Abstract

Rumination is a risk factor for depressive and anxiety symptoms in adolescents. Previous investigations of the mechanisms linking rumination to internalizing problems have focused primarily on cognitive factors. We investigated whether interpersonal stress generation plays a role in the longitudinal relationship between rumination and internalizing symptoms in young adolescents. Adolescents (Grades 6–8, N =1,065) from an ethnically diverse community completed measures of depressive and anxiety symptoms, perceived friendship quality, and peer victimization at two assessments, 7 months apart. We determined whether rumination predicted increased exposure to peer victimization and whether changes in perceived friendship quality mediated this relationship. We also evaluated whether peer victimization mediated the association between rumination and internalizing symptoms. Adolescents who engaged in high levels of rumination at baseline were more likely to experience overt, relational, and reputational victimization at a subsequent time point 7 months later, controlling for baseline internalizing symptoms and victimization. Increased communication with peers was a significant partial mediator of this association for relational (z =1.98, p =.048) and reputational (z =2.52, p =.024) victimization. Exposure to overt (z = 3.37, p =.014), relational (z =3.67, p <.001), and reputational (z = 3.78, p < .001) victimization fully mediated the association between baseline rumination and increases in internalizing symptoms over the study period. These findings suggest that interpersonal stress generation is a mechanism linking rumination to internalizing problems in adolescents and highlight the importance of targeting interpersonal factors in treatment and preventive interventions for adolescents who engage in rumination.

Rumination is a risk factor for depression and anxiety (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010) that has recently been conceptualized as a core transdiagnostic factor in the emotional disorders (McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011b). Nolen-Hoeksema (1991) defined rumination as a passive pattern of responding to distress in which an individual thinks repetitively about his or her upsetting symptoms and the causes and consequences of those symptoms without initiating active problem solving to alter the factors causing the distress.

Both experimental and observational studies show that this type of rumination is a robust determinant of anxiety and mood pathology in children, adolescents, and adults (Aldao et al., 2010; Rood, Roelofs, Bogels, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2009; Watkins, 2008). Experimental induction of rumination in young adults enhances and prolongs depressed and anxious mood (Blagden & Craske, 1996; McLaughlin, Borkovec, & Sibrava, 2007). Observational studies consistently find that rumination predicts subsequent increases in depressive symptoms in adults (Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, & Fredrickson, 1993; Nolen-Hoeksema, Parker, & Larson, 1994), as well as in children and adolescents (Abela, Brozina, & Haigh, 2002; Broderick & Korteland, 2004; Burwell & Shirk, 2007; Hankin, 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema, Stice, Wade, & Bohon, 2007; J. A. J. Schwartz & Koenig, 1996). Rumination also predicts the onset and maintenance of major depressive episodes in both adults (Just & Alloy, 1997; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Robinson & Alloy, 2008) and adolescents (Abela & Hankin, 2011; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2007). Associations between rumination and a wide range of anxiety symptoms have been reported in adult studies (Clohessy & Ehlers, 1999; Fresco, Frankel, Mennin, Turk, & Heimberg, 2002; Harrington & Blankenship, 2002; Mellings & Alden, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991), and recent evidence suggests that rumination predicts subsequent increases in anxiety symptomatology in adolescents (Hankin, 2008; McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011b).

Previous research has investigated a variety of cognitive and behavioral mechanisms through which rumination may lead to the development of depression and anxiety. In experimental studies of young adults, distressed individuals who complete a rumination induction exhibit greater levels of maladaptive, negative thinking (Lyubomirsky, Caldwell, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998; Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995; Rimes & Watkins, 2005) and less willingness to engage in mood-lifting activities (Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1993) than distressed individuals who engage in distraction. Distressed individuals induced to ruminate also generate less effective solutions to problems (Donaldson & Lam, 2004; Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995; Watkins & Moulds, 2005; Watkins & Baracaia, 2002) and exhibit greater uncertainty and immobilization in the implementation of solutions to problems as compared to individuals who engage in distraction (Lyubomirsky, Kasri, Chang, & Chung, 2006; Ward, Lyubomirsky, Sousa, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003).

Rumination may also contribute to the onset of depression and anxiety through interpersonal mechanisms. Relative to persons who do not frequently engage in rumination, individuals who ruminate tend to be viewed less favorably by others (Schwartz & McCombs, 1995) and to report lower levels of social support (Abela, Vanderbilt, & Rochon, 2004; Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999). It is also plausible that interpersonal stress generation plays a central role in the relationship between rumination and internalizing problems. Interpersonal stress generation is a well-documented phenomenon in major depression. Specifically, children, adolescents, and adults who are depressed have been found to play a role in generating stressful events in their lives, particularly stressors involving interpersonal conflict and discord (Cole, Nolen-Hoeksema, Girgus, & Paul, 2006; Daley et al., 1997; Hammen, 1991, 1992; Rudolph et al., 2000). Interpersonal stress generation does not occur exclusively in youths who are currently depressed, however; stress generation has been observed in the children of depressed mothers, among anxious children, and among typically developing adolescents (Adrian & Hammen, 1993; Rudolph & Hammen, 1999). Interpersonal processes shown to contribute to stress generation include poor interpersonal problem solving, avoidant coping, and excessive reassurance seeking (Davila, Hammen, Burge, Paley, & Daley, 1995; Holahan, Moos, Holahan, Brennan, & Schutte, 2005; Joiner, Wingate, Gencoz, & Gencoz, 2005; Potthoff, Holahan, & Joiner, 1995).

Rumination may serve to initiate and maintain the negative interpersonal processes that lead to stress generation. For example, distressed adults induced to ruminate generate less effective solutions to interpersonal problems and are more hesitant and uncertain about implementing any solutions they do generate (Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995; Ward et al., 2003; Watkins & Baracaia, 2002). Thus, rumination may prolong and worsen interpersonal problems in distressed individuals. Rumination may also influence perceptions of social support and relationship quality. Indeed, individuals who engage in higher levels of rumination perceive less support and more isolation than those who do ruminate (Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999). Perceptions of low social support may drive a variety of negative interpersonal processes like excessive support seeking and reassurance seeking (Joiner, 2000) that may ultimately strain interpersonal relationships and generate stressors and conflict in relationships. Adults who engage in high levels of rumination are more likely to seek support from others following loss and traumatic events, independent of their level of distress (Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). Although such strategies may effectively activate support networks initially, over time these behaviors may increase social conflict and elicit criticism from others, particularly if they are not accompanied by active attempts to resolve distress or alter the causes of one’s distress. As such, engaging in excessive support seeking to ameliorate distress or to improve coping may eventually strain the resources of support networks and generate interpersonal conflict, exacerbating dysphoria and increasing risk for depression and anxiety (Joiner & Metalsky, 1995, 2001). Consistent with this idea, ruminators report experiencing greater friction in their interpersonal relationships than individuals who do not ruminate (Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999). Despite conceptual support for the link between rumination and interpersonal stress generation, we are unaware of previous research that has examined rumination as a predictor of subsequent exposure to interpersonal stressors. Moreover, the interpersonal pathways involved in stress generation have rarely been examined in studies of children or adolescents.

