Abstract

Although canonical Wnt signaling is known to regulate taste papilla induction and numbers, roles for noncanonical Wnt pathways in tongue and taste papilla development have not been explored. With mutant mice and whole tongue organ cultures we demonstrate that Wnt5a protein and message are within anterior tongue mesenchyme across embryo stages from the initiation of tongue formation, through papilla placode appearance and taste papilla development. The Wnt5a mutant tongue is severely shortened, with an ankyloglossia, and lingual mesenchyme is disorganized. However, fungiform papilla morphology, number and innervation are preserved, as is expression of the papilla marker, Shh. These data demonstrate that the genetic regulation for tongue size and shape can be separated from that directing lingual papilla development. Preserved number of papillae in a shortened tongue results in an increased density of fungiform papillae in the mutant tongues. In tongue organ cultures, exogenous Wnt5a profoundly suppresses papilla formation and simultaneously decreases canonical Wnt signaling as measured by the TOPGAL reporter. These findings suggest that Wnt5a antagonizes canonical Wnt signaling to dictate papilla number and spacing. In all, distinctive roles for Wnt5a in tongue size, fungiform papilla patterning and development are shown and a necessary balance between non-canonical and canonical Wnt paths in regulating tongue growth and fungiform papillae is proposed in a model, through the Ror2 receptor.

Keywords: fungiform papilla, tongue, Wnt, Shh, papilla placode, non-canonical Wnt

INTRODUCTION

The tongue, with dorsal taste and non-taste organ specializations, performs complex, integrated oral sensory and motor functions. In rodents the tongue emerges as a set of tissue swellings in the early embryo and acquires circumvallate, foliate and fungiform taste papillae and filiform non-taste papillae before birth (Mistretta, 1972; Mistretta and Hill, 1995). Taste buds form within papillae in the perinatal period and mature after birth. Taste bud development continues postnatally and the taste bud cells turn over on a cycle of about ten days in the adult (Beidler and Smallman, 1965), in a continuous replacement similar to skin or gut cells (Hsu et al., 2011; Radtke and Clevers, 2005; van der Flier and Clevers., 2009). Formation of tongue and taste organs requires coordinated waves of cell induction, proliferation and differentiation that must be orchestrated for normal development.

The fungiform papilla taste organs on the anterior tongue have a particular patterned array, bracketing a papilla-free median furrow and interspersed with spatial regularity among non-taste filiform papilla (Mbiene et al., 1997). Of several molecular pathways that control fungiform taste papilla development (Mistretta and Liu, 2006), the Wnt family is essential in papilla induction and formation (Iwatsuki et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2007; Okubo et al., 2006). However, detailed exploration of Wnt proteins in taste papilla development is limited. Specifically, there has been no investigation of the role of “noncanonical” Wnts such as Wnt5a in tongue morphogenesis.

In taste papilla development, canonical Wnt10b signaling via β-catenin and Lef1/Tcf is required for fungiform papilla formation (Iwatsuki et al., 2007; Liu et al, 2007; Okubo et al., 2006). Deletion of either Wnt10b, β-catenin or Lef1 leads to a striking loss of fungiform papillae without an obvious alteration of the circumvallate papilla (Iwatsuki et al., 2007; Liu et al, 2007). This demonstrates a specific requirement of canonical Wnt signaling for fungiform papilla development. Moreover, in postnatal day 1, Lef1−/− tongue, where fungiform papillae are “atrophied” or missing, tissue positions for fungiform papillae are maintained within a sea of filiform papillae (Iwatsuki et al., 2007).

However, in a gene screen to compare embryonic tongue regions rich in fungiform papillae (anterior tongue) or papilla-free (intermolar eminence) we found that Wnt5a, generally regarded as signaling in noncanonical paths, was expressed at levels 7-fold higher in anterior tongue compared to intermolar eminence (Liu et al., 2009). We hypothesized roles for Wnt5a in tongue and fungiform papilla development and proposed that signaling via Wnt5a might have very different regulatory roles than classical canonical signaling reported via Wnt10b (Liu et al., 2009).

Wnt5a affects cell migration and polarity (He et al., 2008; Schlessinger et al., 2007; Witze et al., 2008) and can alter elongation of outgrowing organ structures (Cervantes et al., 2009; Qian et al., 2007; Yamaguchi et al., 1999), branching patterns (Allgeier et al., 2008; Li et al., 2002; 2005) and tubulogenesis (Huang et al., 2009; Loscertales et al., 2008; Roarty and Sierra, 2007). Although generally considered to signal in a noncanonical pathway, Wnt5a can function to inhibit or activate canonical signaling through β-catenin and Tcf/Lef (Cha et al., 2008; Mikels and Nusse, 2006; Pukrop and Binder, 2008; Yamamoto et al., 2007). The ability of Wnt5a to act through various pathways is based on receptor and co-receptor availability (Grumolato et al., 2010; Mikels and Nusse, 2006) but precise mechanisms for the panoply of actions have not been determined.

We used embryo tongues and whole tongue cultures from Wnt5a null mutant and wild type mice (Yamaguchi et al., 1999) to determine roles in tongue and papilla development and differentiation. In a preliminary, extended abstract we reported a shorter tongue phenotype in Wnt5a mutants at embryonic day 16 (Liu et al., 2009). Here we demonstrate, across embryo stages, that Wnt5a mutant tongues are extremely short compared to wild type and are associated with ankyloglossia and cleft palate. Wnt5a message and protein are most intensely localized in anterior tongue mesenchyme and the Wnt5a mutant lingual mesenchyme is disorganized with altered cell proliferation and cytoskeleton characteristics compared to wild type. On the other hand, papilla development proceeds with intact fungiform morphology, numbers and innervation in the shortened Wnt5a mutant tongue. The Shh expression pattern in fungiform papillae is not perturbed although papilla density is increased. Addition of Wnt5a in tongue cultures, however, leads to reduced papilla numbers and altered epithelial integrity, and reduces canonical Wnt signaling activity seen in TOPGAL mice. These data demonstrate clear and distinctive roles for Wnt5a in the control of tongue size and shape versus the number, spatial patterning and innervation of fungiform papillae.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Animals and tissue dissection

Animal maintenance and use were in compliance with institutional animal care protocols and in accordance with National Institutes of Health Guidelines for care and use of animals in research.

Mouse

Wnt5a-null (−/−) embryos were generated by intercrosses of Wnt5a-heterozygous mice purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Yamaguchi et al., 1999). The mutated Wnt5a litters were identified by phenotype and genotyped by PCR, and wild type littermates were used for comparison. TOPGAL mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (DasGupta and Fuchs, 1999). Embryos were staged by vaginal plug detection and confirmed by Thieler staging for development of multiple organs. Noon of the day of vaginal plug detection was designated embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5).

Rat

Embryonic (E13-20) and postnatal (P3-16) rat tongues were used for Western blot assays. Timed, pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were from Charles River breeders. All dissections of E13-20 embryos were between 9:00 AM and 12:00 PM for consistency across litters (Mbiene et al., 1997). E0 was the day of vaginal plug confirmation and P1 was the day when pups were born.

Tissue collection

Animals were deeply anesthetized by isofluorane for mice or an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (60 mg/kg body weight) for rats. Embryos, anesthetized via the dam, were removed into cold, sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and tissues were dissected and processed for different analyses.

Tongue organ culture

Tongues dissected from wild type, Wnt5a−/− or TOPGAL embryos were cultured as described (Mbiene et al., 1997; Mistretta et al., 2003). Briefly, whole tongues at E12.5 were dissected from the mandible and placed on sterile Millipore HA filters on stainless steel grids in culture dishes. Cultures were fed with a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium and Ham’s nutrient F12 (DMEM/F12, GIBCO, Gaithersburg, MD), containing 1% fetal bovine serum, 50 μg/ml gentamicin sulfate, and 2% B27 culture supplement (GIBCO; control or standard medium, Std). The level of medium was adjusted so that cultures were at the gas/liquid interface, in a humidified incubator at 37°C.

For experiments with exogenous agents, Wnt5a protein (R&D Systems, 645-WN, 0.3 – 5.0 μg/ml), cyclopamine (10 μM), NaCl (5 mM) or LiCl (5, 10, 15 mM) was added to the culture medium and maintained during the entire culture period. Cultures in standard medium were used as controls. After 2 or 3 days, cultures were collected and processed for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) or Shh immunoreactions.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and tongue size and papilla quantification

Tongues or tongue cultures were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3) at 4°C, post-fixed in a sequence of aqueous 1% OSO4, 1% tannic acid, 1% OSO4, for 1 hr each on ice, and processed as described (Mbiene et al., 1997). Tissues were mounted, sputter coated with gold/palladium, and analyzed with SEM. Digital images were acquired and assembled using Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

SEM images of embryonic tongues at ×75 original magnification were used to count fungiform papillae, with 3 to 6 tongues in each experimental condition. Each papilla, defined as a round or oval protuberance that has a distinctive surface epithelium from the surrounding tissue, was marked and counted on a plastic overlay positioned over photomicrographs.

For measurement of tongue size, we used SEM images at ×70 and ×150 original magnification for oral and pharyngeal regions, illustrated in Supplemental Data Figure 1.

Western blot

Wnt5a in tongues was detected with Western blot assays (Wnt5a antibody, R&D Systems AF645,1:1000). Protein was extracted from entire tongue, or from dissected tongue tip or intermolar eminence. For separation of epithelium and mesenchyme, tongues were incubated with dispase II (2.4 unit/ml, Gibco, Germany) added to PBS for 30 min at 37°C. The epithelial sheet was peeled from mesenchyme and collected tissues were transferred to 0.2% Nonidet-P40 lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors on ice for 10 min. The epithelial and mesenchyme lysate was centrifuged and the supernatant collected. Protein content in the supernatant was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay (Hercules, CA). Equal amounts of protein were run with sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Procedures for blocking and antibody probing were as described (Liu et al., 2008). Visualization of immunoreactive proteins was with the chemiluminescence system (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and exposure to film.

In situ hybridization

Wnt5a cDNA was from Dr. Y. Yoshida (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center). Wnt6 cDNA was cloned from tongue tissue. Other Wnt cDNAs were from a gift from Dr. D. Agalliu (Columbia University). Tongue tissues from E12.5, E16.5, and E18.5 mice were frozen in O.C.T. compound, sectioned at 12 μm and post-fixed (10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by acetylation in acetic anhydride for 10 min). After three washes in PBS, sections were prehybridized in hybridization buffer (5x SSC/50% formamide/1x Denhardt’s solution/1 mg/ml salmon sperm DNA/1 mg/ml tRNA). Hybridizations were performed with digoxigenin-labeled cRNA probes in the hybridization buffer for 18 h at 72°C. Hybridization signals were detected by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antidigoxigenin antibodies plus NBT/BCIP substrate (Roche) as described (Iwatsuki et al., 2007).

Histology

E11.5-E18.5 mouse tongues on mandibles were dissected and fixed in 4% PFA in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4, at 4°C for 2 hr, then transferred to 70% ethanol. Specimens were embedded in paraffin and serially sectioned in sagittal plane at 5–8 μm for hematoxylin and eosin staining. To compare lingual tissues between WT and mutant tongues, and across embryo stages, serial sections were examined to ensure evaluation of all tongue regions. To represent tongues in figures, photomicrographs were made in the region mid-way between the lateral edge and the central, papilla-free, median furrow, effectively one quarter through the tongue. Littermate WT and mutant tongues were embedded in one block and therefore, were sectioned, mounted and stained on the same slides.

Immunohistochemistry

Antibodies

Primary antibodies and dilutions were: Shh (AF464, 1:100, R&D Systems, Minneapolis MN); Ki67 (M7248, 1:400, DakoCytomation, DK); BrdU (G3G4, 1:400, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa); βIII-tubulin (T2200, 1:1000, Sigma Aldrich, St Louis MO); E-cadherin (AF748, 1:500, R&D Systems); vimentin (#5741, 1:50, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); Ror2 (#4105, 1:50, Cell Signaling Technology). Slides treated with no primary antibody or with the same concentration of normal IgG were used as controls.

