Abstract

The present study examined adoption-related family conversation as a mediator of the association between adoptive parents’ facilitation of contact with birth relatives and adolescent adoptive identity formation. The sample consisted of 184 adoptive families. Data were collected in two waves from adoptive mothers and fathers, and adoptees (M = 15.68 years at adolescence; M = 24.95 years at emerging adulthood) using semistructured interviews and questionnaires. Structural equation models showed a good fit to sample data, and analyses supported the hypothesized mediation model. Contact with birth relatives is associated with more frequent adoption-related family conversation, which in turn is associated with the development of adoptive identity. These results highlight the importance of supporting activities such as contact that lead to adoption-related family conversation.

Keywords: adolescence, adoption, contact, emerging adulthood, identity

Adolescence is a time when young people explore their goals, values, and beliefs in order to develop a coherent sense of identity. Identity development builds on processes originating in childhood, becomes intensified during adolescence, and lays the foundation for adult psychosocial development (Erikson, 1950, 1968). The identity development process involves active choices, such as the selection of a career path or political philosophy, and making meaning about “givens” in one’s life, such as gender, race, or being an adopted person (Grotevant, 1992). This paper focuses on adoptive identity, which addresses the following questions: “Who am I as an adopted person?” and “What does being adopted mean to me, and how does this fit into my understanding of my self, relationships, family, and culture?” (Grotevant & Von Korff, 2011).

In the mid-twentieth century, most American adoptions were closed; there was no contact between a child’s families of birth and adoption, and practice wisdom held that the best interests of the child were served when an adopted child made a clean break with the family of origin (Herman, 2008). Adoption workers matched children to their prospective adoptive parents in physical appearance so that they could “pass” as a biological family member. Attitudes changed dramatically starting in the 1970s, and it is now considered important that adopted children know about their families of birth and, if feasible, have some form of contact with birth relatives (Reitz & Watson, 1992).

Thus, in facing the challenge of developing a sense of self as an adopted person, young people today must decide what it means to be connected to both an adoptive and birth family and integrate their adoption experience into a coherent adoptive identity narrative. This process does not occur in a vacuum; it occurs in daily social interactions with important others, especially family members. This paper examines the hypothesis that frequency of family conversation about adoption mediates the connection between the adolescent’s contact with birth relatives and their development of adoptive identity.

Adoptive Identity

Our approach to adoptive identity is grounded in Neo-Eriksonian and narrative theories. Neo-Eriksonian approaches to identity have focused on the processes of identity exploration, or examination of alternative views of the self, and commitment to an understanding of who one is and how one fits into society (Marcia, 1980; Kroger & Marcia, 2011). Narrative psychology focuses on the process of meaning-making; how that process results in a narrative, or story, about oneself; how that narrative is socially constructed in relational contexts; and the role that the narrative can play in the individual’s adjustment (e.g., McAdams, 2001; McLean & Pasupathi, 2010; Pasupathi, 2001; Polkinghorne, 1988). Identity formation involves the construction of coherent stories in order to create and communicate a sense of meaning and identity and link one’s past, present, and future (McAdams, 2001). Consistent with Neo-Eriksonian approaches, we examine one domain of identity, adoptive identity. This differs from narrative approaches, which usually examine global identity rather than separate domains or components of identity (Goossens, 2001).

Adoptive identity is not directly observable, but is manifested in the adoption narratives or stories that individuals construct, write, and/or tell about themselves. In the present study, we use three dimensions drawn from developmental and narrative theories that underlie individual differences in adoptive identity, both during adolescence and emerging adulthood. The first dimension, depth of adoptive identity exploration, refers to the participant’s ability to reflect on the meaning of adoption or actively engage in a process of gathering information or decision-making about what adoption means in his or her life (Dunbar & Grotevant, 2004; Grotevant & Cooper, 1981). Depth of identity exploration is a well-established construct in Neo-Eriksonian identity research. The second, internal consistency of the narrative, considers the narrative as a self-theory and reflects how well the various components of the theory fit together. Narratives showing greater internal consistency are seen when there are statements that support the self-theory and statements that synthesize and pull the aspects of the theory together. Narratives showing lower internal consistency may not demonstrate a coherent theory or may include contradictions that are unexplained or unrecognized (Fiese et al., 1999). Coherent adoptive identity narratives are likely to make it easier for adolescents to negotiate changing family communication patterns and new adoption-related experiences as they enter emerging adulthood (Thoburn, 2004; Wrobel, Kohler, Grotevant, & McRoy, 2003). The third dimension, flexibility of the narrative, is reflected in the person’s ability to view issues as others might see them. Inflexible narratives adhere rigidly to a story line and consider relationships only from the participant’s vantage point (Fiese et al., 1999).

The transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood also involves increased opportunities to interact with new people in diverse environments outside of the immediate family sphere. In Western societies in particular, young people are expected to develop skills required for telling coherent life stories (Habermas & Bluck, 2000). Social interactions (e.g. college admission applications, job interviews, and interactions with new work colleagues, roommates, friends, and romantic partners) involve new experiences and often require life story conversation. Similarly, narratives about adoptive identity may be evoked when questions about adoption arise from new social partners or in new social situations.

