Abstract

We examined the effects of fenofibrate and atorvastatin on very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) apolipoprotein (apo)E metabolism in the metabolic syndrome (MetS). We studied 11 MetS men in a randomized, double-blind, crossover trial. VLDL-apoE kinetics were examined using stable isotope methods and compartmental modeling. Compared with placebo, fenofibrate (200 mg/day) and atorvastatin (40 mg/day) decreased plasma apoE concentrations (P < 0.05). Fenofibrate decreased VLDL-apoE concentration and production rate (PR) and increased VLDL-apoE fractional catabolic rate (FCR) compared with placebo (P < 0.05). Compared with placebo, atorvastatin decreased VLDL-apoE concentration and increased VLDL-apoE FCR (P < 0.05). Fenofibrate and atorvastatin had comparable effects on VLDL-apoE concentration. The increase in VLDL-apoE FCR with fenofibrate was 22% less than that with atorvastatin (P < 0.01). With fenofibrate, the change in VLDL-apoE concentration was positively correlated with change in VLDL-apoB concentration, and negatively correlated with change in VLDL-apoB FCR. In MetS, fenofibrate and atorvastatin decreased plasma apoE concentrations. Fenofibrate decreased VLDL-apoE concentration by lowering VLDL-apoE production and increasing VLDL-apoE catabolism. By contrast, atorvastatin decreased VLDL-apoE concentration chiefly by increasing VLDL-apoE catabolism. Our study provides new insights into the mechanisms of action of two different lipid-lowering therapies on VLDL-apoE metabolism in MetS.

Keywords: apolipoprotein E, lipoprotein metabolism, statin, very low density lipoprotein

Hypertriglyceridemia, a key feature of the metabolic syndrome (MetS), is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) (1). It is the most consistent lipid disorder in subjects with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Hypertriglyceridemia is primarily related to dysregulated triglyceride-rich lipoprotein (TRL) metabolism, including overproduction of very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles and delayed catabolism of TRL and their remnants (2). These abnormalities are a collective consequence of insulin resistance and increased lipid substrate availability in the liver, as well as depressed activities of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and hepatic receptors (3).

Apolipoprotein (apo)E is a 34.2 kDa glycoprotein synthesized by the liver and, to a lesser extent, by peripheral tissues (4). Clinical studies show that plasma apoE concentration explains 20–40% of the variation in plasma triglyceride concentrations. A key role of apoE is to act as a high-affinity ligand for members of the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor family, including the LDL receptor, LDL receptor-related protein (LRP), the VLDL receptor, GP330/Megalin, and ApoER-2. ApoE is also a ligand for heparin sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG). By binding to these hepatic and extrahepactic receptors, apoE mediates the clearance of TRL and their remnants from the circulation (5). The role of apoE is not confined only to the clearance of lipoprotein particles, however. ApoE inhibits LPL-mediated lipolysis of lipoproteins by displacing LPL cofactor apoC-II (6, 7). ApoE has also been shown to stimulate hepatic secretion VLDL particles; apoE-deficient mice showed a 50% reduction in VLDL secretion (8), and hepatic expression of human apoE2, apoE3, and apoE4 stimulated VLDL production in vivo (9–12). Therefore, apoE is an important determinant of in vivo TRL metabolism. Of interest, in vitro and animal studies suggest that apoE may be anti-atherogenic via its modulation of anti-oxidative, anti-coagulant, anti-proliferation, and anti-inflammatory pathways (13). The exact relationship between apoE and CVD risk, however, remains unclear, due in part to the polymorphic nature of the apoE gene (14). Nonetheless, recent studies suggested that high plasma apoE concentration is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in old age (15).

Clinical studies support the use of fibrates and statins to treat dyslipidemia in insulin-resistant and obese states (16, 17). Fibrates are ligands that bind to and activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-α in the liver. PPAR-α activation exerts beneficial effects on fatty acid and glucose metabolism (18). PPAR-α activation increases acyl-CoA synthase and fatty acid transporter protein; this facilitates intracellular transport, acylation, and β-oxidation of fatty acids, with the net effect of decreasing fatty acid availability for triglyceride synthesis and secretion (18). Whether fibrates lower plasma triglyceride concentrations by regulating VLDL apoE concentration and metabolism is, however, unknown. Statins inhibit de novo cholesterol synthesis, thereby upregulating LDL receptor activity. This enhances the uptake of both hepatic and intestinal-derived TRLs, and decreases their plasma concentrations (19). The triglyceride-lowering effect of statins may also be partly due to altered apoE concentration and metabolism. To date, two studies have examined the effect of statins on VLDL apoE kinetics (20, 21), but the findings were inconsistent.

We previously reported a randomized crossover study to examine the effect of fenofibrate and atorvastatin on TRL metabolism in the metabolic syndrome (22, 23). We extend this study by investigating the effect of these agents on VLDL apoE metabolism. Given the important role of apoE in hepatic receptor recognition and that we previously demonstrated the enhancing effects of fenofibrate and atorvastatin on TRL catabolism, we hypothesized that these treatments would also reduce plasma VLDL apoE concentration by increasing its fractional catabolic rate (FCR). We also explored associations between the kinetics of VLDL apoE and VLDL apoB and other regulators of TRL metabolism, including VLDL apoC-III.

