Abstract

Biological communication by means of structural color has existed for at least 500 million years. Structural color is commonly observed in the animal kingdom, but has been little studied in plants. We present a striking example of multilayer-based strong iridescent coloration in plants, in the fruit of Pollia condensata. The color is caused by Bragg reflection of helicoidally stacked cellulose microfibrils that form multilayers in the cell walls of the epicarp. We demonstrate that animals and plants have convergently evolved multilayer-based photonic structures to generate colors using entirely distinct materials. The bright blue coloration of this fruit is more intense than that of any previously described biological material. Uniquely in nature, the reflected color differs from cell to cell, as the layer thicknesses in the multilayer stack vary, giving the fruit a striking pixelated or pointillist appearance. Because the multilayers form with both helicoidicities, optical characterization reveals that the reflected light from every epidermal cell is polarized circularly either to the left or to the right, a feature that has never previously been observed in a single tissue.

Keywords: helicoidal self-assembly, mimicry, fruit dispersal

Structural color is surprisingly widespread in nature (1–7), mainly used by animals for signaling, mimicry, and mate choice (8). However, the role of structural coloration in plants is only partially understood and has been studied primarily with respect to flowers and leaves (8–13). In fruits (14–16), mimicry is likely to be the main function. By imitating the appearance of a fresh nutritious fruit, plants may have evolved to mislead their seed dispersers, without offering them any nutritious reward. This strategy could avoid the energy cost of producing fresh pulp. Structural color gives the fruit a brilliant and intense appearance that is maintained after it falls from the plant, increasing the probability of attracting an animal and being dispersed. Alternatively, structural-colored fruits might achieve dispersal by attracting birds or animals that decorate nests or arenas for mate attraction.

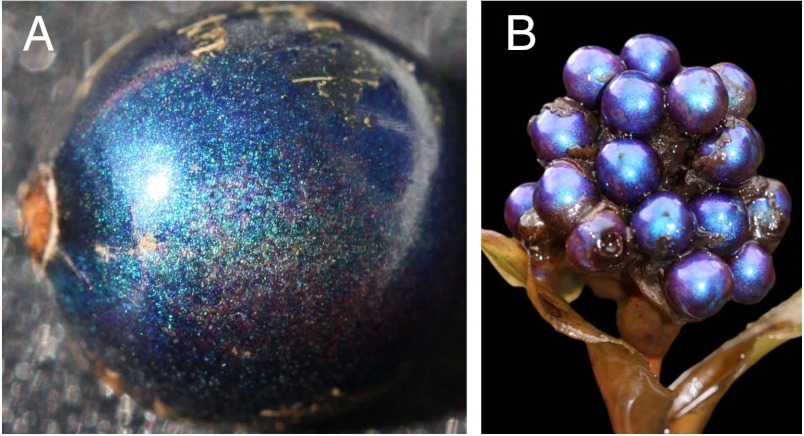

In this study, the optical response of the fruit of Pollia condensata C.B. Clarke is analyzed in relation to its anatomy. Pollia is a pantropical and warm-temperate genus of approximately 20 species of herbaceous perennials in the monocot spiderwort family Commelinaceae. Pollia condensata, an African forest understory species that ranges from the Ivory Coast to Ethiopia and south to Angola and Mozambique, produces dense terminal clusters of up to 40 spherical metallic-blue fruits (Fig. 1). Each dry fruit contains up to 18 hard, dry seeds. Metallic blue is the predominant color of mature fruits in the genus Pollia and is unique within Commelinaceae (17). The Pollia fruit shown in Fig. 1A was collected in 1974 in Ghana and preserved in the herbarium of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, United Kingdom. Despite its age, the dry fruit has retained its strong blue color and characteristic pixelated appearance (see Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). In the field brightly colored fruits are sometimes observed even on completely dead shoots.

Fig. 1.