Birth Family Contact and Adoptive Identity Development

Recent changes in adoption practice encouraging contact between adoptive and birth family members have highlighted adoptive identity issues for adoptees (Freundlich, 2001; Melina & Roszia, 1993). Adoptive families engage in a range of contact with their children’s birth relatives. Some engage in direct contact with one or more birth relatives, exchanging photos, letters, emails, telephone calls, and/or face-to-face visits. Others limit contact to an occasional photo or letter exchange. Some adoptive families avoid contact because they believe that it is confusing for children and harmful to identity development (Kraft et al., 1985). Yet others suggest that the quality of conversation about adoption within the adoptive family may be more important to adoptive identity formation than contact with birth relatives (Brodzinsky, 2005).

Many adoption practitioners encourage contact and many adoptive parents choose contact because they believe it facilitates children’s understanding of adoption and, ultimately, fosters adoptive identity formation (e.g., Melina & Roszia, 1993). In a recent qualitative study, adoptive mothers reported that contact with their children’s birth mothers created opportunities for them to discuss adoption-related issues with their children (Von Korff, Grotevant, Koh, & Samek, 2010). The study provided evidence that adoptive mothers deliberately use contact with birth relatives and adoption-related conversation to facilitate adoptive identity formation. Most adoptees report that contact has a positive effect on their self-concept, self-esteem, and their relationships with others (Howe & Feast, 2001; Müller & Perry, 2001), further highlighting the need to examine family processes, such as contact, involved in adoptive identity formation.

Effects of Contact Are Mediated by Family Communication Processes

But what is it about contact that makes the difference? Is it the contact itself that stimulates identity development, or is the effect of contact mediated by processes occurring within the adoptive family? This question arises from research showing that daily social interactions provide powerful social contexts for narrative exchange and identity formation (Kerpelman, Pittman, & Lamke, 1997; Ochs, Taylor, Rudolph, & Smith, 1992; Pasupathi, 2001). Social interactions involve conversation, which shapes recollections and identity as people rehearse, recall, and construct information consistent with meaning and neglect or forget information that is inconsistent (Pasupathi, 2001; Riessman, 1993). Young people use conversation to reconstruct past events in order to develop a coherent sense of identity (Polkinghorne, 1988).

Previous research (Neil, 2009; Wrobel et al., 2003) has suggested that contact with birth relatives, particularly face-to-face contact, creates opportunities for adoptive family members to talk about adoption. The presence of more frequent conversations about adoption between adoptive parents and their children is likely to be particularly important during adolescence, a key developmental period for constructing adoptive identity narratives. We propose that adoption-related conversation with adoptive parents—prompted by contact with birth relatives—should enable young people to better construct coherent adoptive identity narratives.

In summary, this is the first study to examine the dual role that contact with birth relatives and conversation within the adoptive family play in the process of adoptive identity formation. Specifically, we hypothesize that frequency of adoption-related conversation within the adoptive family mediates the proposed association between contact with birth relatives and adoptive identity formation during adolescence, and that the effects of contact and adoption-related conversation on adoptive identity formation extend into emerging adulthood.

Method

Participants

Participants included a target child, mother, and father in 184 adoptive families participating in Wave 2 (W2: adolescence) and Wave 3 (W3: emerging adulthood) of the Minnesota-Texas Adoption Research Project, a longitudinal study on contact in adoption, (Grotevant & McRoy, 1998; Grotevant, Perry, & McRoy, 2005). Adoptive families were recruited through 35 adoption agencies located in all regions of the United States. Adoption agencies received training on how to randomly sample target adopted children in families with varying levels of contact between adoptive and birth family members. Target children met the following criteria: (a) adoptees were between 4 and 12 years old at Wave 1, (b) the adoption took place before the child’s first birthday, (c) the adoptive parents remained married postadoption, and (d) the adoption had not been international, transracial, or “special needs.” The children were placed for adoption in early infancy, at a mean age of 4 weeks and a median age of 2 weeks.

There were 96 male and 88 female adoptees who were 4 to 12 years of age at Wave 1 (M = 7.8 years), 11 to 20 years of age at W2 (M = 15.68 years), and 21 to 30 years of age at W3 (M = 24.95 years). Data from Waves 2 (adolescents and parents) and 3 (young adults) were used in this report. W2 data were collected between 1995 and 2000; W3 data were collected between 2006 and 2007. At W2, adoptive fathers ranged in age from 40 to 60 years (M = 49.3 years); adoptive mothers ranged from 40 to 57 years (M = 47.4 years). The average level of education was 16.3 years for adoptive fathers and 15.1 years for adoptive mothers.

Procedures and Measures

At W2, family members were visited in their homes across the United States. During the home visit (which lasted 3 to 5 hours), participants completed consent forms, a set of questionnaires, an individual interview, and a family interaction task. The adolescent interview (see below) lasted approximately one hour, and the parent interview lasted one to two hours. Interviews were conducted by project investigators and graduate students who had received extensive training, including feedback on practice interviews. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed, and the transcripts were checked for accuracy.

