Background: SLP-76 is negatively regulated by Ser-376 phosphorylation through unclear mechanisms.

Results: Ser-376 phosphorylation induces SLP-76 ubiquitination at Lys-30, leading to degradation of activated SLP-76 and subsequent attenuation of T cell receptor (TCR) signaling.

Conclusion: Ser-376 phosphorylation attenuates TCR signaling by inducing ubiquitination and degradation of activated SLP-76.

Significance: This is the first report of SLP-76 ubiquitination initiated by Ser-376 phosphorylation.

Keywords: Adaptor Proteins, Serine/Threonine Protein Kinase, Signal Transduction, T Cell, Ubiquitination, SLP-76

Abstract

SLP-76 (SH2 domain-containing leukocyte protein of 76 kDa) is an adaptor protein that is essential for T cell development and T cell receptor (TCR) signaling activation. Previous studies have identified an important negative feedback regulation of SLP-76 by HPK1 (hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1; MAP4K1)-induced Ser-376 phosphorylation. Ser-376 phosphorylation of SLP-76 mediates 14-3-3 binding, resulting in the attenuation of SLP-76 activation and downstream signaling; however, the underlying mechanism of this action remains unknown. Here, we report that phosphorylated SLP-76 is ubiquitinated and targeted for proteasomal degradation during TCR signaling. SLP-76 ubiquitination is mediated by Ser-376 phosphorylation. Furthermore, Lys-30 is identified as a ubiquitination site of SLP-76. Loss of Lys-30 ubiquitination of SLP-76 results in enhanced anti-CD3 antibody-induced ERK and JNK activation. These results reveal a novel regulation mechanism of SLP-76 by ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of activated SLP-76, which is mediated by Ser-376 phosphorylation, leading to down-regulation of TCR signaling.

Introduction

SLP-76 (SH2 domain-containing leukocyte protein of 76 kDa) is an adaptor protein that is required for linking proximal and distal T cell receptor (TCR)3 signaling (1). The critical roles of SLP-76 in both thymocyte development and peripheral T cell activation have been well documented by numerous studies using the human Jurkat leukemic T cell line and mouse genetic models (1). The phosphorylation of multiple tyrosine residues (e.g. Tyr-113, Tyr-128, and Tyr-145) at the N-terminal region of SLP-76 mediates the interactions of SLP-76 with VAV, NCK, and ITK, leading to an increase in phospholipase Cγ1 activation, calcium flux, and NFAT transcriptional activity (1, 2). The central proline-rich domain of SLP-76 binds to phospholipase Cγ1 and GADS, facilitating phospholipase Cγ1 phosphorylation and T cell activation (1). The SH2 (Src homology 2) domain in the C terminus of SLP-76 binds to ADAP and HPK1 (hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1; also named MAP4K1 for mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 1) (1). SLP-76/ADAP interaction is required for TCR-induced “inside-out” signaling for LFA-1 activation in T cells (1), whereas the binding of SLP-76 with HPK1 leads to HPK1 activation and subsequent attenuation of SLP-76 activation and TCR signaling (3).

HPK1 is a hematopoietic cell-restricted Ste20-like serine/threonine kinase that activates the JNK kinase cascade (4–8). Besides HPK1, there are five other Ste20-like serine/threonine kinases (GCK/MAP4K2, GLK/MAP4K3, HGK/MAP4K4, GCKR/MAP4K5, and MINK/MAP4K6) that also activate the JNK pathway (4, 8–13). Thus, these six Ste20-like kinases are designated as the MAP4K subfamily (8). HPK1 is associated with many adaptor proteins, suggesting that it is involved in multiple signaling pathways (14–19). The kinase activity of HPK1 is regulated by several mechanisms. During TCR signaling, HPK1 is activated by its Tyr-379 phosphorylation-mediated interaction with the SH2 domain of SLP-76 (17, 20). In addition, protein phosphatase 4 positively regulates HPK1 kinase activation via inhibiting HPK1 ubiquitination and degradation during TCR signaling (21). During cell apoptosis, HPK1 is cleaved by caspase-3 at DDVD (amino acids 382–385), and the resulting N-terminal kinase domain fragment shows enhanced kinase activity (22). HPK1-deficient mice show enhanced T cell activation and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, indicating a negative role of HPK1 in controlling TCR signaling (3). The negative role of HPK1 is mediated by induction of serine phosphorylation of SLP-76 and subsequent SLP-76/14-3-3 interaction (3). Di Bartolo et al. (23) further identified Ser-376 of SLP-76 as an HPK1-induced phosphorylation site. To date, the underlying mechanism for attenuation of SLP-76 function by Ser-376 phosphorylation and 14-3-3 binding remains unknown. Here, we show that TCR signaling induces SLP-76 ubiquitination, which targets phosphorylated SLP-76 for proteasomal degradation. SLP-76 ubiquitination is mediated by HPK1-induced Ser-376 phosphorylation. We further identify Lys-30 as an SLP-76 ubiquitination site; loss of Lys-30 ubiquitination of SLP-76 stabilizes phosphorylated SLP-76 and subsequently enhances ERK activation during TCR signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6) WT and HPK1-deficient mice were bred in a specific pathogen-free environment in the Transgenic Mouse Facility at Baylor College of Medicine. All animal experiments were performed according to institutional guidelines and regulations.

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against phosphorylated Ser-376 of an SLP-76 peptide (CFPQSApS376LPPY) were generated and purified by Eurogentec Inc. Anti-phospho-ERK (Thr-202/Tyr-204), anti-phospho-p38 (Thr-180/Tyr-182), anti-phospho-JNK (Thr-183/Tyr-185), anti-phospho-IKKα (Ser-180)/IKKβ (Ser-181), anti-ERK, anti-p38, anti-IKKβ, anti-HA (6E2), and anti-ubiquitin (P4D1) were from Cell Signaling. Anti-SLP-76, anti-HPK1 (N-19), anti-JNK1 (F-3), and anti-GST (B-14) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-FLAG (M2) monoclonal antibody was from Sigma Aldrich. Anti-human 14-3-3 (θ/τ) monoclonal antibody was from BIOSOURCE. A monoclonal antibody that specifically recognizes polyubiquitin chains joined through Lys-48 (anti-ubiquitin, Lys-48-specific; clone Apu2) has been described previously and was purchased from Millipore (24).

T Cell Stimulation

Human T cell lines (Jurkat, Jurkat TAg, and SLP-76-deficient J14 cells) were stimulated by 5 μg/ml anti-human CD3 (OKT3) antibody. Murine splenic T cells were stimulated with 10 μg/ml biotin-labeled anti-CD3ζ (145-2c11) antibody, followed by TCR cross-linking using 20 μg/ml streptavidin. The stimulation was immediately stopped by cold spin, and the cells were lysed using lysis buffer for 30 min on ice.

Plasmids and Mutagenesis

FLAG-SLP-76 plasmid was provided by G. A. Koretzky (University of Pennsylvania). Human SLP-76 tagged with two copies of FLAG at the N terminus was subcloned into the pIRES2-AcGFP1 vector (Clontech). SLP-76 mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of serine-to-alanine or lysine-to-arginine. All SLP-76 mutants were verified by DNA sequencing.

