Prolactin is well known as an endocrine hormone produced by the anterior pituitary and with reproductive and metabolic functions, but little is known about the in vivo functions of autocrine prolactin in normal tissues or the pathways that regulate its production. In this study, Chen et al. show that autocrine prolactin is required for terminal mammary epithelial differentiation during pregnancy in mice. They find that the PI2K–Akt signaling pathway up-regulates autocrine prolactin expression, even in the absence of the normal developmental or hormonal changes of pregnancy, leading to production of milk proteins and lactose.

Keywords: Pten, Akt, Stat5, mammary gland, lactation, differentiation

Abstract

Extrapituitary prolactin (Prl) is produced in humans and rodents; however, little is known about its in vivo regulation or physiological function. We now report that autocrine prolactin is required for terminal mammary epithelial differentiation during pregnancy and that its production is regulated by the Pten–PI3K–Akt pathway. Conditional activation of the PI3K–Akt pathway in the mammary glands of virgin mice by either Akt1 expression or Pten deletion rapidly induced terminal mammary epithelial differentiation accompanied by the synthesis of milk despite the absence of lobuloalveolar development. Surprisingly, we found that mammary differentiation was due to the PI3K–Akt-dependent synthesis and secretion of autocrine prolactin and downstream activation of the prolactin receptor (Prlr)–Jak–Stat5 pathway. Consistent with this, Akt-induced mammary differentiation was abrogated in Prl−/−, Prlr−/−, and Stat5−/− mice. Furthermore, cells treated with conditioned medium from mammary glands in which Akt had been activated underwent rapid Stat5 phosphorylation in a manner that was blocked by inhibition of Jak2, treatment with an anti-Prl antibody, or deletion of the prolactin gene. Demonstrating a physiological requirement for autocrine prolactin, mammary glands from lactation-defective Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice failed to express autocrine prolactin or activate Stat5 during late pregnancy despite normal levels of circulating serum prolactin and pituitary prolactin production. Our findings reveal that PI3K–Akt pathway activation is necessary and sufficient to induce autocrine prolactin production in the mammary gland, Stat5 activation, and terminal mammary epithelial differentiation, even in the absence of the normal developmental program that prepares the mammary gland for lactation. Together, these findings identify a function for autocrine prolactin during normal development and demonstrate its endogenous regulation by the PI3K–Akt pathway.

Prolactin (Prl) is a polypeptide hormone synthesized and released from the anterior pituitary gland that regulates lactation, reproduction, metabolism, immune responses, and electrolyte balance (Ben-Jonathan et al. 2008). When secreted into the circulation, pituitary Prl binds to the prolactin receptor (Prlr) and activates Jak2–Stat5 signaling, which is required for lobuloalveolar development in the mammary gland during pregnancy. Upon phosphorylation by Jak2, phospho-Stat5 translocates to the nucleus of mammary epithelial cells, where it regulates the transcription of target genes that mediate the dramatic pregnancy-induced changes that prepare the mammary gland for lactation (Hennighausen and Robinson 2005).

Consistent with the central role of Stat5 in pregnancy-induced mammary development, mice in which the Prl, Prlr, Jak2, or Stat5 genes have been deleted display severe defects in mammary differentiation and lactogenesis that are accompanied by loss of Stat5 activation (Horseman et al. 1997; Ormandy et al. 1997; Cui et al. 2004; Wagner et al. 2004). Similarly, aberrant activation or repression of molecules that regulate Stat5 activity, including ErbB2, ErbB4, Pak1, caveolin-1, Socs2, Id2, and Elf5, result in abnormal mammary epithelial differentiation during pregnancy and lactation (Jones and Stern 1999; Jones et al. 1999; Mori et al. 2000; Long et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2003; Zhou et al. 2005; Harris et al. 2006).

In addition to stimulating the Jak2–Stat5 pathway, Prl also activates PI3K–Akt signaling (Acosta et al. 2003; Chakravarti et al. 2005). These two signaling cascades mediate distinct aspects of the production of the three major components of milk: lactose, lipids, and milk proteins (Anderson et al. 2007). For example, while Stat5 regulates milk protein gene transcription in the mammary gland, Akt controls glucose transport, the translation of milk protein mRNAs, and the biosynthesis of lactose and lipids. Consequently, despite the fact that Stat5 activation and mammary epithelial differentiation occur normally in Akt1-deficient mice, loss of Akt1 results in impaired lactation at parturition due to an inability of mammary epithelial cells to up-regulate glucose uptake and lipid synthesis (Boxer et al. 2006). In contrast, deletion of one allele of Akt2 in Akt1-deficient mice results in a more severe lactation defect that is attributable, at least in part, to a failure of pregnant Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice to up-regulate the positive regulator of Prlr–Jak–Stat5 signaling, Id2, or down-regulate the negative regulators of Prlr–Jak–Stat5 signaling, caveolin-1 and Socs2 (Chen et al. 2010). These and other findings suggest that Akt regulates Stat5 signaling in the mammary gland during pregnancy.

To further characterize the role of the PI3K–Akt pathway in regulating mammary differentiation, we generated mice in which Akt1 can be inducibly activated or Pten can be conditionally deleted in the mammary epithelium. We now report that acute activation of the PI3K–Akt pathway in virgin mice induces rapid Stat5 activation, terminal mammary epithelial differentiation, and milk production that are mediated by the secretion of autocrine prolactin. Remarkably, these changes occur in the absence of lobuloalveolar development or the complex hormonal changes that accompany pregnancy. Consistent with this, we found that the inability of Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice to activate Stat5 and initiate lactation at parturition is due to their inability to synthesize and secrete autocrine prolactin. Our findings provide the first demonstration that PI3K–Akt signaling regulates the synthesis and secretion of autocrine prolactin in the mammary gland, identify an in vivo physiological function for autocrine prolactin, and reveal a direct connection between the Akt and Stat5 signaling cascades.

Results

Akt1 rapidly induces secretory differentiation in the virgin mammary gland in the absence of lobuloalveolar development

To explore the role of the PI3K–Akt pathway in regulating mammary differentiation, we generated doxycycline-inducible Akt1 transgenic mice, MMTV-rtTA;TetO-Akt1 (MTB/tAkt1), which conditionally express an activated allele of Akt1 in the mammary epithelium (Gunther et al. 2002; Boxer et al. 2006). Administration of doxycycline (2 mg/mL) to 6-wk-old virgin MTB/tAkt1 mice for 96 h induced expression of myristoylated Akt1 in the mammary ductal epithelium (Fig. 1A). Morphological analysis of carmine-stained mammary gland whole mounts revealed that epithelial ducts in the mammary glands of virgin doxycycline-induced MTB/tAkt1 mice were increased in caliber compared with MTB controls but did not appear to contain alveoli (Fig. 1B). Surprisingly, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained tissue sections from MTB/tAkt1 virgin mice induced with doxycycline for 96 h were morphologically similar to mammary tissues harvested from lactating mice in that mammary ducts were distended with lipid-laden, proteinaceous material similar to that found within alveoli during lactation (Fig. 1C).

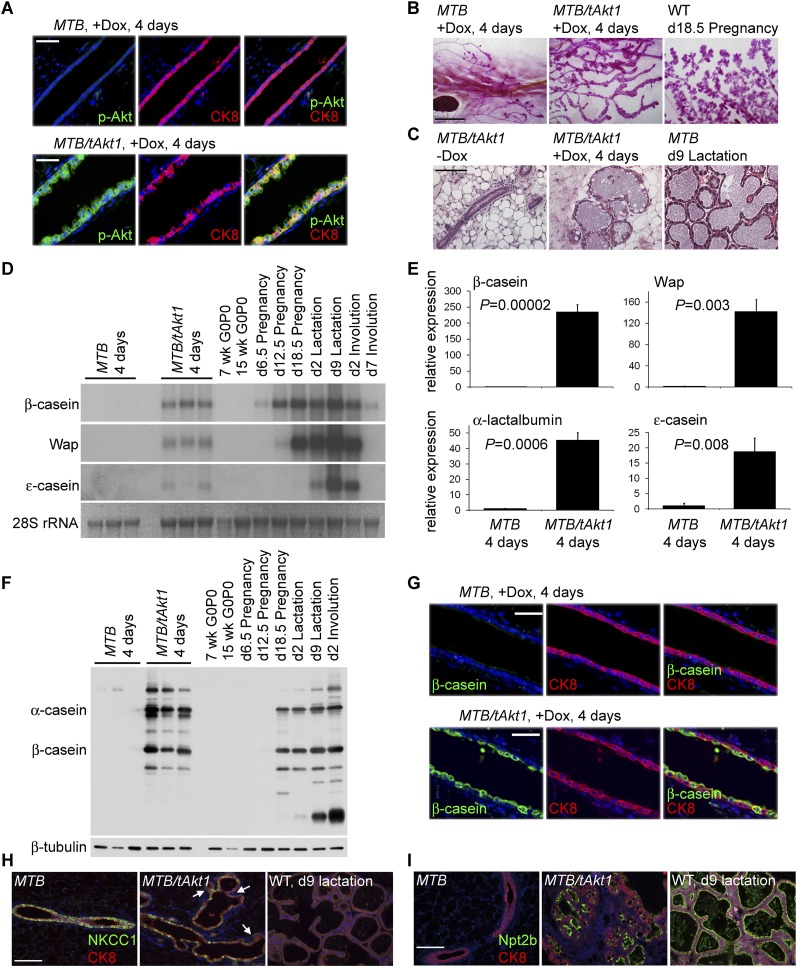

Figure 1.

Akt activation induces secretory differentiation and milk production in the virgin mammary gland. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis for expression of p-Akt and the luminal epithelial marker cytokeratin 8 (CK8) in the mammary glands of MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice induced with doxycycline for 96 h. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Bars, 50 μm. (B) Whole-mount staining of the mammary glands of MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice induced with doxycycline for 96 h. Bars, 5 mm. (C) H&E-stained sections of mammary tissue from induced (+Dox) and uninduced (−Dox) MTB/tAkt1 mice and lactating MTB control mice. Bars, 100 μm. (D) Northern analysis of milk protein gene expression in mammary glands from doxycycline-induced MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice. Wild-type FVB mice at the indicated developmental stages are shown as controls for the temporal expression patterns of individual milk protein genes. 28S rRNA served as a loading control. (E) Quantitative RT–PCR analysis of milk protein gene expression in mammary glands from induced MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice. Gene expression levels were normalized to cytokeratin 18. Error bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). (F) Immunoblotting analysis of total milk proteins in mammary glands from MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice induced with doxycycline for 96 h and wild-type FVB mice at the indicated developmental stages. β-Tubulin served as a loading control. (G) Immunofluorescence analysis of β-casein and CK8 expression in the mammary glands of MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice induced with doxycycline for 96 h. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Bars, 50 μm. (H,I) Immunofluorescence analysis of NKCC1 (H) and Npt2b (I) expression in the mammary glands of MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice induced with doxycycline for 96 h as well as lactating wild-type controls. Arrows indicate epithelial cells that have down-regulated NKCC1 expression. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Bars, 100 μm.

