Abstract

Airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) is one of the cardinal features of asthma. Contraction of airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells that line the airway wall is thought to influence aspects of AHR, resulting in excessive narrowing or occlusion of the airway. ASM contraction is primarily controlled by agonists that bind G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), which are expressed on ASM. Integrins also play a role in regulating ASM contraction signaling. As therapies for asthma are based on symptom relief, better understanding of the crosstalk between GPCRs and integrins holds good promise for the design of more effective therapies that target the underlying cellular and molecular mechanism that governs AHR. In this paper, we will review current knowledge about integrins and GPCRs in their regulation of ASM contraction signaling and discuss the emerging concept of crosstalk between the two and the implication of this crosstalk on the development of agents that target AHR.

1. Introduction

Airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) is the exaggerated response to relatively low concentrations of constricting agents (such as methacholine or histamine) or indirectly acting stimuli (such as cold air, respiratory infections or allergens, exercise, or cigarette smoke) that is observed in asthmatic subjects [1]. Contraction of airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells that line the airway wall is thought to influence aspects of AHR, culminating in the generation of force and excessive narrowing or occlusion of the airway [2]. ASM contraction is primarily controlled by agonists that bind G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR), which are expressed on ASM. Studies have shown that the asthmatic airways can be completely occluded even with only 40% contraction of ASM cells following an asthma exacerbation to GPCR agonists, such as histamine, that induce muscle shortening [3, 4]. Therefore, ASM GPCRs are important targets for therapeutic agents in asthma treatment. However, there is increasing evidence to suggest that chronic use of β 2-adrenergic receptor agonists, which act on GPCRs, is associated with worsening of bronchoconstrictor response to airway spasmogen [5], loss of asthma control, and exacerbation of asthma symptoms [6, 7], as well as an increased incidence of asthma-related morbidity and mortality [8]. Moreover, glucocorticoids, which are used as first line therapy for the treatment of inflammation associated with asthma, decrease AHR only if introduced early in disease diagnosis [9, 10]. Even then, there are side effects associated with the use of glucocorticoid when used at high dose and over long periods [10, 11]. Thus, the current treatment for asthma is based on symptom relief only and the ultimate goal of treating asthma is to target the underlying mechanisms, which include AHR.

We and others have shown that integrins may influence signaling events that contribute to AHR [12–14]. However, the mechanism behind this regulation remains to be fully elucidated. Moreover, there is increasing evidence to show that GPCRs interact with integrins to regulate ASM signaling pathways that are important in asthma. The cellular signaling processes include the regulation of cell adhesion, calcium signaling, injury and remodeling, mechanotransduction signaling and synaptic plasticity [15–18]. In this paper, we will review current knowledge about integrins and GPCRs in their regulation of ASM contraction signaling and discuss the emerging concept of crosstalk between the two and the implication of this crosstalk on the development of agents that target AHR.

2. Integrins and ASM Contraction Signaling

Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane proteins comprising one α and β chain. The expression of different integrins in ASM, their potential ligands and change in expression in asthma are detailed in Table 1. Integrin activation via ECM protein binding leads to the formation of a complex called focal adhesion, which consists of many structural proteins such as vinculin, talin, α-actinin, and paxillin [19–21]. Integrins can signal through the cell membrane in both directions: inside-out signaling and outside-in signaling. The extracellular binding activity of integrins is regulated from the inside of the cell (inside-out signaling), while the binding of ECM proteins such as laminin elicit signals that are transmitted into the cell (outside-in signaling) [22]. It is through these signaling activation events that integrins regulate cell attachment, survival, proliferation, cell spreading, differentiation, cytoskeleton reorganization, cell shape, cell migration, gene expression, tumorigenicity, intracellular pH, and increase in concentration of cytosolic Ca2+ [23].

Table 1.

Expression of different integrins in ASM, their potential ligands and change in expression in asthma.

| Integrin | Expression in ASM | Potential ligands | Change in expression in asthma (human) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1β1 | Human, sheep, guinea pig | Collagen I, II, III, IV, laminin-111, fibronectin. | n.d. | [27–30] |

| α2β1 | Human, guinea pig | Collagen I, IV, laminin-111, tenascin. | n.d. | [27–29, 31, 32] |

| α3β1 | Human | Collagen I, fibronectin, laminin-211, laminin-221, laminin-322, laminin-511, laminin-521. | n.d. | [14, 27, 28] |

| α4β1 | Human, sheep | Fibronectin, osteopontin, VCAM-1. | ↑ | [27, 28, 30, 33] |

| α5β1 | Human, guinea pig | Fibronectin, osteopontin. | ↑ | [12, 27, 28, 32, 34, 35] |

| α6β1 | Human | Laminin-111, laminin-411, laminin-511, laminin-521. | n.d. | [14, 28] |

| α6β4 | Human | Laminin-322, laminin-511, laminin-521. | n.d. | [28] |

| α7β1 | Human | Laminin-111, laminin-211, laminin-221. | n.d. | [14] |

| α8β1 | Mouse | Fibronectin, tenascin, vitronectin | n.d. | [28] |

| α9β1 | Human, guinea pig, mouse | ADAMs 1, 2, 3, 9, 15, factor XIII, L1-Cell adhesion molecule, osteopontin, tenascin, VCAM-1, von Willebrands factor. | ↓ | [28, 36, 37] |

| αvβ1 | Human | Fibronectin. | ↑ | [28, 32] |

| αvβ3 | Human | Fibrinogen, fibronectin, GSP, laminin, osteopontin, thrombospondin, vitronectin, von Willebrands factor. | n.d. | [27, 28, 32] |

| αvβ5 | Human, mouse | Osteopontin, vitronectin | ↑ | [38] |

n.d.: not determined.

