Abstract

Background

Cardiac myosin binding protein-C (cMyBP-C) is a sarcomeric protein that dynamically regulates thick filament structure and function. In constitutive cMyBP-C knock-out (cMyBP-C−/−) mice, loss of cMyBP-C has been linked to left ventricular (LV) dilation, cardiac hypertrophy, and systolic and diastolic dysfunction, although the pathogenesis of these phenotypes remains unclear.

Methods and Results

We generated cMyBP-C conditional knock-out (cMyBP-C-cKO) mice expressing floxed cMyBP-C alleles and a tamoxifen-inducible Cre-recombinase fused to two mutated estrogen receptors to study the onset and progression of structural and functional phenotypes due to the loss of cMyBP-C. In adult cMyBP-C-cKO mice, knock-down of cMyBP-C over a 2 month period resulted in a corresponding impairment of diastolic function and a concomitant abbreviation of systolic ejection, although contractile function was largely preserved. No significant changes in cardiac structure or morphology were immediately evident; however, mild hypertrophy developed after near-complete knock-down of cMyBP-C. In response to pressure overload induced by transaortic constriction, cMyBP-C-cKO mice treated with tamoxifen also developed greater cardiac hypertrophy, LV dilation, and reduced contractile function.

Conclusions

These results indicate that myocardial dysfunction is largely due to the removal of cMyBP-C and occurs prior to the onset of cytoarchitectural remodeling in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium. Moreover, near ablation of cMyBP-C in adult myocardium primarily leads to the development of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in contrast to the dilated phenotype evident in cMyBP-C−/− mice, highlighting the importance of additional factors such as loading stress in determining the expression and progression of cMyBP-C-associated cardiomyopathy.

Keywords: cardiomyopathy, heart failure, hypertrophy, myocardial contraction, remodeling

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is an autosomal dominant disease of the myocardium characterized by left ventricular hypertrophy, myocyte disarray, interstitial fibrosis, and diastolic dysfunction in the absence of known precipitating factors (e.g. hypertension, aortic stenosis). In addition to being the leading cause of sudden cardiac death in young athletes 1, HCM is among the most common genetic diseases of the heart, affecting approximately 1 in 500 people 2. Consequently, systematic investigations into the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of HCM are of clinical importance, particularly because phenotypic expression of HCM can lead to significant morbidity and mortality in a wide range of patient age groups 3, 4.

Among the most common targets of HCM mutations include the gene encoding the cardiac isoform of myosin binding protein-C (cMyBP-C) 5, 6, a thick filament accessory protein found in the A bands in myocardial sarcomeres. Unlike other HCM-associated genes, the majority of cMyBP-C gene mutations are predicted to encode truncated proteins that lack various C-terminal binding domains 7 involved in targeting cMyBP-C to the thick filament 8. Consequently, truncation mutants of cMyBP-C are likely unable to incorporate properly into the sarcomere 9 and are rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system of the cell 10. Consistent with this idea, detectable levels of truncated cMyBP-C have yet to be reported in human myectomy samples harboring heterozygous truncation mutations 11–13, although several studies have reported a reduction in the levels of endogenous cMyBP-C 11, 13. These findings lend credence to the hypothesis that cMyBP-C insufficiency contributes to the pathogenesis of HCM. Accordingly, greater losses of cMyBP-C may account for the enhanced phenotypes observed in patients harboring homozygous 14 or compound heterozygous cMyBP-C gene mutations 15, as well as the clinical finding that a subset of patients with HCM also later develop left ventricular (LV) dilation and systolic dysfunction pathognomonic for dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) 14, 16, otherwise known as “burnt out” phase HCM, end-stage HCM, or HCM-associated dilation. Still other patients with cMyBP-C gene mutations bypass the clinical expression of HCM altogether and are initially diagnosed as having DCM 17, 18. The mechanisms whereby loss of cMyBP-C results in the clinical expression of HCM, HCM-associated dilation, or DCM, however, remain to be elucidated and require further understanding of the roles of cMyBP-C in regulating cardiac structure and function in vivo.

Over the past decade, several unique mouse models have been generated to determine whether eliminating the expression of cMyBP-C (cMyBP-C−/−) 19, 20 or expressing very low amounts of truncated cMyBP-C (cMyBP-Ct/t) 21 is sufficient to cause cardiomyopathies and how the loss of cMyBP-C leads to the pathophysiology of these diseases. Initial studies in cMyBP-C−/− 19, 20 and cMyBP-Ct/t 21 mice have demonstrated marked LV dilation, myocardial hypertrophy, impaired relaxation, and depressed systolic contractility, leading to the conclusion that complete or near complete loss of cMyBP-C is sufficient to cause the development of HCM-associated dilation 19, 20 or DCM 21. Mechanical measurements on cMyBP-C−/− skinned myocardium have also demonstrated changes in contractility at the sarcomeric level 22–24, raising the possibility that functional derangements associated with removing cMyBP-C underlie the development of cardiac dysfunction in cMyBP−/− and cMyBP-Ct/t mice. A critical gap, however, exists with respect to our understanding of the extent to which loss of cMyBP-C directly contributes to the pathogenesis of cardiac dysfunction. Since characterization studies of cMyBP−/− and cMyBP-Ct/t mice hitherto have largely elucidated the end-stage phenotypes of cMyBP-C ablation, relatively little is known regarding the early changes that occur specifically in response to loss of cMyBP-C. Thus, it is unclear whether functional phenotypes in these mice reflect primary responses of the heart due to removal of cMyBP-C or secondary responses of the heart due to activation of compensatory mechanisms following the removal of cMyBP-C. Given the prominent effects of constitutive cMyBP-C ablation (or near ablation) on LV architecture and geometry, it is important to determine whether the direct loss of cMyBP-C predominately mediates the functional derangements observed in cMyBP-C−/− and cMyBP-Ct/t mice or whether the development of cardiac hypertrophy and LV dilation drives the expression of diastolic 25 and systolic dysfunction 26.

In the present study, we developed a tamoxifen-inducible cMyBP-C conditional knockout (cMyBP-C-cKO) mouse model utilizing Cre/loxP technology to dissociate the primary effects of removing cMyBP-C from the secondary effects of cardiac hypertrophy and LV dilation on cardiac function in vivo. Since cardiac dysfunction had previously been reported to precede the onset of LV remodeling in other mouse models of HCM 27, 28, we hypothesized that conditional knock-down of cMyBP-C would allow us to isolate the early consequences of removing cMyBP-C before the development of compensatory remodeling, thereby enabling us to unequivocally determine the functional roles of cMyBP-C in the intact heart. Using transthoracic echocardiography, we studied the onset and progression of structural and functional phenotypes due to the near-complete knock-out of cMyBP-C in adult tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice and compared these findings to age-matched cMyBP-C−/− mice previously generated in our laboratory 19. Adult cMyBP-C-cKO mice treated with tamoxifen were also subject to mechanical pressure overload induced by transaortic constriction (TAC) to determine the consequences of removing cMyBP-C in the context of hemodynamic stress.

Methods

A detailed description of materials and methods can be found in the online data supplement.

Experimental animals

The strategy of Liu et al29 was used to construct the conditional knock-out (cKO) targeting vector for the cMyBP-C gene (Mybp3). Mice homozygous for the targeted Mybp3 allele (Mybp3fl-NEO/fl-NEO) were crossed with FLPeR deleter (FLPeR+/+) mice 30 (Jackson Laboratory) to remove the neomycin (NEO) cassette. Mice homozygous for the floxed Mybp3 allele (Mybp3fl/fl) were then bred to α-MyHC-MerCreMer+/+ mice 31 (Jackson Laboratory) and bred back to Mybp3fl/fl to produce Mybp3fl/fl α-MyHC-MerCreMer+/− mice, i.e., cMyBP-C-cKO mice. All procedures involving animal care and handling were approved by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health Animal Care and Use Committee.

