Cancer is a commonly diagnosed disease and the second leading cause of deaths in the U.S. Common diagnostic modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), and optical imaging have mixed results as a stand-alone system due to individual limitations such as low sensitivity, low spatial resolution, toxicity of contrast agents, and inaccurate diagnosis due to non-specific targeting of contrast agents to the cancer site.[1] Dual-/multi-modal imaging systems bearing the advantages of specific individual imaging modalities may overcome the limitations associated with the stand-alone systems.[2] For instance, MRI provides exceptional tissue contrast, penetration depth, and high spatial resolution, whereas fluorescence imaging provides extremely high sensitivity. Therefore, a dual-imaging modality combining MRI contrast and fluorescent agents will be able to diagnose cancers in early stage pre-operatively and intra-operatively with better accuracy.

To improve the diagnostic accuracy and reduce the significant side effects to normal healthy cells, site-specific targeting of imaging contrast agents is required.[3] Although passive delivery of nanoparticles through leaky tumor vasculature shows some success, active targeting strategies will add more specificity for cancer targeting.[4] Cell-selective nanoparticles specifically target and deliver the payloads to cancer cells, minimizing the side effects due to the delivery of payloads to healthy cells. Research on the development of cancer targeting nanoparticle systems has been focused mainly on conjugating antibodies, peptides, or aptamers for actively transporting nanoparticles to cancer cells. Other targeting strategies include magnetic targeting that aids in the nanoparticle accumulation at the targeted site under a magnetic field.[5] Herein, we report the development of dual-imaging enabled cancer-targeting nanoparticles (DICT-NPs), without using targeting ligands, based on a breakthrough development of biodegradable photoluminescent polymers[6] and superparamagnetic iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanoparticles.

Dual-imaging nanoparticles have gained significant attention in recent years. Examples include rhodamine/FITC-labeled paramagnetic nanoparticles,[7] DiI/DiR-polyacrylic acid-coated iron oxide nanoparticles,[8] quantum dot-coated iron oxide nanoparticles,[9] and Cy5.5-labeled PEG/chitosan-coated iron oxide nanoparticles.[10, 11] However, the fluorescent tags used in these systems are known to either be toxic or display photobleaching. Moreover, incorporating imaging agents in nanoparticles may result in increased particle sizes, added complexity, and higher risk of adverse biological reactions. We have recently developed water-soluble and water-insoluble biodegradable photoluminescent polymers (WBPLP and BPLP, respectively), which do not contain photobleaching organic dyes and cytotoxic quantum dots.[6] The degradability of the polymers and the superior photoluminescent properties such as high quantum yield, photobleaching resistance, and tunable emission up to near infrared area, makes them unique. BPLPs have demonstrated excellent biocompatibility and great potential for bioimaging both in vitro and in vivo.[6] Along with the development of BPLPs, we have also developed a series of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm)-coated magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) for controlled and targeted drug delivery.[12, 13] In addition to their use as contrast agents for MRI, MNPs have also been used as carriers to deliver, recruit, and retain therapeutic agents to specific disease sites where rapid clearance of particles by the mononuclear phagocytes can be avoided by applying an external magnetic field.[14, 15] Moreover, MNPs have also shown some success in cancer treatment through hyperthermia, as they can be used to provide an induced heat locally under an oscillating magnetic field.[15, 16]

Taken together, the aim of this work is to develop dual-imaging nanoparticles with magnetic targeting capabilities. The rationales behind WBPLP-conjugated MNPs (WBPLP-MNPs) and BPLP-conjugated MNPs (BPLP-MNPs) are that: 1) DICT-NPs provide dual-imaging capability, through which WBPLP/BPLP enables fluorescence imaging while MNPs are capable of negative contrast agents for MRI; 2) DICT-NPs could also provide dual-targeting capability, through magnetic targeting and receptor-mediated targeting if active targeting ligands such as antibodies are conjugated; 3) DICT-NPs are fully degradable, thus eliminating long-term toxicity concerns. We have demonstrated the degradability and biocompatibility of BPLP both in vitro and in vivo.[6] Iron oxide MNPs are also known to be non-toxic at a low dose and approved by the FDA as contrast agents (a dose of 45 μmole Fe kg−1 is recommended for human use).[17–19] Degradable DICT-NPs address the particle sizes and in vivo clearance concerns in the traditional design of tumor-targeting nanoparticles using non-degradable materials where the diameter of nanoparticles should be limited to ~5.5 nm for rapid renal excretion.[20] 4) DICT-NPs can act as a drug carrier for controlled drug delivery as many other polymer-based nanoparticle drug delivery systems.

