Background: Cell wall-associated glycolipids contribute to the pathogenesis of mycobacterial infections.

Results: The structure of dimycolyl-diarabino-glycerol (DMAG) from Mycobacterium marinum was determined, and this glycolipid stimulated a potent TLR-2-dependent proinflammatory response in macrophages.

Conclusion: These findings strongly suggest that DMAG modulates the host immune system.

Significance: The biological relevance of DMAG activity in immunopathogenesis of mycobacterial infection needs to be addressed.

Keywords: Glycolipid Structure, Innate Immunity, Mass Spectrometry (MS), NMR, Toll-like Receptors (TLR), Mycobacterium marinum, Mycolic Acid, Arabino-glycerolipid

Abstract

Although it was identified in the cell wall of several pathogenic mycobacteria, the biological properties of dimycolyl-diarabino-glycerol have not been documented yet. In this study an apolar glycolipid, presumably corresponding to dimycolyl-diarabino-glycerol, was purified from Mycobacterium marinum and subsequently identified as a 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf-(1→1′)-glycerol (designated Mma_DMAG) using a combination of nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and mass spectrometry analyses. Lipid composition analysis revealed that mycolic acids were dominated by oxygenated mycolates over α-mycolates and devoid of trans-cyclopropane functions. Highly purified Mma_DMAG was used to demonstrate its immunomodulatory activity. Mma_DMAG was found to induce the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-8, IL-1β) in human macrophage THP-1 cells and to trigger the expression of ICAM-1 and CD40 cell surface antigens. This activation mechanism was dependent on TLR2, but not on TLR4, as demonstrated by (i) the use of neutralizing anti-TLR2 and -TLR4 antibodies and by (ii) the detection of secreted alkaline phosphatase in HEK293 cells co-transfected with the human TLR2 and secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase reporter genes. In addition, transcriptomic analyses indicated that various genes encoding proinflammatory factors were up-regulated after exposure of THP-1 cells to Mma_DMAG. Importantly, a wealth of other regulated genes related to immune and inflammatory responses, including chemokines/cytokines and their respective receptors, adhesion molecules, and metalloproteinases, were found to be modulated by Mma_DMAG. Overall, this study suggests that DMAG may be an active cell wall glycoconjugate driving host-pathogen interactions and participating in the immunopathogenesis of mycobacterial infections.

Introduction

Tuberculosis, caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, remains a major threat to worldwide health. The incapacity to eradicate this disease is due in part to the unique mycobacterial cell envelope that plays a crucial role in widespread antibiotic resistance and pathogenesis (1). Phylogenetic studies have shown that Mycobacterium marinum (Mma)2 is closely related to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (2). This species causes systemic tuberculosis-like in fish and other ectotherms involving persistent growth within macrophages (3) and induces “fish tank disease” in humans (4), characterized by the induction of a granulomatous infection. The systemic granulomatous diseases caused by Mma in fish share many histological traits with human tuberculosis including the granuloma formation and the ability of Mma to persist in a latent state without causing disease (5). Moreover, M. tuberculosis and Mma share many virulence factors, and in general, M. tuberculosis virulence genes can complement orthologous-mutated Mma genes (6, 7). Importantly, Mma infection of its natural hosts, especially zebrafish, has recently emerged as a useful model to study tuberculosis (5, 6, 8–13). This well-established embryology model is turning into a prominent model for immunological studies and particularly to decipher the interactions between Mma in its natural host as well as to address the contribution of the innate immune system in the infection process (14). However, to gain insight into the biological significance of cell envelope-associated molecules in the immunopathology of Mma infection in zebrafish, it is important to better define the structural diversity of the immunostimulatory Mma components.

The mycobacterial cell wall comprises long-chain fatty acids (C70-C90), the mycolic acids, that can be associated to extractable glycolipids or linked to the arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan insoluble backbone to form mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan (mAGP). According to the presence of various chemical functions on the meromycolic chain, mycolic acids are generally subdivided into α-, keto-, and methoxy-mycolates (15). mAGP serves as an anchoring matrix for a vast array of (glyco) lipids that play a critical role in the modulation of the host immune system (16–19). Among them, mycolylated glycolipids such as trehalose-dimycolates (TDM), glucose-monomycolate (GMM), or glycerol monomycolate (GroMM) have been extensively scrutinized with respect to their structures and immunological properties. TDM for instance is regarded as one of the most bioactive and granulomatogenic cell wall glycolipid, exerting a potent adjuvant effect and playing a key role in mycobacterial virulence, mainly by stimulating both the innate and adaptive immunity (16, 20–22). After exposure to TDM, macrophages produce a broad panel of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL1-β, IL-12) and chemokines (IL-8, MCP-1, and MIP-1α) that are essential for granuloma formation in mice and guinea pigs (21–24). Macrophage surface C-type lectin Mincle or Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), in combination with MARCO scavenger receptor/CD14 complex, have been demonstrated to interact with TDM (25–28). The two mycolic acids on TDM reflect the mycolic acid composition of the mycobacterial strain from which the TDM is isolated. As such, the chemical structure of TDM varies substantially between strains because the mycolic acid composition differs according to mycobacterial strains. These strain differences provide a natural source of chemically distinct TDM mixtures that can be tested for biological activity. Interestingly, it was demonstrated that mycolic acid composition of TDM influences the inflammatory activity of this glycolipid. Therefore, TDM activities largely depend on the chemical nature of mycolates attached to the trehalose backbone (29, 30).

Two decades ago, another mycolic acid-containing glycolipid, designated dimycolyl-diarabino-glycerol (DMAG), was found in the Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex and in Mycobacterium kansasii (31, 32). Recently, this amphipathic hydrophobic glycolipid was identified in the cell wall of other slow-growing mycobacterial species including M. tuberculosis, Mycobacterium bovis BCG, Mycobacterium scrofulaceum, and Mma (33). Structural analyses demonstrated that DMAG from M. bovis BCG is analogous to the terminal portion of mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan, consisting in 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro (DMAG) (33). Moreover, exposure to anti-tubercular drugs (thiacetazone, ethambutol) known to interfere with the mAGP and mycolate biosynthesis altered DMAG production in both Mma and M. bovis BCG, leading to the hypothesis of a metabolic relationship between DMAG and mAGP (33). In addition, the presence of anti-DMAG antibodies in patients infected with M. avium strongly suggested that DMAG is an immunogenic compound produced (or released from the cell wall) during infection (34). However, despite the high structural analogy between DMAG and other mycolylated glycolipids, no investigation has been conducted yet regarding the eventual immunomodulatory properties of DMAG and whether this glycoconjugate interacts with the host immune receptors. The relevance of this glycolipid during mycobacterial pathogenesis remains to be fully addressed.

This study was, therefore, undertaken as a first step to decipher DMAG biological properties by focusing on its capacity to modulate the macrophage immune response and the molecular basis for macrophage recognition of DMAG. To extend our previous studies on the structural variability of Mma glycolipids and to gain new insight with respect to their biological functions, we have performed the detailed structural analysis of a family of mycolylated arabino-glycero lipids from Mma, which allowed us to assign three related molecules. The major member of this family, Mma_DMAG, was used to investigate the ability of the arabinosylated glycolipids to induce both proinflammatory cytokine secretion and expression of cell surface antigens in the human macrophage-like differentiated THP-1 cell line via a Toll-like receptor-dependent mechanism. Furthermore, these results were not only confirmed but also extended at a whole transcriptomic level in THP-1 cells exposed to Mma_DMAG. These findings provide the first report on the immunomodulatory activity of this apolar glycoconjugate.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mycobacteria and Growth Culture Conditions

Mma strain 7 (E7) was originally isolated from butterfly fish (35). It was grown at 30 °C in Sauton's medium or on plates containing Middlebrook 7H10 agar supplemented with 10% oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, and catalase enrichment.

Mma_DMAG Extraction and Purification

Apolar lipids containing DMAG were extracted from 40 g of wet cells (around 10 liters of culture) of Mma according to established procedures (36). Mma_DMAG was then purified by two successive rounds of absorption chromatography, as reported earlier (33). Briefly, the crude apolar extract was dissolved in chloroform and fractionated by silica gel column flash chromatography. The column was eluted with chloroform and chloroform/methanol with increasing volumes of methanol (1–50%). Purification of the Mma_DMAG was monitored by one-dimensional high performance TLC (Merck) using chloroform/methanol (96:4, v/v) or chloroform/methanol (90:10, v/v). Glycolipids were visualized by spraying plates with orcinol/sulfuric acid reagent followed by charring at 120 °C. Mma_DMAG fractions containing 5–7% of methanol were pooled and applied on a Florisil® column chromatography (Acros Organics). Elution was performed with chloroform followed by chloroform/methanol with increasing volumes of methanol (2–20%). Purification monitored by high performance TLC after spraying with orcinol/sulfuric acid. Mma_DMAG was eluted in fractions containing 7% of methanol and Mma_DMAG-containing fractions were pooled for structural analyses. Finally, the yield for the DMAG was about 770 μg/liter of culture.

Purification of Lipomannan

Lipomannan (LM), a known proinflammatory-inducing factor, was purified from Mma using procedures reported previously (37).

Endotoxin Levels

Potential contamination by endotoxin in Mma_DMAG and LM samples was evaluated using the Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay kit (QCL1000; Cambrex). No endotoxin was detected in Mma_DMAG sample, whereas the LM preparation contained insignificant amounts of endotoxin (<50 pg/10 μg of LM).

Extraction of Mycolic Acids from DMAG

Extraction of mycolic acid methyl esters was carried out as described previously (38, 39). Briefly, purified DMAG were subjected to alkaline hydrolysis in 1 ml of 15% tetrabutylammonium hydroxide at 100 °C overnight. After cooling, free mycolic acids were methyl-esterified by the additions of 2 ml of dichloromethane, 150 μl of iodomethane, and 1 ml of water. The mixture was sonicated and then centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 min. The aqueous phase was discarded, and the dichloromethane phase containing mycolic acid methyl esters was washed three times with 2 ml of water. Finally, the organic phase was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen, and the sample was diluted in chloroform before mass spectrometry analysis.

