Abstract

Fossils and molecular data are two independent sources of information that should in principle provide consistent inferences of when evolutionary lineages diverged. Here we use an alternative approach to genetic inference of species split times in recent human and ape evolution that is independent of the fossil record. We first use genetic parentage information on a large number of wild chimpanzees and mountain gorillas to directly infer their average generation times. We then compare these generation time estimates with those of humans and apply recent estimates of the human mutation rate per generation to derive estimates of split times of great apes and humans that are independent of fossil calibration. We date the human–chimpanzee split to at least 7–8 million years and the population split between Neanderthals and modern humans to 400,000–800,000 y ago. This suggests that molecular divergence dates may not be in conflict with the attribution of 6- to 7-million-y-old fossils to the human lineage and 400,000-y-old fossils to the Neanderthal lineage.

Keywords: hominin, molecular dating, primate, speciation

Over 40 y ago, Sarich and Wilson used immunological data to propose that humans and African great apes diverged only about 5 million y ago, some three to four times more recently than had been assumed on the basis of the fossil record (1). Although contentious at the time (e.g., ref. 2), this divergence has since been repeatedly estimated from DNA sequence data at 4–6 million years ago (Ma) (3–8). However, this estimate is incompatible with the attribution of fossils older than 6 Ma to the human lineage. Although the assignment of fossils such as the ∼6 Ma Orrorin (9) and the 6–7 Ma Sahelanthropus (10) to the human lineage remains controversial (11), it is also possible that the divergence dates inferred from DNA sequence data are too recent.

The total amount of sequence differences observed today between two evolutionary lineages can be expressed as the sum of two values: the sequence differences that accumulated since gene flow ceased between the lineages (“split time”) and the sequence differences that correspond to the diversity in the common ancestor of both lineages. The extent of variation in the ancestral species may be estimated from the variance of DNA sequence differences observed across different parts of the genome between the species today, which will be larger the greater the level of variation in the ancestral population. By subtracting this value from the total amount of sequence differences, the sequence differences accumulated since the split can be estimated. The rate at which DNA sequence differences accumulate in the genome (“mutation rate”) is needed to then convert DNA sequence differences into split times.

In prior research, mutation rates have been calculated using species split times estimated from the fossil record as calibration points. For calculating split times between present-day humans and great apes, calibration points that assume DNA sequence differences between humans and orangutans have accumulated over 13 Ma (12), or 18 Ma (5, 8), or between chimpanzees and humans over 7 Ma (13, 14) have been used. Recently, researchers have commonly used a mutation rate of 1 × 10−9 mutations per site per year (e.g., refs. 4, 6, 8, 15) derived from the observed DNA sequence difference of around 1.3% between the human and chimpanzee genomes (8, 15, 16) and an assumed DNA sequence divergence between these species at 7 Ma, as well as from an observed sequence difference of 6.46% between the human and macaque genomes (17) and an assumption of their DNA sequence divergence at 25 Ma. Although ubiquitous, this approach has an inherent circularity and is subject to possible error because it relies on the accuracy of the ages of fossils. Whereas approaches to account for uncertainty in the fossil record have been proposed (18), a means to avoid the use of fossil calibration points would be useful.

An alternative approach to determine mutation rates is to compare genome sequences from children and their parents (19–21). This approach has the advantage of not relying on the fossil record. However, direct observation of mutation rates per site per generation need to be converted to mutation rates per year to arrive at population split times. For this conversion, we need the relevant generation times, which are the average maternal and paternal age at reproduction in the lineages under consideration. Genetic studies of humans have commonly used a generation time of 20 or 25 y (e.g., references in refs. 5, 22). However, genealogical data spanning the last two or three centuries from three human populations suggest that the average generation time is 30–32 y (23–25). In agreement with this finding, a comprehensive review considering estimated maternal age at first and last childbirth and age differences between spouses in contemporary hunter–gatherers as well as in food-producing countries with varying levels of industrialization inferred an average human generation time of 29 y, with female- and male-specific values of 26 and 32 y, respectively (22). Thus, both direct genealogical and indirect demographic studies conducted in a variety of societies, including those practicing a lifestyle thought to be representative of that of the human lineage for much of its evolutionary history (i.e., hunter–gatherer), are fairly consistent in suggesting that the average present-day human generation time is ∼29 y and that it differs substantially between the sexes.

