Abstract

Diabetes (diagnosed or undiagnosed) affects 10.9 million US adults aged 65 years and older. Almost 8 in 10 have some form of dysglycemia, according to tests for fasting glucose or hemoglobin A1c. Among this age group, diagnosed diabetes is projected to reach 26.7 million by 2050, or 55% of all diabetes cases. In 2007, older adults accounted for $64.8 billion (56%) of direct diabetes medical costs, $41.1 billion for institutional care alone. Complications, comorbid conditions, and geriatric syndromes affect diabetes care, and medical guidelines for treating older adults with diabetes are limited. Broad public health programs help, but effective, targeted interventions and expanded surveillance and research and better policies are needed to address the rapidly growing diabetes burden among older adults.

Diabetes mellitus is “a group of diseases marked by high levels of blood glucose resulting from defects in insulin production, insulin action, or both.”1(p11) Diabetes has 2 primary forms: type 1, previously called insulin-dependent or juvenile-onset diabetes, and type 2, previously called non–insulin-dependent or adult-onset diabetes; the latter accounts for about 90% to 95% of all diagnosed cases of diabetes. In 2005 to 2008, 25.8 million Americans, or 8.3% of the US population, had diabetes, and an additional 79 million had prediabetes, according to fasting glucose or hemoglobin A1c tests.1 As the average age of the US population rises, the prevalence of diabetes among adults is projected to increase to 14% to 33% by 2050.2

Because the anatomical and physiological changes characteristic of the normal aging process are accelerated in people with diabetes,3,4 life expectancy is shorter. For example, among people aged 55 to 64 years, diabetes reduces life expectancy by 8 years.5,6 A 57-year-old person with diabetes may have a biological age equivalent to that of a person aged 65 years without diabetes. Along with the importance of chronological and biological age, certain ages have social (typical retirement age), political,7 or programmatic significance,8 which should be considered in planning strategies for addressing diabetes among older adults. Older adults with diabetes present special epidemiological and public health challenges, and public health actions to prevent and control diabetes in this growing subpopulation should address these.

A GROWING PROBLEM

According to estimates for 2010, 10.9 million Americans aged 65 years or older had diabetes.1 The prevalence of prediabetes among Americans of this age, derived from results of fasting glucose or hemoglobin A1c testing in 2005 to 2008 and applied to 2010 data, was estimated to be 50%, indicating an extremely large reservoir of older adults at high risk for type 2 diabetes.1 Together, these results indicate that almost 8 in 10 older adults in the United States have some form of dysglycemia.

National survey data showed that the incidence of diagnosed diabetes among Americans aged 65 to 79 years increased by 65% from 1997 to 2003.9 For 2010, 390 000 new cases were estimated to have occurred among Americans aged 65 years and older.1 At the same time, from 1980 to 2004, the estimated number of Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes increased from 2.3 million to 5.8 million, and diabetes accounted for 32% of all Medicare spending during that period.10 The incidence of diabetes among Medicare beneficiaries aged 67 years or older also increased by 36.9% between 1997 and 2003.10

The number of Americans aged 65 years or older who are diagnosed with diabetes is projected to increase from 6.3 million in 2005 to 26.7 million by 2050 (a 3.2-fold increase), and the percentage of diabetic persons aged 65 years or older is projected to increase from 39% to 55% (Figure 1).6 In 2004, 25% of US nursing home residents had diabetes,11,12 and in 2007, 86% of all US deaths associated with diabetes were among people aged 60 years or older.13

FIGURE 1—

Projected number of cases of diagnosed diabetes among total population and older adults aged 65 years and older: United States, 2005–2050.

Source. Narayan et al.6

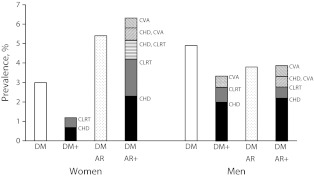

Most older adults with diabetes also have other major chronic diseases. A study of chronic disease prevalence among Americans aged 65 years or older during 1999 to 2004 found substantial comorbidities: prevalence of diabetes alone was 3.0% among women and 4.9% among men; diabetes with arthritis, 5.4% among women and 3.8% among men; diabetes with any combination of coronary heart disease, chronic lower respiratory tract disease, or cerebrovascular accident, 1.2% among women and 3.3% among men; and diabetes with arthritis and cardiorespiratory disease, 6.3% among women and 3.9% among men (Figure 2). Collectively, these comorbidities of diabetes and other serious diseases affected 11.7% of women and 7.7% of men (or roughly 2 288 480 women and 1 211 590 men).14

FIGURE 2—

Prevalence of major chronic diseases in adults aged 65 years and older: United States, 1999–2004.

Note. AR = arthritis; CHD = coronary heart disease; CLRT = chronic lower respiratory tract disease; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; DM = diabetes mellitus.

Source. Weiss et al.14

Diabetes and its complications also impose profound economic costs.15 In 2007, the total cost of diabetes in the United States was estimated to be $174 billion, $116 billion in direct medical costs and $58 billion in indirect costs (e.g., disability, work loss, premature death).1 For 2007, average medical expenditures among Americans with diagnosed diabetes were estimated to be 2.3 times as high as expenditures among those without diabetes, and annual diabetes-related expenditures were even higher among older diabetic patients because of their more frequent use of medications, medical services, and home care. In all, Americans with diabetes aged 65 years or older accounted for $64.8 billion (56%) of all US health care expenditures ($9713 per person).13

In a study of Americans born between 1931 and 1941, researchers estimated that sick days, disability, early retirement, and premature death cost the United States almost $133.5 billion during 1992 through 2000 and that persons with diabetes lost, on average, $2800 because of early retirement, $630 because of sick days, and $22 100 because of disability.16 For this American cohort and period, total diabetes-related losses were estimated to be $58.6 billion; coupled with an estimated $60 billion in productivity losses prior to 1992, the total estimated cost of diabetes was nearly $120 billion. An analysis of 1993 data from a nationally representative survey of all adults aged 70 years or older calculated time spent in informal care (h/wk) from medication use of diabetic patients and found that patients taking no medication required 10.1 hours of informal care; for oral medication, 10.5 hours; and for insulin, 14.4 hours; in each case substantially higher than for persons without diabetes (6.1 h/wk).17 The researchers estimated the associated annual cost of informal care provided to older-adult diabetic patients to be between $3 billion and $6 billion (in 1998 dollars). More data on diabetes caregiving is available elsewhere.18,19

PUBLIC HEALTH BURDEN

The public health significance of the rising prevalence of diabetes among older Americans goes beyond sheer numbers. The amplified complexity and challenges of aging-related health concerns produce a highly heterogeneous mix of varied duration of disease, coexisting illness and disability, exposure to many types of medication, and limited financial and social means to deal with infirmity.20,21

Traditional Diabetes Risks and Outcomes

Cardiovascular disease.

Because diabetes hastens the atherosclerotic process and increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD),21 this condition is highly prevalent among older adults with long-standing diabetes. Estimates based on self-reported survey data indicated that in 2010, 40.1% of US diabetic patients aged 65 to 74 years had CVD, 26.8% had coronary heart disease, and 9.1% had suffered a stroke; estimates for diabetic patients aged 75 years or older were 55.2%, 35.4%, and 18.0%, respectively (Table 1).22 Recent cohort studies found that incidence of CVD was significantly higher among older Americans with newly diagnosed diabetes than among their nondiabetic peers.23–26 A 1995 to 2004 study of Medicare beneficiaries that controlled for age, gender, and race/ethnicity found that the incidence of congestive heart failure was 65% higher and the incidence of stroke was 62% higher among those with diabetes than among those without.24,25 Although the excess CVD risk attributable to diabetes was lower for older than for younger cohorts, the findings indicate that the excess effect of diabetes on CVD persists well into old age.