Whole tongue immunohistochemistry

To localize Shh in embryonic tongues and cultures, tongues were fixed in 4% PFA in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4, at 4°C for 2 hr, and processed as described (Liu et al., 2004). The number of immuno-loci was counted on E14.5 mouse tongues from prints of photographed images and confirmed under a stereomicroscope (six WT and four mutant).

Tissue section immunohistochemistry

To immunolocalize Ki67 and BrdU, dissected embryo heads or tongue cultures were fixed in 4% PFA in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4, at 4°C for 2 hr, then transferred to 10% sucrose in PBS at 4°C for 24 hr. Tissues were frozen in O.C.T. Serial sagittal sections were cut at 10 μm, thaw-mounted onto gelatin coated slides and reacted as described (Liu et al., 2004; Mistretta et al., 2003). For Ki67 and BrdU immunoreactions, a M.O.M kit (PK-2200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was used and recommended procedures were followed.

Ki67- and BrdU-postive cell quantification

Ki67 antigen is normally expressed in nuclei of cells in all phases of the cell cycle, except G0 (Schlozen and Gerdes, 2000). BrdU labels cells in S-phase. We used both Ki67 and BrdU antibodies to label proliferating cells. Littermate pairs of WT and Wnt5a−/− embryos at E13.5 and E16.5 were analyzed for Ki67 (n=3 pairs per time point). Pregnant female were injected intraperitoneally with 10 mg BrdU/100 gram body weight. Embryos were collected 2 hr after injection and processed for cryosectioning as described above. Tongues from each pair of stage-matched embryo siblings (Wnt5a−/− and wild type) were embedded in O.C.T. and frozen. Serial sagittal sections were cut at 10 μm and alternating sections were collected on two sets of slides for Ki67 and BrdU immunoreactions.

Analysis of labeled tongue sections was performed by counting Ki67- and BrdU-positive cells in specified regions of the epithelium and mesenchyme of the tongue tip. A set of 4 to 12 nonconsecutive sections (midway between the lateral border and median furrow of the tongue) was captured with light microscopy and subsequently printed. For each captured section, a 250 μm length of epithelium and a 222 μm diameter area of mesenchyme in the tongue tip were outlined. Each Ki67+ and BrdU+ cell in the marked region of epithelium and mesenchyme that had a clearly labeled nucleus was designated with a dot and counted in each photographed section.

Ki67 labeled proliferating cells were also quantified in E12.5 plus two day wild type mouse tongue cultures, in standard medium and with addition of Wnt5a (three cultures per group).

X-Gal Staining

E12.5 limb buds and tongue cultures from TOPGAL mice were fixed in 4% PFA on ice for 15 min, washed in PBS containing 2.0 mM MgCl2, transferred into freshly prepared X-Gal solution (1 mg/ml X-Gal in 0.1 M PBS with 2.0 mM MgCl2/0.01% sodium deoxycholate/0.2% Nonidet P-40/5 mM potassium ferricyanide/5 mM potassium ferrocyanide), and incubated at 37°C for 1–5 hours. Stained tissues were photographed as whole mounts and then cryo-sectioned for light microscopy.

Data analysis and statistics

Papilla and cell numbers are presented as mean ± standard deviation. ANOVA was used for comparison across multiple groups, with a Bonferroni post hoc test. A t-test assuming unequal variances was used for comparison between two groups. Significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Wnt5a mRNA and protein are expressed in the embryonic tongue, primarily in anterior and mesenchymal tissues

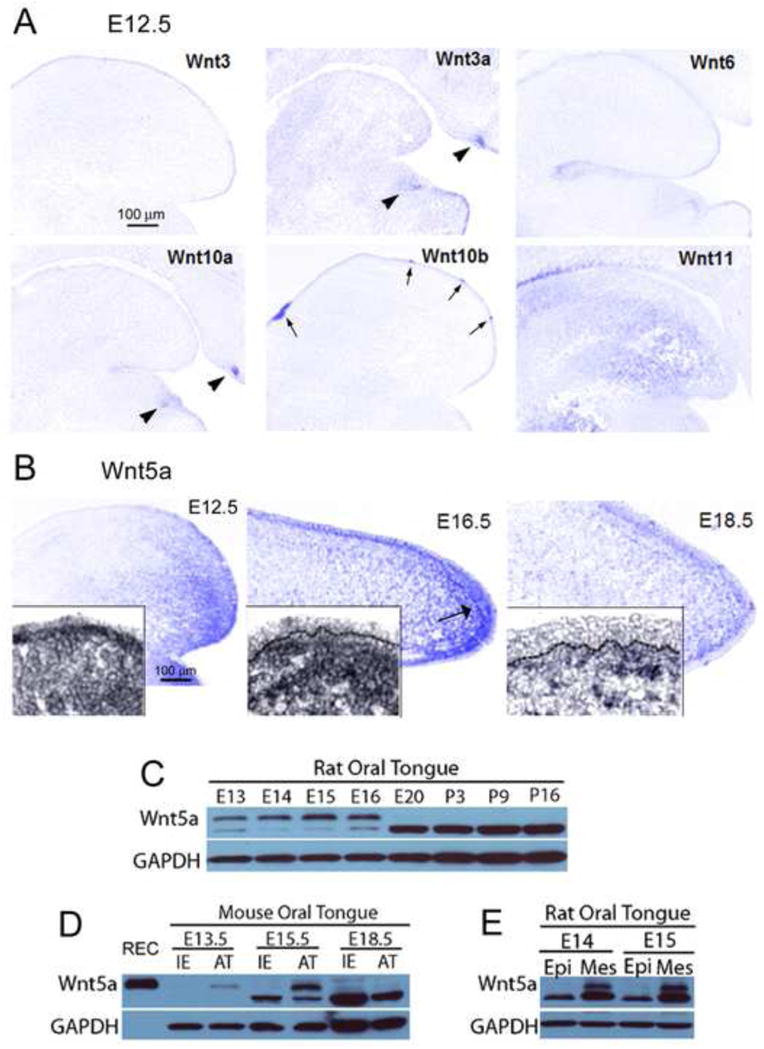

Several Wnts including Wnt3, 3a, 6, 10a, 10b and 11 were screened with in situ hybridization at E12.5 (Figure 1A). Distributions were: condensed within tooth buds only (Wnt3a, 10a, arrowheads); intense in lingual epithelium only (Wnt3, 6); in mesenchyme only (Wnt11); or, restricted to fungiform and circumvallate papillae (Wnt10b, arrows; confirms previous report, Iwatsuki et al., 2007).

Fig. 1. Wnts and Wnt5a in the developing tongue.

A: Photomicrographs of in situ hybridization for Wnt3, 3a, 6, 10a, 10b and 11 in E12.5 WT sagittal tongue sections. Patterns can be diffuse, primarily epithelial or mesenchymal, intense in tooth bud, and/or intense in taste papillae. Arrows point to fungiform and circumvallate papillae; arrowheads point to tooth buds. Scale bar in Wnt3, 100 μm, applies to all images. B: Photomicrographs of Wnt5a detected by in situ hybridization in E12.5-18.5 WT tongue sections. At E12.5 and E16.5 a gradient of Wnt5a is apparent with strong expression in the tongue tip, primarily in the mesenchymal tissue. At E18.5, Wnt5a expression is reduced and mainly in a subepithelial band of mesenchyme (see inset). Scale bar at E12.5: 100 μm, applies to all stages. C: Wnt5a protein bands detected by Western blot in rat (E13 through postnatal, P16). D: Western blots in mouse tongue (E13.5-18.5), comparing intermolar eminence (IE) and anterior tongue tongue (AT) regions against recombinant mouse protein (REC). REC protein is expressed in top band only. E: Western blots in E14-15 rat tongue comparing enzymatically separated epithelium (Epi) and mesenchymal (Mes) tissues. Overall, Wnt5a is most intense in embryonic stages, in anterior tongue mesenchyme, as illustrated with in situ hybridization.

In comparison, the distribution of Wnt5a was unique, with strongest expression in anterior tongue and weak or no expression in the posterior tongue, intermolar eminence region (Figure 1B, E12.5). Anterior tongue expression was intense in mesenchyme compared to epithelium (inset). At E16.5 Wnt5a remained in an anterior tongue location and was especially intense in a subepithelial band of mesenchyme (Figure 1B). By E18.5 Wnt5a was much reduced and primarily in a condensed, subepithelial band of mesenchyme (Figure 1B).

Western blots of embryonic rat tongue demonstrated expression of Wnt5a protein in E13 through E16 tongue, not at E20 or postnatal stages (Figure 1C, see Wnt5a top band). Because two bands were seen in Western blots for Wnt5a, in our data and in the literature (e.g., Dissanayake et al., 2007; Ghosh et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2010; Ripka et al., 2007; Winkel et al., 2008), we repeated the rat developmental series (data not shown) and further, we compared stages of embryonic mouse tongue with the recombinant protein (Figure 1D). Recombinant Wnt5a was expressed at the top band location only, which we interpreted as the correct band for Wnt5a protein. Hu et al (2010) specifically addressed multiple bands for Wnt5a in hair follicle studies and also demonstrated the top band as Wnt5a protein expression (see Figure 3B in Hu et al., 2010).

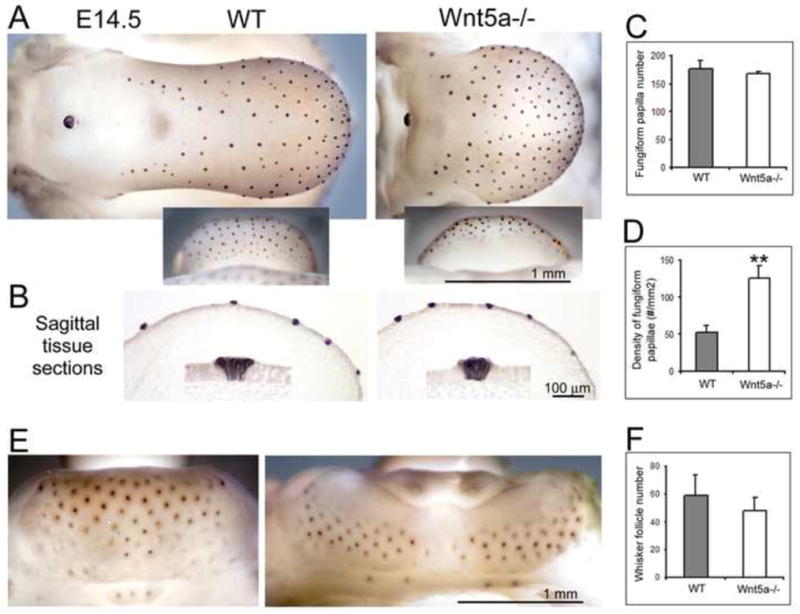

Fig. 3. Shh in taste papillae and whisker follicles in WT and Wnt5a mutants and organ number and distribution.

Shh immunoreacted E14.5 mouse tongue (A–D) and mandible (E–F) and histograms for number and density of appendages (n = 4 – 6 each group, WT and mutant). A: Shh immunoproduct is restricted to each fungiform papilla on dorsal and ventral tongue (insets) and the circumvallate papilla. In Wnt5a−/−, the distinctive spatial pattern of fungiform and circumvallate papillae is retained on the shorter tongue. B: Sagittal tissue sections demonstrate that Shh immunoproducts are indeed in the epithelium of fungiform papillae. C: Total Shh-positive papilla number is similar in mutant and WT tongues. D: However, the density of fungiform papillae is more than two fold greater in Wnt5a−/− than in WT (middle graph). E: Whisker follicles, shown on mandibular skin, are also labeled with Shh immunoproduct. F: The number of whisker follicles is similar in WT and Wnt5a−/−, although the distribution is different in mutants due to altered mandible structure. Scale bars: 1.0 mm for whole mount tissues; 100 μm for sections. **P<0.01 compared to WT group (t-test assuming unequal variances).

Wnt5a protein expression was determined in Mouse Oral Tongue (Figure 1D) dissected in anterior tongue (AT) or intermolar eminence (IE) parts. The IE is a papilla-free tongue region (Supplemental Data, Figure 1). Developmentally, Wnt5a was expressed in mouse anterior tongue at E13.5 and 15.5 but was not discernable at E18.5 (Figure 1D, AT). This late embryonic decrease in Wnt5a was comparable to the developmental loss in E20 rat tongue (Figure 1C). Wnt5a was not detected in the IE (Figure 1D).

