Background: Notch-1 signaling is dysregulated in Alzheimer disease (AD).

Results: Anandamide (AEA) augments Notch-1 signaling in primary neurons and in the cortex of aged rats.

Conclusion: AEA can promote a shift in γ-secretase substrate processing to favor processing of Notch-1 over amyloid precursor protein.

Significance: Up-regulating Notch-1 signaling with a parallel reduction in amyloid precursor protein processing might restore neurogenesis and cognition in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer Disease, Amyloid Precursor Protein, Anandamide, Endocannabinoids, Notch, 2-Arachidonoylglycerol, Nicastrin, Numb

Abstract

Aberrant Notch signaling has recently emerged as a possible mechanism for the altered neurogenesis, cognitive impairment, and learning and memory deficits associated with Alzheimer disease (AD). Recently, targeting the endocannabinoid system in models of AD has emerged as a potential approach to slow the progression of the disease process. Although studies have identified neuroprotective roles for endocannabinoids, there is a paucity of information on modulation of the pro-survival Notch pathway by endocannabinoids. In this study the influence of the endocannabinoids, anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol, on the Notch-1 pathway and on its endogenous regulators were investigated in an in vitro model of AD. We report that AEA up-regulates Notch-1 signaling in cultured neurons. We also provide evidence that although Aβ1–42 increases expression of the endogenous inhibitor of Notch-1, numb (Nb), this can be prevented by AEA and 2-arachidonoylglycerol. Interestingly, AEA up-regulated Nct expression, a component of γ-secretase, and this was found to play a crucial role in the enhanced Notch-1 signaling mediated by AEA. The stimulatory effects of AEA on Notch-1 signaling persisted in the presence of Aβ1–42. AEA was found to induce a preferential processing of Notch-1 over amyloid precursor protein to generate Aβ1–40. Aging, a natural process of neurodegeneration, was associated with a reduction in Notch-1 signaling in rat cortex and hippocampus, and this was restored with chronic treatment with URB 597. In summary, AEA has the proclivity to enhance Notch-1 signaling in an in vitro model of AD, which may have relevance for restoring neurogenesis and cognition in AD.

Introduction

The Notch pathway is a highly conserved arbiter of cell fate decisions and is intimately involved in developmental processes (1, 2). Besides its pivotal role in neural development, it is also involved in the control of neurogenesis, neuritic growth (3), neural stem cell maintenance (4), synaptic plasticity (5), and long term memory (6) both in the developing and adult brain. There is a growing body of research demonstrating the lack of neurogenesis and memory impairment in AD2 (7–10). Possible roles of Notch signaling in the pathogenesis of AD have been investigated (7, 8, 11). There is evidence supporting a role for Notch in the pathogenesis of AD as presenilin-1/γ-secretase, which is responsible for cleaving amyloid precursor protein (APP) to generate amyloid β (Aβ), can also cleave Notch to generate the notch intracellular domain (NICD) (12). With the onset of neurodegeneration in the adult brain, the Notch signaling pathway becomes activated, possibly as a means to compensate for neuronal loss by promoting neuronal growth. However, in advanced stages of neurodegeneration, Notch signaling is reduced (13).

Notch signaling regulates stem cell number in vitro and in vivo and thus plays an important role in neurogenesis in the adult brain (4, 14). Neurogenesis has been reported to be drastically reduced in the aged brain compared with the brains of young adult rats (16), and a decline in neurogenesis in the hippocampus is proposed to underlie age-related memory impairments in rats and humans.

Upon ligand binding (e.g. delta, jagged), the membrane-tethered full-length Notch receptor becomes susceptible to proteolysis at site 2 (ADAM cleavage) that generates Notch extracellular truncation (NEXT) (17, 18). The membrane-associated remnant is then cleaved via γ-secretase (site 3), and NICD is subsequently released into the cytosol (19). NICD translocates to the nucleus to associate with the c-promoter binding factor 1 (CBF-1) family of transcription factors, resulting in transcriptional control of Hes genes (e.g. Hes1 and Hes5) (20). These genes interact in a complex way to regulate neural stem cell differentiation and brain morphogenesis (21–23).

Numb (Nb), the negative regulator of the Notch pathway, makes neurons more vulnerable to the deleterious effects of Aβ by altering calcium homeostasis (24) and up-regulating the p53 tumor suppressor protein (25, 26), signaling events that we have previously described to be pertinent in the neurodegeneration evoked by Aβ, the neuropathological peptide that accumulates in AD (27).

The γ-secretase is composed of four members; presenilins (PS1 and PS2), nicastrin (Nct), presenilin enhancer-2 (Pen-2), and anterior pharynx defective (Aph-1a and Aph-1b). Nct, a component of the γ-secretase, is a type 1 transmembrane protein that acts as a receptor site for substrate recognition, maturation, and stabilization of the γ-secretase (28–32). Loss of Nct has been shown to elicit an apoptotic phenotype in mouse embryos (33), and conditional forebrain inactivation of Nct results in a pattern of neurodegeneration consistent with that observed in AD, suggesting an essential role for Nct in the maintenance of neuronal survival (34).

The endocannabinoid system has emerged as a potential new target for neuroprotective therapy in AD (35). This system comprises the G protein-coupled cannabinoid (CB) receptors CB1 and CB2, their endogenous ligands, anandamide (AEA), 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), and the associated degradative enzymes fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and monoacyl glycerol lipase (36, 37). Recently, an opposing action of endocannabinoids on cholangiocarcinoma growth via the differential activation of Notch signaling has been reported (38). However, no study to date has investigated the effects of endocannabinoids on the pro-survival Notch pathway in an in vitro model of AD. This prompted us to investigate herein whether the endocannabinoid system impacts on Notch signaling and how cannabinoids may modulate aberrant Notch signaling in AD. We also investigated the effects of aging on the Notch-1 pathway and evaluated the effects of chronic pharmacological enhancement of AEA tone by preventing its degradation using the FAAH, URB 597.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Culture of Cortical Neurons

Primary cortical neurons were prepared as described previously (27). Briefly, 1-day-old male Wistar rats were decapitated in accordance with institutional and national ethical guidelines, and their cerebral cortices were removed. The dissected cortices were incubated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Sigma) containing trypsin (0.3%) for 25 min at 37 °C. The tissue was then triturated (X5) in PBS containing soybean trypsin inhibitor (0.1%(w/v)), DNase (0.2 mg/ml), and magnesium sulfate (0.1 m) and gently filtered through a sterile 40-μm mesh filter. After centrifugation at 2000 × g for 3 min at 20 °C, the pellet was resuspended in neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with heat-inactivated horse serum (10%), penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 units/ml), GlutaMAX (2 mm), and B27 (1%(v/v)). Suspended cells were plated out at a density of 0.25 × 106 cells on circular 13-mm diameter glass coverslips, coated with poly-l-lysine (60 μg/ml), and incubated in a humidified chamber containing 5% CO2, 95% air at 37 °C. After 48 h, 5 ng/ml cytosine-arabino-furanoside was included in the culture medium to prevent proliferation of non-neuronal cells. Culture medium was exchanged every 3 days, and cells were grown in culture for 5 days before treatment.

Drug Treatment

Aβ1–42 (EZBiolab) and Aβ42–1 (Invitrogen) was made up as a 200 μm stock solution in PBS and double-deionized water and allowed to aggregate for 48 h at 37 °C. For treatment of cortical neurons, Aβ1–42 was diluted to a final concentration of 2 μm in prewarmed neurobasal medium. Control cells were exposed to the reverse peptide, Aβ42–1 (2 μm), which we previously demonstrated to lack toxicity (39). Cells were exposed to Aβ1–42 in the presence or absence of the endocannabinoids, AEA (10 nm; Sigma) or 2-AG (10 nm; Sigma) to assess their ability to modulate Notch-1 signaling. The concentrations of AEA and 2-AG used in this study were chosen after a concentration response analysis on Notch cleavage (data not shown), and 10 nm was found to align Notch cleavage with the concentration of endocannabinoids that we previously established to confer neuroprotection (27). In some experiments, the hydrolysis of AEA and 2-AG was prevented by incubation with an inhibitor of fatty acid amide hydrolase, URB 597 (1 μm), and monoacyl glycerol inhibitor, URB 602 (100 μm), respectively (40, 41) (Cayman). The role of CB1 receptor on AEA-mediated regulation of the Notch-1 pathway was evaluated using the CB1 receptor antagonist AM 251 (5 μm) (42) (Tocris).

siRNA Transfection

ON-TARGETplus small interfering RNA (siRNA; 100 nm, Custom ON-TARGETplus Smart Pool siRNA containing a mixture of 4 SMART selection) targeting mouse Nct were purchased from Dharmacon. ON-TARGETplus non-targeting siRNA control (Dharmacon) was used as a negative control. siRNAs were transfected into primary neurons using DharmaFect 3 (Dharmacon). On day 4 in culture the primary neurons were transfected with Nct siRNA (100 nm) for 72 h. Knockdown efficiency was determined by immunocytochemistry.

Aging Study

Young (3 months; 250–350 g) and aged (26–30 months; 550–600 g) male Wistar rats (B&K Universal, Hull, UK) were housed in a controlled environment (temperature, 20–22 °C; 12:12 h light/dark cycle) in the BioResources Unit, Trinity College, Dublin. Water and food were provided at libitum and were maintained under veterinary supervision for the duration of the experiment. Young and aged rats were randomly divided into those that received subcutaneous injections of the FAAH inhibitor URB 597 (1 mg/kg; dissolved in 30% DMSO, saline) every second day and vehicle controls that received subcutaneous injections of 30% DMSO saline every second day for 28 days. All experiments were carried out under license from the Department of Health and Children (Ireland) and with ethical approval from the Trinity College Ethical Committee.