METHODS

Subjects

Eleven Caucasian men with the metabolic syndrome by the NCEP ATP III definition (24) were recruited. Upper limits (HDL cholesterol ≤ 1.2mmol/l, LDL cholesterol ≤ 6mmol/l, and plasma triglycerides ≤ 4.5 mmol/l) were stipulated to exclude subjects with genetic hyperlipidemia, including familial hypercholesterolemia and familial hypertriglyceridemia, and other secondary causes of severe dyslipidemia. Subjects with diabetes mellitus (defined by oral glucose tolerance test), cardiovascular disease, renal dysfunction (macroproteinuria and/or serum creatinine >120 μmol/l), apoE2/E2 genotype, hypothyroidism, abnormal liver or muscle enzymes, alcohol consumption > 30 g alcohol/day, or use of lipid modifying agents were excluded. All were nonsmokers and were consuming ad libitum, weight maintenance diets. Subjects provided informed written consent, and the study was approved by the South Eastern Sydney Area Health Service.

Study design and clinical protocols

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, three-way crossover trial. Eligible subjects entered a four-week weight maintenance run-in period followed by randomization to a five-week treatment period of either micronized fenofibrate (200 mg/day), atorvastatin (40 mg/day), or placebo, with crossover to two further five-week treatment periods interspersed by two-week wash-outs. Advice was given to continue isocaloric diets and maintain physical activity. Compliance with study medication was assessed by tablet count.

All subjects were admitted to the metabolic ward in the morning after a minimum of 12 h fast. They were studied semirecumbent and allowed water only during the study. Venous blood was collected for biochemical measurements. Body weight and height were measured, and arterial blood pressure was recorded using a Dinamap1846 SX/P monitor (Critikon Inc.). Dietary intake was assessed using 24 h dietary diaries and DIET 4 Nutrient Calculation Software (Xyris Software).

A primed constant infusion of deuterated (D3)-leucine (1 mg/kg bolus and 1 mg/kg/h infusion) was administered intravenously into an antecubital vein via a Teflon cannula for 6 h. Blood samples were taken at baseline and at 15, 30, 45 min and at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 16 h after isotope injection. Additional blood samples were collected in the morning on the four following days (24, 48, 72, and 96 h) after a minimum 12 h fast. All the procedures were repeated at the end of each treatment period.

Biochemical analyses

Laboratory methods for measurements of lipids, lipoproteins, and other biochemical analytes have been detailed previously (22, 23). Insulin resistance was calculated using a homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) score. Total plasma and VLDL apoE and VLDL apoC-III concentrations were measured by electroimmunoassay (Sebia); interassay CVs were <5%. Plasma apoA-V concentration was determined using a dual-antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Linco Diagnostic Services).

Isolation and measurement of D3-leucine enrichment in VLDL apoE

Three milliliters of plasma was used for isolation of 1 ml VLDL (<1.006 kg/l) fraction by sequential ultracentrifugation at 40,000 rpm in a Ti 50.4 rotor (Optima LE-80K, Beckman Coulter). VLDL apoE was isolated using 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The apoE band was excised from the PVDF and hydrolyzed in 200 μl 6M HCl overnight at 110°C in pyrolysis-cleaned half-dram vials (21, 25, 26). Samples were dried at 110°C and derivatized using a modified oxazolinone method. The oxazolinone derivatives were analyzed by negative ion chemical ionization gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GCMS). The isotopic enrichment was determined as the tracer-to-tracee ratio (TTR) of monitored selected ions at mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio of 212/209. The average coefficient of variation of apoE tracer measurement, including processes associated with isolation of apoE from plasma through to the measurement of isotopic enrichment, was <10%.

Kinetic analyses

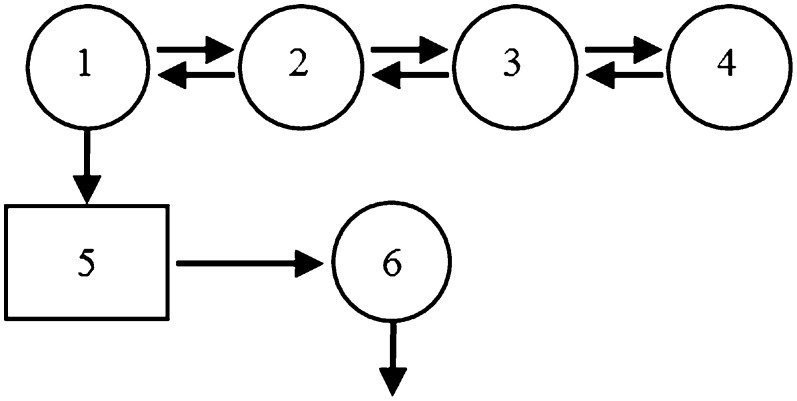

A model of VLDL apoE metabolism was developed using the SAAM II program (Epsilon Group, Charlottesville, VA) (Fig. 1). The model consists of a four-compartment subsystem (compartments 1–4) that describes plasma leucine kinetics. This subsystem is connected to an intrahepatic delay compartment (compartment 5) that accounts for the time required for tissue assembly, synthesis, and secretion of apoE into plasma and/or apoE that was transported into VLDL indirectly from other lipoprotein fractions due to lipoprotein conversions or apolipoprotein exchange. The kinetics of VLDL apoE is described by a plasma compartment (compartment 6). The FCR of VLDL apoE, equivalent to the irreversible loss from compartment 6, was estimated after fitting the model to the VLDL apoE tracer data. The production rate (PR) of apoE was calculated as the product of FCR and pool size, which equals the plasma VLDL concentration multiplied by plasma volume; plasma volume was estimated as 4.5% of body weight.

