Summary

The C-propeptides of fibrillar procollagens play crucial roles in tissue growth and repair by controlling both the intracellular assembly of procollagen molecules and the extracellular assembly of collagen fibrils. Mutations in the C-propeptides are associated with several, often lethal, genetic disorders affecting bone, cartilage, blood vessels and skin. Here we report the first crystal structure of a C-propeptide domain, from human procollagen III. It reveals an exquisite structural mechanism of chain recognition during intracellular trimerization of the procollagen molecule. It also gives insights into why some types of collagen consist of three identical polypeptide chains while others do not. Finally, the data show striking correlations between the sites of numerous disease-related mutations in different C-propeptide domains and the degree of phenotype severity. The results have broad implications for understanding genetic disorders of connective tissues and designing new therapeutic strategies.

Numerous, often lethal, genetic disorders of bone, cartilage, blood vessels and skin have been linked to defects in the assembly of collagens1. In humans, among the 28 different genetic types of collagen2, those that form the banded fibrils seen in tissues (types I, II, III, V, XI) are synthesized in soluble precursor form, procollagen (~ 450 kDa), with large N- and C-terminal propeptide extensions (50 kDa and 90 kDa, respectively; Fig. 1a). Inside the cell, assembly of the procollagen molecule from its three polypeptide chains is initiated by association of the C-propeptide domains (otherwise known as COLFI domains; see smart.embl-heidelberg.de or pfam.sanger.ac.uk), this being a crucial step in the nucleation and folding of these long rod-like molecules3-5. While overall sequence homology among C-propeptide domains from different fibrillar procollagens is strong6 (46 % identity among human procollagen types I-III; Fig. 1b), Lees et al7 identified a highly variable discontinuous sequence of 15 amino acids, called the chain recognition sequence, that seems to confer chain selectivity during assembly of different collagen types within the same cell. This selectivity results in either homotrimers (procollagens II and III) or heterotrimers (procollagens I, V and XI), each with the correct chain composition (e.g. [proα1(I)]2proα2(I) for procollagen I or [proα1(III)]3 for procollagen III), thus preventing the formation of non-physiological trimers such as [proα2(I)]3 or hybrid molecules consisting of chains from different collagen types.

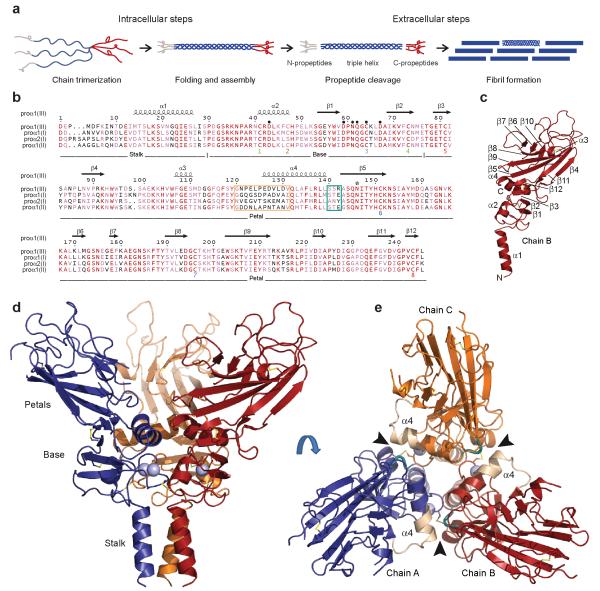

Figure 1.

Structure of the C-propeptide trimer of human procollagen III. (a) The C-propeptides control both intracellular assembly of procollagen molecules and extracellular assembly of collagen fibrils. Adapted from Myllyharju and Kivirikko33, with permission. (b) Sequence alignment of the C-propeptides of the major human fibrillar procollagen chains. Identical residues are shown in red, with similar residues in pink. Different structural regions and secondary structure elements are indicated, as well as Cys residues (identified as Cys 1 to 8) and intra-chain disulfide bonds shown as color-matched pairs. Residues involved in Ca2+ coordination are indicated by ● and the single N-linked glycosylation site by * (note Asn146 was mutated to Gln in the structure presented here). The long (12 residue) and short (3 residue) stretches of the discontinuous 15 residue chain recognition sequence are outlined in wheat and deep teal color, respectively. Numbering refers to the C-propeptides of the proα1(III) chain. Sequence alignments and rendering done using CLUSTALW34 and ESPript35, respectively. (c) Identification of secondary structure elements in chain B of the trimer. N- and C-termini are also indicated. (d) Structure at 3.5Å resolution showing the stalk, base and petal regions. (e) Structure shown in (c) rotated by 90° and viewed from the top showing the three petals, the triangle of helices 4 and the interaction interface (arrowheads) involving the long (wheat) and short (deep teal) stretches of the chain recognition sequence. Note that residues 1-13 of the C-propeptide were not visible in the structure.

