Abstract

Background

Impairments of executive functioning such as set-shifting ability, are seen as core deficits of schizophrenia, and are of interest as candidate intermediate phenotype markers. The Intradimensional/Extradimensional (ID/ED) shift task offers a differentiated assessment of shifting from previously reinforced stimuli as well as shifting from previously reinforced features, and has proven to be sensitive to the impairment seen in patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

We examined ID/ED performance in 147 patients with schizophrenia, 131 of their healthy siblings, and 303 healthy controls. Participants were recruited from local and national sources as volunteers for the Clinical Brain Disorders Branch/National Institute of mental Health “sibling study”.

Results

Nearly all controls (87%) finished the task successfully as did 80% of siblings. In contrast only 54% of patients with schizophrenia were able to complete the task. Despite the apparent similarity of performance across the sibling and healthy comparison group, the two groups differed significantly in terms of the number of stages till failure. This difference, however, was not present at any particular stage or any other measure of performance.

Conclusions

Patients demonstrated robust ID/ED deficits. However, their siblings were minimally impaired, and this impairment did not appear to run in families. These results suggest that impairments on attentional set shifting assessed by ID/ED task are strongly associated with clinical illness, but these impairments are not a promising intermediate phenotype.

Cognitive impairments are attractive intermediate phenotypes for the study of schizophrenia risk genes. There is robust evidence that cognitive impairment is a core feature of the disorder, and it appears likely that the genetic architecture of specific cognitive functions may be simpler than the clinical illness phenotype. Further, there is evidence that the healthy relatives of schizophrenia patients also demonstrate cognitive impairments in many of the same domains observed in ill patients. Specifically, a recent meta-analysis comparing cognitive performance of healthy relatives of schizophrenic patients to that of well controls revealed that, 4 of the 6 largest effect sizes “come from variables having in common executive control functions such as working memory demands, set-shifting, and the inhibition of prepotent responses” (1), suggesting that these aspects of cognitive performance may be particularly useful for genetic studies.

Set shifting is a complex construct. In the cognitive experimental literature this construct is often operationalized in the study of task switching(2, 3). In this approach, subjects need to shift between performing two tasks on the basis of cues. For example, a cue would inform the subject to make a prosaccade to a target location on some trials, while another cue would indicate that an antisacadde is the appropriate responses on others. Performance is typically quantified in terms of error rates on switch as opposed to non-switch trials, or reaction time costs on switch trials relative to non-switch trials. Surprisingly, patients with schizophrenia have not demonstrated reliable deficits in several studies examining task switching (4–7) although further study is needed to establish confidence in these results. In the clinical neuropsychological literature, the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test is considered a measure of set shifting, and there is well-replicated evidence that patients with schizophrenia demonstrate marked impairments on this task. However, studies of WCST performance in well siblings of patients with schizophrenia have produced mixed results (8–11) and the effect sizes seen on the WCST in the Snitz meta-analysis were not among the largest documented in the cognitive literature. In addition, Kremen et al. (12) recently reported no evidence of heritability of WCST performance in a study of monozygotic and dizygotic twins. These converging data suggest that the WCST may not be a robust intermediate phenotype marker despite being sensitive to the impairments observed in patients. The cognitive complexity of the task may enhance sensitivity to diagnostic status because there may be multiple routes to performance failure, while at the same time making it difficult to discern specific genetic effects that impact only some of the cognitive operations involved in the task.

Experimental methods that isolate the different cognitive mechanisms involved in WCST performance may serve to increase power to detect genetic effects. The Intra-dimensional/Extra-Dimensional set-shifting task (Downes et al. (13)) was designed to offer a differentiated assessment of many of the processes involved in the WCST. Like the WCST, the ID/ED task requires the subject to learn which stimulus/response choice is correct through the use of feedback. However, the ID/ ED is simpler than the WCST because only two stimuli are presented in every trial, making the feedback less ambiguous – if one stimulus is incorrect, the other must be correct. Thus, the ID/ED task minimizes the role of rule “discovery” that is a demand of the WCST. Studies Of ID/ED performance have consistently found impairments in patients with chronic schizophrenia at the extradimensional stages (14–16), including patients with preserved IQ, with a smaller numbers of patients failing at the some of the earlier stages implicating deficits in more elementary processes.