To further probe Wnt5a localization, we used rat tongue again at E14 and E15, to yield sufficient quantities of protein after enzymatic treatment for separation of anterior tongue epithelium (Epi) and mesenchyme (Mes) (Figure 1E). The separation of tissues revealed strong expression of protein in mesenchyme only.

In sum, results indicate that Wnt5a protein expression is primarily at early to mid-embryonic stages, in anterior tongue and principally in mesenchyme; these results match the data from in situ hybridization (Figure 1B).

Wnt5a mutant tongues are shorter than wild type but have similar numbers of fungiform papillae in a denser distribution

Tongue length and width

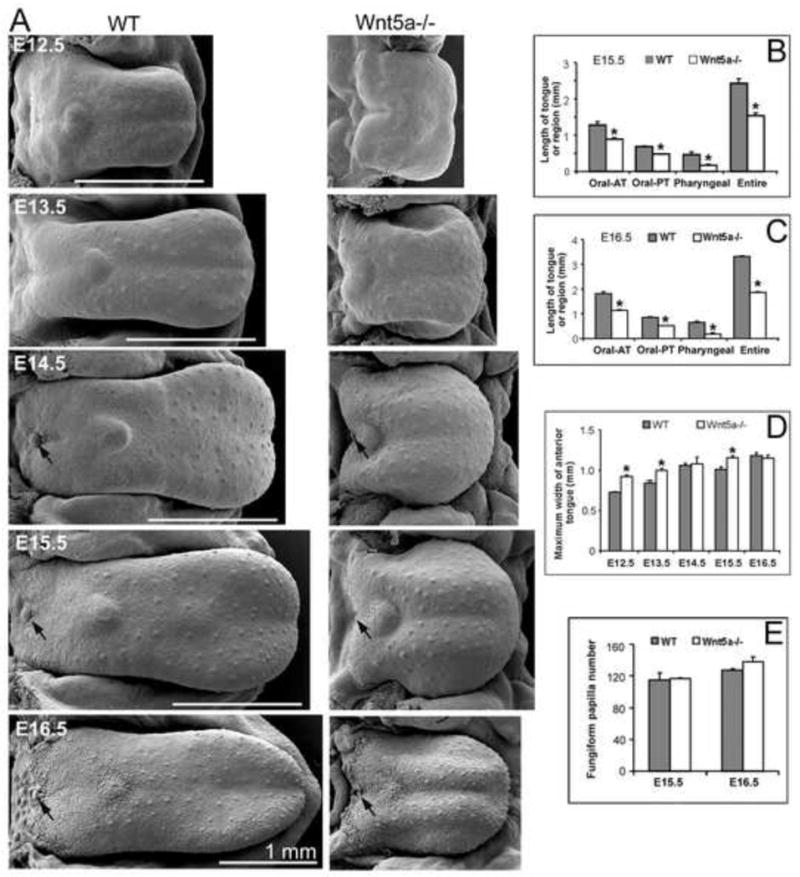

Because Wnt5a is localized to the anterior-most portion of the growing tongue, we hypothesized roles in regulating tongue outgrowth and fungiform papilla development. In scanning electron micrographs (SEMs) Wnt5a null mutant (Wnt5a−/−) embryo tongues were compared to wild type (WT) littermates, from E12.5 through E16.5 (Figure 2A). Across all stages an extremely short tongue was obvious in Wnt5a−/− mice. Measurements of length of specific tongue regions at E15.5 and 16.5, as oral anterior, oral posterior, or pharyngeal, demonstrated that all areas were shorter in mutants (Figure 2B, C). For entire oral length, mutant tongues were about 60% the length of WT. Furthermore, maximum tongue width (anterior widest point) was greater in mutant tongues from E12.5 to E15.5 (Figure 2D). The short, wide mutant tongues had obvious raised, anterior tongue regions at E14.5-16.5, seen in SEMs.

Fig. 2. Development of tongue size, shape, topography and papillae in WT and Wnt5a mutants.

Scanning electron micrographs

(A) of WT and Wnt5a−/− embryonic mouse tongue on mandible, and histograms (B–E) for measurements of tongue length, width and fungiform papilla number. (n = 2 – 6 tongues for WT and mutant, at each stage.) A: At E12.5, the WT tongue is spatulate with small surface eminences on the anterior region that are fungiform papilla placodes. The mutant tongue is noticeably shorter than WT and has not attained a spatulate shape. By E13.5, the WT and mutant tongues exhibit further growth, and fungiform papillae are distinctive in multiple rows on anterior oral tongue. The single circumvallate papilla on posterior tongue is seen as a small ovoid swelling. At E14.5, fungiform and circumvallate (black arrow) papillae protrude more on the tongue surface of WT and mutant. Mutant tongues remain much shorter than WT. At E15.5 and E16.5, the distinctive spatial pattern of fungiform and circumvallate (black arrow) papillae is retained on the longer and more differentiated tongues, although mutant tongues are shorter. B, C: Length of tongue regions was quantified at E15.5 and E16.5. For Wnt5a−/− tongues each lingual region is significantly shorter than in WT. Oral AT and Oral PT refer to anterior and posterior oral tongue. Pharyngeal refers to the pharyngeal tongue only. These regions are delineated in Supplemental Figure 1. D: The mutant tongue is wider than in WT littermates at E12.5, E13.5 and E15.5. E: Fungiform papilla number is not altered in Wnt5a−/− compared to WT at E15.5 and E16.5. * P<0.05 compared with WT group (ANOVA and Bonferoni post-hoc tests). Scale bars: 1.0 mm, apply to WT and paired mutant tongues.

Although the tongue does not acquire a spatulate shape until E12.5, we further examined Wnt5a mutant and WT tongues at E11.5 when the three lingual swellings are still apparent. The mutant lateral lingual swellings are about 50% shorter than in WT, and mutant lingual swellings are wider (Supplemental Figure 2A). Whereas effects of gene deletion on size are observed at earliest stages of tongue formation, general cell histology of the epithelium and mesenchyme is similar in mutant and WT lingual swellings (Supplemental Figure 2B).

Number and density of fungiform papillae

Although Wnt5a−/− tongues were extremely truncated, number of fungiform papillae was the same in WT and −/−, determined from counts of all papillae in SEMs at two stages, E15.5 and 16.5 (Figure 2E). The single circumvallate papilla typical of rodent tongue is seen on the posterior border of the oral tongue in WT and Wnt5a−/− at E14.5 to E16.5 (Figure 2A, arrows). Although we have not systematically studied the circumvallate, it is noticeably smaller in mutant tongues.

The number of fungiform papillae was not altered in E15.5-16.5 Wnt5a mutant tongues, suggesting that papilla density was increased compared to WT. To confirm this we determined papilla number and density in whole E14.5 tongues immunostained for Sonic hedgehog (Shh), an embryonic taste papilla marker (Mistretta et al., 2003) (Figure 3A). Papillae are easily identified and quantified with whole tongue Shh immunoreactions. Tissue sections confirmed that Shh immuno-positive locations in fact were fungiform papillae (Figure 3B).

The general papilla pattern in mutant and WT tongues was comparable, across anterior tongue and on ventral tongue where the dorsal epithelium extends over the tip; and, absent from the intermolar eminence. Further, papilla number was similar in E14.5 mutant and WT tongues (Figure 3C), as shown in E15.5 and 16.5 tongues (Figure 2E). However, papilla density, or papillae per tongue area, was 2.5 greater in mutants (Figure 3D). With a reduced epithelial area on the shorter Wnt5a mutant tongue, therefore, maintenance of papilla number resulted in a crowded, dense fungiform papilla array. But a patterned distribution was retained; papillae were not spatially disorganized or random. Nor were papillae induced in typically papilla-free areas, the intermolar eminence or median furrow.

Another ectodermal specialization, the whisker follicle, also is positive in Shh immunoreactions (Figure 3E). Number of whisker follicles was similar in WT and mutant mice (Figure 3F). Follicles were distributed differently in mutants, however, due to the altered mandible structure that expanded the lower jaw. A follicle - free midline separation was observed in the mutants with bilateral patterning of follicles.

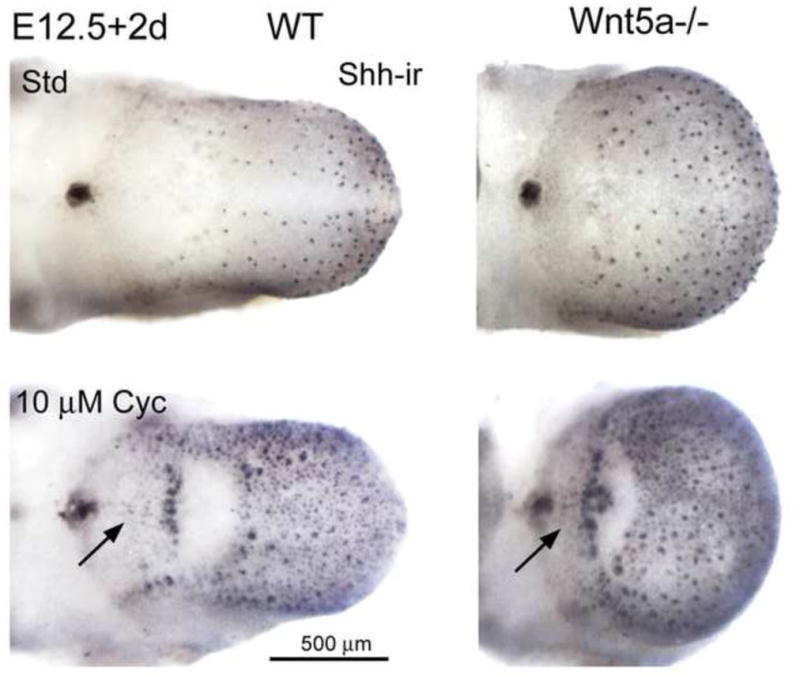

Wnt5a mutant tongues respond to Shh disruption in culture with increased numbers of papillae

We observed that Shh labeled each fungiform papilla in WT and Wnt5a−/− embryo tongues (Figure 3A) and importantly found that the general pattern of Shh-positive papillae was not perturbed in Wnt5a−/− tongues, although papilla density was increased. Because Shh regulates papilla induction, development and pattern (Liu et al., 2004; Mistretta et al., 2003), we tested Shh signaling effects in Wnt5a mutant tongues. Whole tongue organ cultures were set at E12.5 and maintained for two days. In standard medium, papillae developed in patterns comparable to in vivo embryos in both WT and mutant tongues (Figure 4, Std). When cyclopamine (Cyc) was added to WT and mutant tongue cultures, to disrupt Shh signaling at the receptor interface (Chen et al., 2002), there was ectopic expression of Shh in “between - papilla” locations and on the intermolar eminence, normally a papilla - free region (Figure 4, Cyc, arrows). Thus, Shh signal disruption had comparable effects on fungiform papillae in WT and mutant tongues. This indicates that Shh-mediated molecular programs regulating papilla formation are intact in Wnt5a mutant tongues.

Fig. 4. Disruption of Shh signaling in WT and Wnt5a mutant tongues.

E12.5+2 day whole tongue cultures, immunoreacted for Shh (Shh-ir). WT and Wnt5a−/− tongues in culture with standard medium (Std) have a typical distribution of fungiform papillae and retain the single posterior circumvallate. The intermolar eminence is papilla-free, as in vivo. With added cyclopamine (Cyc) to disrupt Shh signaling, ectopic Shh immunoloci are apparent in between the fungiform papillae and on the intermolar eminence area of WT and Wnt5a−/− cultures (arrows). Responses of Wnt5a−/− tongue to exogenous cyclopamine are similar to WT tongues. Scale bar: 500 μm for all images.