Previous estimates of split times have used a wide variety of generation times for great apes, including 25 y for chimpanzee, gorilla, and orangutan (5); 20 y for chimpanzee (13, 14) and orangutan (6) or 15 y for chimpanzees (26), gorillas (27), and chimpanzee, gorilla, and orangutan (3). These estimates appear to lack any explicit justification. A recent analysis used information from captive and wild populations regarding female age of first reproduction, interbirth interval, age of last reproduction, and survivorship to estimate female generation times of 22 y for chimpanzees and 20 for gorillas (28). These findings hint that some of the generation times commonly assumed in studies of great apes are excessively short. Furthermore, it is possible that, as is the case in humans, generation times of female great apes may not be representative of those of males.

Here we derive female and male generation times for present-day chimpanzees and gorillas from genetic parentage data collected from large numbers of offspring born into several wild social groups. We consider whether our data are consistent with the suggestion of a positive correlation between body size and generation time in great apes and humans, and explore the implications of our results for dating population split times among these lineages.

Results

Chimpanzee Generation Times.

Using parentage information for 226 offspring born in eight wild chimpanzee communities, we find that the average age of parents is 24.6 y (Table 1). Among communities, the generation times range from 22.5 to 28.9 y, but no consistent difference is observed between western and eastern chimpanzees, suggesting that the variation may arise due to demographic stochasticity rather than consistent ecological or genetic differences between western and eastern chimpanzees.

Table 1.

Generation intervals for each chimpanzee and gorilla study community

| Mean generation interval, y |

||||||||

| Taxa | Study site | No. offspring | Female | CI | Male | CI | Both sexes | CI |

| Western chimpanzees | Taї-North | 28 | 23.03 | 22.19–23.80 | 23.05 | 22.31–23.81 | 23.04 | 22.48–23.58 |

| Taї-Middle | 4 | 31.71 | 28.34–35.15 | 26.06 | 23.90–28.32 | 28.89 | 26.80–31.03 | |

| Taї-South | 28 | 28.76 | 27.54–29.98 | 25.36 | 24.46–26.30 | 27.06 | 26.29–27.84 | |

| Eastern chimpanzees | Gombe-Kasekela | 31 | 24.62 | 24.24–25.00 | 21.84 | 21.75–21.93 | 23.23 | 23.03–23.43 |

| Mahale-M | 14 | 25.03 | 23.95–26.08 | 19.87 | 19.62–20.13 | 22.45 | 21.90–23.00 | |

| Kibale-Ngogo | 72 | 24.5 | 23.80–25.22 | 23.57 | 23.05–24.13 | 24.04 | 23.60–24.48 | |

| Kibale-Kanyawara | 15 | 23.34 | 22.43–24.25 | 28.42 | 27.15–29.75 | 25.88 | 25.04–26.68 | |

| Budongo-Sonso | 34 | 26.08 | 25.03–27.08 | 26.66 | 25.93–27.34 | 26.37 | 25.72–26.95 | |

| All chimpanzees | 226 | 25.18 | 24.86–25.54 | 24.08 | 23.83–24.34 | 24.63 | 24.42–24.85 | |

| Mountain gorillas | Karisoke | 97 | 18.18 | 17.97–18.37 | 20.27 | 20.23–20.30 | 19.22 | 19.12–19.32 |

| Bwindi | 8 | 18.26 | 16.87–19.64 | 21.67 | 20.37–22.93 | 19.97 | 18.96–20.88 | |

| All gorillas | 105 | 18.19 | 18.00–18.39 | 20.37 | 20.27–20.47 | 19.28 | 19.17–19.39 | |

| Humans* | Hunter–gatherers | 157 societies | 25.6 | 31.5 | 28.6 | |||

| Countries | 360 societies | 27.3 | 30.8 | 29.1 | ||||

Fenner 2005 (22). Species-wide averages for chimpanzees and gorillas and human values are shown in bold type.

Some of the chimpanzee communities are known to have experienced substantial mortality in the recent past due to epidemic disease. To check whether this may have altered reproductive patterns, we compared the average generation intervals for communities known to have experienced high infection-induced mortality (Tai North and South communities, Mahale M community, and Gombe Kasekela community) with those that have not (Budongo Sonso community and Kibale Kanyawara and Ngogo communities). The average generation time for the former communities was 24.9, whereas it was 24.3 for the latter. Thus, epidemic diseases are not likely to have drastically affected generation times in these chimpanzee communities.

The age of chimpanzee fathers ranged from 9.3 to 50.4 y, whereas age of mothers ranged from 11.7 to 45.4 y (Fig. S1). Thus, the potential reproductive span of males (41.1 y) is some 7 y, or 22%, longer than that of females (33.7 y). Nonetheless, because more than half (56.2%) of the offspring are produced by fathers between the ages of 15 and 25, whereas most offspring (77%) have mothers between the ages of 15 and 34, the average generation time for males and females is essentially the same (24.1 and 25.2 y, respectively).