The present study addressed this gap in the literature using data from a large, prospective study of early adolescents. We first examined whether rumination was associated prospectively with exposure to interpersonal stressors. In the seminal studies of stress generation, events involving interpersonal conflict—defined as encounters involving two people characterized by disagreement, negative affect, or relationship dissolution—were used to define episodes of interpersonal stress generation (Davila et al., 1995; Hammen, 1991; Rudolph et al., 2000). We assessed exposure to interpersonal stressors using a measure of peer victimization that assessed several distinct types of interpersonal conflict with peers: overt victimization, or being the target of physical aggression, threats, or verbal aggression (Prinstein, Boergers, & Vernberg, 2001; Vernberg, 1990); relational victimization, in which relationship status is used as the mechanism of aggression through social exclusion and rejection; and reputational victimization, or being the victim of gossip or rumor spreading (Crick & Bigbee, 1998; LaGreca & Harrison, 2005; Prinstein et al., 2001). Peer victimization occurs frequently in adolescent peer relationships and has damaging effects on social and psychological adjustment (Olweus, 1993; Prinstein et al., 2001; Storch, Masia-Warner, Crisp, & Klein, 2005; Vernberg, Abwender, Ewell, & Beery, 1992). Social exclusion, peer rejection, bullying, and being the target of gossip and rumors are some of the primary ways in which tension or conflict is expressed in adolescent relationships, and these interpersonal stressors are strongly related to psychopathology in adolescents (LaGreca & Harrison, 2005; McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler, & Hilt, 2009; Rudolph & Hammen, 1999). Peer victimization experiences are therefore among the most salient manifestations of interpersonal stress for adolescents. We anticipated that adolescents who engaged in higher levels of rumination would be more likely to be rejected and victimized by their peers than adolescents who did not engage in rumination.

We also examined an interpersonal mechanism that might account for the associations between rumination and peer conflict, rejection, and victimization. Specifically, we evaluated whether adolescents with a tendency to ruminate experienced changes in their perceptions of peer support and friendship quality over time and whether these perceptions of relationship support, in turn, mediated the longitudinal associations between rumination and each of the three types of peer victimization assessed in the study. Finally, we determined whether interpersonal stress generation, as indexed by greater exposure to peer victimization, was a mechanism linking rumination to increases in internalizing symptoms. We hypothesized that greater exposure to peer victimization would explain, in part, the longitudinal association between rumination and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

METHOD

Participants

The sample for this study was recruited from the total enrollment of two middle schools (Grades 6–8; age range =11–14) in a small, urban community in central Connecticut. Students in self-contained special education classrooms and technical programs who did not attend school for the majority of the day were excluded. Schools were chosen for the study based on their willingness to participate.

The parents of all eligible children (N =1,567) in the participating middle schools were asked to provide active consent for their children to participate in the study. Parents who did not return written consent forms to the school were contacted by telephone. Twenty-two percent of parents did not return consent forms and could not be reached to obtain consent, and 6% of parents declined to provide consent. All youths provided assent for participation. The overall participation rate in the study at Time 1 was 72%. Of participants who were present at Time 1, 217 (20.4%) did not participate at the Time 2 assessment, largely due to transient student enrollment in this district. Data from the school district indicate that over the 4-year period from 2000 to 2004, 22.7% of students had left the district (Connecticut Department of Education, 2006). Analyses were conducted using the sample of 1,065 participants who were present at the Time 1 assessment, excluding participants who were present at Time 2 but not at Time 1.

The Time 1 sample included 51.2% (n =545) boys and 48.8% (n =520) girls. Participants were evenly distributed across grade level (M age = 12.2, SD =1.0). The race=ethnicity composition of the sample was as follows: 13.2% (n =141) non-Hispanic White, 11.8% (n =126) non-Hispanic Black, 56.9% (n =610) Hispanic=Latino, 2.2% (n =24) Asian=Pacific Islander, 0.2% (n =2) Native American, 0.8% (n =9) Middle Eastern, 9.3% (n =100) Biracial=Multiracial, and 4.2% (n =45) Other racial=ethnic groups. Twenty-seven percent (n =293) of participants reported living in single-parent households. The community in which the participating middle schools reside is relatively low socioeconomic status, with a per capita income of $18,404 (Connecticut Department of Education, 2006, based on data from 2001). School records indicated that 62.3% of students qualified for free or reduced lunch in the 2004–2005 school year. There were no differences across the two schools in demographic variables.

Measures

Rumination

The Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire (CRSQ; Abela et al., 2002) is a 25-item scale that assesses the extent to which children respond to sad feelings with rumination, defined as self-focused thought concerning the causes and consequences of depressed mood, distraction, or problem solving. The measure is modeled after the Response Styles Questionnaire (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) that was developed for adults. For each item, youth are asked to rate how often they respond in that way when they feel sad on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 9 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). The Rumination subscale includes 13 items that are summed to generate a score ranging from 13 to 42. Sample items include “Think about a recent situation wishing it had gone better” and “Think why can’t I handle things better?” The reliability and validity of the CRSQ have been demonstrated in samples of early adolescents (Abela et al., 2002). The CRSQ rumination scale demonstrated good reliability in this study (α =0.86).

Interpersonal stress generation

The Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire (RPEQ; Prinstein et al., 2001) was used to assess exposure to peer victimization experiences and rejection from peers, which are developmentally salient interpersonal stressors for adolescents. The RPEQ was developed from the Peer Experiences Questionnaire (Vernberg, Jacobs, & Hershberger, 1999) and assesses overt, relational, and reputational victimization by peers. The questionnaire includes 18 items that ask participants to rate how often an aggressive behavior was directed toward them in the past year on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (a few times a week). The original and revised measure has demonstrated good test–retest reliability, internal consistency, and convergent validity (Prinstein et al., 2001; Vernberg, Fonagy, & Twemlow, 2000). The RPEQ assesses each of the following forms of victimization: overt, relational, and reputational. Overt victimization captures physical and verbal threats and actual acts of violence (e.g., ”A kid threatened to hurt or beat me up”). Relational victimization includes experiences of social exclusion and peer rejection (“Some kids left me out of an activity or conversation that I really wanted to be included in”), and reputational victimization involves being the target of gossip or rumors (“A kid gossiped about me so that others would not like me”). Scores are obtained by summing the items within each subscale, and a total score is generated by summing all items within each subscale. The RPEQ total victimization scale and each of the subscales demonstrated adequate internal consistency in this sample: total victimization (α =0.88), overt (α =0.78), relational (α =0.79), reputational (α = 0.79).

Perceived peer support

Perceived friendship quality and support from peers were assessed with the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment for Children (IPPA-R; Armsden & Greenberg, 1987; Gullone & Robinson, 2005). The IPPA assesses positive and negative dimensions of attachments to parents and peers and examines a variety of aspects of perceived relationship quality and support (Blain, Thompson, & Whiffen, 1993). Only the peer items were administered in the current study. Respondents indicate how true each item is for them on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never true=almost never true) to 5 (always true=almost always true). This analysis focused specifically on the Peer Communication and Trust subscales, which assess perceptions of the degree and quality of communication and trust in peer relationships. Representative items from the Trust subscale are “My friends understand me,” and “I feel my friends are good friends,” and representative items from the Peer Communication sub-scale include “I like to get my friends’ point of view on things I am concerned about,” and “I can tell my friends about my problems or troubles.” The IPPA has demonstrated good test–retest reliability and convergent validity in previous studies (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987; Gullone & Robinson, 2005). The revised IPPA subscales demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α =0.81–0.91).