Epithelium and mesenchyme in Wnt5a mutant tongues and papillae

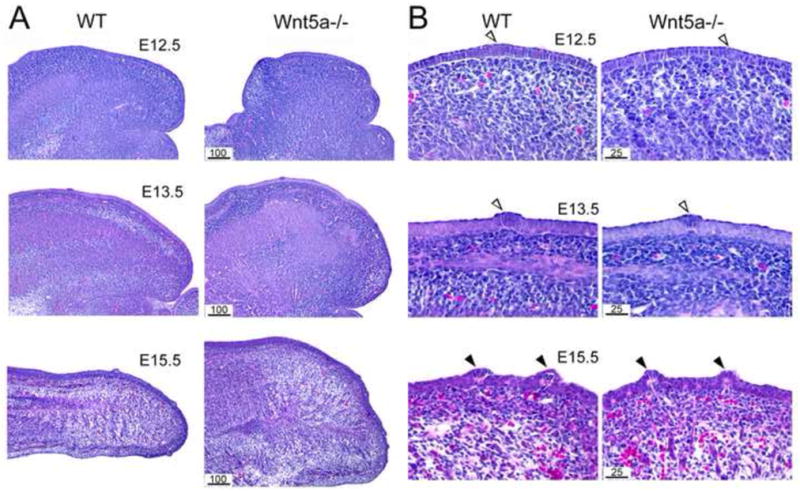

To examine tissue phenotypes in the Wnt5a−/− tongues, serial sagittal sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Low power images illustrate that Wnt5a null tongues are shorter and raised or thicker compared to WT (Figure 5A). Epithelial thickness and general mesenchymal cell arrangement are similar between WT and mutant tongues at E12.5 and 13.5 (Figure 5B). Quantification of epithelial thickness at E12.5, at three different regions (six serial sections at each region) of WT and mutant tongues, demonstrated an average of 12 μm for the essentially columnar cell layer. The timing of papilla placode appearance also is similar. The first sign of epithelial thickenings was noted at E12.5 and distinct placodes were obvious at E13.5 (Figure 5B, E12.5, E13.5, open arrow heads).

Fig. 5. Epithelial and mesenchymal tissues in WT and Wnt5a mutant tongues and fungiform papillae.

E12.5-15.5 sagittal sections from WT and Wnt5a−/− tongues, stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A: Low power images demonstrate that Wnt5a−/− tongues are shorter and thicker or ‘higher’, but without obvious tissue disruption. B: Higher power images illustrate that development of lingual epithelium and fungiform placodes and papillae in Wnt5a−/− is similar to that in WT. Open arrowheads point to clusters of epithelial cells that are a first indication of a placode at E12.5 and obvious developing, fungiform papilla placodes at E13.5. Solid arrowheads point to well developed fungiform papillae at E15.5. Scale bars: noted in μm units for WT and mutant section pairs.

At E15.5 the mutant tongue is much thicker overall than WT (Figure 5A, E15.5). Mesenchymal tissues in the anterior tongue have differentiated further and are in a dense band under the lingual epithelium of WT and mutant tongue (Figure 5B, E15.5). The well developed fungiform papillae exhibit a typical mesenchymal core and epithelial covering in both WT and −/− tongues (Figure 5B, E15.5, filled arrowheads).

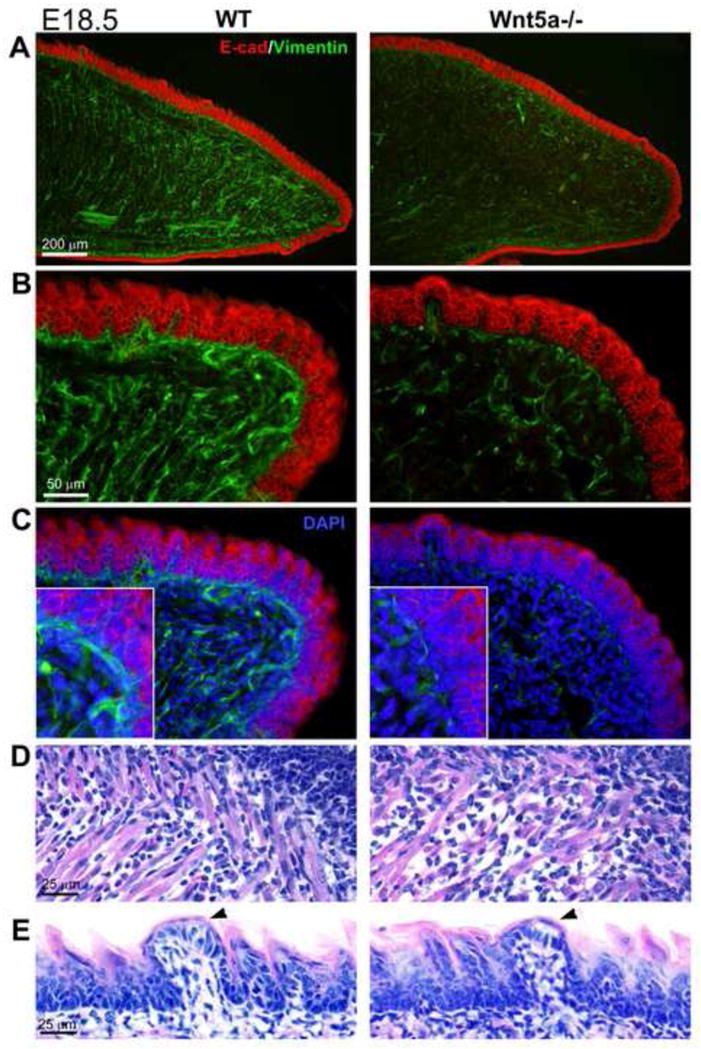

We studied the more differentiated tongues at E18.5 with immunoreactions for E-cadherin to label epithelium, vimentin to distinguish mesenchymal cell cytoskeleton, and hematoxylin and eosin (Figure 6). The stratified epithelium is of similar thickness in WT and mutant tongues, although there is an impression of some flattening of the nongustatory filiform papilla spines at the tip in mutants (Figure 6A, B, E).

Fig. 6. Epithelial and mesenchymal tissues in E18.5 WT and Wnt5a mutant tongues and fungiform papillae.

Sagittal sections from E18.5 WT and Wnt5a−/− tongues, immunoreacted for E-cadherin and vimentin, and stained with DAPI and hematoxylin and eosin. A, B: E-cadherin immunoreactions (red) in WT and Wnt5a−/− tongues, in low (A) and higher power (B) views, have similar epithelial thickeness. However, vimentin immunoreactions (green) illustrate a much reduced cytoskeletal network in mesenchymal cells of mutant compared to WT tongues. C: With DAPI staining it is clear that cell numbers are not reduced in the mutant mesenchyme. Insets at high magnification illustrate that vimentin expression is decreased by cells in mutant tongue relative to cells in WT. D: In hematoxylin and eosin sections, muscle fibers are seen throughout tongue mesenchyme, but with some lack of clear patterning in mutant tongues. E: Fungiform papillae (arrowheads) in both WT and mutant tongues have a characteristic epithelial covering over a connective tissue core, and a cell collection of the presumptive taste bud is in the apical epithelium (at arrowhead). Scale bars: apply to WT and mutant pairs.

Disruption of lingual mesenchymal core tissues is seen in Wnt5a−/− tongues with striking reduction in the intermediate filament protein vimentin, producing a mesenchyme with less dense cytoskeletal elements (Figure 6A, B). Co-staining with DAPI illustrates that mesenchymal cell number is not reduced in mutant tongues (Figure 6C), indicating that the cells on average produce less vimentin. The reduced vimentin label in Wnt5a mutant tongues was highly consistent across serial sections, for paired WT and mutant tongue sections mounted together on slides for immunoreactions.

Although not studied in detail, tongue muscle fibers also have a looser and less organized arrangement in mutant compared to WT tongues (Figure 6D). Notably, fungiform papillae were obvious and well formed in mutant tongues and contained an apical collection of cells that form the early taste bud (Figure 6E, arrowheads).

In summary, the integrity of mesenchymal tissues was substantially disrupted in Wnt5a mutant tongues at later embryo stages. On the other hand, from E12.5 to E18.5, developing papilla placodes and fungiform papillae in mutant tongues retained the temporal progression characteristic of WT and acquired collections of epithelial cells that presumably represent early taste bud formation.

Tissue and stage specific alterations in cell proliferation in mutant compared to WT anterior tongue

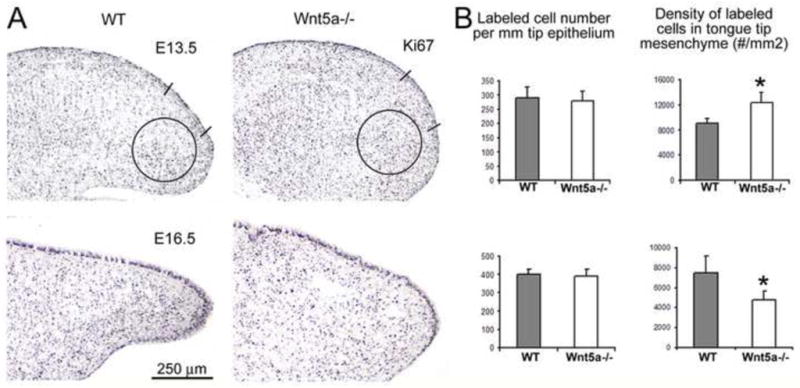

To address possible cellular mechanisms related to shortened anterior tongues and mesenchymal disruption in Wnt5a mutants, we used Ki67 immunoreactions to measure cell proliferation (Figure 7A). Two stages were studied: E13.5 when the tongue has formed but the anterior region is extending rapidly and papilla placodes are forming; and, E16.5 when the tongue is well shaped, although outgrowth continues, and papillae are well developed but still differentiating.

Fig. 7. Cell proliferation in WT and Wnt5a mutant tongues.

Ki67 immunoreactions to measure cell proliferation in WT and Wnt5a−/− tongue epithelium and mesenchyme, at E13.5 and E16.5. A: Photomicrographs of sagittal tongue sections labeled with Ki67. Two straight lines mark the region where labeled epithelial cells were counted. Circles at the tongue tip illustrate area in which labeled mesenchymal cells were counted. Scale bar: 250 μm, applies to all images. B: Histograms for counts and density of Ki67 labeled cells, in epithelium and in mesenchyme (n = 3 each WT and mutant). Numbers of cells per epithelial length does not differ between WT and mutant tongues at E13.5 or E16.5. At E13.5, density of Ki67+ mesenchymal cells in the tongue tip is increased in Wnt5a−/− compared to WT. At E16.5, there is a decreased density in mesenchymal cells in Wnt5a−/− compared to WT.

Cell counts in Ki67-labeled WT and mutant tongues revealed that there were no differences in proliferation in the lingual epithelium at either stage (Figure 7B). However, at E13.5 the density of proliferating cells was greater in mutant, anterior tongue mesenchyme compared to WT. At E16.5, on the other hand, proliferating cell density was reduced in mutant mesenchyme. BrdU data were similar to Ki67 immunoreactions, for both stages (Supplemental Figure 3). Thus, loss of Wnt5a has tissue and stage specific consequences for cell proliferation, comparing early tongue development to later stages. The decreased density of proliferating mesenchymal cells in later mutant embryos is accompanied by the emerging disruption of the lingual mesenchyme shown in Figure 6.

