Abstract

Objectives. We examined the relationship between unemployment and mortality in Germany, a coordinated market economy, and the United States, a liberal market economy.

Methods. We followed 2 working-age cohorts from the German Socio-economic Panel and the US Panel Study of Income Dynamics from 1984 to 2005. We defined unemployment as unemployed at the time of survey. We used discrete-time survival analysis, adjusting for potential confounders.

Results. There was an unemployment–mortality association among Americans (relative risk [RR] = 2.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.7, 3.4), but not among Germans (RR = 1.4; 95% CI = 1.0, 2.0). In education-stratified models, there was an association among minimum-skilled (RR = 2.6; 95% CI = 1.4, 4.7) and medium-skilled (RR = 2.4; 95% CI = 1.5, 3.8) Americans, but not among minimum- and medium-skilled Germans. There was no association among high-skilled Americans, but an association among high-skilled Germans (RR = 3.0; 95% CI = 1.3, 7.0), although this was limited to those educated in East Germany. Minimum- and medium-skilled unemployed Americans had the highest absolute risks of dying.

Conclusions. The higher risk of dying for minimum- and medium-skilled unemployed Americans, not found among Germans, suggests that the unemployment–mortality relationship may be mediated by the institutional and economic environment.

The relationship between unemployment and mortality has been a well-studied phenomenon. Unemployment has been found to be associated with all-cause mortality1–4 for both men5–7 and women,8,9 for older workers,10–14 for cause-specific outcomes,15,16 and after controls for health selection into unemployment.17–20 Some studies have found that the relationship between unemployment and mortality is smaller during times of high unemployment than in times of low unemployment21,22; studies of plant closure conducted during times of high unemployment have found a consistent relationship.23,24

Unemployment has almost always been viewed as an individual-level risk factor on health within the context of a single country or economy. When context has been considered it has been to investigate whether the effect of unemployment on health is different during times or places with high unemployment compared with low unemployment.22,25,26 Unemployment may influence health through material (e.g., loss of income) and psychosocial (e.g., loss of individual and social identity) pathways. These pathways are embedded in and influenced by societal and institutional context at every point, from determining who is unemployed (and who participates in the labor market), the meaning of unemployment, the material effect of unemployment, and the future employment consequences of unemployment.

Recent scholarship in health inequalities has begun to characterize the structural and contextual features of a society that lead to better or worse population health outcomes.27,28 This research has emphasized the importance of welfare-regime type as the principal independent variable in explaining variation in health inequalities among countries. Welfare-regime typologies classify countries according to how the state provides social and economic protection to its citizens. Although there are many welfare-regime typologies,29 Esping-Andersen’s30 typology that classifies countries into social democratic (universal provision), conservative (class-based provision), and liberal or residual (mean-tested provision) welfare-regime clusters is the most common.

Few studies have examined whether the relationship between unemployment and health varies across welfare-regime type. Bambra and Eikemo found that the unemployed in liberal welfare regimes had the highest odds of reporting poorer self-reported health status for both unemployed men and women, but that high odds ratios were also found for unemployed men in conservative welfare regimes and women in social democratic welfare regimes.31 Cooper et al. examined the relationship between unemployment and exit into poor health in 14 European countries, but did not find any relationship across welfare regimes.32,33 Rodriguez examined whether the receipt of means-tested (i.e., welfare or social assistance) and unemployment benefits moderated the relationship between unemployment and self-assessed health in Germany (a conservative welfare regime), the United Kingdom, and the United States (2 liberal welfare regimes).34 Regular unemployment benefits moderated the relationship between unemployment and health in all 3 countries compared with the unemployed in receipt of means-tested benefits. The unemployed not in receipt of any benefits in the United States also reported poorer self-assessed health.

Hall and Soskice’s Varieties of Capitalism typology35 provides a more relevant way of understanding how the institutional environment may affect the health of the unemployed because it is based, more directly than Esping-Andersen’s typology, on the conditions of employment and unemployment. Economies of high-income countries are grouped into coordinated market economies (CMEs) and liberal market economies (LMEs) that have different production specializations, similar economic growth and aggregate levels of wealth, but different economic and labor market institutions. Within CMEs and LMEs there is an interdependent relationship between the coordinating features of the market economy, the goods and services produced, the skills required by workers, and the potential future consequences of unemployment. The CMEs (e.g., Germany and Sweden) are characterized by collaboration among firms, trade unions, and other market actors and specialize in the production of goods and services that require a high degree of firm- or industry-specific skills and require workers that are technically or vocationally trained. High levels of employment protection (i.e., restrictions on terminating employees) and unemployment protection (i.e., the availability and level of unemployment benefits) safeguard the educational investment of workers, as once unemployed there may not be demand for their skills in other firms or industries.36