Activation of integrins by either contractile or mechanical stimuli can result in two signaling events to cause ASM cell contraction. Firstly, integrin activation causes the phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and association with paxillin, leading to reorganization of the cytoskeleton [24–26]. Secondly, integrin activation will also increase intracellular Ca2+ concentration causing the phosphorylation of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) and activation of myosin ATPase activity, and crossbridge cycling [24–26].

3. GPCR and ASM Contraction Signaling

GPCR spans the cell membrane seven times and transduces extracellular stimuli from the binding of cell surface ligands into intracellular second messengers. These second messengers are known as the heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G proteins), which consists of Gα, Gβ, and Gγ subunits [39]. G proteins bind to the intracellular domain of GPCR and transmit signals that are important in ASM cellular functions. These functions include regulation of ASM proliferation and secretion of cytokines, chemokines, eicosanoids, or growth factors that orchestrate airway inflammation and remodeling [40]. GPCRs are also implicated to play important role in ASM cell contraction. The regulation of ASM tone is mediated by a balance between Gq- and Gs-coupled signaling, with Gq being linked to ASM contraction signaling and Gs being linked to relaxation signaling [40–43]. Agonist binding causes the activation and association of GPCRs with Gq, which promotes GTP binding and dissociation of Gα from Gβγ subunits. The dissociated Gq will then bind to effector phospholipase C, which then hydrolyses phosphoinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into 1,2-diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3). The net effect of these events is to increase the levels of intracellular Ca2+ as well as to activate cell contractile machinery through Ca2+ and protein kinase C-(PKC-) dependent mechanisms [40]. Activated PKC is able to phosphorylate a number of substrates which include calponin [41]. Phosphorylated calponin loses its ability to inhibit actomyosin ATPase, which is required for ASM cell contraction [41].

4. Evidence for Integrin and GPCR Crosstalk

There is emerging interest in crosstalk between integrins and GPCRs (Table 2). For example, muscarinic agonists that bind G12/13 protein can induce FAK activation and autophosphorylation in Swiss 3T3 cells, a fibroblast cell line, which is associated with integrin engagement signaling [52]. Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) is a consensus amino acid sequence found in ECM proteins that is recognized by integrins. It is found that muscarinic-induced FAK activation can be blocked by RGD peptide, suggesting crosstalk between GPCRs and integrins [52]. Similar observations have been observed for other GPCR agonists such as gastrin, endothelin, lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), angiotensin II, and bombesin [23, 53–56]. For example, stimulation of Swiss 3T3 cells with bombesin or endothelin results in FAK and paxillin phosphorylation and accompanied formation of focal adhesion plaques. This study suggests the formation of focal adhesion plaques as a common signal transduction pathway that mediates GPCR and integrin crosstalk. As for endothelial cells, angiotensin II is able to induce FAK and paxillin phosphorylation which results in augmented cell migration necessary for blood vessel repair and wound healing. This suggests a critical role for integrins in the angiogenic effect of angiotensin II via FAK activation. Taken together, the existence of distinct pathways leading to FAK activation suggests the possibility of synergistic interaction between GPCRs and integrin receptors. One of the key signaling events following integrin ligation is the activation of FAK. FAK activation recruits phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), leading to the activation of Akt that regulates cellular processes such as survival, proliferation, and contraction signaling [22]. Integrin-GPCR crosstalk is also linked with the activation of the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway [55]. Lysophosphatidic acid and thrombin receptors alone can activate MAPK in PC12 cells and this was blocked by RGD peptide and cytochalasin D, which is an actin depolymerising agent involved in the remodeling of the cytoskeleton [55]. This data suggests important crosstalk between integrins and GPCRs in regulating MAPK signaling. Amin and coworkers show that β1 integrin plays a crucial role in negating the apoptotic effects of β-adrenergic receptor stimulation in cardiac myocytes via the involvement of FAK and PI3K/Akt pathways [57]. Furthermore, a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase, PYK2, is able to link GPCRs to focal adhesion-dependent ERK activation to provide a point of convergence between signaling pathways triggered by integrins and certain GPCR agonists (histamine) in HEK 293 (human embryonic kidney cell line) and HeLa Cells [58]. In another study, Short and coworkers show that the regulation of MAPK activity by integrins and P2Y class of Gq/11-coupled receptors in human endothelial cells may involve activation of calcium and PKC [55]. Collectively, these studies support a role for integrin and GPCR crosstalk in physiological processes; however, integrin-GPCR interaction may be context-dependent given that different signaling mechanisms have been put forward.

Table 2.