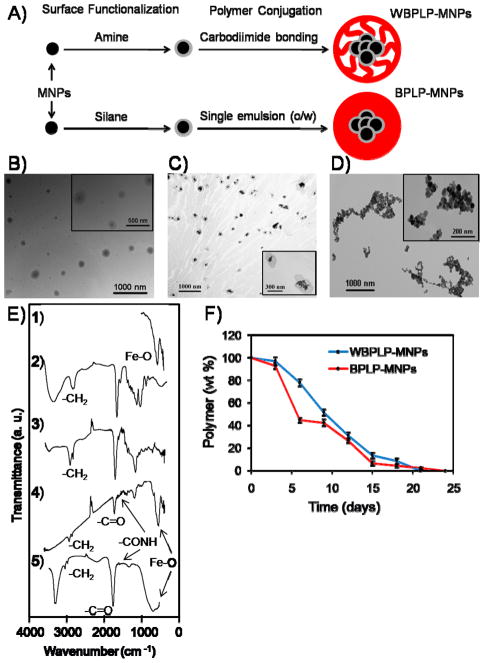

Polymer-coated MNP structures using various types of polymers have been extensively developed and investigated for cancer imaging and treatment.[12, 13, 21, 22] Herein, we demonstrated WBPLP-/BPLP-conjugated MNP structures of the DICT-NPs. Figure 1A shows schematic representation of WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs. As shown in Figure 1B and 1C, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images (insets) show a spherical morphology of the nanoparticles. Approximately, 110 and 130 MNPs were present in the darker area of one nanoparticle. These numbers were determined by dividing the volume of darker area of a nanoparticle by the volume of a bare MNP, considering 25% void space among MNPs. The presence of Fe3O4 in the darker area was confirmed via energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis (Supporting Information, Figure S1). Figure 1D is a TEM image of bare MNPs that tend to aggregate in the absence of any polymer coatings. As determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements in DI water and cell culture media containing 10% serum, hydrodynamic diameter of WBPLP-MNPs (238 nm and 236 nm) and BPLP-MNPs (235 nm and 229 nm), respectively, did not vary irrespective of the solvent (Supporting Information, Table S1). The polydispersity index (PDI) of WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs in both the solvents was in mid-range polydispersity (0.08 – 0.7).[23] The nanoparticle size and PDI were also measured over a period of nine days in the culture medium to validate the stability of the nanoparticles. The nanoparticles were stable and did not aggregate as observed from the size and PDI readings (Supporting Information, Figure S2). The larger size of nanoparticles is usually associated with rapid clearance of nanoparticles by reticulo-endothelial system (RES). However, our nanoparticles are fully degradable and can be administered locally, following magnetic targeting to quickly recruit the nanoparticles to the target site. In addition, after the nanoparticle formulation, DICT-NPs can be filtered using 0.2 micron filter to collect approximately 100 nm sized particles (Supporting Information, Table S1). Further, surface charge on the WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs was −25.85 mV and −31.32 mV, respectively, as determined by zeta potential analyzer. The nanoparticle surface charge was changed from −5.13 mV for bare MNPs to −25.85 or −31.32 mV for DICT-NPs. The increase in surface charge suggests that the stability of the nanoparticles increased after coating. However, in the cell culture media, the zeta potential of WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs reduced to −16.19 mV and −12.09 mV. The change in zeta potential results from the serum present in the media.[24] Although the zeta potential of nanoparticles reduced in culture medium, they were still stable and did not aggregate due to electrostatic repulsion among the negatively charged polymer coatings.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematics of WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs showing formulation process. TEM image of (B) WBPLP-MNPs (avg. size 220 nm), (C) BPLP-MNPs (avg. size 212 nm), and (D) bare MNPs (avg. size 10 nm). (E) FTIR spectra of (1) iron oxide nanoparticles, (2) WBPLP, (3) BPLP, (4) WBPLP-MNPs, and (5) BPLP-MNPs. (F) Degradation profiles of WBPLP and BPLP coatings on MNPs showing complete degradation in 3 weeks.

Chemical structures of the nanoparticles were characterized using Fourier transform infra-red spectrophotometer (FTIR), which showed the characteristic peaks of Fe-O at 550 cm−1, –CH2 from polymer backbone at 2919 cm−1, –C=O from citric acid at 1707 cm−1, and –C(=O)NH between polymer and amino acid at 1550 cm−1 (Figure 1E). These findings were in agreement with our previous observations confirming the presence of MNPs[12] and all the corresponding bonds from WBPLP/BPLP coating.[6] Further, degradation of the polymer coating on MNPs in DI water was studied over time. It was observed that the WBPLP and BPLP coating was degraded completely within 21 and 24 days, (Figure 1F) respectively, which was in agreement with our previous study on pure BPLP degradation.[6] BPLPs underwent hydrolysis and degraded into their monomeric units including PEG or octanediol, citric acid, and amino acids. There was a faster degradation of BPLP than WBPLP within initial five days, which can be attributed the loose binding of BPLP over MNP surfaces during the emulsion process, compared to covalent binding of WBPLP to MNPs during carbodiimide binding.

