Abstract

The importance of type I IFN signaling in the innate immune response to viral and intracellular pathogens is well established, with an increasing literature implicating extracellular bacterial pathogens, including Staphylococcus aureus in this signaling pathway. Airway epithelial cells and especially dendritic cells (DC) contribute to the production of type I IFNs in the lung. We were interested in establishing how S. aureus activates the type I IFN cascade in DC. In vitro studies confirmed the rapid uptake of S. aureus by DC followed promptly by STAT1 phosphorylation and expression of IFN-β. Signaling occurred using heat-killed organism and in the absence of PVL and α-toxin. Consistent with the participation of endosomal and not cytosolic receptors, signaling was predominantly mediated by MyD88, TLR9 and IRF1 and blocked by cytochalasin D, dynasore and chloroquine. To determine the role of TLR9 signaling in the pathogenesis of S. aureus pneumonia we infected WT and Tlr9−/− mice with MRSA USA300. Tlr9−/− mice had significantly improved clearance of S. aureus from the airways and lung tissue. Ifnar−/− mice also had improved clearance. This enhanced clearance in Tlr9−/− mice was not due to differences in the numbers of recruited neutrophils into the airways, but instead correlated with decreased induction of TNF. Thus, we identified TLR9 as the critical receptor mediating the induction of type I IFN signaling in dendritic cells in response to S. aureus, illustrating an additional mechanism through which S. aureus exploits innate immune signaling to facilitate infection.

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a common cause of pneumonia, the most frequent pathogen identified with health care associated pneumonias (1, 2), as well as major cause of superinfection and mortality following influenza (3-8). Analysis of the patterns of human staphylococcal infection and the use of murine models, suggest that participation of type I IFN signaling, a major component of the host response to influenza and other respiratory viral infections, actually contributes to the pathology associated with staphylococcal pneumonia (9). S. aureus as well as several other bacterial pulmonary pathogens trigger type I IFN signaling (10-12). This is mediated by airway epithelial cells that can be activated directly by either intact bacteria or shed pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (10), as well as by dendritic cells (DCs) which account for a substantial amount of type I IFN signaling (13). Type I IFN signaling is generally initiated from intracellular receptors, those that would respond to intracellular pathogens such as viruses. As S. aureus persist intracellularly in both phagocytic and non-phagocytic cells (14), it is well positioned to activate type I IFN signaling.

The severity of S. aureus pneumonia is due to both expression of specific virulence factors as well as the nature of the host response that is activated. The epidemic USA300 strain of methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is associated with especially severe pneumonia in humans that can be modeled in mice using a high bacterial inoculum; this results in 80% mortality by 24 hours post inoculation in wild type 129/SvEv mice but less than 10% mortality in Ifnar−/− mice (15). The excessive activation of proinflammatory signaling, mediated by airway epithelial cells as well as resident and recruited macrophages, T cell and DCs, is thought to contribute to this pathology.

Dendritic cells have multiple roles in mucosal defense. They have signaling capabilities linking pathogen recognition and activation of T cells as well as functioning as a major source of the type I interferons in viral infection (16). DCs are also phagocytic and appear to contribute to S. aureus clearance as was demonstrated using a CD11C-DTR depletion murine model of pneumonia (17). We were interested in establishing how DCs interact with S. aureus and their participation in type I IFN signaling in the host response to S. aureus pulmonary infection. In the studies detailed in this report, we demonstrate that DCs actively phagocytose S. aureus and activate gene expression in response to the recognition of staphylococcal DNA by TLR9. Consistent with the hypothesis that type I IFN signaling increases susceptibility to severe staphylococcal pneumonia, Tlr9−/− mice had improved staphylococcal clearance from the lung without defects in the recruitment of phagocytes into the lung.

Materials and methods

Bacteria and cell culture

S. aureus USA300 strains FPR3757 (18) and LAC (19) were grown in Luria Bertani broth at 37°C. No differences in Ifnb induction were observed between these strains (data not shown). Heat-killed preparations of S. aureus were obtained by heating cells at 65°C for 1.5 h. Bone marrow derived dendritic cells (BMDC) were cultured from wild-type and knockout mice as described previously (11). BMDC were stimulated with S. aureus (MOI 100) for 2 h. Cytokine studies on BMDC for ELISA quantitation were conducted for 20 h with an MOI of 5. Cell lysate experiments were performed using exponential phase S. aureus resuspended at 5 × 109 cfu/ml. S. aureus suspensions were treated with 500μg/ml lysostaphin (Sigma) for 10 min at 37°C before sonication then DNase and RNase treatment as before (11). Experiments with cellular inhibitors were performed by preincubating the cells for 30 min prior to bacterial stimulation using: cytochalasin D 20 μM (Sigma), dynasore 80 μM (20) and chloroquine 10 μM (Sigma). Stimulation of BMDC for ELISA analysis was performed for 20 h at an MOI of 5.

