, including Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase with elongation factor release factor 1 (M.O., unpublished data), also was examined and no enhancement or inhibition of β-gal activity was observed.

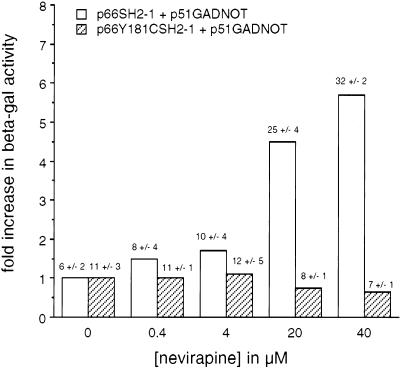

The Y181C mutation in the p66 subunit of the HIV-1 RT confers more than a 100-fold increase in resistance to nevirapine (17). This mutation directly affects drug binding (13, 14). To further establish the specificity of the β-gal enhancement by NNRTIs, Y181C was introduced into the plasmid encoding the lexA87-66 fusion protein. Yeast were cotransformed with various pairs of plasmids and grown in the presence of nevirapine. The presence of the Y181C change in the p66 bait totally negated the enhancement effect by nevirapine (Fig. 2). In contrast, a significant level of β-gal enhancement was still retained in the presence of EFV (results not shown), consistent with the low level of resistance conferred by Y181C to this drug. These data provide compelling evidence that the β-gal enhancement effect is due to a specific interaction of nevirapine with the p66 subunit of the HIV-1 RT.

Figure 2.

Effect of the Y181C mutation on enhancement of β-gal activity in yeast by nevirapine. Yeast expressing wt lexA87-66 and Gal4AD-51 or mutant lexA87-66Y181C and wt Gal4AD-51 were grown in the presence of nevirapine and assayed for β-gal activity. Results are expressed as fold increase in β-gal activity compared to untreated cells. Values on top of each bar indicates β-gal activity (in Miller units) +/− SD.

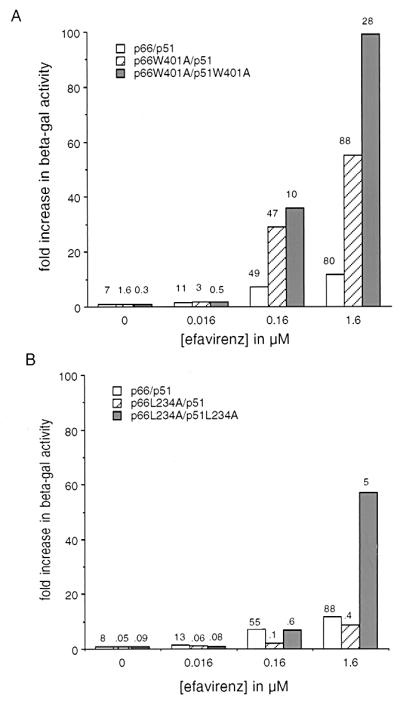

NNRTIs Can Enhance β-Gal Activity of Dimerization Defective Mutants.

Previous studies have shown that the L234A mutation in HIV-1 RT abrogates RT dimerization (22, 32). Other studies on the role of the tryptophan repeat motif (codons 398–414), present in the connection subdomains of both subunits, showed that the W401A mutation also diminishes RT dimerization in the Y2H assay (G.T., unpublished data). We investigated the effect of the NNRTIs, EFV, and UC781 on the β-gal enhancement effect on these dimerization defective RT mutants. Of interest, yeast treated with EFV and expressing the W401A change in one or both subunits showed a dramatic increase in β-gal activity compared to no drug (Fig. 3A). β-gal activity in yeast expressing the W401A mutation in both subunits was 100-fold greater in the presence of 1.6 μM EFV as compared to no drug (Fig. 3A). UC781 could also enhance the β-gal activity of yeast expressing W401A in both subunits (results not shown). It should be noted that, although the mutants displayed large increases in β-gal activity, the actual activity (displayed on the top of each bar) did not significantly exceed that observed with wt RT grown in the presence of EFV.

Figure 3.

