Abstract

Esophageal adenocarcinoma carries a poor prognosis, as it typically presents at a late stage. Thus, a major research priority is the development of novel diagnostic imaging strategies that can detect neoplastic lesions earlier and more accurately than current techniques. Advances in optical imaging allow clinicians to obtain real-time histopathologic information with instant visualization of cellular architecture and the potential to identify neoplastic tissue. The various endoscopic imaging modalities for esophageal neoplasia can be grouped into two major categories: (a) wide-field imaging, a comparatively lower-resolution view for imaging larger surface areas, and (b) high-resolution imaging, which allows individual cells to be visualized. This review will provide an overview of the various forms of real-time optical imaging in the diagnosis and management of Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: Barrett esophagus, neoplasms, cancer, endoscopy, optical imaging, diagnostic imaging

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, incidence rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma have undergone a 400-fold increase over the past several decades (1). Because these cancers are usually detected at an advanced stage, survival rates are uniformly poor, with a recent study showing a five-year survival rate of 17 percent (2). Given these daunting statistics, a great deal of recent research effort has focused on novel diagnostic imaging strategies that can detect these tumors at an early and treatable stage. The natural history of esophageal adenocarcinoma often begins with patients progressing from chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) to intestinal metaplasia of the esophagus, referred to as Barrett's esophagus. Once diagnosed with Barrett's esophagus, patients are entered into a surveillance protocol by the gastroenterologist who periodically performs endoscopic examination of the esophagus and takes random biopsies of the Barrett's-affected area looking for neoplasia, consisting of either high-grade dysplasia or cancer. Although Barrett's esophagus is asymptomatic, this condition is associated with a 30-fold increase in the risk of developing adenocarcinoma, (3) highlighting the pressing need for better endoscopic detection.

Recent advances in high-resolution optical imaging technologies allow clinicians to obtain real-time images showing cellular detail, so-called ‘optical biopsies,’ using various wavelengths and the creative manipulation of light. These optical imaging technologies may change the paradigm of current surveillance protocols for high-risk patients by preventing the unnecessary removal of benign tissue and facilitating real-time decision-making at the point of care, potentially allowing immediate endoscopic resection of neoplastic tissue upon detection. This review will provide an overview of the currently available forms of optical imaging in the management of Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma.

OPTICAL IMAGING MODALITIES

The various endoscopic optical imaging modalities for esophageal cancer can be grouped into two major categories, depending on the spatial resolution obtained from the device: 1) wide-field imaging modalities, for imaging larger surface areas such as seen with conventional white-light video endoscopy, and 2) high-resolution imaging modalities, which obtains images at a microscopic level of detail, allowing individual cells to be visualized. Figure 1 illustrates a schematic of all the imaging modalities to be discussed in this review. Over the last several decades, researchers have studied the optical properties of benign, inflammatory, dysplastic, and cancerous tissue to understand how they can be differentiated with various optical imaging modalities. The technical details of each modality and its advantages and disadvantages for the detection of dysplasia and cancer are discussed below.

Figure 1.

Available point-of-care optical imaging devices for the detection of dysplasia and neoplasia.

Wide-field Imaging Modalities

Endoscopic imaging is the main tool used to screen patients for esophageal cancer, and is also necessary to stage disease and monitor patients for recurrence in post-therapeutic surveillance protocols. In an attempt to improve the diagnostic ability of white light endoscopy, a number of new wide-field imaging modalities are under development. Table 1 outlines some of these imaging modalities, which are becoming used more frequently every day to augment the use of conventional white-light endoscopy in the screening, diagnosis, and management of esophageal neoplasia.

Table 1.

Features of Commonly Used Widefield and High-Resolution Optical Imaging Modalities for the Detection of Barrett's-Associated Neoplasia.

| Device | Advantages | Disadvantages | Sensitivity | Specificity | Reference(s) | Number of Patients (Imaging Sites) in Study | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widefield Modalities | |||||||

| Chromoendoscopy | |||||||

| Methylene Blue (MB) | Inexpensive, widely studied for increased detection | May cause DNA mutations, must be sprayed on entire area to be visualized | 97% | 42% | Canto et al, 2001 (5) | 47 (551) | Multicenter parallel trial comparing random biopsies to MB-directed biopsies in patients with Barrett's esophagus |

| Indigo Carmine | Inexpensive, staining patterns well-characterized | Must be sprayed on entire area to be visualized | 93% | Not reported | Kara et al, 2005 (9) | 28 (not reported) | Single-center prospective randomized crossover trial comparing indigo carmine to NBI in patients with Barrett's esophagus |