Immunocytochemistry

After treatment, cells were fixed with methanol for 10 min at −20°C, permeabilized with Triton X-100 (0.1%), and refixed with methanol for 5 min. The following antibodies were used overnight: NICD (1:100 dilution; ab8925; Abcam), Nct (1: 150 dilution; sc-25648; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Nb (1:400 dilution; 2756; Cell Signaling), Hes1 (1:100 dilution; ab71559; Abcam), and Hes5 (1:100 dilution; sc-25395; Santa Cruz). After primary incubation, immunoreactivity was detected using an appropriate biotinylated secondary antibody. Cells were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488TM avidin conjugate for a half-hour (1:1000 dilution; Invitrogen), and the nucleus was stained with Hoechst (1:1000 dilution; Invitrogen) for 15 min at room temperature. Immunofluorescence was visualized and captured using a Zeiss LSM 510 meta-confocal microscope (Zeiss). Images were processed using LSM 5 image examiner (Zeiss).

Luciferase Assays

Primary cortical neurons were seeded at a cell density of 2 × 105 cells/well in 24-well plates (1 ml/well). After incubation at 37 °C for 96 h, neurons were then transfected with 400 ng of a CBF-1 firefly luciferase reporter construct (4xwt-CBF-1-luc) using 2 μl of the GeneJuice transfection reagent (Merck). To control for transfection efficacy, 50 ng of a constitutively active pGL3- Renilla-luciferase construct were also included in each transfection. Empty vector DNA (pcDNA3.1) was included where needed to maintain constant DNA concentrations (575 ng per transfection). The medium was removed from the cells 48 h post transfection. Neurons were stimulated with a different treatment for 6 h, and subsequently luciferase activity was measured using the reporter microplate luminometer (Thermo Scientific). CBF-1 firefly luciferase activity was corrected for corresponding pGL3-Renilla luciferase activity to normalize for transfection efficiency. All transfections were carried out in triplicate, and data are expressed as -fold induction relative to control levels for a representative of a minimum of three separate experiments.

Western Blotting

Primary neuronal cultures were lysed using lysis buffer (30 μl/well; HEPES (25 mm), MgSO4 (5 mm), dithiothreitol (DTT; 5 mm), PMSF (2 mm), leupeptin (2 μg/ml), pepstatin (10 μg/ml), aprotinin (2 μg/ml), pH 7.4; Sigma) on ice. In the case of in vivo studies, brain samples were resuspended in lysis buffer (HEPES (25 mm), MgSO4 (5 mm), DTT (5 mm), PMSF (2 mm), leupeptin (2 μg/ml), pepstatin (10 μg/ml), aprotinin (2 μg/ml), pH 7.4; Sigma), and the supernatant collected was the whole cell protein. Normalized volumes of samples were resolved in 4–10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The following antibodies were used overnight: full-length Notch-1 (1:1000 dilution; 3268; Cell Signaling), cleaved Notch1/NEXT (m1711) (1:200 dilution; sc-23307; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), NICD (1:1000 dilution; ab8925; Abcam), Nb (1:1000 dilution; 2756; Cell Signaling), presenilin 1 (1:1000 dilution; ab76083; Abcam), presenilin 2 (1:5000 dilution; ab51249; Abcam), Nct (1: 1000 dilution; 3632; Cell Signaling), Aph-1a (1:1000 dilution; ab12104; Abcam), Aph-1b (1:1000 dilution, ab116657; Abcam). After incubation with primary antibodies, the membrane was incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (1:2,000 to 1:20,000, The Jackson Laboratory), exposed to chemiluminescent detection chemical (Supersignal, Pierce), and read under the luminescent image analyzer (LAS-4000, Fujifilm, Medical System Stamford, CT). Corresponding β-actin was measured, and the ratio of a protein band to corresponding total β-Actin was quoted using arbitrary units.

Quantification of Secreted Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, Aβ1–38

To determine whether AEA had any impact on APP processing and generation of different Aβ peptides, a sandwich immunoassay (that enables detection of Aβ 40/42/38) using the Meso Scale Discovery Sector Imager 6000 was used to quantify secreted Aβ peptides in the conditioned medium. All reagents were from Meso Scale Discovery if not stated otherwise. Briefly, on day 5 in culture, the medium was removed from the primary neuronal culture and washed with prewarmed medium. Cells were incubated with fresh medium or medium containing AEA (10 nm) for 24 h before analysis of the conditioned medium. The medium was removed and subjected to ruthenylated 4G8 (SULFO-TAGTM) at room temperature for 2 h before all plates were washed. All antibodies were diluted in 1% blocking buffer. For detection, Meso Scale Discovery Read buffer was added, and the light emission at 620 nm was measured after electrochemical stimulation. The corresponding concentrations of Aβ peptides in the samples were calculated using the Aβ peptide standard curves. Experiments were performed in duplicate and repeated five times.

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as the means ± S.E. of the number of experiments indicated in each case. Depending upon experimental design, statistical analysis was carried out by using either one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls or Bonferroni post-tests when significance was indicated. When comparison was made between two treatments, an unpaired Student's t test was performed to determine whether significant differences existed between the conditions. p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001 were considered significant. All statistical analysis was carried out using Graphpad Prism Software (Version 5.0).

RESULTS

Anandamide Up-regulates Notch-1 Signaling in Cultured Cortical Neurons

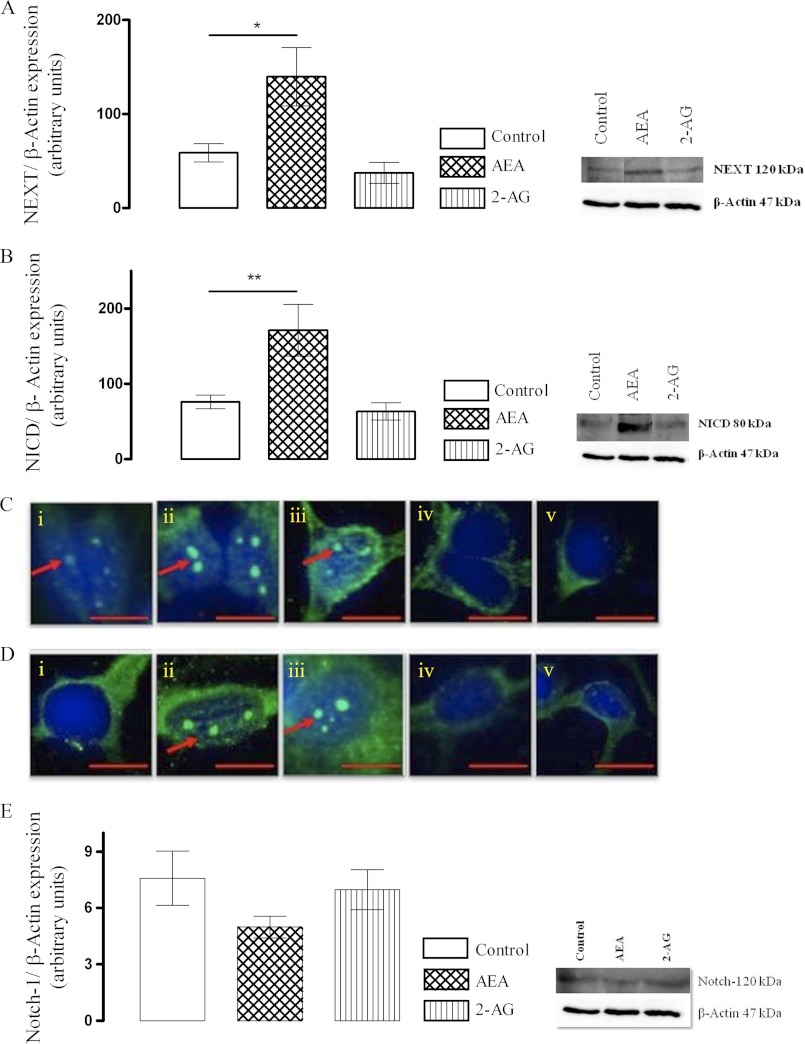

The effect of endocannabinoids on Notch-1 receptor processing and down-stream signaling in cortical neurons was evaluated. Primary cultured neurons were treated with AEA (10 nm) or 2-AG (10 nm) for 6 and 24 h. In other experiments neurons were exposed to the FAAH inhibitor, URB 597 (1 μm), or monoacyl glycerol lipase inhibitor, URB 602 (100 μm), for 6 and 24 h to up-regulate endocannabinoid tone. Exposure of neurons to AEA resulted in an increase in site 2 cleavage of the full-length Notch-1 receptor and enhanced cellular content of NEXT (Fig. 1A). Subsequently it was evident that AEA also up-regulated the γ-secretase-mediated generation of NICD in cortical neurons (Fig. 1B). To validate further, nuclear NICD immunoreactivity was used to access the effects of the endocannabinoids on Notch-1 receptor processing. Sample NICD immunofluorescence images are shown in Fig. 1C (6 h) and 1D (24 h). In control cells constitutive nuclear NICD was observed, and both AEA and URB 597 increased Notch-1 receptor cleavage and nuclear NICD as evident by enhanced nuclear NICD immunostaining at 6 h. This positive regulatory effect of AEA and URB 597 on the Notch-1 pathway persisted at the 24-h time point. A sample immunoblot of full-length Notch-1 receptor is shown in Fig. 1E, indicative of its reduction after exposure of neurons to AEA (although it failed to reach statistical significance). In contrast, treatment with 2-AG or URB 602 was not associated with any change in nuclear NICD at any of the time points examined.

