Background: Heparanase is involved in the pathology of many diseases.

Results: Heparanase cleaves heparan sulfate (HS) oligosaccharides in either consecutive or gapped cleavage mode.

Conclusion: The susceptibility of glycosidic linkage bonds to heparanase degradation is sensitive to the nonreducing end saccharide structure of the cleavage site.

Significance: The results will help us to understand the pathophysiological effects of HS that arise from heparanase activity.

Keywords: Carbohydrate Biosynthesis, Carbohydrate Chemistry, Glycobiology, Glycosaminoglycan, Heparan Sulfate

Abstract

Heparan sulfate (HS) is a highly sulfated polysaccharide that serves many biological functions, including regulating cell growth and inflammatory responses as well as the blood coagulation process. Heparanase is an enzyme that cleaves HS and is known to display a variety of pathophysiological effects in cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer disease. The link between heparanase and diseases is a result of its selective cleavage of HS, which releases smaller HS fragments to enhance cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. Despite its importance in pathological diseases, the structural cues in HS that direct heparanase cleavage and the steps of HS depolymerization remain unknown. Here, we sought to probe the substrate specificity of heparanase using a series of structurally defined oligosaccharide substrates. The sites of heparanase cleavage on the oligosaccharide substrates were determined by mass spectrometry and gel permeation chromatography. We discovered that heparanase cleaves the linkage of glucuronic acid linked to glucosamine carrying 6-O-sulfo groups. Furthermore, our findings suggest that heparanase displays different cleavage modes by recognizing the structures of the nonreducing ends of the substrates. Our results deepen the understanding of the action mode of heparanase.

Introduction

Heparan sulfate (HS)3 is a structurally complex polysaccharide that is expressed ubiquitously on the cell surface and in the extracellular matrix. HS is composed of repeating disaccharide units of glucuronic acid (GlcUA) and glucosamine. The glucosamine residues can be modified by N-deacetylation and N- and O-sulfations, and the GlcUA residues can undergo isomerization to form iduronic acid (IdoUA) residues. Furthermore, the 2-OH position of GlcUA and IdoUA can be sulfated. The unique sulfation patterns of HS and the presence of IdoUA residues are believed to give rise to the selectivity that allows HS to exhibit different functions (1). The HS isolated from natural tissues and cells consists of domains with different levels of sulfations and epimerization (2). This domain-like structural feature gives rise to segments that are highly sulfated, low sulfated, and unsulfated, respectively. Among these domains, the highly sulfated domain interacts with various proteins contributing to their biological activity. In some cases, the protein ligand binds to a specific arrangement of sulfated residues, and in others, the interaction is primarily electrostatic. In either case, the formation of these highly sulfated domains will determine whether a protein ligand binds to HS (3). Therefore, the biosynthesis and the degradation process to release highly sulfated domains are likely to be tightly regulated to maintain the physiological functions of HS. The current experimental evidence suggests that the domain structures of HS are controlled by HS biosynthetic enzymes, i.e. HS sulfotransferases (4), as well as heparanase, which is a HS-degrading enzyme (5).

Heparanase is a glucuronidase that cleaves HS in a variety of mammalian cells and tissues. It hydrolyzes the glycosidic bonds between GlcUA and glucosamine residues that are located in the low sulfated domain of HS (6). The action of heparanase modulates the functions of HS to bind to a multitude of proteins, including growth factors and their receptors, chemokines, enzymes, and extracellular matrix proteins. In fact, uncleaved HS lacks the ability to form a complex with protein effector that is needed to induce signaling activity (7). For example, basic fibroblast growth factor has been shown to be sequestered by HS on the cell surface (8). However, heparanase expressed by metastatic tumor cells and activated cells of the immune system may release fibroblast growth factor, eliciting an indirect neovascular response (9). Thus, heparanase acts as a regulatory switch mediating the release of specifically tailored saccharide structures within HS with restricted binding specificities. However, the substrate specificity and the mode of action of heparanase remain unknown.

The actions of heparanase have been linked to numerous human diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer disease (10). Despite the biological significance of heparanase, less effort has been made to understand how structural cues within HS structure may direct cleavage or the sequence of events during HS depolymerization by heparanase. This is largely because structurally heterogeneous polysaccharides were used in the previous investigations (6). Only limited studies have been carried out using structurally defined oligosaccharide substrates or polysaccharides with simplified sulfation patterns (11, 12). To date, it has been difficult to unambiguously assign the mode of action of heparanase. Recently, we reported an advanced chemoenzymatic method to synthesize HS oligosaccharides with high efficiency and purity (13, 14). This method allowed us to prepare structurally defined oligosaccharide substrates to probe heparanase. Coupling the structurally defined substrates with mass spectrometry analysis should improve the accuracy of the substrate specificity of heparanase studies.