At W3, a secure online data collection system was designed for the adoptees. Each participant was assigned a unique username and password allowing access to a secure online menu as a gateway to the consent forms, interviews, and questionnaires. Interviewers “met” participants online for two or three confidential secure interviews (chats) lasting one to three hours each. Participants were compensated $75 for completing interviews and $75 for completing questionnaires. The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board approved consent and online data collection procedures. Adoptees who could not arrange internet access, or who were uncomfortable with the electronic format, completed an identical telephone interview (n = 30). Some of these participants submitted identical paper questionnaires by mail (n = 18).

Demographic questionnaires

The W2 Adoptive Parent Demographic Questionnaire included questions about age, education, occupation, income, ethnicity, religion, and family composition. The W2 Adolescent and W3 Emerging Adult Demographic Questionnaires included questions about living arrangements, relationships, and work and school history.

Adolescent and emerging adult interviews

The W2 (adolescent) interview included questions about occupation, religion, friendships, and adoption. The W3 (emerging adult) interview included questions about school and occupation, religion, close relationships, and adoption. Only the adoption questions were used in the analyses reported in this paper. Interview questions at Waves 2 and 3 were very similar, but W3 questions were revised to reflect the experiences of emerging adults as compared to adolescents.

The adoption interviews were semistructured; in other words, specific questions were asked, but follow-ups and probes were used when responses were brief or unclear. The interview covered the respondent’s account of his or her own adoption story; information about how and when they were told about adoption; communication about adoption within and outside the family; contact with birth relatives, including history of contact, feelings about it, and desires for the future; relationships between birth and adoptive family members; sibling involvement; and questions they would like answered. Sample interview questions include, “Tell me your adoption story,” “Why were you placed for adoption?,” “Why did your parents choose adoption?,” “How were you told about your adoption?,” “Tell me about contact you have had with your birth family,” and “What insights about families has being an adopted person given you?” Interviewers received extensive training prior to data collection (including critiques of practice interviews) and supervision and feedback during data collection. Interviewer training manuals, interview protocols, and coding manuals are available upon request.

Adoptive parent interview

The W2 semistructured adoptive parent interview tapped their experiences with being an adoptive family in society, the relationship with the target child, the family’s knowledge of and experiences with specific birth family members, views about various contact arrangements, and hopes for the future regarding their relationships with birth family members. Adoptive parent interviewers also received extensive training prior to data collection and supervision and feedback during data collection.

Coding and Variables

Adoptive identity was coded at adolescence and again at emerging adulthood using adoptees’ W2 (adolescent) interview transcripts and W3 (emerging adult) interview transcripts. Adoptive parents’ facilitation of contact and adoption-related conversation in the family were coded from the adoptive mothers’ and adoptive fathers’ W2 interview transcripts.

General coding procedures

Adoptive identity coders were advanced graduate students with backgrounds in identity, adoption, and family process. Coders received training using the Adoptive Identity Coding Manual (Von Korff, Grotevant, & Friese, 2007). Coders were required to reach at least 80% agreement on a set of criterion transcripts before coding independently. Interrater reliability was monitored throughout the coding process. Weighted kappas were used to assess reliability because they fully correct for chance agreement while also adjusting for the degree of disagreement between coders (Cohen, 1968). At W2, all interviews were coded by two trained raters working independently (κw = .46 to .60, “moderate,” according to standards by Landis and Koch, 1977). Coding discrepancies were discussed and resolved by the coders and checked by the coding supervisor. At W3, 40% of all interviews were coded independently by two coders (κw = .68 to .78, “substantial,” according to Landis and Koch, 1977). Coding discrepancies were discussed and resolved during ongoing coding team meetings used to discuss coding issues and keep reliability strong.

W2 adoptive parent transcripts were coded by the project investigators, graduate students, or mature undergraduates, all of whom had received extensive training using the Adoptive Parent Interview Coding Manual (Minnesota Texas Adoption Research Project, 2003) and had reached at least 80% agreement on a set of criterion transcripts. Each interview was coded independently by two coders; disagreements were resolved through discussion. Ongoing coding team meetings were used to discuss coding issues and keep reliability strong.

Adoptive identity variables

This paper focuses on three variables coded from the adoption sections of the adoptees’ W2 and W3 transcripts: (a) depth of adoptive identity exploration, (b) internal consistency of the adoption narrative, and (c) flexibility of the adoption narrative. Depth of adoptive identity exploration assessed the degree to which participants reflected on the meaning of adoption or being adopted or were actively engaged in a process of gathering information or decision-making, such as, “She [birthmother] is a lot like me in an astonishing amount of ways. It’s funny because I believed that your environment had more to do with your behavior then genetics but looking at my birthmother and our similarities I really rethink that particular argument.” Depth of adoptive identity exploration was measured using a 5-point rating scale, applied globally to the entire adoption section of the interview. Anchor points included 1 (no or little depth of adoptive identity exploration), 2 (limited depth of exploration), 3 (moderate depth of exploration), 4 (mixture of moderate and high depth of exploration), and 5 (high depth of adoptive identity exploration).

Internal consistency is seen when adoption narratives include examples that support personal theories or themes. Narratives lack internal consistency when they have few or no examples, or contain unexplained or unrecognized contradictory statements. An example of a theme is, “It is important to recognize distinctions between adoptive and biological parents” and one supporting statement is, “… don’t be threatened if your child wants to find his/her biological parents. They may be naturally curious and they aren’t looking to replace you.” Internal consistency was measured using a 5-point rating scale, applied globally to the entire adoption section of the interview. Anchor points included 1 (no adoption theory can be identified), 2 (unsupported adoption theory), 3 (limited support for adoption theory), 4 (adoption theory supported; emerging internal consistency), and 5 (adoption theory well-supported, including synthesizing statements).

