Abstract

Vasculogenesis, the assembly of the first vascular network, is an intriguing developmental process that yields the first functional organ system of the embryo. In addition to being a fundamental part of embryonic development, vasculogenic processes also have medical importance. To explain the organizational principles behind vascular patterning, we must understand how morphogenesis of tissue level structures can be controlled through cell behavior patterns that, in turn, are determined by biochemical signal transduction processes. Mathematical analyses and computer simulations can help conceptualize how to bridge organizational levels and thus help in evaluating hypotheses regarding the formation of vascular networks. Here we discuss the ideas that have been proposed to explain the formation of the first vascular pattern: cell motility guided by extracellular matrix alignment (contact guidance), chemotaxis guided by paracrine and autocrine morphogens, and sprouting guided by cell-cell contacts.

1. Introduction

Vasculogenesis is the assembly process of the first embryonic blood vessel network before the onset of circulation. Besides its importance in normal development, certain vasculogenic processes are also relevant in various pathophysiologies. Vascular endothelial cell progenitors exist in the adult and may become bloodborne, enter extravascular tissues, and promote de novo vessel formation (Zammaretti and Zisch, 2005; Rumpold et al., 2004). For that reason, endothelial progenitors, mobilized in situ or transplanted, are a major target of therapeutic vascularization approaches to prevent ischemic disease and control endothelial injury. Moreover, endothelial progenitors represent potential targets for strategies seeking to block tumor growth, and are requisite components for the construction of engineered tissues (Wu et al., 2004). While the advance of molecular and imaging techniques revealed several aspects of the vessel assembly process, its guiding principles remained unsettled. The aim of this review is to discuss the ideas that have been proposed to explain important aspects of the vasculogenic process.

2. Vasculogenesis in avian embryos

Vasculogenesis is the formation of a primary vascular pattern from mesodermally-derived precursors (angioblasts). In avian and mammalian embryos, well before the onset of circulation, hundreds of essentially identical vascular endothelial cells create a polygonal network, the primary vascular plexus (Risau and Flamme, 1995; Drake and Fleming, 2000). Here we briefly review vasculogenesis in avian embryos. Avians are often the model organism of choice to study vascular morphogenesis, due to the transparency and quasi two dimensional body plan of the embryo, and because of the ease with which embryos can be cultured and imaged ex ovo. Furthermore, avians are warm blooded animals with a four chambered heart, and their vasculogenic process was found to be very similar to that of mouse embryos (Drake and Fleming, 2000).

Endothelial cells differentiate both from solitary primordial cells within the mesoderm (area pellucida) and as clusters, components of blood islands within the extraembryonic area opaca (Reagan, 1915; Sabin, 1920). Committed angioblasts display a random spatial distribution within the mesoderm (Drake et al., 1997). Well before the onset of circulation, differentiated angioblasts assemble the primary vascular plexus within a simple, thin sheet-like extracellular matrix environment situated between the endoderm and the splanchnic mesoderm (Risau and Flamme, 1995). Each link in this polygonal network is a cord consisting of 3–10 endothelial cells (Drake et al., 1997).

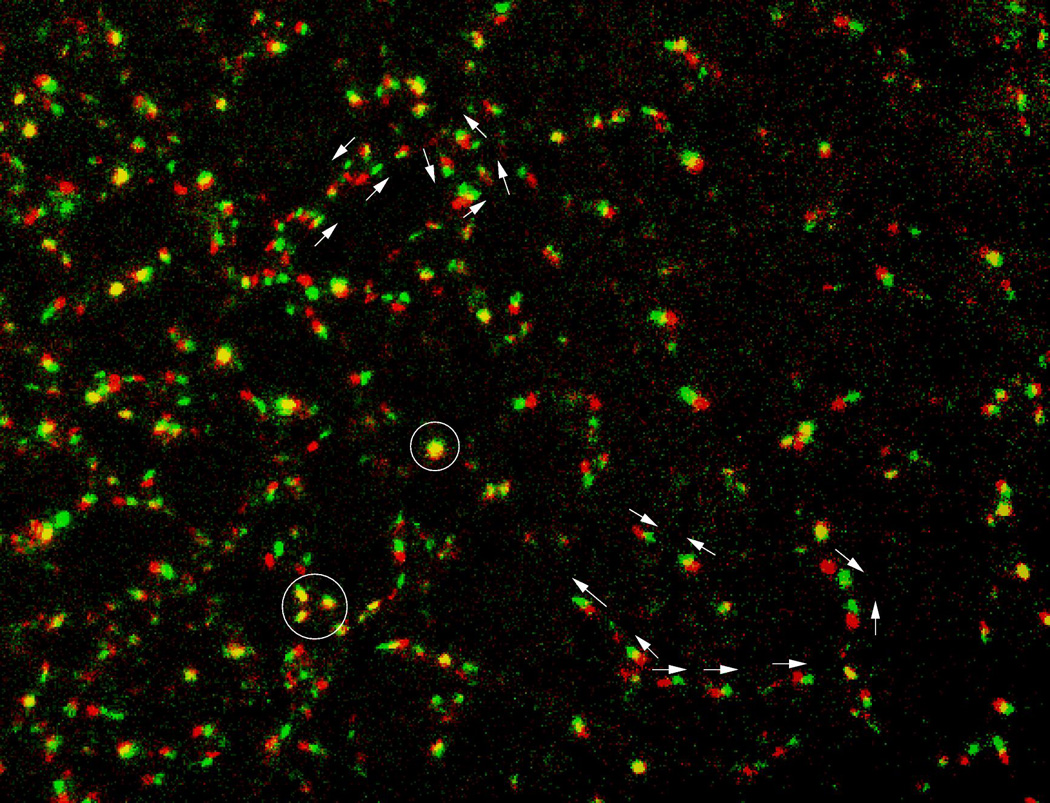

Microscopic recordings of avian vasculogenesis revealed that the primary vascular plexus is created by multicellular sprouts (Rupp et al., 2004; Sato et al., 2010). These sprouts can extend hundreds of micrometers, and may contain several endothelial cells (Fig. 1). This type of protrusive behavior is reminiscent of angiogenic sprouting, a process thought to be characteristic of later vascular development. The forming polygonal network is a dynamic structure. Large-scale tissue movements can redistribute and reshape the vessel network, as seen especially well during the development of the heart (Aleksandrova et al., 2012). Furthermore, new sprouts can appear and existing ones can retract (Rupp et al., 2004). The motility of endothelial cells continues even after the onset of circulation (Sato et al., 2010). Cell chains moving in opposite directions at the same vascular segment are frequently observed, as well as cells switching movement directionality. Furthermore, after the onset of blood flow, endothelial cells comprising the major arteries, such as the dorsal aortae and the vitelline arteries, move collectively towards the heart (Sato et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

Dynamics within vasculogenic sprouts, after subtracting tissue movements, are visualized in a transgenic Tg(tie1:H2B-eYFP) quail embryo. Two consecutive frames, separated by 8 minutes, are shown – the first as red, the second as green. Motion direction of a few selected nuclei are marked by arrows. Movement activity is inhomogeneous: some nuclei do not move (appear as yellow and marked by circles), while most cells move in chains. Movement directions are highly variable: even in the same vascular segment cells are seen moving in opposite directions. After Sato et al., (2010).

