Abstract

Objective: To assess varying levels of response to aripiprazole adjunctive to standard antidepressant therapy (ADT) and the predictive value of an early response for a sustained response.

Method: This post hoc analysis of 3 similarly designed randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 studies investigated the efficacy and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole to standard ADT in patients with major depressive disorder (DSM-IV-TR criteria) who had a prior inadequate response to 1–3 ADTs (CN138-139 [September 2004–December 2006], CN138-163 [June 2004–April 2006], and CN138-165 [March 2005–April 2008]). Response levels were defined as percent decreases from baseline in Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score after 6 weeks of treatment, with a ≤ 25% decrease for minimal, > 25 to < 50% decrease for partial, ≥ 50% to < 75% decrease for moderate, and ≥ 75% decrease for a robust response to treatment.

Results: More patients receiving adjunctive aripiprazole exhibited a partial (23.9% vs 17.9%, P = .017), moderate (23.1% vs 15.0%, P < .001), and robust response (14.3% vs 7.4%, P < .001) compared with adjunctive placebo. Adjunctive aripiprazole treatment compared with adjunctive placebo treatment was associated with a significantly greater proportion of patients achieving an early response (week 2, ≥ 50% reduction in MADRS total score, n = 110/539 vs n = 47/525, P < .001, number needed to treat = 9) and an endpoint response (relative risk = 1.7, 95% CI = 1.4–2.0, P < .001, number needed to treat = 7). A univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that an early response was a significant predictor of endpoint remission (P < .001).

Conclusions: Aripiprazole augmentation was associated with a significantly greater proportion of patients achieving a partial, moderate, or robust response to treatment compared with ADT alone. Patients showing an early response (week 2) to augmentation maintained their response through endpoint, suggesting that clinicians may make clinically meaningful decisions early during treatment.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT00095823, NCT00095758, and NCT00105196

Clinical Points

▪ The delayed onset of the therapeutic effect (∼4–6 weeks) of antidepressant therapy (ADT) places patients at risk for continued morbidity (eg, suicide or other personal crises) even after the patient and clinician have decided to begin or adjust treatment.

▪ The findings show that augmentation of ADT with aripiprazole results in an early (week 2) and more robust response to treatment than with continued antidepressant monotherapy.

▪ This early response to adjunctive aripiprazole allows clinicians to reduce the morbidity risk and to make clinically meaningful decisions soon after treatment initiation.

It has been presumed in clinical practice that it takes 6 to 8 weeks to see the initial effects of antidepressant therapy (ADT) and up to 4 months to observe clinically meaningful improvements in the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD).1,2 Consequently, clinical practice guidelines such as those from the American Psychiatric Association recommend reevaluating ADT if moderate improvements are not seen after 4 to 8 weeks of treatment,3 whereas the American College of Physicians recommends regularly assessing patient status, therapeutic response, and adverse effects of ADT starting within 1 to 2 weeks from the initiation of therapy.1

Recent clinical evidence has shown that ADT efficacy can be assessed within 1 to 2 weeks of therapy and used as a significant predictor of subsequent clinical outcome.2 In response to this evidence, the International Consensus Group on Depression has recommended assessing the efficacy of ADT after 2 to 4 weeks of treatment.4 In support of this recommendation, recent evidence has shown that patients receiving adjunctive antipsychotics to ADT, who show improvements as early as the second week of treatment (≥ 20% decrease in symptom rating scales), are more likely to attain a response or remission by week 6 than patients receiving ADT alone.5 Moreover, an analysis assessing the predictive value of early improvement with aripiprazole adjunctive to ADT compared with placebo showed that early improvement in depression symptoms was the most significant predictor of remission, with high sensitivity and high negative predictive values.6

Consequently, assessing the predictive value of an early response or nonresponse to adjunctive treatment may provide a clinically meaningful tool for clinicians and patients, as it allows clinicians to make important decisions early during treatment, such as whether to adjust the medication dose or to maintain the current treatment and reassess at a later time. To assess the onset of treatment efficacy, it is important to determine a priori how efficacy is going to be defined and measured, with the selection of the appropriate rating scale being essential for assessing improvements in disease severity.7 A common criterion for response to ADT is a ≥ 50% reduction from baseline in symptom severity scale scores, with the criterion for early improvement being a ≥ 20% reduction in severity scale score within 2 to 4 weeks from the initiation of treatment.