Flexibility assessed the degree to which participants show that they can view issues as others might see them. Participants with flexible adoption narratives consider the complex nature of issues and relationships, such as, “Just growing up, I’ve kind of tried to put it all behind me and realize that, yeah, he’s [birthfather] made his mistakes.” Inflexible participants adhere rigidly to their story line and consider relationships from one vantage point, their own: “They chose for me not to be a part of their lives, I am honoring their wishes.” Flexibility was measured using a 5-point rating scale, applied globally to the entire adoption section of the interview. Anchor points included 1 (narrative lacks perspective-taking), 2 (minimal recognition of alternative views), 3 (clearly recognizes more than one perspective), 4 (elaborates 2 or more perspectives to the issue), and 5 (integrates and resolves 2 or more perspectives).

Adoptive parents’ facilitation of contact

In their W2 interviews, adoptive mothers and fathers each reported types of contact taking place with their adolescent’s birth relatives during the preceding year. Types of contact could include letters, emails, telephone calls, photos, gifts, face-to-face meetings, extended visits, and other types of contact, such as sharing videos. A type of contact was assigned a “1” if it had occurred at least once during the past year and a “0” if not. Scores were summed for each adoptive parent. Contacts were not counted if adoptive parents reported excluding their adolescent from the contact. Adoptive mothers were also asked how frequently contacts occurred across all adoptive and birth family members. Values for this variable included 0 (none in the past year), 1 (occasionally: 1–2 times), 2 (often: 3–11 times), and 3 (frequently: 12 or more times). Adoptive parents’ facilitation of contact with birth family members (Contact with Birth Family Members) was specified as a latent variable in SEM using three W2 variables as indicators: (a) adoptive mother’s contact with birth family members, (b) adoptive father’s contact with birth family members, and (c) frequency of contact taking place among all adoptive and birth family members, reported by adoptive mothers. Higher scores indicated higher levels of contact.

Adoption-related conversation

In their W2 interviews, adoptive parents were each asked how frequently they had had adoption-related conversations with their adolescent during the past year. Adoption-related Conversation was specified as a latent variable in SEM using two variables as indicators: (a) adoptive mother’s report of the frequency of adoption-related conversation with the adopted adolescent taking place in the past year, and (b) adoptive father’s report of same. Scores for each parent ranged from “no conversation in the past year” to “12 or more conversations in the past year” (6-point scale).

Data Analysis Plan

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted using Mplus version 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2008). Prior to conducting analyses, data were screened for normality, outliers, linearity, homoscedasticity, ill-scaling, and multicollinearity. Parameters were estimated using maximum likelihood-robust (MLR), which provides standard errors and a chi-square test statistic robust to non-normality (Yuan & Bentler, 2000). Goodness of fit was evaluated using four indices. The chi square statistic should be relatively low in comparison to the degrees of freedom (Kline, 2005). The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) should be between .05 and .08 for an acceptable fit, and .05 or less for a good fit (McDonald & Ho, 2002). The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), which is sometimes referred to as the non-normed fit index (NNFI), should be .90 or greater for acceptable fit and .95 or greater for good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Residuals for indicators of adoptive identity were covaried across waves. Model tests included the adopted child’s sex (0 = male, 1 = female) and age at adolescence (W2) as controls for each model factor. The relative fit of nested structural equation models was tested using a scaled chi-square difference test (Satorra, 2000).

Missing Values Approach

Data from 184 families were available for these analyses, with complete data on all study variables for 107 families. Missing data were due to adopted adolescents (19%), adoptive fathers (16%), and adoptive mothers (9%) who did not complete interviews at W2 and emerging adults (10%) who did not complete W3 interviews. A series of t-tests revealed no significant differences between missing and nonmissing cases for key variables, including demographic variables, study outcomes, and adolescent adjustment. Mplus handles missing data by adjusting model parameter estimates using full-information maximum-likelihood estimation (FIML; Muthén & Shedden, 1999; Schafer & Graham, 2002). To obtain reliable estimates, Mplus requires that the proportion of available data for each study variable and between each pair of variables be at least .10. In the present study proportions ranged from .71 to .91 and most were above .81. Results are reported for Mplus analyses using FIML, which involves the use of all available data in parameter estimation.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations are provided in Table 1. These correlations provide preliminary evidence of significant associations among and between the indicators for the constructs. Associations were in the expected directions.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Zero-Order Correlations for Indicator Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age (AD) | |||||||||||||