Photographs of Pollia condensata fruits. (A) Single fruit from dried herbarium specimen collected in Ghana (Kew Herbarium: Faden and Lock 74/37, 1974). The blue color of the fruit is not uniform but has a brilliant pixelated iridescent appearance with green and purple/red speckles. (B) Infructescence (cluster of fruits) from alcohol-preserved specimen collected in Ethiopia (Kew Herbarium: Moult 24, 1974). The diameter of each fruit is about 5 mm.

The fruit of Pollia condensata lacks any blue pigment that we could extract using conventional means, so to investigate its striking color, we studied its anatomy (Fig. 2). The strong gloss of the fruit is produced by the flat and transparent cuticle (Fig. 2A). The transverse section in Fig. 2B illustrates (1) the epicarp consisting of three to four layers of thick-walled cells, (2) two to three underlying layers of cells containing dense brown tannin pigments (9), and (3) an inner region of thin-walled cells that have relatively few contents when the fruit is mature. The cell walls in region 1 create a periodic multilayer envelope shown in Fig. 2C. The blue iridescence originates from these cells. Light transmitted through these top-layer cells is mostly absorbed by the brown tannin pigments in 2, which increase the purity of the structural color. Similarly colored melanin pigments perform the same function in many structurally colored birds and butterflies (18). The underlying cells in layer 3 scatter the remaining transmitted light. The higher magnification transmission electron microscopy (TEM) cross-sectional image in Fig. 2D shows the helicoidal structure of the multilayer in Fig. 2C. It consists of a series of twisting arcs, which correspond with individual segments of cellulose microfibrils oriented in a helicoidal structure. Using Neville’s definition (19), the structure in Fig. 2D and the scheme in Fig. 2E are left-handed (LH) helicoids.

Fig. 2.

Anatomy of Pollia condensata fruit. (A) SEM image of the fruit surface showing smooth cuticular layer. (B) TEM cross-section showing three distinct tissue zones: (1) an outer epicarp of 3–4 layers of thick-walled cells, (2) an intermediate region of 2–3 layers of tanniniferous cells, and (3) a zone of thin-walled cells. (C) TEM of a single thick-walled cell from layer 1. (D) TEM of the cellulose microfibrils that constitute the thick cell wall in layer 1. The red lines highlight the twisting direction of the microfibrils. (E) (Left) Scheme showing a wedge of an LH helicoid with the arched pattern exposed on the oblique face (adapted from ref. (24)). (Right) Circularly polarized beams of light, with  the wave vector of the light. The handedness of the transmitted and reflected light depends on the handedness of the helicoid. Here, light transmitted through the structure (

the wave vector of the light. The handedness of the transmitted and reflected light depends on the handedness of the helicoid. Here, light transmitted through the structure ( pointing down) is LH circularly polarized, while the reflected light (

pointing down) is LH circularly polarized, while the reflected light ( pointing up) is RH. (F) 3D representation of the orientation of cellulose microfibril assembly and a transmitted circularly polarized beam.

pointing up) is RH. (F) 3D representation of the orientation of cellulose microfibril assembly and a transmitted circularly polarized beam.

In conventional multilayer interference, color-dependent reflection arises from the interference caused by sharp periodic boundaries in the refractive index. By contrast, in Pollia condensata fruit, the continuous rotation of the orientation of the plane in which the approximately 5-nm wide fibrils lay parallel to each other gives rise to a difference in which circularly polarized light of opposing handedness interacts with the helical stack. Color-selective transmission and reflection of light arises from this difference in the propagation of light with a wavelength that matches the helical pitch of the stack-structure (20), resembling the helically stacked chitin that occurs in the exoskeleton of some beetles (21).

The distance over which the fibrils have the same orientation, p, defines the periodicity of the helicoid and therefore the range of wavelengths λ that are reflected by the stack. In the simplified case where the difference between the refractive index of the cellulose fibrils and the matrix in which they are dispersed is low, maximum reflectivity is obtained for λ = p ∗ 2 ∗ n where n is the average refractive index (20). Using n = 1.53 of dried cellulose (22) and a mean value of p = 145 nm (p varies from cell to cell in the range 125–200 nm), λ ≈ 445 nm is predicted, corresponding with blue coloration.