In LMEs, by contrast, competitive market institutions predominate, including a flexible labor market with low levels of unemployment and employment protection. These economies specialize in goods and services that require general skills that are readily transferred across firms and industries. In accordance, the risk of unemployment and its effect on the health of the unemployed may vary across countries and within countries by skill level, depending on the protections provided to the unemployed and the opportunities for reemployment. Specifically, in LMEs the flexible labor market advantages those with high general skills (i.e., a university degree), whereas in CMEs the more coordinated labor market is structured to support workers with firm- and industry-specific vocational skills.37

We examined whether the relationship between unemployment and mortality differs between Germany, a CME, and the United States, an LME, with 2 comparable working-age cohorts. We hypothesized that the higher levels of unemployment protection in Germany will mediate the effect of unemployment on mortality compared with the United States and that the gradient in the risk of unemployment on mortality by general educational status will be steeper in the United States compared with Germany.

METHODS

We used the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP) and the American Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to derive 2 working-age cohorts. The PSID and GSOEP are longitudinal studies that follow households over time with the aim of collecting information on a broad range of economic and social conditions.38,39 The PSID was an annual survey from 1968 to 1997 that was trimmed in sample size and thereafter a biennial survey. The GSOEP annually surveys individuals from West Germany from 1984 onward and was expanded to include individuals from East Germany in 1991 after German reunification.

We designed the cohorts derived from the surveys to be as comparable as possible in terms of follow-up, eligible individuals, and measures across the 2 surveys. Entrance into the cohort was dynamic to reflect that individuals entered the underlying surveys at different times (e.g., the East German cohort) or met the cohort eligibility requirements after the initial baseline year in 1984. We dropped the “Latino or Hispanic” sample in the PSID as it was only followed for 5 years between 1990 and 1995, and thereafter mortality was no longer ascertained. We also dropped the “Foreigner” sample in the GSOEP because of incomplete mortality ascertainment.

Eligible individuals were required to be aged between 18 and 64 years at the start of baseline and have a minimum of 3 waves of data. We restricted baseline to 1984 to 1995 for both cohorts and defined it as the first 2 waves of data to establish health and employment histories. Individuals were followed until death or loss to follow-up or were censored in 2005. The German cohort included 10 754 individuals and 117 123 person years, yielding an average follow-up of 13.4 years. The American cohort included 9523 individuals and 98 721 person years, yielding an average follow-up of 12.7 years.

We defined death as all-cause mortality in any year between the last year of follow-up for an individual and the last year of follow-up of the study. There were 879 and 876 deaths in the German and American cohorts, respectively. Unemployment was defined as being unemployed at the time of the survey. Unemployed persons in Germany who also reported part-time work or paid vocational training were considered employed for consistency with the definition of unemployment in the PSID. Current employment was the reference category; not working or out of the labor force was also included to create a mutually exclusive set of labor force statuses that could vary across years.

We defined 6 groups of covariates: age and gender, other demographics, household income, education status, occupation, and health status in the previous year. Other demographics included spouse and marital status as categorical variables and household size and number of children as continuous variables. East German and immigrant (born in Germany vs elsewhere) and race (Black, White [reference], or other) were variables specific to the German and American cohort, respectively.

We defined household income, scaled to 2005 US dollars or euros, as the log of household income inclusive of all income sources, less reported taxes. We used household income in the previous year in the models, because current-year income may be on the pathway between unemployment and mortality. We defined a 3-level education variable on the basis of skill level and skill type.40,41 Minimal-skilled were those with less than high-school education or those with a compulsory general elementary certificate. Medium-skilled were those with a high-school certificate, some college, or a vocational certificate, or those with basic or intermediate vocational or general qualifications. High-skilled were those with tertiary general or vocational qualifications. We defined occupation as no occupation (applied if an individual was out of the labor force at baseline); professional and technical occupation; business and sales occupation; service occupation; agriculture, forestry, and mining occupation; or a manufacturing occupation.

We derived health status in the year before the survey from self-reported health status (PSID) or health satisfaction (GSOEP) and disability status. Health satisfaction was used in the German cohort as self-reported health status and was only available from 1994 onward. We used health status in the previous year because health status contemporaneous with labor force status may be on the pathway between current labor force status and mortality.

