Abstract

The photoluminescence behavior of CdS quantum dots in initial growth stage was studied in connection with an annealing process. Compared to the as-synthesized CdS quantum dots (quantum efficiency ≅ 1%), the heat-treated sample showed enhanced luminescence properties (quantum efficiency ≅ 29%) with a narrow band-edge emission. The simple annealing process diminished the accumulated defect states within the nanoparticles and thereby reduced the nonradiative recombination, which was confirmed by diffraction, absorption, and time-resolved photoluminescence. Consequently, the highly luminescent and defect-free nanoparticles were obtained by a facile and straightforward process.

Keywords: CdS quantum dot, photoluminescence, quantum efficiency, local strain, relaxation

Background

Due to the benefits of their size-tunable physical properties [1-3], nanoscale semiconductor materials have promising future applications, including the optoelectronic devices such as light-emitting diodes [4-8] and next-generation quantum dot solar cells [9-14]. Moreover, nanoscale semiconductors functionalized with biomolecules are used as molecular fluorescent probes in biological applications [15].

In recent years, there has been a rapid development of the growth techniques for quantum dots with high crystallinity and narrow size distribution [16-18]. The hot-injection techniques allow the affordable growth of a wide range of nanoscale materials with high quality [19-21]. On the other hand, low-temperature synthesis has not been actively studied yet. Low-temperature synthesis has higher potential than hot-injection techniques because the process is relatively simple and nontoxic [22]. However, the size distribution and the crystallinity of nanoparticles are generally poor because of low synthetic temperature and surface defects [23]. Recently, several papers have introduced advanced low-temperature synthesis and colloidal growth that can yield quantum dots with a sufficiently narrow size distribution [24-27].

In this regard, introducing a facile annealing process has great potential for enhancing the quantum efficiency and tuning the size of nanocrystals. However, systematic analysis of the initial growth stage of the nanoparticles has rarely been studied. In this work, a simple aqueous system and straightforward annealing process were applied to the preparation of highly luminescent CdS quantum dots. The appropriate annealing condition was well correlated with the quantum dot size, local strain (crystallinity), and radiative/nonradiative recombination rates.

Methods

The CdS quantum dots were synthesized by using a combination of the reverse-micelle method and post-growth annealing process. Cadmium chloride (CdCl2, 0.182 g) and sodium sulfide (Na2S, 0.036 g) were separately dissolved in distilled water (15 ml) and stirred to achieve their complete dissolution. Linoleic acid ((C17H31)COOH, 2.4 ml) and sodium linoleate ((C17H31)COONa, 2 g) were dissolved in ethanol (15 ml) and formed transparent solutions. After the two solutions were mixed and stirred vigorously, the color changed from transparent to opaque white, implying the formation of a microemulsion consisting of cadmium linoleate. After the addition of sodium sulfide, the color changed from white to greenish yellow. For the annealing process, the autoclave was heated at 100°C for 1 to 24 h. In order to increase the quantum dot size, post-growth annealing was also conducted at 125°C to 225°C with the same annealing time (12 h). The resultant CdS quantum dots were precipitated by using centrifugation and cleaned several times with ethanol. Finally, the CdS quantum dots were dispersed into chloroform (CHCl3, 40 ml), displaying a translucent yellow solution.

The structural properties of the quantum dots, such as crystal size and local strain, were studied using X-ray diffraction (XRD; M18XHF-SRA, MAC Science, Yokohama, Japan) with θ to 2θ curves. To analyze the optical properties, the absorbance was measured using UV/visible spectrometry, and the photoluminescence (PL) data were measured under 360-nm excitation wavelength with a spectrofluorometer (FP-6500, JASCO, Essex, UK). The binding energy of CdS quantum dots was analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; Sigma Probe, Thermo VG Scientific, Logan, UT, USA) using Al Kα radiation (1,486.6 eV). Time-resolved PL was measured by using a picosecond laser system (FLS920P, Edinburgh Instruments Ltd., Livingston, UK), and the nanostructures of the CdS nanoparticles were analyzed by a high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEM-3000 F, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Results and discussion

