Background: O-Glucosylation of EGF repeats occurs at high but variable stoichiometries on Notch.

Results: In vitro assays revealed that the variability in glycosylation depends on the amino acid sequence and three-dimensional structure of individual EGF repeats.

Conclusion: Proper folding and amino acid sequence of individual EGF repeats determine O-glucosylation efficiency.

Significance: This work provides a regulatory mechanism for site-specific O-glucosylation on individual EGF repeats.

Keywords: Glycobiology, Glycosylation, Glycosyltransferases, Mass Spectrometry (MS), Notch, EGF Repeats

Abstract

O-Glucosylation of epidermal growth factor-like (EGF) repeats in the extracellular domain of Notch is essential for Notch function. O-Glucose can be elongated by xylose to the trisaccharide, Xylα1–3Xylα1–3Glcβ1-O-Ser, whose synthesis is catalyzed by the consecutive action of three glycosyltransferases. A UDP-glucose:protein O-glucosyltransferase (Poglut/Rumi) transfers O-glucose to serine within the O-glucose consensus. Subsequently, either of two UDP-xylose:glucoside xylosyltransferases (Gxylt1 or Gxylt2) transfers xylose to O-glucose. Finally, a UDP-xylose:xyloside xylosyltransferase (Xxylt1) transfers xylose to Xylα1–3Glcβ1-O-EGF. Our prior site-mapping studies demonstrated that O-glucose consensus sites are modified at high but variable stoichiometries in mouse Notch1 and identified a novel glycosylation site with alanine in place of proline, suggesting a revised, broader consensus sequence (CXSX(P/A)C). Here we examined the molecular basis for this site specificity. A panel of EGF repeats from human coagulation factor 9 (FA9), mouse Notch1, and Notch2 were bacterially expressed and purified by reverse phase HPLC for use in in vitro enzyme assays. We demonstrate that proper folding of EGF repeats is essential for glycosylation by Poglut/Rumi, that alanine can substitute for proline in the context of coagulation factor 9 EGF repeat for O-glucose transfer, confirming the new consensus sequence, and that positively charged residues within the O-glucose consensus sequence reduce efficiency of glycosylation by Poglut/Rumi. Moreover, proper folding of EGF repeats is also important for the activities of Gxylt1, Gxylt2, and Xxylt1. These results indicate that protein folding and amino acid sequences of individual EGF repeats fundamentally affect both attachment and elongation of O-glucose glycans.

Introduction

The Notch signaling pathway plays important roles for cell fate determination during development and into adulthood, and dysregulation of the pathway is linked to a number of human diseases (1, 2). Notch activity is regulated at numerous levels, including glycosylation of the extracellular domain (3, 4). The Notch extracellular domain contains up to 36 tandem epidermal growth factor-like (EGF) repeats (1) that can be modified with O-linked fucose, glucose, or N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) (3). Fringe, a known Notch regulator, is a β3-N-acetylglucoaminyltransferase that elongates O-fucose by adding GlcNAc, thereby regulating Notch ligand binding (5, 6). The addition of O-fucose to EGF repeats is catalyzed by protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 (Pofut1)2 in mammals (Ofut1 in Drosophila) (7). Genetic and biochemical studies have shown that O-fucosylation is essential for Notch function in both flies and mice (8, 9). O-GlcNAc is added to EGF repeats by a novel extracellular O-GlcNAc transferase (10, 11), but elimination of EOGT in flies does not appear to affect Notch activity (12). We previously identified a CAP10-like protein O-glucosyltransferase (Poglut) that transfers O-glucose to the serine in the consensus sequence of EGF repeats (gene name rumi) (13). Mutations in rumi cause temperature-sensitive defects in the trafficking and folding of Notch in Drosophila (13). Three mammalian Rumi homologues exist, but only the Rumi gene with the highest homology to Drosophila rumi encodes a Poglut that catalyzes O-glucosylation on the EGF repeats (14, 15). Elimination of the Poglut/Rumi gene in mice results in embryonic lethality with Notch-like phenotypes (14). O-Glucose can be elongated to a trisaccharide with the structure Xylα1–3Xylα1–3Glcβ1-O-EGF (16, 17). Two human genes encoding enzymes with UDP-xylose:glucoside α3-xylosyltransferase activity have been identified, GXYLT1 and GXYLT2 (18), as well as a third gene (XXYLT1) encoding an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localized UDP-xylose:xyloside α3-xylosyltransferase (19). However, the functional significance of O-glucose elongation by these enzymes for Notch signaling is not yet known.

EGF repeats are small protein domains (∼40 amino acids) found in hundreds of cell surface and secreted proteins in metazoans (20). Each has six cysteines forming three disulfide bonds (Cys-1–Cys-3, Cys-2–Cys-4, Cys-5–Cys-6), although 76 combinations of folding isomers can theoretically exist (3). Although the primary sequence and the number of amino acids vary among EGF repeats, the disulfide-bonding pattern gives them a characteristic three-dimensional structure. Interestingly, Pofut1 will only add O-fucose to a properly folded EGF repeat (21). Even EGF repeats with mis-paired disulfide bonds are not modified. Fringe also prefers folded EGF repeats for transfer of GlcNAc (22, 23). Both results suggest that these enzymes recognize the three-dimensional structure of EGF repeats they modify. In addition, Fringe shows specificity for O-fucose on some EGF repeats over others, suggesting that the amino acid sequence of individual EGF repeats affects the efficiency of modification by Fringe (22, 24).

O-Glucose modification of the hydroxyl group of serine occurs between the first and the second conserved cysteine of EGF repeats at the consensus sequence, CXSXPC (25). In a recent comprehensive analysis of O-glucose modifications on mouse Notch1 (mN1), we found that all 16 sites with this sequence are modified with O-glucose trisaccharide (26). We found a 17th O-glucosylation modification within EGF9 at the sequence CASAAC, suggesting that alanine can replace proline in the consensus sequence. Another site with the sequence CGLRC was not modified, suggesting that arginine cannot replace proline (26). Using semiquantitative glycoproteomic methods, we found that most sites are modified at high stoichiometries (e.g. EGF12 from mN1), whereas others are only partially modified (e.g. EGF27 from mN1 (26) and EGF16 from mouse Notch2 (mN2) (14)). We also found an O-xylose modification at the O-glucose consensus site of EGF16 from mN2 and demonstrated that Poglut/Rumi utilizes UDP-xylose as well as UDP-glucose as donor substrate (15). The presence of a di-serine motif within the O-glucose consensus sequence, as found in mN2 EGF16, appears to enhance use of UDP-xylose by Poglut/Rumi (15).

Although previous studies suggested an essential role of O-glucose glycans for Notch signaling (13, 14, 26), the molecular mechanism by which O-glucose glycans activate Notch receptors is still unclear. Given that the extracellular domain of Notch contains multiple potential O-glucose attachment sites, information about the occupancy and elongation status at each site of Notch is necessary for further functional analysis. Multiple O-glucosylation sites are suggested to function as a buffer against temperature-dependent loss of Notch signaling in Drosophila (27).

Our site-mapping analysis suggests that O-glucosylation occurs at high, but variable stoichiometry in mN1 produced in cell lines (26). We hypothesize that this variability in site-specific O-glucosylation is due to specific sequence differences encoded in individual EGF repeats. As an initial step to examine this hypothesis, we produced a number of EGF repeats in bacteria (that do not add O-glucose glycans) and tested them in vitro as substrates for the glycosyltransferases that modify the EGF repeats with the O-glucose glycans. Our results suggest that specific features of the EGF repeat influence how well they are recognized by these enzymes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

HEK-293T cells from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. UDP-[6-3H]glucose (2.22 TBq/mmol) and UDP-[U-14C]xylose (5.43 GBq/mmol) were purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). Nonradioactive UDP-α-d-xylose was purchased from Complex Carbohydrate Research Center at the University of Georgia (supported in part by National Science Foundation-Research Coordination Networks Grant 0090281). Constructs encoding FLAG-tagged human Poglut/Rumi (14), Myc-His6-tagged human Poglut/Rumi (15), Myc-His6-tagged mouse Gxylt2 and Xxylt1 (19), His6-tagged human Pofut1 lacking its C-terminal RDEF sequence (28), and Myc-His6-tagged mouse Lunatic Fringe (LFng) (23) were all previously described. All other reagents were of the highest quality available.