TABLE 1—

Current Diabetes-Related Indicators Among Older Adults with Diabetes: United States, National Diabetes Surveillance System and National Vital Statistics System, 2003-2010

| Indicator Category | Age Groups | Data Source | Year | ||

| 45–64 Years | 65–74 Years | ≥ 75 Years | |||

| Incidence of diagnosed diabetes | |||||

| Men,a per 1000 US adults (SE) | 15.6 (1.9) | 13.1 (2.2) | … | NHIS | 2010 |

| Women,a per 1000 US adults (SE) | 11.5 (1.6) | 11.9 (1.9) | … | NHIS | 2010 |

| Prevalence of diagnosed diabetes | |||||

| Men, % (SE) | 13.1 (0.48) | 23.2 (1.01) | 23.8 (1.18) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Women, % (SE) | 11.5 (0.43) | 18.6 (0.83) | 17.7 (0.83) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Non-Hispanic Whites, % (SE) | 11.4 (0.37) | 19.1 (0.77) | 19.0 (0.74) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Non-Hispanic Blacks, % (SE) | 18.3 (0.96) | 32.4 (1.67) | 30.5 (2.04) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Hispanics, % (SE) | 17.9 (0.91) | 30.5 (2.16) | 35.7 (3.03) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Non-Hispanic White men, % (SE) | 12.5 (0.54) | 21.6 (1.12) | 22.8 (1.31) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Non-Hispanic White women, % (SE) | 10.4 (0.45) | 16.9 (0.94) | 16.3 (0.89) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Non-Hispanic Black men, % (SE) | 17.5 (1.32) | 34.1 (3.01) | 33.8 (4.04) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Non-Hispanic Black women, % (SE) | 18.9 (1.41) | 31.1 (2.23) | 28.9 (2.58) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Hispanic men, % (SE) | 16.7 (1.36) | 29.1 (3.33) | 41.1 (4.76) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Hispanic women, % (SE) | 19.0 (1.34) | 31.6 (2.69) | 31.4 (3.32) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Use of any diabetes medications | |||||

| % of persons with diabetes (SE)b | 85.5 (0.9) | 88.9 (1.1) | 86.4 (1.3) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Hospital discharge diagnoses (diabetes and renal) | |||||

| Diabetes, first listed, per 1000 (SE) | NHDS | 2009 | |||

| Men | 24.4 (3.1) | 21.9 (3.8) | 33.0 (6.6) | ||

| Women | 27.5 (4.0) | 30.1 (5.1) | 48.0 (10.5) | ||

| Whites | 18.0 (2.7) | 17.7 (3.1) | 32.0 (6.5) | ||

| Blacks | 34.2 (6.0) | 26.6 (7.0) | 45.8 (12.6) | ||

| Diabetes, any listed, per 1000 (SE) | NHDS | 2009 | |||

| Men | 194.3 (23.0) | 299.2 (41.5) | 415.3 (60.9) | ||

| Women | 211.8 (26.0) | 320.2 (42.9) | 539.2 (72.6) | ||

| Whites | 145.9 (19.9) | 253.4 (38.5) | 396.7 (59.8) | ||

| Blacks | 232.6 (39.1) | 277.4 (51.6) | 470.4 (92.9) | ||

| Diabetic ketoacidosis,c per 1000 | NHDS | 2009 | |||

| Men | 2.2 (0.3) | … | … | ||

| Women | 2.8 (0.4) | … | … | ||

| Hyperglycemic-crisis death, per 100 000 (SE) | NVSS | 2009 | |||

| Men | 13.1 (0.5) | 6.9 (0.4) | 11.4 (0.8) | ||

| Women | 9.1 (0.4) | 6.2 (0.3) | 17.5 (1.0) | ||

| Whites | 10.2 (0.4) | 6.7 (0.3) | 14.5 (0.7) | ||

| Blacks | 17.2 (1.2) | 6.6 (0.6) | 18.4 (1.8) | ||

| Initiate ESRD treatment, per 100 000 (SE) | USRDS | 2008 | |||

| Men | 265.1 (9.4) | 346.1 (15.2) | 372.1 (19.6) | ||

| Women | 212.4 (8.0) | 295.1 (12.7) | 274.6 (13.0) | ||

| Whites | 192.7 (5.9) | 272.9 (10.2) | 284.5 (12.1) | ||

| Blacks | 430.4 (23.2) | 562.2 (37.5) | 494.1 (40.2) | ||

| Hispanics | 323.7 (18.8) | 444.1 (38.2) | 447.9 (51.5) | ||

| White men | 215.3 (8.5) | 306.3 (15.3) | 339.3 (19.5) | ||

| White women | 168.4 (7.4) | 240.3 (12.1) | 236.5 (12.9) | ||

| Black men | 517.1 (43.2) | 586.6 (62.5) | 627.0 (101.5) | ||

| Black women | 363.0 (23.7) | 544.3 (44.4) | 436.3 (37.6) | ||

| Hispanic men | 369.4 (29.5) | 604.4 (82.9) | 401.6 (67.2) | ||

| Hispanic women | 276.2 (20.8) | 341.4 (36.6) | 498.6 (59.4) | ||

| Hospital discharge diagnoses for CVD | |||||

| Major CVD, per 1000 (SE) | NHDS | 2006 | |||

| Men | 68.8 (5.8) | 114.3 (12.8) | 153.0 (18.3) | ||

| Women | 57.7 (4.9) | 101.9 (10.0) | 164.6 (17.1) | ||

| Ischemic heart disease, per 1000 (SE) | NHDS | 2006 | |||

| Men | 31.5 (2.9) | 45.1 (6.5) | 41.6 (5.5) | ||

| Women | 21.4 (2.5) | 29.2 (3.9) | 34.5 (4.0) | ||

| Congestive heart failure, per 1000 (SE) | NHDS | 2006 | |||

| Men | … | 23.1 (3.7) | 42.9 (6.2) | ||

| Women | … | 25.3 (3.0) | 55.7 (7.5) | ||

| Stroke, per 1000 (SE) | NHDS | 2006 | |||

| Men | … | 16.1 (2.4) | 22.4 (3.8) | ||

| Women | … | 15.4 (1.9) | 25.6 (3.6) | ||

| Self-report of CVD | |||||

| CHD or stroke (any), % (SE) | … | 40.1 (1.7) | 55.2 (1.9) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Coronary heart disease, % (SE) | … | 26.8 (1.7) | 35.4 (1.9) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Stroke, % (SE) | … | 9.1 (0.9) | 18.0 (1.5) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Hospital discharge diagnoses (other complications) | |||||

| Lower extremity condition (any), per 1000 (SE) | 13.9 (0.8) | 15.6 (1.2) | 21.6 (1.9) | NHDS | 2007 |

| Peripheral arterial disease, per 1000 (SE) | 3.7 (0.3) | 6.9 (0.6) | 8.5 (0.9) | NHDS | 2007 |

| Ulcer/inflammation/infection, per 1000 (SE) | 6.3 (0.5) | 6.2 (0.7) | 8.7 (1.0) | NHDS | 2007 |

| Neuropathy, per 1000 (SE) | 3.9 (0.3) | 2.6 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.9) | NHDS | 2007 |

| Nontraumatic LEA, per 1000 (SE) | 2009 | ||||

| Nontraumatic LEA (any) | … | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.7 (1.0) | NIS-HCUP | |

| Toe | … | 2.1 (0.14) | 2.3 (0.16) | NIS-HCUP | |

| Foot | … | 0.6 (0.05) | 0.7 (0.06) | NIS-HCUP | |

| Below knee | … | 1.2 (0.09) | 1.4 (0.10) | NIS-HCUP | |

| Above knee | … | 0.8 (0.06) | 1.4 (0.10) | NIS-HCUP | |

| Limitations | |||||

| Visual, % (SE) | NHIS | 2010 | |||

| Men | 17.1 (1.4) | 16.5 (1.8) | 17.6 (2.2) | ||

| Women | 22.9 (1.5) | 19.0 (1.7) | 21.2 (2.0) | ||

| Mobility, any, % (SE) | 59.1 (1.4) | 68.6 (1.8) | 78.7 (1.7) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Stoop, bend, kneel, % (SE) | 52.2 (1.4) | 61.5 (1.7) | 68.9 (1.7) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Stand for 2 h, % (SE) | 45.1 (1.4) | 52.3 (1.8) | 65.5 (1.8) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Walk quarter mile, % (SE) | 42.4 (1.4) | 49.5 (1.9) | 63.1 (1.8) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Climb up 10 steps, % (SE) | 33.9 (1.3) | 39.9 (1.6) | 52.1 (2.0) | NHIS | 2010 |

