Abstract

Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PI(4)P) is an important regulator of Golgi function. Metabolic regulation of Golgi PI(4)P requires the lipid phosphatase Sac1 that translocates between endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi membranes. Localization of Sac1 responds to changes in glucose levels, yet the upstream signaling pathways that regulate Sac1 traffic are unknown. Here, we report that mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) Hog1 transmits glucose signals to the Golgi and regulates localization of Sac1. We find that Hog1 is rapidly activated by both glucose starvation and glucose stimulation, which is independent of the well-characterized response to osmotic stress but requires the upstream element Ssk1 and is controlled by Snf1, the yeast homolog of AMP-activated kinase (AMPK). Elimination of either Hog1 or Snf1 slows glucose-induced translocation of Sac1 lipid phosphatase from the Golgi to the ER and thus delays PI(4)P accumulation at the Golgi. We conclude that a novel cross-talk between the HOG pathway and Snf1/AMPK is required for the metabolic control of lipid signaling at the Golgi.

Keywords: Hog1 MAP kinase, Snf1/AMPK, Golgi, phosphoinositides, Sac1, glucose signaling

INTRODUCTION

Cell growth necessitates accumulation of mass and expansion in size. Both processes rely on multiple biosynthetic pathways, but protein translation and delivery of proteins via the secretory pathway are of key importance. Consequently, both protein synthesis and protein trafficking need to be tightly coordinated in a nutrient-specific manner. It is well established that ribosome biogenesis and protein translation are controlled by growth rates (1). Multiple signaling pathways that are involved in this process have been discovered (2,3). In contrast, how flux through the secretory pathway responds to growth is not well understood. Studies in yeast have shown that secretion mutants display severe defects in cell size expansion and cell cycle progression (4,5), but the underlying mechanisms for growth and metabolic control of secretion remain elusive.

Phosphoinositide lipids have emerged as important organelle-specific regulators of membrane trafficking. At the Golgi, PI(4)P plays a pivotal role in lipid dynamics, proper Golgi enzyme distribution and in facilitating anterograde trafficking (6). The levels of Golgi PI(4)P are controlled in a growth-specific manner, which involves the lipid phosphatase Sac1 and PI 4-kinases (7). Sac1 is an evolutionary conserved transmembrane protein that cycles between ER and Golgi compartments and plays important roles at both locations (6). The yeast Sac1 ortholog resides largely at the ER during exponential growth and regulates PI(4)P homeostasis at the interface between plasma membrane and the cortical ER (8). Slowed cell growth in stationary cultures or after acute glucose starvation induces accumulation of Sac1 at the Golgi, which produces a rapid decrease in Golgi PI(4)P and in secretion rates (9). Downregulation of Golgi PI(4)P during starvation is augmented by rapid release of the Golgi-specific PI 4-kinase Pik1 (10,11). Stimulation of starved cells with glucose triggers rapid translocation of Sac1 from the Golgi to the ER and induces reassociation of Pik1 with Golgi membranes, thus restoring overall secretory capacity (9–11). Importantly, this mechanism is conserved in mammals, where Golgi PI(4)P levels are also under strict growth control, which is regulated by mitogens and requires the p38 MAPK pathway (12,13).

Yeast cells prefer glucose as carbon source and respond rapidly and globally to changes in glucose levels (14). However, how glucose signaling regulates Sac1 localization is unknown. Among the most important responses to glucose starvation is the activation of Snf1, the yeast homologue of AMPK (15–17). Snf1 is the catalytic subunit of a heterotrimeric complex required for growth in the absence of glucose and regulates global changes in gene expression to utilize alternate carbon sources (17). In addition, yeast cells have five MAPK cascades that play important roles in regulating the response to environmental stress (18). These pathways can be activated by a plethora of stimuli and many MAPKs respond to growth and metabolic signals (19). Several MAPKs use overlapping upstream activation elements (20). Signaling specificity is controlled by pathway-specific scaffold proteins and cross-pathway inhibition (20). However, how a unique signaling output is triggered by a specific stimulus is still not well understood and how integration of MAPK signaling with other regulatory networks is achieved remains to be resolved. Here we show that a novel cross-talk between Snf1 and the high osmolarity glycerol (HOG) MAPK cascade regulates localization of lipid phosphatase Sac1 at the Golgi.