In this work, we probed the substrate specificity of heparanase using a library of structurally defined oligosaccharides ranging from penta- to nonasaccharides. The products of heparanase cleavage were identified by electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS to determine heparanase preference for endolytic or exolytic cleavage at the reducing or nonreducing ends of substrates. Furthermore, time course studies were utilized to investigate whether heparanase cleaves distributively or processively and the enzyme's preference for certain substrates. Our data suggest that heparanase utilizes key structural features within HS to cleave endolytically toward the nonreducing end first. Thus, the residue at the nonreducing end directs heparanase to preserve or degrade the structure. Moreover, heparanase depolymerizes HS utilizing a nonprocessive method but degrades substrates at variable rates based on their structure. Our data reveal for the first time that heparanase is an editing enzyme that may regulate the release/preservation of specific saccharide structures. This study advances our understanding of heparanase recognition of HS and reveals an additional level of HS regulation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression of Heparanase Construct in Sf9 Cells

The human single-chain GS3 construct for constitutively active heparanase was constructed by removing the linker region between Glu109 and Lys158 based on the report by Nardella et al. (15). In this construct, the 8- and 50-kDa subunits were linked via three glycine-serine repeats with the nucleotide sequence GGCTCGGGATCGGGTTCT to replace amino acid residues from Glu109 to Lys158. The cDNA covering the GS3 construct was synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). The GS3 construct was cloned into a pFastBac-Mel-HT vector using EcoRI and NotI sites with primers 5′-ATATTAGCGAATTCACAAGACGTGGTCGACCTCGAT-3′ and 5′-ATAAATGCGGCCGCATTAGATACAAGCGGCGACCTTAGCGTTACGGAT-3′, where the restriction sites of EcoRI and NotI are underlined (16). Recombinant baculoviruses expressing heparanase GS3 (15) were generated using the Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression system (Invitrogen). Recombinant baculoviruses were used to infect Sf9 insect cells in shake cultures (2.0 × 106 cells/ml) grown in Sf-900 III SFM (Invitrogen) at 27.5 °C and 135 rpm. After 72 h of infection, the medium was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min to pellet the cells, and the supernatant was collected. The supernatants were diluted 1:1 with buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl and 150 mm NaCl (pH 7.5) and purified as outlined below.

Purification of Recombinant Heparanase

The recombinant heparanase was purified using a similar method previously described in U.S. Patent 2007/0009989 (17). Briefly, the diluted supernatant was applied to a heparin HyperD column (Pall Life Sciences) and washed with 50 mm Tris-HCl and 150 mm NaCl (pH 7.5) at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. The protein was eluted with 50 mm Tris-HCl and 1.5 m NaCl (pH 7.5). Fractions containing heparanase activity were pooled, mixed with glycerol at a final concentration of 15%, and stored at −80 °C until used.

Preparation of Oligosaccharide Substrates

All oligosaccharides were elongated from p-nitrophenyl (pNP) β-glucuronide (GlcUA-pNP), which was purchased from Sigma. The Penta-1 backbone with the structure GlcUA-N-trifluoroacetylglucosamine (GlcNTFA)-GlcUA-GlcNTFA-GlcUA-pNP was prepared using a previously described method (13). Briefly, GlcUA-pNP was incubated with a UDP-monosaccharide donor (UDP-GlcNAc, UDP-GlcNTFA, or UDP-GlcUA) and bacterial glycosyltransferase (KfiA or Pasteurella multocida heparosan synthase 2) in buffer containing 25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.2) and 10 mm MnCl2. To ensure that >95% of the UDP-monosaccharide donor was converted to UDP, the reaction was incubated for 16 h at room temperature and analyzed using a polyamine-based HPLC column. After the addition of two monosaccharides, the reaction was purified using a C18 column (0.75 × 20 cm; Biotage), which was eluted with a linear gradient of 0–100% acetonitrile in H2O and 0.1% TFA over 60 min at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. The product was determined by exploiting the UV absorbance of the pNP tag at 310 nm, and the identity of the product was confirmed by ESI-MS. The reaction cycle was repeated two times to prepare the Penta-1 backbone. Further elongation of Penta-1 to Hepta-2 and Nona-3 was achieved by additional cycles with the incubation of UDP donors, KfiA, and P. multocida heparosan synthase 2 following the same procedure as described above. Alternatively, by alternating the addition of GlcNAc-GlcUA or GlcNTFA-GlcUA, we were able to synthesize five additional nonasaccharides (Nona-4 to Nona-8) by essentially the same protocol used above.

The N-sulfation of the oligosaccharide backbones was completed by detrifluoroacetylation, followed by N-sulfation with N-sulfotransferase. The oligosaccharide backbones were dried and resuspended (10 ml) in a solution containing CH3OH, H2O, and (C2H5)3N (2:2:1, v/v/v). The reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 16 h until detrifluoroacetylation reached completion. The detrifluoroacetylated substrates were dried, resuspended in H2O, and N-sulfated. In brief, N-sulfation was carried out with N-sulfotransferase (67 μg/ml) and 0.45 mm 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate in a total volume of 20 ml to yield N-sulfated oligosaccharide substrates. 6-O-Sulfation was carried out using 20 μg/ml 6-O-sulfotransferase 1, 60 μg/ml 6-O-sulfotransferase 3, and 0.45 mm 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate in buffer containing 50 mm MES. The 35S-labeled 6-O-sulfated products were synthesized utilizing 0.1 mg/ml 6-O-sulfotransferase 1, 0.3 mg/ml 6-O-sulfotransferase 3, and 50 μm 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-[35S]phosphosulfate in a 100-μl reaction. The product purity and identity of the synthesized oligosaccharides (Penta-1, Hepta-2, and Nona-3 to Nona-8) were confirmed by high resolution DEAE-HPLC and ESI-MS, respectively.