The nanoparticles possess strong superparamagnetic properties. WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs were comprised of approximately 75% and 80% mass of iron, respectively (Supporting Information, Table S2). Further, in the absence of an external magnet, nanoparticles were suspended and well-dispersed in water (Figures 2A.1 and 2B.1). While in the presence of an external magnet, nanoparticles concentrated toward the magnet (Figures 2A.2-3 and 2B.2-3), demonstrating the recruitment of nanoparticles via magnetic targeting. Moreover, the saturation magnetization of the WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs (51.42 and 52.04 emu g−1, respectively) was lower than that of bare MNPs (57.88 emu g−1) (Figure 2C and Supporting Information, Table S2). This decrease in the saturation magnetization is due to the presence of polymer coating on the surface of MNPs, which also increased response time of nanoparticles when placed in the magnetic field. A decrease in the saturation magnetization and an increase in the response time would decrease the aggregation of nanoparticles and increase the required external magnetic field to guide the nanoparticle movement. It was frequently observed that there was a decrease in saturation magnetization when MNPs were coated with various polymers such as polystyrene,[25] PNIPAAm,[12] PLGA,[21] and PEG.[22] The remanence of WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs was 5.14 and 5.77 (Mr Ms−1), respectively, as compared to 6.73 (Mr Ms−1) in the case of bare MNPs. Whereas, the coercivity of WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs was 50.59 and 59.72 Oe, respectively, as compared to 65.23 Oe in the case of bare MNPs (Supporting Information, Table S2). There was an increase in the coercivity of the DICT-NPs due to increased particle size and separation distance as a result of polymer coating on the surface of the MNPs. This data suggest that all the samples contain a fraction of nanoparticles in a blocked magnetic (superparamagnetic) state, which has low coercive forces, small remanent magnetic induction, and long and narrow hysteresis loops.[26]

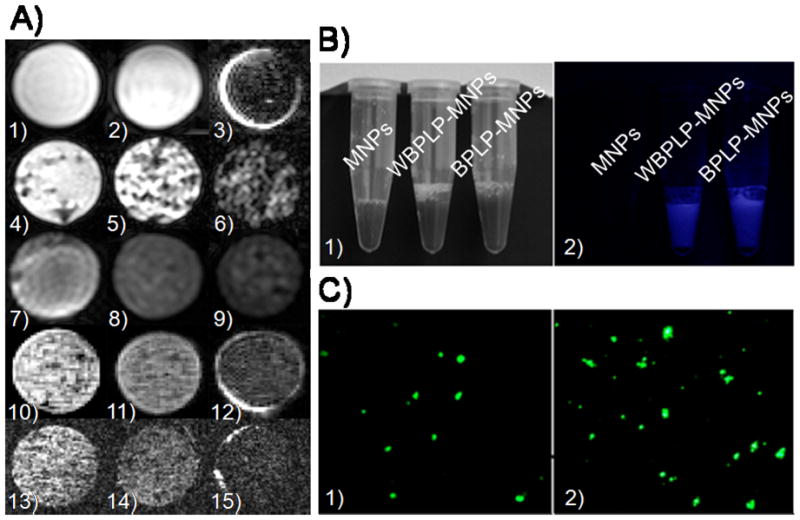

Figure 2.

Photographs of (A) WBPLP-MNPs and (B) BPLP-MNPs showing (1) nanoparticle suspension and (2), (3) recruitment of nanoparticles in the magnetic field (1.3 T) generated by a magnet. (C) Magnetization hysteresis loops of nanoparticles showing superparamagnetic behavior.

The DICT-NPs were also tested as contrast agents for MRI. MRI was carried out on agarose phantoms containing either DICT-NPs alone or DICT-NPs uptaken by PC3 prostate cancer cells. A dark and dispersed negative contrast was observed from the samples containing DICT-NPs, even at a low concentration of 100 μg iron ml−1 (Figure 3A.4 and 3A.10). The negative contrast was nanoparticle dose-dependent (Figure 3A.4-6 and 3A.10-12), which was also confirmed from the relative signal intensities of the samples. For example, there was 12% (Figure 3A4), 56% (Figure 3A5), and 92% (Figure 3A6) drop in the signal intensity compared to the control (Figure 3A1). Control samples consisting of BPLP nanoparticles without MNPs (Figure 3A.1) and PC3 cells alone (Figure 3A.2) did not generate a contrast, but bare MNPs produced a very dark negative contrast (Figure 3A.3). These results suggest that the contrast generated in MRI is only due to the presence of MNPs in DICT-NPs. When the nanoparticles were uptaken by the cells, the MRI contrast was dark and even more dispersed than those of DICT-NPs only (Figure 3A.7-9 and 3A.13-15). The negative contrast was dependent on the number of nanoparticles uptaken by the different concentrations of cells, which suggests that these nanoparticles produce a dark, well-dispersed MRI contrast even at a low number (10,000) of cells. Pinkernelle et al.[27] observed similar results about the effects of nanoparticle concentration and cell number on MRI signal when iron oxide nanoparticles were incubated with human colon carcinoma cells. The difference between the MRI contrast signal dispersion between samples with and without the cells might be due to a reduction in nanoparticle aggregation because of cellular uptake producing a more dispersed contrast than that of nanoparticles only. We have previously observed a dark and dispersed MRI contrast signal from our thermo-sensitive polymer-coated MNPs uptaken by JHU31 cells.[13] Some other groups have also reported a dark negative MRI contrast signal from their iron oxide-based nanoparticles.[23, 27] Although, MRI has the advantages of exceptional tissue contrast and spatial resolution and has been widely used in clinical settings,[1] similar to CT and PET, the MRI imaging technique is also insensitive for the small lesions.[28]