Fig. 1.

Compartment model describing apoE tracer kinetics. Leucine tracer is injected into plasma compartment 2 and distributes to extravascular compartments 1, 3, and 4. Compartments 1–4 are required to describe leucine tracer kinetics observed in plasma. Compartment 1 is connected to an intracellular delay compartment (compartment 5) that accounts for the time required for tissue assembly, synthesis, and secretion of apoE and/or apoE that was transported into VLDL indirectly from other lipoprotein fractions due to lipoprotein conversions or apolipoprotein exchange. Compartment 6 describes the kinetics of VLDL-apoE.

Statistical analyses

Skewed variables were logarithmically transformed where appropriate. Data at the end of the three treatment periods were compared using a mixed-effect model (SAS Proc Mixed, SAS Institute), which also tested for carry-over, treatment sequence, and time-dependent effects. There were no significant carry-over, treatment sequence, or time-dependent effects. Tukey-Kramer test was applied to account for multiple comparisons for a given variable across the three treatment periods. Statistical associations between changes in variables were examined using simple, stepwise, and multiple linear regression methods. The statistical significance was set at the 5% level.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the pretreatment clinical and biochemical characteristics of the subjects. On average, they were middle-aged, centrally obese, normotensive, and insulin resistant. There were no significant treatment effects on body weight, blood pressure, insulin, glucose, fatty acids, or HOMA score. Both fenofibrate and atorvastatin were well tolerated. There were no significant changes in liver and muscle enzymes or in serum creatinine, and no subjects developed dip-stick-positive proteinuria. Tablet and capsule counts confirmed that compliance with active treatments was 100%.

TABLE 1.

Clinical and biochemical characteristics of study subjects at baseline

| Characteristic | Baseline Value |

| Age (years) | 46.3 ± 6.9 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.5 ± 2.6 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 102.1 ± 1.8 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 128.5 ± 3.1 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 83.8 ± 2.3 |

| Non-esterified free fatty acid (mmol/l) | 0.54 ± 0.10 |

| Plasma glucose (mmol/l) | 5.68 ± 0.46 |

| Plasma insulin (mU/l) | 19.9 ± 6.74 |

| HOMA score | 5.10 ± 2.05 |

Data presented as mean ± SD.

Table 2 gives the plasma concentrations of lipids, lipoproteins, and apolipoproteins on placebo, fenofibrate, and atorvastatin. Compared with placebo, fenofibrate significantly decreased total cholesterol (−7%), non-HDL cholesterol (−10%), plasma and VLDL triglyceride (−32% and −42%, respectively), plasma and VLDL apoB (−13 and −26%, respectively), plasma and VLDL apoC-III (−23% and −39%, respectively), and plasma apoE (−12%) concentrations and the VLDL triglyceride:apoB (−26%) and lathosterol:cholesterol (−20%) ratios. Fenofibrate also significantly increased HDL cholesterol (+11%) and plasma apoA-I (+6%) concentrations. Compared with placebo, atorvastatin significantly decreased total cholesterol (−40%), LDL cholesterol (−53%), non-HDL cholesterol (−48%), plasma and VLDL triglyceride (−38% and −34%, respectively), plasma and VLDL apoB (−42 and −38%, respectively), plasma and VLDL apoC-III (−19% and −42%, respectively), plasma apoE (−23%) and plasma apoA-V (−30%) concentrations and the lathosterol:cholesterol ratio (−68%).

TABLE 2.

Lipid, lipoprotein and apolipoprotein concentrations on placebo (P), fenofibrate (F) and atorvastatin (A)

|

P |

||||||

| Parameter | Placebo | Fenofibrate | Atorvastatin | F versus P | A versus P | F versus A |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 5.88 ± 0.15 | 5.48 ± 0.17 | 3.50 ± 0.17 | 0.02 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 3.94 ± 0.22 | 3.70 ± 0.18 | 1.86 ± 0.15 | 0.08 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 1.04 ± 0.07 | 0.95 ± 0.05 | <0.01 | 0.838 | <0.01 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 4.95 ± 0.13 | 4.44 ± 0.19 | 2.55 ± 0.16 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/l) | 2.44 ± 0.31 | 1.66 ± 0.27 | 1.51 ± 0.20 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.5 |

| VLDL triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.73 ± 0.26 | 1.00 ± 0.23 | 1.14 ± 0.24 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.56 |