Vector Construction for Expression of Gxylt1

The cDNA encoding the luminal domain of mouse Gxylt1 (18), starting from Leu-30, was amplified using a standard PCR method with two primers (forward, 5′-ATATATAAGCTTTGGAGGAAGGAGCTG-3′; reverse, 5′-ATCTAGCTCGAGCCCTTTCCTTCGGTGG-3′) and then inserted into pSecTag2 vector (Invitrogen) so that the recombinant protein was expressed with a C-terminal Myc-His6 tag and secreted into the culture media. DNA sequence of the construct was confirmed by sequencing.

Purification of the Myc-His6-or FLAG-tagged Proteins by Nickel-nitrilotriacetate Chromatography

Myc-His6-tagged Poglut/Rumi, Gxylt1, Gxylt2, and Xxylt1 glycosyltransferase proteins from HEK-293T cells transiently transfected with the expression vectors were purified as described in Du et al. (29). Protein concentrations of FLAG-tagged Poglut/Rumi and Myc-His6-tagged Poglut/Rumi, Gxylt1, or Xxylt1 were determined by Coomassie staining using BSA as a standard. Protein concentration of Myc-His6-tagged Gxylt2 was determined by Western blot analysis with mouse anti-Myc monoclonal antibody (9E10, Sigma) and Alexa Fluor 680-labeled rabbit anti-mouse IgG (H+L) antibody (Molecular Probes) followed by data analysis with Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR) using known amounts of recombinant Myc-His6-tagged Gxylt1 as a standard.

Preparation and in Vitro Glycosylation of EGF Repeats

All EGF repeats from human FA9, mN1, and mN2 were expressed in BL21(DE3) cells and purified as described previously (24). The mutants of human FA9 EGF repeats were prepared by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis as described previously (30). The cDNAs encoding mN1 EGF repeats or mN2 EGF16 were amplified by standard PCR using plasmids encoding mN1 (a kind gift from Dr. Raphael Kopan, Washington University) or mN2 (a kind gift from Dr. Shigeru Chiba, The University of Tokyo) as template and overlapping modified forward and reverse primers to create restriction sites for insertion into pET-20b(+) vector (Stratagene). Sequences of the primers are available upon request. The DNA sequences of the inserts were confirmed by sequencing, and the proteins were expressed in BL21(DE3) cells and purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetate affinity chromatography as described (24). The amino acid sequences of EGF repeats are summarized in supplemental Table 1.

In vitro O-glucosylation of EGF repeats was performed using a modified Poglut/Poxylt assay. A 100-μl reaction mixture contained 50 mm HEPES, pH 6.8, 10 mm MnCl2, 10 μm acceptor substrates, 200 μm UDP-glucose, and purified Poglut/Rumi. For elongation with xylose, 200 μm UDP-xylose was used as donor substrate. For reaction with Pofut1 and LFng, 200 μm GDP-fucose and 200 μm UDP-GlcNAc were used as donor substrates. Approximately 500 ng of each recombinant enzyme was used. The reaction was performed at 37 °C overnight. The reaction products were purified by reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC, Agilent Technologies, 1200 Series) equipped with a C18 column (10 × 250 mm, Vydac) with a linear gradient of solvent B (80% acetonitrile, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water) from 10 to 90% in solvent A (0.1% TFA in water) for 60 min, monitoring absorbance at 214 nm. Elution profiles between 20 and 30 min are shown as milliabsorbance unit. Elution profiles between 20 and 28 min are shown only in the right panel of Fig. 3A. Peak fractions were pooled, dried down in a SpeedVac centrifuge, and stored at −20 °C for further analysis.

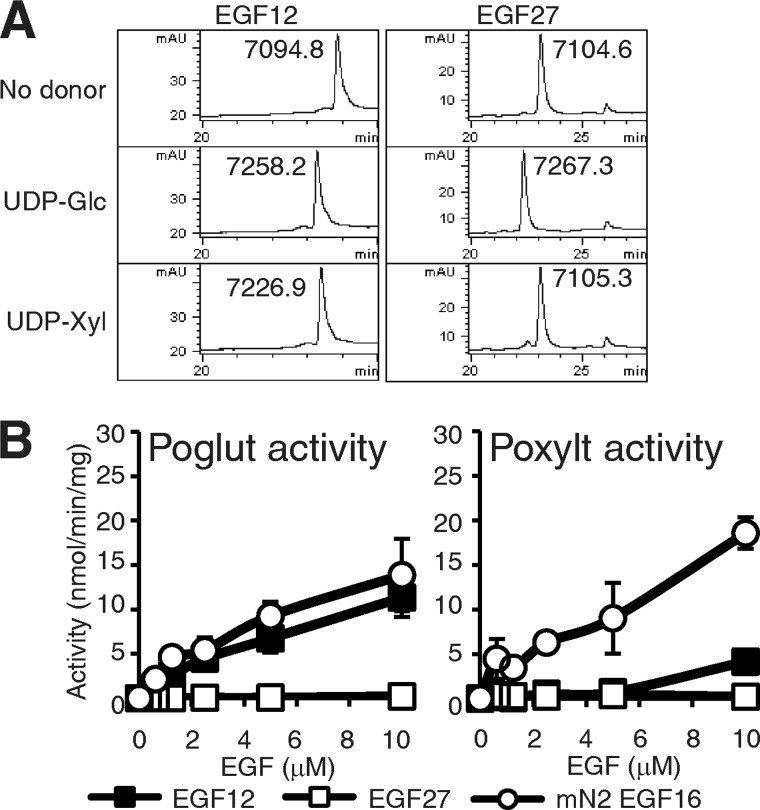

FIGURE 3.

Poglut and Poxylt activities of Poglut/Rumi vary among EGF repeats. A, RP-HPLC elution profiles are shown of the reaction mixtures of mN1 EGF12 or EGF27 incubated with Poglut/Rumi in the absence of donor (top) or in the presence of UDP-Glc (middle) or UDP-Xyl (bottom) for 10 h. mAU, milli-absorbance units. B, shown is Rumi Poglut (left) or Poxylt activity (right) toward mN1 EGF12, EGF27, or mN2 EGF16 in kinetic assays. The values indicate the mean ± S.E.

Reduction and Alkylation of EGF Repeats

EGF repeats were denatured as previously described with slight modification (30). Briefly, EGF repeats were dissolved in 0.4 m ammonium bicarbonate containing 8 m urea and 10 mm dithiothreitol and incubated at 50 °C for 15 min. The reduced samples were alkylated with 20 mm iodoacetamide in the dark at room temperature for 15 min and then purified by RP-HPLC as above.

Mass Spectrometric Analysis of EGF Repeats

Mass spectrometric analysis by infusion was performed as described previously (24). Briefly, dried samples were resuspended in 0.1% formic acid and 19% acetonitrile in water and directly infused into an Agilent 6340 ion-trap mass spectrometer with a nano-HPLC CHIP-Cube interface at a rate of 18 μl/h. The MS peaks for MS/MS were chosen manually, and the data were analyzed using Agilent ChemStation data analysis software. The masses of EGF repeats with different charge states measured by infusion mass spectrometric analysis were deconvoluted and shown on the top of peaks in HPLC profiles.

Kinetic Glycosyltransferase Assay

Poglut assays were performed as previously described (13, 30). Briefly, a 10-μl reaction mixture contained 50 mm HEPES, pH 6.8, 10 mm MnCl2, the indicated amounts of acceptor substrates, 0.16 μm UDP-[6-3H]glucose (2.22 TBq/mmol), 10 μm UDP-glucose, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and purified proteins. For Poxylt assay or assay with Gxylt1, Gxylt2, or Xxylt1, 10 μm UDP-[U-14C]xylose (5.43 GBq/mmol) was used as donor substrate. The reaction was performed at 37 °C for 20 min and stopped by adding 900 μl of 100 mm EDTA, pH 8.0. The sample was loaded onto a C18 cartridge (100 mg, Agilent Technologies). After the cartridge was washed with 5 ml of H2O, the EGF repeat was eluted with 1 ml of 80% methanol. Incorporation of [6-3H]glucose or [U-14C]xylose into the EGF repeats was determined by scintillation counting of the eluate. Reactions without substrates were used as background control. Data are from three independent assays. The values indicate the mean ± S.E.