Knock-down of cMyBP-C

40 mg kg−1 tamoxifen (Sigma) was administered to 12-week-old cMyBP-C-cKO mice of either sex by intraperitoneal injection for 7 days to induce knock-down of cMyBP-C. Hearts from tamoxifen- and vehicle-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice were collected subsequently at 2 week intervals to determine the extent of cMyBP-C knock-down.

Protein analysis

Myofibrillar proteins were isolated from frozen ventricles, separated via SDS-PAGE, and visualized with silver staining. Western blotting was performed using primary antibodies to cMyBP-C (1:2000) and β-actin (1:400) and secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen), respectively.

RNA analysis

Total RNA was isolated from frozen ventricles using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription of total RNA was performed using oligo-d(T) primers and Superscript Reverse Transcriptase III (Invitrogen) to generate total cDNA. Gene expression was assessed using commercial Taqman assays (Applied Bio-Systems) for atrial natriuretic peptide (Nppa), brain natriuretic peptide (Nppb), β-myosin heavy chain (Myh7), and β-actin (Actb) and analyzed according to the ΔΔCT method.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Explanted hearts were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned at 5 μm in the coronal plane, and stained with either hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Masson’s Trichrome. Immunohistochemical labeling of cMyBP-C was performed using polyclonal antibodies against cMyBP-C (1:400 dilution) and secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa 647 (Invitrogen).

In vivo analysis

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed on anesthetized mice as previously described 32 using a Vevo770 high-resolution imaging system (VisualSonics) equipped with a 30 MHz transducer at 2 or 4 week intervals. TAC was performed on anesthetized mice as previously described 32.

Statistics

All data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were carried out using two-way ANOVA followed by the Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparisons versus WT controls at baseline (time = −1 week). For data collected serially using the same experimental animals, statistical analyses were carried out using two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by the Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparisons versus WT controls at baseline. Normality was confirmed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Generation of tamoxifen-inducible cMyBP-C-cKO mice

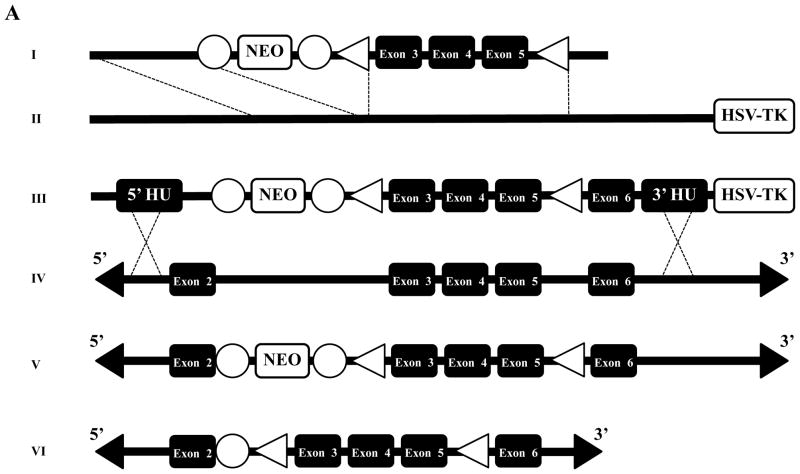

Figure 1A illustrates the conditional gene targeting strategy we used to introduce loxP sites and a FRT-flanked NEO selection cassette into Mybp3. This strategy was designed to induce a frameshift mutation and a premature stop codon following tamoxifen-dependent site-specific recombination of exons 3–5, leading to the generation of a Mybp3 null allele. Following electroporation of the conditional gene targeting vector into SV/129 R1 ES cells 33, southern blot analysis (Figure 1B) identified 37 clones that underwent homologous recombination at the 5′ and 3′ ends, detected by the appearance of a 2.4 kb and 7.5 kb Eco RI band, respectively. Of these, six clones were karyotyped to confirm normal chromosome complement, two of which were microninjected into C57BL/6 blastocysts to produce highly chimeric founders. Subsequent mating of male chimeras with C57BL/6 females produced black and agouti F1 generation mice, the latter of which were genotyped to identify germline transmission of the targeted Mybp3 allele.

Figure 1.

Generation of cMyBP-C-cKO mice. (A) Mybp3 cKO gene targeting strategy, illustrating: (I) mini-targeting vector, (II) retrieval vector, (III) targeting vector, and (IV) exons 2–6 of Mybp3. Homologous recombination (dotted lines) between the endogenous Mybp3 locus and the targeting vector resulted in a floxed chromosome carrying loxP flanked exons 3–5 and a FRT flanked neomycin (NEO) cassette (V). The floxed allele after FLPe excision of NEO is shown in (VI). Exons are represented by black boxes. Open boxes represent positive (NEO) and negative (herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase, HSV-TK) selection cassettes. Open triangles represent loxP sites. Open circles represent FRT sites. (B) Southern blot of genomic DNA from targeted and untargeted embryonic stem cells. EcoRI-digested DNA was probed with a 32P-labed 5′ probe. The WT allele is detected as a 9.2 kb fragment and the targeted allele as a 2.4 kb fragment. Correct targeting was detected as a 7.5 kb fragment in addition to the native 9.2 EcoRI band. (C) PCR genotyping strategy used to generate cMyBP-C-cKO mice. Shown here are PCR products amplified from genomic DNA isolated from Mybp3fl-NEO/fl-NEO, Mybp3fl/+ FLPeR+/−, Mybp3fl/fl, Mybp3fl/+ α-MyHC-MerCreMer+/−, and Mybp3fl/fl α-MyHC-MerCreMer+/− mice.

Figure 1C shows the PCR genotyping strategy used to generate cMyBP-C-cKO mice (Mybp3fl/fl α-MyHC-MerCreMer+/−). F2 generation Mybp3fl-NEO/fl-NEO mice were crossed with FLPeR+/+ mice 30 expressing an enhanced version of FLP recombinase (FLPe) to remove the FRT-flanked NEO selection cassette in vivo, yielding a floxed Mybp3 transgene that was distinguishable from WT Mybp3 by ~100 bp (corresponding to the 2 loxP sequences flanking exons 3–5 and the residual FRT sequence in intron 2). Appropriate breeding of Mybp3fl/+ FLPeR+/− mice generated Mybp3fl/fl mice lacking FLPe recombinase, the latter of which were crossed with α-MyHC-MerCreMer+/+ mice 31 to confer temporal and tissue-specific regulation of the floxed Mybp3 allele. The resulting Mybp3fl/+ α-MyHC-MerCreMer+/− mice were later bred back to Mybp3fl/fl mice to produce Mybp3fl/fl α-MyHC-MerCreMer+/− mice, i.e. cMyBP-C-cKO mice. These mice appeared healthy, produced normal-sized litters, and were indistinguishable from Mybp3fl/fl, Mybp3fl/+, and Mybp3fl/+ α-MyHC-MerCreMer+/− littermates.