3. Endothelial cell motility

The models discussed below make various assumptions on the motility of endothelial cells. The pioneering work of Stokes et al., (1991) revealed that the motility of individual endothelial cells can be well approximated as a persistent random walk (for a review and limits of this description, see e.g., Selmeczi et al., (2005)). For a short period of time, cells move with a sustained speed along a straight line. In contrast, the motion is random (diffusive) if investigated during a long enough time frame (Fig. 2). The speed of the individual cells varies with the culture conditions (such as the type of ECM and growth factors present), and was found to be in the range of 10 – 50 mm/h (Stokes et al., 1991; Kouvroukoglou et al., 2000; Szabo et al., 2010). The persistence time, the time scale separating the linear and diffusive regimes of the persistent random walk, was reported in the range of 0.6 – 3h.

Figure 2.

Random walks with various persistence time. Left: Trajectories of persistent random walks, generated by the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process. Each walk starts at the origin, and the parameters used ensure the same speed (the same average displacement during a time unit) for each walk. Walks with longer persistence time (T) contain extended straight runs. Right: The mean (end-to-end) displacement as a function of elapsed time is an often used statistical measure to characterize random walks. For persistent walks the displacement is initially proportional to the time elapsed, indicating a steady forward movement. For longer times, the displacement will be proportional to the square root of time indicating diffusive behavior. The two regimes appear as lines with slopes of 1 and 1/2 on a double logarithmic plot (dashed lines).

A key characteristic of endothelial cells is their motility response to growth factors, and in particular to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In cultured endothelial cells, VEGF induces cell motility (Yoshida et al., 1996; Yancopoulos et al., 2000) and a chemotactic response (Waltenberger et al., 1994; Cao et al., 1996). Chemotactic response is often described as a drift in the random motility in a direction parallel with the growth factor gradient (Alt, 1980). For a given concentration gradient, the chemotactic index compares the magnitude of the drift motion to the speed associated with the persistent random motion. Best characterized is the chemotactic response of microvessel endothelial cells to acidic fibroblast growth factor (aFGF), where the chemotactic index was estimated as 1.5, thus chemotactic directed motion dominated over random motility (Stokes et al., 1991). More recent studies using microfluidic chambers indicated that a VEGF gradient of approximately 20 mg/ml is needed to elucidate directional migration of cells (Chen et al., 2007; Shamloo et al., 2008). To put this value in perspective, 40–100 mg/ml is the estimated bulk concentration of VEGF needed to saturate cell surface VEGF receptors in vitro (Chen et al., 2007). Thus, under optimal conditions, endothelial cells could respond to distant VEGF sources, even to a source that is a few millimeters away.

Endothelial cell behavior is strongly influenced by the composition, structure, and mechanical properties of the ECM microenvironment (Ingber and Folkman, 1989; Korff and Augustin, 1999; Davis et al., 2002; Stupack and Cheresh, 2002). In particular, collagen density can control vessel density (vessels per area) and vessel size (cross sectional area) (Critser et al., 2010). The coordinated migration and proliferation of multiple ECs to form stable sprouts are enhanced at intermediate collagen densities of 1.2 – 1.9 mg/ml, (Shamloo and Heilshorn, 2010). In addition to the ECM environment’s ability to modulate sprouting activity, endothelial cells actively follow micro-tracks (or channels) within the ECM environment (Bayless and Davis, 2004; Stratman et al., 2009). The ECM may also modulate the availability of growth factors by sequestering them. In particular, fibronectin was shown to control the availability of transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) (Fontana et al., 2005; Leiss et al., 2008) and VEGF (Wijelath et al., 2002), in some cases acting in a synergistic manner with heparan sulfate (Stenzel et al., 2011).

As Fig. 3 demonstrates, endothelial cells also exhibit a capacity for coordinated (collective) migration. In monolayer cultures, transient cell chains move together as groups, and velocity correlations extend over several cell diameters (Szabo et al., 2010). A recent high-throughput study of the genes involved in endothelial sheet migration (Vitorino and Meyer, 2008) identified clusters of genes that have prominent and specific effects on various aspects of motility, such as its activity (speed), its coordination with adjacent cells, or a less understood directional migration response into substrate areas previously scrapped free of endothelial cells (Vitorino and Meyer, 2008). Thus, from a modeling perspective, this latter study suggests a modular control of endothelial cell motility – distinct “circuits” responsible for setting the intensity of migratory activity, its directionality, and coordination with adjacent cells. A special type of cell-cell interaction, whereby a temporary lateral inhibition of motility exists between adjacent endothelial cells, was recently suggested to be operational within angiogenic sprouts (Jakobsson et al., 2010). This process is mediated through delta and notch cell surface receptors, and thought to be responsible for restricting the invasive phenotype to a few cells of the sprout (Bentley et al., 2009).

Figure 3.

Collective motility of endothelial cells, in vivo and in vitro. Left: Cells consisting the intima of the dorsal aortae move upstream: towards the heart, against the circulation. Endothelial cells are visualized within a 14-somite transgenic Tg(tie1:H2B-eYFP) quail embryo. Movement is indicated by a moving projection of 4 frames, in which past positions are dimmer and the actual position is brighter. Colors indicate dorsal-ventral position: purple is more ventral and blue is more dorsal. The layers colored purple and blue are separated by 60 µm. Cells in the ventral cylinder surface (purple) move more medially than cells in the dorsal surface (blue) do, creating helical cell trajectories. After Sato et al., (2010). Right: Cell movement within a bovine aortic endtothelial cell (BAEC) monolayer is visualized through cell trajectories superimposed on a phase-contrast image. Trajectories depict movements during one hour, red-to-green colors indicate progressively later trajectory segments. Adjacent BAEC streams moving in opposite directions are separated by white lines, vortices are denoted by asterisks. After Szabo et al., (2010).