In the current post hoc analysis, early response was defined using a relatively stringent definition, ie, as a ≥ 50% reduction in Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)8 total score by week 2 from the initiation of treatment. Endpoint response categories were defined by quartiles on the basis of percentage reduction in MADRS total score—minimal response (≤ 25%), partial response (> 25% to < 50%), moderate response (≥ 50% to < 75%), and robust response (≥ 75%)—from baseline to the end of augmentation treatment (week 6). Data were pooled from 3 similar studies of aripiprazole augmentation to ADT (CN138-139, CN138-163, and CN138-165) in patients with MDD and an inadequate response to 1–3 prior ADTs. The results were analyzed to assess whether early response to adjunctive aripiprazole treatment was predictive of a sustained response to medication. An additional objective of this analysis was to evaluate the proportion of patients receiving adjunctive aripiprazole who achieved various levels of response, as assessed by changes in the MADRS total score, and the time course of those improvements.

METHOD

Study Design

Details of the studies’ methods have been described previously.9–11 Briefly, 3 similarly designed multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 studies (CN138-139 [September 2004–December 2006], CN138-163 [June 2004–April 2006], and CN138-165 [March 2005–April 2008]) were conducted in the United States to investigate the efficacy and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole with standard ADT in patients with MDD who showed an inadequate response (defined as a < 50% reduction in severity of depressive symptoms) to at least 1 historical and 1 prospective ADT but ≤ 3 adequate ADT trials of ≥ 6 weeks’ duration (≥ 3 weeks for combination treatments) at the minimum dose specified in the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire.12The studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki; the ethics committee at each site approved the protocol. All participants provided written informed consent. The studies were registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (identifiers: NCT00095823[CN138-139], NCT00095758[CN138-163], and NCT00105196[CN138-165]).

Details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria have been reported previously.9–11 Eligible patients were aged 18–65 years and had MDD (DSM-IV-TR criteria) lasting ≥ 8 weeks and a 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17) total score ≥ 18. Patients with a diagnosis of bipolar I or II disorder were excluded per study protocol.

The studies comprised 3 phases: a screening phase (7–28 days) during which prohibited medications (including benzodiazepines and hypnotic agents) were discontinued, a prospective ADT phase (8 weeks) to document inadequate response to ADT, and a randomization phase (6 weeks; actual study visits weeks 9–14). During the 8-week ADT prospective phase (phase B), patients received escitalopram (10 or 20 mg/d), fluoxetine (20 or 40 mg/d), paroxetine controlled release (37.5 or 50 mg/d), sertraline (100 or 150 mg/d), or venlafaxine extended release (150 or 225 mg/d), per investigator choice under standard dosing guidelines, along with single-blind, adjunctive placebo. Patients were not told when the second phase ended and the third phase began.9–11

Patients with an inadequate response at the end of the second phase (< 50% reduction in HDRS-17 total score, a HDRS-17 score ≥ 14, and a Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement of Illness [CGI-I] scale score ≥ 3) were randomly assigned in a double-blind fashion to either continue adjunctive placebo or substitute placebo with adjunctive aripiprazole (2–20 mg/d, starting dose 5 mg/d) for an additional 6 weeks of treatment (phase C). For patients who received aripiprazole as an adjunct to paroxetine controlled release or fluoxetine, 15 mg/d was the maximum dose of aripiprazole.9–11

Measures and Quartile Response Categories

Quartile response categories were defined on the basis of percentage reduction in the MADRS total score at the end of phase C (week 6), relative to the end of phase B (week 0), as follows: phase C minimal response (≤ 25%), phase C partial response (> 25% to < 50%), phase C moderate response (≥ 50% to < 75%), and phase C robust response (≥ 75%). These quartile response categories have been adapted from an operational classification of the degree of treatment resistance described by Fava and Davidson.13

Early response was defined as a ≥ 50% reduction in MADRS scores at week 2 of phase C. Endpoint response was defined as a ≥ 50% reduction in MADRS scores at week 6 of phase C. Remission was defined as a MADRS total score ≤ 10 and a ≥ 50% reduction in MADRS total score from the end of phase B to study endpoint.9–11

Statistical Analysis

The proportion of adjunctive placebo versus adjunctive aripiprazole–treated patients who achieved a response was compared for each category using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. Changes from baseline in mean MADRS total score at weeks 1–6 (phase C) were compared between treatments using analysis of covariance. Comparison of slope estimates between treatments was performed using repeated-measures analysis (mixed-effects model for repeated measures)14 on MADRS total score at week 2. The predictive value of early response was calculated using univariate logistic regression on data from 2 trials (CN138-139 and CN138-163) and confirmed using data from the third trial (CN138-165).