RESULTS

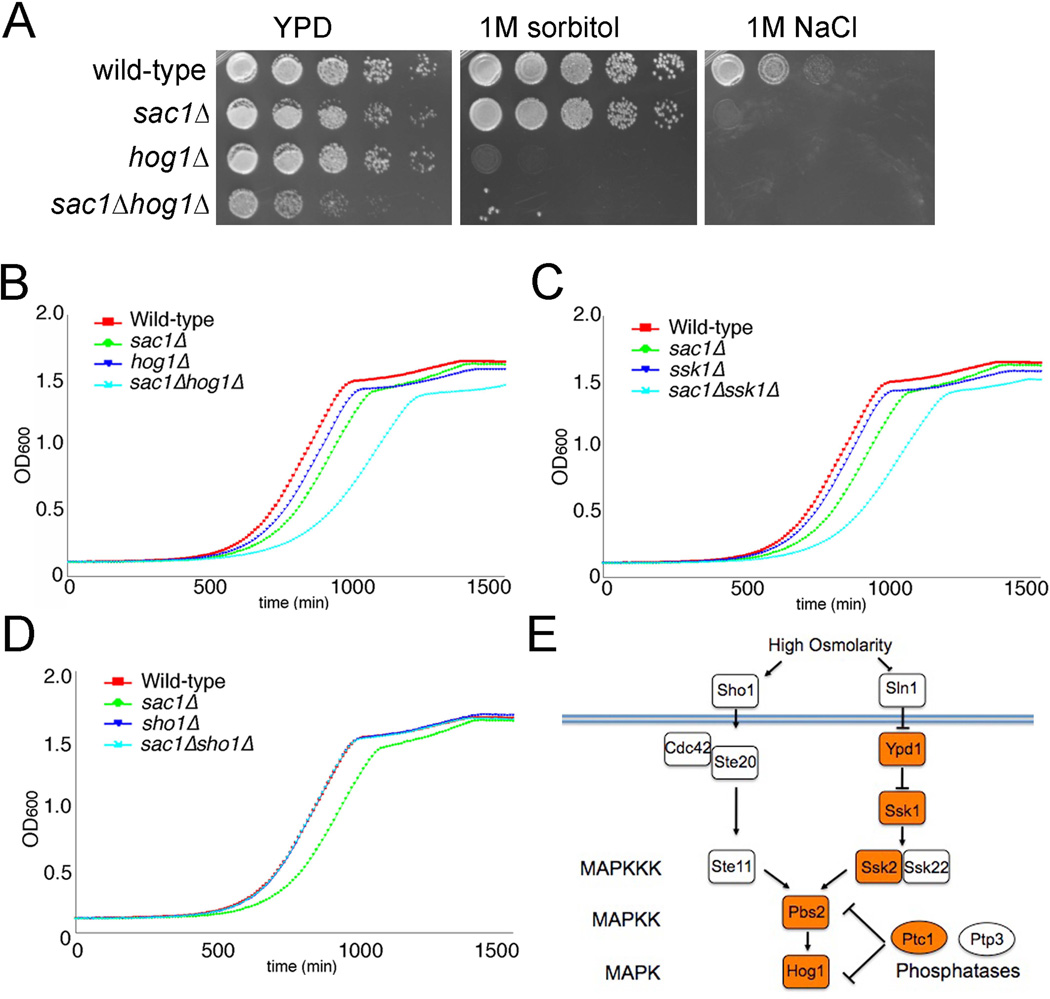

Genetic interactions between sac1Δ and HOG pathway mutants

Strains with a deletion in the SAC1 gene are viable but grow moderately slower on rich media and are sensitive to environmental stress (21,22). Because Sac1 lipid phosphatase is a key enzyme in the metabolic regulation of Golgi function, we reasoned that upstream factors that play a role in the glucose control of Sac1 localization may show genetic interactions with sac1 null alleles. Our genetic analysis yielded multiple interactions between sac1Δ and mutations in genes encoding components of the HOG MAP kinase pathway. Initially, we found that sac1Δ mutants show synthetic interactions with a deletion of the HOG1 gene that encodes an osmosensitive MAPK (Figure 1A,B). sac1Δ cells also exhibit similar sensitivity towards high salt as a hog1Δ strain, but do not share the sensitivity of hog1Δ to general osmotic stress (Figure 1A). At further inspection, we found that sac1Δ mutants display synthetic interactions with branch-specific HOG pathway components (overview in Figure 1E). For example, elimination of SSK1 in a sac1Δ background showed the same growth phenotype as a sac1Δ hog1Δ strain (Figure 1B,C). Ssk1 is an activator of the MAPKKKs Ssk2 and Ssk22 and negatively regulated by the osmosensitive phosphorelay kinases Sln1 and Ypd1 (23). In contrast, deletion of SHO1, which encodes a parallel acting osmosensor (23), showed no genetic interaction with sac1Δ (Figure 1D). In addition, we have previously shown that sac1 mutants show negative genetic interactions with mutations in the PTC1 gene encoding a type 2C protein phosphatase, which dephosphorylates Hog1 (24). Genetic interactions between sac1Δ and HOG pathway mutants were also recorded in global interaction maps (25,26).

Figure 1.

Genetic interactions between sac1 and hog1 mutants. (A) Cells were plated in 5-fold serial dilutions (starting density 107 cells/ml) on rich growth medium (YPD) or on YPD supplemented with 1 M sorbitol or 1 M NaCl. (B-D) Cell growth rates of wild-type cells and HOG pathway mutants in wild-type or sac1Δ backgrounds. Growth rates at 30°C were simultaneously monitored by measuring OD600 every 10 min. (E) Osmosensitive activation of Hog1 via two parallel mechanisms downstream of Sho1 and Sln1. Factors displaying negative genetic interactions with sac1Δ mutants are highlighted in orange.