We coded mortality at the yearly level, implying interval censoring, and also ascertained it for different periods of follow-up given the dynamic nature of cohort entry. To address the structure of the data we used a discrete-time survival approach, with a complementary log–log link, to model the risk of unemployment on mortality in each survey wave.42–44 This approach, which provides a relative risk and is the discrete-time equivalent of the Cox proportional hazard model, is appropriate when one is modeling events summarized to a yearly interval that take place in continuous time. To account for the differences in years of follow-up attributable to the dynamic nature of the cohorts, we introduced the natural logarithm of time at risk (i.e., years followed) as an exposure offset to standardize the estimated hazard. To account for the multistage sample frame of the surveys, we also examined a random effect at the level of the primary sample unit. The preferred models presented in the results were based on evidence of correlation at the level of the primary sample unit and model goodness-of-fit statistics.

We estimated models separately for German and American cohorts and by skill level. To control for country-specific differences, we stratified the German cohort into those from East and West Germany and we stratified the American cohort by race into Black, and White or other. To examine the role of health selection into unemployment, we also estimated models for a subcohort restricted to those in good health in both baseline years.

RESULTS

There were differences in baseline characteristics across the cohorts (Table 1). The German cohort was older than the American cohort, particularly for the unemployed. More unemployed individuals in the American cohort were of minimum skill. Employed Germans were more likely to be in manufacturing occupations, whereas employed Americans are more likely to be in professional and technical occupations or business and sales occupations. Unemployed Americans had half the household income of employed Americans, whereas unemployed Germans had two thirds the household income of employed Germans. Unemployed and employed Germans reported similar levels of health satisfaction at baseline, but unemployed Americans reported lower self-reported health status.

TABLE 1—

Descriptive Statistics at Baseline Stratified by Current Labor Force Status and Study Country: German Socio-Economic Panel and US Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1984–2005

| Germany (n = 10 754) |

United States (n = 9523) |

|||||

| Characteristic | Working (72.1%) | Unemployed (5.3%) | Not Working (22.5%) | Working (70.3%) | Unemployed (8.5%) | Not Working (21.4%) |

| Mean age, y | 37.3 | 38.1 | 44.2 | 34.1 | 29.9 | 40.0 |

| Male | 0.56 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.19 |

| East German | 0.30 | 0.41 | 0.19 | |||

| Immigrant | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.09 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 0.61 | 0.32 | 0.53 | |||

| Black | 0.34 | 0.64 | 0.41 | |||

| Other | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.32 | 0.64 |

| Single | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.48 | 0.18 |

| Divorced or separated | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Widowed | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| Household size, mean no. | 2.87 | 2.75 | 2.91 | 2.73 | 2.66 | 3.18 |

| Children, mean no. | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.98 | 1.12 |

| Skill level | ||||||

| Minimum | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 0.39 |

| Medium | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.51 |

| High | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Occupationa | ||||||

| None | 0.05 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Professional and technical | 0.16 | 0.19 | ||||

| Business or sales | 0.30 | 0.34 | ||||

| Services | 0.15 | 0.14 | ||||

| Agriculture, forestry, or mining | 0.03 | 0.04 | ||||

| Manufacturing | 0.30 | 0.26 | ||||

| Health | ||||||

| Excellent | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.19 |

| Good | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.23 |

| Satisfactory | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.27 |

| Fair | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.21 |

| Poor | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.11 |

| Disabled | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.33 |

| Mean household income,b $ | 31 614.0 | 21 682.9 | 24 851.8 | 40 652.9 | 20 280.7 | 31 650.9 |

Note. Numbers in table are proportions unless otherwise distinguished.

Occupation at baseline is only valid for those currently working.

Germany, 2005 euros; United States, 2005 US dollars.

Table 2 shows the results for the German and American cohorts adjusted for age and gender and all other variables. The relative risk (RR) of dying for unemployed Germans compared with employed Germans was 2.2 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.5, 3.1) in the age and gender model and 1.4 (95% CI = 1.0, 2.0) in the full model reflecting a 40% increased chance of dying. The relative risk of dying for unemployed Americans compared with employed Americans was 3.7 (95% CI = 2.6, 5.2) in the age and gender model and 2.4 (95% CI = 1.7, 3.4) in the full model reflecting a 140% increased chance of dying.