| Plasma apoB-100 (mg/l) | 1110 ± 30.0 | 970 ± 40.0 | 640 ± 40.0 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| VLDL-apoB-100 (mg/l) | 92.2 ± 10.0 | 67.8 ± 10.0 | 56.9 ± 7.0 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.53 |

| Plasma apoC-III (mg/l) | 155 ± 10.7 | 120 ± 14.0 | 125 ± 8.0 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.90 |

| VLDL apoC-III (mg/l) | 95.5 ± 13.5 | 58.3 ± 12.4 | 55.7 ± 8.6 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.98 |

| Plasma apoE (mg/l) | 47.3 ± 3.52 | 41.6 ± 2.74 | 36.5 ± 3.04 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.04 |

| Plasma apoA-V (mg/l) | 96.8 ± 26.1 | 90.0 ± 38.6 | 67.7 ± 21.5 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.28 |

| Plasma apoA-I (g/l) | 1.13 ± 0.05 | 1.20 ± 0.06 | 1.12 ± 0.04 | <0.01 | 0.74 | 0.16 |

| VLDL triglyceride:apoB ratio | 16.34 ± 1.29 | 12.12 ± 1.30 | 16.58 ± 1.62 | <0.01 | 0.99 | 0.01 |

| Lathosterol:cholesterol ratio | 1.33 ± 0.12 | 1.06 ± 0.10 | 0.42 ± 0.04 | 0.04 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

Data presented as mean ± SEM. Adjusted P values were reported to account for multiple comparisons using Tukey-Kramer test. A, atorvastatin; F, fenofibrate; P, placebo.

Table 3 gives the plasma concentrations and kinetics of VLDL apoE on placebo, fenofibrate, and atorvastatin. Compared with placebo, fenofibrate significantly decreased VLDL apoE concentration (−32%) and PR (−17%), and it increased VLDL apoE FCR (+24%). Compared with placebo, atorvastatin significantly decreased VLDL apoE concentration (−29%) and increased VLDL apoE FCR (+51%). The effect of fenofibrate and atorvastatin on VLDL apoE concentration was not significantly different. The increase in VLDL apoE FCR with fenofibrate was significantly less (−22%) than with atorvastatin.

TABLE 3.

Concentrations, fractional catabolic rates, and production rates for VLDL-apoE during placebo, fenofibrate, and atorvastatin

|

P |

||||||

| Placebo | Fenofibrate | Atorvastatin | F versus P | A versus P | F versus A | |

| Concentration (mg/l) | 22.97 ± 2.26 | 15.36 ± 1.71 | 15.37 ± 0.54 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.99 |

| Fractional catabolic rate (pools/day) | 4.86 ± 0.21 | 5.98 ± 0.35 | 7.30 ± 0.48 | 0.04 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Production rate (mg/kg/day) | 4.91 ± 0.41 | 3.90 ± 0.20 | 5.09 ± 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.99 | 0.05 |

Data presented as mean ± SEM. Adjusted P values are reported to account for multiple comparisons using Tukey-Kramer test. A, atorvastatin; F, fenofibrate; P, placebo.

Given the role of apoE in regulating TRL metabolism, associations between VLDL apoE and VLDL apoB kinetic parameters were explored. With fenofibrate, change in VLDL apoE concentration was associated with change in VLDL apoB concentration (r = 0.818, P < 0.01), FCR (r = −0.594, P = 0.05), and PR (r = 0.689, P = 0.02). Change in VLDL apoE FCR was associated with change in VLDL apoB concentration (r = −0.588, P = 0.05) and FCR (r = 0.69, P = 0.02). The above associations between VLDL apoE and VLDL apoB kinetic parameters were also observed with atorvastatin but did not reach statistical significance.

The association between VLDL apoE and VLDL apoC-III, an additional regulator of TRL metabolism, was also explored. Change in VLDL apoE concentration, FCR, and PR were associated with change in VLDL apoC-III concentration (r = 0.641, P = 0.03), FCR (r = 0.690, P = 0.02), and PR (r = 0.659, P = 0.03), respectively, with fenofibrate. The above associations between VLDL apoE and VLDL apoC-III kinetic parameters were also observed with atorvastatin but did not reach statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

We provide new information on the effect of fenofibrate and atorvastatin on VLDL apoE metabolism in subjects with the metabolic syndrome. We demonstrated, for the first time, that fenofibrate decreased VLDL apoE concentration by decreasing VLDL apoE PR and increasing its FCR. We also showed that atorvastatin decreased VLDL apoE concentration by increasing VLDL apoE FCR. These effects were achieved with no significant changes in body weight and insulin resistance.

Previous kinetic studies

Previous kinetic studies using stable isotope methods that examined the effects of statins on VLDL apoE metabolism have not shown consistent effects. Cohn et al. reported that atorvastatin 40 mg/day decreased VLDL apoE concentration by decreasing VLDL apoE PR in six subjects with combined hyperlipidemia (21). By contrast, Bach-Ngohou showed, in an uncontrolled study, that atorvastatin 40 mg/day increased VLDL apoE concentration and PR in seven dyslipidemic diabetic subjects (20). Discrepancies among these studies may relate to different clinical and biochemical characteristics of study subjects, as well as study design. No studies, to date, have examined the effect of fenofibrate on VLDL apoE metabolism or performed a direct comparison between fenofibrate and atorvastatin. We improve on previous reports by focusing on the metabolic syndrome using a larger sample size and by investigating the effect of fenofibrate and atorvastatin on VLDL apoE metabolism using a three-way randomized crossover study design.