| Narrow Band Imaging (NBI) | Highlights changes in vasculature, no dyes required | Low specificity for detection of Barrett's | 96% | 94% | Mannath et al, 2010 (12) | 446 [8 separate studies] (2,194) | Meta-analysis of eight studies studying NBI in patients with diagnosed Barrett's esophagus |

| Digital Contrast Mucosal Enhancement (DCME) | Highlights changes in vasculature, no dyes required | Not well studied | 92% | Not reported | Pohl et al, 2007 (13) | 57 (not reported) | Single-center blinded crossover trial comparing DCME to chromoendoscopy with acetic acid in patients with Barrett's esophagus |

| Autofluorescence Imaging (AFI) | Highlights changes in endogenous fluorophores | High false positive rate | 91% | 43% | Kara et al, 2005 (15) | 61 (116) | Single-center prospective trial comparing autofluorescence to random biopsies in patients with Barrett's esophagus |

| High-resolution Modalities | |||||||

| Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) | Can resolve individual tissue layers | Difficult to interpret images | 68% | 82% | Isenberg et al, 2005 (18) | 33 (314) | Single-center prospective study of patients undergoing surveillance for known Barrett's esophagus |

| Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy (CLE) | |||||||

| Probe-based (pCLE) | Ability to stitch together images | Imaging depth limited to 60 |im | 80% | 94% | Pohl et al, 2008 (23) | 38 (296) | Multicenter prospective study on patients with either known Barrett's esophagus, with a referral for previously diagnosed neoplasia, or screening |

| Endoscope-based (eCLE) | Ability to see below superficial mucosa, up to 250 μm | Slow frame rate | 93% | 98% | Kiesslich et al, 2006 (24) | 63 (433) | Single-center prospective trial on patients with either known Barrett's esophagus or with a referral for endoscopic treatment for previously diagnosed neoplasia |

Chromoendoscopy

Chromoendoscopy is a broad term that refers to the use of conventional white-light endoscopy combined with the addition of an exogenous dye that enhances contrast between normal epithelial tissue vs. dysplastic and cancerous tissue. Figure 2 shows an example of endoscopic imaging with an exogenous dye. These dyes fall primarily into three categories: absorptive stains, which are absorbed across the epithelial cell membrane; contrast stains, which highlight surface topography by filling the space between gaps in the mucosa; and reactive stains, which change color after undergoing chemical reactions by epithelial cells. None of these stains are currently approved by the FDA for chromoendoscopy, but the agents are routinely diluted for clinical use (4).

Figure 2.

Example of (A) conventional endoscopic view compared to view after (B) administration of Lugol's iodine. Figure from Curvers WL, Kiesslich R, Bergman JJGHM. Novel imaging modalities in the detection of oesophageal neoplasia. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology. 2008;22(4):687-720.

Briefly, the absorptive stains used for the detection of Barrett's-associated adenocarcinoma include methylene blue, toluidine blue, and crystal violet. Methylene blue (MB), or methylthioninium chloride, is a stain that colors intestinal metaplasia and absorptive cells of the small bowel and large bowel a blue color, while dysplasia and cancer cells do not stain as strongly if at all. It is primarily used for Barrett's esophagus, esophageal and gastric cancer, and ulcerative colitis, and has been shown to have a sensitivity of 97 percent and specificity of 42 percent for the detection of Barrett's-associated adenocarcinoma (5). There is some concern, however, that the use of MB may expose patients to increased cancer risk, as the dye has been shown to induce DNA damage when exposed to white light during endoscopy (6). While the finding that MB increases the detection of Barrett's-associated neoplasia is robust, future research remains to be done to further examine the potential problem of long-term increased cancer risk.

Crystal violet, also known as methylrosaniline chloride or gentian violet, is more commonly known as a topical antimicrobial agent, but is also a nuclear stain that is absorbed into intestinal cells that is used for the detection of Barrett's esophagus, with a sensitivity of 89 percent, and a specificity of 86 percent for this purpose (7). Similar to MB, however, there is some concern about the potential carcinogenicity of crystal violet in endoscopic use (8). Further research also remains to be carried out to investigate this effect.

Finally, indigo carmine, or indigotindisulfonate sodium, is a contrast stain, and is commonly used to image colon cancer, though it has also been reported for screening for Barrett's-associated neoplasia, with a sensitivity of 93 percent (9). Of note, magnification endoscopy, or zoom endoscopy, has been studied in conjunction with chromoendoscopy. Combining features of both a widefield and high-resolution modality, due to the ability to zoom in with the endoscope, the device has been shown to have high diagnostic accuracy, with a sensitivity of 83 percent and a specificity of 88 percent for the detection of high-grade dysplasia in a prospective multicenter trial in patients with known or suspected Barrett's esophagus, using indigo carmine. However, the diagnostic accuracy was found to be comparable to random biopsies; the only advantage was that magnification endoscopy resulted in less procedure time than random biopsies (10) (See Table 1).