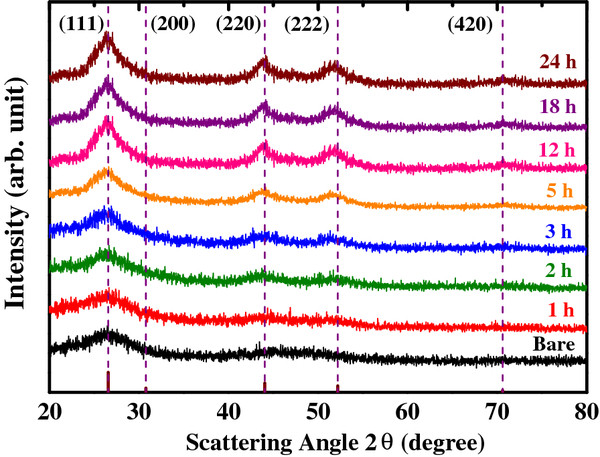

The effects of annealing on the size and crystallinity of CdS nanocrystals were investigated by XRD (Figure 1) with different annealing times. Due to the reaction of residual source during the annealing process plus coarsening behavior of nanoparticles, the average size of CdS quantum dot increases with the annealing time [24]. The diffraction peaks show the zinc-blende phase (JCPDS 75–0581) with no impurity phases. To estimate the nonuniform distribution of local strain (crystallinity) and grain size of CdS quantum dots, four diffraction peaks were fitted with the scattering vector using a double-peak Lorentzian function, considering the effects of Kα1 and Kα2 [28-31] and the instrumental-broadening effect. Before the post-growth annealing process, the size of CdS quantum dots was estimated to be approximately 2.3 nm, which gradually grew to approximately 3.7 nm with increased annealing time (in the following Figure 6). As the annealing time increases, the local strain of CdS quantum dots decreases, suggesting that defects accumulated in the CdS quantum dots during the nucleation stage are relaxed by annealing.

Figure 1.

X-ray diffraction of CdS quantum dots with different annealing times at 100°C.

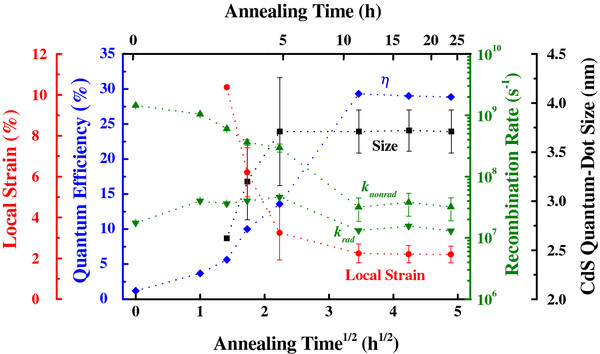

Figure 6.

The correlation between local strain, quantum efficiency, recombination rate, and quantum-dot size as a function of annealing time at 100°C.

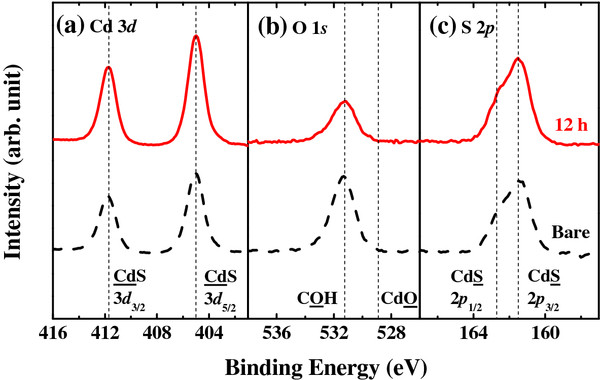

The change in the surface states of CdS quantum dots was examined by XPS (Figure 2). The XPS data of the O 1 s level display the chemical bonding of carboxyl acid, and the peak position of the Cd 3d level is not shifted after annealing. The dotted peak positions denote literature values [32-34]. If the sample becomes oxidized after heat treatment, the oxygen and cadmium peaks will display changes in the chemical bonding to cadmium sulfate [33-35]. This result revealed that the surface of the CdS quantum dots was not changed despite the heat treatment, which means that the linoleate surfactant is still bound to the nanocrystal surface after the 100°C annealing [26].

