Background: Expression of the IL-7Rα gene is up-/down-regulated during T/B-lymphocyte development.

Results: IL-7Rα gene transcription is repressed by the transcription factor Gfi1, specifically in CD8+ T-lymphocytes.

Conclusion: Treatment by dexamethasone down-regulates Gfi1, which contributes to glucocorticoid receptor mediated up-regulation of IL-7R expression.

Significance: The mechanism by which the IL-7R gene gets turned on and off during development is a critical issue in biology.

Keywords: Glucocorticoids, Immunology, Thymocyte, Transcription Repressor, Zinc Finger

Abstract

Interleukin-7 receptor α (IL-7Rα) is essential for T cell survival and differentiation. Glucocorticoids are potent enhancers of IL-7Rα expression with diverse roles in T cell biology. Here we identify the transcriptional repressor, growth factor independent-1 (Gfi1), as a novel intermediary in glucocorticoid-induced IL-7Rα up-regulation. We found Gfi1 to be a major inhibitory target of dexamethasone by microarray expression profiling of 3B4.15 T-hybridoma cells. Concordantly, retroviral transduction of Gfi1 significantly blunted IL-7Rα up-regulation by dexamethasone. To further assess the role of Gfi1 in vivo, we generated bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) transgenic mice, in which a modified Il7r locus expresses GFP to report Il7r gene transcription. By introducing this BAC reporter transgene into either Gfi1-deficient or Gfi1-transgenic mice, we document in vivo that IL-7Rα transcription is up-regulated in the absence of Gfi1 and down-regulated when Gfi1 is overexpressed. Strikingly, the in vivo regulatory role of Gfi1 was specific for CD8+, and not CD4+ T cells or immature thymocytes. These results identify Gfi1 as a specific transcriptional repressor of the Il7r gene in CD8 T lymphocytes in vivo.

Introduction

A critical issue in biology is the mechanism by which genes get turned on and off during development and differentiation. Because IL-7 receptor (IL-7R) proteins provide critical survival signals to developing lymphocytes, the expression of the Il7r gene that encodes the IL-7Rα receptor protein is tightly regulated at different stages of T and B lymphocyte development and precisely timed to stages when selection and programmed cell death occur in the immune system (1–3). The expression of IL-7Rα follows an on-off-on pattern in the thymus at the CD4−CD8− double negative (DN),8 CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP), and CD4+CD8− or CD4−CD8+ single positive (SP) stages, respectively (4). Thus, developmental cues during thymocyte differentiation control IL-7Rα expression. During CD8+ memory cell generation in the peripheral immune system, Il7r gene expression again correlates with developmental outcome, in that long-lived memory cell precursors up-regulate IL-7Rα expression and short-lived CD8+ cells lose IL-7Rα expression (5). Notably, up-regulated IL-7Rα expression is not sufficient to drive long-lived memory CD8+ T cell generation, even though IL-7Rα up-regulation clearly marks progenitors of this T cell subset (6, 7). Importantly, the differentiation signals that match IL-7Rα expression to CD8 T cell fate remain unknown.

In T cells, IL-7Rα expression is thought to be primarily regulated at the transcriptional level through an array of nuclear factors whose expression is also tightly controlled during development and activation. Several transcription factors that control Il7r gene expression have been identified. The promoter of Il7r contains binding sites for the PU.1 transcription factor, which is necessary for the IL-7Rα expression in developing B cells (8, 9). The same site is occupied in T cells by another ETS family transcription factor, GABP (10). Promoter occupancy by these factors likely prevents CpG methylation of promoter sequences and subsequent down-regulation of expression in mature T cells (11). Additionally, in human thymopoiesis, Notch may be complementing these ETS family proteins by acting through a conserved RBP-Jk/CSL binding site close by in the promoter of the Il7r gene (12). Therefore, down-regulation of Notch expression at the DP stage may be causative of the complete loss of Il7r gene transcription in murine DP thymocytes. Also, the potential role of microRNAs acting on the Il7r gene locus, specifically at the DP stage has not been addressed and needs to be tested. Furthermore, the zinc finger protein Gfi1, for which a regulatory role was originally proposed in T cells and more recently confirmed in pro-B cells, was shown to bind to a putative intronic silencer (13–15). Additionally, glucocorticoid receptor (GR), Runx1/3, FoxOA1/3, and FoxP1 were all shown to bind to a putative enhancer in an evolutionarily conserved region 3.5 kb upstream of the gene (16–21). Finally FoxP3 was found to bind near the promoter in Treg cells to suppress IL-7Rα transcription (22). Importantly, however, how these factors interact with each other and what controls the mechanism of developmental stage-specific differences in Il7r gene transcription remains ill defined.

In the present study, we addressed this issue first by profiling gene expression in 3B4.15 T hybridoma cells that respond to dexamethasone (Dex) treatment by up-regulating IL-7Rα expression (23). We identified Gfi1 as a novel target of Dex and we further documented that either Gfi1 overexpression or treatment with the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) inhibitor RU486 (Mifepristone) in 3B4.15 cells prevented IL-7Rα up-regulation by Dex. These results indicate that Gfi1 is either controlled by GR or cooperates with it to down-regulate IL-7Rα expression. To further assess the role of Gfi1 in vivo, we then generated a novel bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) transgenic mouse that reports transcriptional activity of the Il7r gene locus. We show that Gfi1 is a transcriptional repressor of the Il7r gene locus, but only in CD8 lineage cells, by assessing Il7r reporter activity in Gfi1-deficient and Gfi1-transgenic thymocytes and T cells. Our observations place Gfi1 as a lineage-specific and developmental stage-dependent transcriptional repressor of IL-7Rα in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

C57BL/6 and RAG2-deficient mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Gfi1-deficient (Gfi1KO) and Gfi1-transgenic (Gfi1Tg) mice have been previously described (24, 25). Animal experiments were approved by the National Cancer Institute Animal Care and Use Committee, and all mice were cared for in accordance with National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines.

Generation of 7RIG-BACTg Transgenic Mice

A BAC clone (RP23-365P6) containing the Il7r gene locus was modified by recombineering an IRES-EGFP cassette into the 3′ UTR region of the gene in Escherichia coli (26). Briefly, a targeting vector was generated containing (1) an HincII fragment of the pIRES2EGFP plasmid (Clontech) (2), an SV40 late poly(A) signal sequence PCR amplified from the pGL3Basic plasmid (Promega), (3) a KpnI fragment of the pLTM260 plasmid containing an Frt and a loxP-flanked Neomycin resistance gene with a PGK promoter and a bGH poly(A) signal and (4) two flanking regions (210 and 300 bp long) homologous to the Il7r 3′ UTR PCR amplified from BAC DNA. This reporter BAC DNA was purified by sucrose gradient centrifugation and was injected into fertilized B6 oocytes to generate transgenic mice as described (27). Founder mice were identified by flow cytometric detection of GFP expression on peripheral blood lymphocytes. One transgenic line out of 4 founders that recapitulated IL-7Rα expression patterns on peripheral T and B lymphocytes was selected for further study and named for this study “7RIG-BACTg.” Note that this transgene is unique compared with a recently reported BAC transgene, as we utilized an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) element in the 3′ UTR to ensure GFP reporter expression coincident with transgenic IL-7Rα expression (28). The transgene was introduced into a Gfi1Tg or Gfi1KO background by breeding.

Genotyping of IL-7Rα KO Allele by Quantitative Real Time-PCR

Originally, the IL-7Rα-deficient (IL-7RαKO) mouse was generated by inserting a 1-kb MC1neo cassette into a HindIII site within the third exon of the Il7r gene, around position 90 of the 180-amino acid long extracellular domain (1). The originally inserted neor gene is a modified neor gene from pMC1Neo as described in Thomas and Capecchi (29). In this altered neomycin resistance gene, a synthetic translation initiation sequence “5′-gccaatatgggatcggcc-3′” is introduced. We used the reverse sequence of this synthetic translation initiation sequence in combination with an Il7r exon3-specific primer to amplify a short PCR fragment. The exon 3-specific primer corresponds to the amino acid sequence “GSSNICV” of the IL-7Rα extracellular domain. Copy numbers of the IL-7Rα KO allele was determined by real time-PCR using primers IL7Rex3GSSNICV and MC1neo-R.

Cell Culture and Flow Cytometric Analysis

Thymocytes or LN cells were prepared by processing thymus and LN into single cell suspensions and filtering through a 0.70-μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences). For cell culture or stimulation, processed cells were incubated at 5 × 106 cells/ml in 7.5% CO2 at 37 ºC in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 units/ml of penicillin/streptomycin, 2 mm l-glutamine, 1× minimal essential medium vitamins/nonessential amino acids, and 50 μm β-mercaptoethanol. For dexamethasone treatment, cells were incubated with 10 μm water-soluble dexamethasone (catalog number D4902, Sigma) for 18 h in the presence or absence of 10 μm mifepristone (RU486; catalog number M8046, Sigma). For flow cytometry, one million 3B4.15 hybridoma, thymocytes, or lymph node cells were used per staining with the corresponding antibodies and incubated for 45 min on ice. After washing with FACS buffer (1× HBSS, 0.5% sodium azide, 0.5% BSA), cells were analyzed on LSRII, ARIAII, FACSCanto, or FACSCalibur flow cytometers (BD Biosciences). Dead cells were excluded by forward light scatter gating and propidium iodide or 7-Aminoactinomycin D staining. Antibodies with the following specificities were used for staining: Qa-2 (clone 69H1-9-9), CD44 (clone IM7), HSA (clone M1/69), IL-7Rα (clone A7R34), IL-2Rα (clone PC61.5), IL-21R (clone ebio4A9), CD8α (clone 53-6.7); all from eBioscience); γc-chain (clone 4G3), IL-4Rα (clone mIL4R-M1), CD4 (clone GK1.5), TCRβ (clone H57–957), and B220 (RA3–6B2) (all from BD Biosciences); and IL-2Rβ (clone 5H4) from Biolegend. Data were analyzed with software designed by the Division of Computer Research and Technology at the NCI or with FlowJo 9.4.3 software (Treestar).