Narrow-Band Imaging

Narrow-band imaging (NBI) is a novel technique that enhances superficial mucosal and vascular changes without the use of dyes or stains. NBI is based on the concept that the penetration depth of light is strongly affected by the presence of hemoglobin, with blue light only penetrating the superficial mucosa due to hemoglobin absorption, whereas red light penetrates deeper tissue layers due to lower absorption by hemoglobin. The currently available NBI system uses a red-green-blue sequential illumination system with a specialized filter placed on the light path. The latter selectively increases the contribution of blue light in a lower wavelength range (415-540 nm), which enhances visualization of the superficial epithelium and vascular network (11). A computer attached to the scope then takes these three separate images and combines them into one, giving the endoscopist a final contrast-enhanced NBI image highlighting the underlying vasculature, as shown in Figure 3. NBI has been shown to have high sensitivity and specificity for visualizing Barrett's-associated neoplasia, with a recent meta-analysis showing a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 96 percent and 94 percent, respectively, for the detection of high-grade dysplasia in the setting of Barrett's esophagus (12).

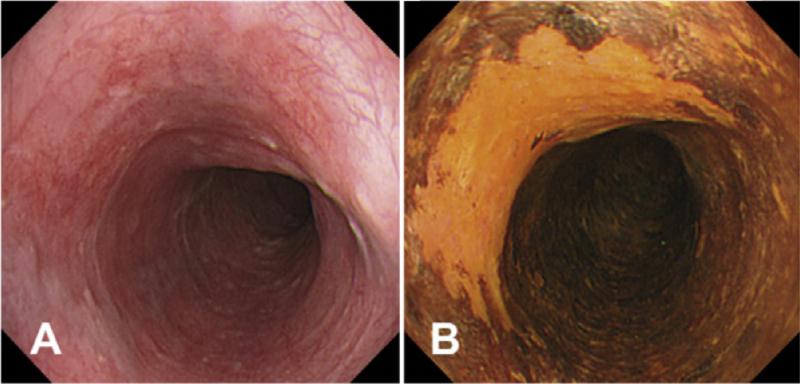

Figure 3.

Barrett's esophagus as shown with conventional white light endoscopy (Left) with corresponding image obtained with narrow band imaging (Right).

Digital Contrast Mucosal Enhancement

Digital contrast mucosal enhancement technologies do not alter the interaction of light with tissue but, rather, manipulate the red, green, and blue components of white light in the processor to create a “virtual” image that enhances superficial mucosal and vascular changes. The Fujinon Intelligent Chromoendoscopy (FICE) (Fujinon, Tokyo, Japan) and i-SCAN (Pentax, Tokyo, Japan) systems have been called “virtual chromoendoscopy,” as they achieve the same results as conventional chromoendoscopy, but doing so digitally and without any added dyes. In addition, these systems allow the endoscopist to switch between various preset modes that highlight different characteristics in the tissue, as shown in Figure 4.

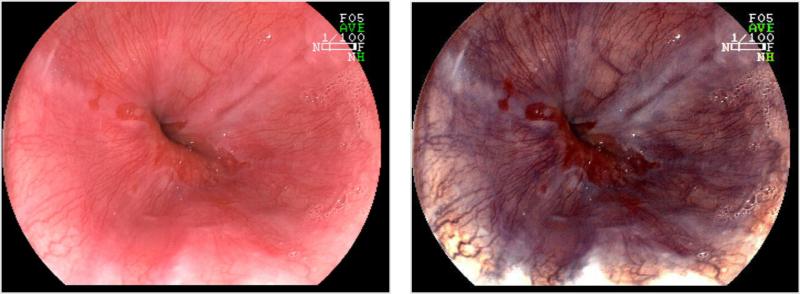

Figure 4.

Esophagitis as shown with conventional white light endoscopy (Left) with corresponding image obtained with FICE imaging (Right) Reference: Photograph and comment provided by: Prof. Kouzu, Division of Endoscopic Diagnostics and Therapeutics, Chiba University Hospital.