Cell Transfections

Jurkat TAg and J14 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium plus 10% FBS and transfected using the Neon transfection system (Invitrogen) with a setting of 1400 V, 30 ms, and one pulse.

GST Pulldown Assays, Co-immunoprecipitations, and Western Blotting

These assays were performed as described in our previous publication (3). GST-14-3-3 isoform plasmids were provided by C. Walker (University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center), W.-C. Lin (University of Alabama at Birmingham), and Y. Gotoh (University of Tokyo). For GST pulldown assay, GST-14-3-3 recombinant proteins were incubated with 400–800 μg of cell lysates at 4 °C for 2 h and then immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads for 45 min at 4 °C. Beads were washed three times with cell lysis buffer and then boiled in 2× SDS loading buffer for 5 min. For co-immunoprecipitation, 2–5 μg of antibody and 400–600 μg of cell lysates were mixed and rotated on a rocker at 4 °C for 2 h, followed by the addition of 30 μl of Protein A/G Plus-conjugated agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and incubation for 1 h. Beads were washed four times with cell lysis buffer and boiled in 20 μl of 2× SDS loading buffer. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF filter, and subjected to Western blot analyses for the detection of the molecules of interest.

Protein Denaturation and Sequential Immunoprecipitation

To determine SLP-76 ubiquitination, HEK293T or Jurkat TAg cells were transfected with FLAG-SLP-76 and HA-ubiquitin. The cells were pretreated with MG132 for 0–4 h. Jurkat TAg cells were further stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody. The cells were lysed and subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG antibody (first immunoprecipitation). Two-thirds of the anti-FLAG immunocomplex was boiled in the presence of 1% SDS, diluted 10-fold to reduce SDS concentration, and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody (second immunoprecipitation). The ubiquitination of SLP-76 was determined by Western blotting using anti-HA antibody.

Cycloheximide Chase Assay

Murine splenic T cells and the transfected J14 cells were stimulated with 10 and 5 μg/ml anti-CD3 antibody, respectively, for 15 min. The cells were then treated with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide for 0–120 min. The cell lysates were collected, and the levels of the proteins of interest were analyzed by Western blotting. Densitometry analysis of the Western blot results was performed using Gel-Pro software (Media Cybernetics). Simple linear regression for the relative actin-normalized SLP-76 (phosphorylated or total) protein band intensity versus time was employed to determine the degradation kinetics of SLP-76 (phosphorylated or total) proteins. According to the linear regression analysis, a y-value of 0.5 (indicating 50% relative expression) maps to the time corresponding to the protein half-life.

LC-MS/MS

LC-MS/MS was performed at the Core Facilities for Proteomics Research (Institute of Biological Chemistry, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan). HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-SLP-76 and HA-ubiquitin and then incubated with 25 μm MG132 for 3 h. FLAG-SLP-76 proteins were isolated from the transfected HEK293T cells using anti-FLAG antibody-agarose gel and resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by sliver staining. Specific protein bands from silver-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels were excised, destained, and digested with trypsin. The resulting peptide mixtures were loaded onto a nanoACQUITY UPLC BEH130 column (75 μm × 250 mm) packed with C18 resin (Waters) and separated using a segmented gradient, followed by LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometry (Thermo Scientific). All MS and MS/MS raw data were processed by Raw2MSM and searched against a target protein sequence database using the Mascot Daemon 2.2 server.

RESULTS

SLP-76 Ser-376 Phosphorylation Mediates the Interaction of SLP-76 with All 14-3-3 Isoforms and Is Induced by HPK1 in Primary T Cells upon TCR Signaling

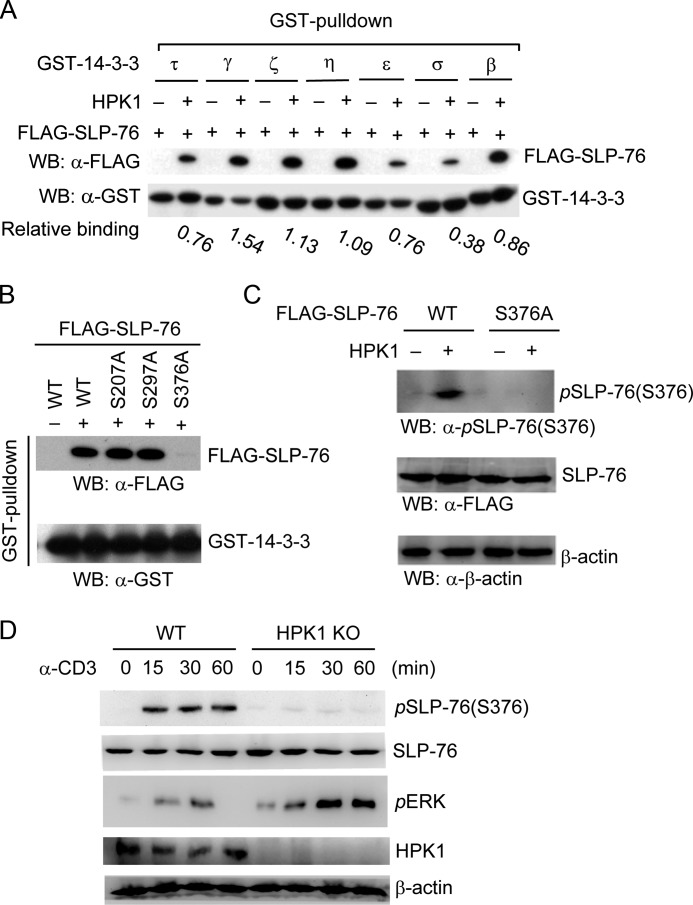

Previously, we identified that HPK1 induces SLP-76/14-3-3τ binding in T cells upon anti-CD3 stimulation (3). SLP-76 also binds to 14-3-3ζ and 14-3-3ϵ in an HPK1-dependent manner during TCR signaling (23). There are four additional isoforms of mammalian 14-3-3 proteins ( γ, σ, η, and β) that are also expressed in T cells. The relative binding of SLP-76 to other 14-3-3 isoforms remains unclear. As shown in Fig. 1A, SLP-76 interacted with all seven isoforms of 14-3-3 in the presence of HPK1, with the relative binding order of γ > η > ϵ > β > τ and ζ > δ. To identify the 14-3-3-binding site on SLP-76, we mutated the potential 14-3-3-binding motifs (RSXp(S/T)XP and RX(Y/F)Xp(S/T)XP, where p(S/T) represents phosphorylated serine/threonine and X represents any amino acid) on SLP-76. Only the S376A mutation abolished HPK1-dependent SLP-76/14-3-3 interaction (Fig. 1B); this result was consistent with a previous report (23). HPK1-induced SLP-76 Ser-376 phosphorylation in murine primary T cells has never been demonstrated. We generated a rabbit polyclonal antibody against phospho-Ser-376 of SLP-76. As shown in Fig. 1C, this antibody detected only phosphorylated WT SLP-76, but not the S376A mutant, in HEK293T cells cotransfected with HPK1, demonstrating the specificity of this phospho-specific antibody. We thus used this anti-phospho-Ser-376 antibody to study SLP-76 phosphorylation in murine splenic T cells. SLP-76 Ser-376 phosphorylation was indeed detected in WT cells, but not in HPK1-deficient splenic T cells, upon anti-CD3 stimulation (Fig. 1D). HPK1-deficient T cells showed enhanced ERK activation (Fig. 1D) as described previously (3).