Internalizing symptoms

We administered two widely used measures of depression and anxiety symptoms, the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992) and the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997). The CDI is a self-report measure of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. The CDI includes 27 items consisting of three statements (e.g., I am sad once in a while, I am sad many times, I am sad all the time) representing different levels of severity of a specific symptom of depression. The CDI has sound psychometric properties, including internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and discriminant validity (Kovacs, 1992; Reynolds, 1994). The item pertaining to suicidal ideation was removed from the measure at the request of school officials and the human subjects committee. The 26 remaining items were summed to create a total score ranging from 0 to 52. The CDI demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α =.82).

The MASC is a 39-item widely used measure of anxiety in children. The MASC assesses physical symptoms of anxiety, harm avoidance, social anxiety, and separation anxiety and is appropriate for children ages 8 to 19. Each item presents a symptom of anxiety, and participants indicate how true each item is for them on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never true) to 3 (very true). A total score, ranging from 0 to 117, is generated by summing all items. The MASC has high internal consistency and test–retest reliability across 3-month intervals and established convergent and divergent validity (Muris, Merckelbach, Ollendick, King, & Bogie, 2002) and differentiates between anxious children, control children, and children with other types of psychopathology (March, Sullivan, & Parker, 1999). The MASC demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α =.88).

Because rumination has been shown to be a trans-diagnostic factor related to the development of both anxiety and depression in adolescents (McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011b), and in order to reduce the number of analyses in this article, we conducted all analyses using a combined measure of internalizing symptoms (described in more detail in the Data Analysis section).

Procedure

Participants completed study questionnaires during their homeroom period All questionnaires used in the present analyses were administered initially at Time 1 (November 2005) and 7 months later at Time 2 (June 2006). This time frame was chosen to allow the maximum time between assessments to observe changes in internalizing symptoms while also ensuring that all assessments occurred within the same academic year to avoid high attrition. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses and the voluntary nature of their participation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Yale University.

Data Analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS 6.0 software (Arbuckle, 2005) was used to perform all analyses. SEM presents numerous advantages over simple linear regression, including the ability to model error variance explicitly and account for covariation among predictor variables in longitudinal mediation analysis (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). Analyses were conducted using the full information maximum likelihood estimation method, which estimates means and intercepts to handle missing data. Multiply indicated latent variables were created for rumination, peer victimization, and internalizing symptoms using parcels of items from the relevant scales. Parcels were created using the domain representative approach, which accounts for the multidimensionality of these outcomes (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002), such that each parcel included items from each of the subscales of the relevant measures. In SEM, the use of parcels to model constructs as latent factors, as opposed to an observed variable representing a total scale score, confers a number of psychometric advantages including greater reliability, reduction of error variance, and increased efficiency (Kishton & Wadaman, 1994; Little et al., 2002). Dimensions of perceived peer support were modeled as observed variables because the small number of items included in the revised IPPA Peer Communication and Trust subscales did not permit the construction of multiple parcels of items.

After testing the measurement models for all constructs, the analyses proceeded as follows. We first examined whether rumination was associated longitudinally with peer victimization, over and above the effect of Time 1 internalizing symptoms, and whether changes in perceived peer support mediated this relationship. Separate mediation analyses were conducted to examine the role of perceived peer support as a mediator of the longitudinal associations between rumination and each of the three types of peer victimization—overt, relational, and reputational—using standard tests of statistical mediation (Baron & Kenny, 1986; MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). Specifically, we examined (a) the association between Time 1 rumination and each of the three types of peer victimization at Time 2, controlling for Time 1 victimization and internalizing symptoms; (b) the association between Time 1 rumination and Time 2 perceived peer support, controlling for Time 1 perceived support and internalizing symptoms; (c) the association between Time 2 perceived peer support and each of the three types of peer victimization at Time 2, controlling for Time 1 perceived support, peer victimization, and internalizing symptoms; and (d) the attenuation in the association between rumination at Time 1 and peer victimization at Time 2, controlling for Time 1 peer victimization, after accounting for perceived peer support at Time 1 and Time 2 and internalizing symptoms at Time 1.

Our next set of analyses examined the role of interpersonal stress generation—as indexed by our measures of peer victimization—as a mechanism linking rumination to increases in internalizing symptoms. We first examined the association between Time 1 rumination and internalizing symptoms at Time 2, controlling for Time 1 symptoms. Associations between the putative mediators and rumination were examined in previously described analyses. Therefore, our next step was to examine the associations between Time 2 peer victimization and Time 2 internalizing symptoms, controlling for Time 1 symptoms and peer victimization. This analysis examined the association of residualized change in each of the three types of peer victimization in predicting residualized change in internalizing symptoms. In the final mediation models, we examined the attenuation in the association between rumination at Time 1 and internalizing symptoms at Time 2 after each type of peer victimization at Time 2 was added to the model, controlling for Time 1 symptoms and peer victimization.

The significance of all mediators was evaluated using the product of coefficients method. Sobel’s standard error approximation was used to test the significance of the intervening variable effect (Sobel, 1982). The product of coefficients approach is associated with low bias and Type 1 error rate, accurate standard errors, and adequate power to detect small effects (MacKinnon et al., 2002). Finally, we examined the role of gender as a moderating variable, given the established gender differences in rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2009) and in stress exposure (Rudolph & Hammen, 1999). Multigroup analyses were conducted to examine whether the process of mediation was moderated by gender. Each of the mediation paths was constrained to be equal for male and female participants, and the difference in model fit was examined using a chi-square test. Only adolescent participants who were present at Time 1 (N =1,065) were included in analyses.

RESULTS

Attrition

Analyses were first conducted to determine whether participants who did not complete both assessments differed from those who completed both the Time 1 and Time 2 assessments. Univariate analyses of variance were conducted for continuous outcomes with attrition as a between-subjects factor. Chi-square analyses were performed for dichotomous outcomes. Participants who completed the Time 1 but not Time 2 assessment were more likely to be female, χ2(1) =6.85, p <.01, but did not differ in grade level, in race=ethnicity, or being from a single parent household (ps >.10). Participants who did not complete the Time 2 assessment did not differ from participants who completed both assessments on Time 1 rumination, peer victimization, or internalizing symptoms (all ps >.10).

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays the mean and standard deviation of all measures at each time point. Table 2 provides the zero-order correlations among rumination, peer victimization, peer support seeking, and internalizing symptoms. As expected, rumination was positively associated with peer victimization and internalizing symptoms, which were positively associated with one another.