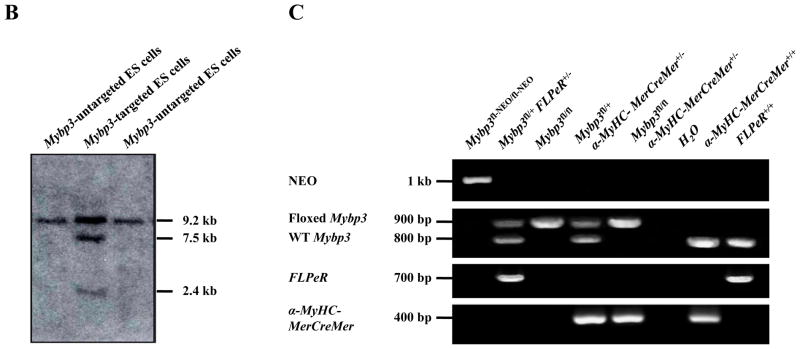

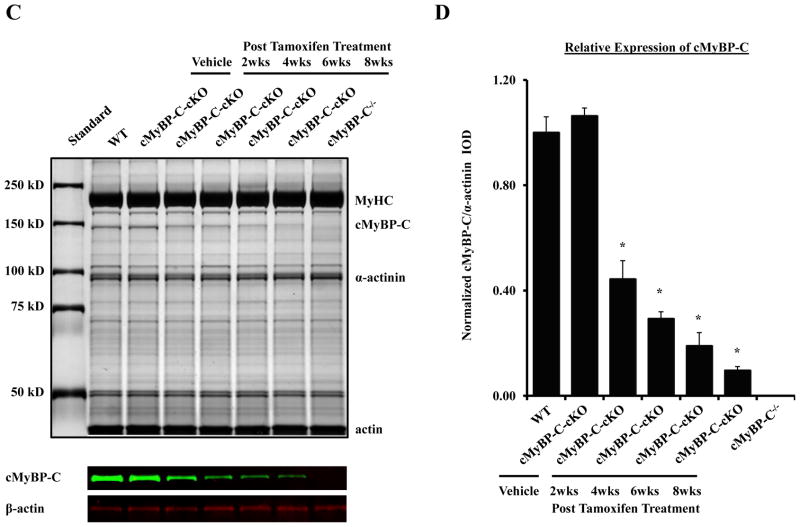

Conditional knock-down of cMyBP-C in adult murine myocardium

cMyBP-C-cKO mice were injected with tamoxifen to activate MerCreMer recombinase activity to induce knock-down of cMyBP-C. Figure 2A shows a representative agarose gel demonstrating tamoxifen-dependent site-specific recombination of exons 3–5 from the floxed Mybp3 transgene. In the absence of tamoxifen, a single ~1 kb PCR product corresponding to the unrecombined floxed Mybp3 transgene was amplified from cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium treated with vehicle only, indicating little or no leakage of MerCreMer activity. In contrast, a prominent ~200 bp PCR product was amplified from tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium corresponding to the removal of exons 3–5. Consistent with previously published studies 31, a faint ~1 kb band was still detected in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium.

Figure 2.

Conditional knock-down of cMyBP-C. (A) Agarose gel showing PCR analysis of MerCreMer-mediated recombination in cMyBP-C-cKO mice. 1 kb band corresponds to the unrecombined floxed Mybp3 transgene. 200 bp band corresponds to the resulting Mybp3 transgene following removal of exons 3–5. (B) Confocal images of cardiac sections obtained from WT, cMyBP-C−/−, and cMyBP-C-cKO mice treated with either vehicle or tamoxifen after 8 weeks. Sections were immunolabeled with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against cMyBP-C, detected with goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa 647 (red), and counterstained with DAPI (blue). (C) Representative SDS-PAGE gel of myofibrillar proteins isolated from WT, cMyBP-C−/−, and cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium treated with either vehicle or tamoxifen. (D) Densitometric analysis of cMyBP-C expression relative to α-actinin and normalized to WT values in WT (n = 6), cMyBP-C−/− (n = 6), and cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium treated with either vehicle (n = 6) or tamoxifen (n = 6). Values are means ± SEM. * indicates statistical significance compared to WT mice at baseline.

To assess the expression of cMyBP-C at the myofilament level following tamoxifen-dependent activation of MerCreMer activity in cMyBP-cKO mice, standard SDS-PAGE and western blot techniques were used to quantify the loss of cMyBP-C. Figure 2C shows a representative silver-stained SDS-PAGE gel of myofibrillar proteins isolated from WT, cMyBP-C−/−, and cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium treated with either vehicle or tamoxifen. cMyBP-C expression in non-induced cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium did not differ significantly from WT myocardium in agreement with the tamoxifen-dependent activity of MerCreMer recombinase shown in Figure 2A. In contrast, cMyBP-C levels in cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium decreased ~50% in the first two weeks following tamoxifen treatment and continued to decline thereafter until less than 10% of total cMyBP-C remained after 8 weeks post-induction. This was confirmed by western blot analysis (Figure 2C) and fluorescent immunohistochemical labeling of cMyBP-C in cardiac tissue sections collected 8 weeks following tamoxifen treatment, demonstrating near-complete knock-down of cMyBP-C in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium (Figure 2B). No detectable levels of cMyBP-C were observed in cMyBP-C−/− myocardium by either SDS-PAGE (Figure 2C), western blot (Figure 2C), or immunohistochemistry (Figure 2B), as previously published 19.

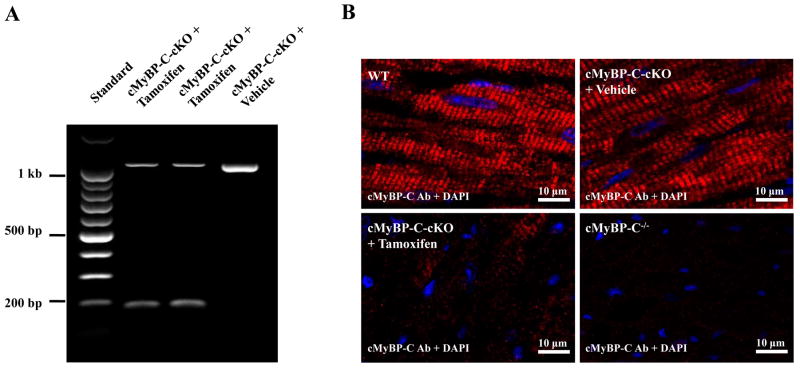

Left ventricular function in response to loss of cMyBP-C in adult cMyBP-C-cKO mice

