Abstract

Although psychiatric disorders such as autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder affect a number of brain regions and produce a complex array of clinical symptoms, basic phenotypes likely exist at the level of single neurons and simple networks. Being highly heritable, it is hypothesized that these disorders are amenable to cell-based studies in vitro. Using induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons and/or induced neurons from fibroblasts, limitless numbers of live human neurons can now be generated from patients with a genetic background permissive to the disease state. We predict that cell-based studies will ultimately contribute to our understanding of the initiation, progression and treatment of these psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder, neurons, schizophrenia, stem cells

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), schizophrenia (SCZD) and bipolar disorder (BD) combine to affect nearly 1 in 30 adults throughout the global population.1 While these psychiatric disorders are characterized by markedly different clinical phenotypes, recent genetic studies have suggested that they may share common underlying molecular causes. ASD, SCZD and BD are believed to be developmental in origin, resulting from events that occur in fetal development or early childhood. The molecular mechanism of these disorders is difficult to study in patients or animal models because of the complex genetic etiologies and varying environmental effects contributing to disease.

Cell-based models produce live human neurons with genetic backgrounds permissive to the disease state. Temporal analysis of disease initiation and progression can be studied in the cell type relevant to disease. Human cell-based models can be ideal experimental paradigms with which to investigate disease mechanisms; for example, studies of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis have revealed a non-cell autonomous contribution of glial cells to this neuronal disease.2, 3 In order to be studied using an in vitro model, a given disease must (1) be highly genetic, ensuring that cultured cells are afflicted by disease in the absence of any potentially unresolved environmental factors and (2) affect a cell type that can survive and, ideally, be robustly expanded when cultured in vitro. With respect to the first criterion, twin studies have calculated the heritability of ASD, SCZD and BD to be between 70 and 90%.4, 5, 6 Our hypothesis is that this genetic predisposition to psychiatric illness is sufficient that cultured neurons will consistently undergo disease initiation and progression. Regarding the second criterion, while mature neurons are postmitotic and cannot be expanded in culture, conditions for the survival of human neurons are well described,7 and robust quantities of neurons for study can be generated through the growth and subsequent differentiation of proliferative neural progenitor cells.

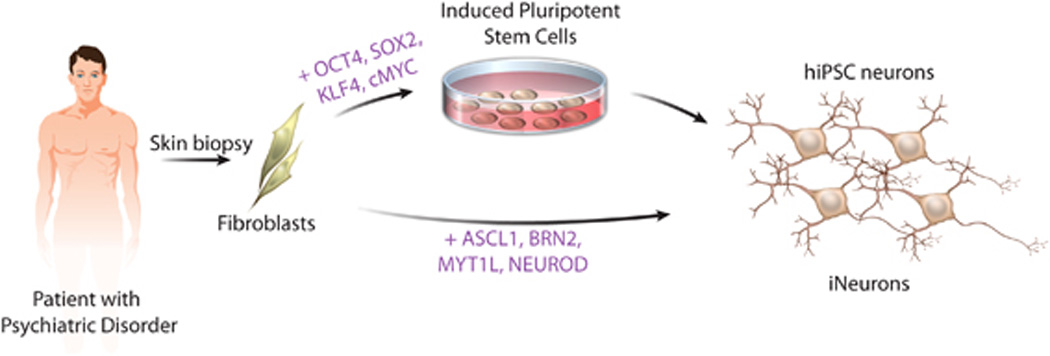

The ability to compare cellular and network properties of live human neurons in vitro represents an important new approach with which to study psychiatric disease because live human neurons from patients or controls are exceedingly rare. Recently, three new sources of live human neurons have been reported: primary olfactory neural precursors, neurons differentiated from human-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSC neurons) and induced neurons (iNeurons) generated from primary patient fibroblasts. Although olfactory neural precursors are capable of self-renewal and differentiation to mature neurons,8, 9 olfactory neural precursors cannot yield cells from the neural lineages specifically implicated in psychiatric disorders, such as GABAergic or dopaminergic neurons. Because we believe it is critical that the relevant cell type affected in the disease state be studied, we will therefore focus on in vitro models of psychiatric disease utilizing hiPSC neurons and iNeurons (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

While generally considered to be whole-brain disorders, we suggest that ASD, SCZD and BD can be broken down to component aberrations at the cellular and/or network levels. For example, at the cellular level, the subtle synaptic defects that are believed to contribute to illness can be studied with cell-based models. Furthermore, while the cyclical behavioral swings of BD cannot be reproduced, patterns of spontaneous and stimulated neuronal network activity can be measured in vitro. Using cell-based models, one can study ASD, SCZD and BD by observing the abnormal development of neurons and their circuitry in vitro.

In this review, we will discuss (1) post-mortem and animal studies demonstrating that cellular phenotypes exist at the neuronal level in these disorders (Tables 1 and 2), (2) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electrophysiological evidence from humans and rodents suggesting that network defects contribute to these disorders (Tables 1 and 2) and (3) the recent findings of novel in vitro models of psychiatric disorders (Table 3).

Table 1.

Summary of published cellular and network phenotypes in human SCZD patients

| Disease | Study | Brain region/cell type | Observation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD | MRI, post-mortem | Cerebrum | Increased cerebral white matter volume in children, excess number of neurons in prefrontal cortex in children | Carper et al.,10Courchesne,11Hazlet et al.,12Courchesne et al.13 |

| ASD | MRI | Cerebrum, corpus callosum | Reduced frontal and parietal lobe gray matter volume in older children and adults, increased ventricular volume, reduced corpus callosum volume | Courchesne et al.,14 Schmitz et al.,16 Brun et al.,17Wright et al.,27Frazier and Harden18 |

| ASD | Post-mortem | Hippocampus, cortex | Reduced dendritic arborization in hippocampus, greater cortical pyramidal spine density correlated with decreased cognitive function, loss of vertical and horizontal organization of cortical layers | Raymond et al.,19Hutsler and Zhang,48 Wegiel et al.72 |

| ASD | fMRI | Cortex | Increased connectivity between proximal:posterior cingulate/parahippocampal gyrus, decreased connectivity between distal:frontal lobe-parietal lobe, insular cortices-somatosensory cortices of amygdala, frontal cortex-posterior cingulated, decreased interhemispheric synchronization | Monk et al.,80Kennedy and Courchesne,81Ebisch et al.,82Dinstein et al.,83Kennedy and Courchesne 84 |

| ASD (RTT) | Post-mortem | Cortex, hippocampus | Reduced cell size and dendritic arborization in cortex, reduced number of dendritic spines in hippocampus | Bauman et al.,22Chapleau et al.49 |

| ASD (FX) | In vitro | Post-mortem neurosphere culture, fetal cortical NPC culture | Neurons with fewer and shorter neurites, smaller cell body volume and decreased glial differentiation; normal neurogenesis by fetal NPCs | Castren et al.,23Bhattacharyya et al.24 |

| ASD (FX) | Post-mortem | Cortical pyramidal cells | Longer, more slender dendritic spine shape | Irwin et al.50 |

| SCZD | MRI | Gray matter frontal cortex, temporal lobe, hippocampus, amygdala, basal ganglia | Decreased volume (whole brain) in early phase SCZD | Vita et al.,25 Steenet al.,26 Thompsonet al.,28 Ellison-Wright et al.29 |

| SCZD | Post-mortem | Cortex, hippocampus | Reduced dendritic arborization, reduced soma size, increased neuronal density, decreased synaptic density | Rajkowska et al.,30Kolomeets et al.,31Black et al.,32Selemon et al.,33Garey et al.,51Glantz and Lewis52, Kolomeets et al.53 |

| SCZD | fMRI | Frontal/temporal lobe | Brain activity abnormality in frontal and temporal lobes | Yurgelun-Todd et al.,85 Yurgelun-Todd et al.86 |

| SCZD | fMRI | Cortex | Cortical hyper-activity and hyper-connectivity in prefrontal cortex at rest, reduced activation of medial prefrontal during working memory tasks in early phase SCZD, increased functional connectivity between the ventral prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex greater, decreased functional connectivity between the dorsal prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex greater | Whitfield-Gabrieliet al.,87 Tan et al.88 |

