Abstract

We previously showed that targeted expression of non-receptor tyrosine kinase Etk/BMX in mouse prostate induces prostate intraepithelial neoplasia, implying a possible causal role of Etk in prostate cancer development and progression. Here, we report that Etk is upregulated in both human and mouse prostates in response to androgen ablation. Etk expression appears to be differentially regulated by androgen and IL-6, which is possibly mediated by the androgen receptor (AR) in prostate cancer cells. Our immunohistochemical analysis of tissue microarrays containing 112 human prostate tumor samples revealed that Etk expression is elevated in hormone refractory prostate cancer and positively correlated with tyrosine phosphorylation of AR (Pearson correlation coefficient ρ=0.71, p<0.0001). AR tyrosine phosphorylation is increased in Etk overexpressing cells, suggesting that Etk may be another tyrosine kinase, in addition to Src and Ack-1, which can phosphorylate AR. We also demonstrated that Etk can directly interact with AR via its SH2 domain and such interaction may prevent the association of AR with Mdm2, leading to stabilization of AR under androgen-depleted conditions. Overexpression of Etk in androgen-sensitive LNCaP cells promotes tumor growth while knocking-down Etk expression in hormone-insensitive prostate cancer cells by a specific shRNA inhibits tumor growth under androgen-depleted conditions. Taken together, our data suggest that Etk may be a component of the adaptive compensatory mechanism activated by androgen ablation in prostate and may play a role in hormone resistance, at least in part, through direct modulation of AR signaling pathway.

Keywords: tyrosine kinase, prostate cancer, signal transduction, mouse model

INTRODUCTION

Hormonal therapy has been the treatment of choice for patients with advanced metastatic prostate cancer since Charles Huggins and his colleagues first demonstrated the effectiveness of androgen ablation therapy in 1941. However, majority of patients will inevitably develop recurrent hormone-resistant tumors, rendering the conventional therapy ineffective. Therefore, understanding the molecular basis underlying progression to a castration-resistant state is the first step towards developing therapies for this lethal form of prostate cancer (1).

Progression to castration-resistance is a multi-factorial process by which prostate cancer cells acquire the ability to survive and proliferate under low level of androgenic stimuli. The androgen receptor (AR), is primarily responsible for mediating the physiological effects of androgens by binding to specific DNA sequences, known as androgen response elements (AREs), which regulate transcription of androgen-responsive genes (2). Studies have shown that AR continues to be expressed and AR signaling remains intact in castration-resistant tumors (3). Potential mechanisms by which AR may be reactivated in the androgen-deprived environment include mutations and amplification of the AR gene, increased expression of steroid metabolism enzymes, steroid hormone receptor coactivators, and elevated levels of growth factors and cytokines (4). Increased AR expression was shown to be associated with the development of anti-androgen therapy resistance (5). Recently, we found that phosphorylation of AR Y534 induced by Src kinase may contribute to androgen-independent activation of AR or sensitize AR to low levels of hormone (6). Our immunohistochemical survey showed a moderate correlation of AR Y534 phosphorylation with Src kinase activity in human prostate tumor tissues, suggesting that Src is one of the tyrosine kinases that phosphorylate AR. Likely, additional kinases may also be involved in regulation of AR activity. This possibility was supported by an independent study on the Ack-1 kinase which has been shown to induce AR tyrosine phosphorylation (7). A recent report showed that phosphorylation of Y534 leads to stabilization of AR induced by a neuroendocrine-derived parathyroid hormone–related protein (8).

Epithelial and endothelial tyrosine kinase (Etk, also known as BMX, is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase and a downstream effector of Src and PI3-kinase (9, 10). Etk/BMX contains an N-terminal Pleckstrin Homology (PH) domain, Src Homology 3 (SH3) domain, Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain and C-terminal tyrosine kinase domain. Etk has been implicated in various biological processes including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and cell migration. Etk/BMX expression elevated in several aggressive metastatic carcinoma cell lines suggests that Etk/BMX may be involved in the development and progression of prostate cancer (11). The interaction between Etk and FAK is involved in integrin signaling and may play a role in tumor metastasis of prostate cancer cells (11, 12). Etk/BMX is upregulated during stress (e.g. radiation, wound healing) in endothelial cells and skin keratinocytes (13, 14), and mediates regulation of expression of stress-induced adaptive genes such as VEGF, PAI-1, and iNOS via multiple signaling cascades in different cell systems (15). Etk is activated by IL6 in prostate cancer cells through the PI3-kinase pathway and has been implicated in neuroendocrine differentiation (9). The synergism between Etk and Pim-1 appeared to be involved in IL6-induced ligand-independent activation of AR in prostate cancer cells (16). We also demonstrated that Etk directly interacts with tumor suppressor p53 and such interaction results in a bidirectional inhibition of the functions of both proteins (17). Furthermore, Etk is required for growth of prostate cancer cells induced by neuropeptides such as bombesin and neurotensin (18). However, the functional significance of Etk overexpression in castration-resistant prostate cancer remains unknown.