Heparanase Enzymatic Reactions

Enzymatic reactions with 35S-labeled material were carried out as described previously (12). Enzymatic reactions with unlabeled material were carried out under similar conditions with the following exceptions: 100 μg/ml each substrate (Nona-3 and Nona-7) and 3.75 μg/ml heparanase. The reaction was incubated for 0, 5, 15, 25, 60, 120, 240, and 480 min or 16 h at 37 °C, followed by subsequent heating (100 °C for 5 min) and centrifugation (13,200 rpm for 5 min) to precipitate the insoluble material. The reaction was ready for subsequent analysis.

High Resolution DEAE-HPLC Analysis

To elucidate the cleavage dynamics of heparanase, recombinant heparanase was incubated with 35S-labeled Nona-3 and Nona-7 at 0, 5, 15, 25, 60, 120, 240, and 480 min. The reaction was stopped by subsequent heating (100 °C for 5 min) and centrifugation (13,200 rpm for 5 min) to precipitate the insoluble material. The cleavage products were analyzed and separated on a DEAE-NPR column (4.6 mm (inner diameter) × 7.5 cm; Tosoh Biosciences), which was eluted with a linear gradient 0–1 m NaCl in 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) over 60 min at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

MS analysis was performed on a Thermo LCQ Deca mass spectrometer. The oligosaccharides were dissolved in H2O and injected via direct infusion (30 μl/min) into the instrument. The experiments were performed utilizing a negative ionization mode with a spray voltage of 3 kV and a capillary temperature of 160 °C. The MS data were acquired and processed using Xcalibur 1.3 software.

Separation of Oligosaccharide by Gel Permeation Chromatography

The heparanase-digested products were separated and purified by fractionation on a Bio-Gel P-2 column (0.75 × 200 cm; Bio-Rad), which was equilibrated with a solution containing 0.1 mm ammonium bicarbonate at a flow rate of 4 ml/h. The identities of the cleavage products were confirmed as described under “Mass Spectrometry Analysis.”

RESULTS

Preparation of Structurally Defined Oligosaccharide Substrates

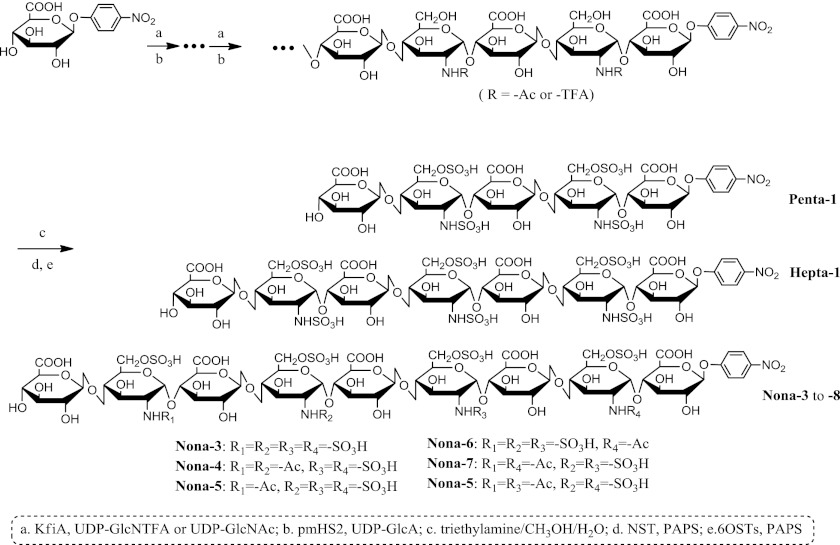

A library of oligosaccharides was synthesized to determine the specificity of heparanase. The library consisted of eight oligosaccharides carrying 6-O-sulfo groups (Fig. 1). The synthesis was completed using a chemoenzymatic approach involving backbone elongation and sulfation steps. Elongation was completed using two bacterial glycosyltransferases, N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase from Escherichia coli strain K5 (KfiA) (Fig. 1, Step a) and P. multocida heparosan synthase 2 (Fig. 1, Step b). In this synthesis, a GlcUA derivative (GlcUA-pNP) was used as the starting material. The pNP group of the starting material has absorbance at 310 nm, which facilitated detection during analysis. The backbone oligosaccharides contained strategically placed GlcNTFA residues, which were converted to N-sulfoglucosamine (GlcNS) residues readily in a later step (Fig. 1, Steps c and d) (13). This design allowed us to control the positions of GlcNS residues in the oligosaccharides (Fig. 1, Steps c and d). At the 6-O-sulfation step (Fig. 1, Step e), 6-O-sulfotransferases 1 and 3 were employed to fully 6-O-sulfate the oligosaccharides. The structures of the substrates were confirmed by ESI-MS (Table 1 and supplemental Fig. S1). The 6-O-[35S]sulfo-labeled substrates were also prepared and showed a single symmetric peak in a high resolution DEAE-HPLC trace (Table 1 and supplemental Fig. S2), suggesting that the purity of the substrates was high. It is important to note that such structurally diversified 6-O-sulfated nonasaccharide library had not been synthesized previously.

FIGURE 1.