Effect of EFV on β-gal activity in yeast expressing the dimerization defective mutants L234A and W401A. Yeast expressing wt p66 bait and p51 prey fusions, mutant p66 bait and wt p51 prey, and mutant p66 bait and mutant p51 prey fusions were assayed for β-gal activity. Results are expressed as the fold increase in β-gal activity compared to untreated controls. Values on top of each bar indicates β-gal activity in Miller units. Effect of EFV on yeast expressing bait and prey fusions with the W401A change (A) or L234A change (B).

The effect of EFV on the dimerization defective mutant L234A also was examined. EFV enhanced β-gal activity in yeast expressing RT bait and prey fusions with L234A in one or both subunits (Fig. 3B). The fold increase in β-gal, however, was less than with the W401A mutant (Fig. 3A). In contrast, UC781 conferred no enhancement on yeast expressing the L234A mutant (results not shown). As residue 234 is part of the NNRTI-binding site (13), and may make contact with UC781 (33), it is possible that UC781 does not bind to the L234A mutant. These data indicate that NNRTIs also are able to suppress the defects in assembly caused by two mutations when they can bind to those mutant enzymes.

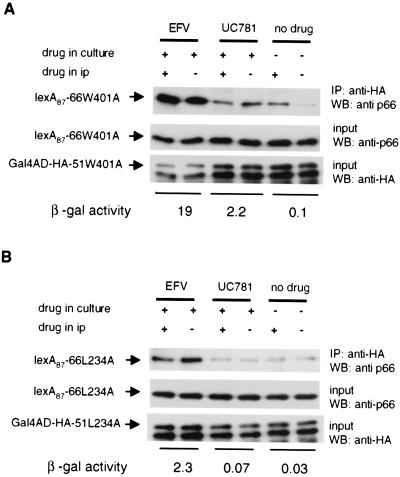

Coimmunoprecipitation of Heterodimer from Yeast Lysates Shows Enhancement of Dimer Formation in the Presence of Drug.

Experiments suggest that neither an increase in steady–state protein levels of bait-prey fusions in yeast nor an increase in nuclear localization of the drug-heterodimer complex explain the observed enhancement of β-gal activity by NNRTIs (results not shown). To directly test for induced heterodimerization by NNRTIs, we subjected lysates from yeast expressing dimerization defective mutants to coimmunoprecipitation. Yeast expressing both p66 bait and p51 prey fusions containing the W401A mutation (lexA87-66W401A and Gal4AD-HA-51W401A) or the L234A change (lexA87-66L234A and Gal4AD-HA-51L234A) were grown in the presence of EFV (1.6 μM), UC781 (16 μM), or no drug. HA antibodies were used to immunoprecipitate the p51 prey, and the presence of any bound p66 bait was then detected by using anti-p66-specific antibodies. For coimmunoprecipitation of the p66 bait fusions, samples were divided into two with one part processed without added NNRTI whereas the other was maintained in drug at the same concentration used during growth of yeast. Yeast grown in the absence of drug also was processed without drug or in the presence of 1.6 μM EFV. A clear increase in the amount of lexA87-66W401A and lexA87-66L234A associated with the p51 prey was observed for yeast grown in the presence of EFV compared to no drug (Fig. 4 A and B). Similar experiments with yeast grown in UC781 revealed heterodimer formation for yeast expressing the W401A mutant but not for the L234A mutant; these data corresponding to the levels of β-gal activity in the cells (Fig. 4 A and B).

Figure 4.

A coimmunoprecipitation assay detecting heterodimer formation in yeast propagated in the presence of NNRTIs. (A) Yeast expressing p66 bait and p51 prey fusions containing the W401A mutation were grown in the presence of EFV, UC781, or no drug. After growth, yeast were processed in the absence or presence of added drug. Heterodimers present in lysates were detected by immunoprecipation (IP) of Gal4AD-HA-51W401A with anti-HA antibodies followed by immunodetection of coimmunoprecipitated p66. The β-gal activity for each treatment was determined and expressed in Miller units. (B) Yeast expressing p66 bait and p51 prey fusions containing the L234A mutation.

