Abstract

HIV disease is often perceived as a condition affecting young adults. However, approximately 11% of new infections occur in adults aged 50 years or older. Among persons living with HIV disease, it is estimated that more than half will be aged 50 years or older in the near future. In this review, we highlight issues related to HIV prevention and treatment for HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected older Americans, and outline unique considerations and emerging challenges for public health and patient management in these 2 populations.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 10.8% of the roughly 50 000 incident HIV infections that occur annually in the United States are among persons aged 50 years or older1 and that, among persons newly diagnosed with HIV infection in 2010, the median age was 35 to 39 years and 16.5% were aged 50 years or older.2 In high-prevalence areas, HIV infection has been present in up to 5% of persons who died older than 60 years.3

Continued Risk for Older HIV-Uninfected Adults

Although sexual activity declines with age, the majority of Americans aged 57 to 65 years and a substantial fraction aged 66 years or older remain sexually active,4 including persons who are HIV-infected.5 The reasons why older Americans continue to become infected with HIV have not been extensively researched, but the phenomenon is likely multifactorial.6 Older persons, who may include persons who have been recently widowed or divorced after having been in a long-term monogamous relationship, have a poor understanding of their risk for a disease that they often perceive as affecting predominately young people or gay men.6–8 Furthermore, only a minority of patients aged 50 years and older report having discussed sexual activity with their care providers.4 Conversely, care providers are generally poor at routinely collecting and recording sexual histories of their patients, particularly for patients aged 50 years or older,9 possibly because they perceive older patients to be at low risk, they fear insulting or angering an older patient, or because they are personally uncomfortable discussing sexual activity with a person who is the age of their parents or grandparents.

Despite sexual activity and risk for HIV infection, few older Americans use condoms to protect themselves from infection during sexual intercourse. According to the 2008 National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior, among all persons aged 50 years or older, condoms were not used during most recent intercourse with 91.5% of casual partners, 76.0% of friends, 69.6% of new acquaintances, and 33.3% of transactional sexual partners.10

Postmenopausal women who no longer require birth control to prevent pregnancy may not consider the need for condoms during intercourse.11 The decreased levels of circulating estrogen following menopause lead to a thinner vaginal epithelium and decreased mucus production, making these tissues more susceptible to microabrasions that could facilitate HIV infection. Recent data suggest that the postmenopausal cervix may undergo immune changes that also favor HIV acquisition; these tissues become more enriched with target cells (i.e., CD4+ and CCR5+ T cells)12 and produce greater amounts of inflammatory factors that favor HIV replication.13 For older men, the availability of erectile dysfunction medications through both prescription and nonprescription sources and easier access to sexual intercourse, including commercial sexual intercourse, through the Internet and social media, may facilitate capacity for and access to sexual activity.

HIV Testing for Elderly Persons

For the purpose of this review, older refers to persons aged 50 years and older and elderly to persons aged 65 years and older. The CDC has recommended universal opt-out HIV testing of all persons aged 13 to 64 years accessing health care services in private or public settings to reduce the number of HIV-infected Americans who are unaware of their HIV status, and to enable linkage of these persons to HIV care and prevention services.14 Current CDC guidelines do not recommend universal opt-out testing for persons aged 65 years and older, an age group in which HIV prevalence is currently below the threshold at which generalized screening would be considered cost-effective, in part because of the excess costs incurred by the greater proportion of falsely negative tests.15,16 However, this recommendation does not mean that all elderly persons are at low risk. As illustrated previously, many persons aged 50 years or older engage in behaviors that place them at risk for HIV infection.

As the cohort of persons living with HIV ages (see the “Adults Aging With HIV Infection” section), the percentage of HIV-infected adults aged 65 years or older may become large enough to justify universal HIV opt-out testing of this age group. At present, testing persons in this age group should be based on clinical judgment after a thorough assessment of risk including sexual activity, number and types of sexual partners (i.e., commercial sex worker, same-sex partner), and other potential risk factors. All persons, regardless of age, should be tested for HIV before initiating a new sexual relationship. Aging HIV-negative men who have sex with men who continue to have high-risk sexual exposures with HIV-infected partners, may be considered for preexposure prophylaxis.17,18

HIV Risk-Reduction Programs for HIV-Uninfected Older Adults

The need for effective prevention programs for persons aged 50 years and older has been repeatedly recognized,6,7,19,20 including at a White House summit on HIV and aging in October 2010. Although no national prevention programs designed specifically for older Americans were listed in the most recent 2009 national inventory,21 a program has been developed by the Administration on Aging (http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/AoA_Programs/HPW/HIV_AIDS/index.aspx) that includes fact sheets, posters (Figure 1), customizable PowerPoint templates, and an educational video. Additional campaigns have been created by special interest groups, such as “HIV Wisdom for Older Women” (http://www.hivwisdom.org/bio.html), “Services and Advocacy for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Elders (http://sageusa.org/index.cfm), and Safer Sex for Seniors (http://safersex4seniors.org). Local jurisdictions with large numbers of older persons have also created programs such as the Senior HIV Intervention Project in Broward County, Florida,22 and the AIDS Community Research Initiative of America (http://www.acria.org; Figure 1) and Gay Men's Health Crisis (http://www.gmhc.org), which are both based in New York City. Innovative national programs aimed at adults aged 50 years or older have also been started in other countries, such as Brazil, where a campaign aimed at older adults has been linked to important national events such as Carnaval (http://www.aids.gov.br/campanha/carnaval-2009) or the World Cup soccer championship (http://www.aids.gov.br/campanha/dia-mundial-de-luta-contra-aids-2008; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Examples from 3 public health campaigns to increase awareness of HIV risk among older adults, including (a, b) a current campaign developed by the US Administration on Aging, (c, d) a campaign created by the AIDS Community Research Initiative of America with funding from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene conducted in New York City during 2010, and (e, f) a Brazilian public health campaign to promote HIV awareness and condom use among older persons used during Carnaval 2009 and the World Cup soccer championship in 2010.

Note. The Brazilian images read (e) “Mature Woman's Club [in circle]. Use Condoms. The Safe Woman's Choice.” and (f) “Condoms after 50: Try It.” Both feature the statement “Sex doesn't depend on age. Neither does protection.”