Expression of ECM proteins/integrin ligands, their potential crosstalk with G proteins and change in expression in disease.

| ECM/integrin ligands | Potential crosstalk with G proteins | Disease | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyr61 | G12/13 |

↑ in breast and endometrial cancers |

[44] |

| RGD sequence in P2Y2 receptor |

G0 | n.d. | [45] |

| Laminin-111 | Gi, and Gs |

↑ in asthma |

[46–48] |

| Fibronectin | Gq and G12/13 | ↑ in asthma | [47–50] |

| Collagen I | Gq | ↑ in asthma | [47, 48, 51] |

| Collagen V | Gi and Gs |

↑ in asthma |

[46–48] |

n.d.: not determined.

The expression of ECM proteins can be regulated by GPCR ligands. For example, thrombin, sphingosine-1-phosphate, and LPA that signal through G12/13 and Rho A activation can increase the expression of the ECM protein Cyr61 (CCN1) in fibroblast, smooth muscle cells, and prostatic epithelial cells, respectively [44]. Cyr61 subsequently binds to integrin and activates downstream signaling pathways that regulate cell migration, survival, and proliferation. The engagement of integrin signaling pathway via GPCR ligands provide a means to amplify and sustain GPCR signaling in normal and pathophysiological cellular functions. In the asthma context, exaggerated GPCR signaling in AHR may contribute to increased expression of ECM proteins in the airway. The activation of integrins by these ECM proteins may thus amplify and sustain GPCR signaling to contribute to excessive bronchoconstriction that is observed in asthma exacerbations.

Activated integrins organize supramolecular complexes consisting of cytoskeletal domains and associated receptors and signaling molecules that may contribute to the formation of specialized lipid microdomains, which are referred to as “lipid rafts” [59]. Until now, there is no evidence for integrin-mediated activation of heterotrimeric G protein signaling cascade outside lipid rafts. However, there is some evidence to show that ligation of integrins within supramolecular complexes can lead to activation of GPCRs. CD47, an integrin associated protein, forms complexes with α V β 3 integrin and activates Gi signaling [60]. Integrin association is also required for activation of Go signaling by the P2Y2 receptor [45]. Recently, Berg and colleagues show that the relative amount of activated integrins at focal adhesion sites may govern signaling by μ opioid receptor, perhaps by altering interactions with G proteins [17]. Moreover, Lin and coworkers show that integrin ligation can trigger AMPA receptor-dependent Ca2+ influx and intracellular Ca2+ store release [61]. Taken together, crosstalk between integrins and GPCRs is relevant to ASM cells and possible in the asthma pathophysiological processes.