| 2. Biological sex | .01 | — | |||||||||||

| Adoptive identity (AD) | |||||||||||||

| 3. Flexibility | .24 | .20 | — | ||||||||||

| 4. Depth of exploration | .26 | .19 | .55 | — | |||||||||

| 5. Internal consistency | .26 | .16 | .56 | .76 | — | ||||||||

| Adoptive identity (EA) | |||||||||||||

| 6. Flexibility | .05 | .12 | .22 | .38 | .40 | — | |||||||

| 7. Depth of exploration | −.04 | .08 | .35 | .48 | .44 | .72 | — | ||||||

| 8. Internal consistency | −.01 | .04 | .23 | .38 | .29 | .69 | .73 | — | |||||

| AP facilitation of contact | |||||||||||||

| 9. AM contact | −.04 | −.06 | .10 | .23 | .14 | .29 | .29 | .30 | — | ||||

| 10. AF contact | −.07 | −.05 | .06 | .21 | .14 | .30 | .28 | .31 | .89 | — | |||

| 11. AFAM contact | −.06 | .02 | .11 | .27 | .17 | .28 | .31 | .34 | .90 | .89 | — | ||

| Adoption-related conversation | |||||||||||||

| 12. AM conversation | −.05 | .05 | .09 | .21 | .21 | .14 | .17 | .15 | .28 | .26 | .30 | — | |

| 13. AF conversation | −.03 | .07 | .18 | .24 | .21 | .03 | .20 | .08 | .15 | .18 | .22 | .31 | — |

| M | 15.68 | .48 | 3.32 | 2.49 | 3.45 | 2.79 | 2.94 | 3.06 | 1.92 | 1.81 | 0.98 | 3.54 | 3.18 |

| SD | 1.99 | 0.50 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 1.20 | 1.27 | 1.26 | 2.37 | 2.27 | 1.18 | 1.04 | 1.18 |

Note. Correlations .15 or greater are significant at p < .05. Correlations greater than .20 are significant at p < .01.

AD = adolescence; EA = emerging adulthood; AP = adoptive parents; AM = adoptive mother; AF = adoptive father; AFAM = adoptive family.

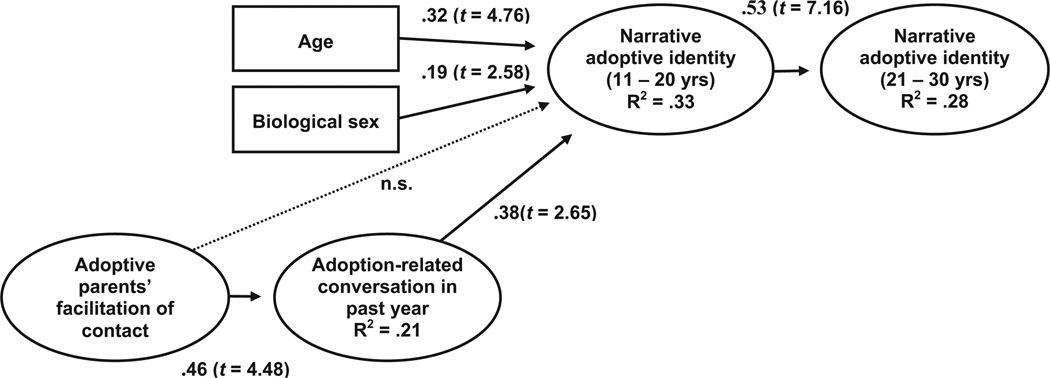

Results supported the proposed hypotheses (see Figure 1). Adoption-related Conversation mediated the association between Contact with Birth Family Members and Adolescent Adoptive Identity. Further, the effect on Adolescent Adoptive Identity extended into emerging adulthood. Mediation was tested in three steps using SEM (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Holmbeck, 1997). As expected, the first step (Model 1) showed that Contact with Birth Family Members was significantly positively associated with Adolescent Adoptive Identity (β = .26, t = 3.36). Female adolescents had higher levels of adoptive identity than males (β = .21, t = 2.66) and older adolescents had higher levels of adoptive identity than younger adolescents (β = .32, t = 4.64). Model 1 accounted for significant variance in Adolescent Adoptive Identity (R2 = .20). The model fit was good, χ2 = 17.24, df = 16, p = .37, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .021. In the second step (Model 2), Adoption-related Conversation was added to Model 1. As expected, Contact with Birth Family Members was significantly associated with Adoption-related Conversation (β = .46, t = 4.41); Adoption-related Conversation was significantly associated with Adolescent Adoptive Identity (β = .40, t = 2.59), and Contact with Birth Family Members was no longer significantly associated with Adolescent Adoptive Identity (β = .09, t = 0.81). Female adolescents had higher levels of Adoptive Identity than males (β = .19, t = 2.55), and older adolescents had higher levels of Adoptive Identity than younger (β = .33, t = 4.72). The model fit was good, χ2 = 24.70, df = 29, p = .69, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.01, RMSEA < .001. As hypothesized, the third step provided evidence that Adoption-related Conversation mediated the association between Contact with Birth Family Members and Adolescent Adoptive Identity. Mediation was tested by constraining to zero the direct path from Contact with Birth Family Members to Adolescent Adoptive Identity. The fit of the constrained model (Model 3) was good, χ2 = 25.37, df = 30, p = .71, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.01, RMSEA < .001 and the scaled chi-square difference test, comparing Model 3 to Model 2, was not statistically significant, Δχ2 = .67, Δdf = 1, p = .44, indicating that the direct path between Contact with Birth Family Members and Adolescent Adoptive Identity did not improve the model.

Figure 1.