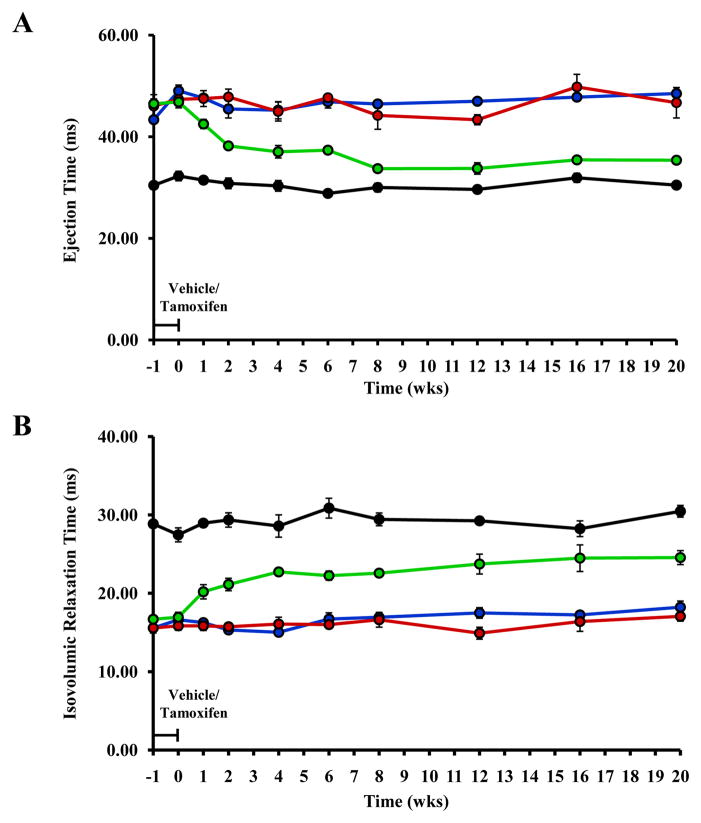

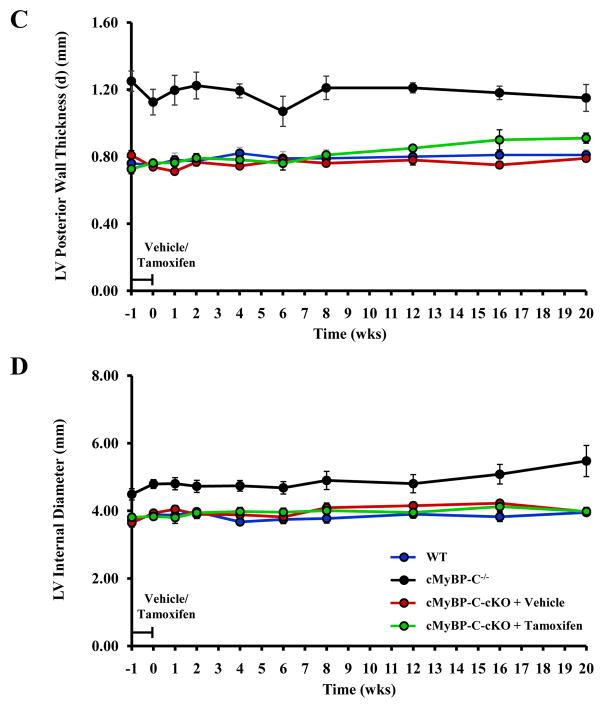

To assess the early changes in cardiac function that occur in vivo following the removal of cMyBP-C, serial transthoracic echocardiograms were collected in cMyBP-C-cKO mice before and after tamoxifen treatment and compared to age-matched WT, cMyBP-C−/−, vehicle-treated cMyBP-C-cKO, and tamoxifen-treated Mybp3fl/fl and α-MyHC-MerCreMer+/− controls. Summary data for all echocardiographic measurements are listed in Tables S1–S5 in the online data supplement. Prior to tamoxifen administration (t = −1 week), LV function in cMyBP-C-cKO mice was not statistically different from WT mice. Importantly, heart rates and body weights were not significantly different among all genotypes studied. Consistent with previously published results 19, 32, ejection time (ET, Figure 3A) and endocardial fractional shortening (EnFS, Figure 4) were significantly reduced in cMyBP-C−/− mice compared to WT mice, while isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT, Figure 3B) was significantly longer.

Figure 3.

Analysis of LV structure and function. Time course analysis of ET (A), IVRT (B), LVPWd (C), and LVIDd (D) collected from the same experimental animals in WT (n = 5), cMyBP-C−/− (n = 5), and cMyBP-cKO mice treated with either vehicle (n = 6) or tamoxifen (n = 8). ET and IVRT were measured from pulsed-wave Doppler tracings of aortic outflow and mitral inflow collected in the suprasternal and apical 4-chamber views on 2-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography. Tamoxifen treatment designated by the horizontal bar. Values are means ± SEM.

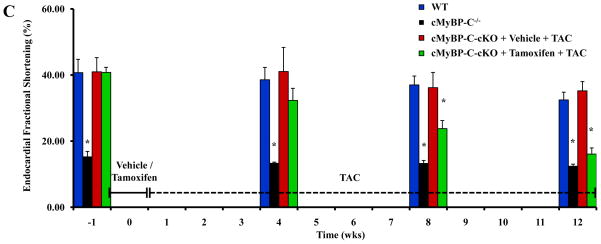

Figure 4.

Analysis of systolic contractile function. Endocardial fractional shortening (EnFS) was assessed longitudinally in the same experimental animals in WT (n = 5), cMyBP-C−/− (n = 5), and cMyBP-cKO mice treated with either vehicle (n = 6) or tamoxifen (n = 8). EnFS was calculated using the following equation: EnFS = (LVIDd-LVIDs)/LVIDd × 100. Echocardiographic measurements of LVIDd and LVIDs were collected at the level of the papillary muscle in M-Mode. Values are means ± SEM. * indicates statistical significance compared to WT mice at baseline. P < 0.05.

In tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice, ET shortened concurrently with the loss of cMyBP-C (Figure 3A). This abbreviation of ET became progressively shorter until after 8 weeks when little or no cMyBP-C remained in the sarcomere. In a similar manner, IVRT also increased concomitantly in cMyBP-C-cKO mice following tamoxifen treatment (Figure 3B), although IVRT continued to increase 8 weeks post-induction, albeit to a lesser degree. Neither ET nor IVRT in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice reached the values reported in cMyBP-C−/− mice. Interestingly, EnFS was largely preserved in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice in comparison to WT mice despite near complete knock-out of cMyBP-C (Figure 4). No statistically significant effects of vehicle were observed in cMyBP-C-cKO mice. Similarly, no statistically significant effects of tamoxifen were observed in Mybp3fl/fl or α-MyHC-MerCreMer+/− controls compared to age-matched WT mice (Figures S1 and S2, online data supplement).