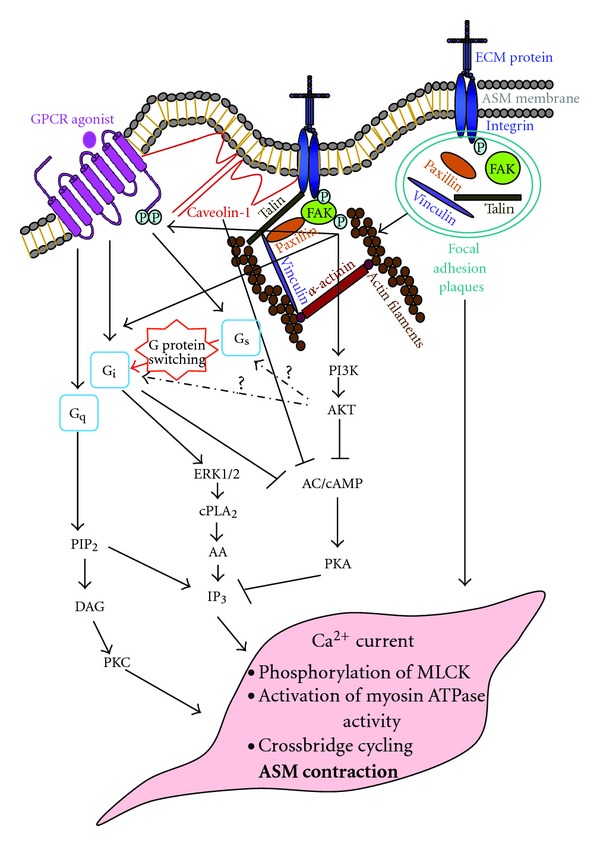

There are currently limited studies regarding the involvement of both integrins and GPCRs in the regulation of ASM cell contraction in healthy and asthmatic condition (Figure 1). However, crosstalk between integrins and GPCRs in contraction signaling is evident in other cell types. In the context of cardiac muscle contraction signaling, Wang and colleagues show that laminin binding-β 1 integrins in association with the actin cytoskeleton are able to attenuate adenylate cyclase (AC) activity. This in turn inhibits cholinergic regulation of L-type Ca2+ current in cardiac muscle contraction [62]. Subsequently, they also show that laminin binding-β1 integrins in conjunction with the actin cytoskeleton have the ability to reduce β1-adrenergic receptor-induced L-type Ca2+ and enhance β 2-adrenergic receptor-induced L-type Ca2+ current in the same cell [63]. Recently, the same group shows that β 1-integrin-induced activation of the FAK/PI3K/Akt pathway can inhibit β 1-adrenergic receptor-mediated stimulation of L-type Ca2+ current in cardiac muscle contraction [64]. This study suggests that increased deposition of ECM proteins such as laminin in a failing heart may favor β 2-adrenergic receptor signaling to β 1-adrenergic receptor signaling, and this may be mediated in part via β1 integrin-induced FAK/PI3K/Akt pathway.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram showing the proposed crosstalk between integrins and GPCRs in ASM cell contraction signaling. Integrin activation is achieved via the formation of focal adhesion plaques leading to cytoskeleton reorganization, which is essential for actin polymerisation and recruitment of linker proteins for tension development. Integrin activation causes the phosphorylation of FAK and activation of downstream signaling events leading to ASM contraction. Integrin activation will also increase intracellular Ca2+ concentration to cause phosphorylation of MLCK and activation of myosin ATPase activity and crossbridge cycling. GPCR-induced ASM contraction signaling can be enhanced either by inhibition of cAMP/AC activity that regulates ASM relaxation signaling, or by activation of Ca2+ current that is necessary for ASM contraction signaling. Activation of integrins can attenuate GPCR-induced AC activity via the FAK/PI3K/Akt pathway. cAMP accumulation and AC activity can be decreased by integrin activation via G protein switching, in which Gi is activated instead of Gs. Altered phosphorylation of GPCR by integrins is thought to underlie G protein switching in ASM cell. Caveolin-1 that binds integrin has been shown to regulate GPCR signaling. Caveolae which are rich in caveolin-1 function as negative regulators of cAMP accumulation in ASM cell. GPCR stimulation of Ca2+ can be enhanced by integrin via inhibition of cAMP/PKA and activation of the Gi/ERK1/2/cPLA2/AA signaling. AA: arachidonic acid; AC: adenyl cyclase; AKT: protein kinase B; ASM: airway smooth muscle; cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate; cPLA2: cytosolic phospholipase A2; DAG: diacylglycerol; ECM: extracellular matrix; ERK1/2: extracellular signal regulated kinase1/2; FAK: focal adhesion kinase; GPCR: G protein-coupled receptor; IP3: inositol 3,4,5-triphosphate; PIP2: phosphoinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PI3K: phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase; PKA: protein kinase A; PKC: protein kinas C.

As for atrial myocytes, β 2-adrenergic receptor stimulation of Ca2+ current is shown to be enhanced by β 1 integrin via inhibition of cAMP/PKA and activation of Gi/ERK/cPLA2/AA signaling [65]. This study suggests that increased ECM protein deposition in atrial diseases such as atrial fibrosis and/or hypertrophy may enhance β 2-adrenergic signaling, which depends more on Gi/ERK/cPLA2/AA signaling (contraction) instead of Gs/AC/cAMP/PKA signaling (relaxation). Cheng and coworkers also elegantly show the relationship between β 1 integrin and β-adrenergic receptor regulation of L-type Ca2+ current in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes [66]. Overexpression of β 1 integrin impedes β-adrenergic receptor-induced Ca2+ current via inhibition of AC/cAMP activity [66]. Similar observation is also obtained in adult cat atrial myocytes [62]. These findings suggest an important role for integrin and β-adrenergic receptor crosstalk in a diseased heart in which it is associated with chronic overload of pressure, increased ECM proteins and integrin receptors. Remodeling of GPCR receptor functions in asthma may occur too as there is increased deposition of ECM proteins and altered expression of integrins in the asthmatic airways. Collectively, these studies suggest that integrin activation might play a role in GPCR-induced muscle contraction of the airways.

In the context of ASM cell physiology there is only one study that links ECM proteins to GPCR-induced relaxation signaling [46]. Exposure of ASM cells to laminin decreases cAMP accumulation and AC activity [46]. The decrease in cAMP accumulation and AC activity could be due to a phenomenon known as “G protein switching” [46]. “G protein switching” occurs when agonists binding to the β 2-adrenergic receptor leads to the activation of Gi rather than Gs. The activation of Gi and decreased Gs signaling translate into low AC activity and thus decreased cAMP accumulation [46]. Altered phosphorylation states of the β 2-adrenergic receptor may be the underlying cause of G protein switching [67]. Since integrins are able to phosphorylate cell surface receptors, it is thought to play a role in G protein switching [68]. Human ASM cells predominantly express AC isoforms V and VI. These isoforms can be inhibited by Ca2+ and Gi signaling but stimulated by PKC [69, 70]. As integrin activation leads to PKC activation and Ca2+ release and influx, it suggests that integrins may modulate AC activity. This would explain the decrease in AC activity of human ASM cells cultured on laminin [71, 72]. This finding is important given that cAMP and AC are regulators of ASM relaxation signaling and this is the first study to implicate that integrins may regulate ASM tone. However, the involvement of GPCR crosstalk with integrins in healthy and asthmatic ASM was not directly investigated in this study and future studies in this area are warranted.