Adoptive Transfer

Purified LNT cells from 7RIG-BACTg and GfiTg7RIG-BACTg mice were labeled with CellTrace Violet (Invitrogen) and adoptively transferred into RAG2-deficient host mice. 4 × 106-Labeled cells were intravenously injected, and spleen and lymph node cells from host mice were harvested 5 days later. Single cell suspensions were stained for surface IL-7Rα and TCRβ expression and analyzed by flow cytometry.

RNA Isolation and Northern Blot Analysis

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen). Equal amounts of RNA were resolved in a 1.5% agarose gel under denaturing conditions and blotted onto Hybond-N+ nylon membranes (Amersham Biosciences). Radioactive probes for detecting specific gene expression were generated using the EZ-strip DNA kit (Ambion) and used to hybridize with RNA-blotted membrane in UltraHyb hybridization solution (Ambion) at 42 °C. The next day, membranes were washed two times with 2× SSC, 0.1% SDS for 30 min and two more times with 0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS at 55 °C. Membranes were exposed to a PhosphorImager screen (Amersham Biosciences) and analyzed.

Expression Plasmids and Gene Transfer

Full-length and truncation mutants of murine Gfi1 cDNAs were C-terminal FLAG epitope-tagged and cloned into the pBluescript II plasmid using oligonucleotides incorporating 5′ XhoI and 3′ NotI restriction sites. All cDNAs were transferred from pBluescript II to a retroviral expression plasmid, LZRSpBMN-linker-IRES-EGFP, using XhoI and NotI restriction enzymes. This resulted in bicistronic expression of FLAG epitope-tagged Gfi1 cDNA variants with an EGFP reporter gene. The following oligonucleotide pairs were used to amplify Gfi1 truncations: D-ZF, M13+dZFsrev; mGfi1-ZF, ZFsfor+T7; and D-SNAG, dSNAGfor+T7. LZRSpBMN-linker-IRES-EGFP with full-length or truncated Gfi1 cDNAs were transfected into Phoenix-Eco retroviral packaging cell lines with a plasmid encoding ecotropic retrovirus envelope proteins (pCL-Eco Addgene plasmid 12371) (30) and supernatants were collected for 2 days, pooled, and filtered through 45-μm filters. 3B4.15 cells were infected by spin infection in the presence of 6 μg/ml of Polybrene (Sigma).

Oligonucleotides Used in this Study

The following oligonucleotides were used to PCR amplify Gfi1 cDNA constructs. Restriction enzyme sites (XhoI and NotI) used for cloning are shown in bold lettering, FLAG epitope tag sequence is shown in italics, and the start and stop codons are underlined; M13, 5′-CGC CAG GGT TTT CCC AGT CAC GAC-3′; T7, 5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GG-3′; dSNAGfor, 5′-ATC TCG AGG CCA CCA TGC CAG GGC CGG ACT ACT CC-3′; ZFsfor, 5′-ATC TCG AGG CCA CCA TGT CCT ACA AAT GCA TCA AAT G-3′; dZFsrev, 5′-ATG CGG CCG CTA TTT ATC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC CAT GGA TCC TTT GTA GGA GCC GCC G-3′; dSNAGrev, 5′-ATG CGG CCG CTA TTT ATC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC CAT GGA TCC AGA ACG CGG CTG GTG ATA G-3′; IL7Rex3GSSNICV, 5′-GGT AGC AGC AAT ATA TGT GTG-3′; MC1neo-R, 5′-GGC CGA TCC CAT ATT GGC-3′.

Microarray Analysis

Expression analysis was performed on 3B4.15 T hybridoma cells, either untreated or treated with 1 μm dexamethasone (Sigma) for 16 h. Total RNA was extracted using TriReagent (Sigma), RNA quality was confirmed on an RNA 6000 Nano chip (AGT-5067-1511) in an Agilent Bioanalyzer. Double-stranded cDNA was generated using a SuperScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen), and the cDNA was then labeled with Cy-3, cleaned, quantified, and hybridized according to the manufacturer's protocols (Roche-Nimblegen). Nimblegen full genome Mouse Expression arrays (12X135K RO5543797) were washed and scanned at the Sabanci University Nanotechnology Research and Application Center-SUNUM. Results were processed using the ANAIS software (31). Array quality was assessed at the probe level. Values for 3 probes for each gene in each array were combined to summarize gene expression from probe sets. Robust Multi-Array Analysis background normalization and quantile normalization were performed for intra- and inter-array normalization, respectively. Genes with signal intensities above a 95% random threshold were chosen for further studies. Differentially expressed genes were obtained based on the following criteria: fold-change ≥2.5 and analysis of variance p value ≤ 0.01. Hierarchical clustering was applied to the top 500 differentially expressed genes with Genesis software (32). The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (33) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE39296.

RESULTS

Glucocorticoids Induce IL-7Rα Expression by Down-regulating Expression of Gfi1

Treatment of primary T lymphocytes and T cell lines with glucocorticoids, such as Dex, results in the up-regulation of surface IL-7Rα expression (17, 34). T cells normally express high levels of surface IL-7Rα but the I-Ek-restricted, PCC-specific T cell hybridoma 3B4.15 expresses only low levels of IL-7Rα (23). Nevertheless, when treated with glucocorticoids such as Dex, 3B4.15 cells dramatically up-regulate both IL-7Rα mRNA and cell surface protein expression (Fig. 1, A and B). These results parallel those previously obtained using the transformed murine T cell line KKF, which responds to Dex by up-regulating IL-7Rα protein expression (16). Dex treatment induces nuclear localization and binding of the glucocorticoid receptor transcription factor to an evolutionarily conserved region 3.5 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site of the Il7r gene (16). Thus, Dex-induced IL-7Rα up-regulation has been considered to be a direct transcriptional effect of activated GRs. To understand other gene regulators that control this phenotypic change, we compared the gene expression profiles of mock treated versus Dex-treated 3B4.15 cells by high coverage Nimblegen expression arrays with 135,000 features. Microarray results confirmed that Dex-treated 3B4.15 T hybridoma cells indeed up-regulated IL-7Rα gene expression (supplemental Fig. S1).

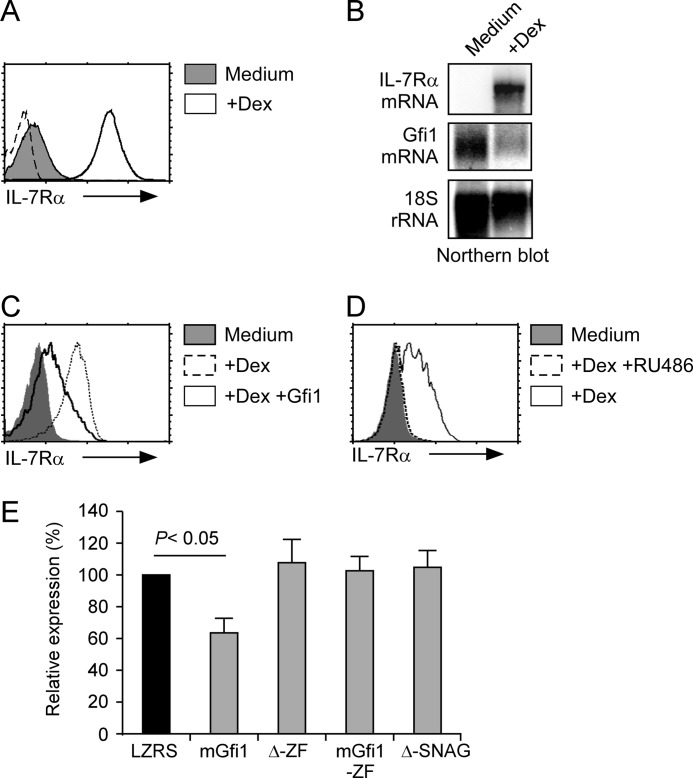

FIGURE 1.

Glucocorticoids up-regulate IL-7Rα expression while down-regulating Gfi1. A, Dex induces surface IL-7Rα expression on 3B4.15 hybridoma. Single parameter histograms of IL-7Rα expression on 3B4.15 hybridoma cells incubated overnight in medium or with Dex. Isotype staining controls are shown in dotted line. B, Dex-induced IL-7Rα expression inversely correlates with Gfi1 expression. Northern blot analysis of total RNA from overnight medium or Dex-treated 3B4.15 cells with probes indicated on the left. C, Gfi1 overexpression inhibits Dex-induced IL-7Rα expression. Histograms show surface IL-7Rα expression on control retrovirus-infected 3B4.15 cells incubated for 16 h, either in medium (filled histogram) or with Dex (dotted line). Solid histogram shows IL-7Rα expression on Dex-treated, Gfi1-expressing retrovirus-infected 3B4.15 cells. D, Dex-induced IL-7Rα expression is a glucocorticoid receptor dependent event. Histograms show IL-7Rα expression on 3B4.15 cells incubated for 16 h in medium (filled histogram), with dexamethasone (solid histogram), or with Dex in the presence of Mifepristone (RU486) (dotted line). E, zinc finger and SNAG domains of Gfi1 are required for inhibiting Dex-induced IL-7Rα expression. IL-7Rα surface expression on 3B4.15 cells was quantified into linear fluorescence units, with IL-7Rα expression on empty LZRS retrovirus-infected cells set equal to 100. Inhibition of IL-7Rα expression by retroviruses expressing either full-length (mGfi1), or domain deletions of Gfi1 were compared. Zinc finger domain deleted (Δ-ZF), N-terminal truncation containing only the ZF domain (mGfi1-ZF), and SNAG domain deleted (Δ-SNAG).