| SCZD | Anatomical networks analysis | Cortex | Cortical organization altered, loss of network hubs in frontal cortex, emergence of hubs outside cortex | Bassett et al.89 |

| SCZD | Post-mortem, PET | Substania nigra, striatum, cortex | Increased DA receptor sensitivity, increased DA receptor levels in substania nigra, correlation of DA receptor expression level in temporal cortex and striatum to positive symptoms of SCZD | Owen et al.,91Kessler et al.,90 |

| SCZD | Pharmacology | Not determined | NMDA antagonist ketamine induces SCZD-like symptoms, MGLUR2/3 agonists ameliorate them | Krystal et al.,92Patil et al.93 |

| SCZD | Post-mortem | Hippocampus, cortex | Reduced GLU receptor expression | Meador-Woodruff and Healy94 |

| BD | MRI | Limbic system (amygdala/hippocampus) | Reduced brain volume: limbic system (amygdala, hippocampus, frontal cortex) in adolescents | Karchemskiy et al.,34 Frazier, 35 |

| BD | Post-mortem | Entorhinal cortex | Decreased cell number and density of GABA neurons | Rajkowska et al.,37Pantazopoulos et al.38 |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; BD, bipolar disorder; DA, dopamine; GLU, glutamate; FX, fragile X syndrome; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NPC, neural progenitor cell; RTT, Rett syndrome; SCZD, schizophrenia disorder.

Table 2.

Summary of published cellular and network phenotypes in rodent models of SCZD

| Disease | Gene | Brain region/cell type | Observation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD | Cntnap2 | Cortex, GABA | Impaired migration of cortical projection neurons, reduced GABAergic neurons, decreased neural synchrony | Penagarikano et al.100 |

| ASD | Shank3 | Hippocampal neural cultures | Reduced dendritic spine induction/maturation in vitro | Durand et al.57 |

| ASD (RTT) | Mecp2 | Hippocampus, cortex, cerebellum, retinogeniculate synapse, NPCs | Reduction in neuronal size, dendritic arborization abnormalities, thinner cortical layers, reduced spine density, defects in synaptic maturation and synaptic transmission, impaired experience dependent remodeling, and altered gene expression | Chen et al.,39 Kishi and Macklis,40 Smrt et al.,41Asaka et al.,54 Moretti et al.,55 Nelson et al.,56 Noutelet al.,98 Dani et al.99 |

| ASD (FX) | Fmr1 | Cortex, neurosphere culture | Thin and elongated dendritic spines on pyramidal neurons, increased spine density along apical dendrites, in vitrodifferentiated neurons have fewer and shorter neurites and a smaller cell body volume | Comery et al.,58 Castren et al.23 |

| SCZD | Disc1 | Cortex, hippocampus | Reduction in fetal cortical neural progenitor proliferation and premature neural differentiation, reduced cortical migration, diminished response to cAMP-sensitive repulsive cues, reduced neurite outgrowth, synaptic transmission and altered distribution of hippocampal neurons | Mao et al.,67 Kamiya et al.,74 Kvajo et al.,42 Li et al.43 |

| SCZD | Disc1 knockdown | Hippocampal adult-born neurons | Adult newborn neurons show accelerated dendritic development and synapse formation, defects in axonal targeting, enhanced excitability | Faulker et al.,70 Duan et al.69 |

| SCZD | Nrg1 | Cortex, peripheral nerves | Aberrant tangential migration of neurons derived from the ventral telencephalon, impaired synaptic maturation and function, hypomyelination | Lopez-Bendito et al.,44Barros et al.,60 Chen et al.62 |

| SCZD | ErbB4 | Hippocampus, cortex | Aberrant neurite outgrowth and synapse maturation, reduced long-term potentiation, suppressed Src-dependent enhancement of NMDAR responses during theta-burst stimulation, reduced excitatory input onto GABAergic neurons, PPI deficits | Krivosheya et al.,45 Pitcheret al.,61 Pitcher et al.,101Barros et al.,60 Li et al.,95Chen et al.62 |

| SCZD | 22q11.2 | Cortex, hippocampus | Fewer cortical neurons with smaller spines, altered short- and long- term synaptic plasticity and calcium kinetics, impaired hippocampal-prefrontal synchrony | Fenelon et al.63 Earls et al.,64 Sigurdsson et al.65 |

| SCZD | Reln | Cortex, hippocampus | Decreased dendritic spine maturation, density and plasticity | Pappas et al.66 |

| SCZD | Dtnbp1 | GABA | Decreased PPI, reduced evoked gamma activity | Carlson et al.104 |

| BD | Clock | Striatum (nucleus accumbens) | Increased length and complexity of dendrites, normal synaptic density, dysfunctional gamma activity across limbic circuits, improved by lithium treatment | Dzirasa et al.46 |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; BD, bipolar disorder; FX, fragile X syndrome; PPI, prepulse inhibition; RTT, Rett syndrome; SCZD, schizophrenia disorder.

Table 3.

Summary of published reports of hiPSC-based models of ASD, SCZD and BD

| Disease | Reference | Genetic mutation | Neuronal phenotype | hiPSC method | Source of cells | Patient sex; age at biopsy (years); available phenotypic information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RTT | Cheung et al.122 | MeCP2(Δ3–4, T158M, R306C) | Decreased soma size | Retrovirus: four factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4,c-MYC) | Fibroblast: patient biopsy (1) and Coriell GM11270 (2), GM17880 (3) |

|

| RTT | Marchettoet al.123 | MeCP2(1155del3, Q244X, T158M, R306C) | Reduced soma size and spine density, fewer synapses, altered calcium signaling, electrophysiological abnormalities | Retrovirus: four factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4,c-MYC) | Fibroblast: Coriell GM11272 (1), GM16548 (2), GM17880 (3), GM11270 (4) |

|

| RTT | Ananiev et al.124 | MeCP2(T158M, V247X, R306C) | Decrease in nuclear and neuron size | Lentivirus: four factors (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2, LIN28), Retrovirus: 4 factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) | Fibroblast: Coriell GM17880 (1), GM07982 (2), GM11270 (3) |

|

| Timothy syndrome | Paşca et al.129 | CACNA1C | Defects in calcium signaling, decreased expression of cortical genes, increased production of norepinephrine and dopamine | Retrovirus: four factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4,c-MYC) | Fibroblast: patient biopsy |

|

| FXS | Urbach et al.127 | FMR1 | No neurons generated | Retrovirus: four factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4,c-MYC) | Fibroblast: Coriell GM05848 (1), GM07072 (2), GM09497 (3) |

|

| FXS | Sheridanet al.128 | FMR1 | Fewer and shorter neural processes, increased glial cells with more compact morphology | Retrovirus: four factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4,c-MYC) | Fibroblast: Coriell GM05848 (1), GM05131 (2), GM05185 (3) |

|

| SCZD | Chiang et al.131 | DISC1 | No neurons generated | Episome: four factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4,c-MYC) | Fibroblast: patient biopsy |

|

| SCZD | Brennandet al.132 | Sporadic | Reduced neuronal connectivity, fewer neurites, decreased PSD95 and glutamate receptor expression levels | Tetracycline-inducible lentivirus: five factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4,c-MYC, LIN28) | Fibroblast: Coriell GM02038 (1), GM01792 (2), GM01835 (3), GM02497 (4) |

|

| SCZD | Paulsen et al.133 | Sporadic | Elevated extra-mitochondrial oxygen consumption, increased levels of reactive oxygen species | Retrovirus: four factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4,c-MYC) | Fibroblast: patient biopsy | Female; 48; clozapine-resistant |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; BD, bipolar disorder; EEG, electroencephalogram test; FX, fragile X syndrome; hiPSC, human-derived induced pluripotent stem cell; NA, not applicable; PBL, peripheral blood lymphocyte; RTT, Rett syndrome; SCZD, schizophrenia disorder.

EVIDENCE FOR CELLULAR PHENOTYPES IN PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

Aberrant neuronal connectivity, as assessed by dendritic arborization and synaptic density, is a characteristic that appears to be shared between ASD, SCZD and BD. Perturbed neuronal migration has also been linked to psychiatric disorders, although whether this contributes to, or functions separately from, abnormal neuronal connectivity remains to be demonstrated.