Figure 3.

(A) MR images of agarose phantoms containing (1) 5 mg ml−1 BPLP nanoparticles, (2) 104 PC3 cells, and (3) 0.1 mg ml−1 MNPs as control samples. Experimental agarose phantoms contain (4) WBPLP-MNPs of 0.1 mg ml−1, (5) 0.3 mg ml−1, and (6) 0.6 mg ml−1 concentrations; (7) 0.3 mg ml−1 WBPLP-MNPs uptaken by 104, (8) 106, and (9) 5×106 PC3 cells; similarly (10) BPLP-MNPs of 0.1 mg ml−1, (11) 0.3 mg ml−1, and (12) 0.6 mg ml−1 concentrations; and (13) 0.3 mg ml−1 BPLP-MNPs uptaken by 104, (14) 106, and (15) 5×106 PC3 cells. (B) Photographs of nanoparticles suspensions in (1) white light and (2) UV light. Fluorescence from WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs was observed in UV light only. (C) Photomicrographs of fluorescence observed from (1) WBPLP-MNPs and (2) BPLP-MNPs under an enhanced optical microscope at 400× magnification.

To overcome the limitations of conventional imaging techniques, the optical imaging approach has been investigated. Although optical fluorescence imaging has a potential to detect tiny tumor masses with a high sensitivity,[29] its applications in vivo are hampered by a limited tissue penetration depth, high (or presence of) tissue auto-fluorescence, and lack of anatomic resolution and spatial information.[30] Therefore, the combination of MRI and optical imaging techniques may improve the identification of small cancer lesions to optimize the localized therapy. In the past, dual-functional imaging nanoparticles have been generated by linking MNPs with quantum dots and/or Cy5.5 dyes, so that they can be detectable by both fluorescence imaging and MRI.[2, 31] The polymer coating of our DICT-NPs itself can act as biodegradable imaging probes for targeted imaging. Moreover, BPLPs can be excited and emitted at different wavelengths ranging from UV to near infra-red. Fluorescence properties of WBPLP and BPLP coatings on MNPs were tested under UV light and an enhanced optical fluorescent microscope. Figure 3B.1 shows the samples under white light and Figure 3B.2 shows a bright fluorescence from WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs under UV light. There was no fluorescence observed from bare MNPs under UV light due to the absence of fluorescent polymer coating on the MNPs. Moreover, the nanoparticles exhibited their bright fluorescence observed by the enhanced optical fluorescent microscope (Figures 3C.1-2). Our findings on both optical and MRI studies suggest that these nanoparticles could be used as dual-imaging (optical and MRI) agents.