FIGURE 1.

HPK1-induced SLP-76 Ser-376 phosphorylation and 14-3-3 binding. A, interaction of SLP-76 with different 14-3-3 isoforms in the presence of HPK1. FLAG-SLP-76 was transfected into HEK293T cells with HPK1. The interaction of SLP-76 with 14-3-3 isoforms was detected by GST pulldown assays using GST-14-3-3 proteins. The relative binding of SLP-76 to 14-3-3 isoforms was calculated by the amount of GST-14-3-3-bound SLP-76 divided by the amount of GST-14-3-3 input as determined by densitometry analyses. WB, Western blot. B, the S376A mutation abolishes HPK1-dependent SLP-76/14-3-3 interaction in vitro. The serine residues located in the potential 14-3-3-binding sites (e.g. Ser-207, Ser-297, and Ser-376) within SLP-76 were individually mutated to alanine. WT SLP-76 and mutants were transfected into HEK293T cells with HPK1. The cell lysates were subjected to GST-14-3-3τ pulldown assays, followed by Western blotting with anti-FLAG antibody. GST-14-3-3 input was detected by Western blotting with anti-GST antibody. C, Ser-376 of SLP-76 is phosphorylated by HPK1 in HEK293T cells. HPK1 was cotransfected with either FLAG-SLP-76 (WT or S376A mutant) into HEK293T cells. The cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting with anti-phospho-SLP-76 (Ser-376) antibody. The protein levels of WT SLP-76 and the S376A mutant were detected by anti-FLAG antibody. D, induction of SLP-76 Ser-376 phosphorylation in WT (but not HPK1-deficient) T cells during TCR signaling. Splenic T cells were isolated from WT and HPK1-deficient mice and stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody for the indicated time periods, followed by Western blotting with anti-phospho-SLP-76 (Ser-376) antibody. ERK phosphorylation was determined as a control. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. KO, knock-out.

SLP-76 Is Ubiquitinated and Targeted for Proteasomal Degradation in T Cells during TCR Signaling

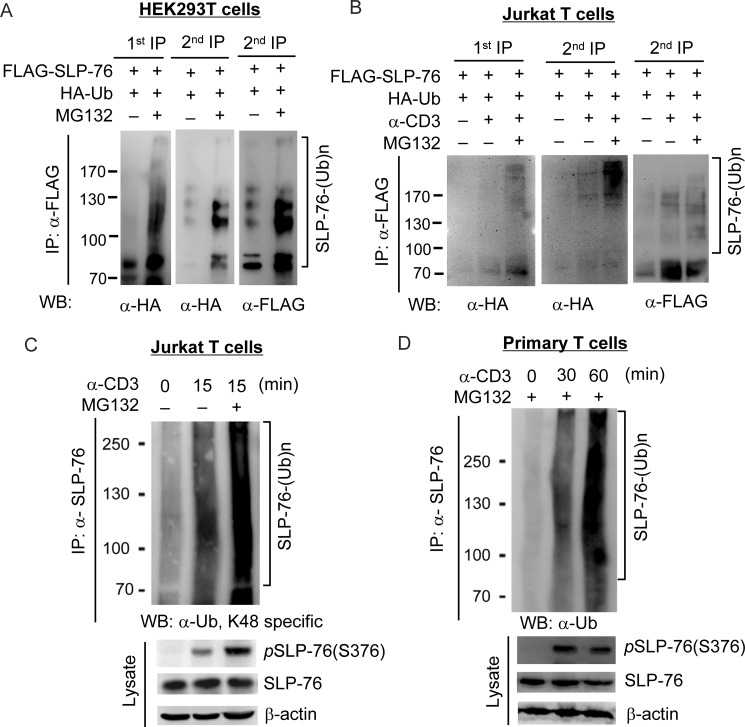

An important question remaining to be addressed is how SLP-76 Ser-376 phosphorylation and subsequent 14-3-3 binding attenuate TCR signaling. Binding of 14-3-3 can induce ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of its binding proteins, such as MDMX (25). Thus, we examined the possibility that 14-3-3 binding may induce SLP-76 ubiquitination. As SLP-76 ubiquitination has not been reported previously, we first studied whether SLP-76 can be ubiquitinated. Anti-SLP-76 immunocomplex contained ubiquitinated species in HEK293T cells that overexpressed FLAG-SLP-76 and HA-ubiquitin in the presence of MG132, a proteasomal inhibitor (Fig. 2A, left panel). Furthermore, sequential immunoprecipitation of denatured anti-SLP-76 immunocomplex still showed ubiquitinated SLP-76, which was detected by both anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies (Fig. 2A, right panel). These data indicate that SLP-76 itself can be ubiquitinated. Next, we studied whether SLP-76 is ubiquitinated in T cells upon anti-CD3 stimulation. Jurkat T cells were transfected with FLAG-SLP-76 and HA-ubiquitin, followed by MG132 treatment and anti-CD3 stimulation. To remove the ubiquitination signals from SLP-76-associated proteins, sequential immunoprecipitation of SLP-76 was performed. As shown in Fig. 2B, SLP-76 ubiquitination was induced in Jurkat T cells upon anti-CD3 stimulation and was further enhanced by the proteasomal inhibitor MG132, suggesting that ubiquitinated SLP-76 is targeted for proteasomal degradation. Furthermore, ubiquitination of endogenous SLP-76 isolated from Jurkat T cells and murine primary T cells upon anti-CD3 stimulation and MG132 treatment was also detectible using the antibody recognizing ubiquitin linked at Lys-48 (Fig. 2, C and D). To further verify the effect of ubiquitination on SLP-76 protein levels, Jurkat T cells were pretreated with MG132, followed by anti-CD3 stimulation. Interestingly, the levels of Ser-376-phosphorylated and Tyr-145-phosphorylated SLP-76 proteins were increased by MG132 treatment in Jurkat T cells, whereas the increase in SLP-76 levels was less discernible upon MG132 treatment (Fig. 3A). Similar results were observed in murine primary T cells as well (Fig. 3B), suggesting that ubiquitination specifically targets phosphorylated SLP-76 for proteasomal degradation. To further confirm the degradation of SLP-76 during TCR signaling, we stimulated primary T cells with anti-CD3 antibody for 15 min, followed by cycloheximide treatment in a time course and Western blotting of the cell lysates for measuring the half-life of the total and phosphorylated SLP-76 proteins. The levels of both SLP-76 and Ser-376-phosphorylated SLP-76 proteins were decreased with time, whereas Ser-376-phosphorylated SLP-76 showed a shorter half-life (66 versus 133 min) (Fig. 3C). These data further support that Ser-376-phosphorylated SLP-76 is targeted for degradation.

FIGURE 2.