RESULTS

Poglut/Rumi Only Modifies Properly Folded EGF Repeats

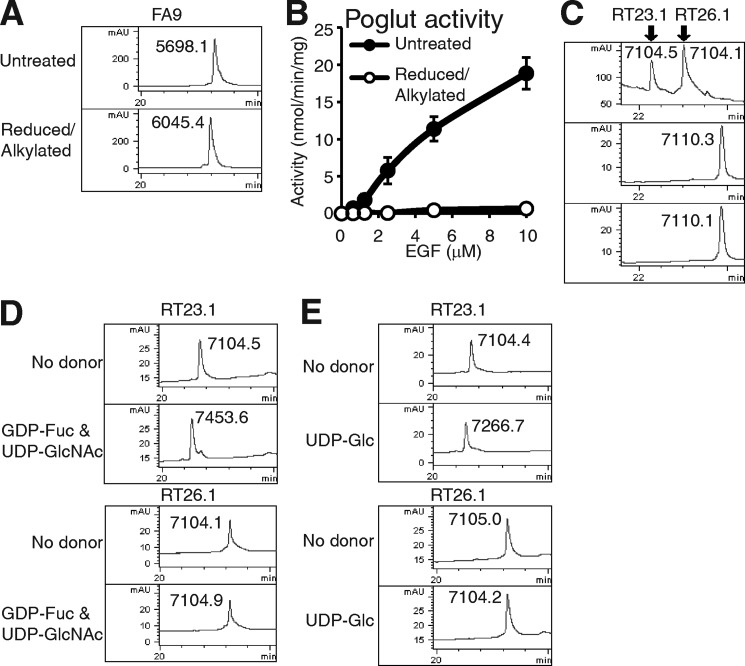

Prior studies showed that Pofut1 only modifies properly folded EGF repeats (21), and our initial characterization of Poglut activity in crude cellular extracts suggested that O-glucose addition also requires a folded EGF repeat (30). To examine whether purified Poglut/Rumi requires folded EGF repeats, we denatured FA9 EGF repeat by reduction and alkylation and purified it by RP-HPLC. Reduction and alkylation were confirmed by mass spectrometry (Fig. 1A). Purified Poglut/Rumi only modified intact FA9 EGF repeat in either kinetic analysis (Fig. 1B) or during overnight incubation (supplemental Fig. S1), indicating a folded EGF repeat is required for the activity.

FIGURE 1.

Poglut/Rumi differentiates folding isomers of EGF repeats. A, RP-HPLC analysis of untreated control or reduced/alkylated FA9 EGF repeat is shown. The masses of the species in each peak, which were determined by mass spectrometry, are shown. Note that the mass was increased by 347.3 after reduction and alkylation, which corresponded to modification with carbamidomethyl groups at all six cysteine residues. mAU, milli-absorbance units. B, Poglut activity of Poglut/Rumi using native (filled circles) or reduced and alkylated (open circles) FA9 EGF repeat is shown. The values indicate the mean ± S.E. C, elution profiles of mN1 EGF27 folding isomers (top, RT23.1 and RT26.1). RT23.1 (middle) and RT26.1 (bottom) eluted at the same elution time after reduction to break the disulfide bonds. Note that there was the same, six-mass increase for both species, which corresponded to reduction of all three disulfide bonds. D, after the folding isomers of mN1 EGF27 were incubated overnight with Pofut1 and LFng in the absence (top) or the presence (bottom) of GDP-fucose (Fuc) and UDP-GlcNAc, the reaction mixtures were applied to RP-HPLC. The elution profiles are shown, and masses of each species were determined. E, after the folding isomers of mN1 EGF27 were incubated with Poglut/Rumi in the absence (top) or the presence of UDP-glucose (Glc) (bottom), the reaction mixtures were applied to RP-HPLC. The elution profiles are shown, and determined masses are indicated. The theoretical masses of EGF repeats are summarized in supplemental Table 2.

Previous work on Pofut1 also suggested that it only modifies EGF repeats with the proper disulfide bonding pattern (21). To examine whether Poglut/Rumi can also differentiate disulfide isoforms of EGF repeats, we took advantage of the fact that bacterially expressed mN1 EGF27 contains two major species when analyzed by RP-HPLC (Fig. 1C). Mass spectral analysis showed that these had the same molecular weight, consistent with the presence of three disulfide bonds in both species. After these two species were denatured by reduction only (no iodoacetamide), they eluted at the same position on RP-HPLC with a mass consistent with the reduction of all six cysteines (Fig. 1C). The fact that the folded forms of these species have the same mass but separate by RP-HPLC strongly suggests that they are folding isomers with three disulfide bonds each. In addition to an O-glucose site, EGF27 contains an O-fucose site, allowing us to determine which isomer is properly folded. Both species were incubated with Pofut1, GDP-fucose, LFng, and UDP-GlcNAc and rerun on HPLC (Fig. 1D). LFng was included because GlcNAc modification causes a larger shift on RP-HPLC than fucose by itself. After incubation with Pofut1 and LFng in the presence or absence of appropriate donor substrates, only the earlier peak (RT23.1) shifted (Fig. 1D). Mass spectral analysis showed that EGF27 in the earlier peak (RT23.1) was modified with an O-fucose disaccharide, but EGF27 in the latter peak (RT26.1) was not. These results indicated that the earlier peak (RT23.1) contained properly folded EGF27.

Using these isoforms of EGF27, we examined whether the folding status of EGF repeats affects the glycosyltransferase activity of Poglut/Rumi. After incubation with Poglut/Rumi in the absence or presence of UDP-glucose, only the earlier peak (RT23.1) shifted (Fig. 1E). Mass spectral analysis showed that EGF27 in the earlier peak (RT23.1) was modified with a single O-glucose, but EGF27 in the latter peak (RT26.1) was not. Similar results were obtained from the experiments using folding isomers of EGF16 from mN1 (supplemental Fig. S2). These results demonstrated that Poglut/Rumi only transferred O-glucose to properly folded EGF repeats, indicating that the enzyme recognizes a specific three-dimensional structure, not simply a linear consensus sequence.

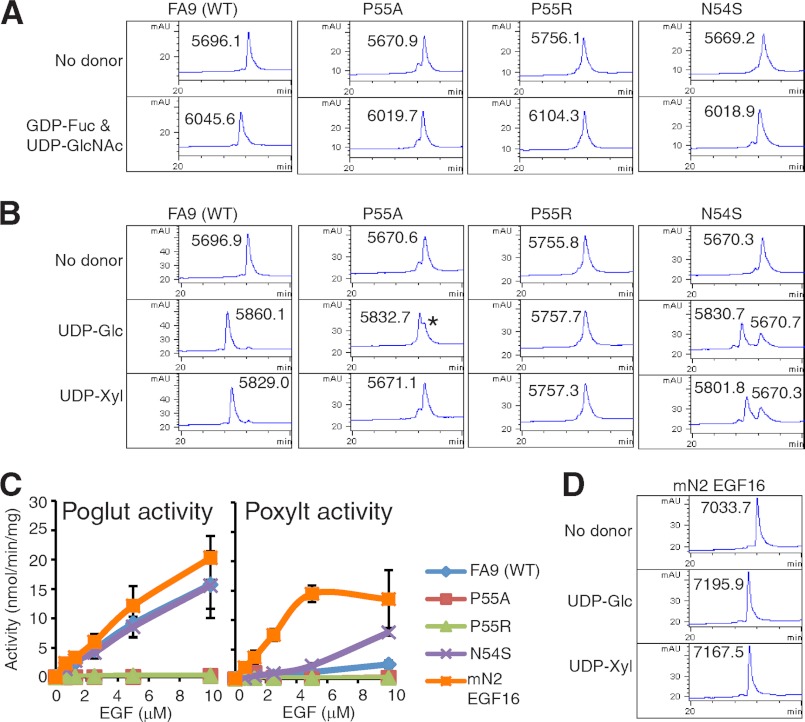

Sequences within the O-Glucose Consensus Sequence Affect Poglut and Poxylt Activities of Poglut/Rumi