FIGURE 1.

AEA up-regulates Notch-1 receptor cleavage to enhance cellular NEXT and NICD. A, cortical neurons were exposed to AEA (10 nm) or 2-AG (10 nm) for 24 h, and cellular NEXT was assessed by Western immunoblot. AEA enhanced site 2 cleavage of full-length Notch-1 receptor and enhanced generation of NEXT (*, p < 0.05 versus control, ANOVA, n = 6). B, AEA (10 nm) augmented subsequent site 3 cleavage by γ-secretase and generated NICD as measured by Western immunoblot (**, p < 0.01 versus control, ANOVA, n = 6). C, cortical neurons were exposed to AEA (10 nm), URB 597 (1 μm), 2-AG (10 nm), or URB 602 (100 μm) for 6 h. Nuclear translocation of NICD was assessed as a measure of Notch-1 receptor cleavage by immunocytochemistry. Exposure of neurons to AEA or URB 597 up-regulated NICD generation and its nuclear translocation. Sample confocal images of NICD immunostaining of cells treated with control medium (i), AEA (ii), URB 597 (iii), 2-AG (iv), and URB 602 (v) for 6 h are shown. In control cells constitutive nuclear NICD was observed. D, the positive regulatory effects of AEA and URB 597 on Notch-1 receptor cleavage and its nuclear translocation in cortical neurons persisted at 24 h. Sample confocal images of NICD immunostaining of cells treated with control medium (i), AEA (ii), URB 597 (iii), 2-AG (iv), and URB 602 (v) for 24 h are shown. Arrows indicate nuclear NICD expression. Scale bar, 10 μm, n = 6. E, exposure to AEA (10 nm) reduced (not statistically significant, p = 0.07, n = 6) full-length Notch-1 receptor in neurons possibly as a result of its enhanced processing.

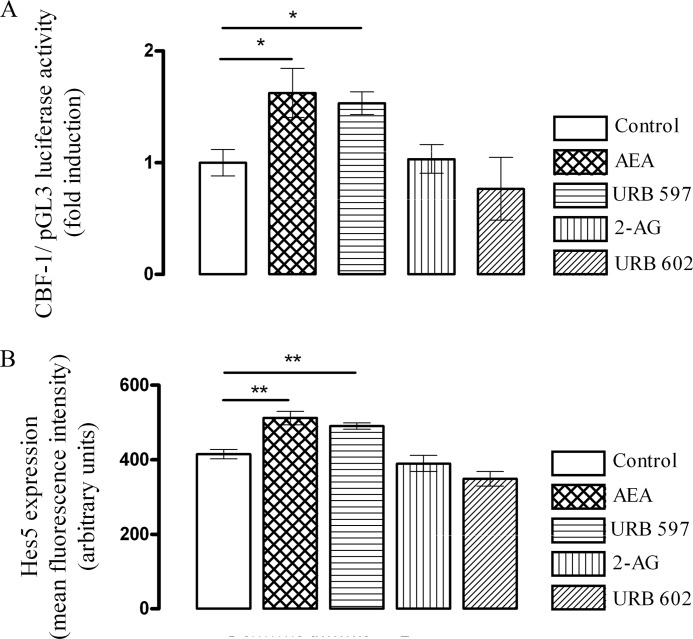

The increase in generation and nuclear NICD translocation triggered by AEA and URB 597 translated into a significant increase in CBF-1 reporter activation (p < 0.05, ANOVA, n = 5), as measured by CBF-1 dual luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 2A) that measures the luciferase activity under the control of CBF-1, thereby suggesting that AEA has the potential to induce the transcription of Notch-1 target genes. Thus, in control-treated cells CBF1 luciferase activity was 1 ± 0.1 (-fold induction ± S.E.), and this was significantly increased to 1.6 ± 0.2 by AEA and to 1.5 ± 0.1 by URB 597 (p < 0.05, ANOVA, n = 5). Downstream of CBF-1 reporter activation, Hes5 protein expression was increased in cells exposed to AEA and URB 597 (Fig. 2B). Thus, in control-treated cells, mean Hes5 fluorescence intensity was 414 ± 13 (mean arbitrary units ± S.E.), and this was significantly increased to 512 ± 18 (p < 0.01, ANOVA, n = 6) after treatment with AEA (10 nm, 6 h). Similarly, URB 597 (1 μm, 6 h) also significantly increased Hes5 expression to 490 ± 9 (p < 0.01, ANOVA, n = 6). However, neither 2-AG nor URB 602 had any effect on Hes5 expression.

FIGURE 2.

AEA augments Notch-1 downstream signaling. A, CBF-1 is a downstream signaling molecule in the NICD pathway that binds to the promoter of different Notch target genes. Cortical neurons were transfected with a CBF-1 luciferase reporter construct and then exposed to AEA (10 nm), URB 597 (1 μm), 2-AG (10 nm), or URB 602 (100 μm) for 6 h. CBF-1 activity was measured by dual luciferase reporter assay. CBF-1 reporter activity was significantly increased by AEA (10 nm; 6 h; *, p < 0.05 versus control, ANOVA, n = 5). Exposure of neurons to URB 597 (1 μm; 6 h) also enhanced CBF-1 reporter activity (*, p < 0.05 versus control, ANOVA, n = 5). In contrast, neither 2-AG nor URB 602 had any effect on CBF-1 reported activity. B, downstream to CBF-1, Hes5 expression was measured, and exposure of neurons to AEA increased Hes5 expression (**, p < 0.01 versus control, ANOVA, n = 6), and a similar increase was observed after exposure of neurons to URB 597 (**, p < 0.01 versus control, ANOVA, n = 6). Neither 2-AG nor URB 602 had any effect on Hes5 expression. Data expressed as mean ± S.E.

Nicastrin Is Involved in the AEA-induced Enhancement of Notch-1 Signaling

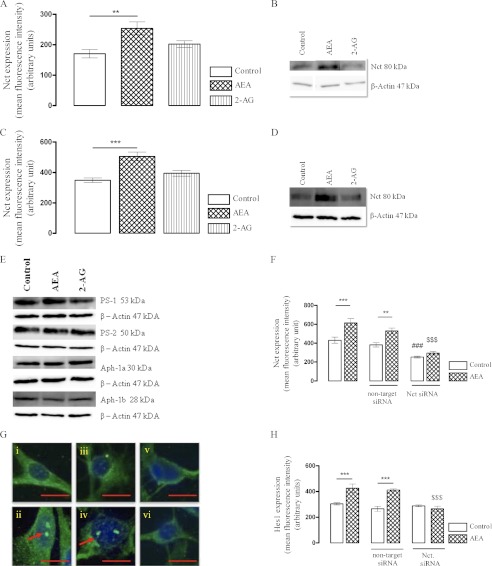

We examined whether the up-regulation in the γ-secretase-mediated NICD that was observed after treatment with AEA correlated with a change in the components of γ-secretase and investigated into the expression profile of PS-1, PS-2, Nct, Aph-1a, and Aph-1b. AEA significantly increased mean Nct fluorescence intensity from 160 ± 9 (mean arbitrary units ± S.E.) in control cells to 237 ± 16 (Fig. 3A, p < 0.01, ANOVA, n = 6). Next we determined Nct levels at a later time point of 24 h. Thus, in control-treated cells Nct expression was 348 ± 15 fluorescence units (mean arbitrary units ± S.E.), which increased to 505 ± 29 when cortical neurons were exposed with AEA (Fig. 3C, p < 0.001, ANOVA, n = 6). In contrast, 2-AG had no effect of Nct at 6 h or at 24 h. It is of note that basal Nct expression increased between the 6 and 24 h incubation time points. This may reflect a change in Nct expression over days in vitro, which may reflect a developmental influence of basal Nct expression (43). Western immunoblot confirms that AEA increased mature Nct in cultured cortical neurons (Fig. 3, B and D). The increase in Nct after treatment with AEA is a post-transcriptional process as we observed no change in Nct mRNA at any of the time points examined (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Nct is involved in the AEA-mediated enhancement of NICD generation. A, cortical neurons were exposed to AEA (10 nm) or 2-AG (10 nm) for 6 h, and Nct expression was assessed by immunocytochemistry. AEA (10 nm) significantly increased Nct expression (**, p < 0.01 versus control, ANOVA, n = 6). 2-AG had no effect on Nct expression at 6 h. B, shown is a sample Western immunoblot image of mature Nct of cells treated with control medium, AEA, and 2-AG for 6 h further validates immunocytochemistry results. C, after exposure of cortical neurons to AEA (10 nm) or 2-AG (10 nm) for 24 h, the stimulatory effect of AEA on Nct expression persisted (***, p < 0.001 versus control, ANOVA). 2-AG had no effect on Nct at 24 h. D, a sample Western immunoblot image of mature Nct of cells treated with control medium, AEA, and 2-AG for 24 h further validates immunocytochemistry results. E, cortical neurons were exposed to AEA (10 nm) or 2-AG (10 nm) for 24 h, and PS-1 expression was assessed by Western immunoblot. AEA (10 nm) had no impact on basal expression of PS-1. However, exposure of neurons to 2-AG (10 nm) reduced PS-1 expression (p < 0.05 versus control, ANOVA). AEA (10 nm) or 2-AG (10 nm) had no effect on basal expression of PS-2, Aph-1a, or Aph-1b at 24 h. F, cortical neurons were transfected with Nct siRNA (100 nm) for 72 h. This significantly reduced basal Nct expression (###, p < 0.001 versus control, ANOVA) by ∼60%. After down-regulation of Nct, AEA failed to induce Nct in Nct depleted neurons ($$$, p < 0.001 versus AEA). G, knockdown of Nct also prevented the ability of AEA to enhance NICD expression. Representative confocal images illustrate nuclear NICD in neurons exposed to control medium (i), AEA (ii), non-target siRNA (iii), non-target siRNA + AEA (iv), Nct siRNA (v), and Nct siRNA + AEA (vi). H, as a consequence of enhanced Notch-1 signaling, Hes1 immunoreactivity was increased after exposure of neurons with AEA (10 nm) (***, p < 0.001 versus control, ANOVA), and knockdown of Nct significantly prevented the AEA mediated up-regulation of Hes1 expression in primary neuronal cultures ($$$, p < 0.001 versus AEA). Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E. Scale bar, 10 μm, n = 6.