Adults Aging With HIV Infection

The increasingly longer survival afforded by highly active combination antiretroviral therapy (cART)23,24,25 and ongoing new infections among persons older than 50 years (close to 5400 per year or 10.8% of all new infections from 2006 to 2009)1 are steadily shifting the demographic profile of the US HIV epidemic toward older age groups. CDC estimated that in 2009 persons aged 50 years and older constituted 33% of all persons living with HIV infection in the 46 states with confidential name-based HIV infection reporting (Figure 2). Assuming a conservative annual increase in this prevalence of 1.5% based on data from 2007 to 2009 and that these data from states with stable systems for reporting HIV infections are nationally generalizable (since 2011, all states now use confidential name-based reporting), then by 2020 more than 50% of persons living with HIV infection would be aged 50 years or older.

FIGURE 2—

Estimated numbers of persons living with HIV, by year and selected characteristics in (a) 2007 and (b) 2009: 46 states with confidential name-based reporting of HIV infections to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Note. In 2007, the median age was 40-44 years, and 28.6% were aged ≥ 50 years. In 2009, the median age was 45–49 years, and 32.7% were aged ≥ 50 years.

Many of the sociodemographic disparities observed in the overall US epidemic also persist in older age groups. Persons aged 50 years and older living with HIV infection are often male, Black, men who have sex with men, and concentrated in large urban areas.2,26–28 During the 2005 to 2008 period, the estimated rate of new HIV diagnoses among Blacks aged 50 years and older was 12.6 times as high as the rate among Whites of the same age group (49.2 vs 3.9 per 100 000, respectively); among Hispanics this rate was 5 times as high (19.5 per 100 000) as among Whites.26

Older Adults More Likely to Be Diagnosed Late With HIV

With the continued reductions in mortality and morbidity among HIV-infected adults in North America and Europe, epidemiologists estimate that persons newly diagnosed with HIV infection who are engaged and retained in care can expect to live anywhere from an additional 20 years to a nearly normal lifespan.23,25,29–32 However, these improvements mask notable negative trends when survival data are stratified by age. First, a significantly greater fraction of older persons are diagnosed with HIV infection late in the course of their disease having missed the opportunity to receive care that prevents ongoing damage to the immune system. A recent study from a large national cohort of HIV-infected adults demonstrated 3 important findings: (1) the proportion of individuals presenting for HIV care between 1997 and 2007 who were aged 50 years or older increased from 17% to 27% (P < .01), (2) the median CD4 cell counts at first presentation to care were consistently lower for persons aged 50 years or older compared with younger adults (on average by about 50 cells or 15%; Figure 3), and (3) a greater proportion of older individuals had an AIDS-defining diagnosis at, or within 3 months before, their first presentation for HIV care compared with younger individuals (13% vs 10%, respectively).33

FIGURE 3—

Median CD4 cell count, and the proportion of individuals who have a CD4 cell count greater than or equal to 350 cells/mm3, at first presentation for HIV clinical care in the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD).

Source. Reproduced with permission from Althoff et al.33

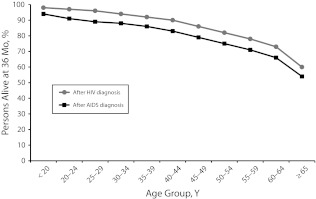

Late HIV diagnoses and poorer prognosis among persons diagnosed at an older age are also reflected in the national HIV surveillance data. In the 46 states with long-established confidential name-based reporting of HIV infections to CDC, 14% of persons younger than 25 years diagnosed with HIV infection during 2009 progressed to AIDS in 1 year compared with 42% of persons aged 50 to 54 years, 45% of persons aged 55 to 59 years, and 49% of persons aged 60 years or older (Figure 4). Furthermore, survival declined with age at diagnosis, whether diagnosed with HIV infection or AIDS. For instance, 3-year survival for persons younger than 25 years diagnosed with either outcome was equal to or greater than 95% compared with 82% and 75%, respectively, for persons aged 50 to 54 years, 78% and 71% for persons aged 55 to 59 years, and 73% and 66% for persons aged 60 years or older (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4—

Percentage of persons diagnosed with AIDS less than 12 months after HIV diagnosis: 46 states with confidential name-based HIV infection reporting, 2009.

FIGURE 5—

Percentage of persons alive at 36 months by type of diagnosis: 46 states with confidential name-based HIV infection reporting, 2009.

Inferior Responses to Antiretroviral Therapy in Elderly

Persons who are newly diagnosed with HIV infection, including those aged 50 years and older, should be offered HIV antiretroviral therapy regardless of CD4 cell count.34 Older patients may adhere better to antiretroviral therapy35 but appear equally likely to achieve virologic suppression compared with younger patients.36 Nonetheless, older patients with suppressed HIV RNA viral loads consistently experience less robust CD4 count responses,36,37 most likely because CD4 cell–mediated immune reconstitution depends on thymic function, which decreases with age.

Response in older patients also does not appear to vary whether the regimen used is protease inhibitor–based or non–nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor–based.36 Treatment guidelines now recommend initiating antiretroviral therapy immediately after HIV diagnosis regardless of CD4 cell count for all older patients,34,38 but further research is needed to inform preferred regimens for this age group. Important issues include selecting regimens with a minimal number of toxicities and reviewing comprehensively other medical conditions and medications to minimize drug–drug interactions.

Burden of Select Chronic Illnesses Among HIV-Infected Patients

As HIV-infected adults live longer, they are increasingly affected by a number of chronic illnesses that are also common in the general population but that seem to occur at rates greater than expected for age. These conditions include cardiovascular disease, renal and hepatic disorders, osteopenia and bone fractures, endocrine and metabolic abnormalities (e.g., lipodystrophy or abnormal fat redistribution, metabolic syndrome), and certain non–AIDS-defining cancers (e.g., liver, lung, anal).39–43 As rates of these conditions have increased, there has been a remarkable coincident shift in the predominant causes of death from AIDS-related opportunistic illnesses to non–AIDS-related causes, in particular hepatic cirrhosis, renal failure, cardiovascular events (e.g., myocardial infarction, stroke), and malignancy.44–47 Apart from the expected contribution of normal aging, 3 additional sets of factors contribute to risk, to varying degrees and often in complex interplay48: (1) factors associated directly with chronic HIV infection including viral replication and attendant inflammation,40–51 (2) toxicities and other complications of treatment with antiretroviral agents,52 and (3) host-related factors that are especially prevalent among HIV-infected adults, including certain coinfections (e.g., human papillomavirus, hepatitis B); and lifestyle factors (e.g., alcohol and tobacco use, obesity53–55; Figure 6). We will highlight select conditions that commonly affect aging HIV-infected patients in the United States.