| Physical or mental, % (SE) | 66.9 (0.6) | 57.3 (0.7) | 57.5 (0.8) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Physical only, % (SE) | 56.8 (0.6) | 49.9 (0.7) | 52.0 (0.8) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Mental only, % (SE) | 41.3 (0.6) | 26.2 (0.6) | 22.1 (0.6) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Physical and mental, % (SE) | 31.2 (0.6) | 18.8 (0.5) | 16.7 (0.6) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Unable to perform usual actions, % (SE) | 38.0 (0.6) | 28.7 (0.6) | 26.0 (0.7) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Fair or poor general health, % (SE) | 47.6 (0.6) | 45.0 ( 0.7) | 46.2 (0.7) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| ADL problemsd | NHIS | 2008 | |||

| Whites | … | 7.2 (1.03) | 14.6 (1.74) | ||

| Blacks | … | 9.1 (1.83) | 21.0 (3.82) | ||

| Instrumental ADL problemsd | NHIS | 2008 | |||

| Whites | … | 13.0 (1.25) | 24.0 (2.19) | ||

| Blacks | … | 21.6 (2.82) | 33.6 (4.15) | ||

| Preventive care received | |||||

| ≥ 1 doctor visit/y,e % (SE) | 89.2 (0.5) | 89.4 (0.5) | 86.2 (0.7) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| ≥ 2 A1c tests in past year,e % (SE) | 72.4 (0.7) | 78.2 (0.8) | 75.7 (0.9) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Daily self-monitoring,e % (SE) | 62.2 (0.7) | 65.2 (0.9) | 65.7 (0.9) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| DSM class,e % (SE) | 56.0 (0.8) | 55.0 (0.9) | 46.8 (1.0) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Pneumonia vaccine,f % (SE) | 47.0 (0.6) | 69.1 (0.7) | 79.5 (0.6) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Influenza vaccine,f % (SE) | 54.6 (0.6) | 67.7 (0.7) | 74.4 (0.7) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Daily feet self-examination,e % (SE) | 66.8 (0.7) | 66.7 (0.9) | 62.6 (1.0) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Annual feet examination,e % (SE) | 72.8 (0.7) | 74.9 (0.8) | 72.1 (0.9) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Annual dilated eye examination,e % (SE) | 65.7 (0.7) | 74.8 (0.8) | 80.3 (0.8) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Risk factors for complications | |||||

| Physical inactivity, % (SE) | 37.2 (0.6) | 38.0 (0.7) | 45.2 (0.7) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Smoking, % (SE) | 18.8 (0.5) | 10.4 (0.4) | 4.1 (0.3) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Overweight (with obese), % (SE) | 89.3 (0.4) | 85.5 (0.5) | 74.2 (0.7) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Obese, % (SE) | 59.9 (0.6) | 49.0 (0.7) | 33.1 (0.7) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| High blood cholesterol, % (SE) | 66.7 (0.6) | 66.4 (0.7) | 59.8 (0.8) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Hypertension, % (SE) | 69.0 (0.6) | 75.9 (0.7) | 73.5 (0.7) | BRFSS | 2010 |

| Hemoglobin A1c,g % (SE) | NHANES | 2003–2006 | |||

| < 7% | 49.9 (3.8) | 67.2 (3.3) | … | ||

| < 8% | 70.6 (2.9) | 89.8 (1.4) | … | ||

| > 9% | 16.6 (2.1) | 4.1 (1.1) | … | ||

| Blood pressure,g mm Hg, % (SE) | NHANES | 2003–2006 | |||

| < 130/80 | 50.0 (3.7) | 33.2 (3.0) | … | ||

| < 140/90 | 74.9 (2.8) | 55.8 (2.9) | … | ||

Note. A1c = hemoglobin A1c; ADL = activities of daily living; BRFSS = Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CHD = coronary heart disease; CVD = cardiovascular disease; DSM = diabetes self-management; ESRD = end-stage renal disease; LEA = lower-extremity amputation; NHDS = National Hospital Discharge Survey; NHIS = National Health Interview Survey; NIS-HCUP = Nationwide Inpatient Sample of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project; NVSS = National Vital Statistics System; USRDS = United States Renal Data System.

Oldest age range was 65–79 years.

When it was not possible to supply indicator data for age by sex, age by race, or age by sex by race, data for age only has been listed.

For diabetic ketoacidosis by sex, the age group is ≥ 45 years.

Middle age range was 60–74 years.

Data from 46 states/territories.

Data from 52 states/territories.

Oldest age range was ≥ 65 years.

Hospital discharge data from 2009 showed that circulatory diseases accounted for 501 000 first-listed diagnoses among US hospital patients with diabetes aged 45 to 64 years, 380 000 among those aged 65 to 74 years, and 493 000 among those aged 75 years or older, constituting 25% to 31.5% of all hospital discharges for these age groups.27 In 2006, rates of hospitalization among diabetic Americans for whom major CVD was the first-listed diagnosis were 68.8 per 1000 patients for men aged 45 to 64 years, 114.3 for those aged 65 to 74 years, and 153.0 for those aged 75 years or older, and 57.7, 101.9, and 164.6, respectively, for women (Table 1).

Chronic kidney disease.

Major microvascular complications of diabetes affecting the kidneys and eyes impose a considerable burden on individuals and society.28–31 Older adults with diabetes are at increased risk for chronic kidney disease (CKD).32–34 During 1999 to 2006, the estimated prevalence of CKD among Americans aged 60 years or older was significantly higher among those with diabetes (58%) than among those without (41%).35,36 It is encouraging, however, that recent trials found that diabetic patients who received treatment for glucose and high blood pressure enjoyed a significant reduction in negative renal outcomes.37,38

Early stages of CKD can lead to frailty, disability, decreased physical and cognitive function, and end-stage renal disease (ESRD, or kidney failure).39–41 Risk factors for ESRD, which is treatable only by dialysis or transplantation, are protein in urine, high blood pressure, diabetes, and race/ethnicity.38 Of all new cases of ESRD in 2006, 45% were estimated to have been caused by diabetes.3,41–43 The estimated incidence of ESRD treatment initiation among all Americans with diagnosed diabetes increased by an average of 5.8% per year from 1990 through 1996 but decreased by an average of 2.9% per year from 1996 through 2006; among those aged 65 to 74 years, incidence rates rose about 6% per year through 1998 and declined by 3.4% per year through 2006; and among those aged 75 or older, rates rose more than 10% per year through 1999 and declined by 2.1% per year thereafter.44 Overall, age-adjusted incidence rates over the entire study period were lower among women than men and were highest among Blacks and lowest among Whites. The average annual decrease in ESRD treatment initiation rates after 1996 was higher among women (4.3%) than men and higher among Whites (5.0%) than other racial/ethnic groups.44 Estimates for gender and racial/ethnic differences among older diabetic patients are shown in Table 1 and detailed in Goldfarb-Rumyantzev and Rout.45

Diabetic retinopathy.

During 2005 to 2008, the estimated prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among diabetic Americans aged 65 years or older was 29.5%, and the estimated prevalence of vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy was 5.1%.28 Neither estimate differed significantly from those for diabetic Americans aged 40 to 64 years. Age-standardized prevalence estimates for diabetic retinopathy and for vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy have increased since 1998, and prevalence rates are projected to triple among Americans aged 40 years or older and to quadruple among those aged 65 years or older between 2005 and 2050.46 Diabetes also increases older adults’ risk of cataracts, which affects 15 million Americans aged 65 years or older,47 and it may increase the risk of primary open-angle glaucoma among women.48

Neuropathies.