Matrix-assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-MS) Analysis

The molecular masses of glycolipids were measured by MALDI-TOF on a Voyager Elite reflectron mass spectrometer (PerSeptiveBiosystems, Framingham, MA) equipped with a 337-nm UV laser. Samples were prepared by mixing 5 μl of glycolipid solution in chloroform and 5 μl of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid matrix solution (10 mg/ml dissolved in chloroform/methanol (1/1, v/v). The mixtures (2 μl) were then spotted on the target.

NMR Analysis

NMR experiments were recorded at 300 K on a Bruker Avance 400 spectrometer equipped with a 5-mm broad-band inverse probe, respectively. Before NMR spectroscopic analyses, Mma_DMAG was repeatedly exchanged in CDCl3/CD3OD (2:1, v/v) (99.97% purity, Euriso-top, Saint-Aubin, France) with intermediate drying and finally dissolved in CDCl3 and transferred to Shigemi (Allison Park, PA) tubes. Chemical shifts (ppm) were calibrated using the tetramethylsilane signal (δ1H/δ13C 0.000 ppm) in CDCl3 as an internal reference. The COSY, TOCSY, and 13C HSQC experiments were performed using the Bruker standard sequences.

Cell Culture Conditions

Human pro-monocytic leukemia THP-1 cells (ECACC no. 88081201) were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mm l-glutamine, and 2 × 10−5 m β-mercaptoethanol in a 5% CO2/air-humidified atmosphere at 37 °C. Differentiation into macrophage-like cells was induced with 50 nm 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 for 72 h in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and 2 mm l-glutamine. Viability of the cells was checked by trypan blue dye exclusion and by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur flow cytometer) by using propidium iodide. HEK-Blue-hTLR2 cells and HEK-Blue-Null1 cells were purchased from InVivogen (Toulouse, France) and maintained in growth medium supplemented with HEK-blue selection according to the manufacturer's instructions. HEK-Blue-hTLR2 cells were obtained by co-transfection of the hTLR2 and secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) reporter genes into human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells. The SEAP reporter gene was placed under the control of the IFN-β minimal promotor fused to five NF-κB and AP-1 binding sites. HEK-Blue Null1 cells, the parental cell line of HEK-Blue-hTLR2, carry the SEAP reporter gene alone.

Quantification of Cytokine Secretion by ELISA

To investigate the effect of Mma_DMAG on TNF-α, IL-8, and IL-1β secretion, differentiated THP-1 cells were seeded in 96-well plastic culture plates at a density of 25 × 104 cells/well in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2% FCS and l-glutamine. Because Mma_DMAG was insoluble in aqueous medium, it was resuspended in hexane at the indicated concentrations and coated on plates. Wells were subsequently dried at 37 °C to ensure complete solvent evaporation before cell addition. Control wells were layered with solvent without glycolipids. LM purified from Mma, dissolved in apyrogen water, and sonicated was used as a positive control. After 6 or 24 h of incubation, culture supernatants were collected and analyzed for the detection of TNF-α, IL-8, and IL-1β by sandwich ELISA according to the manufacturers' instructions (Ozyme S.A.). Cytokine concentrations were determined using standard curves obtained with recombinant human TNF-α, IL-1β, or IL-8. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t test (only values of p < 0.05 were considered to be significant).

Flow Cytometry Analysis

The expression level of the cell surface markers was determined after stimulation of differentiated THP-1 cells (at a density of 3.5 × 105 cells/well) with either Mma_DMAG or LM in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2% FCS and l-glutamine as previously reported (40). Control wells were layered without glycolipids. After 24 h of incubation, expression of human ICAM-1 (CD54) and CD40 was determined by flow cytometry. Briefly, 250,000 cells were incubated for 20 min at 4 °C with 20 μg/ml human IgG (Sigma), washed 3 times, and incubated for 40 min with 10 μl of PE-conjugated anti-ICAM-1 (CD54) or FITC-conjugated anti-CD40 mouse monoclonal IgG1κ antibodies (BD Biosciences) in PBS containing 0.04% NaN3 and 0.05% BSA. Both PE- and FITC-conjugated mouse isotype control IgG (BD Biosciences) were used as negative controls. In all experiments, cells were washed twice. Data were monitored on a flow cytofluorimeter (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences) and analyzed with the CellQuest software (Mountain View, CA). Cells were gated for forward- and side-angle light scatters, the fluorescence channels were set on a logarithmic scale, and the mean fluorescence intensity was determined.

TLR Neutralization

To address the participation of TLRs in the proinflammatory-inducing activity of Mma_DMAG, differentiated macrophages were pretreated with 15 μg/ml neutralizing monoclonal against anti-TLR2 or anti-TLR4 for 30 min at 37 °C. Mouse IgG2a anti-TLR2 (clone TL2–1) was purchased from Biolegend, whereas mouse IgG2aκ was from eBiosciences. Cells were then stimulated with 20 μg/ml Mma_DMAG for 6 or 24 h to allow TNF-α secretion or ICAM-1 expression, respectively. The corresponding isotype antibodies were used as negative controls. Supernatants were processed for TNF-α and IL-8 quantification by ELISA, whereas ICAM-1 expression was determined by flow cytometry, as described above. Statistical significance between antibody-pretreated cells and untreated cells was calculated by using Student's t test. Values with p < 0.05 were considered significant.

HEK-TLR2 Experiment

HEK-Blue-hTLR2 that stably expresses the human TLR2 gene along with a NF-κB-inducible reporter system (secreted alkaline phosphatase) and the parental HEK-blue-Null1 cell line were seeded at 5 × 104 cells/well in 96-wells plates and stimulated with either 20 μg/ml Mma_DMAG or 20 ng/ml lipopeptide Pam3Cys-SKKKK (Pam3CSK4; EMC Microcollections GmbH, Germany), a well known TLR2 agonist. Stimulation with a TLR2 ligand activates NF-κB and AP-1, which induce production of SEAP. After 20 h of incubation at 37 °C, SEAP activity was determined using the QUANTI-Blue detection kit by measuring the absorbance at 630 nm. Statistical significance of between the unstimulated and stimulated HEK-Blue-hTLR2 cells was determined using Student's t test, and only p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Microarrays Data Processing and Statistic Analyses

Differentiated THP-1 cells (3 × 106) were incubated for 8 h either with medium alone or medium supplemented with 20 μg/ml Mma_DMAG. Total RNA was extracted from the cells using the Nucleospin RNA II kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren), according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentrations were determined using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies), and RNA quality was assessed using Agilent RNA Nano 6000 LabChip kits and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). All RNA samples had RNA integrity numbers of 9.7 or higher. A human (4 × 44,000) whole genome oligo DNA microarray chip (G4112F, Agilent Technologies) was used for global gene expression analysis. 2μg of total RNA was used in the Agilent Quick Amp Labeling kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. After purification using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), cRNA yield and incorporation efficiency (specific activity) into the cRNA were determined using a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific) spectrophotometer. For each sample, a total of 2 μg of cRNA was fragmented and hybridized to the whole human genome oligo 4 × 44,000 microarrays overnight at 65 °C. Slides were washed and treated with stabilizing and drying solution according to the manufacturer (Agilent Technologies). The array was scanned on a InnoScan 700 scanner (Innopsys) and further processed using Mapix 2.6.1 software. The resulting text files were uploaded into language R for analysis and analyzed using the LIMMA package (Linear Model for Microarray Data) (41, 42). A within-array normalization was performed using LOWESS (locally weighted linear regression) to correct for dye and spatial effects (43). Moderate t-statistic with empirical Bayes shrinkage of the standard errors (44) was then used to determine significantly modulated genes. Statistics were corrected for multiple testing using a false-discovery rate approach.

RESULTS

Structure of Mycobacterium marinum DMAG

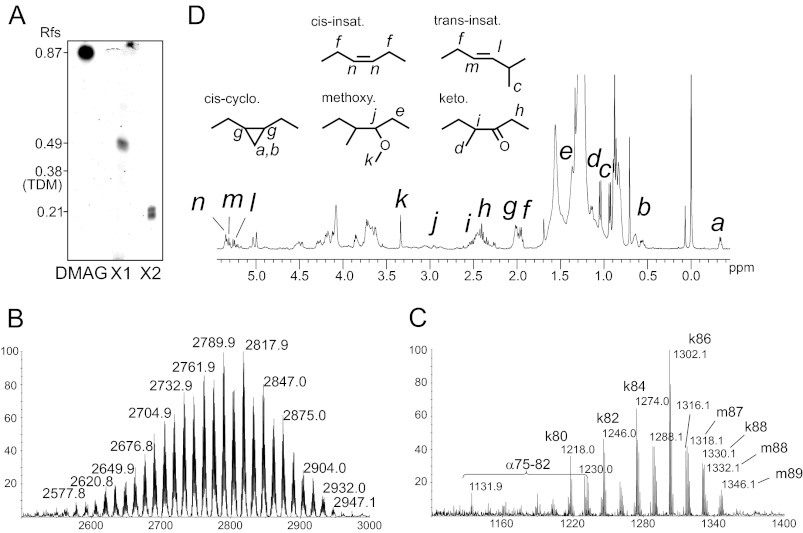

We have recently shown that several slow-growing mycobacterial species, including M. bovis BCG, M. tuberculosis, and Mma produce an apolar cell wall-associated glycolipid whose synthesis was altered by several anti-tubercular drugs inhibiting arabinogalactan or mycolic acid biosynthesis (33). Structural elucidation of this product in M. bovis BCG identified it as 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro, designated di-mycolyl di-arabino-glycerol (DMAG). To extend these studies regarding the structural diversity of DMAG and to undertake structure/function relationship studies, we purified and determined the fine structure of DMAG in Mma strain 7. This natural strain, originally isolated from infected butterfly fish, has previously been reported to exhibit an altered lipooligosaccharide (LOS) profile compared with the standard M strain (45). As reported earlier, a glycolipid presumably corresponding to DMAG was purified from the apolar extract by adsorption chromatography on a silica gel column using a gradient of methanol in chloroform. This component yielded a major orcinol-reactive component with an Rf of 0.87 compared with 0.38 for TDM on TLC plates using chloroform/methanol (96:4; v/v) as a running solvent (Fig. 1A). In addition, two minor undefined glycolipids (Rf of 0.49 and 0.21, respectively) with chromatographic mobilities closer to TDM (Rf 0.38) were also tentatively attributed to arabinose-containing glycolipids based on their distinctive intense blue color upon orcinol staining.