FIGURE 6—

Factors contributing to the phenomenon often termed “premature aging.”

Source. Reproduced and adapted with permission from Deeks and Phillips.56

Cardiovascular disease.

HIV-infected patients have greater 10-year risk of cardiovascular events57 and higher rates of atherosclerosis than HIV-uninfected persons.54,58 The landmark international Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy study demonstrated definitively that episodic untreated HIV replication and consequent immune activation and inflammatory responses were associated with elevated risk not only of death from any cause (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.6; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.9, 3.7) but notably (and unexpectedly at the time) of incident major cardiovascular, renal, and hepatic disease (HR = 1.7; 95% CI = 1.1, 2.5).59 Subsequent research has confirmed that HIV infection itself is associated with greater risk of atherosclerosis independent of viral load, type of antiretroviral therapy, or extent of immunodeficiency.54 However, whether HIV infection is itself truly an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease that can be modified by treatment remains controversial; randomized clinical trial data are lacking and the best existing data come from observational cohort studies that must be interpreted cautiously.60

Antiretroviral treatment and the extent of immunodeficiency can also alter cardiovascular risk. Certain antiretrovirals alter lipid metabolism creating an atherogenic cholesterol profile; these and other antiretrovirals (e.g., abacavir) may also have additional but as yet unidentified effects that increase risk for acute coronary syndrome.61,62 A low CD4 cell count has been found to be an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease comparable in attributable risk to several traditional risk factors (e.g., male gender, low high-density lipoprotein, elevated low-density lipoprotein, tobacco smoking).63

There is accumulating evidence that the increase in risk conferred by exposure to certain antiretroviral medications (most notably, the protease inhibitors) is generally moderate compared with the risk conferred by traditional demographic (e.g., age, sex, and race) and modifiable risk factors (e.g., smoking, obesity, and hypertension), as well as by HIV itself.61 In the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs study of more than 23 000 patients followed during 1999 to 2005, for instance, the adjusted relative rate of myocardial infarction per year of protease inhibitor exposure was 1.10 (95% CI = 1.04, 1.18), compared with 1.32 (95% CI = 1.23, 1.41) per 5 years of age but 2.92 (95% CI = 2.04, 4.18) for current tobacco smoking.61

Although HIV and its treatment likely contribute to cardiovascular disease risk, the largest contributors remain modifiable lifestyle factors and treatable chronic comorbidities. Estimated tobacco smoking rates among HIV-infected US adults since 2000 have ranged from 47% to 70%64 compared with rates of less than 25% in the general population.65 Increasing attention has been focused on smoking cessation programs tailored for this high-risk group.66,67 Increasing attention has also been drawn to the high prevalences among HIV-infected patients of dyslipidemia and metabolic syndrome,52,53 which predispose to cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Lastly, since the advent of effective therapy, the prevalence of obesity among HIV-infected persons has steadily increased. For a disease hallmarked originally by wasting, overweight and obese patients now often outnumber underweight patients in many clinical settings.68–70

Bone health.

Low bone mineral density (BMD) is remarkably prevalent among HIV-infected adults; up to 60% have been estimated to have osteopenia and up to 15% osteoporosis,71–74 rates that are much higher than for demographically matched non–HIV-infected patients.74 HIV-infected adults also experience higher rates of fragility fractures than comparable non–HIV-infected adults after adjustment for known risk for bone fracture including older age, illicit substance use, and hepatitis C coinfection.43,72,75 Among HIV-infected patients, those who have experienced greater immunosuppression, defined as a nadir CD4 cell count less than 200 cells/mm3, experienced rates of fracture 60% greater than patients who had never been severely immunosuppressed.43 A causal relationship between low BMD and greater fracture risk has yet to be established, and no research has yet addressed the population benefit of routine BMD assessment, treatment of low BMD, and whether assessment of BMD when aged younger than 50 years might be warranted for HIV-infected adults. Some experts have advocated conducting BMD assessments for patients with fragility fractures, all HIV-infected postmenopausal women, and all HIV-infected men aged 50 years and older.76 Considering that risk for and frequency of falls increases substantially with age,77 research is needed to address how and when best to screen for and correct reversible causes of low BMD and fall risk for HIV-infected patients in routine care.

Cancers.

An increasing number of HIV-infected persons are experiencing non–AIDS-defining cancers that typically occur at older ages.78–80 A large US study81 has documented that in a demographically diverse national cohort of 55 000 HIV-infected patients during 1992 through 2003, compared with the general population of similar demographics, the incidence of the following non–AIDS-defining cancers was higher among HIV-infected persons: anal, vaginal, Hodgkin's lymphoma, liver, lung, melanoma, oropharyngeal, leukemia, colorectal, and renal. Compared with non–HIV-infected counterparts, HIV-infected persons are at particular risk for cancers with a known infectious cause,80,82 although this higher risk has decreased in the antiretroviral therapy era.80 A national study by Shiels et al.78 documented substantial increases in non–AIDS-defining cancers among HIV-infected persons over a 15-year period (1991–2005); whereas counts of AIDS-defining cancers decreased, non–AIDS-defining cancers increased by approximately threefold (3193 to 10 059 cancers; P for trend < .001) and were mainly driven by growth and aging of the HIV-infected population afforded in large part to effective antiretroviral therapy. Notably, an examination of 212 055 persons with AIDS enrolled in the US HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study from 1996 to 2007 revealed that, after adjustment for differences in the populations at risk, the median ages at cancer diagnosis among persons with AIDS (i.e., only persons with the most advanced stage of HIV disease) and persons in the general population did not differ for most types of cancer (e.g., colon, prostate, or breast cancer). By contrast, ages at diagnosis of lung cancer (median = 50 vs 54 years) and anal cancer (median = 42 vs 45 years) were significantly younger in persons with AIDS than expected in the general population (P < .001).83 Although the appearance of most cancers in HIV-infected persons may not be actually occurring at younger-than-expected ages, a growing burden of non–AIDS-defining cancers in the aging HIV-infected population requires targeted cancer prevention and treatment strategies. In addition to aspects of HIV infection that may be amenable to treatment (e.g., immunodeficiency, inflammatory responses to chronic viremia), associated preventable or treatable viral coinfections (e.g., human papillomavirus, hepatitis B and C) and preventable lifestyle factors traditionally associated with cancer (e.g., tobacco smoking, alcohol use, obesity) contribute to patients’ risk of non–AIDS-defining malignancies.

