Abstract

BACKGROUND

The objective of this study was to test cladribine (2-CDA) alone and in combination with rituximab in patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

METHODS

Patients with MCL were treated on 2 sequential trials. In Trial 95-80-53, patients received 2-CDA as initial therapy or at relapse. In Trial N0189, patients received combination 2-CDA and rituximab as initial therapy. In both trials, 2-CDA was administered at a dose of 5 mg/m2 intravenously on Days 1 through 5 every 4 weeks for 2 to 6 cycles, depending on response. In Trial N0189, rituximab 375 mg/m2 was administered on Day 1 of each cycle.

RESULTS

Results were reported for 80 patients. Twenty-six previously untreated patients and 25 patients who had recurrent disease with a median age of 68 years received single-agent 2-CDA. The overall response rate (ORR) was 81% with 42% complete responses (CRs) in the previously untreated group. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 13.6 months (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 7.2–22.1 months), and 81% of patients remained alive at 2 years. The ORR was 46% with a 21% CR rate in the recurrent disease group. The median PFS was 5.4 months (95% CI, 4.6–13.1 months), and 36% of patients remained alive at 2 years. Twenty-nine eligible patients with a median age of 70 years received 2-CDA plus rituximab. The ORR was 66% (19 of 29 patient), and the CR rate was 52% (15 of 29 patients). The median duration of response for patients who achieved a CR had not been reached at the time of the current report, and only 3 of the patients who achieved a CR developed recurrent disease at a median follow-up of 21.5 months.

CONCLUSIONS

2-CDA had substantial single-agent activity in both recurrent and untreated MCL, and the results indicated that it may be administered safely to elderly patients. The addition of rituximab to 2-CDA may increase the duration of response.

Keywords: mantle cell lymphoma, cladribine, response duration, rituximab

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a poor-prognosis lymphoma with a predilection for elderly men that comprises 8% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) cases.1,2 The characteristic immunophenotype is CD20+, CD10−, CD5+, and CD23−. A t(11;14) (q13;q32) chromosomal translocation that juxtaposes the cyclin D1 gene to the immunoglobulin heavy-chain (CCND1-IGH) enhancer region, resulting in overexpression of cyclin D1, typically is present.3–5

There is no standard or curative therapy for MCL. The regimens used vary by patient age and eligibility for autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). Hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone with rituximab (R–hyper-CVAD) or without rituximab (hyper-CVAD) produces high response rates and has been used alone or followed by ASCT but is not recommended for patients aged >65 years.6,7 Rituximab combined with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) is a common regimen with a 34% to 48% complete response (CR) rate and a median time to progression (TTP) of 16 months.8,9 It was reported that ASCT in first remission after CHOP induction yielded a 81% CR rate with promising progression-free survival (PFS) in patients who were in CR before ASCT.10

Many patients with MCL are not eligible for ASCT or intensive regimens such as R–hyper-CVAD because of advanced age or comorbidities. Other patients are reluctant to be treated on aggressive regimens. The purine nucleoside analogues typically are tolerated well and are used extensively in indolent B-cell malignancies.11 The 2 studies described in the current report were designed to determine the efficacy and toxicity of cladribine (2-CDA)-based therapy for MCL in patients who were not considered eligible for dose-intense therapy or who preferred a less aggressive approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Eligibility

Patients were eligible if they were aged ≥18 years, had measurable or evaluable MCL, had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score ≤3, and had a life expectancy ≥12 weeks. Central pathology review confirmed the diagnosis of MCL before study entry. The diagnostic criteria were the same for both studies and required demonstration of either cyclin D1 overexpression by immunohistochemistry or molecular evidence of a CCND1-IGH translocation in addition to characteristic immunophenotypic and morphologic findings. Ki-67 staining was not done routinely. Patients with central nervous system involvement or with a life expectancy <12 weeks were ineligible.

Trial 95-80-53 accepted patients who were previously treated or untreated; Trial N0189 enrolled only untreated patients. Previously treated patients could not have received a purine nucleoside analog. The institutional review boards of all participating institutions in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) approved these trials, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient before study entry.