4. Vasculogenesis: Pre-patterned or self-organized?

Conventional models of vasculogenesis often assume that endothelial cells, like neural growth cones, migrate to pre- and well-defined positions following extracellular guidance cues or chemoattractants (Ambler et al., 2001; Cleaver and Krieg 1998; Poole and Coffin, 1989). The best documented example of such a process is angiogenesis within the retina. In the retina, the intricate structure of glial cell processes and the associated ECM, rich in VEGF, were shown to guide endothelial cells and organize the vasculature into a characteristic pattern (Gerhardt et al., 2003; Uemura et al., 2006). Vasculogenesis in fish, where major vessels assemble directly (i.e., without forming an intermediate vascular plexus) also seems to be guided by a genetic pre-pattern, as specific vascular malformations are correlated with genetic defects (Weinstein, 1999).

However, the capacity of endothelial cells to form a polygonal pattern is also demonstrated in various in vitro systems, where the presence of a genetic (or environmental) pre-pattern is either not possible or highly unlikely. The mouse allantois, when explanted, forms a vascular network very similar to the primary vascular pattern of the avian embryo – instead of a pair of umbilical vessels (LaRue et al., 2003; Perryn et al., 2008). Similarly, a vascular network emerges when endothelial cells are placed in three dimensional collagen gels (Montesano and Orci, 1985; Davis et al., 2000). Thus, endothelial cells are clearly capable of self-assembling a network, and we argue that this procedure occurs during early vasculogenesis in amniotes. Moreover, various cells, distinct from fully differentiated endothelial cells, are also able to assemble into vascular-like tubes. Best characterized are highly malignant melanomas in which tumor cells are assembling into tubes to secure a blood supply (Hendrix et al., 2003). Several cell types that do not form tubes, still exhibit linear clusters and multicellular sprouts in culture (Szabo et al., 2007; Szabo et al., 2008). During the last twenty years a number of hypotheses have been proposed to explain this self-organizing aspect of vasculogenesis, which is the focus of this review. Each hypothesis is proposed in the form of a computational model, as currently our only approach to understanding collective phenomena involves the use of quantitative models.

5. Models of motile cells

Just as a useful map is much simpler than the complex territory it represents, quantitative models represent cells in a radically minimalistic approach. At two extremes of simplification, cells are either represented as active Brownian particles (i.e., particles performing a persistent random walk) or individual cells are not resolved at all; instead, a continuous density field approximates the number of cells within a unit area. As the motility of individual cells is often well described as a persistent diffusion (Fig. 2), the motion of the model particles are governed by the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process, the simplest stochastic differential equation yielding persistent random walks. In the continuum models, the cell density distribution changes in time, governed by partial differential equations reflecting the assumptions made on cellular behavior. Thus, random motility of the cells is included as a diffusive process, or chemotaxis results in a convective drift term. The two levels of description may be bridged by the mathematical apparatus of stochastic differential equations, establishing the correspondence between the “microscopic” parameters such as speed and persistence time to “macroscopic” values, such as the diffusion coefficient (Alt, 1980; Lauffenburger and Horwitz 1996; Maheshwari and Lauffenburger 1998; Alber et al., 2006).

While mathematically accessible, the particle or partial differential equation models may be inconvenient to model vasculogenesis: as vascular sprouts are only a few cells wide, a smooth and continuous density field may not be adequate to represent them. The particle models in turn are not well-suited to describe cell-cell interactions, as cell shape and cell adjacency is not resolved. Thus, a third class of models is also commonly used to investigate hypotheses on vascular patterning. These models, like the cellular Potts model (CPM, (Izaguirre et al., 2004)) and its grid-free version, the Subcellular element model (ScEM, (Newman 2005)), represent individual cells as “fluid” droplets, a model choice motivated by the demonstrated non-Newtonian fluid-like behavior of simple cell aggregates (Forgacs et al., 1998). In these models the spreading area (and perimeter) of the objects that represents cells is restricted by an implemented surface tension. The main advantage of the droplet (CPM/ScEM) approach is that cell shape is explicitly represented; thus, the simulation has the potential to describe dynamics in which controlled cell shape plays an important role (Zajac et al., 2003). Spontaneous, persistent cell motility may be introduced in these models by assuming a positive feedback between cell polarity and cell displacements (Szabo et al., 2010). Thus, the model assumes that cell protrusions are more likely at the front of the cell. In turn, the leading edge is stabilized by its continuous advance, a rule that reflects empirical findings such as the contribution of actin polymerization to increased PI3K activity (Srinivasan et al., 2003; Dawes and Edelstein-Keshet, 2007). As model simulations demonstrate, such a mechanism, together with steric constraints resulted by limited cell compressibility, can well reproduce the observed spontaneous streaming behavior in endothelial monolayers (Szabo et al., 2010) or the increased persistence of invading cells in an ECM environment (Szabo et al., 2012).

6. Multicellular models of vasculogenesis

6.1. Contact guidance

The ability to reorganize the ECM is well documented for tissue explants or cell aggregates embedded within an ECM gel. As revealed by the early experiments of Harris and Stoplak (1982) and studied in more detail recently (Sawhney and Howard 2002), cell traction creates aligned ECM bundles radiating from a cell aggregate. Even individual cells can reorganize and align collagen fibers (Guido and Tranquillo, 1993). The developing oriented ECM structure can, in turn, guide cell migration (Vernon et al., 1995; Korff and Augustin, 1999), in a manner similar to collagen gels oriented by magnetic fields (Guido and Tranquillo 1993; Barocas et al., 1998; Girton et al., 1999; Morin and Tranquillo, 2011). Combining these observations, an early model of vasculogenesis proposed that angioblasts first segregate into compact clusters and engage the surrounding ECM fibers (Vernon et al., 1995). As a result of traction forces, ECM bundles develop, which in turn later route the trajectory of motile primordial endothelial cells between clusters (Drake et al., 1997; Manoussaki et al., 1996; Vernon et al., 1995).

A mathematical model describing this system usually includes a visco-elastic equation of motion for the ECM substrate (Manoussaki et al., 1996; Namy et al., 2004). Thus, the ECM is driven by mechanical stresses within. These stresses reflect a mechanical balance between cell-exerted contractile forces and the (visco-) elastic deformations of the ECM material. Traction force generation is assumed to be proportional to the local cell density for low cell densities. Cell density, in turn, is determined by cell movements - either by the passive convective movements of the ECM, or by active cell motility. The latter is represented as a random diffusion process, modulated by the state of the surrounding ECM. In particular, contact guidance along oriented ECM filaments is modeled as an anisotropic diffusion, with greater diffusivity in directions parallel to the principal stretch strain.