In addition to its intracellular function in molecular trimerization, another crucial role for the C-propeptide domain is to confer solubility to the collagen molecule, thereby controlling fibril formation8,9 (Fig. 1a). Thus, outside the cell or during intracellular transport and secretion, C-propeptide trimers are released (in the case of procollagens I-III) by BMP-1/tolloid-like proteinases10, this being the rate limiting step in collagen fibril assembly. C-propeptide cleavage is further regulated by procollagen C-proteinase enhancer proteins, which bind specifically to the C-propeptides11. Since excess collagen deposition is the hallmark of several fibrotic disorders (affecting heart, lung, liver, etc) which together are leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide12, structural data on the C-propeptide trimer are clearly essential for the development of new therapeutic strategies. Free C-propeptide trimers are also involved in feedback inhibition of collagen synthesis13,14, via interaction with integrins15, as well as in biomineralisation16-18 and in angiogenesis and tumor progression19,20. Despite their obvious importance however, and many years of research5, the three-dimensional structures of C-propeptide domains, present throughout the Metazoa6, have until now remained elusive.

Here we set out to determine the first structure of a C-propeptide domain, that of human procollagen III. The results reveal the structural mechanism by which the three polypeptide chains specifically recognize each other during assembly of the procollagen molecule. They also give unexpected insights into why some types of collagen are homotrimers while others are heterotrimers. Finally, mapping on to the structure of numerous mutation sites associated with heritable connective tissue disorders affecting bone, cartilage blood vessels and skin shows striking correlations between three-dimensional localization and phenotype severity.

RESULTS

Structure of the procollagen III C-propeptide trimer

Figs. 1c,d,e show the three-dimensional structure of the C-propeptide trimer from human procollagen III. It has the overall shape of a flower, consisting of a stalk, a base and three petals. Three structures were determined, by X-ray crystallography, at 3.5Å, 2.2Å and 1.7Å resolution (Table 1). The 3.5Å structure is the most complete (see Figs. 1c,d,e; also stereo version and electron density map in Supplementary Figs. 1a,b), showing the stalk, the base and the petals. The stalk comprises the amino acid sequence up to the first conserved proline residue (Pro30; Fig. 1b). It includes an α-helical coiled-coil21 (helix 1), corresponding to the relatively highly conserved region from residues 12 to 27 (Fig. 1b).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Form I (SeMet)* | Form II (native) | Form III (native) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P321 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 83.9, 89.3, 101.5 | 76.5, 90.4, 102.4 | 86.1, 86.1, 73.0 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 120 |

| Peak | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 101.5-2.2 (2.27- 2.21) |

61.3-1.7 (1.73- 1.68) |

43.0-3.5 (3.69- 3.50) |

| Rsym (%) | 11.3 (81.0) | 8.6 (27.7) | 9.8 (63.9) |

| I / бI | 19.4 (4.0) | 4.7 (2.2) | 10.7 (3.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 96.2 (95.6) | 99.7 (99.8) |

| Redundancy | 14.4 (14.7) | 3.5 (3.6) | 7.9 (8.2) |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 101.5-2.2 | 61.3-1.7 | 43-3.5 |

| No. of unique reflections | 38676 | 78019 | 4149 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 20.1/23.7 | 16.3/21.3 | 28.5/33.7 |

| No. atoms Protein | 5056 | 5026 | 1553 |

| Ca2+ ion | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Water | 179 | 398 | 1 |

| B-factors | |||

| Protein (A/B/C) | 31.7/27.7/43.1 | 21.1/22.1/21.5 | 70.8 |

| Ligand/Ca2+ | 40/21.3 | 36/15.4 | n.a./47.0 |

| Water | 29.8 | 27.6 | 61.0 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.010 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.4 |

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

Four selenomethionine residues were identified in each polypeptide chain. This compares with a total of six methionines in the amino acid sequence, the remaining two being present in the stalk region which was not resolved in forms I and II. These data compare with approximately five selenomethionine residues per chain detected by mass spectrometry36.