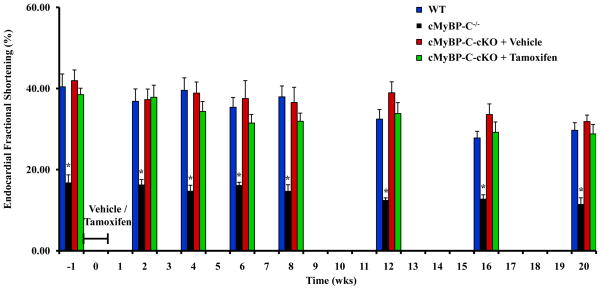

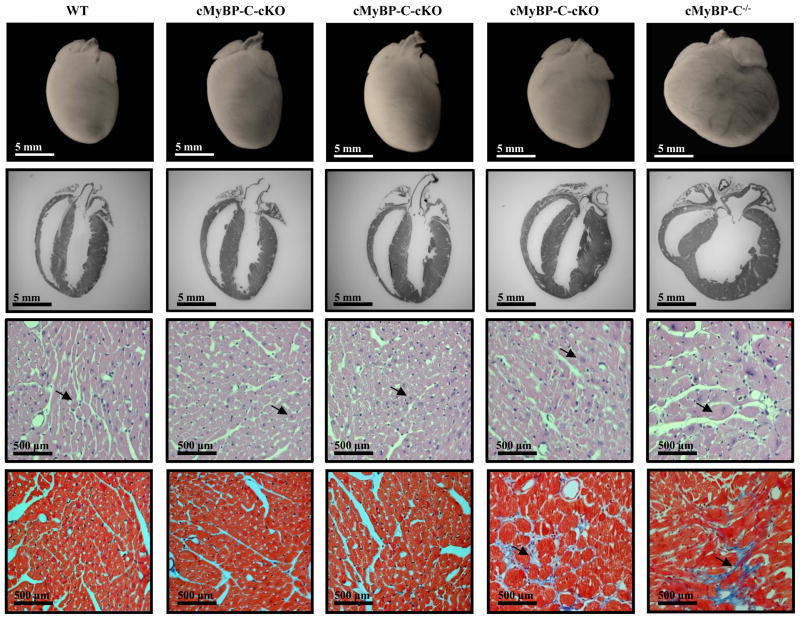

Loss of cMyBP-C in adult murine myocardium and cardiac remodeling

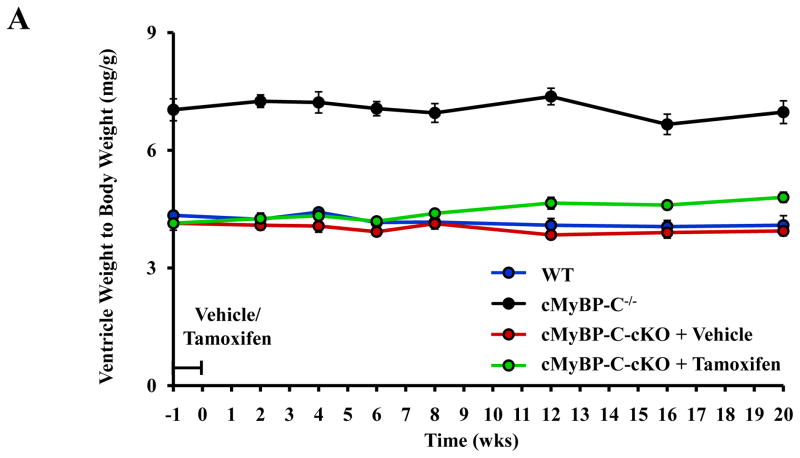

To study the development and progression of structural and morphological phenotypes due to the loss of cMyBP-C, gross and histological analyses were performed on formalin-fixed hearts obtained from tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice (Figure 5). Interestingly, despite near-complete ablation of cMyBP-C, no significant difference in gross cardiac morphology was evident 8 weeks following tamoxifen treatment in cMyBP-C-cKO mice when compared to WT mice. Consistent with these results, ventricle weight to body weight (VW/BW) ratios were not statistically different among WT and cMyBP-C-cKO mice treated with either vehicle or tamoxifen up to 8 weeks following treatment (Figure 6A). However, by 20 weeks post-induction, myocyte hypertrophy was discernible via histology (Figure 5), and a significant increase in VW/BW ratio was measured in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice (Figure 6A). In addition, histopathological analysis of cardiac tissue sections stained with Masson’s Trichrome revealed a slightly increased incidence of focal and diffuse interstitial fibrosis in cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium 20 weeks following tamoxifen treatment (Figure 5), although the extent and location of fibrosis was highly variable. In contrast to WT and cMyBP-C-cKO mice, cMyBP-C−/− mice demonstrated marked dilation of the LV, resulting in a globular morphology on gross examination (Figure 5). Moreover, coronal sections of cMyBP-C−/− hearts stained with H&E demonstrated LV hypertrophy and chamber dilation, while staining with Masson’s Trichrome showed similar areas of diffuse and focal interstitial fibrosis in agreement with previous results 19.

Figure 5.

Cardiac morphometry and histology in WT, cMyBP-C−/−, and cMyBP-C-cKO mice treated with either vehicle or tamoxifen (8 or 20 weeks post-induction). 1st row shows representative images (10×) of formalin-fixed hearts. 2nd row shows representative H&E-stained sagittal sections (10×) of paraffin-embedded cardiac tissue. 3rd row shows representative high magnification (400×) photomicrographs of H&E-stained sections. 4th row shows high magnification (400×) photomicrographs of Masson’s Trichrome-stained sections, demonstrating a focus of fibrosis in cMyBP-C−/− and tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice 20 weeks post-induction.

Figure 6.

Analysis of cardiac hypertrophy. (A) Time course analysis of ventricle weight to body weight ratios measured in WT (n = 12), cMyBP-C−/− (n = 12), and cMyBP-cKO mice treated with either vehicle (n = 11) or tamoxifen (n = 11). Tamoxifen treatment designated by the horizontal bar. Values are means ± SEM. (B) Analysis of hypertrophy-associated gene expression in WT (n = 6), cMyBP-C−/− (n = 6), and cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium 8 or 20 weeks following vehicle (n = 6) or tamoxifen treatment (n = 6). Values are means ± SEM. * indicates statistical significance compared to WT mice at baseline . P < 0.05.

Changes in cardiac structure following the removal of cMyBP-C in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice were also assessed via M-mode echocardiography to measure and quantify differences in LV chamber and wall dimensions. Consistent with morphometric data presented above, no statistically significant differences in LV posterior wall thickness in diastole (LVPWd) or LV internal dimension in diastole (LVIDd) were measured in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice up to 8 weeks post-induction compared to WT mice (Figure 3C and 3D). However, LVPWd was significantly greater after 20 weeks in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice (Figure 3C). Interestingly, no significant changes in LVIDd were measured in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice 20 weeks following tamoxifen treatment (Figure 3D). In contrast, LVIDd and LVPWd were significantly increased in cMyBP-C−/− mice at all time points, in agreement with previous results 19, 32.

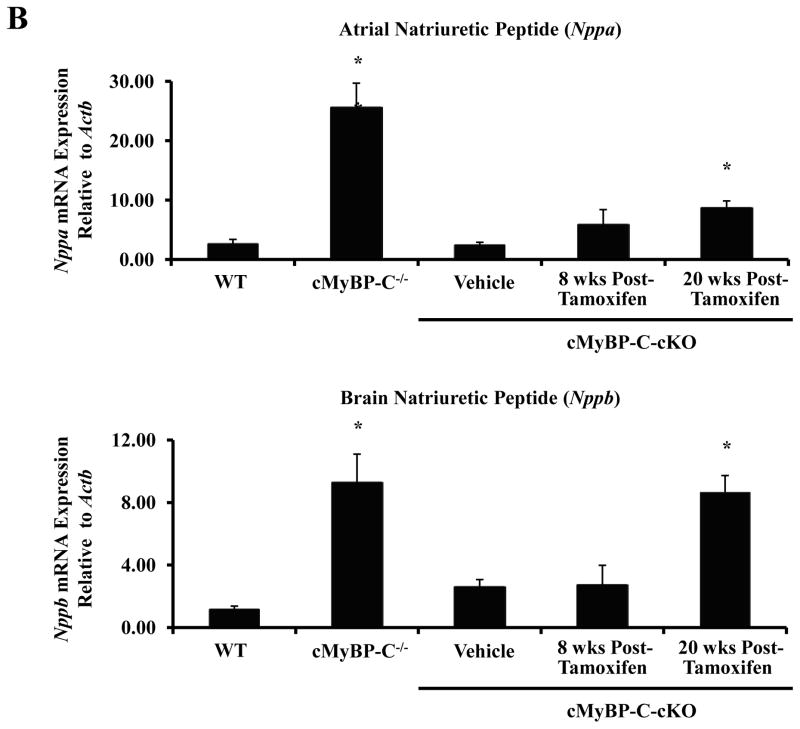

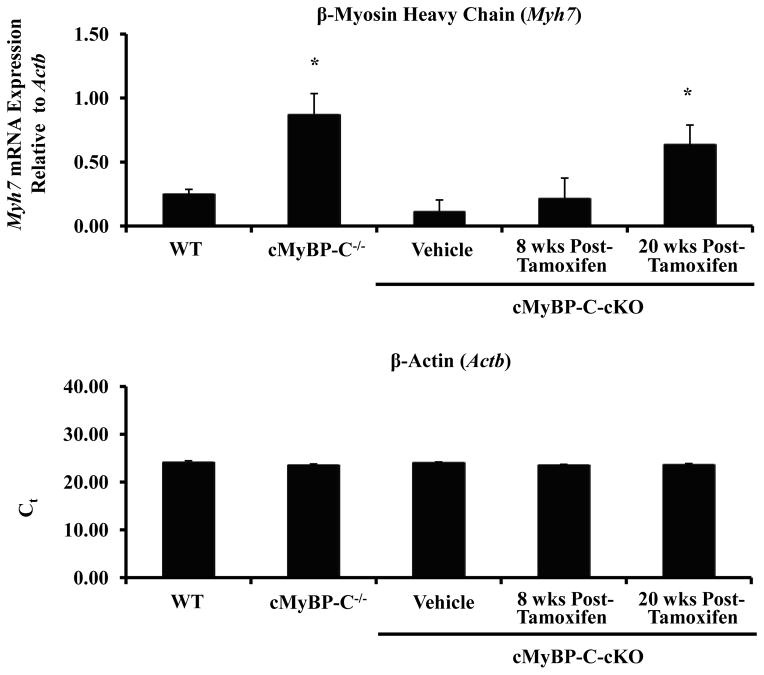

Molecular markers of hypertrophy in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium

To determine whether the expression of hypertrophy-associated genes in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium were evident even in the absence of cardiac hypertrophy 8 weeks post-tamoxifen induction, mRNA levels of Nppa, Nppb, and Myh7 were quantified by real-time qPCR and compared to WT, cMyBP-C−/−, and vehicle-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice (Figure 6B). No significant differences were observed between WT and cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium treated with either vehicle or tamoxifen. However, it should be noted that an increasing trend in the mRNA expression of Nppa and Myh7 was noted in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO myocardium. In contrast, Nppa, Nppb, and Myh7 mRNA levels were all dramatically elevated in cMyBP-C−/− myocardium as previously reported 19. By 20 weeks post-tamoxifen induction, however, mRNA levels of Nppa, Nppb, and Myh7 were all statistically elevated in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-CcKO mice in comparison to WT mice, consistent with the initial development of myocardial hypertrophy.