Mediation Model of Adolescent and Emerging Adult Adoptive Identity Formation, Model 4, with standardized coefficients and t-values (see Table 2 for indicators and factor loadings).

Finally in Model 4, Emerging Adult Adoptive Identity was added to the mediation model (see Figure 1 for standardized estimates and t-values and Table 2 for indicators and factors loadings). The final model fit was good, χ2 = 62.27, df = 55, p = .23, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, RMSEA =.027. There was significant stability between Adolescent and Emerging Adulthood Adoptive Identity, and Adoption-related Conversation was indirectly associated with Emerging Adult Adoptive Identity, through its effect on Adolescent Adoptive Identity (β =.20, t = 2.50). Overall, Model 4 explained a substantial amount of the variance in Adolescent (R2 = .33) and Emerging Adult Adoptive Identity (R2 = .28). Correlations between Contact with Birth Relatives and adoptees’ sex (β = −.02, t = −.29) and age (β < −.06, t = −.79) were not significant in any model.

Table 2.

Factor Loading for Narrative Adoptive Identity Formation (Model 4, Figure 1)

| Factors and indicators | Factor loadings |

|---|---|

| Adolescent adoptive identity | |

| Depth of exploration | .88 |

| Flexibility | .63 |

| Internal consistency | .86 |

| Emerging adult adoptive identity | |

| Depth of exploration | .88 |

| Flexibility | .83 |

| Internal consistency | .83 |

| Adoptive parents’ facilitation of contact | |

| Adoptive mother | .95 |

| Adoptive father | .94 |

| Adoptive family | .95 |

| Adoption-related conversation | |

| Adoptive mother | .62 |

| Adoptive father | .51 |

Discussion

The current study tested a mediation model of adoptive identity formation with a large national sample of adoptive families. Adoptees were interviewed during adolescence and emerging adulthood, spanning an active period of identity formation when they face the challenge of making meaning of adoption in their lives (Grotevant, 1997). The frequency of adoption-related conversation within the adoptive family was found to mediate the association between contact with birth relatives and adoptive identity formation during adolescence, and the effects of contact and adoption-related conversation on adoptive identity extended into emerging adulthood.

Adoptive parents’ facilitation of contact creates opportunities for them to talk with their children about adoption. In families with same-race confidential adoptions, opportunities for adoption-related conversation may not arise unless family members intentionally create them. However, the logistics of arranging visits or exchanging letters with the child’s birth relatives require discussion. Conversations about adoption are more likely to take place within the adoptive family when social interactions, such as contact, set them in motion. Interactions with birth relatives provide one example of a day-to-day social context for adoption-related narrative exchange. We propose that such conversations help adoptees to construct, organize, and interpret the meaning of adoption in their lives.

An internally consistent and flexible identity narrative, replete with exploration, signals that something of deep concern and personal commitment is at issue. Time is being invested in reflection or action, and in turning these experiences into a coherent narrative about the self as an adopted person. Undertaking adoptive identity formation may play an important role in development over time. Our quantitative findings are illustrated by the following insightful quote from a 27-year-old participant at W3 whose adoptive parents reported both high levels of contact and adoption-related conversation.

I talk [with my adoptive parents] about how drama filled the b [birth] family is and I’m glad I’m on the outside, yet on the inside. That I can be there for everyone, but then leave, and go to my respective [adoptive] family…who isn’t perfect either. I feel it’s [adoption] given me a lot. A complete sense of perspective that not a lot of children and young adults, or adults have for that matter. It has allowed me to be completely accepting of others’ families, and be able to see issues within families that I wouldn’t have normally been aware of or really even cared about. People who have known me for a while have asked the question, nature or nurture…I’m a prime example … a product of both. I like the view point it gives me.

Broader Significance

Recent changes in adoption practice that encourage contact between adoptive and birth family members have affected adoptive and birth families— changing family interaction patterns, roles, expectations, loyalties—and highlighting adoptive identity issues for many adoptees. Most domestic placements currently offer contact as an option, particularly when birth parents have chosen to place a child voluntarily (Melosh, 2002). The nationally representative 2007 National Survey of Adoptive Parents revealed that 68% of private domestic adoptions involved postadoption contact with birth family members (Vandivere, Malm, & Radel, 2009). Contact with birth relatives plays a significant and meaningful role in a child’s immediate relational context with implications for subsequent adoptive identity formation.

Contact is also an emerging issue in international adoption (Tieman, van der Ende, & Verhulst, 2008); special needs adoption (Neil & Howe, 2004); and foster care (Neil, Beek, & Schofield, 2003). This report will be useful to adoption professionals and clinicians as they work with adoptive and birth family members, especially as they consider the range of adoption-related social interactions, such as contact, available to adopted children and their families.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has been the first to show empirically that the effects of contact on identity may be due in part to the conversations that adoptive parents have with their children about adoption. It makes an important contribution to the literatures on family psychology, identity, and adoption. The study contributed new perspectives by using structural equation modeling to reduce measurement error, include data from multiple reporters, construct a latent variable representing adoptive identity, and test direct and mediated effects over time. Strengths also include the large national sample, the longitudinal design, and the breadth and depth of data brought to bear on this question. The sample was intentionally limited to two-parent families who adopted same-race infants through private agencies. The sample delimitation strengthens the internal validity of the study by eliminating potential confounds due to transracial, international, or older-child placements; however, it limits the generalizability of the study. Participants were asked to talk specifically about adoption in a semistructured interview format. This approach differs from a life story approach to narrative in which participants are asked to select the experiences that are most important to them. However, because of our focus on adoptive identity, participants in this study were encouraged to tell their unique adoption stories and, in fact, reported a wide variety of adoption themes and content. The study is limited in that we could not examine bi-directional effects. It is possible that higher levels of adoptive identity led young people to engage in more frequent adoption-related conversation with their adoptive parents or to seek contact with their birth mothers.