Frailty.

Frailty is a late-stage clinical syndrome associated with adverse health outcomes, including mortality.84,85 Frailty is characterized by multiple pathologies, including weakness, low physical activity, and slow motor performance. This geriatric syndrome also occurs among HIV-infected persons, albeit at a younger age.84 Among men followed in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, prevalence of the frailty-related phenotype for 55-year-old men infected with HIV for 4 years or less (3.4%; 95% CI = 1.3, 8.6) was similar to that of uninfected men aged 65 years and older (3.4%; 95% CI = 1.5, 7.6). This phenotype was associated with increased duration of HIV infection, markers of advanced immunodeficiency, comorbidity, and negative clinical outcomes, and subsided upon immunologic restoration related to treatment with cART.85 Analyses from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study have found that, across the age groups, decline in physical function per year was greater in HIV-infected patients than in uninfected patients, but this difference was modest.86 A study of 455 HIV-infected persons with a median age of 41.7 years (71% male, 63% Black, with a mean 8.4 years since HIV diagnosis, 75% on cART with median CD4 of 437 cells/mm3) found that the frequency of frailty (defined by presence of at least 3 of 5 criteria: weight loss, low physical activity, exhaustion, weak grip strength, and slow walking time) was 9%, substantially higher than would be expected for this age group.87 Factors associated with frailty in that study included unemployment, greater number of comorbid conditions and past opportunistic illnesses, and higher depression severity score; hospitalization rates were greater and inpatient stays 5-fold longer for frail persons compared with non-frail persons.

Psychiatric and Neurocognitive Conditions.

HIV-infected patients experience a higher frequency of neurocognitive and psychiatric problems, including depression, than do age-matched HIV-negative controls, even after adjusting for contributory sociodemographic and behavioral risk factors (e.g., alcohol and drug use) that are known to be more prevalent among HIV-infected persons.39,55,88 Although psychiatric illness can increase the risk of HIV acquisition, in most cases HIV is probably not causally related to psychiatric illness, such as through direct effects of the virus on the central nervous system. Living with a chronic, life-threatening, and highly stigmatized illness can exacerbate or trigger thought and mood disorders. Regular screening for psychiatric illness, especially depression, is therefore an important part of comprehensive HIV care. Depression is not only the most common psychiatric condition affecting HIV-infected adults, among whom it is remarkably underrecognized and undertreated,89 but both depressive symptoms and suicide are also most frequent among older persons, especially the elderly aged 65 years and older.90

Use of cART has been shown to restore neurocognitive performance in HIV-infected women,91 although a history of profound immunosuppression (nadir CD4 cell count < 200 cells/mm3) and inflammatory state may have persistent effects on neurocognitive impairment among patients in the cART era.92,93 Treatment of depression in HIV-infected patients correlates with improvements in antiretroviral medication adherence, virologic responses, and survival.94,95

Whether HIV Infection Accelerates Aging

“Accelerated” or “precocious” aging are terms often used to describe the appearance of conditions that traditionally affect older persons at a younger than expected age. Whether HIV infection accelerates aging remains an open question.96,97 As noted previously, a growing number of comorbid medical conditions seem to be more common in HIV-infected patients, and both these conditions and their biological precursors may occur among HIV-infected persons at younger ages than would be expected.39,75,84 However, rather than directly mediating (i.e., accelerating) the aging process, HIV infection may simply contribute to increasing the frequency and severity of chronic diseases as do other independent risk factors (e.g., tobacco smoking or poor diet), and thus lead to increased prevalence of these conditions among HIV-infected patients compared with uninfected controls of the same age. In addition, the HIV-infected population in the United States is enriched in patients with sociodemographic risk factors that predispose to chronic diseases, such as male gender, non-White race/ethnicity, and poverty, as well as tobacco and alcohol use.40 If comparisons are made of HIV-infected persons to persons from the general population without controlling for differences in the prevalence of such risk factors, then it is possible that the age of onset for certain conditions (e.g., cardiovascular disease) could appear precocious. Furthermore, as elegantly shown by Shiels et al.,83 the observation that certain conditions associated with aging, such as cancer, appear to affect HIV-infected adults at younger ages than adults in the general population may be an artifact of different age structures of the 2 populations.

It is interesting that HIV infection impairs the function of the immune system in many of the same ways as aging. The hallmark of HIV infection is its persistent destruction of CD4+ T cells that progressively depletes the immune system's capacity to carry out effective immunosurveillance. As reviewed recently by Effros et al.,97 aging—like HIV infection—is also associated with B cell dysfunction (most notably the inability to produce effective antibody responses), thymus involution, and decreases in the number of naïve T cells (both CD4+ and CD8+), and T-cell hyporesponsiveness and eventual replicative senescence.

The strongest evidence for an association between HIV infection and acceleration of the aging process comes from studies of immunosenescence and immune activation.91–101 For example, in a recent analysis from the Women's Interagency HIV Study, HIV-associated T-cell changes (including higher frequencies of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and immunosenescent CD8+ T cells) were associated with subclinical carotid artery abnormalities, even among patients achieving viral suppression with effective cART.102 These emergent and compelling basic science data will be important to consider as we design future studies to examine how and why the manifestation of certain comorbidities may differ between HIV-infected and non–HIV-infected adults as they age.