We observed no significant difference in the amount of coimmunoprecipitated p66 bait in the absence or presence of drug, indicating that the heterodimer was stable under the conditions of the assay. Of interest, there was significantly more heterodimer present in yeast lysates obtained from cells grown in the absence of drug to which EFV was added during the coimmunoprecipitation procedure for the W401A mutant (Fig. 4A). These data suggest that some heterodimer formation could occur in vitro. Levels of mutant p66 bait and p51 prey fusions present in the original lysate from yeast grown in the absence and presence of drug were similar, indicating that the increase in coimmunoprecipitated p66 bait in the presence of drug was not due to increased levels of fusion proteins. It is clear from these experiments that NNRTIs tested do act by inducing heterodimerization of p66 and p51 in the Y2H assay and that the increased dimer formation correlates with the increase in β-gal activity.

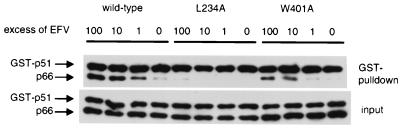

EFV Enhances the Association of wt and Mutant p66 and p51 in Lysates in Vitro.

To explore whether NNRTIs could enhance dimerization in vitro, bacterial lysates containing either p66-His or GST-p51 were prepared and combined in the presence of increasing concentrations of EFV. In the absence of inhibitor a small amount of dimer was present as indicated by detectable amounts of p66-His. A concentration-dependent increase in dimer formation was observed in the presence of increasing concentrations of EFV (Fig. 5). The enhancement effect of EFV on the L234A and W401A mutants also was assessed. Bacterial lysates separately expressing p66L234A-His and GST-p51L234A or p66W401A-His and GST-p51W401A were combined as above and incubated in the presence of increasing concentrations of EFV. A significant increase in dimer formation was observed in the presence of a 10-fold molar excess of EFV for the W401A mutant (Fig. 5). A 100-fold molar excess of EFV over RT was required to induce detectable enhancement of dimerization of the L234A mutant (Fig. 5). These data are consistent with the coimmunoprecipitation experiments and indicate that the enhancement of dimerization by EFV is due to its specific interaction with the HIV-1 RT and not dependent on the fusion proteins used in the Y2H assay nor on components present in the yeast cells in vivo.

Figure 5.

Western blot analysis of HIV-1 RT heterodimers formed in the presence of EFV in vitro. Bacteria expressing either wt p66-His and GST-p51, or dimerization defective mutants were induced, and lysates were prepared. Lysates were mixed and incubated overnight at 4°C with or without drug and dimers were captured by binding to glutathione Sepharose 4B beads. Heterodimer bound to beads were resolved by SDS/PAGE and proteins detected by probing with anti-RT mAbs.

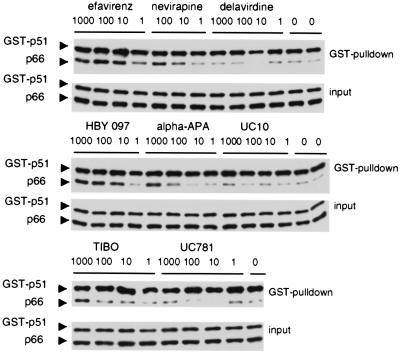

Other NNRTIs Enhance Heterodimerization of RT Subunits in Vitro.

We extended our in vitro study by testing the remaining NNRTIs for their capacity to enhance the dimerization of GST-p51 and p66-His in vitro. Consistent with our Y2H data, we observed that EFV was the most potent enhancer of dimerization. The relative in vitro potencies of the other NNRTIs correlated well with their β-gal enhancing effect in yeast (Fig. 1 and 6). In contrast, UC781 and UC10 were poor dimerization inducers in bacterial lysates compared to their β-gal-enhancing activities. The low dimerization enhancement activity of these drugs may be a function of both their poor solubility and the conditions of the in vitro assay (which was performed at 4°C). In contrast, the conditions of the yeast assay, which was carried out at 30°C with agitation, may have facilitated solubilization of UC781 and UC10. Of interest, BHAP also was inactive in vitro, indicating that the lack of effect in yeast was not a result of the inability of this drug to penetrate the cells.