GPCR signaling has been shown to be highly compartmentalized and disruption of this subcellular organization may affect GPCR function [73]. Integrin clustering is a crucial step towards the formation of focal adhesion. Focal adhesion is able to recruit various proteins that are involved in cell signaling cascades which include G proteins in GPCR signaling [74]. Contractile human ASM cells exhibit omega-shaped plasma invaginations known as caveolae (developed from lipid rafts that bind caveolin-1 protein) [75]. Caveolae associate preferentially with signaling proteins that have roles in controlling smooth muscle contraction signaling, for example, Gα protein, members of the Rho small GTPase family, and PKC [75]. Depending on the type of GPCR, upon ligand binding, receptors may remain, exit or translocate into caveolae [76–78]. Muscarinic M3 and histamine H1 receptors have been found within the caveolae enriched membrane fraction of human ASM [75]. Moreover, muscarinic M3 receptors and Gq protein cofractionate in caveolin-1 enriched ASM cell membranes [79]. Caveolin-1 is able to bind to integrin α-subunits and has been shown to regulate GPCR-mediated signaling [80, 81]. Caveolin-1 links integrin α-subunit to tyrosine kinase Fyn which then recruits Shc and Grb2. This sequence of events couples integrins to downstream signaling pathways such as Ras-ERK pathway. Caveolae function as negative regulators of cAMP accumulation. This suggests that integrin signaling regulated by caveolin-1 may serve as important modifier of GPCR signaling such as cAMP signaling in asthma. Caveolae are found in close proximity to peripheral sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria, suggesting that caveolae may play a role in the spacial coordination of Ca2+-handling channels and organelles, which are implicated in ASM contraction signaling [82]. In addition, caveolae are anchored to the dystrophin glycoprotein complex (DGC). The DGC in turn links to ECM protein, laminin. This linkage is thought to help maintain membrane integrity [75, 83]. Collectively, these studies support the notion that caveolae may mediate ASM contractile response by aiding integrin and GPCR crosstalk signaling in asthma.

Integrins have also been implicated to regulate vascular smooth muscle cell contraction by mobilizing intracellular Ca2+. The addition of RGD peptide at millimolar range elicited increased levels of intracellular Ca2+ concentration [18]. This activation of ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ store and lysosome-like organelles by RGD peptide [18, 84] suggests important role of integrin-dependent Ca2+ signaling in regulating smooth muscle contraction. In support, α 7 β 1 integrin has been implicated to regulate transient elevation of intracellular-free Ca2+ concentration from both IP3 evoked Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and extracellular Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels in skeletal muscle cell [85].

Lastly, it is worth noting that GPCR agonists may promote ECM protein production, either directly, or indirectly by promoting autocrine TGFβ release. TGFβ is linked to thickening of ASM layer and deposition of collagen. Tatler and colleagues show that GPCR agonists, LPA and methacholine, induced TGFβ activation via integrin αvβ5 by ASM cells [38]. In support, Grainge and colleagues provide evidence that repeated bronchoconstriction with methacholine increases TGFβ immunoreactivity within the airway epithelium and increases the thickness of the subepithelial collagen layer, which is indicative of an acute alteration in airway collagen dynamics [86]. These studies provide alternative means of crosstalk between GPCRs and integrins, and one that could amplify direct GPCR/integrin interactions.

5. Concluding Remarks

In summary, integrins may play a role in regulating GPCR-induced ASM cell contraction signaling in asthma. This finding may offer explanations for increased contractility of ASM cells in asthma in which ECM proteins and their binding receptor integrins are highly expressed. Thus, integrins may be an interesting therapeutic target to inhibit ASM contraction signaling in asthma. However, the development of integrin antagonists has proven to be challenging. The role of integrins in asthma is complex as multiple integrins may participate to exert asthma symptoms, making it difficult to specifically target integrins that are involved in ASM contraction signaling. Perhaps targeting “linker proteins” that link the crosstalk between integrins and GPCRs in ASM contraction signaling is a possible therapeutic strategy for the treatment of AHR in asthma. One such possible target is caveolin-1 that may regulate integrins and GPCRs crosstalk. Other possible targets may be those which participate in G protein switching that are induced by integrin activation. Nonetheless, further understanding of the mechanisms behind integrin and GPCR crosstalk in ASM cell contraction signaling will enhance the development of more tailored therapy in the future for asthma treatment where AHR is a feature.

Acknowledgments

T. Tran is supported by the Singapore Ministry of Health's National Medical Research Council (NMRC) under its Individual Research Grant scheme, NMRC block vote, and Deputy President (Research and Technology) scheme. J. K. C. Tam is supported by the Singapore Ministry of Health's NMRC under its NMRC block vote and Deputy President (Research and Technology) scheme.