To confirm the specificity of Dex signaling in 3B4.15 hybridomas, first, we examined the expression profiles of the known Dex-regulated genes, GILZ (Tsc22d3) and GITR (Tnfrsf18) and found that these genes were positioned in the top 520 differentially expressed genes (supplemental Fig. S1) (35–37). Next, we further analyzed the expression profiles of all transcription factors that have previously been reported to regulate Il7r transcription. Among these were: glucocorticoid receptor, Gfi1, its close homolog Gfi1b, GABPα and its partners GABPβ1 and GABPβ2, PU.1 (Sfpi1), Runx1/3, NF-κB, FoxOA1/3, FoxP1, and FoxP3. Notably, we found that among these transcription factors, Gfi1 was the only one that passed our differentially expressed gene criteria of fold-change ≥ 2.5 and analysis of variance p value ≤ 0.01. Thus, Dex treatment results in an up-regulation of Il7r transcription and a dramatic down-regulation of the zinc finger repressor protein Gfi1 mRNA expression (Fig. 1B and supplemental Fig. S1).

Gfi1 was previously proposed to repress IL-7Rα transcription during lymphocyte development (14). Consequently, we wished to assess whether Gfi1 down-regulation would contribute to IL-7Rα up-regulation in 3B4.15 cells. To test this idea, we retrovirally overexpressed Gfi1 in 3B4.15 cells. Strikingly, Gfi1 overexpression inhibited IL-7Rα up-regulation by dexamethasone, and Gfi1 overexpressing 3B4.15 cells remained IL-7Rα low (Fig. 1C). Thus, Dex induces the down-regulation of endogenous Gfi1 expression, but retroviral overexpression of Gfi1 is maintained even in the presence of Dex, and results in these cells remaining IL-7Rα low. This effect was indeed directly dependent on GR, because Dex treatment in the presence of RU-486, which is a competitive inhibitor of Dex for GR binding, completely inhibited IL-7Rα up-regulation (Fig. 1D).

Next, to understand the mechanism of Gfi1-mediated repression of IL-7Rα expression, we retrovirally overexpressed a series of truncated Gfi1 cDNAs and assessed their effects on the Dex response of 3B4.15 cells (supplemental Fig. S2, A and B). Although expression of full-length Gfi1 significantly suppressed IL-7Rα re-expression, truncated Gfi1 lacking the demethylase-recruiting Snail-Gfi (SNAG) domain or the DNA binding zinc finger (ZF) domain failed to do so (Fig. 1E). Thus, repression of IL-7Rα expression by Gfi1 requires both its transcriptional repressor and the DNA binding domains and uncover Gfi1 to be a potent transcriptional inhibitor of IL-7Rα expression that acts downstream of Dex signaling, which de-represses Il7r transcription.

Assessing IL-7Rα Transcription in Vivo Using a Novel IL-7Rα Reporter Mouse

Untreated 3B4.15 cells express high levels of Gfi1 and low levels of IL-7Rα. Mature resting T cells, on the other hand, express only low levels of Gfi1 and high levels of IL-7Rα (38). Therefore, Gfi1 levels in T cells in vivo do not correspond to those in 3B4.15 T hybridomas. To test whether Gfi1 can also control IL-7Rα expression in vivo, we generated a novel IL-7Rα transcriptional reporter transgenic mouse. We used a 210-kb BAC fragment containing the Il7r gene locus and inserted an IRES-EGFP cassette in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of the Il7r gene. We used this construct in pronuclear injections to generate transgenic mice (7RIG-BACTg) (supplemental Fig. S3).

Because the BAC construct contained the full Il7r gene locus, including putative transcriptional control regions, we expected the transgenic Il7r gene to faithfully reproduce expression of endogenous Il7r. To test this, we assessed IL-7Rα surface levels on freshly isolated 7RIG-BACTg thymocytes. Endogenous IL-7Rα displays a characteristic on-off-on pattern during the progression through the DN-DP-SP stages of thymocyte development (3, 39). Indeed, 7RIG-BACTg thymocytes showed the expected on-off-on pattern for IL-7Rα expression in the thymus. These data suggest that transgenic IL-7Rα transcription is appropriately controlled in 7RIG-BACTg thymocytes (Fig. 2A). Notably, IL-7Rα expression by 7RIG-BACTg differed from that of a human CD2 promoter/enhancer-driven IL-7Rα transgene (IL-7RαTg), in its ability to down-regulate IL-7Rα expression on DP thymocytes (Fig. 2A). These results support the expectation that the BAC transgene retained all endogenous regulatory elements for correct IL-7Rα expression. Notably, IL-7Rα surface levels on 7RIG-BACTg transgenic cells were significantly higher compared with WT controls, presumably because Il7r gene transcription was active both from the endogenous and the transgenic Il7r locus. To demonstrate that the 7RIG-BACTg transgene faithfully reports Il7r gene transcription, we assessed GFP expression in thymocytes. GFP expression also followed the on-off-on pattern of IL-7Rα expression in DN, DP, and SP thymocytes, respectively, indicating that transcription from the transgenic locus was correctly inhibited in DP thymocytes (Fig. 2B). We also assessed IL-7Rα reporter expression in peripheral LN cells. Mature B cells do not express IL-7Rα. Accordingly, we found that 7RIG-BACTg DN lymph node cells, which include all mature B cells, were negative for GFP expression (Fig. 2C). CD4 and CD8 lymph node T cells, on the other hand, correctly expressed high levels of GFP. Interestingly, CD8 T cells reported higher levels of Il7r transcription than CD4 T cells based on their GFP levels (Fig. 2C). These data confirm that 7RIG-BACTg reporter mice faithfully represent endogenous IL-7Rα expression in vivo and reveal a hitherto unappreciated difference in IL-7Rα transcription levels in CD4 and CD8 T cells.

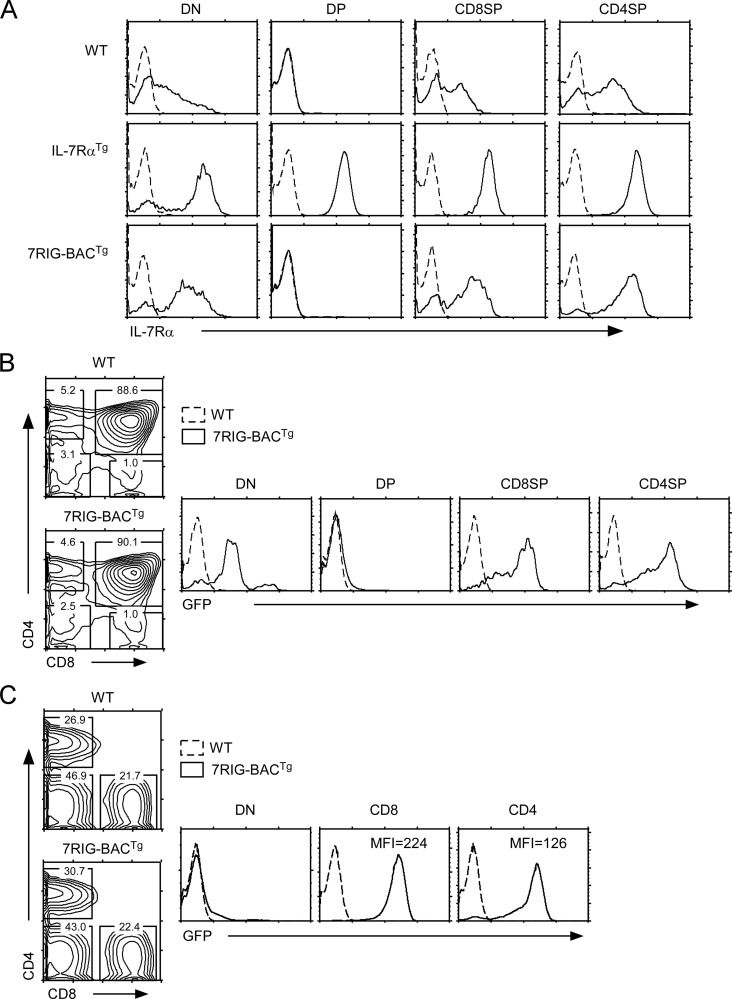

FIGURE 2.

7RIG-BACTg faithfully reports IL-7Rα expression in vivo. A, cell surface IL-7Rα expression during thymocyte development. IL-7Rα expression on gated thymocyte subpopulations from WT mice (upper panel), 7RIG-BACTg (lower panel), and a human CD2 mini-cassette driven IL-7RαTg mice (middle panel) are shown (solid line) over isotype control staining (dotted line). B, assessing IL-7Rα transcription using GFP reporter activity in thymocyte subpopulations. Total thymocytes from WT and 7RIG-BACTg mice were stained for CD4 and CD8 surface markers, and GFP expression was determined in individual subpopulations. Data are representative of four independent experiments. C, lineage specific IL-7Rα transcription in LNT cells. Total LN cells from WT and 7RIG-BACTg mice were stained for CD4 and CD8 surface markers, and GFP expression was determined in CD8 and CD4 LN T cells. Mean fluorescence intensity of surface IL-7Rα are shown for CD8 and CD4 T cells, respectively. Data are representative of four independent experiments.

Cytokine-induced Regulation of 7RIG-BACTg Expression

To further document distinct IL-7Rα expression in CD4 and CD8 T cells, we quantified surface IL-7Rα and intracellular GFP levels in freshly isolated 7RIG-BACTg LN T cells. We confirmed statistically significant higher levels of both IL-7Rα expression and transcription in CD8 T cells in multiple experiments (Fig. 3, A and B). Moreover, such lineage-specific IL-7Rα expression was developmentally set as CD4 and CD8 T cells incubated overnight in medium in the absence of in vivo signals still displayed distinct levels of IL-7Rα expression (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Transcriptional regulation of GFP reporter expression. A, relative surface IL-7Rα expression on CD4 and CD8 LNT cells. Surface IL-7Rα levels on 7RIG-BACTg T cells were quantified in mean fluorescence intensity and normalized to IL-7Rα levels on CD4 cells. Bar graph shows mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments. B, relative GFP expression in CD4 and CD8 LN T cells. Intracellular GFP levels in 7RIG-BACTg T cells were quantified in the mean fluorescence intensity and normalized to GFP levels in CD4 cells. Bar graph shows mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments. C, purified LN T cells from WT or 7RIG-BACTg mice were assessed for IL-7Rα and GFP mRNA expression by Northern blot analysis with probes indicated on the left. Total RNA was isolated from fresh, overnight medium incubated, or overnight IL-7-treated LNT cells.