RNA analysis

RNA was isolated using the PureLink RNA mini kit (Life Technologies) followed by DNase treatment using DNAfree (Life Technologies). cDNA was synthesized using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). qRT-PCR was performed using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix in a StepOne Plus thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems). Samples were normalized to β-actin. Primers for mouse actin, Ifnb, and Mx1, KC, Il6 have been described elsewhere (15, 21). Primers used for; Cxcl10 were: sense-5′-CGATGACGGGCCAGTGAGAATG-3′ and antisense 5′-TCAACACGTGGGCAGGATAGGCT-3′, Tnf- sense 5′-ATGAGCACAGAAAGCATGATC-3′ and antisense 5′-TACAGGCTTGTCACTCGAATT-3′, Mcp1- sense-5′-ATCCCAATGAGTAGGCTGGAGAGC-3′ and antisense 5′CAGAAGTGCTTGAGGTGGTTGTG.

Western Hybridization

BMDC were lysed in RIPA buffer (20mM Tris-HCl, 150mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) with Halt protease and phosphatase single-use inhibitors (Thermo Scientific). Phosphorylation of transcription factors was detected using antibodies to P-IRF3 (S396, Cell Signaling), P-IRF7 (S471/472, Cell Signaling) and P-STAT1 (Y701, Abcam) normalized to β-actin (Sigma), as transcription of total protein can be regulated (22). Protein separation, transfer and detection has been described elsewhere (11).

Microscopy

Exponential phase bacteria were labeled with 100 μg/ml of fluorescein isothiocyanate in PBS with calcium and magnesium (Cellgro) for 20 min before three washes and incubation with BMDC as above. Fluorescence microscopy was performed using a Zeiss Observer Z1 inverted fluorescence microscope with AxioVision software (version 4.6.2.0; Zeiss).

Mouse studies

C57Bl/6J, Tlr7−/− and Irf1−/− mice were from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, MN USA). All mice were on a C57Bl/6J background. Six-week-old sex-matched mice were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 5 mg/kg xylazine before intranasal inoculation with 2-5 × 107 cfu of S. aureus USA300 (18). Mortality (including mice moribund that were euthanized) data was from infections with 1-2 × 108 cfu of S. aureus USA300. Mice were euthanized 20 h later when bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was obtained before lungs were extracted. Bacteria were enumerated from BALF and lung homogenate using serial dilution before plating on CHROMagar S. aureus plates at 37°C (Becton Dickinson). All mouse infections were performed under the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Columbia University.

FACS

Analysis of cell populations in BALF was conducted as before (11). Cells were labeled with combinations of fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled anti-Ly-6G (Gr-1; RB6-8C5; eBioscience), PerCP-Cy5.5-labelled anti-CD11c (N418; eBioscience), allophycocyanin-labelled anti-MHC II (I-A/I-E; eBioscience), phycoerythrin-labelled anti-NK 1.1 (NKR-P1C, Ly-55; eBioscience), phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CD4 (RM 4-5; eBioscience) and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled anti-CD3 (eBIO500A2;eBioscience). Neutrophils were defined as Ly6G+/MHCII−, macrophages as CD11C+/MHCIIlow-mid and dendritic cells as CD11C+/MHCIIhigh. Data were analyzed using WinMDI (version 2.8; Joseph Trotter).

Cytokine studies

Cytokines levels were quantified using ELISA: TNF, IFN-γ, IL-17, eBioscience, and KC, IL-6, CXCL10, (R&D Systems). The IFN-β ELISA was from PBL InterferonSource.

Statistics

Significance of data that followed a normal distribution was determined using a two-tailed Student t test, and for data that did not follow a normal distribution, a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used. Dichotomous outcomes were assessed using the Fisher exact test. Statistics were performed with Prism software (GraphPad, La Jolla LA USA).

Results

Conserved components of S. aureus activate type I IFN signaling in BMDC

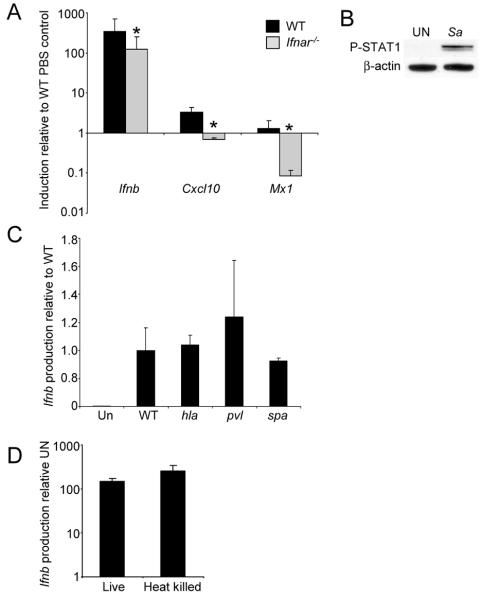

The virulence of the epidemic USA300 strains of S. aureus has been attributed to their activation of multiple host immune signaling cascades, a consequence of expression of specific virulence factors, especially the secreted toxins. We first established that BMDC are highly responsive to S. aureus USA300, observing significant induction of Ifnb after only a 2 h exposure (Fig. 1A) and the expected phosphorylation of STAT 1 (Fig. 1B). Since the activation of the type I IFN signaling cascades are highly influenced by autocrine signaling as well as by exogenous ligands, we monitored the involvement of IFNAR in amplification of this IFN-β response. Induction of Ifnb in Ifnar−/− BMDC was reduced by 64% in comparison to WT controls (P<0.01) (Fig. 1A). We also examined the transcription levels of two type I IFN-dependent genes, Cxcl10 (23) and Mx1 (24) in WT and Ifnar−/− BMDC after S. aureus stimulation. Even at this early time point both Cxcl10 and Mx1 were induced in WT BMDC compared to unstimulated cells and reduced in Ifnar/- cells (Fig. 1A) indicating the contribution of both direct activation of type I IFN signaling by bacterial ligands as well as substantial amplification by autocrine signaling.