Study Design

In Trial 95-80-53, patients received 2-CDA 5 mg/m2 intravenously over 2 hours on Days 1 through 5 every 28 days. Prophylactic filgrastim was not allowed. Patients were to receive 2 cycles and would be restaged. Patients in CR or who were stable after 2 cycles of treatment went to observation; those in PR or who had a minor response (defined as a 25%–50% reduction in the measurable lesions) received 2 additional cycles. After 4 cycles, patients who had achieved a CR or those who had no further response had treatment discontinued and were observed; patients who had further improvement received Cycles 5 and 6 and then went to observation. There was no maintenance therapy. Patients who experienced episodes of Common Toxicity Criteria (version 2.0) grade ≥3 nonhematologic toxicity (except fever, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal, or infection) went off treatment. If the patient experienced grade 4 fever, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal, or infection at any time, then treatment was discontinued. Dose adjustments and delays for neutropenia and/or thrombocytopenia were specified.

Trial 95-80-53 was designed before the International Workshop guidelines of 1999 and originally included a minor response category that was defined as a reduction ≥25% but <50% in the sum of the products of the greatest perpendicular dimensions of the indicator lesion(s) documented for at least 4 weeks.12 Results of this trial will be reported according to the International Workshop guidelines to allow for comparison with other trials.

In Trial N0189, patients received the same regimen of 2-CDA with the addition of rituximab 375 mg/m2 intravenously on Day 1 of each cycle and either pegfilgrastim 6 mg subcutaneously on Day 6 or subcutaneous filgrastim on Days 6 through 15. The schema for treatment was similar to that for Trial 95-80-53 with a few exceptions. Patients with a CR or an unconfirmed CR after 2 cycles received 2 additional cycles and then went to observation. Patients who achieved a PR after 2 cycles received 2 additional cycles and were restaged; if no further improvement occurred, then they went to observation; those with improvement or CR received 2 additional cycles for a total of 6 cycles. Patients with stable disease after 2 cycles went to observation. There was no minor response category; therefore, a patient with less than a PR after 2 cycles was classified as having stable disease and went to observation. Patients remained on observation until progression or the initiation of alternative therapy, which was treated as progression for statistical purposes. The response criteria were according to the International Workshop guidelines.

Statistical Methods

The trial of single-agent 2-CDA had a 2-stage design for each patient population. The objective was to achieve an ORR of 30% in the recurrent disease group and 55% in the previously untreated group. The trial of 2-CDA plus rituximab was designed as a 1-stage, Phase II trial, and the goal was to achieve a CR rate of 65%. The accrual goal was 28 patients, and 15 CRs were required to deem the regimen worth pursuing in future studies. The study design for each of the 3 cohorts was chosen to provide at least 90% power for detecting the proposed true response proportion at a significance level (P) ≤.10.

All patients who met the eligibility criteria, signed a consent form, and began treatment were considered assessable for estimation of the response rate, the distribution of PFS, and the distribution of overall survival (OS). Confidence intervals (CIs) for the true response rate were constructed using the Duffy-Santner approach.13 The duration of treatment response was defined as the time from the date of the first observed CR until the date at which disease progression was noted. PFS was defined as the time from registration to disease progression. Patients who died without documentation of progression were considered to have had tumor progression on the date of death unless documented evidence clearly indicated that no progression occurred. Survival was defined as the time from registration to death. The times to event distributions were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.14

RESULTS

Eighty-one patients were accrued. One patient was lost to follow-up after 1 cycle of therapy, and a second patient was deemed ineligible, leaving 79 eligible patients with full follow-up (Table 1). Most patients were men (81% overall), the median ages were 68 years and 70 years in the 2 studies, and most patients had stage III or IV disease at study entry. The majority of patients had an International Prognostic Index ≥2. The response rates determined for all 3 groups are reported in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Patients Who Received Cladribine-based Therapy

| No. of patients (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-agent 2-CDA(NCCTG 95-80-53) |

2-CDA/Rituximab (NCCTG N0189) |

||

| Characteristic | Recurrent MCL (n = 24) |

Previously untreated MCL (n = 26) |

Previously untreated MCL (n = 29) |

| Median age [range], y | 68 [39–81] | 68 [42–81] | 70 [41–86] |

| Men | 20 (83) | 23 (89) | 21 (72) |

| Performance score | |||

| 0 | 12 (50) | 19 (73) | 16 (55) |

| 1 | 7 (29) | 6 (23) | 12 (41) |

| 2 | 5 (21) | 1 (4) | 1 (3.5) |

| Tumor stage | |||

| I/II | 6 (25) | 3 (12) | 3 (10) |

| III/IV | 18 (75) | 23 (88) | 26 (90) |

| Elevated LDH | 5 (21) | 8 (31) | 10 (34) |

| No. of extranodal sites | |||

| 0–1 | 12 (50) | 17 (65) | 11 (38) |

| ≥2 | 12 (50) | 9 (35) | 18 (62) |

| International Prognostic Factor Index | |||

| 0 | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 1 | 4 (17) | 8 (31) | 3 (10) |

| 2 | 9 (38) | 9 (35) | 10 (35) |

| 3 | 4 (17) | 7 (27) | 12 (41) |

| 4 | 4 (17) | 2 (8) | 4 (14) |

| 5 | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

2-CDA indicates cladribine; NCCTG, North Central Cancer Therapy Group; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

TABLE 2.