TABLE 2—

Relative Risk of Dying for Current Labor Force Status for the German and American Cohorts, Adjusted for Age and Gender and Other Potential Confounders: German Socio-Economic Panel and US Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1984–2005

| German Cohort (n = 10 754) |

American Cohort (n = 9523) |

|||

| Variables | Age and Gender, RR (95% CI) | Fully Adjusted, RR (95% CI) | Age and Gender, RR (95% CI) | Fully Adjusted, RR (95% CI) |

| Employment status (Ref = employed) | ||||

| Unemployed | 2.15*** (1.50, 3.07) | 1.42 (0.98, 2.04) | 3.66*** (2.60, 5.16) | 2.35*** (1.67, 3.34) |

| Not working | 3.01*** (2.44, 3.70) | 2.01*** (1.61, 2.51) | 4.24*** (3.47, 5.15) | 2.43*** (1.95, 3.01) |

| Age | 1.06*** (1.05, 1.05) | 1.05*** (1.05, 1.05) | 1.05*** (1.04, 1.06) | 1.05*** (1.04, 1.06) |

| Male (Ref = female) | 2.12*** (1.84, 2.44) | 2.47*** (2.02, 3.02) | 1.86*** (1.62, 2.13) | 1.72*** (1.40, 2.23) |

| East German (Ref = West German) | 1.28** (1.07, 1.53) | |||

| Immigrant (Ref = German-born) | 0.8 (0.59, 1.12) | |||

| Race/ethnicity (Ref = White) | ||||

| Black | 1.20* (1.02, 1.42) | |||

| Other | 0.86 (0.61, 1.22) | |||

| Spouse (Ref = head) | 0.94 (0.76, 1.16) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | ||

| Marital status (Ref = married) | ||||

| Single | 1.49* (1.05, 2.12) | 1.60** (1.20, 2.12) | ||

| Divorced or separated | 1.36* (1.02, 1.81) | 1.05 (0.82, 1.34) | ||

| Widowed | 1.12 (0.87, 1.45) | 1.24 (0.97, 1.59) | ||

| Household size, no. | 1.17** (1.05, 1.31) | 0.99 (0.90, 1.08) | ||

| Children, no. | 0.72*** (0.59, 0.86) | 0.88 (0.76, 1.02) | ||

| Household income (t-1, log) | 0.83*** (0.75, 0.91) | 0.93* (0.86, 0.99) | ||

| Skill level (Ref = high skill) | ||||

| Minimum skill | 1.37* (1.04, 1.80) | 0.92 (0.69, 1.21) | ||

| Medium skill | 1.19 (0.95, 1.59) | 1.11 (0.86, 1.42) | ||

| Occupation (Ref = professional or management) | ||||

| None | 1.58** (1.16, 2.15) | 1.12 (0.84, 1.48) | ||

| Business or sales | 1.08 (0.79, 1.47) | 0.92 (0.670, 1.22) | ||

| Services | 0.99 (0.70, 1.41) | 1.0 (0.73, 1.37) | ||

| Agriculture, forestry, or mining | 1.10 (0.70, 1.82) | 1.18 (0.79, 1.78) | ||

| Manufacturing | 1.00 (0.72, 1.37) | 1.21 (0.91, 1.63) | ||

| Health (Ref = excellent) | ||||

| Good (t-1) | 0.92 (0.68, 1.25) | 1.47* (1.03, 2.08) | ||

| Satisfactory (t-1) | 1.52** (1.12, 2.04) | 2.03*** (1.45, 2.84) | ||

| Fair (t-1) | 1.90*** (1.38, 2.60) | 3.81*** (2.68, 5.41) | ||

| Poor (t-1) | 3.81*** (2.77, 5.23) | 7.25*** (4.98, 10.56) | ||

| Disabled (Ref = not disabled; t-1) | 1.43*** (1.22, 1.67) | 1.10 (0.93, 1.32) | ||

| Person years | 117 123 | 117 123 | 99 175 | 99 175 |

| AIC | 9956.3 | 9658.0 | 9308.3 | 8907.9 |

| BIC | 10 004.7 | 9909.4 | 9355.8 | 9155.0 |

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; CI = confidence interval; RR = relative risk. The statistical model used is the complementary log–log model and includes the log of years followed as an exposure offset.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