FIGURE 1.

Structural analysis of Mma_DMAG. A, a TLC profile of purified arabino-glycero lipids from Mma shows the major compound identified as di-mycolyl di-arabino-glycerol (Mma_DMAG) and two minor related glycoconjugates identified as mono-mycolyl mono-arabino-glycerol (X1) and mono-mycolyl di-arabino-glycerol (X2). Rf are indicated in the left margin. MALDI-TOF-MS spectrum of intact Mma_DMAG (B) and mycolic acid methyl esters (MAMEs) (C) derived from Mma_DMAG show the presence of α-, keto-, and methoxy-mycolic acids. D, 1H NMR spectrum of Mma_DMAG; a to n indicate the relevant signals used for the identification of functional groups of mycolates.

MALDI-TOF-MS analysis indicated that the DMAG from Mma (Mma_DMAG) exhibited a heterogeneous molecular mass profile ranging from 2577 to 2947 Da, with the most abundant molecular species at 2790 and 2818 Da (Fig. 1B). MS analysis of the methyl-esterified lipid moiety released from Mma_DMAG by alkaline hydrolysis revealed a heterogeneous pattern attributed to a mixture of alpha (α), keto (k), and methoxy-mycolates (m) with m/z values ranging from 1132 (αC75) to 1346 (mC89) and dominated by two signals at m/z 1274 and 1302 attributed to [M+Na]+ adducts of C84 and C86 ketomycolates (Fig. 1C). Consistent with the prevalence of keto- and methoxy-mycolates over α-mycolates, Mma_DMAG subspecies were mainly found to be substituted by oxygenated mycolates. Indeed, based on the tentative presence of a Ara2Gro moiety, mycolate composition of major Mma_DMAG signal clusters around m/z 2790 and m/z 2818 were assigned to DMAGs substituted by a mixture of keto- and methoxy-mycolates bearing totals of 166 and 168 carbons, respectively. The presence of oxygenated keto- and methoxy-mycolates was confirmed by 1H NMR analysis of intact Mma_DMAG (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, 1H NMR analysis allowed us to detect the presence of trans- and cis-ethylene groups as well as cis-cyclopropane groups. The presence of cis-cyclopropane was established by the observation of CH2 signals at δ −0.33 and 0.57, whereas trans-cyclopropane functional groups could not be observed, in agreement with previous observations on total mycolic acids from Mma (46). The structure of the glycan moiety of Mma_DMAG was next investigated by 1H/1H COSY, TOCSY, and 13C,1H HSQC NMR experiments, allowing us to attribute its individual 13C,1H NMR parameters based on those previously assigned for M. bovis BCG DMAG (Fig. 2, Table 1) (33). As observed Fig. 2, two anomer signals were identified at 13C,1H δ 4.99/106.0 and δ 5.02/101.5 ppm, thus confirming the presence of two different monosaccharides. Their spin systems determined by 1H/1H NMR experiments typified them as 5-acylated α-Araf and β-Araf residues, respectively (Fig. 2A). The deshielding of α-Araf-C2 (Δδ = +6.0) compared with that of non-reducing terminal α-Araf established that this residue was substituted in position C2 (Fig. 2B). Finally, the identification of a C1-substituted glycerol residue (Gro) confirmed the structure of Mma_DMAG as 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro. Although not demonstrated in this study, the arabinose residues are believed to be in a d configuration based on the exclusive identification of d-Ara in all mycobacterial glycoconjugates so far and because of its postulated filiation with mAGP (33). Overall, this analysis indicates that DMAG from Mma is extremely similar to the one from M. bovis BCG, with the notable exception for its lipid moiety comprising a mixture of α-, keto- and methoxy-mycolates in Mma instead of α- and keto-mycolates only in M. bovis BCG. In addition, mycolates of Mma_DMAG lack a trans-cyclopropane ring. Along with Mma_DMAG, the partial structural analysis of the two minor arabinose-containing glycolipids (Fig. 1A) permitted their identification as 5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro and a mixture of β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro and 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro, respectively (data not shown). However, the limited amount of each of these compounds precluded further biological analyses.

FIGURE 2.

NMR analysis of the Mma_DMAG glycan moiety. 1H/1H TOCSY (A) and 13C,1H HSQC (B) NMR spectra of Mma_DMAG permitted us to establish the structure of Mma_DMAG as 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro.

TABLE 1.

1H and 13C chemical shifts of 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf-(1↔1')-Gro isolated from M. marinum

| H-1/C-1 | H-2/C-2 | H-3/C-3 | H-4/C-4 | H-5/C-5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Araf | 5.02/101.5 | 4.07/77.8 | 4.06/76.6 | 4.07/79.6 | 4.18, 4.52/65,2 |

| α-Araf |

Proinflammatory Activity of Mma_DMAG

A plethora of reports demonstrated the immunomodulatory properties of cell wall-associated mycolylated glycolipids, which may represent key effectors in the induction of the host defense through the activation of macrophage and antigen presenting cells. Most studies have focused on TDM, GroMM, and GMM (22, 27, 47). Considering the structural similarity between these lipids with DMAG regarding their mycolic acid composition, we reasoned that the DMAG family of glycolipids may also participate to the modulation the host immune response. To check this hypothesis, we first evaluated the ability of Mma_DMAG to induce the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages and to stimulate the expression of cell surface antigens.