Gorilla Generation Times.

Using information on the parentage of 105 mountain gorilla offspring from two research sites, the average female and male generation times were 18.2 and 20.4 y, respectively, with an average of 19.3 y for both sexes (Table 1). Thus, generation times in gorillas are substantially shorter than in chimpanzees.

The ages of gorilla fathers ranged from 10.8 to 30.9 y, whereas the ages of gorilla mothers ranged from 7.3 to 38.0 y, suggesting that female gorillas reproduce over substantially longer periods than do males. In fact, we found that more than 75% of offspring were sired by males between the ages of 15 and 24, whereas the distribution of gorilla maternal ages varied considerably more (Fig. S1). Thus, in contrast to chimpanzees, the potential reproductive lifespan of gorilla females is longer than for gorilla males.

Generation Times and Body Mass.

Several life history characteristics, such as age of weaning, female age at maturity, and female age at first breeding, exhibit a positive relationship with body mass across primates (29). To evaluate whether generation time also increases with body size in the great apes, we compared generation times and body mass estimates. Supplementing our data with a recent estimate of orangutan female generation time based on demographic information (28), we find that humans, chimpanzees, and female orangutans display similar masses and generation times, whereas male and female gorillas have more than twice as large body masses yet short generation times, resulting in an overall negative association between mass and generation times in these taxa (females, generation time = −0.102 mass + 33.5, R2 = 0.88; males, generation time = −0.059 mass + 30.88, R2 = 0.48) (Table S1).

Generation Times and Mutation Rates.

DNA sequencing of human families has recently yielded four direct estimates of mutation rates ranging from 0.97 × 10−8 to 1.36 × 10−8/site/generation (19–21). When considering the average present-day human generation time of 29 y, this results in rates ranging from 0.33 to 0.47 × 10−9/site/year.

Unfortunately, estimates of mutation rates per generation do not yet exist for apes. However, if we assume that they are similar to those in humans, we can apply the rates of 0.97 × 10−8 to 1.36 × 10−8/site/generation to the generation time of 19 y derived from the gorilla, which yields mutation rates of 0.51–0.72 × 10−9/site/year. Similarly, application of the human mutation rate per generation to the chimpanzee with a generation time of 25 y yields mutation rates of 0.39–0.54 × 10−9/site/year. Because the gorilla has the shortest and the human the longest generation time among the great apes, this suggests that the mutation rate for African apes and humans is between 0.33 × 10−9 and 0.72 × 10−9/site/year.

Species Split Times.

We can use the observed generation times in apes and humans as well as observed mutation rates in human families to recalibrate the previously published split times among the human and ape evolutionary lineages. We assume that the common ancestor at each branch point had a generation time and mutation rate within the range described by the most extreme values of the present-day descendant species (Materials and Methods). Table 2 shows that the resulting estimates are all substantially older than those based on fossil calibrations of mutation rates. For example, we estimate the bonobo and chimpanzee split time at 1.5–2.6 million years, whereas previous estimates put it at less than 1 million years. We estimate the split time between the human and chimpanzee lineages at between 7 and 13 million years, whereas previous estimates range from 4 to 6 million years. We estimate the split between the gorilla lineage and the lineage leading to humans, chimpanzees, and bonobos at 8–19 million years, whereas previous estimates range between 6 and 7 million years.

Table 2.

Original and recalibrated population split times from several recent studies

| Generation times |

New yearly mutation rate |

New split estimate, Ma |

|||||||

| Speciation event | Original yearly mutation rate | Original split estimate, Ma | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Reference |

| HCG | 1.0 × 10e-9 | 5.95 | 19 | 29 | 0.33 | 0.72 | 8.31 | 17.79 | Scally et al. 2012 (8) |

| HCG | 1.0 × 10e-9 | 6.69 | 19 | 29 | 0.33 | 0.72 | 9.35 | 20.00 | Dutheil et al. 2009 (4) |

| HC | 1.0 × 10e-9 | 3.69 | 25 | 29 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 6.78 | 11.03 | Scally et al. 2012 (8) |

| HC | 1.0 × 10e-9 | 4.22 | 25 | 29 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 7.76 | 12.62 | Hobolth et al. 2011 (6) |

| HC | 1.0 × 10e-9 | 4.5 | 25 | 29 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 8.27 | 13.45 | Prüfer et al. 2012 (15) |