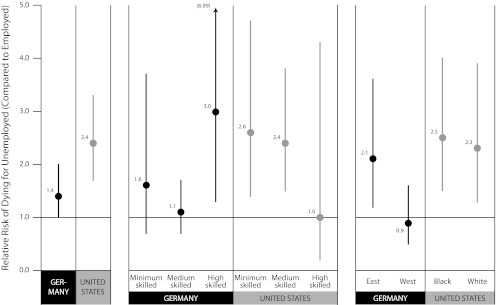

There was marked effect modification by skill level in both the German and American cohorts (Figure 1). The relative risk of dying was highest for unemployed high-skilled Germans and minimum-skilled Americans and lowest for unemployed medium-skilled Germans and high-skilled Americans. Compared with the full cohort, unemployed minimum-skilled Germans had a similar relative risk (1.6; 95% CI = 0.7, 3.7) to the full sample, whereas the relationship for the unemployed medium-skilled was close to 1 (1.1; 95% CI = 0.7, 1.7). By contrast, unemployed high-skilled Germans had a large relative risk (3.0; 95% CI = 1.3, 7.0). For unemployed minimum-skilled (RR = 2.6; 95% CI = 1.4, 4.7) and medium-skilled (RR = 2.4; 95% CI = 1.5, 3.8) Americans the association was similar to that of the full cohort, but there was no association for the unemployed high-skilled Americans (RR = 1.0; 95% CI = 0.2, 4.3).

FIGURE 1—

Summary of the relative risks of dying for the unemployed for the German and American cohorts: German Socio-Economic Panel and US Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1984–2005.

German-specific analysis that stratified the cohort by whether an individual was from East or West Germany found large effect modification. The relative risk of mortality for unemployed East Germans was 2.1 (95% CI = 1.2, 3.6) compared with employed East Germans, whereas there was no association for unemployed West Germans (RR = 0.9; 95% CI = 0.5, 1.6). Moreover, the relative risk found for unemployed high-skilled Germans was entirely attributable to the higher association among East Germans. By contrast, stratifying the analysis by race in the American cohort did not yield evidence of effect modification. The relative risk of mortality for unemployed Blacks was 2.5 (95% CI = 1.5, 4.0) and for unemployed Whites or other was 2.3 (95% CI = 1.3, 2.9) compared with employed Blacks and Whites or other, respectively.

Sensitivity testing that excluded those in poor health or those not working at baseline did not change the pattern of association. The relative risk of dying was higher in the good health subcohort (German: RR = 1.7; 95% CI = 1.1, 2.6; American: RR = 3.0; 95% CI = 2.0, 4.4) compared with the full cohort for both study countries. Moreover, models that included a random effect to account for correlation because of the multistage stratified design of the surveys did not yield any differences in the fixed effect parameter estimates.

DISCUSSION

We found an increased risk of dying for the unemployed in both Germany and America, but in almost all cases the relative risk was higher for the American unemployed. In Germany there was an elevated risk for the high-skilled and for East Germans compared with other unemployed groups, whereas for the American unemployed there was a consistent relative risk of dying among all groups except for the high-skilled (Figure 1). The higher risk of dying for the unemployed in the United States compared with those in Germany supports the hypothesis that the institutional environment, including higher levels of unemployment and employment protection, mediates the unemployment–mortality relationship.

The results from this study are also consistent with the one other study that used the GSOEP, which found no relationship between current unemployment and mortality in Germany.45 The results from this study fall within the range of risk ratios found in other American studies. One study found a higher risk ratio of greater than 3,5 with most studies finding a risk ratio between 1.5 and 2.2,4,11,19,46 and a few finding no association.10,20

The education-stratified results are consistent with the hypothesis that there would be a stronger unemployment–mortality gradient by skill level in the United States. In the American cohort there was no relationship between unemployment and mortality for the high-skilled. It appears that individuals with a high level of education may be best suited to take advantage of the more flexible labor markets within the United States. The high-skilled were also more likely to receive benefits, when unemployed, than were those of lower skill levels. These individuals may also have other resources (e.g., savings, familial resources, and social or business contacts from educational or professional organizations) to draw upon that would buffer the effect of unemployment on health. Furthermore, the drop in household income for unemployed high-skilled Americans was smaller than for those of lower skill levels.

Both the unemployed minimum- and medium-skilled had an elevated relative risk of dying in the United States. In Germany, the unemployed medium-skilled had the lowest relative risk of dying. This is the strongest evidence that institutional environment can affect the relationship between unemployment and health as institutional protection is targeted toward medium- (and vocationally) skilled workers in Germany.36 Both medium-skilled groups are the largest group of workers and also have the largest number of unemployed persons in both cohorts (although the unemployment rate is highest among the minimum-skilled in both countries). Furthermore, the contrast between the 2 medium-skilled groups is striking with respect to receipt of unemployment compensation and household income that may be mediators of the unemployment–mortality relationship. The unemployed medium-skilled in Germany had a median household income of 70% of their employed counterparts and 75% of them reported receiving unemployment compensation, whereas the unemployed medium-skilled in the United States had a median household income of 48% of their employed counterparts and only 19% reported receiving unemployment compensation.