Altered dendritic arborization

At onset, ASD is often characterized by excessive brain volume; MRI studies observed increased cerebral white matter volume in 2- to 4-year-old autistic children,10, 11, 12 which has been correlated with an excess number of neurons in the prefrontal cortex.13 Over the lifetime of the ASD patient, however, the brain overgrowth phenotype is typically reversed; studies of adults with ASD have observed cortical thinning14, 15 and reduced frontal lobe10, 16, 17 and corpus callosum18 volumes. While we found few anatomical post-mortem studies of ASD, there are reports of reduced dendritic arborization in hippocampal neurons in two cases of ASD.19 In Rett syndrome (RTT), a severe and rare ASD caused by the mutation of the MECP2 gene,20, 21 post-mortem studies report reduced neuronal cell size and dendritic arborization throughout the cortex.22 Reports of fragile X syndrome (FX), another monogenetic form of ASD, have been less conclusive: while one study reported differences in dendritic arborization following in vitro differentiation of neurospheres derived from post-mortem human FXS brain tissue,23 a second group failed to observe significant differences in a similar study.24

Decreased whole-brain volume is consistently observed in SCZD,25, 26, 27particularly in the gray matter of the frontal cortex, temporal lobe (particularly the hippocampus and amygdala) and the basal ganglia,27, 28, 29 and longitudinal studies report that progressive brain volume declines for at least 20 years after the onset of symptoms. Post-mortem studies of brains from patients with SCZD have not found evidence of neuronal loss; instead, they observe smaller neuronal somas30, 31 reduced dendritic arborizations31, 32 and increased neuronal density without changes in absolute cell number in the cortex and hippocampus.30, 33

Decreased brain volumes in the limbic system, particularly the amygdala and hippocampus, and in the frontal cortex are associated with BD.34, 35 It remains unclear, however, whether brain volume changes are a preexisting factor contributing to the development of BD or a consequence of prolonged illness; one recent study suggests that brain volume changes are more tightly correlated to active psychosis than BD.36 Despite observations of diminished brain volumes and reduced neuronal density in BD patients,37, 38 we found no report of altered dendritic arborization or synaptic density in post-mortem studies of BD patient brains.

Mouse models of a number of psychiatric disorders have been developed. For the most part, these mice have reduced expression of rare, highly penetrant genes implicated in ASD, SCZD or BD. RTT (Mecp2 null) mouse brains show a reduction in neuronal size;39 and abnormalities in dendritic arborization.39, 40, 41Conversely, dendritic arborization defects have not been reported in FX (Fmr1null) mice. Many SCZD mouse models, including Disc1 and heterozygous-nullNrg1 and Erbb4 mice, have reduced neurite outgrowth and reduced dendritic complexity.42, 43, 44, 45 Although few genetic mouse models of BD have been reported, neurons from mice with a point mutation in the circadian Clock gene display complex changes in dendritic morphology,46 which can be ameliorated with lithium, a drug routinely used in the treatment of BD.46

Altered synaptic density

A number of genes implicated in ASD, SCZD and BD have been associated with synaptic maturation and function.47 Post-mortem synaptic spine density has not been adequately explored in human patients with ASD. One report found that relative to controls, spine densities on cortical pyramidal cells were greater in ASD subjects, and highest spine densities were most commonly found in ASD subjects with lower levels of cognitive functioning.48 Conversely, the number of spines in dendrites of neurons from post-mortem RTT brains is reduced.49 In FX patients, post-mortem studies have identified abnormalities in dendritic spine shape in cortical pyramidal cells, which tend to be both longer and more slender than controls.50 Post-mortem studies of SCZD patient brains found reduced dendritic spine density in the cortex51, 52 and hippocampus.31, 53 What post-mortem analysis of ASD and SCZD has failed to resolve is whether disease progression reflects developmental aberrations during neuronal differentiation or activity-dependent atrophy of neuronal dendrites or synapses in mature neurons.33

Animal studies recapitulate these synaptic defects. Using mouse models of RTT, decreased Mecp2 levels have been implicated in defects of synaptic contact formation and synaptic transmission.41, 54, 55, 56 Comparably, inherited mutations of Shank3, which also model ASD, result in reduced dendritic synaptic spine induction and maturation.57 Similar to post-mortem observations of FX patient brains, Fmr1 mice have abnormally thin and elongated dendritic spine morphology and greater spine density.58 Fmr1, the gene affected in FX, regulates the translation of messages important for activity-dependent synaptic modulation.59 Although a number of animal models of ASD recapitulate defects in synaptic maturation, the direction of the change varies depending upon the gene under investigation, which is consistent with the hypothesis that ASD is a spectrum of complex genetic disorders involving impaired developmental synaptic maturation, stabilization, elimination or pruning. Studies of mouse models of SCZD have also observed synaptic defects; there is reduced hippocampal synaptic transmission in Disc1 mice,42, 43 impaired synaptic maturation and function in Nrg1 mice60, 61, 62 and fewer cortical neurons with slightly smaller spines in mouse models of the human SCZD copy number variant at 22q11.2.63, 64, 65 In mice with reduced Reelin (Reln) expression (putative models of SCZD and BD), there is decreased dendritic spine maturation and plasticity, leading to decreased spine density,66 whereas Clock mice, a model of mania in BD, appear to have normal synaptic density.46

Particularly with respect to SCZD, aberrations in synaptic activity have also been observed in adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Similar to cortical embryonic development, where downregulation of Disc1 results in premature cell cycle exit of neural progenitor cells,67, 68 adult-born neurons with reduced Disc1 have hastened neural development. Disc1 knockdown results in accelerated dendritic development, soma hypertrophy, aberrant positioning and increased neural excitability.69, 70, 71 It remains unknown if aberrant adult neurogenesis contributes to psychiatric disease in humans.

Aberrant neuronal migration

In ASD patients, defects of migration can lead to a variety of morphological outcomes, particularly heterotopias and dysplastic changes. One recent pathological study identified a number of abnormalities and lesions in most of the ASD brains studied, including a loss of vertical and horizontal organization of cortical layers in some patients.72 It has been hypothesized that altered expression of cytoskeletal proteins and loss of neuronal polarity contribute to these cortical migration defects.73

Animal models also show phenotypes consistent with abnormal neuronal migration: mice with reduced Disc1 activity have reduced cortical migration,74Nrg1 mutant mice have reduced tangential neural migration from the ventral telencephalon44, 45 and Cntnap2-null mice have impaired migration of cortical projection neurons.75 Disc1 mutant mice have altered distribution of hippocampal mossy fiber terminals on CA3,42 and axons with Disc1 knockdown miss CA3 altogether and project onto CA1.70 dnDISC1 neurites have deficits in neurite repulsion in vitro.42 Although DISC1 is a rare SCZD allele, an understanding of the downstream targets or binding partners through which it mediates its cellular effects may identify drug targets relevant to the broader SCZD population. One putative downstream target of DISC1 is Glycogen Synthase 3-beta (Gsk3β),67Gsk3β functions within several central pathways (including cAMP and Wnt) is a direct target of lithium (a drug commonly used to treat BD)76, 77 and mounting evidence indicates that Gsk3β may be a central mediator of axon outgrowth dynamics.78 Cell-based assays will allow the study of the effects of Gsk3β, cAMP and WNT levels on neurite outgrowths and axon migration of live human neurons.

EVIDENCE FOR NETWORK PHENOTYPES IN PSYCHIATRIC DISORDER

While comparable neuronal phenotypes, particularly aberrant dendritic arborization, synaptic density and neuronal migration, are shared between ASD, SCZD and BD, these cellular phenotypes likely result in vastly different network effects in each disorder. Functional imaging facilitates the study of the abnormal neural circuitry behind cognitive dysfunction.