The Il7r gene locus is exquisitely sensitive to cytokine signaling. For instance, in vivo IL-7 signaling down-regulates Il7r transcription and steady-state levels of IL-7Rα mRNA in T cells (13). To determine whether the transgenic IL-7Rα gene locus also responds to cytokine treatment, we incubated LN T cells from either WT or 7RIG-BACTg mice overnight in medium or in the presence of IL-7. The next day, total RNA was extracted and IL-7Rα mRNA signals were assessed and compared with those from freshly isolated T cells. In both WT and 7RIG-BACTg T cells, overnight release from the cytokine-rich in vivo environment highly up-regulated IL-7Rα mRNA expression (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, overnight IL-7 signaling potently suppressed IL-7Rα mRNA expression in both WT and transgenic T cells. These results suggest that both the endogenous and the transgenic Il7r loci are regulated in a cytokine-dependent manner. More importantly, GFP mRNA levels also faithfully replicated IL-7Rα expression, which confirms the validity of this transgenic model as an in vivo IL-7Rα reporter (Fig. 3).

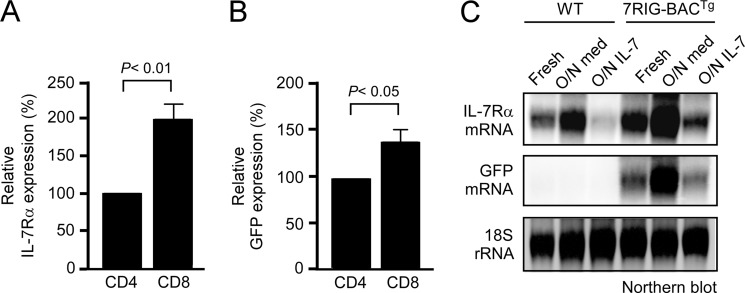

Restoring T Cell Development in IL-7Rα-deficient Mice by 7RIG-BACTg

IL-7Rα deficiency results in severely impaired T cell development and peripheral T cell homeostasis. Because 7RIG-BACTg replicates expression of endogenous Il7r, we wished to know if the BAC transgene could restore T cell defects in IL-7RαKO mice. To test this, we crossed 7RIG-BACTg into IL-7RαKO mice to generate IL-7RαKO7RIG-BACTg mice (supplemental Fig. S4A). In these mice, thymic αβ T cell development was largely restored as demonstrated by thymocyte CD4 versus CD8 profiles and TCRβ surface expression (Fig. 4A). Also, thymic NKT cell development and γδ T cell generation was dramatically improved compared with IL-7RαKO mice (supplemental Fig. S4, B and C). Notably, total thymocyte numbers were also restored compared with IL-7RαKO mice, but they did not fully recover to WT levels (Fig. 4B). To further understand this, we analyzed surface IL-7Rα levels on thymocytes, and we found that IL-7RαKO7RIG-BACTg mice expressed significantly higher levels of IL-7Rα than WT mice (Fig. 4C). This is presumably caused by insertion of multiple copies of the BAC transgene into the genome as usually observed in BAC transgenesis. Elevated levels of IL-7Rα, however, have been shown to increase IL-7 consumption and competition for IL-7, which results in an overall decrease in thymocyte numbers (40, 41). Thus, decreased total thymocyte numbers might reflect quantitative differences in surface IL-7Rα expression between WT and IL-7RαKO7RIG-BACTg thymocytes. Interestingly, however, no major differences were observed in peripheral LN T cell numbers and CD4/CD8 profiles (Fig. 4D), despite surface IL-7Rα levels on transgenic LN T cells being still higher than WT counterparts (Fig. 4E). Thus, thymocytes and LN T cells are differently affected by IL-7Rα levels, likely because of the different mechanisms of proliferation and homeostasis in these two organs. Collectively, we find that BAC transgenic IL-7Rα is expressed and regulated in a developmentally correct fashion, and consequently restores T cell development and maintenance in IL-7Rα-deficient mice.

FIGURE 4.

7RIG-BACTg restores thymocyte development and T cell homeostasis in IL-7RαKO mice. A, thymocyte development in IL-7RαKO7RIG-BACTg. Total thymocytes from WT and IL-7RαKO7RIG-BACTg mice were assessed for CD4, CD8, and TCRβ surface marker expression (top and middle). Mature TCRβhi thymocytes were analyzed for CD4 and CD8 profiles (bottom). B, total thymocyte numbers in IL-7RαKO7RIG-BACTg mice. Thymocyte numbers from WT, IL-7RαKO7RIG-BACTg, and IL-7RαKO mice were determined. Bar graph shows mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments. C, surface IL-7Rα on WT and 7RIG-BACTg thymocytes. IL-7Rα expression was determined on WT and IL-7RαKO7RIG-BACTg thymocyte subpopulations. Bar graph shows mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments. D, peripheral T cell homeostasis in IL-7RαKO7RIG-BACTg mice. LN cells were isolated, counted, and phenotyped for CD4 and CD8 expression (top). Bar graph shows total LN numbers (bottom). Data show mean ± S.E. from four independent experiments. E, surface IL-7Rα on WT and 7RIG-BACTg LNT cells. IL-7Rα expression was assessed and quantified on WT and IL-7RαKO7RIG-BACTg LN cell subpopulations. Data show representative histograms from three independent experiments.

Gfi1 Overexpression Suppresses Il7r Gene Transcription in CD8 T Cells

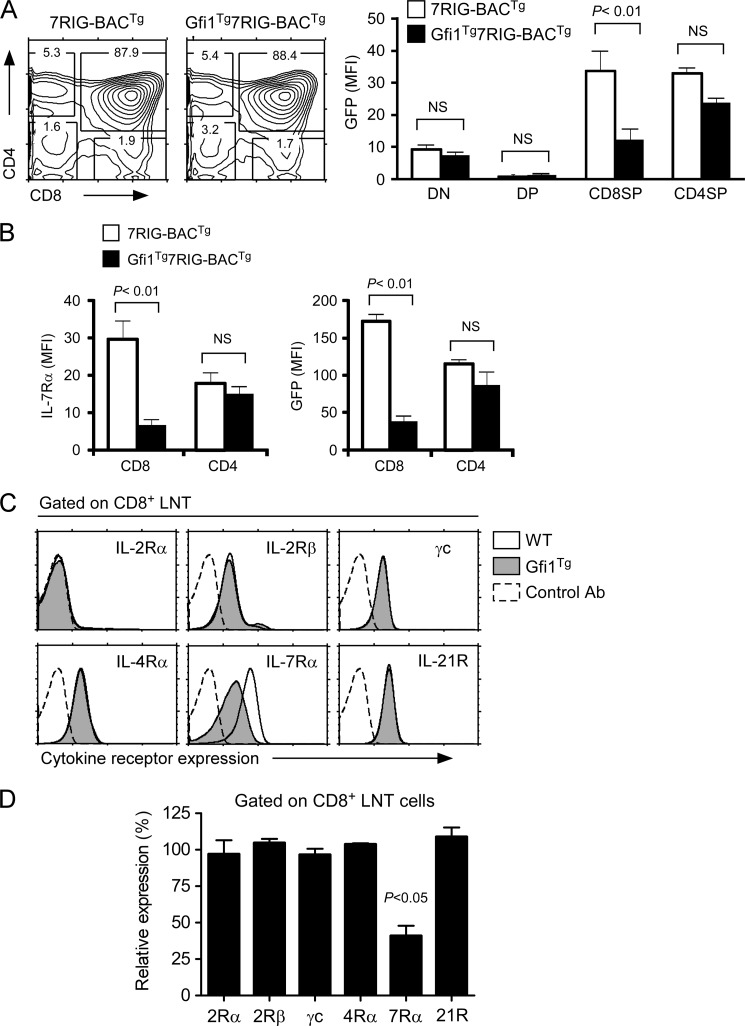

Using these reporter mice, next we asked whether Gfi1 can suppress IL-7Rα transcription and expression in vivo. To this end, we introduced the 7RIG-BACTg onto mice expressing a T lineage-specific, human CD2 promoter driven Gfi1 transgene (25) to generate Gfi1Tg7RIG-BACTg mice and determined their IL-7Rα transcription by analyzing GFP expression. Strikingly, in Gfi1Tg7RIG-BACTg thymocytes, we found that GFP levels were significantly down-regulated by Gfi1, but that this was specific and restricted to CD8SP thymocytes (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that transgenic Gfi1 expression fails to suppress IL-7Rα transcription in any other thymocyte subpopulation than in CD8SP cells. Such a specific effect of Gfi1 on CD8 lineage cells was further confirmed in peripheral CD8 T cells. We found both surface IL-7Rα and intracellular GFP levels selectively down-regulated in CD8, but not in CD4 T cells (Fig. 5B). Thus, these data document that Gfi1 only down-regulates IL-7Rα gene transcription and surface protein expression in CD8 T lymphocytes, and that all other thymocyte subpopulations and CD4 T cells are not susceptible to repression of this gene by Gfi1.

FIGURE 5.