The results are also robust to control for health selection in that similar or higher relative risks were observed in the good health subcohort. The higher relative risk is attributable, in part, to the lower absolute risk of death in the cohort given that those in poor health at baseline were not in the subcohort. The relationship between the employed and unemployed who were healthy at baseline indicates that health selection into unemployment does not account for the observed relationship between unemployment and mortality. The argument that health selection has been sufficiently accounted for hinges on the validity of the baseline health status measures. Two points support the argument that they are valid. First, the health status measures were the strongest predictors of mortality in the model; second, baseline health and labor force exclusions were based on 2 years of data and as such those in good health were persistently in good health.

The American results were not sensitive to stratification by race; unemployed Blacks and Whites had similar relative risks compared with their employed counterparts. Notwithstanding this, the American results taken together suggest that race may play a role in the unemployment and health relationship. In the United States, Blacks are more likely to become unemployed than are Whites (e.g., the unemployment rate for Blacks in 2005 was 9.5%, whereas it was 4.4% for Whites).47 Indeed, the proportion of mortality attributable to unemployment (i.e., adjusted population attributable fraction48) is higher for Blacks than for Whites given the higher prevalence of unemployment for Blacks. Moreover, Blacks have a higher baseline risk of dying. This suggests that country and institutional patterns relating to unemployment may, in part, be codetermined by the legacy of racism and segregation in the United States.

East Germans have an increased risk of being unemployed and an increased relative risk of dying associated with unemployment. Moreover, the elevated risk of mortality found for high-skilled unemployed Germans is driven by deaths among unemployed high-skilled East Germans. The results from Germany suggest that for West German workers, who have spent their entire working life embedded within the CME institutional environment, the institutional supports are effective. For unemployed East Germans, who come from a different institutional environment (a planned economy), the institutional supports are not as effective.

Although an association between unemployment and mortality was found in the United States and for some groups in Germany, this study does not establish whether this relationship is causal. Unemployment may be a marker for other mechanisms and for the accumulation of socioeconomic disadvantage that may affect health. For example, workers in hazardous jobs may be more likely to face involuntary job loss.49 Unemployed workers are also more likely to come from groups already vulnerable to negative health outcomes (i.e., unemployment is concentrated among the low-waged, the minimally skilled, East Germans in Germany, and Blacks in the United States). Disentangling the confluence of these determinants of health is challenging, but insight can be gained from the comparative study design by moving beyond the comparison of relative risks across countries and comparing the average predicted risk of dying for unemployed groups across countries.

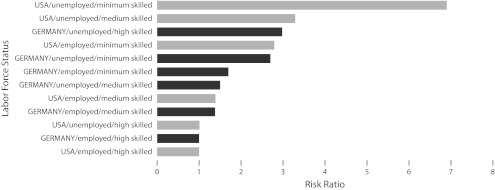

Figure 2 depicts rate ratios by labor force status across educational stratum and study country that are derived from the predicted hazard of dying evaluated at the mean of other covariates. Unemployed minimum-skilled Americans are about 7 times more likely to die than are employed high-skilled Germans and employed or unemployed high-skilled Americans. There is also a doubling of risk between the unemployed medium-skilled Germans and Americans. The differences in risk by employment status and skill level support the idea that distributional and institutional factors contribute to the flattening of the socioeconomic–health gradient.50,51 Unemployed minimum- and medium-skilled Americans may be less likely to have had access to health care insurance while employed and are more likely to lose it once unemployed compared with the high-skilled. Access to health insurance and health care may be an institutional feature that explains steeper socioeconomic gradients in mortality in the United States compared with Germany and other countries.52 Other LMEs, such as Canada and Australia, have universal health insurance and future research should examine the role that access to health insurance may have in mediating the health effects of unemployment among LME countries.

FIGURE 2—

Rate ratio of dying by current employment status and skill level: German Socio-Economic Panel and US Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1984–2005.