More details (though not the stalk) are seen in the 2.2Å and 1.7Å structures (the latter shown in stereo view in Supplementary Figs. 1c,d). The base (residues 30-76; Fig. 1b) consists of a disulfide bonded ring connecting all three chains (Supplementary Figs. 1e,f), and includes the first four of the eight cysteines present in each chain. Among the three regions of the molecule, the base is the most highly conserved (60 % sequence identity; Fig. 1b). For each chain, this region begins with an almost perfectly conserved 12 residue loop ending in Cys41, followed by a short α-helix (helix 2) extending up to Cys47. There follow a short loop and a two-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet (strands 1 and 2). The loop connecting strands 1 and 2 (residues 59-68) includes a bound Ca2+ ion (Supplementary Figs. 1g,h), as previously suggested based on sequence analysis22. The structure reveals that this ion plays an essential role, stabilizing not only the base region but also the trimer, by coordinating to a water molecule that is, in turn, hydrogen bonded to Asp43 in a neighboring chain. One of the Ca2+ ligands is Cys64, which further stabilizes the trimer by forming the only inter-chain disulfide bond, with an adjacent Cys47. In contrast, Cys41 and Cys73 form an intra-chain disulfide bond, thus settling the long standing debate3 about the roles of these first four cysteines.

Though the base and the petals together form a single entity in the three-dimensional structure, it is convenient to describe the latter as starting between Cys73 and Cys81 (Fig. 1b). On the outer face of each petal (Fig. 1b), there is a twisted anti-parallel β-sheet, comprising seven β-strands (3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11 and 12), which is continuous with that formed by strands 1 and 2 in the base. Notably, strand 12 (at the C-terminus), containing Cys243, inserts between strands 3 and 5 and forms an intra-chain disulfide bond with Cys81 on strand 3. The C-terminal residue (Leu245) is therefore adjacent to the base as well as to residues involved in chain selectivity (see below). On the inner face of each petal (Fig. 1c), there is a short anti-parallel β-sheet (strands 6, 7 and 10), as well as a short α-helix (helix 3), and the inner and outer faces are connected by an intra-chain disulfide bond between Cys151 and Cys196. Further down on the inner face, at the junction with the base, is a relatively long α-helix (helix 4). Almost half the interactions involving the petals implicate residues in and around helix 4 (Supplementary Fig. 2; also see below), with the three helices 4 from the three subunits forming a triangle sitting on the base (Fig. 1e).