Figure 2.

XPS spectra. (a) Cd 3d, (b) O 1s, and (c) S 2p with bare and 12-h-annealed samples at 100°C.

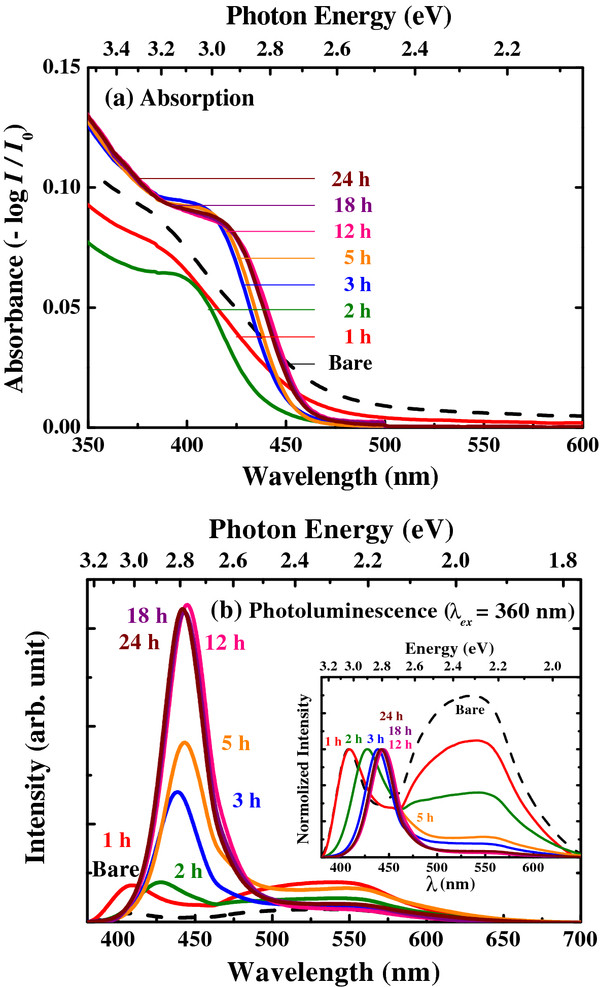

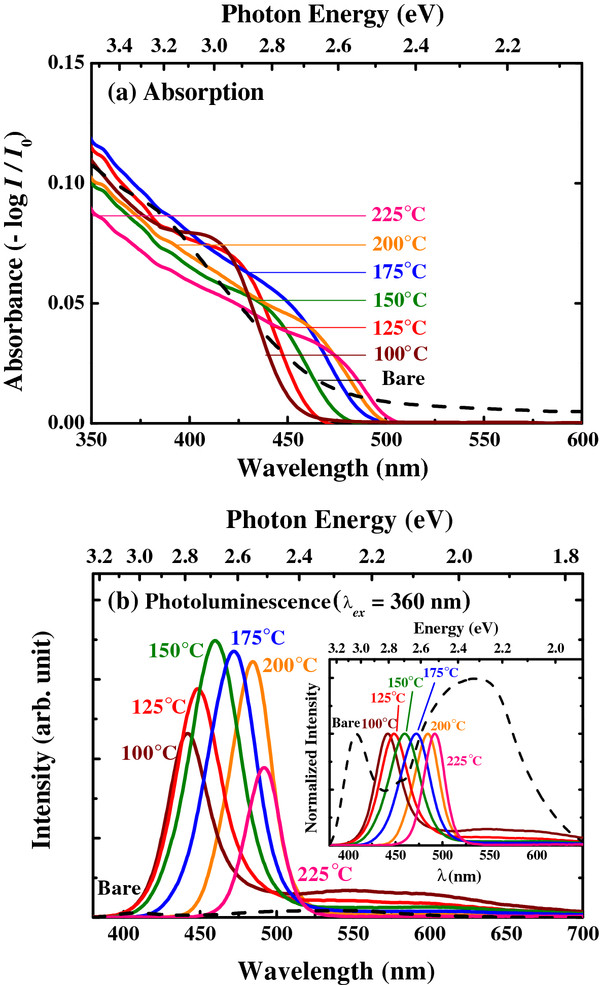

Figure 3 shows several absorbance and PL spectra after different annealing times for the CdS nanoparticles. As the annealing time increases, the absorbance spectra exhibit a red shift relative to the bare sample (Figure 3a). The band-edge emission also shifts to higher wavelength because of the increase of quantum dot size during the annealing process (Figure 3b). The exciton peak becomes clear after 5 h of annealing, indicating improved crystallinity and size dispersity. It was observed that the absorbance intensity below the bandgap energy (Eg) decreased with increasing annealing time, which suggests that the trap-state reduction has occurred in the CdS quantum dots [25]. For the bare sample (quantum efficiency ≅ 1%), broad emission ranging from 450 to 650 nm is dominant (Figure 3b), which originates from the trap-state emission [27,36]. In contrast, the CdS quantum dots annealed for 12 h exhibit strong and narrow band-edge emission at 440 nm (quantum efficiency ≅ 29%). These phenomena also strongly suggest that simple annealing at 100°C reduces the trap states in the CdS nanoparticles.

Figure 3.

Effects of annealing time at 100°C. (a) Absorbance and (b) photoluminescence spectra of CdS nanoparticles as a function of annealing time at 100°C. The inset shows a normalized PL spectra.

To control the radius of the nanoparticles, post-growth annealing process was further examined by varying the annealing temperature (125°C to 225°C). As shown in Figure 4a, the absorbance spectra show a red shift relative to the bare sample, confirming increased nanoparticle size with high annealing temperature. In addition, the wavelength of the band-edge emission was controlled from approximately 440 to approximately 490 nm by simply changing the annealing temperature, as shown in Figure 4b.

