Abstract

To understand the underlying psychosocial reactions against the unfolding of medical events that announce the disease progression, the objective of this analysis was to identify the patterns of online discussion group message themes in relation to the medical timeline of one woman's breast cancer trajectory. 202 messages posted by Darlene (our studied case) were analyzed by 2 independent coders using a grounded theory approach. The findings suggest that the pattern of messages was clearly correlated with distress-inducing events. The most frequent interaction theme was about building friendship with peers through communication of encouragement, validation, appreciation, and life sharing. Narratives of medical progression were constantly updated to identify similarities with peers. Family issues were increasingly raised at the end of life.

Introduction

Breast cancer is an uninvited and life-altering event frequently associated with a rapid entry into a challenging treatment regimen and a long process of learning to cope with significant physical, practical, and emotional challenges (Boehmke & Dickerson, 2006). Breast cancer can engender negative emotional and interpersonal responses throughout the continuum of cancer care (including the phases of diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, and end of life) (Ganz et al., 1996). Support groups have become central to psychosocial interventions for cancer patients because they provide a confidential atmosphere where cancer patients can discuss their challenges and insights with each other. Compared to control groups, patients who participate in support groups have fewer self-reported physical symptoms, lower cortisol levels, better immune system function and quality of life, and longer survival time (Spiegel, Bloom, & Yalom, 1981; Spiegel, Kraemer, Bloom, & Gottheil, 1989; McLean, 1995; Classen, et al., 2001; Gray, Fitch, Davis, & Phillips, 1997; Spiegel, 1997; Van der Pompe, Duivenvoorden, Antoni, Visser, & Heijnen, 1997; Spiegel & Sephton, 2001; Classen et al., 2001; Winzelberg et al., 2003).

However, face-to-face groups, as noted above, have improved well-being, but often pose barriers to people with limited mobility or who live a distance from where they are held. A growing number of patients use online support groups, which are available anytime in the privacy of one's home (Fogel, Albert, Schanbel, Ditkoff, & Neuget, 2002; Meric et al., 2002; Eysenbach, 2003). Whether through discussion boards, chat rooms, or newer social networks, online support groups create a safe, virtual space to give and receive support. Their greater anonymity may provide a more comfortable venue to disclose and discuss sensitive personal health issues than face-to-face settings (Campbell et al., 2001). In this way, they integrate expressive writing tasks where participants write about the distress-inducing event of cancer, while sharing thoughts and feelings that may be too difficult to share with loved ones (Sharf, 1997). Moreover, by removing the visual cues of age, gender, race, or social status, online support groups have been found to equalize participants' status across these commonly divisive factors (Madara & White, 1997). Online cancer support groups have been shown to increase participants' sense of social support, personal empowerment, and self-esteem; and reduce depression, cancer-related trauma, and social isolation (Fogel, Albert, Schabel, Ditkoff, & Neugut, 2002; Winzelberg et al., 2003; Lieberman et al., 2003; Im, Chee, Tsai, Lin, & Cheng, 2005; Rodgers & Chen, 2005).

Understanding how cancer patients use online support groups is an important factor in determining the value of Internet-based services to support cancer patients. Research that characterizes communication patterns can enhance our understanding of the mechanisms that facilitate positive coping with cancer diagnosis, treatment, survival, or death. A growing body of research on online support group messages suggests that qualitative analysis is a valuable method for categorizing patient cancer-related experiences and concerns, identifying existing gaps in knowledge, and guiding priorities for future research (Eysenbach & Till, 2001). For instance, Weinberg et al. (1996) found the primary use of an online breast cancer group for members was to share their emotions about having cancer, provide supportive statements to each other, and discuss their medical situation. By examining interaction patterns on a breast cancer list, Sharf (1997) reported that three major themes of discussion were shared: information exchange, social support, and personal empowerment. Klemm et al. (1998) revealed that information exchange and personal opinions accounted for a major portion of the 300 messages retrieved from a colorectal cancer support group mailing list. The next most frequent categories were encouragement/support, personal experiences, thanks, humor, and prayer, respectively. In another study, Klemm et al. (1999) found comparable results in the content of breast cancer and prostate cancer patient online support groups, with the exception that women more often engaged in supportive messages while men more often engaged in information exchange. According to another content analysis study of 10 cancer e-mail lists, informational support was found as the most frequent communication style. Cancer survivors communicated support primarily through offers of technical advice about communicating with health care providers, their experiences with specific treatments, problem management strategies, and recurrence (Meier, Lyons, Frydman, Forlenza, & Rimer, 2007).

Most research to date in qualitative evaluation of online support groups has analyzed postings from a sample of users without relating their message content topics to their medical background or their disease trajectory. However, the illness experience and personal needs change as the patient progresses along the illness trajectory as each phase presents a new set of challenges and concomitant opportunities for personal growth and reflection (Luker, Beaver, Leinster, & Owens, 1996; van der Molen, 2000). Thus mapping how the themes change as the patient moves from diagnosis, through treatment, and towards recovery or death, may provide valuable insights to inform ways to tailor future psychosocial and educational interventions according to the cancer illness trajectory (Wen & Gustafson, 2004). Moreover, the use of the case study method and memoir has long been used to gain deep understanding of commonly occurring but little understood phenomena (Merriam, 1998). Therefore, the purpose of this analysis was to identify the patterns of online discussion group message themes in relation to the medical timeline of one woman's breast cancer journey from the time of her diagnosis to the time of her death. Using a case study approach for online narrative analysis is an innovative approach to investigate changing message themes across the cancer trajectory to understand the underlying psychosocial reactions and needs against the unfolding of medical events that announce the disease progression. We envision that the findings of this research will be used to guide future psychosocial interventions to prioritize and tailor information and support resources when needed most.

Method

Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (CHESS)

This paper reports how a woman confronting breast cancer used the discussion group service of the Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (CHESS) “Living With Breast Cancer” program. CHESS is developed at the University of Wisconsin - Madison and is a computer-based system that provides patients and their families with a wide range of services, including information, social support, decision support, and skills training (Gustafson et al., 1998; Gustafson et al., 1999; Gustafson et al., 2001; Gustafson et al., 2002; Gustafson et al., 2005). The messages used in this analysis were originally part of an earlier CHESS “Living With Breast Cancer” study that took place in 2001 through 2003. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Breast cancer patients were recruited from cancer centers in Madison, WI; Cleveland, OH; Detroit, MI; and Rochester, MN. Patients were eligible if they were within 61 days of their breast cancer diagnosis, not homeless, able to give informed consent, and understand and answer sample questions from the pretest. Doctors or nurses introduced the study to patients during clinic visits. If patients permitted, a research staff member contacted the patient, introducing that we were evaluating various methods of providing information and support to women with breast cancer. After the study was described, participants signed a letter of consent giving access to their medical records and allowing us to monitor and analyze their computer use (if so assigned), completed a brief pretest survey, and were randomly assigned to the Internet, CHESS, or control group. Random assignment was stratified by geographic site and ethnicity (minority or Caucasian), with each site provided two sets of randomly ordered sealed envelopes containing group assignments. Over 83% of those invited agreed to participate (ranging from 81 to 87% at various sites). Decliners did not differ in demographic characteristics from those who agreed. A total of 257 eligible patients were recruited. Random assignment led to 83 entering each of the Internet and control conditions and 91 to CHESS group.

CHESS Discussion Group Service

The CHESS discussion group, which enables peer-to-peer communication, allows patients to anonymously share information and support with each other. All users log on with a code name and password to protect their privacy. It is a text-based, asynchronous bulletin board that is accessible for 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and has consistently been the most frequently used service in the long line of CHESS studies (McTavish et al., 2003). Unlike the forms of listserves and chatrooms, bulletin boards have the benefit of having topics organized into readily accessible threads which can be posted by multiple people on the same topic (Hsiung, 2000). CHESS discussion groups are monitored by a trained study moderator to ensure that messages are supportive and do not contain any inappropriate information. Our CHESS discussion group moderators often have social work background and years of experience in monitoring online support groups. At the start of the CHESS study participation, participants were encouraged to write a message introducing themselves, as well as to fill out “About Me” (which included some basic information such as when they were diagnosed with breast cancer, the stage of their cancer and treatments they completed or were planning to undergo). Discussion group guidelines were verbally reviewed during the study orientation and posted on the site for future reference. During the course of study, the discussion group was monitored to make sure that hurtful or harmful information is not being promoted on the site. Those monitoring the discussion generally do not intervene in the discussion unless information is posted that may bring harm to others or themselves. There is an IRB approved adverse event intervention plan if this occurs.