SLP-76 is ubiquitinated during TCR signaling. Sequential immunoprecipitation was used to detect SLP-76 ubiquitination in HEK293T cells (A) and anti-CD3 antibody-stimulated Jurkat T cells (B). FLAG-tagged SLP-76 was transfected into HEK293T or Jurkat TAg cells with HA-ubiquitin (Ub). The cells were treated with MG132 for 0–4 h, and Jurkat T cells were then stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody for 15 min. FLAG-SLP-76 was immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody (1st IP); two-thirds of the first anti-FLAG immunocomplex was denatured, followed by a second round of immunoprecipitation (2nd IP) with anti-FLAG antibody. The ubiquitination of the first and second anti-FLAG immunocomplexes was detected by Western blotting (WB) with anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies. SLP-76 is ubiquitinated in Jurkat T cells (C) and primary T cells (D) upon anti-CD3 stimulation. Cells were pretreated with or without MG132, stimulated by anti-CD3 antibody, and subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-SLP-76 antibody. SLP-76 ubiquitination was detected by anti-ubiquitin (Lys-48) and anti-SLP-76 antibodies.

FIGURE 3.

SLP-76 is targeted for proteasomal degradation in TCR signaling. A and B, MG132 increases the levels of SLP-76 phosphorylation in Jurkat T cells and murine primary T cells upon anti-CD3 stimulation. Human Jurkat T cells (A) and murine splenic T cells (B) were pretreated with MG132 or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) 4 h and then stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody for the indicated time periods. The levels of phosphorylated and total SLP-76 proteins were detected by Western blotting. The relative phosphorylation levels were determined by densitometry analysis. C, left panel, measurement of SLP-76 degradation by cycloheximide chase assay. Murine splenic T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody for 15 min and then treated with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) for 0–120 min. The cell lysates were collected, and the levels of the indicated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Right panel, simple linear regression analysis of the relative SLP-76 (Ser-376-phosphorylated and total) protein levels in the left panel at different times of cycloheximide treatment. The relative SLP-76 protein levels were quantified and normalized to β-actin protein levels. The equation of the protein degradation rate for SLP-76 in primary T cells is as follows: Y = −0.003412*X + 0.9529 (R2 = 0.4505, p = 0.0169). The equation of the protein degradation rate for Ser-376-phosphorylated SLP-76 in primary T cells is as follows: Y = −0.007396*X + 0.9881 (R2 = 0.7361, p = 0.0004).

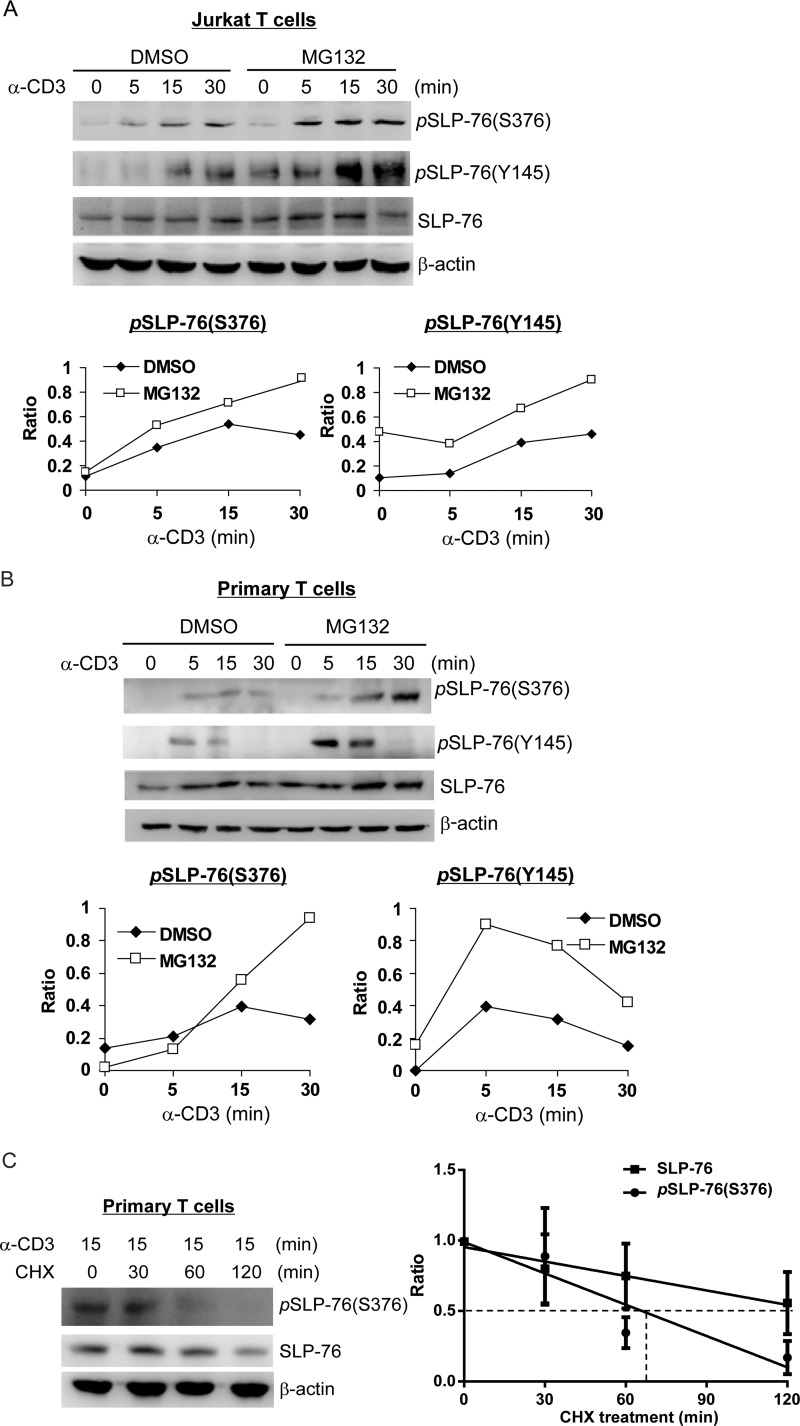

Ser-376 Phosphorylation Induces SLP-76 Ubiquitination

To determine whether Ser-376 phosphorylation regulates SLP-76 ubiquitination, we transfected FLAG-SLP-76 (WT or S376A mutant) into Jurkat T cells, followed by MG132 treatment and anti-CD3 stimulation. WT SLP-76, but not the S376A mutant, showed significant Lys-48-linked ubiquitination upon anti-CD3 stimulation and MG132 treatment (Fig. 4A). Similarly, endogenous SLP-76 was significantly ubiquitinated in WT splenic T cells, but not in HPK1-deficient T cells, upon anti-CD3 stimulation in the presence of MG132 treatment (Fig. 4B). These data indicate that HPK1-induced Ser-376 phosphorylation mediates Lys-48-linked ubiquitination of SLP-76 during TCR signaling. A direct interaction between 14-3-3 and the E3 ubiquitin ligase c-Cbl is induced in human Jurkat T cells upon anti-CD3 stimulation (26). c-Cbl negatively regulates TCR signaling in thymocytes (27). Thus, we explored the possibility that Ser-376 phosphorylation-mediated 14-3-3 binding may recruit the E3 ligase c-Cbl, which may induce SLP-76 ubiquitination. Although anti-CD3 antibody induced the interaction of SLP-76 with c-Cbl, this interaction was unaffected in HPK1-deficient T cells (Fig. 4C), suggesting that an E3 ligase other than c-Cbl is responsible for HPK1-mediated SLP-76 ubiquitination in T cells. Nonetheless, the search for the elusive E3 ligase for SLP-76 ubiquitination is not the focus of this study.