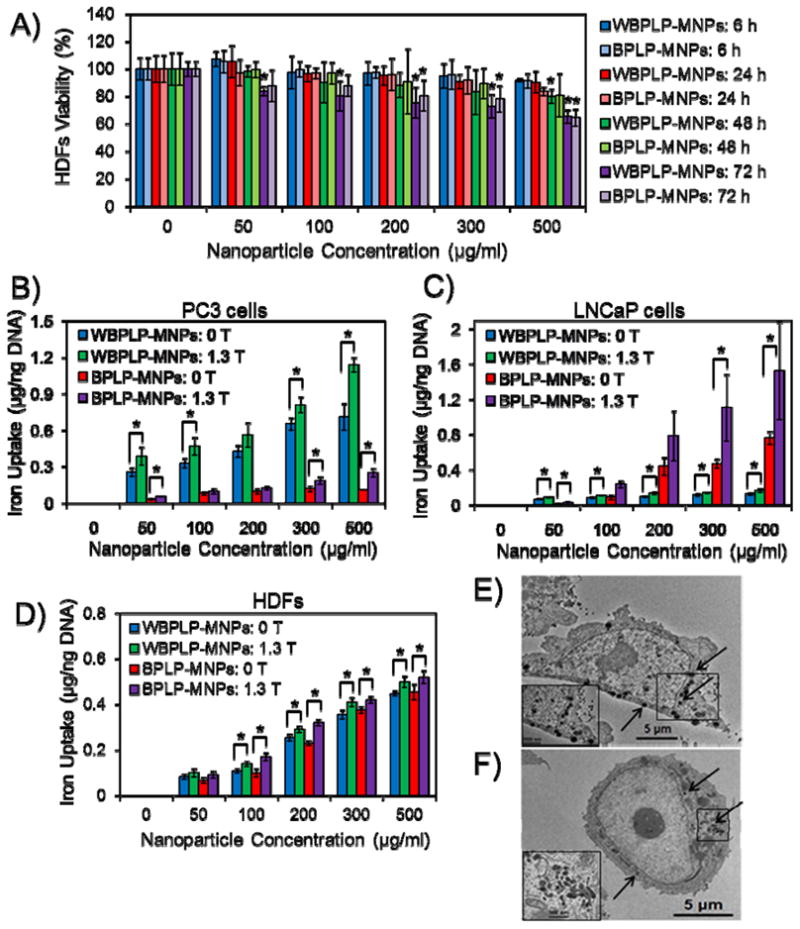

The cytotoxicity results of the DICT-NPs are presented in Figure 4A. The nanoparticles were cytocompatible and did not show a significant decrease in cell survival when human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) were exposed to nanoparticles with concentrations up to 500 μg ml−1 till 48 hours of exposure. However, cell viability decreased significantly at nanoparticle concentrations higher than 500 μg ml−1 after 72 hours of exposure. Moreover, BPLP-MNPs were more cytocompatible than WBPLP-MNPs, especially at longer incubation periods. Thus, DICT-NPs may potentially eliminate the long-term in vivo toxicity concern and bypass the size limitation for in vivo clearance as the particles will be degraded and cleared by the body. BPLPs have previously demonstrated their excellent cytocompatibility in vitro when cultured with 3T3 fibroblasts and tissue-compatibility when implanted in rats.[6] Other studies have reported that there was a significant increase in the cytocompatibility of MNPs when they were coated with polymers such as Pluronics[23] or PNIPAAm/copolymers.[13] The above cytocompatibility evaluation further supported the potential of these nanoparticles for biomedical uses.

Figure 4.

(A) Cytotoxicity of nanoparticles on HDFs. BPLP-MNPs are more cytocompatible than WBPLP-MNPs, especially at longer incubation periods (* p < 0.05 compared to control). (B) Cancer-selective, dose-dependent, and magnetic field (1.3 T) dependent cellular uptake of nanoparticles showing higher uptake of WBPLP-MNPs by PC3 (PSMA− and highly metastatic) cells, whereas (C) BPLP-MNPs by LNCaP (PSMA+ and less metastatic) cells. (D) Control experiment of nanoparticle uptake by HDFs showing a low iron uptake and no significant difference between WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs (* p < 0.05). (E) TEM images of higher uptake of WBPLP-MNPs, whereas (F) least uptake of BPLP-MNPs by PC3 cells (insets show magnified images of the boxed areas in cells and arrows indicate location of nanoparticles in the cytoplasm).

A cancer cell-selective, dose- and magnetic field-dependent uptake of DICT-NPs by prostate cancer cells (PC3 and LNCaP cells) are shown in Figures 4B and 4C. The cellular uptake of nanoparticles was saturated at 300 μg ml−1, which can be attributed to the exocytosis of nanoparticles at higher concentrations by the cells.[32] Previously, we have reported that the uptake of our thermo-responsive polymer-coated MNPs by JHU31 prostate cancer cells was dose-dependent and reached a plateau at 300 μg ml−1 concentration of nanoparticles.[13] The uptake is dependent on various factors such as particle size, concentration, incubation time, and surface charge.[33, 34] Moreover, in the presence of an external magnetic field of 1.3 T, the cellular uptake of nanoparticles increased significantly and did not saturate until 500 μg ml−1 concentration of nanoparticles. These results suggest that the presence of a magnetic field reinforces the cellular uptake of DICT-NPs, which will be useful in delivering higher amounts of imaging or therapeutic agents to cancer cells via magnetic targeting.