Structural mechanism of chain recognition

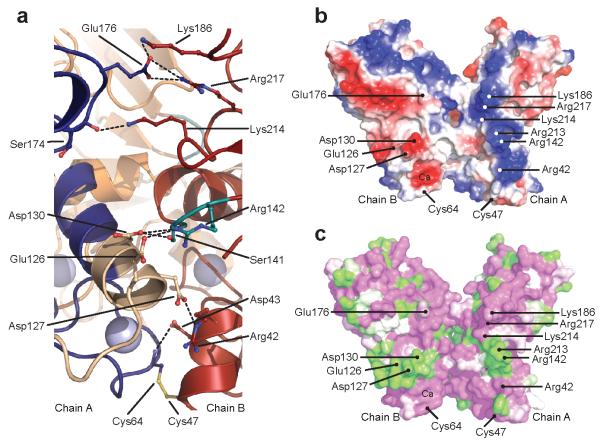

While interactions within the base region stabilize the trimer, procollagen chain selectivity is assured by the petals. In particular, the highly variable, discontinuous 15 residue chain recognition sequence7 (CRS) straddles helix 4, with its longer, 12 residue stretch (residues 120-131) at the N-terminal end and its shorter, 3 residue stretch (residues 140-142) at the C-terminal end (Figs. 1b,e). While the existence of the CRS has been known for some time, the structural basis of chain recognition has until now remained a mystery. The three-dimensional structure presented here reveals immediately how the CRS controls inter-chain interactions, and in particular the need for a discontinuous sequence. As shown in Figs. 1d and 2a, residues in the long stretch of the CRS on one chain interact with residues in the short stretch of the CRS on a neighboring chain, thus revealing an exquisite mechanism of specific chain recognition. Indeed, the structure defines the key specificity-conferring elements within the CRS and also reveals other regions of the molecule involved in chain recognition (Supplementary Fig. 2). Specifically, inter-chain interactions include salt bridges between Arg142 (CRS short) and Glu126 and Asp130 (both CRS long), between Asp127 (CRS long) and the conserved Arg42 in the base region, as well as between conserved residues (Glu176 with Lys186 and Arg217). Viewed from the side, the interacting surfaces on chains A and B are seen to consist of patches of positive and negative charge, respectively, interacting with patches of opposite charge on chain C (Fig. 2b). These patches consist of both conserved and variable residues, the latter coming mostly from the CRS (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

Details of the interaction interface. (a) Close-up of the A/B chain interface (1.7Å structure) showing the inter-chain interactions (same color code as Figs. 1d,e). (b) Cut-away view (as in Fig. 1d with one chain removed) showing, in surface representation, charge complementarity at the inter-subunit interface (negatively charged, red; positively charged, blue). Residues involved in inter-chain interactions are indicated. (c) Same view as (b) but color-coded according the extent of sequence conservation seen in Fig. 1b (green, no homology; white, weak homology; magenta, strong homology/identity). Drawn using PyMOL, Version 1.4.1, Schrödinger, LLC.

DISCUSSION

Homotrimers, heterotrimers and other proteins

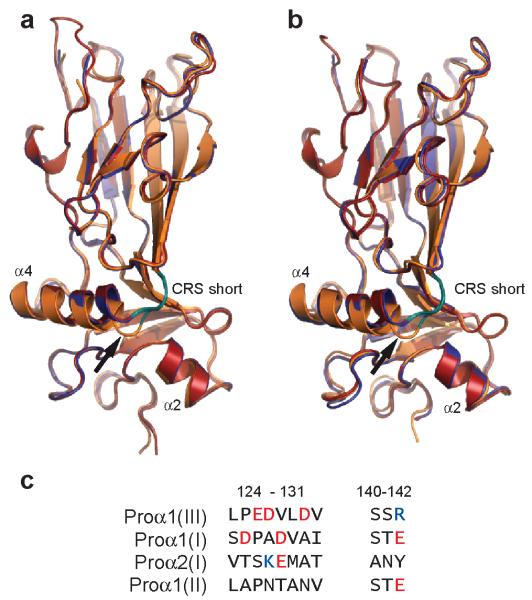

Close examination of both the 1.7Å and 2.2Å structures reveals subtle differences in the conformations of the three polypeptide chains, with one chain differing from the other two, particularly at the C-terminal end of helix 4 (Figs. 3a,b). Specifically, while in general all three chains superimpose well in a structural alignment, chain C bulges out at Leu139, immediately before the short stretch of the CRS. This observation was totally unexpected. Since all three chains have the same amino acid sequence, it might have been assumed that their structures would be identical. Instead, these observations raise the intriguing possibility that there is an intrinsic asymmetry in the structure that arises when all three chains pack together. Such an asymmetry might account for why, in some types of collagen, molecules have evolved to be heterotrimers (consisting of more than one type of polypeptide chain, as in procollagen I for example) rather than homotrimers. The presence of a third chain distinct from the other two might permit further optimization of packing interactions in the C-propeptide trimer.

Figure 3.

Structural alignment of the three chains of the proα1(III) C-propeptide trimer in the (a) 2.2Å and (b) 1.7Å structures (space groups P212121). While overall alignment is good, the conformation of chain C (orange) differs from those of chains A (blue) and B (red) particularly on the C-terminal side of helix 4, at Leu139 (arrow), immediately before the short stretch of the chain recognition sequence (CRS; deep teal color). Drawn using PyMOL, Version 1.4.1, Schrödinger, LLC. (c) Comparison of residues involved in inter-chain interactions in the chain recognition sequences of procollagens I, II and III. Negatively charged residues are shown in red, and positively charged residues in blue.