Scheme for synthesis of oligosaccharide substrates. Synthesis was initiated from GlcUA-pNP. The starting monosaccharide was elongated by glycosyltransferases to the desired size. The resultant oligosaccharides were then N-sulfated and 6-O-sulfated by N-sulfotransferase (NST) and 6-O-sulfotransferases 1 and 3 (6OSTs), respectively. A total of eight oligosaccharides were synthesized, and structural analysis of each oligosaccharide was conducted by ESI-MS (supplemental Fig. S1). The purity was assessed by DEAE-HPLC (supplemental Fig. S2). KfiA is the N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase from E. coli strain K5. pmHS2, P. multocida heparosan synthase 2; GlcA, GlcUA; PAPS, 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate.

TABLE 1.

Summary of heparanase cleavages of oligosaccharide substrates

1 The oligosaccharides were prepared by chemoenzymatic synthesis.

2 The arrows indicate the sites of heparanase cleavage.

3 The molecular masses were determined by ESI-MS.

4 Percent purity was calculated using high resolution DEAE-HPLC.

Minimum Size for a Heparanase Substrate

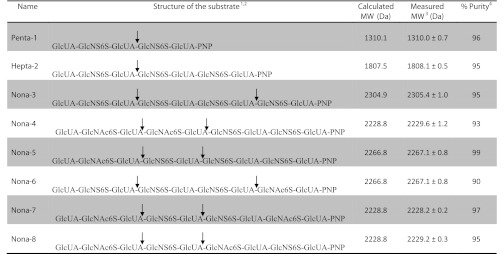

We sought to determine whether heparanase cleavage is dependent on the size of the substrate. To this end, we employed three oligosaccharides (Penta-1, Hepta-2, and Nona-3) that contained different numbers of GlcUA-GlcNS6S repeating units: Penta-1, Hepta-2, and Nona-3 have two, three, and four repeats of the unit, respectively. Subjecting 35S-labeled Nona-3 to heparanase digestion yielded three products as measured by gel permeation chromatography (Bio-Gel P-2), suggesting that two glycosidic bonds were susceptible to the digestion (Fig. 2A). Structural analysis of heparanase-digested Nona-3 was carried out by ESI-MS. In this experiment, unlabeled Nona-3 was first digested with heparanase, and the products were resolved using a Bio-Gel P-2 column. The fractions from the Bio-Gel P-2 column were subjected to ESI-MS analysis. An oligosaccharide with a molecular mass of 1013.0 ± 0.4 Da was identified in fraction 42, which is very close to the calculated molecular mass of 1012.8 Da for a tetrasaccharide with the structure GlcNS6S-GlcUA-GlcNS6S-GlcUA (Tetra-17) (Fig. 2B and supplemental Table 1). The data suggest that this tetrasaccharide was from the middle segment (residues 4–7) of Nona-3 (Fig. 2). Using a similar method, a trisaccharide with the structure GlcUA-GlcNS6S-GlcUA (Tri-12) and a pNP-tagged disaccharide with the structure GlcNS6S-GlcUA-pNP (Di(pNP)-9) were identified (Fig. 2B and supplemental Table 1). These data allowed us to determine the sites of heparanase cleavage of Nona-3 as depicted in Fig. 2C.

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of heparanase-digested Nona-3. A, Bio-Gel P-2 elution profiles of 35S-labeled Nona-3 without (upper panel) and with (lower panel) heparanase digestion. B, ESI-MS spectra of heparanase-digested Nona-3 from fractions eluted from the P-2 column. Left panel, spectrum of Tri-12 from fractions 51–57. Middle panel, spectrum of Tetra-17 from fractions 43–49. Right panel, spectrum of Di(pNP)-9 from fractions 71–75. C, chemical reaction involved in the digestion of Nona-3 with heparanase.

Digestion of 35S-labeled Hepta-2 with heparanase yielded two 35S-labeled products, suggesting that the substrate contained a single cleavage site (Table 1 and supplemental Fig. 3A). Unlike Nona-3, ∼15% of Hepta-2 remained undigested, suggesting that the susceptibility of the substrate to the digestion of heparanase was size-dependent. The structures of those two products were identified to be a trisaccharide (Tri-12) with a molecular mass of 691.6 ± 0.5 Da, which is close to the calculated molecular mass of GlcUA-GlcNS6S-GlcUA (691.6 Da), and a tetrasaccharide (Tetra(pNP)-14) with a molecular mass of 1134.0 ± 0.4 Da, which is close to the calculated molecular mass of GlcNS6S-GlcUA-GlcNS6S-GlcUA-pNP (1133.9 Da) (Table 1 and supplemental Fig. 3B). Interestingly, subjecting Penta-1 to heparanase digestion resulted in partial digestion, as 71% of the starting material remained (supplemental Fig. S4), further strengthening the conclusion that the susceptibility to heparanase cleavage is dependent on the size of the substrate.

The results from the structural analysis of the cleavage products suggest that heparanase cleaves only the internal glycosidic linkages. For example, when Nona-3 was used as a substrate, heparanase did not cleave the bond between residues 1 and 2, representing an exoglycosidic bond. A similar phenomenon was observed for shorter substrates: Hepta-2 and Penta-1. Our result is consistent with the conclusion that heparanase is an endolytic hydrolase (11, 18). The substrates employed here have the linkage GlcUA-GlcNS6S, which could have been susceptible to heparanase digestion if it contains exolytic activity. Heparanase showed a preference for cleavage of the endoglycosidic bonds. Thus, our results provide direct evidence that heparanase exclusively displays endolytic glucuronidase activity.

