Abstract

Introduction

The endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke has been revolutionized in the past years by the introduction of new devices for mechanical thrombectomy. Several tools were already available in 2008. The majority allowed the recanalization of acutely occluded intracranial arteries with acceptable levels of safety and efficacy, and with occasional failures.

Case presentation

On 3 March 2008, a 67-year-old woman was treated 3.5 h after the clinical onset of a right hemispheric stroke due to an embolic middle cerebral artery (MCA) M1 occlusion. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score prior to treatment was 10. Mechanical thrombectomy with a microbrush yielded a significant amount of thrombotic material without recanalization. Given the urgency of the situation, the uncertain outcome in the case of a persistent occlusion of the right M1 segment and the fact that no other device was available, a Solitaire stent was deployed within the occluded right M1 segment. After several minutes of incubation, the expanded stent was slowly withdrawn under continuous aspiration with instantaneous removal of the entire thrombus and complete recanalization of the right MCA with reperfusion of the whole MCA supply territory. Digital subtraction angiography showed neither peripheral emboli nor vasospasm. The patient made a complete clinical recovery with an NIHSS score of 0 at the 30 day follow-up.

Conclusion

The Solitaire stent was initially developed for the endovascular treatment of wide necked intracranial aneurysms but has been demonstrated to be safe and efficacious for intracranial thrombectomy. This was the first successful human clinical use of a Solitaire stent for this purpose and the ignition spark for the development of a whole generation of new devices, now called stent retrievers.

Introduction

Early recanalization of occluded vessels in acute ischemic stroke by intravenous thrombolysis or endovascular recanalization is associated with improved clinical outcome and reduced mortality.1 The concept of endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke was initially based on the local injection of fibrinolytic agents.2 Clinical benefits of local intra-arterial fibrinolysis (LIF) were reported in case series and from controlled trials.3 The method was, however, not further developed when a series of randomized controlled trials of intravenous fibrinolysis (IVF) versus placebo4–7 led to the approval of the recombinant tissue plasminogen activator alteplase for use in ischemic stroke within 3 h of symptom onset. The difference between the two arms in these studies was quite sobering and <15% of all stroke patients were eligible for IVF. The general acceptance of IVF, however, was pivotal in anchoring acute ischemic stroke in neurology and was instrumental for the installation of dedicated stroke units. Apart from these merits, the practice of IVF undermined the momentum of further development of endovascular treatment concepts. The first dedicated tool approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2004 for endovascular intracranial thrombectomy was the Merci retriever (Concentric Medical, Mountain View, California, USA), a nitinol spiral. In 2005, Catch (Balt Extrusion, Montmorency, France), a braided nitinol basket proximally attached to a wire and distally occluded, was CE marked (CE=Conformité Européenne, the CE logo indicates free marketability of an industrial product within the European Economic Area) in Europe for the same indication. Both devices were limited in their efficacy and had some safety issues. The Merci retriever was evaluated in large US trials8 and achieved a certain acceptance both in the USA and in Europe. Competing developments were brushes and braided cages for intracranial thrombectomy.9 In 2006, Penumbra (Alameda, USA) came up with an aspiration catheter together with a dedicated aspiration pump and a modified wire (‘separator’). The Penumbra system was shown to be both efficacious and safe for endovascular intracranial thrombectomy in European and US trials and received FDA approval in 2008.10

In 2003, completely independent of the efforts on engineering stroke devices, a new stent for the endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms was developed by Dendron (Bochum, Germany).11 This stent received the CE mark in 2004. Dendron was acquired by MTI (Irvine, California, USA) in 2002. The Solitaire stent, now manufactured and distributed by ev3 (Irvine, California, USA), became available for the treatment of wide necked aneurysms in Europe in December 2007.

This was the situation when we treated a patient with an acute embolic M1 occlusion in March 2008 and by chance made the observation described below. Starting from this point and with immediate enthusiasm of other colleagues, it became apparent that a new era of the endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke had begun. Here we describe the first successful usage of a Solitaire stent as a device for clot retrieval (‘mechanical thrombectomy’) from an acutely occluded intracranial human artery.