Our recent site-mapping analysis on mN1 showed that EGF9 is O-glucosylated at high stoichiometry, whereas EGF35 is not (26). EGF9 contains the sequence CASAAC, whereas EGF35 contains CGSLRC, suggesting that alanine, but not arginine, may be allowed in place of proline in the O-glucose consensus sequence, CXSXPC. To test if this is generally true or just specific for these EGF repeats, we replaced proline with alanine or arginine in the O-glucose consensus sequence of FA9 EGF. Because the mutations could result in misfolding of the EGF repeat and Poglut/Rumi is sensitive to misfolding (Fig. 1), we again used O-fucosylation to test for folding. Wild type FA9 EGF repeat, P55A mutant, and P55R mutant were fully modified by Pofut1 and LFng after overnight incubation, suggesting they were all properly folded (Fig. 2A). To determine whether Poglut/Rumi modifies these EGF repeats, we incubated each with Poglut/Rumi in the presence or absence of donor substrates, UDP-glucose or UDP-xylose (for Poglut or Poxylt, activities of Poglut/Rumi (15)), and analyzed the products by RP-HPLC (Fig. 2B). Wild type FA9 showed a complete shift after incubation with UDP-glucose or UDP-xylose, and mass spectral analysis confirmed the addition of hexose or pentose. Interestingly, the P55A mutant showed a partial shift after incubation with UDP-glucose but no shift after incubation with UDP-xylose, suggesting this mutant can be modified by O-glucose, although poorly, but not by O-xylose (Fig. 2B). The P55R mutant showed no shift after incubation with Poglut/Rumi and with UDP-glucose or UDP-xylose (Fig. 2B), suggesting the arginine completely inhibited transfer of either O-glucose or O-xylose. Using these EGF repeats, we also tested the Poglut and Poxylt activities of Poglut/Rumi using a kinetic radioactive assay (Fig. 2C). Neither mutant showed significant activity compared with wild type using this assay. These results showed that arginine cannot substitute for proline in the consensus sequence for either Poglut or Poxylt activity of Poglut/Rumi in multiple contexts. In contrast, alanine can substitute for proline in the case of Poglut activity (but not Poxylt activity), although it was a poor substrate for Poglut/Rumi in the context of FA9 EGF.

FIGURE 2.

Amino acid sequence within the O-glucose consensus affects Poglut and Poxylt activities of Poglut/Rumi. A, RP-HPLC elution profiles are shown of the reaction mixtures of FA9 EGF repeat wild type (WT), P55A, P55R, or N54S incubated with Pofut1 and LFng in the absence (top) or the presence of GDP-Fuc and UDP-GlcNAc (bottom) for 10 h. mAU, milli-absorbance units. B, RP-HPLC elution profiles are shown of the reaction mixtures of FA9 EGF repeat WT, P55A, P55R, or N54S incubated with Poglut/Rumi in the absence of donor (top) or in the presence of UDP-Glc (middle) or UDP-xylose (Xyl) (bottom) for 10 h. Masses of each species were determined. When FA9 (P55A) was incubated with Poglut/Rumi and UDP-Glc, there was a peak containing unmodified substrate whose mass was detected as 5670.7 (indicated by *). C, Rumi Poglut (left) or Poxylt activity (right) toward FA9 WT, P55A, P55R, or N54S in kinetic assays is shown. mN2 EGF16 was also used as acceptor substrate. The values indicate mean ± S.E. D, elution profiles of the reaction mixtures of mN2 EGF16 incubated with Poglut/Rumi in the absence of donor (top) or in the presence of UDP-Glc (middle) or UDP-Xyl (bottom) for 10 h on RP-HPLC are shown, and masses of each species were determined.

Our recent site-mapping and biochemical analyses showed that mN2 EGF16 is modified with O-xylose glycans as well as O-glucose glycans due to the presence of a di-serine motif inside the O-glucose consensus sequence (15). To examine whether mN2 EGF16 is a better substrate for O-xylose transfer in vitro than other EGF repeats, we expressed it in bacteria and incubated overnight with Poglut/Rumi and UDP-glucose or UDP-xylose (Fig. 2D). In both cases, a full shift was observed, and the addition of glucose or xylose was confirmed by mass spectrometry. We also introduced a di-serine motif into the O-glucose consensus sequence of FA9 EGF to test whether this would enhance Poxylt activity of Poglut/Rumi. The N54S mutant could be modified by Pofut1 and Lfng, indicating it is properly folded (Fig. 2A). Incubation of the N54S mutant with Poglut/Rumi and UDP-glucose or UDP-xylose showed a shift on HPLC, indicating it can be modified with both O-glucose and O-xylose (Fig. 2B). Using the radioactive assay, mN2 EGF16 was an excellent substrate for both Poglut and Poxylt activity of Poglut/Rumi, consistent with our prior mass spectral results (15). The FA9 N54S mutant showed similar Poglut activity compared with wild type but significantly higher Poxylt activity (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that the di-serine motif within the O-glucose consensus sequence, CXSSPC, significantly enhances Poxylt, but not Poglut, activity of Poglut/Rumi.

Variability in Efficiency of O-Glucose Site Modification May be Due to the Presence of Positively Charged Amino Acids Near the Modified Serine

Our recent site-mapping using mN1 also revealed the some O-glucose consensus sequences, such as that in EGF27, are underglucosylated compared with others, such as that in EGF12 (26). To investigate whether the difference in O-glucosylation of these two EGF repeats is due to differences in amino acid sequences within the individual EGF repeats, we expressed both in bacteria and tested them as substrates for Poglut/Rumi in vitro. To analyze purity, folding status, and acceptor activity of these EGF repeats, we incubated each EGF repeat with Poglut/Rumi in the absence or the presence of donor substrates, UDP-glucose, or UDP-xylose and applied the products to RP-HPLC. EGF12 showed a complete shift after incubation with UDP-glucose or UDP-xylose (Fig. 3A), and mass spectrometric analysis confirmed the addition of hexose (glucose) or pentose (xylose). EGF27 showed a complete shift after incubation with UDP-glucose and no significant shift after incubation with UDP-xylose, suggesting full modification by O-glucose but almost no modification with O-xylose (Fig. 3A). Kinetic radioactive assays showed that EGF12 is a much better substrate for the Poglut activity of Poglut/Rumi than EGF27, whereas neither was a good substrate for the Poxylt activity of Poglut/Rumi (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that a difference between the amino acid sequences of EGF12 and -27 can account for the difference in efficiency of O-glucosylation observed at these two sites (26).

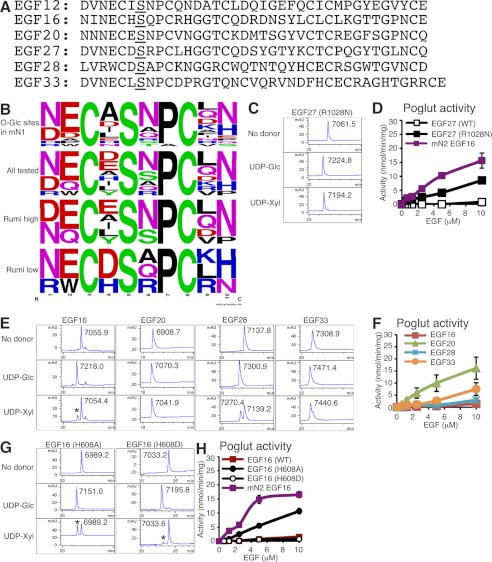

Comparison of the sequences of EGF12 and EGF27 reveals two charged residues within the O-glucose consensus of EGF27 not found in EGF12 (Fig. 4A). Comparison of all mapped O-glucose consensus sequences in mN1 reveals that the most common amino acids found in the −1 (relative to S) position (CXSXPC) are alanine or aspartate, whereas the most common found in the +1 position is asparagine (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, EGF27 contains an arginine in the +1 position, CDSRPC, which is somewhat rare. In fact, there is no other EGF repeat with a positively charged amino acid in the same position in mN1. To test whether this arginine influences the efficiency of modification by Poglut/Rumi, we mutated arginine to asparagine (R1028N), the most common amino acid at this position. Using the same methodology as above, we analyzed purity, folding status, and acceptor activity of these EGF repeats (Fig. 4, C and D). Kinetic radioactive assays revealed that the asparagine mutant enhanced Poglut activity relative to wild type (Fig. 4D). These results strongly suggest that the arginine in the +1 position reduces the efficiency of Poglut/Rumi modification and may account for the underglucosylation of this site in our previous site-mapping studies on mN1 produced in cells (26).

FIGURE 4.