Numbers needed to treat (NNT) for an early response (week 2) and endpoint response (week 6) were calculated as 1 ÷ (percentage of aripiprazole responders − percentage of placebo responders) and rounded to the nearest integer.

RESULTS

The baseline demographic and psychiatric characteristics of randomized patients by phase C early response status to adjunctive aripiprazole or adjunctive placebo treatment are shown in Table 1 and were similar between phase C early responders and early nonresponders to adjunctive treatment. Interestingly, phase C early responders receiving aripiprazole had experienced fewer prior depressive episodes (4.4) than phase C early nonresponders (5.5). The baseline demographic and psychiatric characteristics for phase C early responders and early nonresponders receiving adjunctive placebo were similar to those of patients receiving adjunctive aripiprazole (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Psychiatric Characteristics of Randomized Patients by Early Response Statusa

| Phase C Early Responders (n = 157) |

Phase C Early Nonresponders (n = 907) |

|||

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 47) | Aripiprazole (n = 110) | Placebo (n = 478) | Aripiprazole (n = 429) |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 44.7 (10.7) | 46.2 (10.2) | 44.9 (10.9) | 45.3 (10.9) |

| Sex, n (%), male | 10 (21.3) | 19 (17.3) | 163 (34.1) | 151 (35.2) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 86.0 (24.9) | 83.1 (21.7) | 87.9 (22.0) | 85.9 (20.1) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 31.2 (9.2) | 30.1 (7.4) | 30.9 (7.5) | 30.3 (7.1) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 41 (87.2) | 98 (89.1) | 429 (89.7) | 378 (88.1) |

| Black | 5 (10.6) | 11 (10.0) | 36 (7.5) | 30 (7.0) |

| Other | 1 (2.1) | 1 (0.9) | 13 (2.7) | 21 (4.9) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 45 (95.7) | 102 (92.7) | 440 (92.1) | 412 (96.3) |

| Psychiatric characteristics | ||||

| Duration of current episode, median (SD), mo | 14.7 (35.9) | 22.8 (66.2) | 19.6 (67.5) | 17.8 (65.0) |

| Age of first depressive episode, mean (SD), y | 28.3 (13.7) | 26.7 (12.0) | 27.2 (13.4) | 27.4 (13.3) |

| No. of depressive episodes, mean (SD) | 4.4 (4.0) | 4.4 (3.5) | 6.0 (11.6) | 5.5 (9.8) |

| Antidepressant therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Escitalopram | 14 (29.8) | 31 (28.2) | 137 (28.7) | 143 (33.3) |

| Fluoxetine | 5 (10.6) | 14 (12.7) | 71 (14.9) | 70 (16.3) |

| Paroxetine controlled release | 6 (12.8) | 9 (8.2) | 41 (8.6) | 34 (7.9) |

| Sertraline | 14 (29.8) | 18 (16.4) | 90 (18.8) | 71 (16.6) |

| Venlafaxine extended release | 8 (17.0) | 38 (34.5) | 139 (29.1) | 111 (25.9) |

| Previous antidepressant therapy trials to current episode, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | … | … | 5 (1.0) | 3 (0.7) |

| 1 | 35 (74.5) | 74 (67.3) | 316 (66.2) | 299 (69.9) |

| 2 | 11 (23.4) | 29 (26.4) | 129 (27.0) | 102 (23.8) |

| ≥ 3 | 1 (2.1) | 7 (6.4) | 27 (5.7) | 24 (5.6) |

Early response was defined as a ≥ 50% reduction in Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale total score at week 2.