Implications for Research and Practice

Contact examined in these analyses was actively facilitated by adoptive parents, and family members participated in it voluntarily. Many adoptive parents in this study, as well as the birth relatives interacting with them, were pioneers in negotiating the complexities of contact arrangements. Research has established that the nature of contact should vary according to the needs of individual children, their families, and the type of adoptive placement (e.g. domestic, international, special needs). Contact is a dynamic and transactional phenomenon (Neil & Howe, 2004), “… a complex dance in which the roles and needs of the participants change over time, affecting the kinship network as a whole” (Grotevant et al., 2005, p. 182). In some circumstances it is not possible or appropriate for adoptive parents to facilitate contact, although recent research indicates that with appropriate guidance and support, contact may be feasible in many more situations than previously assumed (Neil & Howe, 2004). Evidence suggests that contact is not in itself deleterious to the mental health of children (Grotevant & McRoy, 1998; Neil, 2009) or adolescents (Von Korff, Grotevant & McRoy, 2006). However, contact adds to the complexity of family dynamics (Grotevant, 2009). Adoptive parents set a course early in their child’s development regarding facilitation of contact with birth relatives. Adoption professionals should make evidence-based support and training available so, when feasible, adoptive and birth family members can keep the door to contact open.

Self-help books about parenting adopted children stress the importance of parent–child communication, but the empirical basis for their suggestions is thin. The findings of this study suggest that fertile ground for future research can be found in examining the role the frequency of adoption-related family conversation, as examined in this study, and the quality of adoption-related conversation play in the development of adoptees’ self-concept and adoptive identity. Grotevant and Cooper (1985) demonstrated that warm and supportive interactions between parents and adolescents, in which children are encouraged to express their views and ideas, are associated with higher levels of adolescent identity exploration across domains including occupational choice, ideology, and relationships. The extent to which conversation is helpful to an emerging sense of self (Bohanek, Marin, Fivush, & Duck, 2006) and to adoptees’ psychological adjustment depends on open communication about adoption (Brodzinsky, 2005) and conversational styles (Rueter & Koerner, 2008). Future research in this area can contribute to our understanding of the importance of parent-child relationships and family interaction patterns in children’s developmental outcomes specific to adoption. Future research should also examine the many ways adoptive parents use adoption-related social interactions, such as contact with birth relatives, to enhance adoptive identity formation.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant R01-HD-049859, National Science Foundation grant BCS-0443590, and William T. Grant Foundation grant 7146. Lynn Von Korff received a Mary Ellen McFarland Fellowship from the Department of Family Social Science for her doctoral dissertation, which constitutes the basis of this article. During the preparation of this article, Lynn Von Korff and Harold D. Grotevant were supported by funds from the Rudd Family Foundation Chair in Psychology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The authors gratefully acknowledge the adoptive family members who generously shared their experiences as part of the Minnesota-Texas Adoption Research Project.

Contributor Information

Lynn Von Korff, Department of Family Social Science, University of Minnesota.

Harold D. Grotevant, Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts Amherst

References

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohanek JG, Marin KA, Fivush R, Duck MP. Family narrative interaction and children’s sense of self. Family Process. 2006;45:39–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodzinsky D. Reconceptualizing openness in adoption: Implications for theory, research, and practice. In: Brodzinsky DM, Palacios J, editors. Psychological issues in adoption: Research and practice. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2005. pp. 145–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement with provision for scale disagreement or partial credit. Psychological Bulletin. 1968;70:213–220. doi: 10.1037/h0026256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar N, Grotevant HD. Adoption narratives: The construction of adoptive identity during adolescence. In: Pratt MW, Fiese BH, editors. Family stories and the life course: Across time and generations. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 135–162. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Childhood and society. New York: Norton; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Sameroff AJ, Grotevant HD, Wambodlt FS, Dickstein S, Fravel DL. Family story collaborative project codebook. Department of Psychology, Syracuse University; 1999. Unpublished codebook. [Google Scholar]