In this report, we demonstrate that Etk expression is elevated in response to androgen ablation in both human and mouse prostates. Our study suggests that Etk may be a component of the adaptive compensatory mechanism activated by androgen ablation in the prostate and may play a role in the development of hormone refractory prostate cancer, at least in part, through directly modulating AR function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue microarray, immunohistochemical analysis, and statistical analysis

Two intermediate-density prostate tissue arrays were prepared by the NYU Cooperative Prostate Cancer Tissue Resource and consisted of a total 112 cases (four cores per case) including 18 hormone-resistant (HR) and 18 hormone-naïve (HN) transurethral resection (TURP) specimens of prostate from patients with clinically advanced prostate cancer, 76 cases of HN prostate cancer tissue (Gleason sum 6–10) from the radical prostatectomy specimens of patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. The determination of HN and HR was as follows: (i) patients who had earlier undergone surgical orchiectomy or medical hormone-suppressive therapy at least 6 months prior to the procedure were considered as HR; (ii) patients who did not receive hormonal therapy prior to the TURP were considered as HN. Tissue specimens were from the archival paraffin block inventory of the NYU Cooperative Prostate Cancer Tissue Resource. All cases upon collection into the resource (under an IRB-approved protocol) had repeat pathology characterization of tissues and review of medical records. The Vectastain Elite ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories) was used for immunohistochemical staining according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. Finally, sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. Immunohistochemical staining was assessed independently by two pathologists (X.K. and J.M.), and a consensus of grading was reached. Immunostaining was graded using a two-score system based on intensity score (IS) and proportion score (PS) as described previously (6). The immunoreactive score for each case was quantified by the average of four cores. The statistical analyses were carried out by using the SAS version 9.0 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Animal dissection, histological analysis, immunoprecipitation and Western blot

Prostates were dissected under a dissecting microscope as described previously (19). Immunohistochemistry analysis was carried out with the following antibodies diluted in PBS: anti-Etk, anti-AR and anti-pARY534 (6). Negative controls were included in each assay. Prostate tissues were extracted by using T-PER protein extraction reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Antibodies were added to lysates and incubated for 1–3 h at 4°C. Immunoblotting was performed as described previously (12). Anti-Etk was used at 1:20,000, whereas anti-Erk1/2, anti-actin (C2) and anti-AR (N-20) (Santa Cruz), were used at 1:2,000. Anti-phospho SrcY416 (anti-pSrc) (Cell Signalingand anti-FLAG antibody M2 (Sigma) were used at 1: 4,000. The phospho-specific antibody for ARY534 (anti-pARY534) described previously (6) was used at 1: 2,000.

Quantitative real-time RT- PCR

Quantitative real time RT-PCR was performed as described previously (6), The primer sequences used for PSA were TCTGCGGCGGTGTTCTG and GCCGACCCAGCAAGATCA; AR, CCTGGCTTCCGCAACTTACAC and GGACTTGTGCATGCGGTACTCA; Etk, CTCGGAACTGTT TGGTGGAC and TGGAGCTGACCACTTGACTG; 18S, TTGACGGAAGGGCACCACCAG and GCACCACCACCCACGGAATCG; Actin, GCTATCCAGGCTGTGCTATC and TGTCACGCACGA TTTCC. The relative abundance of each target transcript was quantified by using the comparative ΔΔCt with Actin as an internal control (6).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

LNCaP cells were cultured in phenol-red free RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% charcoal-stripped serum for 3 days and then serum-starved for 16 h, followed by the treatment with vehicle control (Ethanol), 10 nM DHT, or 20ng/ml of IL-6 for 1 h. Chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed by using anti-AR or IgG as described previously (6, 20).

The PCR primers were as following: ARE-P : 5′-atgccagtttcaggagtggtaaga-3′ and 5′-tctggctaaagaatatggagtcatc-3′ ; ARE1: 5′-aggttctgtgaagccagtatttgtc-3′ and 5′-cgcttatcttcgtgctaaataactg-3′; ARE2: 5′-ataaccctgtctcccttggtatc-3 ′ and 5 ′-ataggaatctcctgctgaaaggc-3′; ARE3: 5′-tagcgagtc taaggtgagtaaagc-3′ and 5′-aagtagcaatgttgagcagtaggc-3′; ARE4: 5′-tcctcttctatccacttatcacatg-3′ and 5′-agtcttttcccaatgtcacctgg-3′

Cell culture and in vivo tumor growth in the xenograft models

LNCaP and COS-1 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Hormone refractory prostate cancer cell lines C-81 and CWR-R1 were kindly provided by Drs. Ming-Fong Lin (21), Christopher Gregory and Elizabeth Wilson (22), respectively. LNCaP and C-81 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS. COS-1 cells were grown in DMEM medium with 10% FBS. LAPC-4 cells (kindly provided by Dr. Charles Swayers) were maintained in IMEM supplemented with 15% FBS. CWR-R1 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 with 10% heat-inactive FBS. Transfections were carried out using FuGENE 6 (Roche) or LipofectAMINE 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instruction. LNCaP cells overexpressing T7-Etk was described previously (17). Lentivirus infections were carried out as described previously (17). Tumor growth in the SCID/ nude mice was carried out by subcutaneously inoculation of 106 prostate cancer cells mixed with Matrigel as described previously (6). All procedures involving animals were approved by IACUC of the University of Maryland.

RESULTS

Etk expression is increased in prostatic epithelium in response to androgen ablation