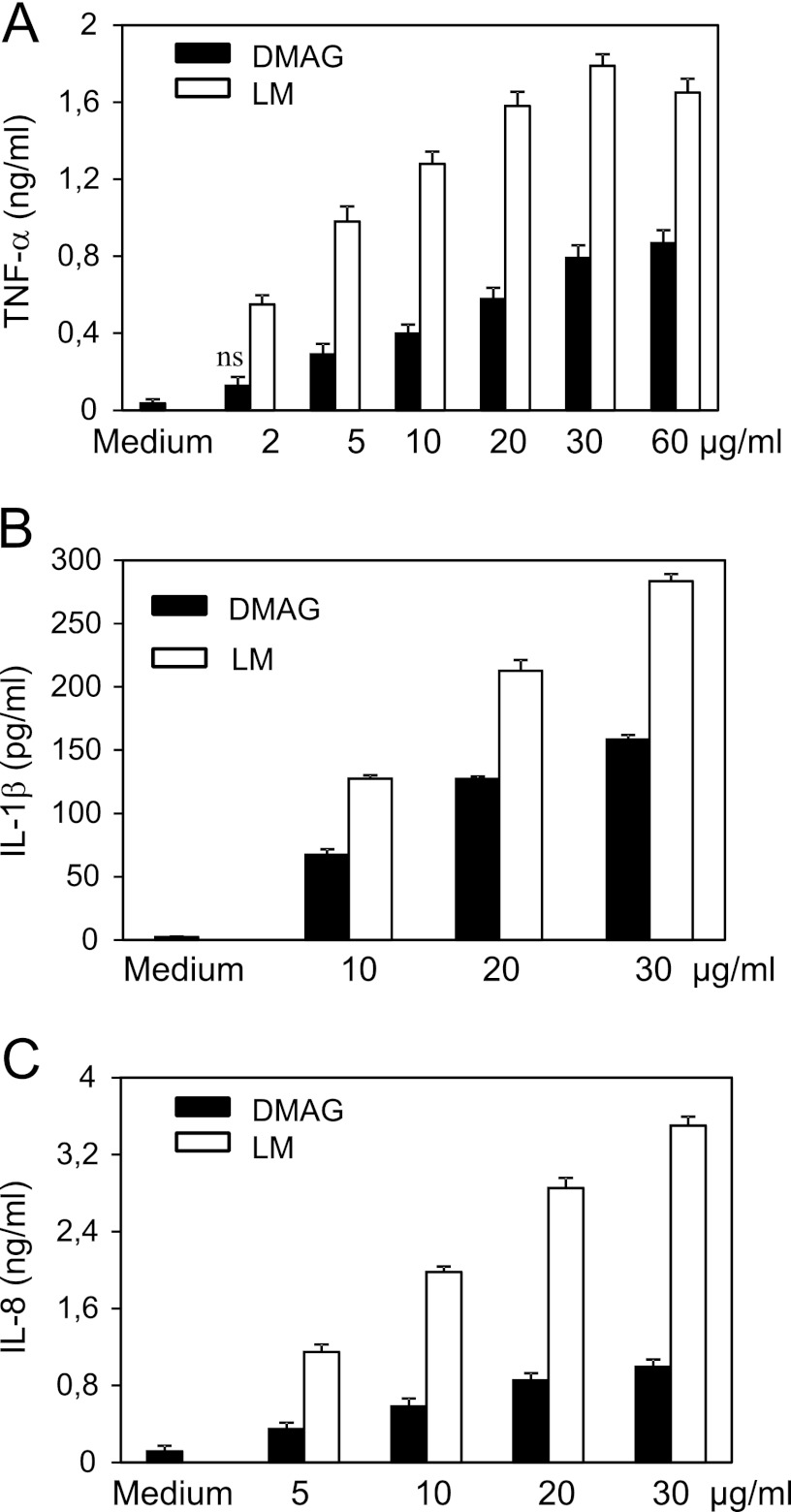

TNF-α is a key mediator involved in the initiation and the maintenance of the granulomatous response (48, 49), whereas IL-1β represents another important proinflammatory cytokine that contributes to anti-mycobacterial host defense mechanisms (50), whose production is induced by M. tuberculosis through different pathways involving TLR2/TLR6 and NOD2 receptors (51). IL-8 mediates the recruitment of neutrophiles during mycobacterial infection (49). The capacity of Mma_DMAG to trigger TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8 secretion was investigated on differentiated THP-1 cells, which have been extensively used to test the biological effects of mycobacterial glycolipids (52, 53). Mma_DMAG was found to induce the release of TNF-α (Fig. 3A), IL-1β (Fig. 3B), and IL-8 (Fig. 3C) from differentiated cells. The optimal response regarding TNF-α secretion was achieved with 30 μg/ml Mma_DMAG. The level of cytokines induced by DMAG was about 18-fold higher for TNF-α and 30-fold higher for IL1-β compared with un-stimulated cells (medium alone). IL-8 production was also significantly increased (9-fold) in the presence of various concentrations of DMAG (Fig. 3C). LM purified from Mma was included as a positive control because it has been reported to exhibit a significant proinflammatory response (52–55). Mma_DMAG exhibited, however a lower proinflammatory activity compared with LM (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Proinflammatory cytokines secretion by THP-1 macrophages stimulated with Mma_DMAG. Differentiated THP-1 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of either Mma_DMAG or LM from Mma. Culture supernatants were collected after 6 or 24 h and assayed by ELISA for TNF-α (A), IL-1β (B), and IL-8 (C) secretion. Data are expressed as the means ± S.D. of triplicates and are representative from three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed by using Student's t test (p values were < 0.05; ns, nonspecific p > 0.05).

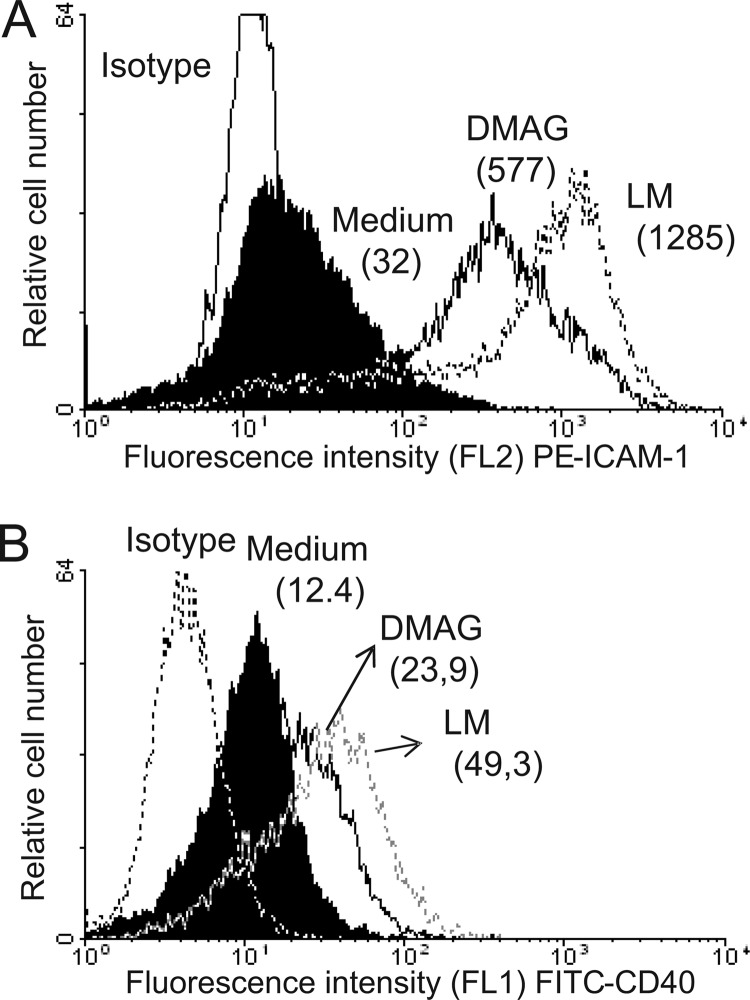

The interaction of ICAM-1 (CD54) with α1/β2 integrin (CD11a/CD18) leads to the activation and the proliferation of T cells, whereas the co-stimulatory protein CD40 is required for the activation of antigen presenting cells (56). To address whether DMAG stimulates the expression of macrophage cell surface markers, THP-1 macrophages were incubated with either LM or Mma_DMAG and analyzed by flow cytometry using either PE-conjugated anti-ICAM-1 or FITC-conjugated anti-CD40 antibodies. As shown in Fig. 4, Mma_DMAG induces the expression of both ICAM-1 and CD40 at the surface of THP-1 cells, albeit to a lesser extent than LM. As expected, no significant fluorescence signal could be detected using isotype control antibodies.

FIGURE 4.

Cell surface antigen expression on THP-1 macrophages stimulated with Mma_DMAG. Differentiated THP-1 cells were left untreated (Medium) or incubated with 20 μg/ml of purified Mma_DMAG or LM. After 20 h of incubation, ICAM-1 (CD54) (A) and CD40 (B) expression was determined by flow cytometry using PE-conjugated anti-CD54 or FITC-conjugated anti-CD40, respectively. Cells were exposed also with irrelevant antibodies (PE- or FITC-conjugated mouse isotype controls). Results are shown as linear-log scale fluorescence histograms. The mean fluorescence intensity is shown in parentheses. The results presented are from one representative experiment of three independent experiments with similar results.

Overall, these results indicate that, like other mycolic acid-containing glycolipids, DMAG is a biologically active molecule exhibiting potent proinflammatory activity and promoting macrophage activation, both being relevant to macrophage-lymphocyte interaction/recruitment and mycobacteria-induced immunopathogenesis.

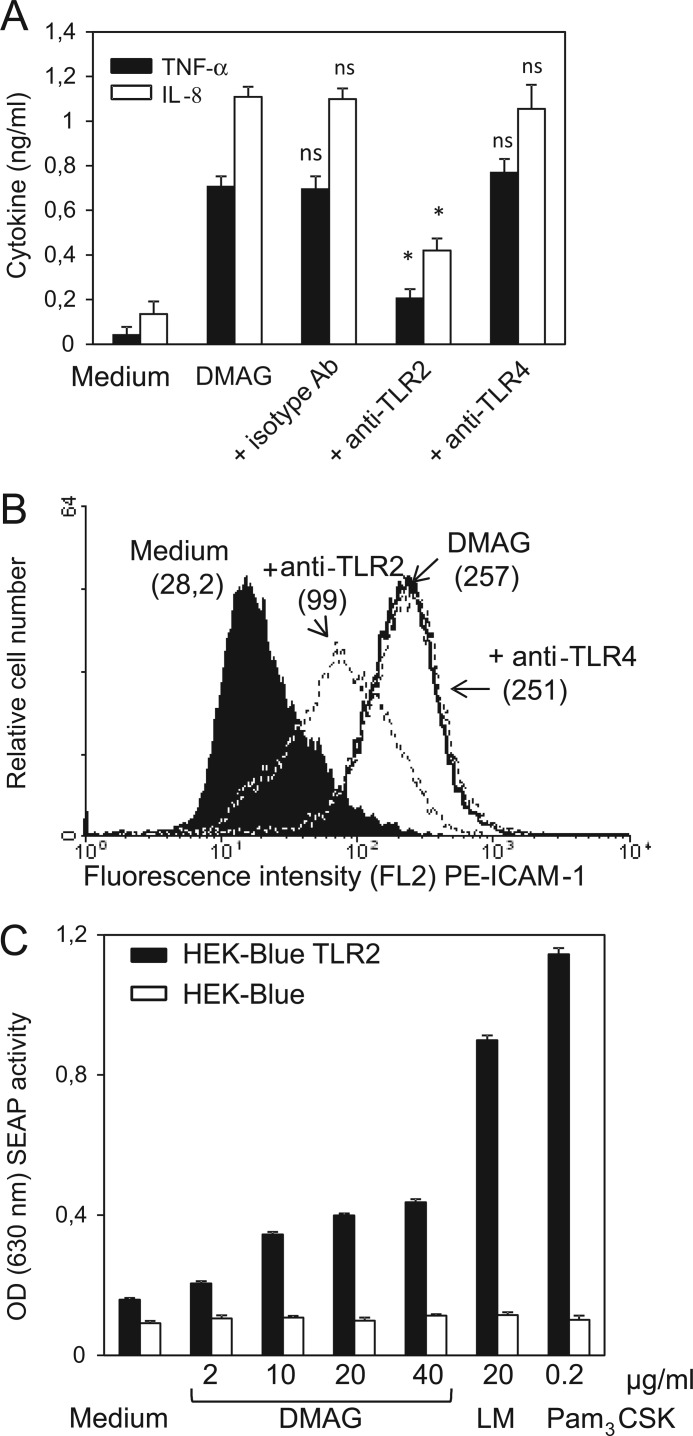

Macrophage Activation and Proinflammatory-induced Response by DMAG Are Dependent on TLR-2

TLRs are known as key receptors for promoting the inflammatory immune response during microbial infection (55). TLR2 recognizes mycolic acid-containing lipids, such as TDM, in combination with other receptors (MARCO/CD14) present on macrophages (26). We next investigated the possible participation of TLR2 and/or TLR4 in the signaling pathway leading to THP-1 activation by Mma_DMAG. Production of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines by THP-1 cells as well as expression of cell surface receptors were followed by incubating cells with specific neutralizing TLR2 or TLR4 antibodies or their corresponding isotype control antibodies. As shown in Fig. 5A, pretreatment with anti-TLR2 antibodies, but not with anti-TLR4 or isotype control antibodies, was accompanied by a strong decrease in TNF-α and IL-8 secretion (with 71 and 62% inhibition in the presence of anti-TLR2 antibodies, respectively). Consistent with these findings, neutralization of TLR2 was also associated with a decrease in ICAM-1 cell surface expression induced by Mma_DMAG (Fig. 5B). This effect was not observed when cells were pretreated with anti-TLR4 antibodies.

FIGURE 5.