Figure 4.

Effects of annealing temperature for 12 h. (a) Absorbance and (b) photoluminescence spectra of CdS nanoparticles as a function of annealing temperature for 12 h. The inset shows normalized PL spectra.

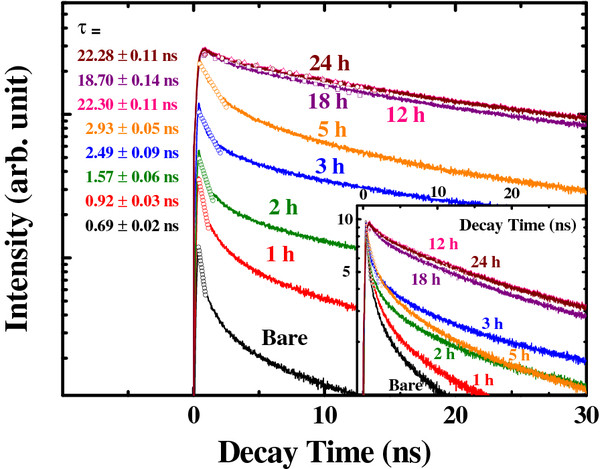

Time-resolved PL measurements were performed to determine the carrier dynamics of CdS quantum dots, as shown in Figure 5[37,38]. The bare sample exhibits fast initial relaxation. In contrast, the initial behavior of the post-annealed samples exhibits long life decay behavior. Even though the decay curves in Figure 5 do not show single-exponential behavior, the decay curves were fitted assuming single exponential in the initial stage because the initial decay occupies a large fraction of total recombination. The samples annealed over 12 h show nearly single-exponential decay, which indicates high crystallinity and the absence of defect-related decay channels [39,40]. This is consistent with the reduction of defect peak (approximately 550 nm) in Figure 3b after 12-h annealing. The quantum efficiency (η) is the ratio of radiative recombination to the total recombination as [41]:

Figure 5.

Time-resolved PL data as a function of annealing time at 100°C. The inset shows normalized data.

| (1) |

where ktotalkradknonrad, and τ are the total, radiative, nonradiative recombination rates, and decay time (krad + knonrad)−1, respectively. The quantum efficiency of colloidal CdS samples was estimated by comparing with the emission of Rhodamine 6G in ethanol (quantum efficiency of approximately 95% for an excitation wavelength of 488 nm) [42]. Then, each decay time constant was obtained using the total recombination rates from the decay curves (Figure 5) and quantum efficiency.