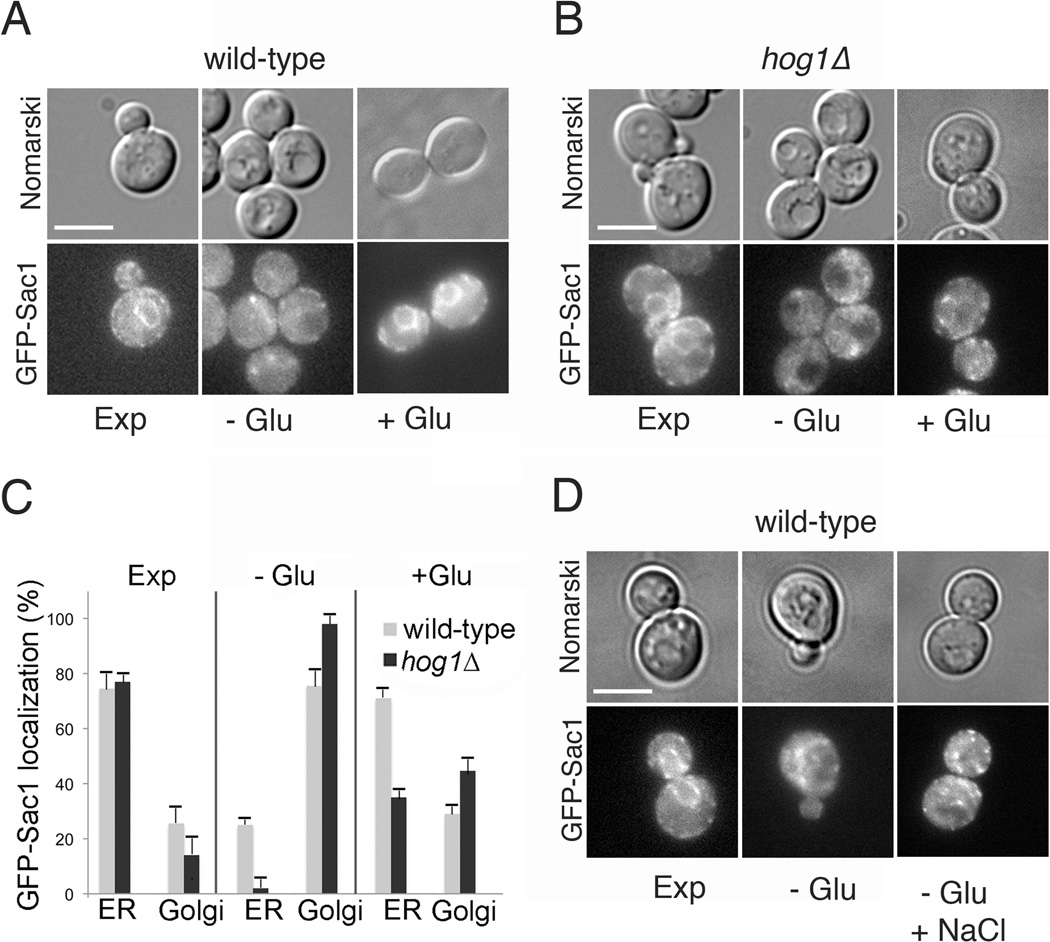

Hog1 MAPK regulates glucose-induced Golgi-to-ER shuttling of Sac1

To determine whether glucose-dependent traffic of Sac1 requires Hog1, we analyzed the localization of GFP-Sac1 under different nutrient conditions in respective mutant strains. Consistent with previous studies, GFP-Sac1 accumulated at the Golgi in wild-type yeast upon glucose starvation and translocated back to the ER when glucose was replenished (Figure 2A,C) (10,9). Starvation-induced translocation of GFP-Sac1 to the Golgi was also observed in a hog1Δ strain, however, these mutants showed significantly impaired retrograde traffic of GFP-Sac1 from the Golgi to the ER after glucose stimulation (Figure 2B,C). Activation of Hog1 by high osmolarity (0.4 M NaCl) failed to induce changes in GFP-Sac1 localization (Figure 2D). These results indicate that Hog1 operates in a novel metabolic regulation pathway that controls Sac1 localization but is independent from its role in osmotic stress.

Figure 2.

Glucose-dependent retrograde trafficking of Sac1 requires Hog1 MAPK. Localization of GFP-Sac1p in wild-type (A) and hog1Δ (B) strains. Strains were exponentially grown in SD-Ura (Exp), starved for glucose for 30 min (−Glu) and subsequently stimulated by glucose addition for 30 min (+Glu). Intracellular localization of GFP-Sac1 was determined by fluorescence microscopy. (C) Quantification of the distribution of GFP-Sac1 between ER and Golgi in wild-type and hog1Δ cells (200 cells/each growth condition; GFP-Sac1, n=3 +/− SD). D) Strains were exponentially grown in SD-Ura (Exp), starved for glucose for 30 min (−Glu) and subsequently subjected to 0.4 M NaCl (−Glu+NaCl). Intracellular localization of GFP-Sac1 was determined by fluorescence microscopy. Scale bars (A, B and D), 4 µm.

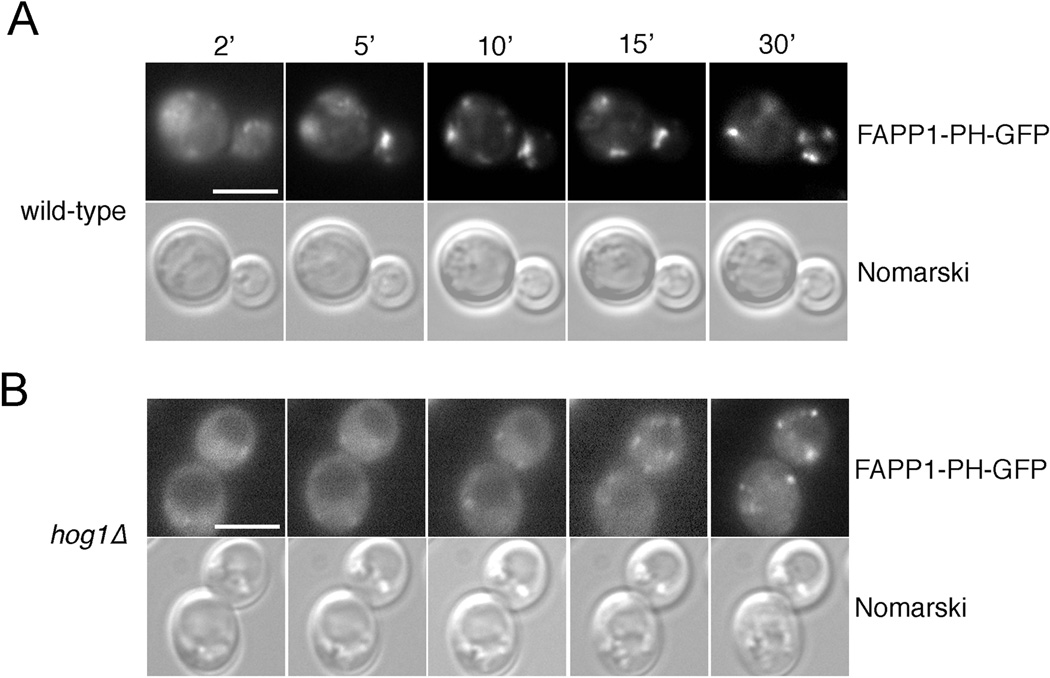

Retrograde trafficking of Sac1 to the ER is an early response to metabolic stimulation of starved yeast cells (9). We reasoned that Hog1 may play a specific role in the glucose-dependent control of Golgi PI(4)P when resting cells re-enter the cell cycle. We therefore monitored Golgi PI(4)P levels during starvation and after glucose stimulation using the GFP-tagged FAPP1-PH probe that binds specifically to PI(4)P. We have shown previously that this probe accumulates at the Golgi in exponentially growing cells but becomes largely cytoplasmic when Golgi PI(4)P is downregulated during starvation (9). In wild-type cells, glucose stimulation induced a rapid accumulation of FAPP1-PH-GFP at punctate Golgi structures within 5–10 minutes (Figure 3A). In contrast, hog1Δ cells displayed significantly slowed Golgi accumulation and persistent cytoplasmic localization of FAPP-PH-GFP after glucose stimulation (Figure 3B). Thus, prolonged Golgi localization of Sac1 in glucose-stimulated hog1Δ strains, causes a delay in the metabolic upregulation of Golgi PI(4)P levels.