The changes in other components of γ-secretase were investigated. After treatment with 2-AG (Fig. 3E), a reduction in PS-1 was observed (p < 0.05, ANOVA, n = 6). However, no significant difference in the expression of PS-2, Aph-1a, and Aph-1b was observed when neurons were exposed to AEA or 2-AG as measured by Western immunoblot (Fig. 3E).

To determine whether Nct was required for the enhanced Notch-1 receptor cleavage by AEA, we used an RNA interference approach to down-regulate Nct expression by ∼60% (Fig. 3F). In cells exposed to Nct siRNA, the induction of NICD by AEA was prevented (Fig. 3G), signifying a central role of Nct in the AEA-mediated enhancement of Notch-1 receptor processing. Next we assessed the impact of Nct knock down on Hes1 immunoreactivity. In the non-target siRNA-treated cells, mean Hes1 fluorescence intensity was 265 ± 20, which significantly increased to 411 ± 8 after treatment with AEA (Fig. 3H; p < 0.001, ANOVA, n = 6). However, in cells transfected with Nct siRNA, Hes1 was unaffected by AEA (Fig. 3H), demonstrating a critical role for Nct in mediating the AEA-induced increase in Hes1 expression.

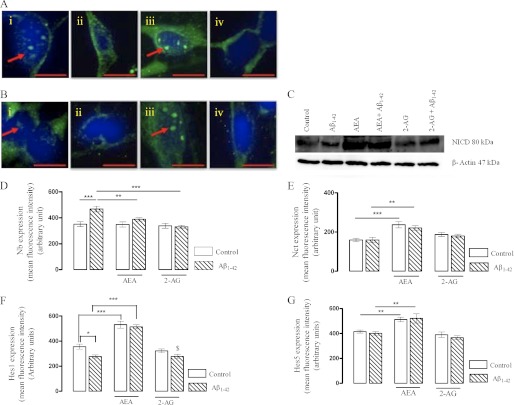

Aβ1–42 Negatively Regulates Notch-1 Signaling in Cultured Cortical Neurons, and This Is Reversed by AEA

Next, we investigated the effects of Aβ1–42 on Notch-1 signaling. Primary cultured neurons were exposed to Aβ1–42 (2 μm) in the presence or absence of AEA (10 nm) for 6 h (Fig. 4A) or 24 h (Fig. 4, B and C). Nuclear NICD (Fig. 4B) was used as an indication of Notch-1 receptor processing and was further validated by Western immunoblot (Fig. 4C). In cells treated with Aβ1–42 for 6 h, constitutive nuclear NICD immunoreactivity was reduced (Fig. 4Aii) compared with control neurons (Fig. 4Ai). However, in the presence of AEA, the Aβ1–42-mediated reduction in NICD was reversed, and enhanced Notch-1 receptor cleavage and nuclear NICD was evident (Fig. 4Aiii). This positive regulatory effect of AEA on the Notch-1 pathway persisted at the 24-h time point (Fig. 4, Biii and C).

FIGURE 4.

Aβ1–42 negatively regulates the Notch-1 signaling in cultured cortical neurons and this is reversed by AEA. A, cortical neurons were exposed to Aβ1–42 (2 μm) in the presence or absence of AEA (10 nm) or 2-AG (10 nm) for 6 h. Nuclear NICD was assessed as a measure of Notch-1 receptor processing. Aβ1–42 reduced constitutive nuclear NICD, and AEA reversed the Aβ1–42 mediated reduction in nuclear NICD. 2-AG had no effect on the constitutive NICD in presence of Aβ1–42. Sample confocal images of NICD immunostaining of cells treated with control medium (i), Aβ1–42 (ii), Aβ1–42 + AEA (iii), and Aβ1–42 + 2-AG (iv) for 6 h. B, the negative regulatory effect of Aβ1–42 on nuclear NICD persisted at 24 h, and this was reversed by AEA but not by 2-AG. Sample confocal images of NICD immunostaining of cells treated with control medium (i), Aβ1–42 (ii), Aβ1–42 + AEA (iii), and Aβ1–42 + 2-AG (iv) for 24 h. C, shown is a representative Western immunoblot of NICD expression after exposure of neurons to different treatments for 24 h. D, Nb expression was assessed by immunocytochemistry. Exposure of neurons with Aβ1–42 for 6 h increased Nb immunoreactivity (***, p < 0.001 versus control, ANOVA). Both AEA (10 nm) and 2-AG (10 nm) prevented the Aβ1–42 induced increase in Nb immunoreactivity (**, p < 0.01, AEA + Aβ1–42 versus Aβ1–42; ***, p < 0.001, 2-AG + Aβ1–42 versus Aβ1–42, ANOVA, n = 6). E, Aβ1–42 had no impact on neuronal Nct, and the AEA-induced increase in Nct (***, p < 0.001 versus control, ANOVA) persisted in the presence of Aβ1–42 (**, p < 0.01 versus Aβ1–42, ANOVA). 2-AG had no effect on the basal expression of Nct either in the presence or absence of Aβ1–42. F, exposure of neurons to Aβ1–42 reduced basal Hes1 immunoreactivity (*, p < 0.05 versus control, ANOVA), whereas AEA increased neuronal Hes1 at 6 h (***, p < 0.001 versus control), and this persisted in the presence of Aβ1–42 (***, p < 0.001 versus Aβ1–42). 2-AG failed to prevent the reduction in Hes1 mediated by Aβ1–42 ($, p < 0.05 versus control). G, neurons failed to increase Hes5 expression in presence of Aβ1–42 at 6 h. However, the AEA-mediated increase in Hes5 persisted in the presence of Aβ1–42 (**, p < 0.01 versus Aβ1–42). 2-AG had no impact on expression of Hes5. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E. Scale bar, 10 μm, n = 6.

To investigate the molecular mechanism underlying the reduced Notch-1 receptor cleavage after exposure of the neurons to Aβ1–42, we examined the expression profile of Nb, the endogenous negative regulator of the Notch pathway. Aβ1–42 (2 μm) significantly increased Nb expression in cultured cortical neurons, and this was prevented by both AEA and 2-AG. In control neurons, mean Nb fluorescence intensity was 350 ± 19 (mean arbitrary units ± S.E., Fig. 4D), which significantly increased to 467 ± 22 in cells treated with Aβ1–42 (Fig. 4D, p < 0.001, ANOVA, n = 6). Such an increase in Nb expression may account for the reduced Notch-1 receptor cleavage after exposure of neurons to Aβ1–42.

AEA prevented the Aβ1–42-mediated induction of Nb expression (Fig. 4D, 388 ± 14, p < 0.01, ANOVA, n = 6). 2-AG also prevented the Aβ1–42-mediated induction in Nb expression (Fig. 4D, 330 ± 12, p < 0.001, ANOVA, n = 6). We then investigated the expression profile of Nct in neurons exposed to Aβ1–42 in the presence of AEA and observed that Aβ1–42 on its own had no effect on basal expression level of Nct, and the AEA-mediated increase in Nct described in Fig. 3 persisted in Aβ1–42 (2 μm)-co-treated neurons (Fig. 4E). After exposure to Aβ1–42, mean Nct fluorescence intensity was 159 ± 14, exposure of cortical neurons to AEA significantly increased Nct expression to 237 ± 16 (p < 0.001 versus control, ANOVA, n = 6), and this up-regulation of Nct persisted in the presence of Aβ1–42 (221 ± 11, p < 0.01, ANOVA, n = 6). Although 2-AG prevented the Aβ1–42 induced increase in Nb, it had no effect on Nct (Fig. 4E). Fig. 3 demonstrates that the siRNA-mediated down-regulation of Nct prevents AEA from enhancing Notch-1 processing. The fact that exposure of neurons to both AEA and 2-AG prevents the Aβ1–42-induced increase in Nb but that neither cannabinoid alone reduces Nb basal expression may reflect that Nb has a role to play in the Aβ1–42 mediated reduction in Notch-1 signaling, whereas in Aβ1–42- and AEA co-treated neurons Nct plays a central role in enhanced Notch-1 signaling as discussed in Fig. 3.