| HC | 1.0 × 10e-9 | 4.38 | 25 | 29 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 8.05 | 13.09 | Dutheil et al. 2009 (4) |

| BC | 1.0 × 10e-9 | 0.99 | 25 | 25 | 0.39 | 0.54 | 1.82 | 2.55 | Prüfer et al. 2012 (15) |

| BC | 1.0 × 10e-9 | 0.79–0.92 | 25 | 25 | 0.39 | 0.54 | 1.45–1.69 | 2.04–2.37 | Becquet and Przeworski 2007 (13) |

| wG–eG | 0.96 × 10e-9 | 0.9–1.6 | 19 | 19 | 0.51 | 0.72 | 1.20–2.13 | 1.69–3.01 | Thalmann et al. 2007 (27) |

| wG–eG | 1.33 × 10e-9 | 0.92 | 19 | 19 | 0.51 | 0.72 | 1.29 | 1.80 | Becquet and Przeworski 2007 (13) |

BC, bonobo–chimpanzee split; HC, human–chimpanzee split; HCG, human–chimpanzee–gorilla split; wG–eG, western gorilla–eastern gorilla split.

Discussion

By using direct observations of generation times in gorillas and chimpanzees and rates of mutation per generation from direct observation of mutations in human families, we estimate the species split times of humans and apes without relying on external fossil calibration points. At 7–13 Ma our estimate of the chimpanzee–human split time is earlier than those previously derived from molecular dating using fossil calibration points but similar to the range of 6.5–10 Ma suggested by the fossil record (30).

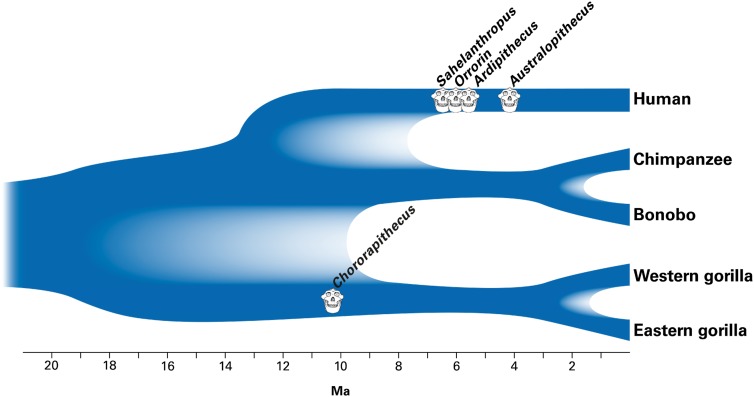

Whereas the earliest fossil universally accepted to belong to the lineage leading to present-day humans rather than to chimpanzees, Australopithecus anamensis, is 4.2 Ma (31) and thus reconcilable with a molecularly inferred human–chimpanzee split time as recent as 5 Ma, the attribution of late Miocene (5–7 Ma) fossils to the hominin lineage has posed a problem. Our estimates make it possible to reconcile attribution of fossils such as Ardipithecus kaddaba (5.2–5.8 Ma) (32), Orrorin tugenensis (6 Ma) (9), and Sahelanthropus tchadensis (6–7 Ma) (10) to the hominin lineage with speciation times inferred from genetic evidence (Fig. 1). However, our estimates cannot address the controversy of whether specimens such as these truly belong to the lineage leading to present-day humans or to other, closely related lineages (11).

Fig. 1.

Diagram illustrating the branching pattern and timing of the splits between humans, chimpanzees, bonobos, western gorillas, and eastern gorillas. The paler shading indicates the range of split times inferred in this study. Cartoon skulls indicate approximate age of the indicated fossil remains, but do not imply that these fossils were necessarily on those ancestral lineages or that entire crania actually exist for these forms.

For the deeper time period of 7–13 Ma, the fossil record is even more limited and difficult to interpret (31, 33). Fossils from between 8 and 11 Ma in Africa include mainly Gorilla-sized forms, such as Samburupithecus (34), Nakalipithecus (35), and Chororapithecus, the last of which is dated to 10–10.5 Ma and suggested to represent an early member of the gorilla clade (36). Our estimate of 8–19 Ma for the split of the gorilla lineage from the human–chimpanzee ancestor would be largely consistent with the attribution of such forms to the gorilla lineage.