One hypothesis concerning ASD is that short-distance over-connectivity in the cortex leads to a failure of long-distance coupling.79 This hypothesis predicts that impaired long-distance connectivity in the cortex impedes information integration across diverse functional systems (emotional, sensory, autonomic, memory). Consistent with this prediction, fMRI studies of resting state brain activity have observed increased connectivity between proximal regions, such as the posterior cingulate and the parahippocampal gyrus,80 and decreased connectivity between the distal regions, such as the frontal cortex and the parietal lobe,81 the insular cortices and the somatosensory cortices or amygdala,82 the frontal cortex and the posterior cingulate,80 as well as decreased interhemispheric synchronization.83 Comparable defects in long-distance connectivity were found when ASD patients performed social and introspective tasks.84 Among ASD patients, a negative correlation exists between functional connectivity in these regions and severity of social and communication impairment.80, 82

Just as pathological studies of SCZD reported decreased frontal and temporal lobe volumes, early fMRI studies of SCZD patients revealed brain activity abnormalities in the frontal and temporal lobes.85, 86 More recent studies have further shown that SCZD patients exhibit cortical hyper-activity and hyper-connectivity of the prefrontal cortex at rest, but reduced activation of the medial prefrontal cortex during working memory tasks.87 While functional connectivity of the parietal cortex to the ventral prefrontal cortex is greater in SCZD, it is reduced to the dorsal prefrontal cortex.88 This is consistent with anatomical neuronal network maps, which reveal a loss of network ‘hubs’ in the frontal cortex, and increased connection distance. These network aberrations are thought to result from neurodevelopmental abnormalities impacting cortical organization.89

Although fMRI studies can reveal regions of the brain with aberrant activity in the disease state, they cannot elucidate the specific neuronal cell types affected. Therefore, pharmacological and post-mortem studies have generated hypotheses concerning the cell types affected by SCZD. Similar studies of ASD and BD have been less successful in identifying the specific cell types relevant to disease.

Good evidence now links aberrant neurotransmitter signaling to SCZD. Dopamine receptor antagonists reduce the symptoms of SCZD and evidence now links SCZD with increased dopamine receptor levels and sensitivity.90, 91 Comparably, glutamate-blocking drugs such as ketamine produce symptoms generally associated with SCZD,92 whereas the glutamate receptor2/3 agonist LY2140023 may ameliorate the symptoms of SCZD.93 Post-mortem studies of SCZD brains have found decreased glutamate receptor expression,94 whereas among GABAergic interneurons, a decrease in GAD67 and calcium-binding proteins was found. Changes in GABAergic neurons are particularly relevant as they are thought to produce gamma oscillations, which synchronize pyramidal neuron firing, an activity that is impaired in SCZD. Evidence in mice suggests that SCZD results, at least in part, from reduced excitatory glutamatergic input onto GABAergic inhibitory neurons.60, 95, 96 It remains unclear whether aberrant dopamine, glutamate or GABA signaling is the primary cause of SCZD, as aberrant activity of any neuronal cell type could affect neurotransmitter activity of the remaining cell types in the disease state.

In model organisms from Drosophila to mice, genes associated with ASD, SCZD and BD have been shown to regulate synaptic activity and plasticity. For example, a screen in Drosophila for genes critical in maintaining homeostatic modulation of synaptic transmission identified the SCZD gene Dysbindin(DTNBP1). Dtnbp1 acts presynaptically, in a dose-dependent manner, to regulate adaptive neural plasticity.97 In Mecp2 mice, although synapse formation, elimination and strengthening are normal, the experience-dependent phase of synapse remodeling is impaired98 and Mecp2 mice show altered activity-dependent neural gene expression.99 Cntnap2-null mice, lacking a gene associated with ASD, have reduced GABAergic neurons and decreased neuronal synchrony.100 Disc1 mice have reduced hippocampal synaptic transmission.42, 43Nrg1 mice have impaired synaptic maturation and function58, 60, 61, 62, 101 and 22q11.2 mice show altered short- and long-term synaptic plasticity as well as calcium kinetics in CA3 presynaptic terminals. Defects in synaptic plasticity at the cellular level likely contribute to the network aberrations observed in psychiatric disorders.

One characteristic network defect observed in SCZD is prepulse inhibition (PPI). PPI is a measure of sensory gating, in which a weaker prestimulus (prepulse) inhibits the reaction of an organism to a subsequent strong startling stimulus (pulse). Deficits in PPI are observed in Nrg1 mice60, 95 and are reversed by dopamine receptor antagonists.102, 103 Dtnbp1 mice display not only decreased PPI but also reduced evoked γ-activity, a second pattern seen in patients with SCZD.104 In humans, polymorphisms in circadian genes such as CLOCK convey risk for BD; mutant Clock mice also have dysfunctional γ-activity across limbic circuits, which can be improved by chronic lithium treatment.46

While PPI is attributed to glutamatergic activity, reduced γ-activity indicates abnormal GABAergic neurotransmission. Therefore, although pharmacological evidence implicates dopaminergic and glutamatergic neurons in SCZD, network analysis reveals defects in both glutamatergic and GABAergic activity in SCZD and BD. Aberrations originating in any one neuronal subtype would ultimately be expected to affect activity in other types of neurons and in a variety of brain regions. The ability to test synaptic activity in defined populations of human glutamatergic, GABAergic and dopaminergic neurons affected by ASD, SCZD or BD might help to elucidate the neuronal subtypes at the core of each disorder.

INTRODUCTION TO hiPSCS and iNEURONS

The transient expression of four factors (OCT3/4, KLF4, SOX2 and c-MYC) is sufficient to directly reprogram adult somatic cells into an iPSC state.105, 106, 107Because hiPSCs can be derived from adult patients after the development of disease, hiPSCs represent a potentially limitless source of human cells with which to study disease, even without knowing which genes are interacting to produce the disease state in an individual patient. Methods to efficiently differentiate pluripotent stem cells to neurons were developed initially in studies using human embryonic stem cells.108 Through the addition of various morphogens to recapitulate the cues of embryonic development, ESCs and iPSCs can be directed to differentiate to regional identities including forebrain,109midbrain/hindbrain110, 111 and spinal cord.112, 113 It is generally thought that every cell type present in vivo can be differentiated in vitro using hiPSCs, although methods for many remain unexplored or inefficient.

An alternative approach for generating patient-specific neurons to study complex psychiatric disorders is now possible. Expression of four factors (ASCL1, BRN2, MYT1L and NEUROD) can convert fibroblasts into functional iNeurons in vitro.114,115 The process is rapid, generating electrophysiologically mature neurons with functional synapses within 14 days, and it is efficient, yielding up to 8% neurons. To date, methods exist to transform fibroblasts directly to glutamatergic115 and dopaminergic neurons,116 but methods to generate GABAergic iNeurons have not yet been reported. The regional identity of each neurotransmitter subtype remains unclear.

Both hiPSC neurons and iNeurons have the capacity to generate vast numbers of live human neurons for the study of psychiatric disorders. Because iNeuron generation bypasses neuronal differentiation and maturation, hiPSC neurons are likely the best method by which to model developmental facets of disease. For example, if SCZD ultimately results from abnormal synaptic maturation, it is possible that direct reprogramming would bypass the developmental window in which the SCZD cellular phenotype can be observed in vitro. Additionally, as aberrant ASCL1, BRN2 and MYT1L have all been linked to neurological disease,117, 118, 119, 120 it is not unreasonable to predict that overexpression of one or more of these key neuronal genes might affect the initiation or progression of a psychiatric disorder in vitro. Conversely, the rapid experimental timeframe of iNeuron generation makes it an ideal system with which to study phenotypic effects in mature neurons. If ASD is indeed a disease of activity-dependent synaptic modulation rather than synaptic maturation, iNeurons represent a more direct cell type with which to assay network properties. As the efficiency of iNeuron generation increases, and spontaneous neuronal networks result, this method may facilitate robust and swift network analysis of ASD, SCZD and BD neurons. It is important to note that both strategies facilitate novel experiments of innate neuron-specific deficits in psychiatric disease that are not confounded by environmental factors, such as treatment history, drug and alcohol abuse or poverty, that typically plague clinical studies.

PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS RESULT IN hiPSC NEURONAL PHENOTYPES IN VITRO

While no reported studies have yet characterized iNeurons from patients with psychiatric disorders, a number of groups, including ours, have now published studies of hiPSC neurons derived from patients with ASD and SCZD. During neuronal differentiation of hiPSCs, a number of neuronal genes already implicated in ASD, SCZD and BD, such as transcription factors and chromatin modifiers like POU3F2 and ZNF804A and cell adhesion genes like NRXN1 andNLGN1,121 are upregulated, permitting comparisons of expression levels in diseased and healthy live human neurons.

Three groups have now generated hiPSCs from a total of seven RTT patients, representing a number of unique point mutations and deletions in the MeCP2gene (Q244X, 1155del 32, T158M, R306C,Δ3–4, R294X, V247X).122, 123, 124 None of the groups observed altered replication or differentiation of RTT hiPSCs or neural progenitor cells. Rather, consistent with animal and post-mortem patient studies, all three groups reported that neuronal soma size of RTT hiPSC neurons is reduced by approximately 10–20% compared with controls.122, 123, 124Furthermore, we observed that RTT hiPSC neurons have reduced spine density, decreased neuronal spontaneous calcium signaling and decreased spontaneous excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents. The reproducibility of these findings across three independent reports validates the use of hiPSC-based models. Furthermore, by demonstrating the ability to test drugs to rescue synaptic deficiency in RTT neurons, these studies hint at future uses of hiPSC neurons for high-throughout drug screening to identify new therapeutic drugs for psychiatric disorders.

FX is caused by the absence of expression of the fragile X mental retardation 1(FMR1) gene,125 which is believed to result from transcriptional silencing during embryonic development, owing to a CGG triplet-repeat expansion in the 5′ untranslated region of the gene.126 Although the somatic cells of three FX patients were successfully reprogrammed to pluripotency, the FMR1 gene remained inactive in all FX hiPSC lines, unlike FX embryonic stem cell lines. Consequently, the authors of this first report of FX hiPSCs concluded that ‘FX-iPSCs do not model the differentiation-dependent silencing of the FMR1 gene,’ and therefore chose not to assess their FX-hiPSC neurons for phenotypic abormalities.127 More recently, a second group generated hiPSCs from three patients (including one patient common to the first group) via nearly identical methods. They noted that a number of hiPSC lines had FMR1 CGG-repeat lengths that were clearly different from the original fibroblasts, and they also failed to detect FMR1 gene expression in the original FX fibroblasts or their FX hiPSCs.128Despite also not observing reactivated FMR1 expression in FX hiPSCs, this group compared neural differentiation of FX and control hiPSCs. They observed that neural cultures generated from FX hiPSCs consisted of neurons with fewer and shorter processes, as well as a larger number of glial cells with more compact morphology, suggesting that decreased FMR1 expression levels, rather than the slow silencing of FMR1 during neuronal differentiation, are sufficient to produce the disease state in FX.

Timothy syndrome is caused by a mutation in the L-type calcium channel Ca(v)1.2 and is associated with heart arrhythmias and ASD. From two patients with Timothy syndrome, hiPSC-derived cortical neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and neurons were generated. Neurons from these individuals were shown to have aberrant calcium signaling,129 while an earlier publication by this same group demonstrated that hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes from these same patients had irregular contraction, abnormal calcium transients and irregular electrical activity.130 Timothy syndrome hiPSC neurons underwent abnormal cortical differentiation, showing decreased expression of cortical genes and increased production of norepinephrine and DA. Notably, treatment with roscovitine, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and atypical L-type-channel blocker, was sufficient to ameliorate many characteristics of Timothy syndrome neurons in vitro.129

DISC1 mutations cause a rare monogenic form of SCZD. The generation of hiPSCs from SCZD patients with a DISC1 mutation have now been reported,131although neurons differentiated from these hiPSCs have not yet been characterized. We predict that DISC1–hiPSC-derived neurons will ultimately be shown to recapitulate the cellular phenotypes observed in dnDISC mice, just as RTT and FX-hiPSC neurons have replicated findings from mouse studies.

We recently reported neuronal phenotypes of hiPSC neurons from four patients with complex genetic forms of SCZD. When assayed by retrograde transmission of rabies virus neuronal labeling, SCZD-hiPSC neurons showed reduced neuronal connectivity and altered gene expression profiles.132 While nearly 25% of genes with altered expression had been previously implicated in SCZD, we also identified a number of new pathways that may contribute to SCZD. A second group has now reported an oxygen metabolism phenotype associated with SCZD;133 they observed a twofold increase in extra-mitochondrial oxygen consumption as well as elevated levels of reactive oxygen species in neural progenitor cells derived from hiPSCs from one SCZD patient relative to controls. Although a small study, this observation is consistent with animal studies134, 135and deserves attention. Oxygen metabolism defects have not been well demonstrated in human neurons, owing to a lack of live human cells for study. This is an excellent example of the type of hiPSC study that can investigate hypotheses not testable in human patients.

LIMITATION OF hiPSC-BASED MODELLING

A number of major limitations currently restrict hiPSC-based studies, particularly concerning the scalability of hiPSC generation, neural differentiation and phenotypic characterization of derived neurons and neural networks. These technical limitations have made it hard to accurately address the inherent variability of cell-based studies, which exist in three major forms: (1) neuron-to-neuron (intra-patient), (2) hiPSC-to-hiPSC (intra-patient) and (3) patient-to-patient (inter-patient). To produce meaningful data, each cell-based experiment should ideally compare multiple neuronal differentiations from multiple independent hiPSC lines from multiple patients. Owing to cost and time constraints, such large experiments have not yet been completed. Consequently, the hiPSC studies reported to date may ultimately prove to be proof-of-concept demonstrations until methods to compare derived neurons from hundred or thousands of patients and controls are refined.

Intra-patient variability results from differences between neurons and iPSCs generated from a single patient; it is the major constraint on signal to noise in cell-based experiments. Differences between individual hiPSC neurons derived from a single patient produce neuron-to-neuron variability. To some extent, this variability may be unavoidable, although it is currently exacerbated by the heterogeneity of cellular subtypes in hiPSC neural populations; none of the reports described in this review compare pure neuronal populations of a specific subtype. At the experimental level, neural subtype heterogeneity results because current neuronal differentiation protocols are not 100% efficient and, in contrast to the hematopoietic system, cell surface markers by which specific subtypes of neurons might be purified have not been developed. It is well established that individual hiPSC lines vary genetically, epigenetically and in terms of neural differentiation propensities to produce hiPSC-to-hiPSC variability. Genetic differences include the location and number of viral integrations produced during the reprogramming process and spontaneous mutations that have been observed during hiPSC generation and expansion.136 Epigenetic differences reflect the somatic cell type used for reprogramming and the completeness of its chromatin remodeling.137 Differences in developmental potential exist among human embryonic stem cell lines138 and between individual hiPSC lines.139

Inter-patient variability reflects the heterogeneity in clinical outcomes between patients with ASD, SCZD or BD. Consequently, given the small sample size (typically 1–4 patients) of the current hiPSC-based studies discussed in this review, a major concern is whether their findings are representative of the larger patient population. In the short term, this has been addressed by recruiting patients with well-defined clinical or genetic characteristics as well as matched healthy controls. Ultimately, methods will have to be developed to permit comparisons of thousands of patients.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS OF CELL-BASED STUDIES

Whole-brain disorders should be studied at the level of component aberrations of cells and neural networks. Neuroimaging, post-mortem anatomical and pharmacological studies of patients may be measuring consequences of the disease state, rather than its origin. Cell-based studies will lead to the discernment and characterization of the molecular causes of ASD, SCZD and BD and facilitate studies of the cellular and network phenotypes that serve as neuronal predispositions to disease. Furthermore, these studies confer the ability to test various neuron non-cell-autonomous effects, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, activity-dependent modulations and the influence of stress hormones in psychiatric disorders. High-throughput screening of new classes of compounds capable of pharmacological amelioration of neuronal and/or network phenotypes for treatment of these disorders is possible.