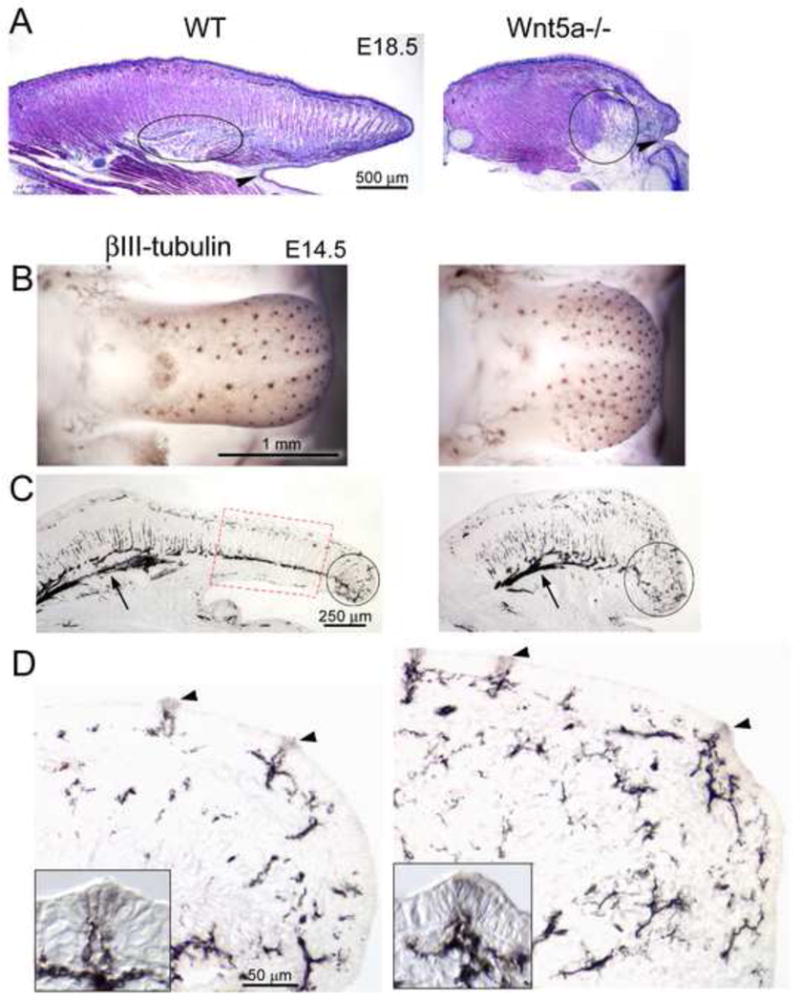

Ankyloglossia and innervation in Wnt5a mutant tongues

In sagittal sections of entire WT and Wnt5a−/− tongues there was not only a shortened mutant tongue, but also a phenotype that is effectively an ankyloglossia. In ankylglossia the lingual frenum is anteriorly placed or the ventral tongue musculature is extensively attached to the floor of the oral cavity, limiting tongue movement (Lalakea and Messnet, 2003a, b; Morita et al., 2004). Low power images of E18.5 tongues illustrate that the truncated tongue in late stage mutants results in a much shortened, anterior “free tongue” region that is bound near the tip (Figure 8A, arrow heads). In the mutant tongue about 0.35 mm extends beyond the attachment to the floor of the oral cavity compared to about 1.60 mm in WT. In fact, this shortening relative to tongue attachment location already is obvious at E12.5 (Figure 5A). Not only is the anterior-most attachment of the tongue to the oral cavity floor in a more “forward”, relative position in Wnt5a−/− tongues, but also the region of ventral tongue muscle attachment is noticeably disorganized in mutants (Figure 8A, circled regions).

Fig. 8. Ankylglossia, but intact innervation, in Wnt5a−/− tongues compared to WT.

A. E18.5 sagittal tongue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The Wnt5a−/− tongue has a much truncated tongue tip with an attachment to the floor of the mouth that leaves little free anterior tongue (arrowheads), similar to an ankyloglossia. Circled areas illustrate the ventral tongue muscle attachment to the floor of the mouth, which has an under-developed and disorganized phenotype in Wnt5a−/−. B – D, E14.5, βIII-tubulin immunoreactions. B. In whole tongues, βIII-tubulin label is seen in each fungiform papilla in WT and Wnt5a−/−. C. In sagittal sections, the distribution of nerve fibers in Wnt5a−/− tongue is similar to that in WT. Arrows point to the nerve branches in posterior tongue, which are similar in WT and mutant. A red box in the WT tongue denotes a region that is essentially ‘eliminated’ in the mutant tongue. Circled areas show the complex branching nerve trajectories in the tongue tip. D. High power images demonstrate the course of nerve fibers in a subepithelial band and the intensely labeled innervation in the mesenchymal core of each fungiform papilla (arrowheads and insets) in WT and Wnt5a−/− tongues. Scale bars in WT apply to paired Wnt5a−/− tongues.

To learn whether the profoundly altered tongue shape, size and effective ankyloglossia are associated with a disruption in Wnt5a−/− tongue and papilla innervation, βIII-tubulin immunoreactions were used to label nerves at E14.5. Although papillae are more densely distributed in mutant tongues, nerve label is seen in each fungiform papilla in WT and mutant whole tongue (Figure 8B).

In sagittal sections through the entire tongue at E14.5 a clear ankyloglossia, or limited free anterior tongue, again is illustrated (Figure 8C). Notably, though, nerve fibers are in similar distributions in the posterior half of WT and mutant tongues (Figure 8C, arrows). Labeling the tongue innervation pattern makes clear a loss of tongue tissue anterior to the lingual frenum, or attachment to the floor of the mandible, in mutant tongue (see red boxed region, Figure 8C, WT; lost in mutant tongue). In anterior tongue, the shortened structure of Wnt5a null tongues accommodates tortuous, branching nerve trajectories that are characteristic of the extreme tip of the WT tongue (Figure 8C, circled regions).

The anterior tongue branching patterns are essentially similar in WT and mutant tongues, coursing in a rough band under the epithelium and directed to individual fungiform papillae (Figure 8D). Importantly, each fungiform papilla in mutant and WT tongues has a dense distribution of fibers within the mesenchymal core and fibers penetrate into the papilla epithelium (Figure 8D, arrowheads and insets). Overall, in the context of a very short anterior tongue that is bound to the floor of the oral cavity, tongue and papilla innervation remains intact and patterned.

The short Wnt5a mutant tongue is associated with cleft palate

Ankyloglossia is not the only Wnt5a mutant phenotype that would alter oral function. The broad, high, short tongues of Wnt5a −/− mice seen in SEMs in Figure 2 suggested a potential protrusion into the nasal region. Previous work reported cleft palate in Wnt5a −/− mice (He et al., 2008). We scanned the superior oral cavity at E13.5-18.5 and found that the truncated tongue indeed was associated with a cleft palate at all stages (Supplemental Data Figure 4). Palate shelves in mutant mice did, however, have apparent rugae (Supplemental Data Figure 4, E14.5, 18.5, arrows). Thus, the shelf tissue has differentiated but could not elevate or meet, possibly because the short, high tongue was an impediment.

Wnt5a WT and mutant tongue length in culture: potential mandible constraints and exogenous Wnt5a effects

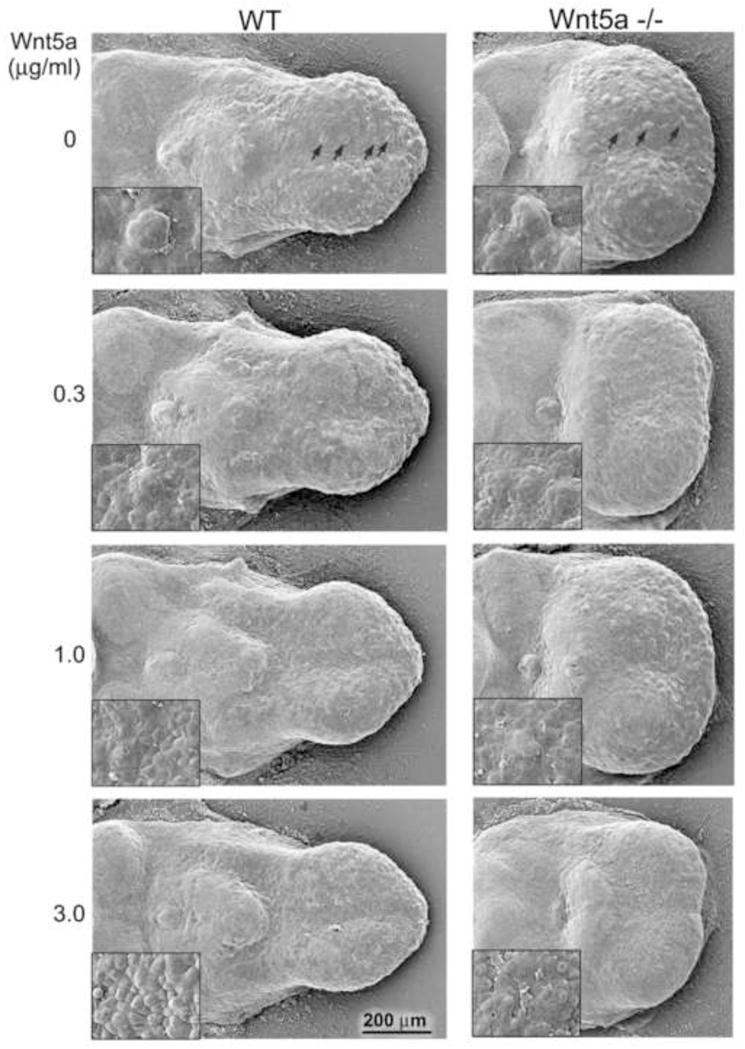

To learn whether Wnt5a mutant tongues would increase in length compared to wild type, when cultured free of the shortened mutant mandible, whole tongues were dissected at E12.5 and maintained in culture for two or three days. In standard medium, in the absence of added Wnt5a, mutant tongues remained at about 60% of WT length (Figure 9, 0 μg/ml concentration). Even without potential mechanical constraints from a short mandible, mutant tongues did not grow to make up the decreased length that already is apparent in vivo at E11.5 (Supplemental Figure 2). Also Wnt5a mutant tongues in culture are wider than WT tongues (Figure 9), as are those in vivo (Figure 2).

Fig. 9. In vitro effects of exogenous Wnt5a protein in WT and Wnt5a mutant tongues.

Scanning electron micrographs of WT and Wnt5a−/− E12.5+2 day mouse tongue cultures with increasing concentrations of Wnt5a protein. The E12.5 tongue (see Figure 3) was dissected from the mandible and maintained in culture for 2 days without (0) or with addition of exogenous Wnt5a protein (0.3 to 3.0 μg/ml). After 2 days in culture, fungiform papillae and the single circumvallate papilla form in WT and Wnt5a−/− tongues (0 concentration). Wnt5a−/− tongues remain short and wide in culture, even without in vivo constraints of a short mandible. With addition of Wnt5a, formation of fungiform papillae is suppressed in a dose-dependent manner in WT and Wnt5a−/− tongues (0.3–3.0 μg/ml). Insets demonstrate an apparent hyperproliferation of epithelial cells accompanying the loss of papillae. Scale bar: 200 μm applies to all images except insets.

To test whether exogenous Wnt5a protein would rescue the shortened tongue phenotype in Wnt5a mutants, recombinant Wnt5a was added to whole tongue cultures at E12.5, maintained for two days. Across a range of concentrations, length was not increased in WT or mutant tongues (Figure 9, 0 to 3.0 μg/ml). However, a higher concentration of Wnt5a (5 μg/ml) in WT tongues cultured for two days, or an extended, three day time in culture with 3.0 μg/ml Wnt5a, resulted in WT tongues of increased length and decreased width compared to tongues in standard medium (Supplemental Figure 5). Thus, added Wnt5a in vitro can increase tongue length, consistent with observed shorter tongues in Wnt5a mutants.

Exogenous Wnt5a alters fungiform papilla development in culture, and mesenchymal cell proliferation is decreased and vimentin expression is increased

In the range of exogenous Wnt5a concentrations that does not alter tongue length (0.3 – 3.0 μg/ml), fungiform papillae were profoundly reduced or eliminated in both WT and mutant tongue cultures relative to standard medium (Figure 9, compare 0 to 3.0 μg/ml Wnt5a). Lingual topography seen in SEMs was altered with added Wnt5a, suggesting changes in the epithelial layers (Figure 9, insets).