Peripheral neuropathies are a large group of disabling sensory and motor nerve abnormalities that are common among older adults and persons with diabetes.49,50 Peripheral sensory neuropathy is a type of peripheral neuropathy that is widely recognized as a complication of diabetes. In older persons with diabetes, peripheral sensory neuropathy is associated with impairments in balance, gait, performance of activities of daily living, increased incidence of recurrent falls and fractures,49,51 and the presence of lower-extremity peripheral arterial disease. Peripheral sensory neuropathy contributes to lower-extremity ulceration, deformity, and nontraumatic amputations.1,49 In 2009, the rate of lower-extremity amputations in diabetic patients aged 65 to 74 years was 3.5 per 1000 and for those aged 75 years and older, 3.7 (Table 1 shows the disease's anatomical sites).52 In a representative sample of US adults aged 40 years and older in 1999 to 2000, peripheral sensory neuropathy was almost twice as prevalent among persons with diabetes (28.5%) as among those without (13.3%), and was 2- to 4-fold higher for persons aged 60 years and older (17.5%–34.7%) as for those aged 40 to 49 years (8.1%).50

In older adults with diabetes, autonomic neuropathy, another type of peripheral neuropathy, may affect many organ systems, including the cardiovascular system, upper and lower gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, and skin.53 The most commonly reported manifestation is cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy; however, its epidemiology has not been fully investigated. Prevalence estimates range from 7% to as high as 90%, derived from a variety of diagnostic criteria, populations, and settings.53

Sensory impairment.

Some evidence associates diabetes with hearing loss, although the mechanisms underlying such an association are unclear.54–57 People with diabetes have been found to have a lower age-, gender-, and race-standardized prevalence of normal hearing than those without diabetes.58 Although the overall prevalence of hearing impairment in the United States declined from 1971 through 2004, it did not decline among people with diabetes. Although age is a strong predictor of hearing impairment,58 scant evidence has been found that diabetes increases the risk of hearing impairment among older people. Dual sensory impairment (hearing impairment coupled with visual impairment) is particularly prevalent among older adults and may lead to physical limitations.59

Less Traditional Risks and Outcomes

Geriatric syndromes.

Evidence suggests that diabetes is independently associated with increased risk of multisystem geriatric syndromes.60–62 Geriatric syndromes, whose manifestations include falls and fear of falling, urinary or fecal incontinence, functional decline, and delirium, are common among older adults, share multiple risk factors, and often contribute to substantial disability and a lower health-related quality of life (HRQOL).61,62 Disability risk has been estimated to be 100% to 200% greater among people with diabetes than without,63–66 in part because of the many co-occurring health problems among people with diabetes, including cardiorespiratory problems, arthritis, and poor muscle strength and quality.67,68 Diabetes is also associated with an increased risk of falls among older adults.69–72 A prospective study showed that women with diabetes had a significantly greater risk of falling more than once in a year than did women without diabetes, indicated by age-adjusted odds ratios of 1.68 for women who were not using insulin and 2.78 for those who were.51

Geriatric syndromes appear to be more common among older women than older men, illuminating the specific burden women with diabetes bear.60 They also call into question the traditional approach of targeting treatment to each system separately,73 because needs among older adults with diabetes may be heterogeneous. No hard evidence shows that currently recommended diabetes care is efficacious or cost-effective for these syndromic outcomes; more research, leading to evidence-based approaches to prevent or delay such outcomes, is needed. Much is still unknown about the natural history of the development and progression of diabetes in persons with geriatric syndromes.

Infectious diseases.

Aging and increased levels of glycated hemoglobin and advanced glycation end products are associated with decreased immunological function and may account for enhanced susceptibility to infections among older adults, some of which lead to death.74 For example, regardless of study design, population, or geographic region, diabetes has been associated with increased incidence of pulmonary tuberculosis75 and higher significant multivariate-adjusted relative risks of tuberculosis, ranging from 1.23 to 2.69 across racial/ethnic groups among US adults.76

Transmission of blood-borne pathogens is linked to blood glucose monitoring, a recommended part of diabetic self-care.77 Older adults with diabetes in nursing homes and assisted-living facilities have a pronounced risk of person-to-person transmission of hepatitis B and C viruses.78 From 1998 to 2008 in the United States, 33 outbreaks of hepatitis B and C occurred among 448 adults (5 deaths); 15 (45.5%) occurred in long-term care facilities and were attributed to sharing of finger-stick and blood glucose–monitoring devices.79

Older adults also experience high levels of morbidity and mortality from several other vaccine-preventable diseases.80 Adults aged 65 years and older account for almost 90% of influenza-related deaths: 56 per 10 000 influenza-related hospitalizations for patients with comorbidities and 19 for patients without.81 In response, by 2010 the percentage of US diabetic patients who received an influenza vaccine in the previous year had risen to 54.6% for persons aged 45 to 64 years, 67.7% for persons aged 65 to 74 years, and 74.4% for those aged 75 years or older (Table 1).82 In addition, older adults account for 20% of deaths related to invasive pneumococcal disease and nearly half (47%) of all cases of tetanus.80 Among unvaccinated enrollees in a large managed care organization aged 60 years and older, the incidence of herpes zoster was 13 per 1000.83 Although people with diabetes are considered a high-risk group for vaccine-preventable diseases, we did not find specific epidemiological evidence that diabetes increases the risk of any vaccine-preventable diseases.

Periodontal disease.

Periodontal disease (also called gingivitis or periodontitis) is a chronic inflammatory disease that is a common cause of tooth loss among older adults in the United States.84–87 Diabetes is a significant risk factor for periodontal disease.88–90 Results of a national survey showed that 15.1% of Americans aged 45 years or older with poorly controlled diabetes had severe periodontitis; only 6.0% of those whose diabetes was under better control and 4.3% of those without diabetes reported this condition. Results also showed that 20% of Americans aged 65 years or older needed a referral for periodontal disease treatment; 2.0% required an urgent referral.91,92 The causal relationship between periodontal disease and diabetes was found to be bidirectional, with periodontal disease associated with impaired glycemic control and a risk of diabetes complications, notably cardiovascular problems, nephropathy, and ESRD.93 No age-specific estimates were reported for participants with diabetes.

Urinary incontinence.

Estimates of the prevalence of urinary incontinence among US women aged 60 years or older range from 17% to 49%, and estimates of the direct medical costs of the condition range from $19.5 to $26 billion annually.94,95 Population-based studies have shown that women with diabetes are at significantly higher risk for urinary incontinence than are those without diabetes.94–97 These studies also showed increased risk with duration of diagnosed diabetes and indicators of severity of diabetes assessed via insulin use and evidence of existing microvascular disease.

Cognitive impairment.

Diabetes is a significant risk factor for cognitive impairment and the acceleration of cognitive decline.60,98,99 The extent of cognitive decline among people with diabetes has been positively associated with the duration of their diabetes. Meta-analyses of studies among people with mean ages of about 70 to 80 years found that those with diabetes had a relative risk of 1.47 for dementia, 1.39 for Alzheimer's disease, and 2.38 for vascular dementia, with nondiabetic persons as the reference group.60

Depression.

Health outcomes among diabetic patients tend to be worse among those who are depressed. For example, a study of US patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes found that participants who were depressed had more physician office visits, emergency room visits and inpatient admissions, and prescriptions filled than did those who were not depressed, along with 65% higher overall health care costs.100 Depression among older women with diabetes is linked to poor HRQOL and to negative effects on diabetes and other self-care regimens.101

Polypharmacy.

Older adults frequently take multiple prescription and nonprescription medications to reduce or prevent the complications associated with multiple medical conditions.102,103 Paradoxically, however, such polypharmacy may also increase their risk of adverse events such as the onset or worsening of geriatric syndromes, drug interactions, and even death.72,102,104 One review found that 50% to 60% of noninstitutionalized adults aged 65 years and older use 5 or more prescription medications and 2 to 4 nonprescription medications daily.102 A study of US nursing home residents found that 45% of those aged 65 to 84 years and 34.9% of those aged 85 years or older used at least 9 medications.103 A 1994 to 1997 US study found that adult managed care enrollees with type 2 diabetes were prescribed an average of 4.2 medications.72 We found no national data on the use of multiple medications among older Americans by diabetes status.

Health-related quality of life.

Diabetes has been consistently associated with a reduced HRQOL105–111 Factors contributing to this association include diabetes-specific complications, greater risk of other chronic conditions, and the effects of polypharmacy. A systematic review of persons with diabetes undergoing interventions to treat complications and comorbidities revealed significant improvement of HRQOL.112 Unfortunately, this review did not specifically note the effectiveness of such interventions for older adults with diabetes.

Social circumstances.