Helicoidal assembly of different types of microfibrils is a common structural motif observed in all kingdoms of life (23), though in most cases it is not associated with iridescence. In plants, the mechanism of helicoidal cell-wall formation remains a matter of debate (24–26). One hypothesis is that the molecular self-assembly of cellulose is guided by the presence of hemicellulose (19, 23, 24, 27). In this model, the handedness of the material is determined by the inherent chirality of the molecules that compose the cell wall, and all cells would be expected to have the same handedness. A similar mechanism has been suggested for chitin in the animal kingdom. For example, different species of scarab beetles (Scarabaeidae) have chitin-based helicoidal structures that show the same observed handedness (2). More recently it has been proposed that the helicoidal structure of cellulose microfibrils is determined by rotation of microtubules in the underlying cell (25, 28). Microtubules have been shown to change position during cell growth and can rotate in both clockwise and anticlockwise directions. The mechanism by which the direction of microtubule rotation is determined is as yet unknown, but this behavior can lead to both LH and right-handed (RH) helicoids, because stack orientation is independent of the chirality of the microfibrils. Such a mechanism would fit the pattern we describe here, although the production of the Pollia condensata helicoids would rely on no changes in direction of microtubule rotation during the growth of each individual cell.

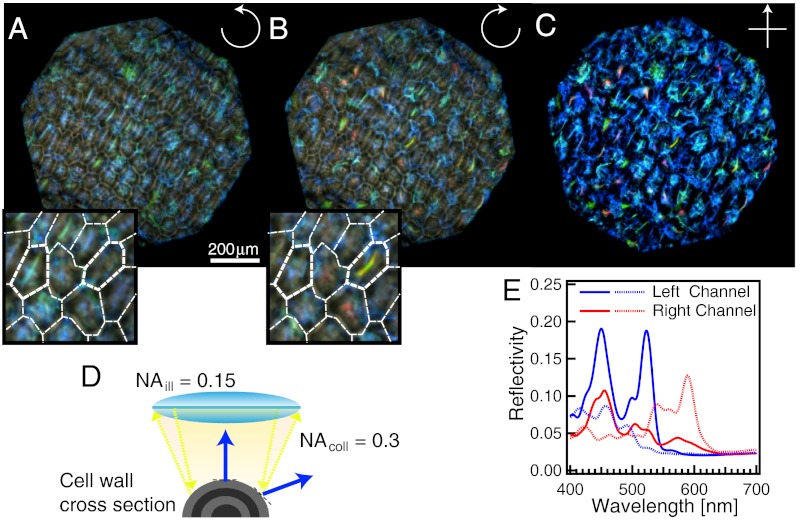

The images of Pollia fruits in Fig. 3A and B were obtained using RH and LH circular polarization filters, respectively, using nonpolarized illumination. As the fruit is extremely glossy, part of the light (0.6%) is reflected at the cuticle-air interface, reducing the color contrast in epi-illumination. By decreasing the objective field of view and illuminating through a low numerical aperture (NA ≈ 0.15), it is possible to improve the contrast and resolve the position of the cells in the outer epicarp layer. The central reflection from each cell has a specific coloration, with the remainder of the optical spectrum transmitted. This is characteristic for Bragg reflection from a periodic multilayer made from transparent materials, and allows observation of additional reflections from underlying cells. See schematic mechanism for color reflection in Fig. S2. Because of the ellipsoidal shape of the cells, only part of their enveloping multilayered wall is perpendicular to the optical axis, giving rise to colored stripes along the cell center, schematically shown in Fig. 3D.

Fig. 3.

