The yin-yang relationship between proliferation and differentiation is a fundamental tenet of development and plays a critical role in diseases such as cancer. Cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) are well-characterized drivers of the cell cycle; they have also been found to play a direct role in the regulation of genes not necessarily required for cell proliferation, and hence may be at the crux of this dichotomy. Cyclin D1, which increases in G1 and remains elevated throughout S phase, is the best-studied of the cyclins and is amplified or overexpressed in many tumors. The canonical role of cyclin D1 is to activate CDK4/6, which, in turn, phosphorylate, and inactivate, the tumor suppressor Rb. Rb suppresses tumor growth by inhibiting E2F, a transcription factor (TF) that drives the expression of genes required for DNA synthesis. Less well-known activities of cyclin D1 that do not directly result in proliferation are CDK-independent interaction with TFs (e.g., nuclear receptors), effects on co-activator function (e.g., p300 and CBP) and widespread recruitment to gene promoters.

In a recent issue of Cell Cycle, Hanse, et al.1 expand the list of cyclin D1-TF interactions with two important factors that regulate metabolism—carbohydrate response element binding protein (ChREBP) and hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 α (HNF4α). These interactions result in a decrease of expression of genes involved in glucose and lipid metabolism in hepatocytes: the net effect is a direct impact of cyclin D1 on metabolic homeostasis in the liver. This is of particular interest, since the liver not only is a major metabolic organ, but also has a remarkable proliferative capacity after partial hepatectomy or injury. The authors propose that after injury, the inhibition of expression of “luxury genes,” such as those regulated by ChREBP and HNF4α, may be required so that cell resources can be re-directed to the more urgent task of repopulating the liver, and hence the need for cyclin D1 to repress their activity. Furthermore, cyclin D1 inhibits ChREBP and HNF4α by different mechanisms, suggesting an even broader role for this cyclin in transcription regulation. Cyclin D1 decreases ChREBP gene transcription and protein function in a CDK-dependent fashion. In contrast, cyclin D1 does not alter the level of HNF4α RNA or protein but does prevent its recruitment to and activity on target gene promoters, albeit in a CDK-independent fashion.

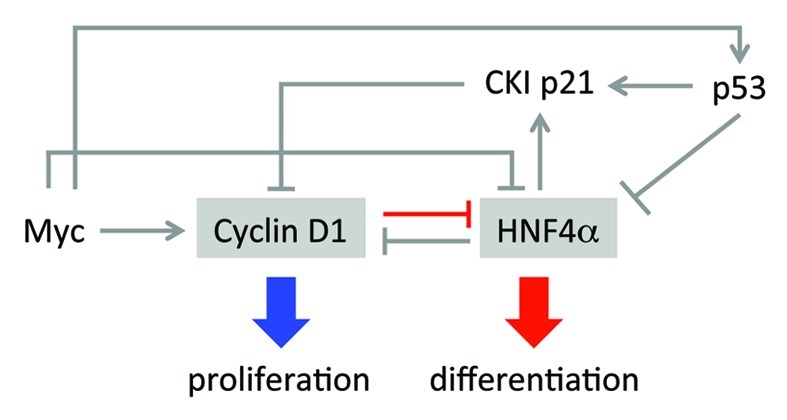

The action of cyclin D1 on HNF4α could have additional consequences. HNF4α, a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily, is one of the most abundant TFs in the adult liver and required for most liver-specific expression. It also acts as a tumor suppressor in the liver and directly inhibits cell proliferation.2-4 Cyclin D1 now joins a cadre of other key players in proliferation that downregulate or antagonize HNF4α (Fig. 1). The oncogene c-Myc, which upregulates the expression of the cyclin D1 gene (Ccnd1), has been shown to compete with HNF4α for control of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 gene (Cdkn1a).5 In contrast, HNF4a appears to downregulate the expression of Ccnd1 as a liver-specific knockout of HNF4a results in a marked increase in cyclin D1 gene expression.2 The tumor suppressor p53 has also been shown to inhibit HNF4a function and downregulate the expression of the HNF4A gene upon DNA damage;6,7 decreased HNF4α may help set the stage for subsequent regrowth. While p53 is best known for its ability to inhibit the cell cycle (via upregulation of Cdkn1a), its expression is also increased by oncogenes such as Myc. Therefore, c-Myc can ostensibly inhibit HNF4a activity via cyclin D1, p53 or direct interaction with HNF4α.5 Other pro-oncogenic factors that negatively affect HNF4a function include protein kinase C (PKC)8 and Src tyrosine kinase.9 While all of these factors (Myc, p53, PKC, Src) would be expected to cause a downregulation of HNF4α targets involved in differentiation, they will also result in an increase in proliferation by relieving the HNF4a-mediated repression of cyclin D1. Thus, cyclin D1 and HNF4α are at a nexus of a regulatory network that controls both proliferation and differentiation (Fig. 1). It will be of interest to determine whether ChREBP and other TFs inhibited by cyclin D1, especially those that drive differentiation, are part of this circuit.

Figure 1. Cyclin D1 and HNF4α are at the center of a complex circuit that coordinately regulates cellular proliferation and differentiation. HNF4α and cyclin D1 negatively regulate each other and are in turn regulated by other modulators of the cell cycle, such as Myc, CKI p21 and p53. Red line is from Hanse, et al.1

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/21721

References

- 1.Hanse EA, et al. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2681–90. doi: 10.4161/cc.21019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonzo JA, et al. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:7345–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.334599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatziapostolou M, et al. Cell. 2011;147:1233–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ning BF, et al. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7640–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hwang-Verslues WW, et al. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:78–90. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maeda Y, et al. Biochem J. 2006;400:303–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maeda Y, et al. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:402–10. doi: 10.1210/me.16.2.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun K, et al. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:1297–311. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chellappa K, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2302–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106799109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]