Despite improvement in the social circumstances of older adults since the 1960s, many remain socioeconomically disadvantaged.113 The Federal Interagency Forum estimated that in 2007, 9.7% of Americans aged 65 years or older had annual incomes below the federal poverty level, including 8.8% of those aged 65 to 74 years and 13.0% among those aged 85 years or older.113 Among all Americans aged 65 years or older, women were about twice as likely as men to have annual incomes below the federal poverty level (12.0% vs 6.6%). The Interagency Forum also estimated that in the United States, 18.5% of men and 39.5% of women aged 65 years or older lived alone in 2008; almost 1 in 5 men and half of women aged 75 years and older lived alone. In both genders and all racial/ethnic groups, older Americans’ likelihood of having an annual income below the federal poverty level was greater among those who lived alone.

Although national data on the social circumstances of older adults with diabetes are sparse,114 several epidemiological studies have shown that among Americans in late middle age, those with diabetes were significantly more likely than their nondiabetic peers to be poorly educated and to live in low-income households.115,116 These results suggest that the capacity of many older Americans to deal with diabetes and its consequences may be compromised by their social circumstances and that the likelihood of living in adverse circumstances is especially high among women, members of some minority racial/ethnic groups, and those who live alone. Smedley calls for comprehensive strategies that address inequality in many sectors, such as housing, education, and employment, as well as inequalities in health care.117

PUBLIC HEALTH INTERVENTIONS

Studies of adults (not specifically older adults) have demonstrated that tight control of blood glucose in patients with type 1 diabetes and control of both blood glucose and blood pressure in those with type 2 diabetes significantly reduced the risk of microvascular complications.118–120 In general, a percentage point drop in the hemoglobin A1c concentration of a person with diabetes is associated with a 40% reduction in the risk of microvascular complications. Research has also shown the value of controlling lipids in adults with or at risk for diabetes.121 Partly as a result of these findings, diabetic patients are advised to “know their ABCS” (i.e., their A1c level, blood pressure, cholesterol level, and the importance of smoking cessation).122–125

Guidelines

The Task Force on Community Preventive Services126,127 and the US Preventive Services Task Force128 have recommended evidence-based strategies for diabetes detection and management. In a systematic review of selected community-based interventions, the task force found strong evidence for the usefulness of case- and disease-management programs; for adults with type 2 diabetes, the review found sufficient evidence for the usefulness of diabetes self-management education in community gathering places, but insufficient evidence for the usefulness of in-home diabetes education.129,130

Recent evidence indicates that screening for diabetes is not cost-effective among people aged 45 years or older.131,132 The Preventive Services Task Force, however, recommends screening for type 2 diabetes among asymptomatic adults with sustained high blood pressure (> 135/80 mm Hg).133 In 2005 to 2006, the estimated prevalence of undetected diabetes among Americans aged 65 years or older was 13.0%, and undetected cases accounted for more than 40% of all diabetes cases among older Americans.134 Like uncontrolled diabetes, undetected diabetes among older adults is associated with an increased prevalence of CVD risk factors and an increased risk of cognitive impairment.135–137

In 2003, the American Geriatrics Society established diabetes treatment guidelines for older adults.73 These guidelines, based primarily on expert opinion, promote individualized patient care and education, prevention and control of cardiovascular risk factors, and screening to identify and treat patients with manifestations of geriatric syndromes. They recommend regulating glycemia to prevent and control microvascular complications, but also consideration of a higher glycemic target, as needed, according to diabetes severity, life expectancy, functional status, and patient preference.138

The American Diabetes Association now has guidelines to address the needs of older adults, which recognize that when interventions cannot reach a lower glycemic target, a higher value for older adults might be acceptable and even might be further increased over time when the medical status and capacity of the patient decline with increasing age. These guidelines also encourage lifestyle modification, with the selection of anithyperglycemic medication that focuses on drug safety, and acknowledge that any increase in physical activity is advantageous in older patients or those with mobility limitations, if tolerated by an individual's cardiovascular system.77 A recent systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions congruent with the association's guidelines showed that for older adults, interventions for hypertension were cost saving and for smoking cessation were cost-effective.131

Initiatives

In 1997, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health, and more than 200 partnering organizations launched the National Diabetes Education Program139 to develop and disseminate diabetes education materials for a variety of audiences. These materials are not copyrighted, and some are aimed at older adults. More recent diabetes-related collaborative efforts include the Chronic Kidney Disease Initiative,140 the Vision Health Initiative,141 the National Public Health Initiative on Diabetes and Women's Health,142 and state and territorial diabetes prevention and control programs.143

The Chronic Kidney Disease Initiative is piloting a national surveillance system and developing a program to prevent and control CKD risk factors (especially hypertension), raise public awareness about CKD, promote early CKD diagnosis, and improve HRQOL and other health outcomes among people with CKD. The Vision Health Initiative works to promote vision health, which is closely related to mental and physical health, in all populations. Because diabetes is the leading cause of new cases of blindness among people aged 20 to 74 years, CDC chose to house the vision project in its Division of Diabetes Translation. The mission of the National Public Health Initiative on Diabetes and Women's Health is to prevent or delay diabetes, promote family and community support, promote appropriate diabetes care across the life stages, and prevent, delay, or minimize diabetes complications.142

CDC funds 59 state and territorial diabetes prevention and control programs that promote the chronic care model and use a health systems approach144 to address the needs of all adults with diabetes.145 These programs work with local diabetes coalitions whose membership often includes organizations concerned with aging. Recently these programs and coalitions have been able to secure funding to use policy as a broad-based intervention.146 CDC has developed tools to facilitate prevention and control efforts. For example, a seasonal campaign encourages older adults to receive annual influenza vaccinations,147,148 although vaccine efficacy varies widely by age.149,150 Another tool, the Physical Activity Reference Guide for Older Adults,151 helps groups choose and implement physical activity programs for older diabetic adults that are appropriate for their functional status.

Older adults, 80% of whom have 1 or more chronic conditions or cognitive or physical limitations, are especially vulnerable during emergencies,152 which often involve physical displacement and shortages of food, water, and medical supplies (e.g., glucose monitors and insulin) that diabetic patients need.153 Governmental and nongovernmental organizations urge the public to be prepared and have produced numerous resources for use before, during, and after emergencies.154–158

National Diabetes Prevention Program

In 2002, the Diabetes Prevention Program completed a research trial aimed at primary prevention of diabetes.159,160 Participants either enrolled in an intensive lifestyle program with one-on-one counseling or took the drug Metformin.159,160 Among those aged 60 years or older, participation in the lifestyle program was associated with a 71% reduction in risk of diabetes; use of Metformin was associated with little if any reduction in diabetes risk (Figure 3).159,160 These results suggest that a lifestyle intervention is the only viable option for older adults who demonstrated a greater commitment to making healthful lifestyle changes than did younger participants, and that older adults drove the impressive findings found thus far in the Diabetes Prevention Program trial.161 Follow-up studies have shown that some degree of risk reduction can continue for 10 years or more.162,163 More recently, research has shown that intensive lifestyle programs, delivered in group settings, can be effective as well as cost-effective or cost saving164–170; results of one study suggested that lowering the Medicare eligibility age from 65 to 60 years could be of benefit.170

FIGURE 3—

Reductions in diabetes incidence, by intervention and age group, in 1043 men and 2191 women, with mean age 51 years, with IGT and IFG: Diabetes Prevention Program, 1997–2001.

Note. IFG = impaired fasting glucose; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance.

Source. Knowler et al.159

In response to a provision in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,171 which authorized CDC to establish a national prevention program for adults at high risk for diabetes, CDC's Division of Diabetes Translation launched the National Diabetes Prevention Program.172 This program encompasses 4 components:

Train a work force to deliver the structured lifestyle program cost-effectively.

Implement a recognition program to ensure quality, and establish a registry of program sites.

Prepare sites to deliver the lifestyle program.

Market the program.

As of April 2012, more than 90 organizations participate by administering lifestyle programs.173 These include inaugural partners such as the Y (also known as YMCA of the USA) and UnitedHealth Group.172

Governmental Policy

The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 expanded diabetic services covered by Medicare to include diabetes screening for beneficiaries at risk for the disease.174,175 For beneficiaries with diabetes who meet eligibility requirements, Medicare covers diabetes self-management training. In certain circumstances, Medicare also covers other diabetes services, as well as diabetes supplies and care.