Case presentation

This 67-year-old woman presented on 3 March 2008 at 16:00 to the neurological emergency room. Earlier that day (at 14:50), her relatives had witnessed the acute onset of a fluctuating paresis of her left arm and leg. Diffusion weighted MR images, carried out at 16:30, revealed an area of restricted diffusion in the right basal ganglia and the deep periventricular white matter and an MR angiogram demonstrated complete occlusion of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) in the M1 segment. The emergency stroke team decided to initiate intravenous thrombolysis, which started within a 2 h window (16:45). As the patient did not show any clinical improvement within the next 30 min, the attending stroke physician decided to proceed with a bridging concept and endovascular treatment was initiated, after the patient was informed of the proposed procedure. This information included a description of the procedure, the potential risks and benefits and an explanation that extensions of the procedure (eg, surgical craniectomy) or the off-label use of medical devices (eg, coronary stents, etc) might become necessary. The patient gave informed consent to the operator. The neurological examination before digital subtraction angiography (DSA) showed a severe dysarthria and a left-sided hemiplegia with facial nerve palsy (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 10). The emergent angiography began 3 h and 20 min after the onset of symptoms and the first DSA run was recorded at 18:12.

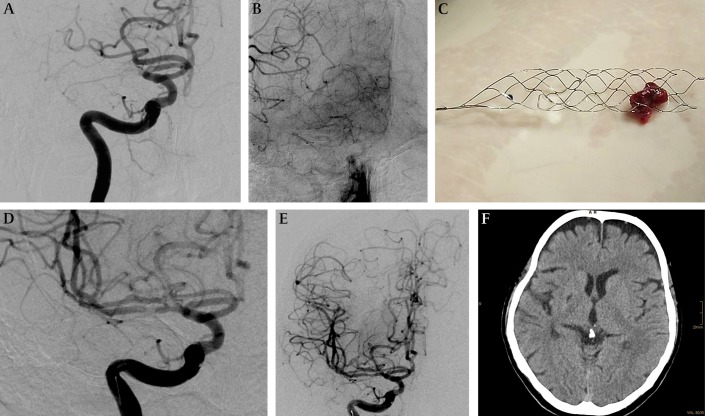

Using a 4 F diagnostic catheter, selective injection of both vertebral arteries and internal carotid arteries (ICAs) was carried out to show the extent of leptomeningeal collaterals and to rule out distal emboli, eventually not visible on MR angiography. Complete embolic occlusion of the right MCA at the M1 segment with moderate leptomeningeal collaterals between the right anterior cerebral artery and MCA was confirmed (figure 1A,B).

Figure 1.

Embolic occlusion of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA), treated by mechanical thrombectomy using a Solitaire stent. (A) Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) with injection of the right internal carotid artery (ICA) shows embolic occlusion of the right M1 segment. (B) In the late phase of this DSA run with injection of the right ICA, the leptomeningeal collaterals between the right anterior and MCA were visualized. (C) Solitaire stent loaded with thrombus, which was removed from the right M1 segment. (D, E) DSA with injection of the right ICA after Solitaire thrombectomy confirms the recanalization of the short M1 and both M2 segments (D, magnified view) without vasospasm or distal emboli (E, whole head run). There might be a minor remnant of the previously occluding thrombus in the inferior trunk to the MCA/M2 (D). (F) CT 22 months after the Solitaire thrombectomy of the right MCA shows a small post-ischemic scar of the right basal ganglia.