Models representing cell-ECM assemblies were analyzed and studied by computer simulations (Murray et al., 1983; Barocas and Tranquillo, 1997; Namy et al., 2004). These studies revealed a patterning mechanism in which a random initial inhomogeneity in cell density results in pattern coarsening: increasingly large cell free areas develop in a process similar to the dynamics of foams (Manoussaki et al., 1996). This theory thus offers a reasonable explanation for pattern formation that takes place when endothelial cells are cultured on matrigel, an often utilized in vitro model of vascular assembly. Network assembly on Matrigel surfaces indeed requires subconfluent cell seeding densities (thus, a confluent monolayer will not form a network) and the main patterning mechanism involves progressive elimination of small cell-free areas. As the above model suggests, this type of pattern formation is expected to occur within cultures of a wide variety of cells, if those cells exert traction forces, and ECM alignment modulates their motility, i.e., they are contact guided. Indeed, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and cells of the murine Leydig cell line TM3 formed networks on basement membrane matrix in much the same fashion (Vernon et al., 1992). When compared with the in vivo observations, the lack of sprouting and any obvious ECM bundles make this patterning mechanism unlikely for primary vasculogenesis.

More recent modeling studies of contact guided patterning treat the ECM with a phenomenological local orientation variable instead of its mechanical state, a choice that gives greater flexibility to represent ECM reorganization by the cells (Painter 2009); Mente et al., 2011). In these models, a positive feedback between the direction of active cell movement and ECM orientation can channel cells into well-defined growing sprouts (Fig. 4). Moreover, oriented adhesion substrates can increase directional persistence of cells when active cell motility is modeled by postulating a feedback between cell displacements and cell polarity (Szabo et al., 2012). While such models are very promising to describe multicellular sprouts in an inhomogeneous ECM environment, their relevance to embryonic vasculogenesis has not yet been established. In particular, as the ECM environment of the early endothelial cells is rather dense at the scale of the cells (Czirok et al., 2006), the existence or lack of ECM filaments to follow does not restrict the potential moves of endothelial cells.

Figure 4.

Network formation in a model utilizing a feedback between contact guidance and ECM orientation. Left: cell density, middle and right: cell and ECM orientation (lines) together with the extent of orientation orientation (gray scale), respectively. Cells become organized into networks of long chains, underlain by pathways of aligned ECM. The mean length of the linear segments is substantially greater than the persistence length of the cells. Image from Painter (2009).

6.2. Guidance by external VEGF gradient

As blood vessels invade a targeted tissue during physiological or pathological angiogenesis, several models focus on the chemotactic guidance of angiogenic sprouts. Since vasculogenesis also utilizes vascular sprouts, insights gained in angiogenesis models could be highly relevant for vasculogenesis as well. Early modeling attempts described the process as a random branching process, where each branch tip followed chemotactic cues, very similar to a single-cell stochastic dynamics (Stokes and Lauffenburger, 1991; Anderson and Chaplain, 1998). More recent studies aim to resolve cell dynamics within the sprouts, or explore VEGF dynamics within the microenvironment of the sprouts.

The combinatorial complexity of biological components is indeed daunting: growth factors, their receptors and co-receptors, the extracellular matrix and its degradation through various matrix metalloproteases, as well as the array of possible cell-cell interactions can all substantially influence the sprouting process (Liu et al., 2011). As an example, recent simulations revealed that the secreted form of VEGFR1, produced by endothelial cells, can enhance VEGF gradients at the sprout tips (Hashambhoy et al., 2011). Another potentially important factor is the specialization of cells within the sprouts. Recent experimental evidence suggests that during angiogenic sprouting the leading tip cells have a different intracellular signaling activity than the remaining (often termed “stalk”) cells (Gerhardt et al., 2003). Tip cells are thought to be more motile, invasive, and responsive to chemotactic signals. Invoking a lateral inhibition mechanism, tip cells can temporarily restrict adjacent cells in the more inactive stalk state (Bentley et al., 2009; Jakobsson et al., 2010).

Multi-scale simulations of sprout extension can couple the VEGF dynamics at the cellular scale with tissue-level models of VEGF sources. In this approach, vascular sprouts are treated as stochastic units (Liu et al., 2011): sprouts invade into the tissue led by a tip cell that follows VEGF gradients. Stalk cells, in turn, are assumed to elongate and proliferate. Branching occurs, at a randomly chosen angle, with a specified probability after a designated time threshold has elapsed at either a stalk or tip cell. Thus, while these simulations provide interesting insight into the functional role of angiogenic sprouting within a tissue, they do not yet offer a model for a self-organized sprout – a model that would generate branching and collective cell motility within the sprout using assumptions only at the molecular (signaling) or cellular level.

Theoretical considerations suggest that stalk cells cannot be passively dragged by a motile tip cell: arguably this process is inconsistent with widely accepted models of cell-cell adhesion (Szabo and Czirok, 2010). In particular, cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion has been repeatedly shown to be analogous to surface tension of immiscible liquid droplets (Foty et al., 1996; Forgacs et al., 1998; Beysens et al., 2000; Foty and Steinberg, 2005; Hegedus et al., 2006), and has been modeled accordingly in theoretical studies (Glazier and Graner, 1993; Izaguirre et al., 2004; Newman 2005)). Surface tension-stabilized structures are, however, prone to the Plateau-Rayleigh instability: a liquid jet with a circular cross-section should break up into drops if its length exceeds its circumference (de Gennes et al., 2003; Hutson et al., 2008). Due to this instability, a sprout pulled by a leader cell and held together by surface tension-like cell-cell adhesion should also break up. Therefore, the presence of leader cells and cell-cell adhesion alone cannot fully account for multicellular sprouting activity (Szabo and Czirok, 2010). One proposed solution, somewhat incompatible with the strict tip/stalk phenotype differentiation, is the assumption that all cells are driven by an external growth factor gradient, and as Fig. 5 demonstrates, branching occurs due to inhomogeneities within the ECM (Bauer et al., 2009).

Figure 5.

A simulated sprout within a VEGF gradient and an inhomogeneous ECM environment. In this simulation high and low VEGF concentrations were maintained at the right and left side of the domain, respectively. The resulting concentration gradient guided the cells to the right. The ECM acted both as a barrier to migration and as an adhesion surface. The tip cell (T) was assumed to be the most sensitive to the chemotactic gradient. Image from Bauer et al., (2009).