Polarized reflection of Pollia condensata fruit. (A) LH and (B) RH optical micrographs of the same area of the fruit under epi-illumination. The insets show a zoom of the central areas, with white lines delimiting the cells. (C) The same area of the fruit surface was also imaged between crossed polarizers. All three images were obtained using a × 10 objective. (D) Schematic representation of light reflection from a curved multilayer, representing the ellipsoidal shape of the epicarp cells. Only light from the central part of the cell is reflected into the numerical aperture of the objective (NA = 0.3), resulting in a color stripe in the center of each cell, seen in A and B. (E) Spectra from two different cells (continuous and dotted lines, respectively) for the two polarization channels (red and blue color, respectively). Auxiliary minor spectral features leading to the double-peak structure arise from the stacked nature of the cells in the epicarp (Fig. 2B). This leads to spectral contributions from underlying cells with different p values.

Comparison of Fig. 3A and B reveals four salient optical features: (i) The narrow colored stripes lie in the center of each imaged cell, confirming that the reflected color arises from the Bragg stacks in the cell wall. (ii) Each cell displays this stripe in only one polarization channel (see highlighted cells in the inset). (iii) Superimposed on the color stripes are larger patches of color that correspond with the signal from cells at a different focal plane. These patches have a well-defined circular polarization state. (iv) Red colored cells are detected only in the RH channel near the outer surface of the epicarp.

When observed between crossed linear polarizers in Fig. 3C, the reflection from the air-cuticle interface (i.e., the gloss) is removed and a superposition of the two circular polarization channels is evident. The brightness of structural color is impressive, providing a total (unpolarized) reflectivity of about 30% compared with a silver mirror. This is the highest reported reflectivity of any biological organism including beetle exoskeleton (2, 5), bird feathers (29) and the famously intense blue of Morpho butterfly scales (2). Fig. 3E shows spectra collected for the central stripes of two different cells in both polarization channels, which is lower than the total 30% reflectivity because it represents the selected reflectivity in a single channel. The baseline signal of 0.3% in both channels stems from the reflection at the air-cuticle interface. The high intensity peaks correspond with the Bragg reflection from the multilayer stacks in the cell wall. The wavelengths of these peaks differ from cell to cell and depend on the direction of observation.

In order to better characterize the color response of the different parts of the fruit, the LH and RH circularly polarized light was passed through a tunable liquid crystal color filter, which was placed in front of the camera. This filter splits the reflected light into monochromatic images with a 10-nm bandwidth that can be scanned across the entire visible range (400–700 nm). Fig. 4 shows three color slices (430, 530, and 630 nm, respectively) of the same area of the fruit, with three cells outlined. The blue channel in Fig. 4 A and B shows bright patches produced by Bragg reflection with signal intensities substantially above the background gloss. The intensity of the average reflected light is similar in the two polarization channels. The contrast in the green and red channels is much weaker, which indicates a greater role of the gloss compared with reflection from the cell surfaces. Because of the overall lower reflection in these two channels, the cell boundaries, which scatter light, are visible. In the green channel (Fig. 4 C and D), a multilayer peak of reflectivity is seen in some cells of both polarization channels. In contrast, the red images in Fig. 4 E and F show (sparse) multilayer reflection only in the RH channel. By comparing the signal in the channels, we conclude that the number of cells with an LH helicoid equals the number with the opposite handedness.

Fig. 4.

Color-filtered images corresponding with Fig. 3A and B. The color dispersion of LH and RH reflected light was imaged by inserting a tunable liquid crystal filter in front of the CCD camera. Ten-nanometer-wide reflection bands were imaged at (A and B) 430 nm, (C and D) 530 nm, and (E and F) 630 nm. Images with different colors were individually normalized (images with the same color have the same normalization).