In contrast to chronically ill patients, first-episode patients have been shown to be relatively unimpaired on the ID/ED task (17–19). In fact, Joyce et al. (20, 21) and Pantelis et al. (22) have reported that the performance of first episode patients appears to deteriorate over time on the ID/ED task. Further, there is mixed evidence suggesting that illness duration may correlate with ID/ED performance (23) (but see Tyson et al. (16)). These findings raise the possibility that poor performance on this task is a result of illness chronicity and/or treatment effects, but not risk associated influences.

We thought it was potentially informative to examine ID/ED task performance in patients and in their healthy siblings in order to determine if attentional set shifting was a promising intermediate phenotype. In contrast, evidence of intact performance in siblings, coupled with the evidence of relatively intact performance in first episode patients, would suggest that impairments on the ID/ED task reflect “extra-genetic” influences that are associated with the clinical illness.

Method

Subjects

ID/ED task performance data were available from 147 patients, 131 unaffected siblings, and 303 healthy comparison subjects who were volunteers for the Clinical Brain Disorders Branch/National Institute of mental Health “sibling study”. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Mental Health and all subjects provided written informed consent after complete description of the study. All participants (age 18–60 years) were interviewed by a research psychiatrist (blind to group status) using the Structured Clinical Interview from DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID-I) (24) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II) (25). A second, and sometimes third, psychiatrist independently reviewed all diagnostic data. All subjects received a neurological examination, magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain, blood laboratory tests, and review of medical history in order to rule out medical problems that might impact cognitive performance. Participants with alcohol or drug dependence within the last year, or more than a 5-year history of alcohol or drug abuse or dependence were excluded. Comparison subjects and siblings who were diagnosed with a current Axis I or Axis II disorders, a history of psychosis, or a history of serious medical/neurological illness that could affect cognitive function were excluded. Participants were required to be free of a history of learning disability and must have been a fluent English speaker by the age of 5 years old. Participants with WRAT-R reading scores of <70 were excluded in order to exclude subjects with severe developmental compromise. Healthy volunteers had the additional requirement that they not have a first-degree relative with schizophrenia.

Patients had a mean duration of illness of 12.4 (9.47) years. In some cases, siblings or patients were excluded due to one of the medical or psychiatric exclusions, missing CANTAB data, or most often, because siblings did not complete the protocol. Of the 147 patients with available CANTAB data, we were able to examine data from one or more siblings for 60 patients. Our sample of patients included 60 with siblings and 87 without; our sample of siblings consisted of 92 siblings with a proband and 39 without. Exclusion factors for the probands of the 39 siblings varied: 17 met medical exclusion criteria (i.e. the proband had a diagnosis of schizophrenia but had an additional diagnosis that complicated interpretation of cognitive data); 8 failed to complete the study but was considered to have a reliable schizophrenia diagnosis; and 14 completed the CANTAB whereas their ill family member did not. Estimated full scale IQ from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, revised edition (WAIS-R) and reading ability using the Wide Range Achievement Test revised (WRAT-R), a measure of premorbid IQ, (26) are reported for descriptive purposes. The demographic features of the study groups are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characterization of all three groups.

| Patients (n=147) | Siblings (n=131) | Controls (n=303) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Years (mean(s.d.)) | 33.59 (9.94) | 35.56 (10.18) | 31.42 (9.55) |

| Gender: male/female | 103/44 | 52/79 | 122/181 |

| Education, Years (means(s.d.)) | 14.13(2.17) | 15.99(2.27) | 16.8(2.36) |

| Estimated FSIQ (mean(s.d.)) | 90.4 (11.27)1 | 106.3 (10.29) | 106.82 (10.16)2 |

| WRAT-R Standard Score (mean(s.d.)) | 100.99 (11.78)3 | 108.06 (8.39) | 106.98 (9.15)4 |

Based on n=146.

Based on n=296.

Based on n=145.

Based on n=295.

A t-test comparison of current IQ between groups revealed significant differences between patients and siblings (t (98.35) = −12.21, p<0.0001) and patients and controls (t (98.61) = −15.41, p<0.0001), but showed no difference between siblings and controls.

Neuropsychological testing

The ID/ED task is a computerized task that consists of 9 stages. Stimuli were displayed in outlined boxes to the left and right of center screen, as well as centered top and bottom. The boxes served to outline the response area (Figure 1). Failure at a stage occurs if passing criterion, 6 consecutive correct responses, is not met by the 50th trial, at which point the tests conclude. Performance measures include the percentage of subjects successfully completing each stage, total errors committed at each stage, and the number of stages passed (27). Representative stimuli for stages can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

A screenshot of a typical trial from the CD2 stage.