Figure 1.

Activation of type I interferons by S. aureus in BMDC. A) S. aureus USA300 was incubated with BMDC from WT and IFNAR null mice and levels of gene expression assessed by qRT-PCR. B) Phosphorylation of STAT1 detected using immunoblots from WT BMDC stimulated with S. aureus for 2 h. β-actin was used as a loading control. C) WT BMDC were incubated with WT and mutants strains of S. aureus USA300 and levels of Ifnb assessed by qRT-PCR. D) Assessment of Ifnb induction of live versus heat killed S. aureus USA300 using WT BMDC. Results are representative of two independent experiments. Graphs display means and standard deviation. *P<0.05 (n=3, students t test). UN-unstimulated, Sa-S. aureus.

To address the role(s) of specific staphylococcal virulence factors in Ifnb induction, we compared several isogenic mutants in the USA300 background. The α-toxin (Hla, encoded by hla) of S. aureus is important in numerous models of infection and has been shown to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in monocytes (14, 25, 26). However, Hla was not required for Ifnb induction (Fig. 1C), nor was expression of the Panton Valentine Leukocidin (PVL, pvl-lukS/lukF mutant) (14, 27, 28) in these murine cells (Fig. 1C). The abundant surface protein, protein A (encoded by spa), has been shown to play a role in type I IFN signaling in epithelial cells, as well as contributing to invasion in various cell types (15, 29, 30), but was not required for Ifnb induction in BMDC (Fig. 1C). We inferred from these data that a generally conserved PAMP of S. aureus is likely to be involved in the activation of type I IFN signaling. Consistent with this, we did not observe a decrease in signaling with heat-killed organisms (Fig. 1D), suggesting that the activation of the BMDC was primarily a function of the DC and not an active process initiated by the organism.

Ifnar−/− mice display improved clearance of S. aureus from the lung

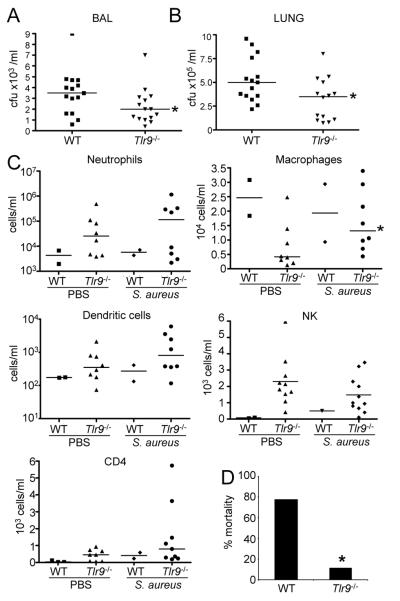

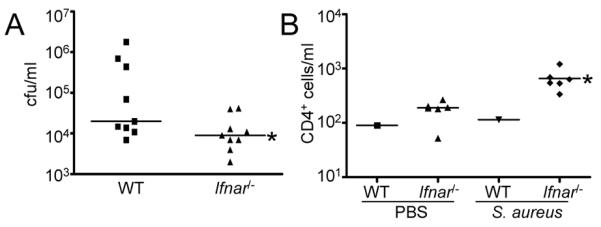

The biological significance of staphylococcal induction of the type I IFN cascade has been previously reported based on experiments using a high inoculum of USA300 in Svev/129 Ifnar−/− mice. These Ifnar−/− mice have significantly reduced mortality in an acute pneumonia model of infection (15). To determine if C57Bl/6J Ifnar−/− are similarly protected from severe infection at lower doses of S. aureus, we infected mice intranasally with 107 cfu of S. aureus USA300. Enumeration of bacteria from lung homogenates at 24 h post inoculation indicated an average of 20-fold (P<0.05) fewer bacteria present than the WT control mice (Fig. 2A). The cellular populations comprising the inflammatory infiltrate in the BALF of the WT and Ifnar−/− were similar, and aside from a slight increase in CD4+ cells (Fig. 2B), no compensatory changes in other cells types were observed (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Ifnar−/− mice have improved clearance of S. aureus from the lung. Mice were inoculated intranasally with S. aureus USA300 for 20 h before sacrifice. A) Bacteria were enumerated from lung homogenate. B) CD4+ cell counts were determined using FACS analysis from BAL samples. FACS data is representative of two independent experiments. Each point represents a mouse. Lines display median values. *P<0.05.