Positively charged amino acids in the O-glucose consensus sequence reduce Poglut activity of Poglut/Rumi. A, shown is the amino acid sequence of EGF repeats 12, 16, 20, 27, 28, and 33 from mN1. The O-glucose consensus site is underlined in both. B, variability of amino acid sequences of EGF repeats is shown by WebLogo (31). Alignment is shown of the primary sequence of 10 amino acids containing the O-glucose consensus sequence of 17 EGF repeats from mN1 (top), EGF repeats (only wild type) tested in the present study (second), EGF repeats that were better substrates for Poglut/Rumi (Rumi high, third), and EGF repeats that were poorer substrates for Poglut/Rumi (Rumi low, bottom). EGF repeats that were modified more efficiently (over 5 nmol/min/mg) at 10 μm in the Poglut assays were defined as Rumi high. This group contained EGF12, EGF20, and EGF33 from mN1, EGF16 from mN2, FA9 EGF repeat, and FA7 EGF repeat (15). EGF repeats, which showed lower efficiency, were defined as Rumi low. This group contained EGF16, EGF27, and EGF28 from mN1. C, shown are RP-HPLC elution profiles of the reaction mixtures of mN1 EGF27 (R1028N) incubated with Poglut/Rumi in the absence of donor (top) or in the presence of UDP-Glc (middle) or UDP-Xyl (bottom) for 10 h. Masses of each species were determined. mAU, milli-absorbance units. D, shown is Rumi Poglut activity toward mN1 EGF27 (WT), R1028N mutant, or mN2 EGF16 in kinetic assays. The values indicate the mean ± S.E. E, RP-HPLC elution profiles of the reaction mixtures of mN1 EGF16, EGF20, EGF28, or EGF33 were incubated with Poglut/Rumi in the absence of donor (top) or in the presence of UDP-Glc (middle) or UDP-Xyl (bottom) for 10 h. Masses of each species were determined. The asterisk indicates O-xylosylated EGF16, whose mass was 7186.5. F, Rumi Poglut activity toward mN1 EGF16, EGF20, EGF28, or EGF33 in kinetic assays is shown. The values indicate the mean ± S.E. G, shown are RP-HPLC elution profiles of the reaction mixtures of the H608A and H608D mutants of mN1 EGF16 incubated with Poglut/Rumi in the absence of donor (top) or in the presence of UDP-Glc (middle) or UDP-Xyl (bottom) for 10 h. Asterisks indicate O-xylosylated H608A or H608D of EGF16 whose mass was 7120.6 or 7165.6, respectively. H, shown is Rumi Poglut (left) or Poxylt activity (right) toward the wild type, H608A, or H608D mutant of mN1 EGF16 and mN2 EGF16 in kinetic assays.

To investigate whether a positive charge in or around the modified serine in other contexts affects O-glucosylation by Poglut/Rumi, we compared the in vitro activity of several other bacterially expressed EGF repeats from mN1. EGF16 has a histidine in the −1 position and an arginine after the second conserved cysteine, CHSQPCR, and EGF28 has a positive charge immediately after the second conserved cysteine, CDSAPCK (Fig. 4A). As controls, we also generated EGF20 and -33, neither of which has positive charges in or around the modified serine (Fig. 4A). To analyze purity, folding status, and acceptor activity of these EGF repeats, we incubated them with Poglut/Rumi in the absence or the presence of donor substrates, UDP-glucose, or UDP-xylose and applied the products to RP-HPLC (Fig. 4E). All of the EGF repeats showed a complete shift after overnight incubation with Poglut/Rumi and UDP-glucose, and mass spectrometric analysis identified the addition of a hexose (Glc). These results show that the EGF repeats are properly folded and confirm they can be O-glucosylated in vitro. EGF16, EGF28, and EGF33 showed a partial shift after incubation with UDP-xylose, which suggested that Poxylt activity of Poglut/Rumi toward these EGF repeats was lower than that toward EGF20. Kinetic radioactive assays revealed that all EGF repeats tested showed dose-dependent Poglut activity (Fig. 4F), although with significantly different efficiencies. The EGF repeats without positively charged amino acids in or around the serine (EGF20, EGF33) were better substrates than those with positively charged amino acids (EGF16, EGF28). None of the EGF repeats were good substrates for Poxylt activity of Poglut/Rumi (data not shown).

To further examine the effect of positively charged residues in the consensus sequence, we prepared mutants of EGF16 to test as acceptor substrates in Poglut assays with Poglut/Rumi. In EGF16, the histidine in the −1 position was mutated to alanine (H608A) or aspartate (H608D), which are two of the most common amino acids at this position in mN1. Using the same methodology as above, we analyzed purity, folding status, and acceptor activity of these EGF repeats (Fig. 4, G and H). Kinetic radioactive assays revealed that all these mutants showed dose-dependent Poglut activity (Fig. 4H), although with significantly different efficiencies. The H608A mutant of EGF16 was a better substrate than the wild type or the H608D mutant of EGF16 (Fig. 4H). These results suggest that either a positively or negatively charged amino acid at this position in EGF16 reduces the efficiency of O-glucosylation by Poglut/Rumi.

Gxylt1 and Gxylt2 Can Modify Both O-Glucose and O-Xylose on EGF Repeats

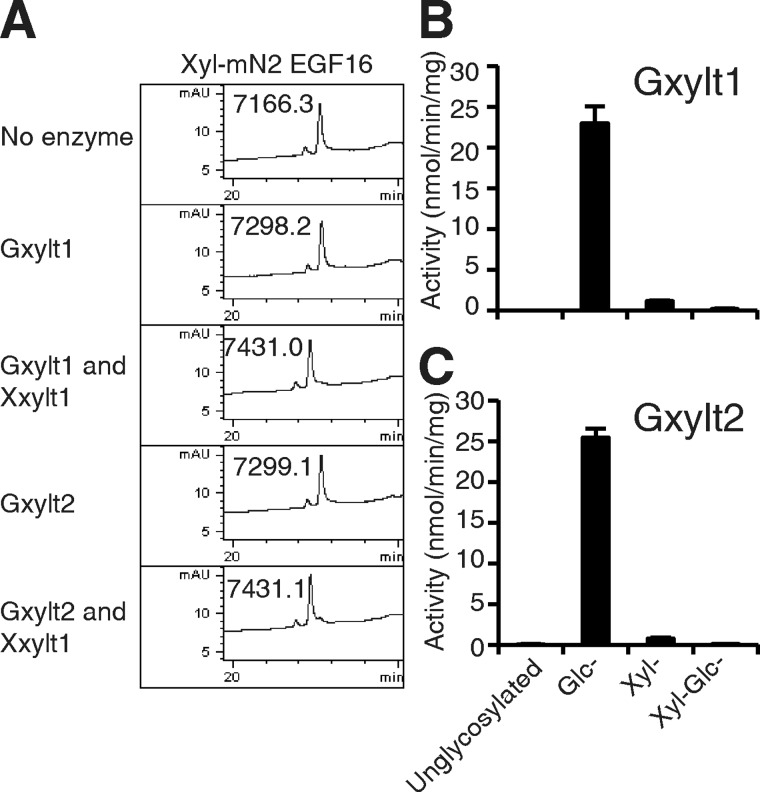

O-Glucose on the EGF repeats is elongated by two xyloses, resulting in the formation of O-glucose trisaccharide (Xylα1–3Xylα1–3Glcβ1-O-serine). Although O-glucose at all sites on mN1 appears to exist as the O-glucose trisaccharide (26), we found what appears to be an O-xylose trisaccharide (predicted structure Xylα1–3Xylα1–3Xylβ1-O-serine) on mN2 EGF16 that has a di-serine motif in the O-glucose consensus sequence (see Fig. 2) (15). The presence of this unusual structure raised the question of whether the enzymes responsible for the addition of the α3-linked xyloses to O-glucose can also extend O-xylose. We tested this by generating an O-xylose-modified form of mN2 EGF16 (Fig. 2) and examining whether purified Gxylt1 or Gxylt2 (supplemental Fig. S3 (18)) can modify it with xylose in vitro. After overnight incubation with UDP-xylose and Gxylt1 or Gxylt2, the products were analyzed by RP-HPLC and mass spectrometry (Fig. 5A). Both Gxylt1 and Gxylt2 caused a complete shift on the HPLC, suggesting stoichiometric transfer of xylose to O-xylose-modified mN2 EGF16. To examine whether Xxylt1 (19) is capable of adding xylose to di-xylosylated mN2 EGF16 (Xyl-Xyl-mN2 EGF16), Xylt1 was added to the reactions. Xxylt1 caused a further shift on RP-HPLC, and mass spectral analysis indicated the product contained three pentoses attached to mN2 EGF16 (Fig. 5A). These results demonstrate that both Gxylt1 and Gxylt2 can add xylose to O-xylose on an EGF repeat, and an O-xylose trisaccharide can be generated using Xxylt1. To examine whether the O-xylose-modified EGF repeat is as good an in vitro substrate as O-glucose-modified EGF repeat, we compared the O-glucose- and O-xylose-modified forms of mN2 EGF16 as substrates for Gxylt1 and Gxylt2 in a static in vitro assay (Fig. 5B). Both enzymes showed much higher activities toward O-glucosylated EGF repeat than O-xylosylated EGF repeat. These results suggest that although Gxylt1 and Gxylt2 are capable of adding xylose to O-xylose on an EGF repeat, they are much more efficient at modifying O-glucose.