Discussion Group Message Collection

Time-stamped posting transcripts of the selected user for this study were analyzed. All names (even study codenames) in this article were changed to protect the person's identity. “Darlene” is a pseudonym that was used in this article to refer to the selected user whose messages were studied. We filtered and grouped the transcripts by Darlene's medical timeline from her breast cancer diagnosis to death. Her medical timeline events were identified and extracted from her posted messages and her responses to study medical history assessment.

Darlene's was arbitrarily chosen as our case study because she was an active discussion group participant who regularly posted messages shortly after a breast cancer diagnosis until the time immediately before her death. Her unfortunate medical consequence combined with her rich online support group messages provided a unique opportunity to study her discussion group posts in relation to her medical timeline in the context of peer-supportive communication.

Thematic Analyses Process

The objective of this analysis was to identify components of Darlene's experience across her medical timeline as they occurred in her interaction with others on the CHESS discussion group. Therefore, qualitative content analysis was preferred to quantitative methods, as postings in a support group are a construct of social interaction, which is found to be best examined with qualitative research methods (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The underlying conceptual framework for our study guiding the analyses coding process is Lazarus and Folkman's model of coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The model conceptualizes adaptation to chronic illness as a function of the complex interplay of significant life events, disease/treatment factors, appraisal processes, external/internal personal resources, and coping behavior. We initially developed potential key words based on the Stress and Coping model. Then, we used a grounded theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) to identify and establish themes and theme definitions as we reviewed and analyzed the transcripts. During the first stage of open coding, two researchers independently reviewed the transcripts and assigned each message with key words. A complete sentence was required to be coded for a key word. Following the initial coding of the messages, researchers compared their coded key words of each message and discussed until the agreement was reached with regards to the essential meaning of the messages and the title of the coding. During this process, researchers iteratively refined the key word definitions or created new ones as new themes emerged. Researchers also related and grouped codes together into a loose framework of categories, a procedure known as axial coding of the grounded theory procedure. Next, using a selective coding procedure, higher-level themes were further established by relating the rests of the categories to themes. Therefore, all the themes were theory-driven and data-driven, and the coding scheme inherently described the content and patterns of the studied messages. Structured Microsoft Excel spreadsheets and Excel features were used to prepare, document, and compare coded key words and themes between two research coders (Meyer & Avery, 2009).

Messages varied in length and most of them contained multiple distinct discussion topics within one posting entry. For example, Darlene might comment on treatment in one sentence and offer emotional support to others in the next sentence in one posted message. Thus, we decided that one message could be coded to multiple themes depending on how many topics were addressed in any given posting. Because numbers of messages posted also varied every month, theme percentages over the total number of messages in each given month was calculated to present changing patterns across subthemes (see Figures 2–7 in the Results section). Theme percentage (%of messages that contain the theme) allows us to compare the proportion of posted themes over time regardless of various monthly message volumes.

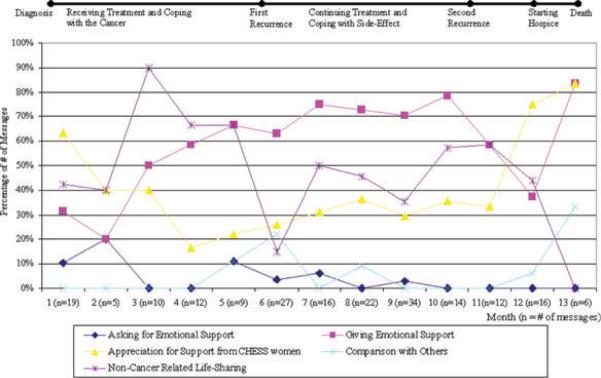

Figure 2.

Pattern of “bonding with other breast cancer women” message theme across the cancer trajectory

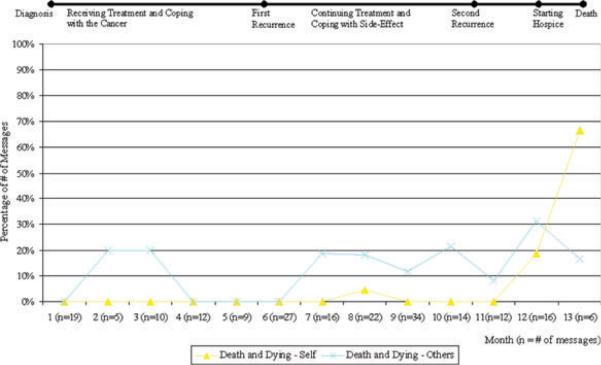

Figure 7.

Pattern of “death and dying” message theme across the cancer trajectory

Results

Darlene—A Case Study Overview

Darlene was 42 years old when she was diagnosed with stage III breast cancer. She was enrolled in the CHESS “Living With Breast Cancer” study 10 days after her initial diagnosis. She had a modified radical mastectomy 3 days postdiagnosis and underwent chemotherapy treatment. In the midst of her chemotherapy treatments, just over 5 months after her original diagnosis, Darlene had a recurrence of breast cancer. She tried numerous chemotherapy regimens and had radiation therapy over the next 8 months until her death.

Darlene posted a total of 202 CHESS discussion group messages over her 13-month journey. There were a total of 91 CHESS study participants in the study. Seventy-two percent of the sample (n = 66) wrote 3 or more messages while 28% wrote 3 or fewer messages. In terms of Darlene's social network in this group, Darlene posted messages to 38 different study participants.

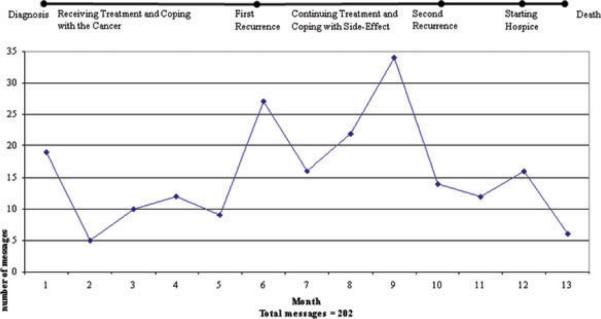

Change of Message Frequencies Across the Cancer Trajectory

Darlene started her discussion group posting with 19 messages during her first month. As a woman newly diagnosed with breast cancer, Darlene joined the CHESS discussion group hoping to find support. Her first message to the discussion group stated, “I am only within two weeks of diagnosis and subsequent mastectomy so this is all very new to me.” As illustrated in Figure 1, the number of her messages had a sharp increase during month 6, as the signs and diagnosis of a breast cancer recurrence occurred. She wrote, “I am feeling so afraid tonight though. I found a lump on my mastectomy incision line last night.” In the midst of facing side effects from her chemotherapy treatments, the deteriorating condition of another CHESS user who Darlene referred to as her twin (both women had similar treatments) became a focus of her conversation resulting in 34 messages during month 9. At the same time (month 9), her message topics also centered on the possibility of the second recurrence. She wrote “…probably mets… This, as you all know, is very bad news… I am really, really bummed.” Darlene was referred to hospice during month 12. During this very difficult time Darlene engaged in conversations about normal life events with discussion group members. She specifically asked how each person was doing, how their kids and other family members were; thanked all the women for their support and encouragement. Darlene also tried to reassure others and cautioned against comparing themselves to her. She wrote, “Remember my BC is quite marginal—my oncologist has said from the beginning that it is the most aggressive BC he has ever seen.”

Figure 1.