Figure 6.

Western blot analysis of HIV-1 RT heterodimers formed in the presence of NNRTIs in vitro. Bacterially expressed proteins p66-His and GST-p51 were combined in the presence of 1- to 1,000-fold molar excess of drug and incubated overnight. Heterodimers were captured and detected as described in the legend of Fig. 5.

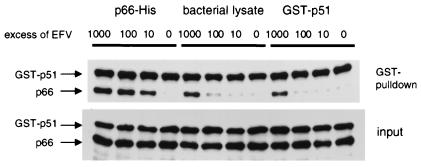

EFV Enhances Heterodimerization by Binding to p66-His but Not GST-p51.

To help elucidate the mechanism by which EFV enhances heterodimerization we assessed whether this drug could bind to either p66-His or GST-p51. Bacterial lysates expressing p66-His, GST-p51, or no recombinant protein were preincubated in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of EFV. Unbound drug was removed from the lysates by a series of washes, and the presence of any remaining drug was assayed by the addition of the cognate RT subunit. p66-His and GST-p51 was added to a washed mock bacterial lysate to assess the efficiency of EFV removal. When p66-His was preincubated with EFV we observed enhancement of dimerization with subsequently added GST-p51 at all drug concentrations (Fig. 7). This enhancement was similar to controls in which p66-His and GST-p51 were simultaneously combined with various drug concentrations (Fig. 6). A 100-fold reduction in the potency of heterodimerization compared to p66-His preincubated with EFV was observed in the washed mock bacterial lysate (Fig. 7). GST-p51 preincubated with drug, washed and then subjected to the functional heterodimerization assay displayed the same pattern of heterodimerization observed for the drug-treated mock bacterial lysate. These data indicate that EFV binds tightly to p66-His but not GST-p51 and that this binding then promotes heterodimerization with subsequent added GST-p51.

Figure 7.

Western blot analysis of heterodimer formation after pretreatment of one of the subunits with EFV. p66-His, GST-p51, and M15 bacterial lysate were preincubated in the absence or presence of 10- to 1,000-fold molar excess of EFV. Lysates were washed, and the presence of residual EFV was assayed by the addition of GST-p51, p66-His, or both subunits. Heterodimers were captured and detected as described in the legend of Fig. 5.

Discussion

In this study, we report a previously undescribed property of certain NNRTIs: their capacity to enhance heterodimerization of the p66 and p51 subunits of the HIV-1 RT. This effect was observed both in the Y2H system, detecting dimerization of p66 and p51 by using β-gal activity as a readout, and confirmed in coimmunoprecipitation experiments. The phenomenon also was observed in vitro by using bacterially expressed GST-p51 and p66-His, showing that it is not specific to yeast. NNRTIs also were able to induce the dimerization of the interaction defective mutants L234A and W401A. Furthermore, EFV can bind tightly to p66-His and then subsequently promote heterodimerization. Our data indicate that NNRTIs have properties similar to conventional chemical inducers of dimerization in their capacity to enhance the interaction between two proteins. As the interaction between p66 and p51 occurs naturally and the effect of the NNRTIs is to enhance this interaction, then these small molecules are best described as chemical enhancers of dimerization.

Correlation Between In Vitro and In Vivo Enhancement of Heterodimerization by NNRTIs.

The most potent β-gal enhancing NNRTIs in the Y2H RT dimerization assay were EFV, UC781, and HBY 097. These drugs are second generation NNRTIs that are also extremely potent inhibitors of HIV-1 replication in vitro (21, 25, 27). EFV and UC781 differ from the other NNRTIs in that they bind very tightly to the RT heterodimer and exhibit very slow dissociation rates (Koff) (34, 35). The tight binding properties of EFV and UC781 may in part have contributed to their potency as enhancers of heterodimerization in yeast. There was generally a very good correlation between the relative potency in inducing dimerization of the NNRTIs in vitro and in yeast, with the exception of UC781 and UC10.