FIGURE 5.

Gxylt1 or Gxylt2 and Xxylt1 can synthesize O-xylose trisaccharide on mN2 EGF16. A, mN2 EGF16 with O-xylose was incubated without enzyme or with Gxylt1, Gxylt1 and Xxylt1, Gxylt2, or Gxylt2 and Xxylt1 for 10 h in the presence of UDP-Xyl. Products were analyzed by RP-HPLC. mAU, milli-absorbance units. B, using mN2 EGF16 unglycosylated, modified with O-Glc, O-Xyl, or with Xyl-Glc disaccharide at 10 μm and 30 ng of each enzyme, the xylosyltransferase activities of Gxylt1 (B) or Gxylt2 (C) were analyzed. The values indicate the mean ± S.E.

Xylosyltransferases in the O-Glucose Trisaccharide Pathway Also Recognize Structural Features within Individual EGF Repeats

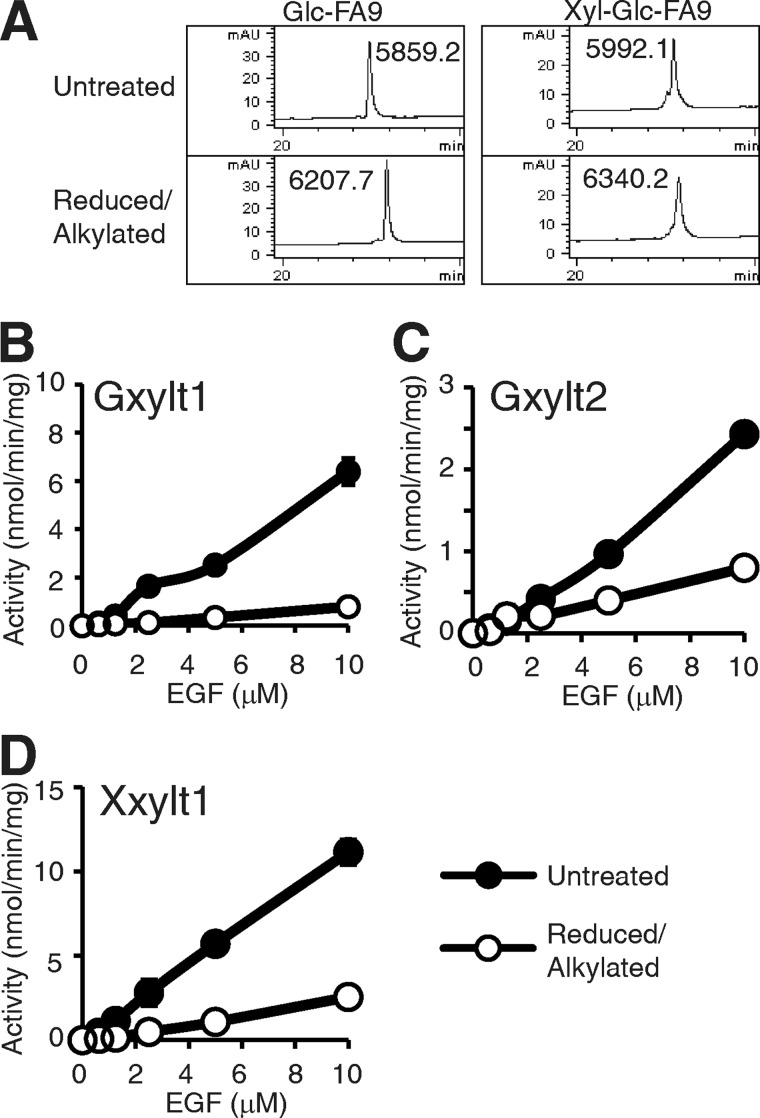

The fact that the glucoside xylosyltransferases, Gxylt1 and Gxylt2, can modify low molecular weight substrates in vitro raised the question of whether these enzymes primarily bind to the O-glucose, or do they also recognize the underlying protein structure (18)? To examine whether Gxylt1, Gxylt2, and Xxylt1 recognize underlying protein structure, we tested the activity of the enzymes using both folded and unfolded EGF repeats. FA9 EGF repeat modified with O-glucose or Xyl-Glc disaccharide was denatured by reduction and alkylation and purified by RP-HPLC as in Fig. 1 (Fig. 6A). Modification of reduced and alkylated FA9 EGF repeats with O-glucose or Xyl-Glc disaccharide was confirmed by mass spectral analysis. Gxylt1, Gxylt2, and Xxylt1 showed significantly higher activity toward folded FA9 EGF repeat modified with O-glucose or Xyl-Glc disaccharide than denatured ones in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6, B–D). Interestingly, all three enzymes showed low but detectable activity with the unfolded substrate, indicating that there is some recognition of the sugar alone, consistent with previous results using low molecular weight acceptor substrates (18, 19). These results indicate that each of these xylosyltransferases recognizes underlying protein structure in addition to the sugar.

FIGURE 6.

Gxylt1, Gxylt2, and Xxtlt1 prefer properly folded FA9 EGF repeat as substrate. A, RP-HPLC analysis of untreated or reduced and alkylated FA9 EGF repeat modified with O-Glc (left) or a Xyl-Glc disaccharide (right). The mass increase of Glc-FA9 or Xyl-Glc-FA9 after denaturing was 348.5 or 348.1, respectively, corresponding to carbamidomethylation of all 6 cysteines of the EGF repeats. mAU, milli-absorbance units. B and C, shown is the activity of Gxylt1 (B) and Gxylt2 (C) toward untreated or reduced and alkylated FA9 EGF repeat modified with O-Glc in kinetic assays. D, shown is activity of Xxylt1 toward untreated or reduced and alkylated FA9 EGF repeat modified with a Xyl-Glc disaccharide in kinetic assays. The values indicate the mean ± S.E.

DISCUSSION

Our previous O-glucose site mapping studies on mN1 (26) and mN2 (14, 15) produced in cells suggested that whereas O-glucose trisaccharide typically occurred at high stoichiometries at the predicted sites (CXSXPC), several interesting differences were found. Under-glucosylation was found at some sites (e.g. EGF27 of mN1, EGF16 of mN2), and a novel site was identified containing an alanine in place of the proline (EGF9 of mN1, CASAAC) (15, 26). In addition, we found that Poglut/Rumi could transfer O-xylose to a consensus site containing a di-serine as in EGF16 from mN2 (CYSSPC) (15). Here we have examined whether the amino acid sequences within individual EGF repeats can account for these differences by generating a number of EGF repeats in bacteria and testing them as substrates for Poglut/Rumi in vitro. Our results reveal that the all of the enzymes involved in O-glucose trisaccharide biosynthesis (Poglut/Rumi, Gxylt1, Gxylt2, Xxylt1) require or highly prefer a folded EGF repeat as substrate, suggesting that they all recognize the three-dimensional structure of the EGF repeat. In addition, amino acids in or around the consensus sequence influence the efficiency of modification of the EGF repeat. Finally, we demonstrated that Gxylt1, Gxylt2, and Xxylt1 are capable of synthesizing the O-xylose trisaccharide previously observed on EGF16 of mN2 isolated from cells (15).