Effects of pressure-overload in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice

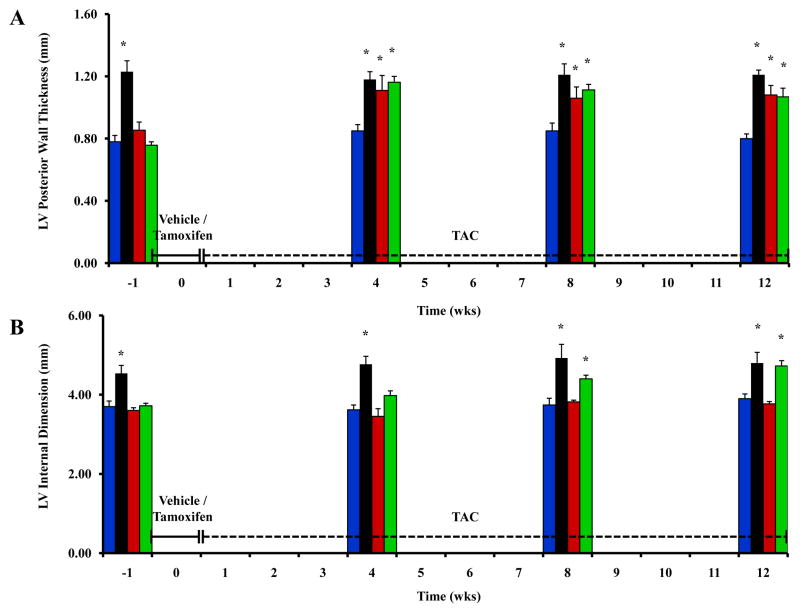

To investigate the phenotypic effects of cMyBP-C knock-down in the context of hemodynamic stress, tamoxifen- and vehicle-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice were subjected to pressure-overload induced by TAC for a period of up to 12 weeks. Both tamoxifen- and vehicle-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice developed LV hypertrophy comparable to that measured in cMyBP-C−/− mice after 4 weeks of TAC (Figure 7A). However, LV chamber dilation only developed in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice after 8 weeks of TAC (Figure 7B). With respect to cardiac function, EnFS was largely preserved in vehicle-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice after TAC (Figure 7C). In contrast, EnFS progressively declined in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice following TAC until LV performance was comparable to cMyBP-C−/− mice after 12 weeks. Importantly, tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice subjected to TAC also exhibited prolonged IVRT and abbreviated ET compared to WT mice. No statistically significant differences in ET or IVRT were detected in Mybp3fl/fl or α-MyHC-MerCreMer+/− experimental controls treated with tamoxifen and subjected to TAC in comparison to WT mice (Figure S3, online data supplement).

Figure 7.

Effect of TAC on cardiac structure and function in cMyBP-C-cKO mice. Time course analysis of LVPWd (A), LVIDd (B), and LV EnFS (C) collected from the same experimental animals in WT (n = 5), cMyBP-C−/− (n = 5), and cMyBP-cKO mice subjected to TAC in addition to treatment with either vehicle (n = 6) or tamoxifen (n = 12). Tamoxifen treatment designated by the horizontal bar. TAC designated by the dashed horizontal bar. Values are means ± SEM. * indicates statistical significance compared to WT mice at baseline. P < 0.05.

With respect to histopathology, cMyBP-C-cKO mice treated with vehicle and tamoxifen both developed myocyte hypertrophy in response to TAC. Likewise, Mybp3fl/fl and α-MyHC-MerCreMer+/− experimental controls treated with tamoxifen and subjected to TAC also developed myocyte hypertrophy (Figure S4, online data supplement). However, only tamoxifen treated-cMyBP-C-cKO mice developed myocyte disarray and myocardial fibrosis 12 weeks following TAC.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a cMyBP-C-cKO mouse model expressing floxed Mybp3 alleles and a tamoxifen-dependent MerCreMer recombinase under the transcriptional control of the α-MyHC promoter 31. Using a conditional knock-out approach to acutely terminate the expression of cMyBP-C in adult myocardium, we determined and interrelated the time course of cMyBP-C knock-down with the onset and development of structural and functional phenotypes, thereby allowing us to differentiate the primary effects of removing cMyBP-C from the secondary effects of compensatory mechanisms (e.g., ventricular remodeling) on cardiac function in vivo. Based on gross morphometric, histologic, and echocardiographic data, we found that cardiac dysfunction preceded the development of LV hypertrophy in cMyBP-C-cKO mice following the removal of cMyBP-C. More specifically, loss of cMyBP-C resulted in concurrent shortening of ET and prolongation of IVRT prior to the onset of cardiac remodeling that was commensurate with the degree of cMyBP-C knock-down, implicating a prominent role for cMyBP-C in regulating the period of cardiac systole and diastole. Interestingly, subsequent development of LV hypertrophy after near-complete ablation of cMyBP-C in cMyBP-C-cKO mice did not have an additional effect on ET, while IVRT continued to increase in parallel with the development of cardiac hypertrophy. These results indicate that truncation of ET and prolongation of IVRT in cMyBP-C deficient mice occurs primarily in response to the removal of cMyBP-C, although IVRT increases further in response to LV hypertrophy.

Our finding that cardiac dysfunction preceded the onset of cardiac remodeling in this study is consistent with other mouse models of HCM harboring either α-MyHC 27 or cardiac troponin T mutations 28. Interestingly, this dissociation of structural and functional phenotypes in response to the removal of cMyBP-C in cMyBP-C-cKO mice continued until cMyBP-C knock-out was nearly complete, indicating that adult murine myocardium tolerates considerable reductions in the expression of cMyBP-C without immediately undergoing significant cardiac remodeling. Despite near-complete ablation of cMyBP-C in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice, however, only mild cardiac hypertrophy developed in contrast to the marked LV hypertrophy and chamber dilation present in cMyBP-C−/− 19, 20 and cMyBP-Ct/t mice 21 . Moreover, near ablation of cMyBP-C in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice did not recapitulate the severe systolic dysfunction previously demonstrated in cMyBP-C−/− 19, 20, 32 and cMyBP-Ct/t mice 21, i.e., EnFS was largely preserved in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO even when less than 10% of total cMyBP-C remained. This apparent lack of effect of cMyBP-C knock-down on EnFS is perhaps surprising, given the significant shortening of ET in these mice, which in turn, might be predicted to limit EnFS. A concomitant acceleration of contraction kinetics due to the loss of cMyBP-C, however, could potentially account for the preservation of EnFS in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice. Indeed, considerable evidence from mechanical measurements performed in cMyBP-C−/− skinned myocardium suggests that cross-bridge cycling kinetics are accelerated in the absence of cMyBP-C 22, 23, which would in turn speed the rate of pressure development in the intact heart. Thus, loss of systolic contractile function in cMyBP-C−/− and cMyBP-Ct/t mice most likely involves modifying factors activated subsequent to the ablation of cMyBP-C. Together, these results demonstrate that acute loss of cMyBP-C in adult mice per se is insufficient to cause the expression of DCM or HCM-associated dilation previously reported in cMyBP-Ct/t 21 and cMyBP-C−/− mice 19, 20, respectively.