Figure 3.

hog1Δ cells show delayed recovery of Golgi PI(4)P after glucose stimulation. Localization of the PI(4)P probe FAPP1-PH-GFP in (A) wild-type and (B) hog1Δ strains. The cells were cultivated in glucose-deprived conditions for 30 min and then stimulated with glucose and examined by fluorescence microscopy at the indicated time points. FAPP1-PH-GFP was expressed from a CEN-based plasmid. Scale bars (A, B), 4 µm

Hog1 MAPK is activated by glucose starvation

Hog1 activation is a specific and well-characterized response to osmotic stress. An indirect link between Hog1 signaling and glucose levels had only been observed in the pathogenic yeast C. albicans, where high glucose enhances resistance to cationic stress (27). We therefore tested whether Hog1 is activated by changes in glucose levels. All metabolic experiments were conducted under iso-osmolaric conditions to rule out Hog1 activation due to changes in osmolarity. We found that glucose starvation induced robust phosphorylation of Hog1 (Figure 4A). Compared to the response to high osmolarity that was induced within 5 min (Figure S1A), phosphorylation of Hog1 in response to glucose starvation was at a maximum at 20–30 min (Figure 4A). Activation of Hog1 by osmotic stress triggers rapid translocation of phosphorylated Hog1 into the nucleus, which is required for transcriptional regulation of osmosensitive genes (28). We monitored localization of Hog1 under different growth conditions using a strain in which the HOG1 gene was replaced by a DNA sequence encoding Hog1-GFP. Treatment of yeast cells with 0.4 M NaCl induced rapid but transient nuclear accumulation of Hog1-GFP (Figure S2), which is an established response to osmotic stress (28). Importantly, transient nuclear localization of Hog1-GFP was also observed after cells were deprived of glucose with a peak nuclear accumulation at 20–30 min of starvation (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Glucose starvation-specific activation of the HOG pathway. (A) Time course of Hog1 phosphorylation in response to glucose starvation. Strains were exponentially grown in SC (Exp) and then starved for glucose (−Glu). Equal amounts of yeast extracts based on total protein content were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Levels of Hog1 and phosphorylated Hog1 (Hog1-P) were examined by immunoblotting. B) Nuclear translocation of Hog1-GFP after glucose starvation. A strain expressing Hog1-GFP from a genomic copy was cultivated in YPD and then starved for glucose. At the indicated times Hog1-GFP localization and nuclear DAPI signals were monitored using fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar (B), 4 µm.

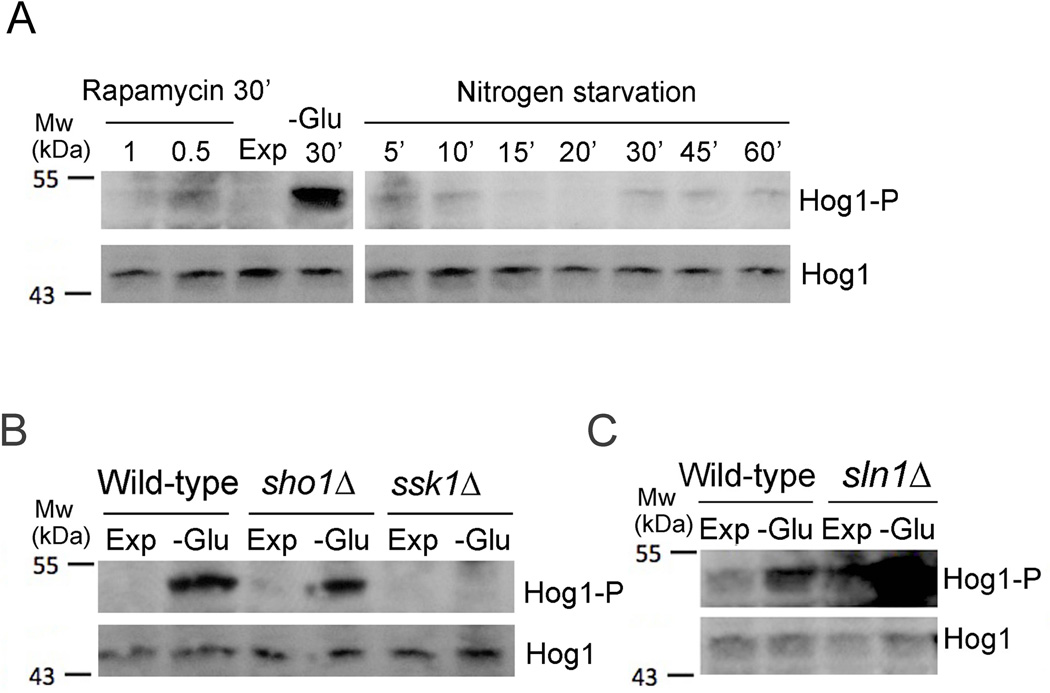

A recent report showed that mitophagy, which is initiated when cells are exposed to prolonged nitrogen starvation, requires Hog1 activation (29). We did not detect significant stimulation of Hog1 phosphorylation when we subjected cells to short-term nitrogen starvation for up to one hour (Figure 5A). Hog1 was also not phosphorylated after treatment with rapamycin (Figure 5A), indicating that rapid metabolic Hog1 activation occurs specifically in response to glucose depletion and is independent of TOR signaling. Nutrient deprivation activates Kss1, a MAP kinase regulating filamentous growth downstream of Ste20 and MAPKKK Ste11. Ste20 and Ste11 also function in the pheromone response pathway and in the Sho1-specific activation branch of Hog1 (19). However, the HOG pathway is not activated by Ste11 during mating and filamentous growth (19) and we found that glucose deprivation-induced Hog1 phosphorylation was independent of Sho1 (Figure 5B). Instead, glucose starvation-induced activation of Hog1 required a functional Ssk1 protein (Figure 5B), which is part of a parallel Hog1 activation pathway (Figure 1E). Deletion of SSK1 did not abrogate Hog1 activation in response to osmotic stress, because of redundancy between both osmosensitive activation pathways (23), (Figure S1A,B).

