Abstract

Optical trapping and single-molecule fluorescence are two major single-molecule approaches. Their combination has begun to show greater capability to study more complex systems than either method alone, but met many fundamental and technical challenges. We built an instrument that combines base-pair resolution dual-trap optical tweezers with single-molecule fluorescence microscopy. The instrument has complementary design and functionalities compared with similar microscopes previously described. The optical tweezers can be operated in constant force mode for easy data interpretation or in variable force mode for maximum spatiotemporal resolution. The single-molecule fluorescence detection can be implemented in either wide-field or confocal imaging configuration. To demonstrate the capabilities of the new instrument, we imaged a single stretched λ DNA molecule and investigated the dynamics of a DNA hairpin molecule in the presence of fluorophore-labeled complementary oligonucleotide. We simultaneously observed changes in the fluorescence signal and pauses in fast extension hopping of the hairpin due to association and dissociation of individual oligonucleotides. The combined versatile microscopy allows for greater flexibility to study molecular machines or assemblies at a single-molecule level.

INTRODUCTION

Single-molecule approaches have unique advantages over ensemble approaches in studies of molecular machines and assemblies.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 They allow dissection of the complex kinetics and structural heterogeneity and plasticity masked by ensemble averaging in traditional experimental methods. These methods include single-molecule fluorescence, optical tweezers, magnetic tweezers, and atomic force microscopy,7 the first two of which have been widely used and will be the focus of this work.

The fluorescence approaches mainly utilize single-molecule fluorescence localization (SML)8, 9, 10 and Förster resonance energy transfer (smFRET).11 The localization method has been used to track motor movements9, 12 and serves as a basis for various super-resolution optical microscopy.13 Single-molecule FRET has been widely applied to investigate conformational transitions of macromolecules.3 The major advantage of these single-molecule fluorescence methods is their ability to specifically visualize single molecules, in a passive manner. But these methods often rely on structural information of the macromolecule for attaching fluorescent probes.14, 15, 16, 17 Moreover, they suffer from a short measurement range in time (typically 5 ms–120 s) due to fluorophore photobleaching and limited spatial resolution for SML (1–30 nm) and small distance measurement range for smFRET (0.3–10 nm).

Optical tweezers complement both SML and smFRET in their high spatiotemporal resolution and measurement ranges (0.1 ms – over 1 h and 0.3 nm – over 50 μm, respectively) and capability to actively manipulate molecules.18, 19, 20 Nevertheless, optical tweezers can only measure one-dimensional distance changes along the direction of pulling force and cannot visualize single molecules. Thus, using either of the single-molecule approaches, it may be difficult to correlate the conformation state of the motor to its stepwise movement or complex protein folding or DNA condensation to association of partner proteins. A combination of single-molecule fluorescence approaches and optical trapping will expand the capability of single-molecule methods and represent one of the latest developments in single-molecule biophysics.5, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28

A major challenge to combining optical tweezers and single-molecule fluorescence lies in the fact that a fluorophore in the vicinity of the optical trap can only fluoresce for a few seconds before being photobleached. The photobleaching is a two-photon process involving the sequential absorption of a fluorescence excitation and an optical trapping photon.22, 23, 29 To address this problem, fluorescence excitation and optical trapping can be separated spatially5, 24 or temporally.22, 25 The spatial separation method requires a long DNA handle (such as λ DNA) to transmit the optical force to the fluorophore-labeled and surface-immobilized molecule of interest. Using this method, Ha and co-workers have studied the kinetics of the Holliday junction and reptation of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) on the surface of ssDNA binding proteins.5, 24 These studies demonstrate the great potential of the combined single-molecule approach. However, the spatial separation method prevents accurate distance measurement by the optical trap due to compliance of the DNA handle and surface immobilization.30, 31, 32 In principle, the temporal separation method does not suffer from both limitations, but needs to interlace the trapping light and fluorescence excitation light at a high frequency (>30 kHz). Thus at any time, the fluorophore is never exposed in both the trapping and fluorescence excitation light, avoiding the two-photon photobleaching process and enhancing the fluorophore lifetime. This method has been successfully used by Lang and colleagues.21, 22, 23 Like other similar optical trapping studies,33, 34 their work utilized a single optical trap and required attachment of the macromolecule of interest to the sample stage to pull the macromolecule, which limits the spatial resolution of optical tweezers due to stage drift.30 Recently, an important improvement has been made by incorporating single-molecule fluorescence detection into high-resolution optical tweezers with base-pair (bp) resolution.25 This study uses time-shared dual traps to pull the macromolecule, eliminating immobilization of the macromolecule to the stage and greatly increasing the spatial resolution of the optical tweezers. The time-sharing is implemented through an acousto-optic modulator (AOM) and sophisticated feedback circuits to accurately control both deflection and intensity of the trapping light. As a result, a home-made radio-frequency generator is adopted. The technical innovation may be challenging for many laboratories to develop similar instruments.