The question also arises of how specificity is determined in other procollagen types, both heterotrimers and homotrimers. With regard to procollagen I, we note differences in amino acid sequence in the interaction zone, compared to procollagen III, that are consistent with interactions between the proα1(I) and proα2(I) chains (Fig. 3c). Specifically, the positively charged Arg142 is unique to procollagen III, as are the negatively charged residues Glu126, Asp127 and Asp130. In contrast, Asp127 is replaced by Lys in the proα2(I) chain, while Arg142 is replaced by Glu in the proα1(I) chain. Such changes may contribute to the preferred association of the proα2(I) C-propeptide with the proα1(I) C-propeptide in procollagen I. Further insights must await the structure determination of other procollagen C-propeptide trimers.

Though the structure of the C-propeptide trimer (excluding the stalk region) shows no obvious similarities with the globular regions of other extracellular trimeric proteins (Supplementary Fig. 3a-e), detailed comparison using the DALI server23 revealed some structural similarities with proteins containing the fibrinogen C-terminal domain (FBG), including angiopoietin-2, fibrinogens and ficolins. The most striking example is angiopoietin-2 (Supplementary Fig. 3f) where, despite a low sequence identity (< 15 %; Supplementary Fig. 3g), most secondary structure elements are aligned in three dimensions, with the loop regions being much more variable. Structural similarity is particularly strong in the base region, including a conserved intra-chain disulfide bond. Whether this is a result of convergent or divergent evolution is unknown. It has previously been shown however that procollagen C-propeptides trimers are involved in tumor vascularization19,20, through effects on endothelial cell migration and induction of VEGF. This structural similarity with FBG domain-containing proteins such as angiopoietin-2 may therefore give insights into the mechanisms of such additional functions of the C-propeptides.

Structural basis of related genetic disorders

Fibrillar procollagen C-propeptides are associated with several genetic disorders of connective tissues, including different forms of osteogenesis imperfecta (OI; procollagen I), cartilage/bone dysplasias (procollagen II), and two types of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, type I (affecting mainly skin; procollagen V) and type IV (leading to vascular deficiency; procollagen III). While hundreds of mutations throughout the length of the collagen molecule have been described1, mutations in the C-propeptides are particularly important in view of their role in directing the assembly of the procollagen molecule. In general, such mutations can have two consequences: either the mutation prevents trimerization completely, leading (in heterozygotes) to haploinsufficiency of the affected collagen type, or the mutation leads to abnormal procollagen assembly, involving both wild type and mutant chains1,24. In total, 46 missense mutations (involving 38 distinct sites) have been identified in the C-propeptides of the proα1(I), proα2(I), proα1(II), proα1(III) and proα1(V) chains (Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 4). In most cases, the residue that is mutated in the other procollagen types is conserved in the proα1(III) C-propeptide. This, as well as the strong similarity between the structure presented here and those predicted for the other procollagen types (Supplementary Fig. 4), permits mapping of these mutations on to the procollagen III C-propeptide structure (Fig. 4; Supplementary Video 1). Note that mutation sites for the proα2(I) chain are not shown in Fig. 4 as all lead to mild/moderate forms of OI, probably due to substitution by the proα1(I) chain to form the trimer.

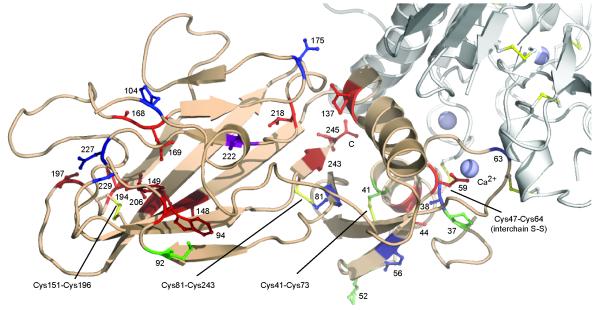

Figure 4.

Positions of known missense mutations in the C-propeptides of fibrillar procollagens I, II, III and V mapped on to the structure of the proα1(III) C-propeptide. One chain of the proα1(III) C-propeptide trimer is shown in wheat color, with the other chains shown (in part) in light grey. Only mutation sites where the corresponding residues in the proα1(III) chains are identical are shown. Sites associated with lethal/severe forms of OI or PLSD-T/SPD are in red and dark red, respectively, with mild/moderate forms in blue (OI) and dark blue (PLSD-T/SPD), respectively. Asp222 is in purple as two different mutations in proα1(I) lead either to mild or lethal OI. Mutation sites in proα1(III) and proα1(V) are in green and dark green, respectively. Sites numbered from the start of the C-propeptide domain. Drawn using PyMOL, Version 1.4.1, Schrödinger, LLC. Movie version available in Supplementary Video 1. See also Supplementary Fig. 4 for the locations of the mutations in the different amino acid sequences.