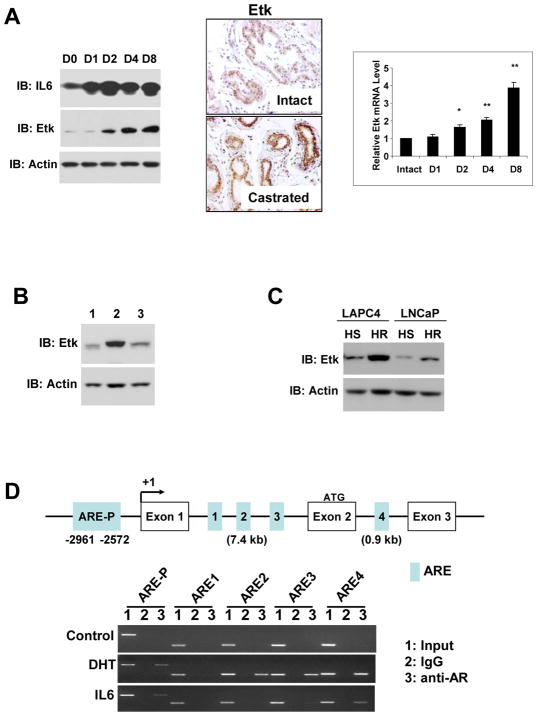

In an effort to examine the changes in mouse prostate in response to castration, we observed that Etk expression level was dramatically increased along with IL-6, which is known to be upregulated after castration (Fig 1A, left). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed an increase of Etk staining in both epithelial and stromal compartments in prostates of castrated mice. We also performed real-time RT-PCR analysis and detected a significant and progressive increase of Etk mRNA in the castrated mouse prostate (Fig 1A, right). Increased Etk expression in prostate appeared to be reversible when the castrated animals were treated with androgen replacement (Fig 1B). Etk expression was also increased in xenograft tumors derived from both LNCaP and LAPC4 cells after castration (Fig 1C). Furthermore, DHT treatment reduced the level of Etk mRNA in LNCaP cells in a concentration-dependent manner while an androgen antagonist bicalutamide had an opposing effect (Supplemental Fig 1). These data suggest that Etk expression is negatively regulated by androgens. Interestingly, multiple putative ARE sites were found in the promoter region and introns of human ETK/BMX gene (Fig 1C). Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays revealed that both DHT and IL-6 could recruit AR to the ARE sites located in the promoter region and the ARE4 site in the Intron 2, while only DHT was able to induce AR binding to the ARE2 and ARE3 sites located in Intron 1. This suggests a differential recruitment of AR to these ARE sites in ETK locus in response to DHT or IL-6 (Fig 1C). We also observed varied effects on occupancy of RNA Polymerase II and co-activator SRC1 in this region in cells treated with DHT or IL-6 (Supplemental Fig 2). This may provide mechanistic insight into differential regulation of Etk expression by androgen and IL-6.

Figure 1. Etk expression is increased in prostate cells after castration.

A, The 16-week-old FVB mice were castrated and sacrificed on Day 1 (D1), Day 2 (D2), Day 4 (D4) and Day8 (D8) post-castration, Etk expression was analyzed by Western Blot (Left) and Immunohistochemical (Center) analysis using anti-Etk antibody. IL6 was used as positive control for castration. Actin was used as a loading control. The relative Etk mRNA level in prostates from intact or castrated mice was determined by Real-time PCR analysis (Right). B, At Day 8 post-castration, mice were supplemented with 50mg/kg DHT per day for 5 days. The total prostate tissue lysates were subjected to Western Blot analysis with anti-Etk antibody. Lane 1, intact prostates; Lane 2, age-matched mice at Day 8 post-castration; Lane 3, the castrated mice supplemented with 50mg/kg DHT per day for 5 days. Actin was used as a loading control. C, Hormone sensitive (HS) and hormone refractory (HR) LAPC4 and LNCaP xenograft tumors were derived as described in Methods. Total protein lysates extracted from these tumors were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-Etk antibody. Actin served as a loading control. D, Binding of AR to the putative ARE sites (ARE-P, 1, 2, 3, 4) of human ETK gene in LNCaP cells in response to DHT and IL6 was analyzed by ChIP assays as described in Methods. PCR products were resolved on agarose gels.

Etk expression is elevated in hormone resistant prostate tumors and correlates with AR Y534 phosphorylation