We developed an instrument with a complementary design that combines high-resolution optical tweezers with single-molecule fluorescence microscopy. The microscope was built based upon an established design of dual-trap high-resolution optical tweezers.32 In addition to the trapping beam, we added a separate probing laser beam for position detection, which enables operation of the tweezers in constant force mode and facilitates combined optical trapping and fluorescence measurements. We incorporated the fluorescence microscopy by interlacing fluorescence excitation and optical trapping at a frequency of 100 kHz. In our design, both optical traps are turned on and off simultaneously, instead of sequentially as in the previous design, which allows for higher interlacing frequency and minimizes bead position fluctuations due to trap switching. Fluorescence from single fluorophores can be detected in either confocal or wide-field imaging format. We evaluated the performance of the instrument by studying the dynamics of a DNA hairpin in both variable and constant force mode. We observed a ∼20% increase in the spatial resolution of the instrument in the variable force mode compared to the constant force mode. Finally, we characterized the effect of a Cy3-labeled complementary oligonucleotide on the dynamics of the same DNA hairpin and imaged a single λ DNA molecule, using our combined optical tweezers and single-molecule fluorescence microscopy. Compared with recent work,25 our design has similar performance, more functionality, and can be used to upgrade the dual-trap optical tweezers for fluorescence detection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA sequences

The DNA hairpin tttgagtcaa cgtctggatc ctgttttcag gatccagacgttgactcttt was chemically synthesized containing a biotin and a thiol modifier at 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The sequence in italic is identical to the previous hairpin sequence 20R55/T4,19 except three thymidines added to both ends as linkers. The sequence of Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide, Cy3-tcaacgtctg, is complementary to the underlined sequence in the stem region of the DNA hairpin. Two DNA handles, one 2260 bp and the other ∼2000 bp, were made by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the same pUC19 DNA plasmid (New England Biolabs, MA) as a template and two different sets of primers labeled at the 5′ end. Two of the four primers contain two digoxigenin molecules (Eurofins MWG Operon, AL), the third primer has biotin, and the fourth one consists of a thiol modifier. As a result, the 2260 bp DNA handle is labeled with two digoxigenin molecules at one end and one thiol group at the other end, while the ∼2000 bp DNA handle is labeled with two digoxigenin molecules at one end and a biotin moiety at the other. If not otherwise specified, all oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. The DNA hairpin and the thiolated DNA handle were crosslinked as previously described.20, 35, 36 The λ DNA was labeled at the cos site through polymerase extension in the presence of biotin-dATP (Roche).

Buffers

The folding and unfolding experiments of the DNA hairpin alone were performed in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (137 mM of NaCl, 2.7 mM of KCl, 8.1 mM of Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM of KH2PO4, pH of 7.4) supplemented with an oxygen scavenging system (OSS): 13 U/ml glucose oxidase (Sigma-Aldrich), 47 U/ml catalase (MP-Biomedicals), and 10 mg/ml glucose. In the presence of the Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide, the combined optical trapping and single-molecule fluorescence detection was carried out in a tris buffer (20 mM tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 100 mM NaCl), supplemented with the OSS and 2 mM Trolox (Sigma-Aldrich),15 as Cy3 appears brighter in this buffer than the PBS buffer. DNA visualization was performed in the same tris buffer and supplements in the presence of 250 nM DNA intercalating dye POPO-3 iodide (Molecular Probes). All experiments were done at room temperature.

Tweezer experiments

The DNA hairpin-handle conjugate was bound to the 880 nm diameter anti-digoxigenin-coated polystyrene bead, caught by one trap, and tethered to a second trapped 900 nm streptavidin-coated polystyrene bead. For simultaneous trapping and fluorescence detection in the presence of the Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide, two DNA handles were used and linked to the DNA hairpin via a streptavidin molecule as described previously.37 Optical traps were calibrated by the power-spectrum density analysis of the bead's Brownian motion, yielding the force constants of the traps. Data were acquired at 20 kHz, mean-filtered to 10 kHz or 5 kHz online, and recorded in a hard disk for further analysis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Instrumentation of the combined optical tweezers and fluorescence microscopy

The microscope is based on a design of high-resolution dual-trap optical tweezers previously described.32 Briefly, the two optical traps are formed by focusing two expanded, orthogonally polarized 1064-nm laser beams (Fig. 1, orange lines) using a water-immersion objective with high IR transmission. The traps hold two beads as force and displacement sensors, whose displacements are detected via back-focal plane interferometry using either the trapping beam or an additional 830-nm probing laser beam.38 The probing beam is required when the tweezers are operated in a constant-force mode31 or when fluorescence is detected in our instrument. The instrument is designed such that different detection schemes can be easily switched from one to the other by adding or removing one filter (F3) in the optical path.

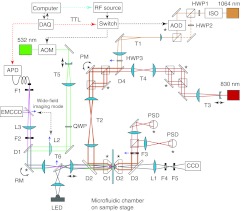

Figure 1.