This mapping allows us to make the following general observations. First, mutations leading to mild to moderate phenotypes (shown in blue or dark blue in Fig. 4) generally involve surface located residues in regions not involved in inter-chain interactions, and therefore are unlikely to interfere with folding or trimerization. The only exception is the Cys81Trp mutation in the proα1(I) chain, which disrupts disulfide bond formation with Cys243, yet leads to a relatively mild OI phenotype (albeit associated with fractures of four ribs and a clavicle at birth) and gives rise to delayed trimerization and secretion of procollagen25. Second, mutations leading to the most severe phenotypes (shown in red or dark red in Fig. 4) are found to be clustered in three regions of the molecule. These include the environment of the C-terminus of each chain, at the interface between the petal and the base. Mutations in this region are involved in intra-chain disulfide bonding (Cys81-Cys243), inter-chain interactions (Leu245, Arg137) or stabilization of the hydrophobic core (Leu218). Among these, mutations near the C-terminus disrupt trimerization26 and lead to severe/lethal forms of OI (e.g. the Leu245Pro mutation in the proα1(I) chain resulting in at least 200 bone fractures before four years of age27) or skeletal dysplasia (e.g. the Cys243Gly mutation in the proα1(II) chain resulting in short stature and limbs and leading to death at 22 days from respiratory insufficiency28). In addition, many of the most severe phenotypes are associated with mutations in the region of the Cys151-Cys196 disulfide bond, located near the tip of the petals, disrupting either intra-chain disulfide bonding or internal hydrophobic interactions. These include, for example, the Trp94Cys mutation in the proα1(I) chain, leading to multiple fractures and perinatal death29, or the Tyr149Cys mutation in the proα1(II) chain, also resulting in perinatal death, this time due to severe skeletal dysplasia30. Finally, other severe/lethal mutations disrupt the base region, containing the remaining intra-chain disulfide bond (Cys41-Cys73) and the Ca2+ binding loop. For example, the Asp59His mutation in the proα1(I) chain removes a Ca2+ binding ligand and disrupts inter-chain disulfide bonding, resulting in perinatal death from lethal OI31. Missense mutations have also been reported in procollagens III (shown in green in Fig. 4) and V (dark green), again mostly in the base region (Supplementary Table 1). For example, the Cys41Ser mutation in the proα1(V) chain disrupts disulfide-binding and leads to Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type I, characterized by skin and joint hyperextensibility, as well as poor wound healing32. Such mutations underline the essential role of the highly conserved base region in the trimerization of fibrillar procollagens.

In summary, here we present the long awaited structure of the procollagen III C-propeptide trimer, thereby providing a paradigm for this family of protein domains with key implications for human disease. This provides a structural basis for interpreting the effects of new C-propeptide mutations in genetic disorders, and also for the development of new anti-fibrotic therapies aimed at disrupting either procollagen trimerization or C-propeptide interactions with other proteins involved in the regulation of collagen fibril formation.