Having observed that Aβ1–42 could reduce the generation of NICD in parallel to an induction of Nb expression, we examined the consequence on downstream signaling such as Hes1 and Hes5 expression. Exposure of neurons to Aβ1–42 significantly reduced Hes1 immunoreactivity (Fig. 4F, p < 0.05 versus control, ANOVA, n = 6), and AEA reversed this effect of Aβ1–42 to restore Hes1 expression (Fig. 4F, p < 0.001 versus Aβ1–42, ANOVA, n = 6). 2-AG failed to prevent the negative regulatory effect of Aβ1–42 on Hes1.

With regard to Hes5, it has been reported that any reduction in Hes1 may be compensated by an associated increase in Hes5 (44) and vice versa. Exposure of neurons to Aβ1–42 had no effect on Hes5, although in the presence of AEA, Hes5 expression was significantly elevated (Fig. 4G, p < 0.01 versus control, ANOVA, n = 6), and this elevation persisted in the presence of Aβ1–42 (Fig. 4G, p < 0.01, ANOVA, n = 6). Because exposure to Aβ1–42 resulted in a reduction of Hes1 (Fig. 4F), a parallel increase in Hes5 was anticipated. However, Hes5 expression failed to increase above its basal expression in neurons exposed to Aβ1–42, suggesting that neurons had possibly lost their ability to achieve an optimum up-regulation of Hes5. All of the negative regulatory effects of Aβ1–42 on Notch-1 signaling were reversed by AEA, signifying that the stimulatory effect of AEA on the Notch-1 pathway persists even in the presence of the Aβ.

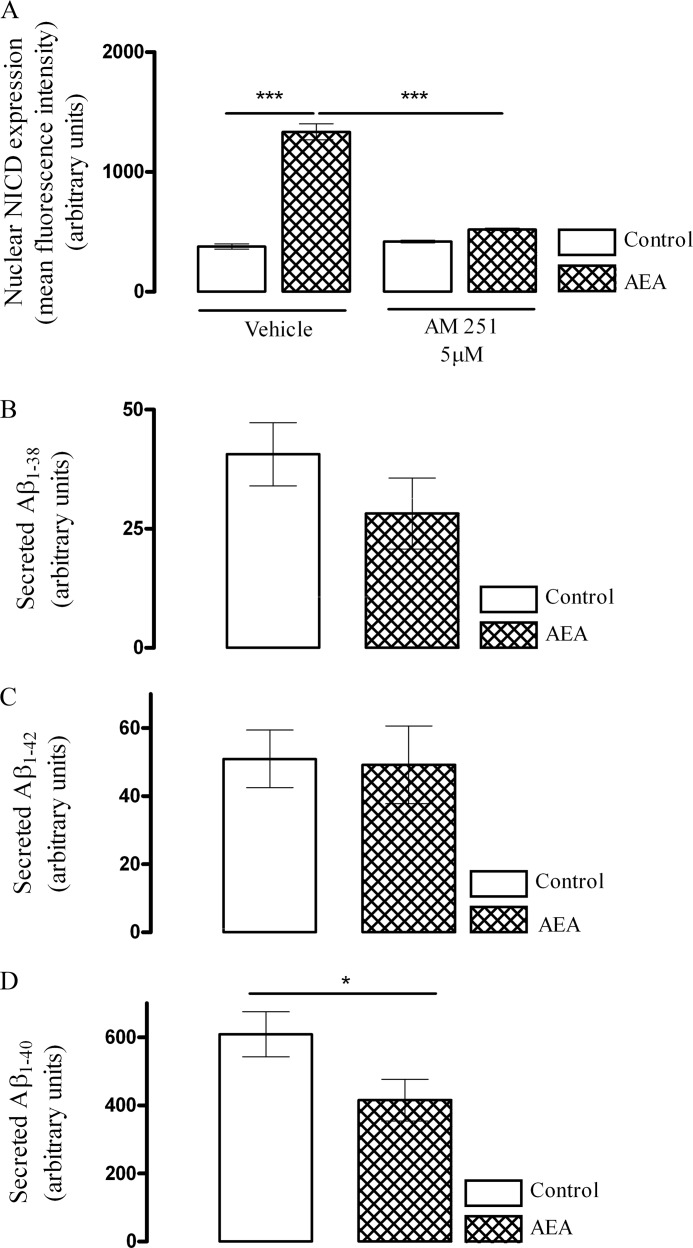

Up-regulation of Notch-1 Signaling by AEA Is Dependent on the CB1 Receptor

CB1 and CB2 are the two main receptors types through which endocannabinoids mediate their actions. Cortical neurons were incubated with AM 251 (5 μm) for 30 min after which they were exposed to either vehicle control or AEA (10 nm) for 6 h. AM 251 (5 μm) prevented the AEA-mediated up-regulation in nuclear NICD (Fig. 5A). Thus, in control cells, mean nuclear NICD was 377 ± 22 (mean arbitrary units ± S.E.), and this was significantly increased to 1335 ± 67 (p < 0.001, ANOVA, n = 6) by AEA. This induction in nuclear NICD was reduced to 520 ± 11 (p < 0.001, ANOVA, n = 6) after pretreatment of neurons with AM 251 (5 μm), signifying that AEA-mediated up-regulation of Notch-1 signaling is mediated in part through the CB1 receptor.

FIGURE 5.

AEA acting via the CB1 receptor induces an isoform shift in γ-secretase that preferentially cleaves Notch-1 over APP. A, the role of the CB1 receptor in AEA-mediated enhancement of site 3 cleavage of Notch-1 receptor was evaluated by measuring nuclear NICD immunoreactivity. Cortical neurons were pretreated with either vehicle or CB1 receptor antagonist AM 251 (5 μm) for 30 min after which cells were exposed to control medium or AEA (10 nm) for 6 h. In AM 251 pretreated cells, basal nuclear NICD immunoreactivity was similar to control cells. However, pretreatment with AM 251 abolished the AEA-induced nuclear NICD immunoreactivity (***, p < 0.001 versus vehicle + AEA, ANOVA, n = 6), suggesting a CB1 receptor-dependent mechanism. B and C, APP processing after exposure of neurons to AEA was assessed by sandwich immunoassay. Exposure of neurons to AEA for 24 h had no effect on the amount of secreted Aβ1–38 and Aβ1–42. D, however, there was a reduction in secreted Aβ1–40 in cells exposed to AEA for 24 h (*, p < 0.05 versus control at 24 h; Student's t test, n = 5). Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.

AEA Promotes a Shift in γ-Secretase Substrate Processing That Preferentially Cleaves Notch-1 over APP

Finally, we investigated whether enhancement of Notch-1 receptor cleavage by γ-secretase is associated with any concomitant increase in APP processing, which would be expected to lead to a generation of secreted Aβ. There was no significant difference in the amount of Aβ1–38 (Fig. 5B) or Aβ1–42 (Fig. 5C) generated after exposure of neurons to AEA for 24 h. However, after a 24-h treatment with AEA, the amount of secreted Aβ1–40 was significantly reduced (p < 0.05, Student's t test, n = 5). These results suggest that after exposure of cultured cortical neurons to AEA, there is an isoform shift in the γ-secretase that preferentially cleaves Notch-1 over APP, resulting in an enhanced generation of NICD and reduced production of APP-derived Aβ1–40 species.

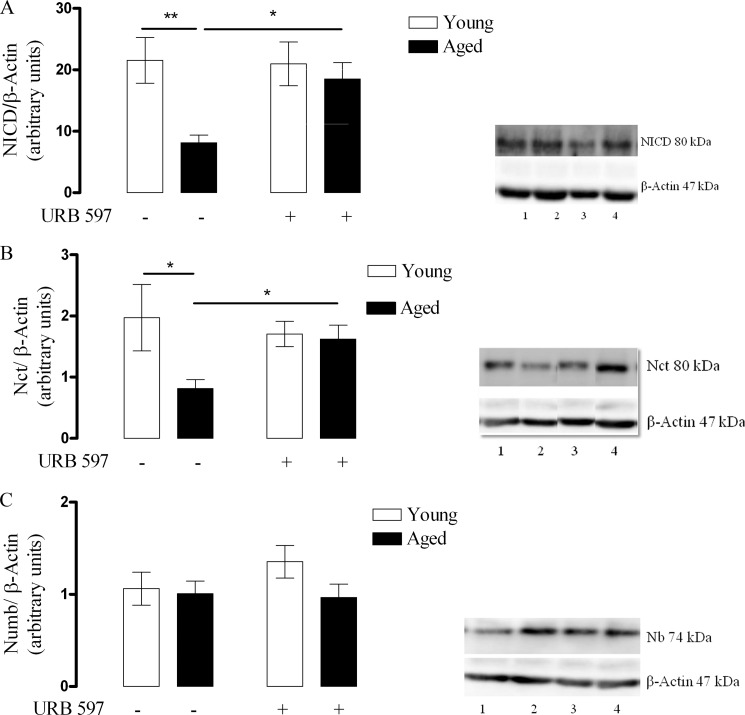

Chronic Treatment with URB 597 Prevents the Age-related Reduction in Notch-1 Signaling and Nct Expression

Our in vitro results suggest that AEA positively regulates the Notch-1 pathway and that an up-regulation of Nct plays a central role in the AEA-mediated enhancement of Notch-1 signaling. We attempted to investigate the effects of aging on Notch-1 signaling and also to evaluate the effects of chronic pharmacological enhancement of AEA tone by administration URB 597 on the Notch-1 pathway in vivo.