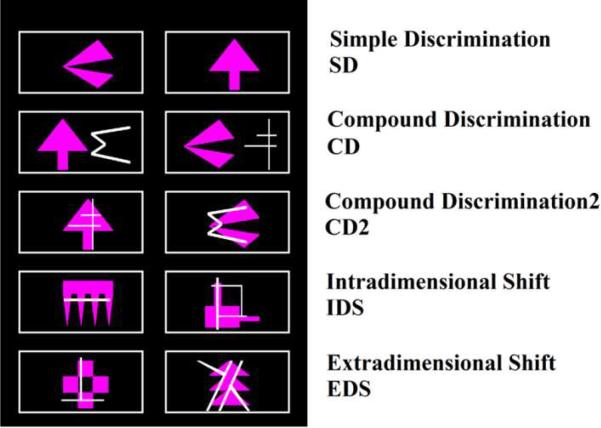

Figure 2.

CANTAB stages without reversal stages.

At the first, simple discrimination stage of the test, subjects see two shapes and must determine which one is correct. After making 6 correct responses in a row, the rule changes so that the other stimulus is correct. This reversal stage assesses a very elementary form of set shifting: can the subject shift from a previously rewarded response choice to a new choice in the face of negative feedback? At the compound discrimination phase, the subject must again determine which is the correct shape stimulus but is now challenged by the presence of irrelevant line segments that are near the shapes. The second compound discrimination stage consists of a line element superimposed over the shape stimulus, making ignoring the distractor line element more difficult. Thus, the subject must focus attention on the relevant stimuli, and after 6 correct selections, the reinforcement contingencies reverse. The intradimensional shift stage, the sixth, asks that subjects apply previously learned rules to new shape stimuli. Thus, subjects must learn that a new shape will be rewarded in this stage, an example of an intradimensional shift. Upon successful completion this stage is followed by a reversal stage. At the critical extradimensional shifting stage subjects need to shift their attention to the previously irrelevant line stimuli and ignore the previously reinforced shapes, precisely the same kind of shifting assessed on the WCST (13, 28, 29).

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis of demographic data was performed using STATISTICA 7 (30), and are shown in Table 1 for descriptive purposes. Age differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA's. Gender ratios were analyzed using chi-square tests. Both ANOVA and correlations were used to assess the influence of current IQ on ID/ED performance.

Our first analysis included all available patients, siblings, and controls with CANTAB data. Outcomes on the CANTAB test were divided into 10 possible ordered categories, based on the stage at which a participant failed the test, with those passing all stages ranked into the highest category (“stage 10”). SAS® PROC FREQ was used to compute Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) test statistic (31) for pairwise comparisons of the distribution of stage attained in patients, siblings and controls. This statistic tests the null hypothesis that Pr(y>x) =0.5, where x and y are the stages at which randomly chosen members of group x and group y (e.g., controls and siblings) end the test. The alternative tested is that one group has a higher probability of reaching a later stage than the other. Because of the small cell sizes at earlier stages, the p-value was computed from the exact (permutation) distribution of this statistic.

Fisher's exact test was used to perform pairwise group comparisons on the stage-specific conditional failure probability (the probability of failing at a given stage, having passed all preceding stages). Westfall and Young's step-down bootstrap (32) method was used to maintain the Type I error rate at alpha=0.05 while performing multiple comparisons (9 stages × 3 sets of pairwise comparisons).

The distribution of errors on the CANTAB battery is highly non-normal. Accordingly, pairwise comparisons of error rates among groups were conducted using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using Benjamin and Hochberg's (33) method for controlling false discovery rates.

Results

Demographic features

A one-way ANOVA revealed age differences between the three groups (F (2,578) =8.68, p=0.0002); post hoc analysis revealed a significant difference between siblings and controls. Previous normative studies of ID/ED shift performance have reported that aging effects only emerge after the age of 50 (34, 35), suggesting that the mean 4 year age difference between young adult controls and siblings was unlikely to impact our results. Correlational analyses revealed that age was not significantly correlated with performance in any diagnostic group.

Gender ratios differed significantly between patients and controls (X2=35.17, p<0.0001), and between patients and siblings (X2=25.90, p<0.0001). There was no significant difference in gender ratio observed between siblings and controls Gender did not impact performance in any of our subject groups and was not considered in further analyses.