Instrument layout. The 1064-nm trapping light from a solid-state laser is split into two orthogonally polarized beams, expanded by telescopes T1 and T2 and focused by a water-immersion objective (O1) to form two optical traps. The light intensity in each trap can be controlled jointly by rotating HWP1 and sending all the trapping light through the acousto-optic deflector (AOD) while HWP3 is on. Alternatively, the light intensity in each trap can be controlled independently by removing HWP3 and rotating HWP1 in order to deflect part of the 1064 nm light through HWP2 (dashed orange line). To detect bead positions, the outgoing trapping beams can be collimated by a second objective (O2) and projected to two position-sensitive detectors (PSD). Alternatively, a second 830-nm laser can be used to independently measure the position of each bead. The fluorescence module contains excitation and emission light paths. The excitation beam (green line) from a 532 nm laser is modulated by the acousto-optic modulator (AOM), expanded by telescope T5, and collimated (lens L2 off) or focused (lens L2 on) to the back-focal plane of objective O1 to illuminate the sample in a confocal or wide-field format, respectively. The telescope T6 expands the 532 nm light by twofold and conjugates the rotary mirror (RM) to the back-focal plane of objective O1. The rotary mirror is used to scan the confocal excitation volume in the sample plane. Fluorescence emission (purple line) is spatially filtered by a 100 μm diameter optical fiber and fed to a single photon counting avalanche photodiode (APD). Alternatively, the emission light can be guided to an electron multiplying charged coupled device (EMCCD) with a flip mirror in the case of wide-field illumination. The fluorescence excitation and trapping beams are interlaced through out-of-phase, on-off switching of the AOM and the AOD. A white light LED and a CCD camera are used to visualize the beads in the sample plane. Asterisks indicate the mirrors at positions that are conjugate to the back-focal planes of the two objectives. Acronyms represent the following: D1-D4, dichroic mirrors; F1-F5, filters; QWP, quarter-wave plate; ISO, optical isolator; PM, piezoelectric mirror.

The fluorescence excitation is provided by a 532-nm laser light in either confocal or wide-field format (Fig. 1, green line). To add the fluorescence module, we chose to interlace the trapping and fluorescence excitation lights with an acousto-optic deflector (AOD) and an acousto-optic modulator (AOM), respectively. The two acousto-optic devices are alternatively activated in response to a transistor-transistor logic (TTL) modulation signal (Fig. 2a) switching on and off the trapping and fluorescence excitation lights, in an out-of-phase manner. The frequency of the modulation signal should be as high as possible to minimize position fluctuations of the trapped beads due to trap switching. In our system the modulation frequency is determined by the AOD with an access time of 1.6 μs/mm. The diameter of the incident beam to the AOD is ∼0.8 mm, which allows for a maximum modulation frequency of ∼400 kHz. We chose a modulation frequency of 100 kHz to balance fast switching and quality of light modulation. The fluorescence emission light (Fig. 1, purple line) is collected by either a single-photon counting avalanche photodiode (APD) or an electron multiplying charged coupled device (EMCCD). The APD is also gated by the TTL modulation signal such that photons are only counted during the excitation period.

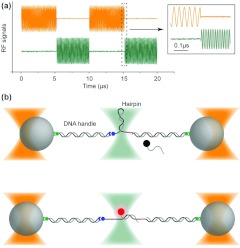

Figure 2.

Interlacing scheme and experimental setup. (a) Interlacing scheme produced by the radio-frequency (RF) electronics for modulating the intensity of the trapping (orange) and fluorescence excitation (green) lasers. A PCI board with a two-channel RF frequency source generates the driving signals for AOD (orange) and AOM (green), with a frequency of 27 and 80 MHz, respectively. Two RF switches turn the AOM and AOD signals on and off at 100 kHz in an out-of-phase scheme, prior to amplification through a dual RF power amplifier. (b) DNA hairpin containing a 20-bp stem is attached to beads via two DNA handles. The hairpin is conjugated to one DNA handle through a disulfide bond and to the other DNA handle through a streptavidin molecule. The resulting construct is tethered to two anti-digoxigenin coated 880 nm beads. The hairpin can be mechanically induced to unfold and refold due to thermal fluctuations. The transitions can be interrupted by hybridization of freely diffusing Cy3-labeled oligonucleotides to the hairpin sequence. The oligonucleotide binding and unbinding events can be monitored by both extension and fluorescence changes, simultaneously.

The construction of an instrument that combines optical tweezers and single-molecule fluorescence microscopy is a time-consuming process because the instrument must be built using many off-the-shelf and custom-made parts.39 In our design the microscope can be built in multiple stages, contains flexible and largely fail-safe configurations for quality control, and has versatile functionalities. The microscope can be operated in a high-resolution variable-force mode,20, 32 in a constant force mode,40 and in a combined optical trapping and fluorescence mode. In the variable force mode a single beam goes through the AOD (AOD beam) and is split with the help of a half-wave plate (HWP3) into two orthogonally polarized beams (Fig. 1, orange solid line with HWP3 on). Switching to the combined optical trapping and fluorescence mode is straightforward and can be achieved by operating the AOD as an on-off light switch. In the constant force mode, a large portion of the AOD beam intensity is transferred through HWP2, by rotating HWP1, making one trap significantly weaker than the other (Fig. 1, orange dashed line with HWP3 off). In this case the AOD is used to independently modulate the intensity of the weak trap and adjust the constant force provided by this trap in the range of interest. Alternatively, the light through HWP2 is blocked and the light intensities of both strong and weak traps are adjusted by AOD and HWP3, which allows the instrument to operate in a constant force mode with single-molecule fluorescence detection. Finally, fluorescence detection can be chosen between a confocal and a wide-field imaging format. Here, wide-field fluorescence imaging is implemented with interlaced optical trapping to minimize fluorophore photobleaching.