The strengths in this study were the focus on creating comparable cohorts across study countries and the emphasis on creating similar labor market and educational variables. This study used a full range of covariates spanning demographic, socioeconomic status, and health status variables to control for potential confounding and health selection into unemployment. Some measures across countries, however, were different—in particular, the health status measures. Differences in attrition and measurement error across the studies could have also introduced differential bias into the study. There may be other variables not included in the models, such as health-related behaviors, that might have confounded the relationship between unemployment and mortality both within and across study cohorts.

The findings from this study support the idea that context matters to the health of the unemployed. In Germany, a CME with high levels of employment and unemployment protection, the unemployment–mortality association is only found for East Germans. For West German workers, who have spent their entire career within this environment, there is no association. In the United States there is no unemployment–mortality association for the high-skilled who are best positioned to take advantage of the flexible labor market found in LMEs. For minimum- and medium-skilled workers, unemployment comes with an increased risk of death. In particular, those at the bottom of the labor market and educational hierarchy—the minimum-skilled unemployed—are much more likely to die, reflecting the accumulation of health disadvantage within this group in the United States. The Varieties of Capitalism framework is predicated on the idea that there are 2 macroeconomic equilibria that lead to similar levels of aggregate national wealth and economic growth. This study provides evidence that the different ways for organizing high-income capitalist economies may also have profound distributional consequences when it comes to workers’ health.

Acknowledgments

C. B. McLeod was supported by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Doctoral and Post-Doctoral Fellowships. C. B. McLeod and C. Hertzman were supported by the Successful Societies Program of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. Y. C. MacNab was supported by the Child and Family Research Institute and the National Science and Engineering Research Council.

We are grateful for the assistance of Dawn Mooney of the Centre for Health Services and Policy Research at the University of British Columbia for creating the figures in the article.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the Behavioural Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia (H06-04021)

References

- 1.Iversen L, Andersen O, Andersen PK, Christoffersen K, Keiding N. Unemployment and mortality in Denmark, 1970–80. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987;295(6603):879–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norström T. Deriving relative risks from aggregate data. 2. An application to the relationship between unemployment and suicide. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1988;42(4):336–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa G, Segnan N. Unemployment and mortality. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987;294(6586):1550–1551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cubbin C, LeClere FB, Smith GS. Socioeconomic status and the occurrence of fatal and nonfatal injury in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(1):70–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavis JN. Unemployment and mortality; a longitudinal study in the United States. Toronto, ON: Institute for Work Health; 1998. Working paper 63.

- 6.Bethune A. Economic activity and mortality of the 1981 Census cohort in the OPCS Longitudinal Study. Popul Trends. 1996;(83):37–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nylén L, Voss M, Floderus B. Mortality among women and men relative to unemployment, part time work, overtime work, and extra work: a study based on data from the Swedish twin registry. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58(1):52–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saarela J, Finnas F. Mortality inequality in two native population groups. Popul Stud (Camb). 2005;59(3):313–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blomgren J, Valkonen T. Characteristics of urban regions and all-cause mortality in working age population: effect of social environment and interactions with individual unemployment. Demogr Res. 2007;17:109–134 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayward MD, Grady WR, Hardy MA, Sommers D. Occupational influences on retirement, disability, and death. Demography. 1989;26(3):393–409 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sorlie PD, Backlund E, Keller JB. US mortality by economic, demographic, and social characteristics: the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(7):949–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moser KA, Goldblatt PO, Fox AJ, Jones DR. Unemployment and mortality: comparison of the 1971 and 1981 longitudinal study census samples. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987;294(6564):86–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osler M, Christensen U, Lund R, Gamborg M, Godtfredsen N, Prescott E. High local unemployment and increased mortality in Danish adults; results from a prospective multilevel study. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60(11):e16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stefansson C-G. Long-term unemployment and mortality in Sweden, 1980–1986. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(4):419–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kposowa AJ. Unemployment and suicide: a cohort analysis of social factors predicting suicide in the US National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Psychol Med. 2001;31(1):127–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johansson SE, Sundquist J. Unemployment is an important risk factor for suicide in contemporary Sweden: an 11-year follow-up study of a cross-sectional sample of 37,789 people. Public Health. 1997;111(1):41–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerdtham UG, Johannesson M. A note on the effect of unemployment on mortality. J Health Econ. 2003;22(3):505–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gognalons-Nicolet M, Derriennic F, Monfort C, Cassou B. Social prognostic factors of mortality in a random cohort of Geneva subjects followed up for a period of 12 years. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(3):138–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiuila O, Mieszkowski P. The effects of income, education and age on health. Health Econ. 2007;16(8):781–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers RG, Hummer RA, Nam CB. Living and Dying in the USA, Behavioral, Health and Social Differentials of Adult Mortality. New York, NY: Academic Press; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martikainen PT, Valkonen T. Excess mortality of unemployed men and women during a period of rapidly increasing unemployment. Lancet. 1996;348(9032):909–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martikainen P, Maki N, Jantti M. The effects of unemployment on mortality following workplace downsizing and workplace closure: a register-based follow-up study of Finnish men and women during economic boom and recession. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(9):1070–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eliason M, Storrie D. Does Job Loss Shorten Life? Working Papers in Economics No. 153. Goteborg, Sweden: School of Business, Economics and Law, Goteborg University; 2007.