CANTAB Results

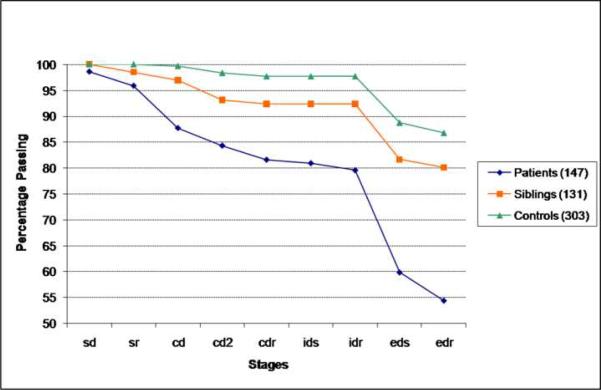

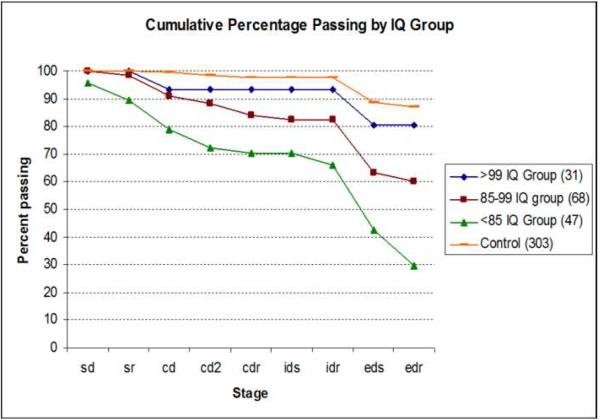

The cumulative percentage of subjects in each group passing the 9 stages of the ID/ED task is shown in Figure 3. Nearly all controls (87%) finished the task successfully as did 80% of siblings. In contrast only 54% of patients with schizophrenia were able to complete the task. There was a highly significant difference in the distribution of the number of stages to failure among all three groups (MH=25.13, p<0.0001). This overall analysis was followed by a series of contrasts between pairs of groups. There were also significant group differences in the overall distribution of stages to failure between siblings and controls (MH=8.16, p=0.004), between patients and controls (MH=60.84, p<0.0001), and between siblings and patients (MH=14.12, p=0.0002). Despite the apparent visual similarity of performance across the sibling and healthy comparison group, the two groups differed significantly of this measure of overall task success. Patients performed significantly worse than both the sibling and the healthy comparison group.

Figure 3.

Cumulative percentage of subjects passing by learning stage. Siblings did not significantly differ from controls at any stage.

To explore this sibling difference from controls, we examined the attrition rates at each stage using Fisher's exact tests. None of the stage comparisons were significant. In contrast, patients differed from controls at several stages including SR (p=0.01), CD (p<0.001), EDS (p<0.001) and EDR (p=0.004). Thus, the patient impairment is not limited to the extradimensional shifting phase, but also includes rather simple reversal learning and the ability to ignore irrelevant distractors. Relative to the sibling group, significant patient impairment was similarly observed at the CD (p=0.01), EDS (p=0.01) and EDR (p=0.04) stages.

We examined error scores at each stage, thinking this might prove to be a more sensitive measure than the simple stage pass/fail data. Post hoc pairwise tests at each stage showed that patients had significantly higher mean errors than controls at every stage except SD (p=0.28) and IDS (p=0.07). Mean errors for siblings were not significantly different from control means at any stage, but were different from patient means at every stage except SD (p=0.62), CD2 (p=0.34) and IDS (p=0.22). Note: analysis of error scores on the ID/ED task is limited to those subjects who attempted that stage. Thus, subjects who have already “failed out” of the task are not included in the analysis, perhaps limiting power to detect differences.