Number of monthly messages across the cancer trajectory

Themes, Subthemes Definitions and Their Overall Frequencies

We developed 19 subthemes categorized by six higher-level themes, including “Bonding with Other Breast Cancer Women,” “Emotional and Spiritual Expression,” “Cancer Treatment and Physical Updates,” “Cancer Information and Experience Exchange,” “Cancer Impact,” and “Death & Dying.” Table 1 lists and orders each of the 6 themes, 19 subtheme categories, its definition, and a subtheme example excerpted from the transcripts, from the most frequent theme to the least frequent one. “Bonding with Other Breast Cancer Women” is the most frequent higher-level theme that describes how Darlene built and strengthened her friendship with other CHESS women through communication of emotional empathy, supportive encouragement, solidarity, comparison and validation, appreciation, and general everyday life sharing. “Emotional and Spiritual Expression” involves expressing both positive and negative feelings and being self-revealing of emotional events. We also paid attention to any prayer, spiritual expression and service utilization Darlene conveyed through this context, including participation in church service. The frequencies of Darlene's self-reported cancer progression, symptoms, and physical mobility were tracked in the theme of “Cancer Treatment and Physical Updates.” The “Cancer Information and Experience Exchange” theme includes interaction and exchange of factual medical information as well as personal experience/advice regarding breast cancer, specific treatment, problems, processes, and procedures between Darlene and other CHESS women. The “Cancer Impact” theme documents other dimensions of Darlene's life being affected by her breast cancer diagnosis and progression elicited from her messages. We were also interested in concerns and possibilities of death being communicated across the cancer trajectory which will potentially inform future intervention facilitating end of life communication. The frequencies of Darlene messages associated with death including her own, other CHESS women, and families or friends were tracked.

Table 1.

Themes, Subtheme Definitions, Examples, and Total Frequencies Listed From the Most to the Least Frequent Over 13 Months

| Themes |

Total Theme Frequencies Over 13 Months | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-themes | Definition | Message Example | |

| Bonding With Other Breast Cancer Women | 301 | ||

| Giving Emotional Support | Giving others emotional support such as words of encouragement, hope, and optimism | “I am so happy for you. I hope the (radiation) burns continue to heal nicely.” | 123 |

| Noncancer Related Life-Sharing | Sharing her personal noncancer related life with other PHPN women | “I spent 2 hours ice skating today—I love being outside this time of year.” | 89 |

| Appreciation for Support from PHPN Women | Expressing appreciation for the support from PHPN women. | “Thank you all for your encouraging and supportive words.” | 78 |

| Comparison with Other PHPN Women | Reflecting and comparing with others in terms of cancer diagnosis, treatment and outcomes. | “I feel so sad for Stargazer and her friends/family and it is extremely difficult not to make comparisons—she and I had been seeing one another in the hospital almost each time we were there.” | 12 |

| Asking for Emotional Support | Asking others for emotional support such as words of encouragement, hope, and optimism. | “Any encouraging words for this very early survivor would be greatly appreciated.” | 7 |

| Emotional and Spiritual Expression | 195 | ||

| Emotional Expression | Expressing personal emotions such as happy, sad, fear, etc. | “The fear has been replaced by sadness, anger, frustration and probably a bit more fear.” | 140 |

| Spiritual Expression | Expressing spiritual beliefs and use of spiritual support/service. | “I am still praying for a miracle.” | 55 |

| Cancer Treatment and Physical Update | 181 | ||

| Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Update | Updating her cancer diagnosis, progression and treatment progress. | “I had my first A/C on 8/1.I will have a total of six A/C cycle, so have five to go.” | 103 |

| Side-effect and Functional Wellbeing Update | Updating her side-effect complication and functional wellbeing status. | “I was down for eight days with nausea and GI problems, including mouth sores and sore throat.” | 78 |

| Cancer Information and Experience Exchange | 88 | ||

| Giving Personal Cancer Advice/Experience | Giving others her personal advice and experience on treatments, side-effect and coping strategies. | “I, too, have had the worse pain after PT then before.” | 37 |

| Asking for Personal Cancer Advice/Experience | Asking others for their advice and experience on treatments, side-effect and coping strategies. | “I started dreading how often it (being mistaken for a man)will happen when I am bald. Have any of you had similar experience? How did you handle it?” | 28 |

| Giving Cancer Medical / Treatment Information | Giving others generic cancer information about diagnosis and treatment. | “Metastasis means spread of the cancer to a distant organ system.” | 14 |

| Asking for Cancer Medical / Treatment Information | Asking others for generic cancer information about diagnosis and treatment. | “He mentioned Zeloda—does anyone know anything about that?” | 9 |

| Cancer Impact | 87 | ||

| Relationship Affected by Cancer | Concerning the cancer effect on her relationship with her significant others | “Me and my support systems are so tired of bad news! I really do not know how much more my parents can take.” | 39 |

| Other Aspects of Life Affected by Cancer | Concerning the cancer effect on other aspects of her life | “I am still on disability, earning only 60% of usual salary” | 27 |

| Appearance and Sign of Illness | Expressing appearance change and concern due to the illness. | “Having my head shaved has been interesting…no one has called me sir yet.” | 21 |

| Death and Dying | 32 | ||

| Death and Dying - Others | Discussing death and dying issue about others | “Being with her at the time of her death was a gift-the meaning of which I may never understand.” | 24 |

| Death and Dying - Self | Discussing death and dying issue about herself | “There are also lots of folks stopping over, wanting to do their own-kind of, dying work—it is very strange and hard to explain, but lots of work for me.” | 8 |

Change of Theme Frequency Patterns Across the Cancer Trajectory

Bonding With Other Breast Cancer Women Theme

Giving Emotional Support

Darlene posted 123 messages under the subtheme “Giving Emotional Support,” the second greatest subtheme over the 13-month period. We categorized “Giving Emotional Support” statements as those in which Darlene gave other CHESS women her support, encouragement, wishes, and empathy such as “…best of luck and I hope it turns out to be negative.” As Darlene initially posted “I look forward to the time I can provide some support back to you all” after receiving many supportive messages regarding the treatment side effects she was experiencing. This type of supportive language became a constant theme in the messages that she wrote to others, usually equaling more than 50% of her monthly messages after 2 months of participation in CHESS. This supportive language dropped dramatically between the time of her second recurrence and the start of her hospice care. However, in her last month when her death was inevitable she once again posted messages to encourage other women resulting in an increase in the subtheme “Giving Emotional Support.”

Noncancer Related Life Sharing

Darlene also shared other aspects of her life not specifically relevant to her cancer. The frequencies of her posts around “Noncancer Related Life-Sharing” subtheme were higher when she had a regular treatment routine. For instance, she described her pet as “my poodle is a clownish, lovable, affectionate, one year old lover.” She also shared with the group that “She (my mother) is who taught me to make pie crusts and boy was that peach pie ever good.” A sharp decrease in “Noncancer Related Life-Sharing” subtheme was observed during the time of Darlene's first recurrence and end-of-life when the main focus of conversation was her illness.

Appreciation for Support From CHESS Women

Darlene frequently acknowledged that the information and support she received from other CHESS women was a source of strength and courage helping her to cope. Darlene expressed her gratefulness to be a part of CHESS while coping with the chemotherapy: “Getting through these early weeks would be exceedingly difficult without this support—thank you all for your kindness.” In the midst of coping with the uncertainty of her first recurrence, she wrote “Thank you all so much for the outpouring of support and good wishes. It helped so much in the past 36 hours.” She continually expressed appreciation for being part of a supportive community especially during the last 2 months of her life. In her very last good-bye message, she wrote “You have all been wonderful over the past 12 months. Carry on. Love, Darlene.”

Comparison With Other CHESS Women

Darlene tended to mirror her prognosis with other CHESS women who had similar diagnoses and treatments. This was especially around the time of her first recurrence. For example, Darlene paid very close attention to Mary who was receiving the same chemotherapy treatments. As Mary's condition deteriorated, Darlene wrote “she and I had been on the same chemotx drugs and we had both failed most of them.” Darlene also tried to connect with others with advanced breast cancer, she posted “It was helpful to me to find another person on CHESS who has mets/recurrence, so I wanted to send you a post and invite dialogue.” While early on Darlene compared her experience to that of similar others, near the end Darlene asked others not to compare themselves with her. She wrote “I am sorry that you all are comparing your situation to me—I am so far outside the line that there really is no comparison, so throw me out.”