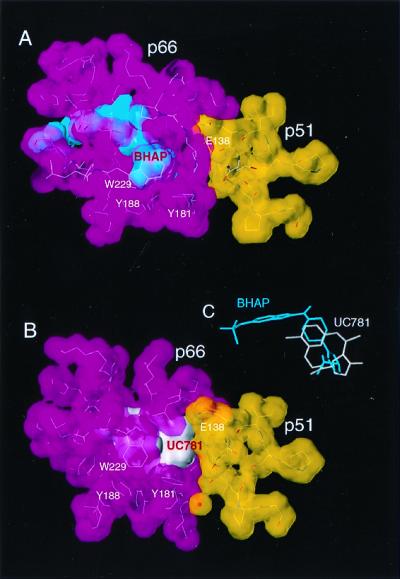

Relationship Among Drug-Induced Enhancement of Dimerization, Structural Changes in the HIV-1 RT, and RT Inhibitory Activity.

NNRTIs bind in a hydrophobic pocket at the base of the p66 thumb subdomain, which is proximal to (≈10 Å) but distinct from the polymerase active site. It is clear that the size of the NNRTI-binding pocket is small compared to the extensive dimer interface (Fig. 8). No strong correlation was found between the extent of the p66/p51 interface (36, 37) in the structures of the HIV-1 RT in complex with several NNRTIs and the drug concentration mediating a 5-fold enhancement of β-gal activity. Thus, the NNRTI effect on heterodimerization is not a simple function of the surface area buried at the interface, and NNRTIs may affect dimerization by other mechanisms in addition to modulating the extent of the contacts. The position of the drug in the pocket and the degree of NNRTI interaction with the p51 subunit were found to vary significantly among the different RT/NNRTI complexes (Fig. 9), and the changes in the vicinity of the bound NNRTIs also may play a role in heterodimer formation.

Figure 8.

Molecular surface representation of the p66 and p51 subunits of HIV-1 RT. Residues colored yellow (p66) or magenta (p51) are amino acids that are not accessible to solvent in the presence of the other subunit in the heterodimeric form. The NNRTI-binding pocket is shown in red. The sum of the surface areas colored in yellow and magenta is the total buried surface area at the interface of the two subunits.

Figure 9.

Binding of BHAP (A) and UC781 (B) at the interface of the p66 (magenta) and p51 (yellow) subunits of the HIV-1 RT. BHAP, a large inhibitor, is bound further away from the p66/p51 interface. The relative orientation of the inhibitors in the NNRTI-binding pocket is shown in C. Some residues that comprise the NNRTI-binding site have been omitted for clarity.

Binding of EFV to RT is accompanied by conformational changes in the binding pocket region, and these changes (including at Leu-234) (38), may also influence dimer formation. BHAP is the longest NNRTI inhibitor, and a portion of it protrudes outside the NNRTI-binding site causing the largest distortion of the p66 subunit of any of the NNRTIs studied to date (39). BHAP binds the furthest away from the p66/p51 interface (closest distance between BHAP and p51 is 5.1 Å compared to 3.8 Å for UC781) (Fig. 9). The unique characteristics of the interaction of BHAP with HIV-1 RT suggest that this NNRTI may bind to p66 in a distinctive way that does not favor the enhancement of dimerization.

We compared the relationship between the RT inhibitory activity of the NNRTIs in an exogenous RT assay (50% inhibitory concentration) and the concentration of drug that mediates a 5-fold increase in β-gal activity in the Y2H assay. EFV was the most potent in both assays whereas UC38 was the least active (results not shown). Examination of the data revealed a fair correlation (r = 0.6) between these two parameters, suggesting a relationship between the β-gal enhancement effect and RT inhibitory activity in vitro.

Potential Mechanisms for NNRTI Enhancement of Dimerization.