TABLE 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Rumination, Peer Victimization, Perceived Peer Support, and Internalizing Symptoms

| Measure | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | ||

| CRSQ Rumination | 10.94 | 7.65 |

| RPEQ Total Victimization | 21.97 | 8.52 |

| RPEQ Overt Victimization | 7.07 | 3.24 |

| RPEQ Relational Victimization | 9.21 | 3.56 |

| RPEQ Reputation Victimization | 5.73 | 2.84 |

| IPPA Peer Communication | 21.92 | 5.89 |

| IPPA Peer Trust | 29.89 | 7.44 |

| CDI Depressive Symptoms | 9.67 | 6.44 |

| MASC Anxiety Symptoms | 40.20 | 15.39 |

| Time 2 | ||

| CRSQ Rumination | 10.18 | 8.07 |

| RPEQ Total Victimization | 21.97 | 9.67 |

| RPEQ Overt Victimization | 7.07 | 3.23 |

| RPEQ Relational Victimization | 9.17 | 3.82 |

| RPEQ Reputation Victimization | 5.77 | 2.79 |

| IPPA Peer Communication | 19.41 | 7.31 |

| IPPA Peer Trust | 33.11 | 10.50 |

| CDI Depressive Symptoms | 10.63 | 8.15 |

| MASC Anxiety Symptoms | 34.80 | 18.05 |

Note: CRSQ =Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire; RPEQ =Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire; IPPA =Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment; CDI =Children’s Depression Inventory; MASC =Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children.

TABLE 2.

Correlations Between Rumination, Peer Victimization, Perceived Peer Support, and Internalizing Symptoms

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CRSQ T1 Rumination | — | |||||||||||||||

| 2. RPEQ T1 Overt Victimization | .28** | — | ||||||||||||||

| 3. RPEQ T1 Relational Victimization | .37** | .67** | ||||||||||||||

| 4. RPEQ T1 Reputational Victimization | .29** | .66** | .63** | — | ||||||||||||

| 5. IPPA T1 Peer Communication | .17** | .03 | .01 | .08* | — | |||||||||||

| 6. IPPA T1 Peer Trust | −.02 | −.11** | −.07* | −.03 | .76* | — | ||||||||||

| 7. CDI T1 Depressive Symptoms | .42** | .31** | .32** | .27** | −.17** | −.30** | — | |||||||||

| 8. MASC T1 Anxiety Symptoms | .55** | .30** | .34** | .26** | .14** | −.02 | .28** | — | ||||||||

| 9. CRSQ T2 Rumination | .48** | .24** | .28** | .25** | .12** | −.11** | .35** | .41** | — | |||||||

| 10. RPEQ T2 Overt Victimization | .21** | .41** | .34** | .32** | .02 | −.07 | .18** | .33** | .33** | — | ||||||

| 11. RPEQ T2 Relational Victimization | .29** | .32** | .39** | .29** | .09* | −.01 | .19** | .26** | .41** | .71** | — | |||||

| 12. RPEQ T2 Reputational Victimization | .25** | .28** | .31** | .35** | .09* | −.02 | .20** | .16** | .38** | .72** | .72** | — | ||||

| 13. IPPA T2 Peer Communication | .19** | .01 | .03 | .03 | .47** | .30** | −.07* | .23** | .30* | .12** | .16** | .20** | — | |||

| 14. IPPA T2 Peer Trust | −.01 | −.10* | −.08* | −.07 | .39** | .39** | −.22** | .08* | .04 | −.03 | −.02 | .03 | .79** | — | ||

| 15. CDI T2 Depressive Symptoms | .23** | .25** | .21** | .22** | −.07* | −.26** | .58** | .73** | .44** | .23** | .22** | .21** | −.13** | −.31** | — | |

| 16. MASC T2 Anxiety Symptoms | .35** | .25** | .25** | .22** | .23** | −.08* | .24** | .53** | .67** | .29** | .37** | .28** | .22** | .06* | .33** | — |

Note: CRSQ =Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire; RPEQ =Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire; IPPA =Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment; CDI =Children’s Depression Inventory; MASC =Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children.

p <.05.

p <.01.

Measurement Models

The measurement models for rumination, peer victimization, and internalizing symptoms were each constructed from parcels of items created using the domain representative approach (Little et al., 2002). The rumination measurement model was created from four parcels and fit the data well, χ2(2) =4.23, p =.121, comparative fit index (CFI) =.99, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) =.03, 90% confidence interval (CI) [.00, .07]. The internalizing symptoms model also was created from four parcels, each of which included items from the CDI and each of the subscales of the MASC. This model fit the data well, χ2(2) = 4.58, p =.01, CFI =.99, RMSEA =.05, 90% CI [.02, .08]. Finally, we created measurement models for each of the three types of peer victimization. Each model was constructed using three parcels, given the smaller number of items in each of the subscales. These models fit the data adequately: overt, χ2(1) =30.3, p <.001, CFI =.96, RMSEA =.15, 90% CI [.10, .19]; relational, χ2(1) =1.76, p = .184, CFI =.99, RMSEA =.02, 90% CI [.00, .08]; reputational, χ2(1) =6.35, p =.012, CFI =.99, RMSEA =.06, 90% CI [.02, .11].

Rumination and Interpersonal Stress Generation

Rumination at Time 1 was associated with each of the three types of peer victimization at Time 2, controlling for Time 1 peer victimization and internalizing symptoms (overt, β =.14, p <.001; relational, β =.19, p <.001; reputational, β =.21, p <.001).

Perceived Peer Support as a Mediator of Interpersonal Stress Generation

We next evaluated whether changes in perceived social support mediated the longitudinal association between rumination and subsequent victimization by peers. We examined overt, relational, and reputational victimization separately. In the first step of the mediation model, rumination at Time 1 was associated with greater perceived communication with peers at Time 2 (β =.09, p =.011), controlling for Time 1 perceived support and internalizing symptoms. Rumination was not associated with peer trust (β =−.03, p =.344). As such, we examined only peer communication in subsequent steps of the mediation model. In Step 2 of the model, peer communication at Time 2 was associated with greater levels of overt (β =.14, p <.001), relational (β =.16, p <.001) and reputational (β =.22, p <.001) victimization by peers, controlling for Time 1 peer communication, victimization, and internalizing symptoms.

Final mediation models accounted for the covariation between rumination, internalizing symptoms, and peer victimization at Time 1. In the mediation model for overt victimization, rumination at Time 1 remained a significant predictor of Time 2 victimization after Time 2 support seeking was added to the model, controlling for Time 1 victimization, support seeking, and internalizing symptoms (β =.14, p =.041). Sobel’s z test indicated that the indirect effect of rumination on overt victimization through support seeking was not significant (z =1.76, p =.079). This model fit the data well, χ2(96) =188.1, p <.001, CFI =.99, RMSEA =.03, 90% CI [.02, .03].