Even though not quantified here, our results also significantly push back the date of the split between orangutans and African apes. Paleontological data (e.g., ref. 37) have been combined with genetic data (38) to suggest that this split occurred outside of Africa, with a later “Back to Africa” migration of the common ancestor of African apes. The purported “early great ape” Pierolapithecus catalaunicus from Spain, dating to about 12.5–13 Ma (39), and the presence of numerous derived African ape traits in Late Middle Miocene fossils from Europe such as Rudapithecus and Hispanopithecus fit well with this hypothesis. A split between African apes and orangutans that predates 15 Ma would challenge this model and would either put these fossils on the orangutan lineage or place them as unrelated to present-day great apes.

For more recent periods of hominin evolution, the more recent dates provided here for the human–chimpanzee split resolve an apparent contradiction between genetic and paleontological data. Using a chimpanzee/human split of 5.6–8.3 Ma for calibration, analyses of the Neanderthal genome indicated a population split between present-day humans and Neanderthals at 270–440 ka (40). This date appears to conflict with fossil evidence tracing the emergence of Neanderthal morphological characters over the course of the Middle Pleistocene in Europe (41). The earliest evidence for Neanderthal traits was proposed to date to 600 +∞/−66 ka at the Sima de Los Huesos (Atapuerca, Spain) (42), thus predating the genetically estimated population divergence times, but this date has been disputed on the basis of both the apparent conflict with the genetic data and on stratigraphic grounds (43). However, even if the early dates for Sima are disregarded, it is clear that fossils from oxygen isotope stage 11 (around 400 ka), such as the Swanscombe cranium, already show clear Neanderthal traits (44). Using the new human–chimpanzee split estimate and assuming generation times between 25 and 29 y would push back the human/Neanderthal split to 423,000–781,000 y, resolving this apparent conflict.

Recent attempts to model uncertainty in the fossil data used for molecular calibration also suggest earlier split times in the evolutionary history of apes with estimates of 6–10 Ma for the human–chimpanzee divergence and 7–12 Ma for the divergence of the gorilla (18). Our estimates of divergence dates have the advantage that they avoid fossil calibration points. However, it is possible that other aspects of our analysis may lead to unreliable split time inferences. First, because of the limited availability of data from the western gorilla species, we make the assumption that the average generation interval of mountain gorillas is applicable to both present-day species of the Gorilla genus. Although reliant primarily upon herbaceous vegetation, western gorillas also eat fruit much of the year, whereas fruit is nearly absent from the mountain gorilla habitat (45). More folivorous anthropoid primates are known to mature more quickly than similarly sized nonfolivorous primates (46), and indeed limited data from western gorillas suggest that females and males attain adulthood 2 and 3 y later, respectively, than the more folivorous mountain gorilla (47). This implies that the generation time in western gorillas may be on the order of 21 y, in contrast to the 19 y used here for gorilla generation time. However, because 19 is the shortest generation time observed among present-day mountain gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans, our use of this value is more conservative and simply contributes to a slightly broader range for the inferred split time for the divergence of the gorilla lineage from that leading to humans and chimpanzees, as well as to a broader range for the split time between the two gorilla species. As with western gorillas, parentage data for calculation of generation times in bonobos are lacking. However, neither extensive dietary differences between bonobos and chimpanzees nor substantial differences in developmental timing are apparent for these species and it is also relevant that we found no consistent differences in generation times between chimpanzees from western and eastern Africa. With regard to humans, highly similar estimates of generation time were obtained from demographic analysis of a large sample of less- and more-developed countries, a large sample of hunter–gatherer societies, and direct analysis of genealogies (22). In sum, except for the gorillas where marked ecological differences may contribute to a small degree of variation in generation time within the genus, the generation times used here seem reliable estimates for present-day great apes and humans.