The combined instrument has 1 bp spatial resolution

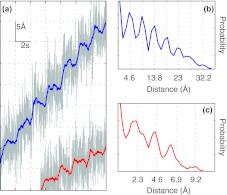

The on-off switching of the trapping light can introduce extra noise to optical tweezers due to the accompanying bead oscillations. To minimize this noise, we chose the highest practical modulation frequency of 100 kHz for both acousto-optic devices. To test the resolution of the instrument under this condition, we pulled a single ∼4 kb DNA molecule using two ∼900-nm polystyrene beads to a tension of ∼10 pN. Subsequently, the two traps were separated in a stepwise manner with a step size of 2 or 1 bp every 2 s and the total displacement of the beads from their respective trap centers was recorded (Fig. 3). When the time-dependent traces are mean-filtered to 100 Hz, stepwise increases are discernable from the trace with 2-bp, but not 1-bp increases in the trap separation. However, when further filtered to 2 Hz, both traces reveal the expected stepwise increases, indicating that our instrument can resolve 1 bp extension changes in a 2-Hz bandwidth. Such discrete changes can be more clearly seen as uniformly spaced peaks in the corresponding pairwise distance distributions calculated from the traces filtered to 2 Hz. The average spacing between successive peaks gives the measured step sizes of 4.6 ± 0.5 Å (Fig. 3b) and 2.3 ± 0.5 Å (Fig. 3c), respectively. These measured step sizes in the total displacement are smaller than the corresponding step sizes in the trap separation (6.8 Å and 3.4 Å), which are consistent with predictions based upon the mechanical compliance of the DNA tether.31 Similar base-pair spatial resolution is retained in higher pulling force ranges up to 20 pN. Taken together, our results indicate that no significant extra noise is introduced by modulating both traps with 100 kHz frequency and the optical tweezers are able to reach 1 base-pair spatial resolution as previously reported for high-resolution optical tweezers.20, 25, 31, 32

Figure 3.

Resolution measurements under modulation of the intensity of the trap at 100 kHz. (a) Total displacements of two ∼900 nm beads tethered by a 4031 bp dsDNA as the traps were separated by 3.4 Å (lower trace) and 6.8 Å (upper trace) every 2 s at a tension of ∼10 pN. Data were mean-filtered to 100 Hz (gray line) and to 2 Hz (blue and red lines), respectively. (b) Pairwise distance distribution of the blue trace in (a) confirming the presence of steps with a measured step size of 4.6 Å. (c) Pairwise distance distributions of the red trace in (a) confirming the presence of steps with a measured step size of 2.3 Å. The measured step sizes (4.6 Å in (b) and 2.3 Å in (c)) are expected to be smaller than the corresponding mirror step sizes due to the compliance of the DNA molecule.40

Test of the passive force clamp

The above resolution test was performed under a variable force condition, in which the two optical traps had the same stiffness. Under this experimental condition the tension of the DNA tether varies linearly with changes in its extension at a fixed trap separation. In the variable force mode a series of elastic corrections are required as one tries to derive structural or conformational changes of the macromolecule from the measured extension changes, which may complicate data analysis. Therefore, it is advantageous to carry out the single-molecule experiment in the presence of a constant force, or a force clamp. Block and co-workers have developed a passive force clamp using the anharmonic region near the edge of the trapping potential where the local trap stiffness is approximately zero for small displacements.31, 40 This design bypasses the widely used active feedback and increases the spatiotemporal resolution of optical tweezers operated in constant-force mode. To form the clamp, one trap is made significantly weaker than the other (Fig. 4a). The strong trap measures the force as the bead remains in the linear region, while the weak trap provides the constant force since the bead in this trap is pulled to the edge of the trap where the local trap stiffness is zero.

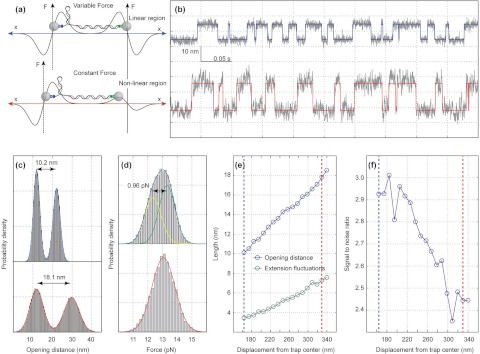

Figure 4.

Comparison of constant force and variable force mode. (a) Schematic of the force-displacement curves (F-x) for two trapped beads under variable and constant force mode. In the variable force mode both traps have similar intensities and the beads are located near the center of each trap. The constant force mode can be implemented by making one trap significantly weaker than the other and pulling the bead in the weak trap to the maximum of the F-x curve where the local trap stiffness approaches zero. (b) Time-dependent extension of the hairpin recorded in variable (top) and constant (bottom) force mode showing reversible hairpin unfolding and refolding induced by force. The corresponding idealized state transition traces are determined by the hidden-Markov method (HMM) and indicated by the colored traces. Data were mean-filtered to and shown at 5 kHz (gray lines). (c) Probability density distribution of the extension for the hairpin at the variable force mode (blue trace) and the constant force mode (red trace). At the constant force mode the expected length change (∼18 nm) of the hairpin is recovered. At the variable force mode the measured extension reduces to ∼10.2 nm due to the compliance of the DNA handle but the SNR is increased by ∼20%. (d) Probability density distribution of the force at the harmonic (blue trace) and constant force (red trace) regions of the trap. At the constant force region the force histogram can be fit well with a single Gaussian indicating that the force remains constant despite the oscillations in the extension. At the harmonic region the force oscillates with the oscillations in the extension and the corresponding histogram can be fit well with two Gaussians (yellow and green trace). (e) Opening distance (blue line) and extension fluctuations (green line) of the hairpin as the bead is moving from the harmonic region of the trap (blue dotted line), towards the constant force region (red dotted line), near the edge of the trap. (f) The SNR as the bead is moving from the harmonic region of the trap (blue dotted line), towards the constant force region (red dotted line). The SNR is increased by ∼20% when the same measurements are performed in the harmonic instead of the constant force region.