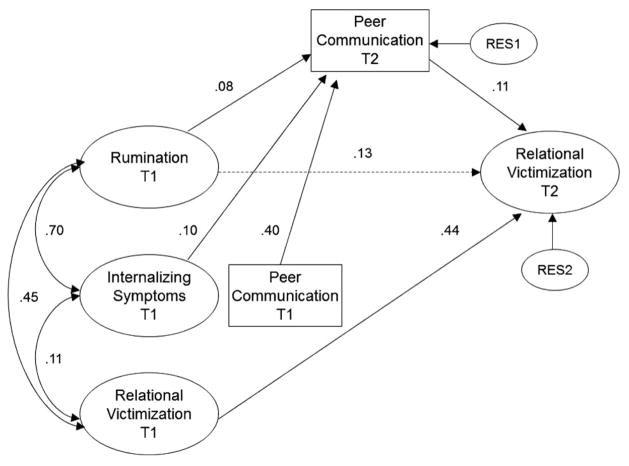

In the mediation model for relational victimization, rumination at Time 1 was no longer a significant predictor of Time 2 victimization after Time 2 support seeking was added to the model, controlling for Time 1 victimization, support seeking, and internalizing symptoms (β = .13, p =.058; see Figure 1). Sobel’s z test indicated a significant indirect effect of rumination on relational victimization through increased support seeking (z =1.98, p =.048). The model also fit the data well, χ2(96) =214.4, p <.001, CFI =.98, RMSEA =.03, 90% CI [.03, .04].

FIGURE 1.

Final mediation model for peer communication as a mediator of the association between rumination and relational victimization. Note: Numbers represent standardized path coefficients (β). All paths shown are significant (p <.05), except those drawn with broken lines. All constructs in circles were modeled as latent variables; constructs in squares were modeled as observed variables. Due to space constraints, indicator variables are not displayed.

Finally, in the mediation model for reputational victimization, rumination at Time 1 remained a significant predictor of Time 2 victimization after Time 2 support seeking was added to the model, controlling for Time 1 victimization, support seeking, and internalizing symptoms (β =.18, p =.010). Sobel’s z test indicated that the indirect effect of rumination on reputational victimization through support seeking was significant (z =2.25, p =.024). This model fit the data well, χ2(96) =207.0, p <.001, CFI =.98, RMSEA =.03, 90% CI [.02, .04]. In summary, support seeking was a significant partial mediator of the relationship between rumination and changes in overt, relational, and reputational victimization. Support seeking explained 29.9% of the association between rumination and relational victimization, 9.3% of the association between rumination and reputational victimization, and an even smaller proportion of the association between rumination and overt victimization.

Interpersonal Stress Generation as a Mechanism Linking Rumination to Internalizing Symptoms

In the next stage of analysis, we examined the role of interpersonal stress generation as a mechanism linking rumination to increases in internalizing symptoms. We first examined the longitudinal association between rumination and internalizing symptoms in our sample. Time 1 rumination was associated with internalizing symptoms at Time 2, controlling for Time 1 symptoms (β =.10, p =.003). Next, we evaluated whether increases in peer victimization mediated this association. We conducted separate mediation analyses examining overt, relational, and reputational victimization. As shown in the previous analysis, rumination was associated longitudinally with each of the three types of peer victimization. Increased exposure to peer victimization, in turn, was associated with increases in internalizing symptoms. Time 2 overt (β =.29, p <.001), relational (β =.35, p <.001), and reputational (β =.27, p <.001) victimization were associated with internalizing symptoms at Time 2, controlling for Time 1 victimization and internalizing symptoms.

Final mediation models accounted for the covariation between rumination, internalizing symptoms, and peer victimization at Time 1. In the mediation model for overt victimization, Time 1 rumination was no longer associated with Time 2 internalizing symptoms after adding Time 2 overt victimization to the model, controlling for Time 1 overt victimization and internalizing symptoms (β =−.07, p =.581). Sobel’s z test indicated a significant indirect effect of rumination on internalizing symptoms through overt victimization (z =3.37, p <.001). This model fit the data well, χ2(127) = 259.5, p <.001, CFI =.99, RMSEA =.03, 90% CI [.02, .03]. A similar pattern was observed for both relational and reputational victimization. In separate mediation models that controlled for Time 1 internalizing symptoms and exposure to victimization, Time 1 rumination was no longer a significant predictor of Time 2 internalizing symptoms after Time 2 relational (β =−.19, p =.773) and reputational (β =−.15, p =.257) victimization was added to the model. In both cases, Sobel’s z test indicated a significant indirect effect of rumination on internalizing symptoms through peer victimization (relational, z =3.67, p <.001; reputational, z =3.78, p < .001. Both of these models fit the data well: relational, χ2(127) =266.8, p <.001, CFI =.99, RMSEA = .03, 90% CI [.02, .03], and reputational, χ2(127) = 271.0, p <.001, CFI =.99, RMSEA =.03, 90% CI [.02, .03]. In sum, overt, relational, and reputational victimization each mediated the relationship between rumination and internalizing symptoms.

We next examined each path of the mediation model separately in predicting symptoms of depression and anxiety to determine whether the effects differed across different types of internalizing symptoms. The pattern of results was identical in predicting anxiety symptoms. The only difference in associations that emerged in the models predicting depression is that the association between Time 1 rumination and depressive symptoms at Time 2 did not reach the statistical significance after controlling for Time 1 symptoms.

Gender Effects

We examined whether the role of perceived support as a mediator of the relationship between rumination and subsequent relational and reputational victimization was modified by gender. We did not examine overt victimization because perceived peer support did not mediate the association between rumination and overt victimization. When the mediation paths of interest (see Figure 1) were constrained to equivalence across male and female participants, the model fit was significantly different for both relational, χ2(3) =10.47, p =.015, and reputational, χ2(3) =12.36, p =.006, victimization. Examination of the structural paths revealed that rumination was more strongly associated with peer communication for girls (β =.27) than for boys (β =.09).

We also examined whether the role of peer victimization as a mediator of the relationship between rumination and subsequent internalizing symptoms was modified by gender. We examined the mediation models for overt, relational, and reputational victimization separately. When the mediation paths of interest (see Figure 1) were constrained to equivalence across male and female participants, the model fit did not significantly worsen for overt, χ2(3) =6.37, p =.095; relational, χ2(3) =5.59, p =.133; or reputational, χ2(3) =1.71, p =.635, victimization, indicating that the process and strength of mediation was consistent across gender.

DISCUSSION

One mechanism by which rumination may contribute to internalizing symptoms is by generating interpersonal stress and conflict. Indeed, our results indicate that rumination is associated prospectively with a range of peer victimization experiences among early adolescents independent of their level of internalizing symptoms. Because victimization and rejection by peers are common manifestations of interpersonal conflict among adolescents, these findings implicate rumination as a determinant of peer-related interpersonal stress generation during this developmental period. Our results also highlight the role of increased peer communication as a mechanism underlying interpersonal stress generation in adolescents. Specifically, we found that young adolescents who engaged in high levels of rumination reported increases in the degree and quality of communication with their peers. These increases in perceived communication quality, however, were associated with increases over time in overt, relational, and reputational victimization by peers and partially mediated the association between rumination and exposure to peer victimization. These results suggest that rumination is associated with interpersonal stress generation and that increased engagement in communication with peers, potentially as a means of eliciting support, plays a role in generating these interpersonal problems. In turn, greater exposure to all three types of victimization mediated the longitudinal relationship between rumination and internalizing symptoms. Thus, although young ruminators are reaching out to peer networks for support, our findings suggest that their communication strategies for eliciting that support are associated with negative interpersonal consequences that increase their likelihood of being victimized by their peers, thereby heightening risk for symptoms of depression and anxiety.