Importance of Primary and Preventive Care

For patients who are effectively retained in HIV care, the recommended frequency of medical encounters (typically 2 to 4 times yearly)34,103 offers repeated opportunities for preventive care, including brief messages regarding the importance of smoking cessation, exercise and dietary modifications, and other lifestyle changes to prevent or better manage various chronic diseases. Routine age-appropriate cancer screenings (e.g., mammography, colonoscopy, cervical Papanicolaou tests) as well as screening for and treatment of cardiovascular disease according to guidelines need to be ensured. Additional research is needed to inform guidelines development104 regarding the value of earlier or more intensive screening for certain types of cancer (e.g., anal cancer) and low BMD. A significant fraction of HIV-infected patients die from violent and accidental causes related to drug abuse and poor mental health, underscoring the importance of connecting patients to ancillary mental health, substance abuse, and case-management services.105 Midlife and older adults living with HIV may lack community support, typically lack siblings or parents to care for them, and may have experienced multiple AIDS-related losses within their social networks. Case management and integrated care can help them confront the physical and psychosocial aspects of the disease and reduce marginalization and the dual stigma of both aging and HIV.6

Toxicity of Antiretroviral Therapy and Polypharmacy

To date, there have been relatively few data on drug–drug interactions with non-HIV medications and short- and long-term toxicity and tolerability of antiretrovirals in older HIV-infected adults.97 Because many randomized controlled trials evaluating new antiretroviral drugs or chemoprophylaxis of HIV-related complications excluded patients with either advanced age or comorbidities, there are few pharmacokinetic data for persons at the extremes of age. A recent analysis of tipranavir use in relation to the risk of intracranial hemorrhage found that increasing age was a risk factor for such hemorrhage,106 and an expanded-access study found that age was a risk factor for changes in serum creatinine level in patients on tenofovir.107 Older age is associated with a high rate of adverse events from pharmacologic agents; therefore, careful monitoring is essential when one is using antiretrovirals and medications to prevent and to treat opportunistic illness in older HIV-infected patients.108,109

Of note, HIV-infected patients with renal or hepatic insufficiency deserve special attention when certain antiretroviral drugs are used. Both renal and hepatic injury are more common among older individuals with HIV, especially among older individuals with histories of heavy drug or alcohol use.110 Tenofovir and indinavir have nephrotoxic potential.111 In addition, tenofovir, which must be dose-adjusted based on estimated creatinine clearance (i.e., reduced dosage with reduced clearance), may be more likely to cause complications in elderly patients who have lower creatinine clearance than younger patients. Some protease inhibitors and non–nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors can exacerbate hepatic insufficiency in persons with preexisting liver disease; however, there is little information on how to adjust dosages of these drugs in older patients with impaired renal or hepatic clearance.

Pharmacologic interactions between antiretroviral agents and other drugs used in the elderly are common. Extensive review of all medications prescribed by all medical providers (including over-the-counter medications), such as through medication therapy management by a pharmacist familiar with HIV care, may reduce the risk of drug–drug interactions. For example, proton pump inhibitors, which are commonly used in patients with dyspepsia, are contraindicated with atazanavir because they decrease gastrointestinal absorption of this protease inhibitor. In addition, concomitant use of benzodiazepines and protease inhibitors can result in excessive sedation. Therapeutic drug monitoring may be useful in patients who are at high risk for adverse events.

PUBLIC HEALTH NEED AND OPTIONS FOR ACTION

With regard to elderly non–HIV-infected persons, the key take-home messages for the general practitioner include:

Improve behavioral risk assessment.

Increase routine screening for HIV infection, and improve linkage to HIV care, if infected.

The key messages for the public health practitioner include increasing awareness about the risk for HIV infection and the importance of its early diagnosis and treatment among older adults and among their caregivers.

Despite evidence that aging Americans remain sexually active and account for about 11% of incident HIV infections each year, many may not perceive themselves as at risk for HIV infection despite unsafe sexual behavior, which often goes unmentioned or unaddressed in interactions with their primary care providers. Health care and service providers on all levels should be educated on HIV risk behaviors and symptoms of HIV infection (both acute infection and advanced HIV illness); they need to conduct thorough sexual and drug-use risk assessments with their older clients and offer both routine HIV screening14,15,112 and diagnostic HIV testing, as warranted. The CDC recommends routine voluntary HIV screening for all persons aged 13 to 64 years without regard to risk in all health care settings where the prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection is 0.1% or more; HIV testing of persons aged 65 years and older may be considered based on risk history.14 Health departments and community-based organizations in jurisdictions with more than rare cases of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases among older and elderly adults should consider systematic outreach and educational programs to provide seniors with accurate information about the relevance of HIV/AIDS to their lives. Programs aimed at reaching general health practitioners (e.g., opportunities for licensure-related accredited education) should cover clinical vigilance for, testing for, and diagnosis of HIV infection, and the importance of ensuring timely linkage of newly HIV-diagnosed persons to specialty HIV care.

With regard to elderly HIV-infected persons, the key take-home messages for a general practitioner include:

Improve coordination of primary and complex subspecialty care.

Remember to continue age-appropriate preventative screenings.

Incorporate HIV prevention (e.g., brief risk assessment, risk-reduction counseling, testing for sexually transmitted disease) into routine HIV care to prevent ongoing HIV transmission.

The key messages for the public health practitioner include developing a surveillance and research agenda to better characterize the clinical epidemiology of chronic HIV infection in persons aged 50 years and older, and determining appropriate thresholds for general preventative screening practices (e.g., bone densitometry, colorectal cancer assessment) tailored to persons with chronic HIV infection.