Role of GlcNS6S/GlcNAc6S in Directing Heparanase Cleavages

The disaccharide repeating units GlcUA-GlcNS6S and GlcUA-GlcNAc6S co-exist throughout HS in low sulfated domains. Although heparanase is known to cleave the -GlcUA-GlcNS6S- linkage, the effect of a nearby disaccharide unit of -GlcUA-GlcNAc6S- on the action of heparanase has not been investigated. Here, we prepared a series of nonasaccharide substrates that contained the mixing disaccharide units GlcUA-GlcNAc6S and GlcUA-GlcNS6S. GlcUA-GlcNAc6S can be located at the nonreducing end (Nona-4 and Nona-5), the reducing end (Nona-6), and both ends (Nona-7) and alternated with GlcUA-GlcNS6S units (Nona-8). These substrates provided us the opportunity to systematically examine the contribution of the GlcNAc6S motif to the selection of cleavage sites by heparanase. The 35S-labeled and unlabeled substrates were treated with heparanase and analyzed using a Bio-Gel P-2 column and by ESI-MS (Table 1 and supplemental Figs. S5–S9). All of these substrates, with the exception of Nona-8, were completely digested by heparanase.

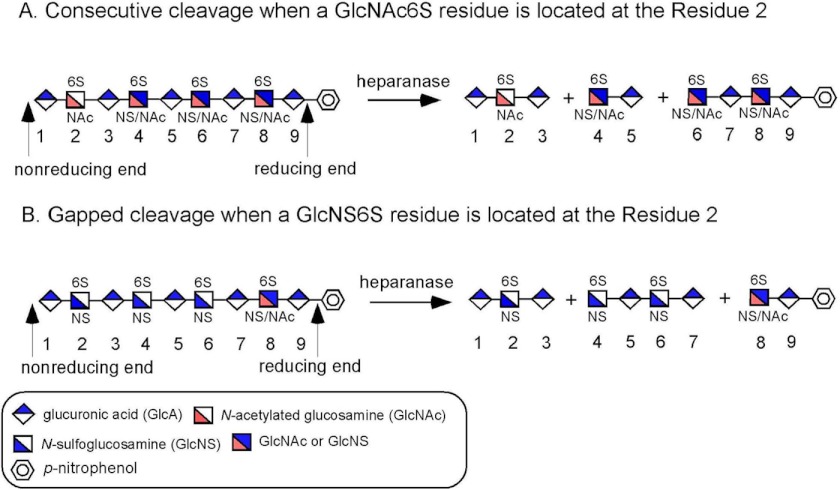

Carefully examination of the structures of the digestion products from six nonasaccharide substrates revealed that the heparanase cleavage sites depend on the substrate saccharide sequences (Fig. 3). Two groups were observed: consecutive cleavage and gapped cleavage. In the consecutive cleavage group, heparanase cleaved the glycosidic bond between residues 3 and 4 as well as the one between residues 5 and 6, whereas the bond between residues 7 and 8 remained intact, resulting in a trisaccharide, a disaccharide, and a pNP-tagged tetrasaccharide product. Four nonasaccharide substrates (Nona-4, -5, -7, and -8) displayed the consecutive cleavage pattern (Fig. 3A and Table 1). In the gapped cleavage group, heparanase cleaved the glycosidic bond between residues 3 and 4 and the one between residues 7 and 8, whereas the linkage of residues 5 and 6 was untouched, resulting in a trisaccharide, a tetrasaccharide, and a pNP-tagged disaccharide. Two nonasaccharides (Nona-3 and Nona-6) displayed the gapped cleavage pattern (Fig. 3B and Table 1). The notable structural differences among these nonasaccharides are located at the nonreducing end. In Nona-4, -5, -7, and -8 (consecutive cleavage group), GlcNAc6S is present at residue 2, whereas this residue is replaced with GlcNS6S in Nona-3 and Nona-6 (gapped cleavage group). Our data suggest that heparanase is capable of recognizing GlcNS6S and GlcNAc6S residues on the nonreducing side, which determines the cleavage susceptibility of the remaining sites.

FIGURE 3.

Schematic representation of heparanase cleavage of different nonasaccharide substrates. A, consecutive cleavage pattern. When GlcNAc6S is present at residue 2, heparanase displays the consecutive cleavage pattern, namely cleaving the linkages between residues 3 and 4 and residues 5 and 6. B, gapped cleavage pattern. When GlcNS6S is present at residue 2, heparanase displays the gapped cleavage pattern, namely cleaving the linkages between residues 3 and 4 and residues 7 and 8 and skipping the bond between residues 5 and 6. GlcA, GlcUA.