To test the force clamp, we studied the folding and unfolding dynamics of a DNA hairpin containing a stem of 20 bp and a thymidine tetraloop.19 The DNA hairpin was attached directly to a ∼900 nm diameter streptavidin coated bead and indirectly to 880 nm diameter anti-digoxigenin-coated bead via a 2.26 kb DNA handle (Fig. 4a). Under this experimental condition, the constant force region locates ∼330 nm away from the center of the weak trap and its position is independent of the magnitude of the constant force (Figs. 4e, 4f, red dotted line). The DNA hairpin undergoes reversible unfolding and refolding transitions in the force range of 12.5–13.7 pN in a two-state manner. The two states equilibrate at a tension of ∼13.1 pN and can be well described with a two-state hidden Markov model (Fig. 4b, red trace). The force fluctuations follow a single Gaussian distribution in the constant force region, and are due to the Brownian motion of the bead in the strong trap (Fig. 4d, red trace). The corresponding extension histogram has two peaks consistent with the folded and unfolded states and can be well fit with a double-Gaussian function (Fig. 4c, red trace). The distance of the two peaks gives the measured extension change, and the ratio of the distance over the sum of the standard deviation of the two Gaussian peaks represents the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). In the constant force region the distance between the two peaks gives an extension change of 18.1 ± 0.9 nm. The observed extension change of the hairpin in the constant force region is similar to previous measurements of 17.9 nm within experimental error.19 Taken together our results indicate the successful implementation of a passive force clamp in our instrument.

Comparison of constant force and variable force mode

In the variable force mode where both traps have the same stiffness the measured extension decreases to 10.2 nm due to the compliance of the DNA handle (Figs. 4b, 4c, blue trace). However, despite the decrease in the value of the measured extension, we noticed an increase in the SNR in the variable force mode compared to the same measurements in the constant force mode (Fig. 4f, blue and red dotted line). To show how the SNR depends upon the local trap stiffness, we measured the hairpin dynamics as the position of the bead in the weak trap is decreased from the constant force region ∼360 nm to the harmonic region ∼160 nm away from the weak trap center. Accordingly, we fixed the stiffness of the strong trap to be 0.28 pN/nm and pulled the bead in the weak trap to the edge of the trapping potential in the constant force region. Subsequently, we decreased the distance between the two traps in a stepwise manner while increasing the power of the weak trap at each step so that the hairpin continues to transit between its folded and unfolded states with an unfolding probability in the range of 0.4–0.6. In this way we measure the extension change and the extension fluctuation as the local trap stiffness in the weak trap ranges from 0 to 0.28 pN/nm.

As expected the measured extension change is reduced as we approach the harmonic region of the trap since the stiffness of the DNA handle (kDNA) becomes increasingly important (Fig. 4e, blue line). Interestingly, the extension fluctuations are also reduced resulting in a higher SNR (Fig. 4e, green line). As the bead in the weak trap is pulled away from the constant force region, the motion of the two beads becomes more correlated. Within the context of differential detection, this correlated motion of the beads can be used to improve the resolving power of the instrument.32 Accordingly, for two beads of approximately equal size, the SNR increases as we approach to the harmonic region and reaches its maximum value when the stiffness of the two traps equilibrates (Fig. 4f). Quantitatively, for two beads of equal size with a drag coefficient γ and hydrodynamic coupling Γ, the SNR at a given bandwidth B is given by

| (1) |

where Δl is the contour length change of the hairpin, gm is the extension to the contour length ratio of the hairpin, and k1, k2 are the force constants of the strong and weak trap, respectively.32 By taking the k2 → 0 limit for the constant force mode and setting k2 = k1 for the variable force mode we obtain a ∼19% improvement in the SNR of the variable over the constant force mode, in good agreement with the experimentally determined value of ∼20%. As the bead is pulled away from the constant force region towards the center of the trap, the force is no longer constant and starts to hop as the hairpin transits between its folded and unfolded states (Fig. 4d, blue trace). In addition, the transitions become faster, which is indicated by an increase in the transition rate from 42 s−1 in the constant force mode to 78 s−1 in the variable force mode, at an opening probability of ∼0.5 (Fig. 4b). This result confirms a slightly lower apparent activation barrier for folding and unfolding transitions observed in the variable force mode than in the constant force mode.20