It is very interesting that WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs exhibited cellular uptake selectivity. As observed in Figure 4C, BPLP-MNPs showed significantly higher uptake by LNCaP cells (PSMA+ and less metastatic) than WBPLP-MNPs. While in the case of PC3 cells (PSMA− and highly metastatic),[35] WBPLP-MNPs were uptaken significantly higher than BPLP-MNPs (Figure 4B). Whereas in a control experiment, relatively low and equal amounts of WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs were uptaken by healthy HDFs (Figure 4D). The results of nanoparticle uptake by PC3 cells were reconfirmed by TEM analysis. It was clearly shown (Figure 4E and 4F) that WBPLP-MNPs (hydrophilic) were present in the cytoplasm of PC3 cells in a greater number (~35 vs. ~15) than BPLP-MNPs (hydrophobic). The number of nanoparticles in the cytoplasm was calculated by visual observation on at least 20 cells. Inserts in Figure 4E and 4F show magnified images of the presence of nanoparticles in the cytoplasm. The difference in the nanoparticle uptake by two different cancer cell lines may be due to the effects of hydrophilicity levels of polymers and different metabolic mechanisms of different cells. It can also be attributed to the different cell surface antigens on different cells and their interactions with biomaterials. Hydrophobic BPLP-MNPs have been uptaken more by PSMA+ cells (LNCaP) while hydrophilic WBPLP-MNPs by highly metastatic cells (PC3[35]), making both types of nanoparticles relatively specific for a particular prostate cancer cell line. Thus, by varying and balancing the hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity of monomers in BPLP syntheses, suitable DICT-NPs can potentially be made for targeting prostate cancer cells at different stages of cancer, especially metastatic versus non-metastatic stages. Few groups have reported the effects of hydrophilicity levels of biomaterials on cellular uptake. For an instance, Nam et al.[36] observed an enhanced distribution of hydrophobically modified glycol chitosan nanoparticles in HeLa cells compared to hydrophilic glycol chitosan nanoparticles. Moreover, Sunshine et al.[37] found that polymers containing hydrophobic backbone promoted transfection of COS-7 cells compared to that of hydrophilic backbone. On the contrary, Gaumet et al.[38] observed more hydrophilic chitosan-coated PLGA nanoparticles in cells compared to PLGA nanoparticles alone. These observations reveal that the intracellular fate of nanoparticles is not only dependent on hydrophilicity levels of a polymer, but also on many factors including cell type, cell surface antigens, charge on the biomaterial, chemical functionality of polymers,[39] and so on. The detailed studies on cellular uptake by various prostate cancer cell lines will be our future focus.

In summary, we successfully synthesized and characterized fully biodegradable DICT-NPs with magnetic targeting and dual-imaging (optical imaging and MRI) capabilities in a single setting without using exogenous fluorescent organic dyes or quantum dots. DICT-NPs eliminate long-term toxicity concerns and bypass the size limitations for in vivo clearance in the traditional nanoparticle designs. We demonstrated that the magnetic properties of MNPs were preserved after WBPLP and BPLP conjugation. Dual-imaging studies revealed that DICT-NPs are capable of both optical and MR imaging. Moreover, these nanoparticles exhibited interesting cancer cell selectivity for cellular uptake. Our future work includes detailed studies on understanding the cellular selectivity of WBPLP-MNPs and BPLP-MNPs.

Experimental Section

Material and Cell Culture

Materials were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), if not specified, and used without further purification. HDFs (Invitrogen, CA) up to passage 10 were cultured in DMEM supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS 10%, Atlanta Biologicals, GA) and penicillin-streptomycin (PS 1%, Invitrogen). Prostate cancer cell lines, PC3 and LNCaP (ATCC, VA) were cultured in RPMI (Invitrogen) supplemented with FBS and PS.

Synthesis of Nanoparticles

The surface of iron oxide nanoparticles (MNPs, Meliorum Tech, NY) was functionalized with 3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (APTMS, template for synthesizing WBPLP-MNPs) or vinyltrimethoxysilane (VTMS, template for synthesizing BPLP-MNPs) as described elsewhere[12] (see Supporting Information for details). WBPLP and BPLP were synthesized using PEG or 1-8 octane diol, citric acid, and amino acids such as L-cysteine and serene following our previously developed protocols.[6] Further, WBPLP was conjugated on the surface of MNPs using carbodiimide chemistry.[13] In brief, two separate solutions of WBPLP (250 mg) and APTMS-functionalized MNPs (20 mg) were prepared in MES buffer (pH 5.6). EDC and NHS (1:1) were added to the polymer solution to activate the carboxyl groups on the WBPLP and the reaction was stirred for one hour. The APTMS-functionalized MNPs were then added to this solution and sonicated for five minutes at 40 W. The surfactant sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, 14 mg) was added to the reaction and sonicated for another two minutes. Finally, the particle suspension was allowed to react while stirring for six hours. The WBPLP-MNPs were then washed multiple times with DI water and collected using an external magnet. Finally, to synthesize BPLP-MNPs, single emulsion method was followed by which VTMS-functionalized MNPs were physically entrapped in BPLP shell. Briefly, VTMS-functionalized MNPs (10 mg) and BPLP (125 mg) were dispersed in 1,4-dioxane (2.5 ml) to form oil phase. An aqueous solution of SDS (16 mg ml−1) was prepared to form water phase. Oil phase was then added drop-wise to water phase, and the solution was emulsified by sonicating for five minutes at 40 W. The BPLP-MNPs were then washed multiple times with DI water and collected using an external magnet.