Figure 5.

Specificity of metabolic Hog1 activation. (A) Hog1 phosphorylation is not induced by nitrogen starvation or rapamycin. Strains were exponentially grown in SC (Exp) and then starved for ammonium sulfate or treated with 0.5 or 1 µg/ml rapamycin. Equal amounts of yeast extracts based on total protein content were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Levels of Hog1 and phosphorylated Hog1 (Hog1-P) were examined by immunoblotting. (B) Starvation- and osmotic stress-induced Hog1 phosphorylation in wild-type, ssk1Δ and sho1Δ strains. Yeast cells were exponentially grown in SC (Exp), subjected to 0.4 M NaCl (+NaCl) or starved for glucose for 30 min (−Glu). Equal amounts of yeast extracts based on total protein content were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Levels of Hog1 and phosphorylated Hog1 (Hog1-P) were examined by immunoblotting. (C) Starvation-induced hyperphosphorylation of Hog1 in a sln1Δ strain. Strains were exponentially grown in SC (Exp) and then starved for glucose for 30 min (−Glu). Equal amounts of yeast extracts based on total protein content were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Levels of Hog1 and phosphorylated Hog1 (Hog1-P) were examined by immunoblotting.

Elimination of the Sln1 osmosensor that negatively regulates Ssk1, causes constitutive activation of the HOG pathway and is lethal in certain yeast strains (30,31). Disruption of the SLN1 gene in our strain background yielded slow growing but viable cells, which allowed us to analyze glucose regulation of Hog1 in the absence of the osmosensing phosphorelay system. sln1Δ cells displayed elevated Hog1 phosphorylation during exponential growth in the presence of glucose and exhibited dramatically enhanced Hog1 phosphorylation during glucose starvation compared to wild-type cells (Figure 5C). These results indicate that the metabolic regulation of Hog1 phosphorylation requires Ssk1 but not the upstream osmosensing mechanism.

Glucose stimulation triggers activation, nuclear accumulation and transient Golgi localization of Hog1

Starvation-induced phosphorylation of Hog1 was rapidly terminated after glucose addition to starved cell but then followed by a second phase of activation (Figure 6A). To ensure that this response is not due to the changes in osmolarity that are induced by adding 2% glucose back to starved cells, these experiments were conducted under iso-osmolar conditions. The glucose stimulation of Hog1 phosphorylation also required the upstream element Ssk1 (Figure 6B). The onset of glucose-induced Hog1 phosphorylation occurred rapidly within a range of 5–10 min after glucose addition (Figure 6A). The time course of Hog1 activation paralleled the timing of Sac1 release from the Golgi and trafficking to the ER, which also takes place at 5–10 min after glucose stimulation (9). To examine changes in Hog1 localization in starved cells after addition of glucose, we used a GFP-tagged Hog1 construct. Time-lapse imaging revealed that Hog1-GFP was largely cytoplasmic immediately after glucose addition but concentrated again in the nucleus within 10–15 minutes (Figure 6C). During the response to glucose stimulation, a certain fraction of Hog1-GFP transiently accumulated at punctate structures that colocalized with the Golgi marker Sec7-RFP (Figure 6C). These results are therefore consistent with a glucose-specific role of Hog1 at the Golgi.

Figure 6.

Glucose stimulation induces nuclear accumulation and transient Golgi localization of Hog1-GFP. Time course of Hog1 phosphorylation in response to glucose starvation and stimulation in wild-type (A) and ssk1Δ cells (B). Strains were exponentially grown in SC (Exp), starved for glucose for 30 min (−Glu) and then stimulated with glucose (+Glu). Equal amounts of yeast extracts based on total protein content were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Levels of Hog1 and phosphorylated Hog1 (Hog1-P) were examined by immunoblotting. (C) Time course of Hog1-GFP localization in response to glucose stimulation. Strains expressing Hog1-GFP (green) and Sec7-RFP (red) from genomic copies were starved for glucose for 30 min and then stimulated with glucose and examined by fluorescence microscopy. Colocalization of Hog1-GFP and Sec7-RFP at punctate structures is indicated with arrows in the merged images. Scale bars (C), 2 µm.

We tested, whether Sac1 itself is phosphorylated in response to Hog1 activation using metabolic labeling with [32P]orthophosphate followed by immunoprecipitation of flag-Sac1 or by phosphoproteomic analysis, but failed to detect phosphorylation of Sac1 or Sac1-derived phosphopeptides at any metabolic condition (data not shown), which suggests that Hog1 phosphorylates an unknown substrate that is involved in glucose control of Sac1 trafficking and localization.

Snf1 regulates the glucose-specific activation of Hog1

Depletion of carbon sources and cellular energy promotes activation of AMPK, an evolutionary conserved enzyme that is represented by the Snf1 kinase complex in yeast (17). The Snf1 complex is required for the response to glucose starvation and regulates global changes in gene expression to utilize alternate carbon sources (17). Although cross-talk between Snf1 and Hog1 has not been described, these pathways have synergistic functions during metabolic and oxidative stress (32–34). When we compared Hog1 phosphorylation in wild-type and snf1Δ strains, we discovered that Snf1 is essential for the glucose starvation-induced control of Hog1 activation (Figure 7A). Surprisingly, Snf1 was also critical for glucose stimulation of Hog1. In snf1Δ cells, we neither detected phosphorylated forms of Hog1 during glucose starvation (Figure 7A,B) nor after glucose stimulation (Figure 7B). In contrast, snf1Δ cells displayed no defects in osmotic stress-induced activation of Hog1 (Figure S1B).

Figure 7.