In the pre- and early cART era, HIV-infected patients mostly succumbed to opportunistic illnesses and were cared for chiefly by infectious disease practitioners. As mentioned before, a large proportion of today's patients are living with and being hospitalized for traditionally non–HIV-related chronic medical conditions113 and have a greater likelihood of death from these causes than from AIDS.44,46,47 As HIV-infected patients age and experience multiple comorbidities, the integration of HIV care and primary care becomes ever more important.104 HIV providers should be comfortable with standard chronic disease management and coordinate care with specialists as needed (e.g., cardiologists, nephrologists, oncologists). Programs aimed at reaching general health practitioners should cover the importance of ensuring linkage of newly HIV-diagnosed persons to specialty HIV care and attention to coordination of primary and complex subspecialty care that older HIV-infected patients often require. Finally, primary care providers should engage their HIV-infected patients in discussions of sexual health, to encourage HIV disclosure and condom use to prevent HIV transmission to sexual partners. Programs such as Ask–Screen–Intervene (http://depts.washington.edu/nnptc/online_training/asi) and Prevention IS Care (http://www.actagainstaids.org/promote/pic/index.html) are brief provider-driven prevention interventions developed to provide clinicians practical tools they can integrate into their daily practice to help their HIV-infected adult patients reduce the risk of transmitting HIV to others and to maintain sexual health. National guidelines for incorporating HIV prevention into the medical care of persons living with HIV infection first published in 2003112 are undergoing revision; these guidelines are a valuable resource for clinicians and public health practitioners seeking a broader set of constructive and specific recommendations about best practices.

Acknowledgments

This article was prepared for the CDC series on aging and the roles of public health.

Note. The findings and conclusions in this report arethose of the authors and do not necessarily represent theofficial position of the CDC.

Human Participant Protection

Human participant protection was not required because no human participants were involved.

References

- 1.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez Aet al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e17502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2010, Vol. 22. Published March 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports. Accessed May 25, 2012.

- 3.el-Sadr W, Gettler J. Unrecognized human immunodeficiency virus infection in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(2):184–186 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O'Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):762–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onen NF, Shacham E, Stamm KE, Overton ET. Comparisons of sexual behaviors and STD prevalence among older and younger individuals with HIV infection. AIDS Care. 2010;22(6):711–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy JA, Ory MG, Crystal S. HIV/AIDS interventions for midlife and older adults: current status and challenges. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(Suppl 2):S59–S67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savasta AM. HIV: associated transmission risks in older adults—an integrative review of the literature. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2004;15(1):50–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henderson SJ, Bernstein LB, George DM, Doyle JP, Paranjape AS, Corbie-Smith G. Older women and HIV: how much do they know and where are they getting their information? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(9):1549–1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loeb DF, Lee RS, Binswanger IA, Ellison MC, Aagaard EM. Patient, resident physician, and visit factors associated with documentation of sexual history in the outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(8):887–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schick V, Herbenick D, Reece Met al. Sexual behaviors, condom use, and sexual health of Americans over 50: implications for sexual health promotion for older adults. J Sex Med. 2010;7(Suppl 5):315–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindau ST, Leitsch SA, Lundberg KL, Jerome J. Older women's attitudes, behavior, and communication about sex and HIV: a community-based study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2006;15(6):747–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meditz A, Moreau K, MaWhinney Set al. CCR5 expression is elevated on endocervical CD4+ T cells in healthy postmenopausal women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(3):221–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rollenhagen C, Asin S. Enhanced HIV-1 replication in ex vivo ectocervical tissues from post-menopausal women correlates with increased inflammatory responses. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4(6):671–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MAet al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders GD, Bayoumi AM, Holodnly M, Owens DK. Cost-effectiveness of HIV screening in patients older than 55 years of age. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(12):889–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paltiel AD, Weinstein MC, Kimmel ADet al. Expanded screening for HIV in the United States—an analysis of cost-effectiveness. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):586–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PLet al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith DK, Grant RM, Weidle PJ, Lansky A, Mermin J, Fenton KA. Interim guidance: preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in men who have sex with men [Reprinted from MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:65–68]. JAMA. 2011;305(11):1089–1091. [PubMed]

- 19.Tabnak F, Sun R. Need for HIV/AIDS early identification and preventive measures among middle-aged and elderly women. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(2):287–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gay Men's Health Crisis Growing Older With the Epidemic: HIV and Aging. 2010. Available at: http://www.gmhc.org/files/editor/file/a_pa_aging10_emb2.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2012

- 21. National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors and the Kaiser Family Foundation. The National HIV Prevention Inventory: The State of HIV Prevention Across the U.S. 2009. Available at: http://www.nastad.org/Docs/highlight/2010313_NASTAD%20Prevention%20Inventory%20-%20REVISED.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2012.

- 22.Agate LL, Mullins JM, Prudent ES, Liberti TM. Strategies for reaching retirement communities and aging social networks: HIV/AIDS prevention activities among seniors in South Florida. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(Suppl 2):S238–S242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet. 2008;372(9635):293–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Losina E, Schackman BR, Sadownik SNet al. Racial and sex disparities in life expectancy losses among HIV-infected persons in the United States: impact of risk behavior, late initiation, and early discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(10):1570–1578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakagawa F, Lodwick RK, Smith CJet al. Projected life expectancy of people with HIV according to timing of diagnosis. AIDS. 2012;26(3):335–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linley L, Prejean J, Ann Q, Chen M, Hall HI. Racial/ethnic disparities in HIV diagnoses among persons aged 50 years and older in 37 US states, 2005-2008. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(8):1527–1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Advancing HIV prevention: new strategies for a changing epidemic—United States, 2003. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(6):935. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Hall HI, Espinoza L, Benbow N, Hu YYW, Urban Areas HIV Surveillance Workgroup. Epidemiology of HIV infection in large urban areas in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(9):e12756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhaskaran K, Hamouda O, Sannes Met al. Changes in the risk of death after HIV seroconversion compared with mortality in the general population. JAMA. 2008;300(1):51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.May M, Sterne JA, Sabin Cet al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients up to 5 years after initiation of HAART: collaborative analysis of prospective studies. AIDS. 2007;21(9):1185–1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ewings FM, Bhaskaran K, McLean Ket al. Survival following HIV infection of a cohort followed up from seroconversion in the UK. AIDS. 2008;22(1):89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrison KM, Song RG, Zhang XJ. Life expectancy after HIV diagnosis based on national HIV surveillance data from 25 states, United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(1):124–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Althoff KN, Gebo KA, Gange SJet al. CD4 count at presentation for HIV care in the United States and Canada: are those over 50 years more likely to have a delayed presentation? AIDS Res Ther. 2010;7:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Department of Health and Human Services, Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents—March 27, 2012. Available at: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2012.