NICD was significantly reduced in the cortex (Fig. 6A) of the aged vehicle control group compared with the young vehicle control group (p < 0.01, Student's t test, n = 6), and this was prevented in the aged rats treated with URB 597 (p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-tests, n = 6). Thus, data from densitometry analysis revealed that in the young vehicle control group, NICD was 21 ± 4 (mean arbitrary units ± S.E.), which reduced significantly to 8 ± 1 in the aged vehicle control group. Chronic treatment with URB 597 prevented this reduction in NICD (18 ± 3). This signifies that aging reduces Notch-1 receptor cleavage, which can be reversed by chronic treatment with URB 597.

FIGURE 6.

Aging reduces NICD and Nct expression in the rat cortex, and this is prevented by chronic treatment with URB 597. A, young and aged rats were treated with either DMSO (vehicle) or URB 597 (1 mg/kg), and NICD was assessed in cortex by Western immunoblot. Aging significantly reduced NICD (**, p < 0.01 versus young vehicle control, Student's t test, n = 6), and this was prevented when aged rats were chronically treated with URB 597 (1 mg/kg) (*, p < 0.05 versus young URB 597 treated, Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-tests, n = 6). Representative Western immunoblot shows that NICD was reduced in cortex of aged vehicle control rats (lane 3) when compared with young vehicle control rats (lane 1). Although chronic URB 597 treatment had no significant effect on young rats (lane 2), it prevented age-related reduction of NICD in aged rats (lane 4). B, aging significantly reduced Nct expression (*, p < 0.05 versus young vehicle control, Student's t test, n = 6), and this was prevented when aged rats were chronically injected with URB 597 (1 mg/kg) (*, p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-tests, n = 6). A representative Western immunoblot shows that Nct expression was reduced in the cortex of aged vehicle control rats (lane 3) when compared with young vehicle control rats (lane 1). Although chronic URB 597 treatment had no significant effect on young rats (lane 2) it prevented the age-related decline of Nct expression (lane 4). C, neither aging nor chronic treatment with URB 597 (1 mg/kg) had any effect on Nb expression (p > 0.05, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-tests, n = 6). A representative Western immunoblot of Nb expression suggesting no difference in its expression between young vehicle control (lane 1) and aged vehicle control (lane 2) is shown. Chronic URB 597 treatment had no significant effect on young rats (lane 3) or on aged rats (lane 4). Results are displayed as mean arbitrary units ± S.E.

Nct expression was also significantly reduced in the cortex of the aged vehicle control group compared with the young vehicle control group (Fig. 6B; p < 0.05, Student's t test, n = 6), and this was prevented in the aged rats treated with URB 597 (p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-tests, n = 6). Data from densitometry analysis revealed that in the young vehicle control group Nct expression was 2 ± 0.5 (mean arbitrary units ± S.E.) which reduced significantly to 0.8 ± 0.2 in the aged vehicle control group. Chronic treatment with URB 597 reversed the reduction in Nct expression signifying that aging is associated with reduced Nct expression that can be prevented by chronic treatment with URB 597. No change was observed in the expression of Nb in any of experimental groups (Fig. 6C).

DISCUSSION

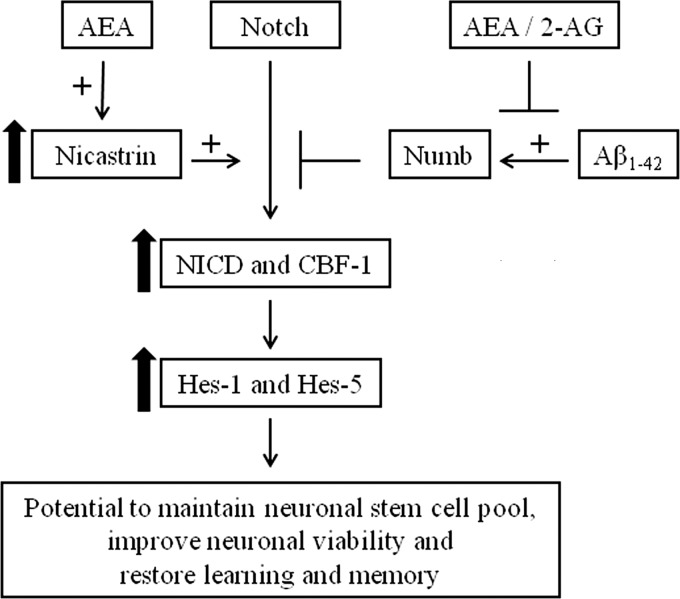

Our results demonstrate that AEA, acting via the CB1 receptor, can positively regulate the Notch-1 pathway via engagement of Nct (Fig. 7). Similar changes were observed when AEA was pharmacologically up-regulated by the FAAH inhibitor, URB 597. Furthermore, Aβ1–42 reduces Notch-1 signaling, and this was reversed by AEA. However, the 2-AG branch of the endocannabinoid system failed to influence Notch-1 signaling. The data also suggest that AEA can promote a shift in γ-secretase substrate processing to favor processing of Notch-1 over APP. When we investigated the effects of aging, a natural process of neurodegeneration, on this pathway we observed that Notch-1 signaling is reduced in the aged brain and that chronic treatment with URB 597 restores the pathway to that observed in the brain of young rats.

FIGURE 7.

The endocannabinoid AEA positively regulates the Notch pathway. Up-regulation of Nct by AEA plays a central role in AEA-mediated regulation of the Notch pathway in cultured cortical neurons.

Aβ1–42 reduced Notch-1 signaling. An investigation into the possible mechanisms for this reduction in Notch-1 cleavage revealed a concomitant increase in the expression of cellular Nb, the endogenous negative regulator of the Notch-1 cleavage. Previously, Chan et al. (24) reported that when cultured rat hippocampal cells were exposed to Aβ1–42 for 12- 24 h, there was a marked increase in cellular Nb that remained elevated throughout a 24-h treatment period. Cell death increases 2-fold under these conditions, and an up-regulation of Nb, therefore, precedes the majority of cell death in the hippocampal cultures (24). In this study, we observed an increase in cellular Nb occurring at an earlier time point of 6 h, and this correlates with the reduction in constitutive NICD during that time. These observations occur at a time point upstream of the Aβ-mediated neurodegeneration that we previously reported (24). The negative regulatory effect of Aβ1–42 on downstream Notch-1 signaling was also evident by the reduction in Hes1 expression.

When primary cortical neurons were exposed to AEA for 6 h, Notch-1 receptor cleavage together with downstream Hes1 and Hes5 expression was significantly increased. At 24 h, when neurons were exposed to AEA, the increase in uncleaved Notch-1 product, NEXT, and cleaved Notch-1 product, NICD, was associated with a reduction in full-length Notch-1 receptor. The enhanced generation of NICD persisted in the presence of Aβ1–42. However, in cells treated with 2-AG, there was no observable change in constitutive NICD. In contrast, both AEA and 2-AG prevented the Aβ1–42-mediated increase in Nb. Nb expression has been reported to be modulated by various ligands that act through G-protein-coupled receptors (45). Therefore, it is possible that AEA and 2-AG regulate Nb via engagement with the CB receptors. AEA and 2-AG also have the potential to modulate Nb expression at the transcription level as they prevented the Aβ-mediated increase in Nb mRNA expression (data not shown). However, further studies are required to confirm whether cannabinoids also cause a switch in different Nb isoforms, some of which can be more neurotoxic (24, 46). Most of cellular amyloid intracellular domain is generated through the amyloidogenic pathway (47). When Notch-1 competes with APP for γ-secretase, APP processing and hence the generation of Aβ and amyloid intracellular domain, are reduced. Because NICD has been shown to suppress amyloid intracellular domain-mediated reactive oxygen species generation and cell death (9), it is also a possibility that the NICD that is generated after exposure of neurons to AEA can be vital in neuronal survival (4). Recently, Soltys et al. (48) reported that AEA can regulate post-natal neural progenitor cell fate. AEA prevented the premature differentiation of post-natal neural progenitor cells, which later differentiated into glial cells followed by differentiation of the remaining of the post-natal neural progenitor cells into neurons. The enhanced Notch-1 signaling that promotes the expression of Hes genes may represent a mechanism for the maintenance and regulation of the neural progenitor cell pool by cannabinoids (21–23).

Exposure of cells to AEA alone had no effect on Nb, indicating that up-regulation of NICD was not due to an alternation in this negative regulator of Notch-1. This result prompted us to investigate an alternative mechanism for NICD up-regulation. Nct overexpression has been reported to confer resistance to cytotoxic chemotherapy so that anti-nicastrin antibodies are able to decrease Notch-1 signaling in tumor cells (49–51). We observed that exposure of neurons to AEA significantly enhances neuronal Nct expression. Furthermore, when cellular Nct was depleted using a RNA interference approach, AEA failed to increase Notch-1 cleavage, and this highlights a role for Nct in the AEA-mediated induction of Notch-1 cleavage. Nct knockdown also resulted in a reduction in neuronal Hes1 expression. Recently work by Frampton et al. (38) suggested that AEA can induce Notch-1 signaling by recruiting a γ-secretase that is rich in presenilin-1. However, we did not observe any significant change in presenilin-1 expression mediated by AEA. The difference in experimental conditions and dose of AEA used (10 μm compared with 10 nm used in the current study) could account for the difference in the findings. The positive regulatory effect of AEA on Notch-1 signaling appears to be mediated through its action on the CB1 receptor, as the CB1 antagonist AM 251 abolished the enhanced generation and nuclear NICD.