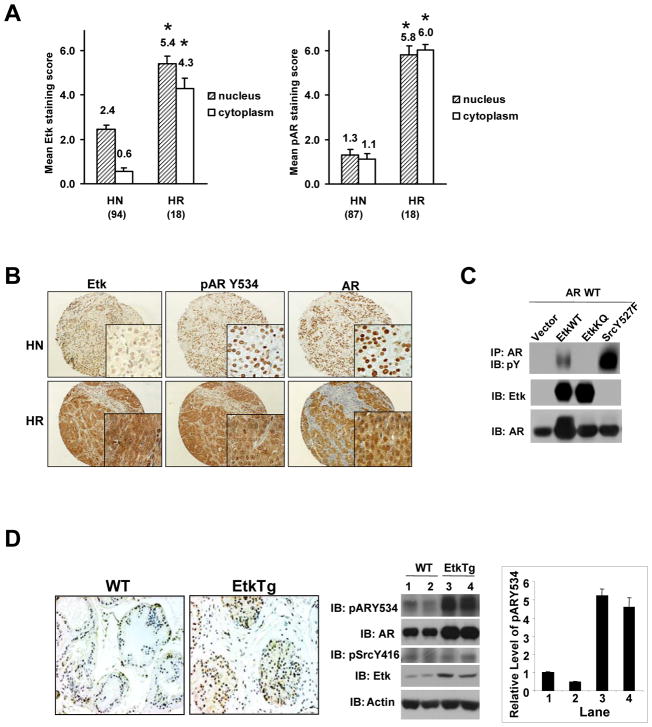

To examine Etk expression in human prostate tumors, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis on human prostate tissue arrays containing 94 hormone naïve and 18 hormone resistant samples. As summarized in Fig 2A, Etk immunoreactivity is dramatically increased in both cytoplasm and nucleus of human hormone resistant prostate tumor samples (mean score = 4.30 ± 0.45 and 5.42 ± 0.33 respectively) compared with hormone naïve samples (mean score = 0.57 ± 0.15 and 2.44 ± 0.22 respectively). In a previous study, we showed that phosphorylation of AR Y534 is elevated in hormone resistant prostate tumors and there is a moderate correlation between AR Y534 phosphorylation and active Src kinase. Src and Etk share some common substrates due to the high degree of homology of their kinase domains, thus we examined whether the increased Etk expression could also contribute to AR Y534 phosphorylation. Interestingly, correlation analysis revealed that Etk expression level in human prostate tumors is strongly correlated with phosphorylation of AR Y534 (Pearson correlation coefficient ρ= 0.71, P<0.0001). Fig 2B shows representative fields of human prostate tissue arrays. We then tested whether Etk can induce AR Y534 phosphorylation in co-transfection experiments using active SrcY527F mutant as a positive control. As shown in Fig 2C, wild-type Etk (EtkWT), but not kinase-inactive Etk (EtkKQ), induced AR tyrosine phosphorylation, though the magnitude of AR phosphorylation induced by Etk was not as great as that induced by active Src. We also found that phosphorylation of AR Y534 was increased in Etk transgenic prostates compared to wild-type control prostates, while Src activity in Etk transgenic prostates appeared to remain largely unchanged (Fig 2D). On the other hand, knock-down of endogenous Etk expression by a specific shRNA diminished AR Y534 phosphorylation in CWR-R1 cells (Supplemental Fig 3). Taken together, these data suggest that Etk may be another kinase, in addition to Src, responsible for phosphorylating AR Y534 in prostate cells.

Figure 2. Etk is upregulated in hormone refractory prostate cancer and induces AR tyrosine phosphorylation.

A, The mean scores and frequency of the immunoreactivity with anti-Etk or anti-pARY534 antibodies detected in hormone-naïve (HN), and hormone-refractory (HR) human prostate tumor arrays (TMAs). *p< 0.001, compared to HN. B, Representative fields of the TMAs. Anti-AR was used as a control. Low (X20) and high (X400) magnification views of Etk, pARY534, and AR expression in HN and HR prostate tumor were shown. C, Etk is associated with AR and induces AR tyrosine phosphorylation in COS-1 cells. COS-1 cells were co-transfected with the plasmids indicated. At 24h post-transfection, cells were serum starved overnight and then lysed. The association between Etk and AR was determined by immunoprecipitation with anti-AR antibody and followed by immunoblotting with anti-Etk antibody. The effects of Etk on AR tyrosine phosphorylation were examined by immunoprecipitation with anti-AR antibody and followed by immunblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine (pY) antibody. The levels of Etk or AR in the total cell lysates were monitored by immunoblotting with anti-Etk and anti-AR antibody respectively. D, Overexpression of Etk in mouse prostate induces AR tyrosine phosphorylation. Mouse prostates were dissected from the Etk transgenic and their WT littermate mice respectively. One half of the dorsolateral prostate lobes were fixed in 10% Formalin and subjected to immunohistochemical staining with anti-phosphorylated ARY534 antibody (Left). The lysates of the other half gland were subjected to immunoblotting with the antibodies as indicated (Center). The intensity of pARY534 and AR in each lane was quantified by using the software Quantity One and the change of pARY534 was normalized with AR (Right). The value in Lane 1 was set as 1.

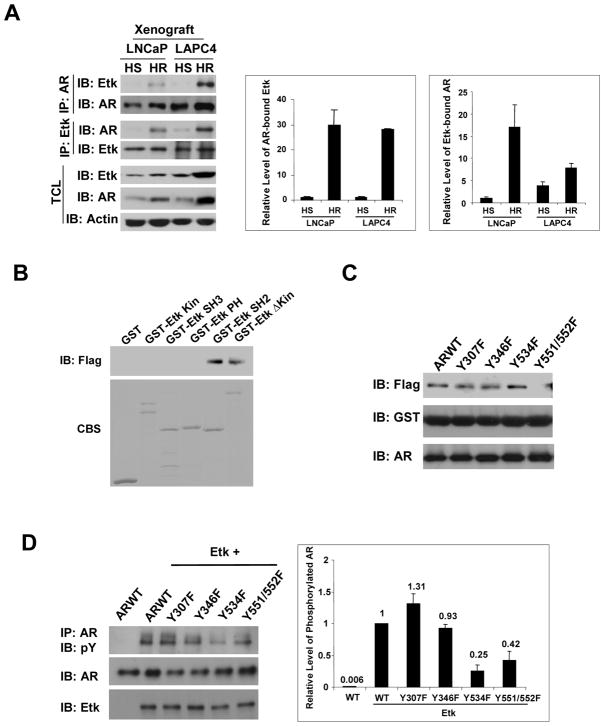

Castration promotes the association between Etk and AR in a phosphorylation-dependent manner