Digital contrast mucosal enhancement has so far been shown to be equivalent to conventional chromoendoscopy in a preliminary study comparing FICE to acetic acid chromoendoscopy, as its sensitivity in the detection of neoplasia in patients with Barrett's esophagus was 92 percent in a preliminary single center study with 61 patients (13). While this technology has not been found to be superior to conventional chromoendoscopy in terms of diagnostic accuracy, digital contrast mucosal enhancement may offer endoscopists a more efficient form of imaging, obviating the need for introducing exogenous dyes.

Autofluorescence Imaging

Autofluorescence imaging (AFI) has developed from the understanding that dysplastic and cancerous tissue have altered levels of fluorescent biomolecules such as elastin, collagen, and NADH, allowing visualization of these differences with a specific wavelength of violet light, namely 400-475 nm (14). Figure 5 shows an example of images obtained with AFI. While the use of AFI has been reported in many different organ systems, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the detection of Barrett's associated neoplasia were 91 percent and 43 percent, based on a per lesion analysis, in a single center prospective study of 99 patients with Barrett's esophagus (15). As noted in this study, this technology is very sensitive for the detection of Barrett's associated neoplasia, but lacks specificity, and would benefit from a complementary high-resolution imaging modality to increase the specificity of screening. Curvers et al showed in a large, multi-center study examining the use of tri-modal imaging, or white light endoscopy combined with NBI and AFI, that it is possible to increase the accuracy of AFI by adding NBI to AFI-abnormal areas, thereby reducing the false positive rate from 81 percent to 26 percent (16). Future studies are needed to investigate this concept of multimodal imaging to maximize sensitivity and specificity in endoscopic surveillance.

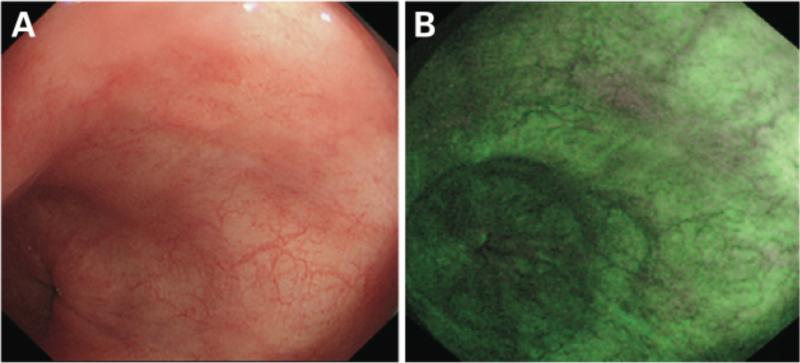

Figure 5.

A focus of adenocarcinoma as seen by (A) conventional white light endoscopy, and (B) autofluorescence imaging. Histology from this area confirmed the presence of adenocarcinoma. Figure from: Curvers WL, Singh R, Wong-Kee Song, et al. Endoscopic tri-modal imaging for detection of early neoplasia in Barrett's oesophagus: a multi-centre feasibility study using high-resolution endoscopy, autofluorescence imaging and narrow band imaging incorporated in one endoscopy system. Gut. 2008;57:167-172.

High-Resolution Imaging Modalities

The high-resolution imaging modalities discussed in this review are the new generation of imaging devices that allow the clinician to obtain images with sub-cellular resolution, often referred to as “optical biopsies.” Various advantages of these high-resolution imaging devices have been suggested in the diagnosis and management of Barrett's esophagus, including improved targeting of biopsies with the goal of increasing diagnostic yield, and the ability to immediately to perform a therapeutic intervention based on an ‘optical’ diagnosis. A discussion of the main imaging modalities currently being used by researchers follows below.

Optical Coherence Tomography

First developed for use in ophthalmologic imaging to noninvasively image the inside of the globe, the use of optical coherence tomography (OCT) has since spread to various specialties. In principle, OCT is similar to ultrasound – but using light instead, and works by using near-infrared light to produce cross-sectional images of tissue, penetrating up to 2 mm of depth. The benefit of this technology is that it may be used to image the microarchitecture of mucosal tissue, showing the epithelium, basement membrane, underlying vessels, and lamina propria, as shown in Figure 6. While OCT is similar to ultrasound, ultrasound imaging requires contact with tissue and allows resolution of roughly 100 micrometers; OCT does not require tissue contact and provides much higher resolution images, at 2-4 micrometers of spatial resolution, higher than conventional EUS systems (17) but less than current confocal platforms. The primary advantage of OCT is its imaging depth, and the ability to view the tissue in a transverse fashion, similar to how histologic slides are viewed. The sensitivity and specificity for the detection of Barrett's-associated neoplasia with OCT are 68 percent and 82 percent, respectively (18). While OCT has the potential to be a very useful imaging modality in endoscopic screening, particularly in its ability to detect subepithelial neoplasia, there are currently no commercially-available platforms, as currently existing systems are being evaluated in a research setting.