Healthy People 2020 offers a strategic framework for health coordinated by the Department of Health and Human Services in conjunction with other federal agencies, public stakeholders, and the department's Secretary's Advisory Committee on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives.176 The chapter on diabetes proposes 16 diabetes-related objectives for adults in 6 areas: burden of disease; macrovascular, microvascular, and metabolic complications; laboratory services; health provider services; diabetes education; and patient protection behaviors.177 A chapter on older adults calls for increasing by 10% the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries who receive diabetes self-management benefits.178

The Diabetes Mellitus Interagency Coordinating Committee, led by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and incorporating representatives from many federal agencies, was established in 1974 to coordinate federal efforts to prevent and control diabetes. The committee has coordinated the Diabetes Prevention Program and other research efforts targeting older adults. At least 1 committee meeting was devoted to the treatment of older adults with diabetes.179 The committee recently called for a clinical trial of optimized diabetes care for older diabetic patients to assess the value of such care in reducing diabetic complications and manifestations of geriatric syndromes, in particular impairment, activity limitations, disability, and falls.180

OPTIONS FOR PUBLIC HEALTH ACTION

Efforts to elucidate and reduce the diabetes burden among older adults occur within a public health system that interfaces with medical care settings, state and local health departments, and a large array of partners with interests in or impacts on the diabetes and aging fields. Options for public health action can be categorized into 4 contexts: surveillance, programs, applied research, and policy.

Surveillance

Surveillance findings and projections based on those findings have helped define the burden of diabetes among older Americans and can help to evaluate progress in diabetes prevention and control.15,181 Summaries of surveillance data for 10 groups of diabetes-related indicators181 and for diabetes-related mortality182 are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively, with data current for 2003 to 2010 at the time of compilation. Although these data begin for adults aged 45 years and older, few diabetes-related indicators were stratified for Americans aged 85 years or older or for institutionalized older adults; only rates for mortality, diabetes prevalence, and initiation of ESRD treatment produced estimates by gender, race/ethnicity, and age.

TABLE 2—

Diabetes Mortality by Race/Ethnicity, Age, and Gender Among Older Adults: United States, 2006

| Racial/Ethnic Group | Age Group | ||||

| 45–54 Years, No./100 000 | 55–64 Years, No./100 000 | 65–74 Years, No./100 000 | 75–84 Years, No./100 000 | ≥ 85 Years, No./100 000 | |

| Non-Hispanic Whites | |||||

| Men | 14.2 | 179.6 | 37.6 | 83.9 | 179.6 |

| Women | 7.9 | 23.3 | 33.6 | 127.8 | 244.3 |

| Non-Hispanic Blacks | |||||

| Men | 34.3 | 92.6 | 191.3 | 334.2 | 468.2 |

| Women | 22.6 | 68.6 | 154.7 | 479.1 | 306.2 |

| Hispanics | |||||

| Men | 16.2 | 49.9 | 14.7 | 257.7 | 381.2 |

| Women | 10.1 | 35.8 | 103.7 | 208.7 | 363.7 |

Source. National Vital Statistics System.182

Table A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) shows that among 58 indicators for percentages and rates, demographic coverage extended to age groupings for persons 45 years and older for all of the indicators, with only about 21% for gender by age, 9% for race by age, and about 3% for race by gender by age. None were available by socioeconomic and social circumstances,113-116 for example, education, income, living alone, and so forth, which are important to characterize the current and future face of diabetes, especially among women.114,142

An expanded and more systematic surveillance structure is needed for all adults aged 45 years and older at national, state, and local levels to routinely describe the prevalence of diabetes and its complications, the prevalence of comorbidities among diabetic patients, and the relationship between diabetes and health outcomes or factors such as geriatric syndromes, HRQOL, injuries, health-related behaviors, and preventive care practices. Such surveillance data should be broken down by major sociodemographic categories, such as gender, race/ethnicity, age, income, and education. Surveillance data should also be collected on the range and adequacy of diabetes-related services, the extent to which various groups use these services, and the views of older adults regarding the adequacy and accessibility of existing services. The need for an integrated surveillance system to collect such data can be expected to increase with the projected increase in the number of older Americans with diabetes.

One method of generating a sufficient quantity of relevant data is to aggregate (even by statistical smoothing techniques) multiple years of data on National Diabetes Surveillance System indicators, as Canada has done, to achieve finer age groupings for diabetes prevalence across the entire age span.183 Another method is to establish a multisite regional surveillance system to monitor diabetes and diabetes-related conditions among older Americans, an approach already taken with youths.184 Information about the institutionalized US diabetic population, which is currently scarce, could be gathered through surveys of residential care facilities and nursing homes.185 In addition to collecting administrative information, such surveys should also collect data on biological measures for establishing the prevalence of prediabetes and diabetes, the rate of progression from prediabetes to diabetes, and the prevalence of various diabetes-related impairments and complications among the residents of these facilities.

Diabetes surveillance in the United States is Web based,181 which allows for frequent updating of indicators. As part of updating, it will be necessary to increase consistency in the use of standard age groupings for displaying data, to improve demographic coverage across combinations of age, gender, and racial/ethnic groups, and to introduce richer sociodemographic contrasts such as poverty, living in social isolation, and others (Table A, available as an online supplement). Laboratory hemogloblin A1c testing has been used to create registries of diabetic patients; reports are sent to both patients and physicians.186,187 This has potential as a way to reach older adults with diabetes. Although such efforts have increased the ordering of A1c tests,186 improvement of glycemic control in patients has not yet been shown.

Programs

Governmental agencies at all levels as well as various private organizations are engaged in the delivery of programs, services, and care for older Americans with diabetes. CDC's Division of Diabetes Translation works with state health departments and many partners to enhance these efforts. The 10 Essential Public Health Services provides a framework to formulate goals.188,189

Educate agencies and scientific and professional organizations about diabetes, aging issues, and the added impact of aging on older adults with diabetes, to ensure that those who direct and implement programs and deliver health care to older Americans with diabetes are competent, person oriented, and able to effect change at multiple levels.

Mobilize and expand existing diabetes-related partnerships140–142 to develop joint efforts that specifically address older adults.

Link older adults with diabetes to needed health services, and foster the provision of quality health care, when otherwise unavailable, by training health professionals and community health workers to offer such services.

Help reduce barriers to diabetes care and services for older adults with diabetes. This might involve teaching, health situation analyses, and ongoing assessments of diabetic adults to identify changes in physical, emotional, and social functioning.

Applied Public Health Research

Research conducted in real-world contexts is important to the advancement of public health.190 Such research can help fill gaps in knowledge, stimulate public health programs, and inform policy change and development. It can also identify risk factors for diseases and conditions as well as protective factors that may lead to longer life, better HRQOL, and reductions in functional limitations.

Research can clarify how social determinants of health, family support, governmental policies, sociodemographic characteristics, and other factors are associated with various health outcomes and identify effective multilevel health-promotion strategies.117,191,192 Applied research is especially important in exploring the public health implications of factors such as income insecurity and social isolation that are common among older people with diabetes.

Public Policy

Appropriate public policies can increase the availability and accessibility of services for older adults with diabetes. The following 5 public policy efforts can help improve health care services for older diabetic Americans:

Facilitate coordination of services to older diabetic patients to eliminate service redundancy and increase patients’ use of existing services. The coordination of services is particularly important for noninstitutionalized patients, especially women, who often live alone and in poverty.

Expand the delivery of in-home health care by using combinations of health professionals and lay people to provide services.

Expand diabetes education to include people serving as caregivers for older adults with diabetes, including training on how to interface with health professionals in providing care.

Ensure that standard medical care provided to older adults with diabetes includes formal systematic assessments of their physical, emotional, and social functioning so that any barriers to appropriate self-care can be identified and, if possible, overcome.