To assess whether Etk could play a role in regulation of AR signaling at the castratory levels of testosterone, we examined the association between Etk and AR in hormone sensitive and hormone refractory tumor xenografts in co-immunoprecipitation experiments. As shown in Fig 3A, the association between Etk and AR was increased in hormone refractory tumor xenografts compared with their hormone sensitive counterparts. To further investigate which domain(s) of Etk are involved in its interaction with AR, we performed GST pull-down experiments. Surprisingly, it appeared that only the fusion proteins containing the SH2 domain of Etk (GST-EtkSH2 and GST-EtkΔKin) were able to interact with AR (Fig 3B), implying that AR tyrosine phosphorylation may be involved in this interaction. To investigate whether AR tyrosine residues contribute to the association between Etk and AR, we examined several AR phosphorylation mutants that were established in our previous study on Src kinase induced AR phosphorylation in vivo (6). Fig 3C shows that the GST-Etk-SH2 protein can still pull-down ARY307F, Y346F and Y534F mutants but not the ARY551/552F mutant, suggesting that Y551/552 phosphorylation may be involved. It is well known that the SH2 domains of non-receptor tyrosine kinases preferentially bind to their substrates to enhance catalytic activity and substrate recognition (13). Therefore, we scanned the potential phosphorylation sites oar using the Motif Scan program (http://scansite.mit.edu/motifscan_seq.phtml) (23) and identified that Y551/552 may be a preferred phosphorylation site induced by the Tec family kinases. This is supported by the observation that Etk can still induce tyrosine phosphorylation of the ARY534F mutant and Y551/552F mutation diminished tyrosine phosphorylation of AR induced by Etk (Fig 3D). These data suggest that Etk may be able to phosphorylate AR at Y534 and Y551/552, and the interaction between the Etk SH2 domain and phosphorylated ARY551/552 may promote their association.

Figure 3. Castration promotes association between Etk and AR.

A, Association between Etk and AR in xenograft tumors is increased at post-castration. Hormone sensitive (HS) and hormone refractory (HR) LNCaP and LAPC4 xenograft tumors were derived as described in Methods. The total protein lysates extracted from these tumors were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-AR or anti-Etk antibody and followed by immunoblotting with anti-Etk or anti-AR antibody. Expression of Etk or AR was monitored by immunoblotting of the total cell lysates. Actin was used as a loading control. The intensity of AR-bound Etk or Etk-bound AR in each lane was quantified by using the software Quantity One and normalized with AR or Etk protein level (Right). The value of HS LNCaP was set as 1.

B, COS-1 cells were transfected with the Flag-tagged AR. Cell lysates were incubated with GST-Etk wt or GST-Etk mutants bound to glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads at 4 °C for 1 h. The beads were washed intensively, and the bound proteins were detected by immunoblotting with an anti-Flag antibody. The GST fusion proteins were visualized with Coomassie Blue staining (CBS). C, COS-1 cells were transfected with Flag-tagged AR wt or AR mutants. Cell lysates were incubated with GST-EtkSH2 bound to Glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads at 4 °C for 1 h. The beads were washed intensively, and the bound proteins were detected by immunoblotting with an anti-Flag antibody. The GST fusion proteins were detected with anti-GST. D, The effects of Y534F and Y551/552F mutation on Etk induced AR tyrosine phosphorylation. AR or AR mutants were co-transfected with Etk or the vector control into COS-1 cells. At 48h posttransfection, cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-AR and followed by immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine (pY). The expression of AR and Etk in total cell lysates was monitored by immunoblotting with the indicated antibody. The intensity of phosphorylated AR and AR in each lane was quantified by using the software Quantity One and the change of tyrosine phosphorylation was normalized with AR (Right). The value of phosphorylated ARWT was set as 100%.

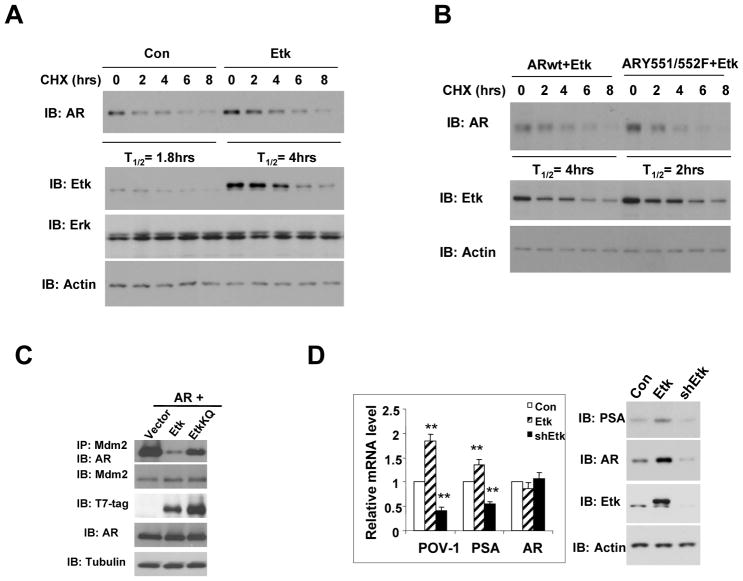

Etk stabilizes AR and promotes its activity under androgen-depleted conditions

We previously showed that overexpression of Etk in LNCaP and mouse prostate increases AR protein level (6), but this change was unlikely due to transcriptional regulation as our quantitative RT-PCR analysis did not detect appreciable change of AR mRNA when Etk was overexpressed or knocked down in LNCaP cells (Fig 4C). It is possible that regulation of AR expression by Etk may be through a mechanism at the posttranscriptional level. Therefore, we investigated whether the association with Etk could stabilize AR. Fig 4A shows that overexpression of Etk in LNCaP cells leads to an increase in the half-life of AR protein from 1.8 hours to 4 hours. On the other hand, knocking down endogenous Etk expression by a specific shRNA in CWR-R1 cells led to destabilization of AR protein (Supplemental Fig 4). Since ARY551/552 phosphorylation is necessary for the association between Etk and AR, we next asked whether the effect of Etk on the AR stability is mediated through ARY551/552. As expected, the half-life of the ARY551/552F mutant was reduced to 2 hours compared to the wild-type AR (T1/2 = 4 hours) in Etk-overexpressing cells (Fig 4B). These results suggest that Etk is associated with AR and stabilize AR in a manner dependent on the integrity of ARY551/552. Mdm2 was previously shown to regulate AR protein turnover in prostate cancer cells (24), therefore, we tested whether Etk could modulate the interaction between AR and Mdm2. As shown in Fig 4C, overexpression of Etk with AR in COS-1 significantly diminished the association of AR with endogenous Mdm2, while the kinase-inactive EtkKQ mutant had little effect. We further examined the effects of Etk on AR-regulated genes in LNCaP cells. PSA and POV-1/SLC43A1 are well established AR-regulated genes. Using quantitative RT-PCR, we found that overexpression of Etk significantly increased PSA and POV-1 mRNA level and knockdown of Etk by specific shRNA decreased the level of these transcripts (Fig 4D, left). Western blot analysis confirmed that Etk might modulate AR activity at least in part through regulation of the steady-state level of AR protein (Fig 4D, right).