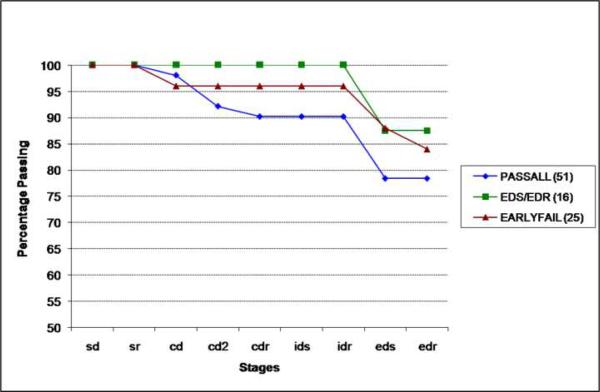

Given these largely negative results in the total group, we reasoned that impairment might occur on a familial basis in too small a subset of siblings to be detected in the overall sample. We therefore examined healthy sibling performance as a function of how their affected sibling performed. To do so, we split the patients into 3 groups: 1) those who completed all stages (PASSALL), 2) those who failed at stage EDS or at the subsequent reversal stage (EDS/EDR), and 3) those patients who were most severely impaired, failing prior to EDS (EARLYFAIL). Thus, if impaired task performance was indeed familial, we would expect to find more evidence of impairment in the siblings of patients in group 2 and 3, and little evidence of impairment from group 1 siblings. The siblings of patients in the EARLYFAIL group (25) were compared to siblings of the EDS/EDR group (16), and siblings of the PASSSALL group (51). In Figure 4, the data strongly contradicted this expectation: siblings of patients who completed all stages had the lowest overall rate (78%) of successfully completing the task. In contrast, 84% of the siblings of the most impaired patients completed all stages while 87.5% of siblings of patients who failed at or after the EDS stage completed all stages. Thus, the siblings of patients who performed the best appeared to perform the worst. These results are inconsistent with the hypothesized familial effect.

Figure 4.

Cumulative percentage of family matched siblings passing by learning stage. PASSALL= Siblings of patients who completed all stages. EDS/EDR= Siblings of patients who failed at or after the EDS stage. EARLYFAIL=Siblings of Patients who failed prior to the EDS stage.

Exploratory analysis

Because there is suggestive evidence that first episode patients are relatively unimpaired on the ID/ED task, and that length of illness may correlate with the extent of impairment in chronic samples, we examined duration of illness effects and found no correlation between overall illness duration and any ID/ED task performance variable in our total patient group. We then compared performance between patients ill less than two years (mean 1.2 (0.7), n=16) with the rest of the patient group (mean 13.9 (9), n=122), and found no statistically significant differences: 75.6% of the under two years of illness group completed all task stages compared to 73.6% of the remaining patients.

In order to examine the role of general cognitive ability, we correlated estimated FSIQ with the number of completed stages and total errors on the ID/ED. In patients, these correlations were: r=0.34, p<0.05 r=−0.44, p<0.05; in siblings r=0.23, p<0.05; r=−0.2, p<0.05; and in controls (r=0.2, p<0.05) r=0.23, p<0.05respectively for stages completed and total errors.

To explore how IQ influences patient performance, patients were split in a low IQ group (IQ<85, n=31), a middle IQ group (IQs= 85–99, n=68), and a high IQ group (IQs>100, n=47). Over 80% of patients in the high IQ group (Figure 5) passed all stages. Just fewer than 60% of the middle group passed all stages, and only 30% of the low IQ group was able to complete the task (F (2,144) =7.65, p<0.01). The low IQ group performed significantly worse than the other two groups (p<0.01). No significant differences were observed between the middle and high IQ group, although the general trend is clear in the Figure. Overall significant differences in the number of errors committed (F (92, 144) =12.9, p<0.01) were also observed between all groups.

Figure 5.

A stage comparison of the percentage of subjects passing by their respective IQ group. The high IQ patient group did not differ significantly from the control group on any performance measure.

Discussion

Several key findings emerged from this analysis of ID/ED performance in patients, siblings and healthy volunteers. First, roughly half of our patients were unable to complete the task indicating a general impairment of set-shifting ability, consistent with prior patient studies (14–16). Our patients demonstrated both the general level and pattern of impairment documented in the literature with marked difficulties at the compound discrimination, extra-dimensional shifting and reversal phases (14, 36). This pattern of results suggests that patients with schizophrenia have impairments in the ability to ignore distractors, inhibit prepotent responses, and shift attention from a previously reinforced stimuli dimension to a previously irrelevant dimension. The fact that our patients demonstrate the same type of impairments documented in other samples of chronically ill patients is important in establishing the potential value of examining the performance of their siblings.