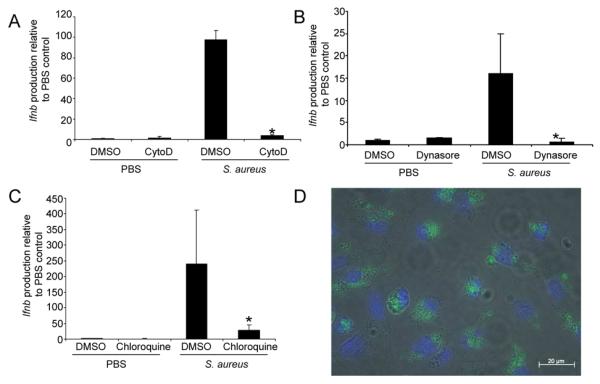

Phagocytosis and endosomal acidification are required for signaling

The activation of type I IFN signaling cascades is often initiated by intracellular receptors that respond to ligands that are either endocytosed or available in the cytosol (31). As dendritic cells are phagocytic, we investigated the role of uptake of intact S. aureus as a requirement for type I IFN activation. In the presence of cytochalasin D, an inhibitor of actin polymerization, induction of Ifnb was reduced by 96% (P<0.001) (Fig. 3A). The involvement of dynamin mediated endocytosis was addressed by treating the BMDC with dynasore, which inhibits the GTPase activity of dynamin (20). Incubation of BMDC with dynasore led to a 92% decrease (P<0.05) in Ifnb induction in response to S. aureus (Fig. 3B). The subsequent involvement of endocytic processing was tested by treating the BMDC with chloroquine, which prevents endosomal acidification and interferes with TLR signaling (32-34). In response to S. aureus, chloroquine-treated BMDC induced 96% less Ifnb (P<0.05) than the untreated controls (Fig. 3C). Consistent with the requirement for phagocytosis of S. aureus for type I IFN signaling to occur we observed large numbers of S. aureus inside the cytoplasm of BMDC following two hours of incubation (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Uptake of S. aureus is required for type I interferon production. WT BMDC were stimulated with S. aureus USA300 in the presence of A) cytochalasin D (cytoD), B) dynasore or C) chloroquine compared to a DMSO control (n=6). D) FITC-labelled S. aureus USA300 (green) visualized inside WT BMDC, cell nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Graphs display means and standard deviation and are representative of two independent experiments. *P<0.05.

TLR9 senses S. aureus DNA to induce type I IFN signaling

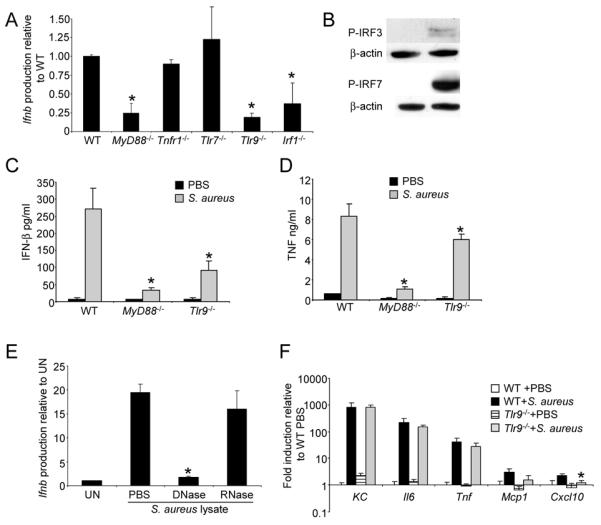

Based on our observation that host factors, endocytosis and endosomal acidification were necessary for IFN-β signaling, we postulated that endosomal TLRs were involved in staphylococcal recognition. Type I IFN signaling can be mediated by either MyD88 or TRIF-dependent pathways. The ability of S. aureus to activate Ifnb in MyD88−/− BMDC was decreased on average by 75% (P<0.05) compared to WT cells (Fig. 4A), whereas Trif−/− cells were not affected as greatly. At the same time we did not see a decrease in Ifnb induction using a mutant lacking a known receptor for S. aureus TNFR1 (35) (Fig. 4A). MyD88-dependent type I IFN signaling occurs through TLR7 and TLR9 in mice (36). TLR9 is located in the endosome and responds to CpG DNA, a likely product of staphylococcal degradation. The ability of S. aureus to activate Ifnb in a null background of TLR7 was unimpaired, but there was a significant (82% decrease, P<0.05) decrease in signaling associated with the Tlr9−/− cells (Fig. 4A). As would be expected for MyD88-dependent TLR9 signaling we saw significant decrease in Ifnb induction using Irf1−/− BMDCS (37, 38), as well as induction of IRF7 phosphorylation in response to S. aureus, as opposed to only a minor amount of IRF3 phosphorylation (Fig. 4B) (10). Consistent with the RNA data we observed a significant reduction in IFN-β levels in MyD88−/− and Tlr9−/− BMDC (88%, P=0.002; 66%, P=0.009, respectively) (Fig. 4C). This contrasted to TNF levels, which were also significantly reduced in MyD88−/− BMDC (87%, P=0.007) but only reduced by 27% in Tlr9−/− BMDC (P=0.049) (Fig. 4D). The role of TLR9 (39) in sensing staphylococcal DNA was confirmed by incubating BMDC with lysates of S. aureus USA300 treated with DNase and RNase. Stimulation of BMDC with lysate treated with DNAse resulted in a 90% decrease (P<0.001) in signaling compared to the untreated lysates (Fig. 4E), while treatment of lysate with RNase had no significant effect on Ifnb levels (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

TLR9 is the receptor for S. aureus DNA induced type I interferon signaling. A) BMDC from WT and knockout mice were cultured with S. aureus for 2 h and levels of Ifnb were detected using qRT-PCR. Data are from two independent experiments (n=6). B) Phosphorylation of IRF3 and 7 was detected using immunoblots from WT BMDC stimulated with S. aureus USA300 for 2 h. β-actin was used as a loading control. BMDC were incubated with S. aureus USA300 for 20 h and supernatants collected for C) IFN-β and D) TNF ELISA. E) BMDC were incubated with S. aureus lysates treated with DNase and RNase and levels of Ifnb quantitated with qRT-PCR. Shown is a representative of two independent experiments (n=3). F) BMDC from WT and Tlr9−/− mice were stimulated with S. aureus and transcript levels of proinflammatory cytokines measured by qRT-PCR. Shown is a representative of two independent experiments (n=3). *P<0.05. UN-unstimulated.