Snf1 is essential for glucose regulation of Hog1 MAPK and Sac1 traffic (A) Starvation-induced phosphorylation of Hog1 in wild-type and snf1Δ cells. Strains were exponentially grown in SC (Exp) and then starved for glucose for 30 min (−Glu). Equal amounts of yeast extracts based on total protein content were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Levels of Hog1 and phosphorylated Hog1 (Hog1-P) were examined by immunoblotting. (B) Time course of Hog1 phosphorylation in response to glucose starvation and stimulation in wild-type and snf1Δ cells. Strains were exponentially grown in YPD (Exp) and starved for glucose for 30 min (−Glu) and then stimulated with glucose (+Glu). Equal amounts of yeast extracts based on total protein content were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Levels of Hog1 and phosphorylated Hog1 (Hog1-P) were examined by immunoblotting. (C, D) Localization of GFP-Sac1 in wild-type (C) and snf1Δ (D) cells. Strains were exponentially grown in SD-Ura (Exp), starved for glucose for 30 min (−Glu) and then stimulated by glucose addition for 30 min (+Glu). Intracellular localization of GFP-Sac1 was determined by fluorescence microscopy. (E) Quantification of the distribution of GFP-Sac1 between ER and Golgi in wild-type and hog1Δ cells (100 cells/each growth condition; GFP-Sac1, n=3 +/− SD). F) Stimulation of Hog1p phosphorylation via combretastatin-induced Snf1p activation. Strains were exponentially grown in SC (Exp) and then mock-treated or treated with 300 µM combretastatin A4 (CA4). Equal amounts of yeast extracts based on total protein content were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Levels of Hog1 and phosphorylated Hog1 (Hog1-P) were examined by immunoblotting. Scale bars, (C, D), 4 µm.

Because Snf1 was required for both glucose starvation and glucose stimulation-controlled activation of Hog1, we speculated that this kinase is also involved in the metabolic regulation of Sac1 shuttling. Starvation-induced trafficking of GFP-Sac1 from the ER to the Golgi occurred as efficiently in snf1Δ mutant as in a wild-type strain (Figure 7C,E). In contrast, glucose stimulation of retrograde Sac1 translocation to the ER was significantly impaired (Figure 7D,E). This result strongly suggests that Snf1 is required for proper Sac1 traffic after glucose stimulation and that this regulation involves signaling through Ssk1 and Hog1.

To test directly whether activation of Snf1 is sufficient to signal to Hog1, we treated cells with combretastatin A4 (CA4). This reagent binds to the β-subunit of tubulin, but was recently shown to also activate Snf1 in yeast and AMPK in mammals (35). Treatment of exponentially growing wild-type yeast with CA4 induced robust phosphorylation of Hog1, whereas the response to the drug was significantly blunted in a snf1Δ strain (Figure 7F). Starvation-independent activation of Snf1 is therefore sufficient to stimulate Hog1 phosphorylation, which indicates that Snf1 acts as a novel upstream element in the HOG pathway.

DISCUSSION

The HOG MAPK pathway is required for osmosensation and becomes essential for cell survival after osmotic shock (23). This study provides the first direct evidence that HOG activation is also a critical response to acute changes in glucose levels. The metabolic regulation of Hog1 requires components of an upstream multistep phosphorelay system unique to the HOG pathway (23). This relay consists of Sln1, Ypd1 and Ssk1 and is similar to two-component systems that are otherwise largely restricted to prokaryotes (36). Glucose-specific Hog1 phosphorylation requires Ssk1, but is independent of the upstream osmosensing factor Sln1. Whereas osmotic activation of Hog1 can also occur via a parallel pathway that requires the osmosensor Sho1, this activation branch is not involved in the glucose control of Hog1. In contrast, Snf1 AMPK is essential and sufficient for the glucose-specific activation of the HOG pathway. The Snf1-dependent mechanism of HOG activation represents a novel function of the phosphorelay activation branch, perhaps contributing to its preservation during evolution. Similar to osmotic stress, both starvation and glucose stimulation triggered transient accumulation of Hog1 in the nucleus.

Several factors required for glucose-dependent regulation of Hog1 are encoded by genes that display genetic interactions with sac1 mutants. In addition, glucose stimulation of retrograde traffic of Sac1 to the ER requires both Hog1 and Snf1. We therefore hypothesize that Snf1 and the HOG pathway downstream of Ssk1 are important for metabolic regulation of Sac1 localization after growth stimulation with glucose. Because the Sln1 osmosensor is not required for glucose control of Hog1 activation, the crosstalk between the HOG pathway and Snf1 AMPK likely occurs at the level of Ssk1. It seems paradoxical that Snf1 is also required for glucose stimulation of Hog1 activation because glucose addition to starved cell inactivates the Snf1 pathway (14) and more work will be required to determine specifically how the crosstalk between Snf1 and Hog1 is metabolically controlled. Compartmentalization of signaling events may be critical in this mechanism and it is intriguing that a fraction of Hog1 transiently associates with the Golgi after glucose addition. Hog1 has been previously implicated in controlling the localization of the Golgi glycosyltransferase Mnn1 (37) and it is possible that Hog1 has additional roles in regulating Golgi function. A recent report suggests that Hog1 may have novel targets in the cytoplasm as well. Both Tdh3, an isoform of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and Shm2, a cytosolic serine hydroxymethyltransferase, were identified as Hog1 targets in a chemical genetic analysis (38). However, changes in growth or metabolic conditions were not examined in these studies and it remains to be determined whether phosphorylation of these proteins is regulated by glucose. The control of Golgi phosphoinositides by a stress-activated MAP kinase may be evolutionary conserved because p38 MAPK, the closest mammalian homolog of Hog1, has also been implicated in regulating Golgi association of Sac1 (12,13).

The presented results suggest that the HOG pathway plays an important glucose-specific role in coordinating transcriptional programs and biosynthetic pathways--two processes that are under strict control during nutrient limitation. We show that changes in glucose levels induce rapid and transient Hog1 nuclear shuttling. Whether Hog1 has novel glucose-specific nuclear targets remains to be determined, but it is likely that Hog1 is involved in glucose-dependent regulation of gene expression. A recent study showed that Hog1 activity in the nucleus is involved when stationary cells re-enter the mitotic cell cycle (39) indicating that the HOG pathway may play a pivotal role in regulating gene expression when cells exit quiescence. The Hog1-specific control of lipid signaling at the Golgi in response to glucose may be another key element in the stimulation of cell proliferation after starvation because anterograde membrane traffic from the Golgi is a prerequisite for cell growth (5). Glucose-specific control may also be the mechanism for the recently observed basal signaling properties of Hog1 that are independent of osmotic stress (40). Hog1 is therefore a novel component of the regulatory network required for monitoring the availability of glucose, thereby integrating gene transcription, metabolic regulation and membrane trafficking during cell proliferation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, reagents and other procedures

Plasmids and strains used in this study are given in the Supplementary Information (Table SI). Yeast complete media (YPD), Yeast synthetic complete media (SC), and yeast synthetic drop-out media (SD) were prepared as described (41). Complementation studies, plasmid shuffling, gene disruptions and tetrade dissections were performed according to standard genetic techniques (41). Antibodies against Hog1 and phospho-Hog1 (phospho-p38) were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Growth assays

Yeast overnight cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in YPD. The cells were transferred to a microplate optical reader (Sunrise, Tecan) and cultivated at 30°C with continues shaking. Growth curves were generated by automatic measurement of OD600 performed every 10 min.