Figure 4. Etk increases AR stability and transcriptional activity.

A, LNCaP cells were transfected with control vector or Etk. After serum-starvation, cells were treated with 0.1 ug/ ul Cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated time. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-AR, anti-Erk and anti-Etk respectively. Actin was used as a loading control. B, AR wt or ARY551/552F was cotransfected with Etk into COS-1 cells. After serum-starvation, cells were treated with 0.1 ug/ ul Cycloheximide for the time indicated. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-AR and anti-Etk. C, AR was cotransfected with T7-tagged Etk or EtkKQ into COS-1 cells. Association of AR with endogenous Mdm2 was detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-Mdm2, followed by immunoblotting with anti-AR. D, LNCaP cells were transfected with lenti-virus encoding Etk, shRNA specific for Etk or vector control. PSA, POV1 and AR mRNA level were detected by Quantitative real-time RT-PCR after serum-starvation overnight. **p < 0.01. The PSA, AR and Etk protein levels were detected by Western Blot.

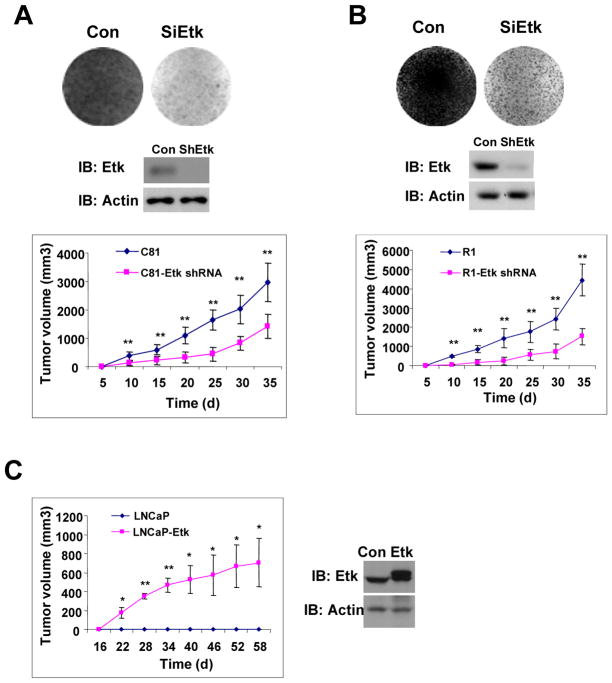

Because Etk expression was increased after androgen ablation in mouse and human prostates, we were interested in examining whether Etk expression is required for growth of hormone refractory prostate cancer cells. As shown in Fig 5A & B, knockdown of Etk expression in hormone refractory C-81 or CWR-R1 cells by shRNA specific for Etk inhibited growth of C-81 or CWR-R1 cells in androgen-depleted medium. Similar growth inhibition effects were also observed in the xenograft models. These data suggest that Etk is required for growth of C-81 or CWR-R1 both in vitro and in vivo. To further test whether Etk promotes castration-resistant tumor growth in the xenograft models, Etk or a control vector was transfected into LNCaP cells and then subcutaneously injected into castrated SCID mice. Fig 5C shows that growth of Etk-overexpressing cells was significantly increased compared to the control. Taken together, these results suggest that overexpression of Etk may promote castration-resistant tumor growth.

Figure 5. Etk promotes prostate tumor growth under androgen depleted conditions.

A–B, The effect of Etk shRNA on prostate cancer cell growth. C-81 (A) or CWR-R1 (B) cells were infected with the lenti-virus encoding shRNA specific for luciferase (control) or Etk. Cells were maintained in the medium containing 5% charcoal-stripped serum for two weeks. Cell colonies were visualized by Coomassie Blue Staining (CBS) (Top). Etk level was detected by immunoblotting at 48h post-infection (Middle). At 48h post-infection, cells were subcutaneously injected into castrated male nude mice respectively and tumor growth was measured as described in Methods (Bottom). **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. The results were presented as mean tumor volume ± SE (n =5 mice/group). C, Etk promotes prostate tumor growth. LNCaP cells were infected with lentivirus encoding Etk or the vector control. At 48h post-infection, cells were subcutaneously injected into castrated male SCID mice respectively and tumor growth was detected as described in Methods. The results were presented as mean tumor volume ± SE (n = 5 mice/group). **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. The levels of Etk were detected by Western blot at 48h post-infection.

