One of the initiating events of oncogenesis is tetraploidization, that is the generation of cells that contain twice as much DNA and chromosomes than their normal, diploid counterparts.1 Tetraploidy may arise through illicit cell-to-cell fusion among somatic cells,2 endomitosis3 or endoreplication.4 Tetraploidy has been observed in the early stages of cervical, colorectal, esophageal, ovary, mammary and other cancers.5,6 Tetraploid cells exhibit an enhanced fitness in the context of DNA damage,7 a property that may increase their survival during oncogenesis as well as after anticancer chemotherapies. In addition, tetraploid cells can undergo a subsequent depolyploidization cascade that ultimately results in rampant aneuploidy, due to multipolar divisions. Such multipolar division mostly leads to the death of daughter cells (due to lethal nullisomies or monosomies and/or desiquilibria in gene doses), yet occasionally yields cells that are fitter than their progenitors and can engage in progressive malignant transformation.1 Altogether, these phenomena yield the histopathological aspect of anisokaryosis, which is a snapshot of transformation and tumor progression that morphologically reflects genetic heterogeneity.

The aforementioned tetraploidization/depolyploidization cascade is controlled at multiple levels, and a large panel of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes can favor or inhibit the generation and survival of tetraploid cells as well as their depolyploidization.3,8 For example, the inactivation of the tumor suppressor proteins Tp53 and Rb have been correlated with the incidence of tetraploidy in human cancers.6 Moreover, the ectopic expression of the meiotic kinase Mos (which usually is only expressed during oocyte meiosis) in tetraploid tumor cells correlates with their propensity to undergo multipolar divisions.8 Based on these observations, it can be expected that only a combination of genetic events that are compatible with multistep carcinogenesis can facilitate the process of tetraploidization/depolyploidization that marks the transition from normal diploidy/euploidy to metastable tetraploidy and subsequent aneuploidy.

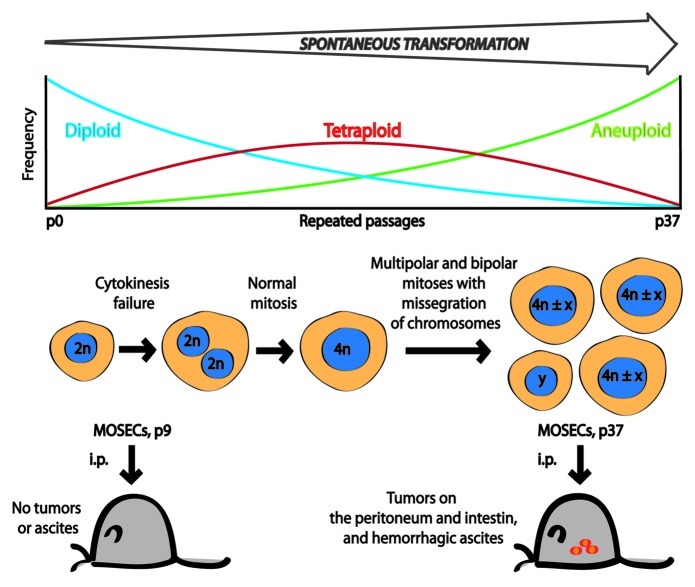

In a recent issue of Cell Cycle, Lv L, et al.9 revealed the surprising finding that long-term in vitro culture of mouse ovarian surface epithelial cells (MOSECs) is sufficient to generate cancer cells, that is cells that generate tumors upon inoculation into syngenic control mice (Fig. 1). In the course of their experiments, Lv, et al. discover that cultured MOSECs initially are diploid, yet progressively become tetraploid after repeated passaging. Videomicroscopic studies indicate that such tetraploid MOSECs arise from cytokinesis failure of bipolar mitosis in initially diploid cells. Later, tetraploid cells gave rise to aneuploid offspring through chromosomal missegregation during either bipolar or multipolar mitoses, as documented by a combination of long-term videomicroscopy and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) technology.9 Altogether, these data reveal that aging normal MOSECs in vitro, in the absence of any chemical carcinogens, can lead to their malignant transformation.

Figure 1. Tetraploidy in the malignant transformation of mouse ovarian surface epithelial cells (MOSECs). During the process of spontaneous transformation, the percentage of diploid (2 n) cells gradually decreased, while the fraction of tetraploid (4 n) cells increased, peaked at passage 19, then decreased with further passages in culture. At the same time, the frequency of aneuploid cells increased continuously until passage 37 (p37). Long-term live-cell imaging followed by FISH showed that cytokinesis failure is responsible for the generation of tetraploid cells and that most aneuploid cells derive from such tetraploids. When MOSECs from passage 9 were injected intraperitoneally into normal female C57BL/6 mice, no visible tumors or ascites were observed. In contrast, mice injected with late passage (p37) cells developed multiple tumors and had hemorrhagic ascites. (4 n ± x) and (y) represent near-tetraploid cells and other types of aneuploidy, respectively.

The molecular events that are compatible with the spontaneous malignant transformation of aging MOSECs are elusive. Primary breast epithelial cells only can undergo tetraploidization and subsequent malignant transformation if they are derived from p53−/− mice, presumably because the inactivation of p53 is a prerequisite of the generation or survival of tetraploid cells.3 Hence, it will be interesting to assess p53, as well as its upstream activators and downstream effectors in aging MOSECs. Aging primary fibroblasts undergo a “crisis” that results from progressive telomere shortening, followed by the reactivation of telomerase that is required for long-term proliferation. Since telomere attrition is a potent inducer of tetraploidization,6 it will also be interesting to assess the expression of telomerase in MOSECs as they evolve from normal diploid to malignant aneuploidy via a transient state of tetraploidy.

Beyond these molecular details, it will be important to understand whether the in vitro culture of MOSECs constitutes a general model of aging. As a fascinating prospect, cell-intrinsic perturbations in cell cycle control and genomic maintenance might favor the accumulation of potential cancer cell precursors, hence explaining the ever-increasing incidence of malignancy in aging. It is also possible that accumulating tetraploid cells contribute to the progressive dysfunction of aging tissues. If this were the case, pharmacological interventions aiming at the selective elimination of tetraploid cells might constitute dual hits in so far as they would not only reduce the incidence of cancers, but that they would also mediate a general antiaging effect.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/21722

References

- 1.Vitale I, et al. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1403–13. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duelli DM, et al. Curr Biol. 2007;17:431–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujiwara T, et al. Nature. 2005;437:1043–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davoli T, et al. Cell. 2010;141:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitale I, et al. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:385–92. doi: 10.1038/nrm3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davoli T, et al. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:585–610. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castedo M, et al. EMBO J. 2006;25:2584–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vitale I, et al. EMBO J. 2010;29:1272–84. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lv L, et al. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2864–75. doi: 10.4161/cc.21196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]