Response of Mantle Cell Lymphoma to Cladribine-based Therapy by Study

| No. of patients (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-agent 2-CDA (NCCTG 95-80-53) |

2-CDA/Rituximab (NCCTG N0189) |

||

| Response criteria | Recurrent MCL (n = 24) |

Previously untreated MCL (n = 26) |

Previously untreated MCL (n = 29) |

| Overall response | 11 (46) | 21 (81) | 19 (66) |

| Complete response | 5 (21) | 11 (42) | 15 (52) |

| Partial response | 6 (25) | 10 (39) | 4 (14) |

| Stable | 6 (25) | 2 (8) | 7 (24) |

| Progression on therapy | 7 (29) | 3 (12) | 3 (10) |

| Median time to progression, mo | 5.4 | 13.6 | 12.1 |

| Median overall survival, y | 1.9 | 4.7 | Not reached |

| %Progression free at 5 y | (4) | (12) | Not reached |

| %Progression free at 2 y | (8) | (21) | (43) |

| %Alive at 2 y | (36) | (81) | (78) |

| Alive at last follow-up | 3 (13) | 8 (31) | 23 (79) |

| Cause of death Lymphoma | 14 (58) | 14 (54) | 5 (17) |

| Other/unknown | 7 (29) | 4 (15) | 1 (4) |

2-CDA indicates cladribine; NCCTG, North Central Cancer Therapy Group; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma.

Recurrent MCL

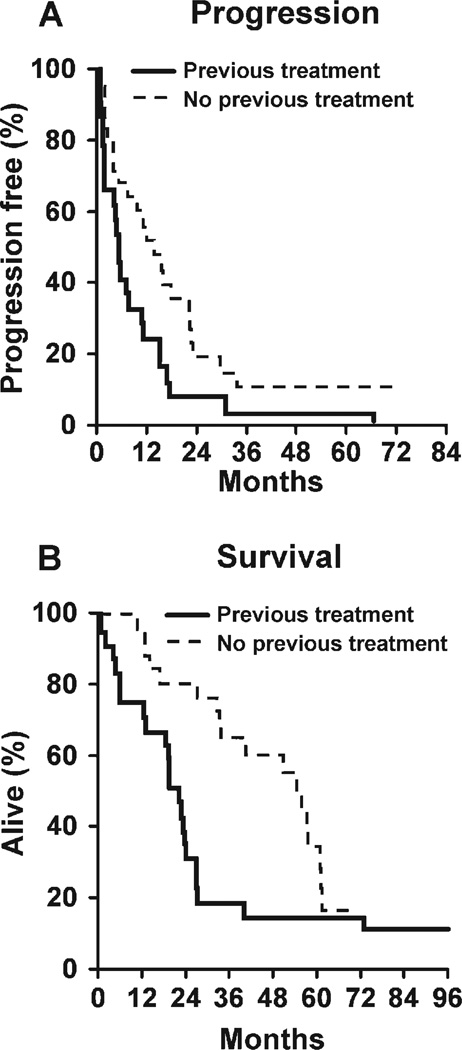

Expert pathology review prospectively identified 3 cases of mantle zone variant, 2 cases of blastoid variant, 1 case of nodular variant, and 18 cases of diffuse variant MCL. Single-agent 2-CDA for recurrent MCL demonstrated an overall response rate (ORR) of 46% (11 of 24 patients; 95% CI, 26%–66%) with a 25% PR rate and a 21% CR rate. One patient was lost to follow-up after a single cycle of therapy and was not evaluable for response. He was considered stable for the purpose of this analysis. The median PFS was 5.4 months (Fig. 1). Patients were followed until death or for a median of 6.3 years (range, 6.2–8.3 years). The 2-year survival rate was 36% (95% CI, 21%–61%), and the median OS was 1.9 years (95% CI, 1.6–2.2 years). At last follow-up, all but 2 patients had progressed, and 3 remained alive. The median PFS was 5.4 months (95% CI, 4.6–13.1 months), and 25% of patients (95% CI, 13%–50%) were progression free at 1 year.

FIGURE 1.

Progression-free and overall survival of patients with newly diagnosed or recurrent mantle cell lymphoma who received cladribine.