A further notable assumption of our work is that the generation times calculated for present-day humans and great apes are valid proxies for their ancestors. It was recently suggested that a slowdown in mutation rate concomitant with an increase in body sizes and generation times has occurred in these lineages (8). However, there is an extraordinary diversity of ape body sizes in the fossil record since the Miocene (24 to 5 Ma) and it is difficult to know which ones may represent ancestors of present-day apes and humans (32). Even if fossil evidence strongly suggested an increase in the size of the ancestors of present-day apes and humans in the past, it is not clear that body mass is a good correlate of life history parameters related to generation time (48). Although our number of data points is necessarily limited, we found no correlation between mass and generation time in present-day apes and humans, and the notably short generation time for the relatively large mountain gorilla is consistent with the expectation that highly folivorous (46) as well as more terrestrial (49) species are expected to reproduce earlier than more frugivorous, arboreal primates. In accordance with the importance of diet and habitat use in influencing life-history parameters, it has been suggested that chimpanzees and orangutans represent the most appropriate living models for the potential life history variables of archaic hominins, and that the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees exhibited a slow life history similar to that of present-day chimpanzees (50). Skeletal and dental analyses suggest that early hominins had growth patterns like those of present-day great apes, whereas Homo erectus and Neanderthals evolved slower development, but not to the extent seen in present-day humans (51, 52). Given the information available at this time, we suggest that the use of the ranges of the observed generation times in the present-day species, including the extremes represented by gorillas (with their comparatively fast life history and consequently short generation time) and humans (with their comparatively slow life history and consequently long generation time), results in conservatively broad estimates of hominid mutation rates and split times as shown (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Specifically, if we alternatively consider the human generation time of 29 y to be a recent phenomenon, and consider the chimpanzee generation time of 25 y to characterize the vast majority of evolution since the split between the gorilla and the chimpanzee/human lineages, we would infer the date of this split at 10.9–17.2 Ma, whereas the split between the lineages leading to chimpanzees and humans would be dated at 6.8–11.6 Ma.

We also note that we explicitly assume that the mutation rates estimated by sequencing members of present-day human families are also applicable to our closest great ape relatives. This assumption, which is based on our close evolutionary relationship and lack of evidence for differences in rates of evolution among the human and African great ape lineages (7, 53), can be explicitly tested in the future by sequencing of great ape family trios. As an additional point for future consideration, we note that the original publications, which provide the population split times that we recalibrate here, use various approaches for filtering the data analyzed, for example, exclusion of repetitive sequences or highly mutable sites. Refinements of our population split time estimates may involve reexamination of the data, including consideration of different parts of the genome, or different types of substitutions. For example, it will be interesting to compare inferences from substitutions at CpG sites that may accumulate in a time-dependent fashion with other classes of substitutions that may accumulate in a generation-dependent fashion. However, thus far studies have shown that the inclusion or exclusion of CpG sites has little impact on the timing of the human-chimpanzee split (3, 7).

Finally, we note that the estimation of generation times in chimpanzees and gorillas derives from the long-term efforts of researchers who have invested years in habituating the animals to human observation to collect information on their natural behavior and life histories. This study illustrates the value of such approaches in aiding interpretation of genomic data and suggests that continued behavioral study of wild apes, in addition to increased understanding of their behavior and cultures, is necessary to complement genomic studies for a fuller understanding of the evolutionary history of our closest living relatives as well as our own species.

Materials and Methods

Details regarding the analyses can be found in SI Materials and Methods. In brief, we compiled the ages of the genetically confirmed mothers and fathers of offspring born into eight chimpanzee groups and six mountain gorilla groups habituated to human observation. We did not limit our sample to individuals whose ages are exactly known because this would lead to a downward bias in the estimation of the generation length, as older individuals are more likely to have been born before the start of long-term research on a particular group. Instead, we included in our study individuals whose ages were estimated using standard morphological, behavioral, and life history criteria established from known-aged individuals and systematically incorporated estimation of ranges of minimum and maximum birthdates symmetrical about the assigned birthdate.

For the split time estimation, we first took the lowest and highest estimates of mutation rates in human families of 0.97 × 10−8 to 1.36 × 10−8/site/generation and applied the estimated generation times of 19, 25, and 29 y for gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans to arrive at low and high estimates of yearly mutation rates given each of these generation times. For example, the chimpanzee generation time of 25 y yields a rate of 0.39–0.54 × 10−9 mutations/site/year, whereas the human generation time of 29 y yields a rate of 0.33–0.46 × 10−9 mutations/site/year. For each split we then chose lower and upper bounds for the yearly mutation rates based upon the extreme values inferred for the taxa under consideration. For example, we assumed that the generation time of the common ancestor of chimpanzees and humans was between 25 and 29 y, the values for present-day chimpanzees and humans, respectively, and thus used the mutation rates of 0.33 and 0.54 mutations/site/year (Table 2). Similarly, the common ancestor of gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans is assumed to have a generation time between 19 and 29 y and we thus used a correspondingly broader set of mutation rates. We adjusted previously published split times (Table 2) by multiplying with the factor μold/μnew, where μold corresponds to the previously used mutation rate per year and μnew to our upper and lower bounds based on the range of per generation mutation rates and generation intervals appropriate for the split under consideration.