Here we show that Poglut/Rumi can distinguish between folded and misfolded or unfolded isoforms of EGF repeats. Prior results showing that Pofut1 is localized to the ER, a protein folding compartment, coupled with the observation that it can differentiate between properly folded and misfolded conformations of EGF repeats, led to speculation that it may play a role in quality control (28, 32). Ofut1 has been proposed to function as a chaperone in Drosophila (independent of its O-fucosyltransferase activity) (33–35), although a similar function for Pofut1 in mammals is not clear (36). Poglut/Rumi is also localized to the ER (13, 15, 37), suggesting that like Pofut1, it could also play a role in quality control. Elimination of Poglut/Rumi in flies or mice does not result in decreased cell-surface expression of Notch, which would be expected if it were required for quality control of Notch folding (13, 14). Nonetheless, the fact that both Pofut1 and Poglut/Rumi can distinguish between folded and unfolded structures and are localized to the ER suggests that they may play some role, perhaps redundant, in quality control. Differences in cell-specific expression of chaperones and/or other quality control machinery may influence whether they are required for proper Notch folding in any specific context.

Our recent site-mapping study of O-glucose glycans on mN1 strongly suggested that the proline is not always necessary in the consensus sequence (26). In mN1, EGF9, which contains CASAAC, is modified with O-glucose glycans at high stoichiometry, whereas EGF35, which contains CGSLRC, is not. We tested whether alanine or arginine could substitute for proline in the context of another EGF repeat from human FA9 and found that the alanine, but not arginine, was tolerated, albeit poorly (Fig. 2). Thus, the presence of proline makes an EGF repeat a better substrate for Poglut/Rumi. Nonetheless, EGF9 is efficiently modified with O-glucose glycans by Polgut/Rumi in the context of full-length mN1 during protein biosynthesis, suggesting that alanine is better tolerated in the context of some EGF repeats than others. Interestingly, the analogous P55R mutation in human FA9 is known to cause hemophilia B (38, 39). O-Glucose trisaccharide is attached to the first EGF repeat of FA9 in vivo (40), and this EGF repeat is suggested to be involved in binding of FA9 to tissue factor as an early event during coagulation (41). We predict that patients with a P55R mutation in FA9 will lack the O-glucose trisaccharide, and this may contribute to Hemophilia B.

Our detailed analysis suggested that amino acids surrounding the O-glucose site of EGF repeats affect the efficiency of glycosylation by Poglut/Rumi. The role of the −1 position in the consensus was tested in the context of EGF16. The histidine residue of EGF16 was mutated to two most common amino acids in mN1. The H608A mutant of EGF16 was a better substrate for Poglut/Rumi, whereas the H608D mutant was as poor a substrate as wild type EGF16. Thus, either a negatively or positively charged amino acid is inhibitory in the −1 position. In contrast, both EGF20 from mN1 and FA9 EGF repeat, which are excellent substrates for Poglut/Rumi, have glutamate in the same position (see Rumi high in Fig. 4B). Thus, the charge state of the amino acid in that position may not be the only factor. Interestingly, both EGF27 and EGF28, which are poor substrates (Rumi low in Fig. 4B), have aspartate in the −1 position like the H608D mutant of EGF16. The role of the residue in the +1 position was analyzed in the context of EGF27. The mutation of this arginine to asparagine, the most common amino acid found at +1 in mN1, resulted in a significant increase in the efficiency of O-glucosylation by Poglut/Rumi. In our previous study we only detected underglucosylation at EGF27 in mN1 from the cultured cells (26). These results suggest that a positively charged residue in the +1 position reduces the efficiency of Poglut/Rumi modification. Therefore, it is likely that the nature of the amino acids on either side of the serine modified with O-glucose site influences the efficiency of modification by Poglut/Rumi.

Previously we observed an O-xylose trisaccharide on EGF16 from mN2, but we did not know if the enzymes involved in O-glucose trisaccharide biosynthesis were capable of also elongating O-xylose. Our results here suggest that Gxylt1 and Gxylt2 can elongate both O-glucose and O-xylose on an EGF repeat. Prior work with low molecular weight acceptors suggested that β-linked xylose did not serve as an acceptor substrate for these enzymes (18). Our results suggest that these enzymes can utilize β-linked xylose as an acceptor in the context of an EGF repeat, albeit poorly. Thus, the identified xylosyltransferases, Gxylt1, Gxylt2, and Xxylt1, are capable of forming the O-xylose trisaccharide we observed in cells (15). We proposed that the down-regulation of these enzymes (Gxylt1 and/or Gxylt2) could expose the β-linked O-xylose, which could in turn function as a primer for glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis (15). We are currently examining whether this happens in cells. The fact that Gxylt1, Gxylt2, and Xxylt1 strongly prefer folded EGF repeats, similar to what we previously showed for LFng (22), indicates that all of these enzymes recognize underlying protein structure. This may partially explain why elongation of O-glucose on EGF repeats is not elongated past a trisaccharide. Xxylt1, which might be expected to continue adding xylose residues, may be able to detect the distance between the acceptor site and the surface of the protein. Consistent with this idea, our previous work shows that Xxylt1 modifies Xylα1–3Glc much more efficiently than Xylα1–3Xylα1–3Glc or α-Xyl alone (19). Recognition of the β-linked glucose (which can be a xylose as described above) is, therefore, essential. The EGF repeats might be supportive as well. Furthermore, both Gxylt1 and Gxylt2 showed higher activities toward O-glucosylated mN2 EGF16 than those toward O-glucosylated FA9 (compare specific activities in Figs. 5 and 6), and Gxylt1 showed higher activity toward O-glucosylated FA9 EGF repeat than Gxylt2 (Fig. 6). These results suggest that efficiency of elongation of O-glucose with xylose can vary among EGF repeats. Preliminary data shows O-glucose monosaccharide at several EGF repeats from mN3.3 We predict that amino acid sequences within these EGF repeats may affect elongation by Gxylt1 or Gxylt2.

Here we have dissected the in vitro activities of four different glycosyltransferases with a variety of single EGF repeats. Our results suggest that both the three-dimensional structure of the EGF repeats as well as the amino acid sequences found within the EGF repeats have profound effects on the efficiency of modification at a particular site. Consistent with our previous site-mapping analysis on mN1 (26), EGF12 is a better substrate for Poglut/Rumi in vitro than EGF27. The fact that some EGF repeats in mN1 are better acceptor substrates than others suggests that those poorer EGF repeats may be more sensitive to change of expression level of Poglut/Rumi than the others in vivo. Small changes in the levels of Poglut/Rumi could have dramatic changes in stoichiometry of O-glucosylation at sites like EGF27 or EGF28. The fact that Poglut/Rumi levels are known to vary in different cells (14) suggests that this may be a mechanism for regulating Notch activity.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Bernadette Holdener and members in the Haltiwanger laboratory for helpful discussions and critical comments on this manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM61126 (to R. S. H.). This work was also supported by a research grant from Mizutani Foundation for Glycoscience (to H. T.) and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) for the Cluster of Excellence REBIRTH (from Regenerative Biology to Reconstructive Therapy) for the work in Hannover.

This article contains supplemental Tables 1 and 2 and Figs. 1–3.