Material Characterization

The size of the DICT-NPs was determined using TEM (JEOL 1200 EX Electron Microscope). A hydrodynamic mean diameter, polydispersity index, and surface charge of the nanoparticles were obtained using zeta potential analyzer with a DLS detector (ZetaPALS, Brookhaven Instruments, NY). Further, chemical characterization of the nanoparticles was performed using EDS (S-3000N, VP-SEM, Hitachi) and FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet-6700, Thermo Fisher Scientific). To study the degradation of the polymer shell, nanoparticles were suspended in DI water. At each time point, dry weight of nanoparticles was recorded. After the measurement, nanoparticles were resuspended in DI water for the next time point. A relative percentage of dry weights of the nanoparticles at all the time points were calculated with respect to the initial dry weight of the nanoparticles. Further, the amount of iron in the nanoparticles was determined by iron content assays, as described elsewhere[17] (see Supporting Information for details). Moreover, a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID, Quantum Design, CA) was used to evaluate the magnetic properties of the nanoparticles.[12] The nanoparticles were trapped in epoxy gel (Loctite Corp, CT) and allowed to dry for five minutes. The dried samples were then mounted in transparent drinking straw and magnetic hysteresis loops were obtained.

Dual-imaging Experiments

Agarose platforms were prepared for MRI by dissolving agarose (1% w/v) in DI water. Two types of samples were prepared by dispersing DICT-NPs only and DICT-NPs uptaken by PC3 cells at different concentrations in agarose phantoms. The control samples were prepared by dispersing bare MNPs, BPLP nanoparticles (without MNPs), and PC3 cells only in agarose phantoms. In brief, to prepare cell based phantoms, PC3 cells were incubated with nanoparticles (300 μg ml−1) for two hours. The cells were then washed with PBS and trypsinized to get a cell pellet. The PC3 cells labeled with nanoparticles were added to the agarose solution to get the desired concentrations. MR images and their signal intensities were obtained as previously described[13] (see Supporting Information for details). Further, the fluorescence of the nanoparticles from the polymer coating on the MNPs was observed under an enhanced optical fluorescent microscope (Cytoviva, Olympus, PA). Moreover, the fluorescence from the nanoparticles was also observed in UV light and compared against white light.

In Vitro Cell Studies

The cytotoxic effects of nanoparticles were tested on HDFs survival. Nanoparticles were sterilized in UV light for 30 minutes, suspended in cell medium, and then incubated with the cells for 6, 24, 48, and 72 hours. Cells exposed to nanoparticle free medium served as control. Cell survival was then determined using colorimetric MTS assays (CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega, WI) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Further, to determine the cellular uptake of nanoparticles, PC3 and LNCaP cells were seeded at a density of 10,000 cells/well in 48-well plates and allowed to attach and grow for 24 hours. Nanoparticles were sterilized, suspended in cell medium, and incubated with the cells for a predetermined period. Cells were washed thoroughly with PBS to wash away nanoparticles that are not engulfed by the cells. Cells were then lysed with 1% Triton in PBS. To determine the amount of iron (Fe) uptake, iron content assay was performed as described earlier. A part of the cell lysate was tested for the DNA content using a Picogreen DNA Assay (Invitrogen, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions, and this data was used to normalize the iron content. Cellular uptake of nanoparticles by PC3 cells was also visualized by TEM. Specimen for TEM were prepared as described elsewhere[36] (see Supporting Information for details).

Statistical Analysis

Results were analyzed using ANOVA with post hoc comparisons and t tests with P < 0.05. The sample size was four for all the studies except SQUID and MRI. The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Defense (DOD W81XWH-09-1-0313), the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT RP110412), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB R21EB009795 and R01EB012575), and the National Science Foundation (NSF CAREER award 0954109).

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Aniket S. Wadajkar, Department of Bioengineering, The University of Texas at Arlington, 500 UTA Boulevard, Arlington 76019, TX, USA. Joint Biomedical Engineering Program, The University of Texas at Arlington and The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Dallas 75390, TX, USA

Tejaswi Kadapure, Department of Bioengineering, The University of Texas at Arlington, 500 UTA Boulevard, Arlington 76019, TX, USA. Joint Biomedical Engineering Program, The University of Texas at Arlington and The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Dallas 75390, TX, USA.

Yi Zhang, Department of Bioengineering, The University of Texas at Arlington, 500 UTA Boulevard, Arlington 76019, TX, USA. Joint Biomedical Engineering Program, The University of Texas at Arlington and The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Dallas 75390, TX, USA.