Generation of GFP and RFP-tagged constructs

To create a GFP-tagged version of Sac1, the coding region of SAC1 was amplified by PCR and cloned into pGK26, which contains the SAC1 promoter next to the coding region of GFP (9). Genomic insertion for expressing Sec7-RFP was described previously (9). To create strains expressing fluorescently-tagged versions Hog1, a region encoding a C-terminal Hog1 fragment from base pair 811–1305 was amplified by PCR and inserted into NotI/XhoI sites of pPM119 containing the coding region for GFP (9). The resulting plasmid was linearized with NotI prior to transformation.

Preparation of yeast cell extracts and immunoblotting

Yeast extracts were prepared as described previously (42). Equal amounts of extract based on total protein content were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide or 5–15% polyacrylamide gradient). Transfer of proteins to nitrocellulose and detection with antibodies were performed according to standard protocols (43).

Hog1 phosphorylation assays

Yeast strains were grown in appropriate synthetic complete media (41) containing 2% glucose (SC+Glu) to early log phase. Cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.1 and grown for three doubling times to an OD600 of 0.8–1.0. Aliquots were either left in SC+Glu or were washed once in SC medium in which 2% glucose was replaced by 2% glycerol or 2% sorbitol (SC-Glu) and further incubated in SC-Glu. Aliquots of cells incubated in SC-Glu were recovered and incubated in SC+Glu. At specific time points aliquots of cells were removed and lysed with glass beads in SDS-PAGE sample buffer as described previously (9). The levels of Hog1 and phospho-Hog1 were analyzed after SDS-PAGE by Western blotting using specific antisera.

GFP-Sac1 localization assays

Yeast strains expressing GFP-Sac1 variants were grown in SD-Ura media (41) containing 2% glucose (SD-Ura+Glu) to early log phase. Cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.1 and grown for three doubling times to an OD600 of 0.8–1.0. Aliquots were either left in SD-Ura+Glu or were washed once in SD-Ura in which 2% glucose was replace by 2% sorbitol (SD-Ura-Glu) and incubated for 30 min in SD-Ura-Glu. Aliquots of cells incubated in SD-Ura-Glu were recovered and incubated in SD-Ura+Glu for 30 min. Localization of GFP-Sac1 in each aliquot was monitored by fluorescence microscopy. The localization phenotypes were quantified by counting at least 100–200 cells per aliquot. All shuttling experiments were repeated three times for statistical data analysis.

Fluorescence microscopy

Cells were grown in appropriate selective media to early log phase or as indicated in the figure legends. For DAPI staining of live yeast cells, overnight cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.2 in SC media (35) supplemented with 1µg/ml of DAPI and cultivated for two doubling times. GFP, RFP and DAPI signals in living yeast cells were viewed using Nikon microscope (model E800) equipped with a Plan-Apo 100x/1.4 oil objective and a Photometrics Coolsnap HQ camera. Images were analyzed using Metamorph software (Universal Imaging Corporation).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank T. Nicolson for comments on the manuscript. J.M.F. was supported by the Partnerships in Scientific Inquiry program at OHSU. This work was funded by National Institute of Health grants GM071569 and GM084088 (to P.M).