To investigate whether additional stressors could induce the expression of HCM-associated dilation in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice, TAC was introduced to increase hemodynamic workload. Interestingly, loss of systolic contractile function was precipitated in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice subjected to TAC. In addition, these mice developed progressive LV chamber dilation and further hypertrophy of the LV wall, recapitulating the dilated HCM phenotype previously reported in cMyBP-C−/− 19, 20. Importantly, these phenotypes were largely absent in vehicle-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice subjected to TAC (with the exception of hypertrophy). Together, these results indicate that both knock-out of cMyBP-C and additional precipitating factor(s) are needed to drive the expression of HCM-associated dilation in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice. Consistent with this idea, loss of systolic contractile function in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice subjected to TAC was not statistically significant until knock-out of cMyBP-C was nearly complete. Interestingly, this effect of cMyBP-C knock-down on contractile function in tamoxifen-treated cMyBP-C-cKO mice coincided with the development of LV dilation, suggesting that increases in LV chamber dilation may exacerbate the functional effects of cMyBP-C ablation on systolic function. Indeed, increases in the diameter of the LV would be expected to increase wall stress according to the Law of LaPlace, which could in turn limit EnFS 26. While increased afterload induced by TAC might also be expected to diminish EnFS, this consideration is not applicable in cMyBP-C−/− mice, since hemodynamic load in these mice is not significantly different from WT mice. Taken together, these results suggest that the development of LV dilation in cMyBP-C−/− mice contributes to the pathogenesis of depressed cardiac function (beyond effects due to ablation of cMyBP-C).

The mechanism(s) underlying the development of LV dilation in cMyBP-C−/− and cMyBP-Ct/t mice, however, remain largely unknown. Previous studies have suggested a gene dosage effect 19–21, 34, since cMyBP-C+/− and cMyBP-Ct/+ mice exhibited milder or unaltered phenotypes in comparison to their respective homozygous counterparts. Results presented in this study suggest that additional disease-modifying factor(s) are required to precipitate the expression of HCM-associated dilation or DCM, since near-to-complete loss of cMyBP-C in adult murine myocardium was insufficient to cause ventricular dilation and systolic dysfunction per se. An important difference between the cMyBP-C-cKO mice in this study and the cMyBP-C−/− and cMyBP-Ct/t mice of previous studies was the timing of cMyBP-C knock-out, i.e. adult vs. embryonic knock-out. This distinction may provide valuable insights into potential mechanism(s) underlying the development of LV dilation and systolic dysfunction in cMyBP-C−/− and cMyBP-Ct/t mice versus the development of HCM in cMyBP-C-cKO mice. There are several fundamental differences between mature myocardium and developing myocardium in utero, which in turn may modulate the effects that loss of cMyBP-C may have on cardiac structure and function. For example, the predominate isoform of MyHC expressed during murine cardiac development is β-MyHC, which later switches to the α-MyHC isoform during early neonatal development and becomes the predominate isoform in adult myocardium 35. Replacing α-MyHC with predominately β-MyHC in cMyBP-Ct/t mice 36 has previously been shown to exacerbate the expression of the morphological phenotype associated with cMyBP-Ct/t mice 21, suggesting that the functional effects of removing cMyBP-C are more severe on a β-MyHC background compared to a predominately α-MyHC background. There is increasing evidence to suggest that introducing HCM mutations onto an α-MyHC or β-MyHC background may have disparate effects on contractile function 37. Indeed, the slower turnover kinetics of β-MyHC 38 could result in a greater reduction in peak twitch force production following ablation of cMyBP-C. These studies raise the possibility in mice that loss of cMyBP-C requires a predominately β-MyHC background (at least initially) in order to lead to the development of HCM-associated dilation or DCM. Along this same line of reasoning, expression of the α-MyHC isoform may be cardioprotective with respect to the deleterious functional effects of removing cMyBP-C in murine myocardium

In summary, tamoxifen-induced loss of cMyBP-C in cMyBP-C-cKO mice causes functional derangements in ET and IVRT that occur prior to the onset of compensatory cardiac remodeling, supporting the idea that cMyBP-C plays important roles in regulating normal systolic and diastolic function. In addition, we provide novel evidence suggesting that LV dilation may contribute to the depression in cardiac function previously demonstrated in cMyBP-C−/− 19,20 and cMyBP-Ct/t 21 mice, while LV hypertrophy only contributes to the prolongation of IVRT. These results underscore the role of additional factors and/or stressors in governing the clinical expression of cMyBP-C-associated cardiomyopathy and predict the clinical utility of interventions that prevent or delay the onset of cardiac remodeling or reverse the progression of LV hypertrophy to LV chamber dilation.

Supplementary Material

CLINCAL PERSPECTIVE.