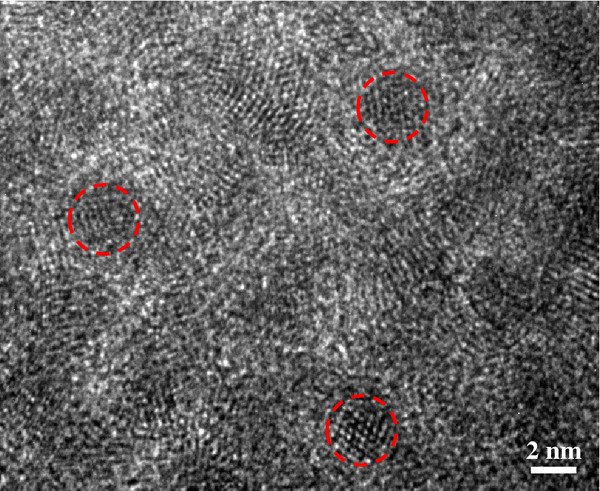

The overall properties of CdS nanoparticles were summarized in Figure 6. It is clear that the emission decay for the bare CdS is dominated by nonradiative decay, which is mediated by high-density trap states in the nanoparticles. However, the facile annealing reduces the local strain and nonradiative recombination center and thereby exhibits longer carrier lifetime and higher quantum efficiency, consistent with the TEM data of Figure 7. In this way, we straightforwardly synthesized highly luminescent CdS nanoparticles, from 1% to 29% in quantum efficiency.

Figure 7.

TEM image of the 12-h-annealed CdS quantum dots at 100°C (approximately 3.7 nm in diameter).

Conclusions

The luminescence properties of CdS quantum dots in the initial growth stage were examined in connection with a simple annealing process. Both the accumulated defect states and nonradiative recombination rates were reduced, and these correlations were confirmed systematically by diffraction, absorption, and time-resolved photoluminescence. Consequently, the highly luminescent (quantum efficiency of 29% from the initial 1%) and defect-free nanoparticles were obtained by a facile annealing process.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JIK and JK drafted and revised the manuscript. JL carried out the synthetic experiments and characterizations. DRJ, HK, HC, SL, SB, and SK participated in the scientific flow. BP conceived of the study and participated in its design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jae Ik Kim, Email: jaeikkim@snu.ac.kr.

Jongmin Kim, Email: rlawhd12@snu.ac.kr.

Junhee Lee, Email: silvergalchi@snu.ac.kr.

Dae-Ryong Jung, Email: hapum007@snu.ac.kr.

Hoechang Kim, Email: hoechang@snu.ac.kr.

Hongsik Choi, Email: rookies1@snu.ac.kr.

Sungjun Lee, Email: sjun22@snu.ac.kr.

Sujin Byun, Email: sence1217@snu.ac.kr.

Suji Kang, Email: dreamcity88@snu.ac.kr.

Byungwoo Park, Email: byungwoo@snu.ac.kr.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea through the World Class University (WCU, R31-2008-000-10075-0) and the Korean government (MEST:NRF, 2010–0029065).

References

- Scholes GD, Rumbles G. Excitons in nanoscale systems. Nat Mater. 2006;5:683–696. doi: 10.1038/nmat1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly KL, Coronado E, Zhao LL, Schatz GC. The optical properties of metal nanoparticles: the influence of size, shape, and dielectric environment. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:668–677. [Google Scholar]