Asking for Emotional Support

In the very first of Darlene's messages, she asked for others' support as “Any encouraging words for this very early survivor would be greatly appreciated.” However, over time, it was rare that Darlene would explicitly request support from others in her messages. The only occasions when she asked for support (other than when she first logged on) were when she faced the first recurrence and was having a difficult time with her treatment. Before her first recurrence was confirmed, she wrote to others “I am feeling so afraid tonight though…Please, any positive thoughts or support …I should know more about this thing tomorrow.”

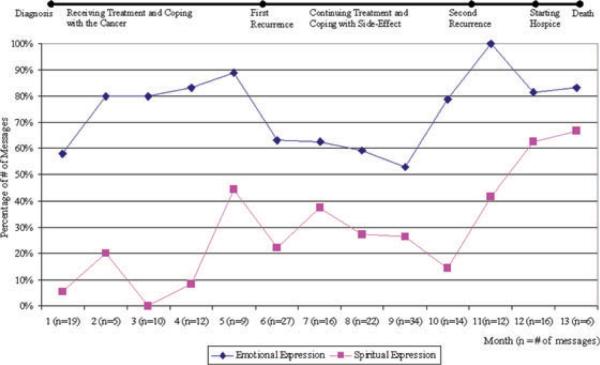

Emotional and Spiritual Expression Theme

Emotional Expression

Darlene heavily used the CHESS discussion group to express her emotions. This “Emotion Expression” subtheme had the greatest frequencies and was the highest monthly percentage subtheme in 7 out of 13 months in the analysis. Darlene's emotional expression was generally associated with up and down times in her life affected by cancer. The day after her first chemo, she wrote “Yesterday was gift though, because I felt great and forget I had cancer for a few hours!” Darlene's used the discussion group to share her emotions as she faced difficulties. After the diagnosis of recurrence, she wrote: “The fear has been replaced by sadness, angry [sic], frustration and probably a bit more fear. It has only been 5 1/2 months since initial diagnosis…This so sucks…I am sad, angry, discouraged and my hope is fading.” When Darlene completed her 10th radiation treatments, she described that radiation was harder emotionally rather than physically: “I find the treatment difficult, emotionally. I don't know if it is going by myself, being left in the room as if you are a leper, the marking of the body, the caustic-sounding buzzer—I don't know, but radiation is harder than I expected—not physically though.” After her second recurrence was confirmed, unlike her expressed anger, fear and frustration at the time of her first recurrence, Darlene's emotions were mostly replaced by her worries toward her loved ones and her feeling sorry about reporting bad news over the discussion group. She wrote “it is so painful to watch the tortured emotions of those around us.” “This must be so hard for everyone. I feel almost guilty saying what is going on with me…but again, I wish not to drag anyone down. So far, I am still here!” During the last month, Darlene seemed accepting, recognizing the possibility of her death. She wrote: “for now, it's OK with me. I am happy, content. That is OK.”

Spiritual Expression

The “Spiritual Expression” subtheme was also a moderately reoccurring topic. The frequency patterns over time of these two subthemes regarding emotion and spirituality were highly parallel to each other with similar ascending and descending slopes as presented in Figure 3. The first time that Darlene talked about the spiritual /church support they received over the discussion group was around her first recurrence and how the recurrence incidence had an effect on the decision to meet the minister on a regular basis. The first church visit after her first recurrence, she wrote “We are both going in to meet with our minister tomorrow to talk about big issues - I imagine that we will begin meeting with her on a regular basis.” Darlene also continuously stated she would be praying for other CHESS women such as “I am still praying for a miracle…feeling heavy in the heart for Mary.” Attending church services and meeting her minister became part of her routine that she shared with others in the discussion group even as her condition was declining. “With the assistance of the wheelchair and friends, I went to church today. We got in lots of visits in a short time…What a gift to me.” In her very last good-bye message, she wrote “Did attend church with lots of help. I wish you all well and good health.”

Figure 3.

Pattern of “emotional and spiritual expression” message theme across the cancer trajectory

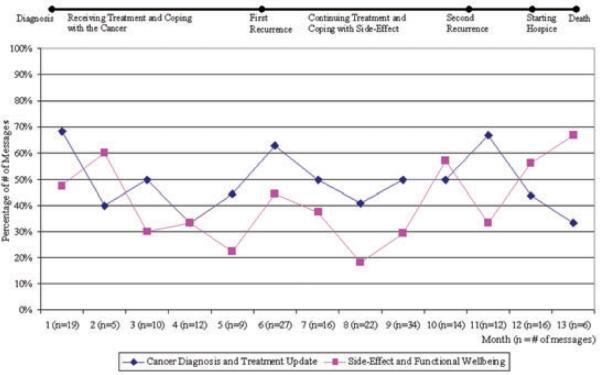

Cancer Treatment and Physical Update Theme

Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Update

The monthly percentage of the “Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Update” theme did not exceed 70% at any given time but it was the second most frequent sub theme in total. Darlene started her discussion group experience by introducing and discussing her diagnosis and treatment with other CHESS women. This was the most frequent subtheme across all 13 subthemes in the first month. An example of her message about her diagnosis and treatment at this time was “I was diagnosed only three weeks ago with BC and have had a mastectomy and port placement.” She also used discussion group as a place to track her treatment progression, for example, she updated the group with “I have completed #2 of A/C and I was told today that I am halfway through!…I will receive only four cycles of A/C - then Taxol, then XRT.” The “Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Update” subtheme increased dramatically at the time when Darlene detected her first recurrence. Discussion of her recurrence accounted for a large proportion of messages at month 6. She wrote “The lump turned out to be a recurrence…had a fine needle aspiration which revealed the lump to be cancerous.” Greater numbers of the “Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Update” subtheme messages were again posted during Darlene's second recurrence. She shared the bad news with the group “…the conclusion is three brand new lesions in the liver - probably mets. They completed the abdominal and chest CT yesterday…. I will go in for Herceptin on Wednesday.” When she stopped receiving curative treatment, she wrote “..the chemotherapy was stopped and I was referred to Hospice. Liver mets are continually growing and huge - nothing to stop them.”

Side-Effect and Functional Wellbeing

While receiving treatments (during month 2), 60% of her messages described the side-effects she was encountering. Darlene wrote “I continue to struggle with difficult side effects of chemotx. Cycle #3 has been the worst one for me; I was down for eight days with nausea and GI problems, including mouth sores and sore throat.” This “Side-Effect and Functional Wellbeing” subtheme had the second highest percentage at month 2 following the “Emotional Expression” subtheme. Right before Darlene's first recurrence, she had extensive discussion with others regarding side effects she was experiencing from her treatments. For example, she described her reaction to Taxol as “I also have pains starting about two days after, lasting about 3–5 days - they go all over - but mostly in the legs.” During the last month of Darlene's radiation treatment, right before her second recurrence, the “Side-Effect and Functional Wellbeing” subtheme messages increased as a result of her discussion on radiation skin—“the radiation burn is sure sore and most of the skin is coming off.” As she was physically deteriorating (especially in the last 2 months of her life) the “Side-Effect and Functional Wellbeing” subtheme received increasing postings. During this time, Darleen continuously reported her declining mobility -“The weakness losses continue to mount and this seems to be the worst part.” In her last message updating her condition with other CHESS women, she wrote “I have no energy whatsoever and am likely to be near-total care later this week.”