Patients received a median of 2 cycles of 2-CDA (range, 1–6 cycles). Seven patients had progressed by restaging after Cycle 2.

Cladribine was well tolerated (Table 3). Doses were delayed for 10 cycles in 6 patients and were modified for 5 patients because of hematologic toxicity. The reasons for discontinuation of treatment were completion according to the protocol (58%), progression (33%), toxicity (4%), and patient refusal (4%). The cause of death was disease related for 14 of the 21 patients (67%). The nondisease-related causes of death were diffuse alveolar hemorrhage from bone marrow transplantation, pulmonary embolism, Nocardia infection, and unknown (4 patients).

TABLE 3.

Grade 3 and 4 Toxicities Possibly, Probably, or Definitely Related to Cladribine-based Therapy for Mantle Cell Lymphoma That Occurred in >10% of Patients

| Percent of patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-agent 2-CDA (NCCTG 95-80-53) |

2-CDA/Rituximab (NCCTG N0189) |

||

| Adverse event | Relapsed MCL (n = 24) |

Previously untreated MCL (n = 26) |

Previously untreated MCL (n = 29) |

| Neutropenia | |||

| Grade 3 | 29 | 38 | 7 |

| Grade 4 | 21 | 15 | 24 |

| Thrombocytopenia | |||

| Grade 3 | 13 | 8 | 14 |

| Grade 4 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

2-CDA indicates cladribine; NCCTG, North Central Cancer Therapy Group; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma.

Initial Therapy With Single-agent 2-CDA

An expert pathology review prospectively identified 3 cases of mantle zone variant, 1 case of blastoid variant, 5 cases of nodular variant, and 17 cases of diffuse variant MCL. Single-agent 2-CDA produced an ORR of 81% (21 of 26 patients; 95% CI, 61%–93%) with a 39% PR rate and a 42% CR rate. Patients were followed until death or for a median of 4.4 years (range, 3.1–5.9 years). The median response duration was 16.5 months. The median PFS was 13.6 months (95% CI, 7.2–22.1 months), 50% of patients were progression free at 1 year (95% CI, 34%–73%), and 21% of patients were progression free at 2 years. The 2-year survival rate was 81% (95% CI, 67%–97%), and the median OS was 4.7 years (95% CI, 2.8–5.2 years). At last contact, 8 patients (31%) remained alive, and 3 patients (12%) remained progression free at 5 years.

The median number of cycles received was 4 (range, 1–6 cycles). Three patients had disease progression identified while on treatment. Doses were delayed for 21 cycles in 14 patients and were modified for 6 patients because of hematologic toxicity (Table 3). The reasons for discontinuation of treatment were completion according to the protocol (69%), progression (19%), and toxicity (12%). The cause of death was related to disease for 14 of 18 patient deaths (78%). The nondisease-related causes of death were esophageal cancer, respiratory failure, and unknown (2 patients).

Initial Therapy with 2-CDA/Rituximab

Between April 2003 and September 2005, 30 patients were accrued to the trial of rituximab and 2-CDA. One patient was deemed a major violation and was excluded from all analyses, leaving 29 eligible patients (Table 1). A preliminary pilot study to assess toxicity of the regimen accrued 6 of the 29 patients. Prophylactic pegfilgrastim or filgrastim support was added because of 2 grade 4 neutropenia events that occurred during the first cycle of treatment in the pilot for the subsequent 23 patients.