Small defects at the cellular level could ultimately manifest as complex psychiatric disorders with an array of symptoms in patients. For example, if neurons derived from psychiatric patients show a decrease in the absolute number of connections between cells, and if this phenotype is restricted to a specific subtype of neurons, this finding might hint at the central cell type relevant to the disease state. Because synaptic strength is highly modulated by synaptic activity, a decrease in the strength of individual connections between neurons in psychiatric patients could indicate aberrant synaptic activity or plasticity in patient brains. Finally, perturbed neuronal migration or axon targeting in vitro might suggest that mis-targeted neuronal connections, rather than decreased neuronal connectivity, is central to disease. Cellular phenotypes hint at the neuronal predispositions contributing to psychiatric disorders and may help to unlock the complexities of psychiatric illness.

While overlapping genetic susceptibilities might produce a common cellular phenotype, or predisposition, to psychiatric illness, clinical outcome may be determined by activity at the network level. Synaptic pruning (either whole brain or in specific regions) is an activity-dependent process that could generate the clinical differences distinguishing ASD, SCZD and BD. Cell-based studies of neuronal and network aberrations in psychiatric disorders may lead to predictions of activity-dependent environmental influences that contribute to disease progression.

Human iPSC- and iNeuron-based methods have the potential to simplify whole-brain disorders like ASD, SCZD and BD to their cellular and network components, contributing to our understanding of these conditions. Although many technical issues, particularly, concerning the scalability of hiPSC generation, neuronal differentiation and neural assays remain, we believe that studies of neuronal networks constructed from defined neuronal populations are feasible. By recapitulating and monitoring healthy and disease networks in a dish, it is likely that new methods of in vitro modeling of psychiatric disorders will result in new insights into the mechanism of disease initiation, progression and, ultimately, treatment.

Acknowledgements

The Gage Laboratory is partially funded by CIRM Grant RL1-00649-1, The Lookout and Mathers Foundation, the Helmsley Foundation as well as Sanofi-Aventis. We thank J Simon for illustrations and ML Gage for editorial comments.