No explicit mutation rate was assumed for the calculation of the split times of Neanderthals and present-day humans in the original publication (41). However, the authors use a range of nuclear divergence times for orangutan–human to arrive at a human–chimpanzee divergence time of 5.6–8.3 million years. To recalibrate the Neanderthal split time, we use the published nuclear divergence of ca. 1.3% between human and chimpanzee (8, 16) to convert these values to a mutation rate per year (corresponding to 1.1–0.7 × 10−9).

Note added in proof.

We wish to draw attention to another paper using an inferred per generation mutation rate to estimate the time of the human and chimpanzee species split without reference to a fossil calibration point (54).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Abraham for laboratory assistance, R. Mundry for assistance with estimation of uncertainties in average parental ages, the three reviewers, W.-H. Li for helpful comments on the manuscript, and the many agencies and governments that support the field research (see SI ACKNOWLEDGMENTS). This project was funded by the Max Planck Society. K.E.L. was supported by a fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1211740109/-/DCSupplemental.

See Commentary on page 15531.

References

- 1.Sarich VM, Wilson AC. Immunological time scale for hominid evolution. Science. 1967;158:1200–1203. doi: 10.1126/science.158.3805.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uzzell T, Pilbeam D. Phyletic divergence dates of hominoid primates: A comparison of fossil and molecular data. Evolution. 1971;25:615–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1971.tb01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burgess R, Yang Z. Estimation of hominoid ancestral population sizes under Bayesian coalescent models incorporating mutation rate variation and sequencing errors. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:1979–1994. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutheil JY, et al. Ancestral population genomics: The coalescent hidden Markov model approach. Genetics. 2009;183:259–274. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.103010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hobolth A, Christensen OF, Mailund T, Schierup MH. Genomic relationships and speciation times of human, chimpanzee, and gorilla inferred from a coalescent hidden Markov model. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hobolth A, Dutheil JY, Hawks J, Schierup MH, Mailund T. Incomplete lineage sorting patterns among human, chimpanzee, and orangutan suggest recent orangutan speciation and widespread selection. Genome Res. 2011;21:349–356. doi: 10.1101/gr.114751.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patterson N, Richter DJ, Gnerre S, Lander ES, Reich D. Genetic evidence for complex speciation of humans and chimpanzees. Nature. 2006;441:1103–1108. doi: 10.1038/nature04789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scally A, et al. Insights into hominid evolution from the gorilla genome sequence. Nature. 2012;483:169–175. doi: 10.1038/nature10842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senut B, et al. First hominid from the Miocene (Lukeino Formation, Kenya) Earth and Planetary Sciences. 2001;332:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunet M, et al. A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa. Nature. 2002;418:145–151. doi: 10.1038/nature00879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood B, Harrison T. The evolutionary context of the first hominins. Nature. 2011;470:347–352. doi: 10.1038/nature09709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glazko GV, Nei M. Estimation of divergence times for major lineages of primate species. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:424–434. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becquet C, Przeworski M. A new approach to estimate parameters of speciation models with application to apes. Genome Res. 2007;17:1505–1519. doi: 10.1101/gr.6409707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caswell JL, et al. Analysis of chimpanzee history based on genome sequence alignments. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prüfer K, et al. The bonobo genome compared with the chimpanzee and human genomes. Nature. 2012;486:527–531. doi: 10.1038/nature11128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:69–87. doi: 10.1038/nature04072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibbs RA, et al. Rhesus Macaque Genome Sequencing and Analysis Consortium Evolutionary and biomedical insights from the rhesus macaque genome. Science. 2007;316:222–234. doi: 10.1126/science.1139247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkinson RD, et al. Dating primate divergences through an integrated analysis of palaeontological and molecular data. Syst Biol. 2011;60:16–31. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roach JC, et al. Analysis of genetic inheritance in a family quartet by whole-genome sequencing. Science. 2010;328:636–639. doi: 10.1126/science.1186802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Awadalla P, et al. Direct measure of the de novo mutation rate in autism and schizophrenia cohorts. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Consortium GP. 1000 Genomes Project Consortium A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fenner JN. Cross-cultural estimation of the human generation interval for use in genetics-based population divergence studies. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2005;128:415–423. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helgason A, Hrafnkelsson B, Gulcher JR, Ward R, Stefánsson K. A populationwide coalescent analysis of Icelandic matrilineal and patrilineal genealogies: Evidence for a faster evolutionary rate of mtDNA lineages than Y chromosomes. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1370–1388. doi: 10.1086/375453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumura S, Forster P. Generation time and effective population size in Polar Eskimos. Proc Biol Sci. 2008;275:1501–1508. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tremblay M, Vézina H. New estimates of intergenerational time intervals for the calculation of age and origins of mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:651–658. doi: 10.1086/302770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Won YJ, Hey J. Divergence population genetics of chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:297–307. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thalmann O, Fischer A, Lankester F, Pääbo S, Vigilant L. The complex evolutionary history of gorillas: Insights from genomic data. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:146–158. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wich SA, et al. Orangutan life history variation. In: Wich SA, Utami Atmoko SS, Mitra Setia T, van Schaik CP, editors. Orangutans: Geographic Variation in Behavioral Ecology and Conservation. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harvey PH, Clutton-Brock TH. Life history variation in primates. Evolution. 1985;39:559–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benton MJ, Donoghue PCJ. Paleontological evidence to date the tree of life. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:26–53. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harrison T. Anthropology. Apes among the tangled branches of human origins. Science. 2010;327:532–534. doi: 10.1126/science.1184703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haile-Selassie Y, Suwa G, White TD. Late Miocene teeth from Middle Awash, Ethiopia, and early hominid dental evolution. Science. 2004;303:1503–1505. doi: 10.1126/science.1092978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernor RL. New apes fill the gap. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19661–19662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710109105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishida H, Pickford M. 1997. A new Late Miocene hominoid from Kenya: Samburupithecus kiptalami gen. et sp. nov. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences Earth and Planetary Science 325:823–829.