ONLINE METHODS

Full details of protein expression, purification, crystallization and data collection are presented in an accompanying paper36. Briefly, the construct CPIIIHis11, consisting of the C-propeptide trimer from human procollagen III (each chain mutated at the single N-linked glycosylation site) together with an N-terminal His6-tag, as well as its SeMet derivative, were expressed by transient transfection of HEK 293 T cells37. Following crystallization, X-ray diffraction data were collected at 100 K, at 0.9795 Å (form I, SeMet, peak data collected only) or 0.9763 Å (forms II and III), on beamlines I03 and I04 at Diamond Light Source, Didcot, UK. Data were processed using XDS38, as well as Xia2, MOSFLM and SCALA from the CCP4 program suite (http://www.ccp4.ac.uk). Three different crystal forms were obtained (Table 1). First, the structure of the SeMet derivative (form I, resolution 2.2Å) was solved by the single anomalous dispersion method using the program AutoSol39 from Phenix (http://www.phenix-online.org). Next, the structure corresponding to form II (native protein, 1.7Å resolution) was solved by molecular replacement using MOLREP40 with a monomer from form I as search model. Finally, a monomer from the 1.7Å structure served as a guide for structure determination by molecular replacement of form III (native protein, resolution 3.5Å). All structures were refined over several rounds using REFMAC541 (including TLS for form III), alternating with manual adjustments in Coot42. Geometry was checked using MolProbity43. Ramachandran statistics were as follows: form I (favored region 96.5 %, allowed 3.5 %, disallowed 0 %), form II (favored region 97.1 %, allowed 2.9 %, disallowed 0 %), form III (favored region 98.2 %, allowed 1.8 %, disallowed 0 %). Structure similarity searches were carried out using DALI23.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Frédéric Delolme, Denise Eichenberger, Kamel El Omari, Patrice Gouet, Richard Haser, Robert Liddington, Goetz Parsiegla, Xavier Robert, Gudrun Stranzl, Sandrine Vadon-Le Goff, Michel van der Rest and Tom Walter for their help and suggestions at different stages of the project. We also thank Annie Chaboud and Isabelle Grosjean of the Protein Production and Analysis facility (Unité Mixte de Service Biosciences Gerland-Lyon Sud 3444) as well as staff of Diamond Light Source for technical support. The work was funded by the Fondation de France (D.J.S.H.), the Agence National de la Recherche (project SCAR FREE to D.J.S.H.; project TOLLREG to C.M.), the European Commission (project P-CUBE to E.Y.J.), the Medical Research Council UK and Cancer Research UK (E.Y.J), the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and the Université Lyon 1 (to D.J.S.H. and C.M.)

Footnotes

Accession codes: Atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank (www.pdb.org) under accession codes 4AEJ (crystal form I), 4AE2 (crystal form II) and 4AK3 (crystal form III).

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

This work forms part of a US patent application by J.M.B., N.M., C.M., N.A. and D.J.S.H.