References

- 1.Thomson NC. Neurogenic and myogenic mechanisms of nonspecific bronchial hyperresponsiveness. European Journal of Respiratory Diseases. Supplement. 1983;128(1):206–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An S, Bai TR, Bates JHT, et al. Airway smooth muscle dynamics: a common pathway of airway obstruction in asthma. European Respiratory Journal. 2007;29(5):834–860. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00112606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolcock AJ, Salome CM, Yan K. The shape of the dose-response curve to histamine in asthmatic and normal subjects. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1984;130(1):71–75. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.James AL, Pare PD, Hogg JC. The mechanics of airway narrowing in asthma. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1989;139(1):242–246. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.1.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spitzer WO, Suissa S, Ernst P, et al. The use of beta-agonists and the risk of death and near death from asthma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326(8):501–506. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202203260801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drazen JM, Israel E, Boushey HA, et al. Comparison of regularly scheduled with as-needed use of albuterol in mild asthma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335(12):841–847. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609193351202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor DR, Town G, Herbison G. Asthma control during long term treatment with regular inhaled salbutamol and salmeterol. Thorax. 1998;53(9):744–752. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.9.744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suissa S, Ernst P, Boivin JF, et al. A cohort analysis of excess mortality in asthma and the use of inhaled beta-agonists. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1994;149(3, article 1):604–610. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.8118625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haahtela T, Järvinen M, Kava T, et al. Effects of reducing or discontinuing inhaled budesonide in patients with mild asthma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331(11):700–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409153311103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sher ER, Leung DYM, Surs W, et al. Steroid-resistant asthma. Cellular mechanisms contributing to inadequate response to glucocorticoid therapy. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1994;93(1):33–39. doi: 10.1172/JCI116963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schäcke H, Döcke WD, Asadullah K. Mechanisms involved in the side effects of glucocorticoids. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2002;96(1):23–43. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dekkers BGJ, Bos IST, Gosens R, Halayko AJ, Zaagsma J, Meurs H. The integrin-blocking peptide RGDS inhibits airway smooth muscle remodeling in a guinea pig model of allergic asthma. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2010;181(6):556–565. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200907-1065OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tran T, McNeill KD, Gerthoffer WT, Unruh H, Halayko AJ. Endogenous laminin is required for human airway smooth muscle cell maturation. Respiratory Research. 2006;7, article 117 doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tran T, Ens-Blackie K, Rector ES, et al. Laminin-binding integrin α7 is required for contractile phenotype expression by human airway myocytes. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2007;37(6):668–680. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0165OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slack BE, Siniaia MS. Adhesion-dependent redistribution of MAP kinase and MEK promotes muscarinic receptor-mediated signaling to the nucleus. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2005;95(2):366–378. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alenghat FJ, Tytell JD, Thodeti CK, Derrien A, Ingber DE. Mechanical control of cAMP signaling through integrins is mediated by the heterotrimeric Gαs protein. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2009;106(4):529–538. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berg KA, Zardeneta G, Hargreaves KM, Clarke WP, Milam SB. Integrins regulate opioid receptor signaling in trigeminal ganglion neurons. Neuroscience. 2007;144(3):889–897. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan WL, Holstein-Rathlou NH, Yip KP. Integrin mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ in renal vascular smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Physiology—Cell Physiology. 2001;280(3):C593–C603. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.3.C593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burridge K, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M. Focal adhesions, contractility, and signaling. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 1996;12:463–519. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brakebusch C, Fässler R. The integrin-actin connection, an eternal love affair. The EMBO Journal. 2003;22(10):2324–2333. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Critchley DR. Focal adhesions—the cytoskeletal connection. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2000;12(1):133–139. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Integrin signaling. Science. 1999;285(5430):1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross RS. Molecular and mechanical synergy: cross-talk between integrins and growth factor receptors. Cardiovascular Research. 2004;63(3):381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunst SJ, Tang DD, Opazo Saez A. Cytoskeletal remodeling of the airway smooth muscle cell: a mechanism for adaptation to mechanical forces in the lung. Respiratory Physiology and Neurobiology. 2003;137(2-3):151–168. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gunst SJ, Tang DD. The contractile apparatus and mechanical properties of airway smooth muscle. European Respiratory Journal. 2000;15(3):600–616. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15.29.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W, Gunst SJ. Interactions of airway smooth muscle cells with their tissue matrix implications for contraction. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2008;5(1):32–39. doi: 10.1513/pats.200704-048VS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen TTB, Ward JPT, Hirst SJ. β1-integrins mediate enhancement of airway smooth muscle proliferation by collagen and fibronectin. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2005;171(3):217–223. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200408-1046OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernandes DJ, Bonnacci JV, Stewart AG. Extracellular matrix, integrins, and masenchymal cell function in the airways. Current Drug Targets. 2006;7(5):567–577. doi: 10.2174/138945006776818700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bazán-Perkins B, Sánchez-Guerrero E, Vargas MH, et al. β1-integrins shedding in a guinea-pig model of chronic asthma with remodelled airways. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 2009;39(5):740–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abraham WM, Ahmed A, Serebriakov I, et al. A monoclonal antibody to alpha1beta1 blocks antigen-induced airway responses in sheep. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2004;169(1):97–104. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-543OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonacci JV, Schuliga M, Harris T, Stewart AG. Collagen impairs glucocorticoid actions in airway smooth muscle through integrin signalling. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2006;149(4):365–373. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng Q, Lai D, Nguyen TTB, Chan V, Matsuda T, Hirst SJ. Multiple β1 integrins mediate enhancement of human airway smooth muscle cytokine secretion by fibronectin and type I collagen. The Journal of Immunology. 2005;174(4):2258–2264. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abonia JP, Hallgren J, Jones T, et al. Alpha-4 integrins and VCAM-1, but not MAdCAM-1, are essential for recruitment of mast cell progenitors to the inflamed lung. Blood. 2006;108(5):1588–1594. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-012781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moir LM, Burgess JK, Black JL. Transforming growth factor β1 increases fibronectin deposition through integrin receptor α5β1 on human airway smooth muscle. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2008;121(4):1034–1039.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freyer AM, Johnson SR, Hall IP. Effects of growth factors and extracellular matrix on survival of human airway smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2001;25(5):569–576. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.5.4605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmer EL, Ruegg C, Ferrando R, Pytela R, Sheppard D. Sequence and tissue distribution of the integrin α9 subunit, a novel partner of β1 that is widely distributed in epithelia and muscle. Journal of Cell Biology. 1993;123(5):1289–1297. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.5.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen C, Kudo M, Rutaganira F, et al. Integrin α9β1 in airway smooth muscle suppresses exaggerated airway narrowing. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012;122(8):2916–2927. doi: 10.1172/JCI60387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tatler AL, John AE, Jolly L, et al. Integrin αvβ5-mediated TGF-β activation by airway smooth muscle cells in asthma. The Journal of Immunology. 2011;187(11):6094–6107. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong H, Shen B, Flevaris P, et al. G protein subunit Gα13 binds to integrin αIIbβ3 and mediates integrin “outside-in” signaling. Science. 2010;327(5963):340–343. doi: 10.1126/science.1174779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Billington CK, Penn RB. Signaling and regulation of G protein-coupled receptors in airway smooth muscle. Respiratory Research. 2003;4(1, article 2) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pohl J, Winder SJ, Allen BG, Walsh MP, Sellers JR, Gerthoffer WT. Phosphorylation of calponin in airway smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology—Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 1997;272(1, part 1):L115–L123. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.1.L115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hakonarson H, Grunstein MM. Regulation of second messengers associated with airway smooth muscle contraction and relaxation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1998;158(5, part 3):S115–S122. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.supplement_2.13tac700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giembycz MA, Raeburn D. Current concepts on mechanisms of force generation and maintenance in airways smooth muscle. Pulmonary Pharmacology. 1992;5(4):279–297. doi: 10.1016/0952-0600(92)90071-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walsh CT, Stupack D, Brown JH. G protien-coupled receptors go extracellular: RhoA integrates the integrins. Molecular Interventions. 2008;8(4):165–173. doi: 10.1124/mi.8.4.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erb L, Liu J, Ockerhausen J, et al. An RGD sequence in the P2Y2 receptor interacts with αvβ3 integrins and is required for Go-mediated signal transduction. Journal of Cell Biology. 2001;152(3):491–501. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Freyer AM, Billington CK, Penn RB, Hall IP. Extracellular matrix modulates β2-adrenergic receptor signaling in human airway smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2004;31(4):440–445. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0241OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parameswaran K, Willems-Widyastuti A, Alagappan VKT, Radford K, Kranenburg AR, Sharma HS. Role of extracellular matrix and its regulators in human airway smooth muscle biology. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2006;44(1):139–146. doi: 10.1385/CBB:44:1:139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roche WR, Williams JH, Beasley R, Holgate ST. Subepithelial fibrosis in the bronchi of asthmatics. The Lancet. 1989;1(8637):520–524. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Toews ML, Ustinova EE, Schultz HD. Lysophosphatidic acid enhances contractility of isolated airway smooth muscle. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1997;83(4):1216–1222. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.4.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hartney JM, Gustafson CE, Bowler RP, Pelanda R, Torres RM. Thromboxane receptor signaling is required for fibronectin-induced matrix metalloproteinase 9 production by human and murine macrophages and is attenuated by the Arhgef1 molecule. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(52):44521–44531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.282772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haag S, Matthiesen S, Juergens UR, Racké K. Muscarinic receptors mediate stimulation of collagen synthesis in human lung fibroblasts. European Respiratory Journal. 2008;32(3):555–562. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00129307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rozengurt E. Signal transduction pathways in the mitogenic response to G protein-coupled neuropeptide receptor agonists. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1998;177(4):507–517. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199812)177:4<507::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Montiel M, Pérez de la Blanca E, Jiménez E. Angiotensin II induces focal adhesion kinase/paxillin phosphorylation and cell migration in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;327(4):971–978. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Slack BE. Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin and focal adhesion kinase by activation of muscarinic m3 receptors is dependent on integrin engagement by the extracellular matrix. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(13):7281–7286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Short SM, Boyer JL, Juliano RL. Integrins regulate the linkage between upstream and downstream events in G protein-coupled receptor signaling to mitogen-activated protein kinase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(17):12970–12977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sinnett-Smith J, Zachary I, Valverde AM, Rozengurt E. Bombesin stimulation of p125 focal adhesion kinase tyrosine phosphorylation. Role of protein kinase C, Ca2+ mobilization, and the actin cytoskeleton. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(19):14261–14268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Amin P, Singh M, Singh K. β-Adrenergic receptor-stimulated cardiac myocyte apoptosis: role of β1 integrins. Journal of Signal Transduction. 2011;2011:9 pages. doi: 10.1155/2011/179057.179057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Litvak V, Tian D, Shaul YD, Lev S. Targeting of PYK2 to focal adhesions as a cellular mechanism for convergence between integrins and G protein-coupled receptor signaling cascades. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(42):32736–32746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004200200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leitinger B, Hogg N. The involvement of lipid rafts in the regulation of integrin function. Journal of Cell Science. 2002;115(5):963–972. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.5.