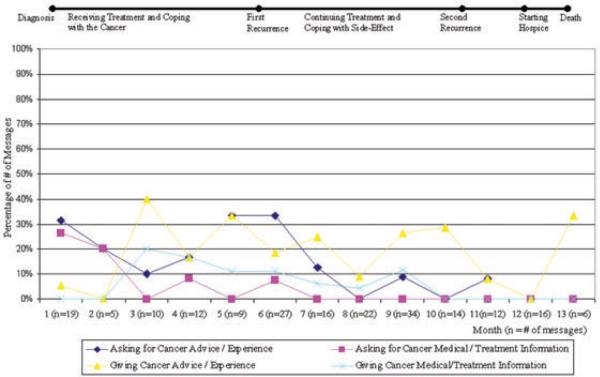

Cancer Treatment Information and Experience Exchange Theme

These four message themes describe the exchange process of generic cancer information and personal experience coping with cancer between Darlene and the other CHESS women (see Figure 5). In general, the monthly frequency percentages of these four themes did not exceed 40%. At the beginning of Darlene's cancer diagnosis and her CHESS discussion group use, Darlene posted more messages in the “asking” subthemes than the “giving” subthemes, then the pattern reversed immediately after two months. Personal experience and advice was more likely to be sought and given than generic cancer medical information.

Figure 5.

Pattern of “cancer treatment information and experience exchange” message theme across the cancer trajectory

Giving Personal Experience/Advice

After 2 months of CHESS participation, “Giving Personal Experience/Advice” became a frequent topic in Darlene's conversation, the most frequent subtheme in this theme group. She was describing how she coped with negative emotions to two other CHESS women who were feeling sad, she said “I have been trying so hard to maintain a positive attitude and be up all the time, that I was not allowing any sadness - her point was that the human spirit is all of those emotions - happy, sad, angry, joyous, frustrated, irritable, etc. - just let them be, she said. It worked for me! I felt better the next day! Do reach out to your support team, though, it really does help.” After her first recurrence, she continuously shared her advice and experience more than asked for others' until her death (even when she had a second recurrence). She addressed many personal experiences with treatments, side effects, and her coping strategies for minimizing both emotional and physical discomfort. She left a comment for another new CHESS woman “the roller coaster is to be expected. Turn to friends and family often and do not be afraid to ask for help - you will get better at asking as you progress.” The frequencies of her personal experience/advice giving subtheme declined when she started to face the possibility of death during the hospice care. However, once she realized her death was inevitable, the frequencies of her giving cancer advice/experience to others in the discussion group had a sharp increase. Most of her advice at the end was to explain how she coped with such an aggressive cancer.

Asking for Personal Experience/Advice

It was also quite common that Darlene asked other CHESS women for their input based on their experience. As she was starting chemotherapy, she posted “Questions for CHESS gals: 1) should I be afraid of chemotx? 2) what was the hardest part of chemotx for you? 3) how much time, if any, did you take off from work during chemotx? 4) pointers on getting through the next year? more importantly, the next week (or day)?” Many of her messages at this time addressed her questions regarding specific treatment (chemotherapy) and inquired strategies to manage it. The peak in Darlene using this subtheme was at the time of her first recurrence. She was very frustrated and asked others if she was alone - “Has anyone else had this (recurrence) so soon?” During this difficult time, nearly 35% of Darlene's message content inquired others' recurrence experience. As she continued receiving treatment, Darlene also requested others' coping strategies with side effects. She posted “To anyone who received radiation therapy: do you remember itching with raised rash-like areas over the spots being radiated? If so, what did you do! did you experience metallic taste in your mouth during the treatment?” As her condition declined, her questions to others did not concern treatments and side effects anymore. She was looking for ways to continuously cope with bad news. She wrote “Any ideas for my mother?—this hurts. Is there anything to soothe?”

Giving Cancer Medical/Treatment Information

In her explanations to one of the new CHESS users, she said that “The navelbine and gemcitabine are both vesicants.” She addressed many medical issues including how diagnosis and recurrence were assessed, as well as type of treatments with potential benefits and risks. She explained the diagnosis procedures to another woman as “..no they cannot determine metastatic disease from auscultation (listening) of the lungs .. to confirm metastatic disease, a CT (or chest xray) and then a biopsy would be required.” Darlene consistently answered others' questions regarding breast cancer medical information until the time of her second recurrence.

Asking for Cancer Medical/Treatment Information

This subtheme was more pertinent between the time of Darlene's diagnosis and first recurrence. For example, within the 2 weeks of her diagnosis, she asked the group “I just found out today that my tumor was Her-2-neu negative. Does anyone know what that means? I have forgotten the significance of the test.” As she was coping with the diagnosis and new treatment of her first recurrence, she asked “after the CTs he (the doctor) will reveal the new cocktail - he mentioned Zeloda - does anyone know anything about that?” After her first recurrence diagnosis, Darlene rarely posted any question inquiring medical information regarding breast cancer.

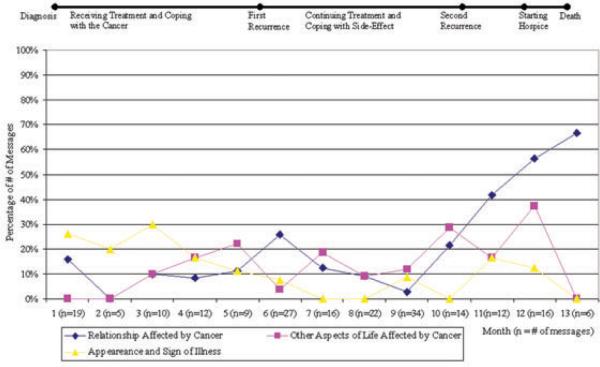

Cancer Impact Theme

Relationship Affected by Cancer

Darlene's worries about the impact of her illness on her loved ones increased over time. The first time she described her mom's reaction to her diagnosis over the discussion group, she wrote: “My mother is and has been devastated—she keeps saying it should have been her ….I feel for her and wish I could take away her bad feeling.” While waiting for another CT scan to confirm her first recurrence, Darlene expressed her worry about those supporting her continually getting bad news: “I and my support system are so tired of bad news! My partner has a cascade of phone calls that she makes after every appointments—I feel so bad for her—calling everyone with bad news.” As she transitioned from curative care to hospice after the second recurrence, Darlene's concern for her mother continuously increased, resulting in an increase in this subtheme from month 11 to month 13. She posted about her mom “total devastated and I could only hear my mother crying and whimpering in the background—it is so painful to watch the tortured emotions of those around us.” As she approached the end of life, she wrote about how her parents coped with her dying “My folks have gone back home for a few days to get support from their own system.”

Other Aspects of Life Affected by Cancer

Other aspects of her life were also affected by her breast cancer, such as employment and financial issues. For example, concerning an issue of considering Chinese medicine treatment, she wrote “There is no way I can afford that - I am still on disability, earning only 60% of usual salary. So, now I don't know what to do.” She expressed her frustration about canceling a Christmas trip due to treatment schedule “we cancelled the trip because of chemotx, so I am also kind of pissed off about that. Cancer really is a pain.” Darlene also shared with the group about her wish to increase work hours: “I have been working 25% time since then and hope to increase to 50% next week. I think I am ready to increase and enjoy being at work.”

Appearance and Sign of Illness

Like many women with breast cancer, Darlene was concerned about her appearance as a result of cancer treatments (such as hair loss). The “Appearance and Sign of Illness” subtheme percentage reached its peak at month 3. During this month, the messages were mostly related to coping with her hair-loss and adjustment after her mastectomy. She was referred to as a gentleman by a nurse while receiving treatments for nausea. She said: “I did have my hair cut short, but it is still in a feminine, cute style. I was already feeling bad and felt even worse after this insensitive remark.” She demonstrated that she took control over cancer by her statement “I shaved my head on Monday—I am glad to have done it—on my own terms!” She described her decision for no breast reconstruction as “my breasts were small to start with and I hate surgery and medical instrumentation of any kind. The less time I can spend in surgery, the happier I will be.” She told other CHESS women that “So, I can go there and swim without a breast form and feel perfectly fine in my new bathing suit.” While receiving radiation after her first recurrence, she expressed her frustration of being visibly ill. She wrote “Radiation therapy personnel made me ride in a wheelchair through the hospital, citing `ospital policy' which was also difficult because it reminds me that I am ill.”

Death and Dying Theme

We were also interested in how patients facing a potentially terminal illness would discuss death and dying through online support group, especially when death is imminent. We tracked the frequencies of Darlene's messages that discussed death (be it her own, or the death of others around her).