Northern analysis of mammary tissues from virgin MTB/tAkt1 mice in which Akt had been activated for 96 h revealed that milk protein genes normally up-regulated during early pregnancy (β-casein) or mid-pregnancy (Wap) were expressed at levels comparable with those observed in mid- to late-pregnant wild-type mice (Fig. 1D). MTB/tAkt1 mice acutely induced with doxycycline also expressed the late milk protein gene ɛ-casein, which is normally not expressed until the onset of lactation (Fig. 1D). Quantitative RT–PCR indicated that expression levels of β-casein, Wap, α-lactalbumin, and ɛ-casein mRNAs were increased by 235-fold, 142-fold, 45-fold, and 19-fold, respectively, compared with virgin MTB controls, although levels were lower than those observed in wild-type mice at day 2 of lactation (14-fold, 132-fold, 12-fold, and 391-fold less, respectively) (Fig. 1E; data not shown). Consistent with these findings, immunoblotting revealed that α-casein and β-casein proteins were expressed in the mammary glands of doxycycline-induced MTB/tAkt1 virgin mice at levels comparable with those found in lactating wild-type mice (Fig. 1F). Immunofluorescence staining confirmed the colocalization of β-casein and phospho-Akt expression in the ductal epithelium of doxycycline-induced MTB/tAkt1 mice (Fig. 1G).

The Na-K-Cl cotransporter NKCC1 is expressed at high levels in ductal epithelial cells of virgin mice and is down-regulated during pregnancy (Shillingford et al. 2002a,b, 2003). Consistent with the ability of Akt to rapidly induce a lactation-like state in virgin animals, only rare NKCC1-staining cells were detected in the mammary glands of doxycycline-induced MTB/tAkt1 mice (Fig. 1H). Conversely, the transporter Npt2b is not expressed in the mammary epithelium of virgin mice but is expressed throughout the alveolar epithelium of lactating mice (Miyoshi et al. 2001). Concordant with the differentiated appearance of mammary glands in which Akt1 had been induced, mammary epithelial cells in doxycycline-induced MTB/tAkt1 mice exhibited strong Npt2b staining (Fig. 1I). In aggregate, these findings demonstrate that Akt1 activation rapidly induces secretory differentiation in mammary epithelial cells in vivo.

In wild-type mice, β-casein is expressed predominantly in alveolar secretory subunits during early and mid-pregnancy. Only in late pregnancy—after >2 wk of lobuloalveolar development induced by exposure to hormones of pregnancy—does β-casein become expressed in ductal cells (Supplemental Fig. S1). Notably, we found that acute Akt1 activation rapidly induced ductal epithelial cells to express β-casein without the antecedent formation of alveolar structures. This suggested that Akt's ability to induce milk protein expression is not an indirect consequence of Akt-induced lobuloalveolar development, but rather may be due to Akt's ability to directly control epithelial secretory differentiation and the production of each of the major components of milk.

Pten deletion induces secretory differentiation in the virgin mammary gland

We next examined whether activation of endogenous Akt at physiological levels would also induce secretory differentiation in the mammary glands of virgin mice. To address this, we generated mice in which the tumor suppressor Pten, an inhibitor of the PI3K–Akt pathway, could be conditionally deleted in the mammary epithelium in response to doxycycline treatment. Ptenfl/fl mice (Groszer et al. 2001) were bred to MTB/TetO-Cre (TTC1) mice, in which Cre expression is under the control of the tet operator, to generate MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mice or MTB;Ptenfl/fl controls. As predicted, Pten expression was markedly decreased in the mammary epithelium of virgin MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mice in which Cre expression was induced with 2 mg/mL doxycycline for 2 wk, whereas Pten expression persisted in the mammary epithelium and surrounding stroma of control MTB;Ptenfl/fl mice (Fig. 2A).

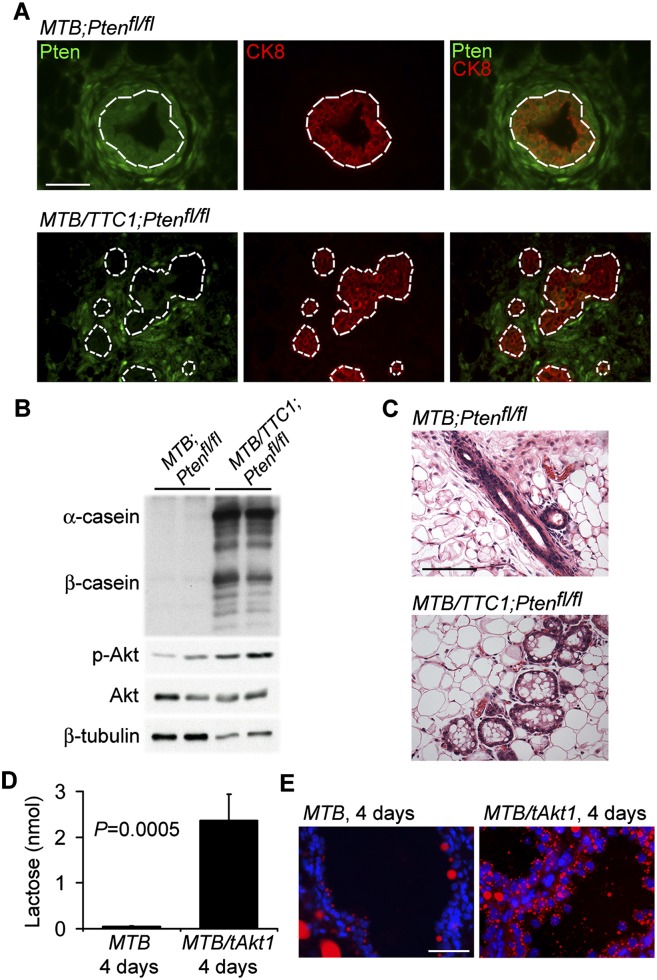

Figure 2.

Pten deletion induces secretory differentiation in virgin mice. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis for expression of Pten and the luminal epithelial marker CK8 in the mammary glands of virgin MTB;Ptenfl/fl and MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mice induced with doxycycline for 2 wk. Bars, 50 μm. Dotted lines indicate the demarcation between the mammary epithelium and the mammary stroma. (B) Immunoblotting analysis of mammary protein lysates from MTB;Ptenfl/fl and MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mice induced with doxycycline for 2 wk. β-Tubulin served as a loading control. (C) H&E-stained sections of mammary tissues from B. Bars, 100 μm. (D) Lactose levels of mammary tissues from induced MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice (n = 4). Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. (E) Nile red staining of cytoplasmic lipid droplets in the mammary glands of MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice induced with doxycycline for 96 h. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Bars, 50 μm.

Accompanying the deletion of Pten, phospho-Akt levels were elevated in the mammary glands of doxycycline-induced MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mice compared with MTB;Ptenfl/fl controls (Fig. 2B). Consistent with our observations in doxycycline-induced MTB/tAkt1 mice, the mammary glands of doxycycline-induced MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mice contained lipid-laden, proteinaceous material and were histologically similar to the mammary glands of doxycycline-induced MTB/tAkt1 mice (Fig. 2C). Quantitative RT–PCR demonstrated that doxycycline-induced MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mammary glands exhibited 158-fold, 112-fold, fourfold, and sixfold increases in expression levels of β-casein, Wap, α-lactalbumin, and ɛ-casein mRNAs, respectively, compared with MTB;Ptenfl/fl controls (data not shown). In agreement with this, doxycycline-induced MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mammary glands expressed high levels of milk proteins (Fig. 2B). These data demonstrate that activation of endogenous Akt by conditionally deleting Pten is sufficient to promote mammary epithelial differentiation in virgin mice.

Akt1 induces the synthesis of all major milk components in virgin mice

Our previous observation that the biosynthesis of all three major components of milk—lactose, lipids, and milk proteins—is greatly reduced in Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice (Chen et al. 2010) led us to examine whether Akt-induced mammary epithelial differentiation is sufficient to induce the production of lactose and lipids as well as milk proteins in the virgin mammary gland.

Lactose synthesis from glucose and galactose in mammary epithelial cells during lactation is catalyzed by lactose synthase. The activity and specificity of this enzyme is regulated by its cofactor, α-lactalbumin (Permyakov and Berliner 2000). Our observation that Akt1 activation in virgin MTB/tAkt1 mice induced the expression of α-lactalbumin mRNA 45-fold compared with control MTB mice, coupled with our prior observation that Akt1 activation in virgin MTB/tAkt1 mice markedly up-regulates expression of the glucose transporter Glut1 (Boxer et al. 2006), suggested that Akt1 activation might be sufficient to induce lactose synthesis in virgin mice. As predicted, MTB/tAkt1 mice induced with doxycycline for 96 h exhibited a 50-fold increase in lactose levels (Fig. 2D).

During lactation, Akt1 is required for maximal lipid synthesis by means of its regulation of the expression of key metabolic enzymes (Boxer et al. 2006). Consistent with this, staining for lipids revealed that Akt1-expressing cells in the mammary glands of doxycycline-induced MTB/tAkt1 mice contained abundant cytoplasmic lipid droplets, whereas MTB control cells did not (Fig. 2E). Akt1 activation also induced mammary epithelial-specific expression of the fatty acid synthesis genes Aldoc, Fads1, and Elovl5 (Supplemental Fig. S2). Together, our results indicate that Akt1 activation is sufficient to rapidly induce production of the three main components of milk—milk proteins, lipid, and lactose—in the mammary glands of virgin mice.

Akt induces Stat5 activation

The Prlr–Jak2–Stat5 signaling pathway is required for terminal differentiation of the alveolar epithelium during pregnancy, as deletion of Prlr, Jak2, or Stat5 leads to decreased Stat5 activation, lobuloalveolar development, and milk protein gene expression (Liu et al. 1997; Ormandy et al. 1997; Teglund et al. 1998; Cui et al. 2004; Wagner et al. 2004). To test the possibility that Akt-induced mammary epithelial differentiation is mediated by this pathway, we examined Stat5 activity in doxycycline-induced virgin MTB/tAkt1 as well as MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mice.