TLR2-dependent activity of Mma_DMAG. Differentiated THP-1 cells were pretreated with 15 μg/ml concentrations of either anti-TLR2, anti-TLR4, or control isotype monoclonal antibodies (Ab) for 30 min at 37 °C in 2% FCS-RPMI 1640 medium before the addition of 20 μg/ml Mma_DMAG. A, supernatants were collected after 6 or 24 h and assayed by ELISA for both TNF-α and IL-8 productions. Values represent the means ± S.D. of triplicates. Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t test. Asterisks indicate values of p < 0.02; ns, nonspecific p > 0.05. B, cell surface expression of ICAM-1 was determined by flow cytometry after stimulation of differentiated THP-1 cells for 24 h. The shown data are representative of at least of three independent experiments. C, stimulation of HEK-Blue-hTLR2 cell line by Mma_DMAG is shown. The HEK-Blue-hTLR2 and HEK-blue-Null1 (control) cell lines were stimulated with various Mma_DMAG concentrations. Lipopeptide Pam3CSK4 (200 ng/ml) and LM (20 μg/ml) were also included as TLR2 agonists. Cell activation was determined after 20 h of incubation by measuring SEAP activity at OD630 using the QUANTI-Blue detection assay. Results are expressed as means ± S.D. of triplicates and are representative of three independent experiments. Statistical significance between Mma_DMAG-treated and unstimulated HEK-Blue-hTLR2 cells was determined using Student's t test (p values were <0.03).

To further confirm the involvement of TLR2 in Mma_DMAG-induced activity, HEK293-TLR2 cells co-transfected with both the human TLR2 gene and the SEAP-inducible reporter system were stimulated for 20 h with Mma_DMAG. Lipopeptide Pam3CSK4 and LM were included as positive TLR2 agonists. As judged by QUANTI-Blue detection, Mma_DMAG exhibited dose-dependent NF-κB activation in HEK293-TLR2 cells (Fig. 5C). As expected, no induction was observed after stimulation of the parental HEK-Blue Null1 cells, thus demonstrating the specificity of the TLR2-dependent effect. It is noteworthy that the level of NF-κB activation observed was lower with Mma_DMAG than with LM or Pam3CSK4. Taken together, these results clearly reveal that Mma_DMAG exerts its effects through ligation to TLR2, leading to the production of a prominent proinflammatory response and to macrophage activation.

Transcriptomic Analyses of Mma_DMAG-stimulated THP-1 Macrophages

To gain insight toward the mechanisms by which DMAG interferes with the host immune system, THP-1 gene expression was monitored at a transcriptional scale using whole human genome cDNA microarray after stimulation with Mma_DMAG. The binary logarithm of Mma_DMAG-stimulated cells versus nontreated cells ratios were considered, with adjusted p values <0.01. The statistical transcriptomic analysis from two independent experiments showed the alteration of 547 genes after 8 h of incubation (supplemental Table S1). The selected genes were classified in functional groups and according to gene ontology using PANTHER (supplemental Table S2). Compared with a NCBI Homo sapiens reference list, the differentially regulated genes (corresponding to significant increased or decreased transcription levels) revealed that some biological processes were significantly over-represented (p value < 0.05). This was particularly the case for processes related to immune system (167 genes of 547), response to stimuli, cell surface receptor-linked signal transduction pathways and intracellular signaling cascade, cell communication, metabolic systems (particularly nucleic acid and lipid metabolisms), and developmental stages. Interestingly, several overexpressed genes involved in immune responses were relevant to macrophage activation, cell adhesion, endocytosis, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and response to stress and to IFN-γ. Cell signaling pathways analysis led to the identification of genes involved in inflammatory mechanisms mediated by chemokines/cytokines and TLR, apoptosis regulation (pro- or anti-), integrin and heterotrimeric G protein signaling pathways, and oxidative stress response as well as growth factors activities. Molecular function and protein class Gene ontology analyses indicated the enrichment of chemokines/cytokines, signaling molecules, transcription factors, enzymes (transferase, hydrolase, kinase, phosphatase, oxygenase), and receptors activities. As reported in Table 2, IL-8, TNF-α, and IL-1β were among the most highly expressed gene candidates (up-regulated 17, 10, and 45 times, respectively, compared with the nontreated macrophages), thus confirming our ELISA results (Fig. 3). In addition, several other genes from the “cytokine/chemokine” family were strongly up-regulated with a sharp preference for the CCL and CXCL chemotactic factors. Several cell surface markers were also strongly up-regulated, including ICAM-1 and CD40 (18 and 5 times, respectively), in agreement with their increased cell surface detection by flow cytometry (Fig. 4). Up-regulation of genes related to leukocyte recruitment and activation and to complement activation (pentraxin PTX3, C3AR1) is also of special interest. Moreover, genes coding for enzymes participating in the remodeling of the host matrix, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1, MMP-9), were found to be up-regulated along with others related to redox process (SOD2, TXNRD1, CYP19A1, HMOX1) and those involved in central metabolic pathways, post-translational modification of glycans (CHST2, CHST7 sulfotransferases and Neu4 sialidase) or in the catabolism of tryptophan (IDO1). Interestingly, a large proportion of these up-regulated genes are known to be overexpressed during mycobacterial infections (57, 58). In addition, several genes down-regulated after exposure of macrophages to Mma_DMAG (supplemental Table S1) may be relevant to mycobacterial pathogenesis. These include lipidic antigen presentation to CD1d (log2 ratio = −2.03, p < 0.00076), NOD-like receptor family CARD domain containing 3 (called NLRC3, log2 ratio = −1.38, p < 0.006), apoptosis inhibitory protein (NAIP with log2 ratio = −1.38, p < 0.0013), and CXCR2 and CX3CR1 chemokine receptors (log2 ratio = −1.52, p < 0.008, log2 ratio = −2.02, p < 0.0006) as well as ADAM metallopeptidase (ADAMTS5, log2 ratio = −1.49, p < 0.0018) or serpin peptidase inhibitor clade B member2 (SERPINB2, log2 ratio = −3.19, p < 0.0002).

TABLE 2.

Microarray analyses; genes up-regulated in human macrophages-like THP1 cells after stimulation for 8 h with Mma_DMAG

The complete list of altered gene expression was available in supplemental Table S1.

| Gene | Description | Log2 ratioa |

|---|---|---|

| Cell surface antigen | ||

| ICAM1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 | 4.20 |

| VCAM1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 | 2.84 |

| CD40 | CD40 molecule, TNF receptor superfamily member 5 | 2.49 |

| CD83 | CD83 molecule | 3.06 |

| CD44 | CD44 molecule (Indian blood group) | 2.07 |

| ITGB8 | Integrin, β8 | 2.04 |

| SLAMF7 | Signaling lymphocytic activation molecule family member 7 | 3.86 |

| Protease/metalloproteinase | ||

| MMP1 | Matrix metallopeptidase 1 (interstitial collagenase) | 4.95 |

| MMP9 | Matrix metallopeptidase9 (gelatinase B, 92-kDa gelatinase, 92-kDa type IV collagenase) | 3.25 |

| PCSK5 | Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 5 | 2.91 |

| Chemokines-cytokines | ||

| CCL8 (MCP-2) | Chemokine ligand 8 | 5.94 |

| CCL2 (MCP-1) | Chemokine ligand 2 | 4.91 |

| CXCL2 (MIP-2) | Chemokine ligand 2 | 4.62 |

| CXCL1 | Chemokine ligand 1 | 4.31 |

| CCL4 (MIP-1) | Chemokine ligand 4 | 4.07 |

| CCL20 | Chemokine ligand 20 | 4.00 |

| CXCL11 | Chemokine ligand 11 | 3.70 |

| CXCL3(GRO) | Chemokine ligand 3 | 3.65 |

| CXCL10 | Chemokine ligand 10 | 3.58 |

| CCL7 | Chemokine ligand 7 | 3.41 |

| CCL3L3 | Chemokine ligand 3-like 3 | 3.37 |

| CXCL9 | Chemokine ligand 9 | 2.02 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin 8 | 4.11 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1, β | 5.54 |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor | 3.33 |

| IL-1α | Interleukin 1, α | 2.42 |

| Cytokine receptors | ||

| CCR7 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 7 | 4.18 |

| IL18RAP | Interleukin 18 receptor accessory protein | 3.17 |

| CMKLR1 | Chemokine-like receptor 1 | 2.37 |

| Apoptosis | ||

| BCL2A1 | BCL2-related protein A1 | 3.34 |

| TNFAIP3 | Tumor necrosis factor, α-induced protein 3 | 3.25 |

| IER3 | Immediate early response 3 | 3.33 |

| Redox-enzymes | ||

| CYP19A1 | Cytochrome P450, family 19, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 | 3.27 |

| SOD2 | Superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial | 3.18 |

| Cell signaling pathways/nuclear factors | ||

| RGS1 | Regulator of G-protein signaling 1 | 4.01 |

| NR4A3 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 3 | 3.92 |

| RND3 | Rho family GTPase 3 | 3.70 |

| TNIP3 | TNFAIP3 interacting protein 3 | 3.23 |

| TNFAIP3 | Tumor necrosis factor, α-induced protein 3 | 3.25 |

| RCAN1 | Regulator of calcineurin 1 | 3.16 |

| SOCS3 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 | 3.09 |

| DUSP1 | Dual specificity phosphatase 1 | 3.04 |

| RGS16 | Regulator of G-protein signaling 16 | 2.96 |

| STAT4 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 | 2.73 |

| ATF3 | Activating transcription factor 3 | 2.75 |

| TRAF1 | TNF receptor-associated factor 1 | 2.68 |

| BCL3 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 3 | 2.28 |

| SPHK1 | Sphingosine kinase 1 | 2.16 |

| NFKB2 | Nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer | 2.10 |

| NFKB1 | Nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer | 2.19 |

| NFKBIZ | Nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer | 2.46 |

| IFN-inducible protein | ||

| IFIT3 | Interferon-induced protein | 3.24 |

| IFIT2 | Interferon-induced protein | 2.50 |

| IFIT1 | Interferon-induced protein | 2.4 |

| IFIT5 | Interferon-induced protein | 2.17 |

| Transporters/channels | ||

| AQP9 | Aquaporin 9 | 3.66 |

| SLC7A11 | Solute carrier family 7 | 2.51 |

| SLC7A11 | ATPase, Ca2+ transporting, plasma membrane 1 | 2.27 |

| Lipidb and amino acidc metabolism | ||

| FABP4b | Fatty acid-binding protein 4 | 3.38 |

| AGPAT9b | 1-Acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase 9 | 3.13 |