Heparanase Cleavage Site Preference

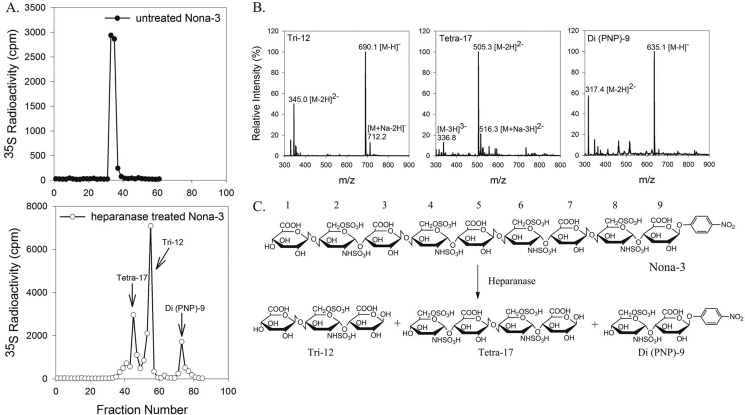

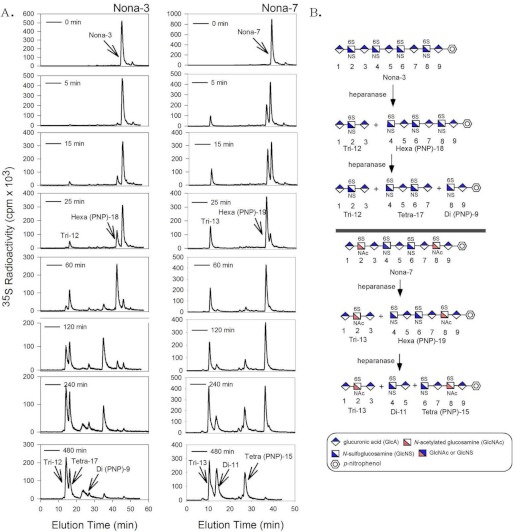

To establish the cleavage site preference, we performed a time course analysis of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction using Nona-3 (N-sulfation at the nonreducing end) and Nona-7 (N-acetylation at the nonreducing and reducing ends). First, we compared the digestion time courses for Nona-3 and Nona-7 using 35S-labeled substrates, followed by DEAE-HPLC analysis. For the 35S-labeled Nona-3 substrate, different 35S-labeled peaks emerged as the digestion proceeded (Fig. 4A). In the mean time, a decrease in the intensity of Nona-3 (eluted at 47 min) was observed. For example, two 35S-labeled peaks, which were eluted at 16 and 42 min from the DEAE-HPLC column, were observed when heparanase and the substrate were incubated for 25 min. As the incubation time was extended, the intensity of the 35S-labeled peak that eluted at 42 min decreased, and an additional 35S-labeled peaked emerged at 14 min (Fig. 4A). Very similar profiles were obtained when Nona-7 was incubated with heparanase at similar time intervals (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that intermediate oligosaccharides were formed during the digestion.

FIGURE 4.

DEAE-HPLC chromatograms of 35S-labeled Nona-3 and Nona-7 digested with heparanase at different times. Heparanase was incubated with 35S-labeled Nona-3 and Nona-7 at 0, 5, 15, 25, 60, 120, 240, and 480 min. The reaction was stopped, and the cleavage products were analyzed and separated by high resolution DEAE-HPLC. A, degradation of 35S-labeled Nona-3 and Nona-7 at 0–480 min by heparanase. B, upper panel, schematic identifying the cleavage products from the chemical reaction involved in the digestion of Nona-3 with heparanase. Lower panel, chemical reaction involved in the digestion of Nona-7 with heparanase. GlcA, GlcUA.

Second, we sought to determine the structures of the intermediates that resulted from partial digestions of unlabeled Nona-3 and Nona-7 by heparanase. For Nona-3, the digestion was stopped at 30 min, and the products were analyzed by ESI-MS (supplemental Fig. S10). Two products were identified: Tri-12 and Hexa(pNP)-18. Our results indicate that heparanase cleaves the glycosidic bond of Nona-3 that is located closer to the nonreducing end. For Nona-7, the digestion with heparanase was also stopped at 30 min, and the products were subjected to ESI-MS analysis (supplemental Fig. S11). Two oligosaccharides were identified: Tri-13 and Hexa(pNP)-19. Hence, our data suggest that heparanase cleaves the glycosidic bond closer to the nonreducing end to release a trisaccharide and a hexasaccharide. The resultant hexasaccharide was subsequently digested to the final products. Although the digestion of both Nona-3 and Nona-7 followed a similar degradation pathway, the initial rate of the first digestion step from nonasaccharide to hexasaccharide was significantly different. A significant portion of Nona-3 remained after 25 min of digestion, whereas only 15–20% of Nona-7 was present. On the other hand, in the later digestion step from hexasaccharide to tetrasaccharide, Hexa(pNP)-18 from Nona-3 disappeared much faster than Hexa(pNP)-19 from Nona-7.

The results from the time course study also suggest that heparanase cleaves distributively during the digestion of the segment with a repeating disaccharide unit of -GlcUA-GlcNS(or GlcNAc)6S-. In a distributive reaction, it is assumed that the substrate has to associate with the enzyme multiple times to undergo complete degradation. Therefore, the starting material and intermediate must compete for binding to the substrate to undergo degradation in a distributive reaction (19). This competition can be observed in the time course study (Fig. 4). In the heparanase degradation reactions, the nonasaccharide starting material has to compete with the trisaccharide and hexasaccharide for binding to heparanase to undergo further degradation. As a result of heparanase cleavage size dependence, the intermediate in both reactions cannot be degraded into the final product until all of the starting material is cleaved.