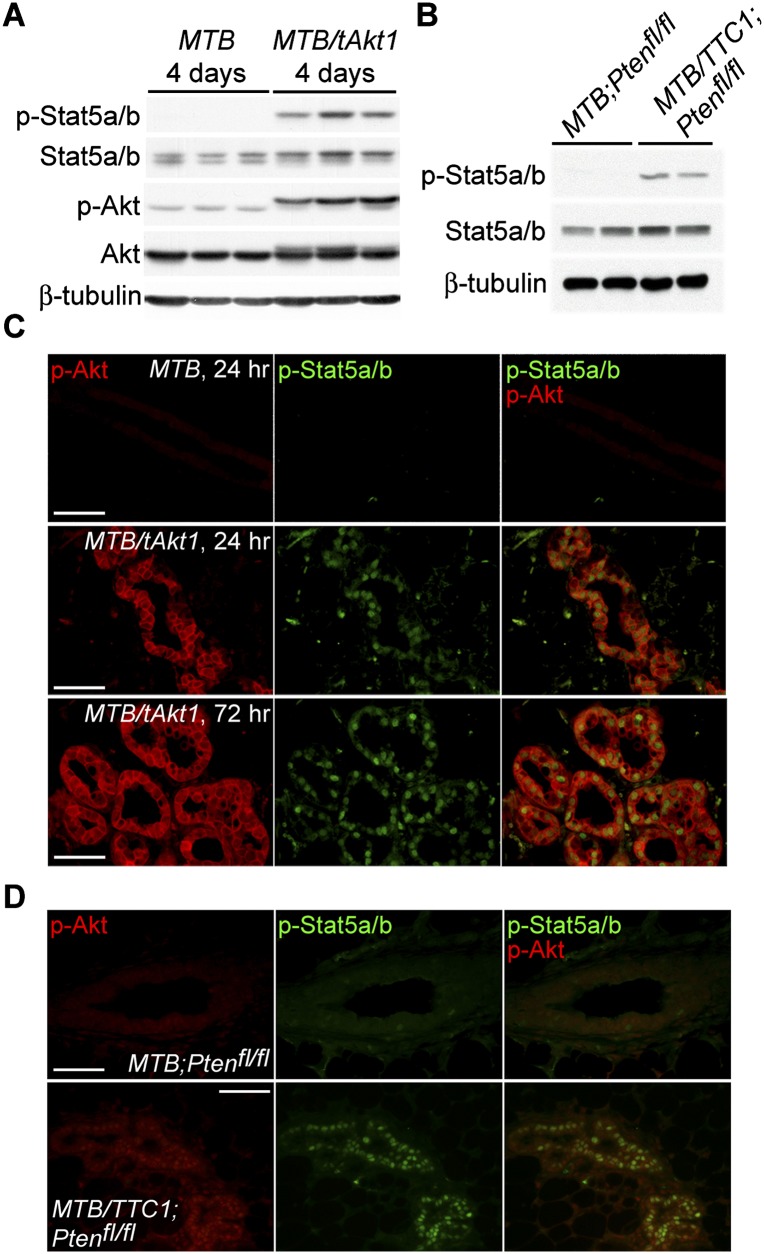

Immunoblotting revealed that Akt activation rapidly induced high levels of phospho-Stat5a/b in mammary tissues from doxycycline-induced virgin MTB/tAkt1 as well as MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mice that was absent in MTB control mice (Fig. 3A,B). Consistent with these findings, nuclear phospho-Stat5a/b was detected by immunofluorescence in most, although not all, ductal epithelial cells expressing p-Akt in MTB/tAkt1 and MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mice but not in ductal epithelial cells in control MTB mice (Fig. 3C,D).

Figure 3.

Akt induces Stat5 activation. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of mammary protein lysates from virgin MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice induced with doxycycline for 96 h. The top bands of the p-Akt and Akt doublets correspond to the transgene-encoded myristoylated Akt1. β-Tubulin served as a loading control. (B) Immunoblotting analysis of mammary protein lysates from virgin MTB;Ptenfl/fl and MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mice induced with doxycycline for 14 d. β-Tubulin served as a loading control. (C) Immunofluorescence analysis of p-Stat5a/b and p-Akt expression in mammary sections from virgin MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice induced with doxycycline for 24 or 72 h. Bars, 50 μm. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of p-Stat5a/b and p-Akt expression in mammary sections from virgin MTB;Ptenfl/fl and MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mice induced with doxycycline for 14 d. Bars, 50 μm.

To determine whether the ability of Akt1 to induce Stat5 activation in MTB/tAkt1 mice is due to its action in the mammary gland or requires systemic hormonal alterations, we transplanted MTB/tAkt1 mammary glands into wild-type recipient mice. Four weeks following transplantation, recipient mice were induced with doxycycline for 96 h. Activation of Akt in transplanted MTB/tAkt1 glands resulted in rapid Stat5 phosphorylation, milk protein production, and distension of mammary ducts with milk in a manner similar to that observed in intact MTB/tAkt1 mice (Supplemental Fig. S3A,B).

To confirm that the ability of Akt1 to induce Stat5 activation is due to Akt transgene expression in mammary epithelial cells, we injected isolated mammary epithelial cells from MTB/tAkt1 mice into the cleared fat pads of wild-type recipients, allowed ductal outgrowth for 6 wk, and then induced recipient mice with doxycycline for 96-h. Activation of Akt in the transplanted epithelial cells of recipient mice resulted in rapid Stat5 phosphorylation, milk protein production, and distension of mammary ducts with milk (Supplemental Fig. S3C,D).

Akt1 activation also induced rapid Stat5 phosphorylation in explanted MTB/tAkt1 glands induced with doxycycline in vitro (Supplemental Fig. S4A). Similarly, phospho-Stat5a/b levels were elevated in vitro in mammary glands harvested from MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mice that had been treated with doxycycline to induce deletion of Pten (Supplemental Fig. S4B). Together, our observations indicate that activation of the Pten–Akt pathway results in rapid Stat5 activation in mammary epithelial cells in vivo and in vitro in a manner that is cell-intrinsic.

Akt-induced mammary differentiation requires Prlr and Stat5a/b

To determine whether Akt-induced mammary differentiation in virgin mice is mediated by Stat5, we asked whether genetic disruption of the Stat5a/b genes would block mammary differentiation induced by sustained Akt activity. Akt1 expression was induced for 96 h in 6-wk-old virgin MTB/tAkt1 mice that were either wild type or heterozygous or homozygous for hypomorphic alleles of both the Stat5a and Stat5b genes (Stat5a/b+/+, Stat5a/b+/−, Stat5a/b−/−).

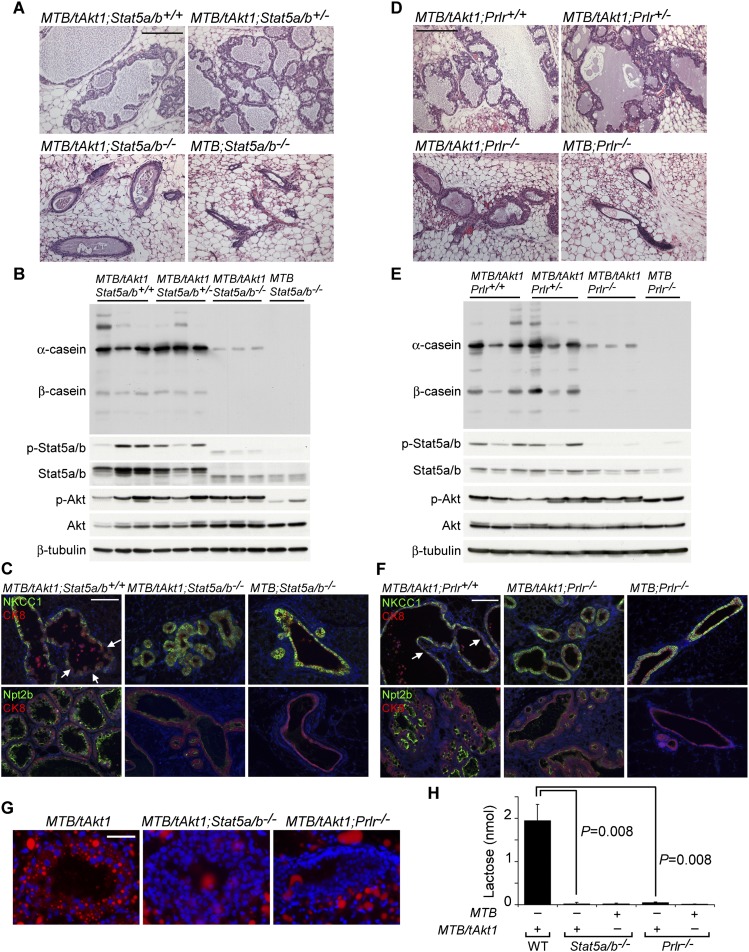

Consistent with our earlier findings, H&E staining revealed that mammary ducts in MTB/tAkt1;Stat5a/b+/+ and MTB/tAkt1;Stat5a/b+/− mice were distended with proteinaceous material containing lipid droplets similar to that observed in the mammary glands of lactating mice (Fig. 4A). In contrast, mammary ducts in MTB/tAkt1;Stat5a/b−/− mice were compact and lacked a differentiation phenotype (Fig. 4A). Western analysis revealed that milk protein expression induced by Akt1 was dramatically attenuated in MTB/tAkt1;Stat5a/b−/− mice and was accompanied by reduced levels of phosphorylation of the truncated Stat5a/b proteins (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Akt-mediated differentiation of the virgin mammary gland requires Stat5a/b and Prlr. (A) H&E-stained mammary sections from doxycycline-induced virgin MTB and MTB/tAkt1 wild-type mice or mice heterozygous or homozygous for a hypomorphic allele of Stat5a/b. Bars, 200 μm. (B) Immunoblotting analysis of mammary protein lysates corresponding to mice in A. The faster-migrating p-Stat5a/b and Stat5a/b bands represent the N-terminal-truncated Stat5a/b protein encoded by the hypomorphic allele of Stat5a/b. β-Tubulin served as a loading control. (C) Immunofluorescence analysis of NKCC1 (top) and Npt2b (bottom) expression in mammary tissues from doxycycline-induced 6-wk-old virgin MTB/tAkt1 mice of the indicated Stat5a/b genotypes. Luminal epithelial cells were coimmunostained with CK8. Arrows denote mammary epithelial cells in which NKCC1 expression was not detected. Mammary tissues from MTB mice homozygous for mutant alleles of Stat5a/b served as negative controls. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Bars, 100 μm. (D) H&E-stained mammary sections from doxycycline-induced virgin MTB/tAkt1 wild-type mice and mice heterozygous or homozygous for a null allele of Prlr. Bars, 200 μm. (E) Immunoblotting analysis of mammary protein lysates corresponding to mice in D. (F) Immunofluorescence analysis of NKCC1 (top) and Npt2b (bottom) expression in mammary tissues from doxycycline-induced 6-wk-old virgin MTB/tAkt1 mice of the indicated Prlr genotypes. Luminal epithelial cells were coimmunostained with CK8. Arrows denote mammary epithelial cells in which NKCC1 expression was not detected. Mammary tissues from MTB mice homozygous for mutant alleles of Prlr served as negative controls. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Bars, 100 μm. (G) Nile red staining of cytoplasmic lipid droplets in the mammary glands of doxycycline-induced virgin MTB/tAkt1, MTB/tAkt1;Stat5a/b−/−, and MTB/tAkt1;Prlr−/− mice. Bars, 50 μm. (H) Lactose levels in mammary glands from doxycycline-induced virgin MTB/tAkt1, MTB/tAkt1;Stat5a/b−/−, and MTB/tAkt1;Prlr−/− mice. MTB;Stat5a/b−/− and MTB;Prlr−/− mice are included as controls. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

Further evidence that Akt activation is unable to induce mammary epithelial differentiation in MTB/tAkt1;Stat5a/b−/− mice came from immunofluorescence analyses for NKCC1 and Npt2b expression. In contrast to the differentiated patterns of NKCC1 and Npt2b expression observed in the mammary epithelium of doxycycline-induced MTB/tAkt1 mice, attenuation of Stat5 activity in MTB/tAkt1;Stat5a/b−/− mice blocked Akt activation-induced differentiation of mammary epithelium as indicated by the failure to down-regulate NKCC1 or up-regulate Npt2b (Fig. 4C). In aggregate, these results demonstrate that mammary glands from induced MTB/tAkt1;Stat5a/b−/− virgin mice fail to undergo secretory differentiation following Akt activation.