References

- 1.Bateman JF, Boot-Handford RP, Lamandé SR. Genetic diseases of connective tissues: cellular and extracellular effects of ECM mutations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:173–183. doi: 10.1038/nrg2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ricard-Blum S. The collagen family. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011;3:a004978. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mclaughlin SH, Bulleid NJ. Molecular recognition in procollagen chain assembly. Matrix Biol. 1998;16:369–377. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bottomley MJ, Batten MR, Lumb RA, Bulleid NJ. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. PDI mediates the ER retention of unassembled procollagen C-propeptides. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:1114–1118. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boudko SP, Engel J, Bachinger HP. The crucial role of trimerization domains in collagen folding. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012;44:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Exposito JY, Valcourt U, Cluzel C, Lethias C. The fibrillar collagen family. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010;11:407–426. doi: 10.3390/ijms11020407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lees JF, Tasab M, Bulleid NJ. Identification of the molecular recognition sequence which determines the type-specific assembly of procollagen. EMBO J. 1997;16:908–916. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kadler KE, Holmes DF, Trotter JA, Chapman JA. Collagen fibril formation. Biochem. J. 1996;316:1–11. doi: 10.1042/bj3160001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canty EG, Kadler KE. Procollagen trafficking, processing and fibrillogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:1341–1353. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muir A, Greenspan DS. Metalloproteinases in Drosophila to humans that are central players in developmental processes. J. Biol Chem. 2011;286:41905–41911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.299768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vadon-Le Goff S, et al. Procollagen C-proteinase enhancer stimulates procollagen processing by binding to the C-propeptide only. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:38932–38938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.274944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wynn TA. Common and unique mechanisms regulate fibrosis in various fibroproliferative diseases. J Clin. Invest. 2007;117:524–529. doi: 10.1172/JCI31487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu CH, Walton CM, Wu GY. Propeptide-mediated regulation of procollagen synthesis in IMR-90 human lung fibroblast cell cultures. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:2983–2987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizuno M, Fujisawa R, Kuboki E. The effect of carboxyl-terminal propeptide of type I collagen (C-propeptide) on collagen synthesis of preosteoblasts and osteoblasts. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2000;67:391–399. doi: 10.1007/s002230001150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies D, et al. Molecular characterisation of integrin-procollagen C-propeptide interactions. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;246:274–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindahl K, et al. COL1 C-propeptide cleavage site mutations cause high bone mass osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum. Mutat. 2011;32:598–609. doi: 10.1002/humu.21475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Rest M, Rosenberg LC, Olsen BR, Poole AR. Chondrocalcin is identical with the C-propeptide of type II procollagen. Biochem. J. 1986;237:923–925. doi: 10.1042/bj2370923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee ER, Smith CE, Poole AR. Ultrastructural localization of the C-propeptide released from type II procollagen in fetal bovine growth plate cartilage. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1996;44:433–443. doi: 10.1177/44.5.8627001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmieri D, et al. Procollagen I COOH-terminal fragment induces VEGF-A and CXCR4 expression in breast carcinoma cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2008;314:2289–2298. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vincourt JB, et al. C-propeptides of procollagens I alpha 1 and II that differentially accumulate in enchondromas versus chondrosarcomas regulate tumor cell survival and migration. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4739–4748. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McAlinden A, et al. α-helical coiled-coil oligomerization domains are almost ubiquitous in the collagen superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:42200–42207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ricard-Blum S, et al. Interaction properties of the procollagen C-proteinase enhancer protein shed light on the mechanism of stimulation of BMP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:33864–33869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holm L, Rosenstrom P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W545–W549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byers PH. Folding defects in fibrillar collagens. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond [Biol.] 2001;356:151–157. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pace JM, Kuslich CD, Willing MC, Byers PH. Disruption of one intra-chain disulphide bond in the carboxyl-terminal propeptide of the proα1(I) chain of type I procollagen permits slow assembly and secretion of overmodified, but stable procollagen trimers and results in mild osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Med. Genet. 2001;38:443–449. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.7.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim AL, Doyle SA, Balian G, Smith BD. Role of the pro-alpha2(I) COOH-terminal region in assembly of type I collagen: Truncation of the last 10 amino acid residues of pro-alpha2(I) chain prevents assembly of type I collagen heterotrimer. J. Cell Biochem. 1998;71:216–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliver JE, Thompson EM, Pope FM, Nicholls AC. Mutation in the carboxy-terminal propeptide of the Pro alpha 1(1) chain of type I collagen in a child with severe osteogenesis imperfecta (OI type III): Possible implications for protein folding. Hum Mutat. 1996;7:318–326. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1996)7:4<318::AID-HUMU5>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zankl A, et al. Dominant negative mutations in the C-propeptide of COL2A1 cause platyspondylic lethal skeletal dysplasia, torrance type, and define a novel subfamily within the type 2 collagenopathies. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2005;133A:61–67. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamandé SR, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum-mediated quality control of type I collagen production by cells from osteogenesis imperfecta patients with mutations in the pro alpha 1(I) chain carboxyl-terminal propeptide which impair subunit assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:8642–8649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishimura G, et al. Identification of COL2A1 mutations in platyspondylic skeletal dysplasia, Torrance type. J. Med. Genet. 2004;41:75–79. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.013722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chessler SD, Wallis GA, Byers PH. Mutations in the Carboxyl-Terminal Propeptide of the pro-alpha-1(I) Chain of Type-I Collagen Result in Defective Chain Association and Produce Lethal Osteogenesis Imperfecta. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:18218–18225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Paepe A, Nuytinck L, Hausser I, Anton-Lamprecht I, Naeyaert JM. Mutations in the COL5A1 gene are causal in the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes I and II. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;60:547–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Myllyharju J, Kivirikko KI. Collagens, modifying enzymes and their mutations in humans, flies and worms. Trends Genet. 2004;20:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI, Metoz F. ESPript: analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:305–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bourhis JM, et al. Production and crystallization of the C-propeptide trimer from human procollagen III. Acta Cryst. F. 2012 doi: 10.1107/S1744309112035294. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aricescu AR, Lu W, Jones EY. A time- and cost-efficient system for high-level protein production in mammalian cells. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:1243–1250. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906029799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terwilliger TC, et al. Decision-making in structure solution using Bayesian estimates of map quality: the PHENIX AutoSol wizard. Acta Cryst D. 2009;65:582–601. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909012098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Cryst. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vagin AA, et al. REFMAC5 dictionary: organisation of prior chemical knowledge and guidelines for its use. Acta Cryst D. 2004;60:2284–2295. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Cryst D. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.