DISCUSSION

The transition from hormone-sensitive to hormone-refractory state after androgen ablation therapy is a major obstacle in effective control of prostate cancer. Multiple mechanisms may be underlying this transition. In the present study, we demonstrated that tyrosine kinase Etk is upregulated in prostate cells in response to androgen deprivation and may play a role in castration-resistant progression of prostate cancer. This is supported by our observations that the association between Etk and AR is increased after castration and Etk induces tyrosine phosphorylation of AR, leading an increase in AR stability and transcriptional activity under androgen-depleted conditions. In addition, knock-down of Etk expression by specific shRNA leads to attenuation of prostate tumor growth under androgen-depleted conditions whereas overexpression of Etk promotes castration-resistant growth of prostate tumor xenografts. Therefore, Etk may be a component of the adaptive compensatory mechanism which protects prostate cells from androgen ablation and promotes prostate tumor growth, at least in part, through modulation of AR signaling pathway. It should be noted that Etk is also upregulated in normal mouse prostate in response to castration but is unable to stabilize AR. It is possible that additional changes in prostate tumors may facilitate the effects of Etk on regulation of AR stability.

Most castration-resistant prostate cancers continue to express AR at levels similar to androgen dependent prostate cancers, which indicates that AR still retains its function in castration-resistant prostate cancer. The persistence of AR in prostate cancer independent of circulating androgen levels suggests that AR is activated and thus stabilized by low levels of androgens or other ligand-independent mechanisms. It is known that several growth factors such as EGF/TGFα, IL-6 and IGF-1 and their downstream tyrosine kinases such as erbB2, Src and FAK, can activate AR and minimize or possibly even negate the requirement for ligand (18, 25–32). In the present study, we found that Etk, a downstream effector of PI3-kinase, Src and FAK, is dramatically upregulated in normal mouse prostates and human prostate tumors after androgen deprivation and stabilizes AR through posttranslational modifications. Although the magnitude of AR phosphorylation induced by wild-type Etk was not as dramatic as that induced by an active Src mutant, AR Y534 phosphorylation detected in human prostate tissues seems to have a stronger correlation with the level of Etk kinase (Pearson correlation coefficient ρ= 0.71, P<0.0001) than that with phosphorylated Src Y416 (Pearson correlation coefficient ρ= 0.33, P<0.0001) reported in our previous study (6). It is likely that detected AR Y534 phosphorylation in prostate tissues may be partly attributed to Etk kinase activity. The relative contribution of each kinase to the regulation of AR activity may depend on cellular context. It is possible that in cells with elevated Src activity, Src may play a major role as Src appears to be a stronger Y534 kinase. However, in those cells that Src activity is not elevated, Etk could be activated through different mechanisms such as via overexpression or PI3K/FAK pathways and become the key kinase for Y534. Such possibility is supported by a strong correlation between Etk expression level and Y534 phosphorylation in human prostate tumors. It is possible that Etk kinase might be activated by some stimuli (e.g. IL6, neuropeptides, matrix proteins, ROS, etc) up-regulated in prostate tissues upon androgen deprivation. In addition to Y534, Etk may also induce phosphorylation of Y551/552 embedded in the preferred substrate sequence for Tec family kinases. This is supported by the diminished tyrosine phosphorylation of the AR Y551/552 mutant compared to the wild-type AR. Mutation of Y551/552 residues disrupted association of AR with the SH2 domain of Etk, suggesting that the interface between AR and Etk may be very different from that between AR and Src, which is believed to involve the proline-rich region of AR and the SH3 domain of Src (33). This possibility is supported by our observation that Etk-induced Y534 phosphorylation is dependent on the integrity of Y551/552 while Y551/552F mutation has little effect on Src-induced Y534 phosphorylation (Supplemental Fig 5). It is still not clear whether these proteins are present in a common, independent or sequential signaling complex. Regulation of AR activity by multiple kinases may allow fine-tune control of its signaling temporally and spatially in response to diverse extracellular stimuli.

In addition, Etk expression is differentially regulated by androgen and IL-6 in prostate cells and AR is differentially recruited to the AREs located in the ETK locus, suggesting that Etk may serve as an integrator of both steroid hormone and growth factor signaling. It has yet to be determined how differential regulation of ETK by androgens and IL-6 occurs in prostate cells. It is possible that AR may be associated with different protein complexes or cooperate with different transcription factors in prostate cancer cells in response to various stimuli. Further experiments are necessary to investigate detailed mechanisms by which Etk is regulated by AR.

Taken together, our findings suggest that compensatory upregulation of Etk in response to androgen-derivation may promote castration-resistant growth of prostate cancer, at least partially through modulation of AR signaling pathway and Etk may potentially serve as a diagnostic marker and drug target for prostate cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH grants (CA106504), DOD grants (W81XWH-08-1-0174) to Y.Q. and the NIH grant (NCI UO1- CA86772) to J.M., DOD Pre-doctoral Fellowship (W81XWH-08-1-0068) to D.E.L.