Simultaneous optical trapping and single-molecule fluorescence detection

To demonstrate simultaneous optical trapping and fluorescence detection, we measured the dynamics of the DNA hairpin in the presence of a Cy3-labeled, 10-nucleotide oligonucleotide complementary to one of the strands in the stem region of the hairpin. Hybridization of the oligonucleotide to the hairpin strand is expected to antagonize folding of the hairpin and produce signals measured by both fluorescence and optical tweezers. To facilitate fluorescence measurements the optical tweezer part of the instrument was set at the variable force mode and we position the hairpin at the middle point of the two beads via two DNA handles (Fig. 2b). The folding and unfolding transitions of the hairpin equilibrate at an average force of ∼12.5 pN and a rate of ∼100 s−1. The measured average extension change under these conditions is 7.5 nm (Figs. 5a, blue trace and 5b), compared to 10.2 nm extension change measured using one DNA handle (Fig. 4c), due to the greater compliance of the two DNA handles.37, 40 In the presence of low concentrations of oligonucleotide ranging from 8 to 20 nM, we observed pauses in the fast hairpin transitions. In each pause the average extension is close to that of the unfolded hairpin, indicating that the hairpin is clamped in its open state by the oligonucleotide. The duration of the pauses is stochastic, ranging from ∼1 to 90 s (Fig. 6, blue bars and line). Its distribution can be fit with a single exponential function, yielding an average pause duration of 10.7 s that is three orders of magnitude longer than the average lifetime of the hairpin (∼10 ms) in the absence of the oligonucleotide.

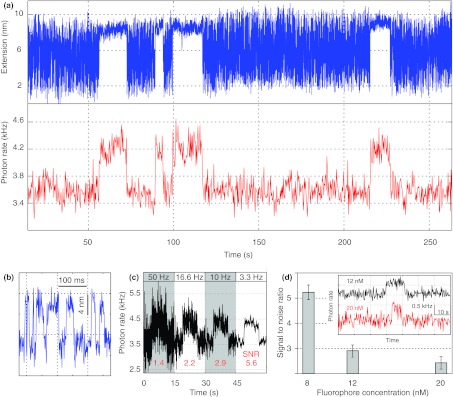

Figure 5.

Combined fluorescence and extension measurements of a DNA hairpin under tension in the presence of fluorophore-labeled oligonucleotide. (a) Time-dependent extension of the hairpin as the hairpin transits among its folded, unfolded, and oligonucleotide-bound states under a tension of ∼12.5 pN and in the presence of 8 nM Cy3-labeled oligonucleotides (blue trace). The individual oligonucleotide binding and unbinding events can be detected simultaneously by confocal microscopy as indicated by stepwise changes in the fluorescence signal (red trace), which are generally coincident with the pauses in the extension. (b) Close-up view of the extension trace in (a) at 158 s showing the fast folding and unfolding transitions (∼100 s−1) of the hairpin. (c) Bandwidth-dependent signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The fluorescence signal corresponding to a single binding event is mean-filtered to 50 Hz, 16.6 Hz, 10 Hz, and 3 Hz, respectively, with the corresponding SNRs indicated. (d) Measured SNR as a function of the concentration of the Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide in the solution. Inset shows the fluorescence signals obtained at 12 nM and 20 nM Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide. All measurements were performed with ∼3 μW of fluorescence excitation power.

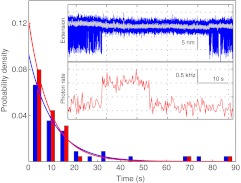

Figure 6.

Comparison of the pause duration in the extension trace and the fluorescence lifetime. Distributions of the pause duration (blue bars) and fluorescence lifetime (red bars) can be fitted with single exponentials (blue and red lines), yielding average lifetimes of 10.7 s and 9.1 s for the hopping pauses and the fluorescence lifetime, respectively (N = 38). Shown in the inset is an event of Cy3 photobleaching prior to dissociation of the oligonucleotide from the hairpin sequence, as indicated by comparison of the pause in extension (blue trace mean-filtered to 1 kHz and grey trace mean-filtered to 50 Hz) and the corresponding fluorescence signal (red trace mean-filtered to 3.3 Hz). Note that the grey trace only shows the extension of open state of the hairpin in the hopping region.

We were able to directly monitor the association and dissociation of individual oligonucleotides using single-molecule fluorescence. Here, the fluorescence signal of a bound oligonucleotide on the hairpin sequence is superimposed on a fluorescence background from diffusive oligonucleotides in the confocal volume. We observed stepwise increases in the fluorescence intensity concurrent with the pauses in the hairpin's extension hopping, followed by fluorescence decreases and a corresponding appearance of extension hopping (Fig. 5a, red trace). These fluorescence changes manifest individual binding and unbinding events of the oligonucleotide to the hairpin. The distribution of the duration of the fluorescence signal can also be fit by a single exponential function, yielding an apparent dwell time of 9.1 s (Fig. 6, red bars and line). This average dwell time is close to the average pause duration of 10.7 s measured from the extension change, indicating that oligonucleotide binding clamps the hairpin in the open state. Consistent with this observation, the fluorescence signal lasted as long as the oligonucleotide was bound to the hairpin in the majority (∼90%) of the binding events. Only in ∼10% of the observed binding events was Cy3 photobleached before the extension hopping was resumed (Fig. 6, inset), which leads to the slightly smaller dwell time of the oligonucleotide measured from fluorescence than from extension pauses. This dwell time difference suggests an intrinsic average Cy3 lifetime of 61 s due to photobleaching under our experimental conditions, a value close to previous measurements.23 Thus, single-molecule fluorescence detection is not compromised in our combined instrument. Overall, the fluorescence signal well reports the binding state of the oligonucleotide on the hairpin sequence. Finally, we noticed a 0.6 nm decrease in the extension of the hairpin in the oligonucleotide-bound state compared to its unfolded state (Fig. 6, inset, gray line), consistent with the prediction based on DNA mechanics.25, 41 This observation corroborates the sub-nanometer spatial resolution of our instrument. Taken together, these results suggest a successful combination of optical trapping and single-molecule fluorescence detection in our instrument.