- 35.Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Horberg MA, DeLorenze GN, Klein D, Quesenberry CP., Jr Older age and the response to and tolerability of antiretroviral therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):684–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Althoff KN, Justice AC, Gange SJet al. Virologic and immunologic response to HAART, by age and regimen class. AIDS. 2010;24(16):2469–2479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sabin CA, Smith CJ, Delpech Vet al. The associations between age and the development of laboratory abnormalities and treatment discontinuation for reasons other than virological failure in the first year of highly active antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2009;10(1):35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Cahn Pet al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2010 recommendations of the International AIDS Society—USA panel. JAMA. 2010;304(3):321–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Onen NF, Overton ET, Seyfried Wet al. Aging and HIV infection: a comparison between older HIV-infected persons and the general population. HIV Clin Trials. 2010;11(2):100–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goulet JL, Fultz SL, Rimland Det al. Do patterns of comorbidity vary by HIV status, age, and HIV severity? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(12):1593–1601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adih WK, Selik RM, Xiaohong H. Trends in diseases reported on US death certificates that mentioned HIV infection, 1996–2006. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic). 2011;10(1):5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Egger M, et al. Aging and non-HIV associated co-morbidity in HIV+ persons: the SHCS. Abstract 792 presented at: 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston, MA; February 27 to March 3, 2011.

- 43.Young B, Dao CN, Buchacz K, Baker R, Brooks JT. Increased rates of bone fracture among HIV-infected persons in the HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS) compared with the US general population, 2000–2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(8):1061–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sackoff JE, Hanna DB, Pfeiffer MR, Torian LV. Causes of death among persons with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: New York City: Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(6):397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martínez E, Milinkovic A, Buira Eet al. Incidence and causes of death in HIV-infected persons receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy compared with estimates for the general population of similar age and from the same geographical area. HIV Med. 2007;8(4):251–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palella FJ, Jr, Baker RK, Moorman ACet al. Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(1):27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smit C, Geskus R, Walker Set al. Effective therapy has altered the spectrum of cause-specific mortality following HIV seroconversion. AIDS. 2006;20(5):741–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deeks SG. Immune dysfunction, inflammation, and accelerated aging in patients on antiretroviral therapy. Top HIV Med. 2009;17(4):118–123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ho JE, Deeks SG, Hecht FMet al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy at higher nadir CD4(+) T-cell counts is associated with reduced arterial stiffness in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2010;24(12):1897–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferry T, Raffi F, Collin-Filleul Fet al. Uncontrolled viral replication as a risk factor for non-AIDS severe clinical events in HIV-infected patients on long-term antiretroviral therapy: APROCO/COPILOTE (ANRS CO8) Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic. 2009;51(4):407–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DallaPiazza M, Amorosa VK, Localio R, Kostman JR, Lo Re V. Prevalence and risk factors for significant liver fibrosis among HIV-monoinfected patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wand H, Calmy A, Carey DLet al. Metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus after initiation of antiretroviral therapy in HIV infection. AIDS. 2007;21(18):2445–2453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sobieszczyk ME, Hoover DR, Anastos Ket al. Prevalence and predictors of metabolic syndrome among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in the Women's Interagency HIV Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;48(3):272–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hsue PY, Hunt PW, Schnell Aet al. Role of viral replication, antiretroviral therapy, and immunodeficiency in HIV-associated atherosclerosis. AIDS. 2009;23(9):1059–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goulet JL, Fultz SL, McGinnis KA, Justice AC. Relative prevalence of comorbidities and treatment contraindications in HIV-mono-infected and HIV/HCV-co-infected veterans. AIDS. 2005;19(Suppl 3):S99–S105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deeks SG, Phillips AN. HIV infection, antiretroviral treatment, ageing, and non-AIDS related morbidity. BMJ. 2009;338:a3172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaplan RC, Kingsley LA, Sharrett ARet al. Ten-year predicted coronary heart disease risk in HIV-infected men and women. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(8):1074–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Triant VA, Meigs JB, Grinspoon SK. Association of C-reactive protein and HIV infection with acute myocardial infarction. J Acquir Immune Defic. 2009;51(3):268–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.El-Sadr WM, Grund B, Neuhaus Jet al. Risk for opportunistic disease and death after reinitiating continuous antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV previously receiving episodic therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):289–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Triant VA, Josephson F, Rochester CGet al. Adverse outcome analyses of observational data: assessing cardiovascular risk in HIV disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(3):408–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Friis-Møller N, Reiss P, Sabin CAet al. Class of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(17):1723–1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. D:A:D Study Group, Sabin CA, Worm SW, Weber R, et al. Use of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients enrolled in the D:A:D study: a multi-cohort collaboration. Lancet. 2008;371(9622):1417–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Lichtenstein KA, Armon C, Buchacz Ket al. Low CD4(+) T cell count is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease events in the HIV Outpatient Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(4):435–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Niaura R, Shadel WG, Morrow K, Tashima K, Flanigan T, Abrams DB. Human immunodeficiency virus infection, AIDS, and smoking cessation: the time is now. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(3):808–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report—United States, 2011, Jan 14. Report No. 1545–8636 (electronic) 0892-3787 (linking). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/other/su6001.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2012.

- 66.Lloyd-Richardson EE, Stanton CA, Papandonatos GDet al. Motivation and patch treatment for HIV+ smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2009;104(11):1891–1900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vidrine DJ, Marks RM, Arduino RC, Gritz ER. Efficacy of cell phone–delivered smoking cessation counseling for persons living with HIV/AIDS: 3-month outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(1):106–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tedaldi EM, Brooks JT, Weidle PJet al. Increased body mass index does not alter response to initial highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1–infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(1):35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Keithley JK, Duloy AM, Swanson B, Zeller JM. HIV infection and obesity: a review of the evidence. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20(4):260–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Crum-Cianflone N, Tejidor R, Medina S, Barahona I, Ganesan A. Obesity among patients with HIV: the latest epidemic. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(12):925–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arnsten JH, Freeman R, Howard AA, Floris-Moore M, Lo YT, Klein RS. Decreased bone mineral density and increased fracture risk in aging men with or at risk for HIV infection. AIDS. 2007;21(5):617–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Triant VA, Brown TT, Lee H, Grinspoon SK. Fracture prevalence among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected versus non–HIV-infected patients in a large US healthcare system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(9):3499–3504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sharma A, Flom PL, Weedon J, Klein RS. Prospective study of bone mineral density changes in aging men with or at risk for HIV infection. AIDS. 2010;24(15):2337–2345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Overton ET, Mondy K, Bush TJ, et al. Factors associated with low bone mineral density (BMD) in a large cohort of HIV-infected U.S. adults—baseline results from the SUN study. Poster presented at: 14th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; February 26, 2007; Los Angeles, CA.