Increasing prolactin levels during pregnancy result in Stat5 activation through binding to Prlr, activation of Jak2, and Jak2-directed Stat5 phosphorylation (Furth et al. 2011). However, Stat5 phosphorylation can also occur downstream from pathways other than Prlr. To further explore the requirement for the Prlr–Jak2–Stat5 signaling pathway in Akt activation-induced mammary differentiation, we generated bitransgenic MTB/tAkt1 mice that were wild type or heterozygous or homozygous for null alleles of Prlr (MTB/tAkt1;Prlr+/+, MTB/tAkt1;Prlr+/−, and MTB/tAkt1;Prlr−/−). As with Stat5 hypomorphism, genetic ablation of Prlr resulted in the abrogation of Akt-induced mammary epithelial differentiation, as evidenced by dramatic attenuation of Akt-induced milk protein expression, Stat5a/b phosphorylation, and mammary ductal distension in MTB/tAkt1;Prlr−/− mice (Fig. 4D,E). Immunofluorescence analysis confirmed that Prlr deletion also abrogated Akt-induced differentiated patterns of expression for NKCC1 and Npt2b (Fig. 4F). Taken together, these findings establish that Prlr and Stat5a/b are required for Akt-induced mammary epithelial differentiation in virgin mice.

We next examined whether Akt-induced lipid and lactose biosynthesis were dependent on Prlr–Stat5 signaling. Following Akt activation, the mammary epithelium of MTB/tAkt1 mice lacking either Stat5a/b or Prlr failed to accumulate cytoplasmic lipid droplets or induce lactose synthesis (Fig. 4G,H). This latter defect was likely due to the 80% reduction in Akt-induced α-lactalbumin mRNA expression observed in mutant mice (Supplemental Fig. S5A) rather than to a defect in glucose transport, since Glut1 expression and localization were unaffected by Stat5 or Prlr deletion (Supplemental Fig. S5B). Together, these results demonstrate that Akt-induced production of each of the three major components of milk requires a functional Prlr–Jak–Stat5 pathway despite the fact that the Akt-mediated regulation of Glut1 occurs independently of Prlr and Stat5.

The requirement for Stat5a/b and Prlr for Akt-induced differentiation is intrinsic to the mammary gland

Mice bearing germline mutations in Stat5a/b or Prlr exhibit developmental abnormalities in the mammary gland as well as other organs (Bole-Feysot et al. 1998; Cui et al. 2004). To rule out the possibility that the block in Akt-induced mammary differentiation observed in MTB/tAkt1;Stat5a/b−/− and MTB/tAkt1;Prlr−/− mice might be secondary to systemic effects of Stat5a/b or Prlr deletion, we induced Akt1 in mammary glands cultured in vitro and examined milk protein expression as a surrogate marker for mammary differentiation.

Following treatment with doxycycline for 4 d, explanted glands from MTB/tAkt1 mice expressed milk proteins as well as elevated levels of phospho-Stat5a/b (Supplemental Fig. S6A,B). In contrast, Akt activation in mammary tissue from Stat5a/b−/− and Prlr−/− mice failed to induce milk protein synthesis (Supplemental Fig. S6A,B). These data demonstrate that the defect in Akt-induced mammary differentiation in MTB/tAkt1;Stat5a/b−/− and MTB/tAkt1;Prlr−/− mice is due to a requirement for Stat5 activation in the mammary gland rather than to systemic alterations in these mice.

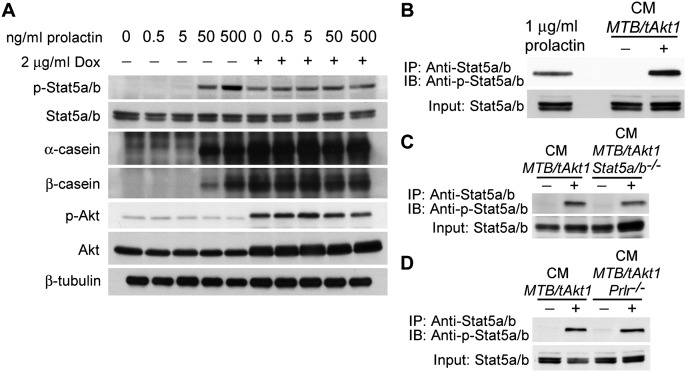

Akt induces expression of a secreted factor responsible for Stat5 activation and milk protein expression

The finding that Akt activation in the mammary gland results in rapid Stat5 phosphorylation and expression of milk proteins suggested that Akt might directly mediate activation of the Stat5 signaling pathway. Indeed, Akt activation induced in vitro by doxycycline treatment of explanted MTB/tAkt1 mammary tissue was capable of inducing Stat5 phosphorylation and milk protein expression when cultured in the absence of prolactin (Fig. 5A). In contrast, at least 50 ng/mL exogenous prolactin was required to induce Stat5 phosphorylation in uninduced mammary tissues from MTB/tAkt1 mice.

Figure 5.

Akt induces expression of a secreted factor responsible for Stat5 activation and milk protein expression. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of protein lysates from MTB/tAkt1 mammary glands treated ex vivo with the indicated doses of prolactin in the absence (−Dox) or presence (+Dox) of 2 μg/mL doxycycline. (B) Immunoblotting analysis of Stat5a/b immunoprecipitated from HC11 cells incubated for 20 min with CM harvested from wild-type MTB/tAkt1 mammary tissues induced with doxycycline for 4 d ex vivo (+Dox) or untreated (−Dox). Lysate from HC11 cells treated with 1 μg/mL prolactin is shown as a positive control. (C) Immunoblotting analysis of Stat5a/b immunoprecipitated from HC11 cells incubated for 20 min with CM harvested from wild-type or Stat5a/b−/− MTB/tAkt1 mammary tissues induced with doxycycline ex vivo. (D) Immunoblotting analysis of Stat5a/b immunoprecipitated from HC11 cells incubated for 20 min with CM harvested from wild-type or Prlr−/− MTB/tAkt1 mammary tissues induced with doxycycline ex vivo.

Since Akt is a serine/threonine kinase, we reasoned that it was unlikely to directly phosphorylate Stat5 at Tyr694 or Tyr699. Rather, we hypothesized that Akt might induce the secretion of a factor capable of activating Stat5 via an autocrine or paracrine loop. To test this hypothesis, we incubated the nontransformed mammary epithelial cell line HC11 with conditioned medium (CM) harvested from explanted MTB/tAkt1 mammary glands induced with doxycycline in vitro. When applied to HC11 cells, CM from doxycycline-induced MTB/tAkt1 glands induced Stat5 phosphorylation, whereas CM from uninduced MTB/tAkt1 glands did not (Fig. 5B). Notably, CM from doxycycline-induced MTB/tAkt1 mammary tissues lacking Stat5a/b or Prlr was capable of inducing Stat5 phosphorylation in HC11 cells to levels similar to those observed following treatment with CM from MTB/tAkt1 mice wild-type for Stat5a/b and Prlr (Fig. 5C,D). Taken together, these results indicate that Akt activation in mammary epithelial cells induces the secretion of a factor that activates Stat5 in an autocrine or paracrine manner and that production of this factor does not require Stat5a/b or Prlr.

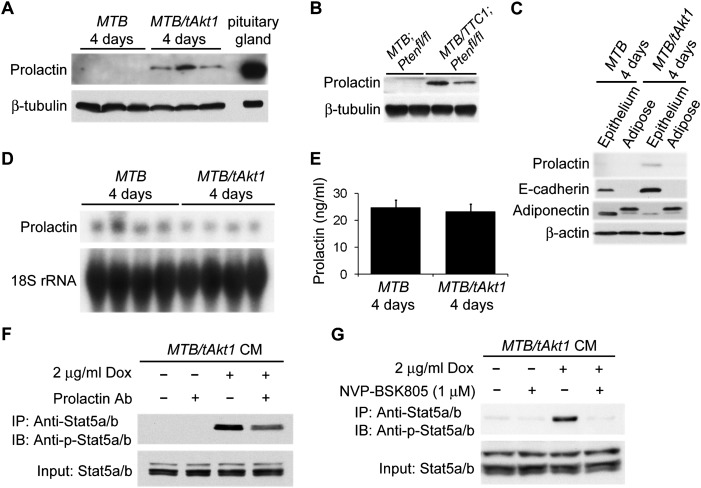

Akt induces the expression and secretion of autocrine prolactin in the mammary gland

Since we had found that the ability of Akt1 to induce Stat5 phosphorylation and mammary epithelial differentiation in mice requires the presence of Prlr, we considered the possibility that these effects of Akt1 are mediated by the autocrine production of prolactin. To test this hypothesis, we first examined prolactin expression in the mammary gland following Akt1 activation in vivo. As expected, prolactin protein was highly expressed in the pituitary glands of wild-type FVB mice but was not detected in the mammary glands of virgin MTB or MTB;Ptenfl/fl mice (Fig. 6A,B). In contrast, prolactin protein was clearly detectable in the mammary glands of doxycycline-induced MTB/tAkt1 mice as well as doxycycline-induced MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mice (Fig. 6A,B). Prolactin expression in the mammary glands of induced MTB/tAkt1 mice occurred in the epithelial compartment (Fig. 6C), which is also the site of Akt1 induction.

Figure 6.