We examined the transcription levels of several genes to monitor the contribution of TLR9 to the induction of other gene products. Apart from Cxcl10, a gene known to be regulated by type I IFN signaling and associated with lung pathology (40), no other significant changes were observed (Fig. 4F).

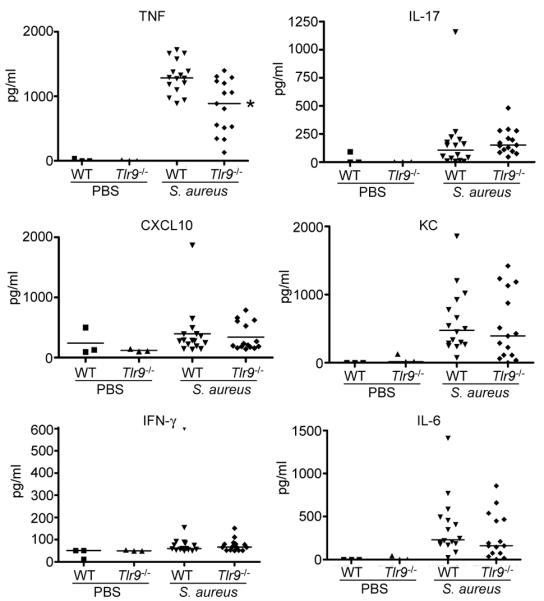

TLR9 mice have improved outcome in a mouse pneumonia model

SvEv/129 Ifnar−/− mice have improved outcome in response to S. aureus pneumonia (15), an observation we confirmed in the C57/Bl6 background (Fig. 2). To determine the role that TLR9 mediated type I IFN signaling plays in the overall host response to S. aureus infection we compared the responses of WT and Tlr9−/− mice in our model of acute S. aureus pneumonia. After 24 h of infection Tlr9−/− mice had improved clearance of S. aureus from both the BALF (36% reduction, P<0.05, Fig. 5A) and lung homogenate (39% reduction, P<0.05, Fig. 5B). We did not observe major changes to the overall cellular composition of BALF (Fig. 5C), with the exception of a 2-fold (P<0.05) increase in macrophage numbers. At higher inocula, less mortality (11% vs 78%) was observed in Tlr9−/− mice compared to WT controls (Fig. 5D). There were similarly minimal consequences of TLR9 signaling on cytokine production in vivo (Fig. 6). TNF levels were reduced by 35% (P<0.05) in infected Tlr9−/− compared to WT mice (Fig. 6) whereas the other proinflammatory cytokines were unchanged. The improved clearance of Tlr9−/−mice and concomitant decrease in TNF is consistent with the negative impact of TNF signaling on S. aureus pulmonary infection (35).

Figure 5.

TLR9 knockout mice have improved clearance of S. aureus from the airways. Mice were inoculated intranasally with S. aureus USA300 and the response to infection assessed 24 h later. Bacteria were enumerated from A) BALF and B) lung homogenate. C) Cell populations were determined using FACS analysis from BAL samples. D) WT and Tlr9−/− mice were infected with 1-2×108 cfu and assessed for mortality 20 h later (n=8-WT, n=9-Tlr9−/−). Each point represents a mouse. Lines display median values. *P<0.05.

Figure 6.

Cytokine responses of WT and Tlr9−/− mice to S. aureus. Mice were infected intranasally with S. aureus USA300 for 24 h before BAL was performed. Cytokine levels in BALF were determined using ELISA. Each point represents a mouse. Lines display median values. *P<0.05

Discussion

Dendritic cells are important participants in the innate immune responses to inhaled bacterial pathogens. The immature DCs in the lung are avidly phagocytic (41), prior to maturation and the acquisition of surface markers associated with the ability to traffic to local lymph nodes. While the importance of DCs in communicating with T cells is well established, their role in the pathogen recognition is less well characterized. In the in vitro data presented, we observed that DCs readily take up S. aureus through a classical endocytic process that results in the activation of TLR9 signaling. This observation is consistent with previous studies in which mice depleted of CD11C+ cells, primarily DCs but also some macrophage populations as well, had diminished clearance of S. aureus from the lung (17). Although neutrophils are primarily responsible for the clearance of pathogens such as S. aureus from the airway, it appears that pulmonary DCs also contribute to bacterial uptake early in infection.