At this moment the direct applicability of VEGF-guided sprouting to vasculogenesis or to the problem of self-organized multicellular sprouting is not clear. During the formation of the primary plexus, a VEGF prepattern, similar to the one in the retina, has not been demonstrated. Furthermore, while stalk cells are supposedly less active than tip cells in angiogenesis, they are quite motile during vasculogenesis in avian embryos (Fig. 1). Time lapse recordings of endothelial cells revealed cell chains moving in opposite directions along the same vascular segment (Sato et al., 2010), a behavior incompatible with models operating with deterministic external guidance, like chemotaxis towards a VEGF gradient. Allantois explants, an in vitro model of primary vasculogenesis, also reveal vigorous cell displacements within the sprout, on a scale comparable to the sprout length (Perryn et al., 2008). In particular, expanding sprouts recruit cells from the aggregate. The newly recruited cells move along and may overtake, “leapfrog”, the cells comprising the sprout.

6.3. Autocrine chemotaxis

Endothelial cell movements guided by autocrine chemotactic signaling was proposed as a potential mechanism for pattern emergence during vasculogenesis (Gamba et al., 2003; Serini et al., 2003). The mechanism relies on the secretion of a diffusing chemotactic morphogen, for which VEGF (or a particular VEGF isoform) is often assumed to be a likely candidate. While an autocrine chemoattractant is expeced to result in cell aggregation (Keller and Segel 1970), further assumptions can steer the system towards branching patterns (Fig. 6). Of particular importance is the finite compressibility of the cells, i.e., cells are assumed to resist being compressed into an arbitrary small area; instead, cells behave as if an effective pressure is developed within the aggregate (Merks et al., 2008). If the diffusion length (mean distance a secreted morphogen molecule moves before degradation or immobilization) is small enough, then the strongest gradients develop at the surface of the aggregate. Thus, the aggregate surface may become unstable; if random fluctuations (for example) move a cell away from the aggregate, it will sense a weaker gradient, and hence it will have a lower tendency to return to the aggregate. Moreover, the pressure of the compressed cells continues to push the cell outwards. By exploring this system with computer simulations, it has been shown that finite cell size, elongated cells, and increased chemotactic sensitivity at free cell surfaces all facilitate the sprouting process (Merks et al., 2006, 2008).

Figure 6.

Sprouting behavior in a model that utilizes an autocrine chemoattractant. In this simulation all cells secrete a diffusing morphogen, possibly VEGF165, and cells can respond to this factor on their free boundaries. The initial spherical aggregate becomes unstable due to the compression of cells within the aggregate and the short diffusion length of the morphogen. Image from Merks et al., (2008).

The suggested chemoattractant, VEGF165, however, is unlikely to fit the model assumptions during embryonic vasculogenesis. VEGF165 is expressed throughout the embryo except in angioblasts or early endothelial cells (Flamme et al., 1995; Poole et al., 2001). Thus, even if early endothelial cells secrete some small amount of VEGF, the concentration of the autocrine VEGF molecules is likely to be too small compared to the amount already present in the ECM microenvironment. Similar objections can be raised when this explanation is applied to the in vitro 3D collagen invasion assays. In such experiments endothelial sprouts readily elongate even in the presence of relatively large concentrations of exogenous VEGF in the culture medium (Vernon and Sage 1999; Koh et al., 2008). Thus, while autocrine VEGF signaling may indeed contribute to the patterning of vascular sprouts (Serini et al., 2003), it is unlikely to be a required mechanism for sprouting activity.

Still, a mathematically very similar patterning process can result from a related and more plausible hypothetical mechanism. If a secreted proteolytic agent increases the availability or “activates” ECM-bound VEGF, then a local gradient (of the bioavailable VEGF) may be produced in the microenvironment of an endothelial cell aggregate. Similarly, the binding of paracrine growth factors to angioblast-produced ECM can drive patterning by creating spatially-restricted guidance cues required for directed cell migration (Köhn-Luque et al., 2011). Unfortunately, it is difficult to visualize morphogen gradients in vitro and more so in vivo. Thus, experimental validation of the autocrine signaling mechanism remains an interesting challenge.

6.4. Preferential attraction to sprout cells

If stalk cells within an expanding sprout move actively – as we argue is the case during vasculogenesis – then a guidance mechanism is needed to recruit such cells into the expanding sprouts. That is, cells must “prefer” to be adjacent to other stalk cells rather than remain in a cell aggregate.

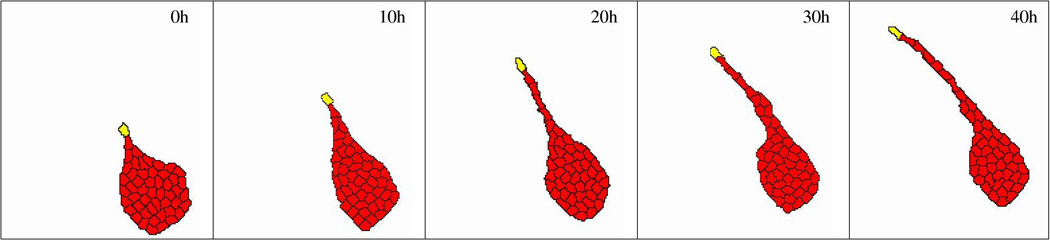

The assumption of a “preferential adhesion mechanism” with persistently moving tip cells is sufficient to obtain expanding sprouts in computer simulations (Fig. 7), (Szabo and Czirok 2010). Furthermore, multicellular sprouting behavior is exhibited not only by endothelial, but by glioma, muscle or liver epithelial cells even when cultured on a rigid, two dimensional surface (Medico et al., 1996; Szabo et al., 2007, 2008). Thus, a rather generic mechanism was suggested that relies on cell-cell guidance – the preferential attraction to elongated cells (Szabo et al., 2007). Such a mechanism is sufficient to stabilize sprouts: as a sprout elongates, the constituent cells become increasingly attractive migration targets. The influx of additional cells (if available) helps to restore normal cell shape and stabilize the sprout. As speculated, the molecular mechanism for sensing elongated cells may involve micromechanical differences in the cytoskeleton of elongated and well spread cells, or even alterations in the available contact surface between the cells if elongated cells are “thicker”.

Figure 7.

Computational model of multicellular sprout elongation. A leader cell (yellow) is assumed to move randomly with a persistent polarity, remaining cells (red) are assumed to prefer adhesion to elongated cells instead of to well spread cells. This preference helps cells to leave the initial aggregate and enter the sprout. After Szabo and Czirok (2010).