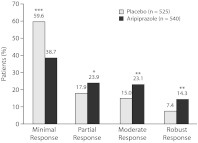

Adjunctive aripiprazole was associated with a significantly greater proportion of patients exhibiting a phase C partial response (23.9% vs 17.9%, P = .017), moderate response (23.1% vs 15.0%, P < .001), and robust response (14.3% vs 7.4%, P < .001) compared with adjunctive placebo treatment, as assessed by reductions in MADRS total score between baseline and endpoint (week 6) (Figure 1). Conversely, adjunctive placebo was associated with a significantly higher proportion of patients exhibiting a phase C minimal response to treatment compared with adjunctive aripiprazole (59.6% vs 38.7%, P < .001) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Endpoint MADRS Quartile Response Analysis: Percent of Patients With a Response as Assessed by Reductions in MADRS Total Score at Endpoint (Week 6)a

aResponse quartiles on MADRS total score: minimal (≤ 25%), partial (> 25% to < 50%), moderate (≥ 50% to < 75%), and robust (≥ 75%).

*P = .017 vs adjunctive placebo.

**P < .001 vs adjunctive placebo.

**P < .001 vs adjunctive aripiprazole.

Abbreviation: MADRS = Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale.

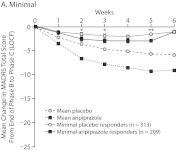

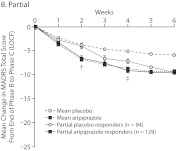

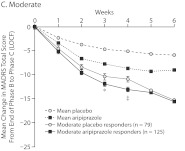

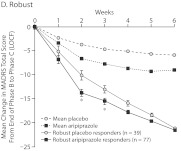

Figure 2A–D shows the time course of changes in MADRS total score from baseline to endpoint by study week. The quartile response analysis revealed that phase C partial and robust responders to adjunctive aripiprazole exhibited significant improvements in MADRS total score as early as week 2 (Figure 2B and D, respectively), whereas phase C moderate responders to adjunctive aripiprazole exhibited significant improvements as early as week 3 (Figure 2C), compared with adjunctive placebo-treated patients. Interestingly, phase C minimal responders receiving adjunctive aripiprazole showed significant improvements as early as week 2 compared with phase C minimal responders receiving adjunctive placebo (Figure 2A). However, the mean changes in MADRS total score for phase C minimal responders to either adjunctive aripiprazole or adjunctive placebo were smaller than the overall mean placebo and mean aripiprazole responses, which were calculated on the observed overall mean change during the randomized phase (Figure 2A–D).

Figure 2.

Weekly Mean Changes in MADRS Scores by Quartile Response Category: (A) Minimal, (B) Partial, (C) Moderate, and (D) Robusta,b

a Mean placebo and mean aripiprazole response are based on the overall mean change in MADRS total score from the end of phase B to the end of phase C observed in all participants from the 3 pooled studies (last observation carried forward).

b For quartile response group treatment comparisons by study week: *P < .05, **P < .005, †P < .001, and ‡P = .005.

Abbreviation: MADRS = Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale.

Slope analyses on MADRS total score at week 2 for patients showing a response at endpoint (≥ 50% reduction in MADRS total score) are shown in Table 2. In the combined phase C moderate and robust response group analysis (all responders), the difference of slope estimates between adjunctive aripiprazole and adjunctive placebo was –1.0 (95% confidence interval [CI] = –1.8 to –0.3), indicating a faster decrease in MADRS total score for adjunctive aripiprazole–treated patients compared with adjunctive placebo–treated patients over the first 2 weeks of treatment. Individual phase C moderate and robust response subgroup analyses showed similar trends. In the phase C moderate response group, the difference of slope estimates was –0.7 (95% CI = –1.5 to 0.1), whereas the difference of slope estimates in the phase C robust response group was –1.5 (95% CI = –3.0 to 0.1).

Table 2.