REFERENCES

- 1.Mager WH, Planta RJ Biochemisch Laboratorium VUATN. Coordinate expression of ribosomal protein genes in yeast as a function of cellular growth rate. Mol Cell Biochem. 1991;104(1–2):181–187. doi: 10.1007/BF00229818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmelzle T, Hall MN. Tor, a central controller of cell growth. Cell. 2000;103:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jorgensen P, Rupes I, Sharom JR, Schneper L, Broach JR, Tyers M. A dynamic transcriptional network communicates growth potential to ribosome synthesis and critical cell size. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2491–2505. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novick P, Schekman R. Secretion and cell-surface growth are blocked in a temperature-sensitive mutant of saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:1858–1862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anastasia SD, Nguyen DL, Thai V, Meloy M, Macdonough T, Kellogg DR. A link between mitotic entry and membrane growth suggests a novel model for cell size control. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:89–104. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayinger P. Regulation of golgi function via phosphoinositide lipids. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:793–800. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham TR, Burd CG. Coordination of golgi functions by phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stefan CJ, Manford AG, Baird D, Yamada-Hanff J, Mao Y, Emr SD. Osh proteins regulate phosphoinositide metabolism at er-plasma membrane contact sites. Cell. 2011;144:389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faulhammer F, Konrad G, Brankatschk B, Tahirovic S, Knodler A, Mayinger P. Cell growth-dependent coordination of lipid signaling and glycosylation is mediated by interactions between sac1p and dpm1p. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:185–191. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faulhammer F, Kanjilal-Kolar S, Knodler A, Lo J, Lee Y, Konrad G, Mayinger P. Growth control of golgi phosphoinositides by reciprocal localization of sac1 lipid phosphatase and pik1 4-kinase. Traffic. 2007;8:1554–1567. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demmel L, Beck M, Klose C, Schlaitz AL, Gloor Y, Hsu PP, Havlis J, Shevchenko A, Krause E, Kalaidzidis Y, Walch-Solimena C. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the golgi phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase pik1 is regulated by 14-3-3 proteins and coordinates golgi function with cell growth. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1046–1061. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blagoveshchenskaya A, Cheong FY, Rohde HM, Glover G, Knodler A, Nicolson T, Boehmelt G, Mayinger P. Integration of golgi trafficking and growth factor signaling by the lipid phosphatase sac1. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:803–812. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheong FY, Sharma V, Blagoveshchenskaya A, Oorschot VM, Brankatschk B, Klumperman J, Freeze HH, Mayinger P. Spatial regulation of golgi phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate is required for enzyme localization and glycosylation fidelity. Traffic. 2010;11:1180–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaman S, Lippman SI, Zhao X, Broach JR. How saccharomyces responds to nutrients. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:27–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celenza JL, Carlson M. Cloning and genetic mapping of snf1, a gene required for expression of glucose-repressible genes in saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:49–53. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woods A, Munday MR, Scott J, Yang X, Carlson M, Carling D. Yeast snf1 is functionally related to mammalian amp-activated protein kinase and regulates acetyl-coa carboxylase in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19509–19515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedbacker K, Carlson M. Snf1/ampk pathways in yeast. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2408–2420. doi: 10.2741/2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gustin MC, Albertyn J, Alexander M, Davenport K. Map kinase pathways in the yeast saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1264–1300. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1264-1300.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qi M, Elion EA. Map kinase pathways. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3569–3572. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saito H. Regulation of cross-talk in yeast mapk signaling pathways. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13:677–683. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tahirovic S, Schorr M, Then A, Berger J, Schwarz H, Mayinger P. Role for lipid signaling and the cell integrity map kinase cascade in yeast septum biogenesis. Curr Genet. 2003;43:71–78. doi: 10.1007/s00294-003-0380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schorr M, Then A, Tahirovic S, Hug N, Mayinger P. The phosphoinositide phosphatase sac1p controls trafficking of the yeast chs3p chitin synthase. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1421–1426. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00449-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Rourke SM, Herskowitz I, O'Shea EK. Yeast go the whole hog for the hyperosmotic response. Trends Genet. 2002;18:405–412. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02723-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tahirovic S, Schorr M, Mayinger P. Regulation of intracellular phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate by the sac1 lipid phosphatase. Traffic. 2005;6:116–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiedler D, Braberg H, Mehta M, Chechik G, Cagney G, Mukherjee P, Silva AC, Shales M, Collins SR, van Wageningen S, Kemmeren P, Holstege FC, Weissman JS, Keogh MC, Koller D, Shokat KM, Krogan NJ. Functional organization of the s. Cerevisiae phosphorylation network. Cell. 2009;136:952–963. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costanzo M, Baryshnikova A, Bellay J, Kim Y, Spear ED, Sevier CS, Ding H, Koh JL, Toufighi K, Mostafavi S, Prinz J, St Onge RP, VanderSluis B, Makhnevych T, Vizeacoumar FJ, Alizadeh S, Bahr S, Brost RL, Chen Y, Cokol M, Deshpande R, Li Z, Lin ZY, Liang W, Marback M, Paw J, San Luis BJ, Shuteriqi E, Tong AH, van Dyk N, Wallace IM, Whitney JA, Weirauch MT, Zhong G, Zhu H, Houry WA, Brudno M, Ragibizadeh S, Papp B, Pal C, Roth FP, Giaever G, Nislow C, Troyanskaya OG, Bussey H, Bader GD, Gingras AC, Morris QD, Kim PM, Kaiser CA, Myers CL, Andrews BJ, Boone C. The genetic landscape of a cell. Science. 2010;327:425–431. doi: 10.1126/science.1180823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodaki A, Bohovych IM, Enjalbert B, Young T, Odds FC, Gow NA, Brown AJ. Glucose promotes stress resistance in the fungal pathogen candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:4845–4855. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reiser V, Ruis H, Ammerer G. Kinase activity-dependent nuclear export opposes stress-induced nuclear accumulation and retention of hog1 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the budding yeast saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:1147–1161. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mao K, Wang K, Zhao M, Xu T, Klionsky DJ. Two mapk-signaling pathways are required for mitophagy in saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:755–767. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ota IM, Varshavsky A. A yeast protein similar to bacterial two-component regulators. Science. 1993;262:566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.8211183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maeda T, Wurgler-Murphy SM, Saito H. A two-component system that regulates an osmosensing map kinase cascade in yeast. Nature. 1994;369:242–245. doi: 10.1038/369242a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsujimoto Y, Izawa S, Inoue Y. Cooperative regulation of dog2, encoding 2-deoxyglucose-6-phosphate phosphatase, by snf1 kinase and the high-osmolarity glycerol-mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in stress responses of saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5121–5126. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.18.5121-5126.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomas-Cobos L, Casadome L, Mas G, Sanz P, Posas F. Expression of the hxt1 low affinity glucose transporter requires the coordinated activities of the hog and glucose signalling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22010–22019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nandy SK, Jouhten P, Nielsen J. Reconstruction of the yeast protein-protein interaction network involved in nutrient sensing and global metabolic regulation. BMC Syst Biol. 2010;4:68. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coccetti P, Montano G, Lombardo A, Tripodi F, Orsini F, Pagliarin R. Synthesis and biological evaluation of combretastatin analogs as cell cycle inhibitors of the g1 to s transition in saccharomyces cerevisiae. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:2780–2784. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stock AM, Robinson VL, Goudreau PN. Two-component signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:183–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reynolds TB, Hopkins BD, Lyons MR, Graham TR. The high osmolarity glycerol response (hog) map kinase pathway controls localization of a yeast golgi glycosyltransferase. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:935–946. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.4.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim S, Shah K. Dissecting yeast hog1 map kinase pathway using a chemical genetic approach. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1209–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Escote X, Miranda M, Rodriguez-Porrata B, Mas A, Cordero R, Posas F, Vendrell J. The stress-activated protein kinase hog1 develops a critical role after resting state. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:423–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macia J, Regot S, Peeters T, Conde N, Sole R, Posas F. Dynamic signaling in the hog1 mapk pathway relies on high basal signal transduction. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra13. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams A, Gottschling D, Stearns T. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayinger P, Meyer DI. An atp transporter is required for protein translocation into the yeast endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 1993;12:659–666. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.