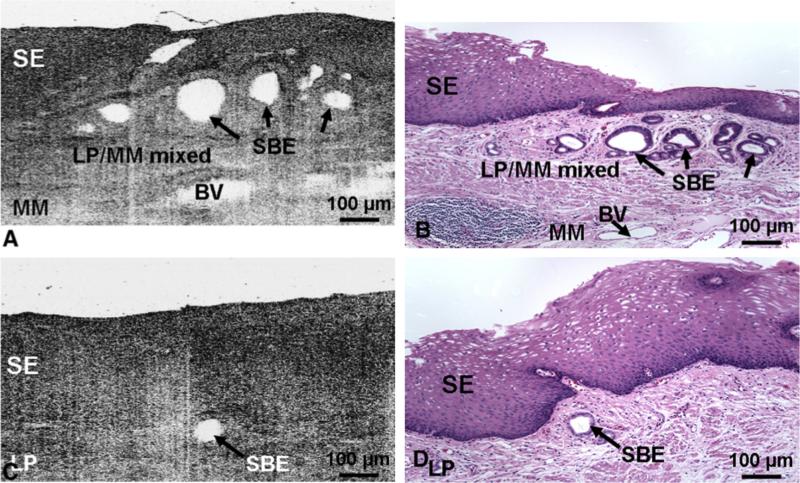

Figure 6.

(A, C) Representative optical coherence tomography (OCT) images, and (B, D) the corresponding histology micrographs of subsquamous Barrett's epithelium. (A, B) OCT image and corresponding histology (hematoxylin and eosin; × 100) of esophageal tissue in which there were multiple subsquamous Barrett's epithelial (SBE) glands beneath normal-looking squamous epithelium (SE). The region surrounding the SBE is a mixture of lamina propria (LP) and muscularis mucosae (MM). Blood vessels are present in the MM. (C, D) OCT image and corresponding histology (hematoxylin and eosin; × 100) of esophageal tissue in which an SBE gland is beneath normal-looking squamous epithelium. The physical size of the OCT image and histology micrograph is 1 mm × 0.57 mm (transverse × depth in tissue). Figure from: Cobb MJ, Hwang JH, Upton MP, et al. Imaging of subsquamous Barrett's epithelium with ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography: a histologic correlation study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:223-30.

Confocal Endomicroscopy

Confocal endomicroscopy uses exogenous contrast agents and low-powered laser light to allow epithelial imaging at a subcellular resolution. Figure 7 shows an example of images obtained with this imaging modality. This technology, like other imaging modalities discussed in this review, has spread to various clinical areas and specialties. There are two currently available confocal platforms available for clinical use, with slight differences between the two systems. The Pentax EC3870 (Pentax, Tokyo, Japan) combines a conventional endoscope with a confocal microscope on the tip, and is referred to as endoscope-based confocal laser endomicroscopy (eCLE). This system has the advantage of being able to image up to 250 micrometers below the surface, allowing the endoscopist to move through various depths of tissue seven micrometers at a time, obtaining thin-layered images analogous to histologic sections of tissue. Of note, the mucosa is visualized in an en face orientation parallel to the tissue surface with the confocal probe, in contrast to traditional histologic sections, which are cut in a transverse fashion. The spatial resolution of the system is roughly 0.7 μm, the highest resolution of any optical modality to date. Because the confocal probe is incorporated into the endoscope, the endoscopist is limited to using this endoscope and cannot combine eCLE with other widefield modalities such as NBI. In addition, eCLE has a slow frame rate of 1.2 frames/sec, meaning that images are viewed as a series of still images, similar to a radar screen.

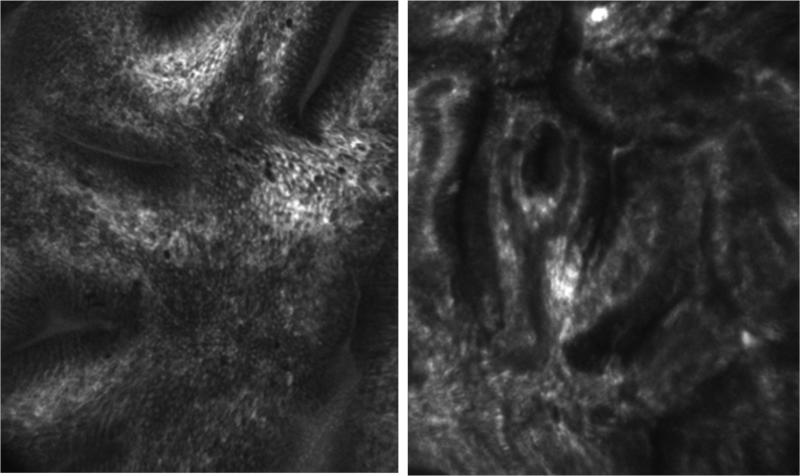

Figure 7.