Slope Analyses on Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) Total Score at Week 2 for Patients Showing a Response at Endpoint (≥ 50% reduction in MADRS total score)

| Slope Estimate (95% CI) |

|||

| Adjunctive Placebo | Adjunctive Aripiprazole | Difference of Slope Estimates | |

| Moderate responders (≥ 50% and < 75%) | n = 79 | n = 125 | −0.7 (–1.5 to 0.1) |

| −4.1 (–4.7 to –3.5) | −4.8 (–5.3 to –4.3) | ||

| Robust responders (≥ 75%) | n = 39 | n = 77 | −1.5 (–3.0 to 0.1) |

| −5.6 (–6.9 to –4.4) | −7.1 (–8.0 to –6.2) | ||

| All responders (≥ 50%)a | n = 118 | n = 202 | −1.0 (–1.8 to –0.3) |

| −4.6 (–5.2 to –4.0) | −5.7 (–6.1 to –5.2) | ||

Includes patients exhibiting a ≥ 50% reduction in MADRS total score at week 6.

Adjunctive aripiprazole treatment compared with adjunctive placebo treatment was associated with a significantly greater proportion of patients achieving a phase C early response at week 2 (110/539 [20.4%] vs 47/525 [9.0%], P < .001) and an endpoint response at week 6 (202/540 [37.4%] vs 118/525 [22.5%], P < .001). The relative risk of an early response for patients receiving adjunctive aripiprazole compared with adjunctive placebo was 2.28 (95% CI = 1.7–3.1), whereas the relative risk for an endpoint response for patients receiving adjunctive aripiprazole compared with adjunctive placebo was 1.7 (95% CI = 1.4–2.0, P < .001). Numbers needed to treat (NNTs) were 9 and 7 for response at week 2 and week 6, respectively.

For patients receiving adjunctive aripiprazole, 37.3% (41/110) of phase C early responders showed a moderate response at endpoint, whereas 42.7% (47/110) of phase C early responders showed a robust response at endpoint. In addition, phase C early responders who achieved a robust response at endpoint showed further significant decreases in MADRS total score between weeks 2 and 6 (mean change = –4.49, 95% CI = –5.61 to –3.36, P < .05). For patients receiving adjunctive placebo, 38.3% (18/47) of phase C early responders showed a moderate response at endpoint, and an additional 38.3% (18/47) of phase C early responders showed a robust response at endpoint. Patients who received adjunctive placebo maintained the improvements in MADRS total score achieved at week 2 through endpoint at week 6.

In addition, a univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that an early response at week 2 (≥ 50% reduction in MADRS total score) was a predictor of endpoint remission (MADRS total score of ≤ 10 and a ≥ 50% reduction in MADRS total score at week 6, P < .001). Indeed, data from the main analysis (pooled data from CN138-139 and CN138-163) showed that 61.1% (44/72) of patients receiving adjunctive aripiprazole who exhibited a phase C early response (week 2) achieved remission (odds ratio [OR] = 7.7, 95% CI = 4.4–13.5), whereas 62.5% (20/32) of patients receiving adjunctive placebo who exhibited a phase C early response achieved remission (OR = 13.8, 95% CI = 6.2–30.5). A small proportion of patients who received adjunctive aripiprazole (17.0%, 50/294) or adjunctive placebo (10.8%, 35/324) did not exhibit an early response but achieved remission by study endpoint. The ORs from the main analysis (CN138-139 and CN138-163) were similar to the ORs calculated for the third study (CN138-165), which were used to validate the analysis. In the validation analysis, 84.2% (32/38) of patients receiving adjunctive aripiprazole who exhibited a phase C early response achieved remission (OR = 17.9, 95% CI = 6.9–46.7), whereas 60.0% (9/15) of patients receiving adjunctive placebo who exhibited a phase C early response achieved remission (OR = 8.5, 95% CI = 2.8–26.3). Similar to the main analysis, the validation analysis showed that 23.0% (31/135) of patients receiving adjunctive aripiprazole did not show a phase C early response but did achieve remission, as did 14.9% (23/154) of patients receiving adjunctive placebo.

Adverse events reported by ≥ 5% of patients in either double-blind treatment group in the randomized phase are shown in Table 3. The incidence of adverse events was similar between phase C early responders and early nonresponders. The most common adverse events reported by phase C early responders who received adjunctive aripiprazole compared with adjunctive placebo were akathisia (27.3% vs 6.4%), restlessness (16.4% vs 4.3%), fatigue (11.8% vs 4.3%), upper respiratory tract infection (8.2% vs 12.8%), and headache (8.2% vs 12.8%). The most common adverse events reported by phase C early nonresponders who received adjunctive aripiprazole compared with adjunctive placebo were akathisia (21.4% vs 4.0%), restlessness (11.2% vs 2.3%), insomnia (8.2% vs 3.1%), headache (7.7% vs 9.8%), and fatigue (7.7% vs 4.0%).