We sought to investigate if AEA could impact on γ-secretase to affect APP processing in parallel with Notch-1 cleavage as this would have implications for the generation of Aβ species. Aβ1–40 is the major secreted form of Aβ. We observed no effect of AEA on secreted Aβ1–38 or Aβ1–42 at 24 h, but the amount of secreted Aβ1–40 in the medium was reduced by AEA. This suggests that AEA differentially affects γ-secretase processing of APP and Notch-1 and preferentially cleaves Notch-1 as evident by a reduction in secreted Aβ1–40 that accumulates in the medium over 24 h. The cysteine residues at position 195, 213, 230, and 248 in the ectodomain of Nct are relatively preserved over different species (29). Recently Pamrén et al. (52) reported that mutations in cysteine residues at 213 and 230 resulted in the formation of functionally active γ-secretases that are capable of processing APP and Notch. However, the mutants showed significantly reduced APP processing compared with wild type variants. The Notch processing was relatively preserved in both cell lines. Mutations in the conserved 312–369 domain of Nct can strongly modulate γ-secretase cleavage of APP while only weakly affecting Notch cleavage (53). Thus, depending on the type of Nct that associates with the γ-secretase, the processing of APP and Notch can be differentially regulated. We have observed an up-regulation in Notch-1 signaling and a parallel reduction in secreted Aβ1–40 over 24 h by AEA, suggesting a preferential processing of Notch over APP. It would be interesting to investigate what other mechanisms driving the process, as we did not observe any change in Nct mRNA, suggesting a post-translational modification of Nct. Because modifications in Nct can cause differences in APP and Notch processing (52), it is also possible that post-translational modification of mature Nct by AEA plays a role in substrate recognition by γ-secretase.

Age-related neurodegeneration is a multi-factorial complex process. Cognitive decline and reduced neurogenesis precede age-related neurodegeneration. In the embryonic rat brain all components of γ-secretase are expressed in abundance, and in the young adult rat brain these reduce significantly. This parallels with a reduction of the γ-secretase-generated intracellular domains, including NICD (54). In line with their findings, our results suggest that NICD generation is suppressed further in the aged rats. Kodam et al. (43) reported that in the adult cerebral cortex, Nct expression remains relatively high. Thus, our finding of a higher level of Nct in the cortex of young rats is consistent with the finding of Kodam et al. (43). However, we also report that this expression reduces further in aged cortex compared with young adult cortex. This reduction of Nct in the aged brain could be a possible explanation for the reduced Notch-1 signaling that we observed in our in vivo studies. The age-related decline in Nct and NICD was reversed when rats were chronically treated with URB 597.

What could be the consequence of enhanced Notch-1 cleavage in the aged rat brain? Notch antisense mice overexpressing Notch-1 antisense mRNA have ∼50% that of the normal level of Notch mRNA and protein in the hippocampus (55). They fail to display long term potentiation and have enhanced long term depression at the synapses indicating that the reduction of Notch levels leads to an alteration of long-lasting plasticity. Importantly the long term potentiation deficits seem to result specifically from deficits in Notch signaling, and this can be rescued by application of Notch ligand like Jagged 1, which increases Notch signal. In a parallel study to ours, it was observed that the aged rat used in this study had deficits in long term potentiation, and this was restored when aged rats were chronically treated with URB 597 (56). Apart from the anti-inflammatory properties exerted by AEA, augmentation of Notch-1 signaling may represent a possible explanation for the improvement in long term potentiation observed in aged rats treated with URB 597.

Both in vertebrates and invertebrates, Notch signaling is crucial for long term memory formation. Interestingly, it appears that Notch signaling can function as a bidirectional modulator of long term memory formation, as the overexpression of wild type Notch can facilitate formation of long term memory (57). Because in the moderate stages of AD long term memory becomes impaired (58), these results raise the possibility that enhancement of endogenous Notch signaling by manipulating the cannabinoid system could be used as therapeutic aids for cognitive disorders such as AD.

Neurogenesis in the adult brain is thought to contribute to the plasticity of the hippocampus and olfactory system. Impaired neurogenesis, on the other hand, may compromise plasticity and neuronal function in these areas and exacerbate neuronal vulnerability (59). Regulated Notch signaling is essential for neural progenitor cells maintenance in the adult brain and for prolonged neurogenesis throughout life. Recent observations raise the possibility that dysregulation of Notch signaling might contribute to attenuated neurogenesis and impaired hippocampal function during aging (60). Compromised neurogenesis is another arm in the pathogenesis of AD that presumably takes place earlier than onset of hallmark lesions or neuronal loss. It is proposed to play a role in the initiation and progression of the neuropathology in AD. Enhanced Notch signaling in the early stage of AD is suggested to compensate for this neuronal loss, which ultimately abolishes as the disease progresses with widespread neuronal apoptosis that is far beyond repairable (61).

Given that endocannabinoids can confer neuroprotection in models of neurodegeneration (62, 63) and considering our findings that AEA and its pharmacological enhancement have the proclivity to enhance Notch-1 signaling in an in vitro model of AD and in the aged brain, the possibility of an endocannabinoid-based therapy to alleviate symptoms and delay progression of neurodegeneration via the Notch pathway warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Richard Killick (Kings College London) for kindly providing the 4xwt-CBF-1-luc reporter. We sincerely thank to Prof. Marina A. Lynch for providing access to aged rats for the in vivo study.

This work is supported by Health Research Board Ireland.

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- APP

- amyloid precursor protein

- Aβ

- amyloid β

- NEXT

- notch extracellular truncation

- NICD

- notch intracellular domain

- CBF-1

- c-promoter binding factor

- Hes1

- Hairy and enhancer of split-1

- Hes5

- Hairy and enhancer of split-5

- Nb

- numb

- PS-1

- presenilin-1

- PS-2

- presenilin-2

- Nct

- nicastrin

- Aph-1a

- anterior pharynx defective 1a

- Aph-1b

- anterior pharynx defective-1b

- CB

- cannabinoid

- AEA

- anandamide

- 2-AG

- 2-arachidonoylglycerol

- FAAH

- fatty acid amide hydrolase

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schweisguth F. (2004) Regulation of notch signaling activity. Curr. Biol. 14, R129–R138 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ehebauer M., Hayward P., Arias A. M. (2006) Notch, a universal arbiter of cell fate decisions. Science 314, 1414–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sestan N., Artavanis-Tsakonas S., Rakic P. (1999) Contact-dependent inhibition of cortical neurite growth mediated by notch signaling. Science 286, 741–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hitoshi S., Alexson T., Tropepe V., Donoviel D., Elia A. J., Nye J. S., Conlon R. A., Mak T. W., Bernstein A., van der Kooy D. (2002) Notch pathway molecules are essential for the maintenance, but not the generation, of mammalian neural stem cells. Genes Dev. 16, 846–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poirazi P., Mel B. W. (2001) Impact of active dendrites and structural plasticity on the memory capacity of neural tissue. Neuron 29, 779–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shors T. J., Miesegaes G., Beylin A., Zhao M., Rydel T., Gould E. (2001) Neurogenesis in the adult is involved in the formation of trace memories. Nature 410, 372–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anderton B. H., Dayanandan R., Killick R., Lovestone S. (2000) Does dysregulation of the Notch and wingless/Wnt pathways underlie the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease? Mol. Med. Today 6, 54–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lathia J. D., Mattson M. P., Cheng A. (2008) Notch. From neural development to neurological disorders. J. Neurochem. 107, 1471–1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim S. Y., Kim M. Y., Mo J. S., Park H. S. (2007) Notch1 intracellular domain suppresses APP intracellular domain-Tip60-Fe65 complex mediated signaling through physical interaction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1773, 736–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dale T. C. (1998) Signal transduction by the Wnt family of ligands. Biochem. J. 329, 209–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Woo H. N., Park J. S., Gwon A. R., Arumugam T. V., Jo D. G. (2009) Alzheimer disease and Notch signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 390, 1093–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nagarsheth M. H., Viehman A., Lippa S. M., Lippa C. F. (2006) Notch-1 immunoexpression is increased in Alzheimer and Pick's disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 244, 111–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Costa R. M., Honjo T., Silva A. J. (2003) Learning and memory deficits in Notch mutant mice. Curr. Biol. 13, 1348–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Androutsellis-Theotokis A., Leker R. R., Soldner F., Hoeppner D. J., Ravin R., Poser S. W., Rueger M. A., Bae S. K., Kittappa R., McKay R. D. (2006) Notch signaling regulates stem cell numbers in vitro and in vivo. Nature 442, 823–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deleted in proof