Promote analytic modeling of the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of interventions specifically designed to help older Americans with diabetes. An area to consider is assessing the interventions to address geriatric syndromes by estimating constructs such as disability-free life expectancy, an approach similar to the concepts of compression of morbidity and active aging.193,194

Public policies can also help increase the number of adequately trained health care providers, who are currently unable to meet the needs of the aging US population. Shortages of geriatricians, endocrinologists, and certified diabetes educators are particularly problematic for older adults with diabetes.195–197 An Institute of Medicine report recommends easing workforce shortages by training informal caregivers to assist in health care.198

CONCLUSIONS

The United States faces an urgent need to address diabetes among older Americans because indicators already reveal considerable mortality, morbidity, medical, and societal burdens, which are expected to continue growing. Because diabetes accelerates biological aging, many members of the baby boom generation can be expected to age prematurely: almost 8 in 10 older Americans already have diabetes or a less severe form of dysglycemia. Within only 40 years, clinicians who treat adult diabetes will likely see a preponderance of older patients. Complicating diabetes care in older adults are frequent comorbidities with microvascular and macrovascular disease and many debilitating manifestations of geriatric syndromes. Physicians have no clinical consensus on how best to treat older diabetic patients with these associated conditions.

Existing public health programs instituted to reach older diabetic patients may need to be modified to fully address their complex, specific needs and functional statuses, while remaining relevant to their interests and to the social and economic contexts in which they live. Possible modifications to these programs include greater use of lifestyle interventions, which have shown impressive early results. In addition, some creative revision of existing surveillance systems and applied public health research may lead to a better understanding of how diabetes affects HRQOL, its risks for other chronic conditions and geriatric syndromes, and the association of socioeconomic factors with diabetes and its related conditions.

If diabetes is to be prevented among older adults, or controlled to halt or slow the progression to otherwise inevitable complications, the public health community needs to develop, evaluate, and expand the reach of effective, targeted interventions that address the specific needs of older adults with or at risk for diabetes.

Acknowledgments

This article was prepared for the CDC series on aging and the roles of public health.

We acknowledge Pamela Allweiss for the invitation to write the paper and for participating in some early planning sessions and the very kind help and support of William I. Thomas, MLIS, in conducting literature searches and retrieving many important documents. We also acknowledge the past efforts and members of the Division of Diabetes Translation's Diabetes and Aging Workgroup.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was required because no human participants were involved.

References

- 1.National Diabetes Fact Sheet: National Estimates and General Information on Diabetes and Prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2011.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Gregg EW, Barker LE, Williamson DF. Projection of the year 2050 burden of diabetes in the US adult population: dynamic modeling of incidence, mortality, and prediabetes prevalence. Popul Health Metr. 2010;8:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ulrich P, Cerami A. Protein glycation, diabetes, and aging. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2001;56(1):1–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aronson D. Cross-linking of glycated collagen in the pathogenesis of arterial and myocardial stiffening of aging and diabetes. J Hypertens. 2003;21(1):3–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gu K, Cowie CC, Harris MI. Mortality in adults with and without diabetes in a national cohort of the US population, 1971–1993. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(7):1138–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Geiss LS, Saaddine JB, Thompson TJ. Impact of recent increase in incidence on future diabetes burden: US, 2005–2050. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(9):2114–2116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003. Pub. L. No. 108–173(2003). Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-108publ173/html/PLAW-108publ173.htm. Accessed June 8, 2012.

- 8. US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging. Older Americans Act: a layman's guide. Available at: http://www.co.pierce.wa.us/xml/abtus/ourorg/humsvcs/altc/pierceseniorinfoolderamericansactguide.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2011.

- 9.Geiss LS, Pan L, Cadwell B, Gregg EW, Benjamin SM, Engelgau MM. Changes in incidence of diabetes in U.S. adults, 1997–2003. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(5):371–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashkenazy R, Abrahamson MJ. Medicare coverage for patients with diabetes: a national plan with individual consequences. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(4):386–392 Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1484724. Accessed November 22, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Decker FH, Luo Het al. Trends in the prevalence and comorbidities of diabetes mellitus in nursing home residents in the US: 1995–2004. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):724–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resnick HE, Heineman J, Stone R, Shorr RI. Diabetes in U.S. nursing homes, 2004. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(2):287–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Diabetes Association Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2007. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(3):596–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss CO, Boyd CM, Yu Q, Wolff JL, Leff B. Patterns of prevalent major chronic disease among older adults in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298(10):1160–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engelgau MM, Geiss LS, Saaddine JBet al. The evolving diabetes burden in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(11):945–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vijan S, Hayward RA, Langa KM. The impact of diabetes on workforce participation: results from a national household sample. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(6 pt 1):1653–1669 Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00311.x/abstract. Accessed November 22, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langa KM, Vijan S, Hayward RAet al. Informal caregiving for diabetes and diabetic complications among elderly Americans. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(3):S177–S186 Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11983744. Accessed November 22, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hormone Foundation, National Caregivers Alliance Key findings from the 2009 Diabetes Caregiver Survey. Available at: http://www.hormone.org/Public/upload/diabetes-caregiver-survey.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2011

- 19.Haas LB. Caring for community-dwelling older adults with diabetes: perspectives from health care providers and caregivers. Diabetes Spectr. 2006;19(4):240–244 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang ES. Appropriate application of evidence to the care of elderly patients with diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2007;3(4):260–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morley JE. Diabetes and aging: epidemiologic overview. Clin Geriatr Med. 2008;24(3):395–405, v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Diabetes Translation, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Diabetes complications—cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevalence. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/cvd/fig4.htm. Accessed November 22, 2011

- 23.Pearte CA, Furberg CD, O'Meara ESet al. Characteristics and baseline predictors of future fatal versus nonfatal coronary heart disease events in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 2006;113(18):2177–2185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kronmal RA, Barzilay JI, Smith NLet al. Mortality in pharmacologically treated older adults with diabetes: the Cardiovascular Health Study, 1989–2001. PLoS Med. 2006;3(10):e400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bethel MA, Sloan FA, Belshy D, Feinglos MN. Longitudinal incidence and prevalence of adverse outcomes of diabetes mellitus in elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(9):921–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sloan FA, Bethel MA, Ruiz D, Jr, Shea AH, Feinglos MN. The growing burden of diabetes mellitus in the US elderly population [correction appears in Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(8):860. Shea, Alisa H (corrected to Shea, Alisa M)]. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(2):192–199; discussion 199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Diabetes Translation, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Hospitalization for CVD. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/hosp/adulttable2.htm. Accessed November 22, 2011

- 28.Zhang X, Saaddine JB, Chou C-Fet al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the United States, 2005–2008. JAMA. 2010;304(6):649–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rein DB, Zhang P, Wirth KEet al. The economic burden of major adult visual disorders in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(12):1754–1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foley RN, Collins AJ. The growing economic burden of diabetic kidney disease. Curr Diab Rep. 2009;9(6):460–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan S, Amedia CA., Jr Economic burden of chronic kidney disease. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(3):422–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams ME. Diabetic CKD/ESRD 2010: a progress report? Semin Dial. 2010;23(2):129–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Institutes for Health, National Kidney Disease and Education Program. Available at: http://www.nkdep.nih.gov/learn/are-you-at-risk.shtml. Accessed November 22, 2011.