| PTGS2b | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | 3.17 |

| MGLLb | Monoglyceride lipase | 3.07 |

| PLA2G7b | Phospholipase A2, group VII | 2.78 |

| ACSL1b | Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 1 | 2.36 |

| LRP12b | Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 12 | 2.11 |

| IDO1c | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (Trp catabolism) | 2.78 |

| KYNUc | Kynureninase (l-kynurenine hydrolase) | 2.36 |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | ||

| CHST7 | Carbohydrate (N-acetylglucosamine 6-O) sulfotransferase 7 | 2.42 |

| CHST2 | Carbohydrate (N-acetylglucosamine-6-O) sulfotransferase 2 | 2.12 |

| NEU4 | Sialidase 4 | 2.26 |

| SDC4 | Syndecan 4 | 2.22 |

| Nucleic metabolism | ||

| PDE4B | Phosphodiesterase 4B, cAMP-specific | 2.59 |

| NTSE | 5′-Nucleotidase, ecto (CD73) | 2.35 |

| NAMPT | Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase | 2.27 |

| ADORA2A | Adenosine A2a receptor | 2.85 |

| ADAD2 | Adenosine deaminase domain containing 2 | 2.83 |

| Miscellaneous | ||

| EBI3 | Epstein-Barr virus-induced 3 | 3.65 |

| EGR2 | Early growth response 2 | 3.29 |

| SERPINE2 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, serpin peptidase inhibitor, cladeE (nexin, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1), member 2 | 3.24 |

| HBEGF | Heparin binding EGF-like growth factor | 2.03 |

a Binary log ratio of altered gene expression according to microarray analysis of macrophages after exposure for 8 h with DMAG compared to unstimulated cells. Results with a log2 ratio >2 are shown and are representative of two independent experiments.

b Genes related to lipid metabolism.

c Genes related to amino acid metabolism.

In conclusion, the microarray analysis not only confirms the proinflammatory-inducing activity of Mma_DMAG but also suggests that Mma_DMAG affects expression of a large panoply of macrophage genes that are connected to the immunopathogenesis of mycobacterial infections, with important pathways related to signaling events, inflammation, lipid antigen presentation, or tissue destruction.

DISCUSSION

Based on structural analogy with mAGP and studies on the action of anti-tubercular drugs, a metabolic relationship between DMAG from M. bovis BCG and mAGP has recently been highlighted (33). However, neither the metabolic pathway leading to DMAG nor its potential biological properties has been reported yet. We present here the detailed structural elucidation of the 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro (DMAG) in Mma and provide the first biological functions of this cell wall-associated glycolipid. A combination of NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry revealed the presence of three mycolate subclasses (α-, keto-, and methoxy-mycolic acids) in Mma_DMAG (33). Furthermore, in contrast to M. tuberculosis that contains a ratio of α-mycolates/oxygenated mycolates (i.e. methoxy- and keto-mycolates) of 1/1 (59), oxygenated mycolates are predominant in Mma_DMAG. It is noteworthy that exogenous glycerol is required to stimulate DMAG production (33) as reported earlier for another glycolipid, GroMM (60). These observations have led to the speculation that DMAG may result from the catabolism of already-synthesized mAGP following the action of an arabinanase and subsequent transfer onto an endo- or exogenous substrate, such as glycerol (33). During infection of foamy macrophages, dynamic changes in the glycolipid composition of the mycobacterial cell wall have been reported to occur (61, 62). That these mechanisms may be responsible in vivo for the production of DMAG during infection remains, however, to be demonstrated.

Considering the high structural analogy between DMAG and TDM as well as its localization to the mycobacterial cell wall (presumably surface-exposed), we reasoned that DMAG may share with TDM several traits that are relevant to mycobacterial pathogenesis, such as proinflammatory cytokine production and formation of granuloma and tissue-destructive lesions (63). Mma_DMAG was found to stimulate a potent macrophage inflammatory response. This contrasts to LOS from Mma (40) that were found to inhibit the secretion of TNF-α from LPS-stimulated macrophages (45). The Mma_DMAG-mediated inflammatory response was dependent at least partly on ligation to TLR2. This interaction results in the induction of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8 secretion and triggers macrophage activation by inducing expression of cell surface antigens such as ICAM-1 or CD40. These results were subsequently extended at a whole transcriptomic level. Microarray studies performed on macrophages exposed to DMAG indicate that many genes participating in inflammation or chemotaxis are up-regulated, which are relevant to granuloma formation. Altogether, these factors are crucial in tipping the balance between intracellular survival of bacteria and their eventual elimination by antimicrobial mechanisms of activated macrophages (64, 65). Our findings emphasize a potential function of DMAG in modulation of the host immune response, as previously suggested by Honda et al. (34). Indeed, the presence of a humoral anti-DMAG response has been detected in patients infected by M. avium or M. tuberculosis, suggesting that DMAG may be regarded as an immunogenic glycolipid (34). Given the high structural relatedness with other mycolic acid-bearing molecules, it is not surprising that DMAG triggers activity on immune cells. Indeed, arabino-mycolates obtained by acid hydrolysis from the cell-wall skeleton of M. bovis BCG (BCG-CWS) (66) as well as synthesized arabino-mycolates (67) have been shown to induce TNF-α production in murine macrophage cell lines. Moreover, these compounds, described as potent adjuvant in vivo, enhanced delayed type hypersensitivity reactions against inactivated tumor cells (66). A 5-mycoloyl diarabinoside isolated from the cell wall of M. tuberculosis was also reported to act as potential endotoxins through an inhibitory activity on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (68). Arabinosylated mycolic acid isolated from M. bovis BCG were proposed to participate to acute inflammatory response, essentially as a consequence of a constant and massive recruitment of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (69). Furthermore, cis- or trans-cyclopropanated mycolic acids in TDM were found to directly regulate the innate immune activation of macrophages by modulating TNF-α production (29, 71). Interestingly, the molecular structure of mycolic acid seems to influence the pattern of inflammatory response (72). Thus, TDM lacking trans-cyclopropane rings purified from a M. tuberculosis cyclopropane-mycolic acid synthase 2 (cmaA2) null mutant was 5 times more potent in stimulating macrophages than TDM obtained from the wild-type strain (29, 71). In contrast, trans-cyclopropanation of mycolic acids on TDM suppresses M. tuberculosis-induced inflammation and virulence (29, 71). These authors have also suggested that cis-cyclopropanation of TDM was critical to its proinflammatory activity. Furthermore, a mutant of MmaA4 gene (methoxy mycolic acid synthase 4) was associated with higher production of TNF-α and IL-12 compared with the wild-type M. tuberculosis strain (73). A recent study also emphasized the fact that free methoxy- and keto-mycolic acid with cis-cyclopropane stereochemistry elicited high and mild inflammatory responses, respectively, whereas α-mycolates were inactive (72). Therefore, the structure of three subclasses of cis-cyclopropanated mycolates (keto, methoxy, and α) found in Mma_DMAG and the lack of trans-cyclopropanation are in favor of our biological results, demonstrating that DMAG may display an inflammatory pattern on the immune innate response. From a mechanistic point of view, our results indicate that DMAG-induced activation of macrophages is dependent on TLR2, presumably through an interaction with mycolic acids, as reported for arabino-mycolates of M. bovis BCG (BCG-CWS) (66). However, because both TNF-α and IL-8 responses were partially inhibited in the presence of neutralizing TLR-2 antibodies, one can presume that host recognition of DMAG involves additional receptors. This was reported for TDM, which binds to multiple receptors, including TLR2/MARCO/CD14 complex or the Mincle C-type lectin (25–28). However, that DMAG binds to Mincle is very unlikely, as the trehalose unit of TDM has been demonstrated to be crucial to the binding of TDM to Mincle (25, 27–29).

Besides TDM and arabinose monomycolate, other glycolipids display structural similarity to DMAG, such GroMM. GroMM purified from M. tuberculosis was presented as an antigenic glycolipid, potent stimulator of CD1b-restricted CD4+ T cell clones (47). Presentation of free mycolates, GMM, or GroMM by CD1 molecules triggers the T cell responses, leading to the development of acquired immunity against mycobacteria (61, 74, 75). GroMM induces eosinophilic hypersensitivity responses in guinea pigs, which led the authors to predict that the host response to this lipid produced by dormant mycobacteria contributes to their survival in the host through the expression of T helper (Th)2-type cytokines, such as IL-5 and IL-10 (60). GroMM biosynthesis pathway has not been elucidated yet; thus, the metabolic relationship between DMAG and GroMM cannot be inferred. Interestingly, we established that activation of differentiated THP-1 cells by Mma_DMAG was accompanied by the down-regulation of CD1d transcript, an antigen restricted to natural killer T cells activation. Although this result has to be confirmed experimentally, it suggests that DMAG could also modulate the effectiveness of lipidic antigen presentation to natural killer T cells. In agreement with our results, Roura-Mir et al. (76) previously demonstrated that the mycobacterial cell wall lipids of M. tuberculosis that activate human monocytes through TLR2 up-regulated CD1a, CD1b, and CD1c gene and protein expression, whereas CD1d transcripts decreased on the first day after exposure to the lipids.