Akt induces autocrine prolactin expression in the mammary gland. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of prolactin expression in the mammary glands of virgin MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice induced with doxycycline for 96 h. Protein lysates from pituitary glands of wild-type mice served as a positive control. β-Tubulin served as a loading control. (B) Immunoblotting analysis of prolactin expression in the mammary glands of MTB;Ptenfl/fl and MTB/TTC1;Ptenfl/fl mice induced with doxycycline for 4 wk. β-Tubulin served as a loading control. (C) Immunoblotting analysis of prolactin expression in purified epithelial and adipose fractions generated from the mammary glands of MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice treated with doxycycline for 4 d. E-cadherin and adiponectin served as controls for epithelial and adipose cells, respectively. β-Actin served as a loading control. (D) Northern analysis of prolactin mRNA expression in mammary glands from doxycycline-induced virgin MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice. 18S rRNA served as an RNA loading control. (E) Serum prolactin levels in MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice induced with doxycycline for 96 h (n = 5). (F) Immunoblotting analysis of Stat5a/b immunoprecipitates from HC11 cells incubated for 20 min with CM harvested from wild-type MTB/tAkt1 mammary tissues induced with doxycycline for 4 d ex vivo (+Dox) or untreated (−Dox). CM were preincubated with anti-prolactin antibody or IgG control for 30 min at room temperature prior to incubation with HC11 cells. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. (G) Immunoblotting analysis of Stat5a/b immunoprecipitated from HC11 cells pretreated with the Jak2 inhibitor NVP-BSK805 (1 μM) for 1 h followed by incubation with CM for 20 min. CM was harvested from wild-type MTB/tAkt1 mammary tissues induced with doxycycline for 4 d ex vivo (+Dox) or untreated (−Dox).

Interestingly, levels of prolactin mRNA in the mammary glands of induced MTB/tAkt1 mice were detectable but unchanged compared with MTB mice (Fig. 6D). In addition, circulating levels of prolactin were unchanged in doxycycline-induced MTB/tAkt1 mice (Fig. 6E), suggesting that the observed increase in prolactin in the mammary gland was not the result of an increase in systemic prolactin levels. When considered together, our findings demonstrate that the increase in prolactin protein levels observed in the mammary gland following Akt activation is not due to systemic changes in circulating prolactin or increased autocrine prolactin mRNA expression in the mammary gland, but is instead the result of Akt-induced post-transcriptional regulation of prolactin expression in mammary epithelial cells.

We next wished to determine whether the mammary-derived factor present in CM from doxycycline-induced MTB/tAkt1 glands that was capable of activating Stat5 when applied to HC11 cells was indeed prolactin. To address this, CM harvested from MTB/tAkt1 mammary tissues was incubated with an anti-prolactin antibody for 30 min. When compared with CM incubated with an IgG control, CM that had been neutralized with a prolactin antibody exhibited a reduced ability to stimulate Stat5 phosphorylation (Fig. 6F). CM also failed to stimulate Stat5 phosphorylation when HC11 cells were pretreated for 1 h with the Jak2-specific inhibitor NVP-BSK805 in accordance with the requirement for Jak2 in prolactin-induced Stat5 activation (Fig. 6G; Baffert et al. 2010).

The above findings strongly suggested that prolactin is the Akt-inducible factor in CM that is responsible for Stat5 activation. However, given the incomplete neutralization of the phospho-Stat5-inducing activity in CM by the anti-prolactin antibody tested, coupled with the fact that Jak2 can be activated by pathways other than ligand-bound Prlr, we sought further proof supporting this possibility. Therefore, we used mice constitutively deleted for Prl (Horseman et al. 1997) to definitively address whether Akt-induced autocrine prolactin expression in the mammary gland is responsible for Akt-induced Stat5 activation and mammary differentiation.

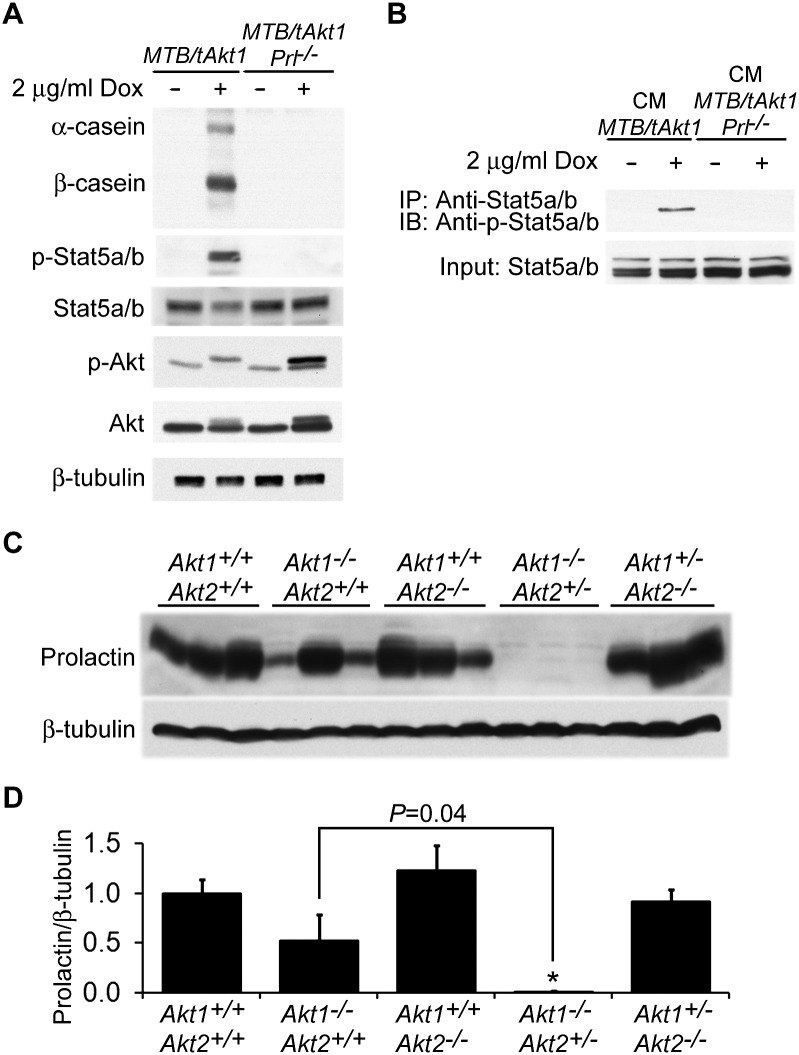

Akt activity was induced in explanted mammary glands from MTB/tAkt1;Prl−/− mice ex vivo by the addition of doxycycline to the culture medium. Despite the strong induction of myristoylated Akt expression in doxycycline-induced explanted mammary glands from MTB/tAkt1;Prl−/− mice, deletion of the Prl gene resulted in the abrogation of Akt-induced Stat5 activation as well as milk protein expression (Fig. 7A). Consistent with this, the ability of CM harvested from cultured MTB/tAkt1 mammary tissues to activate Stat5 when applied to HC11 cells was also completely abrogated by Prl deletion (Fig. 7B). Together, these findings demonstrate that Akt-induced Stat5 activation and mammary differentiation are mediated by the Akt-induced autocrine production of prolactin by the mammary gland.

Figure 7.

Prl is required for Akt1-mediated Stat5 activation and mammary differentiation. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of the indicated proteins in protein lysates from virgin MTB/tAkt1 and MTB/tAkt1;Prl−/− mammary tissues induced with doxycycline for 4 d ex vivo (+Dox) or untreated (−Dox). β-Tubulin levels served as a loading control. (B) Immunoblotting analysis of Stat5a/b immunoprecipitated from HC11 cells treated for 20 min with CM from MTB/tAkt1 and MTB/tAkt1;Prl−/− mammary tissues induced with doxycycline ex vivo. (C) Immunoblotting analysis of prolactin expression in the mammary glands of mice bearing the indicated Akt genotypes at day 18.5 of pregnancy. β-Tubulin served as a loading control. (D) Quantification of prolactin expression in the mammary glands of mice bearing the indicated Akt1 and Akt2 genotypes at day 18.5 of pregnancy (n = 6 per genotype) normalized to β-tubulin expression. Prolactin/β-tubulin ratios were normalized to those in wild-type mice. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− vs. wild type, (*) P < 0.001; Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− vs. Akt1−/−;Akt2+/+, P = 0.04, as indicated.

To extend these findings, we transplanted mammary epithelial fragments from MTB/tAkt1 or MTB mice into the cleared mammary fat pads of Prl−/− or Prl+/+ mice. After allowing 4 wk for ductal outgrowth, recipient mice were induced with doxycycline for 4 d. Examination of carmine-stained whole mounts confirmed that epithelial fragments from donor mice grew to a comparable extent in the fat pads of recipient Prl−/− or Prl+/+ mice (Supplemental Fig. S7A). Notably, induction of Akt in chimeric mammary glands composed of donor MTB/tAkt1-derived epithelium and either recipient Prl−/− or Prl+/+ stroma resulted in comparable levels of Stat5 activation and milk protein expression (Supplemental Fig. S7A,B). This demonstrates that Akt-induced Stat5 phosphorylation and mammary differentiation are due to autocrine prolactin production in the mammary epithelium and do not require prolactin produced by mammary stromal cells or other tissues.

Down-regulation of endogenous Akt in the mammary gland impairs the physiological production of autocrine prolactin

In light of our finding that Akt pathway activation is sufficient to induce the production of autocrine prolactin, we also wished to determine whether endogenous Akt is required for the physiological production of autocrine prolactin in the mammary gland. In particular, we sought to establish whether the Akt-induced production of autocrine prolactin plays a physiological role in mammary gland development. In support of this possibility, late-pregnant Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice exhibit a defect in mammary epithelial differentiation (Chen et al. 2010) that could ostensibly result from a defect in their ability to express autocrine prolactin. Indeed, immunoblotting revealed that autocrine prolactin expression was completely abrogated in the mammary glands of late-pregnant Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice (Fig. 7C,D). In contrast, pituitary prolactin mRNA expression and serum prolactin levels did not differ between Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− and control mice (Supplemental Fig. S8A; data not shown).

In agreement with our observation that Akt induced up-regulation of autocrine prolactin in MTB/tAkt1 mice occurs at the post-transcriptional level, prolactin mRNA expression levels were unchanged in the mammary glands of late-pregnant Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice compared with controls (Supplemental Fig. S8B). Moreover, consistent with the presence of normal phospho-Stat5 levels in the mammary glands of lactating—as opposed to late-pregnant—Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice, prolactin protein levels were comparable in the mammary glands of lactating Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− and wild-type mice (Supplemental Fig. S8C). In aggregate, our findings indicate that endogenous Akt activity is required for autocrine prolactin production in the mammary gland during late pregnancy.