DISCUSSION

Heparanase is reportedly involved in a wide range of pathophysiological functions, including stimulating tumor metastasis, inflammatory responses, and autoimmune-mediated cell damage (20–22). These diversified functions of heparanase are attributed predominantly to the release of short HS fragments from the action of heparanase on HS present in the extracellular matrix. The degraded HS fragments bind to different growth factors and chemokines that regulate a series of cellular events. Therefore, understanding the substrate specificity of heparanase is essential for deciphering the roles of heparanase in regulating or stimulating diseases at the molecular levels.

In this study, we employed a selective library of oligosaccharides coupled with ESI-MS analysis to determine the substrate specificity of heparanase. Although HS has complex saccharide sequences, we focused only on substrates containing the disaccharide repeating units -GlcUA-GlcNS6S- and -GlcUA-GlcNAc6S-. This selection was based on the fact that -GlcUA-GlcNS6S- is known to be the site cleaved by heparanase (6, 11, 12). The structural domain of -IdoUA2S-GlcNS±6S- was not included in this study because this repeating unit is resistant to heparanase digestion (11, 12). We also chose to synthesize oligosaccharides containing the disaccharide unit -GlcUA-GlcNAc6S-, permitting us to examine the effects of the GlcNAc6S residue on substrate specificity. Collectively, the utilization of these substrates provided the opportunity to examine the substrate specificity of heparanase in greater detail. We discovered that heparanase cleaves both the -GlcUA-GlcNAc6S and -GlcUA-GlcNS6S- linkages. The susceptibility of the -GlcUA-GlcNAc6S- linkage to heparanase cleavage is somewhat surprising, as it was concluded to be resistant to heparanase cleavage using a synthetic polysaccharide substrate that contains the linkage -GlcUA-GlcNAc- or -GlcUA-GlcNAc6S- (but not -GlcUA-GlcNS6S-) (12). The discrepancy is likely due to the fact that the presence of -GlcUA-GlcNS6S- renders heparanase susceptible to the -GlcUA-GlcNAc6S- linkage. The sulfated saccharide sequence that influences susceptibility to heparanase cleavage has been found (12). For example, the -GlcUA-GlcNS- linkage is resistant to heparanase digestion; however, this linkage can be susceptible to heparanase cleavage when a 2-O-sulfated GlcUA residue is located nearby (12).

Our data indicate that heparanase is able to degrade the substrates in two modes: consecutive cleavage and gapped cleavage (Fig. 4). In the consecutive cleavage mode, heparanase removes three saccharide residues from the nonreducing end and then by removes two additional residues from the nonreducing end. In the gapped cleavage mode, heparanase also removes the three saccharide residues from the nonreducing end and skips the immediate next cleavage site, leaving a bigger fragment from the internal portion of the substrate. Heparanase displays the consecutive cleavage mode when a GlcNAc6S residue is present in the nonreducing end trisaccharide domain, whereas it displays the gapped cleavage mode when the GlcNAc6S residue is replaced with a GlcNS6S residue. Several mechanisms are possible. For example, heparanase has two distinct active sites. One site is responsible for the consecutive cleavage mode and prefers to accommodate the substrate with GlcNAc6S at the nonreducing end. Another site is responsible for the gapped cleavage mode and recognizes the substrate with GlcNS6S at the nonreducing end. However, only one active site has been identified based on the homology model (23). Alternatively, the trisaccharide domain from the nonreducing end serves as a modulator to direct heparanase to display the consecutive or gapped cleavage mode. Because our data show that heparanase releases the nonreducing end trisaccharide first before it further degrades the substrate, the latter mechanism warrants further investigation.

Our discovery of the distinct heparanase cleavage modes provides insights into the role of heparanase in controlling/preserving the functions of HS. HS consists of highly sulfated as well as low sulfated domains (2). Heparanase is believed to serve as an editing enzyme to excise HS to release those fragments with high potency to stimulate the actions of growth factors/growth factor receptors and chemokines/chemokine receptors (20). The highly sulfated domain, also known as the S-domain, contributes to the binding to growth factors and chemokines. This domain contains the disaccharide repeating units -IdoUA±2S-GlcNS6S- and -GlcUA-GlcNS6S- (24). Although the IdoUA±2S-GlcNS6S linkage is known to be resistant to heparanase action, the reason for the lack of cleavage of the GlcUA-GlcNS6S linkage in the S-domain is less clear. The discovery of the “gapped” cleavage mode could potentially contribute to preserve the integrity of the S-domain, especially playing a role in reducing cleavage of the -GlcUA-GlcNS6S- linkage. At this time, the precise link between different cleavage modes and the regulation of HS degradation remains elusive. Nevertheless, these results should advance the understanding of the regulation of HS biosynthesis and the intimate relationship between HS and heparanase. Further investigation on the mechanism that directs heparanase cleavage will aid in deciphering the wide range of pathophysiological functions of heparanase in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yongmei Xu (University of North Carolina) for help in synthesizing oligosaccharide substrates and Dr. Israel Vlodavsky (Ruth and Bruce Rappaport Faculty of Medicine, Haifa, Israel) for providing the information for preparing the recombinant heparanase expression construct.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant HL094463.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S11 and Table 1.