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Diabetes Translation, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/kidney_Factsheet.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2011

- 35.Collins AJ, Vassalotti JA, Wang Cet al. Who should be targeted for CKD screening? Impact of diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(suppl 3):S71–S77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevens LA, Li S, Wang Cet al. Prevalence of CKD and comorbid illness in elderly patients in the United States: results from the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(3 suppl. 2):S23–S33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boussageon R, Bejan-Angoulvant T, Saadatian-Elahi Met al. Effect of intensive glucose lowering treatment on all cause mortality, cardiovascular death, and microvascular events in type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ninomiya T, Zoungas S, Neal Bet al. Efficacy and safety of routine blood pressure lowering in older patients with diabetes: results from the ADVANCE trial. J Hypertens. 2010;28(6):1141–1149 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilhelm-Leen ER, Hall YN, Tamura MK, Chertow GM. Frailty and chronic kidney disease: the Third National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Survey. Am J Med. 2009;122(7):664–671 Available at: http://download.journals.elsevierhealth.com/pdfs/journals/0002-9343/PIIS0002934309002824.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yaffe K, Ackerson L, Tamura MKet al. Chronic kidney disease and cognitive function in older adults: findings from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Cognitive Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(2):338–345 Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02670.x/pdf. Accessed November 22, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schoolwerth AC, Engelgau MM, Hostetter THet al. Chronic kidney disease: a public health problem that needs a public health action plan. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A57 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2006/apr/05_0105.htm. Accessed November 22, 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xue JL, Eggers PW, Agodoa LY, Foley RN, Collins AJ. Longitudinal study of racial and ethnic differences in developing end-stage renal disease among aged Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(4):1299–1306 Available at: http://jasn.asnjournals.org/cgi/content/full/18/4/1299. Accessed November 22, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurella M, Covinsky KE, Collins AJ, Chertow GM. Octogenarians and nonagenarians starting dialysis in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(3):177–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burrows NR, Li Y, Geiss LS. Incidence of treatment for end-stage renal disease among individuals with diabetes in the U.S. continues to decline. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(1):73–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldfarb-Rumyantzev AS, Rout P. Characteristics of elderly patients with diabetes and end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2010;23(2):185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saaddine JB, Honeycutt AA, Narayan KM, Zhang X, Klein R, Boyle JP. Projection of diabetic retinopathy and other major eye diseases among people with diabetes mellitus: United States, 2005–2050. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(12):1740–1747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crews JE, Campbell VA. Vision impairment and hearing loss among community-dwelling older Americans: implications for health and functioning. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):823–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pasquale LR, Kang JH, Manson JE, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Hankinson SE. Prospective study of type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of primary open-angle glaucoma in women. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(7):1081–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vinik AI, Strotmeyer ES, Nakave AA, Patel CV. Diabetic neuropathy in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2008;24(3):407–435, v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gregg EW, Sorlie P, Paulose-Ram Ret al. Prevalence of lower-extremity disease in the US adult population ≥ 40 years of age with and without diabetes: 1999–2000 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(7):1591–1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwartz AV, Hillier TA, Sellmeyer DEet al. Older women with diabetes have a higher risk of falls: a prospective study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(10):1749–1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Diabetes Translation, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Hospital discharge rates for nontraumatic lower extremity amputation per 1,000 diabetic population, by age, United States, 1980–2005. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/lea/fig4.htm. Accessed November 22, 2011

- 53.Vinik AI, Ziegler D. Diabetic cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy. Circulation. 2007;115(3):387–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bainbridge KE, Hoffman HJ, Cowie CC. Diabetes and hearing impairment in the United States: audiometric evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2004. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(1):1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith TL, Raynor E, Prazma J, Buenting JE, Pillsbury HC. Insulin-dependent diabetic microangiopathy in the inner ear. Laryngoscope. 1995;105(3 pt 1):236–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tomlinson DR, Fernyhough P, Diemel LT, Maeda K. Deficient neurotrophic support in the aetiology of diabetic neuropathy. Diabet Med. 1996;13(7):679–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ristow M. Neurodegenerative disorders associated with diabetes mellitus. J Mol Med (Berl). 2004;82(8):510–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheng YJ, Gregg EW, Saaddine JB, Imperatore G, Zhang X, Albright A. Three decade change in the prevalence of hearing impairment and its association with diabetes in the United States. Prev Med. 2009;49(3):360–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saunders GH, Echt KV. An overview of dual sensory impairment in older adults: perspectives for rehabilitation. Trends Amplif. 2007;11(4):243–258 Available at: http://tia.sagepub.com/content/11/4/243.long. Accessed June 8, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu FP, Lin KP, Kuo HK. Diabetes and the risk of multi-system aging phenotypes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4(1):e4144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Araki A, Ito H. Diabetes mellitus and geriatric syndromes. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2009;9(2):105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):780–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gregg EW, Beckles GLA, Williamson DFet al. Diabetes and physical disability among older U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(9):1272–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gregg EW, Mangione CM, Cauley JAet al. Diabetes and incidence of functional disability in older women. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(1):61–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gregg EW, Caspersen CJ. Physical disability and the cumulative impact of diabetes in older adults. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis. 2005;5(1):13–17 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalyani RR, Saudek CD, Brancati FL, Selvin E. Association of diabetes, comorbidities, and A1C with functional disability in older adults: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1999–2006. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(5):1055–1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park SW, Goodpaster BH, Strotmeyer ESet al. Decreased muscle strength and quality in older adults with type 2 diabetes: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. Diabetes. 2006;55(6):1813–1818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Park SW, Goodpaster BH, Strotmeyer ESet al. Accelerated loss of skeletal muscle strength in older adults with type 2 diabetes: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1507–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hanlon JT, Landerman LR, Fillenbaum GG, Studenski S. Falls in African American and White community-dwelling elderly residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(7):M473–M478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reyes-Ortiz CA, Al Snih S, Loera J, Ray LA, Markides K. Risk factors for falling in older Mexican Americans. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3):417–422 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee PG, Cigolle C, Blaum C. The co-occurrence of chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes: the Health and Retirement Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(3):511–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang ES, Karter AJ, Danielson KK, Warton EM, Ahmed AT. The association between the number of prescription medications and incident falls in a multi-ethnic population of adult type-2 diabetes patients: the Diabetes and Aging Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(2):141–146 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brown AF, Mangione CM, Saliba D, Sarkisian CA, California Healthcare Foundation/American Geriatrics Society Panel on Improving Care for Elders With Diabetes. Guidelines for improving the care of the older person with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5 suppl guidelines):S265–S280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rajagopalan S. Serious infections in elderly patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(7):990–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dooley KE, Chaisson RE. Tuberculosis and diabetes mellitus: the convergence of two epidemics. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(12):737–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jeon CY, Murray MB. Diabetes mellitus increases the risk of active tuberculosis: a systematic review of 13 observational studies. PLoS Med. 2008;5(7):e152 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JBet al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thompson ND, Perz JF, Moorman AC, Holmberg SD. Nonhospital health care–associated hepatitis B and C virus transmission: United States, 1998–2008. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(1):33–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thompson ND, Perz JF. Eliminating the blood: ongoing outbreaks of hepatitis B virus infection and the need for innovative glucose monitoring techniques. J Diabetes Sci Tech. 2009;3(2):283–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bader MS. Immunization for the elderly. Am J Med Sci. 2007;334(6):481–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fiore AE, Shay DK, Haber Pet al. Prevention and control of influenza. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-6):1–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Diabetes Translation, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Age-adjusted percentage of adults aged 18 years or older with diagnosed diabetes receiving an influenza vaccination in the last year, United States, 1993–2008. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/preventive/tFluAgeTot.htm. Accessed November 22, 2011

- 83.Tseng HF, Smith N, Harpaz R, Bialek SR, Sy LS, Jacobsen SJ. Herpes zoster vaccine in older adults and the risk of subsequent herpes zoster disease. JAMA. 2011;305(2):160–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Diabetes Translation, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Periodontal disease. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/OralHealth/topics/periodontal_disease.htm. Accessed November 22, 2011

- 85.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Oral health for older Americans. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/OralHealth/publications/factsheets/adult_older.htm. Accessed November 22, 2011

- 86.Kapp JM, Boren SA, Yun S, LeMaster J. Diabetes and tooth loss in a national sample of dentate adults reporting annual dental visits. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4(3):A59 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2007/jul/06_0134.htm. Accessed November 22, 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mealey BL. Periodontal disease and diabetes. A two-way street. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(suppl 2):26S–31S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Löe H. Periodontal disease: the sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(1):329–334 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Taylor GW. Bidirectional interrelationships between diabetes and periodontal diseases: an epidemiologic perspective. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6(1):99–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Khader YS, Dauod AS, El-Qaden SS, Alkafajei A, Batayha WQ. Periodontal status of diabetics compared with nondiabetics: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes Complications. 2006;20(1):59–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Working Together to Manage Diabetes: A Guide for Pharmacists, Podiatrists, Optometrists, and Dental Professionals. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. Available at: http://ndep.nih.gov/media/PPODprimer_color.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 92.Griffin SO, Barker LK, Griffin PM, Cleveland JL, Kohn W. Oral health needs among adults in the United States with chronic diseases. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140(10):1266–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Taylor GW, Borgnakke WS. Periodontal disease: associations with diabetes, glycemic control and complications. Oral Dis. 2008;14(3):191–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]