Systemic anticoagulation with 5000 U of heparin was initiated. Via a 6 F Envoy guiding catheter (Cordis, Miami, USA) in the right ICA, a straight Rebar27 was gently advanced to the thrombus under the guidance of a SilverSpeed16 microguidewire (both ev3). Under road map, a thrombectomy brush (pCR, phenox; Bochum, Germany) was deployed in the right angular artery and subsequently slowly withdrawn under continuous aspiration. The brush was loaded with clot material but no recanalization of the target vessel was observed (TICI 1). During the catheterization, the thrombus appeared organized and firm. The chances of success of either LIF or repeated pCR passages were considered low as previous experience has shown very low recanalization rates with pCR and LIF in firm organized emboli. It appeared evident to the operator (HH) that in this situation, more interaction between clot and retrieval device was required. While contemplating the use of either a Catch or a Merci retriever (at this time the only other approved devices for mechanical thrombectomy), we recognized that neither of these tools was in stock. After balancing the potential risks and benefits to this patient and given the uncertain outcome if there was no recanalization, we decided to use a Solitaire stent in the way we would have otherwise used a Catch or a Merci device. The right angular artery was again gently catheterized with a Rebar18 catheter. After removal of the microguidewire, a self-expanding Solitaire stent (4 mm diameter, 20 mm length) was inserted under continuous slow flush with saline solution to the distal end of the microcatheter and was deployed by slowly pulling back the microcatheter. Correct deployment of the Solitaire stent over the whole length of the thrombus was observed under continuous fluoroscopy. In order to avoid mechanically induced vasospasm, 2 mg of glycerin trinitrate were injected intra-arterially. After several minutes of incubation and with the rotating hemostatic valve tightly closed, a 50 ml Luer lock syringe was used for high volume aspiration through the 6 F guiding catheter during withdrawal of the open Solitaire stent and the microcatheter into the guide catheter. Withdrawal was possible with minor effort and was observed under continuous fluoroscopy. As soon as the device became visible, the rotating hemostatic valve was quickly removed from the guiding catheter and another 50 ml of blood were aspirated. The Solitaire stent was loaded with a thrombus (figure 1C). Contrast injection of the right ICA after removal of the Solitaire confirmed total recanalization of the right MCA (figure 1D,E; TICI 3). Neither peripheral emboli nor vasospasm at the previously occluded vessel site was encountered.

The entire procedure (from the first to the final DSA run) lasted 59 min. The patient awoke from general anesthesia with only mild neurologic deficit (NIHSS 2). The patient was discharged to a rehabilitation center. At the 30 day follow-up, NIHSS was 0.

The patient was heparinized and received 100 mg of acetylsalicylic acid daily as secondary prophylaxis. ECG monitoring revealed atrial fibrillation as a potential source of cardiac embolism and hence the patient was anticoagulated with phenprocoumon. MRI examinations were refused by the severely claustrophobic patient. DSA 24 days after treatment showed a completely normal M1 segment and patent cortical branches of the entire right MCA. Follow-up CT 22 months later showed a small post-ischemic lesion of the right basal ganglia and normal cortex (figure 1F).

Discussion

The primary goal of the ‘ideal’ endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke is the fast and technically simple recanalization of the occluded vessel(s) with the least possible vessel wall injury, without displacement of thrombotic material either distally or proximally from the primary site of occlusion, and without any impact on the coagulation system. Because of the different pathophysiology, lessons learned from coronary interventions for myocardial ischemia can only partly be used for the treatment of cerebral ischemia. The different underlying causes of cerebral artery occlusion (eg, cardioembolic, arterio-arterial and veno-arterial emboli; cerebral artery stenosis, plaque or dissection) require different methods and tools for revascularization.

In the past, removal of a thrombus from an intracranial artery was a technical challenge. A variety of methods have been described during the past decade to overcome the limitations of LIF. The use of aspiration, snares,12 microforcepses,13 braided cages, stents,14 microbrushes, etc, has been described, but none gained general acceptance. The Penumbra aspiration system and the Merci retriever had at least a temporary market success.

Independent of thrombectomy purposes, we knew previously that misdeployed and detached Enterprise and Leo stents can be withdrawn from an artery with an Alligator device without visible injury to the vessel. While using Solitaire stents for aneurysm treatment, we observed that stents too far distally deployed could be pulled backwards in a more proximal position without closing them.

Thrombectomy with the Solitaire stent was an incidental success, neither planned nor anticipated during the development of the device. The essential constructive features of the device (eg, the eccentric fixation to the insertion wire, a longitudinal slit, the mesh size and the radial force)15 were found to be adequate for the retrieval of thrombus16 and coils.17

The Solitaire stent is now offered in two analogous versions (‘AB’ for aneurysm bridging; ‘FR’ for flow restoration) for aneurysm and stroke treatment. The ‘FR’ variant was CE marked for mechanical thrombectomy by a German notified body on 28 July 2009. Detachment of the device is mostly not within the primary scope for the treatment of ischemic stroke but is a viable option if thrombectomy fails and thrombus compression by the deployed stent restores flow in the target vessel.