Death and Dying—Others

When her grandmother died from a sudden massive heart attack, Darlene wrote “Being with her at the time of her death was a gift - the meaning of which I may never understand.” When Mary, the CHESS woman that Darlene referred to as her twin because of their similar diagnosis and received treatment, was dying, Darlene wrote “I am especially filled with thoughts of Mary. she impacted my life in a major way - I will miss her.” On the day of Mary's funeral, Darlene posted “My heart is very heavy at this moment, - I believe Mary's funeral gets underway in 10 minutes. So, so sad.” She also explained to and validated another CHESS woman's decision not to attending Mary's funeral by “I understand your hesitation about going to the funeral. I, too, really wanted to go. When Friday morning arrived though, I felt strongly that I should go back home and be with my parents - so I acted on that feeling.”

Death and Dying—Self

Darlene rarely discussed the possibility or fear of her death before staring hospice care. When her condition started declining, she was struggling to face of the fact that she was dying. She said “Folks are stopping by in droves. It is a strange feeling - it is as if folks think I am dying - and I really do not think that - although I feel worse and worse by the day. It is all very confusing.” As her death got closer there was a dramatic increase in the number of messages posted on dying. As she seemed to recognize that her death was inevitable, she wrote: “My body is quickly declining and we know not when the time will come.” She described again that she had many visitors during this process: “There are also lots of folks stopping over, wanting to do their own - kind of, dying work - it is very strange and hard to explain, but lots of work for me.” In Darlene's very last good-bye message, she explained her deteriorating condition and acknowledged that she would not be able to post again. She said “I have shown Cathy how to post on here and she is likely the next one you will hear from.”

Discussion

Previous research suggests that face-to- face support groups can enhance coping, reduce adverse emotional responses to cancer and help participants resume previous life activities (Taylorm, Falkem, Mazel, & Hilsberg, 1988; Lindemalm, Strang, & Lekander, 2005). Support groups for metastatic breast cancer can also detoxify dying, reduce anxiety, and improve quality of life (Goodwin et al., 2001). Until recently, little research has been done with computer-mediated support groups, particularly for people facing the end of life. This case study gives us a glimpse into how one woman faced with terminal breast cancer exchanged information, support and emotions with others in a peer-led, but closed computer-mediated breast cancer discussion group.

Message Patterns Triggered by Emotionally Charged Events

The number of messages that Darlene posted and the themes of the messages were clearly correlated with the specific medical events (recurrence, deteriorating health, needing hospice, etc.). The number of messages posted and the proportion of messages that contained emotional expressions increased at the time of her cancer recurrences and when she was entering the end of her life. This finding is consistent with the finding that emotional writing is correlated with these distress-inducing events (Pennebaker, 1997). Even though participants in online support groups are not guided for expressive writing tasks, they naturally share their emotions and feelings that are often perceived as being too difficult to share with loved ones when needed most.

On many occasions when Darlene posted messages during an emotionally charged event, she would receive immediate supportive and empathic responses from the other support group members. Traditional face-to-face support groups might not be able to provide support for events that occurred outside of the group in a timely fashion. For example, when Darlene was coping with the fear of recurrence with an unconfirmed lump she used the discussion group to release her emotions and then acknowledged the group's support within 36 hours. This phenomenon of receiving emotional support at the most critical times also highlights the value of online support groups for their greater availability and access than traditional face-to-face support groups. Our findings also clearly suggest the need for tailored psychosocial interventions at specific key critical events across the cancer trajectory.

Emotional Support Exchange

Providing emotional support to others appeared to be an important component of Darlene's interaction with other CHESS women. This subtheme continually increased throughout the 13-month timeline since Darlene joined the CHESS discussion group. The only exception is when she was dealing with her second recurrence of cancer and the start of hospice care, the proportion of her messages contained relatively less emotional support for others at this difficult time. In offering support for others, she typically validated their feelings by reiterating her own similar views and experiences. She also constantly sent her wishes, encouragement, and empathy when her peers were in need. This mirrors the work of Sharf (1997) who found that almost all postings on a Breast Cancer List included some form of encouragement. We also found that the frequencies of Darlene's messages explicitly requesting emotional support were far less than those in which she actively offered support to others. This finding is consistent with results from several other studies that reported online messages containing more offers than requests (Klaw, Huebsch, & Humphreys, 2000; Winzelberg, 2003; Lasker, Sogolow, & Sharim, 2005). It is possible that being able to offer help is a more empowering coping mechanism than to ask for help, and perhaps more rewarding.

Though Darlene rarely explicitly stated her needs for emotional support from other women, a close examination of message sequence of Darlene's interaction with other women found out that in general, expressing a negative emotion (toward an event) would elicit emotional support and comments from other women for Darlene and vice versa. Emotional support was often posted as a response to venting, where people expressed their frustration with a particular event (Coulson, 2005). Our findings are similar to those concluded by Preece (1999) and Pfeil & Zaphiris (2007) that people online rarely ask for support directly, instead, they tell their stories and feelings to trigger an empathic response from their peers. It was concluded that self-disclosure might be more appropriate as a trigger than a direct request in online communities since it gives the necessary contextual details about the event or the situational information that would otherwise be conveyed non-verbally. For example, Darlene wrote “I am sitting here so afraid tonight (about the potential recurrence),” which immediately triggered supportive and empathic messages from others. This phenomenon also explains the high volume of the Appreciation for Support from Other CHESS Women subtheme in Darlene's messages.

Online Emotion Expression

In our findings, Darlene heavily used the discussion group as a channel to express her personal emotions (69% of the messages). These data are not consistent with some other online content analysis studies which found the most primary themes to be information seeking and giving. For example, Meier et al. (2007) reported that information regarding specific treatments was a dominant discussion topic in all 10 cancer lists they studied. One possible explanation is that, unlike other peer-to-peer online support groups, CHESS additionally provides comprehensive cancer diagnosis and treatment information, personal stories, decision tools, etc. which could have already met Darlene's informational needs. The comprehensiveness of the CHESS program may also contribute to the fact that we rarely saw Darlene or other group members discussing other websites. Another possible explanation is that women tend to express feelings and support rather than educational information (Klemm et al., 1999; Preece, 1999).

In addition to receiving peers' emotional support from writing about her feelings, as we argue above, another possible reason to write about feelings is the therapeutic effects for the writer of expressing personal emotions (Smyth, Stone, Hurewitz, & Kaell, 1999). In a randomized trial, four sessions of written expressive disclosure produced lower physical symptom reports and medical appointments among breast cancer patients compared with a control group (Low, Stanton, & Danoff-Burg, 2006). Gellarity et al. (2009) found that expressive writing was associated with a higher level of satisfaction with emotional support among women completing breast cancer treatment (Gellaitry, Peters, Bloomfield, & Horne, 2009). Other research has also indicated that emotional processes that takes place in online support groups may generate the experience of personal empowerment (Barak, Boniel-Nissim, & Suler, 2008). The act of emotional writing online provides an emotional outlet and a sense of cognitive order. It can also result in peer interactions and relationship bonding, which can reduce isolation and enhance emotional reinforcement, leading to a feeling of personal empowerment and improved self-confidence (Barak & Dolev-Cohen, 2006; Høybye, Johansen, & Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, 2005). Darlene gained a sense of control and empowerment by actively sharing her story online in the discussion group. Our findings suggest further validation of the value of expressive writing in a computer-mediated online peer support group for breast cancer patients attempting to reintegrate into life and cope with the challenges associated with a threatening disease and end of life.

In addition, as demonstrated by the “Noncancer-Related Life Sharing” subtheme, Darlene and others built their friendship and relationship by sharing their thoughts and life beyond their cancer concerns (including acknowledging each others' birthdays, children, and family events). Being able to share life events and feelings with similar others helps decrease a sense of isolation often felt by those faced with a serious illness. Researchers should gain deeper understanding of the underlying cognitive process of disclosure to identify the most effective ways for developing future health communication interventions.