Gfi1 suppresses IL-7Rα expression and transcription in vivo. A, suppression of GFP reporter activity by overexpression of Gfi1. IL-7Rα transcriptional activities in individual thymocyte subpopulations were determined using the 7RIG-BACTg on WT or Gfi1Tg backgrounds. Contour plots are representative of four independent experiments with 4 WT and 5 Gfi1Tg mice transgenic for 7RIG-BACTg. Bar graph shows mean ± S.E. four independent experiments. B, IL-7Rα surface expression and transcription in Gfi1Tg transgenic CD4 and CD8 LNT cells. The effect of Gfi1 was assessed in WT or Gfi1Tg mice transgenic for 7RIG-BACTg. Cell surface IL-7Rα and GFP expression were determined by flow cytometry. Bar graph shows mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments with 3 WT and 5 Gfi1Tg7RIG-BACTg mice. C, expression of γc cytokine receptor families on Gfi1Tg CD8+ LNT cells. Surface expression of the indicated γc cytokine receptors were determined on gated CD8 T cells from WT and Gfi1Tg mice. Data are representative of three independent experiments. D, Gfi1Tg specifically suppresses IL-7Rα expression on CD8+ T cells. Surface cytokine receptor levels on Gfi1Tg CD8+ T cells were quantified and normalized to levels on WT CD8+ T cells. Bar graph shows mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

To further assess the specificity of Gfi1 transcriptional repression, we examined expression of other members of the γc cytokine receptor family. The γc cytokine family is composed of IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21 (42), and antibodies are available for surface staining of each member of the γc receptor family with the exception of IL-9. Consequently, we examined expression of γc cytokine receptors for IL-2Rα, -2Rβ, γc, IL-4Rα, IL-7Rα, and IL-21R on WT and Gfi1Tg CD8 T cells (Fig. 5C). Strikingly, IL-7Rα was the only cytokine receptor that was significantly affected by Gfi1 overexpression (Fig. 5D), which revealed a highly selective effect of Gfi1 on IL-7Rα and reaffirmed its specificity for CD8 T cells.

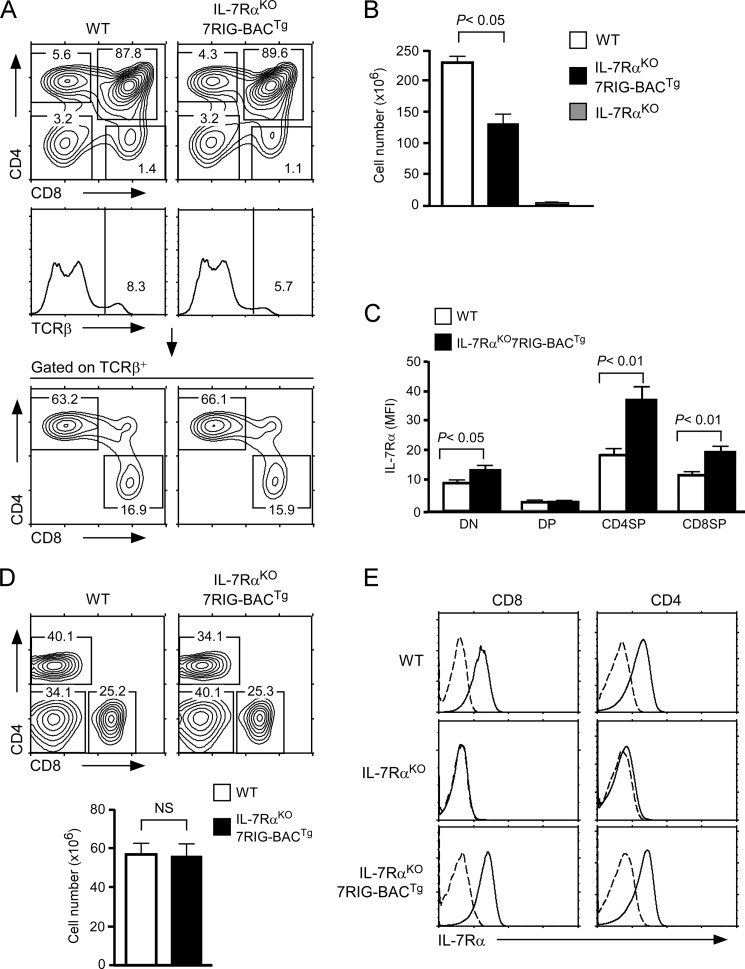

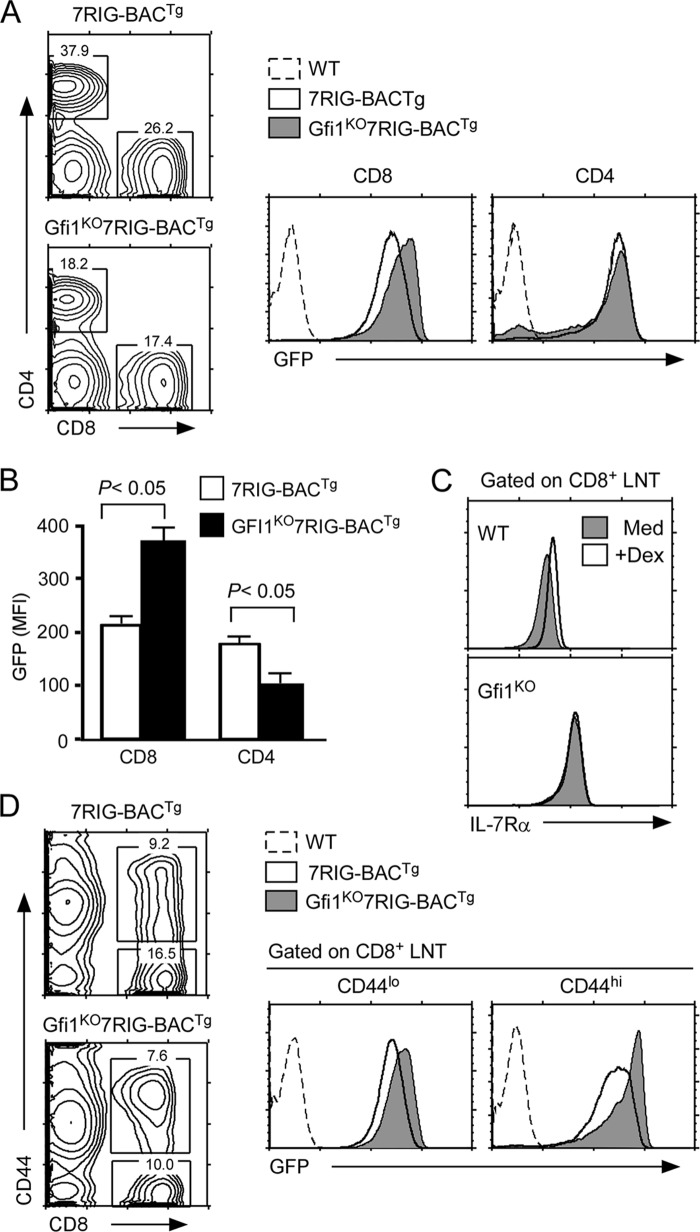

Gfi1 Deficiency Up-regulates Il7r Transcription in CD8 T Cells

Such a CD8 lineage-specific effect of Gfi1 was intriguing. One potential explanation could be that Gfi1 is expressed in all thymocytes and T cells, but that its repressor activity is only limited to CD8 T cells. Consequently, we wished to test whether removal of Gfi1 would up-regulate IL-7Rα expression in T cells other than in CD8 lineage cells. To this end, we generated Gfi1KO7RIG-BACTg mice and analyzed the GFP levels in thymocytes and mature LN T cells (supplemental Fig. S5A and Fig. 6A) (24). Notably, Gfi1 deficiency failed to de-repress IL-7Rα transcription in most thymocytes, with the exception of CD8SP thymocytes (supplemental Fig. S5A). DP thymocytes, which express high levels of Gfi1 and are completely silent for IL-7Rα transcription, were still negative for GFP expression, when Gfi1 expression was ablated. These results indicate that Gfi1 is not required to suppress IL-7Rα expression in this particular subset. Rather, the effect of Gfi1 was highly restricted to post-selection CD8 lineage cells as GFP expression was quantitatively increased in both CD8SP thymocytes and LN CD8 T cells only (supplemental Fig. S5A and Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Gfi1 deficiency de-represses IL-7Rα transcription and expression in CD8 lineage cells. A, increased GFP reporter activity in Gfi1KO7RIG-BACTg CD8 T cells. GFP expression was assessed in CD8 and CD4 T cells from WT or Gfi1KO mice expressing 7RIG-BACTg. Data are representative of four independent experiments. B, quantification of GFP expression in Gfi1KO7RIG-BACTg T cells. Mean fluorescence intensity of intracellular GFP levels were determined from 7RIG-BACTg and Gfi1KO7RIG-BACTg LNT cells. Bar graph shows the mean ± S.E. of two independent experiments. C, Dex effect on CD8+ LNT IL-7Rα expression. Surface IL-7Rα expression was determined on WT and Gfi1KO CD8 T cells incubated overnight in medium or Dex. D, the effect of Gfi1 on IL-7Rα transcription is independent of activation/differentiation status in CD8 T cells. GFP reporter expression was assessed in freshly isolated CD44lo and CD44hi CD8 T cells from 7RIG-BACTg and Gfi1KO7RIG-BACTg mice. Data are representative of four independent experiments.

Because absent Gfi1 was sufficient to up-regulate IL-7Rα expression on CD8 T cells, next, we wished to know whether this would correlate with the Dex effect that we observed in 3B4.15 cells (Fig. 1, A and B). To this end, we stimulated WT and Gfi1Tg T cells with Dex and assessed their surface IL-7Rα expression after overnight culture (Fig. 6C). Although WT CD8+ T cells significantly up-regulated IL-7Rα as previously observed (17), IL-7Rα levels on Gfi1KO CD8+ T cells were unaffected by stimulation with Dex (Fig. 6C). Notably, IL-7Rα expression on Gfi1KO CD4+ T cells was still up-regulated by Dex indicating that Gfi1 effect is CD8 lineage specific (supplemental Fig. S5B). These data strongly suggest that a major role for Dex is to suppress Gfi1, and that Gfi1 directly controls IL-7Rα expression in CD8 T cells.

Gfi1 deficiency has been proposed to promote CD8 memory phenotype cell generation (43). Because memory CD8 T cells express high levels of IL-7R (42), we wished to test whether increased IL-7Rα is a consequence of memory cell differentiation or a direct effect of Gfi1 deficiency. GFP levels in CD8 T cell subsets demonstrated that IL-7Rα transcription was significantly increased in both naive (CD44low) and activated/memory (CD44high) phenotype CD8 T cells (Fig. 6D). Thus, we conclude that absent Gfi1 expression de-represses IL-7Rα transcription and expression in all CD8 T cells independently of their differentiation status.