7. Perspectives

Since the vascular system is the first functional organ system of the embryo, a detailed understanding of the principles of its organization could shed light on a long standing problem of developmental biology: How can tissue level structures be controlled through cell behavior patterns that, in turn, are determined by biochemical signal transduction processes? The complexity of the problem is both combinatorial and conceptional: several possible interactions exist between system components and multiple organizational levels are involved in the process. The formulation of hypotheses into mathematical representations yields “dynamical cartoons” that are useful to check the consistency of the assumptions – that is, determining if the proposed model rules indeed add up to a functional system. Consistent models based on biologically plausible rules may still fail in several aspects to behave as the experimental system does. In this (not uncommon) case the modeling effort is still useful as it can focus research on the less understood areas and thus help advance our understanding. We hope that an integrated experimental and theoretical effort will lead in a not so distant future to predictive quantitative models that can be considered both as a synthesis of our knowledge and as useful tools to plan experimental perturbations and medical interventions.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH R01 grants HL087136 (AC), HL068855 (CDL), the Hungarian Research Fund OTKA K72664 (AC), and the G. Harold & Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation (AC, CDL). We thank Drs Brenda Rongish and Andras Szabo for their comments on the manuscript.

References

- Alber M, Chen N, Glimm T, Lushnikov PM. Multiscale dynamics of biological cells with chemotactic interactions: from a discrete stochastic model to a continuous description. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2006;73:051901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.73.051901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrova A, Czir okA, Szabo A, Filla MB, Hossain MJ, Whelan PF, Lansford R, Rongish BJ. Convective tissue movements play a major role in avian endocardial morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2012;363:348–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt W. Biased random walk models for chemotaxis and related diffusion approximations. J Math Biol. 1980;9:147–177. doi: 10.1007/BF00275919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambler CA, Nowicki JL, Burke AC, Bautch VL. Assembly of trunk and limb blood vessels involves extensive migration and vasculogenesis of somite-derived angioblasts. Dev Biol. 2001;234:352–364. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson A, Chaplain M. Continuous and discrete mathematical-models of tumor-induced angiogenesis. Bulletin of mathematical biology. 1998;60:857–899. doi: 10.1006/bulm.1998.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barocas VH, Girton TS, Tranquillo RT. Engineered alignment in media equivalents: magnetic prealignment and mandrel compaction. J Biomech Eng. 1998;120:660–666. doi: 10.1115/1.2834759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barocas VH, Tranquillo RT. An anisotropic biphasic theory of tissue-equivalent mechanics: the interplay among cell traction, fibrillar network deformation, fibril alignment, and cell contact guidance. J Biomech Eng. 1998;119:137–145. doi: 10.1115/1.2796072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer AL, Jackson TL, Jiang Y. Topography of extracellular matrix mediates vascular morphogenesis and migration speeds in angiogenesis. PLOS Comp Biol. 2009;5:e1000445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayless KJ, Davis GE. Microtubule depolymerization rapidly collapses capillary tube networks in vitro and angiogenic vessels in vivo through the small gtpase rho. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11686–11695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley K, Mariggi G, Gerhardt H, Bates PA. Tipping the balance: robustness of tip cell selection, migration and fusion in angiogenesis. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beysens DA, Forgacs G, Glazier JA. Cell sorting is analogous to phase ordering in fluids. PNAS. 2000;97:9467–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Linden P, Shima D, Browne F, Folkman J. In vivo angiogenic activity and hypoxia induction of heterodimers of placenta growth factor/vascular endothelial growth factor. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2507–2511. doi: 10.1172/JCI119069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen RR, Silva EA, Yuen WW, Brock AA, Fischbach C, Lin AS, Guldberg RE, Mooney DJ. Integrated approach to designing growth factor delivery systems. FASEB J. 2007;21:3896–3903. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7873com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleaver O, Krieg PA. Vegf mediates angioblast migration during development of the dorsal aorta in xenopus. Development. 1998;125:3905–3914. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.19.3905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critser PJ, Kreger ST, Voytik-Harbin SL, Yoder MC. Collagen matrix physical properties modulate endothelial colony forming cell-derived vessels in vivo. Microvasc Res. 2010;80:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czirok A, Zach J, Kozel BA, Mecham RP, Davis EC, Rongish BJ. Elastic fiber macroassembly is a hierarchical, cell motion-mediated process. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207:97–106. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Bayless KJ, Mavila A. Molecular basis of endothelial cell morphogenesis in three-dimensional extracellular matrices. Anat Rec. 2002;268:252–275. doi: 10.1002/ar.10159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Black SM, Bayless KJ. Capillary morphogenesis during human endothelial cell invasion of three-dimensional collagen matrices. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2000;36:513–519. doi: 10.1290/1071-2690(2000)036<0513:CMDHEC>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes AT, Edelstein-Keshet L. Phosphoinositides and rho proteins spatially regulate actin polymerization to initiate and maintain directed movement in a one-dimensional model of a motile cell. Biophys J. 2007;92:744–768. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.090514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gennes P, Brochard-Wyart F, Quere D. Capillarity and Wetting Phenomena. New York: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Drake CJ, Brandt SJ, Trusk TC, Little CD. Tal1/scl is expressed in endothelial progenitor cells/angioblasts and defines a dorsal-to-ventral gradient of vasculogenesis. Dev Biol. 1997;192:17–30. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CJ, Fleming PA. Vasculogenesis in the day 6.5 to 9.5 mouse embryo. Blood. 2000;95:1671–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamme I, Breier G, Risau W. Vascular endothelial growth factor ( VEGF) and VEGF receptor 2 (flk-1) are expressed during vasculogenesis and vascular differentiation in the quail embryo. Dev Biol. 1995;169:699–712. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L, Chen Y, Prijatelj P, Sakai T, Fssler R, Sakai LY, Rifkin DB. Fibronectin is required for integrin alphavbeta6-mediated activation of latent TGF-beta complexes containing LTBP-1. FASEB J. 2005;19:1798–1808. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4134com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgacs G, Foty RA, Shafrir Y, Steinberg MS. Viscoelastic properties of living embryonic tissues: a quantitative study. Biophys J. 1998;74:2227–2234. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77932-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foty RA, Pfleger CM, Forgacs G, Steinberg MS. Surface tensions of embryonic tissues predict their mutual envelopment behavior. Development. 1996;122:1611–1620. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foty RA, Steinberg MS. The differential adhesion hypothesis: a direct evaluation. Dev Biol. 2005;278:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamba A, Ambrosi D, Coniglio A, de Candia A, Di Talia S, Giraudo E, Serini G, Preziosi L, Bussolino F. Percolation, morphogenesis, and burgers dynamics in blood vessels formation. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;90:118101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.118101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt H, Golding M, Fruttiger M, Ruhrberg C, Lundkvist A, Abramsson A, Jeltsch M, Mitchell C, Alitalo K, Shima D, Betsholtz C. Vegf guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:1163–1177. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girton TS, Dubey N, Tranquillo RT. Magnetic-induced alignment of collagen fibrils in tissue equivalents. Methods Mol Med. 1999;18:67–73. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-516-6:67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazier JA, Graner F. Simulation of the differential adhesion driven rearrangement of biological cells. Phys Rev E Stat Phys Plasmas Fluids Relat Interdiscip Topics. 1993;47:2128–2154. doi: 10.1103/physreve.47.2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guido S, Tranquillo RT. A methodology for the systematic and quantitative study of cell contact guidance in oriented collagen gels. correlation of fibroblast orientation and gel birefringence. J Cell Sci. 1993;105(Pt 2):317–331. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashambhoy YL, Chappell JC, Peirce SM, Bautch VL, Gabhann FM. Computational modeling of interacting vegf and soluble vegf receptor concentration gradients. Front Physiol. 2011;2:62. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegedus B, Marga F, Jakab K, Sharpe-Timms KL, Forgacs G. The interplay of cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions in the invasive properties of brain tumors. Biophysical Journal. 2006;91:2708–16. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.077834. PMID: 16829558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix MJC, Seftor EA, Hess AR, Seftor REB. Vasculogenic mimicry and tumour-cell plasticity: lessons from melanoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:411–421. doi: 10.1038/nrc1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson MS, Brodland GW, Yang J, Viens D. Cell sorting in three dimensions: topology, fluctuations, and fluidlike instabilities. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;101:148105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.148105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber DE, Folkman J. How does extracellular matrix control capillary morphogenesis? Cell. 1989;58:803–805. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90928-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaguirre JA, Chaturvedi R, Huang C, Cickovski T, Coffland J, Thomas G, Forgacs G, Alber M, Hentschel G, Newman SA, Glazier JA. Compucell, a multi-model framework for simulation of morphogenesis. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1129–1137. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson L, Franco CA, Bentley K, Collins RT, Ponsioen B, Aspalter IM, Rosewell I, Busse M, Thurston G, Medvinsky A, Schulte-Merker S, Gerhardt H. Endothelial cells dynamically compete for the tip cell position during angiogenic sprouting. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:943–953. doi: 10.1038/ncb2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller EF, Segel LA. Initiation of slime mold aggregation viewed as an instability. J Theor Biol. 1970;26:399–415. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(70)90092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh W, Stratman AN, Sacharidou A, Davis GE. In vitro three dimensional collagen matrix models of endothelial lumen formation during vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Methods Enzymol. 2008;443:83–101. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhn-Luque A, de Back W, Starruss J, Mattiotti A, Deutsch A, Perez-Pomares JM, Herrero MA. Early embryonic vascular patterning by matrix-mediated paracrine signalling: a mathematical model study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korff T, Augustin HG. Tensional forces in fibrillar extracellular matrices control directional capillary sprouting. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 19):3249–3258. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.19.3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouvroukoglou S, Dee KC, Bizios R, McIntire LV, Zygourakis K. Endothelial cell migration on surfaces modified with immobilized adhesive peptides. Biomaterials. 2000;21:1725–1733. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRue AC, Mironov VA, Argraves WS, Czirok A, Fleming PA, Drake CJ. Patterning of embryonic blood vessels. Dev Dyn. 2003;228:21–9. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauffenburger DA, Horwitz AF. Cell migration: a physically integrated molecular process. Cell. 1996;84:359–369. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiss M, Beckmann K, Girs A, Costell M, Fssler R. The role of integrin binding sites in fibronectin matrix assembly in vivo. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:502–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Qutub AA, Vempati P, Gabhann FM, Popel AS. Module-based multiscale simulation of angiogenesis in skeletal muscle. Theor Biol Med Model. 2011;8:6. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-8-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari G, Lauffenburger DA. Deconstructing (and reconstructing) cell migration. Microsc Res Tech. 1998;43:358–368. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19981201)43:5<358::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoussaki D, Lubkin SR, Vernon RB, Murray JD. A mechanical model for the formation of vascular networks in vitro. Acta Biotheor. 1996;44:271–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00046533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medico E, Mongiovi AM, Huff J, Jelinek MA, Follenzi A, Gaudino G, Parsons JT, Comoglio PM. The tyrosine kinase receptors ron and sea control ”scattering” and morphogenesis of liver progenitor cells in vitro. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:495–504. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.4.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mente C, Prade I, Brusch L, Breier G, Deutsch A. Parameter estimation with a novel gradient-based optimization method for biological lattice-gas cellular automaton models. J Math Biol. 2011;63:173–200. doi: 10.1007/s00285-010-0366-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merks RM, Brodsky SV, Goligorksy MS, Newman SA, Glazier JA. Cell elongation is key to in silico replication of in vitro vasculogenesis and subsequent remodeling. Dev Biol. 2011;289:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merks RMH, Perryn ED, Shirinifard A, Glazier JA. Contact-inhibited chemotaxis in de novo and sprouting blood-vessel growth. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montesano R, Orci L. Tumor-promoting phorbol esters induce angiogenesis in vitro. Cell. 1985;42:469–477. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin KT, Tranquillo RT. Guided sprouting from endothelial spheroids in fibrin gels aligned by magnetic fields and cell-induced gel compaction. Biomaterials. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Oster G, Harris A. A mechanical model for mesenchymal morphogenesis. J Math Biol. 1983;17:125–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00276117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namy P, Ohayon J, Tracqui P. Critical conditions for pattern formation and in vitro tubulogenesis driven by cellular traction fields. J Theor Biol. 1983;227:103–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman T. Modeling multicellular systems using subcellular elements. Math Biosci Eng. 2005;2:611–622. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2005.2.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter KJ. Modelling cell migration strategies in the extracellular matrix. J Math Biol. 2009;58:511–543. doi: 10.1007/s00285-008-0217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perryn ED, Czirok A, Little CD. Vascular sprout formation entails tissue deformations and ve-cadherin-dependent cell-autonomous motility. Dev Biol. 2008;313:545–555. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole T, Coffin J. Vasculogenesis and angiogenesis: Two distinct morphogenetic mechanisms establish embryonic vascular pattern. J Exp Zool. 1989;251:224–231. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402510210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole TJ, Finkelstein EB, Cox CM. The role of fgf and vegf in angioblast induction and migration during vascular development. Dev Dyn. 2001;220:1–17. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1087>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagan F. Vascularization phenomena in fragments of embryodic bodies completely isolated from yolk sac blastoderm. Anat Rec. 1915;9:329–241. [Google Scholar]