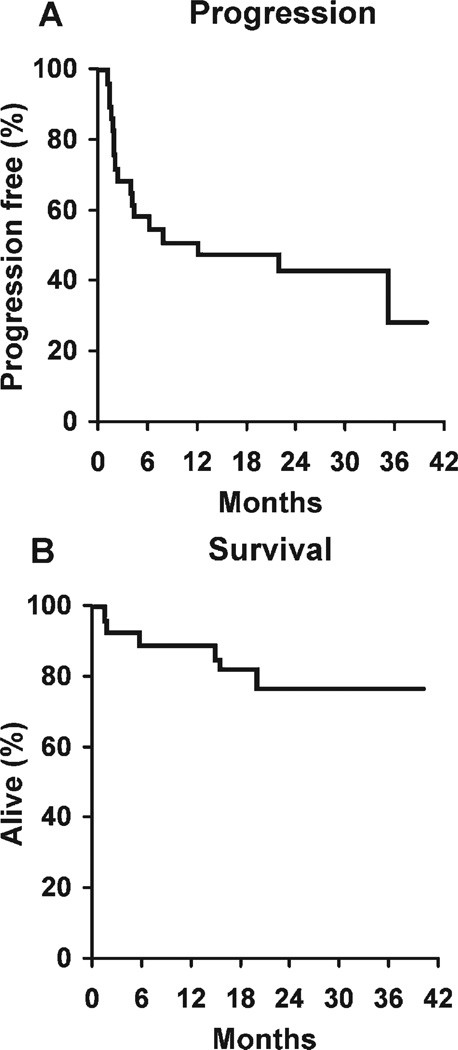

An expert pathology review prospectively identified 2 cases of mantle zone variant, 2 cases of blastoid variant, and 25 cases of diffuse variant MCL. The ORR for the combination was 66% (19 of 29). The CR rate was 52% (15 of 29 patients). In addition, 4 of 29 patients (14%) achieved a PR, 7 of 29 patients (24%) had stable disease according to the protocol after 2 cycles and were taken off study, and 3 patients (10%) progressed on therapy. Of the 7 patients who had stable disease after 2 cycles, 3 patients would have been classified as having a minor response under the design of the preceding study and would have received 2 further cycles of therapy before restaging. Of the 15 patients who achieved a CR, only 3 patients had experienced a relapse at the time of this report (368 days, 665 days, and 1036 days after starting therapy) with a median follow-up of 21.5 months in the CR patients. The median OS was not reached, and 43% of patients were progression free at 2 years (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Progression-free and overall survival of patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma who received rituximab plus cladribine.

Patients received a median of 4 cycles of therapy; 21 of 29 patients (72%) completed treatment according to the protocol design, 3 of 29 patients (10%) progressed on therapy, 2 of 29 patients (7%) went off study for an adverse event, 1 of 29 patients (3%) went off study for alternative therapy for unclear reasons, 1 of 29 patients (3%) went off study because of patient/physician choice, and 1 patient died on therapy from a cerebrovascular accident. Patients were followed until death or for a median of 24.9 months (range, 6.2–39.7 months) for patients who remained alive. Disease progression was observed in 17 of 29 patients (52%). The PFS rate was 51% at 1 year (95% CI, 36%–73%) and 43% at 2 years (95% CI, 28%–67%) (Fig. 2). At last contact, 23 of 29 patients (79%) remained alive. The 2-year OS rate was 78% (95% CI, 63%–95%).

Hematologic toxicities are listed in Table 3. Three grade ≥4 nonhematologic adverse events were reported. One patient experienced grade 3 pneumonia and sustained a subsequent cerebrovascular accident, resulting in death (grade 5). A second patient had grade 4 hyperuricemia and grade 4 dyspnea that were deemed unrelated to treatment at the point of rapid disease progression.

DISCUSSION

The treatment of MCL remains challenging. Commonly used regimens include R-CHOP8,9,15 and R–hyper-CVAD.6,7 Both produce high ORRs (>90%) but do not appear to be curative. Early ASCT may improve outcomes. Lenz et al8 randomized patients with untreated MCL to CHOP versus R-CHOP and reported median times to treatment failure of 14 months versus 21 months, respectively. Patients in CR or PR aged <65 years were randomized to stem cell transplantation versus interferon maintenance. Only 14 patients who received R-CHOP underwent ASCT. The authors reported that 4 of 14 patients developed disease recurrence. It will require further follow-up to determine whether this selected group experiences long-term PFS.

For young, healthy patients, R–hyper-CVAD with or without ASCT produces high response rates.6,7 Unfortunately, there appears to be a pattern of late relapses with this approach. This regimen is not recommended for patients aged >65 years because of excessive toxicity.