- Trindade T, O’Brien P, Pickett NL. Nanocrystalline semiconductors: synthesis, properties, and perspectives. Chem Mater. 2001;13:3843–3858. doi: 10.1021/cm000843p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang ZM, Liang B, Salamo GJ, Shih CK. Direct spectroscopic evidence for the formation of one-dimensional wetting wires during the growth of InGaAs/GaAs quantum dot chains. Nano Lett. 2006;6:1847–1851. doi: 10.1021/nl060271t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlamp MC, Peng X, Alivisatos AP. Improved efficiencies in light emitting diodes made with CdSe(CdS) core/shell type nanocrystals and a semiconducting polymer. J Appl Phys. 1997;82:5837–5842. doi: 10.1063/1.366452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SM, Choi KC, Kim DH, Jeon DY. Localized surface plasmon enhanced cathodoluminescence from Eu3+-doped phosphor near the nanoscaled silver particles. Opt Express. 2011;19:13209–13217. doi: 10.1364/OE.19.013209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Lee S, Reddy VR, Manasreh MO, Weaver BD, Yakes MK, Furrow CS, Kunets VP, Benamara M, Salamo GJ. Photoluminescence plasmonic enhancement in InAs quantum dots coupled to gold nanoparticles. Mat Lett. 2011;65:3605–3608. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2011.08.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Wu J, Wang ZM, Fan D, Guo A, Li S, Yu SQ, Manasreh O, Salamo GJ. InGaAs quantum well grown on high-index surfaces for superluminescent diode applications. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2010;5:1079–1084. doi: 10.1007/s11671-010-9605-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Lee Y. Assembly of CdS quantum dots onto mesoscopic TiO2 films for quantum dot-sensitized solar cell applications. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:045602. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/04/045602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S, Hossain MF, Takahashi T. Fabrication of Grtäzel solar cell with TiO2/CdS bilayered photoelectrode. Thin Solid Films. 2008;517:1284–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.tsf.2008.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Choi H, Nahm C, Moon J, Kim C, Nam S, Jung DR, Park B. The effect of a blocking layer on the photovoltaic performance in CdS quantum-dot-sensitized solar cells. J Power Sources. 2011;196:10526–10531. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2011.08.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L, Li X, Cammarata RC, Friesen C, Sieradzki K. Electrochemical stability of elemental metal nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11722–11726. doi: 10.1021/ja104421t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu MS, Chen HL, Shen CH, Hong LS, Huang BR, Chen KH, Chen LC. Photosensitive gold-nanoparticle-embedded dielectric nanowires. Nat Mater. 2006;5:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nmat1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martí A, Antolín E, Stanley CR, Farmer CD, López N, Díaz P, Cánovas E, Linares PG, Luque A. Production of photocurrent due to intermediate-to-conduction-band transitions: a demonstration of a key operating principle of the intermediate-band solar cell. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;97:247701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.247701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchez M, Morrone M, Gin P, Weiss S, Alivisatos AP. Semiconductor nanocrystals as fluorescent biological labels. Science. 1998;281:2013–2016. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent S, Forge D, Port M, Roch A, Robic C, Vander EL, Muller RN. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, stabilization, vectorization, physicochemical characterizations, and biological applications. Chem Rev. 2008;108:2064–2110. doi: 10.1021/cr068445e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sau TK, Rogach AL. Nonspherical noble metal nanoparticles: colloid-chemical synthesis and morphology control. Adv Mater. 2010;22:1781–1804. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Luan W, Tu ST, Wang ZM. Synthesis of nanocrystals via microreaction with temperature gradient: towards separation of nucleation and growth. Lab Chip. 2008;8:451–455. doi: 10.1039/b715540a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CB, Norris DJ, Bawendi MG. Synthesis and characterization of nearly monodisperse CdE (E = sulfur, selenium, tellurium) semiconductor nanocrystallites. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:8706–8715. doi: 10.1021/ja00072a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Manna L, Yang W, Wickham J, Scher E, Kadavanich A, Alivisatos AP. Shape control of CdSe nanocrystals. Nature. 2000;404:59–61. doi: 10.1038/35003535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyeon T. Chemical synthesis of magnetic nanoparticles. Chem Comm. 2003;9:927–934. doi: 10.1039/b207789b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N, Qi L. Low-temperature synthesis of star-shaped PbS nanocrystals in aqueous solutions of mixed cationic/anionic surfactants. Adv Mater. 2006;18:359–362. doi: 10.1002/adma.200501756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi JW, Yan X, Cui HJ, Zong X, Fu ML, Chen S, Wang L. Low-temperature synthesis of CdS/TiO2 composite photocatalysts: influence of synthetic procedure on photocatalytic activity under visible light. J Mol Catal A. 2012;356:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhuang J, Peng Q, Li Y. A general strategy for nanocrystal synthesis. Nature. 2005;437:121–124. doi: 10.1038/nature03968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon SG, Hyeon T. Formation mechanisms of uniform nanocrystals via hot-injection and heat-up methods. Small. 2011;7:2685–2702. doi: 10.1002/smll.201002022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son D, Jung DR, Kim J, Moon T, Kim C, Park B. Synthesis and photoluminescence of Mn-doped zinc sulfide nanoparticles. Appl Phys Lett. 2007;90:101910. doi: 10.1063/1.2711709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joo J, Na H, Yu T, Yu J, Kim Y, Xu F, Zhang J, Hyeon T. Generalized and facile synthesis of semiconducting metal sulfide nanocrystals. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11100–11105. doi: 10.1021/ja0357902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung DR, Kim J, Park B. Surface-passivation effects on the photoluminescence enhancement in ZnS:Mn nanoparticles by ultraviolet irradiation with oxygen bubbling. Appl Phys Lett. 2010;96:211908. doi: 10.1063/1.3431267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moon T, Hwang S, Jung D, Son D, Kim C, Kim J, Kang M, Park B. Hydroxyl-quenching effects on the photoluminescence properties of SnO2:Eu3+ J Phys Chem C. 2007;111:4164–4167. doi: 10.1021/jp067217l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T, Oh J, Park B. Correlation between strain and dielectric properties in ZrTiO4 thin films. Appl Phys Lett. 2000;76:3043–3045. doi: 10.1063/1.126573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warren BE. X-Ray Diffraction. Dover, New York; 1990. pp. 257–262. [Google Scholar]