Perhaps the more significant consequence of DC uptake of S. aureus, is the activation of TLR9 signaling and production of type I IFNs. DNA is sensed by a number of both endosomal and cytosolic receptors activating the expression of type I IFN signaling (42). This is a rapid response to endocytosed staphylococci, with IRF7 and STAT1 phosphorylation detected within 2 hours of exposure, indicating that DCs are efficient in degrading the ingested organisms. In contrast to other mechanisms of immune activation such as the NLRP3 inflammasome (25), staphylococcal induction of type I IFN signaling did not require participation of α-toxin or other toxins, but is mediated by bacterial DNA. Endocytosis and induction of IFN-β expression appears to be accomplished primarily by the DC, as heat-killed organisms are equally stimulatory as viable bacteria. Although a protein A mutant was not diminished in its stimulatory capacity for Ifnb, SpA is abundantly shed by organisms during growth and can activate signaling through TNF receptor 1 and IRF1, which can be activated by TNF as well. IRF1 has been shown to be involved in TLR9 signaling in myeloid DCs (37, 38). Streptococcus pneumoniae, another common pulmonary pathogen, also activates the production of type I IFNs. However, the signaling pathway activated in response to these organisms requires expression of the pore-forming toxin pneumolysin which facilitates DNA entry (11). Pneumococcal DNA signals through DAI and STING, and not through TLR9 (11) indicating that specific pathogens may activate discrete signaling pathways.

S. aureus may also differ from other respiratory pathogens by virtue of its ability to activate innate immune signaling through many different mechanisms. These include the MyD88 dependent TLRs, TLR2 and TLR9; TNFR1 (35, 43-46) as well as through NOD2 and NLRP3 (35, 47-51). Such redundancies in proinflammatory gene activation may explain the especially exuberant inflammatory response associated with severe staphylococcal pneumonia. We also noted a significant amplification of Ifnb mediated by the autocrine effects of the cytokine on IFNAR, which occurred as secondary consequence of the initial staphylococcal ligand-receptor interaction. Thus, it is perhaps not unexpected that mice lacking a component of the immunostimulatory cascade, such as the Tlr9−/− or Ifnar−/− mutants, were in fact better able to clear S. aureus from the lungs than wild type mice. Improved bacterial clearance has also been observed in the Tlr9−/− murine model of polymicrobial sepsis (52). This is in contrast to the results described for other bacterial respiratory pathogens in which TLR9 was important for bacterial clearance (53-55). Staphylococcal activation of TNF signaling has been previously correlated with decreased staphylococcal clearance, increased pathology and mortality (35). As shown in these experiments, levels of TNF also inversely correlated with the outcomes observed in the Tlr9−/− and Ifnar−/− mice (15). Of note, macrophage derived TNF, which is also signaled through TLR9 (43) would be decreased. Thus, the participation of TLR9 signaling to staphylococcal clearance from the lung, like that of the type I IFN cascade overall, has negative consequences, at least in the initial response to the infection.

These results further help to explain the increased susceptibility and excessive morbidity associated with S. aureus pneumonia, particularly as a complication of influenza in humans (8). The influx of DCs into the lung and the induction of type I IFN signaling are major responses to influenza. While these DCs will participate in staphylococcal clearance, the additional contribution of the subsequent TLR9 signaling to the overall type I IFN response in the lung is likely to be detrimental in the ultimate outcome of infection. Moreover, while S. aureus DNA is the critical ligand in DC –TLR9 signaling, these organisms have additional PAMPs that activate similarly deleterious IFN-β responses in the non-phagocytic respiratory epithelial cells (15). The proficiency of S. aureus as a human pulmonary pathogen is likely a consequence of its multiple mechanisms to exploit innate immune defenses, operating by different signaling pathways in specific cell types.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Ryan Rampersaud and Connie Woo for bone marrow from knock out mice, and Diane Dapito and Robert Schwabe for Tlr9−/− mice.