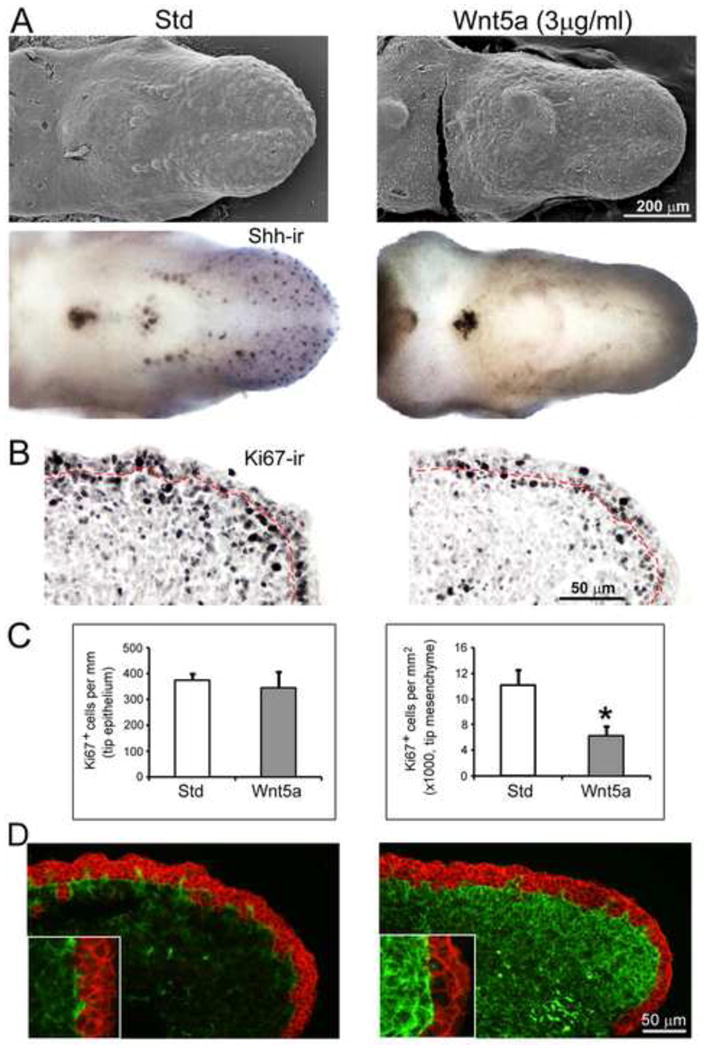

We further studied the epithelium by quantifying cell proliferation in E12.5 plus two day WT tongue cultures, in standard medium or with 3 – 5 μg/ml exogenous Wnt5a (Figure 10A). As suggested by SEM analysis in Figure 9, the lingual epithelium had lost fungiform papillae, that would normally form, but Ki67 positive epithelial cell numbers were not different in cultures with Wnt5a compared to standard medium (Figure 10B, C). Therefore, decreased cell proliferation in the epithelium, per se, did not account for loss of fungiform papillae.

Fig. 10. In vitro effects of exogenous Wnt5a protein on epithelial and mesenchymal cell proliferation and cytoskeleton in WT tongues.

A: Scanning electron micrographs and whole tongue Shh immunoreactions (Shh-ir) of E12.5 WT tongues in culture for two days with standard medium (Std) or with added protein (Wnt5a). Shh immunohistochemistry was performed first, followed in the same cultures with SEM. After two days in Std, fungiform papillae develop on the anterior oral tongue and are labeled with Shh-ir. With added Wnt5a, fungiform papillae do not form and there is no Shh-immuno label in anterior tongue. The single circumvallate papilla is maintained with exogenous Wnt5a and Shh immunoproduct is very intense in the papilla. Scale bar: 200 μm for all images. B and C: Ki67 immunoreactions (Ki67-ir) were used on tongue culture sections to label proliferating cells in epithelium, demarcated with a dotted red line, and in mesenchyme and quantified in histograms in C (n = 3, each group). Density of proliferating cells was the same in epithelium in Std medium (open bars) and with added Wnt5a (filled bars), but was strikingly reduced in the mesenchyme of tongue cultures with added Wnt5a. [*P<0.05.] D: In immunoreactions to E-cadherin (red) and vimentin (green), a dense increase of vimentin-positive cytoskeleton is seen in tongue mesenchyme with added Wnt5a in culture. Insets at higher magnification illustrate the intense vimentin expression in culture with Wnt5a, compared to standard medium.

However, in mesenchyme at the tongue tip, the density of proliferating cells was decreased substantially in cultures with added Wnt5a (Figure 10B, C). In concert with the demonstrated increased mesenchymal cell proliferation in early stage, E13.5 mutant tongues (Figure 7), this suggests that Wnt5a balances positive proliferative effects in early anterior tongue. Furthermore, in tongue cultures with exogenous Wnt5a, expression of vimentin was substantially increased relative to tongues in standard cultures (Figure 10D). Overall, with Wnt5a addition there is decreased cell proliferation density in a more vimentin-rich mesenchyme. The increase in vimentin cytoskeleton could generate an adhesive environment that is permissive for cell movement in the mesenchyme matrix.

Wnt5a and β-catenin dependent Wnt signaling

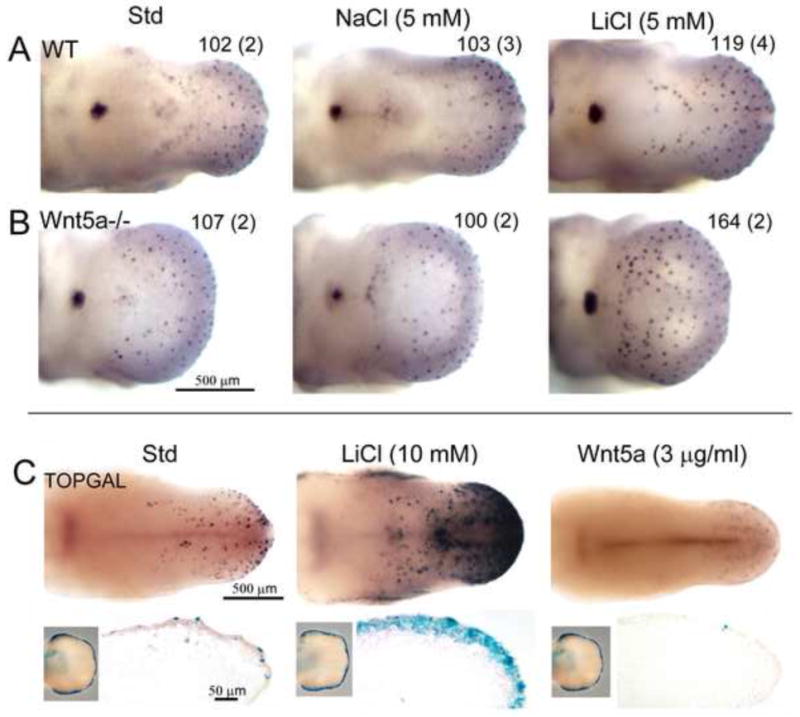

In previous studies we demonstrated that Wnt10b, via canonical β-catenin-dependent and Lef1 signaling, increased fungiform papillae on the developing tongue (Iwatsuki et al., 2007). When LiCl was added to tongue cultures to activate canonical signaling, papillae also were increased. To explore interactions between canonical and noncanonical (Wnt5a) Wnt signaling in papilla development, we used LiCl to activate canonical Wnt signaling in E12.5 WT and Wnt5a mutant tongue cultures and quantified the number of fungiform papillae.

With LiCl in WT tongue cultures, papilla number was increased by about 20% relative to tongues in standard medium or with added NaCl (Figure 11A) replicating our previous experiments (Iwatsuki et al., 2007). In Wnt5a mutant tongue cultures addition of LiCl also increased papilla number, but by about 60% relative to standard medium or with added NaCl (Figure 11B). In the absence of Wnt5a, therefore, the effect of canonical Wnt activation in increasing fungiform papilla number is exaggerated, suggesting that Wnt5a provides a brake or balance for maintaining normal papilla number.

Fig. 11. Wnt5a interacting with canonical Wnt signaling WT and Wnt5a mutant tongues.

Whole tongue organ cultures of WT and Wnt5a−/−, and TOPGAL tongues, with canonical Wnt signaling activation and suppression. A and B: Photomicrographs of E12.5+2 day tongue cultures with exogenous salts, immunoreacted for Shh in WT (A) and Wnt5a−/− (B) tongues. Number in the right top corner presents the average of total fungiform papilla number in cultured tongues (n = 2 – 4 tongues for each condition, noted in parentheses). In standard medium (Std) and with added 5 mM NaCl, numerous Shh-positive fungiform papillae and the single circumvallate papilla are apparent in both WT and Wnt5a−/− tongues. About 100 fungiform papillae form in these conditions. With addition of 5 mM LiCl, there is an increase of fungiform papilla number by about 20% in WT cultures. A much greater increase in papilla number, by about 60%, is obtained in response to LiCl in Wnt5a−/− tongue cultures. Scale bar: 500 μm for all images. C: Photomicrographs of E12.5+2 day TOPGAL mouse tongue cultures, and sagittal sections, with X-Gal staining to demonstrate canonical Wnt signaling activity. X-Gal staining (blue) was performed on limb buds (insets, left bottom corner) to select tongues from X-Gal staining positive embryos for culture. Intensity of blue signals in limb buds is similar across groups. In Std cultures, epithelial cells on fungiform papillae are labeled in the anterior tongue region. Addition of LiCl (10 mM) leads to a dramatic increase in blue staining intensities, representing enhanced activation of canonical Wnt signaling. Signals in sectioned cultures are distributed in the thickened epithelium. In cultures with exogenous Wnt5a protein (3 μg/ml) blue staining is essentially eliminated. Scale bars: 500 μm for whole tongue images and 50 μm for sections.

We further tested potential interactions between Wnt5a and canonical Wnt signaling using TOPGAL reporter mice with a Wnt-dependent β-galactosidase reporter (DasGupta and Fuchs, 1999). E12.5 TOPGAL mouse tongues were cultured for two days in standard medium, or with added LiCl (5, 10 or 15 mM) or Wnt5a (3.0 μg/ml) (Figure 11C). Whereas LiCl at 10 or 15 mM predictably increased β-galactosidase positive fungiform papillae and expression in tongue epithelium, added Wnt5a markedly decreased Wnt/β-catenin signaling as measured by X-Gal staining. In agreement with the idea that exogenous Wnt5a in culture effectively eliminates canonical Wnt activity and suppresses papilla development in lingual epithelium, staining for Shh (which is dependent upon canonical Wnt signaling in the context of developing papillae) was severely reduced by addition of 3.0 μg/ml Wnt5a (Figure 10A).

These results demonstrate that canonical β-catenin dependent signaling is exaggerated in Wnt5a mutant tongue and that the TOPGAL readout for canonical signaling is eliminated with exogenous Wnt5a in tongue cultures. This is strong evidence for the idea that Wnt5a suppresses canonical Wnt signaling in papilla generation.

Ror2 receptor for Wnt signaling in wild type and Wnt5a mutant tongues

Ror2 can act as a co-receptor for Wnt5a and is suggested as mediating Wnt5a signaling in a noncanonical or β-catenin independent pathway (Gao et al., 2011; Nishita et al., 2006; Yamamoto et al., 2007). We examined localization of Ror2 in WT and Wnt5a mutant tongues. Ror2 immunoreactions in E14.5 tongue demonstrated dense immunoproducts in epithelium and scattered throughout mesenchymal tissue (Supplemental Data Figure 6). These data suggest that Wnt5a protein in tongue mesenchyme could signal via the Ror2 receptor in tongue epithelium to alter papilla number, by opposing the Wnt/β-catenin pathway as observed in Figure 11.

DISCUSSION

With in vivo gene deletion and in vitro organ cultures we have identified Wnt5a as a major developmental regulator of tongue size and shape, mesenchymal integrity, and taste papilla development, pattern and density. Compared to wild type, the short, wide and raised Wnt5a mutant tongue phenotypes are apparent from the early stage of E12.5 through E18.5 and are associated with a cleft palate. The extremely truncated tongue leaves little anterior lingual tissue for free movement, exhibiting an effective ankyloglossia. Substantial effects in lingual mesenchyme of mutants include altered cell proliferation, disorganized tissue patterns and reduced cytoskeletal elements.

However, whereas Wnt5a−/− tongues are shorter than wild type by about 40%, the temporal developmental progression and number of fungiform papillae are retained in mutants, as is papilla innervation. Thus, in the face of an extremely short tongue, general taste papilla pattern is to a large extent maintained. Nevertheless, in shortened mutant tongues, the density of papillae is radically altered, though, and participation of Wnt5a in fungiform papilla development can be demonstrated with in vitro experiments. Antagonistic effects of Wnt5a on β-catenin-dependent Wnt signaling in tongue epithelium demonstrate the necessity of an essential balance between non-canonical Wnt5a and canonical Wnt pathways in fungiform papilla regulation.