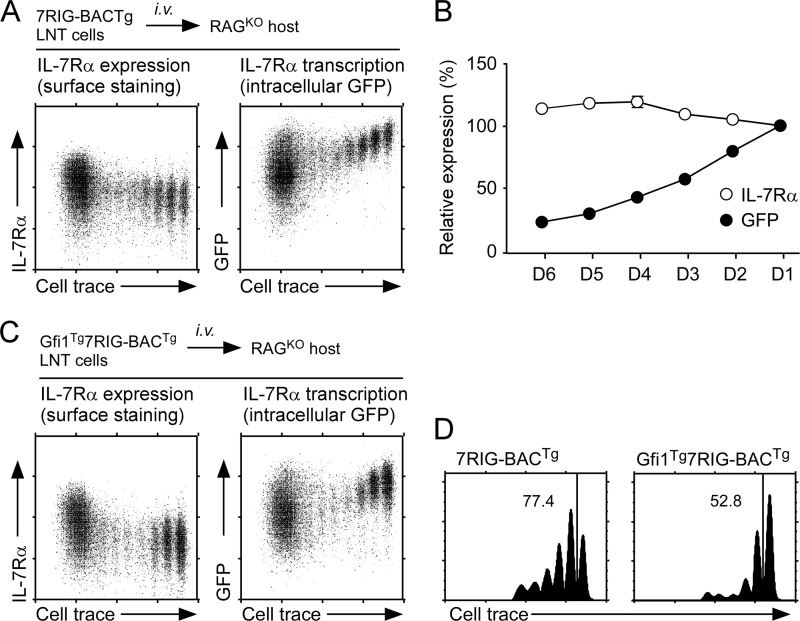

In Vivo Analysis of IL-7Rα Transcription Using 7RIG-BACTg on a Single Cell Basis

We wished to know if using the 7RIG-BACTg could provide us with new insights on IL-7Rα expression that so far has not been experimentally feasible to assess. Adoptive transfer of CD8 T cells into chronic lymphopenic mice results in lymphopenia-induced homeostatic proliferation (LIP). Slowly dividing homeostatic proliferation is dependent on IL-7, whereas rapid proliferation is IL-7 independent and driven by commensal antigens (44). To further understand the role of IL-7 in this process, it would be important to assess how IL-7Rα expression is regulated during LIP. To do so, we assessed surface IL-7Rα and intracellular GFP expression on day 5 adoptively transferred 7RIG-BACTg CD8 T cells. Analyzing IL-7Rα transcription in adoptively transferred cells on a single cell basis has not been possible so far. IL-7 signaling suppresses IL-7Rα expression under steady-state conditions (13). Surprisingly, however, surface IL-7Rα levels remained largely unchanged during IL-7-driven LIP as assessed on slowly dividing cells (Fig. 7, A, left, and B). Strikingly, in the same cells, Il7r transcription was dramatically down-regulated upon cell division, as demonstrated by reduced GFP expression in cell trace-diluted cells (Fig. 7, A, right, and B). These data indicate that surface IL-7Rα expression is not a reliable marker for Il7r transcription, at least during homeostatic proliferation. They further suggest the operation of a transcription-independent mechanism of surface IL-7R expression, which could be either increased recycling of endocytosed IL-7Rα, stabilization of pre-existing IL-7Rα proteins or a yet unknown post-transcriptional mechanism. We are currently in the process of addressing these possibilities.

FIGURE 7.

In vivo effects of Gfi1 on IL-7Rα expression. A, IL-7Rα expression during lymphopenia-induced homeostatic proliferation. Surface IL-7Rα expression and intracellular GFP expression were assessed on day 5 adoptively transferred 7RIG-BACTg CD8+ T cells in RAG-2-deficient host mice. Cell division was monitored by CellTrace Violet dye dilution. Dot plots are representative of three independent experiments. B, IL-7Rα expression and transcription in proliferating donor cells. Mean fluorescence intensity of surface IL-7Rα (open circle) and intracellular GFP (closed circle) were assessed for each cell division (D1 to D6), and normalized to nondividing cells (D1), which was set to 100 (%). Graph shows the mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments. C, IL-7Rα expression on proliferating Gfi1Tg7RIG-BACTg CD8+ T cells. Surface IL-7Rα expression and intracellular GFP expression was assessed on day 5 adoptively transferred Gfi1Tg7RIG-BACTg CD8+ T cells in RAG-2-deficient host mice. Cell division was monitored by CellTrace Violet dye dilution. Dot plots are representative of three independent experiments. D, Gfi1 impairs lymphopenia-induced homeostatic proliferation. CellTrace Violet dilutions on slow dividing donor 7RIG-BACTg or Gfi1Tg7RIG-BACTg were quantitated. Numbers indicate the percentage of cells that have undergone one or more divisions during homeostatic proliferation. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Because Gfi1 suppresses Il7r transcription, next we wished to assess the effect of Gfi1 on IL-7Rα expression during LIP. Day 5 adoptively transferred Gfi1Tg7RIG-BACTg cells displayed a comparable pattern of surface IL-7Rα and intracellular GFP expression to WT cells, in that GFP levels steadily decreased upon proliferation (Fig. 7C, right) but surface IL-7Rα levels remain largely unaffected (Fig. 7C, left). Thus, the dichotomoy of IL-7Rα transcription and surface protein expression during LIP still remained distinct in Gfi1Tg7RIG-BACTg cells. Moreover, LIP further down-regulated IL-7Rα transcription in Gfi1Tg cells, which is presumably mediated by a mechanism independent of Gfi1. Importantly, Gfi1 overexpression significantly impaired CD8 T cell LIP, which correlated with lower IL-7Rα levels on Gfi1Tg CD8 T cells (Fig. 5B). Thus, Gfi1 suppresses IL-7Rα expression and also IL-7-dependent proliferation. Taken together, these results uncover Gfi1 as a critical regulator of IL-7Rα transcription and expression in vivo, but exclusively in CD8 lineage thymocytes and T cells.

DISCUSSION

To understand the molecular mechanisms of IL-7Rα expression during T cell development and activation, here we generated a novel BAC GFP-reporter transgene and utilized this tool to assess IL-7Rα transcription in vivo. The BAC transgene was constructed by inserting a GFP-reporter and an IRES element into the 3′ UTR of the murine Il7r gene. Consequently, BAC reporter mice overexpressed full-length IL-7Rα proteins in addition to GFP. We affirmed the developmentally correct expression of reporter transgenes by assessing lymphocyte differentiation in IL-7Rα-deficient mice reconstituted with the BAC construct (IL-7RαKO7RIG-BACTg). In these mice, development of all IL-7Rα-dependent lymphoid cell populations, including αβ-, γδ-T cells, B-cells, and NKT cells, were restored. Thus, the transgenic Il7r gene locus in 7RIG-BACTg mice is correctly and lineage specifically regulated, and it equipped us with a new tool to assess IL-7Rα transcription and expression in vivo.

IL-7Rα is the ligand-specific subunit of the functional IL-7 receptor, which is composed of the IL-7Rα chain and the γc-chain (4). In contrast to the γc-chain, IL-7Rα expression is dynamic and is actively regulated during T cell development and differentiation. All developing thymocytes and all mature T cells express IL-7Rα, albeit at varying degrees. However, immature DP thymocytes are unique in that they have completely terminated IL-7Rα expression. Such peculiar absence of IL-7Rα on pre-selection DP cells was proposed to reflect a critical thymic selection mechanism that ensures a random but self-MHC-specific TCR repertoire (39, 45, 46). Accordingly, absent IL-7Rα expression renders DP thymocytes dependent on selecting TCR signals and not on nondiscriminatory IL-7 signaling for survival. However, the molecular mechanisms that terminate IL-7Rα expression in DP cells remain unclear. Along this line, the molecular circuitry that re-induces IL-7Rα expression upon positive selection also remains unmapped. This is even more intriguing as TCR signaling in mature T cells down-regulates IL-7Rα expression, but in immature DP thymocytes, TCR signaling induces IL-7Rα expression. Recent studies have suggested that re-expression of IL-7Rα on DP cells is dependent on positive selecting TCR signals in a NFAT- and MAPK-dependent fashion and to a lesser degree on Akt (47). However, the detailed mechanism and molecular events remain unknown. Using 7RIG-BACTg mice, here we establish that absent IL-7Rα expression in DP cells is a transcriptionally regulated event. Pre-selected DP cells failed to express GFP, while positive selection and maturation resulted in re-expression of GFP. With the 7RIG-BACTg reporter mouse, it is now feasible to test nuclear factors that regulate IL-7Rα transcription in vivo. We anticipate further applications of these reporter mice in dissecting the thymic signals that lead to termination as well as re-induction of Il7r transcription under various in vitro and in vivo settings.

In this regard, we were able to assess the effect of a transcriptional repressor on Il7r gene expression in vivo. Gfi1 has been considered as a potential Il7r regulator in immature thymocytes because of its high level of expression in pre-selection DP thymocytes and its potent suppression of IL-7Rα in pre-B cells. As such, Gfi1KO7RIG-BACTg mice offered a unique opportunity to assess the effect of Gfi1 on IL-7Rα transcription in DP thymocytes in vivo. The complete absence of GFP signals in Gfi1KO7RIG-BACTg DP thymocytes strongly suggested that transcriptional silencing of Il7r gene expression does not require Gfi1, at least in pre-selection DP thymocytes. In mature T cells, Gfi1 clearly plays a more critical role. In fact, Gfi1 was first reported to suppress IL-7Rα expression by analyzing peripheral mature T cells (13). Nevertheless, a definitive and direct role of Gfi1 in IL-7Rα transcription has remained highly controversial. In some cases, surface IL-7Rα expression on Gfi1KO T cells was found to be not, or insignificantly different (38), and also increased IL-7Rα levels in Gfi1KO mice had been suggested to be indirect, i.e. due to high proportions of memory cells under Gfi1 deficiency (43). Moreover, increased Gfi1 mRNA levels in human IL-7Rαhigh effector memory CD8 T cells contradicted a repressor role for Gfi1 in IL-7Rα expression (48). Our current data showing significantly increased GFP expression in GfiKO CD8 T cells, however, clearly documents Gfi1 as an in vivo repressor for IL-7Rα transcription.