References

- 1.Kollef MH, Shorr A, Tabak YP, Gupta V, Liu LZ, Johannes RS. Epidemiology and outcomes of health-care-associated pneumonia: results from a large US database of culture-positive pneumonia. Chest. 2005;128:3854–3862. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray S, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Dumyati G, Townes JM, Craig AS, Zell ER, Fosheim GE, McDougal LK, Carey RB, Fridkin SK. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:1763–1771. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finelli L, Fiore A, Dhara R, Brammer L, Shay DK, Kamimoto L, Fry A, Hageman J, Gorwitz R, Bresee J, Uyeki T. Influenza-associated pediatric mortality in the United States: increase of Staphylococcus aureus coinfection. Pediatrics. 2008;122:805–811. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iverson AR, Boyd KL, McAuley JL, Plano LR, Hart ME, McCullers JA. Influenza virus primes mice for pneumonia from Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:880–888. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee MH, Arrecubieta C, Martin FJ, Prince A, Borczuk AC, Lowy FD. A postinfluenza model of Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:508–515. doi: 10.1086/650204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louria DB, Blumenfeld HL, Ellis JT, Kilbourne ED, Rogers DE. Studies on influenza in the pandemic of 1957-1958. II. Pulmonary complications of influenza. J Clin Invest. 1959;38:213–265. doi: 10.1172/JCI103791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robertson L, Caley JP, Moore J. Importance of Staphylococcus aureus in pneumonia in the 1957 epidemic of influenza A. Lancet. 1958;2:233–236. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(58)90060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louie J, Jean C, Chen TH, Park S, Ueki R, Harper T, Chmara E, Myers J, Stoppacher R, Catanese C, Farley N, Leis E, DiAngelo C, Fry AM, Finelli L, Carvalho MG, Beall B, Moore M, Whitney C, Blau DM. Bacterial coinfections in lung tissue specimens from fatal cases of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) - United States, May-August 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1071–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kudva A, Scheller EV, Robinson KM, Crowe CR, Choi SM, Slight SR, Khader SA, Dubin PJ, Enelow RI, Kolls JK, Alcorn JF. Influenza A inhibits Th17-mediated host defense against bacterial pneumonia in mice. J Immunol. 2011;186:1666–1674. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker D, Prince A. Type I interferon response to extracellular bacteria in the airway epithelium. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:582–588. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker D, Martin FJ, Soong G, Harfenist BS, Aguilar JL, Ratner AJ, Fitzgerald KA, Schindler C, Prince A. Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA initiates type I interferon signaling in the respiratory tract. MBio. 2011;2:e00016–00011. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00016-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker D, Cohen TS, Alhede M, Harfenist BS, Martin FJ, Prince A. Induction of type I interferon signaling by Pseudomonas aeruginosa is diminished in cystic fibrosis epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46:6–13. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0080OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinman RM, Hemmi H. Dendritic cells: translating innate to adaptive immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;311:17–58. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32636-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker D, Prince A. Immunopathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus pulmonary infection. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34:281–297. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0291-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin FJ, Gomez MI, Wetzel DM, Memmi G, O’Seaghdha M, Soong G, Schindler C, Prince A. Staphylococcus aureus activates type I IFN signaling in mice and humans through the Xr repeated sequences of protein A. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1931–1939. doi: 10.1172/JCI35879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seo YJ, Hahm B. Type I interferon modulates the battle of host immune system against viruses. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2010;73:83–101. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(10)73004-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin FJ, Parker D, Harfenist BS, Soong G, Prince A. Participation of CD11c(+) leukocytes in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clearance from the lung. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1898–1904. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01299-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diep BA, Gill SR, Chang RF, Phan TH, Chen JH, Davidson MG, Lin F, Lin J, Carleton HA, Mongodin EF, Sensabaugh GF, Perdreau-Remington F. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2006;367:731–739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in correctional facilities---Georgia, California, and Texas, 2001-2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:992–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macia E, Ehrlich M, Massol R, Boucrot E, Brunner C, Kirchhausen T. Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev Cell. 2006;10:839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soong G, Muir A, Gomez MI, Waks J, Reddy B, Planet P, Singh PK, Kaneko Y, Wolfgang MC, Hsiao YS, Tong L, Prince A. Bacterial neuraminidase facilitates mucosal infection by participating in biofilm production. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2297–2305. doi: 10.1172/JCI27920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marie I, Durbin JE, Levy DE. Differential viral induction of distinct interferon-alpha genes by positive feedback through interferon regulatory factor-7. EMBO J. 1998;17:6660–6669. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Padovan E, Spagnoli GC, Ferrantini M, Heberer M. IFN-alpha2a induces IP-10/CXCL10 and MIG/CXCL9 production in monocyte-derived dendritic cells and enhances their capacity to attract and stimulate CD8+ effector T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:669–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haller O, Staeheli P, Kochs G. Interferon-induced Mx proteins in antiviral host defense. Biochimie. 2007;89:812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craven RR, Gao X, Allen IC, Gris D, Bubeck Wardenburg J, McElvania-Tekippe E, Ting JP, Duncan JA. Staphylococcus aureus alpha-hemolysin activates the NLRP3-inflammasome in human and mouse monocytic cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munoz-Planillo R, Franchi L, Miller LS, Nunez G. A critical role for hemolysins and bacterial lipoproteins in Staphylococcus aureus-induced activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome. J Immunol. 2009;183:3942–3948. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diep BA, Chan L, Tattevin P, Kajikawa O, Martin TR, Basuino L, Mai TT, Marbach H, Braughton KR, Whitney AR, Gardner DJ, Fan X, Tseng CW, Liu GY, Badiou C, Etienne J, Lina G, Matthay MA, DeLeo FR, Chambers HF. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes mediate Staphylococcus aureus Panton-Valentine leukocidin-induced lung inflammation and injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:5587–5592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912403107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Genestier AL, Michallet MC, Prevost G, Bellot G, Chalabreysse L, Peyrol S, Thivolet F, Etienne J, Lina G, Vallette FM, Vandenesch F, Genestier L. Staphylococcus aureus Panton-Valentine leukocidin directly targets mitochondria and induces Bax-independent apoptosis of human neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3117–3127. doi: 10.1172/JCI22684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soong G, Chun J, Parker D, Prince A. Staphylococcus aureus activation of caspase-1/calpain signaling mediates invasion through human keratinocytes. J Infect Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soong G, Martin FJ, Chun J, Cohen TS, Ahn DS, Prince A. Staphylococcus aureus protein A mediates invasion across airway epithelial cells through activation of RhoA GTPase signaling and proteolytic activity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:35891–35898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.295386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalez-Navajas JM, Lee J, David M, Raz E. Immunomodulatory functions of type I interferons. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:125–135. doi: 10.1038/nri3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yi AK, Tuetken R, Redford T, Waldschmidt M, Kirsch J, Krieg AM. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA activate leukocytes through the pH-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species. J Immunol. 1998;160:4755–4761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hacker H, Mischak H, Miethke T, Liptay S, Schmid R, Sparwasser T, Heeg K, Lipford GB, Wagner H. CpG-DNA-specific activation of antigen-presenting cells requires stress kinase activity and is preceded by non-specific endocytosis and endosomal maturation. EMBO J. 1998;17:6230–6240. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee J, Chuang TH, Redecke V, She L, Pitha PM, Carson DA, Raz E, Cottam HB. Molecular basis for the immunostimulatory activity of guanine nucleoside analogs: activation of Toll-like receptor 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6646–6651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631696100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomez MI, Lee A, Reddy B, Muir A, Soong G, Pitt A, Cheung A, Prince A. Staphylococcus aureus protein A induces airway epithelial inflammatory responses by activating TNFR1. Nat Med. 2004;10:842–848. doi: 10.1038/nm1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmitz F, Heit A, Guggemoos S, Krug A, Mages J, Schiemann M, Adler H, Drexler I, Haas T, Lang R, Wagner H. Interferon-regulatory-factor 1 controls Toll-like receptor 9-mediated IFN-beta production in myeloid dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:315–327. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yarilina A, Park-Min KH, Antoniv T, Hu X, Ivashkiv LB. TNF activates an IRF1-dependent autocrine loop leading to sustained expression of chemokines and STAT1-dependent type I interferon-response genes. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:378–387. doi: 10.1038/ni1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Kaisho T, Sato S, Sanjo H, Matsumoto M, Hoshino K, Wagner H, Takeda K, Akira S. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Medoff BD, Sauty A, Tager AM, Maclean JA, Smith RN, Mathew A, Dufour JH, Luster AD. IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 (CXCL10) contributes to airway hyperreactivity and airway inflammation in a mouse model of asthma. J Immunol. 2002;168:5278–5286. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Condon TV, Sawyer RT, Fenton MJ, Riches DW. Lung dendritic cells at the innate-adaptive immune interface. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90:883–895. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0311134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barbalat R, Ewald SE, Mouchess ML, Barton GM. Nucleic acid recognition by the innate immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:185–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolf AJ, Arruda A, Reyes CN, Kaplan AT, Shimada T, Shimada K, Arditi M, Liu G, Underhill DM. Phagosomal degradation increases TLR access to bacterial ligands and enhances macrophage sensitivity to bacteria. J Immunol. 2011;187:6002–6010. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gillrie MR, Zbytnuik L, McAvoy E, Kapadia R, Lee K, Waterhouse CC, Davis SP, Muruve DA, Kubes P, Ho M. Divergent roles of Toll-like receptor 2 in response to lipoteichoic acid and Staphylococcus aureus in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1639–1650. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmaler M, Jann NJ, Ferracin F, Landolt LZ, Biswas L, Gotz F, Landmann R. Lipoproteins in Staphylococcus aureus mediate inflammation by TLR2 and iron-dependent growth in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;182:7110–7118. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Aulock S, Morath S, Hareng L, Knapp S, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA, Hartung T. Lipoteichoic acid from Staphylococcus aureus is a potent stimulus for neutrophil recruitment. Immunobiology. 2003;208:413–422. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kebaier C, Chamberland RR, Allen IC, Gao X, Broglie PM, Hall JD, Jania C, Doerschuk CM, Tilley SL, Duncan JA. Staphylococcus aureus alpha-hemolysin mediates virulence in a murine model of severe pneumonia through activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:807–817. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Viala J, Chamaillard M, Labigne A, Thomas G, Philpott DJ, Sansonetti PJ. Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP) detection. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8869–8872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kapetanovic R, Nahori MA, Balloy V, Fitting C, Philpott DJ, Cavaillon JM, Adib-Conquy M. Contribution of phagocytosis and intracellular sensing for cytokine production by Staphylococcus aureus-activated macrophages. Infect Immun. 2007;75:830–837. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01199-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deshmukh HS, Hamburger JB, Ahn SH, McCafferty DG, Yang SR, Fowler VG., Jr. Critical role of NOD2 in regulating the immune response to Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1376–1382. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00940-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kapetanovic R, Jouvion G, Fitting C, Parlato M, Blanchet C, Huerre M, Cavaillon JM, Adib-Conquy M. Contribution of NOD2 to lung inflammation during Staphylococcus aureus-induced pneumonia. Microbes Infect. 2010;12:759–767. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Plitas G, Burt BM, Nguyen HM, Bamboat ZM, DeMatteo RP. Toll-like receptor 9 inhibition reduces mortality in polymicrobial sepsis. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1277–1283. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhan U, Lukacs NW, Osterholzer JJ, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Moore TA, McMillan TR, Krieg AM, Akira S, Standiford TJ. TLR9 is required for protective innate immunity in Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia: role of dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:3937–3946. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Albiger B, Dahlberg S, Sandgren A, Wartha F, Beiter K, Katsuragi H, Akira S, Normark S, Henriques-Normark B. Toll-like receptor 9 acts at an early stage in host defence against pneumococcal infection. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:633–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhan U, Trujillo G, Lyn-Kew K, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Hogaboam CM, Krieg AM, Standiford TJ. Toll-like receptor 9 regulates the lung macrophage phenotype and host immunity in murine pneumonia caused by Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2895–2904. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01489-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]