How might the NNRTIs enhance heterodimerization? One possible model involves NNRTI binding directly to the p66 monomer. Drug binding to monomeric p66 may stabilize a conformation that is more conducive to heterodimer formation, and a more potent NNRTI may effectively increase the concentration of p66 in a conformation that promotes dimerization. Alternatively, EFV may cause the p66 monomer to have a conformational flexibility that allows this subunit to more readily undergo structural changes necessary for dimerization. A second model would entail NNRTIs binding only to the heterodimer and as a consequence stabilizing the dimer. The binding could shift the equilibrium toward the dimer. Our data suggest that EFV binds tightly to p66. However, as bacterially expressed p66 comprises a population of monomers and homodimers, it is unclear whether GST-p51 is binding directly to monomeric p66 complexed with drug or is exchanging with one p66 subunit in the drug bound homodimer. Elucidation of the exact mechanism of NNRTI induced enhancement of dimerization will require further studies.

Our findings may have biological significance in terms of effects on virus replication. Drug binding to p66 could potentially modulate the interaction between Pr160GagPol precursors, which may affect regulation of HIV-1 protease-specific cleavage of this polyprotein. Further, the Y2H RT dimerization assay can potentially be used to screen for NNRTIs with the capacity to bind and mediate the appropriate conformational changes in the p66 subunit that results in enhanced binding to p51. It is possible that novel allosteric inhibitors of RT may be selected by using this assay.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jan Balzarini for supplying carboxanilides, John McCoy for pALRT-78S(A402), and Sergei Kuchin for pSK39 and pSK36. G.T. was supported in part by C. J. Martin Fellowship 977375 awarded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. M.O. is an Associate and S.P.G. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. S.S. and E.A. gratefully acknowledge support from National Institutes of Health Grant AI 27690 (MERIT award to E.A.).

Abbreviations

- HIV-1

HIV type 1

- NNRTI

nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- Y2H

yeast two-hybrid system

- HA

hemagglutinin

- GST-p51

glutathione S-transferase-tagged p51

- wt

wild type

- β-gal

β-galactosidase

- EFV

efavirenz

- BHAP

delavirdine

- HBY 097

(S)-4-isopropoxycarbonyl-6-methoxy-3-(methylthiomethyl)- 3,4-dihydroquinoxaline-2(1H)-thione

- 8-Cl-TIBO

(−)-(S)-8-chloro-4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-5-methyl-6-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)imidazo[4,5,1-jk][1,4]benzodiazepin-2(1H)-thione monohydrochloride

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

See commentary on page 6991.