We provide novel evidence for the role of rumination in the generation of interpersonal stress, a phenomenon that is common among depressed children and adolescents but that also occurs in the absence of major depression (Cole et al., 2006; Daley et al., 1997; Rudolph & Hammen, 1999). Although we anticipated that rumination would predict perceptions of decreased friendship quality and peer support, our results suggest that high levels of rumination are associated longitudinally with increases in peer communication—particularly for girls—and that greater engagement in communication with peers predicts exposure to peer victimization. Why might increases in peer communication result in the generation of interpersonal stressors for adolescents? It is possible that these increases in peer communication reflect engagement in corumination. Although corumination is associated with greater closeness and friendship quality (Rose, Carlson, & Walker, 2007), recent evidence suggests that it also predicts interpersonal stress generation (Hankin, Stone, & Wright, 2010), indicating that corumination may be a mechanism underlying the generation of stress and conflict in interpersonal relationships among adolescents who engage in high levels of rumination. Engagement in corumination may also contribute to elevated risk for the development of internalizing symptoms in adolescents who ruminate, a possibility that is discussed further below. Another possibility is that adolescents who engage in rumination are engaging in behaviors that are aimed at eliciting support from others. This result is consistent with previous findings in adults indicating that ruminators are more likely than nonruminators to seek support from others, often because they have concerns they want to share and discuss (Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999). Ruminators also have more difficulty solving problems in their lives (Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995) and thus may turn to others for advice and help. Seeking social support is generally considered to be an adaptive coping strategy (Cohen & Wills, 1985). However, the elevations we observed in peer communication, potentially reflecting greater support seeking, among adolescents with a tendency to ruminate did not appear to have the desired outcome; instead, these behaviors actually increased the likelihood of being victimized by peers, which further contributed to increased levels of internalizing symptoms among adolescents who engaged in rumination.

Youths who ruminate may behave in several ways that engender hostility from others (Abela et al., 2004), interfering with their efforts to elicit social support. Rumination is associated with neediness, dependency, and excessive concern about relationships (Nolen-Hoeksema & Jackson, 2001; Spasojevic & Alloy, 2001). These characteristics may lead ruminators to engage in excessive reassurance seeking (Joiner, 2000), a behavior that is associated with social rejection (Joiner, Alfano, & Metalsky, 1992; Joiner & Metalsky, 1995). Rumination also may breed animosity and negative affect that further undermines interpersonal effectiveness among high ruminators. Individuals induced to ruminate about an interpersonal transgression exhibit greater hostility and aggressiveness toward others (Bushman, Bonacci, Pedersen, Vasquez, & Miller, 2005; Collins & Bell, 1997; McCullough, Bellah, Kilpatrick, & Johnson, 2001; McCullough et al., 1998), which may further impair their ability to elicit social support. Together, these previous studies suggest that the adolescents in our study who engaged in high levels of rumination may have been behaving in a clingy and needy, yet simultaneously hostile, fashion toward the peers to whom they were reaching out for support. Unfortunately, such behaviors set the stage for potential victimization, particularly relational and reputational victimization. The current study did not measure each of these facets of interpersonal behavior directly, however, indicating the importance of examining the extent to which interpersonal pathways involving excessive support and reassurance seeking, clingy and needy behaviors, as well as hostility underlie the relationship between rumination and stress generation in future research. It is important to note that rumination was associated with increases in peer communication more strongly for girls than for boys in this study, highlighting the importance of identifying additional mechanisms linking rumination to interpersonal conflict and stress generation in male adolescents.

Even in the absence of needy and hostile behaviors, rumination may elicit frustration from typically supportive others. In an observational study, Schwartz-Mette and Rose (2009) found that ruminative adolescents engaged in more conversational self-focus with peers, defined as chronically redirecting a conversation back to their own concerns while ignoring their friend’s needs and concerns. In one example, a girl with a tendency to ruminate interrupted her friend who was disclosing concerns about her body image to begin talking about a problem she was having with her boyfriend, and continued to dominate the conversation with this topic for several minutes. After inviting her friend to talk about the friend’s romances, the girl interrupted after the friend had uttered only a single sentence with “Yeah, me and [my ex-boyfriend] were like that when we first started going out … “ and continued to talk about her romantic problems in a way that shut out the friend from voicing her concerns or feelings. If ruminators engage in these sorts of interactions chronically, their peers may become frustrated and hostile to the point of complaining about the ruminative adolescent to others or acting in relationally aggressive ways.

Our findings suggest that the interpersonal stressors generated by these behaviors are a core mechanism linking rumination to the development of adolescent internalizing symptoms for both boys and girls. The increased exposure to peer victimization experienced by adolescents with a tendency to ruminate mediated the relationship between rumination and subsequent increases in internalizing symptoms in the young adolescents in this study. These findings indicate that, in addition to impairing problem solving and propagating negative thinking (Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995), rumination contributes to interpersonal victimization and rejection, which further contributes to the development of depression and anxiety. Peer victimization is a highly salient stressor for adolescents and is associated strongly with the later onset of internalizing problems (LaGreca & Harrison, 2005; McLaughlin et al., 2009; Prinstein & Aikins, 2004; Prinstein et al., 2001; Storch et al., 2005; Vernberg et al., 1992). Being victimized by peers may also give youths more to ruminate about, creating a self-perpetuating cycle between rumination and peer victimization. Indeed, in previous work with this sample we found that peer victimization was associated with increased engagement in rumination, along with several other maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (McLaughlin et al., 2009). Engagement in behaviors that engender peer rejection and victimization is thus a particularly pernicious consequence of rumination in adolescence.

Rumination also may contribute to internalizing symptoms in adolescents by fueling engagement in corumination. The longitudinal increases in peer communication observed among adolescents with high levels of rumination may reflect engagement in corumination, in addition to support seeking from peers. Although corumination is associated with increased closeness and positive friendship quality among adolescents, engagement in corumination predicts later increases in symptoms of anxiety and depression as well as the onset of depressive disorders (Rose et al., 2007; Stone, Hankin, Gibb, & Abela, 2011), suggesting that at least some of the observed association between rumination and internalizing symptoms might be explained by corumination. An interesting possibility is that rumination leads to increased communication and support seeking from friends, which then generates corumination among certain dyads of adolescents, fueling the development of depression and anxiety symptoms. Together, these findings indicate that peer communication, support seeking, and corumination—each of which are interpersonal processes associated with friendship quality and salubrious interpersonal outcomes (e.g., Rose et al., 2007)—may ultimately lead to interpersonal conflict and internalizing symptomatology among adolescents who ruminate. Although we cannot parse these pathways in our data, because we did not administer measures of corumination or support seeking, it is likely that corumination is an interpersonal process that explains at least some of the association between rumination and later internalizing symptoms. Disentangling the extent to which these different interpersonal pathways are involved in the relationship between rumination and internalizing symptoms is an important goal for future research.