The data shown in Figs. 5a, 5b were displayed at bandwidths of 1 kHz for the extension trace and 3.3 Hz for the fluorescence trace. To examine the highest temporal correlation between the two signals, we analyzed the traces in higher bandwidths. The extension changes of the hairpin are sufficiently large and can be detected with a temporal resolution of ∼5 kHz (Fig. 4b). For the fluorescence trace we calculated the SNR at different bandwidths. At 8 nM Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide, the SNR is reduced from ∼5.2 at a bandwidth of 3.3 Hz to ∼1.4 at a bandwidth of 50 Hz (Fig. 5c). Filtering the data to a higher bandwidth will further deteriorate the SNR, making the identification of binding events unreliable. Therefore, changes in the fluorescence signal can only be correlated with an accuracy of 20 ms to the changes in the extension measured by the optical tweezers, despite the exceptional temporal resolution offered by the optical tweezers in this case.

The performance of the fluorescence detection in the current assay is also affected by the concentration of the Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide. At the same 3.3 Hz bandwidth, the SNR reduces from 5.2 at 8 nM fluorophore to 2.9 and 2.4 at 12 nM and 20 nM fluorophore in the solution, respectively. This SNR reduction is caused by greater fluorescence background from diffusive fluorophores in the confocal volume at higher fluorophore concentrations. Assuming a confocal volume of 1 fL, the average number of fluorophore molecules in the confocal volume increases from ∼5 at 8 nM to ∼12 at 20 nM. Consequently, association of a single fluorophore to the DNA hairpin sequence will result in fluorescence increases of ∼20% at 8 nM and ∼8% at 20 nM, which are confirmed by our observations (Fig. 5a). Therefore, the concentration-dependent SNR reduction fundamentally limits the fluorophore concentration that can be used in this and similar assays.

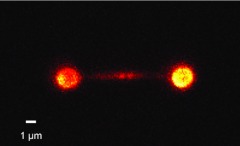

Wide-field fluorescence imaging capabilities

It is advantageous to image a single molecule in a wide-field format in the presence of optical traps.8, 27 In our setup this can be implemented by inserting a lens (L2) and diverting the fluorescence signal to an EMCCD camera (Fig. 1). To demonstrate the wide-field imaging capabilities of the instrument, we visualized a single λ DNA molecule stretched between two polystyrene beads of ∼2 μm in diameter (Fig. 7). The DNA was stained by POPO-3 intercalating dye added in the solution. Note that the wide-field fluorescence excitation light is again interlaced with the trapping laser light to minimize photobleaching.

Figure 7.

Wide-field fluorescence image of a λ DNA molecule tethered between two polystyrene beads. The image was acquired in a buffer containing 250 nM POPO-3 dye under the condition of ∼3 mW of wide-field fluorescence excitation light and 0.1 s exposure time. The beads are also visible due to non-specific binding of the dye to bead surfaces.

CONCLUSIONS

We have presented a dual-trap instrument with angstrom-level resolution and single fluorophore sensitivity. The optical tweezer part of the instrument can be operated independently and supports both variable and constant force mode of operation. We combined fluorescence microscopy with dual-trap optical tweezers via an interlacing scheme at 100 kHz. Under these conditions the spatial resolution of the optical tweezers reaches to 1 bp. The fluorescence capabilities of the instrument were demonstrated by visualizing a single λ DNA molecule and by studying the mechanically induced transitions of a DNA hairpin in the presence of single Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide. In this assay, the changes in the fluorescence signal due to the binding and unbinding of the oligonucleotide were directly correlated with pauses in the extension hopping of the hairpin measured by the optical tweezers.

The use of a separate laser for position detection in the optical tweezers allows for the implementation of a passive force clamp and facilitates combined optical trapping and fluorescence measurements. As a result, decoupling optical trapping and position detection enables easy switching between different operation modes. We believe that the versatility of the instrument, which can be extended to include other single molecule techniques such as FRET, will help study more complex biological systems than before.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Honglian Guo for advice on the instrument design, and the rest of the members of the Zhang group for reading the paper. We also thank Joerg Bewersdorf, Travis Gould, Michael Mlodzianoski, and Tobias Hatwich for advice on the fluorescence microscopy. Support for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM093341) to Y.Z.