References

- 1.Goff S P. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1990;3:817–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.di Marzo Veronese F, Copeland T D, DeVico A L, Rahman R, Oroszlan S, Gallo R C, Sarngadharan M G. Science. 1986;231:1289–1291. doi: 10.1126/science.2418504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Grice S F J. In: Reverse Transcriptase. Skalka A M, Goff S P, editors. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1993. pp. 163–191. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsiou Y, Ding J, Das K, Clark A D, Jr, Hughes S H, Arnold E. Structure (London) 1996;4:853–860. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kohlstaedt L A, Wang J, Friedman J M, Rice P A, Steitz T A. Science. 1992;256:1783–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.1377403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das K, Ding J, Hsiou Y, Clark A D, Jr, Moereels H, Koymans L, Andries K, Pauwels R, Janssen P A, Boyer P L, et al. J Mol Biol. 1996;264:1085–1100. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang H, Chopra R, Verdine G L, Harrison S C. Science. 1998;282:1669–1675. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobo-Molina A, Ding J, Nanni R G, Clark A D, Jr, Lu X, Tantillo C, Williams R L, Kamer G, Ferris A L, Clark P, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6320–6324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becerra S P, Kumar A, Lewis M S, Widen S G, Abbotts J, Karawya E M, Hughes S H, Shiloach J, Wilson S H. Biochemistry. 1991;30:11707–11719. doi: 10.1021/bi00114a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, Smerdon S J, Jager J, Kohlstaedt L A, Rice P A, Friedman J M, Steitz T A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7242–7246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Clercq E. Antiviral Res. 1998;38:153–179. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(98)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pedersen O S, Pedersen E B. Antiviral Chem Chemother. 1999;10:285–314. doi: 10.1177/095632029901000601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smerdon S J, Jager J, Wang J, Kohlstaedt L A, Chirino A J, Friedman J M, Rice P A, Steitz T A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3911–3915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tantillo C, Ding J, Jacobo-Molina A, Nanni R G, Boyer P L, Hughes S H, Pauwels R, Andries K, Janssen P A, Arnold E. J Mol Biol. 1994;243:369–387. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding J, Das K, Tantillo C, Zhang W, Clark A D, Jr, Jessen S, Lu X, Hsiou Y, Jacobo-Molina A, Andries K, et al. Structure (London) 1995;3:365–379. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esnouf R, Ren J, Ross C, Jones Y, Stammers D, Stuart D. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:303–308. doi: 10.1038/nsb0495-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richman D, Shih C K, Lowy I, Rose J, Prodanovich P, Goff S, Griffin J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11241–11245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richman D D, Havlir D, Corbeil J, Looney D, Ignacio C, Spector S A, Sullivan J, Cheeseman S, Barringer K, Pauletti D, et al. J Virol. 1994;68:1660–1666. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1660-1666.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merluzzi V J, Hargrave K D, Labadia M, Grozinger K, Skoog M, Wu J C, Shih C K, Eckner K, Hattox S, Adams J, et al. Science. 1990;250:1411–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.1701568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romero D L, Busso M, Tan C K, Reusser F, Palmer J R, Poppe S M, Aristoff P A, Downey K M, So A G, Resnick L, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8806–8810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young S D, Britcher S F, Tran L O, Payne L S, Lumma W C, Lyle T A, Huff J R, Anderson P S, Olsen D B, Carroll S S, et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2602–2605. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tachedjian G, Aronson H E, Goff S P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6334–6339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crabtree G R, Schreiber S L. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:418–422. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)20027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balzarini J, Brouwer W G, Felauer E E, De Clercq E, Karlsson A. Antiviral Res. 1995;27:219–236. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(95)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balzarini J, Brouwer W G, Dao D C, Osika E M, De Clercq E. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1454–1466. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.6.1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dueweke T J, Poppe S M, Romero D L, Swaney S M, So A G, Downey K M, Althaus I W, Reusser F, Busso M, Resnick L, et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1127–1131. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.5.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleim J P, Bender R, Kirsch R, Meichsner C, Paessens A, Rosner M, Rubsamen-Waigmann H, Kaiser R, Wichers M, Schneweis K E, et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2253–2257. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho W, Kukla M J, Breslin H J, Ludovici D W, Grous P P, Diamond C J, Miranda M, Rodgers J D, Ho C Y, De Clercq E, et al. J Med Chem. 1995;38:794–802. doi: 10.1021/jm00005a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pauwels R, Andries K, Debyser Z, Van Daele P, Schols D, Stoffels P, De Vreese K, Woestenborghs R, Vandamme A M, Janssen C G, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1711–1715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuchin S, Treich I, Carlson M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7916–7920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140109897. . (First Published June 27, 2000; 10.1073/pnas.140109897) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szilvay A M, Nornes S, Haugan I R, Olsen L, Prasad V R, Endresen C, Goff S P, Helland D E. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:647–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghosh M, Jacques P S, Rodgers D W, Ottman M, Darlix J L, Le Grice S F. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8553–8562. doi: 10.1021/bi952773j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esnouf R M, Stuart D I, De Clercq E, Schwartz E, Balzarini J. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234:458–464. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barnard J, Borkow G, Parniak M A. Biochemistry. 1997;36:7786–7792. doi: 10.1021/bi970140u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maga G, Ubiali D, Salvetti R, Pregnolato M, Spadari S. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1186–1194. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.5.1186-1194.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arnold E, Rossmann M G. J Mol Biol. 1990;211:763–801. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee B, Richards F M. J Mol Biol. 1971;55:379–400. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren J, Milton J, Weaver K L, Short S A, Stuart D I, Stammers D K. Struct Fold Des. 2000;8:1089–1094. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00513-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esnouf R M, Ren J, Hopkins A L, Ross C K, Jones E Y, Stammers D K, Stuart D I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3984–3989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]