- 75.Womack JA, Goulet JL, Gibert Cet al. Increased risk of fragility fractures among HIV infected compared to uninfected male veterans. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(2):e17217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McComsey GA, Tebas P, Shane Eet al. Bone disease in HIV infection: a practical review and recommendations for HIV care providers. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(8):937–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.World Health Organization WHO Global Report on Falls Prevention in Older Age. 2007. Available at: http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Falls_prevention7March.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2012

- 78.Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Gail MHet al. Cancer burden in the HIV-infected population in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Crum-Cianflone N, Huppler Hullisiek K, Marconi V. Trends in the incidence of cancers among HIV-infected persons and the impact of antiretroviral therapy: a 20-year cohort study. AIDS. 2009;23(1):41–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Silverberg MJ, Chao C, Leyden WAet al. HIV infection and the risk of cancers with and without a known infectious cause. AIDS. 2009;23(17):2337–2345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Patel P, Hanson DL, Sullivan PSet al. Incidence of types of cancer among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population in the United States, 1992–2003. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(10):728–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shiels MS, Cole SR, Kirk GD, Poole C. A meta-analysis of the incidence of non-AIDS cancers in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(5):611–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Engels EA. Age at cancer diagnosis among persons with AIDS in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(7):452–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Desquilbet L, Jacobson LP, Fried LPet al. HIV-1 infection is associated with an earlier occurrence of a phenotype related to frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(11):1279–1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Desquilbet L, Margolick JB, Fried LPet al. Relationship between a frailty-related phenotype and progressive deterioration of the immune system in HIV-infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic. 2009;50(3):299–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oursler KK, Goulet JL, Crystal Set al. Association of age and comorbidity with physical function in HIV-infected and uninfected patients: results from the veterans aging cohort study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(1):13–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Onen NF, Agbebi A, Shacham E, Stamm KE, Onen AR, Overton T. Frailty among HIV-infected persons in an urban outpatient care setting. J Infect. 2009;59(5):346–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Justice AC, McGinnis KA, Atkinson JHet al. Psychiatric and neurocognitive disorders among HIV-positive and negative veterans in care: Veterans Aging Cohort Five-Site Study. AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl 1):S49–S59 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pence BW, O'Donnell JK, Gaynes BN. Falling through the cracks: the gaps between depression prevalence, diagnosis, treatment, and response in HIV care. AIDS. 2012;26(5):656–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; 1999. Available at: http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/access/NNBBHS.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cohen RA, Boland R, Paul Ret al. Neurocognitive performance enhanced by highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected women. AIDS. 2001;15(3):341–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Harezlak J, Buchthal S, Taylor Met al. Persistence of HIV-associated cognitive impairment, inflammation, and neuronal injury in era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. AIDS. 2011;25(5):625–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Robertson KR, Smurzynski M, Parsons TDet al. The prevalence and incidence of neurocognitive impairment in the HAART era. AIDS. 2007;21(14):1915–1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Horberg MA, Silverberg MJ, Hurley LBet al. Effects of depression and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use on adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy and on clinical outcomes in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(3):384–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Althoff KN, Gange SJ, Klein MBet al. Late presentation for human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(11):1512–1520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Martin J, Volberding P. HIV and premature aging: a field still in its infancy. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(7):477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Effros RB, Fletcher CV, Gebo Ket al. Workshop on HIV infection and aging: what is known and future research directions. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(4):542–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cao W, Jamieson BD, Hultin LE, Hultin PM, Effros RB, Detels R. Premature aging of T cells is associated with faster HIV-1 disease progression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(2):137–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TWet al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12(12):1365–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Appay V, Almeida JR, Sauce D, Autran B, Papagno L. Accelerated immune senescence and HIV-1 infection. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42(5):432–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rickabaugh TM, Kilpatrick RD, Hultin LEet al. The dual impact of HIV-1 infection and aging on naive CD4(+) T-cells: additive and distinct patterns of impairment. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(1):e16459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kaplan RC, Sinclair E, Landay ALet al. T cell activation and senescence predict subclinical carotid artery disease in HIV-infected women. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(4):452–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Horberg MA, Aberg JA, Cheever LW, Renner P, Kaleba EO, Asch SM. Development of national and multiagency HIV care quality measures. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(6):732–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Aberg JA, Kaplan JE, Libman Het al. Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus: 2009 update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(5):651–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hessol NA, Kalinowski A, Benning Let al. Mortality among participants in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study and the Women's Interagency HIV Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):287–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Justice AC, Zingmond DS, Gordon KSet al. Drug toxicity, HIV progression, or comorbidity of aging: does tipranavir use increase the risk of intracranial hemorrhage? Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(9):1226–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nelson MR, Katlama C, Montaner JSet al. The safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for the treatment of HIV infection in adults: the first 4 years. AIDS. 2007;21(10):1273–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bowman L, Carlstedt BC, Hancock EF, Black CD. Adverse drug reaction (ADR) occurrence and evaluation in elderly inpatients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 1996;5(1):9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Egger T, Dormann H, Ahne Get al. Identification of adverse drug reactions in geriatric inpatients using a computerised drug database. Drugs Aging. 2003;20(10):769–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Justice AC. Prioritizing primary care in HIV: comorbidity, toxicity, and demography. Top HIV Med. 2006;14(5):159–163 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Izzedine H, Launay-Vacher V, Deray G. Renal tubular transporters and antiviral drugs: an update. AIDS. 2005;19(5):455–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Incorporating HIV prevention into the medical care of persons living with HIV. Recommendations of CDC, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-12):1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Buchacz K, Baker RK, Moorman ACet al. Rates of hospitalizations and associated diagnoses in a large multisite cohort of HIV patients in the United States, 1994–2005. AIDS. 2008;22(11):1345–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]