Overall, this study illustrates the broad inflammatory activity of Mma_DMAG. As such, it describes a new partner in the growing list of mycobacterial cell wall components able to modulate the host immune response. Whether this activity ultimately leads to the recruitment of immune cells, eventually conditioning the outcome of the infection, remains to be established. Future work will be dedicated to address the in vivo biological relevance of DMAG activity and its potential participation in formation and/or maintenance of the granuloma. This is now possible thanks to the use of zebrafish embryos, which enable the investigation the Mma infection process at a spatiotemporal level (3, 77). As an example of application, phagocyte recruitments and granuloma formation could be readily visualized in real time by intravenously injecting Mma_DMAG-conjugated fluorescent beads in zebrafish embryos.

Recent reports have highlighted the possibility of producing novel classes of chemically defined lipid adjuvants (66, 70). For instance, the immunostimulatory activities of arabino-mycolates (65) and GroMM from M. bovis BCG (70) have been proposed to enhance the activity of new vaccine formulations. Based on the structural similarity between these compounds and DMAG, one can presume that DMAG elicits a potent adjuvant activity to be exploited, although this perspective of application requires a more extensive characterization of DMAG immunostimulatory properties.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Marlène Mortuaire for technical advice in cell culture. We are also grateful to W. Bitter and A. van der Sar for kindly providing Mma7.

This work was supported by National Research Agency Grant ANR-05-MIIM-025 (to Y. G. and L. K.) and a grant from the Ministère de l'Enseignement Supérieur (to Y. R.).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