Endoscopy-based confocal laser endomicroscopic (eCLE) image of Barrett's esophagus (Left) and Barrett's-associated high-grade dysplasia (Right).

The second commercially available confocal platform is the Cellvizio-GI (Mauna Kea Technologies, Paris, France), which is a probe-based system (pCLE). This device is passed through the accessory channel of any endoscope, rather than being integrated into the endoscope itself. The processor allows the endoscopist to stitch images together for review after imaging, creating a “mosaic” of images and larger field of view. Because the pCLE is not capable of sectioning into the tissue, the imaging depth is fixed at roughly 60 μm into the surface. The spatial resolution is ranges from 1-3.5 μm. The frame rate in the pCLE system is also faster than in the eCLE platform, displaying frame rates of 12 frames/sec and 1.2 frames/sec, respectively. While the pCLE platform is less expensive than eCLE, both cost more than $125,000, potentially limiting their use to tertiary referral centers.

In order to visualize cellular architecture, confocal microscopy requires exogenous fluorescent contrast agents. The agents that have primarily been used to image with confocal microscopy are intravenous fluorescein and topical acriflavine. Fluorescein, an FDA-approved intravenous contrast agent used commonly in ophthalmology, must be given intravenously. The advantage of the intravenous administration, however, is deeper visualization into the tissue, allowing the endoscopist to clearly delineate the lamina propria. Acriflavine was historically used as an antibacterial agent. Although it localizes to the cell nuclei, concerns have been raised about the potential mutagenicity of the drug. Despite this, its use in confocal microscopy as topically applied contrast agent has not been associated with any adverse events (19-21). Acriflavine is not currently FDA-approved, which means its use must be monitored closely under an IND.

Because high-resolution modalities such as confocal endomicroscopy create images such as those typically examined by pathologists, researchers have questioned whether endoscopists are as accurate at interpreting these so called “optical biopsies.” So far, kappa statistics for endomicroscopists (0.68) and pathologists (0.56) trained in the interpretation of these images show that both groups are comparable in interpreting normal and abnormal images of the esophagus, stomach, small bowel, and colon (22). The negative predictive value of confocal endomicroscopy is high, with sensitivity and specificity for the detection of Barrett's-associated neoplasia with pCLE at 80 percent and 94 percent, respectively (23), and 93 and 98 percent with eCLE (24). The use of this technology has also been shown to reduce the number of biopsies needed for diagnosing neoplasia in Barrett's esophagus by as much as 60 percent (25).

High-Resolution Microendoscopy (HRME)

The high-resolution microendoscope (HRME) is a novel fiber-optic bundle that can image mucosa at a subcellular resolution by fluorescence imaging (26). In contrast to laser-based confocal microscopy, which generates scanning images, HRME instead uses LED illumination allowing a real-time view, as shown in Figure 8. While the device does not have the imaging depth or resolution of current confocal platforms, the cost is significantly lower, at approximately $4000 per system, but is currently only available in a research setting. To use the device, the one mm diameter fiber-optic probe is inserted into the accessory channel of a standard endoscope (similar to an endocytoscope or pCLE), allowing the endoscopist to obtain both a wide-field image along with a microscopic view from the HRME. The device requires exogoneous fluorescent contrast agents with current studies using topical proflavine hemisulfate 0.01% (26-28).