Footnotes

Conflict Of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. 3rd ed., rev. edn. vol. 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. p. 886. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Giorgio FP, Boulting GL, Bobrowicz S, Eggan KC. Human embryonic stem cell-derived motor neurons are sensitive to the toxic effect of glial cells carrying an ALS-causing mutation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(6):637–648. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchetto MC, Muotri AR, Mu Y, Smith AM, Cezar GG, Gage FH. Non-cell-autonomous effect of human SOD1 G37R astrocytes on motor neurons derived from human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(6):649–657. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritvo ER, Freeman BJ, Mason-Brothers A, Mo A, Ritvo AM. Concordance for the syndrome of autism in 40 pairs of afflicted twins. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(1):74–77. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan PF, Kendler KS, Neale MC. Schizophrenia as a complex trait: evidence from a meta-analysis of twin studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(12):1187–1192. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuang MT, Stone WS, Faraone SV. Genes, environment and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2001;40:s18–s24. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.40.s18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bottenstein JE, Sato GH. Growth of a rat neuroblastoma cell line in serum-free supplemented medium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1979;76(1):514–517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benitez-King G, Riquelme A, Ortiz-Lopez L, Berlanga C, Rodriguez-Verdugo MS, Romo F, et al. A non-invasive method to isolate the neuronal linage from the nasal epithelium from schizophrenic and bipolar diseases. J Neurosci Methods. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matigian N, Abrahamsen G, Sutharsan R, Cook AL, Vitale AM, Nouwens A, et al. Disease-specific, neurosphere-derived cells as models for brain disorders. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3(11–12):785–798. doi: 10.1242/dmm.005447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carper RA, Moses P, Tigue ZD, Courchesne E. Cerebral lobes in autism: early hyperplasia and abnormal age effects. Neuroimage. 2002;16(4):1038–1051. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Courchesne E, Karns CM, Davis HR, Ziccardi R, Carper RA, Tigue ZD, et al. Unusual brain growth patterns in early life in patients with autistic disorder: an MRI study. Neurology. 2001;57(2):245–254. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hazlett HC, Poe M, Gerig G, Smith RG, Provenzale J, Ross A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and head circumference study of brain size in autism: birth through age 2 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(12):1366–1376. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Courchesne E, Mouton P, Calhoun M, Semendeferi K, Ahrens-Barbeau C, Hallet M, et al. Neuron Number and Size in Prefrontal Cortex of Children With Autism. JAMA. 2011;206(18):2001–2010. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Courchesne E, Press GA, Yeung-Courchesne R. Parietal lobe abnormalities detected with MR in patients with infantile autism. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160(2):387–393. doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.2.8424359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hadjikhani N, Joseph RM, Snyder J, Tager-Flusberg H. Anatomical differences in the mirror neuron system and social cognition network in autism. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16(9):1276–1282. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmitz N, Daly E, Murphy D. Frontal anatomy and reaction time in Autism. Neurosci Lett. 2007;412(1):12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.07.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brun CC, Nicolson R, Lepore N, Chou YY, Vidal CN, DeVito TJ, et al. Mapping brain abnormalities in boys with autism. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30(12):3887–3900. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frazier TW, Hardan AY. A meta-analysis of the corpus callosum in autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(10):935–941. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raymond GV, Bauman ML, Kemper TL. Hippocampus in autism: a Golgi analysis. Acta Neuropathol. 1996;91(1):117–119. doi: 10.1007/s004010050401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nature genetics. 1999;23(2):185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van den Veyver IB, Zoghbi HY. Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 mutations in Rett syndrome. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2000;10(3):275–279. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauman ML, Kemper TL, Arin DM. Pervasive neuroanatomic abnormalities of the brain in three cases of Rett's syndrome. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1581–1586. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.8.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castren M, Tervonen T, Karkkainen V, Heinonen S, Castren E, Larsson K, et al. Altered differentiation of neural stem cells in fragile X syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(49):17834–17839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508995102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhattacharyya A, McMillan E, Wallace K, Tubon TC, Jr, Capowski EE, Svendsen CN. Normal Neurogenesis but Abnormal Gene Expression in Human Fragile X Cortical Progenitor Cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17(1):107–117. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vita A, De Peri L, Silenzi C, Dieci M. Brain morphology in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of quantitative magnetic resonance imaging studies. Schizophr Res. 2006;82(1):75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steen RG, Mull C, McClure R, Hamer RM, Lieberman JA. Brain volume in first-episode schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:510–518. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.6.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright IC, Rabe-Hesketh S, Woodruff PW, David AS, Murray RM, Bullmore ET. Meta-analysis of regional brain volumes in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(1):16–25. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson PM, Vidal C, Giedd JN, Gochman P, Blumenthal J, Nicolson R, et al. Mapping adolescent brain change reveals dynamic wave of accelerated gray matter loss in very early-onset schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(20):11650–11655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201243998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellison-Wright I, Glahn DC, Laird AR, Thelen SM, Bullmore E. The anatomy of first-episode and chronic schizophrenia: an anatomical likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(8):1015–1023. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07101562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajkowska G, Selemon LD, Goldman-Rakic PS. Neuronal and glial somal size in the prefrontal cortex: a postmortem morphometric study of schizophrenia and Huntington disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(3):215–224. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolomeets NS, Orlovskaya DD, Rachmanova VI, Uranova NA. Ultrastructural alterations in hippocampal mossy fiber synapses in schizophrenia: a postmortem morphometric study. Synapse. 2005;57(1):47–55. doi: 10.1002/syn.20153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Black JE, Kodish IM, Grossman AW, Klintsova AY, Orlovskaya D, Vostrikov V, et al. Pathology of layer V pyramidal neurons in the prefrontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):742–744. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selemon LD, Goldman-Rakic PS. The reduced neuropil hypothesis: a circuit based model of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00281-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karchemskiy A, Garrett A, Howe M, Adleman N, Simeonova DI, Alegria D, et al. Amygdalar, hippocampal, and thalamic volumes in youth at high risk for development of bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frazier JA, Chiu S, Breeze JL, Makris N, Lange N, Kennedy DN, et al. Structural brain magnetic resonance imaging of limbic and thalamic volumes in pediatric bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(7):1256–1265. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edmiston EE, Wang F, Kalmar JH, Womer FY, Chepenik LG, Pittman B, et al. Lateral ventricle volume and psychotic features in adolescents and adults with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajkowska G, Halaris A, Selemon LD. Reductions in neuronal and glial density characterize the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(9):741–752. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pantazopoulos H, Lange N, Baldessarini RJ, Berretta S. Parvalbumin neurons in the entorhinal cortex of subjects diagnosed with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(5):640–652. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen RZ, Akbarian S, Tudor M, Jaenisch R. Deficiency of methyl-CpG binding protein-2 in CNS neurons results in a Rett-like phenotype in mice. Nature genetics. 2001;27(3):327–331. doi: 10.1038/85906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kishi N, Macklis JD. MECP2 is progressively expressed in post-migratory neurons and is involved in neuronal maturation rather than cell fate decisions. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2004;27(3):306–321. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smrt RD, Eaves-Egenes J, Barkho BZ, Santistevan NJ, Zhao C, Aimone JB, et al. Mecp2 deficiency leads to delayed maturation and altered gene expression in hippocampal neurons. Neurobiology of disease. 2007;27(1):77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kvajo M, McKellar H, Arguello PA, Drew LJ, Moore H, MacDermott AB, et al. A mutation in mouse Disc1 that models a schizophrenia risk allele leads to specific alterations in neuronal architecture and cognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(19):7076–7081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802615105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li W, Zhou Y, Jentsch JD, Brown RA, Tian X, Ehninger D, et al. Specific developmental disruption of disrupted-in-schizophrenia-1 function results in schizophrenia-related phenotypes in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(46):18280–18285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706900104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lopez-Bendito G, Cautinat A, Sanchez JA, Bielle F, Flames N, Garratt AN, et al. Tangential neuronal migration controls axon guidance: a role for neuregulin-1 in thalamocortical axon navigation. Cell. 2006;125(1):127–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krivosheya D, Tapia L, Levinson JN, Huang K, Kang Y, Hines R, et al. ErbB4-neuregulin signaling modulates synapse development and dendritic arborization through distinct mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(47):32944–32956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800073200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dzirasa K, Coque L, Sidor MM, Kumar S, Dancy EA, Takahashi JS, et al. Lithium ameliorates nucleus accumbens phase-signaling dysfunction in a genetic mouse model of mania. J Neurosci. 2010;30(48):16314–16323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4289-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sudhof TC. Neuroligins and neurexins link synaptic function to cognitive disease. Nature. 2008;455(7215):903–911. doi: 10.1038/nature07456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hutsler JJ, Zhang H. Increased dendritic spine densities on cortical projection neurons in autism spectrum disorders. Brain Res. 2010;1309:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chapleau CA, Calfa GD, Lane MC, Albertson AJ, Larimore JL, Kudo S, et al. Dendritic spine pathologies in hippocampal pyramidal neurons from Rett syndrome brain and after expression of Rett-associated MECP2 mutations. Neurobiology of disease. 2009;35(2):219–233. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Irwin SA, Patel B, Idupulapati M, Harris JB, Crisostomo RA, Larsen BP, et al. Abnormal dendritic spine characteristics in the temporal and visual cortices of patients with fragile-X syndrome: a quantitative examination. Am J Med Genet. 2001;98(2):161–167. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20010115)98:2<161::aid-ajmg1025>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garey LJ, Ong WY, Patel TS, Kanani M, Davis A, Mortimer AM, et al. Reduced dendritic spine density on cerebral cortical pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65(4):446–453. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.4.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glantz LA, Lewis DA. Decreased dendritic spine density on prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(1):65–73. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kolomeets NS, Orlovskaya DD, Uranova NA. Decreased numerical density of CA3 hippocampal mossy fiber synapses in schizophrenia. Synapse. 2007;61(8):615–621. doi: 10.1002/syn.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Asaka Y, Jugloff DG, Zhang L, Eubanks JH, Fitzsimonds RM. Hippocampal synaptic plasticity is impaired in the Mecp2-null mouse model of Rett syndrome. Neurobiology of disease. 2006;21(1):217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moretti P, Levenson JM, Battaglia F, Atkinson R, Teague R, Antalffy B, et al. Learning and memory and synaptic plasticity are impaired in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. J Neurosci. 2006;26(1):319–327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2623-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nelson ED, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM. MeCP2-dependent transcriptional repression regulates excitatory neurotransmission. Curr Biol. 2006;16(7):710–716. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Durand CM, Perroy J, Loll F, Perrais D, Fagni L, Bourgeron T, et al. SHANK3 mutations identified in autism lead to modification of dendritic spine morphology via an actin-dependent mechanism. Molecular psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Comery TA, Harris JB, Willems PJ, Oostra BA, Irwin SA, Weiler IJ, et al. Abnormal dendritic spines in fragile X knockout mice: maturation and pruning deficits. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(10):5401–5404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weiler IJ, Spangler CC, Klintsova AY, Grossman AW, Kim SH, Bertaina-Anglade V, et al. Fragile X mental retardation protein is necessary for neurotransmitter-activated protein translation at synapses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(50):17504–17509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407533101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barros CS, Calabrese B, Chamero P, Roberts AJ, Korzus E, Lloyd K, et al. Impaired maturation of dendritic spines without disorganization of cortical cell layers in mice lacking NRG1/ErbB signaling in the central nervous system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(11):4507–4512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900355106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pitcher GM, Beggs S, Woo RS, Mei L, Salter MW. ErbB4 is a suppressor of long-term potentiation in the adult hippocampus. Neuroreport. 2008;19(2):139–143. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f3da10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen YJ, Zhang M, Yin DM, Wen L, Ting A, Wang P, et al. ErbB4 in parvalbumin-positive interneurons is critical for neuregulin 1 regulation of long-term potentiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(50):21818–21823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010669107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fenelon K, Mukai J, Xu B, Hsu PK, Drew LJ, Karayiorgou M, et al. Deficiency of Dgcr8, a gene disrupted by the 22q11.2 microdeletion, results in altered short-term plasticity in the prefrontal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(11):4447–4452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101219108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Earls LR, Bayazitov IT, Fricke RG, Berry RB, Illingworth E, Mittleman G, et al. Dysregulation of presynaptic calcium and synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of 22q11 deletion syndrome. J Neurosci. 2010;30(47):15843–15855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1425-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sigurdsson T, Stark KL, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA, Gordon JA. Impaired hippocampal-prefrontal synchrony in a genetic mouse model of schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;464(7289):763–767. doi: 10.1038/nature08855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pappas GD, Kriho V, Pesold C. Reelin in the extracellular matrix and dendritic spines of the cortex and hippocampus: a comparison between wild type and heterozygous reeler mice by immunoelectron microscopy. J Neurocytol. 2001;30(5):413–425. doi: 10.1023/a:1015017710332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mao Y, Ge X, Frank CL, Madison JM, Koehler AN, Doud MK, et al. Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 regulates neuronal progenitor proliferation via modulation of GSK3beta/beta-catenin signaling. Cell. 2009;136(6):1017–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singh KK, Ge X, Mao Y, Drane L, Meletis K, Samuels BA, et al. Dixdc1 is a critical regulator of DISC1 and embryonic cortical development. Neuron. 2010;67(1):33–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duan X, Chang JH, Ge S, Faulkner RL, Kim JY, Kitabatake Y, et al. Disrupted-In-Schizophrenia 1 regulates integration of newly generated neurons in the adult brain. Cell. 2007;130(6):1146–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Faulkner RL, Jang MH, Liu XB, Duan X, Sailor KA, Kim JY, et al. Development of hippocampal mossy fiber synaptic outputs by new neurons in the adult brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(37):14157–14162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806658105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim JY, Duan X, Liu CY, Jang MH, Guo JU, Pow-anpongkul N, et al. DISC1 regulates new neuron development in the adult brain via modulation of AKT-mTOR signaling through KIAA1212. Neuron. 2009;63(6):761–773. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wegiel J, Kuchna I, Nowicki K, Imaki H, Marchi E, Ma SY, et al. The neuropathology of autism: defects of neurogenesis and neuronal migration, and dysplastic changes. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119(6):755–770. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0655-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rorke LB. A perspective: the role of disordered genetic control of neurogenesis in the pathogenesis of migration disorders. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1994;53(2):105–117. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kamiya A, Kubo K, Tomoda T, Takaki M, Youn R, Ozeki Y, et al. A schizophrenia-associated mutation of DISC1 perturbs cerebral cortex development. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(12):1167–1178. doi: 10.1038/ncb1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Minshew NJ. Cortical activation and synchronization during sentence comprehension in high-functioning autism: evidence of underconnectivity. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 8):1811–1821. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ruiz i Altaba A, Melton DA. Involvement of the Xenopus homeobox gene Xhox3 in pattern formation along the anterior-posterior axis. Cell. 1989;57(2):317–326. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90969-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.O'Brien WT, Klein PS. Validating GSK3 as an in vivo target of lithium action. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37(Pt 5):1133–1138. doi: 10.1042/BST0371133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim WY, Zhou FQ, Zhou J, Yokota Y, Wang YM, Yoshimura T, et al. Essential roles for GSK-3s and GSK-3-primed substrates in neurotrophin-induced and hippocampal axon growth. Neuron. 2006;52(6):981–996. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Courchesne E, Redcay E, Morgan JT, Kennedy DP. Autism at the beginning: microstructural and growth abnormalities underlying the cognitive and behavioral phenotype of autism. Dev Psychopathol. 2005;17(3):577–597. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Monk CS, Peltier SJ, Wiggins JL, Weng SJ, Carrasco M, Risi S, et al. Abnormalities of intrinsic functional connectivity in autism spectrum disorders. Neuroimage. 2009;47(2):764–772. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kennedy DP, Courchesne E. The intrinsic functional organization of the brain is altered in autism. Neuroimage. 2008;39(4):1877–1885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ebisch SJ, Gallese V, Willems RM, Mantini D, Groen WB, Romani GL, et al. Altered intrinsic functional connectivity of anterior and posterior insula regions in high-functioning participants with autism spectrum disorder. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011;32(7):1013–1028. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dinstein I, Pierce K, Eyler L, Solso S, Malach R, Behrmann M, et al. Disrupted neural synchronization in toddlers with autism. Neuron. 2011;70(6):1218–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kennedy DP, Courchesne E. Functional abnormalities of the default network during self- and other-reflection in autism. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2008;3(2):177–190. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsn011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yurgelun-Todd DA, Renshaw PF, Gruber SA, Ed M, Waternaux C, Cohen BM. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the temporal lobes in schizophrenics and normal controls. Schizophr Res. 1996;19(1):55–59. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(95)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yurgelun-Todd DA, Waternaux CM, Cohen BM, Gruber SA, English CD, Renshaw PF. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of schizophrenic patients and comparison subjects during word production. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(2):200–205. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Thermenos HW, Milanovic S, Tsuang MT, Faraone SV, McCarley RW, et al. Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(4):1279–1284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809141106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tan HY, Sust S, Buckholtz JW, Mattay VS, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Egan MF, et al. Dysfunctional prefrontal regional specialization and compensation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1969–1977. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bassett DS, Bullmore E, Verchinski BA, Mattay VS, Weinberger DR, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Hierarchical organization of human cortical networks in health and schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2008;28(37):9239–9248. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1929-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kessler RM, Woodward ND, Riccardi P, Li R, Ansari MS, Anderson S, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor levels in striatum, thalamus, substantia nigra, limbic regions, and cortex in schizophrenic subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(12):1024–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Owen F, Cross AJ, Crow TJ, Longden A, Poulter M, Riley GJ. Increased dopamine-receptor sensitivity in schizophrenia. Lancet. 1978;2(8083):223–226. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)91740-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Krystal JH, Karper LP, Seibyl JP, Freeman GK, Delaney R, Bremner JD, et al. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans. Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(3):199–214. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Patil ST, Zhang L, Martenyi F, Lowe SL, Jackson KA, Andreev BV, et al. Activation of mGlu2/3 receptors as a new approach to treat schizophrenia: a randomized Phase 2 clinical trial. Nature medicine. 2007;13(9):1102–1107. doi: 10.1038/nm1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Meador-Woodruff JH, Healy DJ. Glutamate receptor expression in schizophrenic brain. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;31(2–3):288–294. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li B, Woo RS, Mei L, Malinow R. The neuregulin-1 receptor erbB4 controls glutamatergic synapse maturation and plasticity. Neuron. 2007;54(4):583–597. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stefansson H, Sigurdsson E, Steinthorsdottir V, Bjornsdottir S, Sigmundsson T, Ghosh S, et al. Neuregulin 1 and susceptibility to schizophrenia. American journal of human genetics. 2002;71(4):877–892. doi: 10.1086/342734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dickman DK, Davis GW. The schizophrenia susceptibility gene dysbindin controls synaptic homeostasis. Science (New York, NY. 2009;326(5956):1127–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.1179685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Noutel J, Hong YK, Leu B, Kang E, Chen C. Experience-dependent retinogeniculate synapse remodeling is abnormal in MeCP2-deficient mice. Neuron. 2011;70(1):35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dani VS, Chang Q, Maffei A, Turrigiano GG, Jaenisch R, Nelson SB. Reduced cortical activity due to a shift in the balance between excitation and inhibition in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(35):12560–12565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506071102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Penagarikano O, Abrahams BS, Herman EI, Winden KD, Gdalyahu A, Dong H, et al. Absence of CNTNAP2 Leads to Epilepsy, Neuronal Migration Abnormalities, and Core Autism-Related Deficits. Cell. 2011;147(1):235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pitcher GM, Kalia LV, Ng D, Goodfellow NM, Yee KT, Lambe EK, et al. Schizophrenia susceptibility pathway neuregulin 1-ErbB4 suppresses Src upregulation of NMDA receptors. Nature medicine. 2011;17(4):470–478. doi: 10.1038/nm.2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR, Mansbach RS, Braff DL. Startle response models of sensorimotor gating and habituation deficits in schizophrenia. Brain Res Bull. 1990;25(3):485–498. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90241-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Caine SB, Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR. Effects of D3/D2 dopamine receptor agonists and antagonists on prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;12(2):139–145. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(94)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Carlson GC, Talbot K, Halene TB, Gandal MJ, Kazi HA, Schlosser L, et al. From the Cover: Dysbindin-1 mutant mice implicate reduced fast-phasic inhibition as a final common disease mechanism in schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(43):E962–E970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109625108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science (New York, NY. 2007;318(5858):1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tropepe V, Hitoshi S, Sirard C, Mak TW, Rossant J, van der Kooy D. Direct neural fate specification from embryonic stem cells: a primitive mammalian neural stem cell stage acquired through a default mechanism. Neuron. 2001;30(1):65–78. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Watanabe K, Kamiya D, Nishiyama A, Katayama T, Nozaki S, Kawasaki H, et al. Directed differentiation of telencephalic precursors from embryonic stem cells. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(3):288–296. doi: 10.1038/nn1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kawasaki H, Mizuseki K, Nishikawa S, Kaneko S, Kuwana Y, Nakanishi S, et al. Induction of midbrain dopaminergic neurons from ES cells by stromal cell-derived inducing activity. Neuron. 2000;28(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Perrier AL, Tabar V, Barberi T, Rubio ME, Bruses J, Topf N, et al. Derivation of midbrain dopamine neurons from human embryonic stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(34):12543–12548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Li XJ, Du ZW, Zarnowska ED, Pankratz M, Hansen LO, Pearce RA, et al. Specification of motoneurons from human embryonic stem cells. Nature biotechnology. 2005;23(2):215–221. doi: 10.1038/nbt1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wichterle H, Lieberam I, Porter JA, Jessell TM. Directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells into motor neurons. Cell. 2002;110(3):385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00835-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Pang ZP, Kokubu Y, Sudhof TC, Wernig M. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature. 2010;463(7284):1035–1041. doi: 10.1038/nature08797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pang ZP, Yang N, Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Fuentes DR, Yang TQ, et al. Induction of human neuronal cells by defined transcription factors. Nature. 2011;476(7359):220–223. doi: 10.1038/nature10202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kim J, Su SC, Wang H, Cheng AW, Cassady JP, Lodato MA, et al. Functional Integration of Dopaminergic Neurons Directly Converted from Mouse Fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]