The biological significance of the structural coloration of Pollia fruits is that they resemble true fleshy fruits without furnishing a reward. They retain their attractiveness over a long period of time, even on dead shoots or when shed from the plant. In the low light levels of the forest understory, where Pollia condensata is found, brilliant blue coloration will be highly visible. The fruits might attract birds that collect brightly colored objects to use in mating displays. Alternatively, because the dry fruits of Pollia condensata resemble the pigmented blue berries of Psychotria peduncularis (Salisb.) Steyerm. (a subshrub species in the asterid eudicot coffee family Rubiaceae that co-occurs in the same habitats), the fruits might be achieving dispersal through mimicry. In either case birds are the likely seed-dispersers, which might account for the wide distribution not only of Pollia condensata but of the genus as a whole (30).

In conclusion, convergent evolution in both plants and animals has independently produced multilayered structures that create structural coloration. Fruits of Pollia condensata bear helicoidal structures similar to those of scarab beetles but with even more intense reflectivity. Our investigation demonstrates that variation in multilayer thickness in the Pollia fruits provides an optical response that is apparently unique in nature. The multilayered cell walls of the fruit act as curved micro-Bragg reflectors, each of which reflects a specific color that differs from cell to cell. While blue reflectance is dominant, the sparse distribution of green and red reflecting cells gives the fruit an intriguing pixellated (pointillist) appearance, not recorded in any other organism. Finally, because the direction of the helicoid patterning differs from cell to cell, this fruit also provides a unique example of biological tissue that can selectively reflect both left and right circularly polarized light.