FIGURE 4.

HPK1 induces SLP-76 ubiquitination during TCR signaling. A, SLP-76 Ser-376 phosphorylation mediates SLP-76 ubiquitination during TCR signaling. Jurkat TAg cells were transfected with FLAG-SLP-76 (WT or S376A mutant), pretreated with or without MG132 for 3 h, and stimulated by anti-CD3 antibody for 15 min. SLP-76 was immunoprecipitated (IP) using anti-FLAG antibody, followed by Western blotting (WB) with anti-ubiquitin (α-Ub; Lys-48) antibody. B, HPK1 deficiency suppresses SLP-76 ubiquitination in primary murine T cells upon anti-CD3 stimulation. Murine splenic T cells from WT and HPK1-deficient mice were pretreated with MG132 for 4 h and then stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody for 30 min. SLP-76 was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates using anti-SLP-76 antibody, followed by Western blotting with anti-ubiquitin (Lys-48) antibody. SLP-76 and β-actin in the lysates were detected as controls. KO, knock-out. C, HPK1 deficiency does not affect c-Cbl/SLP-76 interaction in T cells upon TCR signaling. SLP-76 was co-immunoprecipitated from unstimulated and anti-CD3 antibody-stimulated T cells using anti-SLP-76 antibody, followed by Western blotting with anti-c-Cbl antibody. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

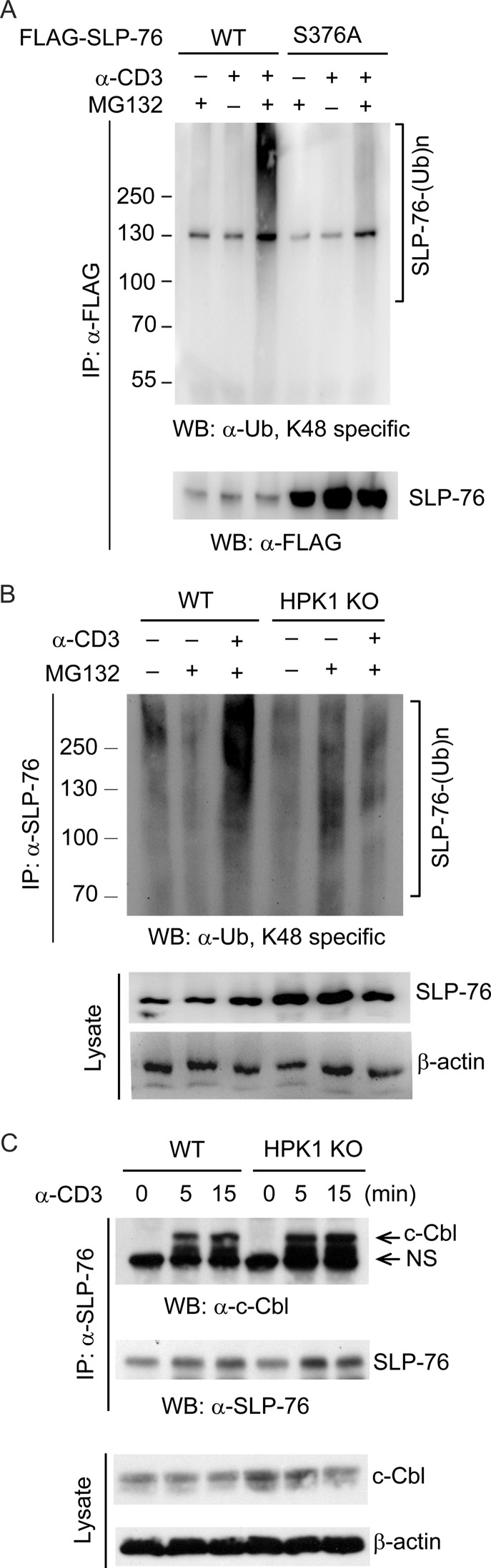

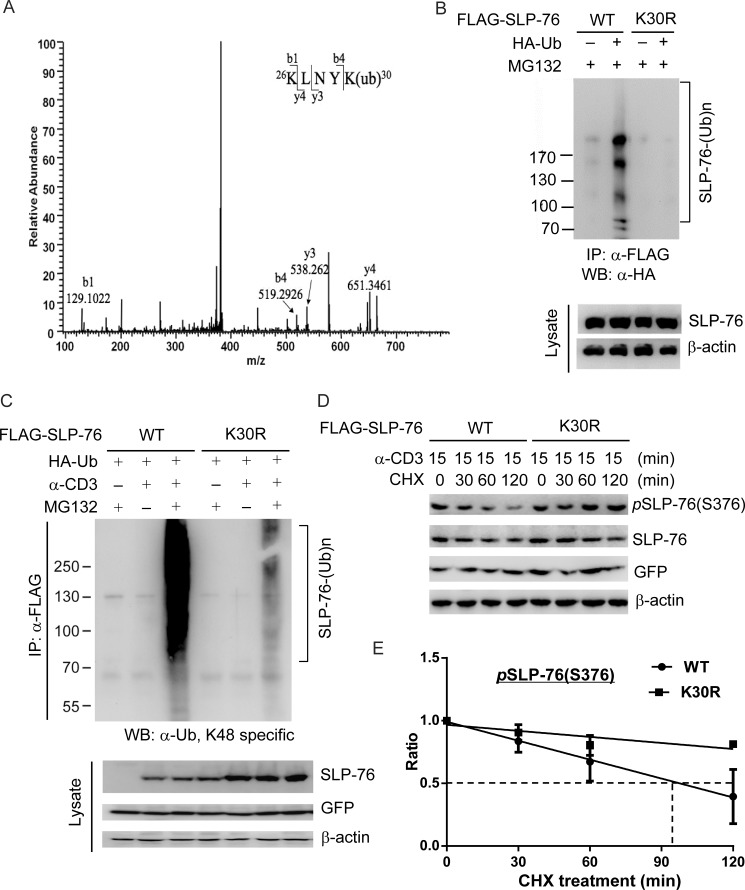

Lys-30 Is an SLP-76 Ubiquitination Site That Attenuates TCR Signaling

To characterize the function of SLP-76 ubiquitination, we sought to identify SLP-76 ubiquitination site(s) using mass spectrometry. Lys-30 was identified as a ubiquitination site of SLP-76 in HEK293T cells (Fig. 5A). To verify the identified SLP-76 ubiquitination site, we generated an SLP-76 mutant by the substitution of lysine with arginine at amino acid 30. Ubiquitination was undetectable in the FLAG-tagged SLP-76 K30R mutant coexpressed with HA-ubiquitin in HEK293T cells (Fig. 5B). To further verify that Lys-30 is a physiological SLP-76 ubiquitination site induced by TCR signaling, we transfected WT SLP-76 and the K30R mutant into Jurkat T cells, followed by anti-CD3 stimulation and MG132 treatment. WT SLP-76 showed significant ubiquitination in anti-CD3 antibody-stimulated Jurkat T cells, whereas the K30R mutant showed dramatically diminished ubiquitination (Fig. 5C). These data indicate that Lys-30 ubiquitination of SLP-76 is induced in T cells upon TCR signaling. To further study whether loss of Lys-30 ubiquitination renders resistance of SLP-76 to protein degradation, we measured the half-life of the SLP-76 K30R mutant by transfecting WT SLP-76 and the K30R mutant into SLP-76-deficient Jurkat T cells (J14 line), followed by anti-CD3 stimulation for 15 min and cycloheximide chase assay. Compared with WT SLP-76, the half-life of the Ser-376-phosphorylated SLP-76 K30R mutant was much longer (290 versus 98 min) (Fig. 5, D and E). Consistently, the total SLP-76 K30R mutant protein levels were also increased compared with WT SLP-76 (Fig. 5, D and E).