A final possibility is that adolescents who engage in high levels of rumination are at risk for developing beliefs that aggressive behavior is acceptable or justified following experiences of victimization and rejection by peers. Previous research on peer relations in shy children suggests that exposure to victimization may result in beliefs that aggression is legitimate and warranted, contributing to later increases in internalizing symptoms (Dill, Vernberg, Fonagy, Twemlow, & Gamm, 2004). Self-blaming attributions are also common in adolescents following victimization experiences, and these types of attributions exacerbate psychological distress (Graham & Juvonen, 1998). Adolescents who engage in high levels of rumination may be more likely to believe that aggressive behavior is justified or to make self-blaming attributions after victimization experiences than adolescents who do not ruminate. For example, an adolescent who is repetitively thinking about the causes of her distress after being excluded from a party she hoped to attend may come to the conclusion that she is not a fun friend or not interesting enough to be invited, and that the social exclusion was therefore deserved. These beliefs may promulgate behaviors such as support and reassurance seeking and corumination that strain the peer relationships of adolescents with high levels of rumination and further exacerbate their risk for psychopathology (Dill et al., 2004).

Rumination has only recently become a specific target in cognitive-behavioral interventions to prevent and treat internalizing problems (Watkins et al., 2007). Our findings suggest that interventions targeting rumination in adolescents may need to focus specifically on their interpersonal behaviors, teaching them to interact with others in ways that are less likely to lead to peer rejection, victimization, and conflict (McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011a). For example, traditional functional analysis techniques could be employed to identify situations that are associated with engagement in conversational self-focus and to determine the functional significance of these behaviors, followed by the implementation of techniques aimed at teaching the adolescent to notice this behavior when it is happening and redirect the conversation back to his or her partner. These skills could be further reinforced with role-plays in group therapy interventions. Similar techniques could be used to identify situations that make adolescents feel insecure or needy and that elicit reassurance seeking behavior. Behavioral techniques could then be used to replace these behaviors with adaptive strategies that are more likely to successfully garner social support; alternatively, behavioral activation techniques might be employed to identify activities the adolescent can engage in independently that promote positive mood.

Study findings should be interpreted in light of several notable limitations. The greatest limitation of this study was its reliance on self-report questionnaires. The self-reports of peer victimization and support seeking have good convergent validity (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987; Prinstein et al., 2001) but reflect perceived interpersonal behaviors rather than observed behaviors. Replication of our findings in studies that utilize teacher-report and=or peer-nomination methods for assessing peer victimization is an important goal for future research. Nevertheless, self-report assessment can capture victimization experiences that are unobserved by peers and teachers and remains the most common method for assessing peer victimization in the literature (LaGreca & Harrison, 2005; Prinstein et al., 2001; Vernberg, 1990). Similarly, our measures of internalizing symptoms, the CDI and MASC, have good psychometric properties (Kovacs, 1992; Muris et al., 2002; Reynolds, 1994) but rely on youth’s ability and willingness to report symptoms and do not provide information about whether youth meet diagnostic criteria for depression or anxiety disorders. It will be important for future studies to examine the relationships reported here using clinician-assessed measures of internalizing symptoms and disorders.

Second, our measure of interpersonal stress generation focused specifically on victimization, social exclusion, and rejection by peers. Although these experiences are developmentally salient manifestations of interpersonal conflict among adolescents, our assessment of interpersonal stress generation was not comprehensive. Most critically, we did not assess the extent to which rumination was associated with the generation of interpersonal conflict in family relationships, an important aspect of stress generation that has relevance for the development of internalizing psychopathology in adolescents (Rudolph & Hammen, 1999). Examination of the relationship between rumination and other forms of interpersonal stress generation represents an important goal for future research. Third, our study did not include measures of the specific interpersonal behaviors that might explain the relationship between increased peer communication and stress generation, including peer support and reassurance seeking as well as corumination. Although the IPPA communication subscale includes items that reflect peer support seeking (e.g., “I like to get my friends’ point of view on things I am concerned about”) as well as corumination (e.g., “My friends encourage me to talk about my difficulties”), the measure was not designed to assess these constructs directly. A fourth limitation is that our data only allowed us to test mediation models using two time points. A preferable approach is to use multiwave data to establish that the exposure predicts changes in the mediator that precede changes in the outcome (Cole & Maxwell, 2003; Maxwell & Cole, 2007). To more rigorously test the conceptual model examined in this study, a prospective study with four waves of data would be needed to examine whether rumination predicts subsequent changes in peer quality, changes in peer quality predict interpersonal stress generation, and finally whether stress generation predicts subsequent increases in internalizing symptoms. Future research utilizing such an approach is needed to confirm the relationships reported in this study. Finally, although we view the ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic diversity of our sample as a strength, it is important to note that most studies of rumination and adolescent internalizing psychopathology have been conducted in samples comprised predominantly of White, middle-class participants (Abela, Aydin, & Auerbach, 2007; Burwell & Shirk, 2007; J. A. J. Schwartz & Koenig, 1996). It will therefore be important to replicate the current findings in samples to ensure generalizability of the findings.

We provide novel evidence for the role of rumination in generating interpersonal stress among early adolescents. Adolescents with a tendency to ruminate report increased communication with their peers over time, and these behaviors contribute to their risk of being victimized and rejected. It is important to note that our results suggest that one mechanism by which rumination exacerbates and prolongs distress among adolescents is by generating stressful interpersonal experiences with peers. Rumination appears to trigger a self-perpetuating cycle of interpersonal behaviors that increase risk of victimization and rejection by peers that subsequently lead to greater distress, highlighting the particularly detrimental effects of rumination during this developmental period. Given the importance of peer relationships for adolescents’ well-being, interventions targeting adolescents who ruminate should incorporate techniques aimed specifically at improving interpersonal skills as a strategy for preventing the onset of depression and anxiety.

Contributor Information

Katie A. McLaughlin, Department of Psychiatry, Children’s Hospital Boston

Susan Nolen-Hoeksema, Department of Psychology, Yale University.

References

- Abela JR, Aydin CM, Auerbach RP. Responses to depression in children: Reconceptualizing the relation among response styles. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:913–927. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JR, Brozina K, Haigh EP. An examination of the response styles theory of depression in third- and sixth-grade children: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:515–527. doi: 10.1023/a:1019873015594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JR, Hankin BL. Rumination as a vulnerability factor to depression during the transition from early to middle adolescence: A multiwave longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:259–271. doi: 10.1037/a0022796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JR, Vanderbilt E, Rochon A. A test of the integration of the response styles and social support theories of depression in third and sixth grade children. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2004;23:653–674. [Google Scholar]

- Adrian C, Hammen C. Stress exposure and stress generation in children of depressed mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:354–359. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 6.0 user’s guide. Chicago, IL: SPSS; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16:427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagden JC, Craske MG. Effects of active and passive rumination and distraction: A pilot replication with anxious mood. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1996;10:243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Blain MD, Thompson JM, Whiffen VE. Attachment and perceived social support in late adolescence: The interaction between working models of self and others. Journal of Adolescent Researchi. 1993;8:226–241. [Google Scholar]

- Broderick PC, Korteland C. A prospective study of rumination and depression in early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;9:383–394. [Google Scholar]