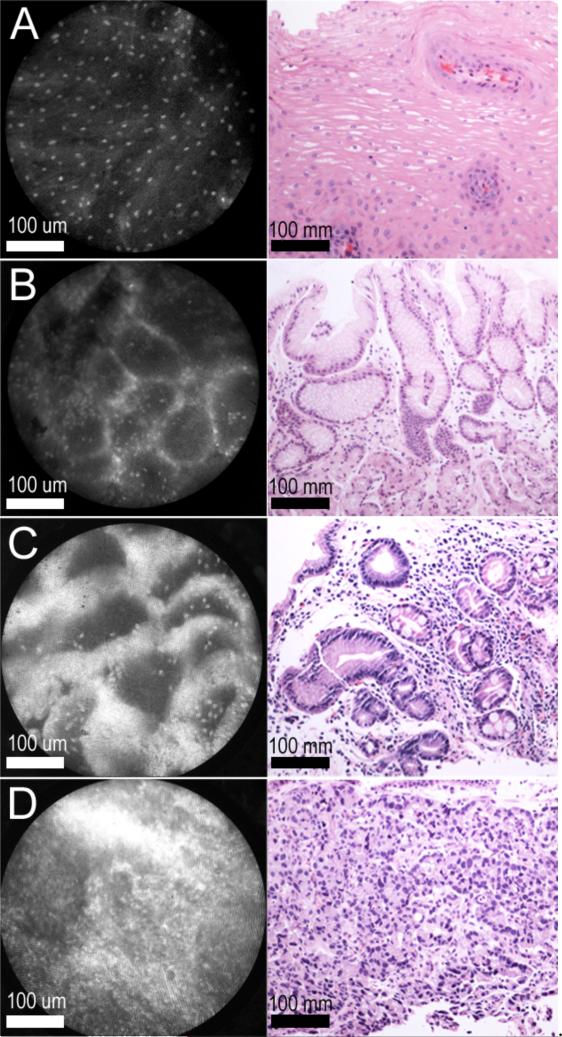

Figure 8.

High-resolution microendoscopic images of benign squamous mucosa, gastric mucosa, Barrett's esophagus, and adenocarcinoma (Left) with corresponding H+E histopathologic images (Right). (A) Benign squamous mucosa. (B) Benign gastric mucosa. (C) Barrett's esophagus. (D) Esophageal adenocarcinoma

So far, HRME has been shown to have good sensitivity and specificity as compared to standard histopathology in patients with Barrett's esophagus, as expert review of the images after collection was found to have a sensitivity of 87 percent and specificity of 61 percent (28). Currently, a preliminary single center study recently completed examining the use of HRME in Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma, found that raters were able to diagnose images after collection with high accuracy and interrater reliability (presented at Digestive Diseases Week 2011).

CONCLUSIONS

Multiple novel optical imaging modalities are now available to clinicians to visualize esophageal mucosa at the macro and cellular level in real-time, and the use of these devices will likely increase their diagnostic accuracy in the detection of neoplasia. The potential benefits are numerous, as these technologies may give clinicians the ability to not only target biopsies more accurately and thus reduce the number of biopsies needed for diagnosis, but make decisions based on these real-time imaging modalities, saving patients additional visits for follow-up treatment. The small size and low cost of certain imaging modalities discussed previously, such as the high-resolution microendoscope (HRME), also allow for relatively quick screening of large numbers of patients in low-resource settings. Before these devices are used routinely, however, further research is required in the form of large randomized, controlled trials to determine the optimal combination of imaging modalities that provide the greatest diagnostic accuracy for the detection of esophageal neoplasia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization . World Health Statistics. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society Esophageal Cancer. 2007.