- 35.Kunimatsu Y, et al. A new Late Miocene great ape from Kenya and its implications for the origins of African great apes and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19220–19225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706190104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suwa G, Kono RT, Katoh S, Asfaw B, Beyene Y. A new species of great ape from the late Miocene epoch in Ethiopia. Nature. 2007;448:921–924. doi: 10.1038/nature06113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Begun DR, Ward CW, Rose MD. Miocene hominoid evolution and adaptations. In: Begun DR, Ward CW, Rose MD, editors. Function, Phylogeny and Fossils. New York: Plenum; 1997. pp. 389–415. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stewart CB, Disotell TR. Primate evolution: in and out of Africa. Curr Biol. 1998;8:R582–R588. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00367-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moyà-Solà S, Köhler M, Alba DM, Casanovas-Vilar I, Galindo J. Pierolapithecus catalaunicus, a new Middle Miocene great ape from Spain. Science. 2004;306:1339–1344. doi: 10.1126/science.1103094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green RE, et al. A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science. 2010;328:710–722. doi: 10.1126/science.1188021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hublin JJ. Out of Africa: Modern human origins special feature: The origin of Neandertals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16022–16027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904119106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bischoff JL, et al. High-resolution U-series dates from the Sima de los Huesos yields 600 +∞/−66 kyrs: Implications for the evolution of the Neanderthal lineage. J Archaeol Sci. 2007;34:763–770. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Endicott P, Ho SY, Stringer C. Using genetic evidence to evaluate four palaeoanthropological hypotheses for the timing of Neanderthal and modern human origins. J Hum Evol. 2010;59:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stringer CB, Hublin J. New age estimates for the Swanscombe hominid, and their significance for human evolution. J Hum Evol. 1999;37:873–877. doi: 10.1006/jhev.1999.0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rogers ME, et al. Western gorilla diet: A synthesis from six sites. Am J Primatol. 2004;64:173–192. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leigh SR. Ontogenetic correlates of diet in anthropoid primates. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1994;94:499–522. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330940406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Breuer T, Hockemba MB, Olejniczak C, Parnell RJ, Stokes EJ. Physical maturation, life-history classes and age estimates of free-ranging western gorillas—insights from Mbeli Bai, Republic of Congo. Am J Primatol. 2009;71:106–119. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelley J, Schwartz GT. Dental development and life history in living African and Asian apes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1035–1040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906206107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Schaik C, Deaner R. Life history and cognitive evolution in primates. In: de Waal F, Tyack P, editors. Animal Social Complexity: Intelligence, Culture, and Individualized Societies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press; 2003. pp. 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robson SL, Wood B. Hominin life history: Reconstruction and evolution. J Anat. 2008;212:394–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00867.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dean MC, Lucas VS. Dental and skeletal growth in early fossil hominins. Ann Hum Biol. 2009;36:545–561. doi: 10.1080/03014460902956725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith TM, et al. Dental evidence for ontogenetic differences between modern humans and Neanderthals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20923–20928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010906107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen F-C, Li W-H. Genomic divergences between humans and other hominoids and the effective population size of the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:444–456. doi: 10.1086/318206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun , et al. A direct characterization of human mutation based on microsatellites. Nature Genetics. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ng.2398. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.