- Burwell RA, Shirk SR. Subtypes of rumination in adolescence: associations between brooding, reflection, depressive symptoms, and coping. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:56–65. doi: 10.1080/15374410709336568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, Bonacci AM, Pedersen WC, Vasquez EA, Miller N. Chewing on it can chew you up: Rumination and displaced aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:969–983. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clohessy S, Ehlers A. PTSD symptoms, responses to intrusive memories, and coping in ambulance service workers. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;38:251–265. doi: 10.1348/014466599162836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS, Paul G. Stress exposure and stress generation in child and adolescent depression: A latent trait-state-error approach to longitudinal studies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:40–51. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins K, Bell R. Personality and aggression: the Dissipation-Rumination scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 1997;5:751–755. [Google Scholar]

- Connecticut Department of Education. Strategic school profile 2005–2006: New Britain public schools. Hartford, CT: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Bigbee MA. Relational and overt forms of peer victimization: A multiinformant approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:337–347. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley SE, Hammen C, Burge D, Davila J, Paley B, Lindberg N, Herzberg DS. Predictors of the generation of episodic stress: A longitudinal study of late adolescent women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:251–259. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Hammen C, Burge D, Paley B, Daley SE. Poor interpersonal problem solving as a mechanism of stress generation in depression among adolescent women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:592–600. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill EJ, Vernberg EM, Fonagy P, Twemlow SW, Gamm BK. Negative affect in victimized children: The roles of social withdrawal, peer rejection, and attitudes toward bullying. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:159–173. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019768.31348.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson C, Lam D. Rumination, mood and social problem solving in major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:1309–1318. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704001904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresco DM, Frankel AN, Mennin DS, Turk CL, Heimberg RG. Distinct and overlapping features of rumination and worry: The relationship of cognitive production to negative affective states. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26:179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Juvonen J. Self-blame and peer victimization in middle school: An attributional analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:587–599. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullone E, Robinson K. The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment–Revised (IPPA–R) for Children: A psychometric investigation. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2005;12:67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. The generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Life events and depression: The plot thickens. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1992;2:179–193. doi: 10.1007/BF00940835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Rumination and depression in adolescence: Investigating symptom specificity in a multiwave prospective study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:701–713. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Stone LB, Wright PA. Corumination, interpersonal strses generation, and internalizing symptoms: Accumulating effects and transactional influences in a multiwave study of adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:217–235. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington JA, Blankenship V. Ruminative thoughts and their relation to depression and anxiety. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32:465–485. [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Brennan PL, Schutte KK. Stress generation, avoidance coping, and depressive symptoms: A 10-year model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:658–666. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE., Jr Depression’s vicious scree: Self-propagating processes in depression chronicity. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000;7:203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Alfano MS, Metalsky GI. When depression breeds contempt: Reassurance seeking, self-esteem, and rejection of depressed college students by their roommates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:165–173. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Metalsky GI. A prospective test of an integrative interpersonal theory of depression: A naturalistic study of college roommates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:778–788. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Metalsky GI. Excessive reassurance seeking: Delineating a risk factor involved in the development of depressive symptoms. Psychological Science. 2001;12:371–378. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Wingate LR, Gencoz T, Gencoz F. Stress generation in depression: Three studies on its resilience, possible mechanism, and symptom specificity. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24:236–253. [Google Scholar]

- Just N, Alloy LB. The response styles theory of depression: Tests and an extension of the theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:221–229. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishton JM, Wadaman KF. Unidimensional versus domain representative parceling of questionnaire items: An empirical example. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1994;54:757–765. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- LaGreca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Examining the question, weighing the evidence. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Caldwell ND, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of ruminative and distracting responses to depressed mood on retrieval of autobiographical memories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:166–177. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Kasri F, Chang O, Chung I. Ruminative response styles and delay of seeking diagnosis for breast cancer symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:276–304. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Self-perpetuating properties of dysphoric rumination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:339–349. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of self-focused rumination on negative thinking and interpersonal problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:176–190. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JDA, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Sullivan K, Parker JDA. Test–retest reliability of the multidimensional anxiety scale for children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1999;13:349–358. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(99)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Bellah CG, Kilpatrick SD, Johnson JL. Vengefulness: Relationships with forgiveness, rumination, well-being, and the big five. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:601–610. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Rachal KC, Sandage SJ, Worthington EL, Jr, Brown SW, Hight TL. Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships: II. Theoretical elaboration and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1586–1603. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.6.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Borkovec TD, Sibrava NJ. The effect of worry and rumination on affect states and cognitive activity. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:23–38. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hilt LM. Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking peer victimization to the development of internalizing symptoms among youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0015760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in promoting and preventing depression in adolescent girls. In: Strauman T, Garber J, editors. Depression in adolescent girls. New York, NY: Guilford; 2011a. pp. 112–129. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in deprssion and anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011b;49:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellings T, Alden LE. Cognitive processes in social anxiety: The effects of self-focus, rumination and anticipatory processing. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:243–257. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Merckelbach H, Ollendick T, King N, Bogie N. Three traditional and three new childhood anxiety questionnaires: Their reliability and validity in a normal adolescent sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:753–772. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effect on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:569–582. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety=depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:504–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Davis CG. Thanks for sharing that”: Ruminators and their social support networks. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:801–814. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt LM. The emergence of gender differences in depression in adolescence. In: Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt LM, editors. Handbook of depression in adolescents. New York: Routledge; 2009. pp. 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Jackson B. Mediators of the gender difference in rumination. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2001;25:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:115–121. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J, Fredrickson BL. Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:20–28. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Parker LE, Larson J. Ruminative coping with depressed mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:92–104. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, Bohon C. Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:198–207. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Potthoff JG, Holahan CJ, Joiner TE., Jr Reassurance seeking, stress generation, and depressive symptoms: An integrative model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:664–670. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.4.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Aikins JW. Cognitive mediators of the longitudinal association between peer rejection and adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:147–158. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019767.55592.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Vernberg EM. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:479–491. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Assessment of depression in children and adolescents by self-report measures. In: Reynolds WM, Johnston HF, editors. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. New York, NY: Plenum; 1994. pp. 209–234. [Google Scholar]

- Rimes K, Watkins E. The effects of self-focused rumination on global negative self-judgements in depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:1673–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MS, Alloy LB. Negative cognitive styles and stress-reactive rumination interact to predict depression: A prospective study. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;27:275–291. [Google Scholar]

- Rood L, Roelofs J, Bogels SM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. The influence of emotion-focused rumination and distraction on depressive symptoms in non-clinical youth: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:607–616. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose A, Carlson W, Walker E. Prospective associations of corumination with friendship and emotional adjustment: Considering the socio-emotional trade-offs of corumination. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1019–1031. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C. Age and gender as determinants of stress exposure, generation, and reactions in youngsters: A transactional perspective. Child Development. 1999;70:660–677. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D, Lindberg N, Herzberg DS, Daley SE. Toward an interpersonal life-stress model of depression: The developmental context of stress generation. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:215–234. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400002066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JAJ, Koenig LJ. Response styles and negative affect among adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1996;20:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JL, McCombs TA. Perceptions of coping responses exhibited in depressed males and females. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 1995;10:849–860. [Google Scholar]