Nevertheless, contradictory observations still keep open the possibility of a more complex regulatory network, with several Gfi1 co-factors being involved. As such, the cis-elements participating in the Gfi1 control of Il7r gene transcription are still not well defined. In B lymphocytes, Gfi1 can bind to the second intron of the Il7r gene to suppress transcription (14). In myeloid cells, Gfi1 can also associate with PU.1, an ETS family transcription factor that binds to the promoter of IL-7Rα and activates its transcription (49). However, PU.1 is not expressed in T lymphocytes. Rather another ETS family transcription factor, GABP, is thought to occupy the ETS site in the promoter of the Il7r gene (50). Whether Gfi1 can interact with the GABP protein is not known. But in T cells, GABP and Gfi1 were shown to have opposing roles so that a direct interaction and mutual suppression cannot be excluded (51). Thus, in addition to its role in binding the Il7r gene promoter, GABP may control Gfi1 expression as GABP-deficient splenocytes lack Gfi1 expression, presumably due to the positively acting GABP binding sites in the Gfi1 promoter (52).

With Gfi1 emerging as a key control factor in IL-7Rα expression and also in many aspects of T and B cell immunology, it is critical to know what controls Gfi1 expression. So far, an autoregulatory role for Gfi1 as well as a transregulatory role for Gfi1b has been documented (53). Also, downstream signaling of the GTPase Cdc42 has been proposed to suppress Gfi1 expression in resting T cells (54). The current study now proposes that glucocorticoids are a new family of molecules that can control Gfi1 expression. Glucocorticoids have been known to take part in thymocyte development and selection (55–58). Recently, conditional deletion of GR in pre-selection thymocytes documented significantly reduced thymus cellularity with an altered TCR repertoire and increased negative selection (59). Mechanistically, glucocorticoids have been shown to intersect with TCR signaling and increase TCR signaling thresholds to promote thymic selection (60). Our current data now also proposes a role for Gfi1 downstream of GR signaling, and it would be informative to assess the contribution of Gfi1 to the GR-deficient phenotype.

In peripheral T cells, glucocorticoids are immunosuppressive, but they also up-regulate IL-7Rα transcription and expression. The identification of Gfi1 as a novel target of Dex sheds new light onto pre-existing observations on the effects of glucocorticoids and in this regard, the discovery of Gfi1 as an intermediary of Dex in IL-7Rα expression suggests that other Dex-induced events might also employ such a mechanism. Although the up-regulation of IL-7Rα expression in Dex-treated B cells, which normally do not express IL-7Rα, could be another case of an Gfi1-mediated Dex effect (34), inhibition of cytokine production in Dex-treated cells also could be explained along this line. Further studies are planned to address these possibilities and to delineate a direct Dex effect versus Gfi1-mediated Dex effects.

Although Gfi1 expression is down-regulated by Dex signaling, and overexpression of Gfi1 can overcome Dex-mediated up-regulation of IL-7Rα, we found, as expected, that GR is critical for Dex-mediated IL-7Rα up-regulation. GR binds to a putative Il7r enhancer in an evolutionarily conserved sequence 3.5 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site (16). The GR site in this evolutionarily conserved sequence is 50 base pairs away from a FoxO1 transcription factor binding site, which positively regulates gene expression in both naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (20, 21). Whether this enhancer, the PU.1/GABP binding promoter, and the putative Gfi1-binding intronic silencer are the only functional control elements in the Il7r gene locus is not known. In fact, a series of nuclear factors are known to regulate IL-7Rα expression. In addition to Gfi1, two other transcriptional repressors have been identified that down-regulate Il7r gene expression in T cells. The forkhead family transcription factor FoxP1 suppresses IL-7Rα expression by competing with the Il7r transactivator FoxO1 for enhancer occupancy (19). On the other hand, FoxP3, which is specifically expressed in regulatory T cells, directly suppress IL-7Rα expression (22). Overexpression of a Gfi1 family member, Gfi1b, can also repress IL-7Rα expression in T lymphocytes, but presumably this effect is through the same intronic Gfi1 binding site, because the DNA binding domains of these two factors are very similar (61). Notably, in our expression profiling experiments, Gfi1 was the only nuclear factor that showed a significant difference in expression upon Dex treatment.

Collectively, the present study identified and tested a novel Il7r transcriptional control mechanism in vivo using a newly established IL-7Rα reporter mouse. We validated these reporter mice by complementing IL-7Rα deficiency, and we utilized this tool to assess Il7r transcription downstream of Gfi1. Using a lymphopenia-induced homeostatic proliferation model, we further documented the superiority of these reporter mice in assessing IL-7Rα gene transcription in T cells to traditional methods. Finally, the current study not only resolves the controversies surrounding the role of Gfi1 as a transcriptional repressor of IL-7Rα in CD8 T cells but also demonstrates that IL-7Rα expression in any other T cell population is independent of Gfi1. The molecular basis for such lineage-specific regulation of cytokine receptor expression is intriguing and important, and we think that our findings will provide a new venue to identify critical players for controlling IL-7Rα expression.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to A. Singer for critical reading of the manuscript, helpful discussions, and support throughout the course of this study; S. Kaech for critical reading of the manuscript; O. Leo for providing 3B4.15 T cell hybridoma; S. Sharrow, A. Adams, and L. Granger for expert flow cytometry; and A. Alag and T. Guinter for screening mice.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant from the Intramural Research Program, NCI, Center for Cancer Research.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5.

- DN

- double negative

- DP

- double positive

- SP

- single positive

- GR

- glucocorticoid receptor

- Dex

- dexamethasone

- BAC

- bacterial artificial chromosome

- IRES

- internal ribosome entry site

- ZF

- zinc finger

- LIP

- lymphopenia-induced homeostatic proliferation

- TCR

- T cell receptor

- GABP

- GA-binding protein

- Gfi1

- growth factor independent-1.

REFERENCES

- 1. Peschon J. J., Morrissey P. J., Grabstein K. H., Ramsdell F. J., Maraskovsky E., Gliniak B. C., Park L. S., Ziegler S. F., Williams D. E., Ware C. B., Meyer J. D., Davison B. L. (1994) Early lymphocyte expansion is severely impaired in interleukin 7 receptor-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 180, 1955–1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sudo T., Nishikawa S., Ohno N., Akiyama N., Tamakoshi M., Yoshida H. (1993) Expression and function of the interleukin 7 receptor in murine lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 9125–9129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yu Q., Erman B., Park J. H., Feigenbaum L., Singer A. (2004) IL-7 receptor signals inhibit expression of transcription factors TCF-1, LEF-1, and RORγt: Impact on thymocyte development. J. Exp. Med. 200, 797–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mazzucchelli R., Durum S. K. (2007) Interleukin-7 receptor expression: Intelligent design. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 144–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kaech S. M., Tan J. T., Wherry E. J., Konieczny B. T., Surh C. D., Ahmed R. (2003) Selective expression of the interleukin 7 receptor identifies effector CD8 T cells that give rise to long-lived memory cells. Nat. Immunol. 4, 1191–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hand T. W., Morre M., Kaech S. M. (2007) Expression of IL-7 receptor α is necessary but not sufficient for the formation of memory CD8 T cells during viral infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 11730–11735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Klonowski K. D., Williams K. J., Marzo A. L., Lefrançois L. (2006) Cutting edge. IL-7-independent regulation of IL-7 receptor α expression and memory CD8 T cell development. J. Immunol. 177, 4247–4251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. DeKoter R. P., Lee H. J., Singh H. (2002) PU.1 regulates expression of the interleukin-7 receptor in lymphoid progenitors. Immunity 16, 297–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. DeKoter R. P., Schweitzer B. L., Kamath M. B., Jones D., Tagoh H., Bonifer C., Hildeman D. A., Huang K. J. (2007) Regulation of the interleukin-7 receptor α promoter by the Ets transcription factors PU.1 and GA-binding protein in developing B cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14194–14204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xue H. H., Bollenbacher J., Rovella V., Tripuraneni R., Du Y. B., Liu C. Y., Williams A., McCoy J. P., Leonard W. J. (2004) GA-binding protein regulates interleukin 7 receptor α-chain gene expression in T cells. Nat. Immunol. 5, 1036–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim H. R., Hwang K. A., Kim K. C., Kang I. (2007) Down-regulation of IL-7Rα expression in human T cells via DNA methylation. J. Immunol. 178, 5473–5479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. González-García S., García-Peydró M., Martín-Gayo E., Ballestar E., Esteller M., Bornstein R., de la Pompa J. L., Ferrando A. A., Toribio M. L. (2009) CSL-MAML-dependent Notch1 signaling controls T lineage-specific IL-7Rα gene expression in early human thymopoiesis and leukemia. J. Exp. Med. 206, 779–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park J. H., Yu Q., Erman B., Appelbaum J. S., Montoya-Durango D., Grimes H. L., Singer A. (2004) Suppression of IL-7Rα transcription by IL-7 and other prosurvival cytokines. A novel mechanism for maximizing IL-7-dependent T cell survival. Immunity 21, 289–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deleted in proof