- 3.Van der Veen AH, Dees J, Blankensteijn JD, Van Blankenstein M. Adenocarcinoma in Barrett's oesophagus: an overrated risk. Gut. 1989;30(1):14–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ASGE Technology Committee Chromoendoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(4):639–49. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canto MI, Setrakian S, Willis JE, Chak A, Petras RE, Sivak MV. Methylene blue staining of dysplastic and nondysplastic Barrett's esophagus: an in vivo and ex vivo study. Endoscopy. 2001;33(5):391–400. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-14427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olliver JR, Wild CP, Sahay P, Dexter S, Hardie LJ. Chromoendoscopy with methylene blue and associated DNA damage in Barrett's oesophagus. Lancet. 2003;362(9381):373–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amano Y, Kushiyama Y, Ishihara S, Yuki T, Miyaoka Y, Yoshino N, et al. Crystal violet chromoendoscopy with mucosal pit pattern diagnosis is useful for surveillance of short-segment Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(1):21–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aidoo A, Gao N, Neft RE, Schol HM, Hass BS, Minor TY, et al. Evaluation of the genotoxicity of gentian violet in bacterial and mammalian cell systems. Teratogenesis Carcinog Mutagen. 1990;10(6):449–62. doi: 10.1002/tcm.1770100604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kara MA, Peters FP, Rosmolen WD, Krishnadath KK, ten Kate FJ, Fockens P, et al. High-resolution endoscopy plus chromoendoscopy or narrow-band imaging in Barrett's esophagus: a prospective randomized crossover study. Endoscopy. 2005;37(10):929–36. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma P, Marcon N, Wani S, Bansal A, Mathur S, Sampliner R, et al. Non-biopsy detection of intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in Barrett's esophagus: a prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2006;38(12):1206–12. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gono K, Obi T, Yamaguchi M, Ohyama N, Machida H, Sano Y, et al. Appearance of enhanced tissue features in narrow-band endoscopic imaging. J Biomed Opt. 2004;9(3):568–77. doi: 10.1117/1.1695563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mannath J, Subramanian V, Hawkey CJ, Ragunath K. Narrow band imaging for characterization of high grade dysplasia and specialized intestinal metaplasia in Barrett's esophagus: a meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2010;42(5):351–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pohl J, May A, Robenstein T, Pech O, Nguyen-Tat M, Fissler-Eckhoff A, et al. Comparison of computed virtual chromoendoscopy and conventional chromoendoscopy with acetic acid for detection of neoplasia in Barrett's esophagus. Endoscopy. 2007;39(7):594–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillenwater A, Jacob R, Richards-Kortum R. Fluorescence spectroscopy: a technique with potential to improve the early detection of aerodigestive tract neoplasia. Head Neck. 1998;20:556–62. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199809)20:6<556::aid-hed11>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kara MA, Peters FP, Ten Kate FJW, Van Deventer SJ, Fockens P, Bergman JJGHM. Endoscopic video autofluorescence imaging may improve the detection of early neoplasia in patients with Barrett's esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(6):679–85. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02577-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curvers WL, Singh R, Song L, Wolfsen HC, Ragunath K, Wang K, et al. Endoscopic tri-modal imaging for detection of early neoplasia in Barrett's oesophagus: a multi-centre feasibility study using high-resolution endoscopy, autofluorescence imaging and narrow band imaging incorporated in one endoscopy system. Gut. 2008;57(2):167–72. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.134213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tadrous PJ. Methods for imaging the structure and function of living tissues and cells: I. Optical coherence tomography. J Pathol. 2000;191(2):115–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200006)191:2<115::AID-PATH589>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isenberg G, Sivak MV, Chak A, Wong RCK, Willis JE, Wolf B, et al. Accuracy of endoscopic optical coherence tomography in the detection of dysplasia in Barrett's esophagus: a prospective, double-blinded study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(6):825–31. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiesslich R, Burg J, Vieth M, Gnaendiger J, Enders M, Delaney P, et al. Confocal laser endoscopy for diagnosing intraepithelial neoplasias and colorectal cancer in vivo. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(3):706–13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin D, Pierce MC, Gillenwater AM, Williams MD, Richards-Kortum RR. A Fiber-Optic Fluorescence Microscope Using a Consumer-Grade Digital Camera for In Vivo Cellular Imaging. PLoS One. 5(6):7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polglase AL, McLaren WJ, Skinner SA, Kiesslich R, Neurath MF, Delaney PM. A fluorescence confocal endomicroscope for in vivo microscopy of the upper- and the lower-GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(5):686–95. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunbar KB, Kiesslich R, Deinert K, Goetz M, Maitra A, Montgomery EA, et al. Confocal laser endomicroscopy image interpretation: Interobserver agreement among gastroenterologists and pathologists. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(5):AB348–AB. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pohl H, Rösch T, Vieth M, Koch M, Becker V, Anders M, et al. Miniprobe confocal laser microscopy for the detection of invisible neoplasia in patients with Barrett's oesophagus. Gut. 2008;57(12):1648–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.157461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiesslich R, Gossner L, Goetz M, Dahlmann A, Vieth M, Stolte M, et al. In vivo histology of Barrett's esophagus and associated neoplasia by confocal laser endomicroscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(8):979–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunbar KB, Okolo P, Montgomery E, Canto MI. Confocal laser endomicroscopy in Barrett's esophagus and endoscopically inapparent Barrett's neoplasia: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled, crossover trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70(4):645–54. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muldoon T, Anandasabapathy S, Maru D, Richards-Kortum R. High-resolution imaging in Barrett's esophagus: a novel, low-cost endoscopic microscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68(4):737–44. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muldoon TJ, Pierce MC, Nida DL, Williams MD, Gillenwater A, Richards-Kortum R. Subcellular-resolution molecular imaging within living tissue by fiber microendoscopy. Opt Express. 2007;15(25):16413–23. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.016413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muldoon TJ, Thekkek N, Roblyer D, Maru D, Harpaz N, Potack J, et al. Evaluation of quantitative image analysis criteria for the high-resolution microendoscopic detection of neoplasia in Barrett's esophagus. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15(2):7. doi: 10.1117/1.3406386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]