Mutations in the gene encoding cardiac myosin binding protein-C (cMyBP-C) are common causes of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and can also lead to HCM-associated dilation. This primary disease of the myocardium affects a wide range of patient age groups, accounts for the majority of cardiac genetic diseases, and leads to significant morbidity and mortality associated with the development of heart failure, ventricular and atrial arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, and sudden cardiac death. Nevertheless, little is known regarding the mechanisms underlying the development of cMyBP-C-associated HCM, although deficiencies in cMyBP-C are thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of this disease in many cases. Herein, we investigate the onset, progression, and saturation of structural and functional phenotypes due to the removal of cMyBP-C and assess whether loss of cMyBP-C per se is sufficient to cause the development of HCM-associated dilation. Using adult cMyBP-C conditional knock-out mice, we show that acute loss of cMyBP-C affects the duration of cardiac systole and diastole and contributes to the development of diastolic dysfunction, all of which occurs prior to the onset of cardiac hypertrophy. Moreover, we show that near-complete ablation of cMyBP-C is insufficient to cause HCM-associated dilation in adult mice, whereas imposing additional stresses such as increased afterload is sufficient to recapitulate the phenotype. These results help define the gradual changes that precede and progress with the clinical expression of cMyBP-C-associated cardiomyopathy and identify potential avenues in which to prevent, delay, or reverse the progression of this disease.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Dr. Timothy Hacker (UW Cardiovascular Research Center) for echocardiography services; Dr. Ruth Sullivan and Beth Gray (UW Research Animal Resource Center) for histology services; Andy Pieper, Maggie Maes, Becky Plutz, Anne Dronen, Jasmine Giles, Jennifer Wachholz, and Dr. Matthew Locher for technical assistance; and Dr. Willem (Toy) Delange for fruitful discussions.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to R. L. Moss (R37-HL082900 and PO1-HL094291) and P. P. Chen (F30-HL093990) and a core grant to the Waisman Center from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P30-HD03352).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Maron BJ, Shirani J, Poliac LC, Mathenge R, Roberts WC, Mueller FO. Sudden death in young competitive athletes. Clinical, demographic, and pathological profiles. JAMA. 1996;276:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maron BJ, Gardin JM, Flack JM, Gidding SS, Kurosaki TT, Bild DE. Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a general population of young adults. Echocardiographic analysis of 4111 subjects in the CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults. Circulation. 1995;92:785–789. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maron BJ, Henry WL, Clark CE, Redwood DR, Roberts WC, Epstein SE. Asymetric septal hypertrophy in childhood. Circulation. 1976;53:9–19. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.53.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niimura H, Patton KK, McKenna WJ, Soults J, Maron BJ, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Sarcomere protein gene mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy of the elderly. Circulation. 2002;105:446–451. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richard P, Charron P, Carrier L, Ledeuil C, Cheav T, Pichereau C, Benaiche A, Isnard R, Dubourg O, Burban M, Gueffet JP, Millaire A, Desnos M, Schwartz K, Hainque B, Komajda M. EUROGENE Heart Failure Project. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: distribution of disease genes, spectrum of mutations, and implications for a molecular diagnosis strategy. Circulation. 2003;107:2227–2232. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000066323.15244.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Driest SL, Ommen SR, Tajik AJ, Gersh BJ, Ackerman MJ. Sarcomeric genotyping in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:463–469. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrier L, Bonne G, Bahrend E, Yu B, Richard P, Niel F, Hainque B, Cruaud C, Gary F, Labeit S, Bouhour JB, Dubourg O, Desnos M, Hagège AA, Trent RJ, Komajda M, Fiszman M, Schwartz K. Organization and sequence of human cardiac myosin binding protein C gene (MYBPC3) and identification of mutations predicted to produce truncated proteins in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 1997;80:427–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert R, Kelly MG, Mikawa T, Fischman DA. The carboxyl terminus of myosin binding protein C (MyBP-C, C-protein) specifies incorporation into the A-band of striated muscle. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:101–111. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flavigny J, Souchet M, Sebillon P, Berrebi-Bertrand I, Hainque B, Mallet A, Bril A, Schwartz K, Carrier L. COOH-terminal truncated cardiac myosin-binding protein C mutants resulting from familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations exhibit altered expression and/or incorporation in fetal rat cardiomyocytes. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:443–456. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarikas A, Carrier L, Schenke C, Doll D, Flavigny J, Lindenberg KS, Eschenhagen T, Zolk O. Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by truncated cardiac myosin binding protein C mutants. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marston S, Copeland O, Jacques A, Livesey K, Tsang V, McKenna WJ, Jalilzadeh S, Carballo S, Redwood C, Watkins H. Evidence from human myectomy samples that MYBPC3 mutations cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy through haploinsufficiency. Circ Res. 2009;105:219–222. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.202440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rottbauer W, Gautel M, Zehelein J, Labeit S, Franz WM, Fischer C, Vollrath B, Mall G, Dietz R, Kübler W, Katus HA. Novel splice donor site mutation in the cardiac myosin-binding protein-C gene in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Characterization of cardiac transcript and protein. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:475–482. doi: 10.1172/JCI119555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Dijk SJ, Dooijes D, dos Remedios C, Michels M, Lamers JM, Winegrad S, Schlossarek S, Carrier L, ten Cate FJ, Stienen GJ, van der Velden J. Cardiac myosin-binding protein C mutations and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: haploinsufficiency, deranged phosphorylation, and cardiomyocyte dysfunction. Circulation. 2009;119:1473–1483. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.838672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nanni L, Pieroni M, Chimenti C, Simionati B, Zimbello R, Maseri A, Frustaci A, Lanfranchi G. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: two homozygous cases with “typical” hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and three new mutations in cases with progression to dilated cardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;309:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lekanne Deprez RH, Muurling-Vlietman JJ, Hruda J, Baars MJ, Wijnaendts LC, Stolte-Dijkstra I, Alders M, van Hagen JM. Two cases of severe neonatal hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by compound heterozygous mutations in the MYBPC3 gene. J Med Genet. 2006;43:829–832. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.040329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konno T, Shimizu M, Ino H, Matsuyama T, Yamaguchi M, Terai H, Hayashi K, Mabuchi T, Kiyama M, Sakata K, Hayashi T, Inoue M, Kaneda T, Mabuchi H. A novel missense mutation in the myosin binding protein-C gene is responsible for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular dysfunction and dilation in elderly patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:781–786. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02957-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehlermann P, Weichenhan D, Zehelein J, Steen H, Pribe R, Zeller R, Lehrke S, Zugck C, Ivandic BT, Katus HA. Adverse events in families with hypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathy and mutations in the MYBPC3 gene. BMC Med Genet. 2008;9:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-9-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hershberger RE, Norton N, Morales A, Li D, Siegfried JD, Gonzalez-Quintana J. Coding sequence rare variants identified in MYBPC3, MYH6, TPM1, TNNC1, and TNNI3 from 312 patients with familial or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:155–161. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.912345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris SP, Bartley CR, Hacker TA, McDonald KS, Douglas PS, Greaser ML, Powers PA, Moss RL. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in cardiac myosin binding protein-C knockout mice. Circ Res. 2002;90:594–601. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000012222.70819.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrier L, Knoll R, Vignier N, Keller DI, Bausero P, Prudhon B, Isnard R, Ambroisine ML, Fiszman M, Ross J, Jr, Schwartz K, Chien KR. Asymmetric septal hypertrophy in heterozygous cMyBP-C null mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:293–304. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McConnell BK, Jones KA, Fatkin D, Arroyo LH, Lee RT, Aristizabal O, Turnbull DH, Georgakopoulos D, Kass D, Bond M, Niimura H, Schoen FJ, Conner D, Fischman DA, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. Dilated cardiomyopathy in homozygous myosin-binding protein-C mutant mice. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1235–1244. doi: 10.1172/JCI7377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stelzer JE, Dunning SB, Moss RL. Ablation of cardiac myosin-binding protein-C accelerates stretch activation in murine skinned myocardium. Circ Res. 2006;98:1212–1218. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000219863.94390.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korte FS, McDonald KS, Harris SP, Moss RL. Loaded shortening, power output, and rate of force redevelopment are increased with knockout of cardiac myosin binding protein-C. Circ Res. 2003;93:752–758. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000096363.85588.9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cazorla O, Szilagyi S, Vignier N, Salazar G, Kramer E, Vassort G, Carrier L, Lacampagne A. Length and protein kinase A modulations of myocytes in cardiac myosin binding protein C-deficient mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:370–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grossman W, McLaurin LP, Moos SP, Stefadouros M, Young DT. Wall thickness and diastolic properties of the left ventricle. Circulation. 1974;49:129–135. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.49.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunther S, Grossman W. Determinants of ventricular function in pressure-overload hypertrophy in man. Circulation. 1979;59:679–688. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.59.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Georgakopoulos D, Christe ME, Giewat M, Seidman CM, Seidman JG, Kass DA. The pathogenesis of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: early and evolving effects from an alpha-cardiac myosin heavy chain missense mutation. Nat Med. 1999;5:327–330. doi: 10.1038/6549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller T, Szczesna D, Housmans PR, Zhao J, de Freitas F, Gomes AV, Culbreath L, McCue J, Wang Y, Xu Y, Kerrick WG, Potter JD. Abnormal contractile function in transgenic mice expressing a familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-linked troponin T (I79N) mutation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3743–3755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006746200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu P, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. A highly efficient recombineering-based method for generating conditional knockout mutations. Genome Res. 2003;13:476–484. doi: 10.1101/gr.749203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farley FW, Soriano P, Steffen LS, Dymecki SM. Widespread recombinase expression using FLPeR (flipper) mice. Genesis. 2000;28:106–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sohal DS, Nghiem M, Crackower MA, Witt SA, Kimball TR, Tymitz KM, Penninger JM, Molkentin JD. Temporally regulated and tissue-specific gene manipulations in the adult and embryonic heart using a tamoxifen-inducible Cre protein. Circ Res. 2001;89:20–25. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.092687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brickson S, Fitzsimons DP, Pereira L, Hacker T, Valdivia H, Moss RL. In vivo left ventricular functional capacity is compromised in cMyBP-C null mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1747–1754. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01037.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagy A, Rossant J, Nagy R, Abramow-Newerly W, Roder JC. Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8424–8428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McConnell BK, Fatkin D, Semsarian C, Jones KA, Georgakopoulos D, Maguire CT, Healey MJ, Mudd JO, Moskowitz IP, Conner DA, Giewat M, Wakimoto H, Berul CI, Schoen FJ, Kass DA, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. Comparison of two murine models of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2001;88:383–389. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Molecular diversity of myofibrillar proteins: gene regulation and functional significance. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:371–423. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadayappan S, Gulick J, Klevitsky R, Lorenz JN, Sargent M, Molkentin JD, Robbins J. Cardiac myosin binding protein-C phosphorylation in a {beta}-myosin heavy chain background. Circulation. 2009;119:1253–1262. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.798983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowey S, Lesko LM, Rovner AS, Hodges AR, White SL, Low RB, Rincon M, Gulick J, Robbins J. Functional effects of the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy R403Q mutation are different in an alpha- or beta-myosin heavy chain backbone. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20579–20589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800554200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Locher MR, Razumova MV, Stelzer JE, Norman HS, Patel JR, Moss RL. Determination of rate constants for turnover of myosin isoforms in rat myocardium: implications for in vivo contractile kinetics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H247–256. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00922.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.