Materials and Methods

The photographs in Fig. 1 were taken with a Canon EOS 450D camera equipped with a 60-mm macro-lens 1∶2.8 under solar illumination. For scanning electron microscope (SEM) imaging, the specimen was mounted on an aluminum stub, coated with platinum using a sputter coater (Emitech K550), and examined using a Hitachi S-4700 SEM at 2 kV. For imaging using TEM, fruits were cut into small fragments and fixed in 3% phosphate-buffered glutaraldehyde followed by 1% osmium tetroxide. Fixed samples were taken through a graded ethanol and LR White resin series prior to embedding. Ultrathin sections (50–100 nm) were cut using an ultramicrotome (Reichert-Jung Ultracut), collected on formvar-coated copper slot grids, and post-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Samples were imaged in a Hitachi H-7650 TEM with integral AMT XR41 digital camera. Optical imaging and spectroscopy were performed using a custom-modified BX-51 Olympus optical microscope equipped with a color digital CCD camera (Lumenera Infinity 2-1C). Light from a halogen lamp (Olympus, U-LH100-3-5) served as illumination. The collimated light was coupled into a × 10 objective (Olympus, MPLFLN-BD 10). The reflected signal from the specimen was filtered using a superachromatic quarter waveplate (B. Halle) combined with a polarizer (Thorlabs). The polarizer and the waveplate were mounted onto independent motorized rotation stages that can be inserted and removed from the optical path. Part of the transmitted signal was coupled into a 50-μm core optical fiber (Ocean Optics) mounted in confocal configuration to achieve a spatial resolution of approximately 10 μm, smaller than the cell dimensions. The remaining signal was passed through a tunable liquid crystal filter (CRI, Varispec) and focused into the CCD chip for imaging. To detect the reflection of RH and LH circularly polarized light, a quarter waveplate was inserted into the detection path, and for cross-polarized images, linear polarizers were inserted into the illumination and detection beam paths.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank R.M. Bateman and M.M. Thomas for helpful discussion. This work was supported by the Leverhulme Trust (F/09-741/G) and by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/G060649/1).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1210105109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Parker AR. 515 million years of structural colour. J Opt A Pure Appl Opt. 2000;2:R15–R28. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinoshita S, Yoshioka S, Miyazaki J. Physics of structural colors. Rep Prog Phys. 2008;71:076401. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vukusic P, Sambles JR. Photonic structures in biology. Nature. 2003;424:852–855. doi: 10.1038/nature01941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vukusic P, Sambles JR, Lawrence CR, Wootton RJ. Quantified interference and diffraction in single Morpho butterfly scales. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1999;266:1403–1411. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seago AE, Brady P, Vigneron J-P, Schultz TD. Gold bugs and beyond: A review of iridescence and structural colour mechanisms in beetles (Coleoptera) J R Soc Interface. 2009;6:165–184. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0354.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michielsen K, Stavenga DG. Gyroid cuticular structures in butterfly wing scales: Biological photonic crystals. J R Soc Interface. 2008;5:85–94. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2007.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoddard MC, Prum RO. How colorful are birds? Evolution of the avian plumage color gamut. Behav Ecol. 2011;22:1042–1052. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doucet SM, Meadows MG. Iridescence: A functional perspective. J R Soc Interface. 2009;6:S115–S132. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0395.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee DW. Nature’s Palette. Chicago: Chicago Univ Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas KR, Kolle M, Whitney HM, Glover BJ, Steiner U. Function of blue iridescence in tropical understorey plants. J R Soc Interface. 2010;7:1699–1707. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitney HM, et al. Floral iridescence, produced by diffractive optics, acts as a cue for animal pollinators. Science. 2009;323:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1166256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee DW, Lowry JB. Physical basis and ecological significance of iridescence in blue plants. Nature. 1975;254:50–51. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee D. Iridescent blue plants. Am Sci. 1997;85:56–63. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee DW. Ultrastructural basis and function of iridescent blue colour of fruits in Elaeocarpus. Nature. 1991;394:260–262. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cazetta E, Zumstein LS, Melo-Júnior TA, Galetti M. Frugivory on Margaritaria nobilis l. f. (euphorbiaciaceae): Poor investment and mimetism. Rev Bras Bot. 2008;31:303–308. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee D, Taylor G, Irvine A. Structural fruit coloration in Delarbrea michieana (Araliaceae) Int J Plant Sci. 2000;161:297–300. doi: 10.1086/314249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faden RB. In: Flora of Tropical East Africa: Commelinaceae, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew—Flora of Tropical East Africa. Beentje H, editor. Kew, UK: Royal Botanic Gardens; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shawkey MD, Morehouse NI, Vukusic P. A protean palette: Colour materials and mixing in birds and butterflies. J R Soc Interface. 2009;6:S221–S231. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0459.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neville AC. Biology of Fibrous Composites: Developments Beyond the Cell Membrane. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1993. pp. 85–123. [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Vries H. Rotatory power and other optical properties of certain liquid crystals. Acta Crystallogr. 1951;4:219–226. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma V, Crne M, Park JO, Srinivasarao M. Structural origin of circularly polarized iridescence in jeweled beetles. Science. 2009;325:449–451. doi: 10.1126/science.1172051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woolley JT. Refractive index of soybean leaf cell walls. Plant Physiol. 1975;55:172–174. doi: 10.1104/pp.55.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kutschera U. The growing outer epidermal wall: Design and physiological role of a composite structure. Ann Bot. 2008;101:615–621. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neville AC, Levy S. In: Biochemistry of Plant Cell Walls. Brett C, Hillman J, editors. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan J. Microtubule and cellulose microfibril orientation during plant cell and organ growth. J Microsc. 2012;247:23–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2011.03585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Habibi Y, Lucia LA, Rojas OJ. Cellulose nanocrystals: Chemistry, self-assembly, and applications. Chem Rev. 2010;110:3479–3500. doi: 10.1021/cr900339w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neville AC. A pipe-cleaner molecular model for morphogenesis of helicoidal plant cell walls based on hemicellulose complexity. J Theor Biol. 1988;131:243–254. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan J, et al. The rotation of cellulose synthase trajectories is microtubule dependent and influences the texture of epidermal cell walls in Arabidopsis hypocotyls. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:3490–3495. doi: 10.1242/jcs.074641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zi J, et al. Coloration strategies in peacock feathers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12576–12578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133313100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faden RB. In: Flowering Plants, Monocotyledons: Alismatanae and Commelinanae, The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. Kubitzki K, editor. Vol 4. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1998. pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.