FIGURE 5.

Lys-30 is an SLP-76 ubiquitination site. A, mass spectrometry spectra of a tryptic peptide of SLP-76 containing the diglycine fragment of ubiquitin attached to Lys-30. FLAG-SLP-76 and HA-ubiquitin were transiently transfected into HEK293T cells, followed by MG132 treatment; the transfected FLAG-SLP-76 proteins were isolated from these cells for LC-MS/MS analysis. B, K30R mutation reduces SLP-76 ubiquitination in HEK293T cells. FLAG-SLP-76 (WT or K30R mutant) was transfected into HEK293T cells with HA-ubiquitin (Ub). Ubiquitination of SLP-76 was determined by sequential anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation (IP), followed by Western blotting (WB) with anti-HA antibody. C, K30R mutation reduces SLP-76 ubiquitination in Jurkat T cells upon anti-CD3 stimulation. FLAG-SLP-76 (WT or K30R mutant) was transfected into Jurkat TAg cells with HA-ubiquitin. The transfected cells were treated with MG132 for 3 h and then stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody for 15 min. The FLAG-SLP-76 proteins were immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted with anti-ubiquitin (Lys-48) antibody. D, measurement of the degradation of Ser-376-phosphorylated SLP-76 (WT and K30R mutant) by cycloheximide chase assay. J14 cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody for 15 min and then treated with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) for 0–120 min. The cell lysates were collected, and the levels of the indicated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. Data are representative of three independent experiments. E, simple linear regression analysis of the relative Ser-376-phosphorylated SLP-76 protein levels in D at different times of cycloheximide treatment. The relative Ser-376-phosphorylated SLP-76 protein levels were quantified and normalized to β-actin protein levels. The equation of the protein degradation rate for the Ser-376-phosphorylated WT SLP-76 protein in J14 cells is as follows: Y = −0.005032*X + 0.9911 (R2 = 0.8167, p = 0.0001). The equation of the protein degradation rate for the Ser-376-phosphorylated SLP-76 K30R mutant protein in J14 cells is as follows: Y = −0.001609*X + 0.9671 (R2 = 0.6136, p = 0.0074).

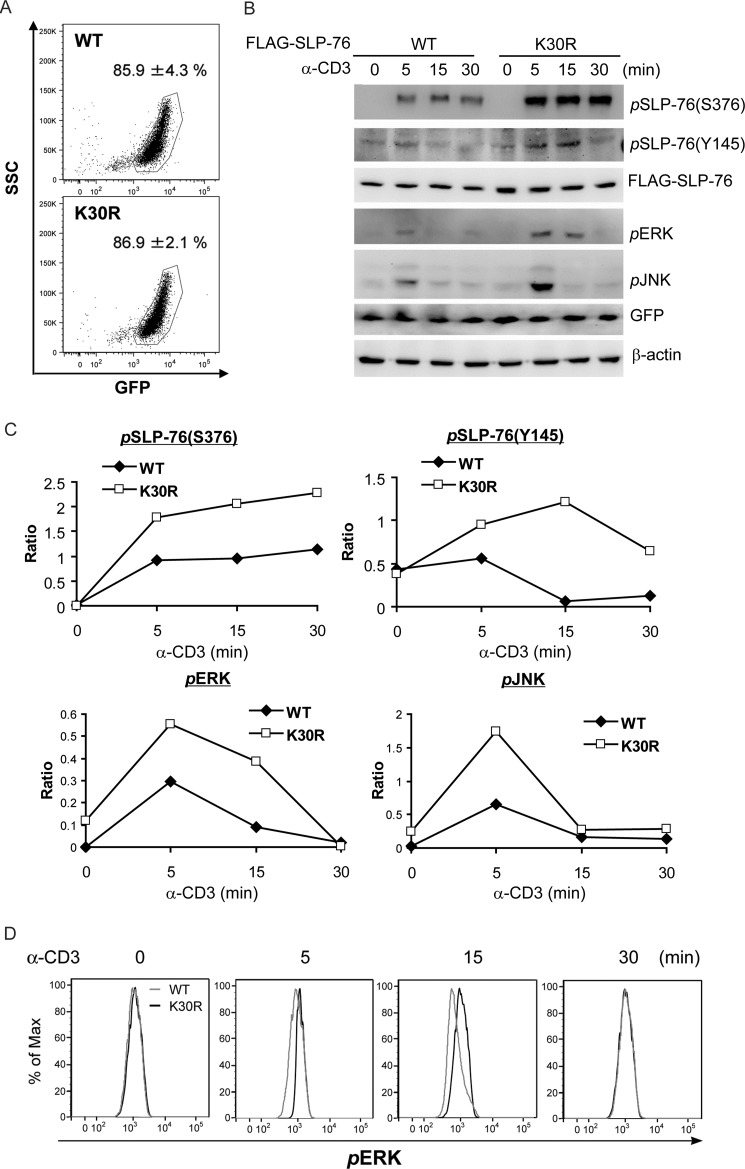

Next, we studied the effect of SLP-76 Lys-30 ubiquitination on TCR signaling in the J14 line, which displays defective TCR signaling (28). Despite equal transfection efficiency (85.9 versus 86.9%) of WT SLP-76 and the K30R mutant in J14 cells, the protein level of the K30R mutant was slightly higher than that of WT SLP-76 (Fig. 6A), which could be due to the resistance of the K30R mutant to protein degradation. SLP-76 phosphorylation at Ser-376 and Tyr-145 was increased and more sustained in the transfected J14 cells upon anti-CD3 stimulation (Fig. 6, B and C), indicating that loss of ubiquitination stabilizes activated SLP-76. Moreover, the activation of SLP-76 downstream signaling molecules, ERK and JNK, was significantly enhanced in SLP-76 K30R mutant-transfected J14 cells compared with WT SLP-76-transfected J14 cells (Fig. 6, B, C, and D). These data indicate that a loss of SLP-76 ubiquitination enhances the activation of SLP-76 and SLP-76-mediated T cell activation.

FIGURE 6.

Lys-30 ubiquitination of SLP-76 attenuates TCR signaling. FLAG-tagged (SLP-76 (WT or K30R mutant) was transfected into J14 cells, followed by anti-CD3 stimulation for different time periods. The activation of TCR signaling molecules was determined by Western blotting. A, flow cytometry analysis of transfection efficiencies of WT SLP-76 and the K30R mutant in J14 cells. GFP was coexpressed with SLP-76 via a bicistronic construct. B, the SLP-76 K30R mutant results in enhanced Ser-376 and Tyr-145 phosphorylation of SLP-76, as well as ERK and JNK activation, upon TCR signaling. The relative phosphorylation levels were determined by densitometry analysis and are shown in C. Data are representative of three independent experiments. D, flow cytometry analysis of ERK phosphorylation in J14 cells after transfection with FLAG-SLP-76 (WT or K30R mutant). The transfected cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody for 0–30 min, followed by intracellular staining of phosphorylated ERK. GFP-positive cells were gated.