Table 3.

Adverse Events Reported by ≥ 5% of Patients in Either Double-Blind Treatment Group During Phase Ca,b

| Early Responders |

Early Nonresponders |

|||

| Adverse Event | Placebo (n = 47) | Aripiprazole (n = 110) | Placebo (n = 478) | Aripiprazole (n = 429) |

| Akathisia | 3 (6.4) | 30 (27.3) | 19 (4.0) | 92 (21.4) |

| Headache | 6 (12.8) | 9 (8.2) | 47 (9.8) | 33 (7.7) |

| Tremor | 5 (10.6) | 8 (7.3) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Restlessness | 2 (4.3) | 18 (16.4) | 11 (2.3) | 48 (11.2) |

| Insomnia | 1 (2.1) | 8 (7.3) | 15 (3.1) | 35 (8.2) |

| Abnormal dreams | 5 (10.6) | 1 (0.9) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Constipation | 2 (4.3) | 6 (5.5) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Dry mouth | 4 (8.5) | 6 (5.5) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Nausea | 5 (10.6) | 5 (4.5) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Diarrhea | 3 (6.4) | 3 (2.7) | 25 (5.2) | 18 (4.2) |

| Fatigue | 2 (4.3) | 13 (11.8) | 19 (4.0) | 33 (7.7) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 6 (12.8) | 9 (8.2) | 23 (4.8) | 25 (5.8) |

| Blurred vision | 1 (2.1) | 7 (6.4) | 6 (1.3) | 27 (6.3) |

| Somnolence | Not reported | Not reported | 12 (2.5) | 27 (6.3) |

Data are reported as n (%).

Patients may have had more than 1 adverse event but were counted in the overall total only once. Each patient was also counted, at most, once for a particular adverse event, even if the adverse event occurred more than once for the same patient.

DISCUSSION

After 6 weeks of adjunctive aripiprazole to antidepressant monotherapy, more than one-third of patients (37.4%) in the study achieved either a moderate or a robust response compared with patients receiving adjunctive placebo (22.5%). Moreover, after 2 weeks of treatment, patients who received adjunctive aripiprazole had substantially higher response rates (20.4%) than those who received adjunctive placebo (9.0%), with a clinically meaningful NNT of 9. Overall, a significantly greater proportion of patients who received adjunctive aripiprazole exhibited a partial, moderate, or robust response at endpoint compared with patients who received adjunctive placebo and as early as weeks 2 or 3 from the start of adjunctive treatment. Interestingly, patients who exhibited an early response maintained their improvements through endpoint, suggesting that an early response to adjunctive treatment is predictive of a sustained response and may enable clinicians to make decisions about treatment options as early as week 2. It is important to note that a lack of an early response at week 2 should prompt clinicians to reassess and optimize the medication dose before making definitive changes to pharmacotherapy. In the current study, there were a small proportion of patients who did not exhibit an early response (week 2) but who achieved remission at endpoint. Moreover, patients in this study were started at 5 mg/d of adjunctive aripiprazole and were receiving 10 mg/d of aripiprazole by week 2, a more “aggressive” dosing schedule than the 2- to 5–mg/d starting dose recommended in clinical practice.

It has been proposed that the efficacy of adjunctive aripiprazole to antidepressants in the treatment of MDD is due to aripiprazole’s potent partial agonist effect on dopamine D2 and D3 and serotonin-1A (5-HT1A) receptors and its antagonist effect on 5-HT2 receptors—effects thought to mediate the early response to antidepressant action of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).15–19 Evidence consistent with this hypothesis has shown that 2-week augmentation of escitalopram (an SSRI) with aripiprazole increased the firing rate of 5-HT neurons by 48% but not the firing rates of dopaminergic or noradrenergic neurons. The combination of aripiprazole and escitalopram reversed the inhibitory action of escitalopram on the firing rate of 5-HT receptors and noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurons.20 Further support for this hypothesis comes from mirtazapine, a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; studies showed that mirtazapine-treated patients had a 74% higher likelihood of achieving remission during the first 2 weeks of therapy compared with patients treated with SSRIs.5 In addition to increasing noradrenergic and serotonergic neurotransmission through the presumed blockade of α2-autoreceptors, α2-heteroreceptors, and postsynaptic 5-HT2 receptors, mirtazapine mediates the blockade of serotonin receptors, notably the 5-HT2C. The 5-HT2C receptor inhibits the release of dopamine and norepinephrine in the ventral tegmental area, thereby disinhibiting dopamine and norepinephrine activity and causing a pronounced antidepressant and anxiolytic response.16