References

- Bustamante C., Cheng W., and Mejia Y. X., Cell 144, 480–497 (2011). 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson M. H., Landick R., and Block S. M., Mol. Cell 41, 249–262 (2011). 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yodh J. G., Schlierf M., and Ha T., Q. Rev. Biophys. 43, 185–217 (2010). 10.1017/S0033583510000107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt J. R., Chemla Y. R., Smith S. B., and Bustamante C., Ann. Rev. Biochem. 77, 205–228 (2008). 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.043007.090225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner M. D., Zhou R., and Ha T., Biopolymers 95, 332–344 (2011). 10.1002/bip.21587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman K. C. and Nagy A., Nat. Methods 5, 491–505 (2008). 10.1038/nmeth.1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez J. M. and Li H., Science 303, 1674–1678 (2004). 10.1126/science.1092497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amitani I., Baskin R. J., and Kowalczykowski S. C., Mol. Cell 23, 143–148 (2006). 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein I. J., Visnapuu M. L., and Greene E. C., Nature (London) 468, 983–987 (2010). 10.1038/nature09561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Blainey P. C., Schroeder C. M., and Xie X. S., Nat. Methods 4, 397–399 (2007). 10.1038/nmeth1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha T., Enderle T., Ogletree D. F., Chemla D. S., Selvin P. R., and Weiss S., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 6264–6268 (1996). 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz A., Tomishige M., Vale R. D., and Selvin P. R., Science 303, 676–678 (2004). 10.1126/science.1093753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomre D. and Bewersdorf J., Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 26, 285–314 (2010). 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo C., McKinney S. A., Nakamura M., Rasnik I., Myong S., and Ha T., Cell 126, 515–527 (2006). 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasnik I., McKinney S. A., and Ha T., Nat. Methods 3, 891–893 (2006). 10.1038/nmeth934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H. S., Louis J. M., and Eaton W. A., Biophys. J. 98, 696–706 (2010). 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H. S., Louis J. M., and Eaton W. A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 11837–11844 (2009). 10.1073/pnas.0901178106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodside M. T., Anthony P. C., Behnke-Parks W. M., Larizadeh K., Herschlag D., and Block S. M., Science 314, 1001–1004 (2006). 10.1126/science.1133601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodside M. T., Behnke-Parks W. M., Larizadeh K., Travers K., Herschlag D., and Block S. M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6190–6195 (2006). 10.1073/pnas.0511048103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Sirinakis G., and Zhang Y. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 12749–12757 (2011). 10.1021/ja204005r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang M. J., Fordyce P. M., Engh A. M., Neuman K. C., and Block S. M., Nat. Methods 1, 133–139 (2004). 10.1038/nmeth714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarsa P. B., Brau R. R., Barch M., Ferrer J. M., Freyzon Y., Matsudaira P., and Lang M. J., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 46, 1999–2001 (2007). 10.1002/anie.200604546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brau R. R., Tarsa P. B., Ferrer J. M., Lee P., and Lang M. J., Biophys. J. 91, 1069–1077 (2006). 10.1529/biophysj.106.082602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohng S., Zhou R. B., Nahas M. K., Yu J., Schulten K., Lilley D. M. J., and Ha T. J., Science 318, 279–283 (2007). 10.1126/science.1146113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comstock M. J., Ha T., and Chemla Y. R., Nat. Methods 8, 335–40 (2011). 10.1038/nmeth.1574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Mameren J., Gross P., Farge G., Hooijman P., Modesti M., Falkenberg M., Wuite G. J., and Peterman E. J., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 18231–18236 (2009). 10.1073/pnas.0904322106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Mameren J., Modesti M., Kanaar R., Wyman C., Peterman E. J., and Wuite G. J., Nature (London) 457, 745–748 (2009). 10.1038/nature07581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R., Kozlov A. G., Roy R., Zhang J., Korolev S., Lohman T. M., and Ha T., Cell 146, 222–232 (2011). 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijk M. A., Kapitein L. C., Mameren J., Schmidt C. F., and Peterman E. J., J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 6479–6484 (2004). 10.1021/jp049805+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent-Glandorf L. and Perkins T. T., Opt. Lett. 29, 2611–2613 (2004). 10.1364/OL.29.002611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbondanzieri E. A., Greenleaf W. J., Shaevitz J. W., Landick R., and Block S. M., Nature (London) 438, 460–465 (2005). 10.1038/nature04268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt J. R., Chemla Y. R., Izhaky D., and Bustamante C., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 9006–9011 (2006). 10.1073/pnas.0603342103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. B., Cui Y. J., and Bustamante C., Methods Enzymol. 361, 134–162 (2003). 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)61009-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. L., Smith C. L., Saha A., Grill S. W., Mihardja S., Smith S. B., Cairns B. R., Peterson C. L., and Bustamantel C., Mol. Cell 24, 559–568 (2006). 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecconi C., Shank E. A., Dahlquist F. W., Marqusee S., and Bustamante C., Eur. Biophys. J. 37, 729–738 (2008). 10.1007/s00249-007-0247-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecconi C., Shank E. A., Bustamante C., and Marqusee S., Science 309, 2057–2060 (2005). 10.1126/science.1116702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z. Q., Gao Y., Sirinakis G., Guo H. L., and Zhang Y. L., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 5711–5716 (2012). 10.1073/pnas.1116784109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittes F. and Schmidt C. F., Opt. Lett. 23, 7–9 (1998). 10.1364/OL.23.000007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4752190 for a detailed part list of the instrument.

- Greenleaf W. J., Woodside M. T., Abbondanzieri E. A., and Block S. M., Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 208102 (2005). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.208102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante C., Bryant Z., and Smith S. B., Nature (London) 421, 423–427 (2003). 10.1038/nature01405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]