Second, we found only subtle evidence for impairment in siblings. Overall, significantly fewer healthy siblings were capable of completing the task compared with controls. However, there were no statistically significant differences between siblings and controls on the number of errors committed at any stage, nor evidence of impairment among siblings at a specific stage of the task. Thus, siblings demonstrated no specific set-shifting impairment, and inspection of Figure 3 suggests that the siblings, as a group, performed slightly worse than controls, with the subtle difference in cumulative failure rates emerging by stage CD2; thereafter, failure rates at successive stages were closely parallel in the two groups.

The impairment observed in siblings did not appear to be familial: when we examined sibling performance based on how their ill relative performed, we saw little indication of shared impairment. To the contrary, siblings of patients who performed best did worse. These results argue against the role of shared genetic effects impacting ID/ED performance in siblings. The fact that we have found little evidence that performance on the ID/ED task runs in families, coupled with recent evidence that WCST performance may not be heritable, suggests that some aspects of executive function impairment in schizophrenia may, surprisingly, largely implicate non-genetic factors. That is, certain aspects of executive impairment may mark the clinical phenotype, not genetically mediated risk. The success of genetic studies of cognitive intermediate phenotypes is critically dependent on accurate identification and measurement of cognitive deficits that are shared within families, versus those impairments that are associated with clinical illness. At a minimum, we believe our data suggest that the ID/ED task has limited utility as an intermediate phenotype marker.

Is it possible that siblings do not, in fact, have deficits in set shifting given prior claims in the literature? Clearly, one cannot prove the null hypothesis, and the ID/ED test may offer a limited assessment of set shifting. However, this possibility is worthy of careful study. The two clinical tests often cited as providing evidence of set shifting impairments, Trailmaking B and the WCST, involve multiple component operations beyond set-shifting that might be responsible for the observed impairments. For example, impairments on Trailmaking could result from deficits in processing speed. Sibling impairments have been documented on processing speed measures that do not involve set shifting such as verbal fluency and digit symbol, bolstering this possibility. Similarly, the WCST impairment could result from limitations in working memory (which have been well documented in the family literature(36, 37), the ability to process error information, or in reasoning, rather than in set shifting per se. The fact that recent carefully controlled studies of task switching in schizophrenia patients have not produced evidence of set shifting impairments adds weight to the possibility that sibling impairments on the WCST and Trailmaking may not be the result of a specific deficit in set shifting. Additional studies examining different aspects of set-shifting in patients are needed to guide future family research.

Given the suggestive evidence that first-episode patients demonstrate minimal impairment on the ID/ED, the fact that siblings are unimpaired should be expected. Indeed, the rates of task success in several first episode samples (75–80% (16–19)) well surpass our patient group and are closer to the level seen in our control and sibling groups. If patients are unimpaired or minimally impaired at the first onset of illness, it would be surprising if deficits could be detected among well siblings.

We, like Tyson et al (16), were unable to replicate evidence that increasing duration of illness among chronic patients was associated with increasing degree of impairment as reported by Pantelis et al. (23). While the evidence suggesting progression of ID/ED impairment from first episode to chronic illness is based only a few small studies, the idea that executive impairment is something that emerges over time as a consequence of illness is worthy of further careful study given the clinical importance of this question.

Indirectly arguing against an illness specific progressive basis of impairment is the relationship with IQ (which does not progressively decline in schizophrenia (38)). In short, low IQ patients perform extremely poorly whereas our above average IQ group performed very similarly to controls. It is hard to reconcile this powerful effect of IQ with the suggestive evidence of illness related deterioration in ID/ED performance, suggesting that additional longitudinal studies examining both IQ and ID/ED performance are needed to address the important question of whether the illness involves progressive compromise of attentional set-shifting.

It is possible that some of the impairment in patients is secondary to the impact of antipsychotic medications. (39). The fact that we did not observe any impact of duration of illness (and therefore duration of treatment) on task performance suggests that total medication exposure is not likely to be implicated. Available evidence from acute challenge studies has been mixed to date, with some, but not all studies reporting mild impairments (40–43). Thus, it appears unlikely that the dense deficit seen in patients can be fully attributed to medication effects, although further study of this issue is clearly needed.