The safety and tolerability profile of aripiprazole in the current analysis was similar for both early responders and nonresponders to antidepressant monotherapy and was consistent with previous reports on the short-term safety and tolerability of aripiprazole.21,22 Clinicians, however, need to consider potential benefits versus the long-term side effects and safety issues associated with atypical antipsychotic augmentation of antidepressants in patients with an inadequate response to antidepressant monotherapy. Long-term safety issues associated with atypical antipsychotics are specific to each individual agent. Most atypical antipsychotics carry a risk for tardive dyskinesia, which is a major concern for the long-term augmentation treatment of MDD. A long-term safety and tolerability study of aripiprazole adjunctive to ADT in MDD showed a low rate of investigator-reported tardive dyskinesia (n = 4/1,005; 0.4%), and all cases resolved with dose reduction or drug discontinuation.23 Although the risks for weight gain and metabolic syndrome are elevated with olanzapine and, to a lesser degree, with quetiapine and risperidone,24 these risks are rarely associated with aripiprazole.22 Aripiprazole is associated with akathisia in some patients, but this tends to occur early during treatment and usually subsides with dose reduction or antiakathisia treatment, whereas extrapyramidal effects are uncommon.25

Limitations

The findings reported here should be considered in light of potential limitations, such as the post hoc nature of the analysis and the selection of a ≤ 25% reduction in MADRS total score as a subjective threshold to indicate a minimal response to ADT. In addition, patients were not randomized to ADT during the prospective treatment phase, and the relatively small numbers of patients assigned to each ADT regimen precluded the evaluation of the effects of aripiprazole augmentation by the type of ADT received in the prospective phase. The general application of the current findings is somewhat limited by the exclusion of patients who had failed more than 3 prior antidepressant trials, as many patients in real-world practice may have received more than 3 antidepressants. However, it should be noted that the antidepressant trials in this study were of adequate dosage and duration, which may not always be the case in real-world practice. Finally, a 6-week trial does not provide insights into the long-term benefit of aripiprazole augmentation on remission in this difficult-to-treat population.

CONCLUSION

Aripiprazole augmentation to ADT was associated with a significantly greater proportion of patients achieving a partial, moderate, or robust response to treatment compared with adjunctive placebo. Patients exhibiting a response as early as the second week of augmentation treatment maintained their response through the end of the study. Therefore, early response to aripiprazole augmentation may be extremely helpful to both clinicians and patients, as it may facilitate important treatment decisions early in the course of therapy.

Drug names: aripiprazole (Abilify), escitalopram (Lexapro and others), fluoxetine (Prozac and others), mirtazapine (Remeron and others), olanzapine (Zyprexa), paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva, and others), quetiapine (Seroquel), risperidone (Risperdal and others), sertraline (Zoloft and others), venlafaxine (Effexor and others).

Author affiliations: Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon (Dr Casey); Bristol-Myers Squibb, Plainsboro, New Jersey (Dr Laubmeier); Bristol-Myers Squibb, Wallingford, Connecticut (Ms Marler); and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization, Inc, Princeton, New Jersey (Drs Forbes and Baker).

Potential conflicts of interest: Dr Casey has served as a consultant to Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dainippon Sumitomo, Genentech, Janssen, Merck, NuPathe, Pfizer, Solvay, and Wyeth and has served on the speakers bureau for Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Merck, and Pfizer. Dr Laubmeier is an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb. Ms Marler is an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb and has served as a consultant to Alpha Consulting. Drs Forbes and Baker are employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization.