- 24.Sullivan D, Wachter TV. Mortality, Mass-Layoffs, and Career Outcomes: An Analysis Using Administrative Data. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2007. Working Paper Series 13626 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novo M, Hammarstrom A, Janlert U. Health hazards of unemployment—only a boom phenomenon? A study of young men and women during times of prosperity and times of recession. Public Health. 2000;114(1):25–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Béland F, Birch S, Stoddart G. Unemployment and health: contextual-level influences on the production of health in populations. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(11):2033–2052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navarro V, Shi L. The political context of social inequalities and health. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(3):481–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung H, Muntaner C. Welfare state matters: a typological multilevel analysis of wealthy countries. Health Policy. 2007;80(2):328–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bambra C. Going beyond the three worlds of welfare capitalism: regime theory and public health research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(12):1098–1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esping-Andersen G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Oxford, England: Polity Press; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bambra C, Eikemo TA. Welfare state regimes, unemployment and health: a comparative study of the relationship between unemployment and self-reported health in 23 European countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(2):92–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper D, McCausland WD, Theodossiou I. The health hazards of unemployment and poor education: the socioeconomic determinants of health duration in the European Union. Econ Hum Biol. 2006;4(3):273–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper D, McCausland WD, Theodossiou I. Unemployed, uneducated and sick: the effects of socio-economic status on health duration in the European Union. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2008;171(4):939–952 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodriguez E. Keeping the unemployed healthy: the effects of mean-tested and entitlement benefits in Britain, Germany, and the United States. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(9):1403–1411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall PA, Soskice D. An introduction to varieties of capitalism. : Hall PA, Soskice D, Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2001:1–68 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Estevez-Abe M, Iversen I, Soskice D. Social protection and the formation of skills: a reinterpretation of the welfare state. : Hall PA, Soskice D, Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundation of Comparative Advantage. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2001:145–183 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szydlik M. Vocational education and labour markets in deregulated, flexibly coordinated and planned societies. Eur Soc. 2002;4(1):79–105 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill MS. The Panel Study of Income Dynamics: A User’s Guide. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haisken-DeNew JP, Frick JR. DTC - Desktop Companion to the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (GSOEP). Version 8.0 ed. Berlin, Germany: The German Institute for Economic Research; 2005.

- 40.Brauns H, Scherer S, Steinmann S. The CASMIN educational classification in international comparative research. : Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik JHP, Wolf C, Advances in Cross-National Comparison. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003:221–243 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kerckhoff AC, Ezell ED, Brown JS. Toward an improved measure of educational attainment in social stratification research. Soc Sci Res. 2002;31(1):99–123 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata. 2nd ed. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singer JD, Willett JB. Its about time—using discrete-time survival analysis to study duration and the timing of events. J Educ Stat. 1993;18(2):155–195 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frijters P, Haisken-DeNew J, Shields MA. Socio-Economic Status, Health Shocks, Life Satisfaction and Mortality: Evidence From an Increasing Mixed Proportional Hazard Model. Discussion paper no. 1488 Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sorlie PD, Rogot E. Mortality by employment status in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):983–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bureau of Labor Statistics Unemployed persons by marital status, race, Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, age and sex. Available at: ftp://ftp.bls.gov/pub/special.requests/lf/aa2005/pdf/cpsaat24.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2010

- 48.Rothman K, Greenland S, Lash T. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robinson JC. Job hazards and job security. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1986;11(1):1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hertzman C. Health and human society. Am Sci. 2001;89(6):538–545 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siddiqi A, Hertzman C. Towards an epidemiological understanding of the effects of long-term institutional changes on population health: a case study of Canada versus the USA. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(3):589–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kunitz SJ, Pesis-Katz I. Mortality of White Americans, African Americans, and Canadians: the causes and consequences for health of welfare state institutions and policies. Milbank Q. 2005;83(1):5–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]