- 16. Verret L., Trouche S., Zerwas M., Rampon C. (2007) Hippocampal neurogenesis during normal and pathological aging. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32, S26–S30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brou C., Logeat F., Gupta N., Bessia C., LeBail O., Doedens J. R., Cumano A., Roux P., Black R. A., Israël A. (2000) A novel proteolytic cleavage involved in Notch signaling. The role of the disintegrin-metalloprotease TACE. Mol. Cell 5, 207–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mumm J. S., Schroeter E. H., Saxena M. T., Griesemer A., Tian X., Pan D. J., Ray W. J., Kopan R. (2000) A ligand-induced extracellular cleavage regulates γ-secretase-like proteolytic activation of Notch1. Mol. Cell 5, 197–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kopan R., Schroeter E. H., Weintraub H., Nye J. S. (1996) Signal transduction by activated mNotch. Importance of proteolytic processing and its regulation by the extracellular domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 1683–1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iso T., Kedes L., Hamamori Y. (2003) HES and HERP families. Multiple effectors of the Notch signaling pathway. J. Cell Physiol. 194, 237–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bertrand N., Castro D. S., Guillemot F. (2002) Proneural genes and the specification of neural cell types. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 517–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ross S. E., Greenberg M. E., Stiles C. D. (2003) Basic helix-loop-helix factors in cortical development. Neuron 39, 13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kageyama R., Ohtsuka T., Hatakeyama J., Ohsawa R. (2005) Roles of bHLH genes in neural stem cell differentiation. Exp. Cell Res. 306, 343–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chan S. L., Pedersen W. A., Zhu H., Mattson M. P. (2002) Numb modifies neuronal vulnerability to amyloid β-peptide in an isoform-specific manner by a mechanism involving altered calcium homeostasis. Implications for neuronal death in Alzheimer disease. Neuromolecular Med. 1, 55–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Checler F., Dunys J., Pardossi-Piquard R., Alves da Costa C. (2010) p53 is regulated by and regulates members of the γ-secretase complex. Neurodegener. Dis. 7, 50–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Colaluca I. N., Tosoni D., Nuciforo P., Senic-Matuglia F., Galimberti V., Viale G., Pece S., Di Fiore P. P. (2008) NUMB controls p53 tumor suppressor activity. Nature 451, 76–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Noonan J., Tanveer R., Klompas A., Gowran A., McKiernan J., Campbell V. A. (2010) Endocannabinoids prevent β-amyloid-mediated lysosomal destabilization in cultured neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 38543–38554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wolfe M. S., Xia W., Ostaszewski B. L., Diehl T. S., Kimberly W. T., Selkoe D. J. (1999) Two transmembrane aspartates in presenilin-1 required for presenilin endoproteolysis and γ-secretase activity. Nature 398, 513–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yu G., Nishimura M., Arawaka S., Levitan D., Zhang L., Tandon A., Song Y. Q., Rogaeva E., Chen F., Kawarai T., Supala A., Levesque L., Yu H., Yang D. S., Holmes E., Milman P., Liang Y., Zhang D. M., Xu D. H., Sato C., Rogaev E., Smith M., Janus C., Zhang Y., Aebersold R., Farrer L. S., Sorbi S., Bruni A., Fraser P., St George-Hyslop P. (2000) Nicastrin modulates presenilin-mediated notch/glp-1 signal transduction and βAPP processing. Nature 407, 48–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee S. F., Shah S., Li H., Yu C., Han W., Yu G. (2002) Mammalian APH-1 interacts with presenilin and nicastrin and is required for intramembrane proteolysis of amyloid-β precursor protein and Notch. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45013–45019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Steiner H., Winkler E., Edbauer D., Prokop S., Basset G., Yamasaki A., Kostka M., Haass C. (2002) PEN-2 is an integral component of the γ-secretase complex required for coordinated expression of presenilin and nicastrin. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 39062–39065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brijbassi S., Amtul Z., Newbigging S., Westaway D., St George-Hyslop P., Rozmahel R. F. (2007) Excess of nicastrin in brain results in heterozygosity having no effect on endogenous APP processing and amyloid peptide levels in vivo. Neurobiol. Dis. 25, 291–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nguyen V., Hawkins C., Bergeron C., Supala A., Huang J., Westaway D., St George-Hyslop P., Rozmahel R. (2006) Loss of nicastrin elicits an apoptotic phenotype in mouse embryos. Brain Res. 1086, 76–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tabuchi K., Chen G., Südhof T. C., Shen J. (2009) Conditional forebrain inactivation of nicastrin causes progressive memory impairment and age-related neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 29, 7290–7301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Campbell V. A., Gowran A. (2007) Alzheimer disease. taking the edge off with cannabinoids? Br. J. Pharmacol. 152, 655–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mackie K. (2006) Mechanisms of CB1 receptor signaling: endocannabinoid modulation of synaptic strength. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 30, 19–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mackie K. (2006) Cannabinoid receptors as therapeutic targets. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 46, 101–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Frampton G., Coufal M., Li H., Ramirez J., DeMorrow S. (2010) Opposing actions of endocannabinoids on cholangiocarcinoma growth is via the differential activation of Notch signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 316, 1465–1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Boland B., Campbell V. (2004) Aβ-mediated activation of the apoptotic cascade in cultured cortical neurones. A role for cathepsin L. Neurobiol. Aging 25, 83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lever I. J., Robinson M., Cibelli M., Paule C., Santha P., Yee L., Hunt S. P., Cravatt B. F., Elphick M. R., Nagy I., Rice A. S. (2009) Localization of the endocannabinoid-degrading enzyme fatty acid amide hydrolase in rat dorsal root ganglion cells and its regulation after peripheral nerve injury. J. Neurosci. 29, 3766–3780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Boland B., Campbell V. (2003) β-Amyloid (1–40)-induced apoptosis of cultured cortical neurones involves calpain-mediated cleavage of poly-ADP-ribose polymerase. Neurobiol. Aging 24, 179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Downer E., Boland B., Fogarty M., Campbell V. (2001) δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol induces the apoptotic pathway in cultured cortical neurones via activation of the CB1 receptor. Neuroreport 12, 3973–3978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kodam A., Vetrivel K. S., Thinakaran G., Kar S. (2008) Cellular distribution of γ-secretase subunit nicastrin in the developing and adult rat brains. Neurobiol. Aging 29, 724–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ishibashi M., Ang S. L., Shiota K., Nakanishi S., Kageyama R., Guillemot F. (1995) Targeted disruption of mammalian hairy and Enhancer of split homolog-1 (HES-1) leads to up-regulation of neural helix-loop-helix factors, premature neurogenesis, and severe neural tube defects. Genes Dev. 9, 3136–3148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dho S. E., Trejo J., Siderovski D. P., McGlade C. J. (2006) Dynamic regulation of mammalian numb by G protein-coupled receptors and protein kinase C activation. Structural determinants of numb association with the cortical membrane. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 4142–4155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roncarati R., Sestan N., Scheinfeld M. H., Berechid B. E., Lopez P. A., Meucci O., McGlade J. C., Rakic P., D'Adamio L. (2002) The γ-secretase-generated intracellular domain of β-amyloid precursor protein binds Numb and inhibits Notch signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 7102–7107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pardossi-Piquard R., Checler F. (2012) The physiology of the β-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain AICD. J. Neurochem. 120, 109–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Soltys J., Yushak M., Mao-Draayer Y. (2010) Regulation of neural progenitor cell fate by anandamide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 400, 21–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Filipovic A., Gronau J. H., Green A. R., Wang J., Vallath S., Shao D., Rasul S., Ellis I. O., Yagüe E., Sturge J., Coombes R. C. (2011) Biological and clinical implications of nicastrin expression in invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat 125, 43–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Harrison H., Farnie G., Brennan K. R., Clarke R. B. (2010) Breast cancer stem cells. Something out of notching? Cancer Res. 70, 8973–8976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pannuti A., Foreman K., Rizzo P., Osipo C., Golde T., Osborne B., Miele L. (2010) Targeting Notch to target cancer stem cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 3141–3152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pamrén A., Wanngren J., Tjernberg L. O., Winblad B., Bhat R., Näslund J., Karlström H. (2011) Mutations in nicastrin protein differentially affect amyloid β-peptide production and Notch protein processing. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 31153–31158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen F., Yu G., Arawaka S., Nishimura M., Kawarai T., Yu H., Tandon A., Supala A., Song Y. Q., Rogaeva E., Milman P., Sato C., Yu C., Janus C., Lee J., Song L., Zhang L., Fraser P. E., St George-Hyslop P. H. (2001) Nicastrin binds to membrane-tethered Notch. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 751–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Frånberg J., Karlström H., Winblad B., Tjernberg L. O., Frykman S. (2010) Gamma-secretase dependent production of intracellular domains is reduced in adult compared to embryonic rat. PLoS One 5, 9772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang Y., Chan S. L., Miele L., Yao P. J., Mackes J., Ingram D. K., Mattson M. P., Furukawa K. (2004) Involvement of Notch signaling in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9458–9462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Murphy N., Cowley T. R., Blau C. W., Dempsey C. N., Noonan J., Gowran A., Tanveer R., Olango W. M., Finn D. P., Campbell V. A., Lynch M. A. (2012) The fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor URB 597 exerts anti-inflammatory effects in hippocampus of aged rats and restores an age-related deficit in long term potentiation. J. Neuroinflammation 9, 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ge X., Hannan F., Xie Z., Feng C., Tully T., Zhou H., Xie Z., Zhong Y. (2004) Notch signaling in Drosophila long term memory formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 10172–10176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Förstl H., Kurz A. (1999) Clinical features of Alzheimer disease. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 249, 288–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lazarov O., Marr R. A. (2010) Neurogenesis and Alzheimer disease. At the crossroads. Exp. Neurol. 223, 267–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Imayoshi I., Kageyama R. (2011) The role of Notch signaling in adult neurogenesis. Mol. Neurobiol. 44, 7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Costa R. M., Drew C., Silva A. J. (2005) Notch to remember. Trends Neurosci. 28, 429–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Khaspekov L. G., Brenz Verca M. S., Frumkina L. E., Hermann H., Marsicano G., Lutz B. (2004) Involvement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in cannabinoid receptor-dependent protection against excitotoxicity. Eur. J. Neurosci. 19, 1691–1698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ramírez B. G., Blázquez C., Gómez del Pulgar T., Guzmán M., de Ceballos M. L. (2005) Prevention of Alzheimer disease pathology by cannabinoids. Neuroprotection mediated by blockade of microglial activation. J. Neurosci. 25, 1904–1913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]