Many patients with MCL are elderly or have comorbidities that make intensive therapies such as R-CHOP/ASCT or R–hyper-CVAD difficult. Some patients who would be eligible prefer to take a less aggressive approach. We have demonstrated in this study that 2-CDA and 2-CDA plus rituximab are well tolerated regimens that produce high response rates. These results were obtained despite elderly study populations (median ages, 68 years and 70 years; age range, 39–86 years). The age distribution reflects access to the trial for older patients in the community through the NCCTG as well as a bias toward more aggressive therapy in younger patients. These sequential trials do not allow any conclusions to be drawn regarding the impact of the addition of rituximab to 2-CDA on response rates. A small change in study design may have resulted in a lower ORR (66% vs 81%) in the combination therapy study, because patients were required to achieve at least a PR after 2 cycles of therapy to continue on study, whereas patients who had evidence of a minor response after 2 cycles received 4 cycles before reassessment in the previous study. The CR rate in the combined trial (52%) did not reach the 65% target but was slightly higher than the 42% CR rate in the single-agent trial. The most striking difference between single-agent 2-CDA and combined rituximab plus 2-CDA was the apparent improved duration of response for patients who received the combination, although a prospective randomized trial would be required to confirm this finding. This is reflected in the superior 2-year PFS rate at 43% versus 21% for 2-CDA alone as well as in the durability of CRs, because only 3 of 15 patients had developed disease recurrence at a median follow-up of 21.5 months. Another possible contributor to greater response durability would be the administration of more 2-CDA to patients in CR after 2 cycles of therapy in the second trial, because 4 patients who achieved a CR after only 2 cycles of therapy received 2 additional cycles, whereas they would have stopped therapy under the design of the previous trial. The initial trial was written with conservative 2-CDA exposure because of concerns regarding cytopenias as well as the hope that brief duration therapy would be sufficient, which is the case in hairy cell leukemia. The main toxicity of 2-CDA is myelosuppression, specifically, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. Others have noted myelosuppression using 2-CDA in combination with alkylating agents.16 Cladribine, either alone or in combination with rituximab, was not associated with a significant rate of opportunistic infections in these studies, in which there was a single incidence of disseminated Nocardia in a heavily pretreated patient. Antiviral and antifungal prophylaxis was neither required nor suggested.

These trials did not provide rituximab maintenance. A recent study of combined rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (RFCM) induction followed by rituximab maintenance with 4 doses of rituximab at 3 months and 9 months postinduction demonstrated an improved TTP compared with no maintenance, although there was no convincing plateau on the TTP curve.17 A recent trial of modified R–hyper-CVAD (no methotrexate or cytosine arabinoside) in 22 patients was followed with 2 years of rituximab maintenance, and the median PFS was 37 months.18

There have been other reports of 2-CDA activity in MCL. Single-agent 2-CDA produced a 58% ORR in 12 patients with MCL.19 This was followed by a second trial that combined 2-CDA with mitoxantrone in 18 patients and demonstrated a 100% ORR with a 44% CR rate.20 Rituximab had a 33% ORR in patients with recurrent MCL.21 The single-agent activity of rituximab and 2-CDA led Robak et al22 to treat 9 patients with the combination of rituximab plus 2-CDA, and 6 of those patients (66%) responded with 2 CRs (22%). A recent case of a CR in colonic MCL obtained with combined rituximab plus 2-CDA was reported.23

Fludarabine is another purine nucleoside analogue that has been tested in MCL, usually in combination with other agents.24 Single-agent fludarabine yields a moderate ORR of 33% to 41%.25,26 Fludarabine in combination with cyclophosphamide resulted in a 100% ORR with a 70% CR rate.27 The main toxicity of the regimen was myelosuppression and infection. In recurrent MCL, the addition of rituximab to fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (FCM) improved the ORR to 58% compared with 46% for FCM alone.28 Fludarabine has been used in conditioning regimens for patients with MCL who are undergoing reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation.29–31

One concern about using purine nucleoside analogs is potential difficulty in harvesting stem cells if a subsequent transplantation is anticipated.32,33 Several new agents have demonstrated activity in recurrent MCL. The radioimmunotherapy agents tositumomab (Bexxar) and ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) have demonstrated single-agent activity that ranges from 30% to 35%.34,35 Gopal et al36,37 have studied high-dose tositumomab in the transplantation setting for recurrent MCL. Temsirolimus is a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor that produced a 38% ORR in patients with relapsed MCL.38 It was reported recently that bortezomib produced a 33% to 46% response rate in recurrent MCL.39,40 The immunomodulatory agents thalidomide and lenalidomide also are being tested in MCL.41–43

Rituximab plus 2-CDA should be included as a standard induction regimen for older adults with MCL. Further trials are indicated to determine whether the results can be improved by the inclusion of additional agents.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as a collaborative trial of the North Central Cancer Treatment Group and Mayo Clinic and was supported in part by Public Health Service grants CA-25224, CA-37404, CA-15083, CA-63848, CA-35195, CA-35090, CA-35101, CA-35269, CA-37417, CA-63849, CA-35272, CA-35113, CA-60276, CA-35103, CA-35415, and CA-35431 from the National Cancer Institute, Department of Heath and Human Services.

Support and study drug supplies were provided by Ortho Biotech and Genentech.