- Freundlich M. The impact of adoption on members of the triad: Adoption and ethics. Vol. 3. Annapolis Junction, MD: Child Welfare League of America; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Goossens L. Global versus domain-specific statuses in identity research: A comparison of two self-report measures. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24:681–699. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD. Assigned and chosen identity components: A process perspective on their integration. In: Adams GR, Montemayor R, Gulotta T, editors. Advances in adolescent development. Vol. 4. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. pp. 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD. Coming to terms with adoption: The construction of identity from adolescence into adulthood. Adoption Quarterly. 1997;1:3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD. Emotional distance regulation over the life course in adoptive kinship networks. In: Wrobel G, Neil E, editors. International advances in adoption research for practice. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2009. pp. 295–316. [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, Cooper CR. Assessing adolescent identity in the areas of occupation, religion, politics, friendship, dating, and sex roles: Manual for administration and coding of the interview. Journal Supplement Abstract Service Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology. 1981;11(52) Ms. NO. 2295. [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, Cooper CR. Patterns of interaction in family relationships and the development of identity exploration in adolescence. Child Development. 1985;56:415–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, McRoy RG. Openness in adoption: Exploring family connections. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, Perry Y, McRoy RG. Openness in adoption: Outcomes for adolescents within their adoptive kinship networks. In: Brodzinsky D, Palacios J, editors. Psychological issues in adoption: Research and practice. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2005. pp. 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, Von Korff L. Adoptive identity. In: Schwartz S, Luyckx K, Vignoles V, editors. Handbook of identity theory and research. New York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas T, Bluck S. Getting a life: The emergence of the life story in adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:748–769. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman E. Kinship by design: A history of adoption in the modern United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:599–610. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe D, Feast J. The long-term outcome of reunions between adult adopted people and their birth mothers. The British Journal of Social Work. 2001;31:351–368. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criterion for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kerpelman JL, Pittman JF, Lamke LK. Toward a microprocess perspective on adolescent identity development: An identity control theory approach. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1997;12:325–346. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft A, Palombo J, Mitchell D, Woods P, Schmidt A, Tucker N. Some theoretical considerations on confidential adoption: Part III. The adopted child. Child and Adolescent Social Work. 1985;2:139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kroger J, Marcia JE. The identity statuses: Origins, meanings, and interpretations. In: Schwartz S, Luyckx K, Vignoles V, editors. Handbook of identity theory and research. New York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Identity in adolescence. In: Adelson J, editor. Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York: Wiley; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP. The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology. 2001;5:100–122. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP, Ho MR. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods. 2002;70:64–82. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean KC, Pasupathi M, editors. Narrative development in adolescence: Creating the storied self. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Melina LR, Roszia SK. The open adoption experience. New York: Harper Perennial; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Melosh B. Strangers and kin: The American way of adoption. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Minnesota Texas Adoption Research Project. Coding manual for the Wave 2 Adoptive Parent Interview. University of Minnesota: Minnesota Texas Adoption Research Project, Department of Family Social Science; 2003. Unpublished codebook. [Google Scholar]

- Müller U, Perry B. Adopted persons’ search for and contact with their birth parents II: Adoptee-birth parent contact. Adoption Quarterly. 2001;4(3):39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén L. Mplus version 5.2. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Shedden K. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics. 1999;55:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neil E. Post adoption contact and openness in adoptive parents’ minds: Consequences for children’s development. London: British Journal of Social Work. 2009;39:5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Neil E, Beek M, Schofield G. Thinking about and managing contact in permanent placements: The differences and similarities between adoptive parents and foster carers. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;8:401–417. [Google Scholar]

- Neil E, Howe D, editors. Contact in adoption and permanent foster care: Research, theory, and practice. London: British Association for Adoption and Fostering; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ochs E, Taylor C, Rudolph D, Smith R. Storytelling as a theory-building activity. Discourse Processes. 1992;15:37–72. [Google Scholar]

- Pasupathi M. The social construction of the personal past and its implications for adult development. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:651–672. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne D. Narrative knowing and the human sciences. Albany, NY: SUNY Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Reitz M, Watson KW. Adoption and the family system. New York: Guilford; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Riessman CK. Narrative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rueter MA, Koerner AF. The effect of family communication patterns of adopted adolescent adjustment. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2008;70:715–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00516.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A. Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. In: Heimans RDH, Pollack DSG, Satorra A, editors. Innovations in multivariate statistical analysis: A festchrift for Heinz Neudecker. London: Kluwer Academic; 2000. pp. 233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoburn J. Post-placement contact between birth parents and older children: The evidence from a longitudinal study of minority ethnic children. In: Neil E, Howe D, editors. Contact in adoption and permanent foster care: Research, theory and practice. London: British Association for Adoption and Fostering; 2004. pp. 184–202. [Google Scholar]

- Tieman W, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Young adult international adoptees’ search for birth parents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:678–687. doi: 10.1037/a0013172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandivere S, Malm K, Radel L. Adoption USA: A chartbook based on the 2007 National Survey of Adoptive Parents. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff L, Grotevant HD, Friese S. Manual for coding adoptive identity. University of Minnesota: Minnesota Texas Adoption Research Project, Department of Family Social Science; 2007. Unpublished codebook. [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff L, Grotevant HD, Koh BD, Samek DR. Adoptive mothers: Identity agents on the pathway to adoptive identity formation. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2010;10:122–137. [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff L, Grotevant HD, McRoy RG. Openness arrangements and psychological adjustment in adolescent adoptees. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:531–534. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel GM, Kohler JK, Grotevant HD, McRoy RG. The Family Adoption Communication (FAC) Model: Identifying pathways of adoption-related communication. Adoption Quarterly. 2003;7(2):53–84. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan KH, Bentler PM. Three likelihood-based methods for mean and covariance structure analysis with non-normal missing data. Sociological Methodology. 2000;3:65–200. [Google Scholar]