DISCUSSION

As a central organizer of TCR signaling, SLP-76 is required for TCR signal transduction, leading to T cell development and activation. The activity of SLP-76 depends on its characteristic domains and phosphorylated residues, which bind to different signaling molecules. We and another research group (23) have identified Ser-376 as an HPK1-induced SLP-76 phosphorylation site that directly binds to 14-3-3. Here, we have further shown that Ser-376 phosphorylation induces SLP-76 Lys-30 ubiquitination, which targets activated (phosphorylated) SLP-76 for proteasomal degradation and therefore attenuates SLP-76-mediated TCR signaling.

In this study, we have shown for the first time that SLP-76 is regulated by ubiquitination. Anti-ubiquitin antibody detected ubiquitinated proteins from sequential anti-SLP-76 immunocomplexes in HEK293T cells and anti-CD3 antibody-stimulated Jurkat T cells, indicating that SLP-76 itself, but not its associated proteins, is ubiquitinated during TCR signaling. MG132 stabilized only the phosphorylated form of SLP-76, but not total SLP-76, suggesting that ubiquitination targets Ser-376-phosphorylated SLP-76, which is only a small population of SLP-76 proteins. This could explain why SLP-76 ubiquitination has never been reported. As Ser-376 phosphorylation attenuates tyrosine phosphorylation of SLP-76 (3, 23), it is expected that blocking of Ser-376-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of SLP-76 in MG132-treated T cells would also increase Tyr-145-phosphorylated SLP-76. Furthermore, Lys-30 was identified as an SLP-76 ubiquitin site in HEK293T cells by mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometry analysis using anti-CD3 antibody-stimulated SLP-76-transfected Jurkat T cells did not reveal Lys-30 or any other lysine residues as an SLP-76 ubiquitination site (data not shown), as the fraction of SLP-76 that is ubiquitinated in T cells is low. Nevertheless, mutations of a particular lysine to arginine that block ubiquitination provide an alternative approach to identify a ubiquitination site. In our study, the SLP-76 K30R mutant displayed dramatically reduced ubiquitination in both HEK293T cells and TCR-stimulated Jurkat T cells. This effect is unlikely due to the conformational change in the SLP-76 K30R mutant because it could still be phosphorylated upon TCR stimulation. Loss of SLP-76 Lys-30 ubiquitination in the K30R mutant resulted in resistance of phosphorylated SLP-76 to ubiquitin-mediate proteasomal degradation; thus, the SLP-76 K30R mutant displayed an increase in its phosphorylation levels. The enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation of SLP-76 led to enhanced downstream signaling, including ERK and JNK activation. Thus, our data indicate that Lys-30 is a TCR-induced SLP-76 ubiquitination site that targets activated SLP-76 for proteasomal degradation and attenuates TCR signaling.

It is notable that SLP-76 from HPK1-deficient T cells, SLP-76 S376A from transfected Jurkat T cells, and SLP-76 K30R from transfected Jurkat T cells showed some residual ubiquitination (Fig. 4, A and B, and Fig. 5C). These results suggest that SLP-76 ubiquitination may be also regulated by a mechanism independent of HPK1-induced Ser-376 phosphorylation. GLK/MAP4K3 is an HPK1-related Ste20-like serine/threonine kinase (10). Similar to HPK1, GLK also directly interacts with SLP-76, which in turn activates GLK (29). Although, GLK does not phosphorylate SLP-76 at Ser-376 (29), it remains possible that GLK may feedback phosphorylate SLP-76 on the other serine/threonine residues. Whether GLK plays a redundant role in the regulation of SLP-76 ubiquitination will be interesting to study. Finally, other SLP-76 family adaptor proteins, including BLNK and CLNK, also interact with and activate HPK1. In fact, we note that HPK1 feedback induces BLNK phosphorylation and ubiquitination in B cells during B cell receptor signaling (30). A future study of the potential regulation of CLNK activation by HPK1-induced phosphorylation may lead to interesting findings.

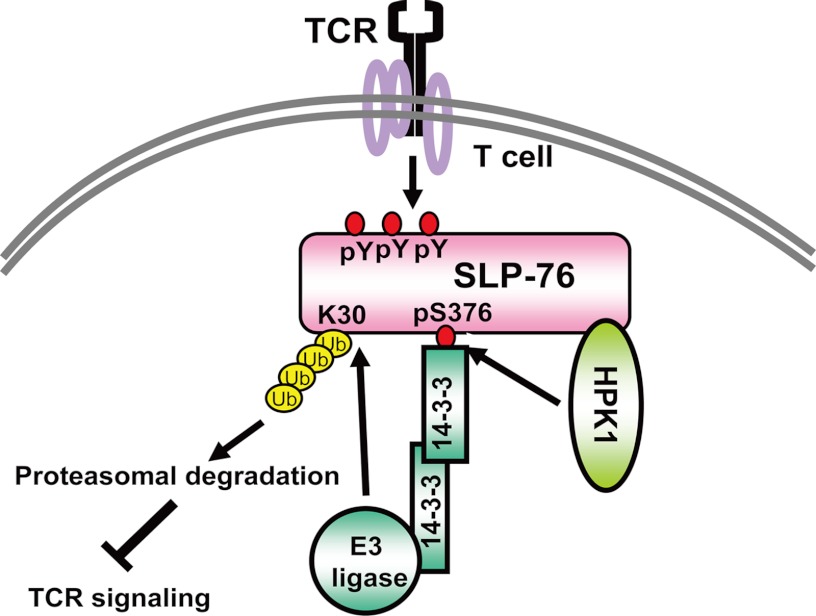

Taken together, our results demonstrate a negative feedback mechanism of SLP-76 regulation by ubiquitination, which is induced by HPK1-induced Ser-376 phosphorylation (Fig. 7). Future generation of knock-in mice expressing the SLP-76 K30R or S376A mutant will reveal the in vivo role of SLP-76 ubiquitination or Ser-376 phosphorylation in T cell-mediated immune responses and autoimmunity. This study also indicates a new direction to study the roles of other MAP4Ks in T cells and to study the regulation of other SLP-76 family adaptors by HPK1 and other MAP4Ks.

FIGURE 7.

Model of TCR signaling attenuation by SLP-76 ubiquitination. Following stimulation, SLP-76 is tyrosine-phosphorylated and activated. Activation of SLP-76 initiates the formation of the SLP-76-interacting protein complex, leading to activation of downstream TCR signaling. HPK1 is also activated by interacting with SLP-76. Activated HPK1 then induces phosphorylation of SLP-76 Ser-376, resulting in the binding of 14-3-3. 14-3-3 dimers recruit a putative E3 ubiquitin (Ub) ligase to SLP-76; the putative E3 ligase in turn induces SLP-76 ubiquitination at Lys-30, leading to degradation of activated SLP-76 and subsequent attenuation of TCR signaling.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 AI066895 (to T.-H. T.). This work was also supported by National Health Research Institute (Taiwan) Grant 98A1-IMPP01-014 (to T.-H. T.) and Taichung Veterans General Hospital (Taiwan) Grant TCVGH-NHRI01 (to J.-L. L.).