Footnotes

Additional participating institutions include: Sioux-land Hematology-Oncology Associates, Sioux City, Iowa (Donald B. Wender, MD); Wichita Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP), Wichita, Kan (Shaker R. Dakhil, MD); Duluth CCOP, Duluth, Minn (Daniel A. Nikcevich, MD); Michigan Cancer Research Consortium, Ann Arbor, Mich (Philip J. Stella, MD); Medcenter 1 Health Systems, Bismarck, ND (Edward Wos, MD); Carle Cancer Center CCOP, Urbana, Ill (Kendrith M. Rowland, Jr., MD); Missouri Valley Cancer Consortium, Omaha, Neb (Gamini S. Soori, MD); Meritcare Hospital CCOP, Fargo, ND (Preston D. Steen, MD); Altru Health Systems, Grand Forks, ND (Tudor Dentchev, MD); Ochsner CCOP, New Orleans, La (Carl G. Kardinal, MD); Saskatchewan Cancer Foundation (Muhammad Salim, MD); Sioux Community Cancer Consortium, Sioux Falls, SD (Loren K. Tschetter, MD); Rapid City Regional Oncology Program, Rapid City, SD (Richard C. Tenglin, MD); and Hematology and Oncology of Dayton, Inc., Dayton, Ohio (Howard M. Gross, MD).