Funding/support: This study was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb (Princeton, New Jersey) and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd (Tokyo, Japan). Editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Ogilvy Healthworld Medical Education (London, United Kingdom); funding for this editorial support was provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Previous presentations: American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; May 22–26, 2010; New Orleans, Louisiana; American College of Neuropsychopharmacology Annual Meeting; December 5–9, 2010; Miami, Florida; and New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit 2011 Meeting; June 13–16, 2011; Boca Raton, Florida.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Madhukar H. Trivedi, MD (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas); Stephen R. Wisniewski, PhD (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania); J. Craig Nelson, MD (University of California at San Francisco); Christina M. Dording, MD (Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston); and Edward S. Friedman, MD (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) for their contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data. Drs Trivedi, Wisniewski, Nelson, Dording, and Friedman report no conflicts of interest related to the subject of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Qaseem A, Snow V, Denberg T, et al. Using second-generation antidepressants to treat depressive disorders: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(10):725–733. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-10-200811180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakajima S, Suzuki T, Watanabe K, et al. Accelerating response to antidepressant treatment in depression: a review and clinical suggestions. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(2):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(10):A34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nutt DJ, Davidson JR, Gelenberg AJ, et al. International consensus statement on major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(suppl E1):e08. doi: 10.4088/JCP.9058se1c.08gry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tohen M, Case M, Trivedi MH, et al. Olanzapine/fluoxetine combination in patients with treatment-resistant depression: rapid onset of therapeutic response and its predictive value for subsequent overall response in a pooled analysis of 5 studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(4):451–462. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04984gre. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muzina DJ, Chambers JS, Camacho TA, et al. Adjunctive aripiprazole for depression: predictive value of early assessment. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:793–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gelenberg AJ, Chesen CL. How fast are antidepressants? J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(10):712–721. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134(4):382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berman RM, Fava M, Thase ME, et al. Aripiprazole augmentation in major depressive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressants. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(4):197–206. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900020216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berman RM, Marcus RN, Swanink R, et al. The efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(6):843–853. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcus RN, McQuade RD, Carson WH, et al. The efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a second multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(2):156–165. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31816774f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandler GM, Iosifescu DV, Pollack MH, et al. RESEARCH: Validation of the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment History Questionnaire (ATRQ) CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16(5):322–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2009.00102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fava M, Davidson KG. Definition and epidemiology of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19(2):179–200. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mallinckrodt CH, Raskin J, Wohlreich MM, et al. The efficacy of duloxetine: a comprehensive summary of results from MMRM and LOCF_ANCOVA in eight clinical trials. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thase ME, Nierenberg AA, Vrijland P, et al. Remission with mirtazapine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from 15 controlled trials of acute phase treatment of major depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(4):189–198. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e328330adb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millan MJ, Gobert A, Rivet J-M, et al. Mirtazapine enhances frontocortical dopaminergic and corticolimbic adrenergic, but not serotonergic, transmission by blockade of alpha2-adrenergic and serotonin2C receptors: a comparison with citalopram. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12(3):1079–1095. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burris KD, Molski TF, Xu C, et al. Aripiprazole, a novel antipsychotic, is a high-affinity partial agonist at human dopamine D2 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302(1):381–389. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.033175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tadori Y, Forbes RA, McQuade RD, et al. Characterization of aripiprazole partial agonist activity at human dopamine D3 receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;597(1–3):27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shapiro DA, Renock S, Arrington E, et al. Aripiprazole, a novel atypical antipsychotic drug with a unique and robust pharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(8):1400–1411. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chernoloz O, El Mansari M, Blier P. Electrophysiological studies in the rat brain on the basis for aripiprazole augmentation of antidepressants in major depressive disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;206(2):335–344. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1611-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson JC, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, et al. Safety and tolerability of adjunctive aripiprazole in major depressive disorder: a pooled post hoc analysis (Studies CN138-139 and CN138-163) Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(6):344–352. doi: 10.4088/PCC.08m00744gre. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fava M, Wisniewski SR, Thase ME, et al. Metabolic assessment of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a pooled analysis of 2 studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(4):362–367. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181ac9b0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berman RM, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of open-label aripiprazole augmentation of antidepressant therapy in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:303–312. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S18333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shelton RC, Papakostas GI. Augmentation of antidepressants with atypical antipsychotics for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117(4):253–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berman R, Thase M, Trivedi M, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of open-label aripiprazole augmentation of antidepressant therapy in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:303–312. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S18333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]