This study has a number of limitations. Like the WCST, the ID/ED task has psychometric limitations. With more than 80% of siblings and controls passing the task, it is possible that limited variability in task performance produced a false negative result. That is, this task may not be sufficiently sensitive to detect subtle (and possibly heritable) forms of attentional set-shifting impairment. Also, it is certainly possible that the siblings who volunteer for research participation may not be among the most “affected” members of a family, possibly accounting for the limited evidence of impairment we observed. While acknowledging that possibility, the fact that first episode patients appear to demonstrate minimal impairment on the ID/ED test bolsters confidence in our basic conclusions that the ID/ED test is: 1) sensitive to the impairments observed in chronically ill patients; and 2) not a robust intermediate phenotype marker.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosures Alan Ceaser, Drs. Terry Goldberg, Michael Egan, Robert McMahon, and Daniel Weinberger report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Dr. Gold receives royalties from the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia and has served as a consultant to Pfizer, Astra Zenaca, and Merck.

References

- 1.Snitz BE, MacDonald AW, III, Carter CS. Cognitive Deficits in Unaffected First-Degree Relatives of Schizophrenia Patients: A Meta-analytic Review of Putative Endophenotypes. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(1):179–179. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monsell S. Task switching. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2003;7(3):134. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(03)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sohn MMH, Anderson JJR. Task preparation and task repetition: two-component model of task switching. Journal of experimental psychology. General. 2001;130(4):764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meiran NN, Levine JJ, Meiran NN, Henik AA. Task set switching in schizophrenia. Neuropsychology. 2000;14(3):471. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.14.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manoach DS. Schizophrenic subjects show deficient inhibition but intact task switching on saccadic tasks. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51(10):816. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turken AUAU, Vuilleumier PP, Mathalon DHDH, Swick DD, Ford JMJM. Are impairments of action monitoring and executive control true dissociative dysfunctions in patients with schizophrenia? The American journal of psychiatry. 2003;160(10):1881. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kieffaber PD, O'Donnell BF, Shekhar A, Hetrick WP. Event related brain potential evidence for preserved attentional set switching in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;93(1–3):355. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Condray R, Steinhauer SR. Schizotypal personality disorder in individuals with and without schizophrenic relatives: similarities and contrasts in neurocognitive and clinical functioning. Schizophrenia Research. 1992;7(1):33. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(92)90071-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg TE, Ragland JD, Torrey EF, Gold JM, Bigelow LB, Weinberger DR. Neuropsychological assessment of monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(11):1066–1066. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810230082013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keefe RS, Silverman JM, Roitman SE, Harvey PD, Duncan MA, Alroy D, Siever LJ, Davis KL, Mohs RC. Performance of nonpsychotic relatives of schizophrenic patients on cognitive tests. Psychiatry Research. 1994;53(1):1. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(94)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roxborough H, Muir WJ, Blackwood DH, Walker MT, Blackburn IM. Neuropsychological and P300 abnormalities in schizophrenics and their relatives. Psychological medicine. 1993;23(2):305. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kremen WS, Eisen SA, Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ. Is the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test a useful neurocognitive endophenotype? American journal of medical genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics. 2007;144(4):403. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downes JJ, Roberts AC, Sahakian BJ, Evenden JL, Morris RG, Robbins TW. Impaired extra-dimensional shift performance in medicated and unmedicated Parkinson's disease: evidence for a specific attentional dysfunction. Neuropsychologia. 1989;27(11–12):1329. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(89)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jazbec S, Pantelis C, Robbins T, Weickert T, Weinberger DR, Goldberg TE. Intra-dimensional/extra-dimensional set-shifting performance in schizophrenia: impact of distractors. Schizophr Res. 2007;89(1–3):339–49. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pantelis C, Barber FZ, Barnes TRE, Nelson HE, Owen AM, Robbins TW. Comparison of set-shifting ability in patients with chronic schizophrenia and frontal lobe damage. Schizophrenia Research. 1999;37(3):251. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyson PJ, Laws KR, Roberts KH, Mortimer AM. Stability of set-shifting and planning abilities in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2004;129(3):229–229. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutton SB, Puri BK, Duncan LJ, Robbins TW, Barnes TR, Joyce EM. Executive function in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychological medicine. 1998;28(2):463. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joyce E, Hutton SAM, Mutsatsa S, Gibbins H, Webb E, Paul S, Robbins T, Barnes T. Executive dysfunction in first-episode schizophrenia and relationship to duration of untreated psychosis: the West London Study. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181(43):s38–44. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.43.s38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joyce EM, Hutton SB, Mutsatsa SH, Barnes TRE. Cognitive heterogeneity in first-episode schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187(6):516–516. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.6.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joyce EM, Hutton SB, Mutsatsa SH, TRE B. Improvement of deterioration in different executive cognitive processes early in the course of schizophrenia (abstract) schizophr Res. 1999;36(1–3):138. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joyce EM. Executive function in first episode schizophrenia: improvement at one year. Schizophrenia Research. 1998;29(1):53. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abstracts of the 11th International Congress on Schizophrenia Research. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(2):203–203. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pantelis C, Harvey CA, Plant G, Fossey E, Maruff P, Stuart GW, Brewer WJ, Nelson HE, Robbins TW, Barnes TRE. Relationship of behavioural and symptomatic syndromes in schizophrenia to spatial working memory and attentional set-shifting ability. Psychological medicine. 2004;34(4):693. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Research Version (SCID-I) New York Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II), version 2. New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jastak S, Wilkinson GS. The Wide Range Achievement Test, Revised. Wilmington, Deleware; Jastak Associates; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul J, Fray TWRBJS. Neuorpsychiatyric applications of CANTAB. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1996;11(4):329–329. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Owen AM, Roberts AC, Polkey CE, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. Extra-dimensional versus intra-dimensional set shifting performance following frontal lobe excisions, temporal lobe excisions or amygdalo-hippocampectomy in man. Neuropsychologia. 1991;29(10):993. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(91)90063-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts AC, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. The effects of intradimensional and extradimensional shifts on visual discrimination learning in humans and non-human primates. The Quarterly journal of experimental psychology. B, Comparative and physiological psychology. 1988;40(4):321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.StatSoft I. STATISTICA (data analysis software system), version 7.1. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mantel N. Chi-Square Tests with One Degree of Freedom; Extensions of the Mantel-Haenszel Procedure. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1963;58(303):690. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westfall PH. Resampling-based multiple testing: examples and methods for p-value adjustment. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjamini Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1995;57(1):289. [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Luca CR, Wood SJ, Anderson V, Buchanan J, Proffitt TM, Mahony K, Pantelis C. Normative data from the CANTAB. I: development of executive function over the lifespan. Neuropsychology, development, and cognition. Section A, Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 2003;25(2):242. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.2.242.13639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robbins TW, James M, Owen AM, Sahakian BJ, Lawrence AD, McInnes L, Rabbitt PM. A study of performance on tests from the CANTAB battery sensitive to frontal lobe dysfunction in a large sample of normal volunteers: implications for theories of executive functioning and cognitive aging.Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 1998;4(5):474. doi: 10.1017/s1355617798455073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diaz-Asper CM, Goldberg TE, Kolachana BS, Straub RE, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. Genetic Variation in Catechol-O-Methyltransferase: Effects on Working Memory in Schizophrenic Patients, Their Siblings, and Healthy Controls. Biological Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.031. In Press, Corrected Proof. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egan MF, Goldberg TE, Gscheidle T, Weirich M, Rawlings R, Hyde TM, Bigelow L, Weinberger DR. Relative risk for cognitive impairments in siblings of patients with schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;50(2):98. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurtz MM. Neurocognitive impairment across the lifespan in schizophrenia: an update. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;74(1):15. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chudasama YY, Robbins TTW. Functions of frontostriatal systems in cognition: comparative neuropsychopharmacological studies in rats, monkeys and humans. Biological Psychology. 2006;73(1):19. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barrett SL, Bell R, Watson D, King DJ. Effects of Amisulpride, Risperidone and Chlorpromazine on Auditory and Visual Latent Inhibition, Prepulse Inhibition, Executive Function and Eye Movements in Healthy Volunteers. J Psychopharmacol. 2004;18(2):156–156. doi: 10.1177/0269881104042614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCartan D, Bell R, Green JF, Campbell C, Trimble K, Pickering AD, King DJ. The differential effects of chlorpromazine and haloperidol on latent inhibition in healthy volunteers. J Psychopharmacol. 2001;15(2):96–96. doi: 10.1177/026988110101500211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehta MA, Sahakian BJ, McKenna PJ, Robbins TW. Systemic sulpiride in young adult volunteers simulates the profile of cognitive deficits in Parkinson's disease. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146(2):162–162. doi: 10.1007/s002130051102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vollenweider FX, Barro M, Csomor PA, Feldon J. Clozapine Enhances Prepulse Inhibition in Healthy Humans with Low But Not with High Prepulse Inhibition Levels. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60(6):597. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]