References

- 1.Zelenetz AD. Mantle cell lymphoma: an update on management. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(suppl 4):iv12–iv14. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witzig TE. Current treatment approaches for mantle-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6409–6414. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.55.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertoni F, Zucca E, Cotter FE. Molecular basis of mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2004;124:130–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurtin PJ. Mantle cell lymphoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 1998;5:376–398. doi: 10.1097/00125480-199811000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurtin PJ, Hobday KS, Ziesmer S, Caron BL. Demonstration of distinct antigenic profiles of small B-cell lymphomas by paraffin section immunohistochemistry. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;112:319–329. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/112.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romaguera JE, Fayad L, Rodriguez MA, et al. High rate of durable remissions after treatment of newly diagnosed aggressive mantle-cell lymphoma with rituximab plus hyper-CVAD alternating with rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7013–7023. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritchie DS, Seymour JF, Grigg AP, et al. The hyper-CVAD-rituximab chemotherapy programme followed by high-dose busulfan, melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation produces excellent event-free survival in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:101–105. doi: 10.1007/s00277-006-0193-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lenz G, Dreyling M, Hoster E, et al. Immunochemotherapy with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone significantly improves response and time to treatment failure, but not long-term outcome in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1984–1992. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howard OM, Gribben JG, Neuberg DS, et al. Rituximab and CHOP induction therapy for newly diagnosed mantle-cell lymphoma: molecular complete responses are not predictive of progression-free survival. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1288–1294. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dreyling M, Lenz G, Hoster E, et al. Early consolidation by myeloablative radiochemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in first remission significantly prolongs progression-free survival in mantle-cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the European MCL Network. Blood. 2005;105:2677–2684. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saven A, Emanuele S, Kosty M, Koziol J, Ellison D, Piro L. 2-Chlorodeoxyadenosine activity in patients with untreated, indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood. 1995;86:1710–1716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheson B, Horning S, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244–1253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duffy D, Santner T. Confidence intervals for a binomial parameter based on multistage tests. Biometrics. 1987;43:81–93. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation for incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiddemann W, Dreyling M, Unterhalt M, et al. Effect of the addition of rituximab to front line therapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP) on the remission rate and time to treatment failure (TTF) compared to CHOP alone in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL): results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG) [abstract] J Clin Oncol. (Meeting Abstracts) 2004;22(14S) Abstract 6501. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Den Neste E, Michaux L, Layios N, et al. High incidence of complications after 2-chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine combined with cyclophosphamide in patients with advanced lymphoproliferative malignancies. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:356–363. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0858-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forstpointner R, Unterhalt M, Dreyling M, et al. Maintenance therapy with rituximab leads to a significant prolongation of response duration after salvage therapy with a combination of rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (R-FCM) in patients with recurring and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG) Blood. 2006;108:4003–4008. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahl BS, Longo WL, Eickhoff JC, et al. Maintenance rituximab following induction chemoimmunotherapy may prolong progression-free survival in mantle cell lymphoma: a pilot study from the Wisconsin Oncology Network. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1418–1423. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rummel MJ, Chow KU, Jager E, et al. Intermittent 2-hour-infusion of cladribine as first-line therapy or in first relapse of progressive advanced low-grade and mantle cell lymphomas. Leuk Lymphoma. 1999;35:129–138. doi: 10.3109/10428199909145712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rummel MJ, Chow KU, Karakas T, et al. Reduced-dose cladribine (2-CdA) plus mitoxantrone is effective in the treatment of mantle-cell and low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:1739–1746. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coiffier B, Haioun C, Ketterer N, et al. Rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) for the treatment of patients with relapsing or refractory aggressive lymphoma: a multicenter phase II study. Blood. 1998;92:1927–1932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robak T, Smolewski P, Cebula B, Szmigielska-Kaplon A, Chojnowski K, Blonski JZ. Rituximab combined with cladribine or with cladribine and cyclophosphamide in heavily pretreated patients with indolent lymphoproliferative disorders and mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer. 2006;107:1542–1550. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe T, Homma N, Ogata N, et al. Complete response in a patient with colonic mantle cell lymphoma with multiple lymphomatous polyposis treated with combination chemotherapy using anti-CD20 antibody and cladribine. Gut. 2007;56:449–450. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.114207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson SA. Use of fludarabine in the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma, Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia and other uncommon B- and T-cell lymphoid malignancies. Hematol J. 2004;5(suppl 1):S50–S61. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Decaudin D, Bosq J, Tertian G, et al. Phase II trial of fludarabine monophosphate in patients with mantle-cell lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:579–583. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foran JM, Rohatiner AZ, Coiffier B, et al. A. Multicenter phase II study of fludarabine phosphate for patients with newly diagnosed lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma, Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia, and mantle-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:546–553. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.2.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen BJ, Moskowitz C, Straus D, Noy A, Hedrick E, Zelenetz A. Cyclophosphamide/fludarabine (CF) is active in the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001;42:1015–1022. doi: 10.3109/10428190109097721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forstpointner R, Dreyling M, Repp R, et al. The addition of rituximab to a combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone (FCM) significantly increases the response rate and prolongs survival as compared with FCM alone in patients with relapsed and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2004;104:3064–3071. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maris MB, Sandmaier BM, Storer BE, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after fludarabine and 2 Gy total body irradiation for relapsed and refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2004;104:3535–3542. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khouri IF, Lee MS, Saliba RM, et al. Nonablative allogeneic stem-cell transplantation for advanced/recurrent mantle-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4407–4412. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hertzberg M, Grigg A, Gottlieb D, et al. Reduced-intensity allogeneic haemopoietic stem cell transplantation induces durable responses in patients with chronic B-lymphoproliferative disorders. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:923–928. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Micallef IN, Apostolidis J, Rohatiner AZ, et al. Factors which predict unsuccessful mobilisation of peripheral blood progenitor cells following G-CSF alone in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Hematol J. 2000;1:367–373. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nickenig C, Dreyling M, Hoster E, et al. Initial chemotherapy with mitoxantrone, chlorambucil, prednisone impairs the collection of stem cells in patients with indolent lymphomas—results of a randomized comparison by the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:136–142. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oki Y, Pro B, Delpassand E, et al. A Phase II study of yttrium 90 (90Y) ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin®) for treatment of patients with relapsed and refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) [abstract] Blood. 2004;104 Abstract 2632. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witzig TE, White CA, Wiseman GA, et al. Phase I/II trial of IDEC-Y2B8 radioimmunotherapy for treatment of relapsed or refractory CD20(+) B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3793–3803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.12.3793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gopal AK, Rajendran JG, Petersdorf SH, et al. High-dose chemo-radioimmunotherapy with autologous stem cell support for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2002;99:3158–3162. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gopal AK, Rajendran JG, Gooley TA, et al. High-dose [131I]tositumomab (anti-CD20) radioimmunotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for adults ≥60 years old with relapsed or refractory B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1396–1402. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Witzig TE, Geyer SM, Ghobrial I, et al. Phase II trial of single-agent temsirolimus (CCI-779) for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5347–5356. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.13.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher RI, Bernstein SH, Kahl BS, et al. Multicenter phase II study of bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4867–4874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belch A, Kouroukis CT, Crump M, et al. A phase II study of bortezomib in mantle cell lymphoma: the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group trial IND 150. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:116–121. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaufmann H, Raderer M, Wohrer S, et al. Anti-tumor activity of rituximab plus thalidomide in patients with relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2004;104:2269–2271. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drach J, Seidl S, Kaufmann H. Treatment of mantle cell lymphoma: targeting the microenvironment [review] Exp Rev Anticancer Ther. 2005;5:477–485. doi: 10.1586/14737140.5.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiernik PH, Lossos I, Tuscano JM, et al. Preliminary results from a phase II study of lenalidomide monotherapy in relapsed/refractory aggressive non-Hodgkins lymphoma [abstract] Blood. 2006;108 Abstract 531. [Google Scholar]