Dr. Weina Cui, Department of Radiology, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Dallas 75390, TX, USA

Dr. Kytai T. Nguyen, Email: knguyen@uta.edu, Department of Bioengineering, The University of Texas at Arlington, 500 UTA Boulevard, Arlington 76019, TX, USA. Joint Biomedical Engineering Program, The University of Texas at Arlington and The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Dallas 75390, TX, USA

Dr. Jian Yang, Email: jianyang@uta.edu, Department of Bioengineering, The University of Texas at Arlington, 500 UTA Boulevard, Arlington 76019, TX, USA. Joint Biomedical Engineering Program, The University of Texas at Arlington and The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Dallas 75390, TX, USA

References

- 1.Puech P, Huglo D, Petyt G, Lemaitre L, Villers A. Curr Opin Urol. 2009;19:168. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e328323f5ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schellenberger EA, Sosnovik D, Weissleder R, Josephson L. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15:1062. doi: 10.1021/bc049905i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raghavan D, Koczwara B, Javle M. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:566. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brannon-Peppas L, Blanchette JO. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:1649. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun C, Lee JS, Zhang M. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1252. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang J, Zhang Y, Gautam S, Liu L, Dey J, Chen W, Mason RP, Serrano CA, Schug KA, Tang L. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:10086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900004106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmieder AH, Caruthers SD, Zhang H, Williams TA, Robertson JD, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. FASEB J. 2008;22:4179. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-112060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santra S, Kaittanis C, Grimm J, Perez JM. Small. 2009;5:1862. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu H, Zheng R, Zhang X, Xu B. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5664. doi: 10.1021/ja0496423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veiseh O, Sun C, Fang C, Bhattarai N, Gunn J, Kievit F, Du K, Pullar B, Lee D, Ellenbogen RG, Olson J, Zhang M. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6200. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee CM, Jeong HJ, Cheong SJ, Kim EM, Kim DW, Lim ST, Sohn MH. Pharm Res. 2010;27:712. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahimi M, Yousef M, Cheng Y, Meletis EI, Eberhart RC, Nguyen K. Journal of nanoscience and nanotechnology. 2009;9:4128. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2009.m21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahimi M, Wadajkar A, Subramanian K, Yousef M, Cui W, Hsieh JT, Nguyen KT. Nanomedicine. 2010;6:672. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanco E, Kessinger CW, Sumer BD, Gao J. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2009;234:123. doi: 10.3181/0808-MR-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahoo SK, Ma W, Labhasetwar V. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:335. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hattori Y, Ding WX, Maitani Y. J Control Release. 2007;120:122. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta AK, Gupta M. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1565. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta AK, Gupta M. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3995. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawai N, Futakuchi M, Yoshida T, Ito A, Sato S, Naiki T, Honda H, Shirai T, Kohri K. Prostate. 2008;68:784. doi: 10.1002/pros.20740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi HS, Liu W, Liu F, Nasr K, Misra P, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5:42. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pouponneau P, Leroux J, Martel S. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6327. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koneracka M, Zavisova V, Timko M, Kopcansky P, Tomasovicova N, Csach K. Acta Physica Polonica A. 2008;113:595. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/20/20/204151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin JJ, Chen JS, Huang SJ, Ko JH, Wang YM, Chen TL, Wang LF. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5114. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen ZP, Zhang Y, Xu K, Xu RZ, Liu JW, Gu N. Journal of nanoscience and nanotechnology. 2008;8:6260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramirez LP, Landfester K. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics. 2003;204:22. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bao H, Chen Z, Lin K, Wu P, Liu J. Materials Letters. 2006;60:2167. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinkernelle J, Teichgräber U, Neumann F, Lehmkuhl L, Ricke J, Scholz R, Jordan A, Bruhn H. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:1187. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Saylor M, Wen S, Silva MD, Rolfe M, Bolen J, Muir C, Reimer C, Chandra S. Mol Imaging Biol. 2006;8:300. doi: 10.1007/s11307-006-0052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao X, Cui Y, Levenson RM, Chung LW, Nie S. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:969. doi: 10.1038/nbt994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu L, Zhang J, Su X, Mason RP. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2008;4:524. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2008.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nie S, Xing Y, Kim GJ, Simons JW. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2007;9:257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.152025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrati S, Mack A, Chiappini C, Liu X, Bean AJ, Ferrari M, Serda RE. Nanoscale. 2010;2:1512. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00227e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Villanueva A, Canete M, Roca AG, Calero M, Veintemillas-Verdaguer S, Serna CJ, Morales Mdel P, Miranda R. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:115103. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/11/115103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen S, Liu Y, Huang P, Wang J. Journal of nanoscience and nanotechnology. 2009;9:2866. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2009.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pulukuri SM, Gondi CS, Lakka SS, Jutla A, Estes N, Gujrati M, Rao JS. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503111200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36.Nam HY, Kwon SM, Chung H, Lee SY, Kwon SH, Jeon H, Kim Y, Park JH, Kim J, Her S, Oh YK, Kwon IC, Kim K, Jeong SY. J Control Release. 2009;135:259. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sunshine JC, Akanda MI, Li D, Kozielski KL, Green JJ. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:3592. doi: 10.1021/bm200807s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaumet M, Gurny R, Delie F. Int J Pharm. 2010;390:45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tzeng SY, Guerrero-Cázares H, Martinez EE, Sunshine JC, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Green JJ. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5402. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.