- Mma

- M. marinum

- DMAG

- dimycolyl-diarabino-glycerol

- LM

- lipomannan

- TDM

- trehalose-dimycolate

- GMM

- glucose-monomycolate

- GroMM

- glycerol monomycolate

- mAGP

- mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan

- TLR

- toll-like-receptor

- ICAM-1

- intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- SEAP

- secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase

- TOCSY

- two-dimensional total correlation spectroscopy

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum correlation

- LOS

- lipooligosaccharide

- PE

- phosphatidylethanolamine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Daffé M., Draper P. (1998) The envelope layers of mycobacteria with reference to their pathogenicity. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 39, 131–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stinear T. P., Seemann T., Harrison P. F., Jenkin G. A., Davies J. K., Johnson P. D., Abdellah Z., Arrowsmith C., Chillingworth T., Churcher C., Clarke K., Cronin A., Davis P., Goodhead I., Holroyd N., Jagels K., Lord A., Moule S., Mungall K., Norbertczak H., Quail M. A., Rabbinowitsch E., Walker D., White B., Whitehead S., Small P. L., Brosch R., Ramakrishnan L., Fischbach M. A., Parkhill J., Cole S. T. (2008) Insights from the complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium marinum on the evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Genome Res. 18, 729–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ramakrishnan L. (1994) Using Mycobacterium marinum and its hosts to study tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 62, 3222–3229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Petrini B. (2006) Mycobacterium marinum. Ubiquitous agent of waterborne granulomatous skin infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 25, 609–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Swaim L. E., Connolly L. E., Volkman H. E., Humbert O., Born D. E., Ramakrishnan L. (2006) Mycobacterium marinum infection of adult zebrafish causes caseating granulomatous tuberculosis and is moderated by adaptive immunity. Infect. Immun. 74, 6108–6117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gao L. Y., Groger R., Cox J. S., Beverley S. M., Lawson E. H., Brown E. J. (2003) Transposon mutagenesis of Mycobacterium marinum identifies a locus linking pigmentation and intracellular survival. Infect. Immun. 71, 922–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tobin D. M., Ramakrishnan L. (2008) Comparative pathogenesis of Mycobacterium marinum and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Microbiol. 10, 1027–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davis J. M., Clay H., Lewis J. L., Ghori N., Herbomel P., Ramakrishnan L. (2002) Real-time visualization of mycobacterium-macrophage interactions leading to initiation of granuloma formation in zebrafish embryos. Immunity 17, 693–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cosma C. L., Humbert O., Ramakrishnan L. (2004) Superinfecting mycobacteria home to established tuberculous granulomas. Nat. Immunol. 5, 828–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cosma C. L., Swaim L. E., Volkman H., Ramakrishnan L., Davis J. M. (2006) Zebrafish and frog models of Mycobacterium marinum infection. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol., Chapter 10, Unit 10B.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Volkman H. E., Clay H., Beery D., Chang J. C., Sherman D. R., Ramakrishnan L. (2004) Tuberculous granuloma formation is enhanced by a mycobacterium virulence determinant. PLoS Biol. 2, e367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clay H., Davis J. M., Beery D., Huttenlocher A., Lyons S. E., Ramakrishnan L. (2007) Dichotomous role of the macrophage in early Mycobacterium marinum infection of the zebrafish. Cell Host Microbe 2, 29–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tobin D. M., Vary J. C., Jr., Ray J. P., Walsh G. S., Dunstan S. J., Bang N. D., Hagge D. A., Khadge S., King M. C, Hawn T. R., Moens C. B, Ramakrishnan L. (2010) The lta4h locus modulates susceptibility to mycobacterial infection in zebrafish and humans. Cell 140, 717–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davis J. M., Ramakrishnan L. (2009) The role of the granuloma in expansion and dissemination of early tuberculosis infection. Cell 136, 37–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kremer L., Baulard A., Besra G. S. (2000) in Molecular Genetics of Mycobacteria (Hatfull G. F., Jacobs W. R., Jr., ed.) pp. 173–190, American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D. C [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ryll R., Kumazawa Y., Yano I. (2001) Mycobacterial cord factor, but not sulfolipid, causes depletion of NKT cells and up regulation of CD1d1 on murine macrophages. Microbiol. Immunol. 45, 801–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chatterjee D., Khoo K. H. (2001) The surface of glycopeptidolipids of mycobacteria. Structures and biological properties. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58, 2018–2042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Briken V., Porcelli S. A., Besra G. S., Kremer L. (2004) Mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan and related lipoglycans from biogenesis to modulation of the immune response. Mol. Microbiol. 53, 391–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Karakousis P. C., Bishai W. R., Dorman S. E. (2004) Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell envelope lipids and the host immune response. Cell. Microbiol. 6, 105–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Astarie-Dequeker C., Nigou J., Passemar C., Guilhot C. (2010) in Drug Discovery Today: Disease Mechanisms, 7th Ed., pp. e33-e41, Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hunter R. L., Olsen M. R., Jagannath C., Actor J. K. (2006) Multiple roles of cord factor in the pathogenesis of primary, secondary, and cavitary tuberculosis, including a revised description of the pathology of secondary disease. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 36, 371–386 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rajni, Rao N., Meena L. S. (2011) Biosynthesis and virulent behavior of lipids produced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. LAM and cord factor. An Overview. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 274693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Geisel R. E., Sakamoto K., Russell D. G., Rhoades E. R. (2005) In vivo activity of released cell wall lipids of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin is due principally to trehalose mycolates. J. Immunol. 174, 5007–5015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Welsh K. J., Abbott A. N., Hwang S. A., Indrigo J., Armitige L. Y., Blackburn M. R., Hunter R. L, Jr., Actor J. K. (2008) A role of TNF-α, complement C5, and IL-6 in the initiation and development of the mycobacterial cord factor trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate induced granulomatous response. Microbiology 154, 1813–1824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yamasaki S., Ishikawa E., Sakuma M., Hara H., Ogata K., Saito T. (2008) Mincle is an ITAM-coupled activating receptor that senses damaged cells. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1179–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bowdish D. M., Sakamoto K., Kim M. J., Kroos M., Mukhopadhyay S., Leifer C. A., Tryggvason K., Gordon S., Russell D. G. (2009) MARCO, TLR2, and CD14 are required for macrophage cytokine responses to mycobacterial trehalose dimycolate and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ishikawa E., Ishikawa T., Morita Y. S., Toyonaga K., Yamada H., Takeuchi O., Kinoshita T., Akira S., Yoshikai Y., Yamasaki S. (2009) Direct recognition of the mycobacterial glycolipid, trehalose dimycolate by C-type lectin Mincle. J. Exp. Med. 206, 2879–2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matsunaga I., Moody D. B. (2009) Mincle is a long sought receptor for mycobacterial cord factor. J. Exp. Med. 206, 2865–2868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rao V., Gao F., Chen B., Jacobs W. R., Jr., Glickman M. S. (2006) Trans cyclopopanation of mycolic acids on trehalose dimycolate suppresses Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced inflammation and virulence. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 1660–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fujita Y., Okamoto Y., Uenishi Y., Sunagawa M., Uchiyama T., Yano I. (2007) Molecular and supramolecular structure related differences in toxicity and granulomatogenic activity of mycobacterial cords factor in mice. Microb. Pathog. 43, 10–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Watanabe M., Kudoh S., Yamada Y., Iguchi K., Minnikin D. E. (1992) A new glycolipid from Mycobacterium avium-Mycobacterium intracellulare complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1165, 53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Watanabe M., Aoyagi Y., Ohta A., Minnikin D. E. (1997) Structures of phenolic glycolipids from Mycobacterium kansasii. Eur. J. Biochem. 248, 93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rombouts Y., Brust B., Ojha A. K., Maes E., Coddeville B., Elass-Rochard E., Kremer L., Guerardel Y. (2012) Exposure of mycobacteria to cell wall inhibitory drugs decreases production of arabinoglycerolipid related to mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 11060–11069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Honda I., Kawajiri K., Watanabe M., Toida I., Kawamata K., Minnikin D. E. (1993) Evaluation of the use of 5-mycoloyl-β-arabinofuranosyl-(1–2)-5-mycoloyl-α-arabinofuranosyl-(1–1′)-glycerol in serodiagnosis of Mycobacterium aviumintracellulare complex infection. Res. Microbiol 144, 229–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Puttinaowarat S., Thompson K., Lilley J., Adams A. (1999) Characterization of Mycobacterium spp isolated from fish by pyrolysis mass spectrometry (PyMS) analysis. AAHRI (Aquatic Animal Health Research Institute) Newslett. 8, 4–8 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burguière A., Hitchen P. G., Dover L. G., Kremer L., Ridell M., Alexander D. C., Liu J., Morris H. R., Minnikin D. E., Dell A., Besra G. S. (2005) LosA, a key glycosyltransferase involved in the biosynthesis of a novel family of glycosylated acyltrehalose lipooligosaccharides from Mycobacterium marinum. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42124–42133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guerardel Y., Maes E., Elass E., Leroy Y., Timmerman P., Besra G. S, Locht C., Strecker G., Kremer L. (2002) Structural study of lipomannan and lipoarabinomannan from Mycobacterium chelonae. Presence of unusual components with alpha 1,3-mannopyranose side chains. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 30635–30648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kremer L., Guérardel Y., Gurcha S. S., Locht C., Besra G. S. (2002) Temperature-induced changes in the cell-wall components of Mycobacterium thermoresistibile. Microbiology 148, 3145–3154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dover L. G., Alahari A., Gratraud P., Gomes J. M., Bhowruth V., Reynolds R. C., Besra G. S., Kremer L. (2007) EthA, a common activator of thiocarbamide-containing drugs acting on different mycobacterial targets. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 1055–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rombouts Y., Elass E., Biot C., Maes E., Coddeville B., Burguière A., Tokarski C., Buisine E., Trivelli X., Kremer L., Guérardel Y. (2010) Structural analysis of an unusual bioactive N-acylated lipo-oligosaccharide LOS-IV in Mycobacterium marinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 16073–16084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ihaka R., Gentleman R. R. (1996) A language for data analysis and graphics. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 5, 299–314 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Smyth G. K., Yang Y. H., Speed T. (2003) Statistical issues in cDNA microarray data analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 224, 111–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yang Y. H., Dudoit S., Luu P., Lin D. M., Peng V., Ngai J., Speed T. P. (2002) Normalization for cDNA microarray data. A robust composite method addressing single and multiple slide systematic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lönnstedt I., Speed T. P. (2002) Replicated microarray data. Statistica Sinica 12, 31–46 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rombouts Y., Burguière A., Maes E., Coddeville B., Elass E., Guérardel Y., Kremer L. (2009) Mycobacterium marinum lipooligosaccharides are unique caryophyllose-containing cell wall glycolipids that inhibit tumor necrosis factor α secretion in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 20975–20988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Daffé M., Lanéelle M. A., Lacave C. (1991) Structure and stereochemistry of mycolic acids of Mycobacterium marinum and Mycobacterium ulcerans. Res. Microbiol. 142, 397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Layre E., Collmann A., Bastian M., Mariotti S., Czaplicki J., Prandi J., Mori L., Stenger S., De Libero G., Puzo G., Gilleron M. (2009) Mycolic acids constitute a scaffold for mycobacterial lipid antigens stimulating CD1-restricted T cells. Chem. Biol. 16, 82–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chensue S. W., Warmington K. S, Ruth J. H., Lincoln P., Kunkel S. L. (1995) Cytokine function during mycobacterial and schistosomal antigen-induced pulmonary granuloma formation. Local and regional participation of IFN-γ, IL-10, and TNF. J. Immunol. 154, 5969–5976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Algood H. M., Lin P. L., Flynn J. L. (2005) TNF α and chemokine interactions in the formation and maintenance of granulomas in tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41, S189–S193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chensue S. W., Davey M. P., Remick D. G., Kunkel S. (1986) Release of interleukin-1 by peripheral blood mononuclearcells in patients with tuberculosis and active inflammation. Infect. Immun. 52, 341–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kleinnijenhuis J., Joosten L. A., van de Veerdonk F. L., Savage N., van Crevel R., Kullberg B. J., van der Ven A., Ottenhoff T. H., Dinarello C. A., van der Meer J. W., Netea M. G. (2009) Transcriptional and inflammasome-mediated pathways for the induction of IL-1β production by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 39, 1914–1922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vignal C., Guérardel Y, Kremer L, Masson M, Legrand D, Mazurier J, Elass E. (2003) Lipomannans, but not lipoarabinomannans, purified from Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium kansasii induce TNF and IL-8 secretion by a CD14-Toll like receptor 2-dependent mechanisms. J. Immunol. 171, 2014–2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Estrella J. L, Kan-Sutton C., Gong X., Rajagopalan M., Lewis D. E., Hunter R. L., Eissa N. T., Jagannath C. (2011) A novel in vitro human macrophage model to study the persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis using vitamin D(3) and retinoic acid-activated THP-1 macrophages. Front. Microbiol. 2, 67–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gilleron M., Nigou J., Nicolle D., Quesniaux V., Puzo G. (2006) The acylation state of mycobacterial lipomannans modulates innate immunity response through toll-like receptor 2. Chem. Biol. 13, 39–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Quesniaux V. J., Nicolle D. M., Torres D., Kremer L., Guérardel Y., Nigou J., Puzo G., Erard F., Ryffel B. (2004) Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2)-dependent-positive and TLR2-independent-negative regulation of proinflammatory cytokines by mycobacterial lipomannans. J. Immunol. 172, 4425–4434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lebedeva T., Dustin M. L., Sykulev Y. (2005) ICAM-1 co-stimulates target cells to facilitate antigen presentation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 17, 251–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nau G. J., Richmond J. F., Schlesinger A., Jennings E. G., Lander E. S., Young R. A. (2002) Human macrophage activation programs induced by bacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 1503–1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thuong N. T., Dunstan S. J., Chau T. T., Thorsson V., Simmons C. P., Quyen N. T., Thwaites G. E., Thi Ngoc Lan N., Hibberd M., Teo Y. Y., Seielstad M., Aderem A., Farrar J. J., Hawn T. R. (2008) Identification of tuberculosis susceptibility genes with human macrophage gene expression profiles. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Watanabe M., Aoyagi Y., Ridell M., Minnikin D. E. (2001) Separation and characterization of individual mycolic acids in representative mycobacteria. Microbiology 147, 1825–1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hattori Y., Matsunaga I., Komori T., Urakawa T., Nakamura T., Fujiwara N., Hiromatsu K., Harashima H., Sugita M. (2011) Glycerol monomycolate, a latent tuberculosis-associated mycobacterial lipid, induces eosinophilic hypersensitivity responses in guinea pigs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 409, 304–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ehrt S., Schnappinger D. (2007) Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Lipids inside and out. Nat. Med. 13, 284–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pandey A. K., Sassetti C. M. (2008) Mycobacterial persistence requires the utilization of host cholesterol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4376–4380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Khan A. A., Stocker B. L., Timmer M. S. (2012) Trehalose glycolipids synthesis and biological activities. Carbohydr. Res. 356, 25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Flynn J. L., Chan J. (2001) Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19, 93–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Raja A. (2004) Immunology of tuberculosis. Indian J. Med. Res. 120, 213–232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Miyauchi M., Murata M., Shibuya K., Koga-Yamakawa E., Uenishi Y., Kusunose N., Sunagawa M., Yano I., Kashiwazaki Y. (2011) Arabino-mycolates derived from the cell-wall skeleton Mycobacterium bovis BCG as a prominent structure for recognition by host immunity. Drug Discov. Ther. 5, 130–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ishiwata A., Akao H., Ito Y., Sunagawa M., Kusunose N., Kashiwazaki Y. (2006) Synthesis and TNF-α inducing activities of mycolyl-arabinan motif of mycobacterial cell wall components. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14, 3049–3061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Rouanet J. M., Laneelle G. (1983) Mycobacteria arabinolipids as potential endotoxins. Their activity on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Ann. Microbiol. (Paris) 134B, 233–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Silva C. L. (1985) Inflammation induced by mycolic acid-containing glycolipids of Mycobacterium bovis (BCG). Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 18, 327–335 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Andersen C. A., Rosenkrands I., Olsen A. W., Nordly P., Christensen D., Lang R., Kirschning C., Gomes J. M., Bhowruth V., Minnikin D. E., Besra G. S., Follmann F., Andersen P., Agger E. M. (2009) Novel generation mycobacterial adjuvant based on liposome-encapsulated monomycoloyl glycerol from Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin. J. Immunol. 183, 2294–2302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rao V., Fujiwara N., Porcelli S. A., Glickman M. S. (2005) Mycobacterium tuberculosis controls host innate immune activation through cyclopropane modification of a glycolipid effector molecule. J. Exp. Med. 201, 535–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Vander Beken S., Al Dulayymi J. R., Naessens T., Koza G., Maza-Iglesias M., Rowles R., Theunissen C., De Medts J., Lanckacker E., Baird M. S., Grooten J. (2011) Molecular structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence factor, mycolic acid, determines the elicited inflammatory pattern. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 450–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Dao D. N, Sweeney K., Hsu T., Gurcha S. S, Nascimento I. P, Roshevsky D., Besra G. S., Chan J., Porcelli S. A., Jacobs W. R. (2008) Mycolic acid modification by the mmaA4 gene of M. tuberculosis modulates IL-12 production. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Matsunaga I., Naka T., Talekar R. S., McConnell M. J., Katoh K., Nakao H., Otsuka A., Behar S. M., Yano I., Moody D. B., Sugita M. (2008) Mycolyltransferase-mediated glycolipid exchange in mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 28835–28841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Komori T., Nakamura T., Matsunaga I., Morita D., Hattori Y., Kuwata H., Fujiwara N., Hiromatsu K., Harashima H., Sugita M. (2011) A microbial glycolipid functions as a new class of target antigen for delayed-type hypersensitivity. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 16800–16806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Roura-Mir C., Wang L., Cheng T. Y., Matsunaga I., Dascher C. C., Peng S. L., Fenton M. J., Kirschning C., Moody D. B. (2005) Mycobacterium tuberculosis regulates CD1 antigen presentation pathways through TLR-2. J. Immunol. 175, 1758–1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Alibaud L., Rombouts Y., Trivelli X., Burguière A., Cirillo S. L., Cirillo J. D., Dubremetz J. F., Guérardel Y., Lutfalla G., Kremer L. (2011) A Mycobacterium marinum TesA mutant defective for major cell wall-associated lipids is highly attenuated in Dictyostelium discoideum and zebrafish embryos. Mol. Microbiol. 80, 919–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]