E. Tan, G.-R. Hwang, and R. S. Haltiwanger, unpublished observation.

- Pofut

- protein O-fucosyltransferase

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- FA9

- factor 9

- LFng

- lunatic fringe

- mN1

- mouse Notch1

- mN2

- mouse Notch2

- mN3

- mouse Notch3

- Poglut

- protein O-glucosyltransferase

- Poxylt

- protein O-xylosyltransferase

- RP-HPLC

- reverse phase HPLC

- Xyl

- xylose

- Xxylt1

- xyloside xylosyltransferase

- Gxylt

- glucoside xylosyltransferase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kopan R., Ilagan M. X. (2009) The canonical Notch signaling pathway. Unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell 137, 216–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fortini M. E. (2009) Notch signaling. The core pathway and its posttranslational regulation. Dev. Cell 16, 633–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takeuchi H., Haltiwanger R. S. (2010) Role of glycosylation of Notch in development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 638–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rana N. A., Haltiwanger R. S. (2011) Fringe benefits. Functional and structural impacts of O-glycosylation on the extracellular domain of Notch receptors. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 21, 583–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moloney D. J., Panin V. M., Johnston S. H., Chen J., Shao L., Wilson R., Wang Y., Stanley P., Irvine K. D., Haltiwanger R. S., Vogt T. F. (2000) Fringe is a glycosyltransferase that modifies Notch. Nature 406, 369–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brückner K., Perez L., Clausen H., Cohen S. (2000) Glycosyltransferase activity of Fringe modulates Notch-δ interactions. Nature 406, 411–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang Y., Shao L., Shi S., Harris R. J., Spellman M. W., Stanley P., Haltiwanger R. S. (2001) Modification of epidermal growth factor-like repeats with O-fucose. Molecular cloning and expression of a novel GDP-fucose protein O-fucosyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 40338–40345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shi S., Stanley P. (2003) Protein O-fucosyltransferase I is an essential component of Notch signaling pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 5234–5239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okajima T., Irvine K. D. (2002) Regulation of notch signaling by O-linked fucose. Cell 111, 893–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matsuura A., Ito M., Sakaidani Y., Kondo T., Murakami K., Furukawa K., Nadano D., Matsuda T., Okajima T. (2008) O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine is present on the extracellular domain of notch receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35486–35495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sakaidani Y., Ichiyanagi N., Saito C., Nomura T., Ito M., Nishio Y., Nadano D., Matsuda T., Furukawa K., Okajima T. (2012) O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine modification of mammalian Notch receptors by an atypical O-GlcNAc transferase Eogt1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 419, 14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sakaidani Y., Nomura T., Matsuura A., Ito M., Suzuki E., Murakami K., Nadano D., Matsuda T., Furukawa K., Okajima T. (2011) O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine on extracellular protein domains mediates epithelial cell-matrix interactions. Nat. Commun. 2, 583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Acar M., Jafar-Nejad H., Takeuchi H., Rajan A., Ibrani D., Rana N. A., Pan H., Haltiwanger R. S., Bellen H. J. (2008) Rumi is a CAP10 domain glycosyltransferase that modifies Notch and is required for Notch signaling. Cell 132, 247–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fernandez-Valdivia R., Takeuchi H., Samarghandi A., Lopez M., Leonardi J., Haltiwanger R. S., Jafar-Nejad H. (2011) Regulation of mammalian Notch signaling and embryonic development by the protein O-glucosyltransferase Rumi. Development 138, 1925–1934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takeuchi H., Fernández-Valdivia R. C., Caswell D. S., Nita-Lazar A., Rana N. A., Garner T. P., Weldeghiorghis T. K., Macnaughtan M. A., Jafar-Nejad H., Haltiwanger R. S. (2011) Rumi functions as both a protein O-glucosyltransferase and a protein O-xylosyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 16600–16605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moloney D. J., Shair L. H., Lu F. M., Xia J., Locke R., Matta K. L., Haltiwanger R. S. (2000) Mammalian Notch1 is modified with two unusual forms of O-linked glycosylation found on epidermal growth factor-like modules. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 9604–9611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Whitworth G. E., Zandberg W. F., Clark T., Vocadlo D. J. (2010) Mammalian Notch is modified by d-Xyl-α1–3-d-Xyl-α1–3-d-Glc-β1-O-Ser. Implementation of a method to study O-glucosylation. Glycobiology 20, 287–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sethi M. K., Buettner F. F., Krylov V. B., Takeuchi H., Nifantiev N. E., Haltiwanger R. S., Gerardy-Schahn R., Bakker H. (2010) Identification of glycosyltransferase 8 family members as xylosyltransferases acting on O-glucosylated notch epidermal growth factor repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 1582–1586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sethi M. K., Buettner F. F., Ashikov A., Krylov V. B., Takeuchi H., Nifantiev N. E., Haltiwanger R. S., Gerardy-Schahn R., Bakker H. (2012) Molecular cloning of a xylosyltransferase that transfers the second xylose to O-glucosylated epidermal growth factor repeats of notch. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 2739–2748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Campbell I. D., Bork P. (1993) Epidermal growth factor-like modules. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 3, 385–392 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang Y., Spellman M. W. (1998) Purification and characterization of a GDP-fucose:polypeptide fucosyltransferase from Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 8112–8118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shao L., Moloney D. J., Haltiwanger R. (2003) Fringe modifies O-fucose on mouse Notch1 at epidermal growth factor-like repeats within the ligand-binding site and the Abruptex region. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7775–7782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luther K. B., Schindelin H., Haltiwanger R. S. (2009) Structural and mechanistic insights into lunatic fringe from a kinetic analysis of enzyme mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 3294–3305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rampal R., Li A. S., Moloney D. J., Georgiou S. A., Luther K. B., Nita-Lazar A., Haltiwanger R. S. (2005) Lunatic fringe, manic fringe, and radical fringe recognize similar specificity determinants in O-fucosylated epidermal growth factor-like repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42454–42463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harris R. J., Spellman M. W. (1993) O-Linked fucose and other post-translational modifications unique to EGF modules. Glycobiology 3, 219–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rana N. A., Nita-Lazar A., Takeuchi H., Kakuda S., Luther K. B., Haltiwanger R. S. (2011) O-Glucose trisaccharide is present at high but variable stoichiometry at multiple sites on mouse notch1. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 31623–31637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leonardi J., Fernandez-Valdivia R., Li Y. D., Simcox A. A., Jafar-Nejad H. (2011) Multiple O-glucosylation sites on Notch function as a buffer against temperature-dependent loss of signaling. Development 138, 3569–3578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Luo Y., Haltiwanger R. S. (2005) O-Fucosylation of Notch occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 11289–11294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Du J., Takeuchi H., Leonhard-Melief C., Shroyer K. R., Dlugosz M., Haltiwanger R. S., Holdener B. C. (2010) O-Fucosylation of thrombospondin type 1 repeats restricts epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) and maintains epiblast pluripotency during mouse gastrulation. Dev. Biol. 346, 25–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shao L., Luo Y., Moloney D. J., Haltiwanger R. (2002) O-Glycosylation of EGF repeats. Identification and initial characterization of a UDP-glucose:protein O-glucosyltransferase. Glycobiology 12, 763–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J. M., Brenner S. E. (2004) WebLogo. A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Luther K. B., Haltiwanger R. S. (2009) Role of unusual O-glycans in intercellular signaling. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41, 1011–1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Okajima T., Xu A., Lei L., Irvine K. D. (2005) Chaperone activity of protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 promotes notch receptor folding. Science 307, 1599–1603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sasamura T., Ishikawa H. O., Sasaki N., Higashi S., Kanai M., Nakao S., Ayukawa T., Aigaki T., Noda K., Miyoshi E., Taniguchi N., Matsuno K. (2007) The O-fucosyltransferase O-fut1 is an extracellular component that is essential for the constitutive endocytic trafficking of Notch in Drosophila. Development 134, 1347–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Okajima T., Reddy B., Matsuda T., Irvine K. D. (2008) Contributions of chaperone and glycosyltransferase activities of O-fucosyltransferase 1 to Notch signaling. BMC Biol. 6, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stahl M., Uemura K., Ge C., Shi S., Tashima Y., Stanley P. (2008) Roles of Pofut1 and O-fucose in mammalian Notch signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13638–13651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Teng Y., Liu Q., Ma J., Liu F., Han Z., Wang Y., Wang W. (2006) Cloning, expression, and characterization of a novel human CAP10-like gene hCLP46 from CD34(+) stem/progenitor cells. Gene 371, 7–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Giannelli F., Green P. M., High K. A., Sommer S., Poon M. C., Ludwig M., Schwaab R., Reitsma P. H., Goossens M., Yoshioka A., (1993) Hemophilia B. Database of point mutations and short additions and deletions. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 3075–3087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Montejo J. M., Magallón M., Tizzano E., Solera J. (1999) Identification of twenty-one new mutations in the factor IX gene by SSCP analysis. Hum. Mutat. 13, 160–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hase S., Nishimura H., Kawabata S., Iwanaga S., Ikenaka T. (1990) The structure of (xylose)2glucose-O-serine 53 found in the first epidermal growth factor-like domain of bovine blood clotting factor IX. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 1858–1861 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhong D., Bajaj M. S., Schmidt A. E., Bajaj S. P. (2002) The N-terminal epidermal growth factor-like domain in factor IX and factor X represents an important recognition motif for binding to tissue factor. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3622–3631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]