Sharing Medical Histories and Progression to Identify and Form Similarity With Others

Discussion group members entered basic treatment and diagnosis information in the “About Me” section when they first were trained on CHESS. This included things such as date of diagnosis, stage of cancer (if they knew that information) and types of treatment they had or were planning. We did not require participants to update this section. Darlene (and other CHESS women) regularly shared their medical histories and illness progression with each other in the discussion group. This updating helped create and maintain relationships and connection with others who were medically similar. Similar others' medical information was potentially used as a means to estimate the likelihood of treatment outcome or long-term survival. For example, Darlene paid special attention and continuously inquired about two other women in the discussion group who had similar prognoses and treatments. She compared her disease progression over time to these two similar others. As Darlene faced new treatment options or experienced side-effects, Darlene connected with others who had gone through that particular treatment to learn about their experiences and how they coped. Knowing the situation of having “been there” from similar others gave Darlene more knowledge and experience that could help her to assess her challenges and to feel she was not alone. This pattern of narrating and updating diagnoses, treatments and outcomes, and current health status was also reported as a common theme in other online cancer support groups (Meier et al., 2007). It was also concluded that providing personal narratives and medical case histories was a way of offering empathic communication, strengthening the group's solidarity, and reducing individuals' sense of isolation (Preece, 1998; Meier et al., 2007).

The present pattern of manually updating medical information over time to initiate and continue networking communication on an online bulletin board-formatted discussion group suggests the potential for intervention redesign that will facilitate and capitalize the cancer patient's medical and personal data exchange through more efficient interface functions. More other, future studies also need to examine the functionality of Web 2.0 technologies and/or semantic web tools that enable social networking, participation, and collaboration among peers. Different modes of networking tools, such as one-to-one (MSN), one-to-many (Twitter), and many-to-many (Facebook), may facilitate different kinds of peer communication and relationships at different points in time by people living with an illness. The strong push for Personal Health Records (PHRs) which allows patients to electronically integrate their medical records and to authorize their records to be shared with certain parties, providing great potential for online social networking and support via the connection of PHRs (Detmer, Bloomrosen, Raymond, & Tang, 2008). Research into the strategies that these emerging technologies could impact and support patients is a promising new direction. In addition to PHRs, future online support group research needs to take demographic background (i.e. ethnicity, sexual orientation) into design consideration, which will facilitate further formulation of peer similarity and relationship. For example, by sharing her diagnosis and treatment course Darlene was able to build relationships with other members who had similar medical background. However, she also disclosed to the group that she was a lesbian and acknowledged that she was looking for a lesbian breast cancer support group. In her messages, the challenge of accessing lesbian-specific support group was present, warranting specific support needs for different minority groups.

Family Coping and Patient-Family Communication

A concern that came up repeatedly was the guilt that Darlene felt as those close to her—especially her parents and her partner, dealt with her breast cancer and its progression. Not only does a person facing a life-threatening illness have to deal with the disease itself, but they have the burden of seeing others suffer as a result of their illness. Concerns regarding communicating with her loved ones were highest when she learned about her recurrences and as hospice became involved. While there is research on how doctors communicate bad news to patients, there is little research about how patients communicate that news to their loved ones. Open communication is likely to be of particular importance in the family setting in the context of an end-of-life event, as the family is frequently a primary source of support. Several studies report that the importance of patient-family communication is indicated by its strong predictive power of patient and family adjustment to cancer- and health- related outcomes (Walsh-Burke, 1992; Kissane, Bloch, Burns, McKenzie, & Posterino, 1994; Fried, Bradley, O'Leary, & Byers, 2005; Mallinger, Griggs, & Shields, 2006). Thus, interventions need to address information and strategies to help patients and families adjust to the reality of illness and communicate news (such as cancer recurrence, and even the possibility of death) to each other to lessen patients' and family members' coping and emotional distress.

Death and Dying Issues in Online Communities

Darlene and other support group members expressed concern when others failed to log on for some time. They shared messages about not wanting to log on knowing that they lost another CHESS friend from breast cancer. It was like previewing the likely consequences of their own breast cancer battles. Darlene also acknowledged the fact that she was greatly impacted by Mary's death (another group member who she compared herself to) and was reluctant to attend Mary's funeral given her emotions. This dilemma points out the challenge of offering peer support and handling one's own personal fears and emotions. Although Darlene and other members showed their unease with others' death, their discussion regarding death and dying simply scratched the surface. Vilhauer (2009) reported that many women in an online metastatic breast cancer support group did not feel comfortable discussing death and dying, warranting future research on this sensitive but inevitable topic in online cancer communication.

As Darlene learned that she was dying, she paid special attention to advise other women not compare their breast cancer to hers. This also points out again that in online support groups there might be potential harm of distress triggered by the death of peers who users find themselves similar to and are emotionally involved with. In the future, protocols need to be developed to help participants prepare for peers' deaths to minimize potential stress and to facilitate death and dying support.

Study Limitation

This was a case study that may not be fully representative of other women with terminal breast cancer. As Thorne argues (2009), a single narrative case study might represent pre-existing bias and a matter of opinions. We acknowledge the fact that the generalizability of the study results is limited and restricted, although findings from our in-depth analysis are parallel with findings from other studies as reported above. Case studies such as this, gives the reader a richer understanding of how electronic discussion groups are used by people facing a life threatening illness.

Conclusion

Coping with an advanced cancer is a challenge. Many patients need guidance and support to encounter difficulties associated with an unfamiliar illness. Health professionals fulfill part of this role, however many patients inevitably seek out other patients who have been through the experience and can offer personal support and guidance. Darlene coped with her diagnosis in a variety of ways throughout the 13-month journal seen through her CHESS discussion group messages from diagnosis to death. She asked numerous questions of the discussion group members, wanting to learn how they coped with chemotherapy or radiation side effects, second recurrences, etc. She also answered numerous questions and provided support to others who were on her discussion group network. This study adds to the growing literature on the value of online support groups. First, our methodology represents a novel and potentially important route through which cancer education and communication researchers can understand more fully the challenges a breast cancer woman faces across the cancer trajectory. In practice, patient narratives can also be used in educating and training health care professionals to understand the patient's perspectives and identify potential gaps in current evidence-based practice. Second, using a case study approach, we validated the theoretical relationship between expressive writing and emotionally charged events over time. Third, our findings suggest the potential need for future intervention redesign utilizing social networking or PHRs-integrated technologies to more efficiently facilitate the formulation of peer relationship and communication. Fourth, our findings are also consistent with the literatures that patients use the online support groups to process emotions, facilitate self coping, and enhance self-empowerment through the use of information and support exchange with peers.

This qualitative online case study highlights the power that writing and sharing one's journey can have, not only for the individual writing messages, but also for those reading the messages. More research is needed to understand if sharing one's story with others via an electronic format changes the way one copes with an illness and/or changes how other support group members perceive their own illness. An obvious next step in this line of research is to replicate the longitudinal study of online posting qualitative analysis with more case studies. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine if involvement in an online support group influences one's social network, length of survival, quality of life, etc. Little is known about the difference in process and outcomes between research-based online support groups and those peer-led self-forming groups on the internet. We have found from our past research that the level of support exchange and group cohesiveness in the CHESS discussion group is usually very high, resulting that many of the study participants stay in contact for years after the research ends. The bonds formed in many of our discussion groups have resulted in life long friendships. Several of our very early study participants (well over 10 years ago) remain in contact with each other and some groups have an annual face to face meeting. Future research should focus on studying the implications for social support over time between professionally led research-based systems and patient led self-help venues. As Eysenbach et al. (2004) concluded that research community needs to develop a guiding principle of online support groups that best facilitates patient's self-helping process regardless of the venue in which they occur.

Figure 4.

Pattern of “cancer treatment and physical update” message theme across the cancer trajectory

Figure 6.

Pattern of “cancer impact” message theme across the cancer trajectory

Acknowledgement

Data reported in this paper is part of the CHESS DOD study funded by the Department of Defense (grant # DAMD17-981-8259). We would also like to thank the women who agreed to participate in our study.

Biography

Kuang-Yi Wen is a Research Assistant Professor of Cancer Prevention and Control at Fox Chase Cancer Center. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin—Madison at the department of Industrial Systems and Engineering with a focus on health systems engineering and decision science. Her research interests center on leveraging health information technologies to improve patient-centered care.