- 15. Zweidler-Mckay P. A., Grimes H. L., Flubacher M. M., Tsichlis P. N. (1996) Gfi1 encodes a nuclear zinc finger protein that binds DNA and functions as a transcriptional repressor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 4024–4034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee H. C., Shibata H., Ogawa S., Maki K., Ikuta K. (2005) Transcriptional regulation of the mouse IL-7 receptor α promoter by glucocorticoid receptor. J. Immunol. 174, 7800–7806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Franchimont D., Galon J., Vacchio M. S., Fan S., Visconti R., Frucht D. M., Geenen V., Chrousos G. P., Ashwell J. D., O'Shea J. J. (2002) Positive effects of glucocorticoids on T cell function by up-regulation of IL-7 receptor α. J. Immunol. 168, 2212–2218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Egawa T., Tillman R. E., Naoe Y., Taniuchi I., Littman D. R. (2007) The role of the Runx transcription factors in thymocyte differentiation and in homeostasis of naive T cells. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1945–1957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feng X., Wang H., Takata H., Day T. J., Willen J., Hu H. (2011) Transcription factor Foxp1 exerts essential cell-intrinsic regulation of the quiescence of naive T cells. Nat. Immunol. 12, 544–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kerdiles Y. M., Beisner D. R., Tinoco R., Dejean A. S., Castrillon D. H., DePinho R. A., Hedrick S. M. (2009) Foxo1 links homing and survival of naive T cells by regulating L-selectin, CCR7, and interleukin 7 receptor. Nat. Immunol. 10, 176–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ouyang W., Beckett O., Flavell R. A., Li M. O. (2009) An essential role of the Forkhead-box transcription factor Foxo1 in control of T cell homeostasis and tolerance. Immunity 30, 358–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu W., Putnam A. L., Xu-Yu Z., Szot G. L., Lee M. R., Zhu S., Gottlieb P. A., Kapranov P., Gingeras T. R., Fazekas de St Groth B., Clayberger C., Soper D. M., Ziegler S. F., Bluestone J. A. (2006) CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J. Exp. Med. 203, 1701–1711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Van Laethem F., Baus E., Smyth L. A., Andris F., Bex F., Urbain J., Kioussis D., Leo O. (2001) Glucocorticoids attenuate T cell receptor signaling. J. Exp. Med. 193, 803–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hock H., Hamblen M. J., Rooke H. M., Traver D., Bronson R. T., Cameron S., Orkin S. H. (2003) Intrinsic requirement for zinc finger transcription factor Gfi1 in neutrophil differentiation. Immunity 18, 109–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rödel B., Tavassoli K., Karsunky H., Schmidt T., Bachmann M., Schaper F., Heinrich P., Shuai K., Elsässer H. P., Möröy T. (2000) The zinc finger protein Gfi1 can enhance STAT3 signaling by interacting with the STAT3 inhibitor PIAS3. EMBO J. 19, 5845–5855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu P., Jenkins N. A., Copeland N. G. (2003) A highly efficient recombineering-based method for generating conditional knockout mutations. Genome Res. 13, 476–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brinster R. L., Chen H. Y., Trumbauer M. E., Yagle M. K., Palmiter R. D. (1985) Factors affecting the efficiency of introducing foreign DNA into mice by microinjecting eggs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 4438–4442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yu S., Zhou X., Hsiao J. J., Yu D., Saunders T. L., Xue H. H. (2012) Transgenic Res. 21, 201–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thomas K. R., Capecchi M. R. (1987) Site-directed mutagenesis by gene targeting in mouse embryo-derived stem cells. Cell 51, 503–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Naviaux R. K., Costanzi E., Haas M., Verma I. M. (1996) The pCL vector system. Rapid production of helper-free, high-titer, recombinant retroviruses. J. Virol. 70, 5701–5705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Simon A., Biot E. (2010) ANAIS, analysis of NimbleGen arrays interface. Bioinformatics 26, 2468–2469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sturn A., Quackenbush J., Trajanoski Z. (2002) Genesis. Cluster analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics 18, 207–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Edgar R., Domrachev M., Lash A. E. (2002) Gene Expression Omnibus. NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 207–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shibata H., Tani-ichi S., Lee H. C., Maki K., Ikuta K. (2007) Induction of the IL-7 receptor α chain in mouse peripheral B cells by glucocorticoids. Immunol. Lett. 111, 45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. D'Adamio F., Zollo O., Moraca R., Ayroldi E., Bruscoli S., Bartoli A., Cannarile L., Migliorati G., Riccardi C. (1997) A new dexamethasone-induced gene of the leucine zipper family protects T lymphocytes from TCR/CD3-activated cell death. Immunity 7, 803–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Riccardi C., Cifone M. G., Migliorati G. (1999) Glucocorticoid hormone-induced modulation of gene expression and regulation of T-cell death. Role of GITR and GILZ, two dexamethasone-induced genes. Cell Death Differ 6, 1182–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhan Y., Funda D. P., Every A. L., Fundova P., Purton J. F., Liddicoat D. R., Cole T. J., Godfrey D. I., Brady J. L., Mannering S. I., Harrison L. C., Lew A. M. (2004) TCR-mediated activation promotes GITR up-regulation in T cells and resistance to glucocorticoid-induced death. Int. Immunol. 16, 1315–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pargmann D., Yücel R., Kosan C., Saba I., Klein-Hitpass L., Schimmer S., Heyd F., Dittmer U., Möröy T. (2007) Differential impact of the transcriptional repressor Gfi1 on mature CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte function. Eur. J. Immunol. 37, 3551–3563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yu Q., Park J. H., Doan L. L., Erman B., Feigenbaum L., Singer A. (2006) Cytokine signal transduction is suppressed in preselection double-positive thymocytes and restored by positive selection. J. Exp. Med. 203, 165–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Laouar Y., Crispe I. N., Flavell R. A. (2004) Overexpression of IL-7Rα provides a competitive advantage during early T-cell development. Blood 103, 1985–1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Munitic I., Williams J. A., Yang Y., Dong B., Lucas P. J., El Kassar N., Gress R. E., Ashwell J. D. (2004) Dynamic regulation of IL-7 receptor expression is required for normal thymopoiesis. Blood 104, 4165–4172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rochman Y., Spolski R., Leonard W. J. (2009) New insights into the regulation of T cells by γc family cytokines. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 480–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhu J., Jankovic D., Grinberg A., Guo L., Paul W. E. (2006) Gfi1 plays an important role in IL-2-mediated Th2 cell expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 18214–18219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kieper W. C., Troy A., Burghardt J. T., Ramsey C., Lee J. Y., Jiang H. Q., Dummer W., Shen H., Cebra J. J., Surh C. D. (2005) Recent immune status determines the source of antigens that drive homeostatic T cell expansion. J. Immunol. 174, 3158–3163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Park J. H., Adoro S., Guinter T., Erman B., Alag A. S., Catalfamo M., Kimura M. Y., Cui Y., Lucas P. J., Gress R. E., Kubo M., Hennighausen L., Feigenbaum L., Singer A. (2010) Signaling by intrathymic cytokines, not T cell antigen receptors, specifies CD8 lineage choice and promotes the differentiation of cytotoxic-lineage T cells. Nat. Immunol. 11, 257–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim G. Y., Hong C., Park J. H. (2011) Seeing is believing. Illuminating the source of in vivo interleukin-7. Immune Netw. 11, 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sinclair C., Saini M., van der Loeff I. S., Sakaguchi S., Seddon B. (2011) The long-term survival potential of mature T lymphocytes is programmed during development in the thymus. Sci. Signal 4, ra77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kim H. R., Hong M. S., Dan J. M., Kang I. (2006) Altered IL-7Rα expression with aging and the potential implications of IL-7 therapy on CD8+ T-cell immune responses. Blood 107, 2855–2862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Spooner C. J., Cheng J. X., Pujadas E., Laslo P., Singh H. (2009) A recurrent network involving the transcription factors PU.1 and Gfi1 orchestrates innate and adaptive immune cell fates. Immunity 31, 576–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Anderson M. K. (2006) At the crossroads. Diverse roles of early thymocyte transcriptional regulators. Immunol. Rev. 209, 191–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chandele A., Joshi N. S., Zhu J., Paul W. E., Leonard W. J., Kaech S. M. (2008) Formation of IL-7Rα high and IL-7Rα low CD8 T cells during infection is regulated by the opposing functions of GABPα and Gfi1. J. Immunol. 180, 5309–5319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang Z. F., Drumea K., Cormier J., Wang J., Zhu X., Rosmarin A. G. (2011) GABP transcription factor is required for myeloid differentiation, in part, through its control of Gfi1 expression. Blood 118, 2243–2253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Doan L. L., Porter S. D., Duan Z., Flubacher M. M., Montoya D., Tsichlis P. N., Horwitz M., Gilks C. B., Grimes H. L. (2004) Targeted transcriptional repression of Gfi1 by GFI1 and GFI1B in lymphoid cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 2508–2519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Guo F., Hildeman D., Tripathi P., Velu C. S., Grimes H. L., Zheng Y. (2010) Coordination of IL-7 receptor and T-cell receptor signaling by cell-division cycle 42 in T-cell homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 18505–18510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ashwell J. D., Lu F. W., Vacchio M. S. (2000) Glucocorticoids in T cell development and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 309–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brewer J. A., Sleckman B. P., Swat W., Muglia L. J. (2002) Green fluorescent protein-glucocorticoid receptor knockin mice reveal dynamic receptor modulation during thymocyte development. J. Immunol. 169, 1309–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Brewer J. A., Kanagawa O., Sleckman B. P., Muglia L. J. (2002) Thymocyte apoptosis induced by T cell activation is mediated by glucocorticoids in vivo. J. Immunol. 169, 1837–1843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Purton J. F., Boyd R. L., Cole T. J., Godfrey D. I. (2000) Intrathymic T cell development and selection proceeds normally in the absence of glucocorticoid receptor signaling. Immunity 13, 179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mittelstadt P. R., Monteiro J. P., Ashwell J. D. (2012) Thymocyte responsiveness to endogenous glucocorticoids is required for immunological fitness. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 2384–2394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Vacchio M. S., Lee J. Y., Ashwell J. D. (1999) Thymus-derived glucocorticoids set the thresholds for thymocyte selection by inhibiting TCR-mediated thymocyte activation. J. Immunol. 163, 1327–1333 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Doan L. L., Kitay M. K., Yu Q., Singer A., Herblot S., Hoang T., Bear S. E., Morse H. C., 3rd, Tsichlis P. N., Grimes H. L. (2003) Growth factor independence-1B expression leads to defects in T cell activation, IL-7 receptor α expression, and T cell lineage commitment. J. Immunol. 170, 2356–2366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]