In order to confirm that the defect in autocrine prolactin production and Stat5 activation observed in Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice at day 18.5 of pregnancy is due to deletion of Akt in the mammary gland rather than endocrine alterations caused by Akt deletion in other tissues, we transplanted Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− or wild-type mammary epithelial fragments into the cleared fat pads of 3-wk-old wild-type or Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice. After permitting 4 wk for ductal outgrowth, transplant recipients were set up for mating to collect mammary tissues at day 18.5 of pregnancy.

Analogous to our observations in intact Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice, whole-mount staining and histological analysis revealed that alveolar epithelium derived from Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mammary glands failed to differentiate during late pregnancy when transplanted into wild-type mice, whereas alveolar epithelium derived from the mammary glands of wild-type mice differentiated normally when transplanted into Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice (Supplemental Fig. S9A,B). In accordance with this, mammary prolactin expression, Stat5 activation, and expression of milk proteins were dramatically reduced in alveolar epithelium derived from Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− glands regardless of the genotype of the transplant recipient, whereas autocrine prolactin production, Stat5 activation, and milk protein expression occurred normally in wild-type alveolar epithelium transplanted into Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice (Supplemental Fig. S9C,D). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that Akt activation in the mammary epithelium is required for the production of autocrine prolactin, Stat5 activation, and mammary differentiation in a manner that is intrinsic to the mammary epithelium.

Discussion

Prolactin is classically viewed as an endocrine hormone whose multiple reproductive and metabolic functions depend on its delivery from the anterior pituitary, where it is produced, to peripheral target tissues via the circulation. In recent years, it has become evident that prolactin is also expressed in several extrapituitary tissues and cell types in humans, including the mammary gland as well as some breast and prostate cancer cell lines (Ben-Jonathan et al. 2008; Bernichtein et al. 2010). However, in contrast to our extensive understanding of the pleiotropic actions of endocrine prolactin, remarkably little is known about the physiological functions of autocrine prolactin in vivo or the pathways that regulate its production.

The pathways that regulate the synthesis and secretion of autocrine prolactin in vivo are almost entirely unknown, with the sole exception of studies demonstrating the estradiol-induced transcriptional up-regulation of autocrine prolactin in rat trigeminal neurons (Diogenes et al. 2006)—a mechanism analogous to that by which estradiol up-regulates prolactin transcription in pituitary lactotrophs—and androgen-dependent regulation of autocrine prolactin expression in the rat prostate (Nevalainen et al. 1997). We now report that the in vivo production of autocrine prolactin in the mammary gland is regulated by the Pten–Akt pathway. Conditional activation of the Akt pathway in the mammary epithelium of virgin mice by either Akt1 expression or Pten deletion rapidly induced the production of autocrine prolactin. In contrast to findings in rat trigeminal neurons, Akt-induced up-regulation of autocrine prolactin occurred at the post-transcriptional level, revealing a previously unsuspected mechanism for the induction of prolactin protein expression.

Analogous to the paucity of information regarding the regulation of autocrine prolactin expression, little information currently exists regarding its physiological functions. While autocrine prolactin mRNA expression has been demonstrated in a variety of normal tissues, including the uterus, skin, white fat, and placenta (Ben-Jonathan et al. 2008; Bernichtein et al. 2010), no function for autocrine prolactin produced by these tissues has been demonstrated either in vivo or in vitro.

Autocrine prolactin mRNA expression in the mammary gland has been detected in late-pregnant and lactating rats (Kurtz et al. 1993; Steinmetz et al. 1993; Iwasaka et al. 2000; Ben-Jonathan et al. 2008). In this regard, the sole report of a function for autocrine prolactin in a normal tissue arises from studies comparing proliferation rates in recombined mouse mammary glands composed of either Prl−/− or Prl+/+ epithelium transplanted into wild-type mammary stroma. These studies identified a 2.8-fold lower level of alveolar epithelial proliferation at parturition in the absence of any detectable morphological alterations in glands derived from Prl−/− mice (Naylor et al. 2003). The impact of prolactin deletion on epithelial differentiation was not investigated. At present, this role in proliferation at the time of parturition constitutes the only defined physiological function for autocrine prolactin in normal tissues (Bernichtein et al. 2010).

We now report that autocrine prolactin produced by mammary epithelial cells is required for their terminal differentiation during late pregnancy as well as the initiation of lactation at parturition, a critical developmental transition essential for energy output to support survival of mammalian offspring. Conditional activation of the Akt pathway in the mammary glands of virgin mice by either Akt1 expression or Pten deletion rapidly induced terminal mammary epithelial differentiation accompanied by the synthesis of milk despite the absence of lobuloalveolar development. Mammary differentiation was due to the Akt-dependent synthesis and secretion of autocrine prolactin and downstream activation of the Prlr–Jak–Stat5 pathway. Consistent with the Akt-dependent secretion of autocrine prolactin, cells treated with CM from mammary glands in which Akt had been activated underwent rapid Stat5 phosphorylation in a manner that was blocked by treatment with an anti-Prl antibody, inhibition of Jak2, or deletion of the prolactin gene. Furthermore, Akt-induced mammary differentiation was abrogated in Prl−/−, Prlr−/−, and Stat5−/− mice.

Supporting a physiological requirement for autocrine prolactin during development, the mammary glands of lactation-defective Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice failed to express autocrine prolactin or activate Stat5 during late pregnancy despite normal levels of serum and pituitary prolactin, resulting in a failure to initiate secretory activation or appropriately up-regulate the production of milk proteins, lactose, and lipids. In further support of a mammary epithelial-intrinsic mechanism of action, Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mammary epithelial fragments transplanted into wild-type mice failed to activate Stat5 and exhibited defective mammary differentiation during late pregnancy, whereas wild-type mammary epithelium transplanted into Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− recipients activated Stat5 and differentiated normally. In aggregate, our findings demonstrate that Akt pathway activation is necessary and sufficient to induce autocrine prolactin production, Stat5 activation, and terminal mammary epithelial differentiation, even in the absence of the developmental program that normally prepares the mammary gland for lactation. Together, these findings reveal a function for autocrine prolactin in mammary differentiation, demonstrate its endogenous regulation by the PI3K–Akt pathway, and provide a direct link between Akt activation and the Jak–Stat5 pathway.

Notably, the requirement for PI3K–Akt pathway activity for autocrine prolactin production as well as the requirement for autocrine prolactin itself in mammary epithelial differentiation appears to be specific to late pregnancy and parturition, since lactating Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice exhibit normal mammary differentiation characterized by normal levels of autocrine mammary prolactin, milk production, and Stat5 activity (Supplemental Fig. S8C; data not shown). As such, our data indicate that autocrine prolactin is required for activation of the Jak2–Stat5 pathway during a specific development stage of pregnancy at which pituitary prolactin is unable to provide this function.

It is intriguing that pituitary prolactin fails to compensate for the loss of local prolactin production in Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice during late pregnancy. Serum prolactin levels in rats fluctuate during the first half of pregnancy with daily nocturnal and diurnal surges, whereas pituitary prolactin is suppressed thereafter by rising levels of placental lactogen I (Ben-Jonathan et al. 2008; Bernichtein et al. 2010). If the release of pituitary prolactin is similarly suppressed in mice during the second half of pregnancy, low circulating levels of prolactin may be insufficient to induce sustained Stat5 activation in Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice, which are relatively resistant to prolactin-induced Stat5 activation due to decreased expression of the positive regulator of Prlr–Jak–Stat5 signaling (Id2) and increased expression of the negative regulators of Prlr–Jak–Stat5 signaling (caveolin-1 and Socs2) (Chen et al. 2010). As such, local prolactin production may be required to overcome this resistance.

Given the dramatic morphological changes that occur in the rodent mammary gland during the 3-wk period of pregnancy to prepare for lactation, it is striking that activated Akt1 can effect similar changes in the mammary glands of virgin mice within 4 d. Importantly, mammary epithelial differentiation induced by Akt activation is not merely an artifact of gross overexpression of an Akt transgene, as virgin mice deleted for mammary epithelial Pten also underwent mammary epithelial differentiation as a consequence of autocrine prolactin production. Presumably, the greater extent of mammary epithelial differentiation induced by expression of an activated Akt transgene than by Pten deletion reflects the more pronounced activation of Akt by expression of exogenous myr-Akt than by activation of endogenous Akt via Pten deletion.

Notably, our results indicate that, even in the absence of hormones of pregnancy or lobuloalveolar development, Akt activation is sufficient to drive the terminal differentiation of mammary ductal epithelium, resulting in large-scale synthesis of milk proteins, lipid, and lactose within 96 h. This is particularly striking given that β-casein is normally not expressed in ducts until day 18.5 of pregnancy, although it is expressed in alveoli beginning at day 6.5 of pregnancy. Indeed, Akt1 activation was sufficient in virgin mice to up-regulate the expression of a series of genes whose expression is normally not up-regulated until the onset of secretory activation at the initiation of lactation, including α-lactalbumin, butyrophilin, xanthine oxidoreductase, MUC1, ɛ-casein, Aldoc, and Elovl5 (Anderson et al. 2007). This highlights the powerful regulatory role that the Akt pathway plays in secretory activation. Together, our data demonstrate that PI3K–Akt activation rapidly induces terminal mammary epithelial differentiation and milk synthesis in the absence of the lobuloalveolar development during pregnancy that is normally required for efficient lactation at parturition. As such, the ability of Akt to rapidly drive terminal mammary epithelial differentiation and milk synthesis in virgin mice highlights the ability of Akt to serve as a powerful upstream regulatory molecule in the developmental program leading to lactation.

Our findings in this study identify autocrine prolactin as a direct mechanism by which PI3K/Akt activation can result in Prlr–Jak2–Stat5 pathway activation. Each of these pathways controls multiple overlapping cellular processes, including proliferation, survival, and metabolism, through common as well as distinct downstream effectors. In this regard, comparison of Akt-induced gene expression in wild-type mice versus mice homozygous for mutations in Prlr or Stat5a/b provides a means to identify those Akt-induced expression changes that require the Prlr–Jak–Stat5 pathway. For example, we found that Akt-induced up-regulation of Glut1, Elf5, and Id2—as well as autocrine prolactin itself—did not require intact Prlr–Jak–Stat5 signaling. In contrast, the Prlr–Jak–Stat5 pathway was required to mediate the effects of Akt on milk protein gene expression, lactose synthesis, lipid synthesis, and Npt2b up-regulation as well as down-regulation of NKCC1, caveolin-1, and Socs2. These findings suggest that the Prlr–Jak–Stat5 pathway mediates many, but not all, of the effects of Akt on mammary epithelial differentiation and secretory activation.