- HS

- heparan sulfate

- GlcUA

- glucuronic acid

- IdoUA

- iduronic acid

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- pNP

- p-nitrophenol

- GlcNTFA

- N-trifluoroacetylglucosamine

- GlcNS

- N-sulfoglucosamine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kreuger J., Spillmann D., Li J. P., Lindahl U. (2006) Interactions between heparan sulfate and proteins: the concept of specificity. J. Cell Biol. 174, 323–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gallagher J. T. (2001) Heparan sulfate: growth control with a restricted sequence menu. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 357–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bame K. J. (2001) Heparanases: endoglycosidases that degrade heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Glycobiology 11, 91R–98R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peterson S. P., Frick A., Liu J. (2009) Designing of biologically active heparan sulfate and heparin using an enzyme-based approach. Nat. Prod. Rep. 26, 610–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vlodavsky I., Ilan N., Naggi A., Casu B. (2007) Heparanase: structure, biological functions, and inhibition by heparin-derived mimetics of heparan sulfate. Curr. Pharm. Des. 13, 2057–2073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pikas D. S., Li J. P., Vlodavsky I., Lindahl U. (1998) Substrate specificity of heparanases from human hepatoma and platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 18770–18777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bernfield M., Götte M., Park P. W., Reizes O., Fitzgerald M. L., Lincecum J., Zako M. (1999) Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 729–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bashkin P., Neufeld G., Gitay-Goren H., Vlodavsky I. (1992) Release of cell surface-associated basic fibroblast growth factor by glycosylphosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C. J. Cell. Physiol. 151, 126–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vlodavsky I., Bar-Shavit R., Ishai-Michaeli R., Bashkin P., Fuks Z. (1991) Extracellular sequestration and release of fibroblast growth factor: a regulatory mechanism? Trends Biochem. Sci. 16, 268–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vlodavsky I., Elkin M., Abboud-Jarrous G., Levi-Adam F., Fuks L., Shafat I., Ilan N. (2008) Heparanase: one molecule with multiple functions in cancer progression. Connect. Tissue Res. 49, 207–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Okada Y., Yamada S., Toyoshima M., Dong J., Nakajima M., Sugahara K. (2002) Structural recognition by recombinant human heparanase that plays critical roles in tumor metastasis. Hierarchical sulfate groups with different effects and the essential target disulfated trisaccharide sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42488–42495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peterson S. B., Liu J. (2010) Unraveling the specificity of heparanase-utilizing synthetic substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 14504–14513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu R., Xu Y., Chen M., Weïwer M., Zhou X., Bridges A. S., DeAngelis P. L., Zhang Q., Linhardt R. J., Liu J. (2010) Chemoenzymatic design of heparan sulfate oligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 34240–34249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xu Y., Masuko S., Takieddin M., Xu H., Liu R., Jing J., Mousa S. A., Linhardt R. J., Liu J. (2011) Chemoenzymatic synthesis of homogeneous ultralow molecular weight heparins. Science 334, 498–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nardella C., Lahm A., Pallaoro M., Brunetti M., Vannini A., Steinkühler C. (2004) Mechanism of activation of human heparanase investigated by protein engineering. Biochemistry 43, 1862–1873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu J., Shriver Z., Blaiklock P., Yoshida K., Sasisekharan R., Rosenberg R. D. (1999) Heparan sulfate d-glucosaminyl 3-O-sulfotransferase 3A sulfates N-unsubstituted glucosamine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 38155–38162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Steinkuhler C., Lahm A., Pallaoro M., Nardella C. (January 11, 2007) U.S. Patent 2007/0009989

- 18. van den Hoven M. J., Rops A. L., Vlodavsky I., Levidiotis V., Berden J. H., van der Vlag J. (2007) Heparanase in glomerular diseases. Kidney Int. 72, 543–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Buschhorn B. A., Peters J. M. (2006) How APC/C orders destruction. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 209–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barash U., Cohen-Kaplan V., Dowek I., Sanderson R. D., Ilan N., Vlodavsky I. (2010) Proteoglycans in health and disease: new concepts for heparanase function in tumor progression and metastasis. FEBS J. 277, 3890–3903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lerner I., Hermano E., Zcharia E., Rodkin D., Bulvik R., Doviner V., Rubinstein A. M., Ishai-Michaeli R., Atzmon R., Sherman Y., Meirovitz A., Peretz T., Vlodavsky I., Elkin M. (2011) Heparanase powers a chronic inflammatory circuit that promotes colitis-associated tumorigenesis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 1709–1721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ziolkowski A. F., Popp S. K., Freeman C., Parish C. R., Simeonovic C. J. (2012) Heparan sulfate and heparanase play key roles in mouse β cell survival and autoimmune diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 132–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sapay N., Cabannes E., Petitou M., Imberty A. (2012) Molecular model of human heparanase with proposed binding mode of a heparan sulfate oligosaccharide and catalytic amino acids. Biopolymers 97, 21–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Staples G. O., Shi X., Zaia J. (2010) Extended N-sulfated domains reside at the nonreducing end of heparan sulfate chains. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18336–18343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]