The Solitaire FR is the first and certainly not the last successful device for mechanical thrombectomy. In September 2011, Pubmed revealed 18 publications with the combined keywords ‘Solitaire’ and ‘stroke’. Early followers are Trevo (Concentric Medical), IRIIS Plus and OptiCell (MindFrame, Irvine, USA), Aperio (Acandis, Pforzheim, Germany), Pulse (Penumbra, Alameda, USA), ReVive (Micrus, Codman and Shurtleff, Raynham, USA) and pREset (phenox). They differ in several features but their intended clinical use is essentially that described above. Many aspects of safety and efficacy of these Solitaire ‘derivates’ remain to be evaluated. After all, intracranial thrombectomy with the Solitaire stent was the unexpected ignition spark for these long awaited developments.

In the meantime, the safety and efficacy of the Solitaire FR and the Merci retrieval device were compared in a randomized trial which started in the USA in March 2010 (Solitaire FR With the Intention For Thrombectomy, SWIFT; http://clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01054560). In March 2011, enrollment for this trial was stopped as the sponsor (Covidien/ev3) expects 510(k) approval by the FDA based on the trial results.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The senior author is the co-inventor of the Solitaire stent but has no further interest in this product. ev3 has paid the open access charges for this article.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Contributors: MAP, EM and SF wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was revised by HB and HH. HH performed the endovascular treatment. HB reviewed the neurological aspects.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Rha JH, Saver JL. The impact of recanalization on ischemic stroke outcome: a meta-analysis. Stroke 2007;38:967–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zeumer H, Hacke W, Kolmann HL, et al. Local fibrinolysis in basilar artery thrombosis. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1982;107:728–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Furlan A, Higashida R, Wechsler L, et al. Intra-arterial pro-urokinase for acute ischemic stroke: the PROACT II study: a randomized controlled trial: Prolyse in Acute Cerebral Thromboembolism. JAMA 1999;282:2003–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1581–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute hemispheric stroke. The European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS). JAMA 1995;274:1017–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, et al. Randomised double-blind placebo controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Lancet 1998;352:1245–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clark WM, Wissman S, Albers GW, et al. Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (Alteplase) for ischemic stroke 3 to 5 hours after symptom onset. The ATLANTIS Study: a randomized controlled trial. Alteplase Thrombolysis for Acute Noninterventional Therapy in Ischemic Stroke. JAMA 1999;282:2019–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith WS, Sung G, Saver J, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: final results of the Multi MERCI trial. Stroke 2008;39:1205–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Henkes H, Reinartz J, Lowens S, et al. A device for fast mechanical clot retrieval from intracranial arteries (phenox clot retriever). Neurocrit Care 2006;5:134–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Penumbra Pivotal Stroke Trial Investigators The Penumbra Pivotal Stroke Trial Investigators. The Penumbra pivotal stroke trial. Safety and effectiveness of a new generation of mechanical devices for clot removal in intracranial large vessel occlusive disease. Stroke 2009;40:2761–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Henkes H, Flesser A, Brew S, et al. A novel microcatheter-delivered, highly-flexible and fully-retrievable stent, specifically designed for intracranial use. Technical note. Interv Neuroradiol 2003;9:391–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Imai K, Mori T, Izumoto H, et al. Succesful thrombectomy in acute terminal internal carotid occlusion using a basket type microsnare in conjunction with temporary proximal occlusion: a case report. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:1395–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hussain MS, Kelly ME, Moskowitz SI, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy for acute stroke with the Alligator Retrieval Device. Stroke 2009;40:3784–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kulcsár Z, Bonvin C, Lovblad KO, et al. Use of the Enterprise intracranial stent for revascularization of large vessel occlusions in acute stroke. Clin Neuroradiol. Published Online First: 28 February 2010. doi:10.1007/s00062-010-9024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krischek Ö, Miloslavski E, Fischer S, et al. A comparison of functional and physical properties of self-expanding intracranial stents (Neuroform, Wingspan, Solitaire, Leo(+), Enterprise). Minim Invasive Neurosurg 2011;54:21–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Castaño C, Dorado L, Guerrero C, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy with the Solitaire AB device in large artery occlusions of the anterior circulation: a pilot study. Stroke 2010;41:1836–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. O'Hare AM, Rogopoulos AM, Stracke PC, et al. Retrieval of displaced coil using a Solitaire stent. Clin Neuroradiol 2010;20:251–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]