The Ets transcription factor Elf5 has been proposed to provide a link between prolactin signaling and lobuloalveolar development in the mammary gland (Zhou et al. 2005; Harris et al. 2006; Oakes et al. 2008). Elf5 expression is up-regulated during pregnancy and lactation and has been shown to be essential for alveolar development and lactation due to its regulation of the CD61+ progenitor cell population. Overexpression of Elf5 in inducible transgenic mice using the same MMTV-rtTA (MTB) mouse model used here resulted in modest increases in β-casein and Wap mRNA expression after 3 wk of induction (Oakes et al. 2008). In addition, re-expression of Elf5 in Prlr nullizygous mammary epithelium restored alveolar development, demonstrating that Elf5 is capable of substituting for at least the proliferative effects of prolactin signaling (Harris et al. 2006). However, the nature of the retroviral transplantation model used in this study precluded assessment of whether Elf5 is capable of substituting for the differentiative and lactogenic effects of prolactin during secretory activation (Harris et al. 2006).

Our previous observation that elevated Elf5 expression is maintained in Akt1−/−;Akt2+/− mice despite their inability to terminally differentiate or lactate (Chen et al. 2010) suggested that the requirement for Akt in mammary differentiation and the establishment of lactation are not dependent on Elf5. Supporting this hypothesis, in the present study, we found that Elf5 expression was robustly induced by Akt1 in the mammary glands of virgin Stat5a/b−/− and Prlr−/− mice despite the inability of Akt to activate Stat5 or induce differentiation in these mice (Supplemental Fig. S10). This indicates that Akt is an upstream transcriptional regulator of Elf5 in a manner that does not require Prlr–Jak–Stat5 signaling and that Elf5 expression alone is not sufficient to substitute for the differentiative effects of Prlr signaling during secretory activation. In aggregate, our findings indicate that the ability of Akt to induce terminal mammary epithelial differentiation and secretory activation is due to its ability to stimulate autocrine prolactin production and activate Stat5, rather than its ability to up-regulate Elf5.

Notably, beyond normal mammary epithelial cells, autocrine prolactin is also synthesized and secreted by some human breast cancer cell lines (Ginsburg and Vonderhaar 1995) and has been identified in human breast cancers (Clevenger et al. 2003). As such, it has been proposed to play a direct role in mammary tumorigenesis that may be distinct from any roles played by endocrine prolactin secreted from the pituitary gland (Bernichtein et al. 2010). For example, during cancer progression, autocrine prolactin may provide locally derived mitogenic and prosurvival stimuli as well as induce cell migration and facilitate angiogenesis (Clevenger et al. 2003; Wagner and Rui 2008). However, to date, no functional in vivo evidence exists demonstrating a role for autocrine prolactin in the growth of mammary tumors in either xenograft or autochthonous mouse models. In this regard, our observations identifying the PI3K–Akt pathway as an upstream regulator of autocrine prolactin production has intriguing potential implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of human cancer, since the PI3K–Akt pathway is one of the most common activated oncogenic pathways in human cancer (Altomare and Testa 2005). As sustained Akt activation may regulate multiple cellular processes through Stat5 signaling, this study raises the possibility that autocrine prolactin may play a role in cancer progression. Further characterization of the relationship between the Akt and Prlr–Jak–Stat5 pathways will be required in order to determine whether therapeutic approaches aimed at blocking the interaction between these pathways will be beneficial in the treatment of human cancers.

Materials and methods

Animals

Ptenfl/fl (Groszer et al. 2001) and Prlr−/− (Ormandy et al. 1997) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Stat5a/b−/− and Prl−/− mice were obtained from Dr. James Ihle (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital) and Dr. Nelson Horseman (University of Cincinnati), respectively (Horseman et al. 1997; Teglund et al. 1998). Mice were backcrossed onto the FVB background prior to experimental use (Ptenfl/fl: N6; Prlr−/−: N17; Stat5a/b−/−: N10; and Prl−/−: N5). Akt1−/− and Akt2−/− mice were provided by Dr. Morris Birnbaum (University of Pennsylvania) (Cho et al. 2001a,b). MMTV/rtTA;TetO-Akt1 (MTB/tAkt1) mice expressing myrAkt1 in a mammary epithelial-specific manner were generated by crossing tAkt1 mice provided by Dr. Craig Thompson (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center) and Dr. Jeffrey Rathmell (Duke University) with MMTV-rtTA (MTB) mice as previously described (Gunther et al. 2002; Boxer et al. 2006). TetO-TurboCre (TTC1) mice were generated by transgenic injection of a plasmid in which the Turbo-Cre recombinase coding region (gift of Dr. Timothy Ley, Washington University School of Medicine) was subcloned downstream from the tet operator in TMILA (Gunther et al. 2003).

For timed pregnancies, the morning of the observed virginal plug was counted as day 0.5. To induce expression of Akt1 protein, 6-wk-old virgin animals were treated with 2 mg/mL doxycycline in their drinking water for 4 d. Mice were sacrificed, and mammary tissue was harvested for analysis at the indicated time points.

Mammary gland culture and isolation of mammary epithelia and adipose tissue

The number 5 inguinal glands and the proximal portion of the number 4 inguinal glands of 6-wk-old MTB/tAkt1, MTB/tAkt1;Prl−/−, MTB/tAkt1;Prlr−/−, and MTB/tAkt1;Stat5a/b−/− mice were harvested and minced to yield <2-mm fragments for mammary gland culture as modified from a previously described method (Plaut et al. 1993). Tissues were incubated in Waymouth's base medium (Invitrogen) containing 20 mM HEPES, 4 mM glutamine, 5 μg/mL insulin, and 1 μg/mL hydrocortisone.

To isolate mammary epithelial and adipose compartments, the number five inguinal glands and the proximal portion of the number four inguinal glands of 6-wk-old MTB and MTB/tAkt1 mice induced with doxycycline were incubated in a digestion solution consisting of 2 μg/mL doxycycline, 5% calf serum, 2 mg/mL collagenase A, 100 U/mL hyaluronidase, and DMEM base medium (Invitrogen) for 1.5 h at 37°C. After lysis of red blood cells in NH4Cl, digested tissues were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 min and washed three times in PBS. Mammary epithelial and adipose fractions were collected in the pellet and the top layer of solution, respectively, and examined under a microscope to verify the purity of the cells.

Transplantation of mammary tissue and primary mammary epithelial cells

To generate cleared fat pads, the proximal portion of the number four inguinal gland containing the rudimentary mammary epithelial tree of 3-wk-old recipient mice was removed as described (Humphreys et al. 1997). Subsequently, mammary tissues harvested from the proximal portion of the number four inguinal mammary glands of 3-wk-old donor mice were implanted into the cleared fat pads of recipient mice. To reduce variation between recipient mice, control mammary tissues were transplanted into the contralateral cleared fat pad. Prior to sacrificing recipient mice at 4 wk post-transplantation, mice were induced with 2 mg/mL doxycycline for 4 d or set up for mating. Engrafted mammary glands were harvested for whole-mount and histological analyses or frozen for immunoblotting analysis.

Primary mammary epithelial cells (4.5 × 105) freshly isolated as described above from MTB/tAkt1 mice were resuspended in 50 μL of 30% Matrigel in PBS and injected into the cleared fat pads of 3-wk-old wild-type recipient mice. Contralateral fat pads were injected with control MTB mammary epithelial cells. Six weeks post-transplantation, mice were induced with 2 mg/mL doxycycline for 4 d, and reconstituted mammary glands were harvested for analysis.

Morphological analysis

Whole-mount, histological, and immunofluorescence analyses of inguinal mammary glands were performed as described (Gunther et al. 2002; Boxer et al. 2006). The following primary antibodies were used: Glut1 (1:5000; provided by Dr. Morris Birnbaum, University of Pennsylvania), NKCC1 (1:1000; provided by Dr. Jim Turner, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research), Npt2b (1:300; provided by Dr. Jurg Biber, University of Zurich), cytokeratin 8 (1:100; Developmental Study Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA), β-casein (1:20; provided by Dr. Mina Bissell, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA), phospho-Akt (Ser473, 1:50) and Pten (1:100; Cell Signaling Technology), and phospho-Stat5a/b (Tyr694/Tyr699, 1:50; Upstate Biotechnology). Stained sections were examined using a Leica microscope (model DM5000B, Leica Microsystems) equipped with a digital camera (Leica DFC350FX).

Immunoblotting and Prl neutralization

Immunoblotting analysis was performed as described (Boxer et al. 2006). The following primary antibodies were used: phospho-Akt (Ser473; 1:1000), Akt (1:1000), and phospho-Stat5a/b (Tyr694/Tyr699, 1:1000) from Cell Signaling Technology; phospho-Stat5a/b (Tyr694/Tyr699, 1:500) and adiponectin (1:1000) from Millipore; mouse milk-specific proteins (1:20,000) from Nordic Immunological Laboratories; β-tubulin (1:1000) from BioGenex; Stat5a/b (1:500) from BD Biosciences; E-cadherin (1:500) from Zymed Laboratories; and Stat5a/b (2 μg for immunoprecipitation), prolactin (1:200), and β-actin (1:1000) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

The anti-mouse prolactin antibody used to neutralize CM was obtained from R&D Systems. The Jak2 inhibitor NVP-BSK805 (Baffert et al. 2010) was provided by Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research.

Analysis of cytokines and lactose

Serum prolactin was measured by a mouse prolactin ELISA kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (RayBiotech). CM from MTB/tAkt1 mammary tissues treated or not treated with 2 μg/mL doxycycline for 4 d in vitro were harvested and passed through a 0.45-μm filter, followed by concentration using an Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal device with 3-kDa cut point.

Lactose in the mammary gland was measured by using the lactose assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (MBL International).

RNA analysis

Total RNA isolation from snap-frozen tissues, preparation of radioactively labeled cDNA probes, Northern blotting, in situ hybridization, and quantitative RT–PCR analysis were performed as described (Marquis et al. 1995; Chen et al. 2010). The cDNA probe for Northern hybridization detection of Prl corresponded to nucleotides 31–836. The exposure time for in situ hybridization experiments was 2 d. TaqMan-based probes for quantitative RT–PCR were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Probes used were β-casein Mm00839664_m1, Wap Mm00839913_m1, α-lactalbumin Mm00495258_m1, ɛ-casein Mm00839674_m1, Aldoc Mm01298111_g1, Fads1 Mm00507605_m1, Elovl5 Mm00506717_m1, Tbp Mm00446973_m1, and cytokeratin 18 Mm01601706_g1. Statistical analysis was calculated by a two-tailed Student's t-test.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Craig Thompson, Morris Birnbaum, and Jeff Rathmell for reagents and advice, and the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research for NVP-BSK805. This research was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute, the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program, and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.197343.112.