Data interpretation

Hypertriglyceridemia in insulin-resistant states, including the metabolic syndrome, results from overproduction and reduced catabolism of TRL and their remnants (2). These kinetic aberrations may be related to altered VLDL apoE metabolism. Previous studies demonstrated that overproduction and slower catabolism of VLDL apoE explained the high concentration of VLDL apoE in hypertriglyceridemic subjects (25, 27). Higher VLDL apoE concentration and PR were associated with elevated plasma and VLDL triglycerides (25, 27). Our subjects exhibited overproduction of VLDL apoE, with concentrations of plasma and VLDL apoE within range of those previously reported in hypertriglyceridemic subjects (20, 21, 25, 27). It is, however, important to acknowledge that, in this study, VLDL apoE PR represents the transport of apoE through the VLDL pool. As such, VLDL apoE PR includes both the hepatic secretion of apoE and that transported into the VLDL pool from other lipoprotein fractions, particularly HDL. Similarly, the VLDL apoE FCR represents the irreversible loss of apoE from the VLDL pool, which includes clearance of VLDL apoE by the hepatic and peripheral receptors together with that fraction of the VLDL apoE pool that is transported to other lipoprotein fractions, primarily HDL, as a function of time.

Effect of fenofibrate on VLDL apoE metabolism

We showed that fenofibrate decreased VLDL apoE concentration by decreasing PR and increasing FCR. The decrease in VLDL apoE PR could be due to downregulation of apoE gene expression and/or inhibition of apoE secretion. Our data may be more consistent with the latter mechanism. Although hepatic apoE gene expression may be regulated via a liver X receptor (LXR)-mediated pathway (28), fenofibrate, in its carboxylic acid form, does not function as an LXR-antagonist (29). Therefore, we hypothesize that the decrease in VLDL apoE PR may be due to increased intracellular degradation of translated apoE prior to secretion (30). It is also plausible that decreased VLDL apoE PR is due to altered apoE distribution between VLDL and HDL particles rather than an effect on gene expression. Future studies examining the kinetics of apoE in other lipoprotein fractions, particularly HDL, are warranted.

The precise mechanism for the increase in VLDL apoE FCR with fenofibrate is unclear, but it may be due to increased direct removal of VLDL apoE from the circulation via hepatic and/or peripheral lipoprotein receptors (31). This may reflect, in part, the role of apoE as a ligand for receptor-mediated uptake of TRL and remnant particles. It is also consistent with the observed coupling of VLDL apoE and VLDL apoB FCR and the similar magnitude of change in VLDL apoE and apoB FCR. Moreover, studies have reported the accumulation of apoE-poor VLDL particles in untreated familial combine hyperlipidemic and familial hypertriglyceridemic subjects (32). It is also plausible that the increase in VLDL apoE FCR is due to its redistribution to other lipoproteins, specifically HDL. The redistribution of apoE from VLDL to HDL during LPL-mediated hydrolysis of VLDL triglycerides and its subsequent transfer back to TRL particles is well established (33–35). The change in VLDL apoC-III metabolism may also modulate the effect of apoE on VLDL particle metabolism, given the strong association between change in VLDL apoE and VLDL apoC-III kinetics with fenofibrate. Of note, change in VLDL apoE concentration was an independent predictor of change in VLDL apoB concentration in a model that included change in VLDL apoC-III concentration (data not shown). This suggests that VLDL apoE is a determinant of VLDL particle catabolism with fenofibrate treatment. In addition, VLDL particle size was decreased with fenofibrate, as evidence by the decrease in VLDL triglyceride:apoB ratio. ApoE on smaller and less triglyceride-enriched VLDL particles has higher affinity for hepatic and peripheral lipoprotein receptors, and it may be preferentially removed from the circulation (5, 36).

Effect of atorvastatin on VLDL apoE metabolism

Atorvastatin decreased VLDL apoE concentration chiefly by increasing VLDL apoE FCR. The increase in VLDL apoE FCR may be explained, in part, by increased direct removal of VLDL apoE from circulation, given its role as a ligand for hepatic and/or peripheral lipoprotein receptors (31). It is also plausible that the increase in VLDL apoE FCR may be due to its redistribution to other lipoproteins, specifically HDL, during LPL-mediated hydrolysis of VLDL triglycerides (33–35).

In contrast to fenofibrate, the associations between VLDL apoE and VLDL apoB FCR on atorvastatin were not statistically significant. An explanation for the uncoupling of VLDL apoE and VLDL apoB FCR is unclear but may relate to decreased apoA-V concentration with atorvastatin. ApoA-V may facilitate TRL and HSPG interactions in vivo and enhance lipoprotein particle internalization and catabolism (37). It is, therefore, conceivable that VLDL particles containing both apoA-V and apoE may be preferentially cleared from circulation via a rapid “secretion-capture” mechanism (37, 38). Hence, altered apoA-V metabolism may modulate the effect of apoE on VLDL catabolism with atorvastatin.