Address: 3rd Floor, 510 Township Line Road, Cheltenham, PA 19012.

Fiona McTavish is a Researcher at the Center for Health Enhancement Systems Studies and Deputy Director of the Center of Excellence in Cancer Communications Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She is known as an extremely passionate advocate on behalf of women with breast cancer, putting a human face on research and inspiring researchers by linking them to the stories of real people.

Address: Center for Health Enhancement Systems Studies, University of Wisconsin, 1513 University Avenue, Madison, WI 53706.

Gary Kreps is Professor and Chair of the Department of Communication at George Mason University. His research focuses on health communication and promotion, information dissemination, cancer prevention and control, organizational communication, informationtechnologies, multiculturalrelations, andrisk/crisismanagement.

His published work includes approximately 250 books, articles, and monographs concerning the applications of communication knowledge in society.

Address: DepartmentofCommunication,GeorgeMasonUniversity,206aThompson Hall, MS 3D6, Fairfax, VA 22030-4444.

Meg Wise, PhD is an Associate Scientist at the Center for Health Enhancement Systems Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She investigates the effects of life review and social networking on the well-being of people with advanced cancer.

Address: Center for Health Enhancement Systems Studies, University of Wisconsin, 1513 University Avenue, room 4155-B, Madison, WI 53706.

David Gustafson is Research Professor of Industrial and Systems Engineering, and Director of the Center for Health Enhancement Systems Studies, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Dave's interests in decision, change and information theory applied to health systems come together in the design and evaluation of systems and tools to help individuals and organizations cope with major changes. His research teams have created systems to detect suicidal propensity, help teenagers adopt healthy behaviors, and help families facing major health crises cope more effectively. That work focuses on the Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (CHESS), a computer system to help people facing serious situations such as breast and prostate cancer, asthma, AIDS/HIV, heart disease, Alzheimer's disease, and sexual assault.

Address: 4109 Mechanical Engineering Building, 1513 University Avenue, Madison, WI 53706-1572.

References

- Boehmke M, Dickerson S. The diagnosis of breast cancer: Transition from health to illness. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2006;33(6):1121–1127. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.1121-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak A, Boniel-Nissim M, Suler J. Fostering empowerment in online support groups. Computers in Human Behavior. 2008;24(5):1867–1883. [Google Scholar]

- Barak A, Dolev-Cohen M. Does activity level in online support groups for distressed adolescents determine emotional relief. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2006;6:186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MK, Meier A, Carr C, Enga Z, James AS, Reedy J, Zheng B. Health behavior changes after colon cancer: A comparison of findings from face-to-face and on-line focus groups. Fam-Community-Health. 2001;24(3):88–103. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen C, Butler LD, Koopman C, Miller E, DiMiceli S, Giese-Davis J, et al. Supportive-expressive group therapy and distress in patients with metastatic breast cancer: A randomized clinical intervention trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(5):494–501. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulson NS. Receiving social support online: An analysis of a computer-mediated support group for individuals living with irritable bowel syndrome. Cyberpsychology & Behavior. 2005;8(6):580–584. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detmer D, Bloomrosen M, Raymond B, Tang P. Integrated personal health records: Transformative tools for consumer-centric care. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2008;8(1):45. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G, Till JE. Ethical issues in qualitative research on internet communities. British Medical Journal. 2001;323(10):1103–1105. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7321.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G. The impact of the internet on cancer outcomes. Cancer Journal of Clinicians. 2003;53:356–371. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.6.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G, Powell J, Englesakis M, Rizo C, Stern A. Health related virtual communities and electronic support groups: Systematic review of the effects of online peer to peer interactions. BMJ. 2004;328(7449):1166–1170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel J, Albert SM, Schabel F, Ditkoff BA, Neugut AI. Use of the Internet by women with breast cancer. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2002;4(2):E9. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4.2.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel J, Albert SM, Schanbel F, Ditkoff BA, Neuget AI. Internet use and social support in women with breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2002;21(4):398–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried TR, Bradley EH, O'Leary JR, Byers AL. Unmet desire for caregiver-patient communication and increased caregiver burden. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(1):59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz PA, Coscarelli A, Fred C, Kahn B, Polinsky ML, Petersen L. Breast cancer survivors: Psychosocial concerns and quality of life. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 1996;38(2):183–199. doi: 10.1007/BF01806673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellaitry G, Peters K, Bloomfield D, Horne R. Narrowing the gap: the effects of an expressive writing intervention on perceptions of emotional support in women who have completed treatment for early stage breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;19(1):77–84. doi: 10.1002/pon.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Aldine Publishing Co; Chicago, IL: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gray R, Fitch M, Davis C, Phillips C. A qualitative study of breast cancer self-help groups. Psycho-Oncology. 1997;6(4):279–289. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199712)6:4<279::AID-PON280>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, McTavish F, Hawkins RP, Pingree S, Arora N, Mendenhall J, et al. Computer support for elderly women with breast cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280(15):1305. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.15.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Boberg E, Owens BH, Sherbeck C, Wise M, et al. Empowering patients using computer based health support systems. Quality in Health Care. 1999;8:49–56. doi: 10.1136/qshc.8.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Pingree S, McTavish F, Arora N, Mendenhall J, et al. Effects of computer support on younger women with breast cancer. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:435–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Boberg EW, McTavish F, Owens B, Wise M, et al. CHESS: 10 years of research and development in consumer health informatics for broad populations, including the underserved. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2002;65:169–177. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(02)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Stengle W, Ballard D, Hawkins R, Shaw B, et al. Use and impact of eHealth System by low-income women with breast cancer. Journal of Health Communication. 2005;10:195–218. doi: 10.1080/10810730500263257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin PJ, Leszcz M, Ennis M, Koopmans M, Vincent J, Guther L, et al. The effect of group psychosocial support on survival in metastatic breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:1719–1726. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høybye MT, Johansen C, Tjørnhøj-Thomsen T. Online interaction: Effects of storytelling in an internet breast cancer support group. Psycho-Oncology. 2005;14(3):211–220. doi: 10.1002/pon.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiung RC. The best of both worlds: An online self-help group hosted by a mental health professional. Cyberpsychology & Behavior. 2000;3(6):935–950. [Google Scholar]

- Im EO, Chee W, Tsai HM, Lin LC, Cheng CY. Internet cancer support groups: A feminist analysis. Cancer Nursing. 2005;28(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissane DW, Bloch S, Burns WI, McKenzie D, Posterino M. Psychological morbidity in the families of patients with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1994;3(1):47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Klaw E, Huebsch P, Humphreys K. Communication patterns in an on-line mutual help group for problem drinkers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(5):535–546. [Google Scholar]

- Klemm P, Hurst M, Dearholt S, Trone S. Cyber solace: Gender differences on internet cancer support groups. Computers in Nursing. 1999;17(2):65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm P, Reppert KG, Visich LG. A nontraditional cancer support group: The Internet. Computers in Nursing. 1998;16(1):31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasker JN, Sogolow ED, Sharim RR. The role of an online community for people with a rare disease: Content analysis of messages posted on a primary biliary cirrhosis mailinglist. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2005;7(1):e10. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemalm C, Strang P, Lekander M. Support group for cancer patients. Does it improve their physical and psychological wellbeing? A pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:652–657. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0785-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low CA, Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S. Expressive disclosure and benefit finding among breast cancer patients: Mechanisms for positive health effects. Health Psychology. 2006;25(2):181–189. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luker K, Beaver K, Leinster S, Owens GR. Information needs and sources of information for women with breast cancer: A follow-up study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1996;23:487–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madara E, White BJ. On-line mutual support: The experience of a self-help clearinghouse. Information & Referral. 1997;19:91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinger JB, Griggs JJ, Shields CG. Family communication and mental health after breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2006;15(4):355–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclean B. Social support, support groups, and breast cancer: A literature review. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 1995;14(2):207–227. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-1995-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTavish FM, Pingree S, Hawkins RP, Gustafson D. Cultural differences in use of an electronic discussion group. Journal of Health Psychology. 2003;8:105–117. doi: 10.1177/1359105303008001447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]