References

- 1.Feldman BJ, Feldman D. The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:34– 45. doi: 10.1038/35094009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heinlein CA, Chang C. Androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:276– 308. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Culig Z, Klocker H, Bartsch G, Hobisch A. Androgen receptors in prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2002;9:155–70. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0090155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scher HI, Buchanan G, Gerald W, Butler LM, Tilley WD. Targeting the androgen receptor: improving outcomes for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:459– 76. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, Baek SH, Chen R, Vessella R, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10:33–9. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo Z, Dai B, Jiang T, Xu K, Xie Y, Kim O, et al. Regulation of androgen receptor activity by tyrosine phosphorylation. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:309–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahajan NP, Liu Y, Majumder S, Warren MR, Parker CE, Mohler JL, et al. Activated Cdc42-associated kinase Ack1 promotes prostate cancer progression via androgen receptor tyrosine phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8438–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700420104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DaSilva J, Gioeli D, Weber MJ, Parsons SJ. The neuroendocrine-derived peptide parathyroid hormone-related protein promotes prostate cancer cell growth by stabilizing the androgen receptor. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7402–11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu Y, Robinson D, Pretlow TG, Kung HJ. Etk/Bmx, a tyrosine kinase with a pleckstrin-homology domain, is an effector of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase and is involved in interleukin 6-induced neuroendocrine differentiation of prostate cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3644–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamagnone L, Lahtinen I, Mustonen T, Virtaneva K, Francis F, Muscatelli F, et al. BMX, a novel nonreceptor tyrosine kinase gene of the BTK/ITK/TEC/TXK family located in chromosome Xp22.2. Oncogene. 1994;9:3683–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen R, Kim O, Li M, Xiong X, Guan JL, Kung HJ, et al. Regulation of the PH-domain-containing tyrosine kinase Etk by focal adhesion kinase through the FERM domain. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:439–44. doi: 10.1038/35074500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim O, Yang J, Qiu Y. Selective activation of small GTPase RhoA by tyrosine kinase Etk through its pleckstrin homology domain. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30066–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Filippakopoulos P, Kofler M, Hantschel O, Gish GD, Grebien F, Salah E, et al. Structural coupling of SH2-kinase domains links Fes and Abl substrate recognition and kinase activation. Cell. 2008;134:793–803. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paavonen K, Ekman N, Wirzenius M, Rajantie I, Poutanen M, Alitalo K. Bmx tyrosine kinase transgene induces skin hyperplasia, inflammatory angiogenesis, and accelerated wound healing. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4226–33. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chau CH, Clavijo CA, Deng HT, Zhang Q, Kim KJ, Qiu Y, et al. Etk/Bmx mediates expression of stress-induced adaptive genes VEGF, PAI-1, and iNOS via multiple signaling cascades in different cell systems. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C444–54. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00410.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim O, Jiang T, Xie Y, Guo Z, Chen H, Qiu Y. Synergism of cytoplasmic kinases in IL6-induced ligand-independent activation of androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:1838–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang T, Guo Z, Dai B, Kang M, Ann DK, Kung HJ, et al. Bi-directional regulation between tyrosine kinase Etk/BMX and tumor suppressor p53 in response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50181–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee LF, Guan J, Qiu Y, Kung HJ. Neuropeptide-induced androgen independence in prostate cancer cells: roles of nonreceptor tyrosine kinases Etk/Bmx, Src, and focal adhesion kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:8385–97. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8385-8397.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai B, Kim O, Xie Y, Guo Z, Xu K, Wang B, et al. Tyrosine kinase Etk/BMX is up-regulated in human prostate cancer and its overexpression induces prostate intraepithelial neoplasia in mouse. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8058–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo Z, Yang X, Sun F, Jiang R, Linn DE, Chen H, et al. A novel androgen receptor splice variant is up-regulated during prostate cancer progression and promotes androgen depletion-resistant growth. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2305–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang XQ, Lee MS, Zelivianski S, Lin MF. Characterization of a prostate-specific tyrosine phosphatase by mutagenesis and expression in human prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2544–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gregory CW, Johnson RT, Jr, Mohler JL, French FS, Wilson EM. Androgen receptor stabilization in recurrent prostate cancer is associated with hypersensitivity to low androgen. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2892–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obenauer JC, Cantley LC, Yaffe MB. Scansite 2.0: proteome-wide prediction of cell signaling interactions using short sequence motifs. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:3635–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin HK, Wang L, Hu YC, Altuwaijri S, Chang C. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitylation and degradation of androgen receptor by Akt require Mdm2 E3 ligase. Embo J. 2002;21:4037–48. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartlett JM, Brawley D, Grigor K, Munro AF, Dunne B, Edwards J. Type I receptor tyrosine kinases are associated with hormone escape in prostate cancer. J Pathol. 2005;205:522–9. doi: 10.1002/path.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Lorenzo G, Tortora G, D’Armiento FP, De Rosa G, Staibano S, Autorino R, et al. Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor correlates with disease relapse and progression to androgen-independence in human prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3438–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Best CJ, Gillespie JW, Yi Y, Chandramouli GV, Perlmutter MA, Gathright Y, et al. Molecular alterations in primary prostate cancer after androgen ablation therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6823–34. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krueckl SL, Sikes RA, Edlund NM, Bell RH, Hurtado-Coll A, Fazli L, et al. Increased insulin-like growth factor I receptor expression and signaling are components of androgen-independent progression in a lineage-derived prostate cancer progression model. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8620–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorenzo GD, Bianco R, Tortora G, Ciardiello F. Involvement of growth factor receptors of the epidermal growth factor receptor family in prostate cancer development and progression to androgen independence. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2003;2:50–7. doi: 10.3816/cgc.2003.n.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ueda T, Mawji NR, Bruchovsky N, Sadar MD. Ligand-independent activation of the androgen receptor by interleukin-6 and the role of steroid receptor coactivator-1 in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38087–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203313200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Craft N, Shostak Y, Carey M, Sawyers CL. A mechanism for hormone-independent prostate cancer through modulation of androgen receptor signaling by the HER-2/neu tyrosine kinase. Nat Med. 1999;5:280–5. doi: 10.1038/6495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee LF, Louie MC, Desai SJ, Yang J, Chen HW, Evans CP, et al. Interleukin-8 confers androgen-independent growth and migration of LNCaP: differential effects of tyrosine kinases Src and FAK. Oncogene. 2004;23:2197–205. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Migliaccio A, Castoria G, Di Domenico M, de Falco A, Bilancio A, Lombardi M, et al. Steroid-induced androgen receptor-oestradiol receptor beta-Src complex triggers prostate cancer cell proliferation. Embo J. 2000;19:5406–17. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.