We did not observe a significant change in VLDL apoE PR with atorvastatin. Although previous in vitro and animal studies have suggested a potential inhibitory effect of atorvastatin on apoE mRNA expression (39, 40), recent studies in normolipidemic and hypercholesterolemic subjects and in subjects with type 2 diabetes showed that statin treatment, particularly atorvastatin and simvastatin treatments, did not modify apoE mRNA expression (41, 42), consistent with our findings. We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that the lack of change in VLDL apoE PR is due only to a lack of change in apoE mRNA expression. It is plausible that hepatic apoE mRNA expression was decreased, while the transport of apoE from other lipoprotein fractions, such as HDL, increased, resulting in no net change to VLDL apoE PR with atorvastatin.

Several limitations are noteworthy. ApoE exists in three common isoforms in humans (apoE2, apoE3, and apoE4) that may differ in their lipoprotein distribution, plasma metabolism, and receptor binding properties (5, 36). Our study focused on total VLDL apoE kinetics. Future studies on the effect of fenofibrate and atorvastatin on the metabolism of apoE isoforms are warranted. We were unable to obtain the full apoE genotype for individual subjects due to ethical reasons. Subjects with the apoE2/E2 genotype were excluded. Furthermore, findings from the Genetic of Lipid Lowering and Diet Network (GOLDN) study suggested that APOE alleles did not have an effect on lipid changes to fenofibrate (43). The kinetics of HDL apoE were not examined in our subjects. Previous studies suggest that atorvastatin altered apoE distribution between VLDL and HDL in type 2 diabetic subjects (20). Therefore, the reported increase in VLDL apoE FCR with fenofibrate and atorvastatin may represent increased removal of VLDL apoE into tissues or organs, with or without the whole VLDL particle, or a greater fraction of VLDL apoE that is transported to HDL per unit time. Likewise, the observed reduction in VLDL apoE PR with fenofibrate may suggest a reduction in apoE secreted directly by the liver and/or transported into VLDL from the HDL pool. Future studies to examine the effect of fenofibrate and atorvastatin on HDL apoE metabolism are warranted. Although this study was restricted to men, our findings may apply to women and subjects of different ethnicities; however, this requires further investigation. Measurements of lipases in postheparin plasma may have corroborated our findings. Finally, the effect of different doses of atorvastatin and fenofibrate on apoE transport in the metabolic syndrome also merits investigation.

Implications and conclusions

Given growing evidence that elevated plasma triglyceride concentration represents an independent risk factor for premature CVD, understanding the metabolic determinants of TRL metabolism is clinically important (44). ApoE plays a critical role in regulating TRL metabolism. Therefore, apoE could be a specific a target of new therapies for dyslipidemia and CVD risk. Studies of apoE mimetics, such as Ac-hE18A-NH2, which may act as ligands to reduce atherogenic lipoproteins even in the absence of functional LDL receptors, are currently under way (45).

In addition, a better understanding of the impact of apoE isoform on lipoprotein metabolism, plasma concentrations, and the tissues where it is synthesized and secreted (5, 13, 46) is required. Of note, a consensus regarding optimal plasma apoE target concentration should be determined, given that too high or too low a concentration of apoE may be detrimental, as evidenced by apoE overexpression and knockout studies (13).

Our study, nevertheless, provides new insights into the mechanisms by which two widely used lipid-lowering agents regulate VLDL apoE metabolism in subjects with the metabolic syndrome, and it calls for renewed commitment to better understand the metabolism of this apoprotein.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms. Jock Ian Foo, who performed the laboratory analyses.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- CVD