- Risau W, Flamme I. Vasculogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:73–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.000445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpold H, Wolf D, Koeck R, Gunsilius E. Endothelial progenitor cells: a source for therapeutic vasculogenesis? J Cell Mol Med. 2004;37:493–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp PA, Czirok A, Little CD. alphavbeta3 integrin-dependent endothelial cell dynamics in vivo. Development. 2004;131:2887–2897. doi: 10.1242/dev.01160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabin F. Studies on the origin of the blood vessels and of red blood corpusles as seen in the living blastoderm of chick during the second day of incubation. Carnegie Contrib Embryol. 1920;9:215–262. [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Poynter G, Huss D, Filla MB, Czirok A, Rongish BJ, Little CD, Fraser SE, Lansford R. Dynamic analysis of vascular morphogenesis using transgenic quail embryos. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12674. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney RK, Howard J. Slow local movements of collagen fibers by fibroblasts drive the rapid global self-organization of collagen gels. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:1083–1091. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selmeczi D, Mosler S, Hagedorn PH, Larsen NB, Flyvbjerg H. Cell motility as persistent random motion: theories from experiments. Biophys J. 2005;89:912–31. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.061150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serini G, Ambrosi D, Giraudo E, Gamba A, Preziosi L, Bussolino F. Modeling the early stages of vascular network assembly. EMBO J. 2003;22:1771–1779. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamloo A, Heilshorn SC. Matrix density mediates polarization and lumen formation of endothelial sprouts in vegf gradients. Lab Chip. 2010;10:3061–3068. doi: 10.1039/c005069e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamloo A, Ma N, Poo MM, Sohn LL, Heilshorn SC. Endothelial cell polarization and chemotaxis in a microfluidic device. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1292–1299. doi: 10.1039/b719788h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S,Wang F, Glavas S, Ott A, Hofmann F, Aktories K, Kalman D, Bourne HR. Rac and cdc42 play distinct roles in regulating pi(3,4,5)p3 and polarity during neutrophil chemotaxis. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:375–385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel D, Lundkvist A, Sauvaget D, Busse M, Graupera M, van der Flier A, Wijelath ES, Murray J, Sobel M, Costell M, Takahashi S, Fssler R, Yamaguchi Y, Gutmann DH, Hynes RO, Gerhardt H. Integrin-dependent and -independent functions of astrocytic fibronectin in retinal angiogenesis. Development. 2011;138:4451–4463. doi: 10.1242/dev.071381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes CL, Lauffenburger DA. Analysis of the roles of microvessel endothelial cell random motility and chemotaxis in angiogenesis. J Theor Biol. 1991;152:377–403. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes CL, Lauffenburger DA, Williams SK. Migration of individual microvessel endothelial cells: stochastic model and parameter measurement. J Cell Sci. 1991;99:419–30. doi: 10.1242/jcs.99.2.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoplak D, Harris A. Connective tissue morphogenesis by fibroblast traction. Dev Biol. 1982;90:383–398. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratman AN, Saunders WB, Sacharidou A, Koh W, Fisher KE, Zawieja DC, Davis MJ, Davis GE. Endothelial cell lumen and vascular guidance tunnel formation requires mt1-mmp-dependent proteolysis in 3-dimensional collagen matrices. Blood. 2009;114:237–247. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupack DG, Cheresh DA. Get a ligand, get a life: integrins, signaling and cell survival. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3729–3738. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo A, Czirok A. The role of cell-cell adhesion in the formation of multicellular sprouts. Math Model Nat Phenom. 2010;5:106. doi: 10.1051/mmnp/20105105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo A, Mehes E, Kosa E, Czirok A. Multicellular sprouting in vitro. Biophys J. 2008;95:2702–2710. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.129668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo A, Perryn ED, Czirok A. Network formation of tissue cells via preferential attraction to elongated structures. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;98:038102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.038102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo A, Unnep R, Mehes E, Twal WO, Argraves WS, Cao Y, Czirok A. Collective cell motion in endothelial monolayers. Phys Biol. 2010;7:046007. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/7/4/046007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo A, Varga K, Garay T, Hegedus B, Czirok A. Invasion from a cell aggregate–the roles of active cell motion and mechanical equilibrium. Phys Biol. 2012;9:016010. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/9/1/016010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura A, Kusuhara S, Wiegand SJ, Yu RT, ichi Nishikawa S. Tlx acts as a proangiogenic switch by regulating extracellular assembly of fibronectin matrices in retinal astrocytes. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:369–377. doi: 10.1172/JCI25964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon R, Lara S, Drake C, Iruela-Arispe M, Angello J, Little C, Wight T, Sage E. Organized type I collagen influences endothelial patterns during “spontaneous angiogenesis in vitro”: planar cultures as models of vascular development. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1995;31(3):120–131. doi: 10.1007/BF02633972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon RB, Angello JC, Iruela-Arispe ML, Lane TF, Sage EH. Reorganization of basement membrane matrices by cellular traction promotes the formation of cellular networks in vitro. Lab Invest. 1992;66:536–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon RB, Sage EH. A novel, quantitative model for study of endothelial cell migration and sprout formation within three-dimensional collagen matrices. Microvasc Res. 1999;57:118–133. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1998.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitorino P, Meyer T. Modular control of endothelial sheet migration. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3268–3281. doi: 10.1101/gad.1725808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltenberger J, Claesson-Welsh L, Siegbahn A, Shibuya M, Heldin CH. Different signal transduction properties of kdr and flt1, two receptors for vascular endothelial growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26988–26995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein B. What guides early embryonic blood vessel formation? Dev Dynamics. 1999;215:2–11. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199905)215:1<2::AID-DVDY2>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijelath ES, Murray J, Rahman S, Patel Y, Ishida A, Strand K, Aziz S, Cardona C, Hammond WP, Savidge GF, Rafii S, Sobel M. Novel vascular endothelial growth factor binding domains of fibronectin enhance vascular endothelial growth factor biological activity. Circ Res. 2002;91:25–31. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000026420.22406.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Rabkin-Aikawa E, Guleserian KJ, Perry TE, Masuda Y, Sutherland FWH, Schoen FJ, Mayer JEJ, Bischoff J. Tissue-engineered microvessels on three-dimensional biodegradable scaffolds using human endothelial progenitor cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;287:H480–H487. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01232.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancopoulos GD, Davis S, Gale NW, Rudge JS, Wiegand SJ, Holash J. Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature. 2000;407:242–8. doi: 10.1038/35025215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida A, Anand-Apte B, Zetter BR. Differential endothelial migration and proliferation to basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor. Growth Factors. 1996;13:57–64. doi: 10.3109/08977199609034566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajac M, Jones GL, Glazier JA. Simulating convergent extension by way of anisotropic differential adhesion. J Theor Biol. 2003;222:247–259. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(03)00033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zammaretti P, Zisch AH. Adult ’endothelial progenitor cells’ renewing vasculature. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:493–503. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]