References

- Acosta JJ, Munoz RM, Gonzalez L, Subtil-Rodriguez A, Dominguez-Caceres MA, Garcia-Martinez JM, Calcabrini A, Lazaro-Trueba I, Martin-Perez J 2003. Src mediates prolactin-dependent proliferation of T47D and MCF7 cells via the activation of focal adhesion kinase/Erk1/2 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways. Mol Endocrinol 17: 2268–2282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altomare DA, Testa JR 2005. Perturbations of the AKT signaling pathway in human cancer. Oncogene 24: 7455–7464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SM, Rudolph MC, McManaman JL, Neville MC 2007. Key stages in mammary gland development. Secretory activation in the mammary gland: It's not just about milk protein synthesis! Breast Cancer Res 9: 204 doi: 10.1186/bcr1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baffert F, Regnier CH, De Pover A, Pissot-Soldermann C, Tavares GA, Blasco F, Brueggen J, Chene P, Drueckes P, Erdmann D, et al. 2010. Potent and selective inhibition of polycythemia by the quinoxaline JAK2 inhibitor NVP-BSK805. Mol Cancer Ther 9: 1945–1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Jonathan N, LaPensee CR, LaPensee EW 2008. What can we learn from rodents about prolactin in humans? Endocr Rev 29: 1–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernichtein S, Touraine P, Goffin V 2010. New concepts in prolactin biology. J Endocrinol 206: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bole-Feysot C, Goffin V, Edery M, Binart N, Kelly PA 1998. Prolactin (PRL) and its receptor: Actions, signal transduction pathways and phenotypes observed in PRL receptor knockout mice. Endocr Rev 19: 225–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer RB, Stairs DB, Dugan KD, Notarfrancesco KL, Portocarrero CP, Keister BA, Belka GK, Cho H, Rathmell JC, Thompson CB, et al. 2006. Isoform-specific requirement for Akt1 in the developmental regulation of cellular metabolism during lactation. Cell Metab 4: 475–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti P, Henry MK, Quelle FW 2005. Prolactin and heregulin override DNA damage-induced growth arrest and promote phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase-dependent proliferation in breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol 26: 509–514 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Boxer RB, Stairs DB, Portocarrero CP, Horton RH, Alvarez JV, Birnbaum MJ, Chodosh LA 2010. Akt is required for Stat5 activation and mammary differentiation. Breast Cancer Res 12: R72 doi: 10.1186/bcr2640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Mu J, Kim JK, Thorvaldsen JL, Chu Q, Crenshaw EB 3rd, Kaestner KH, Bartolomei MS, Shulman GI, Birnbaum MJ 2001a. Insulin resistance and a diabetes mellitus-like syndrome in mice lacking the protein kinase Akt2 (PKBβ). Science 292: 1728–1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Thorvaldsen JL, Chu Q, Feng F, Birnbaum MJ 2001b. Akt1/PKBα is required for normal growth but dispensable for maintenance of glucose homeostasis in mice. J Biol Chem 276: 38349–38352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevenger CV, Furth PA, Hankinson SE, Schuler LA 2003. The role of prolactin in mammary carcinoma. Endocr Rev 24: 1–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Riedlinger G, Miyoshi K, Tang W, Li C, Deng CX, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L 2004. Inactivation of Stat5 in mouse mammary epithelium during pregnancy reveals distinct functions in cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 24: 8037–8047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diogenes A, Patwardhan AM, Jeske NA, Ruparel NB, Goffin V, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM 2006. Prolactin modulates TRPV1 in female rat trigeminal sensory neurons. J Neurosci 26: 8126–8136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furth PA, Nakles RE, Millman S, Diaz-Cruz ES, Cabrera MC 2011. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 as a key signaling pathway in normal mammary gland developmental biology and breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 13: 220 doi: 10.1186/bcr2921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg E, Vonderhaar BK 1995. Prolactin synthesis and secretion by human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 55: 2591–2595 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groszer M, Erickson R, Scripture-Adams DD, Lesche R, Trumpp A, Zack JA, Kornblum HI, Liu X, Wu H 2001. Negative regulation of neural stem/progenitor cell proliferation by the Pten tumor suppressor gene in vivo. Science 294: 2186–2189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther EJ, Belka GK, Wertheim GB, Wang J, Hartman JL, Boxer RB, Chodosh LA 2002. A novel doxycycline-inducible system for the transgenic analysis of mammary gland biology. FASEB J 16: 283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther EJ, Moody SE, Belka GK, Hahn KT, Innocent N, Dugan KD, Cardiff RD, Chodosh LA 2003. Impact of p53 loss on reversal and recurrence of conditional Wnt-induced tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 17: 488–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Stanford PM, Sutherland K, Oakes SR, Naylor MJ, Robertson FG, Blazek KD, Kazlauskas M, Hilton HN, Wittlin S, et al. 2006. Socs2 and elf5 mediate prolactin-induced mammary gland development. Mol Endocrinol 20: 1177–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennighausen L, Robinson GW 2005. Information networks in the mammary gland. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 715–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horseman ND, Zhao W, Montecino-Rodriguez E, Tanaka M, Nakashima K, Engle SJ, Smith F, Markoff E, Dorshkind K 1997. Defective mammopoiesis, but normal hematopoiesis, in mice with a targeted disruption of the prolactin gene. EMBO J 16: 6926–6935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys RC, Lydon J, O'Malley BW, Rosen JM 1997. Mammary gland development is mediated by both stromal and epithelial progesterone receptors. Mol Endocrinol 11: 801–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaka T, Umemura S, Kakimoto K, Koizumi H, Osamura YR 2000. Expression of prolactin mRNA in rat mammary gland during pregnancy and lactation. J Histochem Cytochem 48: 389–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones FE, Stern DF 1999. Expression of dominant-negative ErbB2 in the mammary gland of transgenic mice reveals a role in lobuloalveolar development and lactation. Oncogene 18: 3481–3490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones FE, Welte T, Fu XY, Stern DF 1999. ErbB4 signaling in the mammary gland is required for lobuloalveolar development and Stat5 activation during lactation. J Cell Biol 147: 77–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz A, Bristol LA, Toth BE, Lazar-Wesley E, Takacs L, Kacsoh B 1993. Mammary epithelial cells of lactating rats express prolactin messenger ribonucleic acid. Biol Reprod 48: 1095–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Robinson GW, Wagner KU, Garrett L, Wynshaw-Boris A, Hennighausen L 1997. Stat5a is mandatory for adult mammary gland development and lactogenesis. Genes Dev 11: 179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long W, Wagner KU, Lloyd KC, Binart N, Shillingford JM, Hennighausen L, Jones FE 2003. Impaired differentiation and lactational failure of Erbb4-deficient mammary glands identify ERBB4 as an obligate mediator of STAT5. Development 130: 5257–5268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis ST, Rajan JV, Wynshaw-Boris A, Xu J, Yin GY, Abel KJ, Weber BL, Chodosh LA 1995. The developmental pattern of Brca1 expression implies a role in differentiation of the breast and other tissues. Nat Genet 11: 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi K, Shillingford JM, Smith GH, Grimm SL, Wagner KU, Oka T, Rosen JM, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L 2001. Signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat) 5 controls the proliferation and differentiation of mammary alveolar epithelium. J Cell Biol 155: 531–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Nishikawa SI, Yokota Y 2000. Lactation defect in mice lacking the helix-loop-helix inhibitor Id2. EMBO J 19: 5772–5781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor MJ, Lockefeer JA, Horseman ND, Ormandy CJ 2003. Prolactin regulates mammary epithelial cell proliferation via autocrine/paracrine mechanism. Endocrine 20: 111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevalainen MT, Valve EM, Ahonen T, Yagi A, Paranko J, Harkonen PL 1997. Androgen-dependent expression of prolactin in rat prostate epithelium in vivo and in organ culture. FASEB J 11: 1297–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes SR, Naylor MJ, Asselin-Labat ML, Blazek KD, Gardiner-Garden M, Hilton HN, Kazlauskas M, Pritchard MA, Chodosh LA, Pfeffer PL, et al. 2008. The Ets transcription factor Elf5 specifies mammary alveolar cell fate. Genes Dev 22: 581–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormandy CJ, Camus A, Barra J, Damotte D, Lucas B, Buteau H, Edery M, Brousse N, Babinet C, Binart N, et al. 1997. Null mutation of the prolactin receptor gene produces multiple reproductive defects in the mouse. Genes Dev 11: 167–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Permyakov EA, Berliner LJ 2000. α-Lactalbumin: Structure and function. FEBS Lett 473: 269–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaut K, Ikeda M, Vonderhaar BK 1993. Role of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I in mammary development. Endocrinology 133: 1843–1848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillingford JM, Miyoshi K, Flagella M, Shull GE, Hennighausen L 2002a. Mouse mammary epithelial cells express the Na-K-Cl cotransporter, NKCC1: Characterization, localization, and involvement in ductal development and morphogenesis. Mol Endocrinol 16: 1309–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillingford JM, Miyoshi K, Robinson GW, Grimm SL, Rosen JM, Neubauer H, Pfeffer K, Hennighausen L 2002b. Jak2 is an essential tyrosine kinase involved in pregnancy-mediated development of mammary secretory epithelium. Mol Endocrinol 16: 563–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillingford JM, Miyoshi K, Robinson GW, Bierie B, Cao Y, Karin M, Hennighausen L 2003. Proteotyping of mammary tissue from transgenic and gene knockout mice with immunohistochemical markers: A tool to define developmental lesions. J Histochem Cytochem 51: 555–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz RW, Grant AL, Malven PV 1993. Transcription of prolactin gene in milk secretory cells of the rat mammary gland. J Endocrinol 136: 271–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teglund S, McKay C, Schuetz E, van Deursen JM, Stravopodis D, Wang D, Brown M, Bodner S, Grosveld G, Ihle JN 1998. Stat5a and Stat5b proteins have essential and nonessential, or redundant, roles in cytokine responses. Cell 93: 841–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KU, Rui H 2008. Jak2/Stat5 signaling in mammogenesis, breast cancer initiation and progression. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 13: 93–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KU, Krempler A, Triplett AA, Qi Y, George NM, Zhu J, Rui H 2004. Impaired alveologenesis and maintenance of secretory mammary epithelial cells in Jak2 conditional knockout mice. Mol Cell Biol 24: 5510–5520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RA, Vadlamudi RK, Bagheri-Yarmand R, Beuvink I, Hynes NE, Kumar R 2003. Essential functions of p21-activated kinase 1 in morphogenesis and differentiation of mammary glands. J Cell Biol 161: 583–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Chehab R, Tkalcevic J, Naylor MJ, Harris J, Wilson TJ, Tsao S, Tellis I, Zavarsek S, Xu D, et al. 2005. Elf5 is essential for early embryogenesis and mammary gland development during pregnancy and lactation. EMBO J 24: 635–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]