- cardiovascular disease

- FCR

- fractional catabolic rate

- HOMA

- homeostasis model assessment

- HSPG

- heparin sulfate proteoglycan

- MetS

- metabolic syndrome

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- PR

- production rate

- TRL

- triglyceride-rich lipoprotein

This work was supported by a research grant from the University of Western Australia. E.M.M.O. and T.W.K.N. are National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia postdoctoral research fellows. D.C.C. is an NHMRC career development fellow. P.H.R.B. is an NHMRC senior research fellow.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scott R., Donoghoe M., Watts G. F., O'Brien R., Pardy C., Taskinen M. R., Davis T. M., Colman P. G., Manning P., Fulcher G., et al. 2011. Impact of metabolic syndrome and its components on cardiovascular disease event rates in 4900 patients with type 2 diabetes assigned to placebo in the FIELD randomised trial. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 10: 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan D. C., Barrett H. P., Watts G. F. 2004. Dyslipidemia in visceral obesity: mechanisms, implications, and therapy. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs. 4: 227–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ginsberg H. N. 2000. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Invest. 106: 453–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weisgraber K. H. 1994. Apolipoprotein E: structure-function relationships. Adv. Protein Chem. 45: 249–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahley R. W., Rall S. C., Jr 2000. Apolipoprotein E: far more than a lipid transport protein. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 1: 507–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Beer F., van Dijk K.W., Jong M. C., van Vark L. C., van der Zee A., Hofker M. H., Fallaux F. J., Hoeben R. C., Smelt A. H., Havekes L. M. 2000. Apolipoprotein E2 (Lys146→Gln) causes hypertriglyceridemia due to an apolipoprotein E variant-specific inhibition of lipolysis of very low density lipoproteins-triglycerides. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20: 1800–1806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jong M. C., Dahlmans V. E., Hofker M. H., Havekes L. M. 1997. Nascent very-low-density lipoprotein triacylglycerol hydrolysis by lipoprotein lipase is inhibited by apolipoprotein E in a dose-dependent manner. Biochem. J. 328: 745–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuipers F., Jong M. C., Lin Y., Eck M., Havinga R., Bloks V., Verkade H. J., Hofker M. H., Moshage H., Berkel T. J., et al. 1997. Impaired secretion of very low density lipoprotein-triglycerides by apolipoprotein E-deficient mouse hepatocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 100: 2915–2922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang Y., Ji Z. S., Brecht W. J., Rall S. C., Jr, Taylor J. M., Mahley R. W. 1999. Overexpression of apolipoprotein E3 in transgenic rabbits causes combined hyperlipidemia by stimulating hepatic VLDL production and impairing VLDL lipolysis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19: 2952–2959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maugeais C., Tietge U. J., Tsukamoto K., Glick J. M., Rader D. J. 2000. Hepatic apolipoprotein E expression promotes very low density lipoprotein-apolipoprotein B production in vivo in mice. J. Lipid Res. 41: 1673–1679 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mensenkamp A. R., Jong M. C., van Goor H., van Luyn M. J., Bloks V., Havinga R., Voshol P. J., Hofker M. H., van Dijk K. W., Havekes L. M., et al. 1999. Apolipoprotein E participates in the regulation of very low density lipoprotein-triglyceride secretion by the liver. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 35711–35718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsukamoto K., Maugeais C., Glick J. M., Rader D. J. 2000. Markedly increased secretion of VLDL triglycerides induced by gene transfer of apolipoprotein E isoforms in apoE-deficient mice. J. Lipid Res. 41: 253–259 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtiss L. K., Boisvert W. A. 2000. Apolipoprotein E and atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 11: 243–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennet A. M., Di Angelantonio E., Ye Z., Wensley F., Dahlin A., Ahlbom A., Keavney B., Collins R., Wiman B., de Faire U., et al. 2007. Association of apolipoprotein E genotypes with lipid levels and coronary risk. JAMA. 298: 1300–1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mooijaart S. P., Berbee J. F., van Heemst D., Havekes L. M., de Craen A. J., Slagboom P. E., Rensen P. C., Westendorp R. G. 2006. ApoE plasma levels and risk of cardiovascular mortality in old age. PLoS Med. 3: e176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brunzell J. D., Davidson M., Furberg C. D., Goldberg R. B., Howard B. V., Stein J. H., Witztum J. L. 2008. Lipoprotein management in patients with cardiometabolic risk: consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Diabetes Care. 31: 811–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reyes-Soffer G., Rondon-Clavo C., Ginsberg H. N. 2011. Combination therapy with statin and fibrate in patients with dyslipidemia associated with insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 12: 1429–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lefebvre P., Chinetti G., Fruchart J. C., Staels B. 2006. Sorting out the roles of PPAR alpha in energy metabolism and vascular homeostasis. J. Clin. Invest. 116: 571–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan D. C., Watts G. F., Barrett P. H., Beilin L. J., Redgrave T. G., Mori T. A. 2002. Regulatory effects of HMG CoA reductase inhibitor and fish oils on apolipoprotein B-100 kinetics in insulin-resistant obese male subjects with dyslipidemia. Diabetes. 51: 2377–2386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bach-Ngohou K., Ouguerram K., Frenais R., Maugere P., Ripolles-Piquer B., Zair Y., Krempf M., Bard J. M. 2005. Influence of atorvastatin on apolipoprotein E and AI kinetics in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 315: 363–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohn J. S., Tremblay M., Batal R., Jacques H., Veilleux L., Rodriguez C., Barrett P. H., Dubreuil D., Roy M., Bernier L., et al. 2002. Effect of atorvastatin on plasma apoE metabolism in patients with combined hyperlipidemia. J. Lipid Res. 43: 1464–1471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan D. C., Watts G. F., Ooi E. M., Ji J., Johnson A. G., Barrett P. H. 2008. Atorvastatin and fenofibrate have comparable effects on VLDL-apolipoprotein C–III kinetics in men with the metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28: 1831–1837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watts G. F., Barrett P. H., Ji J., Serone A. P., Chan D. C., Croft K. D., Loehrer F., Johnson A. G. 2003. Differential regulation of lipoprotein kinetics by atorvastatin and fenofibrate in subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 52: 803–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults 2001. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 285: 2486–2497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Batal R., Tremblay M., Barrett P. H., Jacques H., Fredenrich A., Mamer O., Davignon J., Cohn J. S. 2000. Plasma kinetics of apoC-III and apoE in normolipidemic and hypertriglyceridemic subjects. J. Lipid Res. 41: 706–718 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohn J. S., Batal R., Tremblay M., Jacques H., Veilleux L., Rodriguez C., Mamer O., Davignon J. 2003. Plasma turnover of HDL apoC-I, apoC-III, and apoE in humans: in vivo evidence for a link between HDL apoC-III and apoA-I metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 44: 1976–1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bach-Ngohou K., Ouguerram K., Nazih H., Maugere P., Ripolles-Piquer B., Zair Y., Frenais R., Krempf M., Bard J. M. 2002. Apolipoprotein E kinetics: influence of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 26: 1451–1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurano M., Iso O., Hara M., Ishizaka N., Moriya K., Koike K., Tsukamoto K. 2011. LXR agonist increases apoE secretion from HepG2 spheroid, together with an increased production of VLDL and apoE-rich large HDL. Lipids Health Dis. 10: 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas J., Bramlett K. S., Montrose C., Foxworthy P., Eacho P. I., McCann D., Cao G., Kiefer A., McCowan J., Yu K. L., et al. 2003. A chemical switch regulates fibrate specificity for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) versus liver X receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 2403–2410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heeren J., Beisiegel U., Grewal T. 2006. Apolipoprotein E recycling: implications for dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26: 442–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahley R. W., Huang Y. 1999. Apolipoprotein E: from atherosclerosis to Alzheimer's disease and beyond. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 10: 207–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evans A. J., Huff M. W., Wolfe B. M. 1989. Accumulation of an apoE-poor subfraction of very low density lipoprotein in hypertriglyceridemic men. J. Lipid Res. 30: 1691–1701 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blum C. B. 1982. Dynamics of apolipoprotein E metabolism in humans. J. Lipid Res. 23: 1308–1316 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gregg R. E., Zech L. A., Schaefer E. J., Brewer H. B., Jr 1984. Apolipoprotein E metabolism in normolipoproteinemic human subjects. J. Lipid Res. 25: 1167–1176 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibson J. C., Brown W. V. 1988. Effect of lipoprotein lipase and hepatic triglyceride lipase activity on the distribution of apolipoprotein E among the plasma lipoproteins. Atherosclerosis. 73: 45–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hatters D. M., Peters-Libeu C. A., Weisgraber K. H. 2006. Apolipoprotein E structure: insights into function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31: 445–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lookene A., Beckstead J. A., Nilsson S., Olivecrona G., Ryan R. O. 2005. Apolipoprotein A-V-heparin interactions: implications for plasma lipoprotein metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 25383–25387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahley R. W., Ji Z. S. 1999. Remnant lipoprotein metabolism: key pathways involving cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans and apolipoprotein E. J. Lipid Res. 40: 1–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Felgines C., Serougne C., Mathe D., Mazur A., Lutton C. 1994. Effect of simvastatin treatment on plasma apolipoproteins and hepatic apolipoprotein mRNA levels in the genetically hypercholesterolemic rat (RICO). Life Sci. 54: 361–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitchell A., Fidge N., Griffiths P. 1993. The effect of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor simvastatin and of cholestyramine on hepatic apolipoprotein mRNA levels in the rat. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1167: 9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cerda A., Genvigir F. D., Willrich M. A., Arazi S. S., Bernik M. M., Dorea E. L., Bertolami M. C., Faludi A. A., Hirata M. H., Hirata R. D. 2011. Apolipoprotein E mRNA expression in mononuclear cells from normolipidemic and hypercholesterolemic individuals treated with atorvastatin. Lipids Health Dis. 10: 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guan J. Z., Tamasawa N., Murakami H., Matsui J., Tanabe J., Matsuki K., Yamashita M., Suda T. 2008. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, simvastatin improves reverse cholesterol transport in type 2 diabetic patients with hyperlipidemia. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 15: 20–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Irvin M. R., Kabagambe E. K., Tiwari H. K., Parnell L. D., Straka R. J., Tsai M., Ordovas J. M., Arnett D. K. 2010. Apolipoprotein E polymorphisms and postprandial triglyceridemia before and after fenofibrate treatment in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering and Diet Network (GOLDN) Study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 3: 462–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller M., Stone N. J., Ballantyne C., Bittner V., Criqui M. H., Ginsberg H. N., Goldberg A. C., Howard W. J., Jacobson M. S., Kris-Etherton P. M., et al. 2011. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 123: 2292–2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharifov O. F., Nayyar G., Garber D. W., Handattu S. P., Mishra V. K., Goldberg D., Anantharamaiah G. M., Gupta H. 2011. Apolipoprotein E mimetics and cholesterol-lowering properties. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs. 11: 371–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nieminen T., Kahonen M., Viiri L. E., Gronroos P., Lehtimaki T. 2008. Pharmacogenetics of apolipoprotein E gene during lipid-lowering therapy: lipid levels and prevention of coronary heart disease. Pharmacogenomics. 9: 1475–1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]