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brittain JE, Mlinar KJ, Anderson CS, Orringer EP, Parise LV. Activation of sickle red blood cell adhesion via integrin-associated protein/CD47-induced signal transduction. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001;107(12):1555–1562. doi: 10.1172/JCI10817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin CY, Hilgenberg LGW, Smith MA, Lynch G, Gall CM. Integrin regulation of cytoplasmic calcium in excitatory neurons depends upon glutamate receptors and release from intracellular stores. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2008;37(4):770–780. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang YG, Samarel AM, Lipsius SL. Laminin acts via β1 integrin signalling to alter cholinergic regulation of L-type Ca2+ current in cat atrial myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 2000;526(1):57–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang YG, Samarel AM, Lipsius SL. Laminin binding to β1-integrins selectively alters β1- and β2-adrenoceptor signalling in cat atrial myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 2000;527(1):3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang YG, Ji X, Pabbidi M, Samarel AM, Lipsius SL. Laminin acts via focal adhesion kinase/phosphatidylinositol-3′ kinase/protein kinase B to down-regulate β1-adrenergic receptor signalling in cat atrial myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 2009;587(3):541–550. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.163824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pabbidi MR, Ji X, Samarel AM, Lipsius SL. Laminin enhances β2-adrenergic receptor stimulation of L-type Ca2+ current via cytosolic phospholipase A2 signalling in cat atrial myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 2009;587(20):4785–4797. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.179226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng Q, Ross RS, Walsh KB. Overexpression of the integrin β1A subunit and the β1A cytoplasmic domain modifies the β-adrenergic regulation of the cardiac L-type Ca2+current. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2004;36(6):809–819. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Daaka Y, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Switching of the coupling of the β2-adrenergic receptor to different g proteins by protein kinase A. Nature. 1997;390(6655):88–91. doi: 10.1038/36362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moro L, Venturino M, Bozzo C, et al. Integrins induce activation of EGF receptor: role in MAP kinase induction and adhesion-dependent cell survival. The EMBO Journal. 1998;17(22):6622–6632. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Billington CK, Hall IP, Mundell SJ, et al. Inflammatory and contractile agents sensitize specific adenylyl cyclase isoforms in human airway smooth muscle. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 1999;21(5):597–606. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.5.3759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu D, Isaacs C, Hall IP, Emala CW. Human airway smooth muscle expresses 7 isoforms of adenylyl cyclase: a dominant role for isoform V. American Journal of Physiology—Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2001;281(4):L832–L843. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.4.L832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sjaastad MD, Lewis RS, Nelson WJ. Mechanisms of integrin-mediated calcium signaling in MDCK cells: regulation of adhesion by IP3- and store-independent calcium influx. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1996;7(7):1025–1041. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.7.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chun JS, Ha MJ, Jacobson BS. Differential translocation of protein kinase C ε during HeLa cell adhesion to a gelatin substratum. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(22):13008–13012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.13008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Steinberg SF, Brunton LL. Compartmentation of G protein-coupled signaling pathways in cardiac myocytes. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2001;41:751–773. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lewis JM, Schwartz MA. Integrins regulate the association and phosphorylation of paxillin by c-Abl. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(23):14225–14230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Halayko AJ, Tran T, Gosens R. Phenotype and functional plasticity of airway smooth muscle: role of caveolae and caveolins. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2008;5(1):80–88. doi: 10.1513/pats.200705-057VS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ostrom RS, Gregorian C, Drenan RM, Xiang Y, Regan JW, Insel PA. Receptor number and caveolar co-localization determine receptor coupling efficiency to adenylyl cyclase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(45):42063–42069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chun M, Liyanage UK, Lisanti MP, Lodish HF. Signal transduction of a G protein-coupled receptor in caveolae: colocalization of endothelin and its receptor with caveolin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(24):11728–11732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sabourin T, Bastien L, Bachvarov DR, Marceau F. Agonist-induced translocation of the kinin B1 receptor to caveolae-related rafts. Molecular Pharmacology. 2002;61(3):546–553. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.3.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gosens R, Stelmack GL, Dueck G, et al. Caveolae facilitate muscarinic receptor-mediated intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and contraction in airway smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology—Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2007;293(6):L1406–L1418. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00312.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wary KK, Mariotti A, Zurzolo C, Giancotti FG. A requirement for caveolin-1 and associated kinase Fyn in integrin signaling and anchorage-dependent cell growth. Cell. 1998;94(5):625–634. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rybin VO, Xu X, Lisanti MP, Steinberg SF. Differential targeting of β-adrenergic receptor subtypes and adenylyl cyclase to cardiomyocyte caveolae: a mechanism to functionally regulate the cAMP signaling pathway. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(52):41447–41457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bergdahl A, Swärd K. Caveolae-associated signalling in smooth muscle. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2004;82(5):289–299. doi: 10.1139/y04-033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Halayko AJ, Stelmack GL. The association of caveolae, actin, and the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex: a role in smooth muscle phenotype and function? Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2005;83(10):877–891. doi: 10.1139/y05-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Umesh A, Thompson MA, Chini EN, Yip KP, Sham JSK. Integrin ligands mobilize Ca2+ from ryanodine receptor-gated stores and lysosome-related acidic organelles in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(45):34312–34323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606765200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kwon MS, Park CS, Choi KR, et al. Calreticulin couples calcium release and calcium influx in integrin-mediated calcium signaling. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2000;11(4):1433–1443. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.4.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Grainge CL, Lau LCK, Ward JA, et al. Effect of bronchoconstriction on airway remodeling in asthma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(21):2006–2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]