- Rengaraj S, Venkataraj S, Jee S, Kim Y, Tai C, Repo E, Koistinen A, Ferancova A, Sillanpää M. Cauliflower-like CdS microspheres composed of nanocrystals and their physicochemical properties. Langmuir. 2011;27:352–358. doi: 10.1021/la1032288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, Li Q, Xi C, Jian Z, Chen Z. Effect of high-temperature treatment in air ambience on the surface composition and structure of CdS. Appl Surf Sci. 1988;32:218–232. doi: 10.1016/0169-4332(88)90082-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu S, Wang Y, Xia W, Muhler M. Thermal stability and reducibility of oxygen-containing functional groups on multiwalled carbon nanotube surfaces: a quantitative high-resolution XPS and TPD/TPR study. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:16869–16878. doi: 10.1021/jp804413a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang E, Jun S, Chung Y, Pu L. Surface treatment to enhance the quantum efficiency of semiconductor nanocrystals. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:4597–4600. doi: 10.1021/jp049475t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders AE, Ghezelbash A, Sood P, Korgel BA. Synthesis of high aspect ratio quantum-size CdS nanorods and their surface-dependent photoluminescence. Langmuir. 2008;24:9043–9049. doi: 10.1021/la800964s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M, Nedeljkovic J, Ellingson RJ, Nozik AJ, Rumbles G. Photoenhancement of luminescence in colloidal CdSe quantum dot solutions. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:11346–11352. doi: 10.1021/jp035598m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Wang ZM, Dorogan VG, Li S, Mazur YI, Salamo GJ. Near infrared broadband emission of In0.35Ga0.65As quantum dots on high index GaAs surfaces. Nanoscale. 2011;3:1485–1488. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00973c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na CW, Han DS, Kim DS, Kang YJ, Lee JY, Park J, Oh DK, Kim KS, Kim D. Photoluminescence of Cd1-xMnxS (x ≤ 0.3) nanowires. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:6699–6704. doi: 10.1021/jp060224p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarma DD, Nag A, Santra PK, Kumar A, Sapra S, Mahadevan P. Origin of the enhanced photoluminescence from semiconductor CdSeS nanocrystals. J Phys Chem Lett. 2010;3:2149–2153. [Google Scholar]

- Jung DR, Son D, Kim J, Kim C, Park B. Highly luminescent surface-passivated ZnS:Mn nanoparticles by a simple one-step synthesis. Appl Phys Lett. 2008;93:163118. doi: 10.1063/1.3007980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M, Georges J. Fluorescence quantum yield of rhodamine 6 G in ethanol as a function of concentration using thermal lens spectrometry. Chem Phys Lett. 1996;260:115–118. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(96)00838-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]