Separate genetic regulation for tongue size and shape versus papilla pattern, development and innervation

Wnt5a mutants and lingual papilla development

There has been no previous assessment of papilla number or pattern in a tongue with radically altered size and shape. Thus our experiments bring forward new basic information that demonstrates a separation of the molecular regulation for tongue size and shape from that for development of the resident epithelial appendages, the lingual papillae. Although the native number of fungiform papillae is retained in shortened tongues of Wnt5a mutants, papilla density is more than double that in wild type. During embryonic development, fungiform papillae form in a patterned array on the anterior part of oral tongue (Mbiene and Mistretta, 1997). Several molecular signals are involved in maintaining spatial patterns of fungiform papillae, including Shh (Liu et al., 2004; Mistretta et al., 2003), Bone morphogenetic proteins (Bmp) and noggin (Zhou et al., 2006), and epidermal growth factor (Liu et al., 2008). Whereas Bmp 2, 4 and 7 act to maintain a papilla-free surround, the antagonist noggin can increase papilla density in organ culture to a point of fused rows of papillae (Zhou et al., 2006). In Wnt5a−/− tongues the zone of inhibition surrounding neighboring papillae must be contracted to allow formation of a high density of fungiform papillae, demonstrating that Wnt5a signals can affect proper spacing of fungiform papillae. This finding also indicates that signaling programs in papilla development are flexible in tolerating a much tighter inhibitory surround than in the wild type embryo. Furthermore the increased density does not lead to a disorganized placement of papillae (for example, some extremely dense regions, some sparse) or invasion of usually papilla-free regions (for example, the median furrow).

In shortened Wnt5a null mutant tongues, not only do fungiform papillae develop on the anterior oral tongue in the same number as in wild type, but also the single circumvallate papilla develops in the midline on the posterior oral tongue border, presumptive taste bud cell clusters form in fungiform papillae, and nongustatory filiform papillae form between fungiform papillae at late embryonic stages. These data demonstrate that, in spite of the dramatic alteration of tongue size and shape in Wnt5a mutants, proper lingual papilla induction and cell differentiation are sustained. The tongue therefore is apparently similar to other systems including lung (Li et al., 2002; 2005), limb (Yamaguchi et al., 1999) and intestine (Cervantes et al., 2009), in which Wnt5a deletion alone does not alter initial cell fate and differentiation although growth and elongation of principal structures are substantially reduced.

Wnt5a deletion does not alter lingual innervation

Whereas papilla density is increased by more than twofold on truncated Wnt5a mutant tongues and a much foreshortened anterior tongue almost eliminates a freely moving tip, the overall pattern of lingual innervation is maintained and traverses a progressively disorganized mesenchyme, with decreased cell cytoskeleton components, to densely innervate each fungiform papilla core. In rodent embryonic development, sensory nerve fibers from trigeminal, geniculate and petrosal ganglia enter the tongue at distinctive entry points, along with motor fibers from the hypoglossal nucleus (Mbiene and Mistretta, 1997). Nerve fibers do not distribute randomly or homogeneously to mesenchyme under the lingual epithelium, but rather project densely to regions under forming papillae (Mbiene and Mistretta, 1997). This precision in path finding is retained in Wnt5a mutant tongues. To our knowledge the current work with Wnt5a mutants is the first in vivo examination of innervation in a tongue that is radically altered in size, shape and papilla density. Factors that direct patterns of lingual innervation, whether target growth factor distributions and/or interactions among the growing neurites, are not compromised by an extreme mis-programming of tongue size.

Wnt5a in tongue shape, with cleft palate and ankyloglossia

Development of tongue and palate must be coordinated in forming oral-nasal structures (Ferguson, 1988; Mueller and Callanan, 2007). Recently it was shown that Wnt5a mutants exhibit a complete cleft palate, which we also have observed through E18.5 (He et al., 2008). We show that rugae are apparent on mutant palatal shelves that have not rotated, demonstrating that shelf tissues are differentiated to some degree. The high, short tongue of Wnt5a−/− mice presents a protrusion into the nasal region that is a potential impediment for elevation of the palatal shelves.

In addition, the short tongue in Wnt5a mutants leaves only a very truncated portion of anterior free tongue that is not attached to the floor of the oral cavity, reminiscent of ankyloglossia (Lalakea and Messner, 2003a,b; Mueller and Callanan, 2007). There is a much fore-shortened tongue protruding beyond the usual attachment point and apparent disruption of tissues at the attachment. We propose that the effective ankyloglossia contributes to death in Wnt5a mutants soon after birth. In LGR5 (leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 5) mutant mice, which also have ankyloglossia, the constrained tongue movement prevents optimal suckling and appropriate weight gain after birth (Morita et al., 2004). Marked distension results from air in empty stomachs which places pressure on the diaphragm; therefore, respirations are gasping and the animals become cyanotic. This contributes to perinatal lethality. Similarly, the dramatically shortened free anterior tongue in Wnt5a−/− mice, coupled with a cleft palate, is likely to contribute to suckling and respiratory problems responsible for the perinatal lethality of Wnt5a null mutants.

Wnt5a in organ growth, and tissue and stage specific effects in regulating cell proliferation and cytoskeleton

In Wnt5a−/− embryos, tongues are shorter in every oral and pharyngeal region, and Wnt5a null tongues are wider than wild type and high or thick in the mid-region. The phenotype is not rescued in organ cultures when the embryonic tongue is dissected and maintained free from constraints imposed by the mandible. This suggests that the short tongue in Wnt5a mutants is not caused by limited mandible growth in vivo but rather that Wnt5a is required for tongue outgrowth and shape. Indeed addition of Wnt5a at high concentration in cultures leads to increased tongue length compared to standard medium conditions.

Localization of Wnt5a mRNA and protein in anterior embryonic tongue, primarily in the subepithelial band of mesenchyme, imposes a tissue restriction for principal actions in tongue outgrowth. Similar to expression in growing distal limb mesenchyme (Yamaguchi et al., 1999), Wnt5a is in a graded distribution in the embryonic tongue, more densely located in anterior tissue. The effects of Wnt5a in restricting tongue growth match roles in anterior-posterior axis extension of limb, tail and snout (Yamaguchi et al., 1999) and elongation in ductal outgrowth in prostate and mammary gland (Huang et al., 2009; Roarty and Sierra, 2007). Further, in Wnt5a null mutants the small intestine is dramatically shortened (Cervantes et al., 2009) and the trachea is truncated (Li et al., 2002; 2005). Thus, roles for Wnt5a in organ growth and extension are widely documented.

Proliferation in lingual epithelium and mesenchyme

Accumulating evidence demonstrates that, during morphogenesis, Wnt5a regulates cell proliferation in a tissue - specific manner. Wnt5a suppresses epithelial proliferation in prostate (Huang et al., 2009), mammary gland (Roarty and Serra, 2007) and lung (Li et al., 2002), but promotes proliferation in gut epithelial and mesenchymal cells (Cervantes et al., 2009), and in endothelial (Cheng et al., 2008; Masckauchan et al., 2006), limb progenitor (Yamaguchi et al., 1999) and distal lung bud cells (Loscertales et al., 2008). In E13.5 mouse palate, deletion of Wnt5a leads to an increase in proportion of proliferating mesenchymal cells in anterior palate, but a decrease in the posterior region (He et al., 2008).

In WT and mutant tongue epithelium, there were no differences in cell proliferation at either E13.5 or later at E16.5. Nor was proliferation altered in epithelium of E12.5 plus 2 day tongue cultures, with added Wnt5a. However, in mutant tongue tip mesenchyme, the density of proliferating cells was increased at E13.5 compared to wild type but decreased at E16.5. At E13.5 when a shortened tongue already is apparent, the increased proliferation in Wnt5a mutant lingual mesenchyme suggests that decreased tongue length is not directly related to production of fewer cells. Rather, the increased proliferation correlates with increased tongue width and thickness or height of the raised tongues. In agreement with increased proliferation of early stage mesenchyme in Wnt5a−/− tongue, with added Wnt5a in E12.5 WT tongue cultures, mesenchymal cell proliferation is reduced.

Later, at E16.5, Wnt5a apparently promotes cell proliferation in tongue mesenchyme because the density of proliferating cells is decreased in mutant tongues. Thus, Wnt5a signaling could balance against rampant mesenchymal proliferation in early stages but support proliferation in the mesenchyme later as the tongue tip extends.

Tongue mesenchyme and vimentin expression

Morphogenesis requires not only cell proliferation and differentiation but also massive cell movement and rearrangements to shape organs. Wnt5a exerts strong controls for cell orientation, polarity and movement in response to chemical cues in target tissues (He et al., 2008; Witze et al., 2008). Noncanonical Wnts exert such cellular regulation by altering cytoskeletal organization (Bowerman, 2008; Dissanayake et al., 2007; Jonsson and Anderson, 2001). Vimentin is a major intermediate filament protein in mesenchyme cells and a key cytoskeleton component in maintaining cell shape, cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, migration, and organization of cell surface molecules involved in adhesion and signaling (Ivaska et al., 2007). Cells with reduced vimentin have altered motility (Eckes et al., 1998) and compromised matrix contacts (Sato et al., 2003). Wnt5a is known to increase extracellular matrix components in lung fibroblasts and matrix adhesion in dermal fibroblasts (Kawasaki et al., 2007; Vuga et al., 2009), and acting via the Ror2 co-receptor, Wnt5a promotes migration of fibroblasts in culture (Nishita et al., 2010). In melanoma cells Wnt5a promotes cell motility and with high Wnt5a, vimentin expression is increased and cells are highly invasive (Dissanayake et al., 2007). In sum the literature indicates that noncanonical Wnt5a can control cell motility by altering cytoskeletal vimentin expression.

We observed that vimentin expression in Wnt5a −/− tongue mesenchyme is much reduced but increased in WT tongue cultures with added Wnt5a. These results are consistent with roles for Wnt5a in supporting cell migration in the embryonic tongue mesenchyme, by maintaining vimentin expression for the adhesion interactions that promote motility.

Overall our data suggest that Wnt5a does not directly regulate cell proliferation in the tongue epithelium, but does sustain cell proliferation and the maintenance of a vimentin-rich, intact cytoskeleton in mesenchyme. With Wnt5a deletion there is a shorter tongue with altered mesenchymal cell proliferation and decreased vimentin expression that would impair cell migration necessary for maintaining tongue size and shape.

Wnt5a signaling and Shh

Shh is important in induction, differentiation and patterning of fungiform papillae (Hall et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2004; Mistretta et al., 2003) and in a proposed interactive loop, Wnt/β-catenin activates Shh signaling that in turn inhibits Wnt/β-catenin in fungiform papilla formation (Iwatsuki et al., 2007). In our present results, Shh is retained as an embryonic fungiform papilla marker in Wnt5a mutant tongues. Thus, endogenous Wnt5a is not necessary for Shh expression in embryonic papillae.

Furthermore when Shh signaling was disrupted in tongue cultures with cyclopamine, fungiform papillae were increased on anterior tongue of both wild type and mutant E12.5 embryos as reported previously (Mistretta et al., 2003). This indicates that Shh is not directly dependent on Wnt5a in regulating fungiform papilla number and pattern.

However, exogenous Wnt5a protein at high concentrations suppresses Shh expression and fungform papilla formation in tongue cultures, suggesting an interaction between Wnt5a and Shh pathways in papilla formation. During prostate, lung and hair follicle development, Shh and Wnt5a are interactive (Huang et al., 2009; Li et al., 2002; 2005; Reddy et al., 2001). Our data are not sufficient to determine comprehensive interactions between Wnt5a and Shh in papilla development or participation with other signaling loops. However, our results are consistent with a model where Wnt5a would suppress Wnt β-catenin signaling, and this in turn would suppress Shh signaling and fungiform papilla development.