- TCR

- T cell receptor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Koretzky G. A., Abtahian F., Silverman M. A. (2006) SLP-76 and SLP-65: complex regulation of signaling in lymphocytes and beyond. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6, 67–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fang N., Motto D. G., Ross S. E., Koretzky G. A. (1996) Tyrosines 113, 128, and 145 of SLP-76 are required for optimal augmentation of NFAT promoter activity. J. Immunol. 157, 3769–3773 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shui J. W., Boomer J. S., Han J., Xu J., Dement G. A., Zhou G., Tan T. H. (2007) Hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 negatively regulates T cell receptor signaling and T cell-mediated immune responses. Nat. Immunol 8, 84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hu M. C., Qiu W. R., Wang X., Meyer C. F., Tan T. H. (1996) Human HPK1, a novel human hematopoietic progenitor kinase that activates the JNK/SAPK kinase cascade. Genes Dev. 10, 2251–2264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kiefer F., Tibbles L. A., Anafi M., Janssen A., Zanke B. W., Lassam N., Pawson T., Woodgett J. R., Iscove N. N. (1996) HPK1, a hematopoietic protein kinase activating the SAPK/JNK pathway. EMBO J. 15, 7013–7025 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang W., Zhou G., Hu M. C., Yao Z., Tan T. H. (1997) Activation of the hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 (HPK1)-dependent, stress-activated c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway by transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)-activated kinase (TAK1), a kinase mediator of TGF-β signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 22771–22775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhou G., Lee S. C., Yao Z., Tan T. H. (1999) Hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 is a component of transforming growth factor β-induced c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling cascade. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 13133–13138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen Y. R., Tan T. H. (1999) Mammalian c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway and STE-20-related kinases. Gene Ther. & Mol. Biol. 4, 83–98 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pombo C. M., Kehrl J. H., Sánchez I., Katz P., Avruch J., Zon L. I., Woodgett J. R., Force T., Kyriakis J. M. (1995) Activation of the SAPK pathway by the human STE20 homolog germinal center kinase. Nature 377, 750–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Diener K., Wang X. S., Chen C., Meyer C. F., Keesler G., Zukowski M., Tan T. H., Yao Z. (1997) Activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway by a novel protein kinase related to human germinal center kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 9687–9692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yao Z., Zhou G., Wang X. S., Brown A., Diener K., Gan H., Tan T. H. (1999) A novel human STE20-related protein kinase, HGK, that specifically activates the c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 2118–2125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hu Y., Leo C., Yu S., Huang B. C., Wang H., Shen M., Luo Y., Daniel-Issakani S., Payan D. G., Xu X. (2004) Identification and functional characterization of a novel human misshapen/Nck-interacting kinase-related kinase, hMINKβ. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 54387–54397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shi C. S., Kehrl J. H. (1997) Activation of stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase, but not NF-κB, by the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1 through a TNF receptor-associated factor 2- and germinal center kinase related-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 32102–32107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oehrl W., Kardinal C., Ruf S., Adermann K., Groffen J., Feng G. S., Blenis J., Tan T. H., Feller S. M. (1998) The germinal center kinase (GCK)-related protein kinases HPK1 and KHS are candidates for highly selective signal transducers of Crk family adaptor proteins. Oncogene 17, 1893–1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ling P., Yao Z., Meyer C. F., Wang X. S., Oehrl W., Feller S. M., Tan T. H. (1999) Interaction of hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 with adaptor proteins Crk and CrkL leads to synergistic activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 1359–1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ensenat D., Yao Z., Wang X. S., Kori R., Zhou G., Lee S. C., Tan T. H. (1999) A novel Src homology 3 domain-containing adaptor protein, HIP-55, that interacts with hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 33945–33950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sauer K., Liou J., Singh S. B., Yablonski D., Weiss A., Perlmutter R. M. (2001) Hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 associates physically and functionally with the adaptor proteins B cell linker protein and SLP-76 in lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 45207–45216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boomer J. S., Tan T. H. (2005) Functional interactions of HPK1 with adaptor proteins. J. Cell. Biochem. 95, 34–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ma W., Xia C., Ling P., Qiu M., Luo Y., Tan T. H., Liu M. (2001) Leukocyte-specific adaptor protein Grap2 interacts with hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 (HPK1) to activate JNK signaling pathway in T lymphocytes. Oncogene 20, 1703–1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ling P., Meyer C. F., Redmond L. P., Shui J. W., Davis B., Rich R. R., Hu M. C., Wange R. L., Tan T. H. (2001) Involvement of hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 in T cell receptor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18908–18914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhou G., Boomer J. S., Tan T. H. (2004) Protein phosphatase 4 is a positive regulator of hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 49551–49561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen Y. R., Meyer C. F., Ahmed B., Yao Z., Tan T. H. (1999) Caspase-mediated cleavage and functional changes of hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 (HPK1). Oncogene 18, 7370–7377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Di Bartolo V., Montagne B., Salek M., Jungwirth B., Carrette F., Fourtane J., Sol-Foulon N., Michel F., Schwartz O., Lehmann W. D., Acuto O. (2007) A novel pathway down-modulating T cell activation involves HPK1-dependent recruitment of 14-3-3 proteins on SLP-76. J. Exp. Med. 204, 681–691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Newton K., Matsumoto M. L., Wertz I. E., Kirkpatrick D. S., Lill J. R., Tan J., Dugger D., Gordon N., Sidhu S. S., Fellouse F. A., Komuves L., French D. M., Ferrando R. E., Lam C., Compaan D., Yu C., Bosanac I., Hymowitz S. G., Kelley R. F., Dixit V. M. (2008) Ubiquitin chain editing revealed by polyubiquitin linkage-specific antibodies. Cell 134, 668–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. LeBron C., Chen L., Gilkes D. M., Chen J. (2006) Regulation of MDMX nuclear import and degradation by Chk2 and 14-3-3. EMBO J. 25, 1196–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu Y. C., Elly C., Yoshida H., Bonnefoy-Berard N., Altman A. (1996) Activation-modulated association of 14-3-3 proteins with Cbl in T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 14591–14595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Naramura M., Kole H. K., Hu R. J., Gu H. (1998) Altered thymic positive selection and intracellular signals in Cbl-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15547–15552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yablonski D., Kuhne M. R., Kadlecek T., Weiss A. (1998) Uncoupling of nonreceptor tyrosine kinases from PLCγ1 in an SLP-76-deficient T cell. Science 281, 413–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chuang H. C., Lan J. L., Chen D. Y., Yang C. Y., Chen Y. M., Li J. P., Huang C. Y., Liu P. E., Wang X., Tan T. H. (2011) The kinase GLK controls autoimmunity and NF-κB signaling by activating the kinase PKCθ in T cells. Nat. Immunol. 12, 1113–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang X., Li J. P., Kuo H. K., Chiu L. L., Dement G. A., Lan J. L., Chen D. Y., Yang C. Y., Hu H., Tan T. H. (2012) Down-regulation of B cell receptor signaling by hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 (HPK1)-mediated phosphorylation and ubiquitination of activated B cell linker protein (BLNK). J. Biol. Chem. 287, 11037–11048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]