Wnt5a and canonical Wnt signaling

Two broad categories for Wnt protein signaling are via the canonical, or Wnt/β-catenin, pathway and noncanonical paths via Wnt/Jnk or Wnt/Ca2+ cascades (Pukrop and Binder, 2008). Because individual Wnts can activate canonical and/or noncanonical paths, dependent on receptor context, a strict classification is not always useful for data interpretation (van Amerongen and Nusse, 2009). Wnt5a has been shown to participate in both noncanonical and canonical pathways (Katoh and Katoh, 2007; McDonald and Silver, 2009; Mikels and Nusse, 2006).

The main signaling pathways identified for Wnt5a in noncanonical models are the planar cell polarity (PCP) path, involving activated Jnk to signal via c-jun; and, the Wnt/Ca2+ path mediated via Ca2+ release (Katoh, 2005; McDonald and Silver, 2009). There are multiple ways for these cascades to interact with Wnt canonical signaling (Mikels and Nusse, 2006; Pukrop and Binder, 2008), for example in a Wnt5a PCP path to synergize with TCF/LEF in activated canonical signaling or acting with receptor Ror2 to inhibit canonical signaling. Therefore, Wnt5a signaling as activating or antagonizing Wnt/β-catenin paths is highly context-specific, dependent on location and concentration of the protein and the types of receptors and other mediators available in the tissue.

Exogenous Wnt5a in culture and proposed paracrine signaling

When Wnt5a is added to tongue cultures there is a dose-dependent decrease in fungiform papilla number. Although this seems to contradict results in Wnt5a null mutants, in which fungiform papilla number is not altered, we propose that redundant Wnt and/or other factors might act to regulate papilla numbers in the mutant embryo. Use of high exogenous protein in vitro reveals potential for noncanonical signaling effects on fungiform papillae. With Wnt5a added to tongue cultures at high concentrations, the decrease in fungiform papilla number suggests that Wnt5a antagonizes Wnt/β-catenin signaling, because the latter when activated leads to increased fungiform papilla development (Iwatsuki et al., 2007).

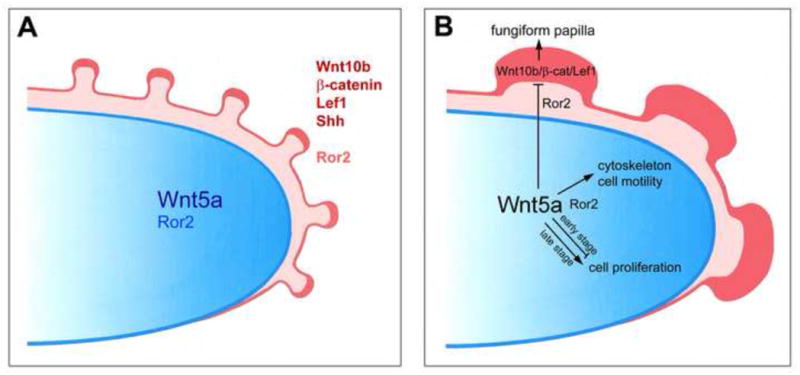

High Wnt5a concentrations could act via the Ror2 co-receptor, which is intensely expressed in the embryonic tongue epithelium (Figure 12A). We do not have functional data to demonstrate that Wnt5a acts via Ror2 in tongue. However, Wnt5a transcripts and protein are intense in mesenchyme just under the lingual epithelium. This position is prime for paracrine signaling to the Ror2 co-receptor in the epithelium, as proposed in intestinal development by Pacheco and MacLeod (2008). Although Wnt5a signaling via Ror2 could act through a Jnk - c-jun cascade to activate canonical Wnt signaling, Wnt5a with co-receptor Ror2 signaling can antagonize TCF/LEF (Li et al., 2008; Mikels and Nusse, 2006; Pukrop and Binder, 2008). If the β-catenin-TCF/LEF pathway is inhibited, fungiform papilla development would be suppressed (Iwatsuki et al., 2007).

Fig. 12.

Proposed model for noncanonical Wnt5a signaling: to regulate mesenchymal cell proliferation, cytoskeleton and migration, and via a paracrine path to suppress canonical Wnt signaling in epithelium and regulate fungiform papillae. A. The tongue diagram illustrates documented canonical Wnt signaling factors Wnt10b, β-catenin, Lef1; fungiform papilla marker Shh; and, Wnt signaling coreceptor R or2, in the tongue papillae (red) and epithelium (light red). Noncanonical Wnt5a (blue), in a graded distribution, and Wnt signaling coreceptor Ror2 (light blue) are noted in the tongue mesenchyme. B. In a proposed model, mechanisms are suggested for Wnt5a to signal in mesenchyme and epithelium to regulate tongue and papilla development. We suggest that Wnt5a signaling is mediated by Ror2. Wnt5a in the mesenchyme signals via Ror2 locally to support the cell cytoskeleton and motility, and to affect cell proliferation in a stage-specific manner. Wnt5a signals via Ror2 in the epithelium to inhibit Wnt10b canonical Wnt signaling and thereby balance fungiform papilla formation.

Within the mesenchyme, Wnt5a interacting with local Ror2 could enhance migration of fibroblasts (He et al., 2008; Nishita et al., 2006; Pacheco and MacLeod, 2008). In Wnt5a null mutant tongues the short phenotype, with a much reduced free anterior tongue region, and decreased expression of vimentin, suggests a failure of appropriate mesenchymal cell migration. The overall result is part of a constellation of imbalance among molecular regulators that are necessary in temporal and tissue-specific contexts for normal tongue and papilla development.

Interactions with canonical Wnt signaling

It is noteworthy that LiCl added to tongue cultures results in increased fungiform papilla numbers, replicating our previously reported results (Iwatsuki et al., 2007). LiCl is known to activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling as a Gsk3β inhibitor that prevents β-catenin degration (Hedgepeth et al., 1997; Silva et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2011). Importantly, with exogenous LiCl the increase in fungiform papilla number is exacerbated in Wnt5a null mutant tongues, supporting the idea that Wnt5a has a developmental role in suppressing Wnt canonical signaling. Furthermore, with exogenous Wnt5a in cultures of TOPGAL mouse tongues, fungiform papillae and Wnt/β-catenin dependent TOPGAL expression are eliminated. This strongly supports an inhibitory mechanism for mesenchymal Wnt5a activity in suppressing epithelial, canonical Wnt signaling. We have proposed previously that Wnt/β-catenin signaling can activate Shh signaling which would feed back to inhibit canonical Wnt and thereby regulate papilla number (Iwatsuki et al., 2007). By suppressing a Wnt/β-catenin path, Wnt5a would disrupt this balance.

In limb development Wnt5a acts primarily via a noncanonical pathway and inhibits canonical Wnt signaling (Topol et al., 2003). In Wnt5a mutants, canonical Wnt activity and β-catenin protein levels are increased in distal limb. In this tissue, Wnt5a inhibits canonical Wnt signaling via β-catenin degradation, in a GSK-3 independent mechanism. Whereas we do not have data for a specific mechanism for Wnt canonical inhibition via Wnt5a, there are similarities in Wnt5a −/− tongue and limb, for example in distributions of Wnt5a and in reduced mesenchymal cell proliferation.

Summary and Model

This study is the first to show roles for a noncanonical Wnt in tongue, lingual tissue and gustatory papilla developmental regulation. We analyzed Wnt5a signaling in embryonic tongue and taste papillae and demonstrated two broad, separate actions: promoting tongue outgrowth, principally a mesenchymal effect, and balancing/suppressing fungiform papilla formation, principally an epithelial effect. The number of fungiform papillae, which contain taste buds, is crucial for taste function and must be tightly regulated or maintained. Even in a mutation that puts noncanonical signaling at risk (e.g., a Wnt5a mutant) and leads to loss of tongue tissue in a radically foreshortened organ, fungiform papilla number is sustained. Whereas this “crowds” the papillae, the high organ density is tolerated to retain papilla number, and the factors that direct papilla innervation retain their function.

Deletion of canonical Wnt signaling components does not alter tongue size and shape, and canonical Wnt signals promote fungiform papilla formation (Iwastuki et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2007; Okubo et al., 2006). We propose signaling paths where mesenchymal Wnt5a in anterior tongue acts locally in non-canonical Wnt signaling to promote cell motility and tongue outgrowth, and in paracrine signaling via an epithelial receptor to suppress canonical Wnt signaling and regulate fungiform papilla development (Figure 12B).

Supplementary Material

Suppl. Fig. 1. Scanning electron micrograph of E16.5 wild type (WT) mouse tongue to illustrate topography and tongue regions used for measuring length and width. The anterior oral tongue is defined as the region distal to the edge of the intermolar eminence (IE). The posterior oral tongue incorporates the IE, the circumvallate papilla (black arrow), regions between the IE and circumvallate that are free of taste papillae, and fungiform papilla-bearing regions lateral to IE. The circumvallate papilla at the edge of the posterior tongue serves to demarcate the boundary of oral from pharyngeal tongue. The widest extent of the anterior oral tongue was taken as the measure of width.

Suppl. Fig. 2. Scanning electron micrographs (A) and sagittal sections (B) of E11.5 wild type (WT) and mutant (Wnt5a−/−) tongue swellings. A: At E11.5 the tongue swellings have not coalesced into a spatulate structure. Two lateral lingual swellings (LS) are anterior to a third, posterior tuberculum impar swelling (TI). As in later stages of development (Figure 2), the lingual swellings in E11.5 mutant are shorter and wider than in WT. B: Sections through the lateral lingual swellings stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The tongue is demarcated from underlying mandible by a line. A shorter lingual swelling is seen in the mutant compared to WT. However, general cell arrangement in epithelium and mesenchyme is similar, seen at higher magnification. Scale bars apply to WT and mutant paired images.

Suppl. Fig. 3. Cell proliferation in WT and Wnt5a−/− tongue epithelium and mesenchyme, at E13.5 and E16.5. A: Photomicrographs of sagittal tongue sections labeled with BrdU injections to the pregnant dam. Two straight lines mark the region where labeled epithelial cells were counted. Circles at the tongue tip illustrate area in which labeled mesenchymal cells were counted. Scale bar: 250 μm, applies to all images. B: Histograms for counts and density of BrdU labeled cells, in epithelium and in mesenchyme (n = 1 per stage). Numbers of cells per epithelial length does not differ between WT and mutant tongues at E13.5 or E16.5. At E13.5, density of BrdU+ mesenchymal cells in the tongue tip is increased in Wnt5a−/− compared to WT. At E16.5, there is a decreased density in mesenchymal cells in Wnt5a−/− compared to WT.

Suppl. Fig. 4. Scanning electron micrographs of palate and maxilla in WT and Wnt5a−/− embryos. At E13.5, palate shelves are vertical in WT and Wnt5a−/−. At E14.5 and E18.5, WT palate shelves have elevated and fused in the midline but the mutant palate remains open. Arrows point to rugae which develop on the mutant palate even though the shelves do not elevate. Scale bars: 1.0 mm, apply to WT and Wnt5a−/− paired images.

Suppl. Fig. 5. Wild type tongue cultures with high concentration of Wnt5a or long culture period. Scanning electron micrographs of E12.5 + 2 day mouse tongue cultures in standard medium (Std) or with added Wnt5a at 5.0 μg/ml. Tongues cultured in the high Wnt5a concentration are longer than those in standard medium. Histograms at left include data for two tongues in Std or two in Wnt5a medium. Histograms at right present data from four tongues in standard medium and four tongues with added Wnt5a, at 3.0 μg/ml, cultured for three days. Tongues are more narrow and longer with exogenous Wnt5a (*P<0.05; **P<0.01). Scale bars: 100 μm.

Suppl. Fig. 6. Photomicrographs of E14.5 sagittal tongue sections immunoreacted for the Ror2 receptor. Ror2 immunoproduct (green) is intensely distributed in tongue epithelium in WT and Wnt5a−/−, and dispersed label is seen in the mesenchyme. Insets illustrate immunoreactions with omission of the primary antibody. The dotted line in higher power images demarcates the border of epithelium and mesenchyme. Scale bars: 50 μm, 25 μm apply to WT and Wnt5a−/−.

Highlights.

Distinctive roles for Wnt5a in development of tongue size and taste papillae

Wnt5a mutant tongue is severely shortened, with ankyloglossia

Fungiform papilla number, innervation and Shh expression preserved in mutant tongue

In cultures Wnt5a suppresses papilla formation and decreases canonical Wnt signaling